ABSTRACT

Transparency in teamwork and across team members' status is one of the main challenges in remote work, and using online collaborative whiteboards (OCW) is a potential solution for more transparent teamwork. We explore the experience of transparency of three design teams who used an OCW called Miro in remote work during the COVID-19 pandemic. Our aim was to gain in-depth understanding on what constitutes transparency in this teamwork context. We conducted a qualitative interview study with 11 participants who are user experience and service designers, and who actively use Miro in their daily work. We adopted sociomateriality as our research lens and thematically analysed the data, finding that transparency at work is a dynamic experience ranging between positive and negative. Rather than being merely users' or organisations' choices or the result of the tool affordances, the experience of transparency at work is an outcome of sociomaterial entanglements between the user, tool, and organisation. Furthermore, the occupational and organisational factors not only affect the experience of transparency, but they also actively constitute it.

1. Introduction

In the past few years, the COVID-19 pandemic has caused a significant and rapid increase in remote work. The sudden move to remote work required the implementation of new tools (digital tools, i.e. software) into employees' daily work, significantly affecting the means of collaboration, communication, and sharing, which affect the experience of transparency in teamwork.

While transparency has been mentioned as a central construct of work (Andriessen and Vartiainen Citation2006; Cekuls Citation2020; Edelmann, Schossboeck, and Albrecht Citation2021), it has also been identified as one of the main challenges in remote work (Cascio Citation2000; Ferreira et al. Citation2021). Digital tools have been identified as a potential source to alleviate remote teamwork challenges (Muthucumaru Citation2021). During the COVID-19 pandemic, people working remotely easily lost collective understanding and awareness of the work status in their team or project (Faraco, Cordeiro, and Duarte Citation2021). While the early reports of the sudden move to remote work found an increased need for team interaction and transparency through digital meetings, more subtle means for interacting with the team were needed in the long run (Andriessen and Vartiainen Citation2006; Whillans, Perlow, and Turek Citation2021). The increased portion of remote teamwork and the reported importance of transparency makes teamwork transparency an increasingly important research topic.

However, despite the increasing research attention towards transparency, its conceptualisation in work settings has remained unclear. Some studies depict it as a visibility of information or processes (Albu and Flyverbom Citation2019; Bernstein Citation2017; Flyverbom Citation2016; Gierlich-Joas, Teebken, and Hess Citation2022; Schnackenberg and Tomlinson Citation2016). Within this line of thought, it has been associated with mutual learning, efficiency, trust (Gierlich-Joas, Teebken, and Hess Citation2022), effective communication, employee engagement (Choudhury et al. Citation2020; Erickson Citation2021), employee well-being (Nadkarni et al. Citation2021), and an accurate awareness of others leading to improved employee performance (Bernstein Citation2017).

On the other hand, transparency is associated with negative aspects in work contexts. Related previous studies acknowledge its utility as a means of unidirectional control over employees, leading to increased concerns over privacy (Teebken and Hess Citation2021) as well as decreased well-being (Alder Citation2001).

The variety of definitions and the broad range of perspectives indicate that transparency is a messy and vague concept hindering it from being successfully analysed (Albu and Flyverbom Citation2019). Moreover, transparency conceptualisations have been criticised because of their simplistic perspectives (Roberts Citation2009) as they either portray transparency as good or bad, thus overlooking its complex sociomaterial nature (Albu and Flyverbom Citation2019).

Based on our literature review, transparency as a remote teamwork experience stemming from collaboration tool usage appears to be a neglected area of research. To address the challenges in the conceptualisation of transparency and to build its connections to UX, this study adopts the lens of sociomateriality. It has the potential to bring a more holistic approach that, in return, could offer ways of understanding the complex nature of transparency at work.

In this study, we focused on the practices of design teams working in software development companies and an online collaborative whiteboard (OCW) platform, Miro (www.miro.com). During our pilot interviews with designers from different countries and organisations, Miro was mentioned as one of the prominent tools they used for collaboration and sharing during the COVID-19 pandemic lockdown. OCWs, such as Miro, are good examples of tools designed for remote work practices. As Bjørn and Østerlund (Citation2014) state, the sociomateriality lens is suitable for examining work digitalisation. In our study, work digitalisation was about the replacement of paper and pen-based artifacts, such as sticky notes and physical whiteboards in designers' work, with a digital artifact, Miro. While Bjørn and Østerlund (Citation2014) focus on the design phase of such technologies, our study investigates the dynamics of intra-actions between users, an OCW, and the work settings when adopting such a tool.

In this paper, we seek answers to the following research questions:

RQ1: How is transparency experienced by designers using an OCW in remote work?

RQ2: What constitutes a transparency experience with an OCW in remote work?

RQ3: How are occupational and organisational factors involved in forming a transparency experience at work?

This paper starts with an introduction to the related research on UX at work, indicating the research gaps, and continues with a review of existing transparency conceptualisations and research in remote work settings following the description of sociomateriality and its relevance to UX research. We then present our research methods, including the descriptions of the data-gathering and data-analysing methods. Next, we present our findings on the designers' experience of transparency through the entanglement of an OCW, the user, and the work settings. Then, we discuss our findings through the existing research on the topic. Finally, we present our conclusions and suggestions for future research on user experience at work.

2. Related literature

This study explores transparency as a remote teamwork experience using a sociomaterial lens. To contextualise transparency, we first present the current state of UX research at work. Then, we explore the conceptualisations of transparency and the various approaches found in remote work studies. Finally, we present sociomateriality and its relevance to UX and remote work.

2.1. UX at work research

UX research has heavily focused on leisure domains consequently neglecting work domains (Bargas-Avila and Hornbæk Citation2011; Harbich and Hassenzahl Citation2016; Lu and Roto Citation2015; Roto et al. Citation2018; Tuch, van Schaik, and Hornbæk Citation2016; Zeiner et al. Citation2016). In response to this, researchers have begun to emphasise the need to develop the work-specific knowledge base of UX due to its clear differences to UX in leisure (Clemmensen, Hertzum, and Abdelnour-Nocera Citation2020; Tuch, van Schaik, and Hornbæk Citation2016). First, while user experiences in leisure contexts are mainly about positive experiences, the complex nature of UX at work contradicts the prevalence of positive experiences (Clemmensen, Hertzum, and Abdelnour-Nocera Citation2020; Meneweger et al. Citation2018).

Secondly, work and leisure experiences differ in terms of activities, location, social environment, and technology used (Tuch, van Schaik, and Hornbæk Citation2016). While the social environment of a leisure context may involve partners or friends, the work context may involve colleagues or acquaintances (Tuch, van Schaik, and Hornbæk Citation2016).

Thirdly, Clemmensen, Hertzum, and Abdelnour-Nocera (Citation2020) argue that UX research focuses on standalone leisure products. This is in contrast to work tools, which are used in the presence of complex work settings. Therefore, UX at work is largely influenced by the work context and structure (Clemmensen, Hertzum, and Abdelnour-Nocera Citation2020). This requires understanding the complex nature of digital tool usage at work and a more comprehensive approach. Thus, the division of labor, skill sets of employees, assignment of tasks, managerial hierarchy, organisational culture, and communication patterns within the organisation should all be the main focal points of the studies (Clemmensen, Hertzum, and Abdelnour-Nocera Citation2020).

