ABSTRACT

While there is a growing body of literature on information privacy suggesting different mechanisms of how people’s privacy concerns might be impacting their attitudes and behaviour when using social media, recent questionable data use practices by social media platforms and third parties call for a renewed validation of existing information privacy models. The objective of this research is to re-examine the variables predicting why people disclose information on social media. Building on previous work, this paper puts forward a comprehensive Privacy Concerns and Social Media Use Model (PC-SMU) and evaluates it in a specific cultural and legal environment (social media users from a single county, Canada). The study delves into the privacy paradox and shows that the benefits of using social media are the main driver of self-disclosure, and that self-disclosing behaviours are nuanced by the users’ information privacy protection strategies. We also find that higher levels of social media literacy, and concerns about organisational threats to a lesser extent, lead to higher levels of information privacy management, emphasizing the importance of educating users about how to use the different privacy and security features provided by social media platforms.

1. Introduction

Over the past few years, there have been several questionable data use practices by social media platforms and third parties. For example, in 2016, a UK-based insurance company, Admiral, experimented with using Facebook posts and likes to set premiums for their customers (Ruddick Citation2016). Also in 2016, a South African-based financial institution, Absa Group Limited (formerly Barclays Africa), reportedly explored the use of social media data to do a credit check for people without a credit history (Brinded Citation2016). In 2019, the short video sharing platform TikTok tried to integrate their users’ content into ads without their consent (Hutchinson Citation2019). More recently, in 2020, US-based company Clearview AI created a massive searchable database of billions of images that users uploaded to the web, and then sold access to this database to various government and law enforcement agencies (Daigle Citation2020), including Ukraine’s Ministry of Defence, which has been using this technology since March 2022 to identify Russian soldiers, dead or alive (Hill Citation2022). But arguably, the most infamous organisational misuse of social media user data in recent history that we learned about in 2018 was done by the UK’s data analytics firm Cambridge Analytica, which used information from and about millions of unsuspected Facebook users for political microtargeting. A growing list of questionable data use practices like the ones described above reinvigorate the privacy paradox debate that examines a potential disconnect between users’ declared privacy concerns and their continuing self-disclosure practices on social media.

There is a growing body of literature on information privacy suggesting different mechanisms of how people’s privacy concerns might be impacting their attitudes and behaviour when using social media (as reviewed in the literature review section below). For example, despite being aware of the Cambridge Analytica scandal and being concerned about their privacy, most users stayed on Facebook or came back to the platform after a short break (Perrin Citation2018; Brown Citation2020). Also, according to some industry reports, those who stayed on social media have adopted various information privacy management strategies, such as self-censoring what they post and changing privacy settings to protect their information (Beck Citation2018; DuckDuckGo Citation2019; Valentine Citation2020). What remains to be tested and what also stimulates this research is the privacy paradox related question of whether and to what extent the use of information privacy management predicts users’ self-disclosure practices on social media, if at all. This is a pressing question, considering that more people have been increasingly relying on platforms like Facebook, Instagram and TikTok for social connectivity and information seeking, especially since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic (Boursier et al. Citation2020; Cauberghe et al. Citation2021; Tankovska Citation2021), which in turn has contributed to the ever growing volume of user-generated data for social media companies and others to mine and learn more about people’s interests and habits both online and offline.

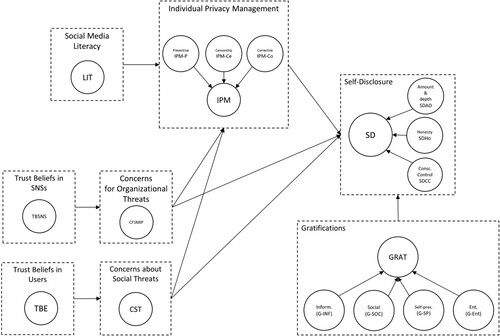

The broad objective of this research is to re-examine the variables predicting why people disclose information on social media. Building on previous work and existing theoretical constructs known to influence people’s self-disclosure practices on social media, this paper puts forward a comprehensive Privacy Concerns and Social Media Use Model (PC-SMU) and evaluates it in a specific cultural and legal environment (social media users from a single county, Canada). The proposed model incorporates the following constructs: organisational and social privacy concerns, trust beliefs towards other users and towards social media platforms, individual privacy management strategies, social media privacy literacy, uses and gratifications, and self-disclosure.

Based on our results, we believe PC-SMU provides the most comprehensive, to date, view of social media use and users, their attitudinal and behavioural indicators while self-disclosing online. The main contribution of the proposed model is the incorporation of Information Privacy Management as both a predictor of self-disclosure behaviours and a mediator between privacy concerns and self-disclosure, as well as the inclusion of antecedents of Privacy Concerns and Information Privacy Management, namely Trust towards social media platforms, Trust towards other social media users, and Social Media Literacy.

The proposed model aims to address the knowledge gap about the relevance of these variables in the context of self-disclosure practices on social media, and aims at providing a more complete view of the privacy paradox (Cheung, Lee, and Chan Citation2015; Barth and de Jong Citation2017; Hallam and Zanella Citation2017; Kokolakis Citation2017). The privacy paradox refers to increased privacy concerns not affecting participants’ self-disclosure practices on social media. The results from prior research are not conclusive in confirming or rejecting the presence of the privacy paradox on social media (or the exact mechanism behind it). For example, Cheung, Lee, and Chan (Citation2015) did not find a significant relationship between perceived privacy risks and self-disclosure, whereas Heravi, Mubarak, and Raymond Choo (Citation2018) observed a ‘limited impact’ of privacy concerns on self-disclosure. Further, different meta-analyses on the privacy paradox, including reviews done by Bauer and Schiffinger (Citation2016) and Yu et al. (Citation2020) in general online contexts, Baruh, Secinti, and Cemalcilar (Citation2017) in online services and social networking sites, Gerber, Gerber, and Volkamer (Citation2018) in general online contexts, social networking sites and different types of applications, and Okazaki et al. (Citation2020) in online retailing, reach different conclusions, which emphasizes the need for further research on this topic.

The structure of this paper is as follows. Section 2 reviews previous literature on privacy concerns and self-disclosure in social media. Section 3 lays out the conceptual framework and research hypotheses. Section 4 describes the research methodology, and Section 5 reports the results of the data analysis. Finally, Sections 6 and 7 present a critical discussion of the findings and lay out the main conclusions of the study, respectively.

2. Literature review

The current work builds on the privacy calculus theory (Culnan and Armstrong Citation1999; Dinev and Hart Citation2004; Li Citation2012) and related models that examine trade-offs between people’s perceived privacy concerns and benefits of self-disclosure on social media. The following is a review of the most relevant models proposed and empirically tested to examine this trade-off. By reviewing foundational work in this area, we seek to identify gaps and additional relations to be tested in our own model.

Krasnova and Veltri (Citation2011) conducted one of the earliest studies that examined the impact of both cost (privacy concerns) and benefits (enjoyment) on self-disclosure practices of social media users. Based on an online survey of 138 Facebook users in Germany and 193 Facebook users in the US (primarily students in both samples), the researchers found that while the perceived enjoyment derived from Facebook use was positively associated with self-disclosure in both samples, privacy concerns were only associated (negatively) with self-disclosure among German users of the platform, but not among US users. On the other hand, trust in Facebook was positively related to self-disclosure among US users, but not among German users.

Building on work by Krasnova et al. (Citation2009, Citation2012), Cheung, Lee, and Chan (Citation2015) also studied privacy-related antecedents of self-disclosure on social media by surveying 405 university students in Hong Kong who used Facebook. The researchers measured self-disclosure, privacy risk, benefits, and social influence. They also examined the relationship between trust in other Facebook users, trust in Facebook, and perceived control on the one hand, and perceived privacy risk on the other. They found that perceived privacy risk has no relationship with self-disclosure, but that the perceived benefits and social influence can positively predict self-disclosure. Trust in Facebook had a negative relationship with perceived privacy risks, but the tested connection between trust in other Facebook users and perceived privacy risks was not significant. Perceived control positively predicted both types of trust and negatively predicted privacy risk.

In another study of Facebook users, Dienlin and Metzger (Citation2016) examined a representative sample of 1156 adults in the United States. The researchers measured privacy concerns, benefits of using Facebook, privacy self-efficacy, self-disclosure, and self-withdrawal. They found a general support of the privacy calculus theory in the context of Facebook use; that is, privacy concerns negatively impact users’ self-disclosure while benefits have a positive impact. The study also found that both privacy concerns and self-efficacy predict users’ privacy preserving behaviours.

