?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

Ephemeral media platforms allow users to send content in a format that automatically deletes the content after the recipient has accessed it – a phenomenon known as the ‘burn after reading’ principle. This study investigates whether awareness of the burn after read principle results in improved recognition memory for pictures. An experiment is designed where participants interact with pictures using a social media application. In Version A, participants are made aware of the persistent nature of the pictures, in Version B, participants are made aware of the ephemeral nature. Thereafter, participants are presented with the pictures again and must identify whether or not they previously encountered the exact same picture. Results showed that the burn after read principle does have a significant impact on accuracy in recognising pictures and the time spent watching them. Awareness of the burn after read principle resulted in better recognition memory for pictures and longer viewing times in the ephemeral application. This finding is in accordance with existing findings on the relationship between ephemerality and recognition memory.

1. Introduction

The massive use of social media transformed how we communicate. Social media platforms enable users to communicate beyond local boundaries and offer possibilities to share user generated content such as photos and videos. While at first social media were persistent in nature, enabling users to re-visit content, in recent years a new type of social media platforms emerged: ephemeral social media platforms. These platforms display content for a limited period of time and use the burn after read principle. This ensures that shared content self-destructs after a period of time set by the sender (Charteris, Gregory, and Masters Citation2014). Ephemeral social media platforms have become a prominent component of our social ecosystem (Bayer et al. Citation2016), e.g. Snapchat boasts over 186 million active users a day (Statista Citation2018). Other popular ephemeral social media applications are Wickr and iDelete (Kotfila Citation2014). In 2016, the until-then persistent application Instagram began to implement ephemerality by adding ‘Instagram Stories’. Facebook followed by introducing ‘Facebook Live’. However, not only social media platforms implemented ephemerality, recently ephemerality found its way into the business environment. Applications such as Confide adapted Snapchat-style messaging into something more formal. Since ephemerality is on the rise, it is interesting to see whether the burn after read principle has effects on recognition memory. Insights can contribute to the body of knowledge of Cognitive Ergonomics research (how interactions affect cognition) and to best practices in interaction design.

2. Related work

There have never before been more ways to communicate with one another. Once limited to face-to-face conversation, we have developed new technologies for interaction (Baym Citation2015). The first technologies invented were the ones that enabled people to directly talk to one another at a distance. Telephone and video chat are examples of technologies enabling synchronous communication. Later on, technologies were invented that not only enabled people to talk to one another without being physically co-present, but even enabled people to communicate without being time-synchronised. This phenomenon, of which sending and receiving letters is the precursor, is known as a-synchronous communication. The digital age provided us with many a-synchronous communication platforms, of which email, chat, web boards and social networking sites are examples (Baym Citation2015). In the early years of digital a-synchronous communication, all communication artefacts were characterised by persistence; they were saved for an undetermined period of time. Just as letters persist from the moment they are sent until the moment the receiver disposes of them, e-mails persist from the moment they are sent until the moment the receiver deletes them. When an e-mail is not deleted, it will forever persist in the mailbox of the receiver. A visual representation of the concept of persistence is provided in . The horizontal line represents time of persistence.

Synchronous communication contains some form of persistence as well. However, the time frame of persistence (Shein Citation2015) of synchronous communication artefacts is so short that we never use the term persistent here. Instead, the term ephemerality is used, which is defined as ‘the property of lasting for a very short period of time’. Ephemerality in synchronous communication is seen as a result of in-the-moment phenomena, as described by Charteris, Gregory, and Masters (Citation2014). This phenomenon can be best explained by considering spoken language. The present of spoken language is limited to the time span within which the speaker and hearer can retain it in memory. When this time span expires, the things said ‘disappear’ and can never be retrieved again, unless it is recorded (Auer Citation2009). A visual representation of the concept of ephemerality is provided in .

2.1. Ephemerality as an alternative for persistence

Ephemerality has recently found its way into the digital, a-synchronous world. As the internet has become a common medium for personal expression and communication, people's expectation of data persistence greatly increased (Shein Citation2015). As Lee Raine, director of the Pew Research Center's Internet & American Life Project, states: ‘People are becoming increasingly aware that some social media platforms keep a permanent record of all that they post and all that they comment on’. According to Raine, people are beginning to recognise that the context of a post can be misunderstood by readers. When a post that has been misunderstood stays out there on the internet, the post can possibly cause problems; a scenario people are not willing to risk (Shein Citation2015). In response to persistent data's potential risks, a number of (a-synchronous) communication services have designed their platforms around ephemerality. These platforms, of which Snapchat is the most known, erase communication artefacts after a short period of time (Bayer et al. Citation2016). Ephemeral or self-destructing applications thus allow users to send messages, pictures, videos or other communication in a format that automatically deletes the communication artefact after the recipient of the artefact has accessed it (McPeak Citation2017). The automatic deletion of communication artefacts is known as the burn after read principle (Lin, Mayblum, and Kupsh Citation2016). Ephemeral platforms are often lightweight media for sharing spontaneous, mundane experiences with close social ties (Bayer et al. Citation2016). The use of ephemeral applications is popular especially amongst youngsters (Kofoed and Larsen Citation2016).

2.1.1. Snapchat

One of the most well-known and fastest growing ephemeral media applications is the messaging and photo sharing application Snapchat which was launched in 2011 (Anderson Citation2015). Snapchat gained great popularity over the years; the latest report, which entails the third quarter of 2018, shows that Snapchat now has around 186 million daily active users worldwide (Statista Citation2018). What makes Snapchat so popular, is that it allows users to send photos or videos, so called snaps, to friends and that these snaps dissolve after a specified period of time (Utz, Muscanell, and Khalid Citation2015). By default, the application deletes all content that is shared after the recipient opens it (Kotfila Citation2014). The burn after read principle is one of Snapchat's main features. Although Snapchat states that communication artefacts send through Snapchat are deleted from all of Snapchat's servers as soon as the recipient of the artefact has accessed it, this is doubted by some (Roesner, Gill, and Kohno Citation2014). However, this does not stop many users from using the application. The process of sharing a snap on Snapchat, as described by Piwek and Joinson (Citation2016), works as follows: the sender makes an image or video using the Snapchat application and then determines for how long the image or video will be viewable by the receiver. When the sender posts an image or video to the receiver, this image or video automatically vanishes from the senders' phone. The only information left is a timestamp of when the snap was sent, and whether the snap has been opened or not. The receiver is able to view the image or video for the time chosen by the sender. After this viewing time has ended, the image or video disappears from the receivers' phone.

2.1.2. Confide

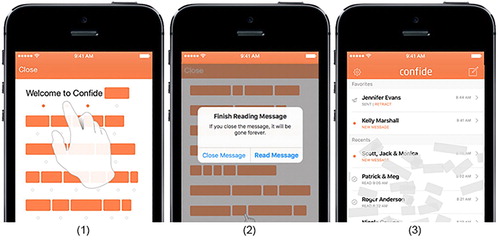

Ephemerality also found its way into the business environment. In 2013, the encrypted instant messaging application Confide was released, which adapted Snapchat-style ephemeral messaging into something more formal. Jon Brod, one of Confide's founders, stated: ‘Confide is to Snapchat, what LinkedIn is to Facebook’ (Bloomberg Citation2015). Confide strives to make it easier to share sensitive information with colleagues and offers users a possibility to send messages that are only readable a few words at a time. The receiver ‘wands’ over words with his finger to read them (). As the user's finger moves across the words, they disappear. Once the user chooses to reply or exit out, the message self-destructs and disappears forever. Confide also offers photo, video, document and voice messaging and like text, all these communications are ephemeral (Confide Citation2019).

2.2. Recognition of content

Recognition is a fundamental facet of our ability to remember. It requires a capacity for both identification and judgement of the prior occurrence of what has been identified (Mandler Citation1980). Recognition memory is the ability to judge that a currently present object, person, place or event has previously been encountered or experienced. For the purpose of this study, the focus is on recognition memory for pictures. It was demonstrated that humans can distinguish large sets of perceived pictures from new distractor pictures with high levels of accuracy (Pezdek Citation1987). More recent studies on picture recognition do not use pictures in which the distractor is a completely new picture, but use a same-changed, or same-different recognition test, in which the distractor picture is the same as the picture presented to the participant in the sequence of pictures, but with a small change. Shaffer and Shiffrin (Citation1972) found improved performance as a result of increasing picture presentation time. Several other studies have reported that recognition memory for pictures increases with the duration of exposure (Loftus and Bell Citation1975). The interpretation of these results was that increased exposure duration leads to better remembrance.

2.3. Recognition memory and ephemerality

Recognition memory experiments recently found their way into the domain of ephemerality and its mechanisms. Ephemeral media applications anticipate on the rising interest of so-called forgetting features (Bannon Citation2006). Because content disappears after it has been viewed once, is not saved and could never be retrieved again, the receiver of the content is expected to forget the content when time passes. However, because there is some kind of exclusivity present when receiving a message containing ephemeral content, the opposite can also be true. Some researchers state that because of self-destruction, in this research referred to as burn after read, receivers attend more closely to content, resulting in less loss (or forgetting), and better remembrance of information. Research on memory and photo taking by Henkel (Citation2014) indicates that the ephemeral experience of viewing art in a museum through one‘s own eyes results in better memory of the art than taking photographs of the art. Being aware of ephemerality, knowing that you will not be able to observe an artwork again once you leave the museum, results in better remembrance of the objects perceived. Analogously, in the context of learning, Cornelius and Owen-DeSchryver (Citation2008) showed that students having complete (instructor-provided) notes performed worse on tests than students that had incomplete lecture notes. The rationale for this could be that knowing that certain information is not there (incomplete) provokes more elaboration and encoding by the learner. Another example of how deeper processing can be provoked by making something ‘more difficult’ is a study by Diemand-Yauman, Oppenheimer, and Vaughan (Citation2011) which showed that information in hard to read fonts was remembered better than information in regular fonts. Interviews conducted by Bayer et al. (Citation2016) provide the same sort of conclusion. Interviewees indicated that the disappearance of messages sent through the ephemeral photo sharing application Snapchat leads them to being more vigilant about attending to a message, because of the limited opportunity to interpret the content of the message. According to Bayer et al. (Citation2016), this will possibly lead to more remembrance of the message.

2.4. Research question

Ephemeral media applications such as Snapchat and Confide were designed in response to persistent data's potential risks and erase communication artefacts after the recipient has accessed it, a phenomenon known as the burn after read principle. Awareness of the burn after read principle has been researched in several recognition memory studies and is said to have a positive effect on the remembrance of previously encountered information. Although some assumptions are being made, this effect was never quantified specifically for information sent through ephemeral media applications. This study aims to fill this gap by conducting a memory experiment. The following research question was formulated:

Does awareness of the burn after read principle result in improved recognition memory for pictures sent through media applications?

Although both sending and receiving communication artefacts are involved in the process of communicating through (ephemeral) media applications, and both these acts might entail different ideas, actions and intentions of people, this study will specifically focus on the receiving side of (ephemeral) content sent through media applications.

3. Method

3.1. Experimental design

In the experiment participants navigate through an application which looked, behaved and felt (as experienced by the participants) either like a persistent media application or an ephemeral media application. Two versions, respectively ‘A’ (persistent) and ‘B’ (ephemeral) of a messaging application, were created (see ).

Table 1. Differences between versions A and B of the experiment.

The A and B versions differed in the fact that they provoked different feelings while interacting with the application. In the A version, participants needed feel they could open messages as many times as they would like to. In the B version, however, participants were made to feel that after they opened a message once, the content would self-destruct. Version B made participants aware of the burn after read principle. To provoke different feelings in versions A and B, several design decisions were made.

3.2. Material

In order to provoke different feelings and expectations of how the application behaves in experiments A and B, design decisions were made for all of the materials the participants interacted with. Both the A and B versions of the application consisted of three screens: an ‘opening’ screen, a ‘received messages’ screen and a ‘content of messages’ screen. The opening screen presented the icon of either the persistent application Whatsapp or the ephemeral application Snapchat. The ‘received messages’ screen presented all received, (un)opened messages. The ‘content of messages’ screen presented the content (picture) hidden behind each message.

The A version of the messaging application used in the experiment resembled the well-known messaging application Whatsapp (see a). The experiment application was designed in such a way that it looked like it had most of Whatsapp's primary functionalities, one of these functionalities being the ability to open conversations (messages) multiple times. The content of Whatsapp messages is by default permanent, it will never self-destruct, and therefore users can access received content at any time. The icon of Whatsapp was used on both the ‘opening’ screen and the ‘received messages’ screen.

Figure 4. Two versions of the application used in the experiment: (a) Design Version A (persistent) and (b) Design Version B (ephemeral).

The B version made participants aware of the burn after read principle. To create this awareness and to provoke the feeling that the content of messages self-destructs after opening them once, this version resembled Snapchat, it was designed in a way that it looked like it had most of Snapchat's primary functionalities, the most important being the burn after read principle (see b). The Snapchat icon was used on both the opening screen and the ‘received messages’ screen. The icon of Snapchat was used to indirectly remind the participant of the functionalities of Snapchat.

3.2.1. Pictorial content in four categories

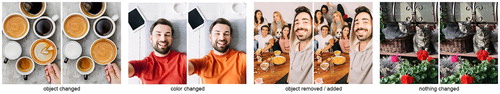

The 15 pictures included in the experiment were selected based on resemblance with content sent through social media applications such as Whatsapp and Snapchat. Research by Utz, Muscanell, and Khalid (Citation2015) stated that the most popular pictures sent through Snapchat were the ones in the categories ‘selfies’, ‘events’, ‘food’, ‘other people’, ‘animals’ and ‘drinking’. For nine of the obtained pictures, a variation was created. The nine variations were divided over three categories: ‘object changed’, ‘colour changed’ and ‘object removed or added’. The fourth category (nothing changed) contained six pictures which had no alternative. An example picture set of all categories is provided in .

In order to prevent from the order effect, pictures within applications A and B were randomised. Therefore, four versions were created within experiments A and B (A1–A4, B1–B4) with each version having a different order of presenting the pictures. Each version number, whether it was linked to A or B, got the same order (A1 and B1 got the same order, A2 and B2, etc.) Because the same-different test needed to present the pictures in the same order as pictures were presented in the application, each of the four versions within experiment A or B received their own ‘same-different test’.

3.2.2. Interaction with application

Participants navigate through an application which looked either like a persistent media application or an ephemeral media application. The application showed 15 messages with a visible notification icon. Participants were required to open these 15 messages in a top down order and study the pictures, in these messages carefully. There was no time limit attached to watching the content of each message.

3.2.3. Same-different recognition test

After interacting with the application participants were presented with a visual memory test, specifically the ‘same-different’ recognition test, as described by Pezdek (Citation1987). Participants were presented with a questionnaire containing 15 pictures. Nine of these were slightly different from the ones shown in the application, six were exactly the same. For each of the 15 pictures presented in the questionnaire was asked whether or not the picture was the same as the one the participant saw before in the application. If the participant indicated that a picture was different, the participant was asked what made the difference. The order in which the pictures in the same-different test were presented to the participant was the same as the order in which the pictures were presented to the participant while interacting with the application.

3.3. Participants and procedure

Participants were recruited mainly from Utrecht University where the experiment took place. Participants received instructions textually. They were not told their memory would be tested later on. In the A version, (persistent) participants were informed that messages could be opened multiple times. In the B version, (ephemeral) participants were informed that messages were self-destructing and could not be opened again. After instructions, participants were handed over the iPhone for the interaction task to begin. In both versions A and B, participants indicated when they had opened all the messages. The experiment ended with a same-different recognition test. Participants indicated whether the picture in the test was the same as, or different from the one shown in the application, and what the difference was if they thought there was one.

4. Results

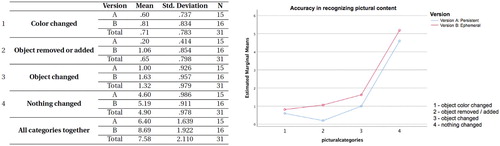

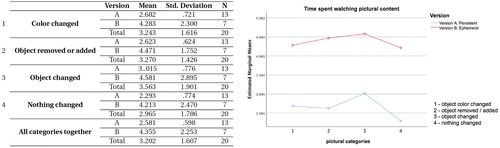

Thirty-one participants participated in the experiment, 16 in version A and 15 in version B. Repeated measures ANOVA was performed on the number of correctly recognised pictures (accuracy) and on the time spent watching pictorial content (in four categories).

4.1. Accuracy in recognising pictorial content

The null and alternative hypotheses of the first hypothesis are formulated as follows:

H10 Correctly recognised pictures version A = Correctly recognised pictures ver. B

H11 Correctly recognised pictures version A < Correctly recognised pictures ver. B

There is a main effect for version on recognition, , p=0.002,

(). The average number of correctly recognised pictures (all categories) is higher for ephemeral version B

than for persistent version A

. The null hypothesis is rejected, the alternative hypothesis is accepted.

4.2. Time spent watching pictorial content

The null and alternative hypotheses of the second hypothesis are formulated as follows:

H20 Time spent watching pictures ver. A = Time spent watching pictures ver. B

H21 Time spent watching pictures ver. A < Time spent watching pictures ver. B

There is a main effect for version, , p=0.007,

The average time watching pictorial content (in all categories) is higher in ephemeral version B

than in persistent version A

, see . This results in the rejection of the null hypothesis and acceptance of the alternative hypothesis.

5. Conclusion and discussion

This study investigated the effect of the burn after read principle on recognition memory for pictures. Research into this issue, knowing how certain behaviours in the interface affect cognition can show to be relevant for ergonomics and design decisions of future applications. Both ‘accuracy in recognising pictures’ and ‘time spent watching pictures’ were influenced by the burn after read principle. Participants who were aware of the applications' ephemeral features recognised more pictures than those who were aware of the persistent features. The same was true for the time watching pictorial content; participants who used the ephemeral application watched the content for a longer time. We conclude that the burn after read principle has a significant impact on how content is processed. This can be explained in various ways. There is a sense of exclusivity in ephemeral messages, one has limited opportunity to interpret the content due to its self-destructing mechanism. This might be why participants using the ephemeral application spent more time watching the content. Perhaps being aware that this is the only chance to indulge the information made that they watched it until they knew they had processed all. Knowing that one can open messages again might cause one to just ‘glance’ over the picture, leaving details behind. Indeed, awareness of the disappearance of messages sent through the ephemeral application lead to more remembrance of the content of messages perceived. This study has some limitations such as the small group sizes. Furthermore, most participants were students of Utrecht University. As such, it is difficult to generalise the findings of this research. Also, the experiment was conducted in a controlled environment, which is likely to make the participants act differently from normal. The fact that participants knew they were taking part in an experiment may influence their cognitive processes, but this holds in both experimental conditions, and effects were found.

A final issue is that ‘presentation time’ and ‘accuracy’ are measured as two independent variables influencing recognition. However, ‘presentation time’ and ‘accuracy’ might share a mutual relationship, influencing each other. Despite limitations there are opportunities. Advertising through ephemeral media applications, in which the burn after read principle applies, might be more effective than advertising through persistent media applications. A potential customer might recognise advertisements perceived through an ephemeral application in a subsequent encounter more quickly than through a persistent application. However, this would only hold when the customer can be assumed to be interested in the content, but social media have their ways of smartly targeting advertisements to particular users based on profiling.

In future research, other content such as text and videos could be included. Also, additional research could focus on non-social media applications such as business apps to see if results found in this study apply to more formal applications as well. Using real friends and acquaintances as contacts might also be interesting to look at since some participants indicated that if the experiment would have had messages from people they personally know, they would have been more interested or curious. This might result in more attention to and remembrance of the pictorial content.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Anderson, K. 2015. “Getting Acquainted with Social Networks and Apps: Snapchat and the Rise of Ephemeral Communication.” Library Hi Tech News 32 (10): 6–10.

- Auer, P. 2009. “On-line Syntax: Thoughts on the Temporality of Spoken Language.” Language Sciences 31 (1): 1–13.

- Bannon, L. J. 2006. “Forgetting as a Feature, Not a Bug: the Duality of Memory and Implications for Ubiquitous Computing.” CoDesign 2 (1): 3–15.

- Bayer, J. B., N. B. Ellison, S. Y. Schoenebeck, and E. B. Falk. 2016. “Sharing the Small Moments: Ephemeral Social Interaction on Snapchat.” Information, Communication & Society 19 (7): 956–977.

- Baym, N. K. 2015. Personal Connections in the Digital Age. Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Bloomberg. 2015. Confide: The Snapchat like App for Executives. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=QAyStQSVvPY, urldate=2019-01-21.

- Charteris, J., S. Gregory, and Y. Masters. 2014. “Snapchat ‘Selfies’: The Case of Disappearing Data.” Rhetoric and Reality: Critical Perspectives on Educational Technology 13: 389–393.

- Confide. 2019. https://getconfide.com, urldate = 2019-01-21.

- Cornelius, T. L., and J. Owen-DeSchryver. 2008. “Differential Effects of Full and Partial Notes on Learning Outcomes and Attendance.” Teaching of Psychology 35 (1): 6–12.

- Diemand-Yauman, C., D. M. Oppenheimer, and E. B. Vaughan. 2011. “Fortune Favors the Bold (and the Italicized): Effects of Disfluency on Educational Outcomes.” Cognition 118 (1): 110–115.

- Henkel, L. A. 2014. “Point-and-Shoot Memories: The Influence of Taking Photos on Memory for a Museum Tour.” Psychological Science 25 (2): 296–402.

- Kofoed, J., and M. C. Larsen. 2016. “A Snap of Intimacy: Photo-Sharing Practices Among Young People on Social Media.” First Monday 21 (11).

- Kotfila, C. 2014. “This Message Will Self-destruct: The Growing Role of Obscurity and Self-destructing Data in Digital Communication.” Bulletin of the Association for Information Science and Technology 40 (2): 12–16.

- Lin, Z., A. Mayblum, and J. Kupsh. 2016. Transmitting and Receiving Self-Destructing Messages, US Patent 9,432,382.

- Loftus, G. R., and S. M. Bell. 1975. “Two Types of Information in Picture Memory.” Journal of Experimental Psychology: Human Learning and Memory 1 (2): 103.

- Mandler, G. 1980. “Recognizing: The Judgment of Previous Occurrence.” Psychological Review 87 (3): 252.

- McPeak, A. 2017. “Self-Destruct Apps: Spoliation by Design.” Akron Law Review 51: 749.

- Pezdek, K. 1987. “Memory for Pictures: A Life-Span Study of the Role of Visual Detail.” Child Development 58: 807–815.

- Piwek, L., and A. Joinson. 2016. “What Do they Snapchat About? Patterns of Use in Time-limited Instant Messaging Service.” Computers in Human Behavior 54: 358–367.

- Roesner, F., B. T. Gill, and T. Kohno. 2014. “Sex, Lies, or kittens? Investigating the Use of Snapchats Self-Destructing Messages.” In Proceedings of the International Conference on Financial Cryptography and Data Security, 64–76.

- Shaffer, W., and R. M. Shiffrin. 1972. “Rehearsal and Storage of Visual Information.” Journal of Experimental Psychology 92 (2): 292.

- Shein, E. 2015. “Ephemeral Data.” Bulletin of the Association for Information Science and Technology 56 (9): 20–22.

- Statista. 2018. Number of Daily Active Snapchat Users From 1st Quarter 2014 to 3rd Quarter 2018. www.statista.com/statistics/545967/snapchat-app-dau/,urldate=2018-12-30.

- Utz, S., N. Muscanell, and C. Khalid. 2015. “Snapchat Elicits More Jealousy Than Facebook: A Comparison of Snapchat and Facebook Use.” Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking 18 (3): 141–146.