Current UX models are based on the narratives and experiences gathered from leisure domains (Bargas-Avila and Hornbæk Citation2011; Tuch, van Schaik, and Hornbæk Citation2016). The differences mentioned above clearly indicate that current UX models are biased towards leisure domains and might not be reliable for understanding UX at work (Bargas-Avila and Hornbæk Citation2011; Tuch, van Schaik, and Hornbæk Citation2016). Therefore, UX research needs to develop the UX at the work-specific knowledge base (Simsek Caglar, Roto, and Vainio Citation2022).

Amongst the research focusing specifically on UX at work, there's more concentration on improving work performance by emphasising efficiency, effectiveness, and productivity; overlooking the emotional and experiential aspects in the workplace (Simsek Caglar, Roto, and Vainio Citation2022). Moreover, despite the mention of some experiential aspects in some studies, the meanings and mechanisms are rarely discussed (Bargas-Avila and Hornbæk Citation2011; Simsek Caglar, Roto, and Vainio Citation2022). Understanding of this complex topic can never be complete without paying attention to the meanings and mechanisms generating experiences at work.

On the other hand, UX at work has been criticised for the arbitrary inclusion of contextual factors into UX at work research (Bargas-Avila and Hornbæk Citation2011; Clemmensen, Hertzum, and Abdelnour-Nocera Citation2020; Simsek Caglar, Roto, and Vainio Citation2022). Although context has been widely accepted as an essential factor affecting experiences (ISO 9241-210:2019 Citation2019), in most cases, the inclusion of context does not move beyond being superficial observations (Clemmensen, Hertzum, and Abdelnour-Nocera Citation2020; Simsek Caglar, Roto, and Vainio Citation2022).

2.2. Transparency conceptualisations

Transparency has attracted the attention of scholars from various domains, including management, public relations, policy, finance, anthropology, sociology, law, political science, cultural studies, and information systems (Albu and Flyverbom Citation2019; Schnackenberg and Tomlinson Citation2016).

It has often been claimed that transparency acts as an umbrella term with various conceptualisations (Albu and Flyverbom Citation2019; Bernstein Citation2017; Schnackenberg and Tomlinson Citation2016). This lack of both a rigorous theoretical development of transparency as well as of a unified definition has been raised by scholars (Schnackenberg and Tomlinson Citation2016). Albu and Flyverbom (Citation2019) argue that this concept is rarely critically examined, with the available conceptualisations indicating that it is a messy concept. (Hood Citation2006, 3) states that ‘transparency is more often preached than practiced, more often invoked than defined, and indeed might ironically be said to be mystic in essence, at least to some extent.’

Nonetheless, in most accounts, transparency is defined as a matter of timely disclosure of information to increase accountability, openness, and trust (Albu and Flyverbom Citation2019; Bernstein Citation2017; Flyverbom Citation2016; Gierlich-Joas, Teebken, and Hess Citation2022; Schnackenberg and Tomlinson Citation2016). This conceptualisation has been argued as being a simplistic definition with a narrow focus (Albu and Flyverbom Citation2019; Flyverbom Citation2016; Pachidi, Huysman, and Berends Citation2016; Schnackenberg and Tomlinson Citation2016). Flyverbom (Citation2016) argue that transparency requires more nuanced conceptions. They also criticise the implied positive effects of disclosing information. Transparency does not only misconduct and cure problems, but it has ambiguous and paradoxical effects rather than simply reducing misconduct and cure problems in organisations (Flyverbom Citation2016).

Albu and Flyverbom (Citation2019) categorised the existing transparency conceptualisations in two strains of research: verifiability and performativity. Verifiability approaches conceptualise transparency as disclosure of information (Bushman, Piotroski, and Smith Citation2004; Eijffinger and Geraats Citation2006; Wehmeier and Raaz Citation2012). It perceives the sharing of information as a linear, two-way, mechanical process and aims at improving the quality and quantity of information disclosure. Visibility, clarity, trust, effectiveness are seen as positive implications that are developed through transparency (Arellano-Gault and Lepore Citation2011; das Neves and Vaccaro Citation2013; Gray and Kang Citation2014).

In contrast, performativity approaches regard transparency as processes involving negotiations, interpretation, and complications (Albu and Flyverbom Citation2019). The studies based on sociomateriality argue transparency to be co-constituted by subjects, objects, and settings (Albu and Flyverbom Citation2019; Flyverbom Citation2016; Pachidi, Huysman, and Berends Citation2016). They are entangled in practice, and these entanglements can alter that which is transparent (Albu and Flyverbom Citation2019). Pachidi, Huysman, and Berends (Citation2016) emphasise the performativity of transparency to understand the mechanisms in which actors are being deliberate in being more transparent or opaque as they use digital tools which disclose their actions to the organisation. In other words, they discuss that the way that a technology is supposed to increase transparency in the workplace can also enable opaqueness through the entanglement of humans and technology in various settings. Therefore, transparency is not merely a guideline in the organisation but a sociomaterial construction through the enactment of the technology (Flyverbom Citation2016; Pachidi, Huysman, and Berends Citation2016). It involves interpretation and sense-making (Christensen and Cheney Citation2015; Flyverbom Citation2016). Flyverbom (Citation2016) highlights complex sociomaterial mediation processes that constitute transparency. He states that sociomaterial approaches are useful starting points as they encourage researchers to explore the limitations and opportunities of these mediating technologies and draw attention to the production and importance of transparency in different contexts (Hansen and Flyverbom Citation2015).

Performativity approaches challenge the understanding of transparency as being only visible information and emphasise the management of visibilities (Albu and Flyverbom Citation2019; Flyverbom Citation2016). Therefore, transparency results in unexpected complications in addition to clarity, trust, and effectiveness (Albu and Flyverbom Citation2019).

While stating the importance and necessity of both strains, Albu and Flyverbom (Citation2019) highlighted that verifiability (information disclosure) constitutes the majority of the research in transparency. They stress the necessity of more research attention on performativity in order to enhance the transparency conceptualisation; particularly focusing on the dynamics of transparency, surprising complications, ambiguous effects, and unexpected results rather than treating transparency merely as openness, insight, and clarity (Albu and Flyverbom Citation2019; Flyverbom Citation2016; Pachidi, Huysman, and Berends Citation2016).

Based on this suggested necessity, our research follows the performativity approach by taking transparency as a process. This allows us to uncover meanings and mechanisms of transparency as a work experience which has been discussed as a gap in UX at work literature (see Section 2.1).

2.3. Transparency in remote work

The concept of transparency has gained increased attention after the COVID-19 lockdown (Nadkarni et al. Citation2021) . It has been argued that transparency in remote work is the central construct with which to facilitate organisational learning, maintain trust, increase engagement, and well-being, as well as avoid speculations and information omission (Cekuls Citation2020; Choudhury et al. Citation2020; Edelmann, Schossboeck, and Albrecht Citation2021; Erickson Citation2021; Gierlich-Joas, Teebken, and Hess Citation2022; Nadkarni et al. Citation2021; Sull, Sull, and Bersin Citation2020). These studies discuss transparency in terms of clear communication of tasks and concerns from managers to employees in remote work (Cekuls Citation2020; Edelmann, Schossboeck, and Albrecht Citation2021), maintaining company-level transparency to maintain stability during remote work (Choudhury et al. Citation2020; Erickson Citation2021; Nadkarni et al. Citation2021; Sull, Sull, and Bersin Citation2020), and optimising employee trust within the available surveillance capabilities in work tools (Gierlich-Joas, Teebken, and Hess Citation2022).

These studies identify transparency as unidirectional communication from managers to employees. Due to this understanding, they prescribe plans and methods to improve this communication for better work engagement. While these studies cover extensively how transparency can be optimised to enable and improve remote work, they all situate transparency on a hierarchical level.

