Abstract

The organization of construction in the People’s Republic of China has over recent decades undergone radical restructuring. The announcement of Deng Xiaoping’s Open Door strategy in 1978 marked the beginning of the transition towards the espoused socialist market economy and the progressive introduction of market mechanisms. Existing research tends to focus on the derivation of “critical success factors” rather than the lived realities of those directly involved. In contrast, the current paper adopts a sensemaking perspective that privileges the transient roles and identities of those involved in the micro-processes of project organizing. The empirical focus lies on the sensemaking narratives of middle managers within three state-owned construction enterprises in the Chongqing city region. The findings illustrate how market mechanisms such as bidding and tendering play out in complex ways involving hybrid arrangements between new and pre-existing ways of working. The terminology of project management is seen to have played a performative role in establishing the “project” as the essential unit around which the socialist market is organized. Middle managers are further found to maintain multiple identities in response to the experienced paradoxes of the socialist market economy. The research provides new insights into the micro-processes of project organizing in China with broader implications for transitional economies elsewhere.

Introduction

The organization of construction in the People’s Republic of China has over recent decades been subject to a plethora of policy initiatives aimed at the introduction of market-based mechanisms. The announcement of the Open Door strategy by the Chinese government in 1978 is widely recognized to have been an important milestone in the ongoing journey towards the espoused “socialist market economy”. The policy had previously favoured the soviet-style centrally-planned economy initially inaugurated by Mao Zedong in 1949. However, the advent of Deng Xiaoping’s Open Door strategy initiated a radical re-structuring of the Chinese economy, with significant implications for the organization of construction. The policy switch resulted in unprecedented levels of economic growth driven in part by urbanization (Child Citation1996, Lin Citation2011). The construction sector was hence increasingly recognized as being of critical importance to China’s economic success. Yet there remains a stark absence of empirical research into the implications of the socialist market economy for those tasked with its implementation.

Numerous previous studies of the Chinese construction sector’s transition towards the socialist market economy focus on the identification of supposed critical success factors (e.g. Li et al. Citation2009, Zhao et al. Citation2013, Yan et al. Citation2019). Others focus on the determinants of competitive advantage (e.g. Lu et al. Citation2008, Niu et al. Citation2020). Yet there remains little emphasis on the way such determinants are mediated by practising managers in terms of their socially negotiated roles and identities. The latter are likely to be significant in shaping the emerging practices of the socialist market economy. Certainly, there is little reason to assume a straightforward causal relationship between policy and practice. Hence the research question which the current study seeks to address is as follows: to what extent are the micro-practices of project organizing in the Chinese construction sector shaped by the policy imperatives of the socialist market economy?

It should be emphasized that the above research question is essentially exploratory. In contrast to previous studies, the adopted methodology accentuates the agency of individual managers and the role of the socialist market economy in shaping their identities. Such research is seen to be crucial for the purposes of accessing the lived realities of the Chinese socialist market economy, with potentially important lessons for transitional economies elsewhere.

The adopted theoretical lens is provided by Weick’s (Citation1995) concept of sensemaking. This serves to emphasize the way practitioners continuously seek to rationalize their day-to-day experiences with reference to a “system of meaning” developed through experience and socialization (Søderberg Citation2003, Weick et al. Citation2005). Of particular interest are the processes through which practitioners continuously interpret the past for the purposes of making sense of the present. The adopted perspective takes ongoing processes of sensemaking to be synonymous with the micro practices of organizing (cf. Rouleau Citation2005, Weick et al. Citation2005), otherwise construed as the micro-practices of “every day practical coping” (cf. Chia and Holt Citation2006). Emphasis is also given to the associated concept of sensegiving which refers to the social practices through which people seek to influence the sensemaking of others (cf. Gioia and Chittipeddi Citation1991).

The adopted theoretical perspective is underpinned by an “ontology of becoming” which specifically privileges the terminology of fluidity and change in preference to that of fixity and permanence (Rescher Citation1996, Nayak and Chia Citation2011). In contrast to the commonly acclaimed “process” approach, we are not seeking to explore institutional change, or how “things” and “events” unfold over time (cf. Pettigrew Citation1992, Feldman Citation2000, Langley et al. Citation2013). The focus instead lies on the “practice worlds” which characterize the socialist market economy (cf. Sandberg and Tsoukas Citation2020). Such “practice worlds” can be seen to comprise a seamless flux of processes, relations, and interactions that exist in a perennial state of becoming. It is important to emphasize that we are not alluding to processes of fluidity and change between supposedly fixed endpoints, but to a reality that forever comprises continuous flux and transformation. Sensemaking is thereby seen as a means of achieving a shared sense of stability among those who might otherwise feel overwhelmed by incessant change. It is further contended that such ongoing processes of sensemaking are inseparably intertwined with “identity work” on the part of those involved.

It is important to acknowledge from the outset that there remains a degree of controversy about so-called “China studies” which are rooted in Western perspectives (Child Citation2009). We would certainly endorse the need for Western commentators to be cautious of the dangers of unreflective ethnocentrism. Yet the globalization of the Chinese economy means that what happens in China has consequences way beyond its national boundaries. There is also an ongoing debate about the extent to which Western-centric theory provides an appropriate means for understanding managerial practice in China, or whether priority should be given to indigenous approaches to theorizing (Barney and Zhang Citation2009, Alon et al. Citation2011). While such debates will inevitably continue, they risk being progressively marginalized by ongoing trends in the globalization of academia. For our part, we would wish simply to encourage a broader diversity of approaches than that which currently prevails.

We are further acutely aware of the long tradition of research which seeks to explain variances in managerial practice based on “cultural dimensions” (e.g. Hofstede Citation1980, Trompenaars and Hampden-Turner Citation1997). Much of this research remains contested in terms of the way culture is conceptualized on different levels of analysis, and the benefits/limitations of survey-based approaches to its measurement (Fellows and Liu Citation2013, Caprar et al. Citation2015). An additional difficulty in the case of China is that different regions often have their own distinct sub-cultures (Child and Warner Citation2003). We are also wary of imposing pre-determined “cultural dimensions” on those being researched, and of the associated dangers of cultural determinism. The adoption of a “becoming ontology” further negates any possibility of considering “culture” in terms of supposedly static dimensions. Hofstede (Citation2012) in his more recent work notably concedes that culture is best understood as an abstraction of reality, rather than something which exists in any tangible sense. Hence culture does not lend itself to direct observation and is only useful as a construct to the extent to which it aids understanding. The position adopted in the current paper is that culture is most meaningfully construed as a metaphor that is mobilized by practitioners for the ongoing purposes of sensemaking (cf. Smircich Citation1983, Morgan Citation2006).

The paper is structured as follows. Initially, there is a brief summary of the key historical events which have shaped the development of China’s “socialist market economy”. This historical overview is justified on the basis that practitioners often mobilize the past for the purposes of making sense of the present. Coverage begins with the Soviet-inspired era of Mao Zedong and extends through to the Open Door strategy initiated by Deng Xiaoping. Attention thereafter is directed at the subsequent policy initiatives in support of the socialist market economy. Emphasis is given to the extensive re-structuring of the Chinese construction sector in accordance with the imperatives of “enterprise”. The phased introduction of bidding and tendering is held to be especially important. The broad description of the constituent components of the socialist market economy is followed by the justification of sensemaking as the adopted theoretical perspective. The adopted methodology is presented as a means of identifying and explicating the sensemaking narratives of middle managers from within three state-owned contracting firms in the Chongqing city region of South West China. These narratives are seen as direct proxies for the micro-practices of project organizing. Finally, the broader implications of the research are discussed and conclusions are presented.

