Abstract

Long-term behavioral change is often difficult to achieve with adolescents staying in residential youth care. To achieve long-term behavioral change, we developed the Up2U training program to enhance these adolescents’ intrinsic motivation for change. Based on motivational interviewing and solution-focused therapy, Up2U is designed for conducting one-on-one conversations with adolescents in residential youth care. The aim of this study is to evaluate the experiences that adolescents and care workers have had with Up2U. The results of semi-structured interviews show that, in general, the care workers were satisfied with Up2U. They identified the clarity, conciseness, and sample questions as positive elements of Up2U. In contrast, the care workers regarded the extensiveness and the implementation of Up2U as less positive. The adolescents also seemed to be positive about the use of Up2U during one-on-one conversations. In conclusion, although both care workers and adolescents were generally satisfied, there is still room for improvement.

Introduction

Adolescents in residential youth care regularly experience difficulties in relationships with peers. Many have cognitive problems, and they tend to exhibit emotional and behavioral problems (Leloux-Opmeer et al., Citation2016). These problems generally manifest themselves in the form of externalizing behavior, which includes both aggression (e.g., use of violence and bullying) and delinquent behavior (e.g., stealing and vandalism; De Haan et al., Citation2012; Prinzie et al., Citation2006; Stanger et al., Citation1997). In one study, Connor et al. (Citation2004) report that a large majority of some 400 youths in a residential treatment center in the United States had been diagnosed with at least two psychiatric disorders (92%). The most common diagnoses were disruptive behavior disorder (49%), followed by anxiety or affective disorders (31%) and psychotic disorders (12%). In addition, the majority of the young people (58%) had been classified as aggressive.

Adolescents in residential youth care often have a long history of care (Leloux-Opmeer et al., Citation2016). Negative experiences in youth care can cause negativity about the contact with and lack of confidence in care providers. Negative care experiences (e.g., low trust in care providers by youth and parents) are related to poorer results (Barnhoorn et al., Citation2013). In addition, young people in residential youth care are often poorly motivated for treatment (Englebrecht et al., Citation2008; Van Binsbergen et al., Citation2001). Autonomy is an important factor in strengthening adolescents’ motivation for treatment (Brauers et al., Citation2016). Autonomy and independence are also important developmental tasks during adolescence (Feldstein & Ginsburg, Citation2006; Naar-King & Suarez, Citation2011). The development of autonomy often poses a challenge, however, especially within secure residential youth care facilities (Bramsen et al., Citation2019). This is due in part to the residential setting—in which boundaries are the order of the day—as well as to the ways in which care workers regard the cooperation of young people in the care process (Ten Brummelaar et al., Citation2018). According to a study by Ten Brummelaar et al. (Citation2018), cooperation in the care process can increase the autonomy of youth. In contrast, refusal to cooperate can lead to less autonomy. Care workers can thus use autonomy as an extrinsic reward for achieving desired behavioral changes.

Given the problems of the adolescents who are treated there, working within residential youth care facilities can be challenging for professionals, particularly for those providing residential group care. Especially in secure residential youth care facilities, group care workers experience high levels of violence from the adolescents with whom they work, with verbal threats being the most common form (Alink et al., Citation2014). In a more recent study on the history of violence in residential youth care in the Netherlands, Exalto et al. (Citation2019) report that physical violence continues to occur within the residential youth care sector. According to incident and calamity records, violence (e.g. kicking, hitting, intimidating, and threatening) is perpetrated primarily by youth and aimed predominantly at group care workers.

Steinlin et al. (Citation2017) report that 83% of the 319 residential care workers in their study had experienced serious physical assault or threatening situations during their work. For half of these care workers, these incidents had caused feelings of fear, shock, or helplessness. In addition, one fifth reported post-traumatic stress symptoms. It is therefore not surprising that burnout is a common problem among residential youth care workers (Colton & Roberts, Citation2007; Connor et al., Citation2003; Seti, Citation2008), and this phenomenon is associated with a high staff turnover in residential youth care (Maslach et al., Citation2001).

In many cases, residential care workers apply a controlling approach in order to address problematic behavior on the part of adolescents (Bastiaanssen et al., Citation2012; De Valk, Citation2019; Van Dam et al., Citation2011; Wigboldus, Citation2002). In this approach, the young person’s behavior is structured (e.g., by rules and clear instructions). Although care workers often adopt this approach with the intent of reducing behavioral problems, it has actually been associated with an increase in externalizing behavior problems (Bastiaanssen et al., Citation2014).

Another approach to achieving behavior change with adolescents in residential youth care facilities involves the use of external rewards (Bartels, Citation2001; Gilman & Anderman, Citation2006; Ryan & Deci, Citation2000). Although such rewards can lead adolescents to exhibit socially desirable behavior during care (Ryan & Deci, Citation2000), they do not necessarily result in long-term behavioral change after care (cf. Colson et al., Citation1991; Kromhout, Citation2002).

Intrinsic motivation seems to be a better approach for achieving long-term treatment success with regard to behavioral change for clients (e.g., Harder, Citation2011). Intrinsically motivated individuals do not act based on external rewards but on inherent satisfaction (Ryan & Deci, Citation2000). It is assumed that people who are intrinsically motivated to change will be more actively involved in treatment aimed at actually achieving change (Deci & Ryan, Citation2002). Such a situation is also more likely to result in long-term behavioral change than a situation in which motivation is driven by external stimuli (Teixeira et al., Citation2012).

Long-term treatment success is, however, difficult to achieve with residential youth care. Although youth generally show positive behavioral changes during residential care, these are often difficult to maintain after departure (Knorth et al., Citation2008). These difficulties to achieve enduring change can be explained by the difficult target group on the on hand and the difficulties for care workers to treat the target group on the other hand (Harder, Citation2018). However, there are no tools specifically designed and tested for residential care workers to deal with the complex target group, i.e. to increase young people’s intrinsic motivation for change and to create or improve a therapeutic alliance with them.

