Abstract

Construction firms operate within a business environment characterized by uncertainty and a lack of predictability, increasing the complexity of strategic decision-making. Construction contractor firms’ strategic response to environmental turbulence is appropriately documented but evidence regarding Construction Professional Service Firms (CPSF’S) remains scarce. CPSF’s are characteristically different from contractor organizations due to the intangibility of services and high knowledge intensity. The purpose of the study is to ascertain the impact of environmental turbulence on strategic decision-making process characteristics in CPSF’s, specifically Irish Quantity Surveying (QS) practices. Using a mixed-methods research strategy, data collected over two dissimilar stages on the economic cycle is presented. A comparative analysis over time exposes the varied impact of environmental turbulence on strategy process characteristics, however, a notable shift in the strategic choice is evident. An emergent approach to strategizing coupled with a move from written strategic plans is evident, while competitor analysis remains superficial. A taxonomy of the strategic decision-making process is derived from the empirical data which uniquely highlights the role of path dependence for CPSFs. The paper provides theoretical advancement in the discipline of CPSF strategy and also identifies a crucial component for consideration in driving transformational change required across the sector.

Introduction

Strategic management is a multifaceted discipline, widely researched over several decades though predominantly within the manufacturing rather than the construction sector. The limited evidence available within construction focuses largely on contractors, with the scant empirical exploration of Professional Service Firms (PSF's). PSF's are highly knowledge-intensive, involve a large degree of client interaction and customization, in addition to limited opportunities for repetitive learning (Maister Citation2003). Empirical inquiry into the strategic management of PSF's is a complex task, however, the critical role of Construction Professional Service Firms (CPSF’s) in the delivery of built environment assets accentuates the necessity to fill the chasm in existing intelligence in this regard. The complexity and multi-faceted nature of strategic decision-making in PSF’s are further complicated when examining the process within a turbulent business environment.

Several terms have been used to describe the changing and unpredictable setting within which companies may operate, including “high-velocity environments” (Eisenhardt Citation1989), markets that “will not stand still”, “hostile environment” (Covin and Slevin Citation1989), “fast-moving markets” (Volberda Citation1997) and most commonly “turbulent environment” (Prahalad and Hamel Citation1990, Grant Citation2003, Whittington et al. Citation2017). Regardless of the terminology used, the environment to which they refer is characterized by change, uncertainty, unpredictability, volatility, and complexity.

Discourse on the impact of environmental turbulence on the strategy process has grown over time across several industry sectors impelled by the seminal work of Eisenhardt (Citation1989) in the microcomputer sector, manufacturing (Covin and Slevin Citation1989), oil majors (Grant Citation2003), and Information and Communication Technology (ICT) (Wirtz et al. Citation2007). In construction, the limited empirical contributions have centred on contractors (Russell et al. Citation2014, Tansey et al. Citation2014, Citation2018) with considerably less focus on CPSF’s.

The Irish economy has undergone a period of rapid transformation, from a decade of continuous growth to 2007, followed by a severe contraction to 2013, and a return to growth from 2014 to Quarter 1 (Q1) 2020. There remains a deficiency in empirical evidence of the impact of turbulent economic cycles on the strategic decision-making process within Construction Professional Service Firms (CPSF's) in Ireland.

Previous research identified for the first time, the type, scope, and extent of strategic planning in addition to the strategic choices made within Quantity Surveying (QS) practices in Ireland (Murphy Citation2013). Since the original investigation, the business environment in Ireland has undergone monumental change due to a confluence of economic, systemic, sectoral, systemic, and international events. This study extends the earlier study by examining strategic decision-making process characteristics at a different phase of the economic cycle such that a comparison can be undertaken to determine the impact of environmental turbulence on the strategic decision-making process and the resulting choices made. The objectives are therefore confirmed as follows:

to ascertain the impact of environmental turbulence on the strategic decision-making process of Irish QS practices;

to determine the resulting impact on generic strategic choices;

to establish the existence of strategic groups within the profession.

The paper is set out in four parts. The first section provides the theoretical background underpinning the research concluding with a presentation of the theoretical framework within which the parameters of the research are delineated.

The second section details the research strategy employed for the purpose of the research. A mixed-methods approach over two dissimilar stages of the business cycle is undertaken to facilitate comparison over a timeframe characterized by environmental turbulence. The scope of analysis within this paper principally concentrates on quantitative data with limited reference to qualitative data when warranted.

A comparative presentation and analysis of research findings over the two periods of time are then presented before a discussion of key findings.

The concluding section details the key contributions of the paper. While there are several stand-out findings from the research, the continuous change facing the construction industry necessitates an ongoing discourse as regards the strategic management of stakeholders operating within the sector.

Theoretical background

Strategy process in a turbulent environment

Strategy formulation process characteristics

Strategic planning has many potential benefits to organizations in shaping future direction and profitability; however, given the complexity and multifaceted nature of the discipline no single definition of strategic planning is universally agreed upon. Strategy research is commonly separated into two main components, namely, strategy development (formulation) and implementation (Piercy et al. Citation2012), both of which are multifaceted. The realization of a formulated strategy depends on successful implementation, however, the scope of analysis within this paper lies within the strategy formulation domain. Many factors shape strategic decisions which vary between organizations, therefore the process characteristics and dynamic relationships between process characteristics, resources, and strategic choices must be explored.

Strategy formulation involves the determination of company goals (ends), how the firm will compete and what resources (means) are required to achieve the goals (Porter Citation1980). These goals are a result of strategic decision-making curated via the strategy process. Characteristics of the strategic decision-making process will differ between firms, and can be considered along several dimensions, which include, but are not limited to the:

approach to strategic decision-making (Mintzberg and Lampel Citation1999, Grant Citation2003);

organizational type (Miles and Snow Citation1978);

planning formality (Price et al. Citation2003);

the comprehensiveness of integrated decision-making (Fredrickson and Mitchell Citation1984).

flow of decision-making (Segars and Grover Citation1999);

participation in the decision-making process (Papke-Shields et al. Citation2006).

The approach to the strategy may be planned and follow a formal process resulting in a written strategic plan, or it may emerge over time in response to changing environmental circumstances (Mintzberg and Lampel Citation1999). There is growing evidence to support the need for flexibility in the process whereby a “planned emergence” approach may be appropriate, particularly within a turbulent business environment (Grant Citation2003). In adopting this approach, firms should not rely solely on either planned (rational) or emergent (incremental) approaches, but rather elements of both such that an “adaptive flexibility” can be embraced to respond to uncertainty (Brews and Purohit Citation2007). Another approach to gaining competitive advantage rests with the exploitation of valuable internal resources of a firm, known as the Resource-Based View (RBV), following the seminal work of Barney (Citation1991). The RBV paradigm is particularly suited for application within CPSF's within any sector given the emphasis on human capital and knowledge as an asset in the pursuit of competitive advantage within service firms (Hitt et al. Citation2001, Newbert Citation2007).

The approach to strategy formulation is influenced by the type of organization. Miles and Snow (Citation1978) put forward an organizational framework representing variations in the strategy process based upon an organization's unique features, such that configurations of decision-making will evolve along with four broad types, namely:

Defenders: organizations that have narrow or mature product/service focus and concentrate not on new modes of operation, but rather on improving existing operations;

Prospectors: organizations that continually search for new market opportunities; innovative and drivers of change;

Analyzers: combine elements of defenders and prospectors in that they can drive change but also fiercely defend existing markets;

Reactors: react to rather than lead the market.

