ABSTRACT

This study addresses the question to which extent individual online self-presentations become more similar globally, due globalisation and digitalisation, or whether ethno-racial identity predisposes individuals’ online self-presentation. That is, we examined the degree to which individuals varying in ethno-racial identity converge or diverge in online self-presentation. A large-scale content analysis was conducted by collecting selfies on Instagram (i.e. #selfietime; N = 3881). Using facial recognition software, selfies were allotted into a specific ethno-racial identity based on race/ethnicity-related appearance features (e.g. Asian, Black, Hispanic, and White identity) as a proxy for externally imposed ethno-racial identity. Results provided some evidence for convergence in online self-construction among selfie-takers, but generally revealed that self-presentations diverge as a function of ethno-racial identity. That is, results showed more convergence between ethno-racial identity for portraying selfies with objectified elements, whereas divergence in online self-presentations occurred for portraying contextualised selves and filter usage. In all, this study examined the complexity of online self-presentation. Here, we extend earlier cross-cultural research by exploring the convergence-divergence paradigm for the role of externally imposed ethno-racial identity in online self-presentation. Findings imply that ethno-racial identity characteristics remain important in manifestations of online self-presentations.

Photo-sharing based Social Networking Sites (SNSs), such as Instagram, have become increasingly popular over the past few years. With a total of approximately one billion active users, Instagram is currently one of the most popular SNSs (Statista Citation2022). Instagram is particularly based on (appearance-focused) visuals, and, therefore, highly popular for sharing photos of oneself (Lee and Sung Citation2016). A widely used approach to construct the self on SNSs nowadays, is posting selfies, being pictures of oneself, taken by oneself (Qiu et al. Citation2015). Via such visual self-presentations, clearly visible identity characteristics, as gender and race, become much more prominent than in textual self-presentations (Kapidzic and Herring Citation2011, Citation2015; Utter et al. Citation2020). Such identity characteristics guide online self-presentations, resulting in differences in self-presentations among individuals (Kapidzic and Herring Citation2011, Citation2015; Utter et al. Citation2020). For example, regarding gender, females post more group selfies than males and they tend to replicate feminine ideals as portrayed in mass media in their selfies (Butkowski et al. Citation2020; Sorokowska et al. Citation2016).

Exploring factors that predispose online self-presentation, so-called (social) media creation, helps to further our understandings of differential susceptibility in media engagement (cf. Valkenburg and Peter Citation2013). Currently, there are many relatively unexplored factors to unravel individual differences in the construction of online self-presentations. That is, whereas gender as identity characteristic has been examined quite extensively in self-presentation and social media research (e.g. Butkowski et al. Citation2020; Sorokowska et al. Citation2016; Twenge and Farley Citation2021), research examining ethno-racial identity in relation to visual self-presentation research is scarce. Nevertheless, there is supporting evidence that ethno-racial identity plays a role in constructing online self-presentations. For example, individuals identified as White display more seductive behaviours online than individuals identified as Black, where particularly White boys exposed more seductive behaviours than Black boys (Kapidzic and Herring Citation2015). Another example comes from selfies that can be used to highlight culture-specific characteristics. For example, several studies revealed that individuals identifying as Black or African-American report motivations for posting selfies such as to identify with others like them, or see selfies as a positive way to present unique characteristics of their race to others as manifested by, for example, hair, clothes, and tattoos (Barker and Rodriguez Citation2019; Williams and Marquez Citation2015).

Due to digitalisation, an emerging question is whether today’s social media saturated environments incite globalisation of the online construction of self-presentation. That is, the extent to which ethno-racial identity contributes to individuals’ online self-presentation, relative to the extent to which online self-presentations become more similar to one another despite differences in ethno-racial identities. Differences in self-presentation are expected from adherence to body image norms or cultural-historical group norms that are consistent with one’s own ethno-racial identity (i.e. divergence; cf. Grasmuck, Martin, and Zhao Citation2009). Previous research showed that individuals adhere to body image norms and cultural-historical norms that are consistent with their own ethno-racial identity (Barker Citation2019; Kapidzic and Herring Citation2015). In contrast, similarities in self-presentation are expected from the dominance of Western White ideals (i.e. globalisation) and changing norms for individuals that grew up with media (i.e. convergence; cf. Hynes Citation2021; Liu, Wang, and Liu Citation2018; Twenge Citation2014). For example, a more recent study found that individuals stemming from different parts of the world converged in their perceptions of self-disclosure (Liu, Wang, and Liu Citation2018). Therefore, the current study examined how individuals varying in externally imposed ethno-racial identity present themselves similarly or differently online. Following Kapidzic and Herring (Citation2015), we particularly focus on externally imposed ethno-racial identity based on physical features in terms of Asian, Black, Hispanic, and White racial and ethnic identities.

1.1. Convergence and divergence in online self-presentation

Via visual self-presentations online, such as posting selfies, individuals can manifest various identity characteristics, such as gender identity and ethno-racial identity (Barker and Rodriguez Citation2019). Research into ethno-racial identity and self-presentation is sparse, which might be due to the sensitivity and controversy of the topic, as classification into ethno-racial categories can form a basis for discrimination (Feliciano Citation2016). We, therefore, want to emphasize that this study is by no means intended to classify individuals into categories as input for discrimination, rather, we aim to group individuals to examine patterns that seem important in unravelling the complexity of online identity expression. In the current study, we examined the convergence-divergence paradigm by focusing on differences and similarities in online self-presentations among varying externally software imposed ethno-racial identities. On the one hand, previous research indicated that convergence in self-presentations is expected from changing norms due globalisation and digitalisation (Jenkins Citation2006; Liu, Wang, and Liu Citation2018). On the other hand, it is argued that offline values pertaining to sociocultural norms and ethno-racial identity are transferred to online self-presentation, leading to divergence in self-presentation (e.g. Grasmuck, Martin, and Zhao Citation2009; Huang and Park Citation2013; Kapidzic and Herring Citation2011, Citation2015; Zheng et al. Citation2016).

The current study builds upon cross-cultural research, which examined national identities, showing that both divergence and convergence occurred. Supporting divergence, multiple studies found that varying national identities resulted in differences in self-presentation (Huang and Park Citation2013; Kim and Papacharissi Citation2003; Lee-Won et al. Citation2014; Rui and Stefanone Citation2013; Wang and Liu Citation2019). For example, East Asian individuals were more likely to deemphasize their faces on Facebook photos compared to Americans (Huang and Park Citation2013). Hence, results marked cultural differences in their preference for context-inclusive self-presentation compared to more self-focused self-presentation, and thus led to divergence in online self-presentations. Similar to national identity, there is supporting evidence that ethno-racial identity characteristics also resulted in differences in self-presentation. Results of various studies showed that individuals varying in ethno-racial identity have different self-presentation preferences, be it in terms of (a) the number of selfies posted (Williams and Marquez Citation2015); (b) posting objectified selves (Hall, West, and McIntyre Citation2012); or gaze, posture, dress, and distance from the camera (Kapidzic and Herring Citation2015). Previous research argues that these differences are due to (socio)cultural dominant ideologies of race or ethnicity in terms of body and beauty ideals (Kapidzic and Herring Citation2015; Veldhuis Citation2020).

Next to the global dominance of Western White appearance ideals, the rise of user-generated platforms also led to a diversification of audiences (Odağ and Hanke Citation2019). From a sociocultural examination, racial and ethnic groups seem to be particularly conflicted between either adhering to the globalised Western ideal or conform to their in-group unique characteristics of body and beauty ideals (cf. Watson, Lewis, and Moody Citation2019). Adherence to Western ideals, for example, internalising White culture body ideals such as fit- and thin-ideal, light skin, and long blond hair, may stem from a mode of coping or avoiding further oppression as developed historically over time (cf. Awad et al. Citation2015; Glasser, Robnett, and Feliciano Citation2009; Mingoia et al. Citation2017). However, ethno-racial groups also have their unique beauty ideals. For example, a curvier body-type is perceived as ideal in Black cultures as well as appreciation of other specific ethno-racial features such as lip size, hair grade, and nose shape (e.g. Awad et al. Citation2015; Glasser, Robnett, and Feliciano Citation2009; Winter et al. Citation2019). Hispanic ideologies of body and beauty ideals generally value curvy bodies, large brests, and rounded derrieres (Schooler and Lowry Citation2011). Contrary, a slim body and facial aestethics, such as skin tone (i.e. white skin) and facial shape (i.e. oval and heart shapes), are prominent features of Asian beauty ideals (cf. Jung Citation2018; Samizadeh and Wu Citation2018). Nevertheless, it should also be noted that across cultures characteristics such as facial symmetry are features of perceived beauty (Prokopakis et al. Citation2013), and body and beauty ideals may gradually change over time (e.g. Jung Citation2018; Yip, Ainsworth, and Hugh Citation2019). In all, a sociocultural approach of apperance-standards and body-ideals reveals two contrasting lines of argumentation: On the one hand, globalisation and exposure to dominant Western ideals can lead to internalisation and consequently result in a Western monoculture (cf. Hynes Citation2021), on the other hand, unique culturally dominant ideologies of race and ethnicity can lead to adaption of differential standards in self-presenatations (cf. Watson, Lewis, and Moody Citation2019).

