?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

Life-changing events (or LCEs) can alter a person's status quo and threaten well-being. Previous research investigated distinct LCEs, where participants already used technology routinely. This paper reports the results of two field studies through which we compared supports people refer to when experiencing different LCEs. Together with users of technology, our sampling included participants who specifically did not refer to online services and tools to seek help during their LCE. We found that popular services people refer to are inattentive to the needs of people experiencing an LCE as they do not allow forms of progressive engagement and disclosure within the service. We also found that popular services are imprudent as their design might expose users experiencing an LCE to more sources of stress. Finally, we found that these services are inapt to support these users as they do not provide direct forms of interactions with experts.

1. Introduction

Life-changing events (or LCEs) come in many forms but commonly disrupt life and routine in significant ways (e.g. the birth of a child, a layoff, a wedding, a divorce, a bereavement). We call these events changing because they can disrupt the psychological well-being of the person who experiences them and can alter the status quo of their life. Even if LCEs are quite different in nature, they have many characteristics in common: they rarely occur, they are complex and rough on both emotional and logistical aspects, they lead to uncertainty, and people experiencing them often also undergo stress and anxiety (Kanner et al. Citation1981). For all these elements, it is difficult for one person to handle all this alone. This is why people living through these events frequently require help and support. Technologies and the Internet can help with various aspects of an LCE. Some services support particular LCEs exclusively by giving access to appropriate information or professionals and Online Social Networks (or OSNs)Footnote1 are a way to connect supportive family and friends. Furthermore, there are services that have been designed explicitly to support various LCEs. For example, The Knot (XO Group Inc Citation2019) is a service specialised in supporting couples during the planning and management of their wedding; The Retirement Café (Zelinski Citation2019) is a website built to provide consulting to new retirees or those about to retire; Umer is a mobile app designed to assist the bereaved through each stage of arranging a funeral (Umer Ltd Citation2020). In the remaining of this paper, we will refer collectively to online services and tools that people can use to receive support with the term Information and Communication Technology (or ICT). Under this term, we will group both the services specifically designed to support LCEs with the more general purpose tools.

Interest has grown in the field of human–computer interaction (or HCI) on how to best assist users experiencing an LCE (e.g. Massimi and Baecker Citation2011; Gibson and Hanson Citation2013; Moncur, Gibson, and Herron Citation2016). Particularly, understanding the causes of frustration while interacting with technologies before, during and after an event. These seminal works highlighted challenges or opportunities and offer guidelines for designing technology with these users in mind. However, although this research furthered understanding of the positive and negative effects of technology during an LCE, most focused on specific types of event with participants who were already using technology routinely.

We conducted a comparative study of users and non-users of twoICT during a variety of LCEs, discovering implications that could have been missed by a singular focus on established users of technologies (Fleming Citation1970). We sought to find unexpected trends in resistance that could lead non-users to refuse technology in ‘active and considered ways’ (Satchell and Dourish Citation2009, 11) and what similarities existed between user and non-user coping strategies across distinct LCEs. It was not our intent to examine the variance of positive (eustress) or negative (stress) consequences of LCEs or the events themselves, rather to discern design insights afforded by the contrast/comparisons of coping strategies.

We found that solutions for people experiencing an LCE are often inattentive, as often lacking personal information about the user through which they could provide customised forms of support; imprudent, as often exposing user to unwanted or unhelpful interaction with peers; and inapt, as often unable to allow users to fully express the nuances of their emotional and psychological status.

This research provides empirical evidence on qualities that services should adopt in order to improve support for users experiencing LCEs. We contribute design and policy implications to support people undergoing LCEs. We conclude by suggesting further avenues of research into users experiencing severe disruptions in life.

2. Related work

LCEs have been studied extensively in the literature of stress. To measure the impact these events produce and the readjustment they require from people experiencing them, Holmes and Rahe (Citation1967) devised the life-change model and social-readjustment rating scale (Holmes and Rahe Citation1967). This study presented a list of 43 life events that caused stress and required readjustment. Other studies built taxonomies from this initial work. Using data from a large-scale survey, Tausig (Citation1982) published a systematic description of LCEs (Tausig Citation1982) to study the relationship between LCEs and depressive symptoms. What emerges from this seminal research is that LCEs are diverse, and associated stress can be good and bad. Whether it is beneficial (eustress), harmful or unpleasant (distress); life change is the constant of LCEs. LCEs are also specific in that they give rise to different needs. Particularly, some LCEs might be unanticipated (e.g. a severe illness, death of a family member) and might not give time to people to prepare. By contrast, other LCEs might be anticipated long before changes can occur (e.g. weddings, birth of a child). Other LCEs could be discretionary, as they may rely on the agency of the individual (e.g. leaving a partner). In the rest of this article, we will follow the work of Holmes and Rahe (Citation1967) to organise the LCEs. We started from the list of events of the SRR scale (Holmes and Rahe Citation1967, 216). We then conducted a literature review on several engines combining in each query a life event from the list with the keywords: ‘HCI’, ‘technology’ and ‘field study’. We then examined the matching entries and included them in the review if these described relevant implications for HCI. By doing this we realised that several life events had been studied together in past research, therefore we merged these events in categories of events. For instance, ‘Death of a spouse’, ‘Death of a close family member’ and ‘Death of a close friend’ were merged into a single category. Also, we could not find relevant literature for some of the events in the list (e.g. ‘Jail term’, ‘Sex difficulties’). Vice versa, we learned that the original list of events of Holmes and Rahe (Citation1967) was by no means exhaustive of LCEs that had been studied in HCI.Footnote2 presents the categories that we developed and for which we could find relevant literature. Next, we review prior studied that covered several LCEs.

Table 1. Major life changing events described by Holmes and Rahe (Citation1967).

2.1. Previous reviews of LCEs

Recent studies have focused on the role of technology during LCEs. They uncovered typical challenges associated with ICT during these events; laying out design implications for solutions in future. Although the majority focused on specific LCEs, some incorporated several. For instance, Dimond, Shehan Poole, and Yardi (Citation2010) examined posts on a forum containing keywords such as marriage, death, divorce, illness, unemployment and retirement, Massimi, Dimond, and Le Dantec (Citation2012) analyse intimate partner violence, homelessness and death. These studies saw recurrent patterns around social and technological reconfiguration (i.e. how their social routines and technological usage changed in response to the LCE). Research in this area can be organised in four themes: (1) the role of ICT as a source of support for people experiencing an LCE; (2) research which identified ICT as a cause of distress during an LCE; (3) the use of ICT to remember people or events; (4) the use of ICT to manage digital assets. Crucially, in this this first point, research identified OSNs as a source of support and difficulties. Next, we will review these areas of research.

2.2. ICT as a source of enabling and caring support

Humans tend toward the formation of relationships that provide social capital – benefits that are difficult to attain otherwise (e.g. trust, help, reciprocity) (Coleman Citation1988). Social support is grouped broadly into two areas: enabling social support (helping individuals solve or rectify sources of distress) and caring support/relational support (comforting without direct rectification).

Past research has highlighted the role of online social networks and computer-mediated communication in facilitating access to information or expertise that can help during LCEs. Liu, Inkpen, and Pratt (Citation2015) found the Internet as an invaluable source of information for people experiencing a personal injury and their caregivers. ICT plays an increasing role in facilitating coordination work during LCEs that allow the planification of responses to an event: e.g. in the case of divorce (or separation) (Odom, Zimmerman, and Forlizzi Citation2010b), marriage (Vetere et al. Citation2005), retirement (Salovaara et al. Citation2010), change of residence (Shklovski and Mainwaring Citation2005). In the context of job search, enabling support can diminish the negative effects of unemployment or job searches by mitigating the effects of low self-esteem, or efficacy (Lacković-Grgin et al. Citation1996; Uchino, Cacioppo, and Kiecolt-Glaser Citation1996). Particularly, weak ties (i.e. non-immediate connections) can be sources of information about job opportunities (Granovetter Citation1973). Similarly, many apps and services support new parents; many systems facilitate the retrieval of information or organising professional care (Brady and Guerin Citation2010).

Past research has also revealed the important role of online social networks and computer-mediated communication in supporting people experiencing LCEs with caring support. ICT can help with the persistence of vital connections (e.g. hospitalised children remotely attending class activities) that can help maintain a sense of purpose (Liu, Inkpen, and Pratt Citation2015). More in general, ICT now plays an increasing role in enabling people to continuously share many parts of life while not being physically together (i.e. the presence-in-absence). For instance, this can support romance (Vetere et al. Citation2005), a child leaving home (Magdol Citation2002), creating new contact or maintain contact with a previous social network during a relocation (Shklovski, Kraut, and Cummings Citation2008). In the context of unemployment, caring support can be a source of encouragement and psychological nurturing (Blustein, Kozan, and Connors-Kellgren Citation2013, 263) that can mediate the negative effect of a prolonged period of unemployment (Lacković-Grgin et al. Citation1996; Uchino, Cacioppo, and Kiecolt-Glaser Citation1996). In the context of childbirth, new parents can sometimes experience social isolation, loneliness that can precipitate depression (Edhborg et al. Citation2005). Parents often seek support from peers in similar circumstances (Gibson and Hanson Citation2013; Toombs et al. Citation2018). Social connections are essential to parent or child well-being throughout pregnancy and after birth (Meadows Citation2010). In the context of changing habits or setting up new healthy routines, HCI studies show the importance of satisfying relatedness needs through social circles to achieve desirable behavioural changes; they find that the most successful modes involved a supportive and proactive involvement. Maitland and Chalmers (Citation2011) found peer groups provide motivation, drive, and a frame of reference for evaluating the weight-management efforts (Maitland and Chalmers Citation2011). Similar results were observed in the context of physical training (Schraefel et al. Citation2009) and smoking cessation (Murnane et al. Citation2014). Furthermore, previous work conducted with a particular focus on gender transition has documented that during LCEs, people often communicate with other people who are facing the same LCE, who are not experts and also not people whom they have known previously (an example of what has been called social transition machinery (Haimson Citation2018)). Similar behaviour was observed also by researchers studying abusive behaviour (Andalibi et al. Citation2018) and transition into motherhood (Britton, Barkhuus, and Semaan Citation2019). In summary, ICT enables new forms of communication that are pivotal to people experiencing LCEs toward the reestablishment of equilibrium. Unfortunately and as we will review next, technology (and OSNs) in particular, can also hinder these expressions (Burke and Kraut Citation2013).

2.3. ICT as a cause of distress

Research has shown that OSNs are often used to communicate new circumstances, life progress and separation, but the complexity of computer-mediated communication (or CMC) can often lead to misunderstandings and harassment (Moncur, Gibson, and Herron Citation2016). Unfortunately, OSNs especially introduce many new problems to relationships (e.g. exposing change of relationship statuses) which could be improved by allowing greater visibility and controls within the context of these periods (Odom, Zimmerman, and Forlizzi Citation2010b). In the context of bereavement, researchers have reported the stress that the bereaved sometimes experience when internet services resurface old information on the missing person (Massimi and Baecker Citation2010; Odom et al. Citation2010a). Where a condition is profoundly personal or the subject of stigmas or stereotypes (like in the context of personal injury or illness), caregivers may avoid reaching out for support on OSNs because they are worried about affecting the social status of the sufferer (Yamashita et al. Citation2013). At the same time also sufferers might refrain from sharing their personal health information on social media, which is perceived as a place for regular and fleeting content rather than a forum for persistent discussion on life's challenges or ‘sick’ users (van der Velden and El Emam Citation2013; Andalibi and Forte Citation2018). Vetere et al. (Citation2005) studied intimacy mediated by technology and found three main implications: first, communication mediated by technology is intrinsically prone to misinterpretation and can lead to disputes. Second, the private and public boundaries of social networks are often volatile, which can also lead to problems (e.g. sharing a picture depicting multiple people online without their consent). Finally, social networks and IT, in general, offer opportunities for people to be controlling or abusive toward partners (Dimond, Fiesler, and Bruckman Citation2011; Freed et al. Citation2017 Citation2018).

Research has also revealed that OSNs do not sufficiently enable people experiencing LCEs to express their questions and frustrations for fear of being judged. In the context of becoming parents, many entangle the ideal of a super parent with their identity and might feel that expressing frustrations, doubts or tiredness of the new condition is not appropriate (Gibson and Hanson Citation2013; Toombs et al. Citation2018). Ammari and Schoenebeck (Citation2015) found new fathers felt constrained discussing challenges of parenthood on OSNs for fear of being judged; sometimes withholding their identities strategically (Ammari and Schoenebeck Citation2015 Citation2016). Similar issues has been found also in the context of child starting college and leaving home. While social networks offer great opportunities to keep in touch with the family, they are also a source of worry because students often want to present, develop, and maintain two distinct identities, one for their family and one for their friends (Farnham and Churchill Citation2011; Smith et al. Citation2012). For example, though it could be OK to show to friends a picture of drinking alcohol during a night out, the same picture could be considered inappropriate to show to parents. ICT is often used to create mementos of events. During LCEs this takes a very special meaning, as we will review next.

2.4. Memorialisation across LCEs

People experiencing death of a child, spouse or close relatives need time and space to elaborate the loss. Digital artefacts can help with remembering the deceased and play an extremely important psychological role for the bereaved. However, studies on bereavement reveal how current technology is often rigid with regard to mourning. Massimi and Baecker (Citation2011) stress how grief is not a problem to be solved, as it has its psychological functions and merit (Massimi and Baecker Citation2011). OSNs are particularly inflexible with regard to letting heirs take control of the accounts of the deceased. Often, these services do not afford features to provide a memorial to those who passed away.

In a similar manner memorialisation is also extremely important in the case of LCEs generating eustress. Marriage or becoming parents are transformative and meaningful events in a person's life. Pictures and videos are created by the organisers of weddings and their families and friends and used during the event to enrich their physical participation in the ceremony and to re-experience the magic of the event after it has passed (Massimi, Harper, and Sellen Citation2014). Pictures and videos are also often used by parents to create memories of the birth and growth of their children. This content is often shared through OSNs to connect with the larger families of the parents, friends and particularly peers having children of their own (Gibson and Hanson Citation2013). In particular, sharing experiences with other parents provides reassurance and strength because new parents realise that others might face similar challenges. This contributes to the feeling of normalcy (Brady and Guerin Citation2010). Another set of implication for LCEs identified in prior HCI research concerns the management of digital artefacts that are typically generated prior the event starts. We will review these next.

2.5. Management of digital assets during LCEs

Though inheriting physical assets is a well-established (and regulated) practice, there are no conventional practices around the inheritance of digital artefacts (Massimi and Baecker Citation2010). Researchers report about the painful experiences of family members who try to access the deceased's accounts, and the novel privacy issues that rise from having access to their files (Odom et al. Citation2010a). Foong (Citation2008) conducted a study on end-of-life decision making. The study revealed that people have a complex and nuanced approach to their end-of-life arrangements in establishing their ‘advance directives’ and that current interactive systems are unable support the users in this act of negotiation with peers and family members. The implications of this work focuses on the design of technology that could support more nuanced practices of ownership (Odom et al. Citation2010a), enabling the owner to designate a heir for their digital assets and arrange for some of these artefacts to disappear at the end of her life (Odom et al. Citation2010a).

In the context of divorce, separation and breakups, research reveals how current technology is often inflexible for the management of shared digital assets and splitting shared accounts (Moncur, Gibson, and Herron Citation2016). On the positive side, technology plays a very important role in providing means for separated parents to manage their responsibilities of their children: it enables the parents to communicate remotely (Odom, Zimmerman, and Forlizzi Citation2010b). However, this research suggests the design of more flexible coordination systems for distributed families and highlights the limits of current calendaring systems (Odom, Zimmerman, and Forlizzi Citation2010b; Thayer et al. Citation2012). Furthermore, current solutions do not afford enough opportunity for the remote parent to provide care (Yarosh, Denise Chew, and Abowd Citation2009). Finally, this work suggests that more flexibility should be crafted into digital services to disentangle ownership of accounts and shared digital assets.

Research on LCEs suggest that people adopt distinct strategies to cope with the event; some of these strategies benefit from technologies and others do not require ICT. We argue it is vital to understand users that shy away from ICT during LCEs. People who do not use ICT during LCEs might choose to do so for reasons that possibly cannot be addressed by design. However, it is also possible that these people refuse to use technology in certain ways that speak about the limitations of the existing solutions. As we discuss in the next subsection, we propose to look at non-use as a broader form of technological appropriation.

2.6. Non-users of ICT

Studies agree that the digital divide is not a dichotomous concept composed only of people who use technologies and those who do not (Murdock Citation2002; Wyatt, Thomas, and Terranova Citation2002; Lenhart et al. Citation2003; Selwyn Citation2003; Cushman and Klecun Citation2006). We believe closer inspection is needed at the junctures between categories for a holistic understanding of user requirements during LCEs and look at theoretical frameworks for conceptualising these boundaries.

Murdock (Citation2002) considers users in three groups: core (interacting with technology routinely), peripheral (doing so infrequently) and excluded users who do not interact with technology at all. A less simplistic view from Lenhart et al. (Citation2003) suggests multiple groups of non-users – net evaders (benefiting from ICT through family), net dropouts (who were online but stopped), intermittent users (when they return occasionally) and the truly unconnected with complete separation (Lenhart et al. Citation2003). Finally, Wyatt (Citation2003) categorised non-users into four by considering a difference between passive avoidance and active resistance. Here, resisters are non-users who never intend to use a given technology; rejecters are those who intentionally stop; the excluded are those who cannot not get access in the first place and expelled are stopped involuntarily.

Scholars studying non-users tried to define which factors played a role in usage versus non-usage of technology. Suggestions have included a lack of skills, confidence (Nakatani et al. Citation2012), complexity of use and other demographic factors (e.g. age, gender, marital status, socio-economic status) (Wyatt, Thomas, and Terranova Citation2002; Lenhart et al. Citation2003; Selwyn Citation2003). More recent studies demonstrate that interconnected reasons and attitudes can lead to a behaviour of non-use (e.g. trust in ISPs) (Bandura Citation1994; Hargittai Citation2003; Cushman and Klecun Citation2006; van Deursen and van Dijk Citation2011; Reisdorf, Axelsson, and Söderholm Citation2012). A consistent conclusion is that complex relations exist between these elements; though most studies occurred under a utilitarian goal of turning non-users into compliant adapters. Non-users are seen as problematic users.

Satchell and Dourish (Citation2009) revamped the discussion in HCI however. They argue that non-use is not a gap or non-space. Instead, it is often, active, meaningful, motivated, considered, structured, specific, nuanced, directed and productive (Satchell and Dourish Citation2009, 15). They highlighted six varieties of non-use: lagging adoption (non-users who have not adopted yet); active resistance (non-users who steadfastly refuse a technology in active and considered ways); disenchantment (a form of reluctant or partial use); disenfranchisement (non-users forbidden from using ICT); displacement (using technology through someone else) and finally disinterested people with absolutely no curiosity.

Satchell and Dourish (Citation2009) claimed that researchers have methodological and ethical responsibility towards non-users; they are not people to be converted. Our research attempts to heed their warning of all ‘the important things we might miss if we are attempting to read all responses to technology purely as expressions of potential interest’ (Satchell and Dourish Citation2009, 15). In summary, use and non-use are not essential identity markers but subject to change throughout the life of individuals. In this study, we look at non-use during the specific life circumstances resulting from an LCE.

2.7. Research goals

The studies discussed in these sections enabled researchers to make significant progress toward an understanding of technologies amidst specific life events. To date, little comparative researchFootnote3 has focused on LCEs. We, therefore, pose our first research question: RQ1: Are there similarities between the coping strategies adopted by people who experience distinct LCEs?.

We seek to verify whether people experiencing an LCE face similar problems in seeking social support online and our second research question proposes: RQ2: What are the challenges that people who experience an LCE face when seeking social-support online?

As we have reviewed, the individuals experiencing events express similar basic needs (e.g. to recover control of the situations). What can we learn by contrasting user and non-user approaches to achieving the same ends? twoHere we intend non-users specifically as people whom, during the time period of the LCE, do not look at online services and tools as a source of support. A third research question is RQ3: How, if at all, does the behaviour of users and non-users of twoICT differ when experiencing an LCE?. Better understanding non-users behaviours and preferences could reveal improvements for technology during LCEs for any form of user. Further to this, we ask twoRQ4: How do non-users of twoICT perceive services that are specifically designed to support LCEs, relating to needs from their life events? What is there to learn by eliciting non-users reflection on technological alternatives to their coping strategies?

RQ1 and RQ2 focus on how people deal with LCEs, regardless of their usage, and RQ3 and RQ4 focuses on the distinction between users and non-user groups. They seek to improve design insights for current services, specifically for those experiencing LCEs. As we have discussed, non-users are no longer understood as subjects to ‘convert’ or ‘coerce’ into use. The intention of our research was to elicit insights from these users that might otherwise have been missed in previous research. We believe their reasoning and sensitivities possess interesting qualities; understanding their motivations or experiences can benefit the design of ICT for LCEs across the board.

3. Method

Given the pervasive effects of LCEs, we chose to conduct a field study involving semi-structured interviews with participants who recently experienced an LCE the most appropriate. This method allowed us to observe the interplay of context, individual(s) and artefacts involved for phenomenological understanding of their experiences and the meaning they gave them (Creswell and Poth N Citation2017). In two field studies, we were able to field participants across 11 different categories of LCEs described by Holmes and Rahe (Citation1967). Unfortunately, we could not recruit participants in all categories of LCEs identified in the literature review. It is customary for studies of this nature to gather around 10-20 participants after screening (e.g. 8 Moncur, Gibson, and Herron Citation2016, 19 Smith et al. Citation2012 and 10 participants Bales and Lindley Citation2013) or even with no screening at all (11 participants Odom, Zimmerman, and Forlizzi Citation2010b). We were able to analyse data across an even wider sample, with 30 participants who qualified after our screening process.Footnote4

In 2018, we conducted a study that involved people experiencing one or multiple LCEs; this was intended to elicit cross-sectional findings on the design of ICT supporting LCEs. A prior research effort, occurring in 2017, supplemented our work as it focused on people who were dismissed from work and were looking for a new job, this enabled in-depth reflections on one specific type of life-changing event. Although participants experiencing different LCEs experienced distinct challenges, a layer of similarity can be abstracted from the coping strategies they used. Our RQs were designed to compare these coping strategies – not the events or experiences relating to the LCE – and to do so over a diverse sample. We feel this is appropriate and similar methodology can be found in related work (Massimi, Dimond, and Le Dantec Citation2012; Massimi, Harper, and Sellen Citation2014).

3.1. Users and non-users of ICT experiencing LCEs (2018 field study)

This study looked for recurring aspects of design that influenced experiences with technology during an LCE. Three main questions determined study inclusion or exclusion of participants recruited using flyers in public spaces. This strategy was because non-users could have limited internet access and, for the same reason, a telephone number was also included. To qualify, the respondent had to have experienced at least one LCE in recent memory (see question A1.(1)). Second, we listed specialised or generic online services and tools they might have used and required the selection of two or more to avoid edge cases (see question A1.(2)). The screening criteria for this question required of respondents who did not use tools and

who did. The final question (see question A1.(3)) qualified answers to the second – whether the respondents found tools useful (categorised as a user) or stopped using them (categorised as non-user).

Additionally, the screener contained demographic questions and fields for interview availability. When multiple candidates were available for a given LCE, we diversified the demographic characteristics of the recruited participants on a best-effort basis. The primary screening questions are in Appendix 1.

3.1.1. Participants

We received 89 responses, of which 18 qualifying participants were recruited (8 women, 10 men). This group covered a mixture of LCEs (7 relocation, 3 diet/training, 3 relationship breakdown, 2 bereavement, 2 divorce, 2 injury/illness, 2 pregnancy/maternity, 1 unemployment, 1 child leaving home, 1 starting a new relationship, 1 marriage and 1 retirement). Of these, 8 used ISs during their LCEs (users) and 10 did not (non-users). The sample represented people at different life stages (6 participants in their mid-20s, 6 in their mid-30s, 2 in their mid-40s, 2 in their mid-50s and 1 in his mid-60s) and a good mixture of occupations (3 graduate students, 1 undergraduate student, 4 employees of large companies, 2 medical staff, 1 researcher, 1 shop assistant, 1 musician, 1 chef, 1 museum guide, 1 intern, 1 teacher and 1 retiree). Education levels of the recruited participants were also varied (5 participants completed high school, 5 completed some professional training after high school, 7 graduated from a university and finally 1 earned a doctorate) and, finally, all participants were residents in the French-speaking part of Switzerland in the region where the study occurred, Lausanne. presents a summary of the participants of the study.

Table 2. Participants demographics. Column G identifies the gender, column U identifies whether the participant was a user (U) or non-user (N) of interactive services, and column S is the study number.

3.1.2. Protocol

Participants were given semi-structured interviews in four main sections. The first focused on the use of ICT with questions to assess any behaviours or routines. Questions were designed to assess how, how frequently and why the respondent turned to solutions. The second section dealt with the LCE itself and eliciting a range of retrospective reflections on experiences and problems they might have had. The third part dealt with the social capital of the participants, to understand the network of the respondents and whether they typically sought support from peers or family members. The last section focused on online services and tools designed to support people experiencing an LCE; to understand the role they played during the LCE/s and the advantages or frustrations they experienced with technology. In this part of the interview, participants we screened as ‘non-users of ICT’ were given examples of online services and tools they might have used in the past. These examples were to provoke reactions from participants and thoughtful reflections on their design (Iacucci, Kuutti, and Ranta Citation2000; Howard et al. Citation2002). in Appendix 2 presents an excerpt of the list of online services and tools presented to the participants of the study.

3.2. ICT designed to support job-seekers (2017 field study)

The other field study focused on participants who lost their jobs or were changing careers; we partnered with the unemployment office (ORP) of the canton of Neuchatel, Switzerland, who extracted a list of participants in job transition and came from varied demographics (e.g. age, gender, education level and occupation). Potential candidates received an online screener similar to the one described earlier with questions on the tools they were using (e.g. mobile phones, social networks) and we selected a diverse sample for best effort diversity. A specific goal was understanding the relation between online and offline social support designed for job seekers.

It is important to note the data provided by this field study supplements the primary work we described earlier. This study occurred earlier and was not designed exclusively for this paper – it targeted a particular LCE. As such, the screening process was slightly different with some questions specifically focused on issues of unemployment. We asked about their availability for interviews, living situation, educational experience and technological habits/routines. We selected participants for diversity on a best-effort basis and included criteria to ensure a an even split of men and

women.

3.2.1. Participants

We sent screeners to 200 of the addresses provided, and 95 responded with interest in participating. We recruited 12 participants (6 women). Although most had lost their job, we recruited one participant changing her career and one pursuing a similar position with more responsibilities and better pay. Two had also experienced other LCEs during the six months before the study, namely divorce and a personal injury. Seven participants were regular users of IS and used job search sites; the other 5 did not use online services and tools to find new positions. In terms of ages, two participants were in their mid-20s, three in their mid-30s, three in their mid-40s, three in their mid-50s, and finally one in her 60s. The completed education levels of the recruited participants were as follows: three completed high school, three graduated from a university, and the rest completed professional training. All the Participants lived in the canton of Neuchatel, Switzerland and summarises the data presented here.

3.2.2. Protocol

Like the other field study, we conducted semi-structured interviews, this time in three parts. We began by asking about their use of technology in general before moving onto their latest period of unemployment. We asked about their situation, the support network they had and what they considered to improve their chances of being hired. In the last part of the protocol, we focused on internet technologies and services explicitly designed for job-seekers. We wanted to know whether the participants used specialised sites, whether they had a CV online, and whether they used online social networks. Similarly to the other study, those who did not use online services and tools for job seekers were shown examples to provoke reflections and discussion (see in Appendix 2).

3.3. Approach

Interviews usually took place at participants homes (though two participants preferred to meet at a neutral location) and lasted between 1.5 and 3 hours. We asked to bring tools and relevant artefacts for the discussion, making particular note of their routine and everyday environment. Relevant quotes were captured immediately during the interview using audio recording equipment. A facilitator drove the discussion and a second researcher took notes. At the beginning of the interview and for delicate questions, we reminded participants that it was acceptable if they wanted to take a break or preferred not to answer specific questions. Immediately after the interview, the facilitator and the note taker discussed the most relevant findings. Participants received the equivalent of 100 USD, and the ethical review board of the university approved both Studies 1 and 2.

3.4. Analysis of the data

Data in each study was analysed using thematic analysis (Braun and Clarke Citation2006). This method groups together experiences and anecdotes (i.e. factoids) under labels that emerge from an inductive approach of the first six transcripts. The resulting code book contains definitions we updated after analysing new interviews; we stopped when new data made no difference to the code book or definitions. As a second step, we developed overarching themes from the more granular data (patterns used to organise the results section). To ensure familiarisation of the data, the first two authors of the paper conducted the interviews, transcription and the subsequent analyses (i.e. MC and LR). As the studies occurred one year apart, each of them received separate analysis. Also, as we have noted, the number of qualifying participants may appear small in contrast to those screened but this is customary to this kind of study (Odom, Zimmerman, and Forlizzi Citation2010b; Smith et al. Citation2012; Bales and Lindley Citation2013; Moncur, Gibson, and Herron Citation2016) – in fact, the combination of our studies allowed us to analyse a much broader sample size. The combination of these results was also related to our ‘T’-shaped experimental design – the main study gave us a cross-sectional view of many types of LCE and the unemployment study data provided an opportunity for an in-depth observation into one example.

It is worth reiterating that LCE can be highly varied and these events are distinct in nature and consequence. Our objective was to observe the similarities across LCEs, specifically in the coping strategies of non-users vs. users of twoICT. In this sense, events themselves and the positive (eustress) or negative (stress) consequences were not the primary focus of our analysis.

4. Findings

We begin by describing the similarities between the coping strategies that we identified and the challenges people face when seeking social support online; then we describe the online services and tools that we observed in use during the studies; finally we look at forms of non-use of ICT during the LCE and limitations of current tools.

4.1. Five coping strategies for LCEs

The participants of our study reported how experiencing an LCE was indeed disruptive in their life routines and to their emotional status. Although different, all these events require addressing some practical issues, such as finding new information, booking appointments, solving conflicts and so on. At the same time, living through these events our participants experienced psychological distress. The participants report these feelings to be intense, especially for unanticipated LCEs (e.g. a bereavement) as opposed to anticipated or discretionary LCEs (e.g. a relocation). Despite the different scales and magnitudes of the events, participants reported facing the challenges following a discrete number of patterns that we describe next. presents the connection between these five strategies and particular LCEs, as observed in the study.

Table 3. Coping strategies identified in the field studies and connection with LCEs.

Increased Communication with Family and Friends. Beyond self-coping, participants of the studies sought information and logistical support from their significant others (when in a relationship), other family members and friends. Particularly, several participants reported seeking recommendations from their family concerning experts that could help with their LCE.Footnote5

[P2, injury, N] At first I asked [redacted] and she recommended this doctor at the university hospital who is well known. In general, I always ask my family first and then friends. If they cannot help, then I go through the doctor and other official sites. As a last resort, I check on the Internet. I value the opinion of my close family and friends more than people I do not know.

[P5, maternity, U] There is also an administrative part to manage during this period. It was a relative who told me how to deal with these issues. For example, I am not married to my boyfriend, and I wanted my daughter also to have the father's name, so I got the information through relatives.

Another dimension that was mentioned in the interviews is that family and close friends are often able to provide support that is more tailored towards the specific needs of the individual. For instance, P25. had several temporary jobs in private companies as a research assistant. However, she felt she needed a change and applied to a lab-technician position in a public hospital. She asked people in her social network that were working in the same hospital. As they shared the same background they could tell her whether she was qualified for the job. As LCEs are also a source of psychological distress, all participants sought relational support. Talking about what they were going through helped them reduce stress, get in touch with their feelings, elaborate their pain and reflect on their life. Human contact helped them reduce loneliness during the life event they were experiencing. Family and friends provided a sympathetic ear and participants felt they were cared for. Opening up with people they trusted helped them also to self-reflect and put things in perspective.

[P7, bereavement and relationship breakdown, N] The help came mostly from friends and a little less from family. For the death, it was family, and for the breakup, it was friends. Discussing with my friends I finally realised that I was not very happy in that relationship. It is really this human contact that is necessary.

In many cases, participants reported preferring to connect with people they knew face to face as this provided a richer experience and a more comforting interaction. Whenever this was not possible, participants used ICT. For instance, P18, who was retired, could exchange video-messages with his grandson living abroad. This provided the grandfather a connection with his family that helped re-establish a sense of purpose in life. In other situations, participants preferred to talk to strangers and people who were facing the same LCE. These people were not experts and also they were not people whom they have known previously (see ‘Seeking Support from Separate Networks’ later below).

Increased Communication with Experts. Participants often turned towards experts when the situation they were experiencing required specialised knowledge that they could not find within their social network. During the phases that preceded the divorce, P11 contacted a couple's counsellor. The couple was going through very rough times, discussions often exacerbated the situation. They often shouted at each other and ended in tears. The expert provided emotional containment that prevented an escalation of distress. Professionals are often required to mediate and provide support when crises escalate.

[P8, child leaving home, N] I called the Lausanne police and they did an excellent job in trying to defuse the situation. At the time, urgent action was needed so the police were empowered to deal with this kind of situation.

We found participants seeking expert support particularly around four areas: psychological (i.e. for bereavement, divorce or sentimental breakups); medical (i.e. for injury, illness, pregnancy, or for training or dietary purposes); legal (i.e. for bereavement, and divorce or separation) and for financial (i.e. for unemployment, retirement).

Seeking Support from Separate Networks. Several participants described how OSNs where they had a profile before the LCE took place exposed them to unwanted attention from peers. To counter this, some participants refrained from using social networking sites for a number of months after the event. Others, sought support from separate networks (or on the same networks using multiple accounts). Several participants recalled situations when they were pressured to react too rapidly, increasing their stress. Life events often require time to adjust. Fully experiencing this time has significant psychological benefit because it enables people to evaluate emotions and reflect. Several participants reported keeping peers and family at a distance to avoid feeling pitied or causing worry, but this could lead to inappropriate/uninformed commentary. Participants could then feel not understood, judged, or uncared for.

[P12, relationship breakdown, N] I was really in love with her. After we broke nothing made sense anymore. [ … ] For several months after we split, I did not open Facebook or Instagram because I did not want to bump into a post from her. [ … ] Some friends did not understand at all how I felt. They kept pinging me on Messenger to invite me to parties or to hang out. I just wanted to be left alone.

Another aspect that emerged from interviews is how OSNs can compromise user privacy (e.g. Facebook disclosing that a relationship has ended). Several participants reported refraining from seeking support on OSNs because the potential benefit of relational support were overshadowed by the fear of being identified. They described feelings of fragility and not wanting to explain themselves to people or appear ‘out of character’.

[P13, bereavement, N] I would have liked to chat with people of my age who also lost one of their parents. At some point I thought about Facebook to find these people but then I did not do it. (silence) I just did not want to be pitied by my friends. I experienced that after the funeral and I had enough…

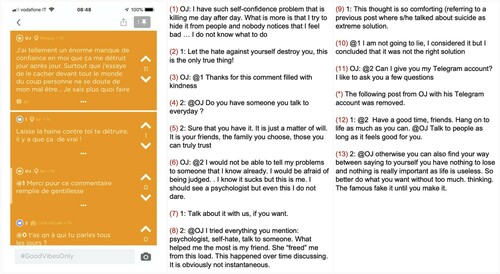

Some of the students we interviewed reported the use of anonymous forums to seek help. These enabled them to find people with relevant experience and keep their identities private. One of these systems that is extremely popular in Switzerland is called Jodel Footnote6 Users post messages to a local community and identities are kept private through a numbering system that is different in each thread, conduct forbids users from posting identifiable information and conversations are also moderated. Participants who used Jodel found it helpful for relational and enabling support.

[P5, pregnancy, U] During the pregnancy I used Jodel. I felt on an emotional rollercoaster. I had questions but I did not want my family to worry. [ … ] People on Jodel sometimes make brutal comments but they are honest most of the time because they do not gain anything lying to a person they will never meet.

Unfortunately, for practical issues, Jodel was not particularly helpful. The policies described above make it difficult to ask for directions, links, or references as moderators typically remove these. The same prevented the exchange of user names or contact details to move a conversation out of Jodel, limiting the potential for help or advice. Finally, some used hyper-local networksFootnote7 to obtain tailored support and information. Local communities provide information access that is difficult for general-purpose information systems. For instance, P10 needed new housing and applied to several student halls with no luck. After he registered on a local student-forum in Lausanne, he was able to find others seeking a flat-share.

Seeking Information Online. In addition to seeking relational support online, participants reported to regularly use the Internet as a source of knowledge that could help with their LCE. Participants accessed relevant information through institutional sites, sites managed by no-profit organisations and commercial services, forums and informative pages of various kinds (e.g. online magazines, etc.). Several participants described that finding this information offline would have been also possible. However, online resources help save time and provide more options than offline searches. Also, participants appreciated how using dedicated services (e.g. job search sites) could help automate tedious/repetitive tasks, thus reducing stress. Negatives with twoICT that our participants encountered included a design focus to keep users dependant on the service, with some services requiring users to register or create an account with the system before they could fully experience the benefits. Further to these points, the trustworthiness of a service is also an issue seen by our participants.

4.2. Online services and tools observed during the studies

During the study we observed numerous online services and tools being used by the study participants. We organised these in 12 categories and matched the observations with the LCEs for which we observed them in use (see ). In several cases, we observed participants looking for experts online using local directories or simply by running search engine queries with the type of expertise and the location (e.g. lawyer Lausanne). Several participants used specialised search engines for locating open job positions (in the case of unemployment or career change) and apartments for rent (for relocation). Next, some types of LCEs urged participants to acquire specialised legal, medical or financial knowledge. To this extent, we observed two types of services being used: online guides (e.g. for divorce, injury), and in a smaller amount of cases video tutorials (e.g. for maternity). For only one type of LCE, namely career change, we observed people using eLearning services to acquire new languages. Next, for organising weddings and for relocation we observed participants using time and task management apps. Electronic calendars were also used in other categories of LCEs, such as injury or illness, job seeking, and during pregnancy and maternity to keep track of medical exams, and job interviews. For injury or illness, pregnancy or maternity and for habit change, we observed participants using self-tracking apps to keep track of physiological parameters that participants used to self-reflect about their status and for discussing with experts (e.g. physicians, personal trainers). Finally, we identified a number of communication services and apps that participants used for almost all types of LCEs to seek relational support. The most frequent class of services are Online Social Networks (e.g. Facebook, Instagram). We also observed messaging apps being used to connect with family and friends (e.g. Whatsapp, email). Video-conferencing software (e.g. Skype) was used particularly when participants could not meet face to face with family and friends. Finally, we observed online forums to seek local or specialised knowledge from peers.

Table 4. Online services and tools observed during the studies and connection with LCEs.

Table A1. Online services and tools presented to participants during the interviews of field study 1.

4.3. Non-use of ICT during LCEs

During our analysis, we compared the attitudes of participants who referred to online services and tools during the LCE (or who specifically used ICT designed for their LCE) with those who did not refer to these services and tools. Most participants using ICT were observed to organise their lives more than the participants not using ICT by the means of more structured scheduling and activities. Technology was used to bring control over the unpredictability introduced by the LCE. For example, P4 used ChemoWave (Treatment Technology and Insights Inc Citation2020) to track personal-health data between chemotherapy sessions and manage side effects. For her wedding, P17 used iWedPlanner (iWedPlanner LLC Citation2020) to track tasks, the guest list and an overall budget. She also used Pinterest and Instagram to share pictures of wedding dresses with friends. We observed that many non-users of ICT reported less structured organisation. After the occurrence, most participants we classified as non-users improvised and made decisions day by day. Even for events that could have been predicted or expected (i.e. anticipated LCEs), they did not plan (e.g. a residential move or a divorce).

Another distinction we observed is the importance assigned to human contact. Most non-users reported to assign a higher priority to solutions relying on social interactions. With respect to ICT, several non-users expressed uncertainty about having to disclose personal or sensitive information to machinery. In their eyes, online services and tools often standardise procedures for practical issues stemming from an LCE and fail to provide the emotional support that is also needed. This need to interact with a human counterpart was also apparent in the earlier field study. Several participants struggled with job-application forms because they felt the multiple-choice questions, motivation letters and CVs were a poor representation of themselves. They found more success with face-to-face meetings that allowed them to clarify their background, explain apparent inconsistencies and answer questions.

[P29, unemployment, N] I really liked situations like the “café emplois” because it offers the possibility to have a direct contact with a HR person for example over a coffee. There you can discuss, there is physical contact. You are more than an application file. I think I could have got a job very quickly if I would have had the opportunity to discuss directly with the HR/bosses because I know that I am good at talking.

For our participants, non-use was not an absolute way of life, rather a selective attitude towards technology. Most participants that did not use ICT during the LCE had computers or smartphones but used internet services for basic tasks. They all appreciated the new forms of connection and convenience provided by these tools but cared about preserving a connection to their real-life or the ‘real world’. Several participants described concerns they had with technological solutions as a whole and how affected them (or those around them). Specifically, they mentioned privacy concerns, time-consuming aspects of use and their potential to create dependencies. Most users of ICT reported similar attitudes but valued advantages over the disadvantages.

[P12, relationship breakdown, N] I find it distressing that one is unable to live without always having one's nose in it (smartphone). Then it is the way we use it because I am happy to have one but not to watch nonsense. Actually, I often say it is like a knife. You make good food with them, but you can also kill.

[P23, unemployment, U] My evaluation is rather positive. I am a heavy user and of course there are negative aspects. Of course I use my phone sometimes while I am with people. But there are so many advantages that the disadvantages are negligible. They are more useful to society than they are harmful.

Interestingly, some of our participants reported changing their behaviour with ICT when their lives changed. Some reported becoming more cautious with using online social networks (as discussed previously). Others reported becoming more wary of investing their time and resources online.

In some cases, participants demonstrated how the boundary between use and non-use is very light, P24 found contact details of a company on a form while she was applying to a position. Instead of completing the flow as designed (using a contact button/form), she forged an alternative path and found contact details for the head of recruitment to introduce herself directly over the phone (see ). Other participants going through unemployment often spoke of this barrier too. They often expressed troubles understanding the company or the details of the position and the frustration with not being able to ask questions directly. These details were sometimes wrong or misleading, exacerbating feelings of helplessness or dis-trust in the technological approach.

Figure 1. Jodel thread on P7's mobile. The author of the post is identified with OJ (i.e. Original Jodeler and sometimes with the ID 0), and the peers who respond to the post are given a unique number for each thread (e.g. 1, 2, etc.). To reply to specific people, users use the tag ‘@’ followed by the user's number in the thread.

Figure 2. Contact details of the person responsible for a recruitment as displayed on JobUp (P24). The main call for action is highlighted in red: Postulez maintenant! (Apply now!). However, the participant chose an alternative flow and contacted the recruiter using the phone number reported on the page.

[P26, unemployment, N] If I want to learn about this or that company I prefer to speak with someone in my network who has worked there. If you look at the job offer or what is available online it would be difficult to understand whether you will be happy working there.

The next section discusses the relation of these findings to prior research and how the design approaches of twoICT for LCEs could improve for users and non-users alike.

5. Discussion

The consequences of LCEs are unpredictable and uncontrollable, which undermines the equilibrium for those involved. In order for people to find a new sense of normalcy, they may change their routines and habits (Dimond, Shehan Poole, and Yardi Citation2010). This study reveals that people experiencing an LCE have psychological needs for which they seek caring support and enabling support to reduce uncertainty and develop a sense of control. This finding corroborates many of the studies reviewed before, relating social capital to resilience during an LCE (Coleman Citation1988; Lacković-Grgin et al. Citation1996; Uchino, Cacioppo, and Kiecolt-Glaser Citation1996). We present examples of the psychological and information needs reported by our participants. Although these types of needs were already identified in prior work on specific LCEs (e.g. Wortman and Lehman Citation1985; Vetere et al. Citation2005; Massimi and Baecker Citation2011; Yamashita et al. Citation2013; Liu, Inkpen, and Pratt Citation2015; Moncur, Gibson, and Herron Citation2016), we confirm that these needs are experienced throughout a larger variety of LCEs, including retiring or graduating (or starting) school.

Furthermore, this study reveals that people experiencing LCEs seek support by using five approaches in these diverse situations: they rely on their family; they seek support from their friends, and other acquaintances; they seek expert help; they seek support through social networks separated from their main ones; and obtain support through internet technologies. People that undergo an LCE seek enabling support and recommendations coming from their social circles. This is typically taken in higher consideration than information they might find on the Internet by themselves. The reason for this preference is the level of trust participants have in the sources of support and the customisation of the recommendations they could receive from known sources. In prior research, Bakardjieva (Citation2005) describes how people who do not have Internet/computer technology expertise, often seek support from a peer in their social network (i.e. the ‘warm expert’ Bakardjieva Citation2005, 99). While in Bakardjieva (Citation2005)'s account the reason for preference is accessibility in the user's everyday life, in our account of these forms of social recommendation the preference is due to the knowledge of the user's context. In addition to enabling support, people undergoing LCEs seek relational support inside and outside their social circles. They seek relational support from within (i.e. family and friends) to feel they are cared for. They seek relational support from strangers to discuss freely with other people that have experienced similar events without compromising their social image. Through the comparison between use and non-use of ICT during LCEs we observed limitations in the current design of many online services and tools used by our participants. We organised these around three pain points.

5.1. ICT is often inattentive to the needs of people experiencing an LCE

Our findings describe the current role that internet technologies play in the lives of people experiencing LCEs: they are helpful, but they are often inattentive to the level of details or the care they required. Here the qualifier ‘inattentive’ is used to define technology that is unable to understand the specific needs these people have. The non-users interviewed in this study contributed findings to this point. In line with prior work that highlighted more nuanced reasons for not using internet technologies (Satchell and Dourish Citation2009), we found that most non-users were aware of the existence of online services and tools and possessed the skills to use them. Our participants also expressed three main reasons for steadfastly refusing these technologies: there are privacy concerns, and these technologies can be time-consuming and addictive. Concerning the first point, participants of the study reported situations where they felt coerced by online tools to log-in (i.e. reveal their identity), report their status, list their contact details, log their activities, etc. While most users would agree to disclose these aspects of their life to receive the benefits of a service, people experiencing an LCE are likely more sensitive towards their private sphere and less inclined to communicate these details. Unfortunately, most services we have observed during the study, including services explicitly designed to support LCEs, did not personalise the user experience for new customers. In fact, it would be reasonable to expect differentiated use cases for users who recently experienced an LCE (e.g. a lighter signup flow, optional logging and status reporting). Concerning the second point, we point out that the metric that is typically used to measure user's engagement, namely the user-session duration, requires to be reconsidered for users who recently experienced an LCE. In fact, the success of most online services is typically measured by their ability to keep users ‘hooked in’ and several micro-interactions are usually built to keep the users connected (see for instance the related videos that are prompted right after a user has finished watching a video). While most interactive services and products rely on a persistent model of interaction, users who went through an LCE have different priorities that are driven by a need to resolve uncertainties and traditional paradigms of interaction might feel coercive and insensitive.

A form of non-use that we observed and that we could not find in the taxonomy proposed by Satchell and Dourish (Citation2009) was a form of avoidance caused explicitly by the LCE. While previous work has sought to understand partial and reluctant use, these types of ‘non-use’ were found established in these attitudes. In contrast our research shows that these tendencies can be developed in response to life disruptions. We termed this form of non-use consequential discernment. We found three dimensions that qualify this form of non-use: a more selective attitude, a shift in priorities and a shift in concerns. People experiencing an LCE are deliberate in the way they choose what to do and where they get support, to avoid mistakes and conserve energy. Unfortunately, most online services and tools we studied do not progressively build trust with their users. Instead, they require personal or financial investment to operate adequately. Given the reflective state of some users during an LCE, they are more critical toward requests. These individuals may be experiencing a fragile state and are often attempting to protect themselves from additional stress, anxiety or uncertainty. twoConsequential discernment manifests itself as the non-use, or partial use, of internet technologies and appears at particular junctures in the life of users. The avoidance of technology is not due to the character of the non-user or the expression of a lack of social standards; rather non-use for these people is a form of protection or self-care that is indicative of how internet technology might be inattentive to the level of protection that these users need.

5.2. ICT is often imprudent and expose users during LCEs

As has been seen in prior research, the Internet and OSNs can be a great source of relational and practical support during an LCE (Lacković-Grgin et al. Citation1996; Uchino, Cacioppo, and Kiecolt-Glaser Citation1996; Meadows Citation2010; De Choudhury, Counts, and Horvitz Citation2013). Through the Internet, people can take advantage of social capital through networks, in ways and ease that would not be possible otherwise (Wortman and Lehman Citation1985; Vetere et al. Citation2005; Massimi and Baecker Citation2011; Yamashita et al. Citation2013; Liu, Inkpen, and Pratt Citation2015; Moncur, Gibson, and Herron Citation2016). They can send a request for help to several people at the same time and look into larger circles.

In addition to confirming these prior findings, our research reveal how people experiencing an LCE will often avoid seeking help on OSNs altogether to avoid exposing themselves to unwanted/unhelpful conversations. They may also be concerned about damaging their public image, something that Gibson and Hanson (Citation2013) and Toombs et al. (Citation2018) noticed with new parents. In this sense, OSNs are imprudent as their design might expose users to more sources of stress.

We found it interesting that several participants of the study circumvented the issue described above by using anonymous OSNs. Using services such as Jodel, participants were able to express themselves freely, withdraw from conversations without feeling accountable for their choices, and not fear being stigmatised by their peers. Through the study, we learned that people undergoing an LCE are fragile and may go to great lengths to protect themselves from unhelpful social contacts. twoA typical disadvantage of anonymous social networks such as Jodel is that these services enforce anonymity so effectively they limit the depth in which people can discuss their experiences or what they can exchange in support (e.g. links, phone numbers). The role of anonymity in OSNs in relation to LCEs was already reported in prior research on sexual abuse (Andalibi et al. Citation2016 Citation2018), gender transition (Haimson Citation2018) and transition into motherhood (Britton, Barkhuus, and Semaan Citation2019). This work reports the use of anonymity in a wider range of LCEs such as bereavement and sentimental breakups.

Finally, this study revealed that people who experience LCEs desire the ability to seek help from people in specific geographical communities. If they require local social services or (in the case of relocation, or being remote to a problem) and knowledge, we observed that it was challenging to find internet forums with a hyperlocal focus. The specific role of hyper locality in the context of LCEs was not identified in prior research.

5.3. ICT designed for LCEs is often inapt to support people experiencing LCEs

A final point of discussion concerns the lack of support for human connections currently available online services and tools specifically designed to support LCEs. Although they hold the potential to expand user's support circles, most online services we observed in use are often designed to mediate the relationship between users, information and professionals. Users are commonly unable to interact directly with experts and are required to fill out forms, read informational posts, and work with systems that provide support asynchronously. Our interviews collected data showing people who experience an LCE prefer direct forms of relational support with opportunities for sufficient depth in a trusted environment.

In this research, we identify this point as a factor that contributes to the frustration of non-users especially. Although previous research on LCEs identified the preference for in-depth forms of interaction (Shklovski, Kraut, and Cummings Citation2008; Lindley, Harper, and Sellen Citation2009; Smith et al. Citation2012), this study is the first to appreciate the relevance twoto ICT targeting people experiencing an LCE or the particular sensitivities of non-users.

Users of online services and tools, demonstrated thoughtfulness, tended to be organised, and mindful of details whereas the non-users disliked structure and schedules. Non-users appeared more outgoing and social and being around other people was the most likely strategy they reported to deal with their LCEs. Our non-user participants also spoke about needing kindness and affection from other people, privileging human contact over other forms of support. Communicating thoughtfully about the feelings a person experiences during an LCE requires knowing the context of interaction and the freedom to express the nuances of emotions and complexity.

We learned through the study that twoonline services and tools are often inapt to support people experiencing LCEs fully, as they most often do not allow direct forms of interaction with other people that can enable the rich forms of interaction described before. Non-users especially routinely expressed their need for more in-depth interactions with their peers who provided support, something seen previously as well (cf. Lindley, Harper, and Sellen Citation2009; Smith et al. Citation2012). In short, we learned that people experiencing an LCEs are sensitive to the design approaches of these services and the paradigms they build on. In many cases they seek fuller and richer forms of interaction that most online services and tools seem unable to provide.

6. Implications for design and policy

This research identifies common elements of frustration that stem from the design of ICT for those experiencing an LCE. Adopting new technologies is complicated, and current solutions are inattentive to the specificity of these users, and often do not allow them to find in-depth relational support from peers or experts.

We present three recommendations for ICT that highlight the importance of providing a means to protect identities and acquire relevant support. While the first two are design recommendations to online services and tools that wish to support these users specifically, the last can be considered a policy implication for all people undergoing an LCE. Our study revealed that LCEs often require forms of support that only other humans can provide. The implication is that technology should not mediate relation with other human beings, but rather expand the possibilities of people undergoing an LCE to connect with other people that can help.

6.1. Building trust progressively with users

Current design approaches to welcome, profile and retain users interferes with the value assessment that users make about continuing with an online service. In this context, users experiencing an LCE are more sensitive to relinquishing personal information or control. To grow trust progressively, services need to consider whether it is indispensable to collect participants information at all or if they could use anonymous profiles instead. Where this data or a profile is essential, the user needs to fully understand the benefits the new service will provide and any policies of data usage. An alternative would be a ‘guest mode’ where users could explore a subset of the main features to the service without needing to log on.

As an example, an online service providing information and support to retirees could provide a few case studies to describe the services provided for some satisfied customers, the sources of data and the way the service ensures data quality. Later, if the interactions between the user and the service continues, the user can be asked to create an account, to provide contact information, and possibly pay a fee. Most services offer a dichotomous experience – either they are IN or OUT – we argue that an intermediate status is more appropriate to users experiencing these difficult circumstances and may be actively defensive or protective.

In general, a guest mode moves the emphasis from blind trust to building trust. Taking decisions, even as simple as whether to sign up for an online service, can be difficult. Users who are experiencing an LCE may be encountering these services for the first time. An example of a no-login, no-installation, trial for a video-conferencing service is provided by Gruveo (Gruveo Inc Citation2020). Finally, some services may offer a money-back guarantee, but this can involve contacting a customer service representative - generating further anxiety and stress these groups are trying to avoid.

6.2. Supporting anonymity and hyper-locality

A second conclusion concerns anonymity and hyper-locality in OSNs. OSNs expose them to unwanted communications and attention from peers. Avoiding OSNs is a solution chosen by many people experiencing life-changing events. Anonymity is a property offered by some smaller services and OSNs (e.g. Whisper WhisperText LLC Citation2020), however, popular OSNs still do not feature this option (e.g. Facebook, WhatsApp). Popular networks have considerably more users that would enable interaction across members of the same locality. Recall that people experiencing an LCE often seek support from people living in the same geographical region and who can provide information specific to local norms, cultures and contexts. Our study found that these two properties (anonymity and hyper locality) are equally useful in supporting users experiencing LCEs. We suggest that people experiencing an LCE can benefit from OSNs that specifically allow users to interact under a pseudonym alongside the possibility to target local communities.

During the interviews, we identified an app that implements this concept, namely Jodel. However, it fails to fully support the scenario described because usage guidelines (and moderation) forbid users revealing their real identity or exchanging of contact information. Another that does support the properties described is Dolo.Footnote8 This OSN enables users to begin anonymously, but later reveal themselves with selected peers if they wish to do so. Unfortunately, we did not see this app in use by participants. The number of OSNs that provide access to both features is still small and most existing solutions support only one of the two. Utility often depends on the broader adoption of a service/network.

6.3. Enabling relational support through rich and synchronous communication

Online services and tools that aim at supporting LCEs should provide means for users to connect directly to experts who provide practical support. Most of the services we reviewed were designed to mediate interactions and often rely on asynchronous communication or knowledge banks.Footnote9 These solutions fail to enable the relational support desired by people experiencing an LCE adequately. Providing the conditions for experts to render relational support would allow the user to use their social skills to communicate more clearly and feel more understood.

Particularly for those with rare conditions, online services and tools may be one of the most effective ways to connect people affected by them and experts working toward solutions. We imagine that, rather than just offering digital content and information, existing portals spreading information about conditions would be an ideal hub to book a video-conference with experts who can answer specific questions or provide recommendations within context. We propose the idea that ICT aiming to support people experiencing LCEs must provide this option to their users, especially when video-conferencing solutions (e.g. Skype, Zoom) are already prevalent.

7. Limitations

Our field studies spanned several categories of life-changing events. To obtain a diverse set of these events, we used a standard definition for LCEs, but broader definitions vary between individuals and cultures. Sample sizes may appear small but are customary to field studies we detailed earlier (Odom, Zimmerman, and Forlizzi Citation2010b; Smith et al. Citation2012; Bales and Lindley Citation2013; Moncur, Gibson, and Herron Citation2016).

All our participants lived in the French-speaking part of Switzerland for many years and were either Swiss by birth or naturalised citizens. Therefore, we believe our findings generalise well to the French-speaking cantons of Switzerland. However, people living in other countries and cultures might hold different sets of attitudes.

We chose participants within a 6 month of an LCE to facilitate recall, but earlier events could have revealed variance in their concerns. Memories of lived events might change over time and what seemed problematic at the time of the event, might not be highlighted as complex after some time has passed.

Finally, the findings we discuss were drawn from two separate studies – one conducted exclusively for this research, another that provided supplementary data within a specific LCE (unemployment). As such, we have elaborated on the contributions of this other study but some aspects (e.g. particular screener questions) were so specific to that context they did not warrant detail in this paper.

8. Conclusion