ABSTRACT

Problematic smartphone use (PSU) is particularly prevalent among young people and refers to uncontrolled smartphone use that results in harm or functional impairment. The pathway model asserts that there are distinct patterns of PSU (addictive, antisocial, and risky smartphone use). Motives may be key factors in the aetiology of PSU. However, most of the research investigating which motives influence PSU has measured smartphone use motives by adapting items designed to assess motives for other forms of media. This approach is a limitation, as it may miss motives unique to the context of smartphone use. Addressing this, the present study used a qualitative approach to investigate which motives may influence distinct patterns of PSU. Reflexive thematic analysis of focus group data (N = 25 participants aged 18–25 years) indicated that smartphone use to cope with discomfort (low mood and anxiety, social awkwardness, boredom, safety), obtain rewards (validation, pleasure), conform to perceived social norms, and for their instrumental value differentially motivated addictive, antisocial, and risky patterns of PSU. Some of these motives (social awkwardness, feel safe, and conform) are not well represented by current measures of smartphone use motives. Therefore, a new comprehensive measure of smartphone use motives may be needed.

Smartphones have become one of the most widely adopted technologies globally, with almost 6.5 billion smartphone mobile network subscriptions as of 2022 (Ericsson Citation2023). The widespread adoption is unsurprising given the many capabilities of smartphones. For example, smartphones allow people to make voice calls, send messages, access social media, play games, and browse the internet (Panova et al. Citation2020). While smartphone use may improve the wellbeing of some people (Lavoie and Zheng Citation2023), for others it can become excessive or uncontrolled and result in harm or functional impairment, termed problematic smartphone use (PSU; James et al. Citation2023). PSU has been observed at higher levels among adolescents and young adults, although this may be a generational cohort rather than developmental effect (Busch and McCarthy Citation2021). Given the prevalence of smartphone use and the potential for some to develop PSU, a large body of literature has investigated aetiological mechanisms of PSU (reviewed in Busch and McCarthy Citation2021). Framed with several key theories, including the uses and gratifications theory, motives for smartphone use have been identified as important in the aetiology of PSU (reviewed in Mostyn Sullivan and George Citation2023).

1.1. Motives for smartphone use

The uses and gratifications theory (Katz, Blumler, and Gurevitch Citation1974) was developed to explain why people engage with particular types of media. Rubin (Citation2002) described the theory as a functionalist perspective of media use, where people use certain types of media to gratify their needs and desires. Within this framework, motives represent specific gratifications people seek through engagement in media. Research using this framework focused on developing typologies of motives for various types of media, including smartphones (e.g. Lin, Fang, and Hsu Citation2014; Moon and An Citation2022; Vanden Abeele Citation2016). In their review of studies based on the uses and gratifications theory conducted between 1940 and 2011, Sundar and Limperos (Citation2013) noted that the configuration of motives identified for different types of media has varied minimally over time. For example, social, escape, and entertainment motivations identified for television use (Greenberg Citation1974; Rubin Citation1981) also motivated social media usage (Joinson Citation2008). Sundar and Limperos suggested that this is probably because modern researchers have moved away from a two-stage methodological process. In earlier studies, researchers would conduct focus groups (or another qualitative approach) to explore motives for a specific type of media use (e.g. Greenberg Citation1974; Sherry et al. Citation2006). Findings would then inform the development of questionnaire items, with factor analysis performed on participant responses to construct a typology and quantitative measure of motives. More recently, however, researchers have typically skipped the more exploratory qualitative stage and adapted motives questionnaire items originally developed for older media to fit new media. Assuming motives reflect both innate personal needs and the possible functions of a behaviour (Sundar and Limperos Citation2013), this leaves a gap whereby motives unique to the context and capabilities of new media may be missed.

This trend of constructing new motives typologies/measures by adapting older motives items is evident in the smartphone use literature. In their systematic review, Mostyn Sullivan and George (Citation2023) identified 19 separate smartphone use motives measures used across the PSU literature. They noted that almost all smartphone use motives measures were developed by adapting prior measures designed for other behaviours to the context of smartphone use. For example, smartphone use motives measures developed in Shen et al. (Citation2021) and Elhai et al. (Citation2020) adapted items previously designed to assess motives for social networking site use (Wang et al., Citation2015) and internet use (Brand, Laier, and Young Citation2014), respectively. Other studies that focussed on motives for smartphone use in particular contexts – such as using a smartphone to access the internet (Tirado-Morueta, García-Umaña, and Mengual-Andrés Citation2021) and while a tourist (Moon and An Citation2022) – used the same method. Even where some qualitative approaches were applied to inform the development of a smartphone use motives measure (Lin, Fang, and Hsu Citation2014), the qualitative analysis was not reported. This has resulted in the development of multiple smartphone use motives typologies/measures that may have missed motives unique to the context of smartphone use. As a consequence, research may have missed motives that contribute to PSU.

1.2. The role of motives in problematic smartphone use

While PSU has been likened to a behavioural addiction (e.g. Yu and Sussman Citation2020), it is not recognised as an addictive disorder in diagnostic manuals (American Psychiatric Association Citation2013; World Health Organization Citation2018). Smartphone content (i.e. applications) is considered the primary object of problematic engagement, rather than the device itself (Elhai, Yang, and Montag Citation2019; Montag et al. Citation2021). With the diverse range of content and functions offered by smartphones, researchers have increasingly emphasised the need to focus on the distinct patterns and contexts of smartphone use that constitute PSU (Elhai, Yang, and Levine Citation2021; Montag et al. Citation2021).

One conceptualisation of PSU that considers distinct patterns of smartphone use is the pathway model (Billieux et al. Citation2015). This model proposes that PSU includes addictive (e.g. salience), antisocial (e.g. use during in-person conversations), and risky (e.g. use while driving) patterns of smartphone use. Each pattern is thought to be differentially influenced by excessive reassurance, impulsive, and extraversion aetiological pathways (Billieux et al. Citation2015; Canale et al. Citation2021; Kuss et al. Citation2018). It has been suggested that each of these pathways is characterised by distinct motivations (James et al. Citation2023; Mostyn Sullivan and George Citation2023), although precisely which motives remains unknown.

A growing empirical literature has investigated the association of motives with PSU. This research is often framed with the compensatory internet use theory (Kardefelt-Winther Citation2014), which proposes that problematic internet use is driven by an effort to compensate for negative emotions and life circumstances. Another theoretical framework used in the PSU literature is the alcohol use motivational model (Cox and Klinger Citation1988), which considers motives to be the final common pathway to behaviour, funnelling the influences of all other relevant psychosocial factors (Cooper et al. Citation2016). Motives are considered to reflect personal and environmental inputs (George et al. Citation2018) and are defined according to whether the desired effect is positively or negatively reinforcing and derived internally or externally. This results in four possible motives categories: (a) internally generated positively reinforcing motives (e.g. enhancement); (b) internally generated negatively reinforcing motives (e.g. coping); (c) externally generated positively reinforcing motives (e.g. social); and (d) externally generated negatively reinforcing motives (e.g. conformity; Cooper et al. Citation2016). Applying these models to PSU, motives can be conceptualised as proximal drivers of smartphone use to achieve desired effects, that are influenced by and reflect a range of personal and environmental inputs; when the desired effect of smartphone use is achieved, use is reinforced and may become excessive and uncontrolled.

Consistent with these theories, in their systematic review, Mostyn Sullivan and George (Citation2023) found that smartphone use motives were associated with PSU and that there were indirect effects of certain psychopathological and personality factors on PSU via motives. However, there was considerable heterogeneity in the identified smartphone use motives measures and all were generally adapted from other measures designed to assess motives for other behaviours. Additionally, no studies examined whether motives were differentially related to distinct patterns of PSU (e.g. addictive, antisocial, risky). This makes it difficult to determine which motives are key to PSU, emphasising the need to explore motives specifically for smartphone use and their influence on distinct patterns of PSU.