Differences in self-presentation among individuals varying in ethno-racial identity can be further explained via Social Identity Theory (SIT; Tajfel Citation1978; Tajfel and Turner Citation1979) According to SIT, behaviour and cognitions can be explained via group processes. A social group is characterised by a number of people who indicate to be part of that group, as well as externally imposed placement in a group by others (Tajfel and Turner Citation1979; Trepte and Loy Citation2017). Belongingness and feelings of being connected based on race is perceived to be a significant social category for individuals to classify themselves, also referred to as self-categorisation (Gecas Citation2000; Trepte and Loy Citation2017). Via self-categorisation, the norms and values expressed by a that in-group tend to be embraced and internalised (Turner Citation2010). For instance, consistent with their own culturally dominant ethno-racial identity, adherence to the thin ideal was stronger for White women than for Black women (Fujioka et al. Citation2009). More specifically, African Americans with a stronger adherence to their own ethnic group with its unique beauty ideals were less likely to internalise Western beauty ideals (cf. Rogers Wood and Petrie Citation2010; Watson, Lewis, and Moody Citation2019). SIT puts forward that individuals aim to achieve or maintain a positive social identity, and do so via social comparison to similar groups to establish a positive distinctiveness from their own in-group compared to other out-groups (Turner and Reynolds Citation2010). In all, following reasoning of culturally-dominant ideologies and SIT, differences in self-presentation among individuals varying in ethno-racial identity were expected (i.e. divergence).

However, a recent study examining national cultures did not find divergence, but rather convergence (Liu, Wang, and Liu Citation2018). They found that individuals from different cultures actually converged in their online self-disclosure intentions. This presumption of converging culture argues that the stream of media and media usage can shift cultural norms (Jenkins Citation2006). Luppicini (Citation2013) argues that digital technologies are highly embedded in daily life. Especially, individuals who grew up with new technologies, so-called ‘digital natives’, would be fluent in using new technologies and more self-expressive than other generations (Prensky Citation2001; Taylor and Keeter Citation2010). Due to digitalisation, individuals are assumed to be a more homogenised group who put the individual first and follow more self-centered and individualised standards (Twenge Citation2014). This shift in norms can be further underpinned via the Technoself studies (TSS; Luppicini Citation2013). Research into the so-called technoself suggests that the way in which individuals’ self-construct is developed, is dependent upon the technological affordances at hand. Even though Instagram offers various ways of how individuals can present themselves, the affordances of the platform and the accompanying editing features are similar for all users, possibly resulting in homogenisation of media content. Particularly, the overall adherence to the White culture Western ideal is argued to be one of the reasons why more recent studies found less evidence for Black–White differences in body image concerns (Watson, Lewis, and Moody Citation2019). Also among other ethnic and racial groups, such as Hispanic and Asian populations, pressure to acculturate to Western beauty ideals leads to internalisation of those Western ideals (Chin Evans and McConnell Citation2003; Menon and Harter Citation2012).

These theoretical assumptions, however, are not bounded to the digital environment. Earlier studies have already stressed that, due to globalisation and the creation of more homogenising images presented in mass media around the world, similar evaluations of idealised body imagery cross-culturally occur (Chia Citation2009; Grabe, Ward, and Hyde Citation2008). In terms of new media, the large American and Western-based social media platforms, such as Instagram, are significant players in the global media landscape moving towards a norm largely based on Western ideals (Hynes Citation2021). The global dominance of Instagram has the ability to create homogenisation of images representing specific trends. For example, social media content is dominated by positive user-generated content generally showing how happy they are and how good their lives are, known as the positivity bias (Michikyan, Subrahmanyam, and Dennis Citation2015; Schreurs and Vandenbosch Citation2022). Additionally, individuals largely follow trends online such as the selfie-craze (Lee and Sung Citation2016), where individuals’ behaviours converge in following trends such as pose preferences (i.e. presenting face-only) and primarily posting good-looking photos only (Batool and Saleem Citation2018; Bij de Vaate et al. Citation2018; Siibak Citation2009). In all, following reasoning of changing norms due to globalisation and use of digital affordances, similarities in self-presentation among individuals varying in ethno-racial identity were expected (i.e. convergence).

The above discussed two opposing lines of divergence versus convergence drive the question to which extent online self-presentation strategies converge or diverge as a function of ethno-racial identity. The current research extends earlier cross-cultural research in national identities, by exploring the convergence-divergence paradigm for the role of ethno-racial identity in online self-presentation construction. Studies including national identity often apply Hofstede’s cultural paradigm to study visual online self-presentations (Kim and Papacharissi Citation2003; Liu, Wang, and Liu Citation2018; Rui and Stefanone Citation2013; Wang and Liu Citation2019). Hofstede is a well-known source for deriving cultural dimensions from national identity (Hofstede Citation2001). Out of seven, the collectivism/individualism dimension is most studied (cf. Gudykunst Citation1997).

In studying self-presentation, cross-cultural research thus far has mainly focused on the dimensions of individualism-collectivism and uncertainty avoidance (Bij de Vaate, Veldhuis, and Konijn Citation2020; Liu, Wang, and Liu Citation2018; Rui and Stefanone Citation2013). The individualism-collectivism approach provides a theoretical basis for understanding the extent to which individuals pertain to more individualistic standards online. In explaining such individualisation, digitalisation studies argue that individuals become more individualised, self-focused and self-expressive. Also, from a sociocultural perspective, the large dominance of Western media culture could lead to a move towards a monoculture based on Western White ideals (Hynes Citation2021). Here, Western White cultures are typically classified as having individualistic norms, whereas Asian, Hispanic, and Black cultures score higher on collectivistic values (Cox, Lobel, and McLeod Citation1991; Gudykunst Citation2004; Hofstede Citation2001). Individualism is characterised by individuals who see themselves as independent from others and are more autonomous and more self-focused (cf. Gudykunst Citation1997; Hofstede Citation2001; Markus and Kitayama Citation1991; Triandis Citation2001). As such, from these individualistic standards, individuals are motivated to strive for self-enhancement and prioritise personal goals over the goals of others. In contrast, collectivism is characterised by being interdependent of others, being closely linked to individuals who consider themselves as part of a collective, and placing more emphasis on the social context (cf. Gudykunst Citation1997; Hofstede Citation2001; Markus and Kitayama Citation1991; Triandis Citation2001). Collectivistic standards thus follow in-group norms and values, prioritise collective goals over individual goals, and emphasize their interconnectedness with others. Following the convergence hypothesis, digitalisation might lead individuals to become a more homogeneous group that are more self-focused and follow more individualised standards compared to following collectivistic in-group norms that would indicate divergence (cf. Twenge Citation2014). In relating the above reasoning to online self-presentations specifically, we derived the following aspects to include in our study.