Therefore, we developed the Up2U training program with and for care workers and adolescents in residential youth care (Harder & Eenshuistra, Citation2017). The program focuses on one-on-one conversations between group care workers (mentors) and adolescents. The mentor is involved in the adolescent’s individual treatment planning and is the most important group care worker for the adolescent during his/her stay in care. Given the important role of the mentor for the adolescent, we chose to focus in our research on the conversations that adolescents have with their mentor. The program involves teaching care workers techniques for enhancing intrinsic motivation for change in adolescents, in addition to increasing their own professional skills.

The Up2U program is based on motivational interviewing (MI) and, to a lesser extent, on solution-focused therapy (SFT). MI is defined as a “collaborative conversation style for strengthening a person’s own motivation and commitment to change” (Miller & Rollnick, Citation2013, p. 12). When applying MI, care workers use communication strategies that are well-suited to adolescents in residential care, who are often in need of autonomy and recognition. The interpersonal skills of professionals—showing commitment and care, empathy, warmth and friendliness, reliability and transparency, and an unbiased and respectful attitude—play a central role in MI (Miller & Rollnick, Citation2013).

There are several reasons for choosing MI as basic treatment approach for the Up2U program. First, MI is an evidence-based treatment approach with much empirical support for being effective in promoting client behavior change across a range of health arenas, including a reduction in risk behaviors often shown by youth in residential care such as substance use (e.g. Jensen et al., Citation2011). Second, MI is very suited for youth in residential care, because this group mainly consists of adolescents. MI focuses on autonomy support and therefore fits very well with the developmental period of adolescence in which autonomy is important (e.g. Naar-King & Suarez, Citation2011). Third, MI is specifically aimed at positive communication strategies of professionals to establish a good therapeutic relationship with clients (Miller & Rollnick, Citation2013), which can be difficult to achieve in residential youth care.

Studies have indicated that good communication skills on the part of professionals are related to good alliances (Baldwin et al., Citation2007; Harder et al., Citation2013) and are predictive of the degree of client involvement during care (Moyers et al., Citation2005). The application of MI has been associated with lower client drop-out rates (cf. Burke et al., Citation2003) and greater effectiveness (including cost-effectiveness) of treatment (Jensen et al., Citation2011), both of which constitute major concerns in residential care (Harder et al., Citation2006). Despite its evidence-based character and inherent suitability for the target group, MI has not been the subject of much investigation within the context of residential youth care (Harder, Citation2018).

SFT is a closely related intervention to MI and a form of psychotherapy that concentrates on the autonomy of clients. Instead of the problem, the solution to the problem is the main focus during treatment (Bakker & Bannink, Citation2008; Bannink, Citation2007). When applying SFT, therapists encourage their clients to imagine a future in which the problem is no longer present and to focus on components of the solution that already exist. The idea is to do more of the things that are already working (thus corresponding to the principles of “what works”). If something is not working, the client is encouraged to do “something different” (Quick & Gizzo, Citation2007). From the perspective of SFT, the client is the expert. The therapist adopts a non-knowing attitude, seeking to be informed by the client. Another attitude that therapists adopt in SFT is that of “leading from one step behind.” In doing so, therapists ask solution-oriented questions, encouraging clients to determine their own goals and to anticipate a range of their own possibilities for achieving these goals (Bakker & Bannink, Citation2008). Although SFT is generally a form of short-term therapy, the number of therapy sessions is not fixed (Quick & Gizzo, Citation2007). Studies into the effects of SFT have generally concluded that SFT yields positive treatment effects (Bartelink, Citation2011). For example, Kim (Citation2008) reports that the method produced significant effects for internalizing problems.

To investigate how Up2U is experienced in practice and to be able to improve the manual, in this study we will evaluate the implementation and experiences of adolescents and care workers with the new training program Up2U (Harder & Eenshuistra, Citation2017; more information is available on request). We conduct a qualitative process evaluation study with feedback from the users, i.e. care workers and youth, to examine whether the program is being implemented as intended, barriers that have been encountered and to assess what changes to the program and its implementation are needed. To investigate the experiences that residential care workers and adolescents have had with Up2U, we focus on the following questions:

What are the experiences of residential care workers with the Up2U program, including its implementation during one-on-one conversations with adolescents mentored by them?

What are the experiences of adolescents regarding one-on-one conversations with their mentor conducted according to the Up2U program?

Method

Program description

The Up2U program focuses on one-on-one conversations between residential care workers and adolescents in care. It consists of a three-day training course in MI, a program manual, and a program workshop.

The training sessions were conducted by a trainer from MINTned, the Dutch association of MI trainers. The following topics were discussed during the training course: Reasons why people change, ambivalence, intrinsic motivation, phases of behavioral change according to Prochaska and DiClemente (Citation1982), the four processes within MI (engage, focus, evoke, and plan), empathy, basic conversation techniques (open questions, reflective listening, giving information and advice, confirming and summarizing), resistance and the MITI (behavioral counts and global markers). The course also included several assignments geared to practicing MI skills in class along with the option of receiving individual coaching three times. The offer of individual coaching was meant to ensure that MI was being implemented. Coaching consisted of targeted feedback from the MI trainer using an audio recording of a one-on-one conversation with an adolescent, which the residential care workers submitted and which was aimed at further developing their MI skills.

Residential care professionals can use the Up2U manual as a guide for individual conversations with adolescents. The manual is introduced during a 4-h workshop for care workers, during which they complete assignments to become further acquainted with the manual. Drawing heavily on MI, the manual helps residential care workers to learn conversational techniques aimed at encouraging motivation for behavioral change. In addition to MI, the manual also draws on techniques from SFT, examples include the use of scale questions and solution-focused questions.

The Up2U manual (48 pages) consists of four chapters and several appendices. The first chapter consists of information about the background and goals of Up2U. The second chapter contains general information about MI, including a quiz. The third chapter focuses on becoming acquainted with the adolescent offering three tools to this end: (1) questions for asking adolescents about their background and interests, (2) questions for eliciting their opinions about their stay in the institution, and (3) a list of activities (Interest Check) to assess what is important to the adolescents (e.g., parents, friends, school). Chapter 3 also contains sample questions that care workers can ask young people when starting and ending an initial conversation.

