Abstract

With public and private clients in the construction industry increasingly using social procurement to achieve their social responsibility goals, it is important to develop theory-informed approaches for understanding how and to what extent social procurement creates social value. The research presented in this article uses social determinants of health (SDOH) theory to develop a case study of an employment-focused social procurement initiative in Australia’s construction industry. The case study shows how the employment-focused social procurement initiative used cross-sector intermediation to alleviate structural barriers to employment, including siloing in the employment services sector, unsupported pathways from training into employment in construction, and negative stereotypes of people who face structural barriers to employment. Using SDOH theory, the paper frames these barriers to employment as ‘upstream’ and ‘midstream’ structural determinants of health inequities. The research finds that the initiative’s impacts on determinants of health inequities are enabled and limited by commercial factors including project location and duration, status of the principal contractor, and insider knowledge of timing and requirements of new jobs.

Introduction

Governments and socially responsible businesses around the world are using social procurement as a way of leveraging the resources and relationships within construction supply chains to create social value (Barraket et al. Citation2016, Raiden et al. Citation2019, Loosemore et al. Citation2021). For example, in Australia, social procurement policies require the construction industry to create new training and employment opportunities for people who face systemic barriers to labour force participation (Loosemore et al. Citation2021, Citation2022). By providing new employment opportunities, social procurement aims to create social value by, for example, reducing long-term unemployment, improving gender equity, promoting Indigenous peoples’ economic empowerment, as well as the social and economic participation of people such as refugees and migrants (Barraket et al. Citation2016). Quality employment has the potential to improve standards of living, which can in-turn positively affect the health and well-being of individuals, households and communities (Vancea and Utzet Citation2017, Utzet et al. Citation2020, Irvine and Rose Citation2022).

Despite a policy narrative around creating social value, the outcomes of social procurement and the process by which outcomes are produced are not well understood (Barraket et al. Citation2016, Denny-Smith et al. Citation2021). Popular methodologies for measuring the social impact of social procurement initiatives such as social return on investment (SROI) are widely critiqued on methodological grounds and for their complexity, subjectivity and reductive focus on economic value (Arvidson et al. Citation2013, Denny-Smith et al. Citation2021). Other approaches are limited by their deterministic focus on easily quantifiable social ‘outputs’ such as the number of people employed (Raiden et al Citation2019). To progress, the field of social procurement in construction requires more theoretically robust frameworks that connect social procurement process with outcomes (Barraket et al. Citation2016, Raiden et al. Citation2019, Troje Citation2020).

The research presented in this article shows how a Social Determinants of Health (SDOH) framework can be applied to employment-focused social procurement initiatives in the construction industry to understand its impacts on health inequity – which is defined as the avoidable and unfair inequalities or disparities in health between groups of people (WHO Citation2023). SDOH literature emphasises that to address unfair disparities in health, interventions need to go beyond improving access to quality and affordable healthcare, to also address structural and community-based factors that affect living conditions, which in turn affect health (WHO Citation2023). Our research thus draws on SDOH literature to examine how employment-focused social procurement addresses the social structures and community conditions (particularly the structures and conditions that impact access to employment) that impact individuals’ lives (McKinlay Citation1979, Solar and Irwin Citation2010, Kelley Citation2020).

The overarching research question is thus: How and to what extent do employment-focused social procurement initiatives impact determinants of health inequities? To answer this overarching question, this empirical research addresses the following two sub-questions:

What barriers to employment do construction firms tackle via their employment-focused social procurement initiatives? To what extent?

What commercial factors shape the mechanisms through which construction firms involve different sectors in tackling determinants of health inequities?

The development of these research questions is discussed in detail below by drawing on SDOH theory and research to conceptualise the links between employment and health inequities at structural, community-based and individual levels of analysis (Wilkinson and Marmot Citation1998, Vancea and Utzet Citation2017, Burström and Tao Citation2020). The article then empirically investigates how an Australian construction firm’s social procurement initiative impacts structural and community-based barriers to employment, which are framed in this paper as determinants of health inequities. The initiative, called a Connectivity Centre©, aims to create job opportunities for people who face systemic barriers to employment. It is designed as a project-based intermediary that connects and coordinates local community service providers, third sector organisations, community organisations and businesses (i.e. employers) in the construction industry supply chain. Addressing the first research question, the empirical research shows how this initiative alleviates structural determinants of health inequity that arise from siloing in the employment services sector, unsupported employment pathways into construction, and negative stereotypes of people who face structural barriers to employment. Addressing the second research question, the research shows that the primary commercial factors that enable and/or limit construction firms in tackling health inequities include project location and duration, status of the principal contractor, and insider knowledge of timing and description of new jobs. These new insights contribute to a new discussion about the extent to which employment-focused social procurement in the construction industry is impacting the structural determinants of health inequity.

Social Determinants of Health Theory

SDOH theory presents a new and potentially valuable approach for studying how social procurement initiatives in the construction industry can affect health inequities in the communities in which it builds.

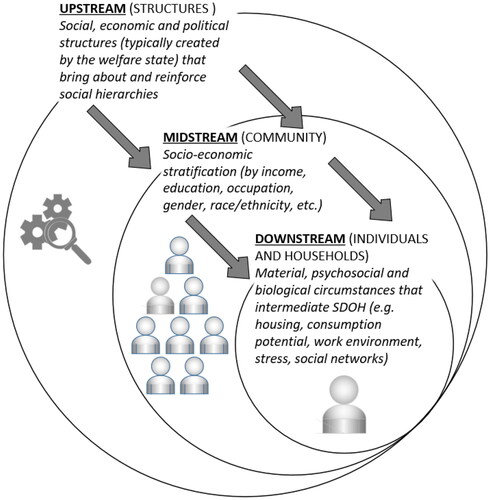

SDOH theory is based on an ecological model of health that frames people’s health as the product of the social and political conditions in which they live (Popay et al. Citation1998, Solar and Irwin Citation2010, Dahlgren and Whitehead Citation2021, WHO Citation2023). As illustrated in , SDOH theory conceptualises health as the result of three cascading levels of analysis—upstream social structures, socioeconomic status of communities or social groups midstream, and individual circumstances downstream. This approach sees an individual’s health as not just a product of their individual circumstances (downstream), but also as a product of the socioeconomic position of their communities midstream (determined by access to income, education, employment and occupation; Marmot Citation1997, Kelley Citation2020) and macro social, economic and political structures upstream (particularly the welfare state and its social and economic policies; Gusoff et al. Citation2023, Kelley Citation2020, Solar and Irwin Citation2010).