Although the discussions on transparency have been mostly situated in the context of management employee communication. We have found few studies addressing peer-level transparency. Amongst the studies we found about peer-level transparency in work settings, they either explore non-remote and in-person settings (Bag and Pepito Citation2012; Mohnen, Pokorny, and Sliwka Citation2008; Palanski, Kahai, and Yammarino Citation2011), or focus on the technological capabilities of software involved in early remote work environments (Navarro, Prinzt, and Rodden Citation1993; Reinhard et al. Citation1994; Thimbleby and Pullinger Citation1999).

All these studies show us that transparency has been addressed from a verifiability perspective since they talk about it either as a construct that should be enabled by managers or as a capability of the software but not as a process. Transparency from a performativity perspective has not seemed to enter the transparency discussion yet. Moreover, the studies are focusing more on managerial perspectives rather than peer-level transparency. One exception is the work carried out by Stuart et al. (Citation2012) which focuses on peer-level transparency using prior theories. Although their work is relevant due to how they oversee transparency from a broader perspective, it lacks empirical inquiries. Our study aims to address these issues and focus on peer-level transparency in remote work settings by adopting a performativity perspective.

2.4. Sociomateriality and its relevance

This section introduces the concept of sociomateriality and discusses its relevance to HCI, UX, and remote work.

Orlikowski and Scott (Citation2008), based on the works of Suchman (Citation2007) and Mol (Citation2002), use sociomateriality as an umbrella term to refer to relational, practice-based, and post-humanist approaches to understand materiality (Orlikowski Citation2016; Orlikowski and Scott Citation2008). Sociomateriality argues that ‘there is no social that is not also material, and no material that is not also social’ (Orlikowski Citation2007, 1437). This emphasises that social and material are not independent entities with separate and pre-given characteristics (Barad Citation2003), but that they are constitutively entangled in practice (Latour Citation2004; Orlikowski and Scott Citation2008; Pickering Citation1993). As Barad stresses, ‘To be entangled is not simply to be intertwined with another, as in the joining of separate entities, but to lack an independent, self-contained existence’ (Barad Citation2007, 9). The entanglement perspective challenges the anthropocentric view of agency (Frauenberger Citation2019). It argues that agency is not a capacity intrinsic to humans (Latour Citation1992, Citation2005; Suchman Citation2007) but it emerges through the intra-action of human and non-human (Barad Citation2007). Therefore, the agency depends on the ‘effect of practices that are multiply distributed and contingently enacted’ (Suchman Citation2007, 267). One of the central ideas in sociomateriality is performativity (Barad Citation2003; Orlikowski and Scott Citation2008). Barad argues that performativity refers to the ‘ongoing reconfigurings of the world’ (Barad Citation2003, 818). It emphasises the notion of enactment in practice. This indicates that the focus is not on discrete entities but on ‘matters of practices/doings/actions’ (Barad Citation2003, 802). The significance of performativity for sociomateriality is that the relations and boundaries between social and material, that is, humans and technologies, are not inherent or stable but enacted in practice (Orlikowski and Scott Citation2008).

Quite recently, HCI research has acknowledged both the potential of sociomaterial approaches and their applicability to investigating human-technology relations. Understanding and conceptualising human-technology relations is particularly important for understanding the experiences stemming from them. Some of the key concepts that are the foundation of UX have been challenged by the perspective of sociomateriality with scholars questioning concepts, such as interaction, interface, use, and functionality. Bødker (Citation1990) indicated the transition of the interface from a stable object to a medium through which the user operates. Other research has problematised the concept of interaction as a simplifying and outdated understanding of the relations between humans and technology (Frauenberger Citation2019; Taylor Citation2015; Verbeek Citation2015) with interaction implying an inherent separateness between humans and technology, thus reducing their relationship to discrete interactions (Taylor Citation2015). Barad (Citation2007) argues that users and tools do not function in their separate spheres and suggests that the concept of ‘intra-action’ should replace ‘interaction’. Moreover, Verbeek (Citation2015) claims that the ‘use’ of a tool is a misleading concept and suggests a transition to ‘immersion’ and ‘fusion’.

On the other hand, functionality has been asserted as reducing the role of tools to instrumentality. In many cases, functions are not predetermined but emerge from the relationship between humans and technology (Verbeek Citation2015). A common agreement among these scholars is that HCI needs to shift from viewing humans and technology as separate entities with inherent boundaries to viewing them as hybrid beings (Introna Citation2009). This notion requires the decentring of humans (Frauenberger Citation2019), the acknowledgment of the material agency (Orlikowski Citation2016; Orlikowski and Scott Citation2008), and the attention to the practices that enact certain phenomena (Barad Citation2003). They all call for an entanglement perspective that transforms not only the design practice and research paradigm but also our understanding of experiences resulting from the relationship between humans and their tools.

Finally, sociomaterial approaches have been utilised when exploring human-technology relationships in the remote work context, during which communication and collaboration are even more reliant on digital tool usage. Jarrahi and Nelson (Citation2018) investigated the varying entanglement of tools and practices used by mobile workers who have to work on the go. They argue that while new information technologies enable mobile work practices not possible before, they impose specific configurations based on technological (software and hardware), spatial, organisational, temporal, and financial constraints. They found out that mobile workers actively shape multiple technological resources to construct their own personal IT assemblages for their practice.

Similarly, Johri (Citation2011) use a sociomaterial approach to understand how one company's globally distributed remote office workers can configure various digital tools and social practices together as 'brilocalages'. By extending the prescribed utilities of their digital tools, remote workers could enhance their work-life balance and informal communications channels through the time-zone differences within their workforce. They describe this process as a real-time design using the various existing digital tools and facilities at hand.

Petani and Mengis (Citation2021) look at how remote workers, their digital tools and physical spaces are configured together from a human resources management perspective. Through a similar sociomaterial lens as the previous studies, authors explore how companies could embrace and utilise emergent configurations of tools and workers to improve employee wellbeing.

These studies show how technologies are entangled with remote worker's individual daily practices and thus the user experiences are continuously reshaped. While these examples encompass a range of digital tools and their entanglement within remote work, our study adopts a narrower approach by honing in on a specific digital tool. By narrowing the scope to one digital tool, we aim to provide a more detailed understanding of the user experiences associated with its usage through a sociomaterial lens.

3. Methodology

Similar to the two studies in (Bjørn and Østerlund Citation2014), we conducted a qualitative study by gathering data with semi-structured interviews (Adams Citation2015). Thematic analysis method (Braun and Clarke Citation2006) was used to analyse the interview data. Our goal was to understand the entanglement of designers, Miro, and work settings, as well as the involvement of these entanglements in the formation of work experiences. Therefore, we scrutinised the relationship between designers, Miro, and the work settings through the sociomateriality lens.

The next sections will present the procedure, research context, and data analysis.

3.1. Procedure

Before the actual study, one researcher conducted pilot interviews to explore the tools used by designers of digital services for remote collaboration after the sudden move to remote working conditions caused by the COVID-19 pandemic. The pilot study was conducted with six designers working in different organisations throughout Europe between December 2020 and January 2021. Participants were recruited through a call we posted on relevant groups on LinkedIn (e.g. User Experience Design) and Facebook (e.g. Give Good UX Company of Friends). We asked questions about their daily work life and the tools they used to achieve work tasks. All six participants pointed out that they used Miro on a daily basis as a prominent tool for remote collaboration. We decided to focus on Miro for the study as Miro was defined as a multipurpose tool that allows synchronous and asynchronous sharing and communication among colleagues and other stakeholders, while simultaneously offering a wide range of affordances that generates a basis for various experiences.