Following this line of research and to explore a link between motives for using social media, privacy concerns, and self-disclosure, Heravi, Mubarak, and Raymond Choo (Citation2018) surveyed 521 social media users among the public (via Mechanical Turk crowdsourcing platform) and university students. Most of the respondents came from three counties: India (214), USA (205), and Australia (67). Their study found that concerns regarding the collection of social media data positively predicted the amount and depth of self-disclosure but concerns about unauthorised secondary use negatively predicted the same dimensions of self-disclosure. Various benefits positively predicted self-disclosure. Concerns about errors in stored user data and improper access positively predicted privacy-protective measures.

Li, Cho, and Goh (Citation2019) surveyed 525 Facebook users to uncover that self-disclosure was primarily predicted by benefits (social awareness) and the users’ protection behaviours by their privacy concerns. They also found that social awareness moderated the impact of privacy concerns on two of three types of protection behaviours, self-censorship and correction. However, the study did not directly test a relationship between privacy concerns and self-disclosure, or between privacy management and self-disclosure.

The previous studies are primarily based on small-scale studies surveying users (mostly students) of a single platform (Facebook). Some of the scales, such as benefits and self-disclosure, were unidimensional, which means they likely missed capturing the complexity of these constructs in full. Furthermore, some constructs like Trust towards other users or social media platforms have not been examined in the majority of the previous studies. These limitations make it difficult to generalise the findings from each study. We plan to address this issue by surveying a larger, census-balanced sample of internet users in Canada. Our study also contributes to this research area by expanding the previous models to include privacy management, as well as by analyzing the antecedents of privacy concerns and individual privacy management. Even though these variables are not new and have been previously evaluated as discussed below, this is the first time that they are incorporated into a single model. The following section lays out the theoretical foundations of the research model and poses the research hypotheses for the study.

3. Conceptual framework and research hypotheses

3.1. Privacy concerns and uses & gratifications

According to the privacy calculus theory, an individual’s self-disclosure practices are affected by two competing factors: privacy concerns on the one hand (negatively) and perceived benefits of using social media on the other (positively). Individuals with higher privacy concerns are expected to disclose less or less frequently (Dwyer, Hiltz, and Passerini Citation2007; Dienlin and Metzger Citation2016). Following previous research (Krasnova, Veltri, and Günther Citation2012; Gruzd and Hernández-García Citation2018; Jacobson, Gruzd, and Hernández-García Citation2020), we recognise two primary types of privacy concerns depending on who or what is considered as the primary risk by disclosing individuals: organisations (including social media platforms) or other social media users; thus, we hypothesise the following:

H1a: Concerns for organizational threats negatively predict self-disclosure.

H1b: Concerns for social threats negatively predict self-disclosure.

H2: The perceived benefits of social media use positively predict self-disclosure.

3.2 Information privacy management

Gruzd and Hernández-García (Citation2018) point out that one of the reasons for the existence of the ‘privacy paradox’ is likely that social media users find different ways to moderate their privacy concerns either by making their disclosure more positive and accurate or increasing the amount and depth of disclosure while reducing its accuracy. The former behaviour develops if users are concerned about how platforms and other organisations (organisational threats) might be accessing and using their social media data, whereas the latter may occur if they are concerned that other social media users (social threats) may mishandle their social media data. The existence of these behaviours is in line with the idea that, if people are concerned about their privacy, they may engage in so-called Information Privacy Preserving Response (IPPR), such as changing privacy settings or making formal complaints to the platforms or media (Son and Kim Citation2008).

Based on the regulatory focus theory (Higgins Citation2012) and privacy calculus theory (Dinev and Hart Citation2004), Li, Cho, and Goh (Citation2019) explained that IPPR-related actions may happen before, during or after disclosure as part of Individual Privacy Management (IPM). The researchers also demonstrated that social media users with higher privacy concerns would engage in IPM. In line with this, we hypothesise that individuals with the increased privacy concerns (either concerns for organisational threats or social threats from other users) will employ IPM strategies:

H3a: Concerns for organizational threats positively predict the adoption of IPM strategies.

H3b: Concerns about social threats positively predict the adoption of IPM strategies.

H4: The adoption of IPM strategies positively predicts self-disclosure.

3.3 Social media literacy

IPM strategies might not be relevant or effective if users are not aware of their existence or do not have the competence to implement them. According to the combined model of protection motivation and self-efficacy (Maddux and Rogers Citation1983), individuals also need to have self-efficacy to be engaged in some form of self-protecting behaviour when faced with a privacy risk. In the context of internet studies, self-efficacy often refers to people’s beliefs in their capabilities of using online systems and their specific features, in this case privacy settings, efficiently and effectively. The positive effect of information privacy self-efficacy on information privacy protection behaviour has been found on teens and preteens on the internet (Chai et al. Citation2009). In the social media context, Facebook users with a higher level of internet literacy were also more confident and likely to adjust their privacy settings (Boyd and Hargittai Citation2010). Furthermore, those with higher levels of self-efficacy in managing their privacy were more likely to rely on self-withdrawal mechanisms, a form of self-protecting behaviour (Dienlin and Metzger Citation2016).

While self-efficacy can be broadly viewed as ‘beliefs about one’s ability to perform a specific behavior’ (Compeau, Higgins, and Huff Citation1999), the notion of literacy tends to measure an individual's skill set of doing something more directly. For instance, Bartsch and Dienlin (Citation2016) asked Facebook users about the extent to which they know how to perform certain actions on the platform, such as deleting or deactivating their account, or restricting access to either their profile information or their posts. According to their study, Facebook users with higher levels of online privacy literacy were also more likely to change their privacy settings to protect their privacy on the platform.

We incorporate the social media literacy construct as an antecedent to IPM strategies. In other words, we want to examine whether users who are knowledgeable about the technical aspects of using social media platforms are also more likely to engage in IPM strategies. This is because social media platforms are complex socio-technical systems that require their users to have a nuanced understanding of not just how to populate their user profile and share content with others, but also how to change and adjust various privacy and other settings within their accounts. Social media platforms also tend to evolve over time and new features are constantly being introduced into their ecosystems. As a result, to be a knowledgeable and capable user of such platforms, individuals ought to pay attention to changes to the interface, privacy policies and other customisation options. Following the previous work on social media self-efficacy and literacy, we hypothesise:

H5: Social Media Literacy positively predicts the adoption of IPM strategies.

3.4 Trust

To further expand our model, we turned to trust beliefs in social media platforms and other users, as these constructs have shown to moderate users’ privacy concerns on social media (Acquisti and Gross Citation2006; Cheung, Lee, and Chan Citation2015; Koohang, Paliszkiewicz, and Goluchowski Citation2018). Drawing from the marketing literature, the level of trust between customers and companies plays an important role in regulating consumers’ information exchange and support cooperation, especially during transactions involving some level of risk and uncertainty (Schurr and Ozanne Citation1985; Moorman, Zaltman, and Deshpande Citation1992).

Trust usually develops over time based on the previous positive interaction with the external party and the willingness to carry out a transaction with said party even in face of potential risks (Milne and Boza Citation1999). For example, in the context of e-commerce, trust in an e-commerce website was a prerequisite to people using an online bookstore (Gefen Citation2000). Similarly, in the context of direct marketing practices, trust in how organisations use personal information is positively related to direct marketing usage when consumers make their purchases via mail, phone or internet, but concerns about how organisations use personal information have a smaller and negative effect on direct marketing usage (Milne and Boza Citation1999).

In the context of social media use, in addition to examining trust beliefs towards social media platforms, it is important to study trust beliefs towards other social media users who have access to information shared by the content poster. When studying how trust is formed among social media users and its role in online self-disclosure, we need to consider the social exchange theory from the literature on interpersonal communication (see Cook et al. Citation2013 for a review of contributions to this theory). This theory describes how trust between two parties participating in social exchanges ‘reduce the perceived costs of such transactions’ and that it is especially important in online communication due to the reduced social cues between participants (Metzger Citation2004, n.p.). For example, while a user may be aware of potential privacy risks when sharing personal information on social media, their trust that other users with access to their information will handle it fairly, responsibly, honestly, competently, and consistently (Rempel, Holmes, and Zanna Citation1985; Metzger Citation2004) may moderate and reduce their overall privacy concerns (Acquisti and Gross Citation2006; Cheung, Lee, and Chan Citation2015; Koohang, Paliszkiewicz, and Goluchowski Citation2018). Therefore, our trust-related hypotheses are as follows:

H6a: Trust in social media platforms negatively predicts concerns for organizational threats.

H6b: Trust in other social media users negatively predicts concerns about social threats.

4. Method

To test our hypotheses, we collected data via an online survey among online Canadian adults (internet users aged 18 and older). The survey was approved by the Institutional Research Ethics Board. To increase the representativeness of the sample and reflect the demographic mix of Canada, we used proportional quota sampling to recruit respondents. The quotas were based on gender, age, and geographical region to match the distributions in the 2019 Statistics Canada population estimates (Statistics Canada Citation2019). We used Dynata, a market research firm, to recruit study participants. The survey was hosted on Qualtrics, an online survey platform. We received a total of 1500 completed responses between April 9–17, 2020, excluding incomplete responses and those completed under 5 min.