A small number of qualitative studies provide insight into what motivates smartphone use and/or PSU (e.g. AlBarashdi and Bouazza Citation2019; Fullwood et al. Citation2017; Harkin and Kuss Citation2021; Lepp, Barkley, and Li Citation2017; Ochs and Sauer Citation2022; Yang, Asbury, and Griffiths Citation2019). After interviewing university students, Lepp, Barkley, and Li (Citation2017) found that social, boredom relief, planning, habit, obligation, procrastination, to feel good and relaxation motives influenced leisure smartphone use. Only boredom alleviation distinguished between high frequency and low frequency smartphone users, suggesting it may be important for PSU. Ochs and Sauer (Citation2022) conducted a qualitative exploration that identified smartphone use motives which influenced what they termed sub-critical smartphone use, defined as smartphone-related behaviour or consequences that are disturbing but less severe than PSU. Using an online questionnaire with open ended questions to collect data, they found that inevitability, habitual use, avoiding unpleasant circumstances, need satisfaction, and fulfilling social expectations motivated smartphone use. Notably, some motives identified by Lepp, Barkley, and Li (Citation2017) and Ochs and Sauer (Citation2022) – such as obligation or fulfilling social expectations – are not well captured by existing smartphone use motives typologies or measures. This highlights that new motives for smartphone use may be driving the distinct ways people use their smartphone. To our knowledge, no prior research (qualitative or quantitative) has explored motives for smartphone use and identified those that may influence the distinct patterns of PSU (i.e. addictive, antisocial, and risky).

1.3. The present study

This study aimed to explore young adults’ motives for smartphone use and identify motives that may influence addictive, antisocial, and risky patterns of smartphone use. Young adults were the focus given PSU is higher among this age group (Busch and McCarthy Citation2021). The study addresses two key gaps in the literature: (1) an ongoing concern regarding the development of smartphone use motives measures is whether current measures capture all the relevant motives, given the ever-expanding capabilities of smartphones (reviewed in Mostyn Sullivan and George Citation2023); and (2) no studies have investigated which motives influence the three distinct patterns of PSU that have been identified in the literature (i.e. addictive, antisocial, and risky; Billieux et al. Citation2015). To address these knowledge gaps, we used a qualitative methodology to gain an in-depth understanding of young adults’ motives for smartphone use and potential associations with patterns of PSU. This knowledge is critical to understanding the aetiological pathways to PSU and to inform development of mitigations and interventions.

2. Method

2.1. Participants

Young adults aged 18–25 years, currently residing in Australia, and who use a smartphone were eligible to participate in the study. Participants were recruited via Facebook advertisements and a snowball methodology. Twenty-five young adults (Mage = 21.70, SD = 2.03) were recruited to participate in our focus groups (64% female; 12% non-binary; 48% full-time students; 24% full-time employees). Participants used their smartphones for 2–9 hours on weekdays (M = 6.04, SD = 1.74) and 4–12 + hours on weekends (M = 6.80, SD = 2.25). There were no relationships between the researchers and participants prior to commencement of the study.

2.2. Materials and procedure

Five focus groups (n = 3–7 participants) were conducted. All focus groups ran for approximately 90 minutes and were facilitated by the first author (a male PhD in Clinical Psychology candidate). They were conducted between October and November 2021 during the Covid-19 pandemic, so were held online via Zoom. Only the first author and participants were present for the focus groups. Participants were not informed of any personal characteristics relevant to the first author, who was, however, visible to them on Zoom. Prior to commencement, participants provided informed consent verbally and via an online form on Qualtrics. The focus groups were facilitated using a semi-structured question format that encouraged participants to discuss information relevant to their (and their perception of other young adults’) smartphone use. The initial question (‘What reasons do people in your age group have for using their smartphones?’) was intended to initiate discussion about motives for smartphone use. An additional question (‘What’s negative about smartphone use?’) was used to instigate discussion about PSU in general. Follow up prompts were used to facilitate a discussion about patterns of PSU: addictive (Have you ever felt like you use your smartphone more than you’d like to?’); antisocial (‘What contexts or situations do people your age use their smartphones in but they probably shouldn’t?’); and risky (‘In what ways can smartphone use be dangerous or risky, whether to the user or someone else?’). During discussion about PSU, the facilitator included prompts to address motivations that influence PSU (e.g. ‘Why do you think you or other people use their phones in these ways?’). Each participant received a $40 online gift card at the end of the focus group. All focus groups were recorded, with permission, using Otter.ai. Ethics approval was obtained from the University of Canberra Human Research Ethics Committee (HREC 7035).

2.3. Data analysis

Focus group recordings were transcribed by the first author and the original recordings were then deleted. Transcripts were not returned to participants for comment, although they were given the opportunity to receive a summary report outlining findings from the data analysis. Transcripts were uploaded to NVivo 12 to facilitate analysis. We followed the approach proposed by Braun and Clarke (Citation2019). Data were analysed with reflexive thematic analysis, underpinned by an essentialist epistemology, considering the experiences, meanings, and reality of participants. A mixed inductive and deductive approach was taken to construct themes; while themes were generated bottom-up from the data, they were influenced by established theories relevant to motives and PSU which were used to develop the interview questions (e.g. the alcohol use motivational model and pathway model). An inductive approach was essential for the present study, which addressed key gaps in the literature that resulted from prior research employing a confirmatory approach. A semantic approach was used when constructing themes, analysing the explicit meanings of what participants stated during the focus groups.

Data analysis followed six stages, as outlined by Braun and Clarke (Citation2006). The first author familiarised themself with the data by reading and re-reading all transcripts. Next, the first author generated an initial coding scheme and coded the data. The second and third authors then reviewed extracts of the data to facilitate discussion concerning the initial codes, resulting in amendments. Code names were further improved throughout the analysis. The first author constructed codes into potential themes that reflected smartphone use motives. These themes were then reviewed by all authors to ensure they reflected the coded extracts and the dataset as a whole. These final themes were defined, named, and agreed upon by all authors. Finally, a report outlining the analysis, including selected vivid extract examples was produced. The report was written according to the Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Studies (Tong, Sainsbury, and Craig Citation2007). Extracts supporting themes are followed by a parenthesis containing the participant (P) and focus group (FG) number.

3. Results

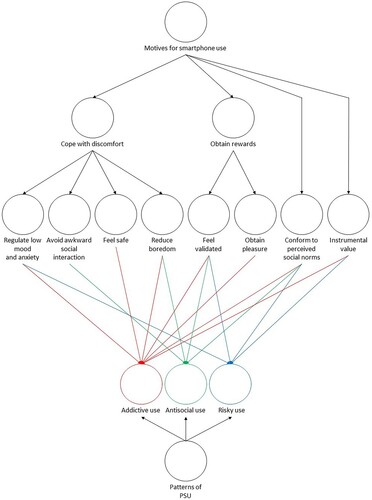

Through reflexive thematic analysis (Braun and Clarke Citation2019), four themes that reflect smartphone use motives (which may influence PSU) were constructed: (a) cope with discomfort; (b) obtain rewards; (c) conform to perceived social norms; and (d) instrumental value. Our analysis indicated that the themes likely differentially influenced the distinct patterns of PSU outlined in Billieux et al.’s (Citation2015) pathway model (i.e. addictive, antisocial, and risky patterns of smartphone use). Each of the themes/motives, and how they relate to patterns of PSU, are summarised in .

Figure 1. Thematic Map of Motives and their Influence on Problematic Smartphone Use.

Note. PSU = problematic smartphone use. Arrows between motives and patterns of PSU show that a particular motive influenced that pattern of PSU.