The organizational type will influence the approach to strategic planning, the risk attitude of the strategist, and the degree of formality in the process itself. For construction contractor firms, process formality is correlated to firm size (Price et al. Citation2003) and ownership structure (Dansoh Citation2005), in addition to an organizational type. Limited evidence exists within a construction context of organizational types about QS practices save for the earlier study (Murphy Citation2013) and as noted, the external environment facing these firms has changed significantly since the earlier study was undertaken.

The extent of environmental (internal and external) analysis integration in the decision-making process and the extent to which firms are exhaustive in information gathering is known as strategy comprehensiveness (Fredrickson and Mitchell Citation1984, Thomas and Ambrosini Citation2015). Several factors may impact the degree of comprehensiveness, including strategic type (with prospector and analyzer firms more likely to be comprehensive) and firm size [with Small to Medium Enterprises (SME's) less likely to be comprehensive] in this regard. It is reasonable to postulate that CPSF’s in Ireland (the overwhelming majority of which are SME’s) are unlikely to gather significant environmental information to inform decision-making.

Two further characteristics of the strategic decision-making process relate to the organizational flow of decision-making and the extent of participation in the process (Mack and Szulanski Citation2017). The flow of decision-making may be top-down from senior management after which tasks are delegated, or bottom-up, where employee input is sought in a more collaborative and participative approach. Within construction, evidence suggests that planning flows from the top level of the organization down to lower levels with limited participation (Dansoh Citation2005), a finding consistent with other sectors (Papke-Shields et al. Citation2006).

Central to the strategic decision-making process is the requirement for firms to make choices about their future desired state, with these choices related to the domain in which the organization will operate to achieve future goals (Porter Citation1980). The strategic choice depends on both inward-focused (internal competencies/resources) and external (market-focused) parameters, as it links conditions within the company to influence the position of the organization within the business environment. In this study, two tiers of strategic choices are considered, which are framed upon Porter's (Citation1980) generic strategies.

Corporate strategy is concerned with the overarching purpose and goals of the organization and includes choices about how to compete, how to identify value creation activities, and whether to enter, consolidate, or exit businesses for the maximization of long-term profitability. Corporate-level strategic choices may include stability, expansion, retrenchment, or a combination of the aforementioned strategies. A business strategy, on the other hand, relates to how an organization positions itself in the marketplace to achieve its corporate strategy and gain a competitive advantage. Porter (Citation1980) identified several generic business strategies, namely cost leadership, differentiation, focus, and stuck in the middle. Generic strategies have been analyzed in a variety of industry contexts, including construction. Jennings and Betts (Citation1996) provide a detailed application of Porter’s (Citation1980) generic strategies to the QS profession in the UK, while Tansey et al. (Citation2014) examined business-level response strategies to the Irish economic recession within construction contractor firms. What remains unknown is the extent to which the strategic choices change within volatile environmental contexts, nor the impact of the environment on the characteristics of the decision-making process within which the strategic choices are determined.

Strategic planning process characteristics will differ and may result in strategic groups that reflect varying degrees of “rational adaptive” planning (Papke-Shields et al. Citation2006). The rational characteristics included flow, formality, comprehensiveness, focus, and horizon, while the adaptive included participation and intensity. They found that the strategic management process varied systematically with the degree of “rational” and “adaptive” planning characteristics concluding that firms have different strategic decision-making profiles. Using similar process features, the earlier study of Irish QS practices (Murphy Citation2013) ascertained these characteristics, and the existence of clusters of QS practices, akin to strategic groups, were identified based on not only process characteristics, but also the resulting strategic choices made.

A combination of environmental, organizational, and decision-specific factors influence strategic decision-making process characteristics (Rajagopalan et al. Citation1993). Environmental factors are critically important in shaping strategy, as changing business environment may divert a company from its path towards an intended future goal to an alternative realized end state. The more volatile the environment, the more complex the decision-making process becomes, and the impact of environmental turbulence necessitates consideration.

Environmental turbulence

The construction industry is, by nature, a turbulent business environment characterized by economic dependence, intense competition, the possibility of a limited resource base, and a lack of predictability of work. In Ireland, economic cyclicality has resulted in underinvestment in construction, low productivity, skills shortages, and a lag in the adaptation of digitization when compared to manufacturing counterparts (DPER Citation2020). These challenges are apparent during periods of stability and are exacerbated during periods of uncertainty or decline. While many firms plan for growth, they seldom plan for decline (Benes and Diepeveen Citation1985), which has severe implications for a cyclical sector, such as construction. There is currently no empirical study within the Irish context, focussing on the impact of the turbulent environment on the strategic planning process and eventual choices made by CPSF’s.

It has been widely argued that the need for strategic planning increases with the degree of environmental uncertainty (Eisenhardt Citation1989, Brews and Purohit Citation2007), and changes in the process may include reduced time horizons, less formality, emphasis on performance planning, and decentralized decision-making (Grant Citation2003). This concurs with earlier evidence from Covin and Slevin, (Citation1989), wherein it was determined that small firms with an organic structure perform best in hostile environments. A possible explanation is offered by Gibbons and O'Connor (Citation2005), who argue that entrepreneurial firms undergo more frequent analysis of where their competitive advantage exists, thus requiring more intensive environmental analysis. It has also been argued that within “high velocity” environments, fast decision-makers use more information and identified more alternatives than slower decision-makers (Fredrickson and Mitchell Citation1984, Eisenhardt Citation1989, Brews and Hunt Citation1999). The construction sector in Ireland has yet to be analyzed extensively in this regard.

While engaging in strategic planning may be more challenging under conditions of market instability, ongoing planning is required as “failure of a firm to approximate its structure and processes to its environment will lead it to become uncompetitive” (Lansley Citation1987, p. 142). In an extension of this, Brews and Hunt (Citation1999) express caution, in that:

“Firms emerging from stable environments should be especially cautious. Since one possible outcome of operating in a stable environment is an underdeveloped planning capability, the learning curve faced by such firms when more sophisticated planning becomes necessary may be steep” (Brews and Hunt Citation1999, p. 906).

Evidence suggests that following the economic recession in Ireland (2008–2013), the majority of QS practices were beginning to adopt a more systematic approach to their strategic planning process (Murphy Citation2013), which should bode well for the more recent economic turbulence being witnessed in the industry. However, in the face of recent events, such as BREXIT, it is important to garner up-to-date insights on how these firms approach strategic planning and their overall decision-making process.

A firm must not only align strategy but must also possess the capabilities to fit strategy to the environment, as portrayed within the dynamic capabilities paradigm, whereby competitive advantage lies in how the firm shapes and aligns its capabilities to the environment within which it operates (Teece et al. Citation1997). To do so effectively, ongoing environmental monitoring is required to inform the strategy process, in addition to organizational flexibility and agility to position the organization. A strong case can therefore be made for a systematic yet flexible strategic plan (Brews and Hunt Citation1999), which typifies the planned-emergence approach (Grant Citation2003). Organizational agility and flexibility are vital to maintaining competitive advantage within uncertain environments, not only in the decision-making process but in terms of resources, such as technology, people, structures, systems, and processes (Ahmed et al. Citation1996). The heterogeneity of such capabilities may be an explanation as to why firms functioning under similar conditions may perform differently.