After the pilot study, one researcher conducted 11 interviews with design professionals from three different organisations in three different countries: the United Kingdom, Germany, and Finland. The participant information is presented in . Participants were chosen according to availability sampling and the snowball method. We posted a call on popular UX design groups on LinkedIn and Facebook asking potential participants to reach out to us through comments or messages. Those who reached out were asked to find at least two more volunteer designers from their own organisation. The purpose was to recruit at least three participants from the same organisation to better grasp their organisational factors. The criteria we set for the participants was that they were designers who actively used Miro on a daily basis. Three participants found at least two more participants meeting the criteria from their organisations. In this way, we recruited four participants from two companies and three participants from one company.

Table 1. Organisations and participants.

The interviews were conducted online through Zoom between February and May of 2021. They ranged from 80 to 100 minutes and were conducted by the first author. Each interview was recorded and then transcribed. All the participants were provided with informed consent forms via email to study about a week before the interview. The consent form was discussed in each meeting, and all participants conceded their verbal consent which was recorded.

The semi-structured interview questions consisted of three main themes. The first theme focused on understanding the work such as daily work practices, the role and the responsibilities of the designers, the team structures, design processes, as well as the occupational culture. The second theme targeted addressing the organisational culture and practices. Finally, the third theme targeted the use cases of Miro, the ways in which it is integrated into daily work practices, the manner in which the topics discussed in the previous questions related to the usage of Miro, and their associated experiences. The first two themes allowed us to answer the RQ3, while the third theme helped us understand that the transparency experience was the dominant experience and contributed to our answering the RQ1 and RQ2.

3.2. Research context

This section presents the main Miro affordances, designers' work practices, and participating organisations' contextual information.

3.2.1. Miro affordances

Miro is an online collaborative whiteboard that provides an infinite canvas on which to build. In addition to text, shapes, and lines, Miro offers virtual sticky notes and ways to easily connect these objects using arrows. Templates provide a starting point for activities, such as journey maps, strategic planning, and brainstorming. It is built using web technologies and can be run in a browser, rendering it easier to invite and share boards with people even when they do not already have it installed. Multiple people can simultaneously work on the same board with their cursors being visible to each other during use.

3.2.2. Designers' work practices

All three organisations from which we recruited designers adopted agile design practices. The designers' typical work included quick and iterative cycles of collecting and analysing research data, brainstorming, sketching, conducting user workshops, building user journeys, developing concepts, and prototyping. Design work, especially in agile teams, requires high levels of transparency since they are expected to collaborate and constantly share in multidisciplinary teams. All the team members are expected to be aware of the design phases at any time and be responsive to resolving any complications that might emerge during the process. Designers deal with large amounts of complex information which they need to interpret in highly multidisciplinary teams. Therefore, communication and collaboration between and across the teams, as well as with other stakeholders, such as users or customers, is essential. Designers need to stay on track and keep pace with fast cycles of feedback and project timelines.

Before the pandemic, design teams would physically gather in front of a physical whiteboard with sticky notes and pens for collaborative tasks, such as brainstorming, organising research data, giving and receiving feedback, building user journeys, and conducting user workshops. After the pandemic-mandated remote work, designers needed to digitise all these tasks. Miro was one of the available tools enabling this process.

3.2.3. Organisational context

The first organisation, C1, is a public one, a county council's service design department. They adopt a user-centred design approach to design services for the residents. The organisation has been reported to have a political environment in which communication requires careful consideration. The presence of politicians working in the county council and the requirement to collaborate with them influences the communication and sharing practices. The designers mentioned the tension that derives from working with politicians. While politicians want to work in more traditional ways, designers define their work as contravening the traditional ways and politics, and instead moving towards more innovative ways. Since the organisation adopts a participatory design approach, they frequently conduct co-creation workshops with the residents. The designers of C1 report great awareness is required when communicating and sharing with the residents, due to the sensitive topics entailed by services, such as adoption.

The second organisation, C2, is a global company that manufactures construction materials. The design department works on digital tools both for its customers and for internal users. The designers describe the organisation as big, old, hierarchical, and traditional but, at the same time, as being open to change. The design department was reported to possess a strong user-centred culture. The organisation has a guiding principle of transparency with its customers entailing a regular and frequent sharing of information with them. On the other hand, the organisation was transitioning through a digital transformation at the time of the interviews. They were introducing new tools for internal usage to increase the digitalisation of their processes. The COVID-19 remote working conditions have been mentioned as accelerating the digitalisation process. The internal users were defined as ‘technology illiterate,’ which set a challenge for the digitalisation process.

The third organisation, C3, is a design consultancy that provides clients with service and UX design. The company was reported to have a flat hierarchy and low bureaucracy. Their internal culture emphasises open communication. Designers in this company also define themselves as salespeople. Although they work in teams to some extent, they mostly function as individual design professionals who sell their services to their clients.

3.3. Data analysis

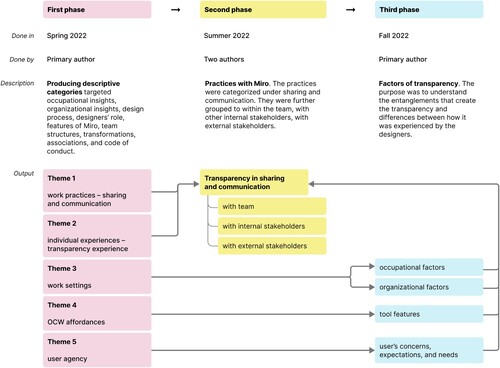

The interview data were analysed using thematic analysis (Braun and Clarke Citation2006). A plan of three phases was followed as shown in . For the first phase, the first author familiarised themselves with the data as they worked on the transcriptions of the interviews, generating the initial descriptive codes, such as occupational factors, organisational factors, design process, designers' role, the OCW affordances, team structures, transformations, associations, code of conduct, and user agency.

Five themes emerged from these codes: work practices, individual experiences, work settings, OCW affordances, and user agency. The first theme addresses designers' practices with the OCW regardless of the organisations they work for, such as co-creation, workshops, meetings, and presentations. They were categorised under sharing and communication. As participants mentioned various types of sharing and communication practices, their accounts fell into three distinct categories according to their operating circles: within the team, with other internal stakeholders, and with external stakeholders. In each operating circle, transparency experiences showed considerable differences. Therefore, we coded the sharing and communication practices according to their operating circles.

The second theme targets individual experiences during sharing and communication practices. We derived experiences, such as trust, freedom, confusion, transparency, and stimulation, from the participants' accounts regardless of the company for which they were working. Among these, transparency was the only common experience in all accounts. Therefore, we eliminated the other experiences and focused on transparency.

The third theme, work settings, focuses on occupational and organisational factors. Participant accounts from each organisation were separately analysed. The design process, designer roles, and team structures were coded under occupational factors. Organisational processes, phases, communication, and sharing patterns were coded as organisational factors.

The fourth theme was identified as OCW affordances. All the tool features mentioned by the participants were coded under this theme.

Finally, the fifth theme targeted user agency. User's concerns, expectations, and needs were coded under this theme.

During the second phase, two authors worked on revealing the practices of interviewees with Miro. Data from the first two themes were grouped under sharing and communication practices, and then these practices were further grouped by their operating circles: within the team, with internal stakeholders, and with external stakeholders. These practices of sharing and communication were identified as the source of transparency experience with Miro.

