?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

Healthcare professionals, including students, may express stigmatising attitudes towards mental illness. Virtual reality is thought to provide a novel insight into the experiences of individuals with mental health conditions and to reduce stigma. This study aims to systematically review the evidence concerning the use of virtual reality as an educational tool to reduce mental health stigma in healthcare and non-healthcare students. Literature searches were conducted across four electronic databases. Studies were eligible if they targeted healthcare or non-healthcare students, used any form of virtual reality, focused on experiences of mental health conditions, and measured changes in stigma-related outcomes. Fifteen studies, of which eight on healthcare students, were included and synthesised narratively. Both immersive and non-immersive virtual reality technologies were used, and most focused on simulations of mental health symptoms. Different outcomes were measured, including stereotypes, prejudice, and discrimination, and all studies relied on self-report instruments. There is support for using virtual reality to reduce mental health stigma among healthcare students, but not among non-healthcare students. While non-immersive technologies might be as effective as immersive ones, a focus on psychopathology and a lack of educational information appear to increase stigma. Stereotypes and discriminatory intentions were the outcomes most susceptible to change.

1. Background

Mental health conditions (MHCs) are highly prevalent in Western societies (Eaton et al. Citation2008; Wittchen et al. Citation2011). It is estimated, for instance, that 17% of the adult population in England meet the diagnostic criteria for a common MHC such as anxiety, depression, or a combination of both (McManus et al. Citation2016). In a similar trend, data from the US show that about 20% of the adult population suffers from a diagnosable MHC each year (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration Citation2021). As expected, and supported by recent systematic review and meta-analytic evidence, these figures increased at the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic but over time returned to pre-pandemic levels (Ahmed et al. Citation2023; Robinson et al. Citation2022). Critically, MHCs are associated with increased human, social, and economic costs, which are thought to exceed those of physical health conditions such as musculoskeletal disorders, infectious diseases, and cardiovascular illnesses (Vigo, Thornicroft, and Atun Citation2016). However, among those with MHCs, only a small proportion seek and receive adequate treatment (Thornicroft Citation2007), amplifying both the individual and societal burden. While reasons for this may be multifactorial, mental health stigma has been identified as a common obstacle to accessing healthcare (Clement et al. Citation2015; Vistorte et al. Citation2018).

There is a multitude of studies suggesting that mental health stigma operates across all domains of life as people with MHCs face challenges in securing and maintaining work (Brouwers et al. Citation2016; Sharac et al. Citation2010), housing (Browne and Courtney Citation2007; Peterson et al. Citation2006), and social relationships (Boardman Citation2011; Jorm and Oh Citation2009). Furthermore, people with MHCs experience a lower standard of care, not only for their mental health but also for their physical health (Henderson et al. Citation2014; Mitchell, Malone, and Doebbeling Citation2009; Thornicroft, Rose, and Kassam Citation2007). For example, healthcare professionals tend to express more negative attitudes towards patients with MHCs compared to patients with physical health conditions (Minas et al. Citation2011). Additionally, healthcare professionals who hold stigmatising attitudes towards patients with MHCs are more likely to believe that these would not adhere to treatment, and in consequence, are less likely to refill their prescriptions or refer them to specialist care (Corrigan et al. Citation2014). More than that, for patients with MHCs, many healthcare professionals tend to misjudge the presentation of physical symptoms as simple manifestations of patients’ mental health rather than indicators of a separate health problem (Mason and Scior Citation2004; Shefer et al. Citation2014), leading to the phenomenon of ‘diagnostic overshadowing’.

In turn, healthcare professionals’ stigma, together with that of society at large, could contribute to the internalisation of negative attitudes and beliefs among people with MHCs (Watson et al. Citation2006). As a result, those who experience self-stigma are more likely to delay treatment seeking (Clement et al. Citation2015; Schnyder et al. Citation2017) and less likely to adhere to medication plans (Kamaradova et al. Citation2016; Uhlmann et al. Citation2014), while becoming more preoccupied with their condition (Lin et al. Citation2016; Yen et al. Citation2009). These findings might explain, at least to some extent, the worryingly high rates of physical morbidity and mortality seen across MHCs (Thornicroft Citation2011).

In light of this overwhelming evidence, mental health stigma has become an urgent public health concern, and major institutions around the world are now calling for orchestrated efforts to reduce stigma and discrimination, including that of healthcare professionals (e.g. Thornicroft et al. Citation2022; WHO Citation2022). Contact with people with MHCs and education about these conditions are two mechanisms regarded to diminish stigma (Corrigan and Penn Citation1999), and, as a result, have been frequently used as active ingredients in anti-stigma interventions (e.g, Lien et al. Citation2021; Martínez-Martínez et al. Citation2019; Pursehouse Citation2023). Education-based interventions show positive results in increasing knowledge about MHCs (Yamaguchi, Mino, and Uddin Citation2011), whereas contact-based interventions are effective in reducing stigmatising attitudes, affective bias, and negative behavioural intentions towards people with MHCs (Maunder and White Citation2019). However, systematic review and/or meta-analytic evidence indicates that these effects are modest and, in fact, might not be sustainable in the long run (McCullock and Scrivano Citation2023; Morgan et al. Citation2018; Yamaguchi et al. Citation2013). Furthermore, contact with people with MHCs is not always possible, and, paradoxically, in some circumstances, increased contact can heighten the desire for social distance (Jorm and Oh Citation2009; Rubenking and Bracken Citation2015). These observations highlight the current limitations of mainstream interventions and tools, and, inevitably, make a case for devising better approaches to tackle mental health stigma.

A novel opportunity to target mental health stigma is offered by virtual reality (VR), a technology that allows one’s cognition to immerse into a digitally generated environment and which is thought to produce similar responses as in real-world settings (Christofi and Michael-Grigoriou Citation2017; Ma and Zheng Citation2011; Sanchez-Vives and Slater Citation2005). Existing scholarship has already established the effectiveness of VR in reducing public stigma towards MHCs (Rodríguez-Rivas et al. Citation2022), advocating for its potential use in educational, organisational, and healthcare contexts. Furthermore, within healthcare, VR-based technologies are becoming more and more used in the assessment, diagnosis, and treatment of MHCs such as anxiety and depression (Baghaei et al. Citation2021; Chitale et al. Citation2022), disordered eating (Clus et al. Citation2018), psychosis (Schroeder et al. Citation2022), and post-traumatic stress (Kothgassner et al. Citation2019), but also more widely in the education of healthcare professionals (Kyaw et al. Citation2019; Mäkinen et al. Citation2022; Ruthenbeck and Reynolds Citation2015).

As students and trainees in healthcare disciplines may express more negative attitudes towards people with MHCs than qualified healthcare professionals (Arvaniti et al. Citation2009; Oliveira et al. Citation2020; Thornicroft, Rose, and Mehta Citation2010), increasing attention has been paid to the role of VR as an educational tool to reduce healthcare students’ mental health stigma (e.g. Lem et al. Citation2022; Marques et al. Citation2022; Zare-Bidaki et al. Citation2022). However, individual studies paint a rather fragmented view, and much variability exists in relation to the characteristics of these studies, the design of VR interventions, and the measures used to assess efficacy, which limits one’s ability to make any firm recommendations for healthcare educators and policymakers, as Hand, Olaiya, and Elmasry (Citation2020) also noted. This gap justifies the need to gain a better, systematic understanding of the current evidence for the use of VR in healthcare students to reduce stigma against people with MHCs and, eventually, optimise the quality of care they receive. Furthermore, compared to healthcare students, non-healthcare students tend to show similar levels of stigma towards people with MHCs (Ruiz et al. Citation2022; Totic et al. Citation2012). However, to our knowledge, no systematic review has attempted to compare the use of VR to reduce mental health stigma in healthcare and non-healthcare students.

This study aims to systematically review the available evidence pertaining to the use of VR as an educational tool to reduce mental health stigma among healthcare and non-healthcare students. More specifically, this study will seek to clarify whether VR interventions have a similar effect on healthcare and non-healthcare students, what type of VR interventions have been used and how they were designed and/or delivered, and how the efficacy of VR interventions was measured. To guide the development of eligibility criteria, the theoretical model put forward by Corrigan (Citation2000) has been used to delineate stereotypes (i.e. generalised beliefs about MHCs/people with MHCs), prejudice (i.e. negative affective reactions towards MHCs/people with MHCs), and discrimination (i.e. unjust, hostile behaviours against people with MHCs) as core elements of mental health stigma.