Within the construction sector in Ireland, domestic and global market uncertainty, emerging technologies, skills shortages, complex (often international) supply chains, sophisticated clients, and the threat of new entrants into the sector reinforce the need for flexibility to act and react to environmental change. Ng et al. (Citation2009) sought to identify measures that government and industry adopt in reaction to changes in construction demand to revive and maintain the long-term development of the industry. They noted that the causes of structural change included economic collapse, an overheated property market, reduction in public investment, and a lack of confidence in the investment. Most notable from their findings were that the causes were common in several countries, including Hong Kong, Singapore, Japan, Australia, UK, and South Korea. A subsequent section of this paper will demonstrate similar forces of change within Ireland.

A commonality in the causality of environmental turbulence is evident within the construction sector; however, response strategies are not uniform. Firms have to weigh the financial risk of investing during periods of uncertainty, against the competitive risk of not investing, which will impact competitiveness one way or the other (Latham Citation2009). This is particularly the case of small firms that may not have economies of scale or scope to mitigate against risks, however, may have greater organizational agility to respond to a crisis (Vargo and Seville Citation2011). Benson et al. (Citation2009) provide a useful comparison of response strategies in the construction sector globally including new markets, strict financial management, long-term relationships with clients, lower tender prices, emphasis on marketing and focus on core business. Tansey et al. (Citation2014) discovered that differentiation was the predominant strategy chosen by Irish construction contractors in response to the economic crises in 2007/8.

Strategy process in construction professional service firms (CPSFs)

The extensive body of strategy research focuses predominantly on manufacturing rather than construction (Hillebrandt and Cannon Citation1994) and inquiries within the construction sector are weighted in favour of large contracting organizations (Betts and Ofori Citation1992, Green et al. Citation2008) or project management (Phua Citation2006). Construction is a project-based sector, however, a shift from tactical (project) to strategic planning in construction is evident despite “several perceptions of what strategy is and of its implications for the enterprise”. (Betts and Ofori Citation1992). Evidence suggests that the driver of strategic decisions comes from fear of being left behind the competition, rather than any attempt to be innovative (Lansley Citation1987). Innovation and modernization are required to transform the construction sector to become more productive, sustainable and attract talent (Farmer Citation2016).

PSF clients across sectors including accounting, medical, legal and construction engage professionals for their knowledge and expertise, and it has been argued that clients engage the individual professional rather than a firm and the relationship with the client means the professional and client must complement each other (Gummesson Citation1979). The need for customization of service requires face-to-face interaction with the client and therefore regardless of the sector in question:

“…the core of the resource base of the professional service firm thus resides in the professionals employed and their ability to solve whatever problems the clients may want them to solve” (Løwendahl Citation2005, p. 45).

Clients require knowledge/expertise, experience, and efficiency in the service provided and all three are human factors, which extends to client relationships built over time improving firm reputation, thus likelihood of repeat business (Low and Robins Citation2014). It is important that such capabilities are developed, supported, and managed as the knowledge may diminish if it is not used (Prahalad and Hamel Citation1990, Lu and Sexton Citation2007).

The emphasis on internal resources of the PSF is aligned with the RBV of strategic management (Barney Citation1991, Teece et al. Citation1997), which posits that those resources are key to competitive advantage only if they are Valuable, Rare, Inimitable, and Organized to capture Value (VRIO). Knowledge (expertise) is thus a critical success factor for any PSF's in terms of explicit knowledge but also the tacit knowledge acquired through experience (Nielsen 2005 ), which may be a differentiating factor embedded into a company culture that separates otherwise similar PSF's. Client relationship management is critically important for a PSF, but exclusive concentration on service level targets may be to the detriment of profit targets due in part to the lack of the required skills, education, and training in business management (Price et al. Citation2003).

The education and training of a QS in Ireland prepare candidates for a professional career with competencies aligned to the Royal Institution of Chartered Surveyors (RICS) and its Irish partner, the Society of Chartered Surveyors Ireland (SCSI). In fact, it is a legal requirement to register the title of QS in Ireland upon completion of a minimum level of third-level educational attainment, which sets the profession apart from its contracting counterparts. The competencies do not include strategic management, however, which given the number of QS's that manage a CPSF, is a cause for concern. QS's have called for strategic management education and training to be provided to address the deficit (Murphy Citation2018).

Strategic decision-making process characteristics of QS practices were reported in the earlier paper wherein various planning profiles were determined along with several process characteristics and strategic choices (Murphy Citation2013). In Ireland, CPSF's are primarily SMEs, and it has been noted for some time that examining strategic planning in small firms is particularly important given the number of firms in question, their contribution to GDP, and their domination in some sectors, including construction (Robinson and Pearce Citation1984). Evidence from the research confirmed a growing realization amongst respondents of the need for strategic planning in light of environmental turbulence.

It is important to be reminded that strategic planning systems are learning systems that develop over time and are usually based on previous experience and the history of the company. Path dependency is, therefore, a feature that must be considered (Teece Citation1997) in particular within CPSF's, given the reliance on repeat business. Until now, the prevalence of path dependency remains undetermined in Irish CPSF’s.

Theoretical framework

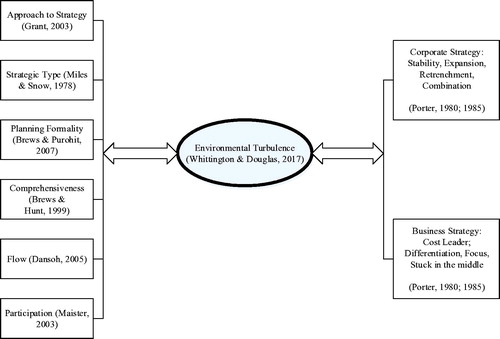

Strategic management is a multifaceted discipline (Price et al. Citation2003) and the complexities of the construction sector create challenges for empirical investigation into strategic management within the sector. presents a theoretical framework developed for the purpose of defining the scope of investigation within this multifaceted discipline and indicates seminal authors for each facet under scrutiny.

The left side of the framework indicates the strategic process characteristics under scrutiny. The right signposts strategic choices at both corporate and business levels, relying extensively on Porter's (Citation1980) generic strategies. The inclusion of both corporate and business level strategies ensures that both internal and external environmental factors are considered for the purposes of the research. Central to both is the turbulent environment within which QS practices operate, potentially impacting characteristics of the decision-making process and choices made. It is important to state that the argument in this paper is based on “a-posteriori” knowledge propositions (Holt and Goulding Citation2017), building on over a century-long research base within the established field of strategy. The framework, therefore, defines the theoretically established parameters of this strategy investigation and thus outlines the scope of the research at hand; however, it is useful to outline the context within which the study was conducted.

Research in context: an overview of the Irish construction industry

The Irish economy and construction sector has undergone a period of monumental change over the last decade, from a phase of continuous expansion (2000–2007), economic recession (2008–2013) to recovery and growth (2014–2020). From early 2000 to 2007, the Irish economy experienced a period of uninterrupted growth on average of 7.5% Gross Domestic Product (GDP) per annum (CSO Citation2020a), driven by a booming property sector. Demand for non-residential construction was propelled by foreign direct investment (FDI) boosted by low corporate tax rates, as well as an injection of EU structural funding for large-scale infrastructure projects. By 2006, the construction industry accounted for almost 25% of GNP and 18% of employment in Ireland.

The global recession from 2008 exposed systemic banking failings, and overreliance on property and construction in Ireland became apparent. The debt-fuelled growth during the “Celtic Tiger” years had been supported by substantial borrowing from abroad, which caused a fear of contagion across the EU ultimately leading to a €64bn EU/IMF bailout in 2010. Several years' austerity ensued to reduce the government budget deficit and national debt, which had snowballed in 2013 to over 120% of GDP (CSO Citation2020b).