Historical background

The legacy of the Soviet system

Following the founding of the People’s Republic of China in 1949 one of the first actions of the government was to nationalize what remained of the industrial economy following the civil war. Heavy industries such as steel, coal, electricity, and machine manufacturing had previously suffered from decades of under-investment. Many of the large, capital-intensive firms became state-owned enterprises (SOEs). There was also a plethora of small, labour-intensive organizations which became subject to collective ownership. Commencing in 1953, China adopted a series of five-year plans with the aim of modernizing the economy (Lin Citation2011). State planning in China, however, was never quite as centralized as it had been in the Soviet Union. The governmental system in China is characterized by multiple levels each of which is responsible for the distribution of resources within its area of jurisdiction (Nee Citation1992). There are also significant differences across the various regions and municipalities within China, as recognized by Ye et al. (Citation2010) in their study of construction sector response strategies.

In the initial planning period (1953–1958), construction activities were primarily delivered by the engineering divisions of the People's Liberation Army (PLA). The so-called “engineering army” relied mainly on rural peasant conscripts under the direction of a cadre of politically trained officers. It is notable that many modern construction SOEs are direct descendants of the militarized divisions of the PLA. The China Railway Construction Company (CRCC), for example, was formed from the PLA’s specialized railway engineering division. However, there initially remained an expectation that the state would still provide workers with extensive welfare services. Schools, nurseries, and hospitals continued to be operated by the newly created SOEs. Such provision was an essential component of the “iron rice bowl” system through which the state sought to guarantee life-long job security.

The great leap forward

The economic targets set out in the second five-year plan (1958–1962) reflected the success of the previous planning period and were indicative of growing confidence amongst Chinese policy makers. By 1958 private ownership had been almost completely abolished to be replaced by state or collective forms of ownership. The ambitious aim was to transform a predominantly agrarian economy into a socialist society by means of rapid industrialization. In retrospect, the Great Leap Forward is now widely recognized as promoting too much change too quickly (Liu Citation2018). The Chinese economy consequently stalled, causing the closure of many factories. Numerous construction projects were also terminated before completion. In such circumstances, the well-intentioned socialist aspiration of full employment was no longer a viable option. Rural workers employed in urban areas were notably encouraged to return to their home communities in exchange for plots of land and basic tools for subsidence farming (Fung Citation2001).

The failure of the Great Leap Forward led directly to the prolonged political chaos of the Cultural Revolution (1966–1976). Throughout this difficult period, the construction sector continued to operate based on the direct allocation of work and resources through administrative means (Chen Citation1998). The Cultural Revolution remains a hugely sensitive subject within China, but it is widely accepted that these were lost years in terms of economic development. Modernization in any meaningful sense only started to occur following Deng Xiaoping’s announcement of the Open Door Policy in 1978.

The open door policy

The Third Plenary Session of the 11th Central Committee of the Communist Party of China in 1978 marked a radical departure from the preceding era of the Cultural Revolution. The new strategy placed a strong emphasis on economic development with a marked shift towards learning from the West. Of particular importance was the way the Open Door Policy privileged economic targets over the predominantly ideological goals of the Cultural Revolution (Child Citation1996).

Subsequent policy announcements by Deng Xiaoping notably emphasized the importance of a modernized construction sector to China’s ongoing economic development. Previously, construction was valued solely as a means of supporting the prioritized heavy industries. However, under the Open Door Policy, a modernized construction sector was seen as an essential component of economic development through urbanization. Of central importance was the stated goal of relinquishing direct control of construction enterprises by the state (Mayo and Liu Citation1995). The reform agenda which followed was characterized by the introduction of a plethora of market mechanisms aimed at the liberalization of the economy. China’s accession to the World Trade Organization in 2001 was an especially significant milestone in the liberalization of the Chinese economy (Lin Citation2011). In terms of economic development as measured by GDP, the reform programme initiated by Deng Xiaoping was undeniably successful. It was also of fundamental importance in shaping the development trajectory of the Chinese construction sector.

The evolving lexicon of the socialist market economy

Embracing enterprise

Of particular interest for current purposes are the policies aimed at the Chinese construction sector in support of the espoused “socialist market economy”. Reforms initially introduced by the Chinese State Council in 1984 progressively shifted the basis upon which construction is organized. Of additional importance was the introduction of a plethora of key roles which had not previously existed. Inspiration was explicitly derived from the market-based practices of the West. The newly designated state-owned enterprises (SOEs) were hence expected to develop the ability to make responsible business decisions (Mayo and Liu Citation1995). Competitiveness became the new mantra and over time became central to the research efforts of many China-based academics (e.g. Lu et al. Citation2008, Ye et al. Citation2010, Deng et al. Citation2013). Some SOEs were specifically allocated to specific cities or regions; others were assigned to sectoral ministries within the central government. Indicative of the rapidly changing landscape was the way in which soldiers from within the PLA’s engineering army were unilaterally re-designated as construction workers. Equally striking was the progressive replacement of the PLA’s officer corps by an emergent cadre of quasi-professionalized managers.

Throughout this period, the policy discourse consistently emphasized the importance of “energizing” SOEs to enable them to compete effectively in the emerging marketplace. The expectation was that they would exercise an increasing degree of autonomy in deciding how best to maximize their competitiveness. Nevertheless, they ultimately remained under the de facto supervision of the Ministry of Construction or, in some cases, regional governmental agencies. Some were undoubtedly subject to closer forms of supervision than others.

It is further important to recognize that concepts, such as “profit” and “loss” were by no means unknown before the advent of the Open Door policy. Previously however they tended to be determined through administrative means, rather than through market-based competition. The transition between the two systems was undoubtedly prolonged and uneven. It was also accompanied by a broader pattern of institutional reform which included the widespread decentralization of power to local government (Lin Citation2011). Throughout this period of change, SOEs continued to be held accountable for the enactment of policy despite the rhetoric of competitiveness (Nee Citation1992). The shift towards “enterprise” was therefore mediated by a range of factors that are rarely explicitly acknowledged in the construction-related literature.

Projectification

Wang and Huang (Citation2006) describe how “modern project management” was first introduced into the People’s Republic of China on the Lubuge hydroelectric project in Yun Nan Province. The project was partially funded by a loan from the World Bank, with the condition that the main contractor should be selected based on international competition (Chen et al. Citation2009). The successful bidder was Japan’s Taisei Corporation, which is credited with the introduction of project management into modern China (Yang Citation1987, World Bank Citation1993). The project was so successful that it subsequently became “mandatory” to adopt project management practices (Chen et al. Citation2009). However, the interpretation of project management which prevails in China differs from that which prevails in the West (Chen and Partington Citation2004). Indeed, there is little reason to assume that the interpretation of project management is consistent even within China.