In the third and final phase, the first author revealed the factors mentioned in conjunction with sharing and communication practices using the data from themes three, four, and five. Authors then analysed how these factors played a role in the formation of the transparency experience identified in phase two. Based on this analysis we have identified six different transparency experiences: transparency as visible mess, transparency as visual mind, transparency as engagement, transparency as ownership, transparency as surveillance, and transparency as vulnerability.

4. Results

Our data shows that regardless of which organisation our participants were from, they experienced increased transparency in terms of thought and work processes after the introduction of Miro into their daily work. The experience of transparency is discussed regarding the ways they communicate, collaborate, and co-create; through one's immediate work team; and with other internal or external stakeholders. A schema summarising the results can be seen in .

4.1. Transparency as a visible mess

There is a strong collaboration and sharing culture within teams in all three organisations. The participants mention co-creating in the same space as common practice as part of the agile design process. One participant explains this co-creation in Miro as follows:

So we start in a Miro board, looking at the same thing, you know, and then, I make a square and I start thinking about something and then someone comes in and builds on top of my square sort of. So, um, so, we are kind of thinking in the same space. So, what I mean with collaboration is we're not kind of dividing tasks and coming back together. (C3-1)

Using shared documents in Miro differs from first working in a personal workspace, such as a personal notebook or an unshared digital document, and then, reorganising it to show to someone else and to receive feedback. It is used as a co-thinking space that renders the individual work more transparent and open to being revised or built on by another colleague at any time.

However, in addition to this active, synchronous mode of collaboration, participants also mentioned visibility into each other's work as being a more passive and asynchronous mode of sharing. Transparency has been associated with always visible work processes to exchange feedback, and visible work progression to have a general overview. This type of transparency creates constant visibility of ‘raw work’, i.e. work in process. (C1-2) describes the sharing practices with their teammates through Miro as follows:

Within our team, we want to be transparent about what we do. So if we don't share what we're doing, then it might be a little bit awkward. And so, for example, although if someone is not comfortable getting feedback early or, you know, sharing the progress before actually completing the work, it would be better to share early and get feedback early. (C1-2)

The team's expectations are compatible with Miro's sharing and editing affordances by which anyone in the team can access the team boards and provide feedback synchronously or asynchronously using the Comments feature or Sticky notes. Even though the designers might not feel comfortable sharing their work at an early stage, they comply with the team expectations. Transparency in this context is mutually constituted by Miro's visibility affordances, expectations of the team, and team members' compliance. (C1-2) explains the expected practice of transparency in their occupational culture as follows:

We share quite often and quite regularly, even though it's like a scribble of ideas because that really helps us to get other people's fresh eyes on something. So we kind of share quite regularly within our profession. And also we work quite closely because it helps us to kind of learn from their point of view and identify worrisome things that we've missed. (C1-2)

All the interviewees reported following the same kind of practice regardless of which ones were their companies. Sharing regularly, even the scribbling of ideas, has been a work culture for designers who adopt agile work processes. The culture of ‘often and regular sharing’ in agile design processes is entangled with Miro's sharing and visibility affordances. After the adoption of Miro, the expectation of sharing has been realised as an unwritten rule resulting in the Miro boards created by individual team members being shared by default with the rest of the team. All the team members have access to the shared boards at any time. As (C1-1) stresses, ‘Anyone can hop in and have a look at what's happening at any time’. This creates a shared awareness of the work progress and an opportunity for contribution and feedback. Thus, synchronous or asynchronous sharing and constant visibility into each other's work constitute an experience of transparency. The participants report that Miro adopted in this way encourages them to ‘work openly’ (C2-4).

Not merely the affordances of Miro but the way these affordances are adopted and applied by the design practitioners are strong determinants of the transformation of work practices into becoming more transparent. For example, the accounts show that designers no longer carry out extensive preparations or cleanups before sharing what they are working on, as there is no longer a state before sharing. Therefore, visibility into raw and messy work is becoming common in their work culture. The following two accounts represent the spontaneity of the sharing practices among team members.

You can keep it raw. And it's fine. I present to my colleague and just, I want to express what I need to in the simplest and the quickest way. (C2-1)

To have a conversation with like colleagues and stuff. Like why bother? Like you just treat them whatever mess you've created, you know, somehow you want to make sense out of. (C1-3)

The accounts above exemplify the transformation of an occupational process through the relationship with the tool. As explained by the following account, what was first a reaction to a new affordance ended up as a change of culture through the entanglement of the designers, their work culture and processes, and a newly introduced work tool.

Usually didn't happen [before Miro]. As I said, you would see your colleagues' design files. If someone shared a file, they would have to kind of like clean it up first, so you don't see my mess. But now we kind of used to each other's mess, like, this is my thought process. What's your thought process? Let's do something together. So in a way, that has changed the culture of sharing a little bit. (C3-2)

The compulsion to ‘clean up’ before sharing work with a colleague disappears. Designers share more unfiltered and spontaneous processes through Miro. They are becoming more comfortable with sharing messy individual work. Another account exemplifies the way in which this change is not merely reactionary but deeply rooted.

I want to structure information to understand what I need to understand. And, that is the phase where I typically want to work first myself, to build the picture. But typically that is the part, that has changed in my work. I don't have it anymore. That's sort of secure and private brainstorming. I can call them chaos storming. So, I have become more open to my internal chaos. It has changed because of working with this kind of tool. So I'm not any more afraid of sharing all that chaos because it just lowered the bar that I don't care anymore. (C3-4)

In this case, their role as a designer shifted from individual sense-making to laying out the information for a collective one. The 'bar', as they call it, the line they draw for their occupational authority, is 'lowered' as a result of transparency constituted by the entanglement between the team practices, the tool, and the user.

4.2. Transparency as visual mind

In addition to the transparency in the sharing of one's work and workspace at an early phase, another form of transparency is seen in the sharing of individual thought processes. Participants report that they simultaneously start working on a Miro board whenever they start an online meeting. They use a video conference tool depending on the organisation's license (Google or Microsoft). While participants are on the video call, they simultaneously gather on the Miro board. The person talking at the time shares the screen to focus the attention on the right part of the board. They share their notes on the topic, visualise ideas and information, collaboratively take notes, and make connections between pieces. They utilise various visualising tools, such as mind maps, tables, wireframes, connector arrows, sticky notes, or various user-generated templates. Visualising what they are talking about on a Miro board clarifies the conversations as mentioned by (C1-3) ‘…and there's no miscommunication because as I say the thing, you've put it down’. Similarly, (C3-2) comments on the same issue as follows:

As we are talking, we are doing notes on Miro so everybody can see what we are doing. And they can say like, okay, that post it, I actually didn't mean that post it to go there. Making connections visually in the Miro board …Just to have a conversation …It makes it more clear. It's [ visualising/note-taking on Miro] at the same time as we're talking and they can see the notes that we're doing. I think it helps to kind of understand the way we think and what we are getting out of the conversation. (C3-2)

The meetings, which were only earlier verbally held, have become more concrete with everyone visualising their thoughts on a board. The users' needs for better communication are entangled with the visualisation affordances in such a way that they increase the clarity in communication by increasing the visibility into each other's thought processes. Being able to ‘draw out ideas (C2-4)’ on Miro has been mentioned as being an ‘easy way to communicate thoughts (C2-4)’. This helps them ‘get aligned (C3-1)’ and ‘speak over the same thing (C1-2)’. (C3-2) explains their use of Miro as a means to increase the transparency in thought processes as follows:

You have your mental picture of how things relate inside your brain and you try to visualise somehow. I use miro a lot for that. This is how I see it. Would you like to show me your mental picture? Like how you see it? See, if we are we on the same page. (C3-2)

Communicating one's thoughts has been an important issue in the design process. The occupational culture of designers is based on sharing and communicating their ideas. Visualisation affordances of Miro have been a means for projecting individual thoughts onto a canvas to be grasped by another individual. Miro's synchronous, collective visualisation affordances have been adopted to add another layer on top of verbal communication during remote meetings. Miro is entangled with the design process in this particular way and concretises the thoughts by rendering them visible.