First, this study analyzed the degree of context inclusiveness. Individualistic and collectivistic norms differ in respect to prioritising context inclusiveness in self-presentation (cf. Huang and Park Citation2013; Markus and Kitayama Citation1991; Masuda et al. Citation2008). For example, in examining perceptions of online images different cognitive processes may occur. In line with individualistic norms, individuals can primarily process images by primarily paying attention to the portrayed focal object. Such attention is used as information to categorise and understand the image. Contrary, following collectivistic norms, individuals jointly process the portrayed object as well as its context, which results in more holistic information processing that also includes context (Nisbett et al. Citation2001; Nisbett and Masuda Citation2003). Such context-inclusive style vs. object-focus style is shown in profile pictures where collectivistic and interdependent self-presentations deemphasize their faces with more room for background compared to individualistic and independent self-presentations (Huang and Park Citation2013). Thus, interdependent self-presentations prioritise context inclusiveness, whereas independent self-presentations prioritise the focal figure. This study applies this paradigm by evaluating whether an individual presented more of oneself versus presenting more context (i.e. background) in the selfie (e.g. face-frame ratio). Additionally, fundamental to individualism-collectivism cultural norms is the relatedness of individuals to each other. It was argued that collectivism constrains individuals to solely present themselves (Guo Citation2015; Hai-Jew Citation2017). In the current study, we examine this interconnectedness with others via posting selfies with a more individual focus versus a more social inclusive focus through selfies with others. Hence, we focus on two types of contextualisation: (1) context inclusiveness (i.e. prioritising background of the photo vs. prioritising the focal figure); (2) social inclusiveness (i.e. visibility of interdependence with others).

Second, it is argued that individualistic-oriented individuals are more active in strategic management of public impressions compared to their collectivistic-oriented counterparts (Rui and Stefanone Citation2013). On Instagram, built-in tools for photo-manipulation can be used to adjust selfie-appearance once the photo is taken, such as the use of filers (McLean et al. Citation2015). Gonzales and Hancock (Citation2011) argue that self-presentations can be optimised via strategic identity construction such as photo-manipulation, rendering photo-manipulation as a form of self-enhancement. Following individualistic standards, the online affordances of selective online self-presentation allow individuals to acculturate the White ideals, which may lead to convergence in using filters in online self-presentations. Contrary, following in-group norms and adherence to one’s own racial identify and ethnic group, the diversification of online audiences and a wider variety of ideals could coincide with discrepant filter use.

Third, the current study includes ‘elements of self-objectification’. Both traditional and new media often depict sexually objectified bodies which prevails in Western societies (cf. Baldissarri et al. Citation2019). Reducing individual characteristics to body features and sexual function could subsequently cause adaptation of an outsider’s perspective of their body and engagement in self-objectification (Fredrickson and Roberts Citation1997). Self-objectification can behaviourally be manifested in several ways, for example, by individuals showing increased body surveillance or manifestations of objectified elements in images (i.e. specific body parts being the main focus of the image; Tiggemann and Zaccardo Citation2016). Behavioural manifestations of objectification elements vary depending on, amongst others, demographic factors such as culture and race (Fredrickson and Roberts Citation1997; Watson, Lewis, and Moody Citation2019). Previous research argued that Western beauty ideals include more sexualised images than East Asian beauty ideals (Frith, Shaw, and Cheng Citation2005), and results of a content analysis of MySpace photos revealed that Blacks and Hispanics portrayed more objectified selves compared to Whites (Hall, West, and McIntyre Citation2012). Moreover, findings from a more recent cross-sectional study also provide evidence that individuals from different racial and ethnic groups vary in their experienced levels of self-objectification, where Black women reported lower levels of self-surveillance compared to White women (Schaefer et al. Citation2018). As such, based on previous research, following collective norms in online self-presentations would then diverge. Hence, this study includes objectification principles to examine if individuals varying in ethno-racial identity display more or less objectified elements in their selfies, either resulting in convergence or divergence in self-presentations.

Lastly, in addition to aspects of the individualism-collectivism dimension, we included additional self-presentation characteristics to allow for further comparison between ethno-racial identities in how they profile their self-presentation strategies, based on previous research profiling selfie-takers (Batool and Saleem Citation2018; Bij de Vaate et al. Citation2018; Meier and Gray Citation2014). These self-presentation characteristics include use of typical facial expressions e.g. duck face, fish gape, smile; as previously studied by Batool and Saleem (Citation2018), the amount of body parts visible in the selfie (e.g. face only, face till hips), and use of tools to take the selfie e.g. selfie-stick, mirror, as previously studied by Bij de Vaate et al. (Citation2018) and Meier and Gray (Citation2014). In further profiling those who post selfies online, we explore possible gender differences in selfie-posting among ethno-racial groups. Previous studies indicate that women typically post more selfies than men, regardless of their ethno-racial identity (Barker and Rodriguez Citation2019; Bij de Vaate et al. Citation2018). Hence, we aim to explore such prevalence of gender differences in a real-life environment instead of being derived from self-report data. Lastly, to provide a detailed mapping of selfie-characteristics into a broader social media context, we also include descriptive statistics on peer feedback (i.e. likes and comments) and location tagging. By including these selfie-features, next to the individualistic and collectivistic aspects, we can examine how self-presentation characteristics may or may not vary between individuals from different ethno-racial identities. Thus, the above reasoning led to two research questions:

RQ1: How do individuals varying in ethno-racial identity (i.e. Asian, Black, Hispanic, and White) present themselves online in terms of various self-presentation features such as portraying selfies with contextualization, presentation filter usage, objectification elements, and specific self-presentation characteristics (i.e. gender, peer feedback, location-tagging)?

RQ2: In comparing individuals varying in ethno-racial identity (i.e. Asian, Black, Hispanic, and White), to what extent do they converge (i.e. show similarities) or diverge (i.e. show differences) in terms of (a) contextualization; (b) filter usage; and (c) objectification elements?

2. Method

This section first elaborates on the image selection of this study, then we discuss the coding procedure and coding reliabilities. Finally, details of the operationalisation of the variables are described.

2.1. Image selection

Upon ethical approval by the Institutional Ethical Review Board, data collection started. This study aimed to capture a large sample that included publicly available selfies posted on Instagram (i.e. self-presentations that were posted to a wider community). Hence, we started with the hashtag that included the most selfie posts, #selfie. This hashtag, however, resulted in an enormous amount of selfies, leaving us unable to accurately retrieve all selfies posted within a given day, which could subsequently lead to possible misrepresentations of the data. Therefore, we continued with the hashtag with the second largest stream of selfie posts, #selfietime. With this hashtag we were able to capture all posted photos that were posted within the period from April 4th to April 17th, 2018, allowing for representative data. The URL to the specific Instagram pages, including the photos, were saved for analyses. In total, 70,000 photos were collected.

Seven independent coders were trained to apply the same coding criteria (see ‘coding reliability’ below). Thereafter, seven random samples of 1000 photos were drawn from the total of collected photos, where each coder coded a subset of 1000 photos independently. Combined with the final round of coding reliability (n = 200) this resulted in an initial dataset consisting of 7200 photos. After removal of (1) duplicate photos; (2) photos that were coded as not a selfie; and (3) selfie-takers that were not clearly visible, the final dataset consisted of 5014 photos (dataset and codebook are available via OSF: https://osf.io/3hbpm/). Facial recognition softwareFootnote1 was used to classify ethno-racial identity in terms of facial images being classified into having Asian, Black, Hispanic, White, or other appearance features. This software could sometimes not detect a face in the sampled photos and, therefore, not each selfie could be allocated to a specific ethno-racial identity, leaving 3381 selfies for analyses. Of the faces portrayed in the selfies 65.5% (n = 2543) were identified as White, 17.4% (n = 676) as Asian, 12.5% (n = 484) as Hispanic, and 4.6% (n = 178) as Black. Of these, 3367 were single-person selfies, and 514 were group selfies.

2.2. Coding procedure

A detailed coding scheme to rate the selfies collected was developed. First, the metadata of the photos were included in the scheme, pertaining to, for example, likes, comments, and location. Then, the coding scheme included whether the collected image could actually be coded as a selfie. Subsequently, the number of persons in the selfie was determined. Selfies featuring just one person were rated as single-person selfies, and subsequently processed following the coding scheme for single selfies, whereas selfies featuring multiple persons (i.e. including photos with more than one person portrayed), were processed following the coding scheme for group selfies.

For single-person selfies, coders determined the perceived gender of the person in the selfies. For group selfies, coders only reported on the gender of the person that was making the selfie (i.e. by applying strict criteria, such as there is an arm holding the camera or the selfie stick is visible). Then, for both single-person selfies as well as selfies with multiple persons, the coders uploaded the images to the facial recognition website to determine ethno-racial identity and age of the selfie-taker. The next questions all pertained to the selfie-taker of the individual selfie or group selfie. Following the coding scheme, coders classified whether the individuals showed typical facial expressionsFootnote2, while also filter-use and use of special equipment to take the selfie were rated. Lastly, self-objectification was measured as well as the ratio between the individual and context present in the picture.

2.3. Coding reliability

The seven independent coders were trained by the researcher for three hours to familiarise them with the coding scheme and allow them to practice with some trial photos, a total of 9.4% of the final set of images used in the study. After the initial training, they rated a first small sample of 60 images to further check for any deficiencies in the coding scheme. In this first trial, several variables did not reach sufficient intercoder reliability estimates, indicating that further adjustment was needed (Krippendorff’s alpha > .667; S-Lotus > .67, Fretwurst Citation2015; Krippendorff Citation2004). To increase levels of agreement, the coding scheme was adjusted by eliminating specific categories or combining specific categories. The seven coders rated an additional sample of 400 images with this adjusted coding scheme. However, the levels of agreement on some variables were still not sufficient, leading the variable referring to portraying sexualised selves being removed. Coding for other insufficient variables was further tightened by providing a stricter description or elimination/combining coding categories. Finally, the coders used this scheme to rate a last sample of 200 images, determining the intercoder reliability of this study’s variables. describes the percentages of agreement, Krippendorff’s alpha and S-Lotus. These 200 collectively coded images were added to the total of 7000 images that were individually coded, resulting in the study’s total sample of 7200 images.

Table 1. Intercoder reliability estimates of coded variables for individual selfies.

2.4. Operationalisation

This section describes the software that was used to determine ethno-racial identity, the metadata accompanying the Instagram photos, and the variables coded by the independent coders.

Ethno-racial identity. Facial recognition software was used to allot individuals to a specific ethno-racial identity, via race/ethnicity-related appearance features. Individuals were allotted to one of five categories (i.e. Asian, Black, Hispanic, White, and other). In considering the nuances of applying appearance features to determine specific ethno-racial identities, the software applies scores between 0 and 1 for all categories. From there, for the scope of this study, individuals adhered to the category with the highest score. To verify the functioning of machine learning software as a valid measure of estimating ethno-racial identity based on physical appearance, we have calculated an intercoder reliability with manual coding of ethno-racial identity. With a Krippendorff’s alpha of .88, externally imposed ethno-racial identity was deemed sufficient. As only one of the selfie-takers was classified as ‘other’, this image was omitted for further analyses.

Metadata. The URL to the specific Instagram photos provided underlying data from which the number of likes and number of comments accompanying the selfies were reported. Moreover, coders used the metadata to report the caption of the photo, the tags attributed to the photo, and (if present) the location where the selfie was taken. These metadata provide more descriptive information about the acquired selfies.

Contextualisation. The degree of contextualisation of the selfie-taker was measured with two variables: (1) the face-frame ratio (i.e. context inclusiveness) and (2) the number of persons in the selfie (i.e. social inclusiveness). First, the face-frame ratio was used to determine the amount of context versus the amount of the selfie-taker that was portrayed in the selfie (Huang and Park Citation2013; Masuda et al. Citation2008). For the face area, we measured the height and width of the face. Height was measured from the top of the head (including hair and hat) to the bottom of the head (chin). Width was determined by measuring the widest part of the face that was visible in the selfie (including hair). The surface of the entire image was measured by the height*width of the image. Then, the specific face-frame ratio was determined by dividing the surface of the face by the surface of the entire image. Via collaborative discussion throughout the various rounds of coding reliability, we created consensus on this measurement (see online material on OSF for an illustration of the measurement; https://osf.io/3hbpm/).

Second, the number of persons in the selfie was determined by counting how many persons were visible in the selfie. Note that passers-by in the background were not counted in selfies with multiple persons. The actual number of persons was counted up until 10 persons; if more than 10 persons were portrayed in the selfie, the exact number was not further counted but referred to as >10 (i.e. clearly indicating a large group-selfie). This variable was used to indicate whether the focus was on the individual or on the social context.

Filter usage. The use of clearly visible filters in the selfie was coded to indicate the use of strategic self-presentation (Yes/No). Filters could appear, for instance, as how they are available in snapchat filters.

Self-objectification elements. Ratings for self-objectification were adapted from Carrotte, Prichard, and Lim (Citation2017) and Tiggemann and Zaccardo (Citation2016). Coders interpreted the Instagram image in terms of being an image emphasizing subjects’ buttocks and/or breast/chest (i.e. No objectification elements; Yes, buttocks; Yes, breast/chest; Yes, buttocks and Breast/Chest) and/or belly (Yes/No). From there, the scores of the self-objectification elements were further combined, leading to a picture being categorised as showing (1) no elements of objectification, (2) one element of objectification, (3) two elements of objectification, or (4) all three elements of objectification.

Self-presentation characteristics. Based on earlier research by Batool and Saleem (Citation2018), Bij de Vaate et al. (Citation2018), and Meier and Gray (Citation2014), this study also included some additional self-presentation characteristics to answer RQ1. First, the amount of body parts visible in the selfie was rated (e.g. only face visible, or face till hips). Second, the use of typical facial expressions such as duck face were determined (e.g. duck face appears to be one of the preferences for facial depictions in selfies; Batool and Saleem Citation2018). Lastly, to indicate how a selfie was taken, the use of special tools to take the selfie, such as using a selfie-stick or mirror, was rated.

3. Results

This section reports on the results of this exploratory study examining the differences and similarities in online self-presentation between individuals varying in ethno-racial identity. First, results profiled how individuals, characterised within an externally software imposed ethno-racial identity, present themselves online. Second, statistical analyses are reported on significant differences in self-presentation features of individuals varying in ethno-racial identity.

3.1. Profiling online self-presentation according to ethno-racial identity

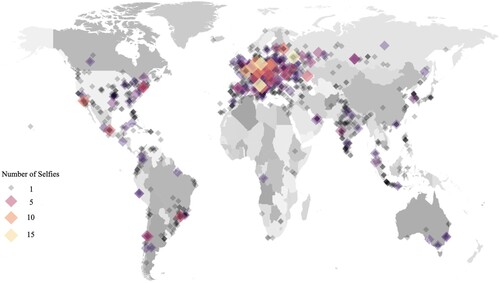

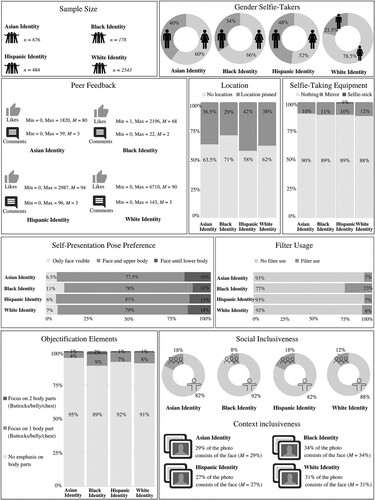

To answer RQ1, we performed descriptive analyses to profile how individuals with different ethno-racial identities express themselves online through selfies. First, by exploring metadata accompanying selfies, this study provided an overview of where selfies are taken by using the location of the selfies which is visualised in . Second, we explored the similarities and differences in the self-presentation features among individuals varying in ethno-racial identity. See for an overview of descriptive analyses per ethno-racial identity. Descriptive findings of the selfies showed that, across all ethno-racial identities, females took more selfies than males. Similarly, across all ethno-racial identities, selfie-takers mostly did not reveal their location. If location was shown, Hispanic selfie-takers did so most often. Regardless the ethno-racial identity they were allotted to, most individuals presented their face and upper body (until hips) via online selfies, rather than face only or full body, however, they rarely portrayed self-objectified selves. Additionally, the selfie-takers hardly used special equipment such as selfie-sticks to take selfies. While the aforementioned self-presentation features of gender, location, self-presentation characteristics, and self-objectification largely overlap for individuals varying in ethno-racial identity, variation in self-presentation features was also found. Strategic self-presentation by using clearly visible filters was most often used by individuals with a Black identity.

3.2. Testing differences in online self-presentation as a function of ethno-racial identity

RQ2a pertained to differences in contextualisation for people varying in ethno-racial identity. This analysis consisted of two measures for such contextualisation: (1) face-frame ratio (i.e. context inclusiveness), and (2) number of persons in the selfie (i.e. social inclusiveness). First, differences in degrees of face-frame ratio and individuals varying in ethno-racial identity were examined. A one-way ANOVA with ethno-racial identity as independent variable and contextualisation in terms of face/frame-ratio as dependent variable showed a significant difference in the degrees of face-frame ratios between the various ethno-racial identities, F(3, 3875) = 10.623, p < .001, d = 0.18, n = 3878. Post hoc analyses (Games-Howell procedure) indicated that Asian selfie-takers scored significantly lower on the face-frame ratio than Black selfie-takers (mean difference = 4.45, p < .05, d = 24) and White selfie-takers (mean difference = 2.15, p < .05, d = 0.12). This means that individuals with Asian ethno-racial identities put less emphasis on the individual face and more emphasis on the background (i.e. context) of the photo, resulting in a lower face-frame ratio than individuals with Black and White ethno-racial identities. Additionally, Hispanic selfie-takers portrayed significantly less of the individual face than Black selfie-takers (mean difference = 6.63, p < .001, d = 0.38) and White selfie-takers (mean difference = 4.32, p = .00, d = 0.24). No significant differences between other groups were found.

Second, differences in the number of people in the selfie were analyzed between the ethno-racial identity groups. Although the assumptions of normality were violated, performing an ANOVA remains a robust measure regardless of normal distribution, sample size, and equal or unequal distribution in groups (Blanca Mena et al., Citation2017).Footnote3 The results of the one-way ANOVA with ethno-racial identity as independent variable and number of persons as the dependent variable, yielded significant differences in the number of persons portrayed in the selfies between individuals varying in ethno-racial identity (F(3, 616.816) = 10.984, p < .001, est. ω2 = .007, n = 3880, Welch Ratio, as the assumption of homogeneity of variance was violated). Further, post hoc analyses using the Games-Howell procedure indicated that Asian and Hispanic selfie-takers posted significantly more group selfies than Black selfie-takers (respectively, mean difference Asian-Black = 0.24, p < .001, d = 0.22 and mean difference Hispanic-Black = 0.21, p < .01, d = 0.22) and White selfie-takers (respectively, mean difference Asian-White = 0.21, p < .001, d = 0.27, mean difference Hispanic-White = 0.18, p < .01, d = 0.28). We found no other evidence of differences between the other ethno-racial identity variations. In sum, the results of this analysis partly align with the notion that differences in ethno-racial identity results in divergence in self-presentation. That is, Asian and Hispanic selfie-takers portrayed more interdependent selves than Black and White selfie-takers.

Then, RQ2b pertained to investigate differences in display of filter usage between individuals varying in ethno-racial identity. A Pearson Chi Square indicated that there was a significant association between different ethno-racial identities and filter usage (χ2(3) = 53.745, p < 0.001; Cramer’s V = 0.118, p < .001, n = 3879). Post hoc comparisons using Bonferroni correction indicated that Black selfie-takers used significantly more filters in their selfies than all other groups. Of the selfies posted by Black selfie-takers, 23% included filter usage, compared to 6.7% for Asian selfie-takers, 6.6% for Hispanic selfie-takers, and 8.3% for White selfie-takers. No other significant differences were found. Underlining the descriptive findings for RQ1, results show that Black selfie-takers diverge in their preference for filter usage compared to the other groups.

For RQ2c, differences in displaying objectified elements among individuals varying in ethno-racial identity were examined. A Pearson Chi Square indicated that there are no significant associations in presenting objectified elements and ethno-racial identities (χ2(9) = 15.594, p > .05; Cramer’s V = 0.037, p > .05, n = 3879). Thus, across all selfie-takers similarities were found in portraying self-objectification in selfies, resulting in convergence in online self-presentation.

4. Discussion

This study aimed to take an exploratory step in examining how individuals varying in externally imposed ethno-racial identity, in terms of Asian, Black, Hispanic, and White ethno-racial identities, present oneself online. First, this study profiled self-presentation strategies among individuals varying in ethno-racial identity. Across all ethno-racial groups, females posted more selfies than males, mainly face and upper body were presented, and selfie-taking tools were barely used. These results align with previous research that profiled self-presentation strategies of selfie-takers (Batool and Saleem Citation2018; Bij de Vaate et al. Citation2018; Sorokowska et al. Citation2016). However, differences were also found, filter usage was most often applied by Black selfie-takers in comparison to the other groups.

Second, this study included two opposing theoretical lines of argumentation either expecting convergence or divergence in self-presentation (Grasmuck, Martin, and Zhao Citation2009; Jenkins Citation2006; Kapidzic and Herring Citation2015; Liu, Wang, and Liu Citation2018). Supporting divergence, findings showed that self-presentation strategies, in terms of contextualisation and filter usage diverged as a function of ethno-racial identity. More specifically, regarding contextualisation, results revealed that Asian and Hispanic selfie-takers displayed more context and less focus on the individual than Black and White selfie-takers. Hence, Black and White self-takers presented themselves in line with individualistic norms, whereas Asian and Hispanic selfie-takers presented themselves along the lines of collectivistic norms (cf. Gudykunst Citation1997; Hofstede Citation2001). Divergent patterns in presenting context-focused vs. object-focused styles may stem from the differential cognitive processing of visuals (cf. Nisbett and Masuda Citation2003): Both Hispanics and Asian individuals are typically embedded in a collectivistic context-inclusive culture, whereas Black selfie-takers in our study adhered more to individualistic object-focused self-presentation, even though it is argued that Black individuals historically have a more collectivistic orientation.

Additionally, results of this study also provide more evidence for the important role of ethno-racial identity regarding presentation filter usage. Findings showed that Black selfie-takers made more use of the digital affordances at hand than the others. These findings especially align with previous notions that students with African American identities invested more in identity construction online than White students (Grasmuck, Martin, and Zhao Citation2009). One of the reasons for Black selfie-takers to engage more in filter usage might reside in the heightened awareness of one’s ethno-racial identity to present positive and unique aspects of one’s own culture, and reflect some sort of resistance to the dominant ideologies of Western culture (cf. Barker Citation2019; Grasmuck, Martin, and Zhao Citation2009). Altogether, following the theoretical argumentation of culturally dominant ideologies of race and ethnicity formed through Social Identity Theory (Tajfel and Turner Citation1979), these results provide supportive evidence that self-presentations are constructed differently across individuals varying in ethno-racial identity. Thus, results align with previous research indicating that offline norms regarding culture and ethno-racial identity are transferred to online self-presentation (e.g. Grasmuck, Martin, and Zhao Citation2009; Huang and Park Citation2013; Kapidzic and Herring Citation2011, Citation2015; Williams and Marquez Citation2015; Zheng et al. Citation2016).

In contrast to divergence, self-presentations including objectified elements converged. Whereas previous research showed differences between ethno-racial identities and presenting objectified elements (cf. Frith, Shaw, and Cheng Citation2005; Hall, West, and McIntyre Citation2012), the current study did not find any differences in presenting objectified elements between individuals varying in ethno-racial identity. Thus, previously found evidence for the role of ethno-racial identity in portraying objectified selves was not supported for selfie-takers who publicly posted selfies in the current social media saturated environments. However, we must note that objectifying elements were barely present in the dataset, probably due to the public nature of the selfies. Nevertheless, for publicly posted selfies, this result is indicative of convergence in presenting objectified elements. Results are indicative of the theoretical assumption that internalisation of the globally dominant cultures can result in more homogenised images as also found in previous research (cf. Liu, Wang, and Liu Citation2018).

4.1. Strengths, limitations, and future directions

This study examined whether individuals’ self-presentations converge or diverge as a function of ethno-racial identity, showing that online self-presentations generally diverge as a function of ethno-racial identity. A strength is that our study highlights that, even though we found some support that self-presentations converge which is likely due to digitalised globalisation and changing norms towards more individualistic standards, ethno-racial identity still contributes to the online construction of self-presentation (i.e. divergence). Moreover, this study included a rich and unique dataset that comprised actual selfies of individuals in a naturally occurring setting, which means that their self-presentations were not created in an artificial (lab) setting or influenced in any way by the study goals. Furthermore, data collection was not limited by any selection criteria and internationally varied.

This study was not without limitations, however. First, this study could only include publicly posted selfies because private selfies could not be accessed at such large scale. Therefore, selfie-posting behaviours as well as the content of images on Instagram of private postings may deviate from the findings in the current study. The results of this study, therefore, only apply to public self-presentations online posted with the hashtag ‘selfietime’. Future research could aim to acquire Instagram take-out data to examine self-presentation in more private settings. Results regarding privately posted photos on Instagram provide more information in view of the generalisability of the results of the current study.