Chapter 4 addresses issues of what, why, and how to change. The chapter centers on creating the Up2U change plan by the care worker together with the adolescent, which is an important aim of the Up2U program. Achieving the Up2U change plan consists of applying five steps during one-on-one conversations with youth. These five steps address the following questions, which are discussed during one-on-one conversations: (1) What does the adolescent want to change? (2) Why does the adolescent want to change? (3) Why does the adolescent want to change now? (4) What skills does the adolescent have in order to realize change? And (5) How can the adolescent change? The duration of the Up2U program depends on the care worker and adolescent, but given the different steps in the program, the duration is around six weeks.

The appendices consist of a variety of checklists and forms, including the Interest Check questionnaire; a short version of the Client Motivation for Therapy Scale (Pelletier et al., Citation1997), which includes six statements about the reason for placement according to the adolescent; and the Good Treatment Goals Checklist, which includes information about working with the adolescent to formulate SMART treatment goals. The appendices also include a decision-making balance. As a part of Step 2 in the Up2U change plan, this tool consists of an overview of the advantages and disadvantages of a current situation and of changing a situation in the future. Other resources provided in the appendices include concrete tips (do’s and don’ts) for care workers, including questions that they could better ask or not ask adolescents and examples of how to respond to adolescents with a “negative” attitude. The resources also include concrete tips for devoting positive attention to and emphasizing the adolescent’s autonomy. Finally, the manual addresses how to give advice suited to the needs of adolescents. For example, it includes several information sheets containing research-based information about delinquent behavior, substance use, and going to school/work (and the consequences of these situations), which care workers can share with adolescents in order to offer them new thoughts or ideas.

Procedure

This study is conducted according to guiding ethical principles for researchers. Participation in this study was voluntary, and all participants were informed in advance about the purpose of the study and how the data would be used. They were registered for the study by a supervisor of the facility. Data from the participants were treated with care and processed anonymously. Each of the adolescents signed a form consenting to participation in the research.

This study is part of a larger study consisting of several sub-studies. First, the needs of the adolescents and care workers regarding the one-on-one conversations they have with each other during residential care were outlined through semi-structured interviews. Then, we conducted a baseline measurement of the observed interactions between adolescents and care workers during their one-on-one conversations from an MI perspective. Thereafter, we investigated whether there is a difference in care workers’ performance vis-à-vis adolescents before and after the Up2U program. To measure this difference, we coded transcripts of audio recordings of one-on-one conversations between adolescents and workers, using the Motivational Interviewing Treatment Integrity (MITI) 4.2.1 and Motivational Interviewing Skills Code (MISC) 2.5. We compared the transcripts made before the MI training course with the transcripts made after the training course. At last, we evaluated the experiences of adolescents and care workers with the new Up2U program through interviews (the current study). The interviews were held with the residential care workers who recorded both one-on-one conversations, in order to evaluate the conversations and the Up2U program. The main researcher and two Master’s students conducted these interviews between October and December 2016.

The adolescents with whom the residential care workers recorded the conversations were also interviewed about their experiences. The interviews with the adolescents were conducted by the main researcher, a student-assistant, and two Master’s students between October 2016 and February 2017.

Setting

We conducted the interviews in three locations of a residential youth care facility in the northern region of the Netherlands. This facility provides residential care to young people who cannot stay at home or in a foster family. Two of the participating locations provide independence training for adolescents between the ages of 12 and 18 years. The other location offers both compulsory and voluntary treatment to young people between the ages of 12 and 18 years with behavioral and psychiatric problems. Three of the living groups at this third location were involved in the study. Within the facilities, adolescents are assigned to mentors, who serve as the primary contacts for the adolescents and their networks. The mentor is one of the care workers at the residential group.

Participants

The sample consisted of 12 residential care workers, each of whom recorded two one-on-one conversations with adolescents of whom they are the mentor. One conversation was recorded before the introduction of the Up2U training program, and the other was recorded after completion of the program. The personal background characteristics of the residential care workers are presented in . One care worker recorded a one-on-one conversation with a family member instead of with an adolescent in residential care. Because this care worker did participate in the Up2U training course and worked with the Up2U manual, we decided to include the interview in the current sample. During the interview with this care worker, we did not ask questions about the recorded conversation.

Table 1. Characteristics care workers (N = 12).

The other participants in this study were nine adolescents who were staying in residential youth care and who had participated in at least the second one-on-one conversation. The personal background characteristics of these adolescents are presented in . Two of the adolescents had separate one-on-one conversations with two different residential care workers. These adolescents were interviewed twice about the recorded conversations, each time with regard to a conversation with a different care worker.

Table 2. Characteristics adolescents (N = 9).

Instruments

We used two versions of semi-structured evaluation interviews: one version for the residential care workers and one version for the adolescents. The main researcher, project manager, and a research-assistant developed both interviews specifically for this study.

Interview Evaluation of individual conversation in residential youth Care - Care workers’ version (IEIC-CW)

The IEIC-CW examines the experiences that residential care workers have had with the Up2U program. The care workers’ version consists of five sections, each addressing a different element: the Up2U instruction manual (20 questions), the recorded conversation (seven questions, nine statements), the Up2U workshop (four questions), the three-day MI training (three questions), and further comments (one question). The interview consisted of 31 open questions with the possibility of further questioning, one scale question, and the care workers were asked to assign three scores, i.e. rating the manual, the recorded conversation, and the MI training. For this study, we used the questions about the Up2U instruction manual and the recorded conversation, as this was our main interest. This information could be used to improve the Up2U manual.

Interview Evaluation of individual conversation in residential youth Care - Youth version (IEIC-Y)

The IEIC-Y examines the experiences that adolescents have had with the recorded one-on-one conversations. The semi-structured interview consists of 18 open questions with the possibility of further questioning, 1 closed question, and 12 statements. In addition, the adolescents were asked to assign two scores, rating the recorded conversation and previous conversations. The IEIC-Y consists of five sections, each addressing a different element: the one-on-one conversation in which residential care workers applied the Up2U program (seven questions); previous conversations between adolescents and professionals (six questions); comparison of the one-on-one conversations in which residential care workers applied the Up2U program and previous conversations (two questions and 12 statements); additional questions about the one-on-one conversation for adolescents who had not had any previous conversations with the professional (five questions); and further comments (one question). For this study, we used only the questions about the one-on-one conversation in which residential care workers applied the Up2U program. This is because, during the interviews, it became clear that many adolescents had not yet been in the residential facility when the care workers received their MI training. As a result, no comparison could be made with the conversations before and after the MI training.

