Abstract

To improve the performance of construction projects, the use of relational contracting (e.g. Project Partnering, Alliancing, Early Contractor Involvement, Integrated Project Delivery) has increased among public clients in the last few decades. Despite widespread use, there are still large variations in contracting arrangements. In addition, the outcome of relational contracting remains unpredictable. The aim of this paper is to investigate how these variations may originate from internal dynamics and practices in the project-based client organisation. Adapting organisational routines as an analytical lens, the study investigates the pre-procurement routine applied to develop project-specific relational contracting models (e.g. contract schemes, reward systems, and award criteria) for large construction projects in the Swedish Transport Administration. The study contributes to research on organisational routines in project-based settings, illustrating how flexible enactment of a pre-procurement routine may balance two conflicting organisational goals: centralisation of procurement and project-level flexibility. However, while mitigating conflicting goals, the routine enactments create a variation in project-specific procurement models that hampers long-term goals of predictability and shared practices of relational contracting. Consequently, findings indicate that public clients seeking to transform contracting practices must increase their ability to develop procurement routines that can balance organisational goals and simultaneously benefit long-term goals.

Introduction

During the last few decades, public clients have increasingly applied relational contracting to tackle growing demands of efficiency and improve the performance of large complex infrastructure projects (Flyvbjerg Citation2014, Davies et al. Citation2019). Clients play an important role in these interorganizational projects, as they select the organisational and contractual governance structures of the delivery and procurement models (Manley and Chen Citation2016, Volker and Hoezen Citation2017, Davies et al. Citation2019). Nevertheless, despite the widespread use of different forms of relational contracting—partnering, alliancing, integrated project delivery (IPD), Early Contractor Involvement (ECI), etc., there continues to be large variations in definitions, contract forms, and reward systems (Phua Citation2006, Hall and Scott Citation2019), and project outcomes are still unpredictable, even for repeat clients (Manley and Chen Citation2016). This variation constitutes both a practical and a theoretical problem, as it hampers the predictability of interorganizational projects and makes it hard to transfer lessons learned between projects and geographical locations (Walker and Lloyd-Walker Citation2015).

Public clients are often seen as important change agents in the construction sector (Nam and Tatum Citation1997, Kulatunga et al. Citation2011, Bonham Citation2013). However, other studies have questioned this simplistic view of clients and their ability to drive sector-wide change (see for example, Manley Citation2006, Hartmann et al. Citation2014, Lindblad and Karrbom Gustavsson Citation2020). Public clients are especially large and complex organisations (Winch and Cha Citation2020), with often-contradictory internal goals and values (Brunsson Citation2007, Kuitert et al. Citation2019).

Therefore, talking about “the client” may be misleading, as different parts of an organisation have different goals. In addition, repeat clients are generally project-based; that is, much of their activities are performed in projects, and the project dimension of the organisation is privileged (Söderlund Citation2015). One challenge that project-based organisations face is the need to balance integration and the centralisation of project activities in the parent organisation with flexibility at the project level (Sydow and Windeler Citation2020). Because of the tension between larger organisation-level centralisation and autonomy and flexibility at the project level, project-based organisations often struggle to implement even internal top-down change (cf. Bresnen et al. Citation2005a). In effect, the organisational structure of public clients limits their prospects of changing their own practices, as well as those of others.

Lately, the importance of organisational routines in project-based settings has been highlighted by several authors studying construction projects (cf. Addyman et al. Citation2020, Bygballe et al. Citation2020, Cacciatori and Prencipe Citation2021, Hedborg et al. Citation2020). More specifically, this research has highlighted the important role routines play in managing the particular tension between flexibility at the project level and the demand for consistency at the organisational level (Annosi et al. Citation2020, Bygballe et al. Citation2021).

Studies on relational contracting that explicitly apply the construct of organisational routines often focus on interorganizational routines in construction projects (see for example, Söderlund et al. Citation2008, Bygballe and Swärd Citation2019, Addyman et al. Citation2020). However, to better understand how shared practices for relational contracting can be developed, internal routines to establish the project-specific relational contracting models, such as in the purchasing department, should be of particular interest, since they serve as a type of intermediary between internal and external goals (Moretto et al. Citation2020). Plantinga et al. (Citation2020) show how purchasing department structure and the lack of integration mechanisms in operational departments can be another explanation for the inability to reuse innovative procurement models in public infrastructure client organisations. Furthermore, centralisation of procurement is a general trend in the public sector, although it is not always supported at the project level (Witzell Citation2019). As these studies show, the relationship between central purchasing departments and project level has an impact on the procurement activities of public project-based client organisations; however, they do not further investigate the specific role organisational routines have in mitigating internal goals between procurement and operational departments, or explain variations in project-specific procurement models. The aim of this paper is therefore to investigate how these variations may originate from internal dynamics and practices in project-based client organisations.

The empirical case under study is an internal organisational routine in a public, project-based client organisation; namely, the pre-procurement routine applied in the Swedish Transport Administration (STA) to develop project-specific procurement models in large infrastructure projects applying a novel ECI framework. The study focuses in particular on how conflicting organisational goals can be balanced through routine enactment and the influence this balancing role has on routine output. The paper investigates the following research questions.

How does routine enactment of a pre-procurement routine balance different goals in a public project-based client organisation?

How does routine enactment influence relational contracting model variation?

The study shows that procurement routines balance the internal conflict between centralisation of procurement activities and perceived project-level flexibility needs. The result is a flexible routine that results in variations in routine output (i.e. project-specific procurement models) that influence developments in shared relational contracting practices at the sector level. This article therefore contributes to research on construction management—especially with respect to public clients and how internal structures and activities influence the potential to change contracting practices in the infrastructure sector. Furthermore, the paper contributes to the concurrent discussion on the role of organisational routines in project-based settings by illustrating how an organisational routine in a project-based organisation may have two-fold effects. Although this routine enactment provides internal balance to an organisation, flexibility in routine output can hamper client predictability on a sector level.

The paper is structured as follows: the next section introduces the concept of relational contracting, followed by a theoretical background on organisational routines in project-based settings. The methodology of the paper is then described, followed by a description of the empirical findings and a discussion of the role that routine and routine output play in balancing conflict in the STA and how they influence the development of relational contracting practices.

Theoretical foundation

Developments of relational contracting in the infrastructure sector

Many public clients face a dual challenge: on one hand, the increased organisational and technical complexity of infrastructure projects (Flyvbjerg Citation2014, Eriksson and Kadefors Citation2017) and, on the other, decreasing resources to produce public infrastructure (Hartmann et al. Citation2014). With this change in the policy environment, clients and contractors have identified potential value in moving away from traditional adversarial relationships towards contracts and delivery models that emphasise the relationship between the contractor and the client (Bresnen and Marshall Citation2010, Davies et al. Citation2019).

In general, relational contracting in the infrastructure sector implies that projects combine reward systems designed to promote collaboration, quality-based procurement, risk sharing between clients and contracting parties, formalised relationship management (covering collaborative activities in projects), and the integration of design and production (Walker and Lloyd-Walker Citation2015). Although many studies point to the benefits of relational contracting, the picture is not straightforward (Bygballe et al. Citation2010, Gadde and Dubois Citation2010). There is still great variation in the terms used to describe different forms of relational contracting, or innovative collaborative delivery models (Phua Citation2006, Lahdenperä Citation2012, Hall and Scott Citation2019). Furthermore, the specific practices, contracts and procurement arrangements also differ (Bresnen and Marshall Citation2010, Hall and Scott Citation2019). Substantial variations in relational contracting arrangements create confusion and decrease the possibility of learning and developing shared models (Walker and Lloyd-Walker Citation2015).