3.1. Theme A: cope with discomfort

Addictive, antisocial, and risky patterns of smartphone use were motivated by efforts to avoid or reduce emotional or physical discomfort. Four sub-themes revealed how smartphone use to reduce certain feelings differentially influenced distinct patterns of PSU. Specifically, motives to regulate low mood or anxiety influenced addictive and potentially risky patterns of smartphone use. Smartphone use to avoid boredom motivated addictive and antisocial patterns of smartphone use. Motives to reduce social awkwardness influenced an antisocial pattern of smartphone use. Smartphone use to feel safe and reduce fear motivated an addictive pattern of use. Each of these subthemes is discussed below.

3.1.1. Regulate low mood and anxiety

An addictive pattern of smartphone use was motivated by efforts to regulate low mood or anxiety and associated physical discomfort. Exemplified by the following extract, efforts to reduce such feelings appeared to motivate smartphone use for extended periods of time due to it being the most easily accessible source of comfort.

‘ … For me, like if my PMDD [Premenstrual Dysphoric Disorder] is real bad or anything else is going on … I will be inside, I'll be on my phone more. One of my partners has ADHD [Attention Deficit Hyperactive Disorder], so they need that constant stimulation otherwise they're just they're not having a good time, and a phone gives you that constant stimulation, so they'll end up spending a long time on their phone … ’ (P3 FG3)

‘I think I definitely just feel kind of exposed [without access to my smartphone] … if I'm in an uncomfortable situation and I need to escape with my phone, I can't do that’. (P2 FG4)

While infrequently discussed, for some it appeared that smartphone use to regulate low mood may influence a risky pattern of smartphone use. Specifically, it was noted that using a smartphone to connect with strangers and meet them in person was worth the associated risk to decrease loneliness, as per the following discussion.

P1: ‘The only one I can think of for me personally, maybe using dating apps and speaking to potentially people that are like creeps … ’

P4: ‘ … it was literally the only way that I could make friends and connect with people and feel not so alone’. (FG1)

3.1.2. Avoid awkward social interactions

Efforts to avoid or reduce uncomfortable emotions also motivated an antisocial pattern of smartphone use. However, rather than this being to reduce general feelings of depression or anxiety, it appeared to be motivated by reducing social awkwardness or social anxiety, as illustrated by the following extract.

‘ … Yeah, I've definitely had a few Tinder dates where I met them, it's just so awkward that I find myself bringing out my phone and casually it turns into a situation where you know both of us are just kind of you know doing silly small talk but then also scrolling’. (P1 FG1)

‘I think of course, again, we're so used to talking online that I feel like humans as humans, we've kind of feel awkward in those spaces of empty silences so immediately able to turn to their phone’. (P4 FG2)

3.1.3. Feel safe

Carrying (without necessarily using) a smartphone was motivated by a desire to reduce fear and feel safe. Without access to a smartphone, young adults often felt they would not have access to the resources required to be safe in an emergency (e.g. family, friends, finances). This motivation appeared to influence an addictive pattern of smartphone use, as per the following discussion.

P3: ‘ … When I had my old phone, I was quite anxious about going out at night. I'd check five times that my power bank was charged and keep that connected … ’

P1: ‘ … In my head, I'm always trying to plan out my day, like how much battery I'm willing to use … What if I need this 5 percent for later on … I think like it does cause mental strain before I head out, just trying to plan my day. And I feel like it's such a huge factor especially for I don't know other special people who feel more vulnerable, like I'm pretty small as well, and you know, a person of colour. Probably gonna get targeted. So, there's like a lot of other different considerations and I think I rely on my phone as a bit of a lifeline when I go out … ’ (P1 FG3)

3.1.4. Reduce boredom

Addictive and antisocial patterns of smartphone use were motivated by efforts to alleviate boredom, as described in the following extract.

‘ … I had really short attention spans these days because I use my smartphone a lot, that sometimes I will be, you know, trying to do my homework or watching lectures, and it'll be really boring so I'm like, I'm going to make the most use of my time and then I'll browse on my phone … and I don't actually end up doing my homework … ’ (P2 FG5)

‘ … One of the more insidious things is oh I don't know what to do when I'm bored and I'm just going to fill up this time [by using my smartphone] so I have to have something to do … ’ (P1 FG3)

3.2. Theme B: obtain rewards

Smartphones were often used to feel good or obtain rewards, but only certain types of rewards motivated PSU. Using a smartphone to initiate and maintain social relationships was common, but it did not appear to influence PSU. However, when the desired reward was validation from peers or pleasure, it did appear to influence addictive and risky patterns of smartphone use.

3.2.1. Feel validated

An addictive pattern of smartphone use was motivated by an effort to obtain validation from peers, exemplified in the following quote.

‘ … I also find that the other reasons for why people use their smartphones and especially me, like I'm guilty of this, validation! It is addictive … you post pictures of where you've been, you've made selfies of yourself, and you want validation, you want people to be like, hey, that's really cool, I wish I was doing that, look at how cool you are. You do it to get likes and then you'll immediately do the same thing again to get more likes’. (P3 FG2)

P3: ‘ … I've just realised as well it also raises that link of people advertising their risk-taking behaviour online for sort of validation among groups that they're in. So, things like Snapchatting while driving, they'll also post things like them engaging in drug use or [inaudible] and stuff like that … ’

P2: ‘I know someone as well who does that who is always recording their speedometer just to show they’re speeding … ’ (FG2)

As demonstrated in the following extract, efforts to obtain validation may also influence smartphone use to engage with extremist narratives, a less commonly discussed behaviour that could be considered an antisocial pattern of smartphone use.

‘ … the biggest thing that comes to my mind is like incel culture, where men are like, I hate women, all women … They'll have this idea right and then they'll find other people who share that same experience … They'll be like, oh my god, this guy's experienced that too, this proves that all women hate men’. (P2 FG3)

3.2.2. Obtain pleasure

Smartphone use for pleasure motivated an addictive pattern of smartphone use, specifically excessive use. Smartphones were seen as a way to obtain pleasure by engaging in content that was otherwise not easily accessible. While this was framed as a positive aspect of smartphones, it was acknowledged that using them for pleasure was so rewarding that it reinforced excessive use, as described in the following extract.

‘ … I see it all as a chance to learn so many things I wouldn't have the chance to see. Just today I started following this new page on Instagram that shows close ups of basically cells through a microscope, and I'm just fascinated by it. And I thought oh wow, I would never be able to see these things if it wasn't for Instagram … These things make me so happy that I kind of forget the negatives or even that fuels the addiction to keep looking for good things’. (P2 FG2)

3.3. Theme C: conform to perceived social norms

Addictive and antisocial patterns of smartphone use were motivated by an effort to conform to a perceived social norm about responding to incoming communications. Specifically, participants expressed a belief that people expected quick responses to incoming communications. This triggered social pressure in some participants when messages were received, which motivated smartphone use to relieve that social pressure. This mechanism is outlined in the following extract.

‘ … The same kind of people get quite frustrated if you don't respond within five minutes of them sending you a message, even if it's not an ongoing conversation. If you just send someone a message out of the blue, there's kind of expectation they'll respond right away. And so, I think when someone sends you a message you kind of feel that pressure to respond quickly so they don't get frustrated with you’. (P2 FG1)

‘ … I feel like it's more like, oh crap, my mum's calling me, I'm going to pick up. It's more like that, my parents are mad, where am I. And they're going to pick up because their parents. It's not really like, oh, I'm gonna do a risky move here and talk to mum while I'm on the highway’. (P2 FG3)

3.4. Theme D: instrumental value

Smartphone use for instrumental value, such as to assist with organisation and navigation, appeared to also influence an addictive pattern of smartphone use. The following quote exemplifies this.