Figure 1. The causal chain of health inequities: upstream, midstream and downstream (informed by Dahlgren and Whitehead (Citation2021) and Solar and Irwin (Citation2010)).

The SDOH field emerged in the 1970s in response to evidence of the social stratification of community health—i.e. where chronic diseases and health conditions were found to be more prevalent among people and communities who faced systemic barriers to social and economic participation (Shaw et al. Citation2016). This put a focus on the relationships between midstream social determinants of health (i.e. a community’s socioeconomic position) and individuals’ circumstances and health downstream (Hancock 1986, Raphael et al. Citation2008).

Since the 1990s, SDOH scholars have given more attention to upstream determinants, or the ‘causes of the causes’ of health inequities (Marmot et al. Citation2008). This position was reinforced by a ‘Conceptual Framework for Action on SDOH’, which was developed by Solar and Irwin (Citation2010) for World Health Organization and remains the primary model of SDOH used internationally. Differentiating between midstream and upstream determinants of health, Solar and Irwin (Citation2010) argue that tackling health inequities involves ‘taking action’ on the upstream social mechanisms that systematically produce an inequitable distribution of the determinants of health among population groups.

Social procurement in construction and health inequities

As outlined above, in the construction industry, social procurement aims to create job and training opportunities for socioeconomic groups that face barriers to employment. Social groups targeted by social procurement include migrants in Sweden (Petersen and Kadefors Citation2016), First Nations peoples in Canada, South Africa and Australia (Denny-Smith and Loosemore Citation2017), as well as young people, people in long-term unemployment and women (Loosemore et al. Citation2020).

Research of the links between social procurement in construction and health inequities usually analyses the links between social procurement in construction and health downstream. For example, in Australia, Loosemore et al. (Citation2021) reported the impact of an innovative work-integrated program run within a global facilities management company and reported outcomes under five main areas: affective (impact on people’s attitudes, happiness, optimism, self-esteem, confidence, motivation to succeed and life satisfaction etc); health and well-being (impact on people’s physical and mental health and well-being); cognitive (impact on people’s knowledge, skills, qualifications, literacy and numeracy, communication skills, time management etc); behavioural (impact on punctuality, taking responsibility, teamwork, social interaction, anger, trust, respect and behaviour towards others etc); and situational (impact on an individual’s personal circumstances and life outside of work such as: increase in income, credit-rating, debt levels, access to transport, stable accommodation support networks etc). More recently, Bridgeman and Loosemore (Citation2023) used Sen and Nussbaum’s Capability Empowerment Approach, to analyse a Welsh construction industry training initiative for young people at risk of homelessness. The results show that the initiative helped reduce the risk of homelessness (which has direct benefits for people’s health and well-being) by increasing young peoples’ housing security via higher income, improving people’s social networks and positive social relationships, improving mental and physical health and increasing awareness of health and safety issues, and by improving numeracy and literacy and giving them the confidence to forward-plan their lives.

In relation to midstream SDOH (see ), SDOH scholars are currently emphasising that the quality of employment is a significant determinant of health (Wilkinson and Marmot Citation1998, Lingard and Turner Citation2017). Evidence links poor-quality employment (including long working hours, poor working conditions and high job stress, which are present in the construction industry) to poor physical and mental health outcomes for workers (Campbell and Gunning Citation2020, Crook and Tessler Citation2021). One study in New Zealand found that social procurement outcomes have the potential to reduce precarious employment in the construction industry for Māori and Pasifika workers by influencing change in employers and the construction industry as a whole. The study found that social procurement clauses can reduce precarity by improving the skills and capability of workers, while also increasing their pay rates (Hurt-Suwan and Mahler Citation2021).

Research that provides insight into how construction firms may address upstream SDOH (see ) via social procurement is also scarce. In the Swedish context, Troje and Kadefors (Citation2018) find that employment requirements in social procurement policies are enabling construction firms to recognise social value in addition to cost and quality of physical products, and that this speaks to a fundamental shift in logics (indicating structural change). This change is enabled by the creation of new roles (Employment Requirement Professionals) that focus on creating genuine employment opportunities in the construction industry. Yet in Australia, Reid and Loosemore (2017) have found that social procurement is compliance-driven and confined to low-value and low-risk activities—thus preventing change at a meaningful scale to the structures or mechanisms that create hierarchies in the industry.

While the above research analyses downstream, midstream and upstream factors that are relevant to SDOH, the authors do not explicitly discuss how their findings contribute to knowledge about social procurement in construction as a health equity intervention. Furthermore, they focus on downstream factors at an individual ‘beneficiary’ level. Situated in this gap, this article thus poses its first research question: What barriers to employment do construction firms tackle via their employment-focused social procurement initiatives? To what extent? Answering this question will not only address a gap in extant research but it will help practitioners better design initiatives to positively impact health equity outcomes. While the implementation and evaluation of downstream interventions are usually situated in a specific time and place, enabling the monitoring and attribution of outcomes, it is by addressing upstream and midstream SDOH factors that organisations tackle the entrenched causes (midstream) and causes of the causes (upstream) of health inequity (Kelley Citation2020). Due to challenges of time-lag, data availability and attribution, however, upstream interventions are more complex to implement and evaluate (Lee et al. Citation2018).