2. Methods

2.1. Registration

This systematic review was pre-registered on PROSPERO in October 2022 (CRD42022368202) and its reporting was guided by the PRISMA statement (Page et al. Citation2021).

2.2. Eligibility criteria

A set of inclusion and exclusion criteria was developed as shown in . The population of interest was any group of university-level students studying healthcare, including but not limited to medicine, nursing, midwifery, paramedic science, nutrition, psychology, social work, and non-healthcare subjects. To broaden the scope of the review, studies based on elements or extensions of VR such as augmented reality (AR) and mixed reality (MR) were also given consideration. As such, using a broad definition, we accepted any form of VR intervention, including those using elements or extensions of VR, that focused on simulating the experiences of individuals with mental health conditions. In terms of outcomes of interest, studies had to evaluate changes in any mental health stigma-related outcome, including cognitive (e.g. stereotypes), affective (e.g. prejudice) or behavioural (e.g. discrimination) measures. Studies with or without a comparison group were accepted, and these must have included experimental or quasi-experimental designs. Additionally, to be considered eligible, studies must have been written in English, peer-reviewed, and published in academic journals no earlier than 2000.

Table 1. Eligibility criteria.

2.3. Information sources and search strategy

Literature searches were conducted between November and December 2022 across four electronic databases – PubMed, APA PsycINFO, Scopus, and Web of Science. Search terms included virtual reality (“Virtual Reality” OR “VR” OR “Virtual Environment” OR “VR Simulation” OR “VR Character” OR “Augmented Reality” OR “AR” OR “Mixed Reality” OR “MR” OR “Extended Reality” OR “XR”) AND stigma (“Stigma” OR “Stigmat*” OR “Stereotyp*” OR “Prejudice” OR “Discriminat*”) AND mental health (“Mental” OR “Psychological” OR “Psychiatric”). Reference lists of key articles (e.g. past reviews) were also searched to find additional studies. Search results were then transferred into an open-source reference management software for screening and review purposes.

2.4. Study selection

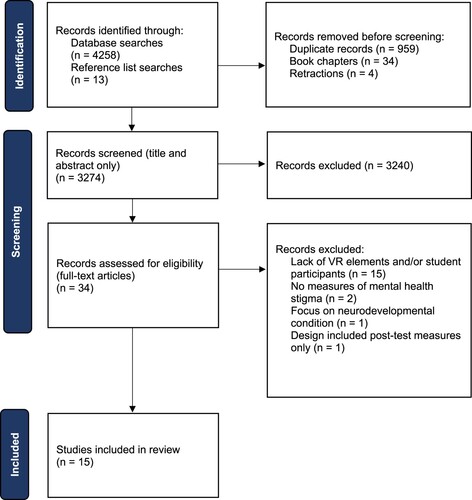

Once search results were collated and duplicates removed, titles and abstracts were screened. The full text of potentially eligible studies was then reviewed against the pre-defined eligibility criteria and the final pool of studies to be included in the systematic review was determined accordingly. A random sample of 20% of studies was cross-checked by a second researcher at both title and abstract, and full-text stages.

2.5. Data extraction. Quality appraisal

Study characteristics (e.g. sample and setting, research design), VR design (e.g. type, equipment, content, duration), and indicators of efficacy (e.g. outcomes, instruments, psychometric properties, findings, and effect sizes, if reported) were extracted from each study, then populated into a standardised table.

The Standard Quality Assessment Criteria for Evaluating Primary Research Papers (Kmet, Cook, and Lee Citation2004) was applied to appraise the quality of studies included in the review. Specifically, studies were assessed on 14 criteria, including research question, design, participant characteristics, outcome measures, analysis, and results reporting, and, where applicable, scored with ‘–’ (the study failed to meet a given criterion), ‘+’ (the study partially met a given criterion) or ‘++’ (the study fully met a given criterion). A global score for each study was also computed to determine the overall quality of research evidence, with scores closer to 1 indicating a better quality. A second researcher independently rated all eligible studies and any disagreements concerning quality ratings were resolved by consensus.

2.6. Synthesis strategy

Data were synthesised using a narrative approach and in line with best practice recommendations on the conduct of narrative synthesis in systematic reviews (Popay et al. Citation2006). This was organised around three main themes (1) study characteristics, (2) VR design, and (3) indicators of efficacy.

3. Results

A total of 4271 records were identified. Of these, 997 were removed before screening. 3274 unique records were screened based on their titles and abstract content. After records deemed irrelevant were excluded, the full text of 34 records was assessed for eligibility. In total, 15 records met the eligibility criteria and were included in the systematic review. illustrates the selection process.

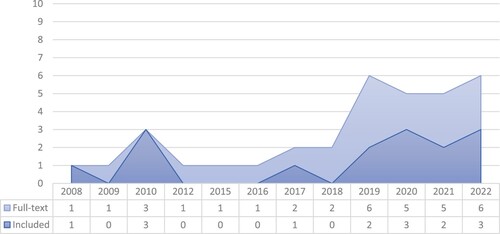

The publication years of the 34 records that were screened at full-text and the 15 records included in the review were also analysed to examine the trend of publications over time. The graph in highlights an increase in the number of publications from 2019 onwards, suggesting a growing research focus and interest in VR and mental health stigma.

Figure 2. Graph showing trends by publication year for records screened at full-text (n = 34) and records included in the review (n = 15)

3.1. Quality appraisal

All 15 studies included in the review were rated using the Standard Quality Assessment Criteria for Evaluating Primary Research Papers (Kmet, Cook, and Lee Citation2004). The results of the quality appraisal can be found in . One study demonstrated low methodological quality (global score = 0.09) and, consequently, was given less evidentiary weight. Excluding the low-quality study, global scores ranged between 0.57 and 0.89 (M = 0.71, SD = 0.09). Overall, studies in this review demonstrated moderate to high levels of quality.

Table 2. Quality appraisal results.

3.2. Study characteristics

The characteristics of each included study were summarised in . Eight studies were based on samples of healthcare students such as medicine, nursing, and psychology (Dearing and Steadman Citation2008; Kalyanaraman et al. Citation2010; Lam et al. Citation2020; Lem et al. Citation2022; Marques et al. Citation2022; Mullor et al. Citation2019; Silva et al. Citation2017; Zare-Bidaki et al. Citation2022), two studies were based on mixed samples of healthcare and non-healthcare students (Cangas et al. Citation2019; Yuen and Mak Citation2021), and five studies were based on samples of non-healthcare students (Brown Citation2010, Citation2020; Brown et al. Citation2010; Ferchaud et al. Citation2020; Stelzmann, Toth, and Schieferdecker Citation2021).

Table 3. Summary of study and VR intervention characteristics.

Two studies included thirty participants or fewer (Lem et al. Citation2022; Silva et al. Citation2017), two studies included more than thirty but fewer than a hundred participants (Dearing and Steadman Citation2008; Mullor et al. Citation2019) and eleven studies included a hundred participants or more (Brown Citation2010, Citation2020; Brown et al. Citation2010; Cangas et al. Citation2019; Ferchaud et al. Citation2020; Kalyanaraman et al. Citation2010; Lam et al. Citation2020; Marques et al. Citation2022; Stelzmann, Toth, and Schieferdecker Citation2021; Yuen and Mak Citation2021; Zare-Bidaki et al. Citation2022). These were conducted in eight different countries – six studies in the US (Brown Citation2010, Citation2020; Brown et al. Citation2010; Dearing and Steadman Citation2008; Ferchaud et al. Citation2020; Kalyanaraman et al. Citation2010), two in Spain (Cangas et al. Citation2019; Mullor et al. Citation2019), two in China (Lam et al. Citation2020; Yuen and Mak Citation2021), one in Portugal (Marques et al. Citation2022), one in Germany (Stelzmann, Toth, and Schieferdecker Citation2021), one in Brazil (Silva et al. Citation2017), one in Iran (Zare-Bidaki et al. Citation2022), and one in Japan (Lem et al. Citation2022).

All studies were experimental or quasi-experimental. Ten studies used parallel randomised controlled designs (Brown Citation2010, Citation2020; Brown et al. Citation2010; Ferchaud et al. Citation2020; Lem et al. Citation2022; Marques et al. Citation2022; Mullor et al. Citation2019; Stelzmann, Toth, and Schieferdecker Citation2021; Yuen and Mak Citation2021; Zare-Bidaki et al. Citation2022), two studies used cluster randomised controlled designs (Cangas et al. Citation2019; Dearing and Steadman Citation2008), two studies used pre–post uncontrolled designs (Lam et al. Citation2020; Silva et al. Citation2017), and one study used a factorial randomised controlled design (Kalyanaraman et al. Citation2010).