One of the consequences of the Lubuge experiment was the subsequent promotion of project management as an essential component of modernization (cf. Ministry of Construction Citation1996). This served to normalize the “project” as the essential unit around which the emerging construction market was organized. The organizational processes of “projectification” have long since been recognized in the West (Söderlund Citation2004). Interest in recent years has notably extended beyond the increased primacy of projects towards a broader interest in the cultural and discursive processes by means of which the notion of projects is invoked (Packendorff and Lindgren Citation2014). The adoption of the project as the essential unit of competition is invariably taken for granted in the West. However, in China, the normalization of the “project” was a crucial component of the construction sector’s transition to the socialist market economy.

Reducing the burden

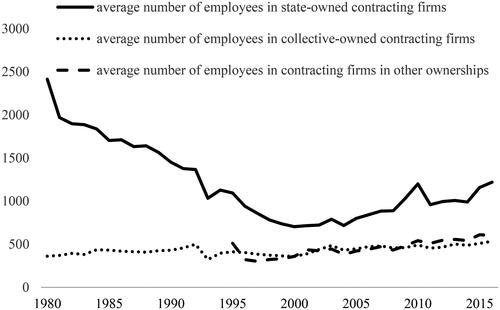

The concerted policy push towards projectification had important implications for the employment status of construction operatives. State-owned construction enterprises were subject to extensive downsizing as they sought to make themselves competitive following the introduction of the Open Door policy (Zou and Zhang Citation1999). In 1997 alone 9.40 million workers were reportedly laid off across the Chinese economy at large (Gao Citation1999). Hence the livelihoods of construction operatives became subject to the dynamics of market competition. The reduction in the number of employees within SOEs was especially striking (see ).

Figure 1. The average number of employees in contracting firms in different forms of ownership (Source: National Bureau of Statistics of China Citation2016).

Euphemisms, such as “reducing the burden” became commonplace as significant numbers of workers were suddenly deemed surplus to requirements. The shedding of personnel was frequently accompanied by the outsourcing of support services previously provided by in-house schools, nurseries, and even hospitals. The wholesale structural re-alignment of the sector also brought significant change in terms of the roles expected of those in management positions within the newly slimmed-down state-owned construction enterprises.

Project allocation through competitive bidding

Of further significance in the transition to the socialist market economy was the progressive introduction of competitive bidding as a means of project allocation. But the shift away from allocating projects through administrative means did not occur overnight. Chen (Citation1998) reports a gradual adoption of competitive bidding with apparently around 50% of contracts being let on this basis by 1994. Such transitions are rarely characterized by a simple binary choice in terms of whether a particular practice is adopted or not. A more likely scenario is an evolving plethora of transient hybrid practices enacted in accordance with localized priorities (cf. Bresnen and Marshall Citation2001).

One of the fundamental principles of competitive bidding in the West is that all parties should compete based on equivalent information (Hackett and Statham Citation2016). It is further routinely taken for granted that the resultant contracting parties should be subject to the same degree of legal protection. All such protocols are of course subject to abuse, and there are plenty of recurring instances of corruption in the West (cf. Jones Citation2012). However, relatively stable economies tend to have the advantage of a widely shared appreciation of the “rules of the game”. This is not so easily taken for granted in rapidly transitioning economies, such as China.

Of further relevance in China is the way the legitimacy of privately-owned firms continues to be contested on ideological grounds. This remains the case despite the exponential growth in the private sector from the late 1980s onwards. Alongside the introduction of market-based reforms, voices within the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) argued that an unregulated private sector would inevitably result in a “race to the bottom” (Ahlstrom and Bruton Citation2001). The situation was further complicated by the sustained growth of labour-intensive construction firms under collective ownership. Different parties could hence find themselves subject to very different interpretations of how competitive bidding should operate. It is also important to recognize that business opportunities in China are often purported to be highly dependent upon social networks of personal relationships, otherwise known as guanxi (Park and Luo Citation2001). However, caution is necessary for accepting guanxi as a supposed cultural phenomenon in isolation from the myriad ways in which it is practised (cf. Gold et al. Citation2004).

Making the case for sensemaking

Beyond descriptive fixity and classificatory stability

In making the case for sensemaking as the adopted theoretical lens, it is appropriate initially to describe how it differs from the approach adopted in previous studies of the Chinese construction sector. Many such studies notably focus on the identification of critical success factors (e.g. Li et al. Citation2009, Zhao et al. Citation2013, Yan et al. Citation2019). Others seek to identify supposed determinants of competitive advantage (e.g. Lu et al. Citation2008, Niu et al. Citation2020). The implicit assumption is that the “reality” of concern is relatively stable and can meaningfully be represented in the form of an abstract model (cf. Tsoukas Citation1994). The espoused critical success factors are typically derived from literature sources before being validated and prioritized based on “expert opinion”. There is a further tendency to position practising managers as the passive recipients of top-down policy initiatives, rather than ascribing them with any degree of agency.

Yan et al. (Citation2019) exemplify the prevailing methodological approach in their study of the adoption of program management techniques. They explicitly acknowledge the extensive change which has characterized the Chinese construction sector over the preceding decade and yet propose a “theoretical construct” that is essentially static. The proposed model comprises sixteen success criteria that they seek to validate through a questionnaire survey. Lu et al. (Citation2008) similarly focus on the critical success factors which supposedly determine the competitiveness of Chinese contractors. Chan et al. (Citation2010) likewise poll opinion via a questionnaire survey of the supposed critical success factors which determine the implementation of public-private partnerships (PPPs). Eighteen factors are derived from the literature before being ranked by selected “experts”. The results thereafter are subject to statistical analysis. In fairness, the authors in this latter case explicitly acknowledge the limitation caused by PPP being subject to ongoing evolution. The overriding emphasis nevertheless lies on classificatory stability, rather than continuous flux and transformation. The research literature cited also notably lacks any emphasis on the practices of those involved. Here in essence lies the justification for the adoption of sensemaking as the theoretical lens for the current study. Simply put, the adoption of a sensemaking perspective accentuates a reality that comprises continuous becoming. In contrast, the research studies described above at best only conceptualize processes of change as taking place between supposedly fixed endpoints.

Privileging fluidity and change

In contrast to the studies described above, the adoption of a sensemaking perspective privileges fluidity and change over notions of fixity and permanence (Weick et al. Citation2005). The adopted theoretical perspective is important in shaping the research questions which are asked, and the empirical data considered important (cf. Van Maanen et al. Citation2007, Schweber Citation2016). Rather than focus on supposed “critical success factors”, the current research seeks to access the sensemaking processes of middle managers. Sensemaking is construed to be synonymous with the collective processes through which meaning is continuously derived from ongoing streams of experience (Weick Citation1995, Colville et al. Citation2012). It is further held to be inseparable from the resultant initiated actions (Maitlis and Christianson Citation2014).

Sensemaking, therefore, includes the active authoring of the localized circumstances within which reflexive actors are embedded (Brown et al. Citation2015). Such actors are hence accorded a significant degree of agency. In essence, sensemaking can be seen to comprise iterative and overlapping processes of interpretation and action which unfold continuously over time. On this basis, it can be understood as a direct proxy for the micro practices of organizing (cf. Nicolini Citation2012). Sensemaking processes can further be conceptualized as being continuously enacted through the medium of narrative (Weick Citation1995). However, the principles of sensemaking are ultimately taken as essentially axiomatic. There is no expectation that they could ever be subject to empirical verification.

Sensemaking, sensegiving, and self-identity

Some authors emphasize the importance of sensegiving, which refers to the social practices through which people seek to influence the sensemaking of others (Gioia and Chittipeddi Citation1991, Rouleau Citation2005). The core argument is that managers routinely seek to normalize and legitimize preferred organizational realities (Gioia and Thomas Citation1996). Sector-level improvement narratives can further be seen to be directly implicated in the sensemaking processes of middle managers (cf. Abolafia Citation2010). Foster et al. (Citation2017) likewise see formalized policy narratives to be routinely invoked by practising managers for the purposes of building legitimacy. This is arguably especially important in China given the regulating role of government and the policy-setting mechanisms of the CCP. However, there is little reason to believe that the relationship between the micro-activities of sensemaking and broader institutionalized policy narratives is causal or deterministic (cf. Allard-Poesi Citation2005).

Sensemaking processes are also widely held to be important as the means through which practicing managers develop and maintain a positive sense of self-identity (Weick Citation1995). The collective processes of sensemaking are further seen to be important in the formation of a collective social identity (Brown et al. Citation2015). The adoption of a sensemaking perspective thereby implies a sensitivity to the roles that individuals construct for themselves through interaction with others (cf. Cornelissen Citation2012). The current research hence echoes a broader emerging interest in the self-identities that construction practitioners create for themselves (cf. Gluch Citation2009, Brown and Phua Citation2011, Sergeeva and Green Citation2019). Of particular interest are the identities that practising managers in China create for themselves when faced with the paradoxes and complexities of the evolving socialist market economy. When faced with cues from the external environment, practitioners initially depend upon frames of reference derived from previous experience, but these are continuously revised in response to new experiences (Weick Citation1995, Allard-Poesi Citation2005, Fellows and Liu Citation2017). Hence the past provides the frames of reference through which we seek to make sense of the present, with direct consequences for the future. Suddaby and Foster (Citation2017) similarly argue that the cognitive frames used to make sense of the present are based on retrospective and collective interpretations of the past. All such cognitive frames of reference can further be seen to be inseparable from the way individuals see themselves, i.e. their inherent sense of self-identity. But such interpretations are again subject to continuous revision based on collective processes of sensemaking and sensegiving. Such processes are however mutually constituted and irrevocably embedded within the medium of narrative.

Methodology

Overview of guiding principles

The described research was essentially exploratory in nature. It was characterized from the outset by an iterative dialogue between theoretical concepts and emergent data. It is worth re-emphasizing that the aim of the research was not to discover some sort of external objective reality but to access the micro-practices of project organizing as shaped by the socialist market economy. Hence the focus of interest lay on understanding the lived realities and socially constructed meanings of social actors (cf. Sandberg and Tsoukas Citation2020).

The key benefit of adopting a sensemaking perspective is that it accentuates aspects of reality that previous studies have so notably ignored. Yet qualitative research of this nature often struggles to address a fundamental paradox. It defines reality and meanings as socially constructed, and yet seeks to establish supposedly “objective” knowledge (Schwandt Citation1996). The adopted position is that knowledge about managerial practice is inseparably embedded in the sensemaking narratives of those directly involved. Hence sensemaking scholars tend to rely on methods that privilege the situated nature of knowledge (Weick Citation1995). Yet the research process itself also comprises an act of sensemaking. It follows that researchers cannot construe themselves as independent objective observers of the sensemaking practices of others. The very act of asking questions, the very act of being present, inevitably disrupts the life-world of the respondents. The adopted theoretical perspective, therefore, challenges the commonly supposed dichotomy between “neutral” data and its subsequent interpretation. Positivist notions of validity based on replication give way to notions of trustworthiness (Pratt et al. Citation2019).

Sensemaking may well be increasingly accepted within the construction management research community (Fellows and Liu Citation2017). However, there is as yet little recognition of the implications of this acceptance for research methods. There is a tendency more broadly for sensemaking research to rely on narrative methods, not least because of the contention that “most organizational realities are based on narration” (Weick Citation1995, p. 127). Some researchers who align themselves with sensemaking further emphasize the importance of a longitudinal design whereby data is collected over an extended period (Easterby-Smith et al. Citation2014). Linderoth (Citation2017) notably follows such an approach in seeking to inform BIM implementation through comparison with sensemaking processes in the context of telemedicine. The underlying logic of such approaches hints at a quasi-realist interpretation whereby time is seen to play out in accordance with a linear scale. In contrast, the current research adopts a different perspective whereby the past and the future are seen as socially constructed categories that are continuously (re)assigned for the purposes of sensemaking (cf. Bakken et al. Citation2013, Sandberg and Tsoukas Citation2020).

Narrative interviews across three case studies

The primary research method comprised the use of narrative interviews with selected middle-managers from three targeted state-owned contracting firms. All three case study firms were located within the Chongqing city region in South West China. Narrative interviews are usefully conceptualized as micro-sites for the production of sensemaking narratives (cf. Czarniawska Citation2010, Ivanova-Gongne and Törnroos Citation2017). Rather than seeking answers to predefined questions, the aim is to provide respondents with the opportunity to share stories relating to their lived experiences (cf. Gioia and Thomas Citation1996). Participants may on occasion share sensemaking narratives that have been previously rehearsed and tested with other audiences. Alternatively, they may engage spontaneously in “second-order” sensemaking through the medium of narrative. Both are construed as bona fide sources of data. However, the two modes are often inseparably intertwined as participants seek to mobilize existing resources into new discursive configurations. It is further important to emphasize that the elicited stories are not viewed as being representative of a fixed external reality, but as fluid accounts of key events considered to be important. It follows that the research findings are forever essentially temporal (Sveningsson and Alvesson Citation2003).

Access to the selected case study firms was secured through the lead author’s contacts within local government. Initial agreement was gained for the purposes of conducting a series of pilot interviews. Interviews thereafter were arranged through a personal referral, otherwise construed as “snowballing”. Although it is convenient to refer to the interviewees being drawn from three case study firms, there is no claim to have adhered to the “case study method” as commonly recognized (cf. Flyvbjerg Citation2006, Eisenhardt Citation2021). Many of the supposed “rules” of case study research become much less relevant if the cases in question are conceived as sensemaking arenas. This is especially true of the more traditional interpretations of case study research which lean towards positivism (i.e. Yin Citation2017).

The three targeted firms are hereafter referred to as East City Construction Steel Company (ECCSC), South City Construction Housing Company (SCCHC), and North City Construction Engineering Company (NCCEC). All three firms are based within the Chongqing city region in South West China. ECCSC was initially established in 1965 to serve the needs of two local steel factories. It has since grown to be one of the largest contracting firms in Chongqing, with over 30 subsidiaries and reported revenue in 2016 of around 16 billion yuan. In contrast, SCCHC originated as a local government construction team that was moved into private ownership during the reforms of the 1990s. It returned to the state sector in 2015 when it was sold to a local state-owned contracting firm. With ∼150 employees, SCCHC is typical of most Chinese small-to-medium-sized contracting firms. Finally, NCCEC has long-established specialist interests in infrastructure, including roads, bridges, and railways. It was previously a subsidiary of a much larger state-owned company before being listed as an independent SOE in 2016 with its headquarters in Chongqing. One year later it comprised 2,000 employees with an order book of over 20 billion yuan.