Miro has also been used to create a clear understanding among colleagues coming from different occupational backgrounds. The designers often emphasise the necessity of collaboration and co-creation, which requires strong communication with their colleagues from different job roles (see Section 3.2.2). Colleagues from different backgrounds have different ways of thinking and working, which can hinder communication. As a common example, participants talk about the challenge in the communication between designers and developers. The digital tools that they use in their daily practice have been expert tools, such as tools specialised either for designing or developing. The work with these tools, with their required expertise and high learning curve, has been isolated. There has been no access to the actual workspace of a developer by a designer or vice versa. This has deepened the communication gap between colleagues from different occupational backgrounds. (C3-2) explains this situation as follows:

The easiness of different roles using the same tools…This didn't happen in history. There was always like the designers do their work here and developers, they do there. And there was always a gap, like trying to communicate through that gap of the tools. But now they are coming together in the same tool, they can use the same tool. So they have a common ground understanding of things. So there is a lot of people in a lot of different roles that think differently that can be using the same tool. So we have the same kind of understanding of the presentation of ideas. (C3-2)

The ‘easy access of different [occupational] roles (C2-4)’ to the tool, ‘simple features for visualizations (C1-3)’, ‘low learning curve (C1-2)’ and ‘being a web-based tool with no requirement of installation (C3-4)’ are mentioned by designers as the affordances of Miro that enable the different occupational roles to work together. However, it is not solely the affordances but the application of these affordances that has reconfigured the communication practices. Designers adopted Miro in such a way that it is simultaneously used during online meetings. This particular entanglement has constituted an experience of transparency into each other's thought processes. Therefore, Miro is not only a collaboration and co-creation tool, but it is also a means by which to blur the cultural boundaries between occupations.

It is important to note that the two sections above (Sections 4.1 and 4.2) both present findings that are unique in team practices. We have not found similar designers' practices while sharing and communicating with other internal or external stakeholders. The practices while sharing with other internal stakeholders or external stakeholders will be presented in the following sections. On the other hand, we have not observed significant differences in different organisations regarding experiences of transparency within the immediate team. The similarities in experiencing transparency in all three organisations and lack of notable differences show that sharing and communication practices within the immediate teams are tightly intertwined with design processes (agile), design culture (sharing and collaboration), and team dynamics (expectations, multi-disciplinarity) rather than the organisational factors.

4.3. Transparency as engagement

In this section, we will focus on the use of Miro and the transparency experienced through Miro to achieve involvement and engagement for both internal and external stakeholders.

In C2, the designers develop work tools to be used within the company (see Section 3.2.3). In this case, internal stakeholders are both the users and employees. They will be referred to as internal users. (C2-3) explains the profile of the internal users as tech illiterates. They either talk on the phone or work with Windows XP computers. When introducing a new digital tool into their daily work life, they are reluctant and ‘very suspicious (C2-3)’. (C2-3) continues explaining that before Miro was adopted in their daily work practices, physical workshops would be conducted to introduce the new digital work tool to the internal users. In these workshops, the developers would develop spec sheets that would be ready for implementation. The aim would be to inform the internal users about the change and collect feedback from them rather than conducting a collaboration session during which hands-on contribution from internal users would be expected. However, due to COVID-19 and the obligations of working from home, workshops have since been transferred to Miro. As (C2-3) reports, after the adoption of Miro, the workshops have become more inclusive. (C2-3) shares the observations about the issue as follows:

Telling them what to do versus in a workshop format like this, you're like flipping it around and saying, hey, we are like really raw. This is literally a blank canvas, as you can see. And then, together, we are trying to understand what's happening and how should we solve those problems. So I think like these people who are there participating initially, they're like very reserved, very suspicious. But then when they actually see that we are very raw, very fresh, they become more excited, more forthcoming, and more involved. So that's, I think that's how miro or tools like miro are shaping the organizational culture. (C2-3)

Rather than being only the receiver of the design outcome, the internal users become active contributors in the design process. The employees feel as if they can influence their work tool designs and, consequently, the future of their work. Therefore, the transparency of the design process has increased for the internal users who are neither designers nor part of the design team.

When Miro was adopted, the organisation was going through a transformation phase that required digitalisation of the previously manual processes. This required introducing new digital work tools, thus, a change in the practices of the employees. Therefore, the internal users' engagement in the design process has been afforded even more importance since it has affected the easy adoption of the new work tools.

In this particular use of Miro, the inevitable obligation to conduct workshops in online settings; the audience of the workshops (tech-illiterate internal users); Miro affordances, such as the simple features requiring no prior training and being able to share a blank canvas conveying the message that the design is not finished; and the organisational factors (digitalisation) have consolidated and formed a specific experience of transparency as engagement. Furthermore, while organisational factors have affected the ways that Miro is used, the specific way it is applied reciprocally played a role in changing the organisational culture into becoming more transparent, collaborative, and inclusive. Therefore, in addition to being a tool used to engage internal users, Miro has also become a strategic tool for shaping the design culture and practices by serving the digital transformation.

We have observed another strategic use of Miro for the engagement of the internal stakeholders in C2. In this case, the internal stakeholders are the upper management who are not a part of the immediate team.

What I've noticed is if you have a presentation [in presentation-specific softwares], which has a really polished, finished look, people just jump into the conclusion, incorrect conclusion that you already know everything that you need to know, and then it's time for you to go and implement it. (C2-2)

Compared to presentations in a presentation-specific software, presentations in Miro are associated with non-finished and non-polished. (C2-2) further describes the Miro boards that they work on as a ‘living document’ and a ‘knowledge dump’ which represent Miro as showcasing the process rather than the outcome. Thus, presentations in the Miro boards convey the message that the topic is still open to discussion and contribution. Designers turn this into an advantage to engage the audience to elicit feedback.

A very similar utilisation of Miro as an engagement tool is present in Organisation C3 with its internal stakeholders (see Section 3.2.3). (C3-2) explains as follows:

When you're talking to internal people, I've noticed that if you have a slide set, no one will criticise it. So kind of, they will take it as it is. But if you're trying to get people to kind of comment on something, or you're not sure of something, I wouldn't put it in a slide set, or I would just show Miro because that's like it has the lowered the bar that it's changeable. (C3-2)

This account draws attention to the perceived difference between sharing a slide-set and sharing a Miro board. This particular use of Miro communicates the message that things are not yet certain. As discussed in the earlier accounts, sharing unfinished work increases the transparency of the earlier design phases and renders them more open for discussion and revisions by colleagues. (C3-2) further elaborates on the difference by emphasising the easiness of manipulating the items on a Miro board, such as grabbing, shifting, and moving things around. She compares the presentations in Miro, in which the audience has access to the board and is able to edit, with the bullet points in presentation-specific software and says, ‘If you are looking at a presentation, you wouldn't just like to move a bullet point. (C3-2)’ Nevertheless, moving things around in Miro feels ‘free and easy (C3-2)’. Even though the audience might have equal access to the slides in presentation-specific software, the reaction would not be to move things around. In this case, the designers' intentions to elicit feedback become entangled with Miro's affordances to be strategically used to engage the internal stakeholders.