Data analyses

In all, 23 interviews were transcribed and analyzed by the main researcher and two Master’s students using the ATLAS.ti program (Friese, Citation2012) and applying the “open coding” method. This qualitative research method is characterized by a holistic approach, in which information is collected and analyzed in an open and flexible way (Flick, Citation2014).

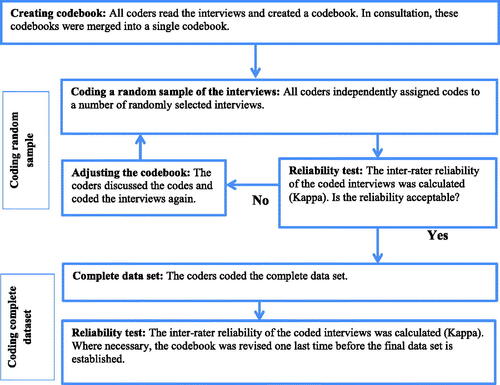

We calculated a coefficient of inter-rater reliability to reflect the extent of agreement between researchers (Hruschka et al., Citation2004). The coding process is shown in , which is based on the experiences gained during the coding process (as described in Hruschka et al., Citation2004). In developing the codebook, we attempted to stay as close as possible to the wording of the adolescents and residential care workers. As a measure of reliability, we decided in advance to require a Kappa value of at least 0.8, following the classification developed by Landis and Koch (Citation1977). The closed-ended questions from the interview were analyzed according to descriptive statistics, and averages were calculated.

We calculated the Kappa values for the care workers’ version of the IEIC three times. For the youth version, we calculated the Kappa values four times. The results are presented in .

Table 3. Kappa coding sessions.

First, we coded the interviews of the adolescents. In this session, we coded four interviews that had been selected at random using the Web site random.org. We then calculated the Kappa values, and the researchers made agreements about the coding and made changes to the codebook. We then coded and discussed another four randomly selected interviews. From the third session onwards, all interviews were coded. In the third session, the Kappa value was not yet sufficient, and agreements were made again and changes were made to the codebook. In the fourth session, a sufficient Kappa was achieved and a definitive dataset was established.

After the interviews with the adolescents, we coded the interviews of the residential care workers. During the first and second sessions, six interviews were selected at random (using random.org) for coding and discussion. After completing the first session, the Kappa value was insufficient, and agreements were made and changes were made to the codebook. In the second session, the remaining six interviews were coded. In that session, a lower Kappa value was obtained. One reason might have been that the answers given by these residential care workers were more detailed than those of the interviewees from the first session, given that more codes were identified during the second session. The results were discussed again, after which agreements and changes to the codebook were made. One of these agreements was to eliminate the following interview question from the further analysis: How many conversations have you had so far using the manual and what were these conversations about? The answers that the residential care workers gave to this question were highly diverse, with some professionals answering in detail and others only globally. In many cases, interviewees gave no answer at all. The quality of the research could therefore be enhanced by eliminating this question. In the third session, all of the interviews were coded and, in consultation, a definitive dataset was created.

Results

Experiences of residential care workers with Up2U

Some of the residential care workers who were interviewed identified the clarity and conciseness of the Up2U manual as positive elements (clarity was mentioned by five respondents and conciseness was mentioned by two). Three workers indicated that they had been able to use the Up2U manual as a support tool during the conversations. Other positive elements mentioned by care workers referred to specific parts of the manual, with four care workers mentioning the sample questions that could be asked during one-on-one conversations as positive. Two care workers identified the decision balance as a positive part of the manual. Other positive parts of the manual, each mentioned by one care worker, include the change plan, open questions, the scale question (concerning the extent to which a young person believed that the goal had already been achieved on a scale from 1 to 10), questionnaires, tips, and “do’s and don’ts.”

Almost half of the residential care workers (42%) indicated that they could not identify any negative aspects of the program. Two noted that, because they had not used the program in practice, they were not able to answer the question regarding negative aspects of the manual properly. Two interviewees mentioned that lack of time made the use of the program difficult.

One third of the care workers identified the extensiveness of the Up2U manual as a negative aspect of the program. Furthermore, one residential care worker mentioned that the program should be more “lively.” Other less positive elements regarding the manual (each mentioned by one care worker) included the observation that the sample questions were not effective for adolescents who truly did not wish to cooperate, the use of silences during the conversation, and doubts concerning the suitability of the program for the target group with which the respondent was working (i.e., adolescents in compulsory care).

Various components of the Up2U manual were identified as useful during one-on-one conversations by the residential care workers. The examples of questions in the Up2U manual were mentioned by three care workers. The components focusing on acquaintance with the young person, tips for concrete actions, making a change plan, the decision balance, probing questions, and open questions were all mentioned by two care workers. Positive questions, questionnaires, the scale question, reflective listening, and structure of the conversations were once mentioned as useful. One respondent reported not knowing what was useful, as a long time had elapsed between the use of the manual and the interview.

With regard to the decision balance, two respondents noted that it was not useful. Five of the participating residential care workers (42%) could not identify any elements of the program that were not useful, and two others mentioned that they did not consider any of the elements not useful for one-on-one conversations with youth. One respondent mentioned the information sheets as a less useful part of the manual.

On a scale from 1 to 10 (with a score of 1 being the worst and a score of 10 being the best), the residential care workers rated Up2U with an average score of 7.3 (SD = .65, range 7.0 to 9.0). Five respondents noted that some parts of the Up2U manual could be improved. Two mentioned that the manual should be shortened. Other improvements, each mentioned by one care worker, included making the manual “more lively,” making use of images, making references to videos (on YouTube), including examples from practice, providing tips for physical positioning during conversations, and explaining the theory used in the manual in greater detail. The other six care workers reported that they did not know of or could not identify any need for improvement. One care worker added that it would be helpful to organize an online refresher course.

Residential care workers: satisfaction with recorded conversation

When asked what they thought about the recorded conversations in which they had applied the Up2U program, eight of the care workers (72.7%) rated their recorded conversations as good, whereas two (18.2%) described them as nice and one (9.1%) said that the conversation was reasonable. Two workers identified the fact that the adolescent had more opportunities to talk as a positive point, and two remarked that they had asked the right questions during their conversations. Other positive points (each mentioned by one respondent) included that the care worker had used compliments during the conversation, that the adolescent had been able to keep up the conversation, that the care worker had demonstrated respect for the adolescent during the conversation, and that the conversation had been relaxed.

One respondent mentioned that the recorded conversation had been good because the adolescent had talked in terms of change. Another care worker reported having given the conversation a “different twist” by placing the adolescent more in charge of the solution to the problem than had been the case in previous conversations. On a scale from 1 to 10 (with a score of 1 being the worst and a score of 10 being the best), the residential care workers rated their recorded conversations with an average score of 6.8 (SD = 0.4, min = 6, max = 7).

When asked about the differences between the recorded conversations and the conversations that they had held before the training, four care workers (36.4%) indicated that the program had made them more aware of how they conduct conversations or about the questions that they had asked during the recorded conversation with the adolescent. Four residential care workers (36%) indicated that the conversation had been influenced by the fact that it was being recorded. These effects included the care workers not being themselves and not speaking as well, as compared to unrecorded conversations; being nervous due to the recording; being more reserved and being distracted by the recorder; the adolescent sharing less information with the care worker; and the conversation taking more time than usual. One respondent noted that the conversations were similar, regardless of whether they were being recorded. Furthermore, six care workers (54.5%) indicated that the contact with the adolescents during the recorded conversations had been different compared to previous conversations. The difference that the adolescent had more opportunities to express own ideas was mentioned twice. Other differences were that the adolescent shared more information, the conversation was more motivating, the care worker was more open to the adolescent, the conversation was more focused on the adolescent, the care worker talked less than in previous conversations and a stronger focus on the adolescent’s motivation, Another difference mentioned was that the conversation changed the power ratio between professional and adolescent: the care worker now focused less on telling the adolescent what should be done.

Two care workers reported that the conversations had been similar, and four could not identify aspects of the recorded conversations that were worse, relative to previous conversations (see ).

Table 4. Better and worse aspects of recorded conversation, as compared to previous conversations, according to residential care workers.

Care workers were asked to indicate the extent to which they agreed with specific statements about the recorded conversations, as compared to previous conversations. These results are presented in .

Table 5. Agreement of residential care workers with statements regarding recorded versus unrecorded (previous) conversations (N = 11).

Adolescents: satisfaction with the recorded conversation

The adolescents mentioned various aspects that they had liked (or disliked) about the recorded conversations. One positive aspect of the recorded conversations (mentioned by three adolescents) was that the mentor had asked good questions. Moreover, three adolescents were positive about the fact that the mentor had been a listening ear during the conversation, two adolescents noted that they had felt understood by the mentor, and two adolescents considered it positive that they had been allowed to make their own choices during the conversation. In addition, two adolescents reported that there had been opportunities for their own input during the conversation, two were positive about the fact that the mentor was looking for solutions during the conversation, and two appreciated the fact that the mentor had offered them assistance. Other positive aspects (each mentioned by one adolescent) included the use of probing questions, the fact that the mentor let the adolescent finish talking, the fact that there had been no silences in the conversation, a pleasant atmosphere during the conversation, the fact that the conversation had been good and useful, and the presence of the recording device. In addition, one adolescent mentioned having been at ease talking with the mentor due to the good relationship between them. One adolescent was not able to identify any positive aspects about the recorded conversation.

In contrast, two adolescents mentioned having difficulty carrying on conversations, because they did not like to talk. Another adolescent regarded the conversation topics as worse than those of previous conversations and that it had been difficult to talk about what the adolescent wanted. Other negative aspects about the conversation (each mentioned by one adolescent) were that the utility of the conversation was unclear and that the conversation had been too long. Six adolescents did not mention any negative aspects about the conversations, and another reported that the recorded conversation had been “normal.”

On a scale from 1 to 10, with a score of 1 being the worst and a score of 10 being the best, the adolescents rated the one-on-one conversation with an average score of 7.5 (SD = 1.54, range = 5-10). Seven adolescents rated the recorded conversation as good. Reasons for this rating included the fact that the conversation had not been boring, that it had been a serious and useful conversation, and that there had been a pleasant atmosphere during the conversation. One adolescent mentioned appreciating the fact that the conversation had been short.

Seven adolescents expressed several ideas for the further improvement of the one-on-one conversations. Two adolescents mentioned that the mentor should be less serious. Other improvement ideas were that the mentor should limit the number of probing questions, should do what the adolescent wants and should demonstrate interest in the adolescent. That a different topic should be addressed and that there should not be any silences during the conversation were also mentioned. One adolescent who mentioned that the mentor should use more probing questions noted that it would be good for the mentor to continue asking more questions about the situation: “Uhm, ask a little more about situations. He knew the situation and immediately asked for solutions, but should ask a little more about it.” One adolescent who wanted to use a mobile phone during the conversation explained, “For example, with my phone, that would be very nice. We are not allowed to have it here.” One adolescent did not know how the conversations could be improved, and three noted that there was no way that the mentor could have earned a higher rating for the conversation.

Residential care workers: implementation of Up2U

The residential care workers were divided concerning the extent to which they felt sufficiently equipped to apply the Up2U program. Five care workers (41.7%) felt sufficiently equipped, five did not, and two (16.7%) did not know whether they felt equipped. One care worker reported not having used the Up2U program. Two of the respondents noted that, because they had lost the manual, they either did not feel equipped or were not sure whether they were equipped to apply Up2U in practice. In addition, one worker mentioned not yet being completely comfortable with using the method. The same respondent and three others also mention that their knowledge of the method had subsided. Half of the workers called for more attention to the program. For example, they expressed that a refresher course at a later date or discussion of the method during team meetings could help them to apply the program in practice.

When asked how likely they would be to continue to use the program, five care workers (41%) said that they would “probably” do so, and one reported being “very likely” to continue using the UP2U program. Three care workers provided a neutral response (“not likely and not unlikely”). Two responded that they were “unlikely” to continue using the Up2U program, and one considered it “very unlikely.” Of the workers who indicated that they would probably not use the program, one considered the program too extensive. Several workers (33%) mentioned that greater attention should be devoted to the method, that they would like to practice it more, or that too little had been done with the program up to that point. In addition, three care workers noted that lack of time plays a role. One respondent referred to the fact that they were already required to use many other manuals, another care worker reported not using manuals in general, and one had lost the manual. Another worker did not expect to use the program in the future, as the use of a manual did not suit their style.

When asked whether they were satisfied with the implementation of the program, five care workers (41%) indicated that they were satisfied. Five others were not satisfied, and two (16%) did not know. The most commonly mentioned reason for not being satisfied was that the care worker, colleagues, and/or the facility had not done anything with the program (mentioned by five care workers). Three other respondents stated that greater attention should be devoted to the method, and two identified the fact that not all members of the team had received the program/training as having a negative effect on the implementation. Other reasons for not being satisfied (each mentioned by one care worker) were that the organization should do more regarding the implementation, that the manual had been located in an impractical place (thus making it less accessible), and that they were already required to use many other manuals. Reasons for being satisfied with the implementation included the fact that the care workers had been sufficiently involved in the implementation and that the training had been sufficient to allow them to work with the program (both reasons mentioned by the same care worker).

When asked how to ensure good implementation, eight respondents (67%) noted that greater attention should be given to the method. In addition, two care workers mentioned that the implementation of the Up2U program could be enhanced by training all members of the team in MI. Other ideas for enhancing implementation (each mentioned once) included the use of surveys for care workers concerning how and when they actually used Up2U, having the organization do more to encourage care workers to use the method, and making the use of the method compulsory. According to one respondent, the implementation of the program should be the responsibility of the workers themselves. One respondent thought that nothing could be done to ensure good implementation, and another did not know of anything that could be done to ensure a good implementation.

Discussion

The aim of our study was to evaluate the experiences of adolescents (N = 9) and residential care workers (N = 12) with the new Up2U training program, which is based on MI and, to a lesser extent, on SFT. The program is designed for conducting one-on-one conversations with adolescents in residential youth care, with the goal of increasing their intrinsic motivation to change their problematic behavior. Our results show that, in general, the care workers were satisfied with the program. On a scale of 1 (very poor) to 10 (very good), they rated it with an average score of 7.3. The recorded conversations using the Up2U program were also rated as sufficient. Elements of the Up2U manual that were identified as particularly positive included clarity, conciseness, and the sample questions that were provided. Almost half of the care workers indicated that they would (probably) continue to use Up2U in the future, thus reflecting a desire to change the ways in which they were currently conducting conversations with adolescents in residential care. Our previous research on MI skills acquired by care workers through the Up2U training program also indicated that care workers actually did apply MI skills significantly more often at the time of the post-training conversation than they had done before the training (Eenshuistra et al., Citation2020). This suggests that it is actually possible to change skills in practice.

In addition, we would like to note that the responsiveness and the enthusiasm of care workers regarding a methodology like MI probably will not only be based on the quality of the Up2U-training program, but also depends on their personal characteristics. For instance, Van der Ploeg (Citation2003) refers to an empirical study with residential care workers showing that they can be characterized as professionals by means of four basic dimensions, namely: (1) personal involvement (including empathy, understanding, authenticity, acceptance of other persons, critical on oneself, caring, flexible), (2) activity (active, willing to work, energetic, enthusiastic), (3) self-restraint (able to cope with provocations, carrying natural weight with others, self-discipline, patience), and (4) cheerfulness (optimism, sense of humor). Our hypothesis is that workers scoring high on the first dimension are most open for a methodology like MI; indeed, it appeals to aspects like empathy, acceptance, being self-critical, etc. Further research needs to be done to verify of falsify this assumption.

Next to personal characteristics of residential staff members it is important to know what vision or approach is promoted within the work environment regarding relating with or treating of young people in care. In this context an interesting study was done by Petrie et al. (Citation2006). According to them “… a key role for staff working with children in residential care is, or should be, supporting them through difficult events and processes. This is one function of care-giving” (p. 77). The London team examined in three countries—Denmark, England, and Germany—the way in which care-givers apply this responsibility in practice—in this case, the way in which they offer emotional support to children. Care workers (N = 137) were asked to reflect on the last time they had provided emotional support to a child. The responses have been compiled into three clusters, referred to as an “empathic approach,” a “discursive approach,” and an “organizational/procedural approach,” respectively. On average, the empathic approach—with the categories of “listening,” “naming feelings,” “cuddling,” and “companionship”—was more frequently applied than the discursive approach—with its categories of “discussing/talking,” “suggesting strategies,” and “attempting to persuade.” The organizational/procedural approach—for instance “referring to rules”—was applied least frequently. Interestingly, there was a significant difference between, especially, Denmark and England: the empathic approach was most prominent in Denmark (“listening” as first response: 97%) and least prominent in England (“listening” as first response: 39%). So, not only organizations but even countries seem to differ regarding their views on child care work. We hypothesize that a methodology like MI flourishes better in Danish then in English children’s homes. It would be interesting to investigate this issue in Dutch residential youth care settings.

The fact that not all participants of the Up2U-training course indicate that they will (continue to) apply MI in their practice, raises the question if the setting in which one works always matches with an intervention like MI. A qualitative study with recently graduated residential care workers in the Netherlands (Verhage, Citation2022) shows that

… participants reported that they experience insufficient time to build a bond with all individual clients in the work-setting. Likewise, high turnover rates, the deployment of temporary workers, and extensive lists of tasks hinder establishing good therapeutic relationships, which in turn also increases the workload. “You want to give the girls more attention than you can, which really adds to your stress levels.” (participant 11) (p. 81)

So, possibly, residential staff does not always experience enough room for having “quiet” MI-based conversations with youth, although being more focused on the management of critical processes and issues within the group (see also De Valk, Citation2019; Wigboldus, Citation2002). We need research to underpin this assumption.

The results regarding the implementation of Up2U suggest that there is still room for improvement. Almost half of the care workers indicated that they were not satisfied with the implementation of Up2U, repeatedly indicating that the organization/management should be more involved in the implementation of the training program. This corresponds to other findings in the literature indicating that implementation should be anchored in relevant organizational systems (e.g., protocols and policy), as well as in current daily practice (Forman, Citation2015; Horner et al., Citation2017). The role of managers also seems to be of great importance in this context. Providing a clear, well-defined strategy for handling problem behavior is important in achieving positive outcomes for young people (Hicks, Citation2008; Hicks et al., Citation2009). The Up2U program (and thus motivational interviewing) could be part of such a strategy.

The answers to the questions raised during the interviews further suggest that the Up2U program had not been thoroughly implemented. For example, when asked to identify the less positive elements of Up2U, respondents mentioned the use of silences during the conversation, and that the sample questions were not effective for adolescents who truly did not wish to cooperate. It is important to note here that the use of silences is not a specific part of the Up2U program and that the sample questions definitely can be used with young people who are “unmotivated.” The use of MI skills makes it possible for care workers to build positive treatment relationships with young people and increase their intrinsic motivation for change (Harder, Citation2011). One employee also mentioned that it would have been better to be more confrontational during the conversation with regard to the adolescent’s behavior during the conversation. Because confrontation is considered inconsistent with MI (Moyers et al., Citation2014), however, we had discouraged the use of confrontations during conversations. These examples thus suggest that the principles of MI were not yet completely clear to all care workers.

Limitations and strengths

One limitation of this study is its relatively small sample size, which could be attributed to a substantial drop-out rate in our study group. The results are therefore based on only one facility, and they cannot be generalized to care workers and adolescents beyond the sample addressed in the present study (Barker et al., Citation2015).

A second limitation is the possibility of social-desirability bias on the part of the care workers. A number of the care workers participating in this study indicated that they had not actually used the manual in practice (e.g., because they had lost it). We noticed that the care workers repeatedly referred to the same parts of the training program in their answers. This could have been because they remembered only these parts of the training program from the workshop about Up2U. If the professionals had used the manual more in practice, they might have provided more or different information.

One strength of our study relates to the level of agreement between the researchers. Enhancing inter-rater agreement reduces the likelihood of errors and bias during coding of the interviews (Hruschka et al., Citation2004). Another strength of this study has to do with its contributions to the development of the Up2U training program and to the evaluation of its implementation. It provides abundant information for improvement in practice and recommendations for future research.

Recommendations

Based on the results of this study, one recommendation for in practice is that greater attention should be devoted to the implementation process of the training program, especially by the organization. This was repeatedly mentioned by the care workers who participated in this study, and the literature has highlighted the important role of the organization in the implementation of interventions (Stals et al., Citation2009). In this regard, it is important for the management of the organization to support and facilitate the intervention by creating sufficient staff capacity. In addition, it is important for both managers and professionals to pursue a common goal and to monitor this process. Achieving such a goal requires conditions including funding, time, support, and expertise (Stals, Citation2012). Another effective way to enhance implementation could be to remind professionals of what they need to do (Stals, Citation2012). The importance of preparation time has also been stressed (James, Citation2017). Implementation efforts are impossible until a facility meets the criteria of “readiness” (e.g., having sufficient resources to implement the program). Staff stability is apparently another important factor determining the success of the implementation process (Aarons & Sawitzky, Citation2006; James, Citation2017). High staff turnover at a facility results in the loss of skills learned through training. A positive organizational climate and culture have been identified as important to reducing staff turnover (Aarons & Sawitzky, Citation2006), which is a well-known problem in residential youth care (Colton & Roberts, Citation2007; Connor et al., Citation2003). This problem is also reflected in our results. We therefore recommend addressing staff stability before attempting to implement any new program.

Given that the care workers participating in this study did not yet have knowledge of all of the principles of MI, we advise making Up2U a more intensive training program. Continued support enabling care workers to acquire the more complex MI skills appears to be particularly important in this regard (Miller et al., Citation2004). According to Schwalbe et al. (Citation2014), the proper implementation of MI skills requires at least three additional coaching sessions more than a period of six months following an MI workshop. We therefore recommend including individual coaching as an integral part of the training program.

One recommendation for further research involves the further development of the Up2U training program in response to the points for improvement mentioned by the care workers in this study. Although the conciseness has been mentioned as a positive part of Up2U, many care workers also suggest that the manual should be shortened. According these results, and in light of the fact that care workers are already likely to be using several manuals, it is likely that they have only limited time for actually using Up2U. Making the manual as brief as possible would probably make it easier to apply in practice. The addition of practice-based examples (e.g., through videos) could also contribute to facilitating the use of Up2U in practice.

Future investigations of this revised training program should also be conducted with a larger sample size, thereby enhancing the ability to generalize the results to a broader population (Baarda et al., Citation2012). A larger sample could also make it possible to conduct a randomized controlled trial (RCT), in which part of the research group does participate in the training program and part does not. This would enhance certainty concerning whether any changes in the observed behavior of the care workers can actually be attributed to the training program. It is therefore important to reexamine the experiences of care workers and adolescents, as well as the implementation and the effects of the program. Included in such a study should be relevant characteristics of participants (like personal involvement, activity, etc.), and the treatment visions and working conditions in the organization they have to deal with.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful for the collaboration with Jeugdhulp Friesland in this research. We especially would like to thank all of the residential care workers and adolescents who participated in this study.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Aarons, G. A., & Sawitzky, A. C. (2006). Organizational climate partially mediates the effect of culture on work attitudes and staff turnover in mental health services. Administration and Policy in Mental Health, 33(3), 289–301. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-006-0039-1

- Alink, L. R. A., Euser, S., Bakermans-Kranenburg, M., & Van IJzendoorn, M. H. (2014). A challenging job: Physical and sexual violence towards group workers in youth residential care. Child & Youth Care Forum, 43(2), 243–250. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10566-013-9236-8

- Baarda, B., Bakker, E., Hulst, M., Fischer, T., Julsing, M., Vianen, R., & De Goede, M. (2012). Basisboek methoden en technieken [Basic book of methods and techniques]. Noordhoff Publishers.