For the analysis of the data, we applied Partial Least Squares Path Modeling (PLS-PM), also known as Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM), using the SmartPLS 4.0.6.2 software, to examine the survey data and estimate relationships between the studied constructs (as described in Section 4.1). PLS-SEM is an estimator to structural equation models that can deal with reflective and causal–formative measurement models as well as composite models, and can be applied to confirmatory, explanatory, exploratory, descriptive, and predictive research (Benitez et al. Citation2020). PLS-SEM is also the recommended approach to analyse complex models when we do not necessarily know how data are distributed (Hair et al. Citation2019).

4.1 Measures

The scales used in the study have been selected based on the extensive literature review of related scales and their use cases. All items, except for those relating to Social Media Literacy were measured in a Likert-5 scale, ranging from ‘Strongly agree’ to ‘Strongly disagree’ (note that all scales are therefore reversed).

4.1.1. Privacy concerns

To study online Privacy Concerns (Buchanan et al. Citation2007; Gruzd and Hernández-García Citation2018; Krasnova et al. Citation2009; Krasnova, Veltri, and Günther Citation2012; Osatuyi Citation2015), we relied on two scales: Osatuyi’s (Citation2015) Concerns for Social Media Information Privacy (CFSMIP) to measure people’s concern about privacy due to organisational threats, and Krasnova’s et al. (Citation2009, Citation2012) Concerns about Social Threats (CST) to measure concerns related to other social media users misusing one’s personal information. Following Krasnova’s et al. (Citation2009), and to avoid potential discriminant validity issues between the low-level dimensions of CFSMIP, both CFSMIP and CST were modelled as first-order constructs.

4.1.2. Uses & gratification

To assess the perceived benefits, we examined people’s motivations that drive their social media use based on the Uses & Gratification framework (Ko, Cho, and Roberts Citation2005; Chen Citation2011; Heravi, Mubarak, and Raymond Choo Citation2018). We relied on the scale proposed by Cheung, Lee, and Chan (Citation2015) that has been previously validated in social media research (James et al. Citation2017; Jacobson, Gruzd, and Hernández-García Citation2020). The scale was modelled as a second-order composite using Information SharingFootnote1 (G-INF), New Relationship Building (G-SOC), Self-Presentation (G-SP), and Enjoyment (G-Ent) as first-order constructs.

4.1.3. Self-disclosure

To measure the level of self-disclosure, a social process by which people share personal information with one another, the study draws from Wheeless’s (Citation1976) conceptualisation, which proposed five dimensions to measure self-disclosure offline. We used a version of this scale that was adapted to the social media context (Desjarlais and Joseph Citation2017; Kashian et al. Citation2017; Gruzd and Hernández-García Citation2018). The scale was modelled as a second-order composite using Amount and Depth (SDAD), Conscious Control (SDCC), and Honesty (SDHo) as first-order constructs.

4.1.4. Information protection management

To assess to what extent an individual might be engaged in Information Protection Management (IPM), we followed Li, Cho, and Goh (Citation2019) to evaluate this practice in accordance with three dimensions: preventive, censorship, and corrective strategies. Each dimension generally corresponds to different stages of disclosure: preventive strategies tend to be used before the disclosure happens, censorship or self-censorship during (or right before) the disclosure, and corrective strategies after the disclosure. Preventive strategies often involve relying on privacy or security settings provided by a social media platform to control who may access shared content. In a separate work, Fiesler et al. (Citation2017) found that their study participants relied more on self-censorship and ‘friends list management’ to control their privacy rather than on privacy settings. Censorship (or self-censorship) strategies occur when an individual intentionally withholds their true opinion (Hayes, Scheufele, and Huge Citation2006). Self-censorship usually happens during (or right before) a disclosure happens. This is when an individual may assess the specific context in which the disclosure happens and who would be their audience (intended or unintended). Self-censorship may be driven by a number of factors, including: fear of isolation, especially when holding the minority point of view (Noelle-Neumann Citation1974; Kwon, Moon, and Stefanone Citation2015; Chan Citation2018), self-esteem, especially when trying to avoid criticism and negative feedback (Parloff and Handlon Citation1964; Williams Citation2002), or image management to control how others view them (Walther Citation1992; DeAndrea et al. Citation2012; Sleeper et al. Citation2015). For the purposes of our research, we only focus on how privacy concerns may drive one’s self-censorship behaviour. Corrective strategies are usually employed if a person has privacy concerns after they shared something on social media (Child, Haridakis, and Petronio Citation2012). For example, Twitter users may decide to delete previously published posts if they regret posting content related to drugs, sex, violence and other sensitive topics (Zhou, Wang, and Chen Citation2016). In sum, the IPM scale was modelled as a second-order composite using Preventive Strategies (IPM-P), Censorship (IPM-Ce), and Corrective Strategies (IPM-Co) as first-order constructs.

4.1.5. Trust beliefs

Trust beliefs reflect the confidence that personal information submitted or shared with others will be handled competently, benevolently, and with integrity by the trustee (Mayer, Davis, and Schoorman Citation1995; McKnight, Choudhury, and Kacmar 2002). Following Lo and Riemenschneider (Citation2010), we examine two types of trust beliefs: trust beliefs in a social media company and users’ willingness to disclose personal information on their platform (TBSNS), and trust beliefs in other social media users (TBE). Both were modelled as first-order constructs.

4.1.6. Social media literacy

Finally, to measure Social Media Literacy (SML), we followed previous research by Koc and Barut (Citation2016) and Wisniewski, Knijnenburg, and Lipford (Citation2017), who adopted a multifaceted view of social media literacy focused on users’ awareness about and their familiarity with common social media features or functionalities. The scale includes six items about features related to account activation, account deletion, profile management and content access, and asks respondents about their familiarity or knowledge with those features using a Likert-5 scale (from knowing about the feature ‘extremely well’ to ‘not well at all’).

Appendix A includes the questions for each scale mentioned above.

4.2. Data analysis

The analysis follows the guidelines for PLS-SEM analysis and reporting (Hair Jr. et al. Citation2017; Benitez et al. Citation2020). PLS-SEM is a non-parametric method that aims to predict a key target construct. Because the model includes several second-order formative-reflective constructs (Information Privacy Management, Uses and Gratifications, Self-Disclosure) (Becker, Klein, and Wetzels Citation2012), the specification and analysis follow a disjoint two-stage approach (Sarstedt et al. Citation2019). In the disjoint two-stage approach, only first-order constructs are included in the first stage, and then the latent variable scores are incorporated as indicators of the second-order constructs in the second stage. During the first stage, the model assessment includes the following procedures: internal consistency, convergent and discriminant validity of the lower-order components, and convergent validity, collinearity between indicators and significance and relevance of outer weights of the higher-order components. Stage two follows standard PLS-SEM assessment of the measurement and structural model, using Mode B to estimate the higher-order component and path weighting scheme.

4.2.1. Disjoint two-stage approach: stage one

After observation of the HTMT ratio, the preliminary results show potential discriminant validity issues between some constructs. Potential solutions to handle this issue involve either increasing the average monotrait-heteromethod correlations (e.g. eliminating items with low correlations with other items, splitting the construct into homogeneous sub-constructs) or decreasing the average heteromethod-heterotrait correlations (e.g. eliminating items strongly correlated with items in other constructs, or reassigning problematic indicators to the other construct or merging constructs) (Henseler, Ringle, and Sarstedt Citation2015). In this study, the theoretical building of the model supports the second way. Specifically, we found potential discriminant validity issues between the lower-order components of the CFSMIP construct (Collection and Secondary Use dimensions). This result is in line with Osatuyi (Citation2015), Gruzd and Hernández-García (Citation2018) and Jacobson et al. (Jacobson, Gruzd, and Hernández-García Citation2020); however, unlike in the previous studies, we propose an alternative specification of the model with CFSMIP modelled as a first-order construct with indicators from both components (thus decreasing heteromethod-heterotrait correlations), as the HTMT correlation exceeded 0.900.Footnote2