Commercial factors that enable and/or limit impacts on determinants of health inequities

In their conceptual framework for action on SDOH, Solar and Irwin (Citation2010) say that impacting the upstream and midstream causes of health inequities involves reworking power relations. To rework power relations, interventions need to: (i) promote collaboration across sectors; and, (ii) support the participation and empowerment of people adversely affected by health inequities. Current research of employment-focused social procurement in construction shows that while it aims to facilitate intersectoral collaboration and social participation and empowerment, there are numerous barriers to this occurring in practice (Loosemore et al. Citation2022).

Creating genuine employment opportunities through social procurement requires the involvement of suppliers (who provide employment to equity-seeking groups), as well as government and not-for-profit organisations (who provide access to training and services that support people in employment) (Lou et al. Citation2023, Natoli et al. Citation2023). Empirical studies find that the newness of cross-sector partnerships in the construction industry means there is often resistance to change from incumbent supply chain suppliers and subcontractors and inadequate knowledge, interest, or capacity across sectors to coordinate significant shifts in the employment opportunities for equity-seeking groups (Troje Citation2020, Loosemore et al. Citation2022). This results in surface-level ‘cooperation’ through ‘informal, temporary, unstable, low trust, voluntary and low commitment relationships which involve little sharing of resources, risk and reward’ (Barraket and Loosemore Citation2018). This links to a concern in the SDOH literature about the capacity of corporations to impact health inequities (McKee and Stuckler Citation2018, Rochford et al. Citation2019).

Empirical studies in SDOH find that corporations routinely use instrumental, structural and discursive power to reinforce socio-economic inequities that benefit the firm, even though these inequities have adverse effects on health (Wood et al. Citation2022). In these cases, there is little attempt to work collaboratively across sectors to create change, or to support the social participation and empowerment of people adversely affected by health inequities. Findings from this nascent field of research however, focuses almost entirely on the negative impacts of harmful industries such as tobacco, alcohol and ultra-processed food and drink (Hill and Friel Citation2020, Madden and McCambridge Citation2021, Mialon Citation2021), and are not easily transferred to the construction industry.

With a focus on how construction firms leverage power to design and implement employment-focused social procurement, the second research question thus asks: What commercial factors shape the mechanisms through which construction firms involve different sectors in tackling health inequities? This question contributes to insight into the factors that enable or limit construction firms to have positive impacts on determinants of health inequities and thus identifies opportunities for reworking the power relations that create inequitable barriers to employment for some groups. Understanding the mechanisms (from the perspective of diverse stakeholders) will help construction firms to identify how to leverage their unique position to impact health inequities, as well as the limitations to expect.

Research design

To understand the social impact of employment-focused social procurement in terms of health equity this article develops a case study of unique project-based intermediary called a Connectivity Centre©, developed by a major Australian contractor to meet its social procurement obligations on major projects. Unique or ‘atypical’ cases ‘often reveal more information [than other types of case studies] because they activate more actors and more mechanisms in the situations studied’ (Flyvbjerg 2001: 78). While all case study research has limitations of generalisability to the population (Flyvbjerg 2001, Yin Citation2017), they provide a strong basis for theory development by enabling insights into phenomena in greater depth than representative, or survey-type research. In-depth case study research is especially important in nascent fields such as social procurement which are in the early stages of theory development (Barraket et al. Citation2016, Troje Citation2020).

Case study description

The first Connectivity Centre© was developed in 2010 by a major Australian contractor to create employment pathways into the contractor’s supply chain on a project, for people who face barriers to employment in the construction industry. Based on lessons learnt, the centres have become a key part of the contractor’s strategy to meet various new social procurement obligations which are being imposed on the industry – especially by government clients. Connectivity Centres© engage suppliers, subcontractors, training organisations, providers of government services, charities and community organisations to create employment pathways. They physically co-locate these partner organisations in a building adjacent to a major construction project, and aim to facilitate cross-sector collaboration and coordination on a project-by-project basis for the purpose of improving job seekers’ access to workplace training, work experience, wraparound support services, and supportive work environments. Since the initial Connectivity Centre© in 2010, there have been fifteen centres on approximately $8 billion of major infrastructure and building sites across the states of New South Wales, South Australia and Victoria, Australia.

Data collection and analysis

To explore the extent to which Connectivity Centres© impact upstream and midstream determinants of health inequities, the case study was developed via online semi-structured interviews ranging between 30-60 minutes. Informed by the research questions and theoretical framework in , interviews were designed to gather insight into the upstream and midstream employment-related issues that Connectivity Centres© aim to address (Research Question 1), and the factors (particularly commercial factors) that enable and limit Connectivity Centres© from creating that change (Research Question 2).

The interviews were conducted with key representatives from the Connectivity Centre© and partner organisations (see ). Participants worked in or worked with between one and four Connectivity Centres in three states of Australia (including New South Wales, Victoria and South Australia). Participants were recruited with the assistance of the contractor who had created the Connectivity Centres©. After being provided with the names of key representatives by the contractor, the research team independently contacted and recruited participants following ethics protocols to ensure anonymity and minimise potential sponsor bias. Interviewing continued until the data collection process offered no new and relevant insights in relation to the research questions (Saunders et al. Citation2018). This resulted in a total of fifteen interviews as described in .

Table 1. Sample structure.

Data collection via semi-structured interviews gave respondents the freedom to express their views and experiences in their own terms outside of standardised analytic categories (Keene et al. Citation2016). This freedom was important because it allowed partner organisations, who were positioned in different sectors, to describe and reflect on their unique roles in the creation of employment pathways in the contractor’s supply chain. The semi-structured method allowed interviews to fulfil the purpose of conducting an ‘atypical case study’ of social procurement, which was to generate rich insights that inform theoretical propositions with analytic transferability (Flyvbjerg 2001).

All interviews were audio-recorded, transcribed verbatim and analysed using thematic analysis, guided by protocols set out by Guest et al. (Citation2012) and Gioia et al. (Citation2013). To analyse data, researchers first organised and coded data around a descriptive coding framework informed by the core constructs in the research questions (including upstream and midstream SDOH, changes to specified upstream and midstream SDOH, Connectivity Centres practice: cross-sector collaboration and involvement of participants, and the enabling and constraining commercial factors for doing so). Researchers then used an abductive approach to move back and forth between the interview data and core concepts in the research questions to identify the key elements and themes of the core constructs (see for examples). The effect of researcher positionality on analysis and interpretation of data was managed through reflexive conversations among the research team throughout the process of data analysis (Mauthner and Doucet Citation2003). The results of our analysis are presented below in a narration of empirical findings, supported with relevant quotes from the semi-structured interviews.