Davies et al. (Citation2019) suggest that repeat clients, for example, the Ministry of Infrastructure and Water Management in the Netherlands, the Highways Agency in England, or the Swedish Transport Administration, have the potential to learn over time and improve their delivery models for subsequent projects. However, developing routines for an innovative procurement model is a complex process, as different parts of the organisation have different intentions when introducing new routines (Davies et al. Citation2018). Plantinga et al. (Citation2020) reach similar conclusions, showing how the lack of strategic practices in the purchasing department decreases the possibility that the public client organisation will move away from “one-off” innovative procurement models.

Implementing relational contracting is both an intraorganizational and an interorganizational process. In a first step, the client organisation internally selects the project’s organisational and contractual governance structures. Later, the project-specific relational contracting model serves as an input for interorganizational collaboration with suppliers. Therefore, a larger transformation of contracting practices must be a co-development process within the wider sector; a process often underestimated by public clients who tend to emphasise internal work (Hartmann et al. Citation2014).

An increasing body of literature does point to the importance of trust between parties in interorganizational contractor–client relationships (for a recent example, see Ruijter et al. (Citation2020)). Although trust can be built during the project, the level of initial trust—based on institutionalised trust in roles and systems—is based on predictability (Grabher Citation2002). Consequently, the role and structure of the purchasing department in a project-based organisation are important for the impact of the organisation on the supply chain (Moretto et al. Citation2020). For public clients, these structures are often conditioned by politically-introduced procurement policies (Patrucco et al. Citation2019). Thus, to understand the impact a public client may have with their procurement, and how consistency and predictability may be realised, it is essential to investigate organisational routines to develop procurement models, as they are a bridge between external predictability and internal dynamics in the organisation.

Organisational routines in project-based organizations

Organisational routines are essential for the survival of organisations and can be described as doing ”something in and for the organisation” (Feldman et al. Citation2016), i.e. to complete tasks or make decisions. Organisational routines are often defined as ”repetitive and recognisable patterns of interdependent actions carried out by multiple actors” (Feldman and Pentland Citation2003), and the actors involved in the routine are the “routine members” (Feldman et al. Citation2016). Although routines have been described as reflections of organisational memory and sources of inertia (Levitt and March Citation1988), Feldman and Pentland (Citation2003) show how routines also serve as a source of flexibility and change, by emphasising the importance of individual agency in routine performance and dependence on individual actions that are locally situated (Cohendet and Llerena Citation2003). Agency can in this context be described as the possibility that individuals have to pursue intentional activities to satisfy their own needs and goals (Giddens Citation1984, Johnson Citation2008).

Viewing routines as dynamic, they embody both structural and individual elements, often described in terms of an ostensive and enacted dimension (Feldman and Pentland Citation2003). Or, in other words, the routine in principle and the routine in practice (Bygballe and Swärd Citation2019). However, the ostensive aspect should not be considered static, but rather something that is also recreated and developed (Feldman et al. Citation2016). For example, the ostensive aspect may vary with time and place, and this will influence both routine enactment and development (Davies et al. Citation2018). Additionally, routine enactment often needs to balance a requirement for consistency with a demand for flexibility to adapt to changes in the context (Turner and Rindova Citation2012).

Flexible enactment and the influence of agency

In line with the new view on organisational routines proposed by Feldman and Pentland (Citation2003), the intentions of routine members influence routine performance. Howard-Grenville (Citation2005) illustrates this phenomenon in her study of a “road-mapping” routine. Each occasion the routine was enacted, individuals’ actions were based on their own intent for, and understanding of, the routine, and they could iterate, develop from, or practically evaluate previous enactments (Emirbayer and Mische Citation1998). As a result, both the enactment and routine output varied, although the overall routine lasted over time. The possibility of performing organisational routines in a flexible manner varies according to the power and legitimacy of the individual in the organisation (Feldman and Pentland Citation2003); for example with individual experience (Danner-Schröder and Geiger Citation2016). This should hold particularly true in the construction sector where individual responsibilities are considerable (Johansson Citation2012) and enabled by institutionalised roles that make actions predictable (Kadefors Citation1995). To what extent the routine is integrated with other routines within their relevant contexts also influences the possibility to pursue agency (Howard-Grenville 2005). Accordingly, organisational routines in project-based organisations endure if they are anchored locally by professional communities (Bresnen et al. Citation2005b).

Regarding the structures of project-based organisations with strong autonomy and professional groups at the project level, Bygballe et al. (Citation2021) suggest looking more closely at the role of agency in shaping routine enactment, since project autonomy is not passive or “given”. Rather, it is through individual agency that autonomy at the project level is created and changed with respect to rules and resources in project settings (Willems et al. Citation2020).

Conflicting goals and multiple ostensive aspects of routines

A routine may have more than one ostensive aspect (or pattern) (Turner and Rindova Citation2012), as routine intentions may vary between different departments (Salvato and Rerup Citation2018), or actors (Howard-Grenville Citation2005). In their recent study, Salvato and Rerup (Citation2018) examine the role of routines in balancing organisational goal conflicts. They find that the enactment of a “product development” routine constitutes a flexible process of mitigating between multiple ostensive aspects. In their case, the routine provided the arena to reconcile different visions of artistic standards and production efficiency. To the end, this routine enactment resulted in profitable products with high artistic value. Routine enactment thereby differs depending on the routine members’ contact with other departments, and it creates space for opposing views to find common ground in each enactment of the routine.

In a similar vein, Davies et al. (Citation2018) describe how procurement routines are recreated between different projects in a large client organisation (Highways Agency in England) and highlight how routines are developed and created for different purposes by different organisational levels. The strategic units were more focussed on, for example, standard results across sites, where the operational units were more focussed on trying to achieve the task and solve the issues at hand.

Bridging role of artifacts

Artifactual representations of routines (e.g. descriptions, formal rules, or routine output) also influence routine performance and constitute the third pillar of the concept of organisational routines apart from the ostensive and enacted dimensions (D’adderio Citation2011, Turner and Rindova Citation2012). In their study of a public client organisation, Davies et al. (Citation2018) suggest that artifactual descriptions of routines served different purposes in the strategic units and operational departments. Strategic units used contracts to articulate and guide routine performance, while operational departments had to translate this into action. The descriptions helped the operational departments orient their actions, but did not specify in detail how routines could be enacted (Davies et al. Citation2018). This facilitated the organisation in balancing efficiency—a goal of the strategic department—and flexibility in operational departments.

Balancing the necessary flexibility at the project level with the consistency of organisational activities is a challenge. Brady and Davies (Citation2004), in their work on organisation-led and project-led learning, emphasise that in developing economies of scale, some projects in project-based organisations may apply standardised models, while others can employ this flexibility in innovation. However, when all projects enjoy an extensive level of flexibility, they can lead to innovations that will not endure in the long term (Dubois and Gadde Citation2002a). Nevertheless, as mentioned, flexibility should not be seen as existing in opposition to integration and stability. Instead, flexibility can be structurally enabled and help encourage organisational routines to survive (Turner and Rindova Citation2012, Danner-Schröder and Geiger Citation2016).

