ABSTRACT

Previous research has established that leaders in information and communication technology (ICT) are crucial for establishing a user-centred systems design perspective in ICT for work-related tasks. This paper therefore describes the perspectives of 18 ICT leaders in three kinds of leadership roles (managers, project leaders and specialists) in order to understand their views of user-centred systems design concerning ICT. It uses the concept of technological frames of reference to analyse three domains: technology-in-use, technology strategy and nature of technology. The results show that many specialists see user involvement as a critical factor in successfully establishing new information and communication technologies, but that these systems are currently built around the needs of management rather than end users. Looking forward, all three relevant social groups are optimistic about how ICT will become more user-centred and more strategically aligned in the future. However, changes in ICT are described as extremely energy-consuming and difficult – akin to ‘walking in the jungle with a machete’. Finally, we discuss the relevance of technological frames and present some implications for the successful establishment of user-centred system design as a perspective in organisations.

1. Introduction

Leaders, organisational decision-makers and implementers play an important role in successful local and enterprise-wide ICT adoptions (Van Wart et al. Citation2017). Research has shown that successful adoptions of ICT systems rely on ICT leaders and their readiness and sense-making when understanding user-centred design in concerning ICT, and involving end users in the adoption of new ICT systems (Eriksson Citation2013). In order to do so, they need to understand the user and the user's perspective, as week as to create a good user experience (UX) (Kaasinen et al. Citation2015). ICT leaders here refers to people in ICT-related management positions in organisations, and includes managers, project leaders and specialists.

User-centred systems design (UCSD) is a process and a set of values that emphasises usability and the user experience throughout the whole development, use and maintenance lifecycle of ICT systems (Gulliksen et al. Citation2003). The aim of UCSD is to develop usable systems by understanding users and the context of use (usually through field studies and observations), turning the requirements of this process into designs and evaluating these designs with users in mind, all according to a predefined iterative and incremental participatory process (Gulliksen et al. Citation2003). The process also focusses on how users experience ICT systems when using them, and how ICT systems are maintained. UCSD is a process focussed on delivering the highest possible level of usability, a trait defined as ‘[t]he extent to which a product, system or service can be used by specified users to achieve specified goals with effectiveness, efficiency and satisfaction in a specified context of use’ (ISO Citation2019).

In this study, perspectives on user-centred system design in concerning ICT includes understanding users’ needs for ICT (ISO Citation2019). Hence, ICT leaders and their framing of ICT is crucial, especially concerning user-centred design, and is of significant interest for the successful adoption of ICT. Previous research has highlighted the importance of support from management when integrating user-centred design in organisations (Gulliksen et al. Citation2009). One of the four primary criteria for successful ICT development projects is the involvement of users in the project, as this helps project members to gain an understanding for their users’ perspective (Hastie and Wojewoda Citation2015). Many user-centred design methods are used to develop software from the user's perspective (Jia, Larusdottir, and Cajander Citation2012), but users are less commonly included as part of the process of deploying new ICT systems (Cajander, Larusdottir, and Gulliksen Citation2013; Jia, Larusdottir, and Cajander Citation2012). Orlikowski and Gash (Citation1994) propose technological frames as a systematic approach to understand the underlying assumptions, expectations and knowledge that people have about technology. This approach offers an analytic framework that can help explain ICT leaders’ views about what it means to be ‘user centred’.

A recent literature review on leadership in the digital age shows a need for more studies that go beyond traditional leadership theories in order to make sense of how ICT leaders might respond to ICT-related change (Cortellazzo, Bruni, and Zampieri Citation2019). This paper helps fill this research gap by providing insights into the technological frames that ICT leaders hold concerning UCSD. To our knowledge, this is the first study that aims at an in-depth understanding of ICT leaders and how they think about UCSD and ICT development in their organisations. Also, few previous studies have used the concept of technological frames to understand ICT leaders. Moreover, the current body of research related to UCSD and organisations focuses on the implementation of UCSD in organisations and its different effects or outcomes, such as Cajander (Citation2010), Eriksson (Citation2013) and Iivari and Abrahamsson (Citation2002). This paper extends this body of research by focusing on the perspectives of managers at organisations that have not yet implemented UCSD, an approach that offers valuable feedback for future implementation efforts.

We applied technological frames as a framework to identify and compare the frames of that ICT leaders within an organisation. We do so for all the technologies that are used within the organisation, and not related to one specific technology. The paper analyses three different technological frames (Orlikowski and Gash Citation1994) used by 18 participating ICT managers, project leaders and experts: technology-in-use, technological strategy and the nature of technology. This analysis seeks to address the following research question: what are the technological frames of ICT leaders related to User-Centred System Design in their organisations?

2. Theory

2.1. Technological frames

Orlikowski and Gash (Citation1994) introduced technological frames of reference (TFR) as a means to introduce socio-cognitive reasoning into the field of information technology research. In this study we adhere to their definition of technological frames as ‘structures or mental models that are held by individuals’ that are also ‘assumed to be shared by several individuals when there is a significant overlap of cognitive categories and content’. In this study, the concept of technology is thus understood in a broad sense as ‘not only the nature and role of the technology itself, but the specific conditions, applications, and consequences of that technology in particular contexts’ (178). In their definition, which we are using here, technological frames concern assumptions, expectations and knowledge that people use to understand technology.

Several studies have adopted the TFR theory (Davidson Citation2006), and fellow researchers have discussed its limitations and proposed possible extensions to Orlikowski and Gash's work (Davidson and Pai Citation2004), see also (Bartis Citation2007 for a comment). Iivari and Abrahamsson studied the implementation of user-centred design in an IT company and used the concept of technological frames to analyse the outcome (Iivari and Abrahamsson Citation2002). Recent studies have employed this concept to contrast the differing perspectives of stakeholders (Grünloh Citation2018).