Additional discriminant validity issues also emerged between the three first-order components of IPM. One indicator in corrective behaviours (unfriending or blocking users) had high correlation with other IPM indicators; a possible explanation is that this behaviour may be considered as preventive or corrective, depending on the context (e.g. a user may block other users to prevent them accessing the content that will be published or block them upon a negative interaction after the content has been published). Therefore, this item was removed from the analysis, a decision that is consistent with the item’s relatively low factorial loading found in Cho and Filippova (Citation2016). Further, the analysis yielded a high correlation between indicators of preventive and censorship behaviours, but the cause of this result may differ from the high correlation between unfriending/blocking and other indicators; to solve this problem, different considerations were made. First, Li, Cho, and Goh (Citation2019) did not report inter-item correlations, and therefore it was difficult to assess whether the same problems emerged in their characterisation. Second, one item (‘I make use of lists to restrict the audience of my posts to certain individuals’) involves performing a behaviour that is carefully planned before disclosure; this is in line with the consideration of curating lists of users as a preventive strategy in Cho and Filippova (Citation2016),Footnote3 as opposed to viewing this behaviour corrective in Li, Cho, and Goh (Citation2019). Third, grouping different items from both constructs would be consistent with the characterisation of preventive strategies in Lampinen et al. (Citation2011). Fourth, Li et al.’s (Citation2019) operationalisation of censorship strategies does not include the use of private communication channels and restricts the idea of the intended audience to friends. Based on these considerations, two items corresponding to censorship strategies (‘I limit what I share on social media to only what is appropriate for my intended audience to see’ and ‘I make use of private communication channels when I want to talk about sensitive subjects’) were removed, and the remaining two (‘I adjust the content of my posts based on who I think will see’ and ‘I make use of lists to restrict the audience of my posts to certain individuals’) were merged with the rest of items measuring the ‘preventive strategies’ construct.

The results of the analysis confirm the internal consistency, convergent validity and discriminant validity of the measurement model: values of composite reliability (ρc), ρa and Cronbach’s alpha were over 0.600, 0.700 and 0.700, respectively, and Average Variance Extracted (AVE) values were over the threshold of 0.500 (); factorial loadings of the indicators were above the cut-off level of 0.707 (), and values of the HTMT ratio were below 0.900 (the HTMT correlation between both types of Trust was below 0.900 but over the more restrictive threshold of 0.850; therefore, we chose to retain both variables as independent constructs to preserve content validity) (). Finally, all Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) values were below 5, and thus multicollinearity issues were discarded.

Table 1. Construct reliability and validity.

Table 2. Outer loadings.

Table 3. Discriminant validity (Stage 1, HTMT criterion).

4.2.2. Disjoint two-stage approach: stage two

In the second stage of the disjoint two-stage approach, the latent variable scores of the lower-order components are used as indicators (Mode B) of the higher-order components of the model. The assessment of the measurement and structural model then follows standard PLS-SEM analysis procedures.

The analysis establishes internal consistency reliability, convergent and discriminant validity (). The smallest values of Cronbach’s alpha, composite reliability and Jöreskog’s rho are 0.833, 0.900 and 0.835. Standard loadings of reflective constructs are well over the cut-off value of 0.707, VIF values are below 5 (VIF values below 3 in formative constructs), and outer weights of formative indicators are significant at p < 0.05, except for one in the Honesty dimension of Self-Disclosure and the Entertainment component of Uses and Gratifications, with significant loadings of 0.478 and 0.794. AVE is over 0.720 for all constructs, well above the 0.500 threshold. Discriminant validity was established after observation of the HTMT ratio of correlations. It is worth noting that the ratio of correlations between both types of Trust was 0.884, still over the most conservative 0.850 threshold. To further investigate discriminant validity, we also observed HTMT2 values (Roemer, Schuberth, and Henseler Citation2021) using the semTools and cSEM packages in R. HTMT2 is an improved version of the traditional HTMT that relaxes the assumption of tau-equivalence and replaces the arithmetic means used in HTMT’s computation by geometric means. The analysis returned lower HTMT2 values, but still relatively high for both Trust-based constructs (0.881). Following Roemer et al.’s (Citation2021) recommendation, we also used statistical inference; the upper bound of the 90% bootstrap confidence interval (alpha = 0.050) was lower than 0.900, which suggests that discriminant validity can be established.

Table 4. Internal and convergent validity.

Table 5. Outer loadings (in italics. outer weights of formative constructs/composites).

Table 6. Discriminant validity (Stage 2; lower diagonal – HTMT criterion; upper diagonal – HTMT2).

5. Results

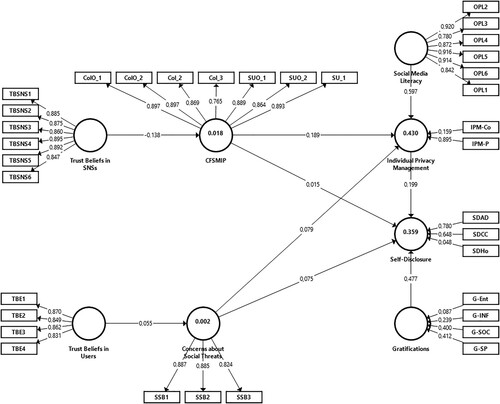

The analysis of the structural model () yields a strong positive relationship between social media literacy and privacy management (β = 0.597; p-value = 0.000), and between gratifications and self-disclosure (β = 0.477; p-value = 0.000); these results support hypotheses H2 and H5. There is a moderate positive relationship between CFSMIP and IPM (β = 0.189; p-value = 0.000), and between IPM and Self-Disclosure (β = 0.199; p-value = 0.000), in support of H3a and H4, and negative but moderate relationship between Trust Beliefs in Social Networking Sites and CFSMIP (β = −0.138; p-value = 0.000), supporting H6a. The analysis also finds a weak relationship between CST and IPM (β = 0.079; p-value = 0.022), partially supporting H3b. On the other hand, the analysis found no support for H1a, H1b and H6b (Trust Beliefs in Users → CST, β = 0.055, p-value = 0.078; CFSMIP → Self-Disclosure, β = 0.015, p-value = 0.726; CST → Self-Disclosure, β = 0.075, p-value = 0.056).

To assess the model, we observed R-squared values, which measure the in-sample predictive power (Hair Jr. et al. Citation2021). While the model does not offer a good explanation of organisational or social concerns based on Trust Beliefs (adj. R2 < 0.020), the variance explained for IPM and Self-Disclosure is moderate (adj. R2 = 0.430 and adj. R2 = 0.359, respectively). The inclusion of IPM largely improves the results of Gruzd and Hernández-García (Citation2018) (their maximum R-squared of Self-Disclosure components is 0.16; for reference, the first stage of the disjoint two-stage approach from the current study yields R-squared values between 0.158 and 0.293 for first-order components of Self-Disclosure).

For comparative purposes, the study dataset was also applied to the more parsimonious model in Gruzd and Hernández-García (Citation2018); adjusting for model complexity, the increase in adjusted R-squared is 0.031 (0.359 vs. 0.328), which equates to approximately a 10-percent increase over the base model; the analysis also returns lower SRMR and BIC values, suggesting the superiority of the model in this study.

The analysis of effect sizes (f-squared) yields little or no effect of Trust Beliefs in Users on CST, of CST on IPM and Self-Disclosure, and of CFSMIP on Self-Disclosure; there is a small effect of Trust Beliefs in SNSs on CFSMIP (f2 = 0.019), and of CFSMIP and IPM on Self-Disclosure (f2 = 0.031 and 0.053, respectively); the effect of Uses and Gratifications on Self-Disclosure is between medium and large (f2 = 0.314), and there is a large effect of Social Media Literacy on IPM (f2 = 0.622). The blindfolding procedure with an omission distance of 7 returns values of positive Q-squared, suggesting the predictive relevance of the model.

6. Discussion

This study was launched as a way to re-examine the relevance of the privacy paradox notion in the context of contemporary social media use and in light of several questionable data use practices by social media platforms and third parties, such as the Cambridge Analytica scandal, that have become known to the public in recent years. Our results are in line with Baruh, Secinti, and Cemalcilar’s (Citation2017) meta-analysis, hinting at the presence of the privacy paradox on social media. Specifically, we find that users’ self-disclosure behaviours are largely driven by their views of potential benefits obtained from using social media and their perceived ability to control what personal information and how they share it online. While our data could not support the hypotheses that test the association between privacy concerns (be it organisational or social threats) and self-disclosure, low coefficient paths and relatively high p-values seem to be in favour of confirming the privacy paradox; that is, social media users are disclosing regardless of their potential privacy concerns. This finding calls for further research to unpack the exact mechanisms of how privacy concerns and self-disclosure behaviour interplay in light of information privacy protection strategies. The following provides a more nuanced summary of our findings and their interpretation.

The novelty of our work lies in the introduction of IPM to explain the presence of the privacy paradox. When it comes to predicting self-disclosure behaviours, we find that these are mainly driven not just by gratifications but also by the adoption of information privacy management strategies by social media users. Therefore, the results support Gruzd and Hernández-García’s (Citation2018) untested assumption that when users perceive a threat to their privacy, they engage in information privacy-protective responses, such as preventive and corrective strategies. Furthermore, when compared to previous research on the privacy paradox, the results support that the incorporation of Information Privacy Management into the model substantially improves the predictive power of the model (e.g. the explanatory power of the model approximately doubles the results found in Gruzd and Hernández-García (Citation2018)).