3.3. VR design

Eight studies were based on immersive VR technologies such as head-mounted displays (Kalyanaraman et al. Citation2010; Lam et al. Citation2020; Lem et al. Citation2022; Marques et al. Citation2022; Silva et al. Citation2017; Stelzmann, Toth, and Schieferdecker Citation2021; Yuen and Mak Citation2021; Zare-Bidaki et al. Citation2022), while the other seven were based on non-immersive technologies such as audio systems, game consoles or computer screens (Brown Citation2010, Citation2020; Brown et al. Citation2010; Cangas et al. Citation2019; Dearing and Steadman Citation2008; Ferchaud et al. Citation2020; Mullor et al. Citation2019). The duration of each VR intervention ranged from three minutes to one hour.

Ten VR interventions involved a first-person perspective (Brown Citation2010, Citation2020; Brown et al. Citation2010; Dearing and Steadman Citation2008; Kalyanaraman et al. Citation2010; Lam et al. Citation2020; Marques et al. Citation2022; Silva et al. Citation2017; Yuen and Mak Citation2021; Zare-Bidaki et al. Citation2022), three involved a second-person perspective (Cangas et al. Citation2019; Mullor et al. Citation2019; Stelzmann, Toth, and Schieferdecker Citation2021), and two involved a combination of first-, second-, and/or third-person perspectives (Ferchaud et al. Citation2020; Lem et al. Citation2022).

In terms of their content, three studies used serious video games (Cangas et al. Citation2019; Ferchaud et al. Citation2020; Mullor et al. Citation2019), eight used audio and/or visual simulations of mental health symptoms (Brown Citation2010, Citation2020; Brown et al. Citation2010; Dearing and Steadman Citation2008; Kalyanaraman et al. Citation2010; Marques et al. Citation2022; Silva et al. Citation2017; Zare-Bidaki et al. Citation2022), three used virtual portrayals of stigmatising experiences in different contexts (Lam et al. Citation2020; Lem et al. Citation2022; Yuen and Mak Citation2021), and one used a 360-degree video of an actor portraying a man with schizophrenia and presenting his experience with the condition (Stelzmann, Toth, and Schieferdecker Citation2021). The interventions in six studies also included educational elements about mental health (Cangas et al. Citation2019; Lam et al. Citation2020; Lem et al. Citation2022; Mullor et al. Citation2019; Yuen and Mak Citation2021; Zare-Bidaki et al. Citation2022).

Ten interventions focused on experiences of psychosis/schizophrenia (Brown Citation2010, Citation2020; Brown et al. Citation2010; Dearing and Steadman Citation2008; Ferchaud et al. Citation2020; Kalyanaraman et al. Citation2010; Marques et al. Citation2022; Silva et al. Citation2017; Stelzmann, Toth, and Schieferdecker Citation2021; Zare-Bidaki et al. Citation2022), two focused on depression and/or anxiety (Lem et al. Citation2022; Yuen and Mak Citation2021), and three focused on more than one MHC (Cangas et al. Citation2019; Lam et al. Citation2020; Mullor et al. Citation2019).

Of the 15 studies included in the review, eight studies reported the involvement of people with lived experience and other mental health experts in the design of the VR interventions (Brown Citation2010, Citation2020; Brown et al. Citation2010; Ferchaud et al. Citation2020; Kalyanaraman et al. Citation2010; Lam et al. Citation2020; Silva et al. Citation2017; Zare-Bidaki et al. Citation2022).

3.4. Indicators of efficacy

All studies used self-report instruments to evaluate the efficacy of VR interventions in reducing mental health stigma. Most studies collected data at two time points – before and after the VR intervention. Three studies also collected follow-up data at 1-week (Brown Citation2020; Brown et al. Citation2010; Yuen and Mak Citation2021). Stereotypes about mental health and/or people with MHCs were measured in ten studies (Brown Citation2010, Citation2020; Cangas et al. Citation2019; Dearing and Steadman Citation2008; Ferchaud et al. Citation2020; Kalyanaraman et al. Citation2010; Lam et al. Citation2020; Marques et al. Citation2022; Mullor et al. Citation2019; Silva et al. Citation2017). Prejudice against people with MHCs was measured in seven studies (Brown Citation2010, Citation2020; Brown et al. Citation2010; Marques et al. Citation2022; Mullor et al. Citation2019; Silva et al. Citation2017; Stelzmann, Toth, and Schieferdecker Citation2021). Discriminatory behavioural intentions towards people with MHCs were measured in ten studies (Brown Citation2010, Citation2020; Brown et al. Citation2010; Cangas et al. Citation2019; Ferchaud et al. Citation2020; Kalyanaraman et al. Citation2010; Lem et al. Citation2022; Marques et al. Citation2022; Silva et al. Citation2017; Stelzmann, Toth, and Schieferdecker Citation2021). Three studies used instruments that measured mental health stigma globally (Lem et al. Citation2022; Yuen and Mak Citation2021; Zare-Bidaki et al. Citation2022). In addition, three studies also measured changes in mental health knowledge (Lam et al. Citation2020; Marques et al. Citation2022; Zare-Bidaki et al. Citation2022).

Eleven studies assessed the psychometric properties of their measurement instruments using internal consistency analyses (Brown Citation2010, Citation2020; Brown et al. Citation2010; Cangas et al. Citation2019; Dearing and Steadman Citation2008; Ferchaud et al. Citation2020; Kalyanaraman et al. Citation2010; Lam et al. Citation2020; Mullor et al. Citation2019; Stelzmann, Toth, and Schieferdecker Citation2021; Yuen and Mak Citation2021). Most studies reported acceptable, good, or very good levels of internal consistency for stigma-related measures with Cronbach’s α ranging from .72 to .95. One study reported unacceptable levels of internal consistency for two subscales and, therefore, the authors decided to remove these from further analyses (Mullor et al. Citation2019). One study also reported the test-retest reliability of the instrument used (Dearing and Steadman Citation2008), while four studies did not report any psychometric properties for their measurement instruments (Lem et al. Citation2022; Marques et al. Citation2022; Silva et al. Citation2017; Zare-Bidaki et al. Citation2022).

As shown in , among the studies measuring stereotypes, five reported significant improvements, in that participants perceived people with MHCs more positively following the VR intervention (Cangas et al. Citation2019; Dearing and Steadman Citation2008; Kalyanaraman et al. Citation2010; Marques et al. Citation2022; Mullor et al. Citation2019), two reported significantly more negative attitudes (Brown Citation2010; Silva et al. Citation2017), and three reported non-significant changes (Brown Citation2020; Ferchaud et al. Citation2020; Lam et al. Citation2020). In terms of prejudice, one study reported significant decreases in negative emotions towards people with MHCs (Mullor et al. Citation2019), three reported significant increases (Brown et al. Citation2010; Silva et al. Citation2017; Stelzmann, Toth, and Schieferdecker Citation2021), and three reported non-significant changes (Brown Citation2010, Citation2020; Marques et al. Citation2022). Discriminatory behavioural intentions decreased significantly in four studies after the VR intervention (Cangas et al. Citation2019; Ferchaud et al. Citation2020; Mullor et al. Citation2019; Silva et al. Citation2017), three studies reported significant increases in discriminatory intentions (Brown Citation2010; Brown et al. Citation2010; Kalyanaraman et al. Citation2010), two studies reported non-significant changes (Brown Citation2020; Lem et al. Citation2022), and one reported mixed findings (Stelzmann, Toth, and Schieferdecker Citation2021). Of the studies measuring mental health stigma globally, two reported significant decreases after the VR intervention (Yuen and Mak Citation2021; Zare-Bidaki et al. Citation2022) and one reported non-significant decreases (Lem et al. Citation2022).

Table 4. Summary of study measures, instruments, and main findings.

Effect sizes were estimated using Cohen’s d, partial η2, or ω2 and the magnitude of intervention effects varied between small and large. Seven studies did not report any effect size (Dearing and Steadman Citation2008; Ferchaud et al. Citation2020; Lam et al. Citation2020; Lem et al. Citation2022; Mullor et al. Citation2019; Silva et al. Citation2017; Stelzmann, Toth, and Schieferdecker Citation2021) and one study did not specify the type of measure used to estimate the effect size (Zare-Bidaki et al. Citation2022).

4. Discussion

4.1. Summary of findings

This study aimed to systematically review the evidence concerning the use of VR as an educational tool to reduce mental health stigma in healthcare and non-healthcare students. The 15 studies included had moderate to high levels of quality with one study rated as low. The studies encompassed diverse samples of healthcare and non-healthcare students from various countries, with varying sample sizes and immersive/non-immersive VR technologies utilised. The VR interventions explored a range of perspectives, content types, and targeted MHCs, with some interventions incorporating educational elements.

The literature reviewed here generally suggests that VR interventions have the potential to reduce one or more aspects of mental health stigma among healthcare students. Embodiment, or the sense of perceiving the world from someone else’s bodily perspective, is a central feature of many VR technologies and is also thought to act as a stigma reduction mechanism (Ahn, Le, and Bailenson Citation2013). This aligns with a recent meta-analysis which found that VR-based interventions are effective at reducing mental health stigma in the general population (Rodríguez-Rivas et al. Citation2022). However, this finding was not replicated by studies among non-healthcare students, in which VR interventions were more likely to amplify stigma towards MHCs.

When discussing the divergent findings between the two student populations, it could be argued that, as healthcare students have an interest in caring for patients, including patients affected by MHCs, and might already have had some training and/or practical experience in mental health care, they endorse less stigmatising attitudes and behaviours compared to their non-healthcare counterparts, and, as a result, they would be less susceptible to the potential negative effects of a VR intervention on mental health stigma. However, while the former part may be true, the existing body of literature appears to refute the latter as healthcare and non-healthcare students tend to stigmatise people with MHCs to a largely similar extent (Ruiz et al. Citation2022; Totic et al. Citation2012). Thus, mental health stigma is more prevalent and stable than popularly believed and, even though differences might exist at the individual level, these do not necessarily translate to population-level outcomes, warranting the need for effective stigma reduction interventions in the education of all students.

A more plausible explanation is offered by the evident differences in the content and design of the various VR interventions. For instance, Brown (Citation2010) showed that a simulation of auditory hallucinations decreased participants’ willingness to help people with MHCs, and, at the same time, increased the endorsement of forced mental health treatment. Likewise, Kalyanaraman et al. (Citation2010) found that participants exposed to simulated audio-visual hallucinations in a VR environment expressed a greater desire for social distance from individuals with schizophrenia. Yet, in the study conducted by Zare-Bidaki et al. (Citation2022), although a VR simulation of hallucinations was also used, participants showed substantially lower levels of mental health stigma after taking part in the intervention. Nevertheless, in contrast with the first two studies, participants in this study were required to attend a lecture on psychosis beforehand, which might have increased their awareness and understanding of MHCs, and, ultimately, contributed to destigmatisation.

Using a different approach but eliciting the same positive results, Yuen and Mak (Citation2021) developed a VR intervention that focused on the daily challenges of people with MHCs. As with prior work (e.g. Mann and Himelein Citation2008; Norman et al. Citation2017), this suggests that replacing a symptom-centred view with a person-centred one, in which the lives of these people are put into a wider, more humane context and emphasis is placed on themes of resilience and recovery, might prove more beneficial in reducing stigma. This is consistent with earlier research which found that exposure to negative and violent media portrayals of people with MHCs increases stigmatisation, while positive, sympathetic portrayals result in more favourable attitudes (Rubenking and Bracken Citation2015). In turn, as Ando et al. (Citation2011) also reasoned, the mere exposure to simulated symptoms of MHCs may be, in fact, counterproductive – especially if no contextual information or educational content is provided. Therefore, it should not be unexpected that students with no or little understanding of MHCs would express more stigmatising attitudes immediately after listening to a distressing voice-hearing simulation.

Another interesting point is that VR interventions based on non-immersive technologies showed results comparable to those based on immersive technologies, suggesting that embodiment may be as effective as other stigma reduction strategies (e.g. virtual contact) as long as they induce the same degree of transportation into the character’s world. Transportation refers to a mental process whereby one becomes cognitively and affectively immersed in a fictional or non-fictional narrative (Green and Brock Citation2000) and has been associated with changes in stigma-related attitudes (Caputo and Rouner Citation2011; Ferchaud et al. Citation2020; Oliver et al. Citation2012). Therefore, although VR technologies such as head-mounted displays can create a physical sense of immersion (Chessa et al. Citation2019; Shu et al. Citation2019), this alone may not be sufficient to enable a greater degree of transportation. What is clear, however, is that interventions tend to be more successful when multiple stigma reduction strategies are employed, echoing findings from other reviews (e.g. Bielenberg et al. Citation2021; Doley et al. Citation2017).

Then, to assess the true efficacy of VR interventions, the selection of suitable outcomes is fundamental as these must correspond with the intended mechanisms of change (Coster Citation2013). In this case, most studies looked at changes in discrete elements of mental health stigma, recognising, therefore, the multifaceted nature of the construct which may be influenced differently by different components of an intervention (Morgan et al. Citation2018; Ungar, Knaak, and Szeto Citation2016). Indeed, stereotypes and discriminatory intentions were more likely to change than prejudice as a result of the interventions. As Na et al. (Citation2022) explained, and consistent with their findings, stigma reduction interventions may be more effective at reducing cognitive but not affective elements of mental health stigma. This can be problematic since affective responses are arguably more predictive of actual discriminatory behaviour than intentions are (Corrigan et al. Citation2003).

4.2. Limitations of the included studies

Although the research reviewed here was rated as having at least moderate quality, it is essential to acknowledge some methodological limitations that could have affected study findings and their interpretations. Firstly, studies in this review relied heavily on self-report instruments to assess changes in mental health stigma, leaving room for social desirability bias. While self-report measures are able to capture explicit aspects of stigma, that is not the case for affective reactions or actual behaviour toward stigmatised groups, which may, in fact, be inconsistent with explicitly expressed attitudes or intentions (Corrigan et al. Citation2003; Kopera et al. Citation2015). Secondly, in an attempt to report potential confounders, the vast majority of studies tended to solely focus on demographic characteristics, such as age and gender. However, less consideration was given to more contextually salient factors, including previous contact with people with MHCs, personal history of MHCs, or mental health literacy, which had been found to influence mental health stigma (Eack and Newhill Citation2008; Moreira, Oura, and Santos Citation2021; Rüsch et al. Citation2011). Thirdly, almost none of the studies included in this review reported the blinding status of their participants, which is a prevalent concern among randomised studies of psychological and/or behavioural interventions (Juul et al. Citation2021).

4.3. Strengths and limitations of the review process

This systematic review presents several strengths. Firstly, the search strategy and eligibility criteria were pre-registered in a publicly available database. This improves the transparency of the review process and allows other researchers to easily replicate the literature search. Secondly, both specialised and general databases were searched, which potentially increased the probability of retrieving relevant studies. Thirdly, to enhance accuracy and objectivity, the screening and quality assessment results were cross-checked by external researchers. Lastly, for consistency, as well as replicability purposes, the structure and content of this systematic review closely followed the well-established PRISMA reporting standards.

Some limitations of the review process should also be noted. Firstly, only English publications were taken into account, potentially missing research written in other languages. Then, as the literature search was limited to peer-reviewed publications, any other type of work was automatically excluded from the review. Publication bias represents a particular issue that readers should be aware of when interpreting the findings of this systematic review. As a third and final limitation, studies varied substantially in the way they measured mental health stigma, but also in the type, content, and length of VR interventions, thus meta-analysis was not a suitable method for synthesising the data quantitively. In consequence, the evidence behind the effectiveness of VR interventions to reduce mental health stigma in healthcare and non-healthcare students should be treated with caution until more research efforts addressing existing limitations are made and a pooled statistic can be calculated.

4.4. Implications. Conclusion

The findings of this systematic review yield a number of preliminary but important implications for healthcare education research and practice. As advancements in VR technologies continue to be made, these become more and more accessible, and, as a result, find extensive applications in the real world. Healthcare is no exception with VR technologies being increasingly used in the education of healthcare professionals (Kyaw et al. Citation2019; Mäkinen et al. Citation2022; Ruthenbeck and Reynolds Citation2015). Beyond the teaching of clinical skills, the possibility offered by VR technologies to easily adjust aspects of reality and induce a sense of presence has started to be explored even more in recent years, which has led to the use of VR as an educational tool to tackle psychosocial aspects of healthcare such as mental health stigma (Riches et al. Citation2022). In these interventions, the healthcare student has the opportunity to watch, interact with, or even embody characters with MHCs and understand their symptoms, but also to obtain insight into their daily challenges in different scenarios.

As the current body of knowledge appears to suggest, VR interventions can reduce one or more aspects of mental health stigma, supporting its use in the education of healthcare students. Future work is, however, needed to evaluate the comparative effectiveness of immersive and non-immersive VR technologies and to better understand the underlying mechanisms of stigma change. At the same time, even though existing studies demonstrate the short-term efficacy of VR interventions in reducing mental health stigma, more studies should investigate whether these effects are maintained in the long run by collecting longitudinal, follow-up data.

Nonetheless, it is unquestionable that, in order to enhance their success, healthcare educators should not use VR interventions as a one-off activity but rather as part of a wider anti-stigma programme, in which interventions such as education and contact are also being offered. Additionally, the involvement of individuals with lived experience and their families/carers in the design of VR interventions targeted at reducing mental health stigma should be a priority as they can ensure that the virtually generated scenarios are reflective of their actual experiences and are not mere stereotypical or exaggerated portrayals of mental illness.

Furthermore, mental health stigma is believed to be condition-specific (Carrara et al. Citation2021; Krendl and Freeman Citation2019), thus future VR interventions may benefit more from focusing on a specified MHC and evaluating stigma changes concerning that condition. On that note, while much work already exists on psychosis/schizophrenia, little attention has been paid to other MHCs such as substance abuse, disordered eating, or bipolar disorder, which are often characterised by high levels of physical comorbidity and poor clinical outcomes (Keaney et al. Citation2011; Olguin et al. Citation2017; Young and Grunze Citation2013).

Lastly, as there was great variation in reporting the design and development of VR interventions, efforts should be made to improve reporting consistency across studies. In that sense, standardised guidelines (e.g. Duncan et al. Citation2020; Möhler, Köpke, and Meyer Citation2015) can be used to describe transparently and consistently the key elements and stages in the process of designing VR interventions, maximising the possibility of making fair between-study comparisons and carrying out replications.

All in all, while the current body of evidence has some methodological drawbacks, there should be optimism that, as VR technologies advance, more and better research outputs will be generated, further strengthening the state of knowledge around the novel role of VR in tackling mental health stigma both within and outside of healthcare education.

Acknowledgements

We thank Fatima Ozeto (University of Surrey) and Ciprian Ciobanu (Birkbeck, University of London) for assisting with this systematic review.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

Data availability is not applicable to this article as no new data were created or analysed in this study.

References

- Ahmed, N., P. Barnett, A. Greenburgh, T. Pemovska, T. Stefanidou, N. Lyons, S. Ikhtabi, et al. 2023. “Mental Health in Europe during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Systematic Review.” The Lancet Psychiatry 10 (7): 537–556. Advanced online publication. https://doi.org/10.1016/s2215-0366(23)00113-x.

- Ahn, S. J. (Grace), A. M. T. Le, and J. Bailenson. 2013. “The Effect of Embodied Experiences on Self-Other Merging, Attitude, and Helping Behavior.” Media Psychology 16 (1): 7–38. https://doi.org/10.1080/15213269.2012.755877.

- Ando, S., S. Clement, E. A. Barley, and G. Thornicroft. 2011. “The Simulation of Hallucinations to Reduce the Stigma of Schizophrenia: A Systematic Review.” Schizophrenia Research 133 (1): 8–16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.schres.2011.09.011.

- Arvaniti, A., M. Samakouri, E. Kalamara, V. Bochtsou, C. Bikos, and M. Livaditis. 2009. “Health Service Staff’s Attitudes towards Patients with Mental Illness.” Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology 44 (8): 658–665. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-008-0481-3.

- Baghaei, N., V. Chitale, A. Hlasnik, L. Stemmet, H. N. Liang, and R. Porter. 2021. “Virtual Reality for Supporting the Treatment of Depression and Anxiety: Scoping Review.” JMIR Mental Health 8 (9): e29681. https://doi.org/10.2196/29681.

- Bielenberg, J., G. Swisher, A. Lembke, and N. A. Haug. 2021. “A Systematic Review of Stigma Interventions for Providers Who Treat Patients with Substance Use Disorders.” Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment 131:108486. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsat.2021.108486.

- Boardman, J. 2011. “Social Exclusion and Mental Health – How People with Mental Health Problems Are Disadvantaged: An Overview.” Mental Health and Social Inclusion 15 (3): 112–121. https://doi.org/10.1108/20428301111165690.

- Brouwers, E. P. M., J. Mathijssen, T. V. Bortel, L. Knifton, K. Wahlbeck, C. V. Audenhove, N. Kadri, et al. 2016. “Discrimination in the Workplace, Reported by People with Major Depressive Disorder: A Cross-Sectional Study in 35 Countries.” BMJ Open 6 (2): e009961. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2015-009961.

- Brown, S. 2010. “Implementing a Brief Hallucination Simulation as a Mental Illness Stigma Reduction Strategy.” Community Mental Health Journal 46 (5): 500–504. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10597-009-9229-0.

- Brown, S. 2020. “The Effectiveness of Two Potential Mass Media Interventions on Stigma: Video-Recorded Social Contact and Audio/Visual Simulations.” Community Mental Health Journal 56 (3): 471–477. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10597-019-00503-8.

- Brown, S., Y. Evans, K. Espenschade, and M. O’Connor. 2010. “An Examination of Two Brief Stigma Reduction Strategies: Filmed Personal Contact and Hallucination Simulations.” Community Mental Health Journal 46 (5): 494–499. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10597-010-9309-1.

- Browne, G., and M. Courtney. 2007. “Schizophrenia Housing and Supportive Relationships.” International Journal of Mental Health Nursing 16 (2): 73–80. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1447-0349.2006.00447.x.

- Cangas, A., N. Navarro, J. M. Aguilar-Parra, R. Trigueros, J. Gallego, R. Zárate, and M. Gregg. 2019. “Analysis of the Usefulness of a Serious Game to Raise Awareness about Mental Health Problems in a Sample of High School and University Students: Relationship with Familiarity and Time Spent Playing Video Games.” Journal of Clinical Medicine 8 (10): 1504. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm8101504.

- Caputo, N. M., and D. Rouner. 2011. “Narrative Processing of Entertainment Media and Mental Illness Stigma.” Health Communication 26 (7): 595–604. https://doi.org/10.1080/10410236.2011.560787.

- Carrara, B. S., R. H. H. Fernandes, S. J. Bobbili, and C. A. A. Ventura. 2021. “Health Care Providers and People with Mental Illness: An Integrative Review on Anti-Stigma Interventions.” International Journal of Social Psychiatry 67 (7): 840–853. https://doi.org/10.1177/0020764020985891.

- Chessa, M., G. Maiello, A. Borsari, and P. J. Bex. 2019. “The Perceptual Quality of the Oculus Rift for Immersive Virtual Reality.” Human–Computer Interaction 34 (1): 51–82. https://doi.org/10.1080/07370024.2016.1243478.

- Chitale, V., N. Baghaei, D. Playne, H. N. Liang, Y. Zhao, A. Erensoy, and Y. Ahmad. 2022. “The Use of Videogames and Virtual Reality for the Assessment of Anxiety and Depression: A Scoping Review.” Games for Health Journal 11 (6): 341–354. https://doi.org/10.1089/g4h.2021.0227.

- Christofi, M., and D. Michael-Grigoriou. 2017. “Virtual Reality for Inducing Empathy and Reducing Prejudice towards Stigmatized Groups: A Survey.” 2017 23rd International Conference on Virtual System & Multimedia (VSMM), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1109/VSMM.2017.8346252.

- Clement, S., O. Schauman, T. Graham, F. Maggioni, S. Evans-Lacko, N. Bezborodovs, C. Morgan, N. Rüsch, J. S. L. Brown, and G. Thornicroft. 2015. “What Is the Impact of Mental Health-Related Stigma on Help-Seeking? A Systematic Review of Quantitative and Qualitative Studies.” Psychological Medicine 45 (1): 11–27. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291714000129.

- Clus, D., M. E. Larsen, C. Lemey, and S. Berrouiguet. 2018. “The Use of Virtual Reality in Patients with Eating Disorders: Systematic Review.” Journal of Medical Internet Research 20 (4): e157. https://doi.org/10.2196/jmir.7898.

- Corrigan, P. W. 2000. “Mental Health Stigma as Social Attribution: Implications for Research Methods and Attitude Change.” Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice 7:48–67. https://doi.org/10.1093/clipsy.7.1.48.

- Corrigan, P., F. E. Markowitz, A. Watson, D. Rowan, and M. A. Kubiak. 2003. “An Attribution Model of Public Discrimination towards Persons with Mental Illness.” Journal of Health and Social Behavior 44 (2): 162–179. https://doi.org/10.2307/1519806.