In C2, Miro has also been used to engage the external stakeholders in a similar way that it has been used for internal stakeholders. The external stakeholders are the customers of the company. (C2-3) states that ‘the guiding principle (C2-3)’ of the company for communication with the customers is ‘transparency (C2-3)’. (C2-3) continues explaining the alignment of this approach of the company with Miro as a work tool:

Whatever information that we know, we will share with our customers as soon as we know. So that is the guiding principle. And then if we actually look at a tool like Miro, it's actually very closely aligned because I can very easily share with everyone. What is the status of my work? What is it that I know and what is it that I don't know? And I can do that very easily. (C2-3)

Similarly, (C2-2) also explains that Miro's affordances enable easier sharing and collaboration with external stakeholders. It provides access for anyone without them needing to install, subscribe, or create an account. It is an online tool in which, through link sharing, anyone can have not only access but can also contribute to and apply changes to the board. The expectation of transparency as an organisational practice becomes entangled with the easy sharing affordance of Miro and generates another strategic use for the involvement and engagement of the customers in the design process. (C2-1) explains this as follows:

To engage the stakeholders into the working process of design or information collection …Instead of presenting something like we did this, let's say like a vendor selling something, we say, okay, we are working on this space. You can see the tools around, you can see the mess, but you can also able to be part of it while we are making decisions. And this is really engaging for them. It helps to share, but also engage people. Because you're not only seeing something like a presentation, you can change it while you're watching. (C2-1)

This account also emphasises the sharing of unfinished work and a messy workspace. However, in this case, in C2, the workspace is also shared with the customers, not only with the internal stakeholders. (C2-1) defines this as customers ‘feeling part of the team (C2-1)’. They compare presentations done in Miro to the workshops, which create ‘a different approach (C2-1)’, like a ‘playground (C2-1)’ in which the customers are not only the listeners but also can contribute to the outcome. Inviting customers into the ‘messy’ Miro boards cannot be separately considered from the organisational guiding principle of being transparent with the customers. Therefore, the organisational expectations of transparency, the users' intentions to engage the audience, and the Miro affordances of easy sharing and access merge, generating a specific form of transparency as engagement. This resembles the transparency experience we discussed in Section 4.1 in which the individual messy workspace becomes visible to the immediate team members. This time the difference being that the transparency expands from the immediate team towards the customers.

In this section, we have shown that transparency through Miro has been utilised to engage the audience in the design process. Miro has become a strategic tool for designers when they need more involvement and hands-on input from the stakeholders. It is important to note that this particular type of transparency as engagement has only been found in C2 and C3. While in C2, transparency as engagement has been experienced in sharing with both internal and external stakeholders, in C3, it has only been observed with internal stakeholders. Sharing with external stakeholder practices in C3 seems counter to the engagement and will be presented in Section 4.6. In C1, we have not found any Miro practices that can be considered as engagement with internal or external stakeholders. They will also be presented in Section 4.6.

4.4. Transparency as ownership

The experience of transparency is mentioned in a relatively positive manner in previous sections. However, in certain cases, transparency is experienced as being too much, and a sense of ownership has emerged.

Regardless of their company, the participants reported a similar practice of using Miro: ‘As a rule of thumb, all the [Miro] boards are shared with the rest of the team. (C1-1)’ They claim they do not feel ownership of the boards and collaboratively and openly work in them.

Although designers claim that ownership has not been an explicit issue, the accounts indicate implicit ownership of the Miro boards that is communicated through social dynamics. (C1-1) explains that there is a permission structure when one wants to adjust something that someone else is working on. If someone wants to apply a change, they either ask permission or verbally suggest the changes to the owner of the board to be applied later.

This shows that there is an implicit sense of ownership over the boards. It is not always a welcome idea that all the team members have free access to the boards and are able to apply changes at any time. Nevertheless, there are no official rules on ways of collaboratively working together on the boards to avoid the potential confusion caused by multiple people working on the same document. Asking for permission is expected when there is a need for adjustments despite the tool affording every user with the right to access and apply changes to the boards. Ownership might also be more obvious in some cases. (C2-4) shares an observation from their team:

If there are topics from the PO or from other people, most of the time they start their own board. And then I don't know why maybe it's kind of, I don't want to draw on your kind of board or I don't know if there is a personal touch to boards, but I also try not to draw on boards that I don't know. If we, for example, didn't create a board in the team from the beginning, I'm not touching it, you know? And I'm also not kind of adding stuff. (C2-4)

The account indicates that whoever initiates a certain topic to work on tends to create a new board in which they hold the implied ownership. (C2-4) continues by explaining that it would be unexpected to find sticky notes on a board that they have created and that has not yet been introduced to the team.

Social dynamics identify the behaviour on the boards. If a board is created in a meeting to work on together from the beginning, then the ownership is equally distributed. The board participants do not hesitate to go into the board and apply changes when necessary. On the other hand, if an individual creates a board and it is not yet introduced to the rest of the team, then it may be considered a private board (although technically anyone can access it), and neither comments nor changes are welcome. When the participants are asked about the ways they communicate this rule in the team, they say that it is ‘common sense’ or ‘nice behaving’.

This type of sharing practice in Miro contradicts the ones mentioned in Section 4.1. Although the threshold for sharing early work is usually low, there still is a limit to transparency. Designers want to be in control of when to share and when to receive feedback. The tool allows all the team members to access and apply changes. However, Miro's affordance of open access, users' expectations of being in control, and team dynamics become entangled and limit transparency when it is an unwanted experience and creates control over the individual work. This specific entanglement shows that Miro is not used according to what it affords; it is used despite its affordances. It ensures full access and the ability to adjust anything on the board. However, team members do not feel authorised to apply changes under certain circumstances. Although technically open, some Miro boards are not socially open to changes. In other words, Miro has been transformed by implicitly limiting transparency, and the sense of ownership has been the means for this.

Similar to Sections 4.1 and 4.2, a sense of ownership has only been observed within the immediate team practices during which all the boards are always shared with the team members. We have not found a similar practice when sharing with other internal stakeholders or external stakeholders, since sharing with them entails its own dynamics that might vary from one organisation to another (see Sections 4.6 and 4.3).

4.5. Transparency as surveillance

Similar to the sense of ownership discussed in the previous section, the experience of surveillance emerges when transparency is unwanted. Ownership pertains to the desire to possess personal space and exercise authority over when and how it is shared with others for feedback. Conversely, surveillance involves being monitored while working simultaneously with others.The presence of other people on the same board watching what is happening creates a feeling of surveillance. (C2-3) explains it as follows:

I feel it [surveillance] even when I'm writing something …Think about it, when you are creating a file on a board with people, you are the one who writes on that slide. Then, one gets nervous while writing. Because they're watching you. (C2-3)

Another participant shared a specific example in which the presence of other people looking at unfinished things annoys the person working on that board.