While the results of the disjoint two-stage approach do not support H1a and H1b, the first stage analysis shows relationships between both types of Privacy Concerns (organisational and social) and the individual components of Self-Disclosure (e.g. amount and depth, conscious control, and honesty). Consistent with Gruzd and Hernández-García (Citation2018), this result evidences the complexity of Self-Disclosure as a construct and suggests that future research should focus on the effect of the different predictors on individual components of self-disclosure behaviours rather than on Self-Disclosure as a single construct. On a related point, Self-Disclosure is defined primarily by the amount, depth and conscious control. That is, honesty is not a fundamental aspect of Self-Disclosure. This finding emphasizes the relevance of amount and depth, contests the conceptualisation of Krasnova et al. (Citation2009) and suggests that alternative configurations (e.g. amount and depth, accuracy, polarity and intent in Jacobson, Gruzd, and Hernández-García [Citation2020]) may be more appropriate to investigate self-disclosure behaviours.

Regarding the Uses and Gratifications construct (U&G), we found an important difference in how this construct is formed when comparing our results and those reported in Jacobson, Gruzd, and Hernández-García (Citation2020). Whereas in Jacobson, Gruzd, and Hernández-García (Citation2020) the authors showed similar contributions across all four subdimensions of this construct (i.e. informational, entertainment, social, and self-presentation), the current study shows a shift towards self-presentation and social uses and gratifications of social media and, to a lesser extent, of the informational value of content posted online. The use of social media for entertainment turned out to be the least important component of the U&G construct. The reason for this result is likely that the period of data collection coincided with the initial outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic in the spring of 2020. At that time, and due to social distance and confinement, users may have primarily used social media to keep up with their relatives and friends,Footnote4 share personal content; for example, to cope with loneliness, anxiety and stress (Cauberghe et al. Citation2021) or to obtain relevant information about the pandemic and its effects (Gruzd and Mai Citation2020). Thus, the use of social media for entertainment purposes might have shifted to the background, and people may have favoured other services, such as music and video streaming to satisfy those needs (Comscore Citation2020; Tankovska Citation2021).

Further, the study finds that IPM behaviours are primarily determined by social media literacy (supporting H5) and, to a lesser extent, by CFSMIP (supporting H3a). Therefore, social media literacy, or users’ perceived self-competence on the use of social media platforms, is the strongest predictor of IPPR behaviours. The fact that higher levels of literacy and concerns about organisational threats lead to higher levels of privacy management evidences the importance of educating users about how to use different privacy and security features provided by social media platforms.

An exploration of the results of the first stage analysis offers a more nuanced interpretation of the relationship between both types of privacy concerns and IPM. From the results of the first stage analysis, CFSMIP seems to have a more pronounced effect on preventive strategies than corrective strategies, while the opposite happens with CST. In other words, concerns about organisational threats seem to be associated with preventive strategies while concerns for social threats are associated with corrective strategies. Therefore, on the one hand, users try to pre-emptively protect themselves from third parties by adjusting their privacy settings; on the other hand, they use corrective strategies, such as untagging themselves or deleting content, to address potential misuse of their personal information by other users. From the results of the second stage of the analysis, the explanation of the weak relationship between CST and IPM behaviours might lie in that IPM behaviours seem to be dominated by preventive behaviours. That is, IPM mostly comprises behaviours such as restricting the audience of the content posted or adjusting privacy settings. Furthermore, although we expected that different privacy concerns might trigger different IPPRs, our analysis suggests that the potential effect of privacy concerns on self-disclosure behaviour is not only mediated by the IPM strategies adopted by users, but also that these strategies are mostly determined by users’ usage of preventive privacy protection strategies (as opposed to corrective ones).

Importantly, the research unveils a moderate negative relationship between Trust Beliefs in SNSs and CFSMIP (supporting H6a), but the analysis does not support the hypothesised relationship between Trust Beliefs in Other Users and CST (H6b). The first result substantiates the findings of Miltgen and Smith (Citation2015), who find that higher levels of trust in companies and regulators are associated with lower levels of privacy risk concerns. The second result, however, might be explained by the fact that user’s concerns about being affected by other users taking advantage of their personal information or using it for malicious purposes are not related to whether they are considered trustworthy. It is well established in the literature that building trusting relationships with the users is necessary for social media platforms to promote the creation of authentic user-generated content (Lo and Riemenschneider Citation2010). The requisite of trust also holds true for third parties accessing and using personal information from social media (be it for commercial or governmental purposes). Trust has also been linked to the privacy risks that users perceive when sharing on social media (Cheung, Lee, and Chan Citation2015). However, our study questions the need for users to trust other users when self-disclosing in social media. This finding is possible because the surveyed population exhibited moderate to high levels of trust in other users, and moderate to low concerns about other users potentially misusing their personal information. Future research should revisit this result in the context of low-trust and high-privacy concerns in online environments, such as online dating applications.

7. Conclusions

Based on a comprehensive review of the existing theoretical constructs known to influence self-disclosure on social media, this study proposed and evaluated a comprehensive Privacy Concerns and Social Media Use Model (PC-SMU). From a theoretical perspective, the PC-SMU advances existing knowledge on self-disclosure on social media by analysing the role of information privacy management strategies within the wider context of the relationship between privacy concerns and self-disclosure (or privacy paradox), as well as by investigating the effect of the antecedents of IPM and privacy concerns. The results also open the discussion about future conceptualizations of the constructs involved in the privacy paradox studies.

In their comment on Yu et al.’s (Citation2020) and previous meta-analyses supporting the privacy paradox, Dienlin and Sun (Citation2021) concluded that the topic ‘remains an open question in need of further theoretical and empirical efforts’ (7). While the results of our analysis were not conclusive regarding the relationship between privacy concerns and self-disclosure, and therefore we cannot offer a clear answer to that question, our findings seem to be in favour of supporting the notion of privacy paradox, wherein there is an unbalance between information privacy attitudes and information privacy behaviours (Gerber, Gerber, and Volkamer Citation2018), and support the adequacy of the application of the privacy calculus theory to self-disclosure behaviours on social media. The benefits of using social media seem to outweigh other potential drivers of self-disclosure, but they are nuanced by the users’ information privacy protection strategies. For example, users who view social media as a good way to socialise with friends or family members will be more likely to post on social media, even if they are concerned about their privacy. This could be because their privacy concerns might be mitigated by their use of preventive strategies, such as changing their privacy settings to restrict who can view their profiles or posts. Our results, therefore, suggest that the gratification sought by users when using social media (social, self-presentation, informational or entertainment) exceeds in importance that of the perceived risks. As social media platforms rely on the creation of content by users, this result should not be taken lightly because it could open the door to third parties abusing this situation, irrespective of whether they are trusted or not.

On the practical side, the confirmation that the adoption of IPM strategies positively affects self-disclosure suggests that to instill confidence in users, social media platforms ought to provide effective privacy and security management features that users can use to confirm and adjust their privacy boundaries. Furthermore, because social media literacy was found to positively affect the adoption of IPM strategies, it is also not just about making privacy and security features available on the platform: users need to have the required knowledge and competence to use them, which requires investment in both usability of such features and literacy training on the part of social media platforms and other public and educational institutions.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the anonymous reviewers for their invaluable feedback and all survey participants for taking part in the study.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Cheung, Lee, and Chan (Citation2015) refer to this dimension as ‘Convenience of Maintaining Existing Relationships’.

2 Gruzd and Hernández-García (Citation2018) and Jacobson, Gruzd, and Hernández-García (Citation2020) found HTMT correlations over 0.850, but below 0.900.

3 It is worth noting that, other than the use of lists, the items measuring preventive strategies in Cho and Filippova (Citation2016) are completely different from the ones in Li, Cho, and Goh (Citation2019). Our analysis might then question the adequacy of directly applying the measures of Li, Cho, and Goh (Citation2019) in the future.

4 Other digital technologies, such as videoconferencing systems (e.g., Zoom, Skype) have also been instrumental in satisfying the need for social communication.

References

- Acquisti, A., and R. Gross. 2006. “Imagined Communities: Awareness, Information Sharing, and Privacy on the Facebook.” In Privacy Enhancing Technologies, edited by G. Danezis, and P. Golle, 36–58. Springer Berlin Heidelberg. doi:10.1007/11957454_3

- Barth, S., and M. D. T. de Jong. 2017. “The Privacy Paradox – Investigating Discrepancies Between Expressed Privacy Concerns and Actual Online Behavior – A Systematic Literature Review.” Telematics and Informatics 34 (7): 1038–1058. doi:10.1016/j.tele.2017.04.013.