‘ … Without my phone it's just anxiety, because I rely on it so heavily for work, so I don't know if I'm about to get an email from a client, or if a meeting is being rescheduled, or if someone wants me to make a quick change on their commission that I'm in the middle of working on. And yeah, not having the option to access that information really does put me on edge’. (P3 FG3)

Smartphone use for instrumental value also influenced smartphone use while driving. In this case, the smartphones were specifically being used for navigation, with young adults believing that without their smartphone they would not be able to ‘get where [they] need to go’ (P2 FG1). Notably, when young adults use a smartphone for navigation, they generally are not holding and manipulating the device directly, but may mount it illegally, with non-GPS enabled vehicles forcing them to ‘rig up a phone’ (P2 FG1).

4. Discussion

The present study aimed to explore motives for smartphone use and identify those that may influence addictive, antisocial, and risky patterns of smartphone use among young adults. Four themes were constructed. The first theme reflected smartphone use to cope with discomfort, which included four subthemes. Smartphone use to feel safe and to avoid social awkwardness/anxiety appeared to influence an addictive pattern of smartphone use and an antisocial pattern of smartphone use, respectively. Smartphone use to regulate low mood and anxiety indicated addictive and potentially risky patterns of smartphone use, while smartphone use to alleviate boredom suggested addictive and antisocial patterns of smartphone use. The second theme reflected smartphone use to obtain rewards, which comprised two subthemes. Smartphone use to feel validated appeared to influence addictive, risky, and a somewhat novel form of antisocial smartphone use (engaging in extremist narratives), while use for pleasure motivated an addictive pattern of smartphone use. The third theme reflected how smartphone use to conform to perceived social norms influenced all aspects of PSU. Finally, the fourth theme demonstrated how smartphone use for its instrumental value motivated addictive and risky patterns of smartphone use.

4.1. Distinct patterns of problematic smartphone use

Across the focus groups, participants described their smartphone use in ways consistent with the distinction of addictive, antisocial, and risky patterns, as proposed in the pathway model (Billieux et al. Citation2015; Kuss et al. Citation2018). Some reported experiences that aligned with behavioural addiction models – such as Griffiths’ (2005) components model – included excessive use, salience, and withdrawal. Young adults described using their smartphone in inappropriate or prohibited contexts (e.g. while working or studying and during in-person conversations), which is consistent with antisocial smartphone use as conceptualised by Billieux et al. (Citation2015) and Kuss et al. (Citation2018). Use during in-person conversations being commonly identified as an antisocial pattern of smartphone use was notable, as it is not directly assessed by any version of the measures generally used to operationalise the pathway model’s addictive, antisocial, and risky patterns of smartphone use (Billieux, Van Der Linden, and Rochat Citation2008; Kuss et al. Citation2018; Lopez-Fernandez et al. Citation2018). Less commonly discussed behaviours that could also be considered antisocial patterns of smartphone use were using a smartphone to engage with extremist narratives online and cyberbullying, the latter of which was categorised by Billieux et al. (Citation2015) as an antisocial pattern of use. Smartphone use while driving was identified as the primary risky pattern of smartphone use engaged in by young adults generally, but the risks were acknowledged. While less common, using a smartphone to connect with strangers to meet in person was also considered a potentially risky pattern of use by some young adults. These findings highlight the ongoing relevance of the pathway model in conceptualising PSU. That is, PSU may not simply reflect addiction-like symptoms associated with smartphone use, but rather is a multifaceted construct characterised by distinct patterns of smartphone use.

4.2. Integrating motives with the excessive reassurance pathway to problematic smartphone use

Findings from the present study have potential implications for the excessive reassurance pathway, which was originally proposed to drive an addictive pattern of smartphone use. According to this pathway, those with elevated levels of certain psychopathology (e.g. anxiety) and personality traits (e.g. neuroticism) use their smartphone excessively to obtain reassurance from others, thereby reducing their distress (Billieux et al. Citation2015). Like the compensatory internet use theory (Kardefelt-Winther Citation2014), the excessive reassurance pathway reflects a negative reinforcement pathway to PSU. Broadly consistent with this, an addictive pattern of smartphone use was motivated by efforts to reduce depression, anxiety, and fear. However, rather than smartphones being used specifically to seek reassurance from others, results demonstrated that young adults engaged in smartphone content generally to distract from or reduce their distress. This appeared to influence both use for excessive periods of time and a reliance on the smartphone such that feelings of distress akin to withdrawal were experienced if the phone was inaccessible. These findings are consistent with prior quantitative research that has identified an association of depression and anxiety with PSU (reviewed in Augner, et al., 2023), as well as an association of mood regulation smartphone use motives with PSU (reviewed in Mostyn Sullivan and George Citation2023).

Our findings suggest that the excessive reassurance pathway may also influence an antisocial pattern of smartphone use via efforts to avoid awkward social interactions. Specifically, when young adults experience social anxiety during in-person social interactions, they may use their smartphone as a safety behaviour to reduce distress or avoid interacting. This finding is broadly consistent with prior quantitative research which has found an association between social appearance anxiety (Karaoglan Yilmaz et al. Citation2023; Yilmaz et al. Citation2023) or social anxiety (Chen and Huo Citation2022; Elhai, Tiamiyu, and Weeks Citation2018; Wei et al. Citation2023) and PSU, as well as social anxiety and phubbing (i.e. smartphone use during in-person social interactions; Chu et al. Citation2024; Chu et al. Citation2021; Yilmaz et al. Citation2023). However, to the authors’ knowledge, no prior study has quantitatively tested whether smartphone use motives mediate the relationships of social anxiety with PSU or phubbing (Mostyn Sullivan and George Citation2023).

Additionally, findings from the present study suggest that the excessive reassurance pathway may influence addictive, antisocial, and risky patterns of smartphone use via motives to conform to social norms about responding to incoming communications. Young adults noted that people expected quick responses to communications on a smartphone. They reported feeling pressure when notifications were received, which was relieved by responding, regardless of whether they were engaged in another important activity that should not be interrupted, such as studying or driving. Framing this within the excessive reassurance pathway, this finding suggests that those who are insecure in their personal relationships (e.g. low self-esteem, insecure attachment) may be more likely to conform to social norms about response times to avoid disapproval from others. Notably, while there is an established association of low self-esteem (Casale et al. Citation2022) and insecure attachment (e.g. Eichenberg, Schott, and Schroiff Citation2019; Parent, Bond, and Shapka Citation2023; Sun and Miller Citation2023) with PSU, to the authors’ knowledge no study has investigated whether conformity (or other) motives mediate these relationships.

Finally, participants suggested that some young adults engaged in a potentially risky pattern of PSU (using their smartphone to connect with strangers and meet them in person) due to an effort to regulate low mood caused by loneliness. While using a smartphone to meet strangers in person was not originally identified by Billieux et al. (Citation2015) as a risky form of smartphone use in their pathway model, some young adults in our study perceived it to be a potentially risky behaviour. The inclusion of this behaviour as a risky form of smartphone use is accordant with a growing literature that has identified risks associated with online dating application usage (reviewed in Bonilla-Zorita, Griffiths, and Kuss Citation2021). The findings from the present study align with research that has found an association of loneliness (Coduto, Lee-Won, and Baek Citation2019) coping or enhancement motives (Castro-Calvo et al. Citation2018; Vera Cruz et al. Citation2024) with problematic online dating application usage.