Data collection

The interviews were conducted in Chinese by the first-named author on a one-to-one basis. All interviewees were guaranteed full anonymity. Twenty-one interviews were sourced from ECCSC, 13 from SCCHC, and eight from NCCEC. Important access was also gained to the assigned party secretaries with responsibility for specific subsidiaries. Summary details of the 42 interviewees are listed in .

Table 1. Summary details of interviewees.

Each interview comprised a series of narrative generating questions aimed at encouraging respondents to share personalized stories of how their managerial practices have evolved in response to the challenges of the socialist market economy. Participants were encouraged at all times to use their own preferred terminologies. The aim throughout was to build a safe environment for communication with a view to eliciting narrative accounts in response to broad themes of enquiry. At no stage was there any attempt to pressurize the participants into answering pre-determined questions. The guiding dictum throughout was “listen more, talk less” (Seidman Citation2006, p. 78).

The respondents were initially asked to describe their experience and career trajectories. Follow-up prompts—if deemed necessary—focussed on their current roles within their respective organizations, and how these had evolved over time. Thereafter participants were encouraged to tell the story of how their firms had evolved in response to the policies of the socialist market economy. More specifically, they were invited to talk about how their firms had become more competitive and the implications for their own role. Particular attention was given to exploring how their firms had secured work throughout the period described. Supplementary lines of enquiry focussed on the way companies had restructured themselves over time, including any trends in the outsourcing of labour. Prompts often comprised an invitation to “say a bit more” about a particular issue that was deemed to be of interest. In all cases, the emphasis was on exploring the implications of such changes for the working lives of the interviewees. Finally, the respondents were asked to describe any other changes they felt had significantly impacted their working practices. Care was taken throughout to avoid imposing any ideas on the interviewees, or indeed any specific terminologies. All the interviews were recorded and transcribed with the explicit consent of the interviewees. Ethics approval was secured in accordance with University of Reading procedures.

In addition to collecting primary data from the interactive interviews, reference was also made to secondary data in the form of company histories and annual reports. The researchers were further careful to familiarize themselves with the broader policy landscape. This combination of methods enabled the researchers to judge the extent to which the interviewees offered plausible interpretations of the described key events.

Data analysis

The collected data comprised 42 rich and largely unstructured interviewee transcripts. Data analysis commenced with multiple readings of the interview transcripts followed by thematic analysis. It was apparent from the outset that the sensemaking narratives of the interviewees drew extensively from the lexicon of the socialist market economy. The data was initially coded in accordance with the broad themes of interest as derived from the preceding literature review. However, the analysis in essence comprised an exercise in sensemaking on the part of the authors. The adopted codes were hence used as temporal facilitative devices rather than as quasi-positivist analytical constructs (cf. Denzin and Lincoln Citation1994). The process was guided throughout by the previously described methodological orientation towards sensemaking.

Following the initial engagement with the data, the analysis thereafter focussed on issues highlighted by the interviewees but not covered in the literature. Particular attention was given to those which were considered to offer fresh insights. The authors undoubtedly made strategic choices in terms of which aspects of the data were prioritized. It was on this basis that several subsidiary and cross-cutting themes were identified and subsequently coded. The authors’ different backgrounds were important in offering different frames of reference for judging what was “interesting” and what was not. The interaction between the two authors further served to reduce any tendency towards ethnocentric bias.

The analysis was especially sensitive to the different roles that the interviewees assigned to themselves, and how different roles served the needs of different storylines. The phenomenon of investigation in this respect related to the expressed self-identities of the interviewees. For example, special attention was given to the extent to which respondents’ storylines drew from official policy discourses, and any tendency to invoke broader historic events. However, there was no expectation that the interviewees would limit themselves to any single role, or indeed to any single expression of identity. The analysis was therefore open to the possibility of individuals offering alternative—and perhaps even contradictory—interpretations.

The assigned codes associated with the emergent themes were subsequently used to search for similarities and differences across the three different state-owned firms. In this instance, the focus of interest was on the extent to which the sensemaking processes exhibited by the interviewees may have been reflective of the firms’ different development trajectories. There was however a deliberate degree of iteration between the data and the themes as represented in the literature review. For example, the emphasis given to the concept of projectification was subsequently strengthened based on its perceived explanatory power. The reality is that complex processes of sensemaking often defy simplistic linear representation.

Findings

The findings can be seen to comprise the outcome of a collective and iterative process of sensemaking involving both researchers and participants. It should further be emphasized that the interview data considered important were inevitably shaped by the adopted theoretical perspective. The research deliberately sought to privilege processes of change from the outset, with a particular emphasis on the way issues are framed for the purposes of sensemaking. The broad justification lies in seeking to counter-balance the existing systemic bias towards assumed stability as observed within the current research literature. The following summaries are organized in accordance with the identified emergent themes. However, it should be recognized that the adopted structure of sub-titles represents a further act of sensemaking on the part of the authors

Embracing enterprise and competitiveness

Interpretations of the “firm”

Interviewees from all three case studies commonly referred to the “firm” in the sense of it being an “independent market entity”. This was often clarified in terms of the way firms are now commonly expected to win projects on a competitive basis. Hence the language and imagery of competitiveness have seemingly become naturalized in the way the respondents interpret the meaning of a “firm”. It is notable that interviewees from all three firms claim to have established so-called “project acquisition departments” for the purposes of winning work. Even more starkly, the managers involved in project acquisition are seemingly incentivized through performance-based bonuses. Hence the discourse of competitiveness permeates down even to the level of individual managers.

However, many interviewees were also of the view that state-owned firms would not ultimately be allowed to go bankrupt. There was a common belief that government officials would always intervene if state-owned firms found themselves in financial difficulty. One interviewee cited the followed example while being probed about how his firm survived a described period of difficulty in 2016:

“We owed the bank about 17 billion yuan, but we did not have the money to pay back the loans. The local government secretary organized three meetings for us to address our debts with the bank. If our firm were to go bankrupt, the bank would have definitely lost money. The bank also evaluated our background. Our firm had a good record; as a state-owned firm we will never fail. But what could we do if we could not pay back the loan? So, during these meetings, all state institutes that have guanxi with us were invited, including officials from the Supreme People’s ProcuratorateFootnote1 and Chongqing Municipal Commission of Housing and Urban-Rural Development. The government officials set a tone of supporting our firm and helping us to overcome difficulties. We made many agreements. I remember that the due date for the loans was postponed for two years, without interest.”

(Interviewee 22, former chairman of SCCHC)

The above recollection was by no means unusual. Several interviewees cited examples of government officials intervening to save state-owned firms from bankruptcy. Such interventions apparently often involve convincing banks to postpone loan repayments. Some referred to the direct allocation of projects to state-owned firms deemed to be in financial trouble. The term guanxi was also frequently used to explain the close connectivity between state-owned firms and various other agencies of the state. Moreover, the “father-son” metaphor was widely employed to allude to the continued dependence of state-owned firms on government support. The interviewees were clear that no such level of support is available for privately-owned contracting firms.

The role of the party

The interviews further highlighted the way in which the Chinese Communist Party (hereafter the “party”) continues to play an important role in the management of state-owned contracting firms. As part of their transition to quasi-independent market entities, ECCSC and NCCEC both sought to separate the responsibilities of strategic oversight from those of day-to-day management. The aim was to empower a professionalized cadre of managers to make operational decisions in accordance with the strategic direction set by a commercially-orientated board of directors. However, in practice, it seems that directors and managers are required to be members of the party. They hence perceive themselves to be obliged to follow government policy. It was notable that the party and the government are largely seen as synonymous such that the interviewees tended to use the two terms interchangeably. The interviewees consistently emphasized that they had a degree of flexibility in terms of how best to respond to policy, but it seems that strategic decision-making remains strictly controlled. In contrast, the interviewees from within SCCHC apparently enjoy a greater degree of freedom to make decisions because of its previous history as a privately-owned firm.

Notwithstanding the above, the interviewees from all three firms agreed that the role of the party had become increasingly prevalent in recent years. Several quoted various slogans relating to the importance of “following the party’s absolute leadership”. It would hence appear that, despite the advocacy of the socialist market economy, managerial decision-making is ultimately subject to approval by the assigned party secretary.

Industry restructuring

The interviewees readily recalled widespread changes to the employment relationship as part of the transition to a market-based economy. This was described most vividly by a senior manager from NCCEC, who recalled the re-structuring which took place in 2003:

“There were around 7,000 people working for the firm in those days. However, Mr. L. laid off almost the entire workforce, including many involved in the management team. Everyone then had to then compete for their own posts. This applied throughout the organisation - all cards were shuffled. This was a wall-breaking moment. It didn’t matter how strong a guanxi you had, no advantage was given to anyone. The result was that many capable staff were re-appointed. But those who had originally obtained the position solely because of guanxi were rejected. This is the point when NCCEC changed from being a traditional state-owned firm to a market-oriented state-owned firm.”

(Interviewee 41, Enterprise Strategy Department manager from NCCEC)

The above reference to a “wall-breaking moment” refers to the abandonment of the previously prevailing model whereby Chinese employers provided the workforce with through-life job security. Of further note is the way the interviewee positions guanxi in opposition to competitiveness. Many also referred to the introduction of performance-based salaries as a means of incentivizing managers. Several further referred to the creation of dedicated “human resource” (HR) departments as indicative of the transition towards enterprise. However, the abiding impression was that the restructuring process primarily resulted in lower-level staff being more easily dismissed, with relatively little impact on those who continue to perceive themselves in part as an officer-class cadre. One of the interviewees with specific responsibility for “human resources” (HR) openly described the continued use of quotas for management staff:

“In state-owned firm like ours, there are official personnel quotas. The phrase ‘manning quotas’ refers to the way that the state allocates quotas for management staff within state-owned companies. This is the real iron rice bowl in operation. Many management staff have been directly allocated through an algorithm. In contrast the workforce operatives tend to be only engaged on a temporary basis.”

(Interviewee 39, human resources manager of NCCEC)

Many interviewees referred to similar hybrid arrangements of this nature which are still being played out. However, the situation was again notably different within SCCHC where the senior managers tended to perceive themselves as employees in accordance with the Western model. In this case, they saw their jobs to be at risk should the company get into financial difficulties.

It was further notable that managers from within ECCSC and NCCEC tended to prioritize turnover over profit. This was readily evident in the way they consistently emphasized the importance of pursuing projects even if they were not expressly profitable. The interviewees also often claimed to be especially incentivized to pursue international projects. They were notably less clear on the extent to which such incentives were dependent upon the secured projects being profitable.

In contrast, the interviewees from within SCCHC consistently highlighted the importance of profit. They further argued that any increase in turnover without a corresponding increase in profit is undesirable. The roots of this stark difference in emphasis would seemingly again lie in SCCHC’s history as a privately-owned company. The emphasis on growing turnover by the other two firms would appear to be a carryover from the Soviet-style era of fulfilling mandatory quotas.

Perhaps most striking was the tendency of many managers from within ECCSC and NCCEC to prioritize the importance of following set procedures. The necessity to follow procedures would seem to be part of their inherited sense of self-identity as “cadres of the party”. However, several interviewees emphasized the importance of “following set procedures” while also stressing the importance of guanxi. Others again preferred to give primacy to the notion of “enterprise”. The overall picture would seem to be complex and contested. Much of this could be seen as identity work on the part of the interviewees.

Evolving practices of “project management”

Projectification as an instigator of change

The interview data readily reveals that terms such as “project” and “project management” have become part of the day-to-day language among those tasked with managing construction in China. When asked about the way construction was organized previously, many referred to “work areas” subject to control through a centralized “command post”. Some interviewees invoked an even stronger militaristic metaphor by referring to work areas as the “basic units for fighting”. Such phrases seemingly stem from the way construction was organized in the Soviet era. It is important to recognize that it is not the distinction in terminology in itself which is important, but the way that different phrases infer different systems and associated sets of beliefs. The terminology of project management implies the adoption of modern management techniques. Many of those interviewed cited the iconic Lubuge project from the early 1980s. This would seem to be indicative of a shared memory of the way the project was cited in a succession of policy announcements from the Ministry of Construction.

None of the above should be taken to imply that the interviewees shared the same understanding of project management as that which prevails in the West. Indeed, they tended to refer to “project management” primarily as a means of emphasizing the adoption of the project as the essential unit of production around which competition is organized. It is in this sense that the adoption of the terminology can be equated with ongoing processes of projectification.

Project management as a means of justification

The advocacy of project management was further notably used to imply a separation between those responsible for the management and those responsible for the physical task of construction. This frequently extended to a discussion of the contractual arrangements through which projects are delivered. It was on this basis that the interviewees started to draw distinctions between main contractors and subcontractors, and the possibility that project delivery may often depend upon multiple tiers of subcontractors.

In seeking to position themselves as main contractors, it is apparent that all three case study firms have undergone extensive restructuring, not least in terms of avoiding the fixed overheads associated with the retention of a directly employed workforce. This was seen by many to be an inseparable part of the transition towards “project management”. During the course of discussing the challenges of the transition to the socialist market economy, one interviewee offered the following view which was by no means untypical:

“We started to focus on management only as a way to reduce the burden. We now no longer need to pay for worker welfare issues such as pensions. This reduced the firm’s costs. Previously, we were required to pay the labourers’ wages every day, no matter whether they worked or not. But with labour subcontracting, we just pay for the days that the labourers work.”

(Interviewee 42, Safety Monitoring Department manager from NCCEC)

The above respondent notably justifies the outsourcing of labour in terms of “reducing the burden”. The implication is that construction workers are no longer part of the company’s core workforce. Of further note is the way many interviewees emphasized the increased reliance of their firms on labour-only subcontractors. Indeed, the transition towards “project management” was routinely offered as a justification for the way their firms had increasingly distanced themselves from the workforce. Several interviewees further conceded that they have also largely divorced themselves from the responsibility for training construction operatives. The notion of “reducing the burden” in the cause of competitiveness thereby seemingly becomes inseparable from the adoption of project management.