- Bartsch, M., and T. Dienlin. 2016. “Control Your Facebook: An Analysis of Online Privacy Literacy.” Computers in Human Behavior 56: 147–154. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2015.11.022.

- Baruh, L., E. Secinti, and Z. Cemalcilar. 2017. “Online Privacy Concerns and Privacy Management: A Meta-Analytical Review.” Journal of Communication 67 (1): 26–53. doi:10.1111/jcom.12276.

- Bauer, C., and M. Schiffinger. 2016. “Perceived Risks and Benefits of Online Self-Disclosure: Affected by Culture? A Meta-Analysis of Cultural Differences as Moderators of Privacy Calculus in Person-to-Crowd Settings.” Research Papers. https://aisel.aisnet.org/ecis2016_rp/68.

- Beck, J. 2018. “People are Changing the Way They Use Social Media.” The Atlantic, June 7. https://www.theatlantic.com/technology/archive/2018/06/did-cambridge-analytica-actually-change-facebook-users-behavior/562154/.

- Becker, J.-M., K. Klein, and M. Wetzels. 2012. “Hierarchical Latent Variable Models in PLS-SEM: Guidelines for Using Reflective-Formative Type Models.” Long Range Planning 45 (5–6): 359–394. doi:10.1016/j.lrp.2012.10.001.

- Benitez, J., J. Henseler, A. Castillo, and F. Schuberth. 2020. “How to Perform and Report an Impactful Analysis Using Partial Least Squares: Guidelines for Confirmatory and Explanatory IS Research.” Information & Management 57 (2): 103168. doi:10.1016/j.im.2019.05.003.

- Boursier, V., F. Gioia, A. Musetti, and A. Schimmenti. 2020. “Facing Loneliness and Anxiety During the COVID-19 Isolation: The Role of Excessive Social Media Use in a Sample of Italian Adults.” Frontiers in Psychiatry 11: 586222. doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2020.586222.

- Boyd, D., and E. Hargittai. 2010. “Facebook Privacy Settings: Who Cares?” First Monday, doi:10.5210/fm.v15i8.3086.

- Brinded, L. 2016. “Yasaman Hadjibashi at Barclays Africa: Banks Using Big Data and Social Media.” Business Insider, September 23. https://www.businessinsider.com/yasaman-hadjibashi-at-barclays-africa-banks-using-big-data-and-social-media-2016-9?r=UK.

- Brown, A. J. 2020. “‘Should I Stay or Should I Leave?’: Exploring (Dis)Continued Facebook Use After the Cambridge Analytica Scandal.” Social Media + Society 6 (1): 205630512091388. doi:10.1177/2056305120913884.

- Buchanan, T., C. Paine, A. N. Joinson, and U.-D. Reips. 2007. “Development of Measures of Online Privacy Concern and Protection for Use on the Internet.” Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology 58: 157–165. doi: 10.1002/asi.20459.

- Cauberghe, V., I. Van Wesenbeeck, S. De Jans, L. Hudders, and K. Ponnet. 2021. “How Adolescents Use Social Media to Cope with Feelings of Loneliness and Anxiety During COVID-19 Lockdown.” Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking 24 (4): 250–257. doi:10.1089/cyber.2020.0478.

- Chai, S., S. Bagchi-Sen, C. Morrell, H. R. Rao, and S. J. Upadhyaya. 2009. “Internet and Online Information Privacy: An Exploratory Study of Preteens and Early Teens.” IEEE Transactions on Professional Communication 52 (2): 167–182. doi:10.1109/TPC.2009.2017985.

- Chan, M. 2018. “Reluctance to Talk About Politics in Face-to-Face and Facebook Settings: Examining the Impact of Fear of Isolation, Willingness to Self-Censor, and Peer Network Characteristics.” Mass Communication and Society 21 (1): 1–23. doi:10.1080/15205436.2017.1358819.

- Chen, G. M. 2011. “Tweet This: A Uses and Gratifications Perspective on How Active Twitter Use Gratifies a Need to Connect with Others.” Computers in Human Behavior 27 (2): 755–762. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2010.10.023.

- Cheung, C., Z. W. Y. Lee, and T. K. H. Chan. 2015. “Self-Disclosure in Social Networking Sites.” Internet Research 25 (2): 279–299. doi:10.1108/IntR-09-2013-0192.

- Child, J. T., P. M. Haridakis, and S. Petronio. 2012. “Blogging Privacy Rule Orientations, Privacy Management, and Content Deletion Practices: The Variability of Online Privacy Management Activity at Different Stages of Social Media Use.” Computers in Human Behavior 28 (5): 1859–1872. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2012.05.004.

- Cho, H., and A. Filippova. 2016. “Networked Privacy Management in Facebook: A Mixed-Methods and Multinational Study.” In Proceedings of the 19th ACM Conference on Computer-Supported Cooperative Work & Social Computing, 503–514. doi:10.1145/2818048.2819996

- Compeau, D., C. A. Higgins, and S. Huff. 1999. “Social Cognitive Theory and Individual Reactions to Computing Technology: A Longitudinal Study.” MIS Quarterly 23 (2): 145–158. doi:10.2307/249749.

- Comscore. 2020. Comscore Sees Notable Rise in Streaming Usage. https://www.comscore.com/Insights/Press-Releases/2020/3/Comscore-Sees-Notable-Rise-in-Streaming-Usage.

- Cook, K. S., C. Cheshire, E. R. W. Rice, and S. Nakagawa. 2013. “Social Exchange Theory.” In Handbook of Social Psychology, edited by J. DeLamater, and A. Ward, 61–88. Springer Netherlands. doi:10.1007/978-94-007-6772-0_3.

- Culnan, M. J., and P. K. Armstrong. 1999. “Information Privacy Concerns, Procedural Fairness, and Impersonal Trust: An Empirical Investigation.” Organization Science 10 (1): 104–115. doi:10.1287/orsc.10.1.104.

- Daigle, T. 2020. “Clearview AI Facial Recognition Offers to Delete Some Faces—But Not in Canada.” CBC News, June 10. https://www.cbc.ca/news/science/clearview-ai-canadian-data-1.5605258.

- DeAndrea, D. C., S. Tom Tong, Y. J. Liang, T. R. Levine, and J. B. Walther. 2012. “When Do People Misrepresent Themselves to Others? The Effects of Social Desirability, Ground Truth, and Accountability on Deceptive Self-Presentations.” Journal of Communication 62 (3): 400–417. doi:10.1111/j.1460-2466.2012.01646.x.

- Desjarlais, M., & Joseph, J. J. (2017). Socially Interactive and Passive Technologies Enhance Friendship Quality: An Investigation of the Mediating Roles of Online and Offline Self-Disclosure, Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 20(5), 286–291. doi:10.1089/cyber.2016.0363

- Dienlin, T., and M. J. Metzger. 2016. “An Extended Privacy Calculus Model for SNSs: Analyzing Self-Disclosure and Self-Withdrawal in a Representative U.S. Sample.” Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication 21 (5): 368–383. doi:10.1111/jcc4.12163.

- Dienlin, T., and Y. Sun. 2021. “Does the Privacy Paradox Exist? Comment on Yu et al.’s (2020) Meta-Analysis.” Meta-Psychology 5. doi:10.15626/MP.2020.2711.

- Dinev, T., and P. Hart. 2004. “Internet Privacy Concerns and Their Antecedents—Measurement Validity and a Regression Model.” Behaviour & Information Technology 23 (6): 413–422. doi:10.1080/01449290410001715723.

- DuckDuckGo. 2019. “New DuckDuckGo Research Shows People Taking Action on Privacy.” https://spreadprivacy.com/people-taking-action-on-privacy/.

- Dwyer, C., S. Hiltz, and K. Passerini. 2007. “Trust and Privacy Concern Within Social Networking Sites: A Comparison of Facebook and MySpace.” AMCIS 2007 Proceedings, 339.

- Fiesler, C., M. Dye, J. L. Feuston, C. Hiruncharoenvate, C. J. Hutto, S. Morrison, P. Khanipour Roshan, et al. 2017. “What (or Who) Is Public? Privacy Settings and Social Media Content Sharing.” In Proceedings of the 2017 ACM Conference on Computer Supported Cooperative Work and Social Computing, 567–580. doi:10.1145/2998181.2998223

- Gefen, D. 2000. “E-commerce: The Role of Familiarity and Trust.” Omega 28 (6): 725–737. doi:10.1016/S0305-0483(00)00021-9.

- Gerber, N., P. Gerber, and M. Volkamer. 2018. “Explaining the Privacy Paradox: A Systematic Review of Literature Investigating Privacy Attitude and Behavior.” Computers & Security 77: 226–261. doi:10.1016/j.cose.2018.04.002.