4.3. Integrating motives with the impulsive and extraversion pathways to problematic smartphone use

Findings can also be considered within the context of the impulsive and extraversion pathways to PSU. The impulsive pathway describes those whose PSU is driven by impulsive personality traits and ADHD (Billieux et al. Citation2015). The extraversion pathway accounts for those whose PSU is thought to be driven by personality traits such as sensation seeking (Billieux et al. Citation2015). Research has found that boredom proneness is associated with ADHD (Golubchik et al. Citation2020; Malkovsky et al. Citation2012) and sensation seeking (Nabilla, Christia, and Dannisworo Citation2019), and reflected in facets of impulsivity (Whiteside and Lynam Citation2001). We found that smartphone use to alleviate boredom motivated both addictive and antisocial patterns of smartphone use. Young adults use their smartphones for extended periods of time to reduce boredom when they are not engaging in any other activities and to alleviate boredom elicited by work or study related tasks (e.g. lectures). There was also some suggestion that young adults bully others via their smartphone to alleviate boredom. These findings are consistent with research which identified that psychological factors such as impulsivity, ADHD, and sensation seeking are associated with addictive and antisocial smartphone use (Billieux, Van Der Linden, and Rochat Citation2008; Canale et al. Citation2021; Kim Citation2018), and cyberbullying (Maftei, Opariuc-Dan, and Grigore Citation2024; Wang, Wang, and Zeng Citation2023). One prior study (Zhang and Wu Citation2022) examined whether a psychological factor related to impulsivity and sensation seeking (life history strategy) was associated with PSU via motives to alleviate boredom, finding a significant indirect effect. Moreover, research has found that online disinhibition (which is similar to sensation seeking) is associated with entertainment motivation for cyberbullying (which is similar to boredom alleviation motivation; Tanrikulu and Erdur-Baker Citation2021). Additionally, Zhang et al. (Citation2022) found a significant indirect effect of sensation seeking on cyberbullying via boredom experience. However, we are not aware of any study that has examined whether motives to alleviate boredom mediate the effect of factors such as impulsivity, ADHD, or sensation seeking on cyberbullying.

Our findings may add nuance to the extraversion pathway’s influence on a risky pattern of smartphone use. The extraversion pathway suggests that some people with heightened levels of sensation seeking use their smartphone while driving for stimulation or arousal (Billieux et al. Citation2015). We did not identify stimulation or arousal as a motive that influenced PSU. However, it appears that some people who drive dangerously (potentially for stimulation) will use their smartphone to share such behaviour to obtain validation from their peers. This builds on previous qualitative research which has found that young adults share images and videos of themselves driving over social media while they are driving (George et al. Citation2018) by providing a possible motivation for the behaviour.

4.4. Additional aetiological pathways to problematic smartphone use

There were motivations that appeared to influence PSU that do not clearly align with any of Billieux et al.’s (2015) pathways. Some young adults used their smartphone to obtain validation, which in addition to influencing a risky pattern of smartphone use as outlined above, motivated an addictive and novel form of antisocial smartphone use (engaging in extremist narratives). Others used their smartphone to obtain pleasure by learning new things, which due to this being a particularly rewarding behaviour, reinforced excessive use. Smartphone use for instrumental value was also associated with the development of an addictive pattern of smartphone use. Users reported a dependence on their smartphones due to the many functional affordances they provide. This appears to cause some people to experience distress when their phone is not accessible, similar to the addiction symptom of withdrawal. It should be noted here that it has been proposed theoretically that motives can be categorised according to their valence (positive or negative reinforcement) and source (reinforcement is internally or externally sourced; Cooper et al. Citation2016). Smartphone use for its instrumental value does not necessarily have a clearly identifiable valence, so may be better conceptualised as a type of smartphone use and not a motive for use.

4.5. Implications for the measurement of motives for smartphone use

We identified several potential motives that are not well captured in current smartphone use motives typologies/measures. A key motivation for antisocial smartphone use identified in the present study was to avoid feeling awkward or anxious during social interactions. This motive can be considered a nuanced form of coping motives from the alcohol use literature (Cooper Citation1994) relevant specifically to the context of smartphone use. Coping motives broadly are reflected in multiple smartphone use motives typologies/measures (e.g. Elhai et al. Citation2020; Kim Citation2017; Zhang, Chen, and Lee Citation2014). Two prior measures of smartphone use motives have included an item that may be related to avoidance of social awkwardness (‘I use my smartphone to fill uncomfortable silence’), although in both cases it was aggregated with other items intended to assess general coping motives (Kim Citation2017; Kim, Seo, and David Citation2015). Motives to reduce social awkwardness may warrant a separate scale so that they can be measured independently, particularly noting that findings from the present study suggest that this and motives to reduce general anxiety and depression may each relate to distinct patterns of PSU.

We also identified a specific form of conformity motives not currently captured in smartphone use motives measures/typologies. Like coping motives, conformity motives were identified as a core driver of alcohol use (Cooper Citation1994) and similar motives are included in several smartphone use motives measures. However, conformity motives in the context of smartphone use are generally operationalised with items reflecting smartphone use to: appear cool (e.g. ‘I use my phone to be in fashion’; Vanden Abeele Citation2016); be liked by others (e.g. ‘I use my smartphone to be liked by my friends’; Zhang, Chen, and Lee Citation2014); or fit in with one’s peer group (e.g. ‘I use my smartphone because my friends use it’; Lee and Lee Citation2017). We identified that a key motive that influenced PSU was smartphone use to conform to perceived social norms about responsiveness to communications. Specifically, young adults believed that other people expected them to respond immediately, and they did so to ensure they did not offend or get rejected by others. Mostyn Sullivan and George’s (Citation2023) recent review of smartphone use motives measures did not identify any motives to conform to this perceived norm about responding, which is a key gap in the literature given the present study’s findings suggest it may influence addictive, antisocial, and risky patterns of smartphone use.

Finally, our findings suggest smartphone use to feel safe and avoid fear motivated an addictive pattern of PSU. Of the 19 established smartphone use motives measures identified in Mostyn Sullivan and George’s (Citation2023) recent systematic review, only two included safety motives (AlBarashdi and Bouazza Citation2019; Vanden Abeele Citation2016). These two measures were only used in two prior PSU studies, with both finding significant positive associations (AlBarashdi and Bouazza Citation2019; Vezzoli, Zogmaister, and Coen Citation2021). Therefore, while safety motives have rarely been included in smartphone use motives measures or examined in relation to PSU, the limited findings from prior studies and the present study’s findings emphasise their potential importance in influencing PSU.

Taken together, these findings highlight that at present there are key gaps in the current measurement of smartphone use motives. Addressing these gaps will enhance our understanding of PSU’s aetiology and inform intervention strategies. That is, fully understanding which motives influence PSU may inform the basis of interventions that focus on identifying what motivates a client’s PSU, so alternate (healthier) means of satisfying those motives can be established (Augner et al. Citation2022). Similarly, a more complete understanding of what motives influence PSU could inform educational campaigns aimed at reducing PSU by highlighting more adaptive means of satisfying certain motives. Additionally, understanding what motivates PSU may help clinicians formulate factors upstream from motives that are maintaining PSU, which could enable intervention strategies to be more effectively targeted. For example, if motives to reduce social awkwardness are identified as influencing a client’s PSU, clinicians may choose interventions that target a broader tendency towards experiencing awkwardness or social anxiety.