By 2014, evident signs of recovery were apparent, and the Irish economy grew every quarter, with Ireland being the fastest growing economy in Europe by year-end 2019 (CSO 2020b). With economic growth came a recovery in the Irish construction sector in terms of output and the number of people employed. Towards the end of the first quarter (Q1) 2020 however, another economic shock hit globally with the Covid-19 pandemic. Economic activity, including construction, witnessed a serious decline for a large proportion of the second quarter (Q2). At the time of writing the full impact of Covid-19 on the construction sector remains unknown; however, the magnitude of the shock will test the resilience of, and challenge financial conditions throughout the Irish economy (Central Bank of Ireland Citation2020). The Irish construction sector will also be impacted by Brexit; however, the full impact is indeterminable at the time of writing due to the cessation of construction activity due to Covid-19 restrictions.

Economic cyclicality is one of several dynamic forces causing unpredictability and volatility within the construction sector. Discontinuous demand conditions, heterogeneous output, and multiple stakeholders along a complex supply chain are features of the sector, which in Ireland are coupled with low productivity, sluggish take-up of Information Technology (IT), and a skills shortage (DPER Citation2020), specifically for QS's (Murphy Citation2018). Most strategy studies adopt a market-based view to studying the construction industry, however, there remains limited empirical evidence at an organizational level as to the strategy processes employed in decision-making within firms operating in Ireland’s notoriously volatile and cyclical construction business environment.

Research method

The multifarious nature of strategic decision-making within PSF's operating in turbulent environments warrants a dual approach to unpacking strategy process characteristics and choices. A mixed-methods approach was employed to ensure a systematic determination of the variables in question while gaining depth of insight (Mertens et al. Citation2016), and included widespread surveys and interviews completed by the end of 2019 (thereby not reflecting Covid-19 circumstances). Similarly, to the seminal work undertaken by Grant (Citation2003) within the turbulent environment of the oil industry, this study did not involve hypothesis testing. The purpose of the study is not to explore causality, but to determine possible alteration in the strategy process of CPSF’s across two points of time during a period of profound turbulence.

Several arguments have been presented regarding the challenges with the use of mixed-methods research (MMR), most notably within the construction management community by Holt and Goulding (Citation2014). They argue that MMR research can either be explicit (i.e. have a design that explicitly states the intention to achieve a QUAN/QUAL paradigmatic mix), or ambiguous (i.e. have a design that does not make such explicit, but which does so in its application). The ambiguous mixed-methods research (AMMR) method is adopted in this study as it allows for “mixing” of both QUANT/QUAL methods sequentially or in parallel phases during data collection, analysis, and interpretation (Tashakkori and Teddlie Citation2003). The authors argue that AMMR design, although “mixed”, tends to adopt either a QUAN or QUAL emphasis either in the type of questions asked or in the type of inferences drawn from the study. The AMMR design adopted in this study appears to conceptualize a single method explicit design (QUANT) but embodies the requirement for mixed methods by using data from the QUAL phase to support finding where relevant.

Data were collected over two distinctly different time periods in Ireland, the first of which took place during the economic downturn (2009/2010) and the second during a period of sustained economic growth (2018/2019). The research was supported by the Society of Chartered Surveyors Ireland (SCSI) for both time periods, whereby a single key informant within every QS member practice was identified for the purposes of participation in the research. The most senior person within each practice (principal) was the target respondent as they are best placed to provide insight into the strategic planning process and choices made within the practice. In some instances, the principal was the Owner or Partner, while in other cases the Managing Director (depending on the ownership structure of the company). Target respondents were asked to “opt-in” to participate in the research before engagement with the researchers.

Research design

Phase 1 quantitative

The first phase reflects the positivist approach whereby a widespread survey of QS practice principals was undertaken. Based on the considerable body of existing literature, a survey questionnaire was developed to ascertain the extent of strategic planning, strategy process characteristics, and generic strategies pursued by Irish QS practices. The theoretical underpinning for the derivation of questions asked is presented in . The survey was structured in four parts, as follows:

General company information: number of employees, location, number of years in business, ownership structure; position held by the respondent within the company; sectors serviced; services offered;

Strategic planning process characteristics: respondents were asked to confirm the approach to strategic decision-making; comprehensiveness; strategic type; flow of decision-making; participation in the decision-making process (Miles and Snow Citation1978, Fredrickson and Mitchell Citation1984, Stonehouse and Pemberton Citation2002, Dansoh Citation2005, Papke-Shields et al. Citation2006, Segars and Grover Citation1999):

Strategic choice: respondents were asked to select the predominant corporate strategy and business level strategy based upon several options presented (Porter Citation1980);

Environmental analysis and impact of environmental turbulence: respondents were asked to confirm changes over the two time periods about options contained in 2 and 3 (Porter Citation1980, Hillebrandt and Cannon Citation1994, Grant Citation2003).

Questions about process characteristics (number 2) were presented on a five-point Likert response format, measuring respondent opinion via a scaled stem from “negative” (i.e. “strongly disagree”), to “positive” (i.e. “strongly agree”) (Johns Citation2010). While the appropriate number of response points on the scale is contested (some authors claim that the 7-point scale is superior to the adopted 5-point scale in this paper, e.g. Harzing et al. Citation2009), the justification for adopting this 5-point scale is tripartite. First, the scale was adopted for consistency as the earlier study adopted a 5-point scale and the comparative analysis was between time periods. Next, due to the length of the questionnaire, the 5-point scale was preferred to avoid respondent fatigue (Ben-Nun Citation2008). Lastly, an indication of preferences of respondents was solicited therefore, the 5-point scale is appropriate under such circumstances (Fellows and Liu Citation2013). Where necessary explanations for key terms were provided to avoid ambiguity for respondents. The remaining questions were single select close-ended multiple-choice questions. In several instances scope existed for respondents to provide supplementary comments to expound their response, which offered considerable auxiliary insight. The navigational guide was consistent throughout the survey in both periods of data collection for ease of navigation (Dillman Citation2000), and most of the data from the quantitative phase are presented in percentages (%) based on the number of respondents that selected this option.

The survey instrument was pilot tested during both time periods to ensure clarity in terminology and to estimate timing for completion. The survey was administered through an online survey instrument and the data collected was anonymous, so no individual is identifiable.

Phase 2 qualitative

The second phase reflects a phenomenological philosophy involving in-depth semi-structured interviews with the principal of several QS practices. An interview protocol template was developed, which broadly followed the four-section structure of the questionnaire to ensure that findings across both phases of data collection (over both periods of time) were comparable (Montoya Citation2016). The qualitative phase provided a greater depth of understanding of the issues at hand. While the interview protocol ensured consistency in addressing the same issues as the quantitate phased, it retained flexibility to permit further probing of respondents as required.

Methodological triangulation was used to guard against threats to validity, enabled by structuring both data collection instruments along with the same thematic areas across both phases. Data collection across both phases was based on current (rather than retrospective) insight, thus addressing concerns raised by Whittington et al. (Citation2017), about limitations in previous strategic planning research.

Data collection and analysis

Data collection and analysis techniques were consistent across the two time periods (2009/10 and 2018/19). A covering email provided an outline of the purpose and scope of the study together with assurances of anonymity of responses. To reflect different experiences within the time periods studied, data was collected from informants with senior roles (managers, directors, and senior QS’s) to capture variation in strategic decision-making processes across QS firms in Ireland.