- Gruzd, A., and Á. Hernández-García. 2018. “Privacy Concerns and Self-Disclosure in Private and Public Uses of Social Media.” Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking 21 (7): 418–428. doi:10.1089/cyber.2017.0709.

- Gruzd, A., and P. Mai. 2020. “Inoculating Against an Infodemic: A Canada-Wide COVID-19 News, Social Media, and Misinformation Survey.” Ryerson University Social Media Lab Report, May 11. doi:10.5683/SP2/JLULYA

- Hair, J. F., Jr., G. T. M. Hult, C. M. Ringle, and M. Sarstedt. 2021. A Primer on Partial Least Squares Structural Equation Modeling (PLS-SEM). SAGE Publications.

- Hair, J. F., Jr., Lucy M. Matthews, Ryan L. Matthews, and Marko Sarstedt. 2017. “PLS-SEM or CB-SEM: Updated Guidelines on Which Method to use.” International Journal of Multivariate Data Analysis 1 (2): 107–123. doi:10.1504/IJMDA.2017.087624.

- Hair, J. F., J. J. Risher, M. Sarstedt, and C. M. Ringle. 2019. “When to Use and How to Report the Results of PLS-SEM.” European Business Review 31 (1): 2–24. doi: 10.1108/EBR-11-2018-0203.

- Hallam, C., and G. Zanella. 2017. “Online Self-Disclosure: The Privacy Paradox Explained as a Temporally Discounted Balance Between Concerns and Rewards.” Computers in Human Behavior 68 (Supplement C): 217–227. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2016.11.033.

- Hayes, A. F., D. A. Scheufele, and M. E. Huge. 2006. “Nonparticipation as Self-Censorship: Publicly Observable Political Activity in a Polarized Opinion Climate.” Political Behavior 28 (3): 259–283. doi:10.1007/s11109-006-9008-3.

- Henseler, J., C. M. Ringle, and M. Sarstedt. 2015. “A New Criterion for Assessing Discriminant Validity in Variance-Based Structural Equation Modeling.” Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science 43 (1): 115–135. doi:10.1007/s11747-014-0403-8.

- Heravi, A., S. Mubarak, and K.-K. Raymond Choo. 2018. “Information Privacy in Online Social Networks: Uses and Gratification Perspective.” Computers in Human Behavior 84: 441–459. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2018.03.016.

- Higgins, E. T. 2012. “Regulatory Focus Theory.” In Handbook of Theories of Social Psychology, Vol. 1, 483–504. Sage Publications Ltd. doi:10.4135/9781446249215.n24

- Hill, K. 2022. “Facial Recognition Goes to War.” The New York Times, April 7. https://www.nytimes.com/2022/04/07/technology/facial-recognition-ukraine-clearview.html.

- Hutchinson, A. 2019. “TikTok’s Turning User-Submitted Content into Ads, Without User Knowledge.” Social Media Today, October 8. https://www.socialmediatoday.com/news/tiktoks-turning-user-submitted-content-into-ads-without-user-knowledge/564518/.

- Jacobson, J., A. Gruzd, and Á Hernández-García. 2020. “Social Media Marketing: Who is Watching the Watchers?” Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services 53: 101774. doi:10.1016/j.jretconser.2019.03.001.

- James, T. L., P. B. Lowry, L. Wallace, and M. Warkentin. 2017. “The Effect of Belongingness on Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder in the Use of Online Social Networks.” Journal of Management Information Systems 34 (2): 560–596. doi:10.1080/07421222.2017.1334496.

- Kashian, N., J. Jang, S. Y. Shin, Y. Dai, and J. B. Walther. 2017. “Self-disclosure and Liking in Computer-Mediated Communication.” Computers in Human Behavior 71: 275–283. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2017.01.041.

- Ko, H., C.-H. Cho, and M. S. Roberts. 2005. “Internet Uses and Gratifications: A Structural Equation Model of Interactive Advertising.” Journal of Advertising 34 (2): 57–70. doi:10.1080/00913367.2005.10639191.

- Koc, M., and E. Barut. 2016. “Development and Validation of New Media Literacy Scale (NMLS) for University Students.” Computers in Human Behavior 63: 834–843. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2016.06.035.

- Kokolakis, S. 2017. “Privacy Attitudes and Privacy Behaviour: A Review of Current Research on the Privacy Paradox Phenomenon.” Computers & Security 64: 122–134. doi:10.1016/j.cose.2015.07.002.

- Koohang, A., J. Paliszkiewicz, and J. Goluchowski. 2018. “Social Media Privacy Concerns: Trusting Beliefs and Risk Beliefs.” Industrial Management & Data Systems 118 (6): 1209–1228. doi:10.1108/IMDS-12-2017-0558.

- Krasnova, H., O. Günther, S. Spiekermann, and K. Koroleva. 2009. “Privacy Concerns and Identity in Online Social Networks.” Identity in the Information Society 2 (1): 39–63. doi:10.1007/s12394-009-0019-1.

- Krasnova, H., and N. Veltri. 2011. “Behind the Curtains of Privacy Calculus on Social Networking Sites: The Study of Germany and the USA.” Wirtschaftsinformatik Proceedings. http://aisel.aisnet.org/wi2011/26

- Krasnova, H., N. F. Veltri, and O. Günther. 2012. “Self-disclosure and Privacy Calculus on Social Networking Sites: The Role of Culture.” Business & Information Systems Engineering 4 (3): 127–135. doi:10.1007/s12599-012-0216-6.

- Kwon, K. H., S.-I. Moon, and M. A. Stefanone. 2015. “Unspeaking on Facebook? Testing Network Effects on Self-Censorship of Political Expressions in Social Network Sites.” Quality & Quantity 49 (4): 1417–1435. doi:10.1007/s11135-014-0078-8.

- Lampinen, A., V. Lehtinen, A. Lehmuskallio, and S. Tamminen. 2011. “We’re in it Together: Interpersonal Management of Disclosure in Social Network Services.” Proceedings of the 2011 Annual Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems – CHI ‘11 3217. doi:10.1145/1978942.1979420.

- Li, Y. 2012. “Theories in Online Information Privacy Research: A Critical Review and an Integrated Framework.” Decision Support Systems 54 (1): 471–481. doi:10.1016/j.dss.2012.06.010.

- Li, P., H. Cho, and Z. H. Goh. 2019. “Unpacking the Process of Privacy Management and Self-Disclosure from the Perspectives of Regulatory Focus and Privacy Calculus.” Telematics and Informatics 41: 114–125.

- Lo, J., and C. Riemenschneider. 2010. “An Examination of Privacy Concerns and Trust Entities in Determining Willingness to Disclose Personal Information on a Social Networking Site.” AMCIS 2010 Proceedings. https://aisel.aisnet.org/amcis2010/46

- Maddux, J. E., and R. W. Rogers. 1983. “Protection Motivation and Self-Efficacy: A Revised Theory of Fear Appeals and Attitude Change.” Journal of Experimental Social Psychology 19 (5): 469–479. doi:10.1016/0022-1031(83)90023-9.

- Mayer, R. C., J. H. Davis, and F. D. Schoorman. 1995. “An Integrative Model of Organizational Trust.” The Academy of Management Review 20 (3): 709–734.

- Metzger, M. J. 2004. “Privacy, Trust, and Disclosure: Exploring Barriers to Electronic Commerce.” Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication 9 (JCMC942). doi:10.1111/j.1083-6101.2004.tb00292.x.

- Milne, G. R., and M.-E. Boza. 1999. “Trust and Concern in Consumers’ Perceptions of Marketing Information Management Practices.” Journal of Interactive Marketing 13 (1): 5–24. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1520-6653(199924)13:1<5::AID-DIR2>3.0.CO;2-9.

- Miltgen, C. L., and H. J. Smith. 2015. “Exploring Information Privacy Regulation, Risks, Trust, and Behavior.” Information & Management 52 (6): 741–759. doi:10.1016/j.im.2015.06.006.

- Moorman, C., G. Zaltman, and R. Deshpande. 1992. “Relationships Between Providers and Users of Market Research: The Dynamics of Trust Within and Between Organizations.” Journal of Marketing Research 29 (3): 314–328. doi:10.1177/002224379202900303.

- Noelle-Neumann, E. 1974. “The Spiral of Silence a Theory of Public Opinion.” Journal of Communication 24 (2): 43–51. doi:10.1111/j.1460-2466.1974.tb00367.x.

- Okazaki, S., M. Eisend, K. Plangger, K. de Ruyter, and D. Grewal. 2020. “Understanding the Strategic Consequences of Customer Privacy Concerns: A Meta-Analytic Review.” Journal of Retailing 96 (4): 458–473. doi:10.1016/j.jretai.2020.05.007.