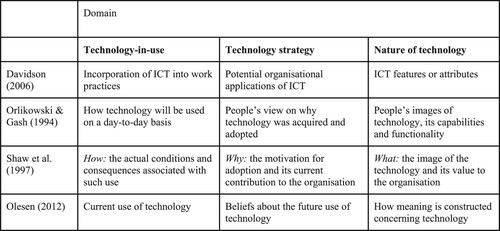

In their original study (on which we base this study), Orlikowski and Gash (Citation1994) identify three general domains of technological frames: the nature-of-technology – what the technology is; technology-in-use – how it is used to create various changes in work; and technology strategy – why it was introduced. They also suggest that these domains should be the starting point of the analysis and that other domains might be possible. Davidson (Citation2006) has analysed the domains used in other studies; although these studies may you different sets of names, he argues that most have characteristics similar to the original. below lays out our summary of the definition of the domains of technological frames drawn from four studies.

Figure 1. Alternate definitions of the three domains originally proposed by Orlikowski and Gash (Citation1994).

From we can see that the definitions of domains vary between different studies. For example, Orlikowski and Gash (Citation1994) understand technology strategy as views on why technology was adopted, Shaw, Lee-Partridge, and Ang (Citation1997) use it, in part, to refer to technology's current contribution to the organisation, and Davidson (Citation2006) sees it as pertaining to potential applications. We

In our study, the definition of technology also includes the socio-technological changes that follow the evolution of the digital workplace. Moreover, we define technology-in-use as including how users are involved in ICT design processes and work-process development, as well as organisational support. This perspective draws on the concept of human-work interaction design (Clemmensen et al. Citation2006).

In this paper we define the domains of the technological frames as follows:

Technology-in-Use: How technology is used like suggested by Olsen (2012), including the short-term/practical perspective on ICT and related changes to organisational work practices like suggested by Shaw, Lee-Partridge, and Ang (Citation1997). We also include the aspect from Orlikowski and Gash (Citation1994) on how the technology will be used by analysing how users are involved in the design process, as recommended in UCSD, and the organisational support.

Technology Strategy: Why technology was introduced like suggested by Orlikowski and Gash (Citation1994) and Shaw, Lee-Partridge, and Ang (Citation1997), including the long-term/strategic perspective on ICT from Olsen (2012) and related changes to work practices from Davidson (Citation2006).

Nature of Technology: What the technology is like suggested by Shaw, Lee-Partridge, and Ang (Citation1997): the images of technology and its capabilities and functionality like suggested by Orlikowski and Gash (Citation1994).

Orlikowski and Gash (Citation1994) further propose that the concept should be used to study the congruence or incongruence of frames across different relevant social groups (such as developers and users) or within the same group. Correspondingly, in this study we discuss the congruence and incongruence of ICT leaders’ technological frames. Other studies, such as Olesen, have stressed the importance of dominating frames, such as those held by senior management.

2.2. ICT and leadership

Many fields of research have looked at leadership and ICT, including educational science (Petersen Citation2014), caring sciences (Willmer Citation2007), and informatics (Van Wart et al. Citation2017). However, a recent literature review (Cortellazzo, Bruni, and Zampieri Citation2019) concludes that the contributions have accumulated in a fragmented manner across these various disciplines; the reviewers conclude that more research is needed outside the traditional field of research on leadership theory. This study fills this research gap and is not based on traditional research on leadership theory.

The field of human–computer interaction (HCI) began to investigate ICT leadership started at the beginning of the twenty-first century. This body of literature has described ICT leaders’ perspectives regarding user-centred design (UCD), and many researchers have also presented success cases and problems encountered when integrating user-centred design in organisations (Eriksson Citation2013; Eriksson and Swartling Citation2012; Kashfi, Feldt, and Nilsson Citation2019).

Eriksson (Citation2013) discusses how user-centred design can be introduced in organisations. She concludes that as a practice, user-centred design is constituted through recurrent, situated actions that are difficult to transfer across organisations, because whatever works in one situation in one organisation may be impossible in another organisation. Eriksson and Swartling (Citation2012) studied the implementation of UCD in Sweden's military defence organisations. They conclude that successful implementation of UCD in an organisation requires three elements: (1) explicit, widely communicated support for UCD in the organisation; (2) a local infrastructure with professionals with competence in usability and the use of well defined UCD methods; (3) activities where the UCD process is tested out and exemplified. Additionally, they conclude that the successful implementation of UCD requires support from the organisation's ICT leaders.

Kashfi, Feldt, and Nilsson (Citation2019) describe a case study of the integration of UX principles and practices into a large software development company. They studied the influencing events through interviews, archival data analysis, workshops and observations over a period of two years. They gathered data from participants in a wide variety of roles, including managers, product owners, software developers and specialists. Their main results show that UX integration – like other organisational changes – can include a mixture of planned and emergent initiatives and is influenced by various intertwined events: not only those that are internal to an organisation but also those external to it. Additionally, they found that one of the pitfalls in the integration of UX was a failure to discuss the differences and implications of usability and UX as concepts during the transition and to disseminate them among internal stakeholders in order to raise awareness and get support among the various stakeholders.

The findings of these studies show how the practice of user-centred design can be introduced in organisations, especially for software development. One problem these studies encountered is that usability is often seen as a vague concept that is difficult to understand and adopt, a problem that Cajander, Gulliksen, and Boivie (Citation2006) also mention. None of these studies uses technological frames as a tool for analysis. In this paper we use technological frames to extend our understanding of how managers, project leaders and specialists think about their organisations’ current technology-in-use, technology strategy and the nature of technology.

Studies of inertia and socio-technical systems also offer relevant research related to leadership. The long-term stability of an organisation, which is a kind of inertia, can be described as a result of how networks of dependencies are created that embed and stabilise certain technologies or institutional arrangements: for example, through legal contracts, financial investments, social rituals and regulations (Geels Citation2005). This stability – which we colloquially refer to as inertia – can be identified on many different levels of society, from the global and inter-organisational to the local and intra-organisational. In many cases, this stability's conserving effect is considered positive. But inertia can also hamper development and prolong the survival of ‘unfit’ technologies: sometimes intentionally, as a means to further political agendas (Walker Citation2000). A similar effect of and deliberate use for inertia can be achieved on an organisational level (Lind Citation2017), and organisations have much to gain from mapping out the factors that contribute to inertia and their interdependence when assessing project feasibility and estimating the resources required to reshape the organisation. In organisations with strong inertia, effective leadership can, of course, be quite challenging.