Second, this study was unable to verify if the individuals that were digitally classified into a specific ethno-racial identity, based on their appearance features, also identify themselves as such. For example, individuals who were classified as having a Hispanic racial identity might actually self-identify differently. Therefore, this study can only make conclusions based on externally software imposed ethno-racial identity. Future studies could investigate how automatic classification or externally imposed classifications coincide with self-reported classifications of ethno-racial identity. Related, this study was unable to ask or detect the national culture of the individuals portrayed in the photos. The cultural dimensions of Hofstede (Citation2001) are typically applied to national cultures, in terms of residing in countries scoring either higher or lower on individualism-collectivism. Although specific ethno-racial identities are more common in certain countries, in this study no conclusions can be drawn regarding national cultures. Especially as pinned location does not necessarily mean that the selfie-takers reside in that particular area (e.g. because pinned location can be used for holiday destinations for example). Future studies could examine if individuals from various countries portray self-presentation features in line with more individualistic or collectivistic standards.

Another limitation, due to the nature of a content analysis, is that no inferences can be made on the motivations of why the selfies were taken and posted online, or on how users have perceived these selfies. Based on individualistic standards, this study aimed to objectively code convergence or divergence on these characteristics. However, selfies including more background, thereby representing more collectivistic standards, may still come from self-expression motives. This would then refer more to individualistic standards than collectivistic standards. Similarly, the nature of our study could not capture how the online photos were perceived by the recipients. Qualitative research would allow to more carefully study such motivations on why someone posted a specific photo (i.e. with what goal and what emphasis) and how such photos are perceived by others who encounter them online.

Moreover, a final limitation within this study resides in the manual coding of our variables. That is, for filter usage only the clearly visible filters could be encoded to generate a sufficient intercoder-reliability. To accurately extract information on the application of such enhancement tools, future research could ideally use machine coding. For example, to estimate the percentage of how the posted photos deviate from original photos. A similar approach could also be used for the face-frame ratio. Regarding measurement of the face-frame ratio, one could also think of categorisation of context inclusiveness instead of the exact ratio (e.g. person is focal point, background is focal point). This approach would, however, be less specific than the ratio. Lastly, although a strict coding scheme was applied to objectively code objectifying elements in the best way possible, by the nature of the study, subjectivity could have played a role in what was perceived as objectifying and what not. This subjectivity in our coding scheme led to the removal of sexualisation in images, which could have also been a good reflection of objectification. Moreover, the overall very low prevalence of presenting objectified elements might also have been the result of such a strict coding scheme. The relatively low intercoder reliability statistics of some of the manually coded variables indicate that our results should be interpreted with caution. We would like to point out that establishing a high intercoder reliability with seven coders from subjective real-life materials is extremely challenging (Carrotte, Prichard, and Lim Citation2017). Nevertheless, the variables included did meet the threshold of inclusiveness based on at least two of the intercoder reliability statistics.

The results of this study addressed the interplay between globalisation, digitalisation, and ethno-racial identity. A fruitful area for future research lies within further examining the mechanisms that play an important role in constructing visual online self-presentations to determine the potential consequences. For example, once important mechanisms of online self-presentation have been identified, heterogeneous results of the impact of self-presentation on well-being could be further explained (Bij de Vaate, Veldhuis, and Konijn Citation2020). For example, based on the findings of the current study, future studies could examine how differences in self-presentation resulting from variation in ethno-racial identity influence individuals’ mental health. Additionally, an interesting line of research would be to examine the role of ethno-racial identity in visual online self-presentation from the viewers’ perspective. Visual self-presentations have limited cues, leaving individuals to make judgements almost solely based on appearance, which for example might be interesting for dating research examining partner preferences based on self-presentation (Ranzini and Lutz Citation2017). Related, based on specific self-presentation features one could look into homogamy or heterogamy among dating partners (Courtiol et al. Citation2010). Lastly, identity construction via online self-presentation is a complex phenomenon that highly depends on differential factors, such as gender, personality traits and contextual factors, such as peer surroundings, and environmental factors such as culture (cf. Valkenburg and Peter Citation2013). Future studies could further examine factors that predispose creating online self-presentations, as well as the possible interplay between predisposing factors.

To conclude, this study further unravels the complexity of the construction of online self-presentation and explored to what extent individuals’ online self-presentation diverge as a function of ethno-racial identity, or rather converge as influenced by globalised digitalisation. Results provided some evidence for converging self-presentations among selfie-takers, however, our study results generally showed that online self-presentations diverge as a function of ethno-racial identity. Hence, the creation of online self-presentations seems to not generally align with the globally dominant Western ideals, rather ethno-racial identity characteristics remain important in manifestations of online self-presentations.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (1.5 MB)Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the independent coders as well as our research assistant Konstantina Trikaliti for their hard work and commitment to this project.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 The facial recognition software used was: https://www.kairos.com. This software has open API, and is used by various companies.

2 After the final round of coding, we decided to not continue with further analysis of the variable facial expressions as the intercoder estimates were not sufficient (i.e. % agreement: 37.5; Krippendorff’s alpha: .56; S-Lotus: .57).

3 Results of a Kruskal-Wallis test showed similar results as the one-way ANOVA (χ2 (3) = 30.832, p = 0.00); Asian and Hispanic selfie-takers post more group selfies than Black and White selfie-takers.

References

- Awad, G. H., C. Norwood, D. S. Taylor, M. Martinez, S. McClain, B. Jones, A. Holman, and C. Chapman-Hilliard. 2015. “Beauty and Body Image Concerns Among African American College Women.” Journal of Black Psychology 41 (6): 540–564. doi:10.1177/0095798414550864.

- Baldissarri, C., L. Andrighetto, A. Gabbiadini, R. R. Valtorta, A. Sacino, and C. Volpato. 2019. “Do Self-Objectified Women Believe Themselves to be Free? Sexual Objectification and Belief in Personal Free Will.” Frontiers in Psychology 10: 1867. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2019.01867.

- Barker, V. 2019. This is Who I Am: The Selfie as a Personal and Social Identity Marker. 24.

- Barker, V., and N. S. Rodriguez. 2019. “This is Who I Am: The Selfie as a Personal and Social Identity Marker.” International Journal of Communication 13: 1143–1166.

- Batool, W., and T. Saleem. 2018. Trends Related to Selfie Taking Behavior: A Way for Self-Representation Among University Students. 1–15. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/346076124_TRENDS_RELATED_TO_SELFIE_TAKING_BEHAVIOR_A_WAY_FOR_SELF-_REPRESENTATION_AMONG_UNIVERSITY_STUDENTS.

- Blanca Mena, M. J., R. Alarcón Postigo, J. Arnau Gras, R. Bono Cabré, and R. Bendayan. 2017. “Non-Normal Data: Is ANOVA Still a Valid Option?” Psicothema 29 (4): 552–557. doi:10.7334/psicothema2016.383

- Bij de Vaate, N. A. J. D., J. Veldhuis, J. M. Alleva, E. A. Konijn, and C. H. M. van Hugten. 2018. “Show Your Best Self(ie): An Exploratory Study on Selfie-Related Motivations and Behavior in Emerging Adulthood.” Telematics and Informatics 35 (5): 1392–1407. doi:10.1016/j.tele.2018.03.010.

- Bij de Vaate, N. A. J. D., J. Veldhuis, and Elly A. Konijn. 2020. “How Online Self-Presentation Affects Well-Being and Body Image: A Systematic Review.” Telematics and Informatics 46: 101316. doi:10.1016/j.tele.2019.101316.

- Butkowski, C. P., T. L. Dixon, K. R. Weeks, and M. A. Smith. 2020. “Quantifying the Feminine Self(ie): Gender Display and Social Media Feedback in Young Women’s Instagram Selfies.” New Media & Society 22 (5): 817–837. doi:10.1177/1461444819871669.

- Carrotte, E. R., I. Prichard, and M. S. C. Lim. 2017. “Fitspiration” on Social Media: A Content Analysis of Gendered Images.” Journal of Medical Internet Research 19 (3): e95. doi:10.2196/jmir.6368.

- Chia, S. C. 2009. “When the East Meets the West: An Examination of Third-Person Perceptions About Idealized Body Image in Singapore.” Mass Communication and Society 12 (4): 423–445. doi:10.1080/15205430802567123.

- Chin Evans, P., and A. R. McConnell. 2003. “Do Racial Minorities Respond in the Same Way to Mainstream Beauty Standards? Social Comparison Processes in Asian, Black, and White Women.” Self and Identity 2 (2): 153–167. doi:10.1080/15298860309030.

- Courtiol, A., M. Raymond, B. Godelle, and J.-B. Ferdy. 2010. “Mate Choice and Human Stature: Homogamy as a Unified Framework for Understanding Mating Preferences.” Evolution. doi:10.1111/j.1558-5646.2010.00985.x.

- Cox, T. H., S. A. Lobel, and P. L. McLeod. 1991. “Effects of Ethnic Group Cultural Differences on Cooperative and Competitive Behavior on a Group Task.” The Academy of Management Journal 34 (4): 827–847. doi:10.5465/256391.

- Feliciano, C. 2016. “Shades of Race: How Phenotype and Observer Characteristics Shape Racial Classification.” American Behavioral Scientist 60 (4): 390–419. doi:10.1177/0002764215613401.

- Fredrickson, B. L., and T.-A. Roberts. 1997. “Objectification Theory: Toward Understanding Women’s Lived Experiences and Mental Health Risks.” Psychology of Women Quarterly 21: 173–206. doi:10.1111/j.1471-6402.1997.tb00108.x.

- Fretwurst, B. 2015. Lotus Manual.

- Frith, K., P. Shaw, and H. Cheng. 2005. “The Construction of Beauty: A Cross-Cultural Analysis of Women’s Magazine Advertising.” Journal of Communication 55 (1): 17. doi:10.1111/j.1460-2466.2005.tb02658.x.

- Fujioka, Y., E. Ryan, M. Agle, M. Legaspi, and R. Toohey. 2009. “The Role of Racial Identity in Responses to Thin Media Ideals: Differences Between White and Black College Women.” Communication Research 36 (4): 451–474. doi:10.1177/0093650209333031.

- Gecas, V. 2000. “Socialization.” In The Encyclopedia of Sociology, edited by E. F. Borgatta, and R. J. Montogomery, 2855–2864. New York, NY: Macmillan.

- Glasser, C. L., B. Robnett, and C. Feliciano. 2009. “Internet Daters’ Body Type Preferences: Race–Ethnic and Gender Differences.” Sex Roles 61 (1–2): 14–33. doi:10.1007/s11199-009-9604-x.

- Gonzales, A. L., and J. T. Hancock. 2011. “Mirror, Mirror on my Facebook Wall: Effects of Exposure to Facebook on Self-Esteem.” Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking 14 (1–2): 79–83. doi:10.1089/cyber.2009.0411.

- Grabe, S., L. M. Ward, and J. S. Hyde. 2008. “The Role of the Media in Body Image Concerns Among Women: A Meta-Analysis of Experimental and Correlational Studies.” Psychological Bulletin 134 (3): 460–476. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.134.3.460.

- Grasmuck, S., J. Martin, and S. Zhao. 2009. “Ethno-Racial Identity Displays on Facebook.” Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication 15 (1): 158–188. doi:10.1111/j.1083-6101.2009.01498.x.

- Gudykunst, W. B. 1997. “Cultural Variability in Communication: An Introduction.” Communication Research 24: 327–348. doi:10.1177/009365097024004001.

- Gudykunst, W. B. 2004. Bridging Differences: Effective Intergroup Communication. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Guo, Y. 2015. “Constructing, Presenting, and Expressing Self on Social Network Sites: An Exploratory Study in Chinese University Students’ Social Media Engagement.” Thesis. The University of British Columbia.

- Hai-Jew, S. 2017. “Creating an Instrument for the Manual Coding and Exploration of Group Selfies on the Social Web.” In Selfies as a Mode of Social Media and Workspace Research, edited by S. Hai-Jew, 173–248. Hershey, PA: IGI Global.

- Hall, P. C., J. H. West, and E. McIntyre. 2012. “Female Self-Sexualization in MySpace.com Personal Profile Photographs.” Sexuality & Culture 16 (1): 1–16. doi:10.1007/s12119-011-9095-0.

- Hofstede, G. 2001. Culture’s Consequences: Comparing Values, Behaviors, Institutions, and Organizations Across Nations. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Huang, C.-M., and D. Park. 2013. “Cultural Influences on Facebook Photographs.” International Journal of Psychology 48 (3): 334–343. doi:10.1080/00207594.2011.649285.

- Hynes, M. 2021. “Towards Cultural Homogenisation.” In The Social, Cultural and Environmental Costs of Hyper-Connectivity: Sleeping Through the Revolution, 39–54. Emerald Publishing Limited. doi:10.1108/978-1-83909-976-220211003

- Jenkins, H. 2006. Convergence Culture: Where Old and New Media Collide. New York: New York University Press.

- Jung, J. 2018. “Young Women’s Perceptions of Traditional and Contemporary Female Beauty Ideals in China.” Family and Consumer Sciences Research Journal 47 (1): 56–72. doi:10.1111/fcsr.12273.

- Kapidzic, S., and S. C. Herring. 2011. “Gender, Communication, and Self-Presentation in Reen Chatrooms Revisited: Have Patterns Changed?” Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication 17 (1): 39–59. doi:10.1111/j.1083-6101.2011.01561.x.

- Kapidzic, S., and S. C. Herring. 2015. “Race, Gender, and Self-Presentation in Teen Profile Photographs.” New Media & Society 17 (6): 958–976. doi:10.1177/1461444813520301.

- Kim, H., and Z. Papacharissi. 2003. “Cross-Cultural Differences in Online Self-Presentation: A Content Analysis of Personal Korean and US Home Pages.” Asian Journal of Communication 13 (1): 100–119. doi:10.1080/01292980309364833.

- Krippendorff, K. 2004. Content Analysis: An Introduction to its Methodology. New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

- Lee-Won, R. J., M. Shim, Y. K. Joo, and S. G. Park. 2014. “Who Puts the Best “Face” Forward on Facebook? Positive Self-Presentation in Online Social Networking and the Role of Self-Consciousness, Actual-to-Total Friends Ratio, and Culture.” Computers in Human Behavior 39: 413–423. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2014.08.007.

- Lee, J.-A., and Y. Sung. 2016. “Hide-and-Seek: Narcissism and “Selfie”-Related Behavior.” Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking 19 (5): 347–351. doi:10.1089/cyber.2015.0486.

- Liu, Z., X. Wang, and J. Liu. 2018. “How Digital Natives Make Their Self-Disclosure Decisions: A Cross-Cultural Comparison.” Information Technology & People 32 (3): 538–558. doi:10.1108/ITP-10-2017-0339.

- Luppicini, R., ed. 2013. Handbook of Research on Technoself: Identity in a Technological Society. IGI Global. doi:10.4018/978-1-4666-2211-1

- Markus, H. R., and S. Kitayama. 1991. “Culture and the Self: Implications for Cognition, Emotion, and Motivation.” Psychological Review 98 (2): 224–253. doi:10.1037/0033-295X.98.2.224.

- Masuda, T., R. Gonzalez, L. Kwan, and R. E. Nisbett. 2008. “Culture and Aesthetic Preference: Comparing the Attention to Context of East Asians and Americans.” Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin 34 (9): 1260–1275. doi:10.1177/0146167208320555.

- McLean, S. A., S. J. Paxton, E. H. Wertheim, and J. Masters. 2015. “Photoshopping the Selfie: Self Photo Editing and Photo Investment are Associated with Body Dissatisfaction in Adolescent Girls: Photoshopping of the Selfie.” International Journal of Eating Disorders 48 (8): 1132–1140. doi:10.1002/eat.22449.

- Meier, E. P., and J. Gray. 2014. “Facebook Photo Activity Associated with Body Image Disturbance in Adolescent Girls.” Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking 17 (4): 199–206. doi:10.1089/cyber.2013.0305.

- Menon, C. V., and S. L. Harter. 2012. “Examining the Impact of Acculturative Stress on Body Image Disturbance Among Hispanic College Students.” Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology 18 (3): 239–246. doi:10.1037/a0028638.

- Michikyan, M., K. Subrahmanyam, and J. Dennis. 2015. “A Picture is Worth a Thousand Words: A Mixed Methods Study of Online Self-Presentation in a Multiethnic Sample of Emerging Adults.” Identity 15 (4): 287–308. doi:10.1080/15283488.2015.1089506.

- Mingoia, J., A. D. Hutchinson, C. Wilson, and D. H. Gleaves. 2017. “The Relationship Between Social Networking Site Use and the Internalization of a Thin Ideal in Females: A Meta-Analytic Review.” Frontiers in Psychology 8: 1351. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2017.01351.

- Nisbett, R. E., and T. Masuda. 2003. “Culture and Point of View.” Proceedings of TheNational Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 100 (19): 11163–11170. doi:10.1073/pnas.1934527100.

- Nisbett, R. E., K. Peng, I. Choi, and A. Norenzayan. 2001. “Culture and Systems of Thought: Holistic Versus Analytic Cognition.” Psychological Review 108 (2): 291–310. doi:10.1037/0033-295X.108.2.291.

- Odağ, Ö, and K. Hanke. 2019. “Revisiting Culture: A Review of a Neglected Dimension in Media Psychology.” Journal of Media Psychology 31 (4): 171–184. doi:doi:10.1027/1864-1105/a000244.

- Prensky, M. 2001. Digital Natives, Digital Immigrants 9 (5): 15. doi:10.1108/10748120110424816.

- Prokopakis, E. P., I. M. Vlastos, V. A. Picavet, G. Nolst Trenite, R. Thomas, C. Cingi, and P. W. Hellings. 2013. “The Golden Ratio in Facial Symmetry.” Rhinology Journal 51 (1): 18–21. doi:10.4193/Rhino12.111.

- Qiu, L., J. Lu, S. Yang, W. Qu, and T. Zhu. 2015. “What Does Your Selfie Say About You?” Computers in Human Behavior 52: 443–449. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2015.06.032.

- Ranzini, G., and C. Lutz. 2017. “Love at First Swipe? Explaining Tinder Self-Presentation and Motives.” Mobile Media & Communication 5 (1): 80–101. doi:10.1177/2050157916664559.

- Rogers Wood, N. A., and T. A. Petrie. 2010. “Body Dissatisfaction, Ethnic Identity, and Disordered Eating among African American Women.” Journal of Counseling Psychology 57 (2): 141–153. doi:10.1037/a0018922.

- Rui, J., and M. A. Stefanone. 2013. “Strategic Self-Presentation Online: A Cross-Cultural Study.” Computers in Human Behavior 29 (1): 110–118. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2012.07.022.

- Samizadeh, S., and W. Wu. 2018. “Ideals of Facial Beauty Amongst the Chinese Population: Results from a Large National Survey.” Aesthetic Plastic Surgery 42 (6): 1540–1550. doi:10.1007/s00266-018-1188-9.

- Schaefer, L. M., N. L. Burke, R. M. Calogero, J. E. Menzel, R. Krawczyk, and J. K. Thompson. 2018. “Self-Objectification, Body Shame, and Disordered Eating: Testing a Core Mediational Model of Objectification Theory among White, Black, and Hispanic Women.” Body Image 24: 5–12. doi:10.1016/j.bodyim.2017.10.005.

- Schooler, D., and L. S. Lowry. 2011. “Hispanic/Latino Body Images.” In Body Image: A Handbook of Science, Practice, and Prevention, edited by T. F. Cash, and L. Smolak, 237–243. New York, NY: Guilford Press.

- Schreurs, L., and L. Vandenbosch. 2022. “The Development and Validation of Measurement Instruments to Address Interactions with Positive Social Media Content.” Media Psychology 25 (2): 262–289. doi:10.1080/15213269.2021.1925561.

- Siibak, A. 2009. “Constructing the Self Through the Photo Selection – Visual Impression Management on Social Networking Websites.” Cyberpsychology: Journal of Psychosocial Research on Cyberspace 3 (1): 1–10.

- Sorokowska, A., A. Oleszkiewicz, T. Frackowiak, K. Pisanski, A. Chmiel, and P. Sorokowski. 2016. “Selfies and Personality: Who Posts Self-Portrait Photographs?” Personality and Individual Differences 90: 119–123. doi:10.1016/j.paid.2015.10.037.

- Statista. 2022. Instagram: Distribution of Global Audiences 2022, by Age Group. https://www.statista.com/statistics/325587/instagram-global-age-group/.

- Tajfel, H. 1978. Differentiation Between Social Groups. Studies in the Social Psychology of Intergroup Relations. London: Academic Press.

- Tajfel, H., and J. Turner. 1979. “An Integrative Theory of Intergroup Conflict.” In The Social Psychology of Intergroup Relations, edited by W. G. Austin, and S. Worchel, 33–47. Monterey, CA: Brooks/Cole.

- Taylor, P., and Scott Keeter. 2010. Millennials. Confident. Connected. Open to Change. PewResearch Center. https://www.pewsocialtrends.org/2010/02/24/millennials-confident-connected-open-to-change/.

- Tiggemann, M., and M. Zaccardo. 2016. “Strong is the New Skinny’: A Content Analysis of #Fitspiration Images on Instagram.” Journal of Health Psychology 23 (8): 1003–1011. doi:10.1177/1359105316639436.

- Trepte, S., and L. S. Loy. 2017. “Social Identity Theory and Self-Categorization Theory.” In The International Encyclopedia of Media Effects, edited by In P. Rössler, C. A. Hoffner, and L. Zoonen. Wiley. doi:10.1002/9781118783764

- Triandis, H. C. 2001. “Individualism-Collectivism and Personality.” Journal of Personality 69 (6): 907–924. doi:10.1111/1467-6494.696169.

- Turner, J. C. 2010. “Towards a Cognitive Redefinition of the Social Group.” In Rediscovering Social Identity, edited by T. Postmes, and N. R. Branscombe, 210–234. New York, NY: Psychology Press.

- Turner, J. C., and K. J. Reynolds. 2010. “The Story of Social Identity.” In Rediscovering Social Identity, edited by T. Postmes, and N. R. Branscombe, 13-32. New York, NY: Psychology Press.

- Twenge, J. M. 2014. Generation Me-Revised and Updated: Why Today’s Young Americans are More Confident, Assertive, Entitled-and More Miserable Than Ever Before. New York, NY: Simon and Schuster.

- Twenge, J. M., and E. Farley. 2021. “Not All Screen Time is Created Equal: Associations with Mental Health Vary by Activity and Gender.” Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology 56 (2): 207–217. doi:10.1007/s00127-020-01906-9.

- Utter, K., E. Waineo, C. M. Bell, H. L. Quaal, and D. L. Levine. 2020. “Instagram as a Window to Societal Perspective on Mental Health, Gender, and Race: Observational Pilot Study.” JMIR Mental Health 7 (10): e19171. doi:10.2196/19171.

- Valkenburg, P. M., and J. Peter. 2013. “The Differential Susceptibility to Media Effects Model.” Journal of Communication 63 (2): 221–243. doi:10.1111/jcom.12024.

- Veldhuis, J. 2020. “Media Use, Body Image, and Disordered Eating Patterns.” In The International Encyclopedia of Media Psychology, edited by J. Van den Bulck, D. R. Ewoldsen, M.-L. Mares, and E. Scharrer. doi:10.1002/9781119011071.iemp0103

- Wang, X., and Z. Liu. 2019. “Online Engagement in Social Media: A Cross-Cultural Comparison.” Computers in Human Behavior 97: 137–150. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2019.03.014.

- Watson, L. B., J. A. Lewis, and A. T. Moody. 2019. “A Sociocultural Examination of Body Image Among Black Women.” Body Image 31: 280–287. doi:10.1016/j.bodyim.2019.03.008.

- Williams, A. A., and B. A. Marquez. 2015. “The Lonely Selfie King: Selfies and the Conspicuous Prosumption of Gender and Race.” International Journal of Communication 9: 1775–1787.

- Winter, V. R., L. K. Danforth, A. Landor, and D. Pevehouse-Pfeiffer. 2019. “Toward an Understanding of Racial and Ethnic Diversity in Body Image Among Women.” Social Work Research 43 (2): 69–80. doi:10.1093/swr/svy033.

- Yip, J., S. Ainsworth, and M. T. Hugh. 2019. “Beyond Whiteness: Perspectives on the Rise of the Pan-Asian Beauty Ideal.” In Race in the Marketplace: Crossing Critical Boundaries, edited by G. D. Johnson, K. D. Thomas, A. K. Harrison, and S. A. Grier. Springer International Publishing. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-11711-5

- Zheng, W., C.-H. Yuan, W.-H. Chang, and Y.-C. J. Wu. 2016. “Profile Pictures on Social Media: Gender and Regional Differences.” Computers in Human Behavior 63: 891–898. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2016.06.041.