- Osatuyi, B. 2015. “Personality Traits and Information Privacy Concern on Social Media Platforms.” Journal of Computer Information Systems 55 (4): 11–19.

- Parloff, M. B., and J. H. Handlon. 1964. “The Influence of Criticalness on Creative Problem-Solving in Dyads.” Psychiatry 27 (1): 17–27.

- Perrin, A. 2018. “Americans are Changing Their Relationship with Facebook.” Pew Research Center. Accessed July 23, 2022. https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2018/09/05/americans-are-changing-their-relationship-with-facebook/.

- Quinn, K. 2016. “Why We Share: A Uses and Gratifications Approach to Privacy Regulation in Social Media Use.” Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media 60 (1): 61–86. doi:10.1080/08838151.2015.1127245.

- Rempel, J. K., J. G. Holmes, and M. P. Zanna. 1985. “Trust in Close Relationships.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 49 (1): 95–112. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.49.1.95.

- Roemer, E., F. Schuberth, and J. Henseler. 2021. “HTMT2–an Improved Criterion for Assessing Discriminant Validity in Structural Equation Modeling.” Industrial Management & Data Systems 121 (12): 2637–2650. doi:10.1108/IMDS-02-2021-0082.

- Ruddick, G. 2016. “Admiral to Price Car Insurance Based on Facebook Posts.” The Guardian, November 2. http://www.theguardian.com/technology/2016/nov/02/admiral-to-price-car-insurance-based-on-facebook-posts.

- Sarstedt, M., J. F. Hair, J.-H. Cheah, J.-M. Becker, and C. M. Ringle. 2019. “How to Specify, Estimate, and Validate Higher-Order Constructs in PLS-SEM.” Australasian Marketing Journal 27 (3): 197–211. doi:10.1016/j.ausmj.2019.05.003.

- Schurr, P. H., and J. L. Ozanne. 1985. “Influences on Exchange Processes: Buyers’ Preconceptions of a Seller’s Trustworthiness and Bargaining Toughness.” Journal of Consumer Research 11 (4): 939–953. doi:10.1086/209028.

- Sleeper, M., A. Acquisti, L. F. Cranor, P. G. Kelley, S. A. Munson, and N. Sadeh. 2015. “I Would Like To … , I Shouldn’T … , I Wish I … : Exploring Behavior-Change Goals for Social Networking Sites.” Proceedings of the 18th ACM Conference on Computer Supported Cooperative Work & Social Computing, 1058–1069. doi:10.1145/2675133.2675193.

- Son, J.-Y., and S. S. Kim. 2008. “Internet Users’ Information Privacy-Protective Responses: A Taxonomy and a Nomological Model.” MIS Quarterly 32 (3): 503–529.

- Statistics Canada. 2019. “Population Estimates on July 1st, by Age and Sex [Data set].” Government of Canada. doi:10.25318/1710000501-ENG.

- Tankovska, H. 2021. Social Media Use During Coronavirus (COVID-19) Worldwide (Statista). https://www.statista.com/topics/7863/social-media-use-during-coronavirus-covid-19-worldwide/.

- Valentine, O. 2020. “Data Privacy on Social Media and Why it Matters. we are Social.” https://wearesocial.com/us/blog/2020/03/data-privacy-on-social-media-and-why-it-matters/.

- Walther, J. B. 1992. “Interpersonal Effects in Computer-Mediated Interaction.” Communication Research 19 (1): 52–90. doi:10.1177/009365092019001003.

- Wheeless, L. R. 1976. “Self-Disclosure and Interpersonal Solidarity: Measurement, Validation, and Relationships.” Human Communication Research 3 (1): 47–61. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2958.1976.tb00503.x.

- Williams, S. D. 2002. “Self-Esteem and the Self-Censorship of Creative Ideas.” Personnel Review 31 (4): 495–503. doi: 10.1108/00483480210430391.

- Wisniewski, P. J., B. P. Knijnenburg, and H. R. Lipford. 2017. “Making Privacy Personal: Profiling Social Network Users to Inform Privacy Education and Nudging.” International Journal of Human-Computer Studies 98: 95–108. doi:10.1016/j.ijhcs.2016.09.006.

- Yu, L., H. Li, W. He, F.-K. Wang, and S. Jiao. 2020. “A Meta-Analysis to Explore Privacy Cognition and Information Disclosure of Internet Users.” International Journal of Information Management 51: 102015. doi:10.1016/j.ijinfomgt.2019.09.011.

- Zhou, L., Wang, W., & Chen, K. (2016). Tweet Properly: Analyzing Deleted Tweets to Understand and Identify Regrettable Ones. Proceedings of the 25th International Conference on World Wide Web, 603–612. https://doi.org/10.1145/2872427.2883052

Appendix A.

Survey questions

Social Media Literacy (LIT):

Based on your knowledge of features provided by various social media sites, how well do you know how to:

Delete or deactivate my account (OPL1)

Restrict access to profile information such as hobbies, interests (OPL2)

Make my profile not accessible via Google (OPL3)

Control if others tag my name on pictures (OPL4)

Restrict access to my postings (OPL5)

Restrict access to my contact information (e.g. name, address) (OPL6)

Individual Privacy Management (IPM):

Thinking about all of the social media sites you use, to what extent do you agree with the following statements:

I adjust the privacy settings to control who can view my profile (PREV1)

I adjust the privacy settings to control who can view my posts (PREV2)

I adjust the privacy settings to control who can contact me (PREV3)

I adjust the mobile app permissions to control what personal information is collected (PREV4)

I limit what I share on social media to only what is appropriate for my intended audience to see (CENS1)†

I adjust the content of my posts based on who I think will see it (CENS2)

I make use of lists to restrict the audience of my posts to certain individuals (CENS3)

I make use of private communication channels when I want to talk about sensitive subjects (CENS4)†

I untag myself from photos my friends uploaded (CORR1)

I delete content posted about me by my friends (CORR2)

If I no longer want someone to see my status updates, I defriend or block them (CORR3)†

Self-Disclosure (SD):

When using social media, to what extent do you agree with the following statements:

I usually talk about myself on social media for fairly long periods (SDAm2)

I often discuss my feelings about myself on social media (SDAm3)

I often express my personal beliefs and opinions on social media (SDAm4)

I typically reveal information about myself on social media without intending to (SDD2)

I often disclose intimate, personal things about myself on social media without hesitation (SDD3)

When I post about myself on social media, the posts are fairly detailed (SDD4)

I am always honest in the information I provide on social media (SDH2)

I am always truthful when I write about myself on social media (SDH3)

When I post something on social media, I am always careful about what exactly I am saying about myself (SDC1)

When I express myself on social media, I always consider who can see the information I publish (SDC2)

I think carefully how much I reveal about myself on social media (SDC3)

Concerns for Social Media Information Privacy (CFSMIP):

To what extent do you agree with the following statements:

I am often concerned that social media sites could store my information indefinitely (Col_2)

Every now and then I feel anxious that social media sites might know too much about me (Col_3)

I am often concerned that social media sites could share the information I provide with other parties (e.g. marketing, HR or government agencies) (SU_1)

I am often concerned other parties (e.g. marketing, HR, government agencies) could collect my information from social media (ColO_1)

I am often concerned that my information from social media could be stored by some other party (e.g. marketing, HR, government agencies) many years from now (ColO_2)

I am often concerned that other parties (e.g. marketing, HR, government agencies) could share the information they have collected about me from social media (SUO_1)

It often worries me that other parties (e.g. marketing, HR, government agencies) could use the information they have collected about me from social media for commercial purposes (SUO_2)

Concerns about Social Threats (CST):

To what extent do you agree with the following statements:

I am often concerned that someone might purposefully embarrass me on social media (SSB1)

It often worries me that other users might purposefully write something undesired about me on social media (SSB2)

I am often concerned that other users might take advantage of the information they learned about me through social media (SSB3)

Uses & Gratifications (GRAT):

To what extent do you agree with the following statements:

Social media is convenient for informing all my friends about my ongoing activities (CON1)

Social media allows me to save time when I want to share something new with my friends (CON2)

I find social media efficient in sharing information with my friends (CON3)

Through social media I get connected to new people who share my interests (RB1)

Social media helps me to expand my network (RB2)

I get to know new people through social media (RB3)

I try to make a good impression on others on social media (SP1)

I try to present myself in a favorable way on social media (SP2)

Social media helps me to present my best sides to others (SP3)

When I am bored, I often go to social media (EN1)

I find social media entertaining (EN2)

I spend enjoyable and relaxing time on social media (EN3)

Trust Beliefs in Social Networking Sites (TBSNS):

Please indicate your level of agreement with the following statements regarding your personal information on social media.