This paper contributes to the limited body of knowledge concerning the relationship between ICT leadership and UCSD. Most existing studies focus on the development work required to change specific systems and implement UCSD. To our knowledge, ours is the first study aiming at an in-depth understanding of ICT leaders and the way they think about UCSD values and methods and ICT development in their organisation. Also, none of the studies we found use the technological frames concept to understand ICT leaders.

3. The case organisation

This study examines an organisation with more than 6,000 employees and is the first component in a longitudinal collaboration between the researchers and the organisation. Each department of the organisation, such as human resources or finance, controlled their respective processes, as well as their respective enterprise information systems, and integration between departments was limited. The organisation's large in-house IT department (100+ employees) mainly employed technicians and systems administrators who were responsible for supporting the basic ICT infrastructure, as well as a large team of developers and project leaders working on legacy systems, internal and external web services and new system implementation. Also, the organisation had a separate ICT strategy department, which in theory supported the IT department with strategic planning. The idea behind this organisational solution was to create a client/contractor relationship between the two departments.

The organisation's ICT infrastructure was a mix of standard desktop applications and a considerable number of enterprise information systems (EIS), including legacy systems. As administrative tasks were increasingly delegated to individual employees – including both generic tasks such as simple accounting and more business-specific tasks – almost all employees became users of the EIS on an irregular basis. In contrast, administrative staff in the business units were daily users. As most of the systems had some usability issues – not least of which were those about to limited integration among them – there had been substantial internal critique regarding the implementation of many of these systems.

There was no clear chain of command for ICT management. Perhaps the most striking aspect of this was the fact that the organisation lacked a Chief Information Officer (CIO). Additionally, the organisation's hierarchy was such that senior ICT leaders were not members of the board of directors, although they were part of middle management. This fact undermined the client/contractor idea between the IT department and the ICT strategy department, as their respective managers were on the same hierarchical level and reported to the managing director. To further complicate matters, the organisation had a separate advisory board for ICT led by a senior advisor who reported directly to the CEO. Finally, there was a separate ‘New Media’ department that had a high profile in internal discussions about ICT. As noted, other departments, such as HR, were also in full control of their respective EISs.

Although the particulars of this situation were unique to the organisation, other organisations likely face similar situations, at least temporarily, as a consequence of mergers and acquisitions.

At the time of the study, the managing director had launched a strategic change programme that encompassed several ICT-related projects, as well as the implementation of an ICT governance model that was supposed to improve daily operations and facilitate communication and coordination across the borders of the functional division (Nordström Citation2005).

4. Methods

In this section we describe the participants in the study, the methods used for data collection and the qualitative analysis of the data, incorporating the concept of technological frames of reference.

4.1. Participants

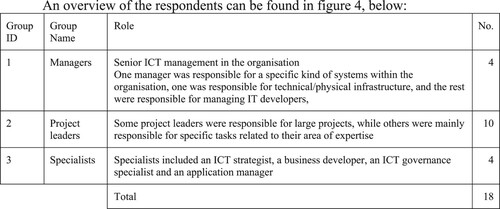

The organisation identified the 18 participating ICT leaders as instrumental to its work in ICT; they included middle and line managers, project leaders and specialists with a strong influence on the organisation's general ICT development. A purposive sampling of the interviewees was performed in the organisation with the intent of including willing participants who covered a range of experiences with projects of varying size and strategic importance and who were involved with different parts of the organisation working with ICT (Bryman Citation2008, 415). We divided the interviewees into three groups based on their roles and responsibilities: managers, project leaders, and specialists.

An overview of the respondents can be found in , below:

Managers (1) represented the organisation's senior ICT management. Among the project leaders (2), one group was responsible for large projects, while another was mainly responsible for specific tasks related to their area of expertise but were defined by the organisation as project leaders. The specialists (3) included an ICT strategist, a business developer, an ICT governance specialist and an application manager (a specialist role within the ICT governance organisation).

4.2. The interviews

The researchers conducted semi-structured interviews with the 18 respondents in order to gain insight into the organisation's processes and perspectives on user-centred design concerning ICT. We chose the semi-structured method because it lends structure to the interviews and makes it easier to compare responses while still providing enough flexibility to delve deeper into participants’ perspectives on user-centred design concerning ICT and gain a more nuanced understanding of this topic (Braun and Clarke Citation2013). For example, the semi-structured interview approach enabled us to add questions on specific topics most closely related to the respondent's knowledge and experience.

The topics prepared for the interview script included questions that sought to gather data on ICT leaders’ views of issues related to user-centred design, such as ICT strategies and long-term goals, alignment between ICT and the business, existing ICT infrastructure and ICT procurement. The interviews also covered issues related to ICT development, such as current system development processes, methods and practices, user-centred processes and perceived future challenges.

Two researchers were present for the majority of the interviews, although in a few cases only one researcher conducted the interview. Each interview lasted approximately one hour. The researchers took notes and digitally recorded the interviews. The recordings were later transcribed verbatim and the transcripts imported into the atlas.ti software for thematic analysis (Braun and Clarke Citation2013). After the study, the results were presented and discussed at a full-day workshop that was attended by most of the respondents, as well as other ICT leaders in the organisation.

The interviews were conducted in 2011 as a part of a research project, where a research group of Human–Computer Interaction and the administration of the organisation collaborated. The case was briefly described in a short none peer-reviewed conference paper in 2015 (Cajander, Nauwerck, and Lind Citation2015). Even though the data can be seen as old, we belief that the contribution of using the analysis method used in this paper, the technological frames, can be of value to the readers. The context of the interviews is a very traditional government organition that changes very slowly. We would be surpriced if thing are different today, related to establishing a user-centred systems design perspective in ICT for work-related tasks.

4.3. Data analysis

To analyse the data, we first identified topics relating to the interview questions or additional topics brought up by the respondents. These identified topics were then iteratively clustered into thematic categories. This approach was complemented by reading and manually tagging the interviews. Finally, the thematic categories were used as a basis to identify the respondents’ technological frames, following the recommendations by Orlikowski and Gash (Citation1994), who suggest that researchers should start by analysing material concerning the three generic domains, and if necessary, elaborate by defining additional domains.

The quotes used here have been translated into English, and in a few instances they have been edited for readability. The quotes have been attributed to the aggregated respondent groups rather than to individual respondents.