Confirmation of how data was to be used, stored, and discarded upon completion was also provided, and the voluntary nature of participation was assured. Participants were also reminded that they could opt out at any stage. The quantitative data was downloaded from the online survey platform and collated into encrypted files for analysis purposes.

Semi-structured interviews were conducted during the second phase of research in both time periods, addressing the same themes as within the quantitative phase. With the permission of respondents, interviews were recorded, transcribed verbatim, and returned to participants to confirm accuracy before being uploaded into a Computer Assisted Qualitative Data Analysis Software (CAQDAS), NVivo, for analysis. A folder was established within NVivo for each participating company wherein additional company information was placed. A multi-layered coding design was developed, which mirrored the quantitative survey questions to facilitate cross-phase analysis, in addition, to cross time-period analysis. The criteria/themes for coding have already been pre-established from the quantitative survey, hence the qualitative data only served the purpose of providing deeper interpretation and discovering new insights, not designing new categories or themes.

Research population and response rate

The nature of the investigation warrants the participation of senior management, who were deemed best placed to have the knowledge and experience to provide insight into the strategic decision-making process of QS practices. The SCSI is not only the professional body for QS's, but also the registration body for QS's in Ireland, named within the Building Control Act (2007). With the support of the SCSI, target respondents were identified (for both periods of time) at the most senior level within each SCSI QS member practice, and permission to participate in the research was agreed directly with the Society in the first instance. In instances where the company was part of a larger global organization, the most senior person within the Irish base was contacted and asked to respond based upon market conditions in Ireland. Only one key informant was identified to participate on behalf of the practice to guard against double counting. This sampling strategy is consistent with the purposive, non-probability sampling technique from a defined population. A single informant from all QS PSFs registered with the SCSI was invited to participate in the research, however, contractor organizations in addition to QS members that may work in other sectors (e.g. retail and public bodies) were excluded. It is acknowledged that there may be other practices offering QS services that are not members of the SCSI; however, the SCSI is the only professional body for the surveying profession in Ireland, therefore, is considered representative of the profession.

For the quantitative phase in both time periods, an email invitation including a link to the survey was sent to the confirmed key informant, which outlined the purpose and scope of the research and always ensured confidentiality and anonymity. Following the initial invitation to participate, several follow-up requests were sent to those that had not responded, and the overall population size, the number of usable responses, and the response rate for each period are presented in .

Table 1. Quantitative phase population and response rate.

The data in shows that response rates obtained exceed 20%, which is deemed acceptable in construction management studies (Hua Citation2007, Zhao et al. 2013).

Qualitative phase participants were selected based on a stratified sample from the SCSI membership based on known company size to ensure data was collected across all company sizes. There are diverse ways of defining and measuring company size including turnover, market share, profitability, and the number of employees. However, even if using the number of employees is the yardstick by which company size is measured, what constitutes a large company for one sector may not apply to another. The Central Statistics Office (CSO) in Ireland classify construction company size by the number of persons engaged in three bands, namely 0–9, 10–49, 50–249, and 250 and over, however, this relates primarily to contractor firms, which are more likely to employ more people than PSFs. For this reason, the researchers, informed by the CSO and SCSI, categorized QS practice into three bands with large QS PSF's employing >50 employees.

Details of qualitative phase participants and are presented in .

Table 2. Qualitative phase respondents by size of practice.

Reliability and validity

The research at hand replicates the earlier study that had demonstrated methodological triangulation (Murphy Citation2013). It is not known whether the same individual respondents were involved over the two periods in question, however, both sets of respondents were SCSI member firms; therefore, it is not perceived as presenting any limitation to the validity of responses as the responses were drawn from the same database.

For the purpose of the analysis to follow, the quantitative dataset appears more prominent with qualitative data supporting the analysis only as required, which is aligned with the previously discussed AMMR technique (Holt and Goulding Citation2014). The quantitative data collection came first, followed by interviews to explore the issues in-depth, and this procedure was repeated across two different time periods (P1 and P2), with comparisons reported across both time periods. Period 1 (P1-2009/10) signified a period during which Ireland was deep in recession, while Period 2 (P2-2018/2019) was a period of return to steady growth within the Irish economy and construction sector. The same questions were posed to respondents in both quantitative and qualitative phases, with the qualitative data only reported to enrich the findings from the quantitative phase and for better depth of understanding and explanation of the issues under scrutiny.

Findings

The data presented in this section relates to the percentage number of respondents that selected an option from the answer options provided to them, while the qualitative data is used to provide further understanding into the findings. Since similar questions were asked in both QUANT & QUAL phases, the QUAL data used purely to provide additional insight to garner greater meaning QUANT findings.

General company information

Data obtained from the online survey provided invaluable insight into the demographics of QS practices in Ireland, which was compared across two time periods Period 1 (P1) (2009/10) and Period 2 (P2) (2018/2019). The time periods in question represent entirely different stages of the economic cycle, thus the underlying rationale for comparative purpose.

As previously noted, target participants were senior-level members of the SCSI thus it is unsurprising to confirm that 90% of survey respondents in each period holding the position of Managing Director/Managing Partner. The decision to target senior managers was based on their involvement in the strategic decision-making process, and best placed to determine the future direction of the practice. Those participants managing the Irish subsidiary of a larger global organization held the most senior position within the Irish operation and were asked to respond on local rather than global experience. 12% of respondents during P1 confirmed their practice was part of a larger international consultancy, whereas during P2 this was the case for 6% of respondents.

Survey data confirmed a similar breakdown of respondents across firm sizes in both periods of research, with the overwhelming majority employing fewer than ten people (see ). This is broadly in line with nationally available construction sector data for the sector as a whole. The domination of small practices with considerably fewer large practices has implications on the competitive environment within which these practices operate and are comparable to the findings of Jennings and Betts (Citation1996).

Table 3. Size of practices in quantitative phase.

While broadly the number of years in business is similar between the two periods, one divergence is that there are proportionately fewer newly established practices in P2. A possible explanation for the larger proportion of small firms in P1 may be that at that time the construction sector was in recession, and due to resultant company retrenchment and layoffs, gave rise to opportunities for QS's to establish their own practice. In both periods, there are a sizable proportion of respondent firms that have been in existence for over 20 years, thus have survived through several economic cycles (see ). This reinforces the appropriateness of the respondents in informing the research.

Table 4. Number of years in business of practices in quantitative phase.

The range of services provided amongst respondent firms is, as expected, primarily core QS services however 70% of respondents at each period of the study confirmed that the range of services had not changed between the two time periods in question. It is reasonable to conclude that environmental turbulence does not have a significant impact on the determination of services provided, which is a divergence from existing knowledge within Irish contracting firms (Tansey et al. Citation2018).

Demographic information obtained during the quantitative phase was explored during the qualitative phase wherein several participants confirmed they made a strategic decision to limit company size, regardless of growth in the sector as they sought to remain practising QS's rather than business managers. This is particularly the case for smaller practices with fewer than ten employees, which constitutes the largest portion of QS practices in Ireland. This is an essential factor for the determination of corporate strategy, whereby the subjective experiences of senior management influence the decision-making process and strategic direction of the practice. Furthermore, over half of the practices studied (in both phases of data collection) were established more than ten years, thus have experienced economic cyclicality, which is a critical determining factor emanating from the interviews undertaken. The demographic data obtained from survey data and further insight from interviews provide an underpinning for the strategic decision-making process characteristics and strategic choices made by QS practices in Ireland.