4.6. Limitations and directions for future research

While the qualitative approach taken in this study to exploring motives that influence distinct patterns of PSU represents a novel contribution to the literature, several limitations must be noted. Only Australians and 18–25 years were sampled, limiting generalisability of the findings to other populations. However, we also consider this a strength, given most of the research to date which has investigated the association of motives with PSU was conducted in East Asia or the United States (Mostyn Sullivan and George Citation2023). Moreover, young adults were the focus because PSU tends to be higher among this cohort (Busch and McCarthy Citation2021). Future research may seek to explore whether additional motives for smartphone use influence patterns of PSU among other age groups in different geographic regions. The qualitative design limits our ability to consider the causal relationships of motives on PSU. Nevertheless, our findings suggest there are motives not well captured in existing smartphone use motives measures that may differentially influence addictive, antisocial, and risky patterns of PSU. Therefore, understanding of PSU may be advanced with development of a new comprehensive smartphone use motives scale that incorporates findings from the present study. Such a scale could be used to examine whether motives differentially predict addictive, antisocial, and risky patterns of PSU. Moreover, research should examine whether there are indirect effects of relevant psychosocial factors from the pathway model (e.g. social anxiety, urgency, and sensation seeking) on addictive, antisocial, and risky patterns of PSU via motives, particularly using longitudinal designs. This may enhance our understanding of how motives operate in causal pathways to PSU, moving towards a motivational model of PSU.

4.7. Conclusions

The present study explored motives for smartphone use and identified several potential motives that may influence additive, antisocial, and risky patterns of smartphone use. Specifically, smartphone use to feel validated and to conform to perceived social norms about responding to communications related to addictive, antisocial, and risky patterns of smartphone use. Smartphone use to reduce boredom appeared to influence addictive and antisocial patterns of smartphone use, while smartphone use to regulate low mood and anxiety and for its instrumental value were related to addictive and risky patterns. Smartphone use to feel safe and obtain pleasure appeared to influence an addictive pattern, and smartphone use to avoid feeling awkward during in-person social interactions reflected an antisocial pattern of smartphone use. Taken together, findings enhance our theoretical understanding of the role of smartphone use motives in different aetiological pathways to PSU. Notably, we found that key motives for smartphone use that influenced PSU in the present study – smartphone use to avoid feeling awkward during social interactions, conform to perceived norms, and feel safe – are not well captured by existing smartphone use motives measures, suggesting the inclusion of these motives in a revised measure may be warranted.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- AlBarashdi, H. S., and A. Bouazza. 2019. “Smartphone Usage, Gratifications, and Addiction: A Mixed-Methods Research.” In Impacts of Mobile Use and Experience on Contemporary Society, edited by X. Xu, 86–111. Hershey, PA: IGI Global. https://www.igi-global.com/book/impacts-mobile-use-experience-contemporary/210608.

- American Psychiatric Association. 2013. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. Arlington, VA: Author. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.books.9780890425596.

- Augner, C., T. Vlasak, W. Aichhorn, and A. Barth. 2022. “Tackling the ‘Digital Pandemic’: The Effectiveness of Psychological Intervention Strategies in Problematic Internet and Smartphone use—A Meta-Analysis.” Australian & New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry 56 (3): 219–229. https://doi.org/10.1177/00048674211042793.

- Billieux, J., P. Maurage, O. Lopez-Fernandez, D. J. Kuss, and M. D. Griffiths. 2015. “Can Disordered Mobile Phone use be Considered a Behavioral Addiction? An Update on Current Evidence and a Comprehensive Model for Future Research.” Current Addiction Reports 2 (2): 156–162. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40429-015-0054-y.

- Billieux, J., M. Van Der Linden, and L. Rochat. 2008. “The Role of Impulsivity in Actual and Problematic use of the Mobile Phone.” Applied Cognitive Psychology 22 (9): 1195–1210. https://doi.org/10.1002/acp.1429.

- Bonilla-Zorita, G., M. D. Griffiths, and D. J. Kuss. 2021. “Online Dating and Problematic use: A Systematic Review.” International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction 19 (6): 2245–2278. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-020-00318-9.

- Brand, M., C. Laier, and K. S. Young. 2014. “Internet Addiction: Coping Styles, Expectancies, and Treatment Implications.” Frontiers in Psychology 5: Article 1256. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2014.01256.

- Braun, V., and V. Clarke. 2006. “Using Thematic Analysis in Psychology.” Qualitative Research in Psychology 3 (2): 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa.

- Braun, V., and V. Clarke. 2019. “Reflecting on Reflexive Thematic Analysis.” Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health 11 (4): 589–597. https://doi.org/10.1080/2159676x.2019.1628806.

- Busch, P. A., & McCarthy, S. 2021. “Antecedents and Consequences of Problematic Smartphone use: A Systematic Literature Review of an Emerging Research Area.” Computers in Human Behavior 114: Article 106414. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2020.106414.

- Canale, N., T. Moretta, L. Pancani, G. Buodo, A. Vieno, M. Dalmaso, and J. Billieux. 2021. “A Test of the Pathway Model of Problematic Smartphone use.” Journal of Behavioral Addictions 10 (1): 181–193. https://doi.org/10.1556/2006.2020.00103.

- Casale, S., G. Fioravanti, S. Bocci Benucci, A. Falone, V. Ricca, and F. Rotella. 2022. “A Meta-Analysis on the Association Between Self-Esteem and Problematic Smartphone use.” Computers in Human Behavior 134: Article 107302. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2022.107302.

- Castro-Calvo, J., C. Giménez-García, M. D. Gil-Llario, and R. Ballester-Arnal. 2018. “Motives to Engage in Online Sexual Activities and Their Links to Excessive and Problematic use: A Systematic Review.” Current Addiction Reports 5 (4): 491–510. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40429-018-0230-y.

- Chen, Y., and Y. Huo. 2022. “Social Interaction Anxiety and Problematic Smartphone use among Rural-Urban Adolescents in China: A Moderated Moderated-Mediation Model.” Youth & Society 55 (4): 686–707. https://doi.org/10.1177/0044118X221126548.

- Chu, X., Y. Chen, A. Litifu, Y. Zhou, X. Xie, X. Wei, and L. Lei. 2024. “Social Anxiety and Phubbing: The Mediating Role of Problematic Social Networking and the Moderating Role of Family Socioeconomic Status.” Psychology in the Schools 61 (2): 553–567. https://doi.org/10.1002/pits.23067.

- Chu, X., S. Ji, X. Wang, J. Yu, Y. Chen, and L. Lei. 2021. “Peer Phubbing and Social Networking Site Addiction: The Mediating Role of Social Anxiety and the Moderating Role of Family Financial Difficulty.” Frontiers in Psychology 12: Article 670065. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.670065.

- Coduto, K. D., R. J. Lee-Won, and Y. M. Baek. 2019. “Swiping for Trouble: Problematic Dating Application use among Psychosocially Distraught Individuals and the Paths to Negative Outcomes.” Journal of Social and Personal Relationships 37 (1): 212–232. https://doi.org/10.1177/0265407519861153.

- Cooper, M. L. 1994. “Motivations for Alcohol use among Adolescents: Development and Validation of a Four-Factor Model.” Psychological Assessment 6 (2): 117–128. https://doi.org/10.1037/1040-3590.6.2.117.

- Cooper, M. L., E. Kuntsche, A. Levitt, L. L. Barber, and S. Wolf. 2016. “Motivational Models of Substance use: A Review of Theory and Research on Motives for Using Alcohol, Marijuana, and Tobacco.” In The Oxford Handbook of Substance Use Disorder. Vol. 1, edited by K. J. Sher, 375–421. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199381678.013.017.

- Cox, W. M., and E. Klinger. 1988. “A Motivational Model of Alcohol use.” Journal of Abnormal Psychology 97 (2): 168–180. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-843X.97.2.168.

- Eichenberg, C., M. Schott, and A. Schroiff. 2019. “Comparison of Students with and Without Problematic Smartphone use in Light of Attachment Style.” Frontiers in Psychiatry 10. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2019.00681.

- Elhai, J. D., M. Tiamiyu, and J. Weeks. 2018. “Depression and Social Anxiety in Relation to Problematic Smartphone use.” Internet Research 28 (2): 315–332. https://doi.org/10.1108/IntR-01-2017-0019.