5. Results

In the following section we present the results of the analysis, organised according to the three domains of the technological frames of reference concerning UCSD – technology-in-use, technology strategy, and nature of technology – including relevant quotes from the interviewed ICT leaders.

5.1. Results related to the technology-in-use domain

The technology-in-use domain concerns how ICT is integrated into the organisation's work practices. In particular, we analysed how the ICT leaders’ frame of reference in the technology-in-use domain relates to the UCSD process and its values.

5.1.1. Specialists

Many specialists noted that they have no formal influence on the development priorities that affect technology-in-use: for example, they cannot control what user-centred systems design (UCSD) methods are used or how users are involved. Specialists rely on networking and other means of influencing decisions, such as trying to be involved in different projects and working groups.

Many of the specialists saw user involvement as a critical factor for the successful implementation of new ICT, because when users are involved in the process, they feel they can influence the process and know what will happen:

There is no such thing as a successful IT project. There are only more- or less-failed projects. A successful project is when people feel involved in the change and know what will happen. (specialist)

5.1.2. Managers

Similar to the specialists, some managers commented on their lack of influence, even though this group did, in fact, have some formal authority. Nearly all managers reported that they themselves had to make a personal effort to drive change in ICT and embrace the principles of user-centred systems design, and some said that it was not worth the effort. They gave examples where they have abandoned ideas in ICT due to user resistance and organisational inertia.

Other managers described themselves as explorers concerning ICT and change, framing the ICT organisation as a jungle. One interviewed described efforts to change how the organisation works with ICT-related issues as follows:

I think that working with IT has been like walking in the jungle with a machete. We have had senior management who think that IT change is only a matter of technical issues. (Manager)

This manager also complained that many senior managers think that implementing new ICT systems is a matter of technological change and have little understanding that it also entails establishing new work practices and have no understanding of the values of UCSD.

Compared to specialists, managers seldom commented on processes and technology-in-use in their interviews. However, one department manager stated that his department was the only group that is process-oriented in its work. By this, he meant that his department collaborates across organisational borders, and hence it is more in harmony with the philosophy of user-centred systems design by including users from other departments in the organisation.

5.1.3. Project leaders

Many project leaders stated that they are working on involving users in their projects – for example, through various user groups – but at the same time they admitted that the actual impact of this user involvement is limited. Some rationalised less-systematic user involvement as necessary in order to not disturb end users in their daily work. Moreover, some encountered problems such as users who don't speak up about concerns and report that sometimes the user suggestions are not actually taken into consideration afterwards. At the same time, one project leader noted that users are generally more competent using ICT today than just a few years ago. As a consequence, users have enough experience to demand systems with enhanced capabilities, but these demands developers and software companies may not fully understand these demands. Another project leader remarked that users often do not receive enough training before they are expected to work with new systems, but users nevertheless try to do their best:

Change is hampered because the employees run around ‘carrying their new bikes on their backs’, without having had time to learn how to [actually] ride a bike. But they’re like, ‘No problem; I’ll just run a little faster. I can carry one more bike if needed.’ (project leader)

Most project leaders indicated that process development was central to them, but they were less likely to mention organisational-level processes discussed by the specialists and more likely to comment on optimising local workflows connected to the specific ICT system they worked with most. Sometimes systems are built in ways that neither support organisational processes nor meet user needs, and thus the system is implemented without a target recipient or owner in the organisation. The result is that good intentions for change are lost, and the only outcome of a project is the new ICT system – one sign that change is being driven by the technology itself, however unsuccessful. Project leaders therefore express two very different views on ICT and organisational change. One is that ICT implementation drives change, and the other is that since organisational inertia is usually underestimated, the organisation fails to achieve the change that the project envisioned, and instead the only visible result is the new ICT system.

Many of the project leaders also mentioned the organisation's limited experience and understanding of project management models, such as Prince II, or approaches such as UCSD. In particular, project leaders mentioned that managers at different levels had limited experience using such models. Some project leaders also noted that such models receive limited support from managers. One project leader even used the word abandoned to describe the situation. As a consequence, several project leaders mentioned informal channels – such as networking and knowing the right people – as success factors for change. One respondent described how the project group had to use alternative approaches rather than asking for permission from management to impose a change; one such approach was to talk to the affected staff members directly, something the project leader referred to as ‘guerrilla tactics’.

5.1.4. Main contribution from the analysis of the technology-in-use domain

Project leaders believed that software developers are unaware of users’ changing demands resulting from new and innovative technology. This signals that the organisation has not used UCSD methods.

Many specialists saw user involvement as a critical success factor when establishing new ICT, since involved users feel that they have influence on the process and know what will happen. However, users are generally not involved in system development, and specialists claim that systems are built around the needs of management and not the primary users.

Managers described driving change in ICT as very demanding, mainly due to considerable user resistance and organisational inertia. One manager envisioned his work with ICT as crossing organisational borders and involving people from throughout the organisation interpreted this as adhering to user-centred system design. The manager commented that other managers did not have this kind of user-centred system design perspective.

Project leaders said that the user-centred systems design principle of user involvement was followed and that users were involved through various user groups attached to the projects, but their involvement was rather limited. Some describe change processes as tiresome and energy-consuming. Project leaders commented that the people working with ICT development are not used to approaches such as UCD.

Project leaders noted that some systems are built but seldom used. This situation might occur when the development team lacks a UCSD perspective and proceeds to develop a system that supports neither users nor organisational processes. According to some project leaders, the only visible result is a computer system that no one uses.

Project leaders said that models for development, maintenance, testing etc. are not used in practice, nor are models related to user-centred systems design.

5.2. Results related to the technology strategy domain

Technology strategy focusses on the organisation's long-term strategies. Important themes in the interviews include a critique of past strategies and solutions and a wish for a more-consolidated and pronounced ICT strategy in the future. Many respondents saw the ICT governance model as an important step towards consolidation. Yet some noted some incongruences, perhaps most notably among managers, who seem to differ in terms of what they felt was the proper ICT leadership model for the organisation. Some appreciated UCSD ideas and values, but others believe strongly in other solutions.