Relationships between head office and site-based project managers

Several interviewees also described the changing in-house relationship between on-site project teams and head office departments. Ironically, the latest trends in “project management” were seen by some to be reducing the autonomy of site-based project managers. The interviewees from NCCEC tended to use the phrase “functional line management” to imply ever-increasing head office control over the way in which projects were managed. Cited examples included centrally-based functional departments, such as accounting, HR, safety management, and quality management. There was also a widely observed tendency for issues of contract management to be determined centrally. Interviewees from within ECCSC notably used the phrase “centralized management and control”. Cited examples included project funding and the selection of subcontractors and material suppliers. Some interviewees referred to the way project bank accounts are increasingly managed by centralized finance departments, with project accountants being responsible for the approval of project managers’ expense accounts.

The above-described trends towards centralization were unsurprisingly welcomed by those based in head office functions with corporate responsibilities. A shared perception was that project managers had previously been allowed too much autonomy. Hence the observed trend towards relocating responsibility for decision-making to functional departments. In the words of one interviewee:

“The relationship between the firm and project management teams was previously too loose. Project management teams had too many rights. Since 2003, functional management has been promoted to reduce the autonomy of the project managers. It is like the relationship between national and local tax bureaus. Once you take control of the capital, you can control the project management team. Project capital was gradually centralized.”

(Interviewee 39, deputy general manager in charge of project management from NCCEC)

Interestingly, the issue of shifting responsibilities was hardly mentioned by the interviewees from SCCHC. The impression gained was that SCCHC operates on a much more decentralized model.

Interpretations of “bidding and tendering”

Loss of control

The interviewees’ engagement with bidding and tendering was initially explored by inviting them to describe how their companies secured work. There was a common recognition of bidding and tendering as important mechanisms of market competition. There was also a widespread implicit acceptance of the project as the essential unit of production. It was further acknowledged that bidding and tendering should apply not only to the appointment of the main contractor but also to the appointment of sub-contractors throughout the supply chain. Opinion however was more mixed on the extent to which bidding and tendering are consistently applied in practice. Several interviewees alluded to the ongoing possibilities of “workarounds”.

When asked to reflect on the broader rationale for the introduction of competitive bidding and tendering, the interviewees would typically cite the Open Door policies of Deng Xiaoping. These were seen to have been important in “paving the way” towards the current mode of working. Most saw the introduction of market competition as having had a fundamental influence on the way their firms were organized. The interviewees again often alluded to the loss of control that had resulted from the introduction of bidding and tendering. This was an especially recurrent theme when talking about the appointment of sub-contractors:

“Prior to the introduction of bidding and tendering, the project manager had the right to choose sub-contractors and decide the price. They had perhaps even too much autonomy. But now it is the market that decides how to distribute work, not the project manager.”

(Deputy General Manager, ECCSC)

Those in general management functions were notably more supportive of the above-described trend than was the case for site-based project managers. For the latter group, the introduction of bidding and tendering is seen as impinging upon their autonomy to appoint their preferred sub-contractors. Several interviewees were still trying to come to terms with these changes, not least in terms of the implications for their own personal career trajectories.

Continued importance of Guanxi

Following on from the above, there were several interviewees who felt that bidding and tendering is primarily a bureaucratic process that is disconnected from the way decisions are made in practice. The concept of guanxi was widely held to be of central importance in understanding how business operates in China. Several interviewees saw it as the preferred means of operating. Perhaps most importantly, many also saw it as a means of retaining control despite the introduction of market competition. Several suggested that clients also often select a preferred contractor on the basis of guanxi, thereafter manipulating the tendering process to confirm the required outcome. In the words of one manager:

“If our guanxi is just normal, the client may only give you enough information about the project to enable you to prepare. But if the guanxi is good enough, the client may adjust the bid documents to favour our firm.”

(Interviewee 33, Marketing Department manager from SCCHC)

The advantage of gaining privileged access to tender information was a theme highlighted by several interviewees. Indeed, there was a broad consensus that the information provided by clients at the time of tender is very often incomplete. This in turn was seen to enable clients to use information as a means of ensuring the desired outcome:

“We are still working on this project. Our guanxi helped us to get involved, but we are still discussing conditions. If the client favours you, they will give you more information than the others. The chances of winning the bid then become bigger.”

(Party secretary of engineering subsidiary from ECCSC).

Several interviewees further emphasized that tenders are not routinely awarded to the lowest bidder. Some clients were reported to follow a policy of awarding the project to the bidder whose price is closest to the client's own in-house estimate. On other occasions, the project is reportedly awarded to the bidder whose price is closest to the average. Both approaches are held to be open to abuse. In the first case, the challenge for the contractor is to ascertain the value of the client's own in-house estimate. The contractor in possession of this information is most likely to be successful. What apparently tends to happen is that clients simply leak the required information to the preferred bidder. In the second case, there is an opportunity for collusion among pre-qualified contractors to determine whose “turn” it is to be successful. Collusion of this nature seemingly often takes place with the tacit approval of the client. The view seems to be that, despite policy recommendations in favour of bidding and tendering, guanxi continues to play an important role in determining which contractor is awarded the contract.

The process of building and maintaining guanxi with targeted clients was seen by some interviewees to be the primary role of the relatively recently created marketing departments. Typical activities were seen to include entertainment, hospitality, and site visits. All such activities are apparently aimed at preserving an “inside track” with identified clients. Others were very resistant to the idea that guanxi could in some way be limited to any particular department. Indeed, the majority tended to see guanxi as a resource that was developed and nurtured by individuals. Hence many managers were jealous of attempts by marketing departments to claim guanxi as a specific source of expertise.

Discussion

Methodological reflections

Initially, it is important to emphasize that the above findings are representative of sensemaking in flight. It is also important to recognize that the narratives mobilized by the interviewees were inevitably influenced by the presence of the interviewer. Although care has been taken fairly to represent the views expressed, choices have inevitably been made in terms of which issues to highlight, and which to ignore. The narrative within which the findings are presented should therefore be understood as the outcome of a collective sensemaking process (cf. Allard-Poesi Citation2005).

It must further be understood that the world views of the interviewees are formed through their daily sensemaking interactions with other actors, including clients, subcontractors, and government officials. All such parties utilize different frames of reference and hence seek to make sense of the unfolding reality of the socialist market economy in different ways. The interactions which took place during the research undoubtedly differ from those which characterize the everyday working lives of the participants. They can further be understood as triggers for “second-order” sensemaking which extends beyond that which takes place when actors are engaged in routine activities (aka “immanent” sensemaking) (Sandberg and Tsoukas Citation2020). The interviewees were notably held to account in terms of the plausibility of their interpretations in ways that would be unusual in their day-to-day working lives. The contention that the interviews initiated a greater degree of self-refection was often notably reflected in the responses of the interviewees. The elicited narratives should not however be viewed as being representative of a fixed external reality—hence the adopted phraseology of “sensemaking in flight” as a means of emphasizing their essential temporality.