- Corrigan, P. W., D. Mittal, C. M. Reaves, T. F. Haynes, X. Han, S. Morris, and G. Sullivan. 2014. “Mental Health Stigma and Primary Health Care Decisions.” Psychiatry Research 218 (1): 35–38. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2014.04.028.

- Corrigan, P. W., and D. L. Penn. 1999. “Lessons from Social Psychology on Discrediting Psychiatric Stigma.” American Psychologist 54:765–776. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.54.9.765.

- Coster, W. J. 2013. “Making the Best Match: Selecting Outcome Measures for Clinical Trials and Outcome Studies.” The American Journal of Occupational Therapy 67 (2): 162–170. https://doi.org/10.5014/ajot.2013.006015.

- Dearing, K. S., and S. Steadman. 2008. “Challenging Stereotyping and Bias: A Voice Simulation Study.” Journal of Nursing Education 47 (2): 59–65. https://doi.org/10.3928/01484834-20080201-07.

- Doley, J. R., L. M. Hart, A. A. Stukas, K. Petrovic, A. Bouguettaya, and S. J. Paxton. 2017. “Interventions to Reduce the Stigma of Eating Disorders: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis.” International Journal of Eating Disorders 50 (3): 210–230. https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.22691.

- Duncan, E., A. O’Cathain, N. Rousseau, L. Croot, K. Sworn, K. M. Turner, L. Yardley, and P. Hoddinott. 2020. “Guidance for Reporting Intervention Development Studies in Health Research (GUIDED): An Evidence-Based Consensus Study.” BMJ Open 10 (4): e033516. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2019-033516.

- Eack, S. M., and C. E. Newhill. 2008. “An Investigation of the Relations between Student Knowledge, Personal Contact, and Attitudes toward Individuals with Schizophrenia.” Journal of Social Work Education 44 (3): 77–96. https://doi.org/10.5175/JSWE.2008.200700009.

- Eaton, W. W., S. S. Martins, G. Nestadt, O. J. Bienvenu, D. Clarke, and P. Alexandre. 2008. “The Burden of Mental Disorders.” Epidemiologic Reviews 30 (1): 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1093/epirev/mxn011.

- Ferchaud, A., J. Seibert, N. Sellers, and N. Escobar Salazar. 2020. “Reducing Mental Health Stigma through Identification with Video Game Avatars with Mental Illness.” Frontiers in Psychology 11. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.02240.

- Green, M. C., and T. C. Brock. 2000. “The Role of Transportation in the Persuasiveness of Public Narratives.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 79 (5): 701–721. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.79.5.701.

- Hand, C., R. Olaiya, and M. Elmasry. 2020. “Virtual Reality for Teaching Clinical Skills in Medical Education.” In New Perspectives on Virtual and Augmented Reality, edited by L. Daniela, 1st ed., 203–210. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Henderson, C., J. Noblett, H. Parke, S. Clement, A. Caffrey, O. Gale-Grant, B. Schulze, B. Druss, and G. Thornicroft. 2014. “Mental Health-Related Stigma in Health Care and Mental Health-Care Settings.” The Lancet Psychiatry 1 (6): 467–482. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(14)00023-6.

- Jorm, A. F., and E. Oh. 2009. “Desire for Social Distance from People with Mental Disorders.” Australian & New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry 43 (3): 183–200. https://doi.org/10.1080/00048670802653349.

- Juul, S., C. Gluud, S. Simonsen, F. W. Frandsen, I. Kirsch, and J. C. Jakobsen. 2021. “Blinding in Randomised Clinical Trials of Psychological Interventions: A Retrospective Study of Published Trial Reports.” BMJ Evidence-Based Medicine 26 (3): 109–109. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjebm-2020-111407.

- Kalyanaraman, S. S., D. L. Penn, J. D. Ivory, and A. Judge. 2010. “The Virtual Doppelganger: Effects of a Virtual Reality Simulator on Perceptions of Schizophrenia.” Journal of Nervous & Mental Disease 198 (6): 437–443. https://doi.org/10.1097/NMD.0b013e3181e07d66.

- Kamaradova, D., K. Latalova, J. Prasko, R. Kubinek, K. Vrbova, B. Mainerova, A. Cinculova, et al. 2016. “Connection between Self-Stigma, Adherence to Treatment, and Discontinuation of Medication.” Patient Preference and Adherence 10:1289–1298. https://doi.org/10.2147/PPA.S99136.

- Keaney, F., M. Gossop, A. Dimech, I. Guerrini, M. Butterworth, H. Al-Hassani, and A. Morinan. 2011. “Physical Health Problems among Patients Seeking Treatment for Substance use Disorders: A Comparison of Drug Dependent and Alcohol Dependent Patients.” Journal of Substance Use 16 (1): 27–37. https://doi.org/10.3109/14659890903580474.

- Kmet, L. M., L. S. Cook, and R. C. Lee. 2004. “Standard Quality Assessment Criteria for Evaluating Primary Research Papers from a Variety of Fields.” Alberta Heritage Foundation for Medical Research. https://doi.org/10.7939/R37M04F16.

- Kopera, M., H. Suszek, E. Bonar, M. Myszka, B. Gmaj, M. Ilgen, and M. Wojnar. 2015. “Evaluating Explicit and Implicit Stigma of Mental Illness in Mental Health Professionals and Medical Students.” Community Mental Health Journal 51 (5): 628–634. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10597-014-9796-6.

- Kothgassner, O. D., A. Goreis, J. X. Kafka, R. L. Van Eickels, P. L. Plener, and A. Felnhofer. 2019. “Virtual Reality Exposure Therapy for Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD): A Meta-Analysis.” European Journal of Psychotraumatology 10 (1): 1654782. https://doi.org/10.1080/20008198.2019.1654782.

- Krendl, A. C., and J. B. Freeman. 2019. “Are Mental Illnesses Stigmatized for the Same Reasons? Identifying the Stigma-Related Beliefs Underlying Common Mental Illnesses.” Journal of Mental Health 28 (3): 267–275. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638237.2017.1385734.

- Kyaw, B. M., N. Saxena, P. Posadzki, J. Vseteckova, C. K. Nikolaou, P. P. George, U. Divakar, et al. 2019. “Virtual Reality for Health Professions Education: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis by the Digital Health Education Collaboration.” Journal of Medical Internet Research 21 (1): e12959. https://doi.org/10.2196/12959.

- Lam, A. H. Y., J. J. Lin, A. W. H. Wan, and J. Y. H. Wong. 2020. “Enhancing Empathy and Positive Attitude among Nursing Undergraduates via an in-Class Virtual Reality-Based Simulation Relating to Mental Illness.” Journal of Nursing Education and Practice 10 (11): 1–9. https://doi.org/10.5430/jnep.v10n11p1.

- Lem, W. G., A. Kohyama-Koganeya, T. Saito, and H. Oyama. 2022. “Effect of a Virtual Reality Contact-Based Educational Intervention on the Public Stigma of Depression: Randomized Controlled Pilot Study.” JMIR Formative Research 6 (5): e28072. https://doi.org/10.2196/28072.

- Lien, Y.-Y., H.-S. Lin, Y.-J. Lien, C.-H. Tsai, T.-T. Wu, H. Li, and Y.-K. Tu. 2021. “Challenging Mental Illness Stigma in Healthcare Professionals and Students: A Systematic Review and Network Meta-Analysis.” Psychology & Health 36 (6): 669–684. https://doi.org/10.1080/08870446.2020.1828413.

- Lin, Chung-Ying, Chih-Cheng Chang, Tsung-Hsien Wu, and Jung-Der Wang. 2016. “Dynamic changes of self-stigma, quality of life, somatic complaints, and depression among people with schizophrenia: A pilot study applying kernel smoothers.” Stigma and Health 1 (1): 29–43. https://doi.org/10.1037/sah0000014.

- Ma, M., and H. Zheng. 2011. “Virtual Reality and Serious Games in Healthcare.” In Advanced Computational Intelligence Paradigms in Healthcare 6. Virtual Reality in Psychotherapy, Rehabilitation, and Assessment, edited by S. Brahnam and L. C. Jain, 169–192. Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-17824-5_9.

- Mäkinen, H., E. Haavisto, S. Havola, and J. M. Koivisto. 2022. “User Experiences of Virtual Reality Technologies for Healthcare in Learning: An Integrative Review.” Behaviour & Information Technology 41 (1): 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/0144929X.2020.1788162.