5.2.1. Specialists

Some specialists explicitly commented that little business rationale or thought went into the organisation's ICT-related decisions. Some claimed that decisions were often based solely on interest in deploying new technology and were not based on users’ values – a core value in user-centred systems design. For example, one specialist remarked, ‘Many decisions have their starting point in IT and the IT systems, and in people who want to try something new and have the money to do so.’

According to UCSD principles, decisions regarding new IT systems should preferably be based on user needs and not on the mere fact that a new IT system technology is available, along with the funds to pay for it.

Many respondents criticised past decisions in general, and in particular the lack of a clear chain of command regarding ICT decisions and the absence of strategic documents:

Because there is no governance or direction: This is what we are going to do and why. That is lacking. And then what happens is that what did not work previously, you do again. (specialist)

5.2.2. Managers

Some managers argued that technology specialists such as programmers had driven ICT development, while others believed that development is business-driven by the organisation's managerial employees. None of the managers believed that users needs drove ICT development. One manager mirrored the view of some of the specialists, claiming that systems were more or less ‘just downloaded from the internet’ without any real business case supporting such decisions. Managers also criticised senior managers and their priorities. One critique relates to senior management's priorities: more specifically, which projects actually received funding and managerial support. Another source of critique concerned senior management's interventions in the sourcing of human resources, which directly interfered with managers’ control over their staff. Most managers had strong hopes for a new strategic ICT leadership, including the formulation of strategic ICT plans. Some managers were very positive towards the ICT governance model and viewed it as critical to structuring the organisation's ICT, whiles others were more than sceptical and questioned the whole idea.

A different but related theme concerns the competence of various actors. End users were sometimes seen as having limited competence when it comes to articulating their own needs, as well as a limited understanding of the necessities of information systems design. One interviewee pointed to the problem of a lack of competence in the area of project management and working according to UCSD principles, in which user needs are central. As this bluntly put it:

There is incompetence … . There have been lots of incompetent people, incompetent to manage projects as well as to capture user needs. Overall, there has been incompetence. (manager)

5.2.3. Project leaders

Project leaders viewed the ICT governance model discussed above as something positive, although some argued that the model calls for much more radical change than perhaps was expected. In this, some of the project leaders did seem to present a much more nuanced argument than, for example, some of the managers. Indeed, some project leaders also experienced a limited understanding among managers when it came to the various project and governance models.

5.2.4. Main contribution from the analysis of the technology strategy domain

Many of the specialists claimed that decisions related to ICT were often based on an interest in new technology and not on their value for users. None of the managers believed that new ICT was introduced in response to identified user needs, as emphasised in UCSD.

All three categories of ICT leaders expressed strong optimism about the future. Managers and specialists looked forward to stronger leadership in the area of ICT, including strategic plans for the organisation. They were critical of the old way of working with ICT and believe that the new way has strong potential. Some also wished for a stronger user focus.

Some managers expressed doubts about users’ ability to articulate their own needs.

5.3. Results related to nature of technology

Nature of technology focuses on technology per se and views concerning both its potential and its shortcomings, especially concerning usability – one of the core concepts in UCSD.

5.3.1. Specialists

When discussing existing systems and their usability, specialists debated the pros and cons of procuring packaged software versus building on open-source solutions. Arguments for the procurement of packaged software include its lower maintenance needs and cost, while arguments for building on open-source software include better usability and cost efficiency. There are clear sides in this debate, and respondents disagreed on arguments such as cost efficiency, with both sides arguing that their approach offers the best advantage. However, there is a middle ground, in that both sides understand that ICT systems have to be adapted to both the organisation's and the users’ needs.

5.3.2. Managers

Managers acknowledged existing problems with usability – perhaps especially with legacy systems – but they also noted that these systems have been around and have evolved and adapted to unforeseen circumstances for many years and that usability problems might therefore be expected.

One manager noted that there might have been a limited understanding of the importance of the back-end systems used by staff within the organisation. The focus has been on customer-facing systems, although these are dependent on the quality of the back-end systems. There is little awareness that the usability of back-end systems affects the quality of customer-facing systems.

One manager reflected on how the ICT landscape has changed and how this creates a new reality that not all actors have adapted to:

A system owner is not as much their own master today compared to ten years ago. They cannot decide about the development of their own systems anymore, because they exist within a context, within an environment that they need to adapt to. I think that people are still unaccustomed to that situation. (manager)

5.3.3. Project leaders

Project leaders mainly discussed the challenges they face in their projects. These relate to the systems that are being introduced, which have some problems, as well as to the current diversified client system environment. The latter makes implementation and testing harder, since what works on one client system setting might not work on another.

Project leaders frequently commented on usability, and many described ergonomic or aesthetic issues in existing systems. However, project leaders were generally very positive regarding the systems that were being introduced through their respective projects, including their usability. This is interesting, since most users are reportedly not satisfied with the very same systems.

5.3.4. Main contribution from the analysis of the nature of technology domain

Specialists stated that ICT systems need to be adapted to both the organisation's and user needs.

There has been a focus on customer-facing systems, which has led to problems, since very little emphasis has been put on the usability of systems used within the organisation.

One manager claimed that the problem with ICT development is also caused by the complexities of ICT within the organisation, which has numerous ICT systems that are (or should be) integrated. The entire work situation of users and the context of the usage of all ICT systems need to be taken into consideration when bringing new ICT systems on line.

Most project leaders were positive about the usability of systems they introduced in their projects, while most users were not.

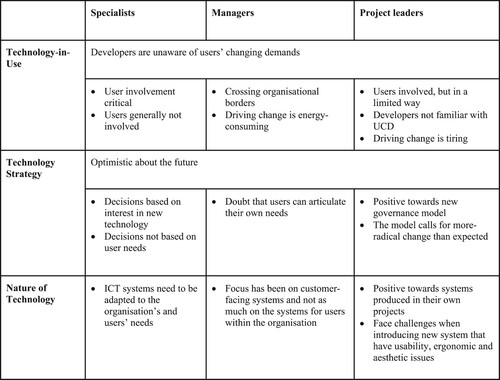

5.4. Summary of main contributions

As can be seen in , all of the relevant groups were positive about the future and believed that the new ICT systems would be better than the older ones. All three groups commented that developers were unaware of users’ changing demands.

Figure 3. Summary of results from ICT leaders on user-centred perspectives analysed through technological frames.

Specialists are positive towards integrating a user-centred design perspective but believe that users are generally not involved. They believe that decisions about new ICT systems are not based on user needs but are more often based on interest in getting new technology. Specialists point out that ICT systems need to be adapted to both the organisation's needs and user needs.

Managers believe that driving change is energy consuming, and they are sceptical of how good users really are at communicating their needs. As with other ICT leaders, they are positive that IT systems will be better in the future, even though they all believe that the developers are unaware of how users’ demands for the systems they use in their jobs change along with advancement in new technologies in general, such as the rise of mobile technologies and the incorporation of advanced technologies in people's homes.

Project leaders believe that the degree of user involvement is too limited and would like users to be more thoroughly involved. The main explanation they provide for the present situation is that developers do not know how to include users. Project leaders believe that they face several challenging issues in their jobs, such as introducing new systems that score high marks for usability, ergonomics and aesthetics while at the same time meeting the demands of different work settings. This makes implementation and testing harder, since what works in one setting might not work in another.

6. Discussion

In summary, the views of project leaders generally reflected their concern with the situation of their projects at the current time, and although they touched on more strategic issues, they seldom discussed such issues in greater detail. In contrast, managers held stronger views related to technology strategies for the future. Many of the managers’ comments thus related to ICT organisation and management. This difference in perspectives might, of course, correlate to the two groups’ different roles and responsibilities, in that managers are responsible for the overall strategic perspectives while project managers are responsible for their individual projects. Specialists had opinions on processes, methodologies and structures and how to improve them, something that is also closely connected to their formal responsibilities.

6.1. Discussion of ICT leadership

As noted above, the three analytical groups seemed to focus on different things, yet there were no strong incongruences among them. In contrast to our results, Olesen (Citation2014) identified managers; technological frames as dominant and as influential on other groups’ viewpoints. The three groups our study examined were probably too similar for such patterns to occur. Maybe more incongruence would have emerged if the study had included, for example, end users or senior managers. Similar to Olesen, though, we did find that the nature-of-technology domain became less relevant compared to the technology-in-use and technology strategy domains. This is because the respondents were not asked to reflect on one particular system but rather to discuss the development of workplace ICT in more general terms.

Given the fact that senior management had initiated several projects, it is quite possible that such senior managers would have a different understanding of the nature of technology compared to other actors in general and middle management. These results indicate that ICT leaders describe the complexities of UCSD and IT concerning their formal role, a finding that corroborates the work of Cajander, Gulliksen, and Boivie (Citation2006). The difference between Cajander et al.'s study and ours is that we focused on UCSD, while Cajander et al. focused on the concept of usability only. However, specialists were not involved in formal decision-making in the organisation and had no strong views on those issues.

Change in large organisations is often hard in the sense that it consumes a lot of time and energy (see, for example, Eriksson Citation2011). Efforts to achieve change in the area of ICT development was described as like ‘walking with a machetes in the jungle’. This metaphor can be interpreted in many ways in terms of the management of ICT work. With the jungle symbolising the organisation, even though the ‘jungle’ is significantly affected by the machete in the short-term or local perspective, from a long-term or ‘jungle-wide’ perspective it is stable over time and virtually unaffected by individual efforts to clear a path. This long-term stability that the quote describes can be seen as a reflection of the respondent's experience with stability in their organisation. This stability can be described as a result of how networks of dependencies are created, which embed and stabilise certain technologies or institutional arrangements: e.g. legal contracts, financial investments, corporate rituals and regulations (Geels Citation2005). In this quote, the manager indicates that a figurative machete is required to deal with this inertia. This inertial stability can be identified on many different levels, from the global and inter-organisational to the local and intra-organisational. In many cases the conservative effect of corporate stability is considered to be positive. But inertia can also hamper development, as this quote seems to indicate, and can prolong the survival of ‘unfit’ technologies – sometimes intentionally, in order to further political agendas (Walker Citation2000).

6.2. Discussion of the technological frames concept

In this study we applied technological frames as a conceptual tool to identify and compare the frames of ICT managers within an organisation with respect not to one technology in particular but to their perspectives on all use of technology in the organisation in general. We also used this framework to examine their technological frames concerning user-centred system design. In doing so we provide an example of how the concept of technological frames can be applied, and we provide valuable insights about attitudes towards a series of technologies and related practices in an organisation rather than one specific technology or implementation effort. On a practical level, using this approach to mapping and comparing technological frames from a general perspective could serve as a useful tool, for example, in preparation for an implementation or for investigating organisational readiness for novel technology. We believe that this study therefore makes an important contribution to the framework that reflects the current work practices in organisations, where users employ several systems in their work and not just a single system. Also, understanding how people experience their IT systems at work as a whole is an area that merits further research.

Understanding change is still a challenge, and we need more studies on design processes in large and complex organisations. Finally, we also need longitudinal studies, although such research is increasingly difficult thanks to the pressure to produce quick results.

6.3. Limitations of this study

Certain factors might limit the generalisability of this study. The sampling of the respondents was influenced by the organisation, which suggested which ICT leaders it believed met the sampling criteria, and it used a convenience sampling method, which has some limitations. Including both users and senior management in the study would probably have provided a broader perspective, as would a longitudinal study or a follow-up study. Although our study did include participants from a variety of roles, all interviewees held middle-management positions in the organisational hierarchy. It is likely that incongruences would have been more noticeable if the study had included participants in other positions, such as developers or end users.

Moreover, the theory of technological frames was used to analyse data, even though the interviews were not originally designed with this concept in mind. This means that the initial interview script did not include all aspects of the technological frames perspective.

6.4. Implications for the establishment of UCSD in organisations

Our analysis of the respondents’ technological frames indicates they hold several different viewpoints and agendas. This overall complexity of technological frames likely contributes to organisational inertia concerning the establishment of a user-centred design approach in the organisation.

The interviews with ICT leaders reveal their understanding of, and perspectives on, UCSD when working with ICT in the organisation. The problems they identify allows us to suggest implications for the establishment of a UCSD perspective in an organisation:

There is a need for more collaboration in organisations where different functional divisions collaborate on ICT matters. For example, staff from the Human Resources department and the ICT department need to collaborate on the issue of change management based on a user-centred perspective.

The interviews make it clear that considerable energy is needed to implement changes related to ICT or ICT development. When organisations establish a user-centred design perspective, they need to use the scaffolding structures that are connected to any organisational change, and they need to involve people who are familiar with change management, such as the HR professionals, senior managers and business strategists.

End users’ job descriptions need to recognise their roles as user representatives in order to promote engagement in user-centred design activities.

Organisations need to recruit usability experts or human–computer interaction professionals if they do not have such specialists on staff, and their responsibilities need to be defined.

There needs to be a centre of excellence, in the form of an organisational unit or group that is responsible for the user perspective in the organisation.

General knowledge of user-centred approaches or design thinking needs to improve. This would give project leaders a better base for integrating user-centred design perspectives and would improve support for working with these perspectives.

User-centred system design principles also need to be included when planning how to train users on new systems. This planning needs to include an understanding of the amount and type of training needed and must also consider the availability of user support and ongoing training after system launch.

User-centred system design needs to be discussed and implemented as a part of all existing processes and methods related to ICT.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank the respondents for their time and their valuable insights. We would also like to thank professor NN for valuable support and insights.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Bartis, E. 2007. “Two Suggested Extensions for SCOT: Technological Frames and Metaphors.” Society and Economy 29 (1): 123–138.

- Braun, V., and V. Clarke. 2013. Successful Qualitative Research: A Practical Guide for Beginners. London: Sage.

- Bryman, A. 2008. Social Research Methods. 3rd ed.. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Cajander, Å. 2010. “Usability–Who Cares?: The Introduction of User-Centred Systems Design in Organisations.” Doctoral diss., Acta Universitatis Upsaliensis.

- Cajander, Å, J. Gulliksen, and I. Boivie. 2006. “Management Perspectives on Usability in a Public Authority: A Case Study.” Proceedings of the 4th Nordic Conference on Human-Computer Interaction: Changing Roles, 38–47.

- Cajander, Å., M. Larusdottir, and J. Gulliksen. 2013. “Existing but Not Explicit-the User Perspective in Scrum Projects in Practice.” IFIP Conference on Human-Computer Interaction, 762–779.

- Cajander, Å., G. Nauwerck, and T. Lind. 2015. “Things Take Time: Establishing Usability Work in a University Context.” EUNIS J. High. Educ. IT 2 (1).

- Clemmensen, T., P. Campos, R. Orngreen, A. M. Pejtersen, and W. Wong, eds. 2006. Human Work Interaction Design: Designing for Human Work: The First IFIP TC 13.6 WG Conference: Designing for Human Work, February 13-15, 2006, Madeira, Portugal. Springer US. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/978-0-387-36792-7.

- Cortellazzo, L., E. Bruni, and R. Zampieri. 2019. “The Role of Leadership in a Digitalized World: A Review.” Frontiers in Psychology 10: 1938.

- Davidson, E. 2006. “A Technological Frames Perspective on Information Technology and Organisational Change.” The Journal of Applied Behavioral Science 42 (1): 23–39.

- Davidson, E., and D. Pai. 2004. “Making Sense of Technology Frames: Promise, Progress, and Potential.” In Relevant Theory and Informed Practice: Looking Forward from a 20 Year Perspective on IS Research, edited by B. Kaplan, D. Truex, D. Wastell, T. Wood-Harpe, and J. DeGross, 473–491. Boston: Kluwer.

- Eriksson, E. 2013. “Situated Reflexive Change: User-Centred Design in (to) Practice.” PhD Thesis, KTH Royal Institute of Technology.

- Eriksson, E., and A. Swartling. 2012. “UCD Guerrilla Tactics.” IFIP Working Conference on Human Work Interaction Design, 112–123.

- Geels, F. W. 2005. “The Dynamics of Transitions in Socio-Technical Systems: A Multi-Level Analysis of the Transition Pathway from Horse-Drawn Carriages to Automobiles (1860–1930).” Technology Analysis & Strategic Management 17 (4): 445–476. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/09537320500357319.

- Grünloh, C. 2018. “Using Technological Frames as an Analytic Tool in Value Sensitive Design.” Ethics and Information Technology. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s10676-018-9459-3.

- Gulliksen, J., Å Cajander, B. Sandblad, E. Eriksson, and I. Kavathatzopoulos. 2009. “User-Centred Systems Design as Organisational Change: A Longitudinal Action Research Project to Improve Usability and the Computerised Work Environment in a Public Authority.” International Journal of Technology and Human Interaction (IJTHI) 5 (3): 13–53.

- Gulliksen, J., B. Goransson, I. Boivie, S. Blomkvist, J. Persson, and A. Cajander. 2003. “Key Principles for User-Centred Systems Design.” Behaviour & Information Technology 22 (6): 397–409.

- Hastie, S., and S. Wojewoda. 2015. “Standish Group 2015 Chaos Report: Q&A with Jennifer Lynch.” Retrieved 1 (15): 2016.

- Iivari, N., and P. Abrahamsson. 2002. “The Interaction between Organisational Subcultures and User-Centred Design-a Case Study of an Implementation Effort.” In Proceedings of the 35th Annual Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences 2002, 3260–3268. IEEE. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1109/HICSS.2002.994362.

- ISO 9241-210:2010. 2019. Ergonomics of Human-System Interaction - Part 210: Human-Centred Design for Interactive Systems. International Organization for Standardization. Geneva, Switzerland.

- Jia, Y., M. K. Larusdottir, and A. Cajander. 2012. “The Usage of Usability Techniques in Scrum Projects.” International Conference on Human-Centred Software Engineering, 331–341.

- Kaasinen, E., V. Roto, J. Hakulinen, T. Heimonen, J. P. Jokinen, H. Karvonen, T. Keskinen, H. Koskinen, Y. Lu, and P. Saariluoma. 2015. “Defining User Experience Goals to Guide the Design of Industrial Systems.” Behaviour & Information Technology 34 (10): 976–991.

- Kashfi, P., R. Feldt, and A. Nilsson. 2019. “Integrating UX Principles and Practices into Software Development Organisations: A Case Study of Influencing Events.” Journal of Systems and Software 154: 37–58.

- Koen, M. C., and J. J. Willis. 2019. “Making Sense of Body-Worn Cameras in a Police Organisation: A Technological Frames Analysis.” Police Practice and Research, 1–17. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/15614263.2019.1582343.

- Lind, T. 2017. Inertia in Sociotechnical Systems: On IT-Related Change Processes in Organisations. Acta Universitatis Upsaliensis. http://urn.kb.se/resolve?urn=urn:nbn:se:uu:diva-326799.

- Nordström, M. 2005. “Styrbar systemförvaltning: att organisera systemförvaltningsverksamhet med hjälp av effektiva förvaltningsobjekt.” Doctoral dissertation, Linköpings universitet.

- Olesen, K. 2014. “Implications of Dominant Technological Frames Over a Longitudinal Period.” Information Systems Journal 24 (3): 207–228. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/isj.12006.

- Orlikowski, W. J., and D. C. Gash. 1994. “Technological Frames: Making Sense of Information Technology in Organisations.” ACM Transactions on Information Systems (TOIS) 12 (2): 174–207. doi:https://doi.org/10.1145/196734.196745.

- Petersen, A.-L. 2014. “Teachers’ Perceptions of Principals’ ICT Leadership.” Contemporary Educational Technology 5 (4): 302–315.

- Shaw, N. C., J. E. Lee-Partridge, and J. S. K. Ang. 1997. “Understanding End-User Computing through Technological Frames.” In Proceedings of the Eighteenth International Conference on Information Systems, 453.. Association for Information Systems. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.5555/353071.353210.

- Van Wart, M., A. Roman, X. Wang, and C. Liu. 2017. “Integrating ICT Adoption Issues Into (e-) Leadership Theory.” Telematics and Informatics 34 (5): 527–537.

- Walker, W. 2000. “Entrapment in Large Technology Systems: Institutional Commitment and Power Relations.” Research Policy 29 (7–8): 833–846. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/S0048-7333(00)00108-6.

- Willmer, M. 2007. “How Nursing Leadership and Management Interventions Could Facilitate the Effective use of ICT by Student Nurses.” Journal of Nursing Management 15 (2): 207–213.

Gammal referenslista

- Bartis, E. 2007. “Two Suggested Extensions for SCOT: Technological Frames and Metaphors.” Society and Economy 29 (1): 123–138.

- Clemmensen, T., P. Campos, R. Orngreen, and A. M. Pejtersen. 2006. “Human Work Interaction Design: Designing for Human Work.” First IFIP TC 13.6 WG Conference: Designing for Human Work, February 13–15.

- Davidson, E. 2006. “A Technological Frames Perspective on Information Technology and Organizational Change.” The Journal of Applied Behavioral Science 42 (1): 23–39. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0021886305285126.

- Davidson, E., and D. Pai. 2004. “Making Sense of Technological Frames: Promise, Progress, and Potential.” IFIP Advances in Information and Communication Technology 143: 473–492.

- Eriksson, E. 2013. “Situated Reflexive Change.” Doctoral dissertation, KTH Royal Institute of Technology.

- Ezzy, D. 2002. Qualitative Analysis : Practice and Innovation. Allen & Unwin.

- Geels, F. W. 2005. “The Dynamics of Transitions in Socio-Technical Systems: A Multi-Level Analysis of the Transition Pathway from Horse-Drawn Carriages to Automobiles (1860–1930).” Technology Analysis & Strategic Management 17 (4): 445–476. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/09537320500357319.

- Grünloh, C. 2018. “Using Technological Frames as an Analytic Tool in Value Sensitive Design.” Ethics and Information Technology, 1–5.

- Hastie, S., and S. Wojewoda. 2015. “Standish Group 2015 Chaos Report-Q&A with Jennifer Lynch.” Retreived 1 (15): 2016.

- Iivari, N., and P. Abrahamsson. 2002. “The Interaction between Organisational Subcultures and User-Centred Design-a Case Study of an Implementation Effort.” Proceedings of the 35th Annual Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences 2002, 3260–3268. IEEE. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1109/HICSS.2002.994362.

- ISO. 2010. ISO 9241-210: Ergonomics of Human-System Interaction – Part 210: Human-Centred Design Process for Interactive Systems. Geneva, Switzerland: International Organisation for Standardization.

- Kaasinen, E., V. Roto, J. Hakulinen, T. Heimonen, J. P. Jokinen, H. Karvonen, and H. Tokkonen. 2015. “Defining User Experience Goals to Guide the Design of Industrial Systems.” Behaviour & Information Technology 34 (10): 976–991.

- Lind, T. 2014. “Change and Resistance to Change in Health Care : Inertia in Socio-Technical Systems.” Doctoral dissertation, Uppsala University.

- Nordström, M. 2005. “Styrbar systemförvaltning: att organisera systemförvaltningsverksamhet med hjälp av effektiva förvaltningsobjekt.” Doctoral dissertation, Linköpings universitet.

- Olesen, K. 2014. “Implications of Dominant Technological Frames Over a Longitudinal Period: Implications of Dominant Technological Frames.” Information Systems Journal 24 (3): 207–228. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/isj.12006.

- Orlikowski, W., and D. Gash. 1994. “Technological Frames: Making Sense of Information Technology in Organisations.” ACM Transactions on Information Systems (TOIS) 12 (2): 174–207. doi:https://doi.org/10.1145/196734.196745.

- Shaw, N., J. Lee-Partridge, and J. Ang. 1997. “Understanding End-User Computing through Technological Frames.” Proceedings of the Eighteenth International Conference on Information Systems, 453. Association for Information Systems.

- Van Wart, M., A. Roman, X. Wang, and C. Liu. 2017. “Integrating ICT Adoption Issues into (e-)Leadership Theory.” Telematics and Informatics 34 (5): 527–537.

- Walker, W. 2000. “Entrapment in Large Technology Systems: Institutional Commitment and Power Relations.” Research Policy 29 (7): 833–846. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/S0048-7333(00)00108-6.

- Cajander, Å. 2010. "Usability–Who Cares?: The Introduction of User-Centred Systems Design in Organisations." Doctoral diss., Acta Universitatis Upsaliensis.