Table 2. Examples of the coding process.

Empirical findings

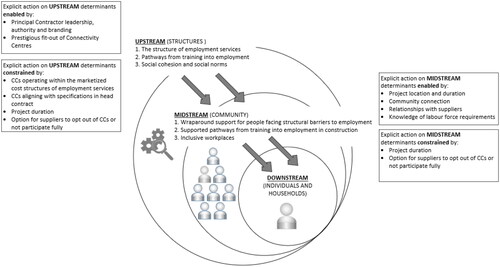

Our data shows how a construction firm’s Connectivity Centres© impacted structural barriers to employment, including by: Alleviating siloing in the employment services sector (Finding 1); Improving connections between employment services and employment opportunities (Finding 2); and Challenging discriminatory stereotypes that prevent employers from supporting priority job seekers (Finding 3). frames these structural barriers to employment (i.e. siloing of services, weak employment pathways, and negative stereotypes) as determinants of health inequity, and outlines how Connectivity Centres tackled these structural determinants of health inequities (Research Question 1), and the commercial factors that enabled and/or constrained this from happening via the involvement of different sectors and participants (Research Question 2).

Table 3. The commercial factors that enable and/or limit construction firms in tackling determinants of health inequities via the involvement of different sectors and participants.

Finding 1: Alleviating siloing in the employment services sector

All participants stated that Connectivity Centres© played an important role in alleviating the organisational siloes that are widely acknowledged to exist within the Australian employment services sector. From the perspective of the CEO of a training organisation that partnered with Connectivity Centres©,

Government funding generally causes a hell of a lot of siloing. It just happens. You have to take off your day-to-day goggles and go ‘ohh hang on a second, we can actually work together on this project and it will support us and will also support a longer-term approach.’ (Training Organisation)

For service providers who partnered with Connectivity Centres©, siloing had prevented them from knowing what government support services were available to meet the needs of people who faced structural barriers to employment. Some services were directly related to health support (including support around mental health, or drug and alcohol addiction) while others impacted daily living conditions such as housing security, interaction with the justice system, and transportation (examples of SDOH). Research participants said that by intermediating organisations in different silos, Connectivity Centres© helped service providers to understand and meet clients’ complex support needs in the context of employer requirements and job demands.

A commercial factor that enabled Connectivity Centres© to alleviate the structural siloing of the employment services sector was the construction firm’s powerful role as head contractor. This provided a high degree of formal legitimacy and control over economic assets and processes that empowered Connectivity Centres© to convene, co-locate, and sustain intersectoral work among participating organisations for the duration of multi-year construction projects.

A Connectivity Centre© Coordinator said that he mitigated siloing of services in local communities by fostering trust and building connections between a range of local service providers. Drawing interesting parallels to health services, he said partner organisations were:

…heavily involved with almost every single job seeker through training, mentoring… We had at least monthly or bimonthly meetings where these key stakeholders got together and talked through all the caseload. It was like case conferencing where the doctor, the nurse, all the relevant stakeholders who had a hand with that particular patient would do a quick round and talk everything through. (Connectivity Centre© Coordinator)

Providers of education, employment services and other services found that the multi-year timeframe and volume of activity in the contractor’s projects provided the time needed for trusting working relationships to develop between the organisations and their representatives co-located in the centres. One representative from a training organisation said that:

when you’ve got a project where there’s some bulk occurring, that’s where you can sit down and work a little closer with some of these other organisations that are specialists in whether it be mental health or housing or drug and alcohol, whatever. (Training Organisation)

unemployed people [at the Connectivity Centre©] come from a whole lot of different providers and the way the Connectivity Centre© is set up means there’s no way of recouping outlay. We got involved because we saw the bigger picture, the difference it could make for that community, the legacies that it could leave. (Employment services provider)

Despite this lack of formal connection with policymaking, government policymakers still indicated that Connectivity Centres© influenced their work, by informing their engagement with the private sector to create new opportunities for economic participation of underrepresented social groups. Policymakers participated intermittently in high-level Connectivity Centre© community consultation and strategy talks, and new centre launches and this gave them insights into how Connectivity Centres© leveraged the structural power and resources of the principal contractor to alleviate barriers to employment, including alleviating siloing of service providers. They felt that this positively affected the scope and depth of their relationships with a broad range of service providers and gave them new ideas for solutions which could inform their contribution to future policy design.

Finding 2: Improving connections between employment services and employment opportunities

A second upstream, structural determinant of health inequities that Connectivity Centres© alleviated was the absence of supported pathways from training or employment preparation programs into jobs in the construction industry. One research participant who was a policy maker in a federal government department said,

‘there is so much money that’s just funnelled into training opportunities without that vital connection to employment. Service providers try to get job seekers into training courses because this is how they tap into the money that’s available. The client then walks away with a Certificate III or part qualification but without that vital connection to employment, it’s really just an exercise in futility’. (Policymaker)

Confirming the lack of supported pathways into employment, one subcontractor said new employees in his plumbing business tended to be sourced from the social networks of existing employees.

Connectivity Centres© tackled this structural barrier by leveraging two key commercial factors: the primary contractor’s contractual relationship with employers (i.e. subcontractors); and detailed knowledge throughout the supply chain of labour demands and requirements on multi-year construction projects. Connectivity Centres© gathered and shared with training providers information about the nature of jobs that would become available, when they would become available, the skills and attributes required to perform well in those roles and what employers were looking for in a suitable candidate. Connectivity Centres© gained this information through dialogue with subcontractors which one subcontractor described as follows:

I'll often speak with [Connectivity Centre© staff] around, you know, ‘this project is coming up where we’ll be looking for a first- or third-year apprentice’. We’re looking for people that can work in a physical environment because we’re in the trade. So just giving them a general overview of what we do and the kind of people we’re looking for and going from there. (Subcontractor)

real project with real employment opportunities… we don’t have these kinds of opportunities all the time, where we know what’s needed and what to do to support job seekers to get into these real jobs. (Employment services provider)

[The principal contractor] guarded the relationship with the subcontractors fairly closely. I got the impression they didn’t want the subcontractors burnt by a million providers knocking on their door. (Employment services provider)

Relating to the problem of transience, one training organisation noted that the quality and potential impact of employment can be limited when linked to a specific project or site need. As a subcontractor said:

you don’t want to hire someone for 14 months and then leave and then they don’t have employment because we’re no longer in that physical area. (Subcontractor)

Therefore, while Connectivity Centres© had an important impact on job seekers’ entry into ‘real’ employment opportunities in ‘real’ projects, the transitory nature of major project work often prevented Connectivity Centres© from safeguarding the longevity of employment. This was felt most acutely on projects located in regional areas where subsequent employment on other projects was less common than in urban regions.

Finding 3: Challenging discriminatory stereotypes that prevent employers from supporting priority job seekers

The third upstream structural determinant of health that research participants said Connectivity Centres© addressed was the negative stereotypes employers in the construction industry held of people who face structural barriers to employment. The construction industry in Australia is known to have a highly masculine culture, with layering of formal and informal social connections leading to exclusionary employment practices that disadvantage women and other groups underrepresented in the construction industry. Legitimised by industry culture, subcontractors often consider disadvantaged job seekers as risks to be mitigated rather than opportunities to pursue.

Reflecting on subcontractor’s discriminatory attitudes, one Connectivity Centre© Coordinator stated that:

Occasionally a subcontractor would say to me, “Yeah, but we’re a certified trade, I can’t just have a disabled person wandering around”’. (Connectivity Centre© Coordinator)

The commercial determinants that enabled Connectivity Centres© to challenge negative stereotypes of disadvantaged job seekers were the contractor’s status as principal contractor, its contractual relationships with subcontractors, and the professional skills of Connectivity Centre© coordinators. One coordinator said that, to challenge negative stereotypes, she would:

turn the table quite suddenly and discuss ability and disability as a spectrum of human existence, how not all disabilities are visible, and how people do things differently. (Connectivity Centre© coordinator)

Not been done on the cheap, but rather, in a super honoured way, with the best audio visual, nice meeting rooms… everything felt so good. (Subcontractor)

you can’t underestimate the power of the principal contractor. If the principal contractor is demonstrating that they’re committed to this – that flows on. (Employment services provider)

Despite this signalling to subcontractors, a Connectivity Centre© Coordinator noted that some subcontractors would either choose to pay a fine rather than work with Connectivity Centres©, or not invest fully in supporting new employees. One subcontractor said that his business:

did not pander to them… so if they don’t want to work, they’re just given a meaningless job to do, and when they want to step up to the plate, then they progress and they get their skills and improve. (Subcontractor)

Nevertheless, among subcontractors who did engage with the centres, evidence indicated that the head contractor’s leadership enabled shifts towards more inclusive cultures and workplaces that promoted health outcomes. One research participant described his business’ interest in creating a more inclusive workplace. They stated that the head contractor’s leadership and practical support via the Connectivity Centre© enabled them to,

hire a brand-new starter with Indigenous background who wasn’t actively at school or in the workforce… at the time he was very quiet, nervous. You could tell the Connectivity Centre© had helped him. They were really helping him just put his best foot forward and be able to sit in a meeting. He’s now a young fellow that’s apprenticing a registered trade, so he’s been in our business for three years. He’s a part of our team. (Subcontractor)

The above perspectives show that the extent to which Connectivity Centres© were able to genuinely challenge discriminatory stereotypes towards people who face structural barriers to employment depended on subcontractors’ openness to change, as well as contractual obligations to comply.

Discussion of findings

Addressing the first research question about the extent to which construction firms tackle ‘upstream’ and ‘midstream’ barriers to employment via their employment-focused social procurement initiatives, the case study of Connectivity Centres© shows greatest concentration of activity at the midstream, community-based and/or project-based level. Connectivity Centres facilitated connections among service providers (Finding 1) and between service providers and employers (Finding 2) in project-based locations. While these connections worked towards strengthening the efficacy of wraparound support and employment pathways for people who face structural barriers to employment in those locations, they did not address upstream factors—including the competitive funding model created by the welfare state that is the fundamental cause of siloed services. The upstream determinants of health that Connectivity Centres addressed were discriminatory stereotypes, which are well known to cause stress in the workplace (including in construction) and impact on both psychological and physical health (Wilkinson and Marmot Citation1998, Dunn et al. Citation2011). While impacts on stigma appeared limited to situations where subcontractors were already open to attitudinal change, subcontractors nevertheless spoke about how shifts in attitudes within their organisations informed their practices on future projects.

Synthesising findings with a focus on the second research question, highlights the mechanisms that enabled and/or constrained Connectivity Centres’ impact on upstream (boxes on left) and midstream (boxes on right) determinants of health inequities via the involvement of different sectors. The concentric circles in the centre emphasise the cascading nature of the causes of employment-related health inequities.

Figure 2. Conceptual framework: How Connectivity Centres© impact upstream and midstream determinants of health, including key enablers and constraints.

The case study of Connectivity Centres© suggests that employment-focused social procurement that is project-based is better suited to impact midstream causes of health inequities (as opposed to upstream determinants or the ‘causes of the causes’ of health inequities; Gusoff et al. Citation2023, Kelley Citation2020, Solar and Irwin Citation2010). The corporate and commercial determinants of health literature, however, emphasises that how and the extent to which corporations exert power (and thus impact structural determinants of health) is increasingly unseen—for example, by defining the dominant narrative or setting the rules by which society, especially trade, operates (McKee and Stuckler Citation2018). The Connectivity Centre© case study showed that Connectivity Centre© leadership fostered long-term relationships with policymakers, included them intermittently in certain strategic discussions, and thus showcased Connectivity Centres© as effective strategies for working across sectors to address structural barriers to employment in localised settings. Employment-focused social procurement initiatives that are project-based may therefore have the potential to indirectly affect structural determinants of health upstream if policy makers adopt and scale them as policy solutions (Indig et al. Citation2018). For policymakers to do so, it is important that they (together with other construction firms or other industry bodies) identify which mechanisms to replicate, and which elements to adapt for different contexts.

In the case of Connectivity Centres©, the commercial mechanisms that enabled the employment-focused social procurement initiative to address health inequities stemmed from their role as a ‘regime-based intermediary’ (Kivimaa et al. Citation2019)—i.e. an intermediary that leverages insider status within a dominant system (i.e. the construction sector) to pursue structural change within that system. Connectivity Centres© aligned with and leveraged the major contractor’s insider status to ground and orientate their work on specific construction projects with specific labour force requirements; facilitate direct connections with and between the employment services system and employers (subcontractors); and to challenge negative stereotypes towards equity-seeking groups who are the focus of social procurement policies and strategies. Had the Connectivity Centre© not been an intermediary on the ‘inside’ of the construction industry and project (primarily due to its strong association with the major contractor), it is unlikely to have had the same opportunities to embed its work within the clear parameters of a construction project, nor been recognised by service providers and supply-chain actors as an influential and prestigious actor. Intermediaries that lack symbolic and practical legitimacy (Suchman Citation1995) are known to incur very high transaction costs, requiring staff to go ‘above and beyond’ their standard roles to mobilise actors in the system and thus address unmet needs in the community (Barraket et al. 2023). From a health equity perspective, the positioning and legitimacy of the intermediary relative to the sector that it aims to change is thus a critical factor to consider in the design of employment-focused social procurement initiatives.

Research participants also reflected on the limitations of the project-based model of Connectivity Centres©—particularly their cessation at the completion of the construction project. This marked the end of co-location and coordination of service providers as well as project-based employment opportunities for job-seekers. This limitation has been identified in prior studies on the risks of construction social procurement (Loosemore et al. Citation2022) as well as in the broader literature on intermediation (Klerkx and Leeuwis Citation2009). In considering how to mitigate this limitation, policymakers and the construction industry should consider that intermediation demands change over time (Barraket Citation2020), as 'fields’ such as local welfare systems or industry sectors come to accept or legitimise new practices (in this case, employment-focused social procurement) and develop the capability to practice them. To promote the longer-term health equity impacts of initiatives such as Connectivity Centres©, construction firms may work with actors that are embedded within local communities (for example, work integration social enterprises; Barraket et al. 2023) to coordinate constellations of public, private and community services organisations that can support and extend the connective work of project-based intermediaries, whilst also further building capacity in local welfare systems.

These findings align with and extend research on social procurement in the construction industry that emphasises the importance of cross-sector collaboration for creating social value, despite its challenges in commercial environments (Loosemore et al. Citation2020, Troje and Gluch Citation2020, Troje and Andersson Citation2021). The case study of Connectivity Centres© has highlighted that from a health equity perspective, it is important to examine social procurement initiatives that leverage cross-sector intermediation not only in terms of how they break down barriers to employment during the life of a project, but also in terms of how they influence policymakers’ perspectives on effective policy solutions to systemic causes of unemployment, and how they impact local welfare systems that endure beyond projects. Both are avenues through which construction firms could elevate their impacts on midstream determinants of health equity to the upstream ‘causes of the causes’ of health inequities.

Conclusion

With governments around the world increasingly using social procurement as a way of leveraging the resources and relationships within construction supply chains to create social value, it is important to develop theory-informed approaches for understanding the process and outcomes of social procurement. This article has addressed a gap in theory and evidence in the social procurement field, by framing employment-focused social procurement initiatives in the construction industry as having an impact on upstream and midstream determinants of health inequities. This was achieved through an in-depth case study of a unique project-based intermediary in Australia, established across multiple construction projects to implement clients’ employment-focused social procurement targets. Based on the assumption, stemming from Social Determinants of Health theory, that upstream structures, midstream stratification and downstream conditions are determinants of individual health, our research findings provide three important new conceptual and practical insights into how to theorise and critique the case study initiative’s impact on health inequities.

First, SDOH theory applied in this research offers a unique and fruitful approach to understanding and connecting the process and outcomes of social procurement in terms of health equity. Social determinants of health literature emphasises that to address disparities in health, interventions need to go beyond improving access to quality and affordable healthcare, to also address ‘upstream’ and ‘midstream’ factors that affect living conditions, which in-turn affect community health inequities and outcomes (WHO Citation2023). While social procurement may not link directly to improving healthcare, this paper shows how health impacts can be understood using an ecological model of health, such as SDOH.

Second, employment-focused social procurement intermediaries such as Connectivity Centres© are well positioned to impact midstream determinants of health inequities—including alleviating (not reforming) siloing in the employment services sector through new within-sector relationships and creating supported pathways for specific demographic groups from training into ‘real’ positions of employment. They can also impact upstream determinants by challenging negative stereotypes of disadvantaged job seekers. In essence, Connectivity Centres engage providers of employment services in the construction industry and vice versa, by leveraging commercial relationships with subcontractors to provide employment and training opportunities for people who face structural barriers to employment, and by orientating organisational collaboration on project-based activities. Furthermore, its influential position as an intermediary between three dominant systems (construction industry, employment services and social services) enabled it to put pressure on structural barriers that pose barriers to employment for certain groups in society.

Third, while Connectivity Centres© were explicitly focused on impacting midstream causes of health inequities, it is probable that there are other implicit processes and impacts at play that not all actors were strategically and intentionally engaged in (for example, via a fostering of long-term relationships with policymakers, which created openings for the head contractor to influence industry-specific employment-focused initiatives that were government-led). Understanding the unseen, implicit processes and impacts of employment-focused social procurement on health inequities is an area for researchers to explore in the future.

These new insights highlight how employment-focused social procurement initiatives in construction are impacting structural determinants of health inequities. The findings need to be interpreted within the Australian context in which the research was conducted. The top-down and targeted nature of social procurement policies in Australia is in contrast to the bottom-up and flexible nature of social procurement policies in countries like the UK. The structure of the employment eco-system in which such intermediaries need to function also differ from one country to the next. This is likely to have implications for the design of initiatives like the one we have studied here. However, this does not undermine the potential value of project-based intermediaries like the Connectivity Centre© in a wider international context. It merely means that the actors involved in such intermediaries and dynamics between them would be different and would require different management and research to understand what these differences might be. Furthermore, alleviating siloing in the employment services sector, improving connections between employment services and employment opportunities, challenging discriminatory stereotypes that prevent employers from supporting priority job seekers are challenges which have been identified in other countries, in supporting people into employment.

Further case study research is needed into the SDOH impacts of different types of initiatives in Australia and overseas to fully understand how the construction industry is impacting determinants of health inequities through social procurement. For example, because interview participants in our study did not speak at length about how they supported the involvement and participation of people who face structural barriers to employment in actively creating their own job opportunities, this remains an important question for further research. Future research should give particular attention to their experiences and views on what would support their participation. As identified in the Discussion (above), there is also an opportunity to understand the longer-term impacts of social procurement initiatives—both in terms of how they influence policymakers’ perspectives on effective policy solutions to systemic causes of unemployment, and how they impact local welfare systems that endure beyond projects. Both are avenues through which construction firms could elevate their impacts on midstream determinants of health equity to the upstream ‘causes of the causes’ of health inequities.

Acknowledgments and ethics

We are grateful to and acknowledge the assistance of Dave Higgon (Multiplex Construction Pty Ltd) and Joanne Osborne (DAMAJO) in undertaking this research and for commenting on drafts of this paper.

Disclosure statement

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Data availability statement

The participants of this study did not give written consent for their data to be shared publicly, so due to the sensitive nature of the research supporting data is not available.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Arvidson, M., et al., 2013. Valuing the social? The nature and controversies of measuring social return on investment (SROI). Voluntary sector review, 4 (1), 3–18.

- Barraket, J., and Loosemore, M., 2018. Co-creating social value through cross-sector collaboration between social enterprises and the construction industry. Construction management and economics, 36 (7), 394–408.

- Barraket, J., 2020. The role of intermediaries in social innovation: The case of social procurement in Australia. Journal of social entrepreneurship, 11 (2), 194–214.

- Barraket, J., Keast, R., and Furneaux, C., 2016. Social procurement and New Public Governance. Oxon, UK: Routledge.

- Bridgeman, J., and Loosemore, M., 2023. Evaluating social procurement: a theoretically informed and methodologically robust social return on investment (SROI) analysis of a construction training initiative developed to reduce the risk of youth homelessness in Wales. Construction management and economics, 42 (5), 387–411.

- Burström, B., and Tao, W., 2020. Social determinants of health and inequalities in COVID-19. European journal of public health, 30 (4), 617–618.

- Campbell, M.A., and Gunning, J.G., 2020. Strategies to improve mental health and well-being within the UK construction industry. Proceedings of the institution of civil engineers-management, procurement and law, 173 (2), 64–74.

- Crook, D., and Tessler, A., 2021. The cost of doing nothing report. Sydney, Australia: BIS Oxford Economics. https://www.constructors.com.au/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/Cost-of-doing-nothing.pdf

- Dahlgren, G., and Whitehead, M., 2021. The Dahlgren-Whitehead model of health determinants: 30 years on and still chasing rainbows. Public health, 199, 20–24.

- Denny-Smith, G., et al., 2021. How Construction Employment Can Create Social Value and Assist Recovery from COVID-19. Sustainability, 13 (2), 988.

- Denny-Smith, G., and Loosemore, M., 2017. Integrating Indigenous enterprises into the Australian construction industry. Engineering, construction and architectural management, 24 (5), 788–808.

- Dunn, K.M., et al., 2011. Racism, tolerance and anti-racism on Australian construction sites. The International journal of diversity in organisations, communities and nations, 10 (6), 129–148.

- Flyvbjerg, B., 2001. Making social science matter: Why social inquiry fails and how it can succeed again. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Gioia, D.A., Corley, K.G., and Hamilton, A.L., 2013. Seeking qualitative rigor in inductive research: Notes on the Gioia methodology. Organizational research methods, 16 (1), 15–31.

- Guest, G., MacQueen, K. M., and Namey, E. E., 2012. Applied thematic analysis. Thousand Oaks: Sage.

- Gusoff, G.M., et al., 2023. Moving upstream: healthcare partnerships addressing social determinants of health through community wealth building. BMC public health, 23 (1), 1824.

- Hill, S.E., and Friel, S., 2020. ‘As long as it comes off as a cigarette ad, not a civil rights message’: gender, inequality and the commercial determinants of health. International journal of environmental research and public health, 17 (21), 7902.

- Hurt-Suwan, C.J.P., and Mahler, M.L., 2021. Social procurement to reduce precarious employment for Māori and Pasifika workers in the construction industry. Kōtuitui: New Zealand journal of social sciences online, 16 (1), 100–115.

- Indig, D., et al., 2018. Pathways for scaling up public health interventions. BMC public health, 18, 1–11.

- Irvine, A., and Rose, N., 2022. How does precarious employment affect mental health? A scoping review and thematic synthesis of qualitative evidence from western economies. Work, employment and society,

- Lou, C.X., et al., 2023. A systematic literature review of research on social procurement in the construction and infrastructure sector: barriers, enablers, and strategies. Sustainability, 15 (17), 12964.

- Kelley, A., 2020. Public health evaluation and the social determinants of health. Routledge.

- Keene, K., Keating, K., and Ahonen, P., 2016. The power of stories: enriching program research and reporting. OPRE Report# 2016-32a. Washington, DC: Office of Planning, Research and Evaluation, Administration for Children and Families, US Department of Health and Human Services.