Strategic planning process characteristics

Strategic decision-making is complex and multifaceted, and despite QS practices facing the same business environment and market conditions, the characteristics of the decision-making process in response to environmental conditions vary depending on the type, size, and approach to strategy formation.

Strategic approach and type

The approach to strategy formulation shapes how decisions are made, and similarly to other strategy process varies between firms. Survey respondents were requested to identify which approach was taken by the practice to strategic decision-making from three possible answer choices, reflecting a planned, emergent, and resource-based approach to strategy formation.

An apparent move towards an emergent approach is evident (), while proportionately fewer are deemed resource-based. It is interesting to note the shift away from resource-based to an emergent approach within a PSF, given the resource dependence of these firms. This may in part be explained by the current skills shortage within the QS profession (Murphy Citation2018) or that turbulence results in the process being less staff-driven, as indicated by Grant (Citation2003) within the oil industry. Another logical explanation is that the changing business environment required a flexible approach to decision-making thus emergent being the order of the day.

Table 5. Approach to strategy of survey respondents.

Table 6. Strategic type of survey respondents.

The portion of practices that adopt a planned approach to strategy has remained consistent over time periods, and the majority of these firms are large and have a more formal process. However, the type of QS practice also impacts the approach taken to strategic decision-making. Survey respondents were asked to identify which organizational type best represented their firm by selecting one of four answer options that reflected the Miles and Snow (Citation1978) typologies. The findings identify no significant difference between periods of data collection. P2 has a proportionately fewer analyzer and more defenders than the earlier period, whereas the number of reactor practices is broadly similar. Larger practices remained predominantly prospectors, which given their scale (and scope) economies is unsurprising. This finding is consistent with that of Desarbo et al. (Citation2005) within turbulent environments in several sectors internationally. Interview data confirmed during P2 that the severity of the economic collapse (which occurred during P1) and impact on businesses (in terms of staff lay-offs; financial difficulties etc.) was still at the forefront of their memory, and a more cautious approach to strategizing was being adapted by the practice.

In some instances, practices display characteristics of a “defender” because they want “…to engage in problem-solving rather than problem finding…prior to organizational action” (Miles and Snow Citation1978, p. 42), which is clearly the case with QS practices. However, they also display characteristics of the “analyzer” in that they are considering new opportunities but may not lead the way in driving innovation or change within the profession. The reactor type remains a dominant feature within QS practices which may be partly explained by the QS function within the construction process, with budgetary responsibility coupled with the customized nature of services provided by the QS requiring responsiveness to client's demands. While flexibility in reacting to a volatile environment may ensure survival, the corollary is that it may result in reactor firms being behind the curve in driving innovation or benefiting from the first-mover advantage in entering new markets, offering new services, or fully embracing technologies that could provide a competitive advantage. Leadership style may be a determining factor in shaping the strategic type, however, and while the examination of leadership style remains outside the scope of the current research, it presents a useful prospect for further exploration.

Comprehensiveness

Another characteristic of the strategic planning process lies with the extent to which firms are exhaustive in collecting, collating, and analyzing information to inform their decisions. Assessing the degree of comprehensiveness using Fredrickson and Mitchell's (Citation1984) definition (including rationality, exhaustive, inclusive, and integrated decision-making), provides inconclusive results for the QS practices under scrutiny. Survey respondents were asked to identify the depth and frequency of analysis of macroeconomic, industry, competitor, and internal factors, and interview respondents provided further insight pertaining to the type of analysis carried out. Findings from this research concur with Whittington et al. (Citation2017) who note that “Evidence in favour of reduced analysis in more turbulent environments is not yet conclusive”. (Whittington et al. Citation2017, p. 110).

Macroeconomic analysis during P2 is recorded as being undertaken according to survey data, which demonstrates a change from purely cursory macroeconomic analysis undertaken during P1. Economic fluctuations, government capital expenditure, and labour markets are the main elements of macroeconomic scrutinized by respondents. Between the two time periods, the extent of industry analysis has increased, with 81% of respondents in P2 confirming that analysis is now undertaken on an ongoing basis, whereas during P1 only 15% of survey respondents noted that they comprehensively gathered this information. Macroeconomic environmental scanning had clearly increased over the time period in question.

Interview respondents during P2 identified that the severity of the recession had resulted in a move towards greater construction industry analysis being undertaken to ascertain future potential growth sectors (e.g. residential, commercial, civil engineering, etc.). Government and industry reports are referred to with greater regularity to identify not only opportunities but potential downside risks to the future pipeline of projects. Thus, volatility increased comprehensives in this regard, whereby more information was gathered rather than less.

Filtering survey data based on organizational size uncovered disparity across respondents in the depth of macroeconomic and industry analysis. Across both phases, while overall the level of comprehensiveness has strengthened to a degree, for smaller firms, macroeconomic and industry analysis remains neither systematically nor regularly undertaken.

Regardless of company size, competitor analysis remains superficial across respondent practices a similar discovery to that of Price et al. (Citation2003). The confidential nature of competing for projects and the heterogeneous nature of construction projects offer possible explanations for the absence of competitor analysis. Where it does it exist, competitor analysis centres on feedback provided from public sector tenders to benchmark performance vis-à-vis competitors, and professional networks (including SCSI) coupled with the industry grapevine remain the primary source of competitor intelligence.

Internal analysis is undertaken routinely and integrated into the decision-making process by all respondent QS practices across both phases of research, which is confirmed through both quantitative and qualitative data gathering. Components of the internal operation of the practice, including human resources, technology, quality assurance, and finance are scrutinized on an ongoing basis, albeit it is not formally documented in many cases. The turbulent environment necessitated detailed scrutiny of every facet of the practice in a drive for efficiency and to compete for business successfully.

Human resources remain the critical success factor for Irish QS practices, however, the landscape changed considerably between P1 and P2. In the former practices were either in the process of or already had retrenched in size, whereas P2 is characterized by an acute staff shortage brought about by rapid economic growth and lag in the availability of qualified QS's. However, during both periods, there was widespread recognition that the potential to gain competitive advantage lay within the knowledge and experience of staff. Development and investment in people in up-skilling existing personnel to ensure a quality service provision and also training in new technologies, including BIM, is ever-present amongst respondent firms. Human resources, in addition to technology, are thus comprehensively analyzed, in particular the use of the latter to address shortages in the former. This finding aligns with those of Grant (Citation2003), who concluded that firms operating in a turbulent environment adopted new technologies, both in the drive for efficiency but also to keep up with industry norms.

Evidence about the comprehensiveness is thus varied depending on whether information gathering relates to macroeconomic, industry, industry, or competitors with the company being a determining factor in most instances.

Planning formality and time horizon

The flow of decision-making remains predominantly top-down amongst respondent practices. The reduction in company size has resulted in the SME's becoming “flatter”; consequently, communication systems are open and informal. The flatter organizational structure likely expedited response times in response to the fluctuating environment, a finding consistent with Robinson and Pearce (Citation1984); however, strategic-level decisions are ultimately crafted by senior management (P1 62% and P2 78% of survey respondents agreed that decision-making was top-down).

During P1 of the study, larger practices tended to have a more formal process than in the SMEs, and in many instances, resulted in a written strategic plan. This finding correlates with Price et al. (Citation2003) who noted the association between large company size and formality of the planning process. However, results from P2 reveal a shift from a formal written strategic plan, regardless of company size (survey results contained in ) which demonstrates the impact of a turbulent business environment on planning formality; a finding consistent with that of Grant (Citation2003).