- Mann, C. E., and M. J. Himelein. 2008. “Putting the Person Back into Psychopathology: An Intervention to Reduce Mental Illness Stigma in the Classroom.” Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology 43 (7): 545–551. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-008-0324-2.

- Marques, A. J., P. Gomes Veloso, M. Araújo, R. S. de Almeida, A. Correia, J. Pereira, C. Queiros, R. Pimenta, A. S. Pereira, and C. F. Silva. 2022. “Impact of a Virtual Reality-Based Simulation on Empathy and Attitudes toward Schizophrenia.” Frontiers in Psychology 13. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.814984.

- Martínez-Martínez, C., V. Sánchez-Martínez, R. Sales-Orts, A. Dinca, M. Richart-Martínez, and J. D. Ramos-Pichardo. 2019. “Effectiveness of Direct Contact Intervention with People with Mental Illness to Reduce Stigma in Nursing Students.” International Journal of Mental Health Nursing 28 (3): 735–743. https://doi.org/10.1111/inm.12578.

- Mason, J., and K. Scior. 2004. “Diagnostic Overshadowing’ amongst Clinicians Working with People with Intellectual Disabilities in the UK.” Journal of Applied Research in Intellectual Disabilities 17 (2): 85–90. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1360-2322.2004.00184.x.

- Maunder, R. D., and F. A. White. 2019. “Intergroup Contact and Mental Health Stigma: A Comparative Effectiveness Meta-Analysis.” Clinical Psychology Review 72:101749. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2019.101749.

- McCullock, S. P., and R. M. Scrivano. 2023. “The Effectiveness of Mental Illness Stigma-Reduction Interventions: A Systematic Meta-Review of Meta-Analyses.” Clinical Psychology Review 100:102242. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2022.102242.

- McManus, S., P. E. Bebbington, R. Jenkins, and T. Brugha. 2016. Mental Health and Wellbeing in England: The Adult Psychiatric Morbidity Survey 2014. NHS Digital. https://files.digital.nhs.uk/pdf/q/3/mental_health_and_wellbeing_in_england_full_report.pdf.

- Minas, H., R. Zamzam, M. Midin, and A. Cohen. 2011. “Attitudes of Malaysian General Hospital Staff towards Patients with Mental Illness and Diabetes.” BMC Public Health 11 (1): 317. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-11-317.

- Mitchell, A. J., D. Malone, and C. C. Doebbeling. 2009. “Quality of Medical Care for People with and without Comorbidmental Illness and Substance Misuse: Systematic Review of Comparativestudies.” British Journal of Psychiatry 194 (6): 491–499. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.bp.107.045732.

- Möhler, R., S. Köpke, and G. Meyer. 2015. “Criteria for Reporting the Development and Evaluation of Complex Interventions in Healthcare: Revised Guideline (CReDECI 2).” Trials 16 (1): 204. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13063-015-0709-y.

- Moreira, A.-R., M.-J. Oura, and P. Santos. 2021. “Stigma about Mental Disease in Portuguese Medical Students: A Cross-Sectional Study.” BMC Medical Education 21 (1): 265. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-021-02714-8.

- Morgan, A. J., N. J. Reavley, A. Ross, L. S. Too, and A. F. Jorm. 2018. “Interventions to Reduce Stigma towards People with Severe Mental Illness: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis.” Journal of Psychiatric Research 103:120–133. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpsychires.2018.05.017.

- Mullor, D., P. Sayans-Jiménez, A. J. Cangas, and N. Navarro. 2019. “Effect of a Serious Game (Stigma-Stop) on Reducing Stigma Among Psychology Students: A Controlled Study.” Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking 22 (3): 205–211. https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2018.0172.

- Na, J. J., J. L. Park, T. LKhagva, and A. Y. Mikami. 2022. “The Efficacy of Interventions on Cognitive, Behavioral, and Affective Public Stigma around Mental Illness: A Systematic Meta-Analytic Review.” Stigma and Health 7 (2): 127–141. https://doi.org/10.1037/sah0000372.

- Norman, R. M. G., Y. Li, R. Sorrentino, E. Hampson, and Y. Ye. 2017. “The Differential Effects of a Focus on Symptoms versus Recovery in Reducing Stigma of Schizophrenia.” Social Psychiatry and Psychiatric Epidemiology 52 (11): 1385–1394. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00127-017-1429-2.

- Olguin, P., M. Fuentes, G. Gabler, A. I. Guerdjikova, P. E. Keck, and S. L. McElroy. 2017. “Medical Comorbidity of Binge Eating Disorder.” Eating and Weight Disorders - Studies on Anorexia, Bulimia and Obesity 22 (1): 13–26. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40519-016-0313-5.

- Oliveira, A. M., D. Machado, J. B. Fonseca, F. Palha, P. Silva Moreira, N. Sousa, J. J. Cerqueira, and P. Morgado. 2020. “Stigmatizing Attitudes toward Patients with Psychiatric Disorders among Medical Students and Professionals.” Frontiers in Psychiatry 11. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2020.00326.

- Oliver, M. B., J. P. Dillard, K. Bae, and D. J. Tamul. 2012. “The Effect of Narrative News Format on Empathy for Stigmatized Groups.” Journalism & Mass Communication Quarterly 89 (2): 205–224. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077699012439020.

- Page, M. J., J. E. McKenzie, P. M. Bossuyt, I. Boutron, T. C. Hoffmann, C. D. Mulrow, L. Shamseer, J. M. Tetzlaff, and D. Moher. 2021. “Updating Guidance for Reporting Systematic Reviews: Development of the PRISMA 2020 Statement.” Journal of Clinical Epidemiology 134:103–112. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclinepi.2021.02.003.

- Peterson, D., L. Pere, N. Sheehan, and G. Surgenor. 2006. “Experiences of Mental Health Discrimination in New Zealand.” Health and Social Care in the Community 15 (1): 18–25. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2524.2006.00657.x.

- Popay, J., H. Roberts, A. Sowden, M. Petticrew, L. Arai, M. Rodgers, N. Britten, K. Roen, and S. Duffy. 2006. Guidance on the Conduct of Narrative Synthesis in Systematic Reviews: A Product from the ESRC Methods Programme. https://www.lancaster.ac.uk/media/lancaster-university/content-assets/documents/fhm/dhr/chir/NSsynthesisguidanceVersion1-April2006.pdf.

- Pursehouse, L. 2023. “Health-Care Undergraduate Student’s Attitudes towards Mental Illness Following Anti-Stigma Education: A Critical Review of the Literature.” The Journal of Mental Health Training, Education and Practice 18 (2): 111–122. https://doi.org/10.1108/JMHTEP-09-2021-0112.

- Riches, S., H. Iannelli, L. Reynolds, H. L. Fisher, S. Cross, and C. Attoe. 2022. “Virtual Reality-Based Training for Mental Health Staff: A Novel Approach to Increase Empathy, Compassion, and Subjective Understanding of Service User Experience.” Advances in Simulation 7 (1): 19. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41077-022-00217-0.

- Robinson, E., A. R. Sutin, M. Daly, and A. Jones. 2022. “A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Longitudinal Cohort Studies Comparing Mental Health Before versus during the COVID-19 Pandemic in 2020.” Journal of Affective Disorders 296:567–576. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2021.09.098.

- Rodríguez-Rivas, M. E., A. J. Cangas, L. A. Cariola, J. J. Varela, and S. Valdebenito. 2022. “Innovative Technology–Based Interventions to Reduce Stigma toward People with Mental Illness: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis.” JMIR Serious Games 10 (2): e35099. https://doi.org/10.2196/35099.

- Rubenking, B., and C. Bracken. 2015. “The Dueling Influences on Stigma toward Mental Illness: Effects of Interpersonal Familiarity and Stigmatizing Mediated Portrayals of Mental Illness on Attitudes.” Studies in Media and Communication 3 (2): 120–128. https://doi.org/10.11114/smc.v3i2.1130.

- Ruiz, J. C., I. Fuentes-Durá, M. López-Gilberte, C. Dasí, C. Pardo-García, M. C. Fuentes-Durán, F. Pérez-González, et al. 2022. “Public Stigma Profile toward Mental Disorders across Different University Degrees in the University of Valencia (Spain).” Frontiers in Psychiatry 13. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2022.951894.

- Rüsch, N., S. E. Evans-Lacko, C. Henderson, C. Flach, and G. Thornicroft. 2011. “Knowledge and Attitudes as Predictors of Intentions to Seek Help for and Disclose a Mental Illness.” Psychiatric Services 62 (6): 675–678. https://doi.org/10.1176/ps.62.6.pss6206_0675.