- Elhai, J. D., Yang, H., Dempsey, A. E., & Montag, C. 2020. “Rumination and Negative Smartphone use Expectancies are Associated with Greater Levels of Problematic Smartphone use: A Latent Class Analysis.” Psychiatry Research, 285: Article 112845. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2020.112845

- Elhai, J. D., H. Yang, and J. C. Levine. 2021. “Applying Fairness in Labeling Various Types of Internet use Disorders.” Journal of Behavioral Addictions 9 (4): 924–927. https://doi.org/10.1556/2006.2020.00071.

- Elhai, J. D., H. Yang, and C. Montag. 2019. “Cognitive- and Emotion-Related Dysfunctional Coping Processes: Transdiagnostic Mechanisms Explaining Depression and Anxiety’s Relations with Problematic Smartphone Use.” Current Addiction Reports 6 (4): 410–417. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40429-019-00260-4.

- Ericsson. 2023. Number of smartphone mobile network subscriptions worldwide from 2016 to 2022, with forecasts from 2023 to 2028 (in millions) [Graph]. In Statista. Accessed March 1, 2024, from https://www.statista.com/statistics/330695/number-of-smartphone-users-worldwide/.

- Fullwood, C., S. Quinn, L. K. Kaye, and C. Redding. 2017. “My Virtual Friend: A Qualitative Analysis of the Attitudes and Experiences of Smartphone Users: Implications for Smartphone Attachment.” Computers in Human Behavior 75:347–355. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2017.05.029.

- George, A. M., P. M. Brown, B. Scholz, B. Scott-Parker, and D. Rickwood. 2018a. “I Need to Skip a Song Because it Sucks”: Exploring Mobile Phone use While Driving among Young Adults.” Transportation Research Part F: Traffic Psychology and Behaviour 58: 382–391. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.trf.2018.06.014.

- George, A. M., B. L. Zamboanga, J. L. Martin, and J. V. Olthuis. 2018b. “Examining the Factor Structure of the Motives for Playing Drinking Games Measure among Australian University Students.” Drug and Alcohol Review 37 (6): 782–788. https://doi.org/10.1111/dar.12830.

- Golubchik, P., I. Manor, G. Shoval, and A. Weizman. 2020. “Levels of Proneness to Boredom in Children with Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder on and off Methylphenidate Treatment.” Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychopharmacology 30 (3): 173–176. https://doi.org/10.1089/cap.2019.0151.

- Greenberg, B. S. 1974. “Gratifications of Television Viewing and Their Correlates for British Children.” In The Uses of Mass Communications: Current Perspectives on Gratifications Research, edited by J. G. Blumler, and E. Katz, 71–92. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage.

- Griffiths, M. 2005. “A ‘Components’ Model of Addiction Within a Biopsychosocial Framework.” Journal of Substance Use 10 (4): 191–197. https://doi.org/10.1080/14659890500114359.

- Harkin, L. J., and D. Kuss. 2021. “My Smartphone is an Extension of Myself”: A Holistic Qualitative Exploration of the Impact of Using a Smartphone.” Psychology of Popular Media 10 (1): 28–38. https://doi.org/10.1037/ppm0000278.

- James, R. J. E., G. Dixon, M.-G. Dragomir, E. Thirlwell, and L. Hitcham. 2023. “Understanding the Construction of ‘Behavior’ in Smartphone Addiction: A Scoping Review.” Addictive Behaviors 137: Article 107503. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2022.107503.

- Joinson, A. N. 2008. “Looking at, looking up or keeping up with people? Motives and use of Facebook.” Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, Florence, Italy, 1027-1036. https://doi.org/10.1145/1357054.1357213

- Karaoglan Yilmaz, F. G., A. B. Ustun, K. Zhang, and R. Yilmaz. 2023. “Smartphone Addiction, Nomophobia, Depression, and Social Appearance Anxiety among College Students: A Correlational Study.” Journal of Rational-Emotive & Cognitive-Behavior Therapy 42: 305–321. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10942-023-00516-z.

- Kardefelt-Winther, D. 2014. “A Conceptual and Methodological Critique of Internet Addiction Research: Towards a Model of Compensatory Internet use.” Computers in Human Behavior 31: 351–354. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2013.10.059.

- Katz, E., J. G. Blumler, and M. Gurevitch. 1974. “Utilization of Mass Communication by the Individual.” In The Uses of Mass Communications: Current Perspectives on Gratifications Research, edited by J. G. Blumler, and E. Katz, 19–32. Beverly Hills, CA: Sage.

- Kim, J.-H. 2017. “Smartphone-mediated Communication vs. Face-to-Face Interaction: Two Routes to Social Support and Problematic use of Smartphone.” Computers in Human Behavior 67: 282–291. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2016.11.004.

- Kim, J.-H. 2018. “Psychological Issues and Problematic use of Smartphone: ADHD's Moderating Role in the Associations among Loneliness, Need for Social Assurance, Need for Immediate Connection, and Problematic use of Smartphone.” Computers in Human Behavior 80: 390–398. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2017.11.025.

- Kim, J.-H., M. Seo, and P. David. 2015. “Alleviating Depression Only to Become Problematic Mobile Phone Users: Can Face-to-Face Communication be the Antidote?” Computers in Human Behavior 51: 440–447. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2015.05.030.

- Kuss, D., Harkin, L., Kanjo, E., & Billieux, J. 2018. Problematic Smartphone use: Investigating Contemporary Experiences Using a Convergent Design. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 15(1), Article 142. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph15010142

- Lavoie, R., and Y. Zheng. 2023. “Smartphone use, Flow and Wellbeing: A Case of Jekyll and Hyde.” Computers in Human Behavior 138: Article 107442. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2022.107442.

- Lee, C., and S.-J. Lee. 2017. “Prevalence and Predictors of Smartphone Addiction Proneness among Korean Adolescents.” Children and Youth Services Review 77: 10–17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2017.04.002.

- Lepp, A., J. E. Barkley, and J. Li. 2017. “Motivations and Experiential Outcomes Associated with Leisure Time Cell Phone use: Results from two Independent Studies.” Leisure Sciences 39 (2): 144–162. https://doi.org/10.1080/01490400.2016.1160807.

- Lin, Y. H., C.-H. Fang, and C. L. Hsu. 2014. “Determining Uses and Gratifications for Mobile Phone Apps.” Lecture Notes in Electrical Engineering 309: 661–668. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-55038-6_103.

- Lopez-Fernandez, O., D. J. Kuss, H. M. Pontes, M. D. Griffiths, C. Dawes, L. V. Justice, N. Männikkö, … J. Billieux. 2018. “Measurement Invariance of the Short Version of the Problematic Mobile Phone use Questionnaire (PMPUQ-SV) Across Eight Languages.” International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 15 (6): Article 1213. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph15061213.

- Maftei, A., C. Opariuc-Dan, and A. N. Grigore. 2024. “Toxic Sensation Seeking? Psychological Distress, Cyberbullying, and the Moderating Effect of Online Disinhibition among Adults.” Scandinavian Journal of Psychology 65 (1): 61–69. https://doi.org/10.1111/sjop.12956.

- Malkovsky, E., C. Merrifield, Y. Goldberg, and J. Danckert. 2012. “Exploring the Relationship Between Boredom and Sustained Attention.” Experimental Brain Research 221 (1): 59–67. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00221-012-3147-z.

- Montag, C., E. Wegmann, R. Sariyska, Z. Demetrovics, and M. Brand. 2021. “How to Overcome Taxonomical Problems in the Study of Internet use Disorders and What to do with “Smartphone Addiction”?” Journal of Behavioral Addictions 9 (4): 908–914. https://doi.org/10.1556/2006.8.2019.59.

- Moon, J.-W., and Y. An. 2022. “Scale Construction and Validation of Uses and Gratifications Motivations for Smartphone use by Tourists: A Multilevel Approach.” Tourism and Hospitality 3 (1): 100–113. https://doi.org/10.3390/tourhosp3010007.

- Mostyn Sullivan, B., & George, A. M. 2023. “The Association of Motives with Problematic Smartphone use: A Systematic Review.” Cyberpsychology: Journal of Psychosocial Research on Cyberspace, 17(1): Article 2. https://doi.org/10.5817/CP2023-1-2

- Nabilla, S. P., Christia, M., & Dannisworo, C. A. 2019. “The relationship between boredom proneness and sensation seeking among adolescent and adult former drug users.” Proceedings of the 2nd International Conference on Intervention and Applied Psychology (ICIAP 2018). https://doi.org/10.2991/iciap-18.2019.35

- Ochs, C., and J. Sauer. 2022. “Disturbing Aspects of Smartphone Usage: A Qualitative Analysis.” Behaviour & Information Technology 42 (14): 2504–2519. https://doi.org/10.1080/0144929x.2022.2129092.

- Panova, T., X. Carbonell, A. Chamarro, and D. X. Puerta-Cortés. 2020. “Specific Smartphone Uses and how They Relate to Anxiety and Depression in University Students: A Cross-Cultural Perspective.” Behaviour & Information Technology 39 (9): 944–956. https://doi.org/10.1080/0144929x.2019.1633405.

- Parent, N., T. A. Bond, and J. D. Shapka. 2023. “Smartphones as Attachment Targets: An Attachment Theory Framework for Understanding Problematic Smartphone use.” Current Psychology 42 (9): 7567–7578. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-021-02092-w.

- Rubin, A. M. 1981. “An Examination of Television Viewing Motivations.” Communication Research 8 (2): 141–165. https://doi.org/10.1177/009365028100800201.

- Rubin, A. M. 2002. “The Uses-and-Gratifications Perspective of Media Effects.” In LEA's Communication Series. Media Effects: Advances in Theory and Research, edited by J. Bryant, and D. Zillmann, 525–548. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers.

- Shen, X., H.-Z. Wang, D. H. Rost, J. Gaskin, and J.-L. Wang. 2021. “State Anxiety Moderates the Association Between Motivations and Excessive Smartphone use.” Current Psychology 40: 1937–1945. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-019-0127-5.

- Sherry, J. L., K. Lucas, B. S. Greenberg, and K. Lachlan. 2006. “Video Game Uses and Gratifications as Predicators of use and Game Preference.” In Playing Video Games: Motives, Responses, and Consequences, edited by P. Vorderer, and J. Bryant, 213–224. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers.

- Sun, J., and C. H. Miller. 2023. “Insecure Attachment Styles and Phubbing: The Mediating Role of Problematic Smartphone Use.” Human Behavior and Emerging Technologies 2023, Article 4331787. https://doi.org/10.1155/2023/4331787.

- Sundar, S. S., and A. M. Limperos. 2013. “Uses and Grats 2.0: New Gratifications for new Media.” Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media 57 (4): 504–525. https://doi.org/10.1080/08838151.2013.845827.

- Tanrikulu, I., and Ö Erdur-Baker. 2021. “Motives Behind Cyberbullying Perpetration: A Test of Uses and Gratifications Theory.” Journal of Interpersonal Violence 36 (13-14): NP6699–NP6724. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260518819882.

- Tirado-Morueta, R., A. García-Umaña, and S. Mengual-Andrés. 2021. “Validating the Gratifications Associated with the use of the Smartphone and the Internet by University Students in Chile, Ecuador and Spain.” Journal of Intercultural Communication Research 50 (4): 371–388. https://doi.org/10.1080/17475759.2021.1898449.

- Tong, A., P. Sainsbury, and J. Craig. 2007. “Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research (COREQ): A 32-Item Checklist for Interviews and Focus Groups.” International Journal for Quality in Health Care 19 (6): 349–357. https://doi.org/10.1093/intqhc/mzm042.

- Vanden Abeele, M. M. 2016. “Mobile Lifestyles: Conceptualizing Heterogeneity in Mobile Youth Culture.” New Media & Society 18 (6): 908–926. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444814551349.

- Vera Cruz, G., E. Aboujaoude, L. Rochat, F. Bianchi-Demicheli, and Y. Khazaal. 2024. “Online Dating: Predictors of Problematic Tinder use.” BMC Psychology 12 (1): 106. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40359-024-01566-3.

- Vezzoli, M., C. Zogmaister, and S. Coen. 2021. “Love, Desire, and Problematic Behaviors: Exploring Young Adults’ Smartphone use from a Uses and Gratifications Perspective.” Psychology of Popular Media 12 (1): 50–57. https://doi.org/10.1037/ppm0000375.

- Wang, J.-L., L. A. Jackson, H.-Z. Wang, and J. Gaskin. 2015. “Predicting Social Networking Site (SNS) use: Personality, Attitudes, Motivation and Internet Self-Efficacy.” Personality and Individual Differences 80: 119–124. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2015.02.016.

- Wang, X., S. Wang, and X. Zeng. 2023. “Does Sensation Seeking Lead to Adolescents’ Cyberbullying Perpetration? The Mediating Role of Moral Disengagement and the Moderating Role of Perceived Social Support.” Child Psychiatry & Human Development. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10578-023-01527-8.

- Wei, X.-Y., L. Ren, H.-B. Jiang, C. Liu, H.-X. Wang, J.-Y. Geng, T. Gao, J. Wang, and L. Lei. 2023. “Does Adolescents’ Social Anxiety Trigger Problematic Smartphone use, or Vice Versa? A Comparison Between Problematic and Unproblematic Smartphone Users.” Computers in Human Behavior 140: Article 107602. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2022.107602.

- Whiteside, S. P., and D. R. Lynam. 2001. “The Five Factor Model and Impulsivity: Using a Structural Model of Personality to Understand Impulsivity.” Personality and Individual Differences 30 (4): 669–689. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0191-8869(00)00064-7.

- World Health Organization. 2018. International Classification of Diseases for Mortality and Morbidity Statistics (11th Revision). https://icd.who.int/browse11/l-m/en.

- Yang, Z., K. Asbury, and M. D. Griffiths. 2019. “A Cancer in the Minds of Youth?”: A Qualitative Study of Problematic Smartphone use among Undergraduate Students.” International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction 19: 934–946. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-019-00204-z.

- Yilmaz, R., S. Sulak, M. D. Griffiths, and F. G. K. Yilmaz. 2023. “An Exploratory Examination of the Relationship Between Internet Gaming Disorder, Smartphone Addiction, Social Appearance Anxiety and Aggression among Undergraduate Students.” Journal of Affective Disorders Reports 11: Article 100483. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jadr.2023.100483.

- Yu, S., & Sussman, S. 2020. “Does Smartphone Addiction Fall on a Continuum of Addictive Behaviors?” International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(2): Article 422. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17020422.

- Zhang, K. Z., C. Chen, and M. K. Lee. 2014. "Understanding the role of motives in smartphone addiction." Proceedings for the Pacific Asia Conference on Information Systems, 131. https://aisel.aisnet.org/pacis2014/131.

- Zhang, X.-C., Chu, X.-W., Fan, C.-Y., Andrasik, F., Shi, H.-F., & Hu, X.-E. (2022). “Sensation Seeking and Cyberbullying among Chinese Adolescents: Examining the Mediating Roles of Boredom Experience and Antisocial Media Exposure.” Computers in Human Behavior 130, Article 107185. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2022.107185.

- Zhang, M. X., and A. M. S. Wu. 2022. “Effects of Childhood Adversity on Smartphone Addiction: The Multiple Mediation of Life History Strategies and Smartphone use Motivations.” Computers in Human Behavior 134: Article 107298. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2022.107298.