Sensemaking in practice

Notwithstanding the above, the reported findings offer unique insights into the participants’ transient processes of sensemaking which are seen to be synonymous with the micro-practices of organizing. The research question around which the study was framed sought to explore the extent to which such practices are shaped by the policy imperatives of the socialist market economy. As with all such exploratory research questions, it is not easily answered in a single sentence. Nevertheless, the research clearly highlights the real-world issues that practising managers are engaging with on a day-to-day basis. It sheds light on how practitioners seek continuously to position themselves within the context of an unfolding reality. The intrinsic processes of sensemaking can further be seen to comprise a continuous process of adjustment as pre-existing frames of reference are forever challenged and revised in response to lived experiences.

The findings further point towards the inherent conflicts and paradoxes that practitioners must reconcile daily. The interviewees frequently aired inconsistent views, even sometimes shifting opinions over the course of the interview. For example, several emphasized the importance of adhering to procedures, while at the same time maintaining the continued importance of guanxi. In highlighting such paradoxes, the findings are held to be more realistic than those offered by previous research studies which focus on fixed, and supposedly, representative “factors” (e.g. Li et al. Citation2009, Zhao et al. Citation2013, Yan et al. Citation2019). The presented research also differs in the way it ascribes agency to individual participants. Rather than seeing organizational actors as passive recipients of top-down policy, the research accentuates the active role that individuals play in imposing a degree of order on the complex environments within which they operate—otherwise construed as sensegiving. The research is further notable for resisting more deterministic interpretations of the supposed impact of “national culture”.

The research confirms that managers have seemingly accepted the essential narrative that construction firms in China must actively compete to win projects. This was seen by many to have directly impacted the way they are incentivized through performance bonuses. Paradoxically, there was also a widely held belief that state-owned firms will in the end not be allowed to fail. There was also an acceptance that decision-making is ultimately subject to approval by assigned party secretaries. The interviewees were however acutely aware of the extensive structural changes which had taken place in the Chinese economy since the advent of the Open Door policy. This was seen as the essential backdrop to the espoused need for firms to make themselves “competitive” and for individuals to take responsibility for their own careers.

The findings provide support for Chen and Partington’s (Citation2004) view that the interpretation of project management in China is very different from that which prevails in the West. Indeed, the notion of project management in China would seem to be just one component of a broader, and highly flexible, narrative structured around competitiveness. The need to adopt modern project management practice was repeatedly used as a justification for the wholesale shedding of direct labour, otherwise construed as “reducing the burden”. In this respect, the radical re-structuring of the Chinese construction sector generates very similar sensemaking narratives to those which prevail in liberalized capitalist economies, such as the United States, the United Kingdom, and Australia. Of course, none of these have quite experienced the same radical changes as experienced by China, and they are notably underpinned by more robust independent legal systems. But there are nevertheless points of commonality as well as important points of difference. An obvious point of commonality is that the management of construction has become ever more projectified.

Sensemaking as a proxy for organizing

The restructuring of the Chinese construction sector can further be seen to have had direct and ongoing consequences on the way construction firms are organized. Of particular note is the apparent creation of a plethora of centralized departments with responsibility for areas such as accounting, HR, safety, and quality. The titles of these departments are of interest in themselves in that they are derived directly from the lexicon of modern management. However, there is little reason to believe that these departments will remain stable over time. A more likely scenario is continuous (re)organization over time as firms seek to re-position themselves in response to a forever changing competitive landscape (cf. Green et al. Citation2008, Leiringer et al. Citation2009). The tensions expressed by the interviewees regarding shifting roles and responsibilities are therefore likely to be continuously replicated and reconfigured over time. The balance of power between different departments and site-based project managers will be forever subject to ongoing processes of sensemaking. Hence sensemaking is not seen to be something that takes place independently from the ongoing activities of organizing (cf. Nicolini Citation2012).

The described tendencies towards continuous re-organizing are severely underrepresented in the literature which relates to the organization of construction in China (e.g. Lu et al. Citation2008, Li et al. Citation2009, Zhao et al. Citation2013, Yan et al. Citation2019, Niu et al. Citation2020). The current paper highlights an alternative approach to research that is not dependent upon the use of questionnaire surveys to identify critical success factors. The research illustrates how underlying assumptions of fixity and stability are of limited relevance for understanding the micro-practices of project organizing (cf. Nayak and Chia Citation2011).

Paradoxes, ironies, and competing identities

One of the key findings of the current research is the way that bidding and tendering are often perceived as merely bureaucratic processes which are routinely circumvented. Managers are required to adhere to compulsory bidding and tendering as a matter of policy. Yet in practice, they seemingly go through the motions of complying while engaging in as many workarounds as possible. This tendency would appear to be systemic rather than isolated to a few individuals, although caution is necessary about extrapolating beyond the sample. Of particular note is the recurring suggestion that bidding and tendering are mediated by habitualized practices of guanxi. The overriding motivation however seems to be a fear of losing control, rather than any crude notions of corruption. The practices portrayed are perhaps best understood as localized—and pragmatic—responses to the unfolding policies of the socialist market. The transition towards the socialist market economy is not only about the introduction of market mechanisms, but also about the extent to which such mechanisms co-exist with pre-existing practices (cf. Bresnen and Marshall Citation2001). Guanxi seemingly operates as an insurance scheme for those who have it, and a barrier to entry for those who do not.

The constituent practices of guanxi are held by many to be culturally embedded in China such that they permeate throughout society (Park and Luo Citation2001). The important empirical finding is that guanxi is continuously mobilized as a means of sensemaking, with direct material consequences. It should further be remembered that contracting firms in the West also often seek to develop an “inside-track” with clients to avoid the need to engage in “hard-ball” competitive tendering. The cultivation of business contacts is widely recognized as good marketing practice globally. Indeed, many large contracting firms in the West notably pronounce on the virtue of competitive markets while at the same time doing everything possible to avoid exposure to competition. Paradoxes and ironies of this nature are hence by no means unique to China.

The described research has especially highlighted the tensions which exist for individual managers as they struggle with competing identities. Some strive to follow set procedures as “cadres of the party” while at the same time aspiring to be entrepreneurs. Others strive to position themselves as purveyors of modernity while adhering to long-established practices of guanxi. Such identities are forever fleeting and continuously tested through social interaction. Sensemaking processes can hence be seen as the means through which practicing managers develop and maintain a positive sense of self-identity (Weick Citation1995). In this sense, the interviews were not only sensemaking encounters, they were also arenas for identity work. The research participants were testing out tentative identities through their interaction with the researcher, just as they do with a multitude of other actors in their day-to-day interactions (cf. Cornelissen Citation2012). Sensemaking and identity work are hence inseparably intertwined. The way individuals make sense of the world is dependent upon their sense of self, and the collective identities to which they see themselves as belonging (cf. Brown et al. Citation2015).

Conclusions

The described research has provided new insights into the micro-practices of project organizing as enacted by middle managers in the Chinese construction sector. The adopted theoretical lens has served to accentuate notions of fluidity and change, rather than perpetuate established tendencies within the research literature to prioritize stability and permanence. Practising managers have been seen to engage in continuous processes of sensemaking as they seek to position themselves within the context of an ever-changing reality. The empirical findings serve to highlight the routine day-to-day challenges of managing the transition to the socialist market economy. The research also illustrates how sensemaking can be used as a means of bridging between macro-level policy narratives and micro-level practices.