- Ruthenbeck, G. S., and K. J. Reynolds. 2015. “Virtual Reality for Medical Training: The State-of-the-Art.” Journal of Simulation 9 (1): 16–26. https://doi.org/10.1057/jos.2014.14.

- Sanchez-Vives, M. V., and M. Slater. 2005. “From Presence to Consciousness through Virtual Reality.” Nature Reviews Neuroscience 6 (4): 332–339. https://doi.org/10.1038/nrn1651.

- Schnyder, N., R. Panczak, N. Groth, and F. Schultze-Lutter. 2017. “Association between Mental Health-Related Stigma and Active Help-Seeking: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis.” British Journal of Psychiatry 210 (4): 261–268. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.bp.116.189464.

- Schroeder, A. H., B. J. Bogie, T. T. Rahman, A. Thérond, H. Matheson, and S. Guimond. 2022. “Feasibility and Efficacy of Virtual Reality Interventions to Improve Psychosocial Functioning in Psychosis: Systematic Review.” JMIR Mental Health 9 (2): e28502. https://doi.org/10.2196/28502.

- Sharac, J., P. Mccrone, S. Clement, and G. Thornicroft. 2010. “The Economic Impact of Mental Health Stigma and Discrimination: A Systematic Review.” Epidemiologia e Psichiatria Sociale 19 (3): 223–232. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1121189X00001159.

- Shefer, G., C. Henderson, L. M. Howard, J. Murray, and G. Thornicroft. 2014. “Diagnostic Overshadowing and Other Challenges Involved in the Diagnostic Process of Patients with Mental Illness Who Present in Emergency Departments with Physical Symptoms – A Qualitative Study.” PLoS ONE 9 (11): e111682. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0111682.

- Shu, Y., Y.-Z. Huang, S.-H. Chang, and M.-Y. Chen. 2019. “Do Virtual Reality Head-Mounted Displays Make a Difference? A Comparison of Presence and Self-Efficacy between Head-Mounted Displays and Desktop Computer-Facilitated Virtual Environments.” Virtual Reality 23 (4): 437–446. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10055-018-0376-x.

- Silva, R. D. de C., S. G. C. Albuquerque, A. de V. Muniz, P. P. R. Filho, S. Ribeiro, P. R. Pinheiro, and V. H. C. Albuquerque. 2017. “Reducing the Schizophrenia Stigma: A New Approach Based on Augmented Reality.” Computational Intelligence and Neuroscience 2017:2721846. https://doi.org/10.1155/2017/2721846.

- Stelzmann, D., R. Toth, and D. Schieferdecker. 2021. “Can Intergroup Contact in Virtual Reality (VR) Reduce Stigmatization against People with Schizophrenia?” Journal of Clinical Medicine 10 (13): Article 13. https://doi.org/10.3390/jcm10132961.

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. 2021. Key Substance Use and Mental Health Indicators in the United States: Results from the 2020 National Survey on Drug Use and Health. Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality. https://www.samhsa.gov/data/data-we-collect/nsduh-national-survey-drug-use-and-health.

- Thornicroft, G. 2007. “Most People with Mental Illness Are Not Treated.” The Lancet 370 (9590): 807–808. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61392-0.

- Thornicroft, G. 2011. “Physical Health Disparities and Mental Illness: The Scandal of Premature Mortality.” British Journal of Psychiatry 199 (6): 441–442. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.bp.111.092718.

- Thornicroft, G., D. Rose, and A. Kassam. 2007. “Discrimination in Health Care against People with Mental Illness.” International Review of Psychiatry 19 (2): 113–122. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540260701278937.

- Thornicroft, G., D. Rose, and N. Mehta. 2010. “Discrimination against People with Mental Illness: What Can Psychiatrists Do?” Advances in Psychiatric Treatment 16 (1): 53–59. https://doi.org/10.1192/apt.bp.107.004481.

- Thornicroft, G., C. Sunkel, A. A. Aliev, S. Baker, E. Brohan, R. El Chammay, K. Davies, et al. 2022. “The Lancet Commission on Ending Stigma and Discrimination in Mental Health.” The Lancet 400 (10361): 1438–1480. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(22)01470-2.

- Totic, S., D. Stojiljković, Z. Pavlovic, N. Zaric, B. Zarkovic, L. Malic, M. Mihaljevic, M. Jašović-Gašić, and N. P. Marić. 2012. “Stigmatization of ‘Psychiatric Label’ by Medical and Non-Medical Students.” International Journal of Social Psychiatry 58 (5): 455–462. https://doi.org/10.1177/0020764011408542.

- Uhlmann, C., J. Kaehler, M. S. H. Harris, J. Unser, V. Arolt, and R. Lencer. 2014. “Negative Impact of Self-Stigmatization on Attitude toward Medication Adherence in Patients with Psychosis.” Journal of Psychiatric Practice 20 (5): 405–410. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.pra.0000454787.75106.ae.

- Ungar, T., S. Knaak, and A. C. Szeto. 2016. “Theoretical and Practical Considerations for Combating Mental Illness Stigma in Health Care.” Community Mental Health Journal 52 (3): 262–271. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10597-015-9910-4.

- Vigo, D., G. Thornicroft, and R. Atun. 2016. “Estimating the True Global Burden of Mental Illness.” The Lancet Psychiatry 3 (2): 171–178. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(15)00505-2.

- Vistorte, A. O. R., W. S. Ribeiro, D. Jaen, M. R. Jorge, S. Evans-Lacko, and Jair de J. Mari. 2018. “Stigmatizing Attitudes of Primary Care Professionals towards People with Mental Disorders: A Systematic Review.” The International Journal of Psychiatry in Medicine 53 (4): 317–338. https://doi.org/10.1177/0091217418778620.

- Watson, A. C., P. Corrigan, J. E. Larson, and M. Sells. 2006. “Self-Stigma in People with Mental Illness.” Schizophrenia Bulletin 33 (6): 1312–1318. https://doi.org/10.1093/schbul/sbl076.

- WHO (World Health Organization). 2022. World Mental Health Report: Transforming Mental Health for all. World Health Organization. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240049338.

- Wittchen, H. U., F. Jacobi, J. Rehm, A. Gustavsson, M. Svensson, B. Jönsson, J. Olesen, et al. 2011. “The Size and Burden of Mental Disorders and Other Disorders of the Brain in Europe 2010.” European Neuropsychopharmacology 21 (9): 655–679. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.euroneuro.2011.07.018.

- Yamaguchi, S., Y. Mino, and S. Uddin. 2011. “Strategies and Future Attempts to Reduce Stigmatization and Increase Awareness of Mental Health Problems among Young People: A Narrative Review of Educational Interventions.” Psychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences 65 (5): 405–415. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1440-1819.2011.02239.x.

- Yamaguchi, S., S.-I. Wu, M. Biswas, M. Yate, Y. Aoki, E. A. Barley, and G. Thornicroft. 2013. “Effects of Short-Term Interventions to Reduce Mental Health–Related Stigma in University or College Students.” Journal of Nervous & Mental Disease 201 (6): 490–503. https://doi.org/10.1097/NMD.0b013e31829480df.

- Yen, C. F., Chen, C. C., Lee, Y., Tang, T. C., Ko, C. H., and Yen, J. Y. 2009. “Association between Quality of Life and Self-stigma, Insight, and Adverse Effects of Medication in Patients with Depressive Disorders.” Depression and Anxiety 26 (11): 1033–1039. https://doi.org/10.1002/da.20413.

- Young, A. H., and H. Grunze. 2013. “Physical Health of Patients with Bipolar Disorder.” Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica 127 (s442): 3–10. https://doi.org/10.1111/acps.12117.

- Yuen, A. S. Y., and W. W. S. Mak. 2021. “The Effects of Immersive Virtual Reality in Reducing Public Stigma of Mental Illness in the University Population of Hong Kong: Randomized Controlled Trial.” Journal of Medical Internet Research 23 (7): e23683. https://doi.org/10.2196/23683.

- Zare-Bidaki, M., A. Ehteshampour, M. Reisaliakbarighomi, R. Mazinani, M. R. Khodaie Ardakani, A. Mirabzadeh, R. Alikhani, et al. 2022. “Evaluating the Effects of Experiencing Virtual Reality Simulation of Psychosis on Mental Illness Stigma, Empathy, and Knowledge in Medical Students.” Frontiers in Psychiatry 13. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2022.880331.