Table 7. Written strategic plan of survey respondents.

The qualitative phase of research uncovered in some instances practices that previously had a written strategic plan, now perceives them to be of little value given the level of volatility. Thus, the incidence of QS practices having a written plan had diminished due to the uncertain environment.

The impact of a turbulent environment on planning cycles (or timeframe) remains inclusive, with Grant (Citation2003) and Dansoh (Citation2005) purporting that planning horizon shortens during environmental turbulence, and Whittington et al. (Citation2017) identifying that the evidence is “unsettled” as regards the turbulence/horizon debate. For Irish QS practice, regardless of whether strategies are formally written or otherwise, the planning cycle (or time horizon), remains unchanged between P1 and P2 at three years.

Strategic choice

A key objective of the research was to ascertain the impact of the turbulent environment on strategic choices made within QS practices in Ireland. In the past QS firms adopted several strategies (Murphy Citation2013), which is not unusual in a construction sector context (Betts and Ofori Citation1992) particularly in response to environmental turbulence (Benson et al. Citation2009). To ascertain the impact of environmental turbulence on strategic choices, survey respondents selected answer options that best described their corporate and business level strategies using Porter (Citation1980) classifications. Furthermore, they were asked to confirm if the chosen strategies had changed between time periods as a mechanism by which to ascertain the impact of environmental turbulence on strategic choice.

outlines the corporate strategies pursued over both time periods. The most significant change between periods is the number of QS practices pursuing an expansion strategy almost doubled, and those retrenching had more than halved. This is a clear indication of the positive correlation between economic growth and construction activity. Under one-fifth of QS practices pursue a combination strategy, and when it is pursued, it tends to be based on domestic and international market segmentation (expansion at home and stability abroad, for example).

Table 8. Corporate strategy of survey respondents.

Differentiation is by far the favoured business-level strategy, not only in terms of the range of services provided but also as they strive to provide a quality service to clients. Differentiating service delivery provides opportunities to win the repeat business on which QS practices depend, regardless of the practice size. In P1, 85% of survey respondents confirmed that repeat business was critical, a figure that increased to 95% in P2. Repeat business is central to the success of any PSF (Maister Citation2003) and the strategic importance of repeat business for sustained competitive advantage was recognized across the board, regardless of the practice size. This is similar to the findings of Lansley (Citation1987).

The dominance of differentiation strategy has previously been observed in QS practices (Jennings and Betts Citation1996) and the reliance on building a positive reputation is not unusual for construction firms (Green et al. Citation2008). However, in probing this issue during interviews, it became apparent that the basis of differentiation varies amongst QS practices. For SME's, differentiation is often based on providing personalized service with senior management present at client meetings, which was made possible because they remained practising QS's rather than purely business managers. They “go the extra mile” for clients and pride themselves for doing what they do very well with the flexibility to act and react swiftly to client requirements in the absence of bureaucratic systems to inhibit them. This is central to the discourse about the contrast between a practice and a business.

For large QS practices, differentiation often centres on the broad range of services provided and the ability, due to scale, to undertake massive construction projects. The ability to utilize expertise from international offices remains a crucial feature for larger practices which differentiates those practices from both the medium/large indigenous practices and SME's.

Findings diverge from that of Tansey et al. (Citation2014), who concluded that the majority of small (and medium-sized) contractor firms tend towards a cost leadership strategy. Quantitative data collected for this research in both P1 and P2 confirms that only 14% of professional QS practices in Ireland pursue cost leadership as the basis of their business-level competitive strategy. Interview respondents noted that while cost efficiencies were harnessed at an operational level during the economic recession, and that they did not compete on this basis as it is deemed a “race to the bottom”.

The findings from both phases of research, arising from both quantitative and qualitative data collection demonstrates that environmental turbulence has an assorted impact on the strategic decision-making process characteristics and choices made by QS practices.

Discussion

The evidence presented in this paper suggests that for Irish QS practices, several characteristics of the strategic decision-making process remain unchanged, despite the environmental turbulence encountered over the two time periods in question.

A consistency exists between the two periods under investigation in several facets of decision-making, with a substantial proportion of reactor firms, prominence of the top-down flow of decision-making, exhaustive internal analysis, and cursory competitor analysis undertaken amongst Irish QS practices.

On the other hand, other characteristics have transformed over the time period, such as the repositioning from analyzer to defender-type practices, in addition to a reduced emphasis on the resource-based towards an emergent approach to decision-making. The most notable variation in process characteristics is the shift away from written strategic plans with interview respondents maintaining that written strategic plans are pointless in a rapidly changing business environment. A word of caution must be sounded to ensure the lack of a written strategic plan does not dwindle the importance of planning itself. Lack of planning may result in diminished environmental scanning or careful resource allocation thus resulting in a strategic drift exacerbating the gap between intended and realized strategy.

Evidence from other volatile industry sectors has pointed towards a more pronounced impact of environmental volatility (Grant Citation2003), therefore, findings from this study represent a divergence from existing knowledge. Possible explanations may relate to the education, training, and often risk-averse nature of QS professionals, or perhaps the answer lies in the influence of the professional body. It may be the case that the very nature of construction, a project-based, cyclical industry with heterogeneous output and a complex supply chain made up of numerous stakeholders (from both public and private sectors) sets it apart from manufacturing counterparts – wherein the overwhelming majority of strategy research is undertaken.

Participants in the research are highly experienced professionals, involved in the management of practices that have been in operation in most instances for more than a decade, and survived economic cyclicality. The experience effect of participants may go some way to explain the commonalities across both time periods. Another explanation for commonalities within the decision-making process is path dependency. Prahalad and Bettis (Citation1986) argue that the established dominant logic within an organization can influence its decision-making processes. Strategists may apply decision-making patterns learned over time to current issues, irrespective of the current state of the external environment. This is an unexpected but pertinent discovery as until now, path dependence has not been investigated within the construction industry in Ireland, however, findings from this research clearly indicate the existence of path dependence within Irish QS practices.

It may be the case that previous decisions have guided the practice through economic recessions, therefore, the choices made may be deemed successful and justify replication. The education and ongoing Continuous Professional Development (CPD) of QSs may reinforce the dominant logic rather than foster innovation and change further compounding path dependency. Interview respondents confirmed that the long history and reputation of service excellence of their QS practice is proactively used to ensure ongoing repeat business, thereby supporting the proposition that the path already travelled influences future direction. It is critically important, however, that practice inefficiencies do not become engrained within internal processes, neither should procedural replication stifle innovation (Hemström et al. Citation2017) nor result in practices failing to establish new routines. Thus, while the history of the organization is central in fostering repeat business, it should not inhibit innovation within PSF's nor the strategic groups within which they are positioned.

Strategic groups are a set of firms that follow similar strategies across certain strategic variables (Claver et al. Citation2003, Mehra Citation2002). The existence of groups within QS practices in Ireland was first identified by Murphy (Citation2013), who highlighted the strategic variables grouping QS practices in Ireland. These strategic groups demonstrated similar planning profiles, with company size and ownership structure being the key determinants. The identification of strategic groups provides considerable insight into competitor behaviour, the basis of competition, and inter-practice rivalry amongst firms. Findings from this research confirm that the characteristics of the strategic groups identified within QS practices remained unchanged between the two time periods, thus patterns of strategic decision-making and inter-practice rivalry have remained constant despite environmental turbulence.

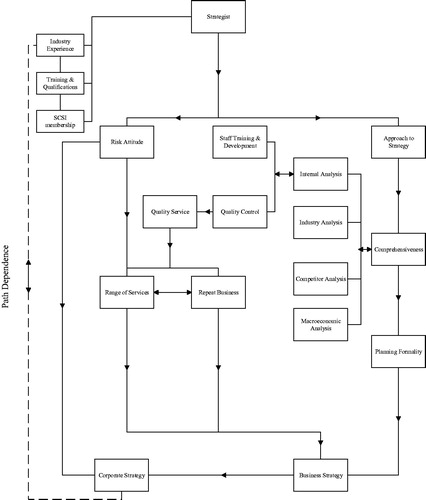

For a profession that does not routinely engage in competitor analysis, (in part due to the lack of available information about competitors), the strategic decision making taxonomy presented in provides an evidence-based (both theoretical and empirical) but the practical organization of key facets for consideration in shaping strategy for QS practices. The inclusion of path dependency in arising from a decade of research, is an important advancement arising from the research which warrants further empirical investigation.

The taxonomy incorporates the principal variables for consideration before strategic choices being made with the solid directional arrow representing the flow of the strategic decision-making process. Industry experience, training, and professional body membership influence the key strategist (decision maker) who is instrumental in influencing the approach to strategic decision-making. The approach is related to the risk attitude, but also influences the exhaustiveness to which information (internal, industry, competitor, and macroeconomic) is gathered and utilized. For CPSFs, internal resources are critically important and in QS practices, investment in staff training and development and quality control measures serve to increase quality in the service provided to clients to ensure repeat business upon which they depend. The quality service provision coupled with the risk attitude may then influence the range of services offered. Regardless of whether the strategic plan results in a formal written document or not, these components will ultimately determine the chosen corporate strategy and business strategy. The dotted line identifies path dependence, linking historical decision-making and external determinants (i.e. industry experience, training and qualification, and professional membership) back to current decisions. Path dependence emerged from research findings and the empirical testing of the dependence lay outside the scope of the research at hand.

The taxonomy presented does not result in uniform strategic choices made across the whole profession, and indeed this research concurs with the previous study (Murphy Citation2013) that identified distinct groups based on company size and ownership structure.

Characteristics diverge across QS practices depending upon the knowledge intensity, network effects, and existence of strategic groups within Irish QS practices may point towards a herding effect within the profession (wherein the group acts collectively) which may manifest due to social contagion (Seriki and Murphy Citation2018). Strategic groups tend to follow similar strategic patterns and more commonly compete within the group rather than outside it, and therefore it is reasonable to conclude that knowledge transfer may follow suit. While an extensive investigation of the prevalence of social contagion lies outside the scope of the research at hand, further investigation of trends in this regard may offer a mechanism by which current challenges, including slow technological adoption, productivity and modern methods of construction (DPER Citation2020) could be addressed.

Transformational change is difficult to implement due to the reproduction of legitimacy, efficiency, and power structures embedded in path dependencies (Nielsen Citation2010). In the context of calls for construction firms to “Modernize or Die” (Farmer Citation2016) the potential for inertia that path dependence may trigger must be averted. The research has provided unique empirical strategic insight into QS practices which now, through the taxonomy developed, may act as a guide to identifying and addressing these challenges and help shape strategic decision-making in practice. As noted previously, the QS core competencies do not include strategic management, thus the taxonomy has a practical benefit in outlining the multifaceted strategy process for non-(strategy) cognate practitioners.

Economic cycles are somewhat predictable through the market and economic trend analysis; however, the Covid-19 pandemic has radically impacted every facet of society and has resulted in the construction sector grounding to a halt. QS practices have not experienced an unforeseeable, exogenous shock of this magnitude in recent history; therefore, it remains to be seen whether path dependence will ensure survival or stifle innovative solutions needed for survival.

Perhaps this blow to the sector may be the catalyst for the change required to drive productivity improvements, technological innovation, and modern methods of construction.

Conclusions

The research has provided empirical evidence of the impact of environmental volatility on PSF's, and specifically QS practices in Ireland. The comparative analysis over two distinctly different periods of time gives unique insights, which heretofore was unknown in an Irish or international context. While the study was confined to Ireland, it has the potential to be replicated elsewhere and indeed within other PSF’s, construction or otherwise.

A key discovery from the research lies in the fact that the strategic decision-making process within QS practices remains largely unaffected by environmental turbulence. This echoes the findings of Green et al. (Citation2008), whereby path dependence is the critical factor shaping strategic choice. Evidence suggests that within Irish QS practices decisions are shaped as much by previous decisions as they are by rational choices.

A notable shift from formal strategy planning due to environmental turbulence is evident. QS firms are becoming more agile and responsive to the needs or demands of their clients via the emergent approach to decision-making and are thus less likely to have a more rigid written strategic plan. Ring and Perry (1985) posited that these firm’s experience better outcomes than firms that stick to an inflexible plan, and while measuring outcomes are beyond the scope of the current research, an opportunity now exists to extend the current study in that direction.

The paper has advanced contributed to knowledge on the strategic groups for QS firms in Ireland by incorporating the theoretical constructs from the vast body of strategy research, with evidence garnered from two phases of research. The taxonomy of strategic decision-making provides a macro-level composition of the decision-making process; however, the success of any strategy is dependent upon successful implementation. The scope now exists to advance the research further at a practice level, perhaps by applying a Strategy as Practice (SAP) lens (Jarzabkowski Citation2005), to uncover what QS practices actually do.

The identification of path dependence as a factor in the strategic decision-making process is significant and warrants further investigation in the context of transformational change required to improve construction sector productivity.

References

- Ahmed, P.K., Hardaker, G., and Carpenter, M., 1996. Integrated flexibility. Long range planning, 29 (4), 562–571.

- Barney, J., 1991. Firm resources and sustained competitive advantage. Journal of Management, 17 (1), 99–120.

- Ben-Nun, P., 2008. Respondent fatigue. Encyclopedia of survey research methods, 2, 742–743.

- Benes, J., and Diepeveen, W.J., 1985. Flexible planning in construction firms. Construction management and economics, 3 (1), 25–31.

- Betts, M., and Ofori, G., 1992. Strategic planning for competitive advantage in construction. Construction management and economics, 10, 511–532.

- Brews, P., and Purohit, D., 2007. Strategic planning in unstable environments. Long range planning, 40, 64–83.

- Brews, P., and Hunt, M.R., 1999. Learning to plan and planning to learn: resolving the planning school/learning school debate. Strategic management journal, 20 (10), 889–913.

- Central Bank of Ireland, 2020. Covid-19 – research and publications. Available from: https://www.centralbank.ie/consumer-hub/covid-19/research-and-publications [Accessed 20 July 2020].

- Central Statistics Office, 2020a. Gross domestic product and gross national product by state, quarter and statistic statbank. Available from: https://statbank.cso.ie/px/pxeirestat/Statire/SelectVarVal/Define.asp?maintable=NQQ44&PLanguage=0 [Accessed 20 July 2020].

- Central Statistics Office, 2020b. General government surplus/deficit ESA 2010 by state, statistical indicator and quarter. Available from: https://statbank.cso.ie/px/pxeirestat/Statire/SelectVarVal/saveselections.asp [Accessed 20 July 2020].

- Claver, E., Molina, J.F., and Tarí, J.J., 2003. Strategic groups and firm performance: the case of Spanish house-building firms. Construction management and economics, 21, 369–377.