Like recently, I was in a kickoff session with the delivery manager who had created it [a Miro board]. We had all gone ahead and had a look at what was coming, which frustrated him a little bit. But yeah, that is an issue. That's probably the thing that you don't think about until you're in that situation and people are looking ahead. No, no, no! That is not meant for you? Not for right now. (C1-1)

When employees require privacy, transparency, which is often a celebrated practice, is experienced as an invasion of the personal workspace and a loss of control over the work. (C1-1) talks about the practice of creating a personal board to manage the over-transparency when they need to make sense out of complex information as follows:

I'll be working on a thing in Miro, you can see when someone else's popped in and tracking a thing. And that makes me feel nervous …I was working on something up there and I was like, Oh, hang on. Let me just think about it a little bit more. And I moved it outside of there [to a personal board] and then moved it back in when I was done. (C1-1)

They draw attention to the visibility of attendants on the boards. The virtual presence of colleagues visible through the moving cursors on a board creates the feeling of being watched. In that case, the tool generates unintended feelings, such as stress and nervousness, that eventually ‘add pressure and hinder the process’ (C1-1). As a reaction, the designers suspend the transparency by creating a personal board as a ‘space to think before sharing’ (C1-1). When they feel ready, they transfer the work back to the shared board. This practice appears to be a strategy employed to control transparency when it is perceived as being too much.

In another instance, (C3-1) draws attention to the co-creation sessions that happen in the shared Miro boards in which multiple people are present and are expected to build on top of each other's work; this can result in being an overwhelming experience, especially when there is a mismatch between personal and expected ways of working.

I think better by myself, you know? So my mental effort in thinking together with other people is way higher than just kind of by myself thinking and putting stuff together. (C3-1)

Similarly, (C3-2) states that in some cases, they need their ‘own space’ for their ‘own thinking’ and need to make ‘separate decisions’. In those cases, transparency is an unwanted practice that must be managed with additional new practices, such as occasionally agreeing in the team to work on separate boards until they feel comfortable with sharing. Although sharing the personal mess (see Section 4.1) has been reported as being a welcome practice that eases communication, in certain cases, the level of messiness can be distracting for other colleagues. (C3-2) shares an example:

I need this space where I can be messy. And that's like my page. And then my teammate, who he's like very pragmatic and he has a very structural way of working. And he said like, yeah, I went there once and I couldn't understand. You just do your thing. And when you're done with the thing you're doing …Then I will kind of copy, paste it somewhere where we can talk about it. (C3-2)

Different ways of using Miro according to different thinking structures result in difficulty understanding each other. This account contradicts the discussion in Section 4.1 in which the participants reported being more open to sharing their personal mess with their colleagues. This implies that the same practice or experience can be perceived as either positive or negative depending on the different entanglements of the tool and the user in various practices.

The experience of surveillance has resulted from the entanglement between the user's need for privacy and space for personal thinking, and the constant visibility afforded by Miro. In certain cases, moving cursors that indicate the presence of others is also part of the entanglement that intensifies the feeling of surveillance.

In this section, we presented the way in which transparency through Miro can be experienced as surveillance. The designers' intentions and their ways of working and thinking become entangled with Miro's affordances, thus generating a feeling of surveillance. In these cases, designers use their own strategies and workarounds by contravening the tool's affordances in order to cope with the surveillance.

4.6. Transparency as vulnerability

When transparency is experienced as being too revealing, it generates a sense of vulnerability. Vulnerability emerges when sharing with other internal stakeholders (outside the immediate team) and external stakeholders. In C1 and C3, we have found unique practices to avoid vulnerability by limiting the transparency that Miro affords. In C1, designers work with politicians who are the decision-makers for the outcome of the design process (see Section 3.2.3). (C1-1) talks about the internal dynamics and communication challenges within the organisation as follows:

I think it just comes with working in a political environment. Just being aware of the big beans and the small beans, and that's generally the politics within the organisation. So, you've got to be careful about who you speak to and how you talk about a thing. People bridge the gaps. And I mean, we saw quite recently where somebody mentioned a timeline and they were talking hypothetical and then that timeline gets communicated elsewhere. And all of a sudden it just grows legs. (C1-1)

The account above exemplifies the internal dynamics that influence the sharing and communication patterns. (C1-1) also highlights the difference between the dynamics within and outside the team as follows:

So you gotta be quiet, you gotta be quite careful. And, when you say something [to the internal stakeholders who are not the immediate team] …So at a team level, we might be quite spicy, and sometimes just bouncing that off of the lead will help you understand how best to communicate it [with the internal stakeholders]. (C1-3)

In such a work environment, employees believe that transparency in communication outside the immediate team is likely to generate vulnerabilities and must be controlled. Unlike unlimited access to the boards within the immediate team, the communication and sharing practices with internal stakeholders are intentionally restricted. This reflects on Miro's usage and the transparency that has been associated with it. The boards are all open to the immediate team; however, people outside the immediate team (politicians and decision-makers) are not welcome on the boards. Although feedback from and collaboration with them are required, their access to the actual workspace is strictly restricted. The team does not want internal stakeholders to be equal contributors and, thus, able to apply changes on the Miro boards. (C1-1) states that ‘You don't share the board with anyone who isn't in the team’.

Sharing the actual workspace, which is an OCW board, with internal stakeholders has been associated with vulnerability. Inviting internal stakeholders into Miro boards renders the teamwork open for unwanted interventions. This creates the possibility of the design process moving in an undesirable direction. If it is required that the information in the Miro board is shared with internal stakeholders, only an exported image is shared to ensure that they cannot apply changes by themselves. The feedback based on the exported image is collected to be applied later by the designers. This practice shows that the spontaneity of the sharing (see Section 4.1) does not exist outside of the immediate team in C1. In this specific performance of Miro, the challenging communication dynamics within the organisation, concerns of the designers to receive unsolicited intervention, and Miro affordances that allow everyone to apply changes become entangled and lead to the exclusion of the affordances that creates transparency. A similar practice of limiting transparency is also present when sharing with the external stakeholders in C1. External stakeholders are the county residents who are the beneficiaries of the services designed by C1. The design team also needs to share and communicate with the residents to provide information or receive feedback. The communication, which was held in the form of face-to-face workshops with the residents before the pandemic, started to be held through Miro after the lockdown. (C1-1) explains the challenges of communication with external stakeholders:

In the public sector, things are a little bit more sensitive, just because you're working with people's services and that can get so tricky. It definitely, does change the way that, as I mentioned, you've got to be conscious of the audience. They're [the topics] very emotional almost, uh, for instance, things like adoption and that kind of stuff is very much a people type of service. There are just those sorts of sensitivities that you need to communicate differently to different people. (C1-3)

When not shared carefully, sensitive topics have the potential to generate vulnerability, thus drawing a reaction from the residents. The team needs to agree on not only what will be shared but also how those things will be shared. This requires careful preparations beforehand, which decreases transparency by removing the spontaneity of the sharing and communication. As stated by the designers, when they need to communicate with the residents, they first identify the target group and then review the stakeholder maps to see what they care about, need, and how they want to receive information.

(C1-2) states that unlike the sharing practices within the team, sharing the boards, which are the team's workspace, with the external stakeholders is not an acceptable practice. Nonetheless, since the organisation adopts participatory design practices (see Section 3.2.3), designers need to co-create with external stakeholders. Therefore, they selectively transfer the information from the team boards to the workshop boards that are prepared for sharing with the stakeholders, carefully considering the sensitivities that the topics might entail. In the case of sharing with the external stakeholders, the experience of transparency and the means by which it is mitigated are the consequence of the entanglement between the way the organisation provides value (providing service design for the citizens), the sensitive topics to be communicated, the target audience of the service, and the designer's intentions of co-creating with and getting feedback from with the residents.

We have observed another form of transparency as a vulnerability in C3 when sharing with external stakeholders. The company's external stakeholders are its customers who receive a consultancy service. As stated by (C3-3), designers ‘have to play the part of the professional and expert (C3-3)’. This reflects on the sharing practices with external stakeholders. (C3-2) reports on that by comparing their approach to sharing with internal and external stakeholders: