ABSTRACT

Self-determination theory posits that satisfaction of basic psychological needs is essential for well-being. Empirical evidence for the distinction between need frustration and need satisfaction has been growing within the last decade. However, research on player experience of need frustration is lagging behind. This paper investigates whether player experience of need frustration is distinct from need satisfaction in the online video games context. In addition, it examines whether in-game need frustration is a stronger predictor for negative outcomes such as problematic gaming, escapist motivations, real-life stress and exit intentions and whether in-game need satisfaction is a stronger predictor for positive outcomes such as satisfaction, concentration, subjective vitality and voice. We collected survey data from online video gamers. Path analyses showed that in-game need frustration is a distinct construct, predicting negative outcomes uniquely and more strongly than in-game need satisfaction, whereas in-game need satisfaction was more strongly associated with positive outcomes. The findings suggest that assessing both need satisfaction and frustration in gaming research could prove valuable.

1. Introduction

Self-determination theory (SDT) is a well-established motivation theory, comprised of six theories (Ryan and Deci Citation2017). One of these theories is the Basic Psychological Needs Theory (BPNT), which claims that the satisfaction of basic psychological needs is associated with better health and greater psychological well-being (Ryan and Deci Citation2000). The three basic psychological needs, which are posited to be universal and innate in human beings, are defined as autonomy, compestence and relatedness. Autonomy refers to being in concordance with one’s own actions and cognitions without feeling controlled, competence is the feelings of accomplishment, having a sense of self-efficacy and mastery, whereas relatedness is the experience of meaningful connections with others. Decades of research provide evidence that satisfaction of these needs is essential for well-being and positive outcomes, across several contexts (Ryan and Deci Citation2017).

Need satisfaction theory has been applied to a wide range of domains and received extensive support in the literature. The theory received support in cross-cultural studies (Sheldon et al. Citation2004) and across domains such as work, school, relationships and activities (Milyavskaya and Koestner Citation2011). Psychological basic need satisfaction was essential for well-being in human-beings in their daily lives. For instance, need satisfaction predicts the daily vitality levels of people (Martela, DeHaan, and Ryan Citation2016). More specifically, when people’s psychological needs of autonomy, competence and relatedness are higher on a day, they tend to rate their subjective vitality higher as well, on those days (Reis et al. Citation2000).

Although self-determination theory has a five decade-long history, the concept of need frustration as a separate construct from need satisfaction emerged within the last decade. Need frustration was proposed as a distinct and separate construct rather than a lack of need satisfaction (Bartholomew et al. Citation2011; Stebbings et al. Citation2012). Specifically, need satisfaction comprises of autonomy, competence and relatedness. Need frustration is the dissatisfaction of these needs, such that, autonomy satisfaction involves the willingness and free volition, whereas autonomy frustration involves feelings of being controlled (Deci and Ryan Citation1985). Competence is the capability to achieve and competence, frustration refers to the feelings of failure and doubting of one’s capability (Deci and Ryan Citation2010). Lastly, relatedness satisfaction involves the ‘genuine connection with others’ (Ryan Citation1995), whereas relatedness frustration refers to the feelings of loneliness and exclusion (Chen et al. Citation2015).

Need frustration is more closely related to maladjustment and contributes uniquely to the ill-being of individuals, independent of need satisfaction (Bhavsar et al., Citation2020; Vansteenkiste and Ryan Citation2013; Chen et al. Citation2015). Developments in this field suggest that need satisfaction and need frustration do not reside on a single continuum, but have unique effects (Sheldon and Hilpert Citation2012). Consequently, recent research also argues that they can coexist (Warburton et al. Citation2020). It was found that need satisfaction and need frustration showed unique effects on student motivation and learning (Wang et al. Citation2019), in addition to satisfaction in intimate relationships (Vanhee, Lemmens, and Verhofstadt Citation2016). The separateness of need satisfaction and need frustration concepts were tested and confirmed in different cultures as well (e.g. Italian context; Liga et al. Citation2020). Taken together, the evidence for the distinction between satisfaction and need frustration has accumulated within recent years.

Although basic needs are comprised of autonomy, competence and relatedness, these needs also show a moderate amount of overlap. Consequently, a common approach is to examine a general need satisfaction and general need frustration construct (Benita et al. Citation2020; Holding et al. Citation2020; Lee and Reeve Citation2020; Warburton et al. Citation2020). Therefore, we also took a similar approach and focused on the broader latent need satisfaction and need frustration which are comprised of three basic needs.

2. Need satisfaction and need frustration in games

The studies on need satisfaction in games started during the mid-2000s, and has been influential in gaming research and practice. The growing evidence suggests that satisfaction of basic psychological needs in games results in increased enjoyment during gameplay, increased post-play wellbeing and increased motivation for future engagements (Ryan, Rigby, and Przybylski Citation2006; Vella, Johnson, and Hides Citation2015). It was also found that need satisfaction is associated with harmonious passion and increased energy levels in players (Przybylski et al. Citation2009). Moreover, Player Experience of Need Satisfaction (PENS; Rigby and Ryan Citation2007, Citation2011) scale is widely adopted by researchers to measure player experiences (Denisova, Nordin, and Cairns Citation2016; Mora-Cantallops and Sicilia Citation2018), due to its robustness (Brühlmann and Schmid Citation2015; Johnson, Gardner, and Perry Citation2018).

Nevertheless, the PENS measure was developed before the recent developments in basic need satisfaction theory, and it does not measure need frustration. In line with the findings in other domains, need satisfaction in games might also be different than the need frustration in games. Initial evidence using general (not context specific) need satisfaction and frustration measures shows that need frustration possesses stronger associations with obsessive passion and overuse than need satisfaction does in screen-based activities such as video gaming (Tóth-Király et al. Citation2019). In addition, measures of daily need frustration had a stronger relationship with problematic gaming when compared to the measures of daily need satisfaction (Mills et al. Citation2018c). However, research on whether the distinction between in-game need satisfaction and in-game need frustration also leads to different outcomes is lacking.

In practice, the distinct nature of frustration and satisfaction can be observed in the mechanics of games as well. Sometimes games intentionally frustrate users to create feelings of revenge, which consequently leads to greater engagement and satisfaction (Grayson Citation2017). Here, measuring frustration – rather than lack of satisfaction- might be more valuable. It can be especially important to measure the experience of need frustration in transformative, perspective-changing or meaningful games (Iten, Steinemann, and Opwis Citation2018; Oliver et al. Citation2016; Whitby, Deterding, and Iacovides Citation2019). These games are not necessarily joyful and might be composed of built-in frustrations through game mechanisms or narrative, for the purpose of changing the opinion of a player or transforming them for the better. Moreover, some players appreciate the emotional challenges in games, in addition to the more conventional cognitive and motor challenges (Bopp, Opwis, and Mekler Citation2018). Players might be experiencing frustration in these games as well. On the other hand, some of the other previous studies suggested that frustration in games can result in lowered perceived self-efficacy which can damage player loyalty (Huang et al. Citation2017). Also, for high-frequency games, frustration can be demotivating which can ultimately result in the discontinuation of that game (Liao, Huang, and Teng Citation2016). In summary, the frustration concept can be a promising tool both for game designers who want to spot the negative and unconventional experiences of their games and for researchers who aim to study the frustrating aspects of gaming.

Nevertheless, research on need frustration in games is scarce. Although a handful of studies tap into the need frustration aspects of gaming, these studies investigate the general need for frustration (e.g. need frustration in one’s life not in-game) and its effect on gaming habits. For instance, it was found that the daily need frustration predicts problematic gaming (Mills et al. Citation2018a). Similarly, another study found that obsessive passion and gender moderated the relationship between daily need frustration and time spent gaming (for low obsessive passion game users and males, the relationship was significant; Mills et al. Citation2018b). Other studies found that real-world need satisfaction and need frustration are better predictors of wellbeing than in-game need satisfaction and need frustration (Allen and Anderson Citation2018), however, no studies to our knowledge investigated how in-game need satisfaction and in-game need frustration are associated with game-related outcomes and whether the in-game need frustration is a distinct construct with its own distinct construct. Whether the player experience of need frustration goes above and beyond need satisfaction, in predicting negative player outcomes in not known yet. Therefore the goal of this research is to apply and test the recent developments in SDT literature in game studies field, as well as, provide a tool for researchers to capture in-game need frustration.

In line with the findings that need frustration is a stronger predictor of negative outcomes (e.g. problematic behaviour), whereas need satisfaction is a stronger predictor for positive outcomes (e.g. wellbeing) in general (Chen et al. Citation2015), we examined whether this is the case in online gaming context as well. Therefore, we had two research questions for this study: Is in-game need frustration a distinct construct than in-game need satisfaction? Does player experience of need frustration (PENF) predicts the negative outcomes stronger than player experience of need satisfaction (PENS)?

3. Need satisfaction, need frustration and player experience outcomes

To examine whether in-game need frustration is a distinct construct and whether it is a stronger predictor of negative outcomes than in-game need satisfaction (also whether need satisfaction better predicts positive outcomes), we used both negative and positive outcomes that are frequently used in games research such as problematic gaming (Demetrovics et al. Citation2012; Fumero et al. Citation2020; Scerri et al. Citation2019) and escapism for negative (Hagström and Kaldo Citation2014) and concentration (Liu and Li Citation2011; Sherry Citation2004) and satisfaction (Klimmt et al. Citation2009; Phan, Keebler, and Chaparro Citation2016) for positive. We also used quitting intentions as a negative outcome, whereas voicing the problems about the game as a positive outcome (Uysal Citation2016). Lastly, we used subjective vitality as an indicator of well-being (Allen and Anderson Citation2018; Przybylski, Rigby, and Ryan Citation2010; Rieger et al. Citation2014; Vella, Johnson, and Hides Citation2013, Citation2015), and perceived daily stress as an indicator of ill-being of a player (Canale et al. Citation2019), which were regarded as positive and negative outcomes, respectively.

[H1] Player experience of need satisfaction would be more strongly associated with positive outcomes, compared to player experience of need frustration.

[H2] Player experience of need frustration would be more strongly associated with negative outcomes, compared to player experience of need satisfaction.

4. Method

4.1. Procedure and participants

The survey study was announced in Amazon’s MTurk. The participation requirements were residing in the USA, having an approval rate of at least 95%, being older than 18 years old and actively playing an online game. We left the interpretation of ‘active’ to the participants but also collected how much they spend time on gaming (hours per week).Footnote1 Participants read the informed consent, they were instructed that participation is voluntary. After the demographic questions (age, gender, ethnicity, employment, education, gameplay time in hours per week and in years), participants entered the favourite online game they were playing at the time. The rest of the questions were asked specifically about that game.

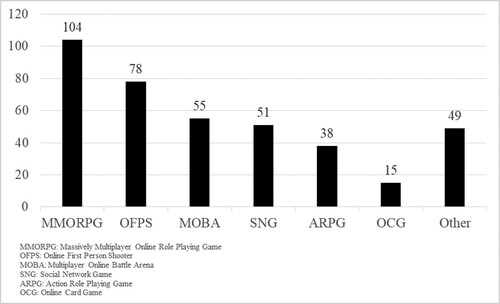

After discarding 6 participants who reported zero time spent gaming, we had 390 players in the study (192 male and 198 female). The age of the participants ranged from 18 to 69 with a mean of 35.08 (SD = 10.00). 296 of them were white, 36 were African American, 35 were Asian, and 6 were American Indian /Alaska Native (16 marked other). 142 participants had a 4-year degree and 310 participants played video games at least 4 h a week. About 90% of the participants stated that they played games for at least four years and 91% of the participants rated themselves experienced as at least a moderate amount to a great deal. Participants were playing a range of games such as MMORPG (massively multiplayer online role-playing game; e.g. World of Warcraft, Elder Scrolls Online, Guild Wars 2), OFPS (online first-person shooter, e.g. Call of Duty, Overwatch, Battlefield), MOBA (multiplayer online battle arena; League of Legends, Fortnite, Dota 2), SNG (social network games; e.g. Candy Crush, Bejeweled, The Sims), ARPG (action role playing game, e.g. Diablo, Path of Exile, GTA 5) and OCG (online card game; e.g. Hearthstone, Poker, Canasta). Missing data was less than 5%, therefore data imputation was carried out. The demographics data is summarised in . Also, the breakdown of genres preferred by the participants is summarised in (Some of the ‘Other’ genre answers were ‘Puzzle’, ‘Sports’, ‘Racing’, ‘Survival’ and ‘Arcade’).

Table 1. Demographics of the participants (N = 390).

4.2. Measures

All of the scales were adapted for the specific game each participant was playing. All constructs were measured on a 1 ‘strongly disagree’ to 7 ‘strongly agree’ Likert Scale.

4.2.1. In-game need satisfaction

Need Satisfaction was measured by Player Experience of Need Satisfaction (PENS) Scale (Ryan, Rigby, and Przybylski Citation2006). We used three subscales of PENS which are autonomy (e.g. ‘I feel a sense of choice and freedom in the things I undertake in [my current favorite online game].’), competence (e.g. ‘I feel capable at what I do in [my current favorite online game].’) and relatedness (e.g. ‘I feel close and connected to other people who are important to me in [my current favorite online game].’). These subscales had three items and the internal reliabilities of the scales were good (α = .71, α = .82 and α = .89, respectively). The overall internal reliability of PENS was α = .84.

4.2.2. Positive outcomes.

General satisfaction scale was adapted from another study (Uysal Citation2016). The scale consisted of 5 items (e.g. ‘I feel satisfied with [my current favorite online game].’) and had an internal reliability of α = .84. Concentration was measured using the pertinent subscale of the GameFlow scale (Sweetser and Wyeth Citation2005). It consisted of six items (e.g. ‘[my current favorite online game] provides stimuli that are worth attending to.’). The internal reliability of the scale was α = .78. Subjective vitality was measured by the subjective vitality scale (Ryan and Frederick Citation1997). It consisted of five items (e.g. ‘I feel energized.’). The internal reliability of the scale was α = .86. Lastly, voice behavior was assessed using 2 items (e.g. ‘When there are problems with [my current favorite online game], I try to work out a solution.’; Uysal Citation2016) and had an internal reliability of α = .55.

4.2.3. In-Game need frustration.

Need frustration was measured by the frustration items of the Basic Psychological Need Frustration and Satisfaction scale (Chen et al. Citation2015). Frustration subscales consisted of three items each measuring autonomy frustration (e.g. ‘I feel forced to do many things I wouldn’t choose to do in [my current favorite online game].’), competence frustration (e.g. ‘I feel insecure about my abilities in [my current favorite online game].’) and relatedness frustration (e.g. ‘I feel the relationships I have are just superficial in [my current favorite online game].’). The internal reliabilities of these scales were α = .77, α = .83 and α = .71 respectively. The overall internal reliability of Need Frustration Scale was α = .89.

4.2.4. Negative outcomes.

Problematic gaming was measured by a previously developed scale (Charlton and Danforth Citation2007; Xu, Turel, and Yuan Citation2012). The scale consisted of eight items (e.g. ‘My social life has sometimes suffered because of me playing [my current favorite online game].’) and with an internal reliability of α = .95. Gaming related escapism was measured by using items from a previous study (Hagström and Kaldo Citation2014). It consisted of three items (e.g. ‘I play [my current favorite online game] to avoid thinking about some of my real-life problems or worries.’) and the internal reliability of the scale was α = .83. Daily stress was measured using the perceived stress scale (Cohen, Kamarck, and Mermelstein Citation1983, Citation1994). The scale consisted of five items (e.g. ‘I cannot cope with all the things that I have to do.’) and the internal reliability of the scale was α = .85. Finally, exit behavior was assessed using two items (e.g. ‘When there are problems with [my current favourite online game], I feel so angry I quit playing the game.’; Uysal Citation2016) and had an internal reliability of α = .58.

5. Results

5.1. Preliminary analyses

First, we conducted confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) to test our measurement model. We used the SPSS AMOS software. After removing items that have loadings less than .50 (i.e. 2 items from Need Satisfaction, 1 item from Need Frustration and 2 items from Concentration), the model fit was good (RMSEA = 0.043, 90% CI [0.040, 0.047], CFI = 0.93, TLI = 0.92). The resulting items, their loadings, means and standard deviations are summarised in .

Table 2. Item factor loadings, means and standard deviations.

The correlation analyses showed that player experience of need satisfaction was more strongly associated with positive outcomes whereas player experience of need frustration was more strongly associated with negative outcomes, as expected. All of the square root of AVEs were higher than the inter-correlations of the constructs indicating good discriminant validity (Hair Jr et al. Citation2010). The correlations, means, standard deviations, composite reliabilities and average variance extracted values are summarised in .Footnote2

Table 3. Correlation table.

Lastly, as an ancillary effort, we checked the mean differences in genres in terms of in-game need satisfaction and in-game need frustration. There was no significant difference between the means of genres in terms of in-game need satisfaction. However, the mean of in-game need frustration of SNG genre was statistically significantly less than MOBA and OFPS (p = .006, SE = .26 and p = .047, SE = .24 respectively).

5.2. Primary analysis

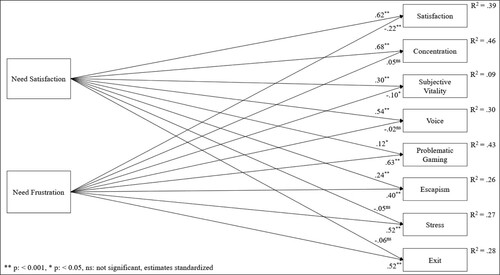

There is limited consensus on the required sample size for analysing structural models, however, it is generally advised to have at least 10 participants per parameter to conduct adequate structural equation modelling (SEM) with latent variables (Bentler and Chou Citation1987; Hoe Citation2008; Kline Citation2015). Our outcome variables with their items would require 148 distinct parameters to be estimated, for which the minimum sample size would require 1480 participants for a robust latent-based SEM approach. Since we did not have a sample size close to this number, we conducted path analysis to test our model (by averaging the item scores, the parameters to be estimated went down to 27). The path estimates showed that in-game need satisfaction predicted positive outcomes stronger than in-game need frustration whereas in-game need frustration predicted negative outcomes stronger than in-game need satisfaction (). We also conducted correlation comparison analyses using ‘cocor’ package for R (Diedenhofen & Musch, Citation2015). For every dependent variable (i.e. a pair of correlations), all of the correlations were statistically significantly different from each other at the .05 alpha level. Therefore, in-game need satisfaction predicted general satisfaction, concentration, subjective vitality and voice intentions stronger than in-game need frustration. Similarly, need frustration predicted problematic gaming, escapism, stress and exit intentions stronger than need satisfaction. Consequently, all of our hypotheses were supported.

6. Discussion

In this study, results supported that need frustration in games is a distinct construct than needing satisfaction in games. In line with recent research in other contexts, in-game need frustration showed stronger unique associations with negative outcomes, in-game whereas need satisfaction showed stronger unique associations with positive outcomes. More specifically, player experience of need frustration was a stronger predictor for both negative game-related and well-being related outcomes such as escapist motivations, problematic gaming, exit intentions and perceived daily stress. Similarly, player experience of need satisfaction was a stronger predictor of both positive game-related and well-being related outcomes such as concentration, overall gaming satisfaction, constructive attempts to resolve problems in the game (i.e. voice) and subjective vitality.

On a more granular level, we found that need satisfaction strongly predicted the overall satisfaction and concentration during online gaming, which corroborates the previous findings (Hagger and Chatzisarantis Citation2007). Need frustration was found to be negatively associated with overall gaming satisfaction, however, this relationship was weaker than the relationship between in-game need satisfaction and overall gaming satisfaction. As for concentration, need frustration did not have a significant effect. In-game need satisfaction also predicted subjective vitality of players which provided further evidence that satisfaction of needs in the game is also associated with general wellbeing (Ryan, Rigby, and Przybylski Citation2006). Need frustration on the other hand was negatively associated with subjective vitality, however, this was a weaker relation, as hypothesised. Results also showed that satisfaction of needs resulted in the constructive attempts from players, indicating the problems in the game to be overcome, rather than directly quitting the game. Need frustration did not have a significant effect on voice, confirming our hypothesis, which might suggest that frustrated players tend to abstain from giving constructive feedback.

As for the negative outcomes, in-game need frustration was a better predictor than in-game need satisfaction. Need frustration was strongly associated with problematic gaming suggesting that players who are involved with gaming problematically are experiencing more frustration in their gaming activities. Also, the results showed that players who play games for escaping their real-life problems or for avoiding social encounters experience more frustration in games. It is also important to note that in-game need satisfaction had a significant effect on problematic gaming and escapist motivations as well. However, they were weaker associations compared to need frustration’s relationships with these outcomes, in line with the theory. Need frustration was associated with daily perceived stress whereas in-game need satisfaction was not significantly related to it. This might suggest that when players’ needs are frustrated in game they tend to experience stress in their daily lives or stressed players tend to have frustrating experiences in games. Players who feel frustrated in online games might be carrying their negative feelings over to subsequent daily activities and therefore feel more stressed overall, or already stressed-out players in daily life might be experiencing less autonomy and competence in online games – although the game is designed to satisfy these needs – which results in overall increased in-game frustration. Lastly, need frustration was found to be strongly associated with exit intentions. This suggests that players who are experiencing higher need frustration in the games are more likely to quit the game when they experience problems (bugs etc.). Need satisfaction was not associated with exit intentions at all. This was in line with our hypotheses, as well. Lastly, these findings are also in line with previous research stating that when there is problematic gaming behaviour, players mostly try to repress their frustrations rather than pursuing satisfaction (Wan and Chiou Citation2006). This signifies the measuring of need frustration in addition to the satisfaction of players as well.

Player experience of need satisfaction was found to be weakly correlated with the player experience of need frustration. This provides further evidence that needs satisfaction and need frustration constructs are not necessarily opposite ends of the same continuum. Future studies might delve further into this and examine how need satisfaction is related to need frustration as this finding is in contrast with a recent study that showed a high negative correlation between the two constructs (Tóth-Király et al. Citation2019).

In sum, all of our hypotheses were supported since the player experience of need frustration was found to be more strongly related with negative outcomes, whereas need player experience of need satisfaction was found to be more strongly associated with positive outcomes. This study also expanded the previous findings on need frustration in games by presenting its associations with negative in-game experiences, player attitudes and player wellbeing. Moreover, it complements the previous studies which utilise the daily need frustration perspective of SDT in the gaming domain without explicitly considering the in-game need frustration aspect (i.e. Mills et al. Citation2018a, Citation2018b). In addition, it also provided evidence for the argument that need frustration is a different entity than need satisfaction (Chen et al. Citation2015). Although this is in line with the literature which supports need frustration as a separate construct (e.g. Vansteenkiste and Ryan Citation2013; Warburton et al. Citation2020), it is contradictory to the claim that needs satisfaction and needs frustration are just two ends of a fulfillment continuum (e.g. Tóth-Király et al. Citation2019). More research is needed in the game studies field to be able to understand whether need frustration is a distinct construct.

Games usually tend to provoke positive emotions and experiences in players however, they can elicit a wide range of emotions, including negative ones as well (Bopp, Mekler, and Opwis Citation2016). Some games even intentionally create disturbing narratives for players to understand the experiences of other people. For instance, Hellblade: Senua's Sacrifice puts the players in the shoes of a person with psychosis, which is a mental illness characterised by the experience of a distorted reality (Ninja Theory Citation2017). Although games provide a spectrum of experiences, researchers started studying the ‘un-fun’ factors of games and more specifically need frustration, fairly recently. There is growing support into the argument that mixing negative emotions with positive ones can provide overall positive experiences (Fokkinga and Desmet Citation2012). It was found that the experience of frustration can be a factor of fun as well (Allison, Carter, and Gibbs Citation2015). For instance, some games such as Fallout 4 (Bethesda Game Studios Citation2015) or Darkest Dungeon (Red Hook Studios Citation2016) can create discomfort in players, however, they eventually lead to richer experiences and reflections (Brown et al. Citation2015; Gowler and Iacovides Citation2019; Jørgensen Citation2016). It was also found that fearful experiences might be positively received by players (Endress, Mekler, and Opwis Citation2016). Moreover, some game designers claim that they are already using ‘engaging frustration’ for fostering greater player involvement with the game and the game’s community (McAloon Citation2017). Investigating how need frustration might play a role in relation to these concepts would be a worthwhile future research agenda.

Although the genre was not a centre focus for this study, exploratory efforts showed that SNG players experienced less in-game need frustration than OFPS and MOBA players. Future studies can consider examining what kinds of game design, in general, are more prone to in-game need frustration and how it effects the overall experience of that genre’s players.

6.1. Implications and limitations

Present study has implications for game developers. The player experience of need frustration scale can be used by developers to spot the negative experiences of players. This might be useful for two-fold. First, the developers can understand the parts of their games where players get frustrated. Second, it might also be useful for developers to measure the negative experiences when they intentionally create frustrating experiences for players, since incorporating subtle frustrating elements in games are shown to help positive gaming experience (Boulton et al. Citation2017). Also, some games might involve extreme emotions (Montola Citation2010) for which the designers can use the player experience of need frustration as a measuring tool. The player experience of need frustration scale gives a more nuanced approach for examining the psychological needs and self-determination in general. In fact, it is also advised in the basic psychological needs literature that need satisfaction and need frustration should be examined in combination (Warburton et al. Citation2020).

This study has several limitations. First, the findings presented here is an outcome of a cross-sectional design. Controlled experiments are needed in order to draw more definitive conclusions on causations. Creating alternative models is possible and the causal relationships shown here might be reversed as well. Second, the sample was restricted to the US and future studies might aim for a more diverse participant pool. Third, research shows that need strength is another aspect of BPNT which might affect the strength of the relationships between need satisfaction/frustration and their outcomes (Chen et al. Citation2015). Future studies might investigate whether players’ need strength interact with the relationships presented in this study. In addition, this study did not include some other major measurements of player experiences such as thepresence or player retention. Examining how these constructs are related to the player experience of need frustration might be another interesting venue for future research. Moreover, types of games might have an influence on these relationships as well. Investigating genre differences – which might require a wider data collection – can also be a possible future research direction. The AVE values of voice, exit and concentration were found to be slightly less than the critical value of .5. Future studies might consider alternative measures for these constructs. Similarly, future studies can investigate need frustration in the light of recent research trends such as purchase intentions of virtual items or freemium services, pandemic effects, social aspects/team play or gamification (Bae et al. Citation2019; Hamari, Hanner, and Koivisto Citation2020; Laato, Islam, and Laine Citation2020; Liao et al. Citation2021; Rapp Citation2020).

7. Conclusion

This study has two major contributions to the literature. First, it presents evidence that player experience of need frustration (PENF) is a distinct construct with three sub constructs: autonomy frustration, competence frustration and relatedness frustration. Second, It shows that in-game need satisfaction has stronger unique associations with positive outcomes (i.e. satisfaction, concentration, subjective vitality and constructive voice intentions) whereas in-game need frustration has stronger unique associations with negative outcomes (i.e. problematic gaming, escapist motivations, perceived stress and exit intentions), respectively. Overall, the player experience of need frustration scale can be useful for future studies which aim to investigate negative experiences in gaming and also for developers who would like to evaluate their design.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability

The data underlying this article is available in FigShare Repository, at https://figshare.com/s/6d95695f61f03383a92c

Notes

1 Ten participants reported ‘0’ hours per week as their time spent gaming. Six of them also did not mention their favourite games and therefore they were discarded. The remaining four were kept in the study since they were engaged, completed the study in reasonable durations and reported their favourite games. It is possible that they play less than 1 h weekly and that might be the reason they put in ‘0’.

2 Some of the AVE values were slightly less than .5, however, since the composite reliabilities are at acceptable levels of 0.6, we concluded that the internal reliability of the measurement is acceptable (Fornell and Larcker Citation1981).

References

- Allen, J. J., and C. A. Anderson. 2018. “Satisfaction and Frustration of Basic Psychological Needs in the Real World and in Video Games Predict Internet Gaming Disorder Scores and Well-Being.” Computers in Human Behavior 84: 220–229. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2018.02.034.

- Allison, F., M. Carter, and M. Gibbs. 2015. “Good Frustrations: The Paradoxical Pleasure of Fearing Death in Day.” In Proceedings of the Annual Meeting of the Australian Special Interest Group for Computer Human Interaction, 119–123. ACM. doi:10.1145/2838739.2838810.

- Bae, J., S. J. Kim, K. H. Kim, and D. M. Koo. 2019. “Affective Value of Game Items: A Mood Management and Selective Exposure Approach.” Internet Research, 29, 315–328.

- Bartholomew, K. J., N. Ntoumanis, R. M. Ryan, J. A. Bosch, and C. Thøgersen-Ntoumani. 2011. “Self-determination Theory and Diminished Functioning: The Role of Interpersonal Control and Psychological Need Thwarting.” Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin 37 (11): 1459–1473. doi:10.1177/0146167211413125.

- Benita, M., M. Benish-Weisman, L. Matos, and C. Torres. 2020. “Integrative and Suppressive Emotion Regulation Differentially Predict Well-being Through Basic Need Satisfaction and Frustration: A Test of Three Countries.” Motivation and Emotion 44 (1): 67–81. doi:10.1007/s11031-019-09781-x.

- Bentler, P. M., and C. P. Chou. 1987. “Practical Issues in Structural Modeling.” Sociological Methods & Research 16 (1): 78–117. doi:10.1177/0049124187016001004.

- Bethesda Game Studios. 2015. Fallout 4. Rockville, MD: Bethesda Softworks.

- Bhavsar, N., K. Bartholomew, E. Quested, D. Gucciardi, C. Thøgersen-Ntoumani, J. Reeve, P. Sarrazin, and N. Ntoumanis. 2020. “Measuring Psychological Need States in Sport: Theoretical Considerations and a New Measure.” Psychology of Sport and Exercise 47: 101617. doi:10.1016/j.psychsport.2019.101617.

- Bopp, J. A., E. D. Mekler, and K. Opwis. 2016. “Negative Emotion, Positive Experience? Emotionally Moving Moments in Digital Games.” In Proceedings of the 2016 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, 2996–3006. ACM. doi:10.1145/2858036.2858227.

- Bopp, J. A., K. Opwis, and E. D. Mekler. 2018. “‘An Odd Kind of Pleasure’: Differentiating Emotional Challenge in Digital Games.” In Proceedings of the 2018 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, 41. ACM. doi:10.1145/3173574.3173615.

- Boulton, A., R. Hourizi, D. Jefferies, and A. Guy. 2017. “A Little Bit of Frustration Can Go a Long Way.” In Advances in Computer Games, 188–200. Cham: Springer. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-71649-7_16.

- Brown, J., K. Gerling, P. Dickinson, and B. Kirman. 2015. “Dead Fun: Uncomfortable Interactions in a Virtual Reality Game for Coffins.” In Proceedings of the 2015 Annual Symposium on Computer-Human Interaction in Play, 475–480. ACM. doi:10.1145/2793107.2810307.

- Brühlmann, F., and G. M. Schmid. 2015. “How to Measure the Game Experience? Analysis of the Factor Structure of Two Questionnaires.” In Proceedings of the 33rd Annual ACM Conference Extended Abstracts on Human Factors in Computing Systems, 1181–1186. ACM. doi:10.1145/2702613.2732831.

- Canale, N., C. Marino, M. D. Griffiths, L. Scacchi, M. G. Monaci, and A. Vieno. 2019. “The Association Between Problematic Online Gaming and Perceived Stress: The Moderating Effect of Psychological Resilience.” Journal of Behavioral Addictions 8 (1): 174–180. doi:10.1556/2006.8.2019.01.

- Charlton, J. P., and I. D. W. Danforth. 2007. “Distinguishing Addiction and High Engagement in the Context of Online Game Playing.” Computers in Human Behavior 23 (3): 1531–1548. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2005.07.002.

- Chen Beiwen, Vansteenkiste Maarten, Beyers Wim, Boone Liesbet, Deci Edward L., Van der Kaap-Deeder Jolene, Duriez Bart, Lens Willy, Matos Lennia, Mouratidis Athanasios, Ryan Richard M., Sheldon Kennon M., Soenens Bart, Van Petegem Stijn, Verstuyf Joke. 2015. “Basic Psychological Need Satisfaction, Need Frustration, and Need Strength Across Four Cultures.” Motivation and Emotion 39 (2): 216–236. doi:10.1007/s11031-014-9450-1.

- Cohen, S., T. Kamarck, and R. Mermelstein. 1983. “A Global Measure of Perceived Stress.” Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 24, 385–396. doi:10.2307/2136404.

- Cohen, S., T. Kamarck, and R. Mermelstein. 1994. Perceived Stress Scale. Measuring Stress: A Guide for Health and Social Scientists, 10. https://www.northottawawellnessfoundation.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/04/PerceivedStressScale.pdf.

- Deci, E. L., and R. M. Ryan. 1985. “The General Causality Orientations Scale: Self-determination in Personality.” Journal of Research in Personality 19: 109–134. doi:10.1016/0092-6566(85)90023-6.

- Deci, E. L., and R. M. Ryan. 2010. “Intrinsic Motivation.” The Corsini Encyclopedia of Psychology, 1–2. doi:10.1002/9780470479216.corpsy0467.

- Demetrovics Zsolt, Urbán Róbert, Nagygyörgy Katalin, Farkas Judit, Griffiths Mark D., Pápay Orsolya, Kökönyei Gyöngyi, Felvinczi Katalin, Oláh Attila, Laks Jerson. 2012. “The Development of the Problematic Online Gaming Questionnaire (POGQ).” PloS one 7 (5): e36417. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0036417.

- Denisova, A., A. I. Nordin, and P. Cairns. 2016. “The Convergence of Player Experience Questionnaires.” In Proceedings of the 2016 Annual Symposium on Computer-Human Interaction in Play, 33–37. ACM. doi:10.1145/2967934.2968095.

- Diedenhofen, B., and J. Musch. 2015. “cocor: A Comprehensive Solution for the Statistical Comparison of Correlations.” PLoS ONE 10 (4): e0121945. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0121945.

- Endress, S. I., E. D. Mekler, and K. Opwis. 2016. It’s Like I Would Die as Well: Gratifications of Fearful Game Experience. In Proceedings of the 2016 Annual Symposium on Computer-Human Interaction in Play Companion Extended Abstracts, 149–155. ACM. doi:10.1145/2968120.2987716.

- Fokkinga, S., and P. Desmet. 2012. “Meaningful Mix or Tricky Conflict? A Categorization of Mixed Emotional Experiences and Their Usefulness for Design.” In Proceedings of the 8th International Design and Emotion Conference, 11–14. London: Central Saint Martin College of Art & Design. http://resolver.tudelft.nl/uuid:dca821fe-db93-4bdb-b783-588a098d55db.

- Fornell, C., and D. F. Larcker. 1981. “Evaluating Structural Equation Models with Unobservable Variables and Measurement Error.” Journal of Marketing Research 18 (1): 39–50. doi:10.1177/002224378101800104.

- Fumero, A., R. J. Marrero, J. M. Bethencourt, and W. Peñate. 2020. “Risk Factors of Internet Gaming Disorder Symptoms in Spanish Adolescents.” Computers in Human Behavior 111: 106416. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2020.106416.

- Gowler, C., and I. Iacovides. 2019. “‘Horror, Guilt and Shame’ – Uncomfortable Experiences in Digital Games.” In CHI PLAY 2019. York. doi:10.1145/3311350.3347179.

- Grayson, N. 2017, March 7. Frustration Can Improve Video Games, Designer Found. https://kotaku.com/frustration-can-improve-video-games-designer-found-1793045192.

- Hagger, M. S., and N. L. Chatzisarantis. 2007. “Advances in Self-determination Theory Research in Sport and Exercise.” Psychology of Sport and Exercise 8 (5): 597–599. doi:10.1016/j.psychsport.2007.06.003.

- Hagström, D., and V. Kaldo. 2014. “Escapism among Players of MMORPGs – Conceptual Clarification, its Relation to Mental Health Factors, and Development of a new Measure. Cyberpsychology.” Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking 17 (1): 19–25. doi:10.1089/cyber.2012.0222.

- Hair Jr, J. F., W. C. Black, B. J. Babin, and R. E. Anderson. 2010. Multivariate Data Analysis (7th ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall.

- Hamari Juho, Hanner Nicolai, Koivisto Jonna. 2020. “"Why pay Premium in Freemium Services?" A Study on Perceived Value, Continued use and Purchase Intentions in Free-to-Play Games.” International Journal of Information Management 51: 102040. doi:10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2019.102040.

- Hoe, S. L. 2008. “Issues and Procedures in Adopting Structural Equation Modeling Technique.” Journal of Applied Quantitative Methods 3 (1): 76–83.

- Holding, A. C., A. St-Jacques, J. Verner-Filion, F. Kachanoff, and R. Koestner. 2020. “Sacrifice – but at What Price? A Longitudinal Study of Young Adults’ Sacrifice of Basic Psychological Needs in Pursuit of Career Goals.” Motivation and Emotion 44 (1): 99–115. doi:10.1007/s11031-019-09777-7.

- Huang, H. C., G. Y. Liao, K. L. Chiu, and C. I. Teng. 2017. “How Is Frustration Related to Online Gamer Loyalty? A Synthesis of Multiple Theories.” Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking 20 (11): 683–688. doi:10.1089/cyber.2017.0023.

- Iten, G. H., S. T. Steinemann, and K. Opwis. 2018, April. “Choosing to Help Monsters: A Mixed-Method Examination of Meaningful Choices in Narrative-Rich Games and Interactive Narratives.” In Proceedings of the 2018 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, 341. ACM. doi:10.1145/3173574.3173915.

- Johnson, D., M. J. Gardner, and R. Perry. 2018. “Validation of Two Game Experience Scales: The Player Experience of Need Satisfaction (PENS) and Game Experience Questionnaire (GEQ).” International Journal of Human-Computer Studies 118: 38–46. doi:10.1016/j.ijhcs.2018.05.003.

- Jørgensen, K. 2016. “The Positive Discomfort of Spec Ops: The Line.” Game Studies 16: 2. http://gamestudies.org/1602/articles/jorgensenkristine.

- Klimmt, C., C. Blake, D. Hefner, P. Vorderer, and C. Roth. 2009. “Player Performance, Satisfaction, and Video Game Enjoyment.” In International Conference on Entertainment Computing, 1–12. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer.

- Kline, R. B. 2015. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling. New York: Guilford publications.

- Laato, S., A. N. Islam, and T. H. Laine. 2020. “Did Location-based Games Motivate Players to Socialize During COVID-19?” Telematics and Informatics 54: 101458. doi:10.1016/j.tele.2020.101458.

- Lee, W., and J. Reeve. 2020. “Brain Gray Matter Correlates of General Psychological Need Satisfaction: A Voxel-based Morphometry Study.” Motivation and Emotion 44 (1): 151–158. doi:10.1007/s11031-019-09799-1.

- Liao, G. Y., T. C. E. Cheng, W. L. Shiau, and C. I. Teng. 2021. “Impact of Online Gamers’ Conscientiousness on Team Function Engagement and Loyalty.” Decision Support Systems 142: 113468. doi:10.1016/j.dss.2020.113468.

- Liao, G. Y., H. C. Huang, and C. I. Teng. 2016. “When Does Frustration Not Reduce Continuance Intention of Online Gamers? The Expectancy Disconfirmation Perspective.” Journal of Electronic Commerce Research 17 (1): 65. http://www.jecr.org/node/487.

- Liga, F., S. Ingoglia, F. Cuzzocrea, C. Inguglia, S. Costa, A. Lo Coco, and R. Larcan. 2020. “The Basic Psychological Need Satisfaction and Frustration Scale: Construct and Predictive Validity in the Italian Context.” Journal of Personality Assessment, 102 (1): 102–112. doi:10.1080/00223891.2018.1504053.

- Liu, Y., and H. Li. 2011. “Exploring the Impact of Use Context on Mobile Hedonic Services Adoption: An Empirical Study on Mobile Gaming in China.” Computers in Human Behavior 27 (2): 890–898. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2010.11.014.

- Martela, F., C. R. DeHaan, and R. M. Ryan. 2016. “On Enhancing and Diminishing Energy Through Psychological Means: Research on Vitality and Depletion from Self-Determination Theory.” In Self-regulation and ego Control, 67–85. Academic Press. doi:10.1016/B978-0-12-801850-7.00004-4.

- McAloon, A. 2017. How Intentionally Frustrating Players can Lead to Better Game Design. https://www.gamasutra.com/view/news/293508/How_intentionally_frustrating_players_can_lead_to_better_game_design.php.

- Mills, D. J., M. Milyavskaya, N. L. Heath, and J. L. Derevensky. 2018a. “Gaming Motivation and Problematic Video Gaming: The Role of Needs Frustration.” European Journal of Social Psychology 48 (4): 551–559. doi:10.1002/ejsp.2343.

- Mills, D. J., M. Milyavskaya, J. Mettler, and N. L. Heath. 2018c. “Exploring the Pull and Push Underlying Problem Video Game use: A Self-determination Theory Approach.” Personality and Individual Differences 135: 176–181. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2018.07.007.

- Mills, D. J., M. Milyavskaya, J. Mettler, N. L. Heath, and J. L. Derevensky. 2018b. “How Do Passion for Video Games and Needs Frustration Explain Time Spent Gaming?” British Journal of Social Psychology 57 (2): 461–481. doi:10.1111/bjso.12239.

- Milyavskaya, M., and R. Koestner. 2011. “Psychological Needs, Motivation, and Well-being: A Test of Self-determination Theory Across Multiple Domains.” Personality and Individual Differences 50 (3): 387–391. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2010.10.029.

- Montola, M. 2010. The Positive Negative Experience in Extreme Role-Playing. The Foundation Stone of Nordic Larp, 153. http://www.digra.org/digital-library/publications/the-positive-negative-experience-in-extreme-role-playing/.

- Mora-Cantallops, M., and MÁ Sicilia. 2018. “Exploring Player Experience in Ranked League of Legends.” Behaviour & Information Technology 37 (12): 1224–1236. doi:10.1080/0144929X.2018.1492631.

- Ninja Theory. 2017. Hellblade: Senua's Sacrifice. Cambridge: Ninja Theory.

- Oliver, M. B., N. D. Bowman, J. K. Woolley, R. Rogers, B. I. Sherrick, and M. Y. Chung. 2016. “Video Games as Meaningful Entertainment Experiences.” Psychology of Popular Media Culture 5 (4): 390–405. doi:10.1037/ppm0000066.

- Phan, M. H., J. R. Keebler, and B. S. Chaparro. 2016. “The Development and Validation of the Game User Experience Satisfaction Scale (GUESS).” Human Factors: The Journal of the Human Factors and Ergonomics Society 58 (8): 1217–1247. doi:10.1177/0018720816669646.

- Przybylski, A. K., C. S. Rigby, and R. M. Ryan. 2010. “A Motivational Model of Video Game Engagement.” Review of General Psychology 14 (2): 154–166. doi:10.1037/a0019440.

- Przybylski, A. K., N. Weinstein, R. M. Ryan, and C. S. Rigby. 2009. “Having to Versus Wanting to Play: Background and Consequences of Harmonious Versus Obsessive Engagement in Video Games.” CyberPsychology & Behavior 12 (5): 485–492. doi:10.1089/cpb.2009.0083.

- Rapp, A. 2020. “An Exploration of World of Warcraft for the Gamification of Virtual Organizations.” Electronic Commerce Research and Applications 42: 100985. doi:10.1016/j.elerap.2020.100985.

- Red Hook Studios. 2016. Darkest Dungeon. Vancouver: Merge Games.

- Reis, H. T., K. M. Sheldon, S. L. Gable, J. Roscoe, and R. M. Ryan. 2000. “Daily Well-being: the Role of Autonomy, Competence, and Relatedness.” Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin 26 (4): 419–435. doi:10.1177/0146167200266002.

- Rieger, D., L. Reinecke, L. Frischlich, and G. Bente. 2014. “Media Entertainment and Well-being-linking Hedonic and Eudaimonic Entertainment Experience to Media-induced Recovery and Vitality.” Journal of Communication 64 (3): 456–478. doi:10.1111/jcom.12097.

- Rigby, S., and R. Ryan. 2007. The Player Experience Of Need Satisfaction (PENS) Model. Immersyve Inc, 1–22. https://natronbaxter.com/wp-content/uploads/2010/05/PENS_Sept07.pdf.

- Rigby, S., and R. M. Ryan. 2011. Glued to Games: How Video Games Draw us in and Hold us Spellbound: How Video Games Draw us in and Hold us Spellbound. Santa Barbara, CA: AbC-CLIo.

- Ryan, R. M. 1995. “Psychological Needs and the Facilitation of Integrative Processes.” Journal of Personality 63: 397–427. doi:10.1111/j.1467-6494.1995.tb00501.x.

- Ryan, R. M., and E. L. Deci. 2000. “The Darker and Brighter Sides of Human Existence: Basic Psychological Needs as a Unifying Concept.” Psychological Inquiry 11 (4): 319–338. doi:10.1207/S15327965PLI1104_03.

- Ryan, R. M., and E. L. Deci. 2017. Self-determination Theory: Basic Psychological Needs in Motivation, Development, and Wellness. New York: Guilford Publications.

- Ryan, R. M., and C. Frederick. 1997. “On Energy, Personality, and Health: Subjective Vitality as a Dynamic Reflection of Well-being.” Journal of Personality 65 (3): 529–565. doi:10.1111/j.1467-6494.1997.tb00326.x.

- Ryan, R. M., C. S. Rigby, and A. Przybylski. 2006. “The Motivational Pull of Video Games: A Self-determination Theory Approach.” Motivation and Emotion 30 (4): 344–360. doi:10.1007/s11031-006-9051-8.

- Scerri, M., A. Anderson, V. Stavropoulos, and E. Hu. 2019. “Need Fulfilment and Internet Gaming Disorder: A Preliminary Integrative Model.” Addictive Behaviors Reports 9: 100144. doi:10.1016/j.abrep.2018.100144.

- Sheldon, K. M., A. J. Elliot, R. M. Ryan, V. Chirkov, Y. Kim, C. Wu, D. Meliksah, and Z. Sun. 2004. “Self-concordance and Subjective Well-being in Four Cultures.” Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology 35 (2): 209–223. doi:10.1177/0022022103262245.

- Sheldon, K. M., and J. C. Hilpert. 2012. “The Balanced Measure of Psychological Needs (BMPN) Scale: An Alternative Domain General Measure of Need Satisfaction.” Motivation and Emotion 36 (4): 439–451. doi:10.1007/s11031-012-9279-4.

- Sherry, J. L. 2004. “Flow and Media Enjoyment.” Communication Theory 14 (4): 328–347. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2885.2004.tb00318.x.

- Stebbings, J., I. M. Taylor, C. M. Spray, and N. Ntoumanis. 2012. “Antecedents of Perceived Coach Interpersonal Behaviors: The Coaching Environment and Coach Psychological Well- and Ill-being.” Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology 34 (4): 481–502. doi:10.1123/jsep.34.4.481.

- Sweetser, P., and P. Wyeth. 2005. “GameFlow: A Model for Evaluating Player Enjoyment in Games.” Computers in Entertainment 3 (3): 3–3. doi:10.1145/1077246.1077253.

- Tóth-Király, I., B. Bőthe, A. N. Márki, A. Rigó, and G. Orosz. 2019. “Two Sides of the Same Coin: The Differentiating Role of Need Satisfaction and Frustration in Passion for Screen-based Activities.” European Journal of Social Psychology 49 (6): 1190–1205. doi:10.1002/ejsp.2588.

- Uysal, A. 2016. “Commitment to Multiplayer Online Games: An Investment Model Approach.” Computers in Human Behavior 61: 357–363. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2016.03.028.

- Vanhee, G., G. Lemmens, and L. L. Verhofstadt. 2016. “Relationship Satisfaction: High Need Satisfaction or Low Need Frustration?” Social Behavior and Personality: an International Journal 44 (6): 923–930. doi:10.2224/sbp.2016.44.6.923.

- Vansteenkiste, M., and R. M. Ryan. 2013. “On Psychological Growth and Vulnerability: Basic Psychological Need Satisfaction and Need Frustration as a Unifying Principle.” Journal of Psychotherapy Integration 23 (3): 263. doi:10.1037/a0032359.

- Vella, K., D. Johnson, and L. Hides. 2013. “Positively Playful: When Videogames Lead to Player Wellbeing.” In Proceedings of the First International Conference on Gameful Design, Research, and Applications, 99–102. ACM. doi:10.1145/2583008.2583024.

- Vella, K., D. Johnson, and L. Hides. 2015. “Playing Alone, Playing with Others: Differences in Player Experience and Indicators of Wellbeing.” In Proceedings of the 2015 Annual Symposium On Computer-Human Interaction in Play, 3–12. ACM. doi:10.1145/2793107.2793118.

- Wan, C. S., and W. B. Chiou. 2006. “Psychological Motives and Online Games Addiction: A Test of Flow Theory and Humanistic Needs Theory for Taiwanese Adolescents.” CyberPsychology & Behavior 9 (3): 317–324. doi:10.1089/cpb.2006.9.317.

- Wang, C., H. C. K. Hsu, E. M. Bonem, J. D. Moss, S. Yu, D. B. Nelson, and C. Levesque-Bristol. 2019. “Need Satisfaction and Need Dissatisfaction: A Comparative Study of Online and Face-to-Face Learning Contexts.” Computers in Human Behavior 95: 114–125. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2019.01.034.

- Warburton, V. E., J. C. Wang, K. J. Bartholomew, R. L. Tuff, and K. C. Bishop. 2020. “Need Satisfaction and Need Frustration as Distinct and Potentially Co-occurring Constructs: Need Profiles Examined in Physical Education and Sport.” Motivation and Emotion, 44, 54–66.

- Whitby, M. A., C. S. Deterding, and I. Iacovides. 2019. “‘One of the Baddies All Along’: Moments that Challenge a Player’s Perspective.” In CHI PLAY 2019. ACM. doi:10.1145/3311350.3347192.

- Xu, Z., O. Turel, and Y. Yuan. 2012. “Online Game Addiction among Adolescents: Motivation and Prevention Factors.” European Journal of Information Systems 21 (3): 321–340. doi:10.1057/ejis.2011.56.