This review of extant literature illustrates, first, that flexible routine enactment and the role of agency seem to be particularly important when studying routines in project-based settings (both regarding intraorganizational routines and interorganizational routines). Second, the ostensive aspects of routines may vary, and their enactment may have to balance internal conflicts. Finally, the role artefacts play as a bridging tool between different departments that may enable flexibility within certain boundaries in a project-based organisation, should be emphasised. The conclusion here is that routines dynamically balance conflicting organisational goals, and this should be particularly interesting to investigate in project-based organisations, where project goals may differ from the long-term goals of the organisation (Brady and Davies Citation2004, Sydow and Windeler Citation2020, Willems et al. Citation2020, Bygballe et al. Citation2021).

Method

Research setting

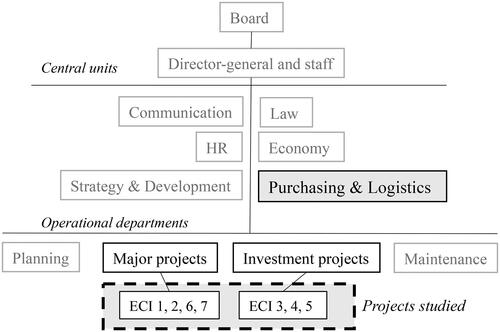

This paper investigates a pre-procurement routine that was applied in the Swedish Transport Administration (STA) on seven construction projects, hereafter called ECI1–ECI7 (see for an organisational scheme). The STA was formed in 2010 by a merger of the Swedish Railroad Administration and the Swedish Road Administration, and the procurement process has played an increasingly important role. The government’s instruction to the agency in 2010 specified that the STA would primarily be a procuring client authority. In a governmental report on increased productivity (SOU 39 Citation2012), it was suggested that increased contractor responsibility and a more distant relationship with project contractors supported market-led innovation. This resulted in an internal policy called “pure client”, and a principle that 50% of construction contracts should be procured using design-build contracts. The “pure client” policy was broadly communicated during the first years of the newly formed organisation.

Figure 1. Organisational chart of the STA. Departments included in the study are coloured in grey.

In 2016, the STA’s Purchasing and Logistics department (hereafter called the purchasing department) developed a newly formalised procurement strategy and pre-procurement routine to make decisions on procurement design and formalise contract documents. This strategy was communicated to project staff in internal educational workshops. Although the new procurement strategy was still based on the idea of supporting market-led innovation, it suggested that procurement should be based on project characteristics (similar to ideas proposed by Eriksson (Citation2017)).

Depending on the character of the project, different combinations of contracting arrangements, reward systems, and levels of collaboration were proposed. Furthermore, the new procurement strategy included the option of applying a new relational contracting framework with Early Contractor Involvement (ECI) to complex projects. At this time, relational contracting was something new in the STA and between 2014 and 2016 a two-stage ECI framework was developed by the purchasing department. Stage 1 aims to finalise the design and agree on a target price for further production in Stage 2. This is similar to the ECI model applied in the UK by the Highways Agency in England (Eadie and Graham Citation2014). However, as the ECI framework developed by the purchasing department in the STA only stipulates certain overarching conditions, the focus of this study is how the pre-procurement routine was enacted in each project to establish a detailed project-specific procurement model (e.g. contract schemes, reward systems, award criteria). A table summarising the project-specific procurement models for ECI1-ECI7 can be found in Appendix 1.

The project-specific procurement models for ECI 1 and 2 were developed in parallel to the framework. They essentially served as pilot projects.

Research approach

The study described in this paper is part of a longitudinal research project following the introduction of relational ECI contracts in the Swedish Transport Administration (STA). The seven projects, ECI1–ECI7, were included in the case study, as they represent the entire body of construction projects that have applied the ECI framework within the STA.

A case study approach was chosen because it allowed for a deep understanding of the setting and for the possibility of analytical generalising from the empirical material by elaborating on existing theory (Ketokivi and Choi Citation2014).

The case can be described as the use of ECI as part of STA’s procurement strategy. The initial approach was inductive; later the study was narrowed down to focus on the role of organisational routines. The unit of analysis is therefore the organisational pre-procurement routine implemented within the organisation. The case aims to explain variations in relational contracting, and the empirical material was collected in several projects; therefore, the study can be described as an explanatory longitudinal cross-project case study (Martinsuo and Huemann Citation2021) of routine enactment at the project level. As such, the organisational routine itself serves as the unit of analysis, and the seven projects jointly form one single case study.

Empirical material was collected over time and in several organisational departments and projects, which generated process data (Langley Citation1999). To make sense of the material, temporal bracketing—i.e. reorganising timelines into distinct phases of certain activities—was applied to clarify the actions taken in each project and their connections to other projects (ibid.). Similar to other studies in project-based settings applying a routine lens, the processual aspect of the case is present in the findings section more in terms of a narrative (Brunet et al. Citation2021), illustrating how the routine played out in practice as the conflicting goals within the STA unfolded over time.

Empirical material and data collection

The empirical basis of the case comprises interviews, organisation, and project-specific documents, and a small number of observations made when visiting the projects (see for a summary of the empirical material).

Table 1. Summary and description of case data.

This article is predominantly based on a detailed analysis of 29 semi-structured interviews with 24 respondents from the client organisation (see ), as well as the procurement policy, procurement strategy, and ECI framework developed by the purchasing department (see ). Interviews were carried out at the seven project sites and in central departments (Major Projects Department and Purchasing Department) from early 2017 to early 2021. Respondents were purposely chosen based on their role in the projects and in the organisation (Miles and Huberman Citation1994). All interviewees have been assigned an abbreviation (shown in ) that is used for quotations.

Table 2. Interviews in the client organisation.

Interviews were semi-structured and lasted an average of 72 minutes, with a range of between 40 minutes to three hours. They focussed on (1) the development of project-specific contracting models, (2) expectations and experiences of project practices, and how previous projects and established policies shaped project-specific procurement models, and finally (3) the role of a project’s overarching structure and support from central units. Material from the first category of questions provided the study with project members’ descriptions of the pre-procurement routine. The material from the second category of questions provided accounts of how personal experiences and informal contacts with other projects were essential in the development of project-specific procurement models, although it was not part of the formal description of the routine. Finally, the third category of questions, covering overarching structures and support from central units, was vital in understanding how the routine was performed, as these questions provided the (sometimes conflicting views) of central procurement policies and the role of the purchasing department for developing relational contracting practices. In addition, we analysed documents, namely artifactual descriptions of routines and project-specific procurement models. The document analysis was important to triangulate the interviews and build a more comprehensive understanding of the pre-procurement routine (Stake Citation1995).

A large part of the empirical material consists of policy documents (procurement policies and strategies, governmental instructions) and descriptions of the routines studied (descriptions, guidelines). In addition, field notes from an educational workshop held by the purchasing department on procurement strategy (including informal conversations with other participants) are included in the analysed material.

Analysing the empirical material

Initially, the analysis was interpretive and steered by the empirical material and the interviewees’ experiences during the implementation of the new ECI framework. This initial analysis narrowed down the importance of the pre-procurement routine. In the later stages, the analysis moved back and forth between the empirical material and the literature (Dubois and Gadde Citation2002b, Gioia et al. Citation2013). This allowed for elaboration as to how routines can function as intermediaries between integration in the parent organisation and project-level flexibility in project-based organisations; i.e. in balancing conflict in the client organisation. The theory section, therefore, specifically centres around the theoretical underpinnings of the aggregated themes.

When analysing longitudinal or process data, several qualitative analytical tools were applied to make sense of the case (Gehman et al. Citation2018). The different analytical phases can be summarised in the three phases described below.

Phase 1: Identifying the pre-procurement routine through project narratives

During data collection in the overarching longitudinal study, material was continuously read to identify themes and understand the implementation process of the new ECI framework, which resulted in an initial analysis (Miles and Huberman Citation1994) consisting of seven project descriptions/narratives, all based on interviews, observations, and project-specific documents. Through temporal bracketing (Langley Citation1999) of the project narratives, empirical material was divided into two general phases: The pre-procurement phase (including the client organisation) and the interorganizational project (including the contractor). This particular study addresses the pre-procurement phase and, therefore, centres around the actions, experiences, and thoughts of the members of the client organisation. Furthermore, within the pre-procurement phase, four subordinate temporal phases were identified (in the bracketing process these phases were named: initial procurement phase, explorative phase, interpretative and integration phase, and finalising phase). The similarities of the pre-procurement process in all seven projects made it possible to identify a distinct organisational routine enacted to develop the project-specific procurement models (i.e. the pre-procurement routine studied in this paper).

In parallel with the temporal bracketing, all interviews (29) were continuously coded in NVivo from the beginning, applying the Gioia method (Gioia et al. Citation2013) as a frame of reference; i.e. codes were empirically derived, and the experiences of the interviewees guided the analysis. The initial coding (indicating different views on the role of the purchasing department and the level of project autonomy), together with the differences between the projects’ procurement models (albeit procured within the same ECI framework), spurred an inquiry as to how this diversification was possible in this large and bureaucratic organisation. The study’s focus subsequently narrowed down to specific pre-procurement routines.

Phase 2: Identifying enacted patterns of the pre-procurement routine

The statements in the interviews regarding the formulation of the project-specific relational contracting model were then re-read, and a process analysis was performed for each project to perform a more detailed sequential analysis of the routine. One example of a sequential analysis for a project was as follows:

In a car ride home from a conference, a program manager and the procurement officer discuss the possibility of procuring using a new type of relational contracting and delivery model.

Discussions occurred between the procurement officer and a contractor firm representative during the market dialogue, which supports the initial idea. The contractor describes his experiences in the UK with ECI models.

The program manager talks informally with the purchasing department and the Major Projects department to anchor the idea of using relational contracting.

Formal suggestions from the project manager and the procurement officer are made to the purchasing board suggesting that certain projects are suitable for an ECI model. The decision is approved, and work continues in developing a project-specific procurement model.

The program manager and the procurement officer visit a known ECI project in the region.

A group of project members is established to formulate and develop project-specific contract documents.

Discussions and negotiations on adjusting the ECI framework to the specific project to match the “pure client” policy, as well as the experiences and intentions of the project management group are held.

The procurement officer speaks with a legal advisor in another city to legitimise the project decisions.

A decision on procurement announcement is made by the procurement board.

Participants’ actions were further examined based on sequences of routine action like the above.

Phase 3: Identifying the relationship between consistency and flexibility in the routine by addressing agency and structures in context

The continuous coding process in NVivo identified the dual nature of the ostensive pattering pre-procurement routine, illustrating how the routine balanced the tension between the need for project-level flexibility and the purchasing department’s need for stability and centralisation (Salvato and Rerup Citation2018, Bygballe et al. Citation2021). In this stage, code aggregation and refinement were informed by theories on organisational routines to unpack the dynamics of the double ostensive aspect of the pre-procurement routine. This moved the analysis to more of an abductive (Gioia et al. Citation2013) or a systematic combining approach (Dubois and Gadde Citation2002b).

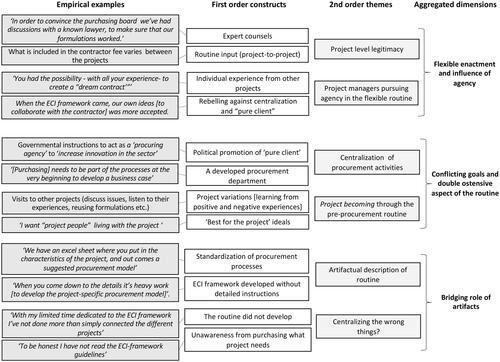

The conceptualisation of the second-order and aggregated dimensions were consequently guided by theories on routine dynamics. The analysis identified ostensive (pattering) and performative aspects of the routine’s enactment. The project-based context also supported an analysis of the role of agency and artefacts in routine enactment answering the recent call of Bygballe et al. (Citation2021). This analysis resulted in 29 primary constructs, which were narrowed down to 12 first-order constructs, 6 second-order themes, and 3 aggregated dimensions highlighting the double ostensive patterns, the role of agency and the flexible enactment of the routine, and finally the bridging role of artefacts in the case. See for the full coding structure.

Figure 2. Analytical categorisation and coding structure.

The following section will provide the findings of the case study.

Findings

For the reader to gain a necessary understanding of the routine under study, the findings section will commence with a generic description of the pre-procurement routine and the formal routine descriptions developed by the purchasing department. Furthermore, pre-procurement routine, in this case, is described by illustrating the conflicting ostensive aspects of centralising procurement activities or decentralising and increasing the flexibility of procurement decisions to the project-level, and how this internal dynamic influenced routine enactments and output.

Generative description of the Pre-Procurement routine

As a government agency, the STA follows the law on public procurement. Therefore, after the tender announcement, there are limited possibilities to change the procurement design. A considerable amount of work is done before procurement, and several important decisions are made regarding the type of contract, the reward system, and the award criteria. The organisational pre-procurement routine studied here comprises the actions taken to make these decisions and formalise the contract documents. The routine is performed at the project level, and the most central actors in the routine are the program manager, the project manager, the assistant project managers, and the project procurement officer. The routine also includes members of the central organisation who make certain formal decisions.

The purchasing department’s formal description of the pre-procurement routine (TDOK Citation2016:0233) is based on a categorisation of projects based on certain criteria, namely, complexity, uncertainty, and degrees of freedom. Depending on the project type, the formal routine recommends a contract scheme (design-build, design-bid-build, or consultancy contract) and reward systems. It suggests procuring complex projects within an Early Contractor Involvement (ECI) framework (TDOK Citation2016:0199). However, the project manager and the procurement officer are responsible for deciding, motivating, and producing these project-specific procurement models. Generally, the enacted pre-procurement routine may be summarised in the following four steps:

First, the type of project and the need for relational contracting should be evaluated based on complexity, uncertainty, and degree of freedom (according to the routine description).

The next step includes reaching out to contractor organisations and other similar projects within and outside of the organisation to capture both positive and negative experiences. This guides the project’s own decisions, so that positive results are maintained, while aspects that negatively impact relationships are altered in the project-specific procurement model. Discussions are held in the project management group and the formal ECI framework is adjusted and developed for the specific project.

In addition, the project’s own contract scheme, award criteria, and reward systems are defined and formalised in contract documents using legal expertise to ensure that procurement will be valid.

As decisions need to be confirmed by the purchasing board, the project management writes a report and attends a meeting to argue for the choices they have made and adjusts the formulations to match the routine description or ECI framework. During this period informal discussions with the purchasing department are common to anchor the choices and make sure they will be accepted.

The study shows that, in practice, these steps were overlapping, and all enactments varied to some extent. The following section will give a more detailed account of how the pre-procurement routine balanced the conflicting routine goals of the STA and how the flexibility in routine enactment allowed for variation in routine output (the project-specific procurement model). How the routine influences the development of relational contracting in the sector is covered in the Discussion.

Centralisation of procurement activities vs. Project level “Know-How”

With the creation of the STA, the purchasing department has gained a prominent role in the organisation. In an internal presentation from 2014 on the role of the “pure client”, the former head of the purchasing department stated that the STA was on a ”journey from ’in-house’ activity to becoming a client”. The same presentation presented a planned trajectory from 2010 to 2016, where procurement activities were to move from decentralised to centralised. In effect, decisions that were previously made at the project level were centralised and routinised in procurement strategies and policies developed by the purchasing department. As the officer at the purchasing department responsible for the ECI model said:

The procurement officers should be the ones that run the procurement. The project managers, well…they do a procurement once every 5–6 years, perhaps. Procurement officers do it more often, so obviously the purchasing department needs to be guiding these decisions. (P&LA)

Another goal in the STA was to become an “attractive client”, and the development of central procurement strategies was intended to increase the possibility of attracting contractors and increase the quality of the bids: In the purchasing department, we understand the “business” in contracting, and contractors value that. (P&LB)

Project members, on the other hand, were not of the same view, as illustrated by the following statement made by the former head of the Major Projects department:

The staff in the purchasing department have not run large billion-sized projects. You need to have done it yourself to understand when a design-build or a design-bid-build contract would fit your project. (MPA)

At an internal workshop on procurement strategy in January 2019 with staff from the project departments, there was a debate regarding the usefulness of using static schemata for procurement decisions in presentations about procurement strategy and routine. After the presentation, there was a workshop on how to apply the strategy on number of case projects. One of the members said: Well, I would have liked to apply a design-bid-build to this because then we could have controlled the activities more, but I know we should not do that. During the same workshop, participants expressed concerns about the competence of purchasing staff, as many of them were mainly specialists in public procurement and did not have experience in procuring construction contracts.

Regarding some issues, the project level indicated that the permanent organisation did not provide the support it could have when performing the pre-procurement routine. For example, the ECI framework stipulated a minimum of 8% and a maximum of 12% for the contractor’s fee. However, what was actually included in the contractor’s fee could be adapted in detail at the project level. The project managers used the contractor’s fee as a tool to shape the project-specific model according to their intentions. For example, in ECI 6, the project manager wanted to stay close to the standard contract so that the market would feel safe: We have stayed as close to the standard contract as possible and used its text for what is included in the fee (ECI6A). In ECI 4, the assistant project manager had some personal concerns regarding the contractor billing extra for transportation and accommodation to increase profit: We included transportation and accommodation in our fee. In effect, what is included in the fee is essential (ECI4C). However, even though the projects included different things in the fee, many of the project-level staff thought it would be beneficial if the fee was standardised within the organisation.

What is included in the contractor fee varies within the STA and I think that’s not good at all; it should be the same conditions, what is included in the fee. It must be similar, right now we do it differently(…) and we create a situation where our own procurements become competitors, and that is something we would like to avoid. (ECI4A)

When asked if the project needed more support when developing project-specific ECI models, the assistant project manager in ECI4 replied: Yes and no. I think we would have protested if there was too much control as well. Therefore, balance is important, and finding a good level for the most important issues. The lack of overarching guiding structures in the purchasing department was noticeable at the project level. For example, the procurement officer in ECI 7 described how other projects turned to her instead of the purchasing department when developing project-specific procurement models:

Today, many of my colleagues ask: “Do you have the presentation material?” or “How did you do this?” or “What were you thinking?” and so on. Because there is really no guidance…I think it would be good if the purchasing department could develop something, some examples, because [ECI contracts] are still so rare (ECI7C).

Sharing experiences between projects was generally based on individual initiatives and was not structurally supported by the purchasing department, which limited the range of projects available to contact.

Regarding learning between projects, we often have blinders on and we do not know what is happening in other parts of the country. You want someone from the purchasing department who can point out: “Here is a similar project”—that”s when we need their help. We, who work on the project do not have the time to do the research. (ECI4A)

However, even though reaching out to other similar projects to gather experience, this was part of the pre-procurement routine enactment in all projects. It served both as input to specific formulations and award criteria, etc., but it was also a type of legitimising activity.

The pre-procurement routine in practice: pursuing project level autonomy and gaining legitimacy

When analysing the empirical material, it became clear that the option to apply the ECI framework was appreciated by the project members because it allowed for a more flexible project-specific procurement model than traditional design-build contracts.

The previous Road Administration started to define a central procurement model for design-build contracts. These models are the same today, yet refined; our lawyers have made them really strict, and you need to follow them as a project manager. Therefore, I started to think: How can we do this here? And I came to think about relational contracting and having the contractor with us from the beginning. (ECI3A)

By many at the project level, the ECI framework was perceived as a step away from the “pure client” model and made it possible for project managers to pursue their own goals to a greater degree than before. One of the assistant project managers said: Well, for me, relational contracting and “pure client” are opposites. I know others think differently, but I’m convinced (ECI1C). When asked about the role of the “pure client” policy, a procurement officer replied: We don’t like that concept. We are not supposed to steer the contractor—absolutely—but we can be active and come with critical questions and ask for explanations. We do not refer to “pure client”; this is a design-build contract (ECI5C).

The project management teams had the authority to adapt the relational contracting framework for their projects if the formal requirements of the STA were met. One of the project managers argued:

Here [applying the ECI framework], you had the opportunity with all your experience to create a “dream contract” (…) I put together a working group and we discussed for months the best incentives for a relational contract. [The strategist responsible for the ECI framework] was included in our discussions to relate our ideas to the ECI framework. There, we could also figure out how much flexibility there was to the framework and in the end, he was very adaptive to our ideas (ECI5A)

For several of the project managers, the choice to adopt the ECI framework was based on a personal conviction (rather than on the formal characterisation based on the criteria in the routine description). For example, an assistant project manager explained the interest of applying an ECI contract. It’s all about past experiences. I come from collaborative projects; it is nothing more than that (ECI4C). The project manager in the same project added: I was so happy when I realised that we could apply a relational contracting framework to this project, it would not have worked otherwise (ECI4A).

When enacting the routine, the project management group developed a common view of the project, how it should be procured, described, and delivered, i.e. a process of “project becoming”, shaping the project identity. In this process, it was essential for project members to reach out to similar projects and gather experiences. During the first projects (ECI 1 and ECI 2), experiences were gathered from active projects outside the STA. In the later projects (ECI 3–ECI 7), previous ECI projects also served as a source of information.

It was about the same time as they were doing the procurement for ECI 1 and 2, so my procurement officer had some contact with the procurement officer there. We looked at them and how they did it. However, with the soft criteria we decided ourselves based on what we thought was important. (ECI6A)

The main purpose of sharing experiences was to allow project members to spot practices that worked, or did not work, in order to assist them in their decisions. Yet, these activities also served a unifying role, for example when a whole project management group jointly visited other projects. Projects addressed issues differently, and the input of other projects often reinforced the existing ideas of the project management team, creating a specific project identity. The following dialogue between the assistant project manager and the project manager in ECI 4 illustrates this phenomenon:

ECI4C: You notice when someone visits us or we visit another project that you learn a lot—both in terms of seeing how we want to do things and also how we don’t want to do things…

ECI4A: Mostly how we don’t want to do things [laughs].

ECI4C: [laughs] Yes, but then at least you feel like you have done something right in your own project.

Formulating the project-specific procurement model was described as very time consuming and a lot of details were up to the projects to decide. The process required the development of several formal sections of the procurement documents; i.e. the award criteria, the establishment of a reward system with incentives and bonuses. In addition, choices that were not formalised in the ECI framework developed by the purchasing department—such as what was included in the contractor fee, the contractual arrangements to connect Stages 1 and 2, and whether or not the budget should be communicated—were all up to the project manager to decide. It was a heavy job, we did it all by ourselves. (…) It is easy on a conceptual level, but when you start with the details, it is a massive amount of work (ECI12B). Nonetheless, this process was described as important by many participants since it was a form of preparation. The procurement manager in ECI 5 reflected on the substantial work required to finalise the project-specific procurement model: You get a real focus when you put 90% of your time on this [specifying the procurement model]. I think that focus is a precondition in this type of project (ECI5C).

Despite the large variations between the seven project-specific procurement models (see the table in Appendix 1 for a comparison), decisions had to be authorised by the permanent organisation in order for the project to go forward. This was done by communicating the decisions to the purchasing department, who ensured that the formulations were in line with the formal routine descriptions and the ECI framework, as described below for ECI 6:

We formulated quite early what we wanted, but to take things through the final decision to announce the tender, someone in the purchasing department told me: ”Well, I think it is good if you anchor this with [the Strategist responsible for the ECI framework]”. Well, we had some discussions and made some alterations. For example, the formulation of the award criteria that I wanted to use was adjusted [to the ECI framework]. We changed some words; for example, “collaboration” became “cooperation” and “work environment” became “safety”, so we had to adjust some things. (ECI6A)

Authorisation and “checkpoints” were not commonly perceived as an issue if the project or program manager was experienced and well-established within the organisation. As one procurement officer (ECI5C) said: When the top management level sees or appoints such an experienced project manager…well, things get easier. The extent to which the ECI framework could be adapted after the project members’ intentions was not explicit. Rather, the projects adapted their ideas and suggestions to certain formulations in the routine description to make sure the project-specific procurement model was accepted by the procurement board. The authorisation was a critical part of the pre-procurement routine, and the project managers knew they had to appear well prepared and be able to justify that their choices were made with good reason.

We had an external reference group and we had to make sure at every step of the decision scheme for the STA’s purchasing board and general board, that we had investigated, thought about it, and believed in it [the project-specific procurement model]. (ECI12B)

In summary, this case illustrates routine enactment at the project level and how the enactment was aimed both at designing the best conditions for the project according to the project members, and at fulfilling organisational requirements to legitimise the design and decisions. The following section will discuss these findings based on the three aggregated themes: double ostensive patterns, the bridging role of artefacts, and the performative aspects and impact of agency.

Discussion

As illustrated in the findings section, the performance of the routine was influenced by routine outputs and experiences in previous projects, but was also based on the actors’ own intentions (primarily those of the project managers) (Bresnen et al. Citation2005b, Howard-Grenville Citation2005). The routine enactment was flexible, and this flexibility was sanctioned in the description of the routine. If project managers could justify their choices, the permanent organisation authorised their decisions within certain explicit or implicit boundaries (for example, by using certain formulations).

Flexible enactment and the influence of agency

Previous literature on organisational routines shows that the more embedded a routine is within other structures, the more an individual must hold authority in the context to pursue agency and enact a routine flexible (Howard-Grenville Citation2005). In the case of STA, relational contracting was new in the context, increasing the possibility of actors to influence the routine’s enactment and output. The novelty and the weak attachment to other procurement routines increased the routine participants’ level of flexibility and allowed them to pursue their own intentions and challenge the “pure client” policy. Therefore, the findings of this study are consistent with previous studies showing that project managers align their existing organisational routines with new management innovations (Bresnen et al. Citation2004, Söderlund et al. Citation2008).

Routine flexibility was heavily dependent on the ability of routine participants to pursue agency (Feldman and Pentland Citation2003) as they actively created autonomy for the individual project during the formulation of the procurement model (cf. Willems et al. Citation2020). However, this ability was largely dependent on the legitimacy of routine participants in the organisation. Not unlike many other engineering contexts (Johansson Citation2012, Rennstam and Kärreman Citation2019), the legitimacy was based on the level of experience (Danner-Schröder and Geiger Citation2016). Individuals enacting the routine in the seven projects under study were highly-experienced project managers and procurement officers. The way project decisions were legitimised by the central organisation was based on traditional trust in experienced project managers due to institutionalised roles and predictable behaviours (cf. Kadefors Citation1995).

Conflicting goals and dual ostensive aspects of the Pre-Procurement routine

Both Turner and Rindova (Citation2012) and Rerup and Feldman (Citation2011) explain multiple ostensive aspects (or patterns) and their influence on routine enactment by showing, for example, how routine participants observe the requirements of consistency while also enacting the routine in flexible ways. However, these multiple ostensive aspects have not been the main focus in studies of organisational routines in project-based settings (see, for example, Davies et al. Citation2018).

The dual ostensive aspects (in centralising procurement models to the “pure client” policy, and adapting procurement models to project needs) had an impact on pre-procurement routine enactment. As such, routine enactment balanced multiple goals (Salvato and Rerup Citation2018). In the case presented by Salvato and Rerup (Citation2018), the goal conflict generated a constructive balance between artistic values and production costs of new products, which was beneficial for the organisation’s overarching goals of being competitive in the market. In this case, the balance within the STA could be described as a balance of power between centralisation by the central purchasing department, in accordance with political instructions, and the will of the project level to decentralise certain decisions.

However, it would have been beneficial—both to project members, and to enhance future predictability for contractors—if the purchasing department had standardised some of the parameters in the procurement model (for example, what was included in the contractor’s fee) but allowed other issues (such as being an active client) to be decided at the project level. Thus, the internal balance did not adhere to the needs of standardisation and support at the project level, nor did it support the long-term goals of being an attractive infrastructure client. Rather, the purchasing department was, to a large extent, driven to adhere to political calls for centralisation of procurement activities and strategy (cf. Witzell Citation2019). The flexible enactment of the routine allowed both the purchasing department and the project levels to feel that their objectives were met. In this balance, the descriptions of the ECI framework, the procurement strategy, and the described pre-procurement routine had a bridging role.

Bridging role of artifacts

The project level needed to make their actions seem in line with the artifactual descriptions of the routine and the ECI framework, formalised by the purchasing department. Therefore, the conflict of goals between the two organisational levels was not explicit, but the projects tried to manage this tension by adapting certain aspects, such as terminology, to the pre-procurement routine description.

Despite the variations in actors’ intentions and routine output, it was clear that in order to fulfil the ostensive pattern at the project level, the routine required reaching out to other similar projects to learn from their mistakes and successes, although this was not articulated by the purchasing department in the artifactual description. This “non-articulation” is similar to the findings of Davies et al. (Citation2018), who note that artefacts play a bridging role between the strategic and operational levels, where routines were left rather “open” for the operational department to experiment with in order to find what actions were actually useful at the operational level. However, in this case, routine development moved back and forth between departments. In order to standardise the routine for wider use in the organisation, the strategic department continued to develop routines based on the initial experiences at operational level. This was something the purchasing department of the STA did not do, although it could have been helpful. For example, recreating a project-specific procurement model for each project was very time consuming, and resistance at the project level to centralisation was generally related to the “pure client” policy specifically, as they did not oppose standardised measures per se. This frames a paradox as to what should be standardised in the internal routine descriptions and by whom. It seems that in the case under study, there was a mismatch between the need for support at the project level in standardising some features of the ECI framework and the role taken by the purchasing department (similar to the findings of Plantinga et al. Citation2020).

Implications for relational contracting in the construction sector

Institutionalisation of relational contracting is a complex matter. Bygballe and Swärd (Citation2019) argue that the inability to establish new routines in projects is one reason why the forms and results of relational contracting vary. This study adds to these findings and shows that even though an organisational routine in the client organisation is consistent, the flexibility in routine enactment creates variation in output (Howard-Grenville 2005). A notable example in this study was the contractor’s fee, as what was included in the fee could be adjusted at the project level, making it difficult to compare experiences between projects.

The variation in routine output creates a variety of inputs for later interorganizational projects applying (supposedly) the same contracting framework from the same client organisation. Arguably, this would hamper the predictability of the public client and thus counteracting the general long-term goal of public clients to be predictable (Kuitert et al. Citation2019), and in this case, the specific goal of the STA to be an “attractive client”.

Consequently, the establishment of centralised routines is in itself not enough for relational contracting to develop into shared practices, indicating its limited ability to drive change only through formalised decisions in a client organisation (cf. Lindblad and Karrbom Gustavsson Citation2020).

Some limited converging structures were observed; i.e. the application of ideas, formulation, and experiences from other projects. However, to legitimise project-specific choices, it was common to refer to negative experiences in previous projects when trying something new. As such, the sharing of experience generally diverged from project-specific models. The transfer of knowledge between ECI projects was based on individual initiative and was not structurally supported by the purchasing department. This supports existing findings in the construction and project management literature (cf. Hartmann and Dorée Citation2015), as well as the routine literature (cf. Cohendet and Llerena Citation2003), that in that learning is a social activity that happens mainly through networks and informal learning structures.

Conclusions

The main findings of the study contribute to research on the development of relational contracting practices in the infrastructure sector and research on organisational routines in project-based settings. First, the study show how variations of relational contracting models may be traced back to enactment of the pre-procurement routine in the client organisation and its role in balancing the goals of the purchasing departments’ procurements strategies and polices and project-level goals. Second, the study contributes to the discussion on organisational routines in project settings. As such, the study adheres to the call by Bygballe et al. (Citation2021) by showing how organisational routines in project-based organisations may balance flexibility and centralisation and the influence this has on stability and change; in this case, the diversification of relational contracting models. Flexible routine enactment resulted in variations in the routine output, i.e. project-specific procurement models.

Although the views of the purchasing department were reflected in the artifactual descriptions of the routine and guided decisions at the project level, there were still many details that were not standardised. In line with suggestions from Davies et al. (Citation2018), future studies on relational contracting could benefit from addressing what is standardised by the central departments and described in the internal procurement routines and how this is developed over time and anchored at project level (Bresnen et al. Citation2005b).

The routine did encompass learning activities, although they often contributed to increased variation of the relational contracting models instead of resulting in convergence. Future studies would do well to investigate learning architectures (Grabher Citation2004) in the infrastructure sector and what role routines play in the interactions between projects, institutional processes, and central departments in the organisations—on both the contractor and client side.

The study has practical implications for public construction clients, as it provides insights on the internal dynamics of public client organisations and the important role organisational routines play in managing internal goal conflicts. Better alignment between project and purchasing departments—with continuous improvement of routine descriptions and standardizations over time—could decrease variation between project-specific procurement models, and thereby increase the prospect of public clients to successfully change contracting practices in the construction sector.

Acknowledgments

The author is grateful to the guest editors and the two anonymous reviewers for their insightful comments. Furthermore, the author thanks Ingrid Svensson, Susanna Hedborg Bengtson, and Anna Kadefors for valuable feedback on previous versions of the paper.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Addyman, S., Pryke, S., and Davies, A., 2020. Re-creating organizational routines to transition through the project life cycle: a case study of the reconstruction of London’s Bank underground station. Project management journal, 51, 522–537.

- Annosi, M.C., et al., 2020. Learning in an agile setting: a multilevel research study on the evolution of organizational routines. Journal of business research, 110, 554–566.

- Bonham, M.B., 2013. Leading by example: new professionalism and the government client. Building research & information, 41, 77–94.

- Brady, T. and Davies, A., 2004. Building project capabilities: from exploratory to exploitative learning. Organization studies, 25, 1601–1621.

- Brunet, M., Fachin, F. and Langley, A., 2021. Studying projects processually. International journal of project management, 39, 834–848.

- Bresnen, M., Goussevskaia, A. and Swan, J., 2004. Embedding new management knowledge in project-based organizations. Organization studies, 25, 1535–1555.

- Bresnen, M., Goussevskaia, A. and Swan, J., 2005a. Implementing change in construction project organizations: exploring the interplay between structure and agency. Building research & information, 33, 547–560.

- Bresnen, M., Goussevskaia, A. and Swan, J., 2005b. Organizational routines, situated learning and processes of change in project-based organizations. Project management journal, 36, 27–41.

- Bresnen, M. and Marshall, N., 2010. Projects and partnerships: institutional processes and emergent practices. In: P.W.G. Morris, J.K. Pinto & J. Söderlund eds. The Oxford handbook of project management. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Brunsson, N., 2007. The consequences of decision-making. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Bygballe, L.E., Jahre, M. and Swärd, A., 2010. Partnering relationships in construction: a literature review. Journal of purchasing and supply management, 16, 239–253.

- Bygballe, L.E. and Swärd, A., 2019. Collaborative project delivery models and the role of routines in institutionalizing partnering. Project management journal, 50, 161–176.

- Bygballe, L.E., Swärd, A. and Vaagaasar, A.L., 2021. A routine dynamics lens on the stability-change dilemma in project-based organizations. Project management journal, 52, 278–286.

- Bygballe, L. E., Swärd, A. R. and Vaagaasar, A. L., 2020. Temporal shaping of routine patterning. In: J. Reinecke, R. Suddaby, A. Langley & H. Tsoukas eds. Time, temporality, and history in process organization studies. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Cacciatori, E. and Prencipe, A., 2021. Project-based temporary organizing and routine dynamics. In M. Feldman, B. Pentland, L. D’adderio, K. Dittrich, C. Rerup & D. Seidl eds. Cambridge handbook of routines dynamics. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Cohendet, P. and Llerena, P., 2003. Routines and incentives: the role of communities in the firm. Industrial and corporate change, 12, 271–297.

- D’adderio, L., 2011. Artifacts at the centre of routines: performing the material turn in routines theory. Journal of institutional economics, 7, 197–230.

- Danner-Schröder, A. and Geiger, D., 2016. Unravelling the motor of patterning work: toward an understanding of the microlevel dynamics of standardization and flexibility. Organization science, 27, 633–658.

- Davies, A., et al., 2018. The long and winding road: routine creation and replication in multi-site organizations. Research policy, 47, 1403–1417.

- Davies, A., Macaulay, S.C. and Brady, T., 2019. Delivery model innovation: insights from infrastructure projects. Project management journal, 50, 119–127.

- Dubois, A. and Gadde, L.-E., 2002a. The construction industry as a loosely coupled system: implications for productivity and innovation. Construction management and economics, 20, 621–631.

- Dubois, A. and Gadde, L.-E., 2002b. Systematic combining: an abductive approach to case research. Journal of business research, 55, 553–560.

- Eadie, R. and Graham, M., 2014. Analysing the advantages of early contractor involvement. International journal of procurement management, 7, 661–676.

- Emirbayer, M. and Mische, A., 1998. What is agency? American journal of sociology, 103, 962–1023.

- Eriksson, P.E., 2017. Procurement strategies for enhancing exploration and exploitation in construction projects. Journal of financial management of property and construction, 22, 211–230.

- Eriksson, T. and Kadefors, A., 2017. Organisational design and development in a large rail tunnel project—Influence of heuristics and mantras. International journal of project management, 35, 492–503.

- Feldman, M.S. and Pentland, B.T., 2003. Reconceptualizing organizational routines as a source of flexibility and change. Administrative science quarterly, 48, 94–118.

- Feldman, M.S., et al., 2016. Beyond routines as things: introduction to the special issue on routine dynamics. Organization science, 27, 505–513.

- Flyvbjerg, B., 2014. What you should know about megaprojects and why: an overview. Project management journal, 45, 6–19.

- Gadde, L.-E. and Dubois, A., 2010. Partnering in the construction industry – problems and opportunities. Journal of purchasing and supply management, 16, 254–263.

- Gehman, J., et al., 2018. Finding theory–method fit: a comparison of three qualitative approaches to theory building. Journal of management inquiry, 27, 284–300.

- Giddens, A., 1984. The constitution of society: outline of the theory of structuration. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Gioia, D.A., Corley, K.G. and Hamilton, A.L., 2013. Seeking qualitative rigor in inductive research: notes on the gioia methodology. Organizational research methods, 16, 15–31.

- Grabher, G., 2002. Cool projects, boring institutions: temporary collaboration in social context. Regional studies, 36, 205–214.

- Grabher, G., 2004. Temporary architectures of learning: knowledge governance in project ecologies. Organization studies, 25, 1491–1514.

- Hall, D.M. and Scott, W.R., 2019. Early stages in the institutionalization of integrated project delivery. Project management journal, 50, 128–143.

- Hartmann, A. and Dorée, A., 2015. Learning between projects: more than sending messages in bottles. International journal of project management, 33, 341–351.

- Hartmann, A., et al., 2014. Procuring complex performance: the transition process in public infrastructure. International journal of operations & production management, 34, 174–194.

- Hedborg, S., Eriksson, P.-E. and Gustavsson, T.K., 2020. Organisational routines in multi-project contexts: coordinating in an urban development project ecology. International journal of project management, 38, 394–404.

- Howard-Grenville, J.A., 2005. The persistence of flexible organizational routines: the role of agency and organizational context. Organization science, 16, 618–636.

- Johnson, D.P., 2008. Contemporary sociological theory. New York: Springer.

- Johansson, V., 2012. Negotiating bureaucrats. Public administration, 90, 1032–1046.

- Kadefors, A., 1995. Institutions in building projects: implications for flexibility and change. Scandinavian journal of management, 11, 395–408.

- Ketokivi, M. and Choi, T., 2014. Renaissance of case research as a scientific method. Journal of operations management, 32, 232–240.

- Kuitert, L., Volker, L. and Hermans, M.H., 2019. Taking on a wider view: public value interests of construction clients in a changing construction industry. Construction management and economics, 37, 1–21.

- Kulatunga, K., et al., 2011. Client’s championing characteristics that promote construction innovation. Construction innovation, 11, 380–398.

- Lahdenperä, P., 2012. Making sense of the multi-party contractual arrangements of project partnering, project alliancing and integrated project delivery. Construction management and economics, 30, 57–79.

- Langley, A., 1999. Strategies for theorizing from process data. The Academy of Management Review, 24, 691–710.

- Levitt, B. and March, J.G., 1988. Organizational learning. Annual review of sociology, 14, 319–338.

- Lindblad, H. and Karrbom Gustavsson, T., 2020. Public clients ability to drive industry change: the case of implementing BIM. Construction management and economics, 39, 1–15.

- Manley, K., 2006. The innovation competence of repeat public sector clients in the Australian construction industry. Construction management and economics, 24, 1295–1304.

- Manley, K. and Chen, L., 2016. The impact of client characteristics on the time and cost performance of collaborative infrastructure projects. Engineering, construction and architectural management, 23, 511–532.

- Martinsuo, M. and Huemann, M., 2021. Designing case study research. International journal of project management, 39, 417–421.

- Miles, M. B. and Huberman, M. A., 1994. Quallitative data analysis, 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks California: Sage Publications.

- Moretto, A., et al., 2020. Procurement organisation in project-based setting: a multiple case study of engineer-to-order companies. Production planning & control, 33, 847–862.

- Nam, C.H. and Tatum, C.B., 1997. Leaders and champions for construction innovation. Construction management and economics, 15, 259–270.

- Patrucco, A.S., et al., 2019. Which shape fits best? Designing the organizational form of local government procurement. Journal of purchasing and supply management, 25, 100504.

- Phua, F.T.T., 2006. When is construction partnering likely to happen? An empirical examination of the role of institutional norms. Construction management and economics, 24, 615–624.

- Plantinga, H., Voordijk, H. and Dorée, A., 2020. Moving beyond one-off procurement innovation; an ambidexterity perspective. Journal of public procurement, 20, 1–19.

- Rennstam, J. and Kärreman, D., 2019. Understanding control in communities of practice: constructive disobedience in a high-tech firm. Human relations, 73, 864–890.

- Rerup, C. and Feldman, M.S., 2011. Routines as a source of change in organizational schemata: the role of trial-and-error learning. The academy of management journal, 54, 577–610.

- Ruijter, H., et al., 2020. ‘Filling the mattress’: trust development in the governance of infrastructure megaprojects. International journal of project management, 39, 351–364.

- Salvato, C. and Rerup, C., 2018. Routine regulation: balancing conflicting goals in organizational routines. Administrative science quarterly, 63, 170–209.

- SOU 39., 2012. Vägar till förbättrad produktivitet och innovationsgrad i anläggningsbranschen. Stockholm: Produktivitets Komittens betänkande.

- Stake, R.E., 1995. The art of case study research. Thousand Oaks, Calif.: SAGE.

- Sydow, J. and Windeler, A., 2020. Temporary organizing and permanent contexts. Current sociology, 68, 480–498.

- Söderlund, J., Vaagaasar, A.L. and Andersen, E.S., 2008. Relating, reflecting and routinizing: developing project competence in cooperation with others. International journal of project management, 26, 517–526.

- Söderlund, J., 2015. Project based organizations. In: F. Chiocchio, E.K. Kelloway & B. Hobbs (eds.) The psychology and management of project teams. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Turner, S.F. and Rindova, V., 2012. A balancing act: How organizations pursue consistency in routine functioning in the face of ongoing change. Organization science, 23, 24–46.

- Trafikverket., 2010. Upphandlingspolicy, TDOK 2010:119.

- Trafikverket., 2016. Riktlinje Kontraktsmodell Samverkan Hög, TDOK 2016:0199.

- Trafikverket., 2016. Affärsstrategi för entreprenader och tekniska konsulter, TDOK 2016:0233.

- Volker, L. and Hoezen, M., 2017. Client learning across major infrastructure projects. In: K. Haugbølle & D. Boyd (eds.) Clients and users in construction: agency, governance and innovation. London: Routledge, 139–153.

- Walker, D. H. T. and Lloyd-Walker, B. M., 2015. Collaborative project procurement arrangements. Newtown Square, PA: Project Management Institute.

- Willems, T., et al., 2020. Practices of isolation: the shaping of project autonomy in innovation projects. International journal of project management, 38, 215–228.

- Winch, G.M. and Cha, J., 2020. Owner challenges on major projects: the case of UK government. International journal of project management, 38, 177–187.

- Witzell, J., 2019. Physical planning in an era of marketization: conflicting governance perspectives in the Swedish Transport Administration. European planning studies, 27, 1413–1431.