- Kivimaa, P., et al., 2019. Towards a typology of intermediaries in sustainability transitions: A systematic review and a research agenda. Research policy, 48 (4), 1062–1075.

- Klerkx, L., and Leeuwis, C., 2009. Establishment and embedding of innovation brokers at different innovation system levels: Insights from the Dutch agricultural sector. Technological forecasting and social change, 76 (6), 849–860.

- Lee, J., et al., 2018. Addressing health equity through action on the social determinants of health: a global review of policy outcome evaluation methods. International journal of health policy and management, 7 (7), 581.

- Lingard, H., and Turner, M., 2017. Work and well-being in the construction industry. In: R.J. Burke and K.M. Page, eds. Research handbook on work and well-being. Cheltenham, UK: Edward Elgar, pp. 189–215.

- Loosemore, M., Higgon, D., and Osborne, J., 2020. Managing new social procurement imperatives in the Australian construction industry. Engineering, construction and architectural management, 27 (10), 3075–3093.

- Loosemore, M., Osborne, J., and Higgon, D., 2021. Affective, cognitive, behavioural and situational outcomes of social procurement: a case study of social value creation in a major facilities management firm. Construction management and economics, 39 (3), 227–244.

- Loosemore, M., et al., 2022. The risks and opportunities of social procurement in construction projects: a cross-sector collaboration perspective. International journal of managing projects in business, (ahead-of-print).

- Madden, M., and McCambridge, J., 2021. Alcohol marketing versus public health: David and Goliath? Globalization and health, 17 (1), 1–6.

- Marmot, M., 1997. Inequality, deprivation and alcohol use. Addiction, 92 (3s1), 13–20.

- Marmot, M., et al., 2008. Closing the gap in a generation: health equity through action on the social determinants of health. The lancet, 372 (9650), 1661–1669.

- Mauthner, N.S., and Doucet, A., 2003. Reflexive accounts and accounts of reflexivity in qualitative data analysis. Sociology, 37 (3), 413–431.

- McKee, M., and Stuckler, D., 2018. Revisiting the corporate and commercial determinants of health. American journal of public health, 108 (9), 1167–1170.

- McKinlay, J., 1979. A case for refocusing upstream: The political economy of illness. In: E. G. Jaco ed. Patients, physicians, and illness. 3rd ed. Free Press, 9–25

- Mialon, M., 2021. An overview of the commercial determinants of health. Globalization and health, 16 (1), 1–7.

- Natoli, R., Lou, C.X., and Goodwin, D., 2023. Addressing barriers to social procurement implementation in the construction and transportation industries: an ecosystem perspective. Sustainability, 15 (14), 11347.

- Parliamentary Inquiry (2022). Inquiry into Workforce Australia Employment Services. https://www.aph.gov.au/Parliamentary_Business/Committees/House/Workforce_Australia_Employment_Services/WorkforceAustralia

- Petersen, D., and Kadefors, A., 2016. Social Procurement and Employment Requirements in Construction. In: Chan, P W and Neilson, C J, eds. Proceedings 32nd Annual ARCOM Conference, Manchester UK: Association of Researchers in Construction Management, 997–1006.

- Popay, J., et al., 1998. Theorising inequalities in health: the place of lay knowledge. Sociology of health & illness, 20 (5), 619–644.

- Raiden, A., et al., 2019. Social value in construction. London: Routledge.

- Raphael, D., Curry-Stevens, A., and Bryant, T., 2008. Barriers to addressing the social determinants of health: Insights from the Canadian experience. Health Policy, 88 (2-3), 222–235.

- Rochford, C., Tenneti, N., and Moodie, R., 2019. Reframing the impact of business on health: the interface of corporate, commercial, political and social determinants of health. BMJ global health, 4 (4), e001510.

- Saunders, B., et al., 2018. Saturation in qualitative research: exploring its conceptualization and operationalization. Quality & quantity, 52 (4), 1893–1907.

- Shaw, K.M., et al., 2016. Chronic disease disparities by county economic status and metropolitan classification, behavioral risk factor surveillance system, 2013. Preventing Chronic Disease, 13, E119.

- Solar, O., and Irwin, A., 2010. A conceptual framework for action on the social determinants of health. Social Determinants of Health Discussion Paper 2 (Policy and Practice). World Health Organization. http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/10665/44489/1/9789241500852_eng.pdf

- Suchman, M.C., 1995. Managing legitimacy: Strategic and institutional approaches. Academy of management review, 20 (3), 571–610.

- Troje, D. (2020). Constructing social procurement: An institutional perspective on working with employment requirements. Unpublished PhD Thesis, Chalmers University of Technology.

- Troje, D., and Andersson, T., 2021. As above, not so below: Developing social procurement practices on strategic and operative levels. Equality, diversity and inclusion: an international journal, 40 (3), 242–258.

- Troje, D., and Gluch, P., 2020. Beyond policies and social washing: How social procurement unfolds in practice. Sustainability, 12 (12), 4956.

- Troje, D., and Kadefors, A., 2018. Employment requirements in Swedish construction procurement–institutional perspectives. Journal of facilities management, 16 (3), 284–298.

- Utzet, M., et al., 2020. Employment precariousness and mental health, understanding a complex reality: a systematic review. International journal of occupational medicine and environmental health, 33 (5), 569–598.

- Vancea, M., and Utzet, M., 2017. How unemployment and precarious employment affect the health of young people: A scoping study on social determinants. Scandinavian journal of public health, 45 (1), 73–84.

- Wood, B., Baker, P., and Sacks, G., 2022. Conceptualising the commercial determinants of health using a power lens: a review and synthesis of existing frameworks. International journal of health policy and management, 11 (8), 1251.

- WHO 2023. Social determinants of health. World Health Organization. https://www.who.int/health-topics/social-determinants-of-health#tab=tab_1

- Wilkinson, R. G., and Marmot, M., 1998. The solid facts: social determinants of health (No. EUR/ICP/CHVD 03 09 01). Copenhagen: WHO Regional Office for Europe.

- Yin, R. K., 2017. Case study research: Design and methods. Sage.