- Bakker, J. M., & Bannink, F. P. (2008). Oplossingsgerichte therapie in de psychiatrische praktijk [Solution-focused therapy in psychiatric practice]. Tijdschrift Voor Psychiatrie, 50(1), 55–59.

- Baldwin, S. A., Wampold, B. E., & Imel, Z. E. (2007). Untangling the alliance-outcome correlation: Exploring the relative importance of therapist and patient variability in the alliance. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 75(6), 842–852. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.75.6.842

- Bannink, F. P. (2007). Solution-focused brief therapy. Journal of Contemporary Psychotherapy, 37(2), 87–94. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10879-006-9040-y

- Barker, C., Pistrang, N., & Elliott, R. (2015). Research methods in clinical psychology: An introduction for students and practitioners. John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.

- Barnhoorn, J., Broeren, S., Distelbrink, M., De Greef, M., Van Grieken, A., Jansen, W., Pels, T., Pijnenburg, H., & Raat, H. (2013). Cliënt-, professional- en alliantiefactoren: Hun relatie met het effect van zorg voor jeugd [Client, professional and alliance factors: Their relationship with the effect of child and youth care]. Verwey-Jonker Instituut.

- Bartelink, C. (2011). Oplossingsgerichte therapie [Solution focused therapy]. Nederlands Jeugdinstituut.

- Bartels, A. A. J. (2001). Behandeling van jeugdige delinquenten volgens het competentiemodel [Treatment of juvenile delinquents according to the competence model]. Kind en Adolescent, 22(4), 39–226. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03060818

- Bastiaanssen, I. L. W., Delsing, M., Kroes, G., Engels, R., & Veerman, J. W. (2014). Group care worker interventions and child problem behavior in residential youth care: Course and bidirectional associations. Children and Youth Services Review, 39, 48–56. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2014.01.012

- Bastiaanssen, I. L. W., Kroes, G., Nijhof, K. S., Delsing, M., Engels, R., & Veerman, J. W. (2012). Measuring group care worker interventions in residential youth care. Child & Youth Care Forum, 41(5), 447–460. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10566-012-9176-8

- Bramsen, I., Kuiper, C., Willemse, C., & Cardol, M. (2019). My path towards living on my own: Voices of youth leaving Dutch secure residential care. Child and Adolescent Social Work Journal, 36(4), 365–380. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10560-018-0564-2

- Brauers, M., Kroneman, L., Otten, R., Lindauer, R., & Popma, A. (2016). Enhancing adolescents’ motivation for treatment in compulsory residential care: A clinical review. Children and Youth Services Review, 61, 117–125. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2015.12.011

- Burke, B. L., Arkowitz, H., & Menchola, M. (2003). The efficacy of motivational interviewing: A meta-analysis of controlled clinical trials. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 71(5), 843–861. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.71.5.843

- Colson, D. B., Cornsweet, C., Murphy, T., O'Malley, F., Hyland, P. S., McParland, M., & Coyne, L. (1991). Perceived treatment difficulty and therapeutic alliance on an adolescent psychiatric hospital unit. The American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 61(2), 221–229. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0079253

- Colton, M., & Roberts, S. (2007). Factors that contribute to high turnover among residential child care staff. Child & Family Social Work, 12(2), 133–142. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2206.2006.00451.x

- Connor, D. F., Doerfler, L. A., Toscano, P. F., Volungis, A. M., & Steingard, R. J. (2004). Characteristics of children and adolescents admitted to a residential treatment center. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 13(4), 497–510. https://doi.org/10.1023/B:JCFS.0000044730.66750.57

- Connor, D. F., McIntyre, E. K., Miller, K., Brown, C., Bluestone, H., Daunais, D., & LeBeau, S. (2003). Staff retention and turnover in a residential treatment center. Residential Treatment for Children & Youth, 20(3), 43–52. https://doi.org/10.1300/J007v20n03_04

- Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (2002). Handbook of self-determination research. University of Rochester Press.

- De Haan, A., Prinzie, P., & Deković, M. (2012). Gerelateerde ontwikkeling van externaliserend gedrag en opvoedgedrag bij kinderen en adolescenten [Related development of externalizing behaviour and upbringing behaviour among children and adolescents]. Pedagogiek, 32(1), 32–50. https://doi.org/10.5117/PED2012.1.HAAN

- De Valk, S. M. (2019). Under pressure: Repression in residential youth care [Doctoral dissertation]. University of Amsterdam.

- Eenshuistra, A., Harder, A. T., & Knorth, E. J. (2020). Professionalizing care workers: Outcomes of a ‘Motivational Interviewing’ Training in residential youth care. Residential Treatment for Children and Youth. doi:10.1080/0886571X.2020.1739597

- Englebrecht, C., Peterson, D., Scherer, A., & Naccarato, T. (2008). “It’s not my fault”: Acceptance of responsibility as a component of engagement in juvenile residential treatment. Children and Youth Services Review, 30(4), 466–484. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2007.11.005

- Exalto, J., Bekkema, N., De Ruyter, D., Rietveld-van Wingerden, M., De Schipper, C., Oosterman, M., & Schuengel, C. (2019). Sectorstudie Geweld in de residentiële jeugdzorg [Sector study Violence in residential youth care]. Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam.

- Feldstein, S. W., & Ginsburg, J. I. (2006). Motivational interviewing with dually diagnosed adolescents in juvenile justice settings. Brief Treatment and Crisis Intervention, 6(3), 218–233. https://doi.org/10.1093/brief-treatment/mhl003

- Flick, U. (2014). An introduction to qualitative research. SAGE.

- Forman, S. G. (2015). Definitions, key components, and stages of implementation. In Implementation of mental health programs in schools: A change agent’s guide (pp. 9–20). American Psychological Association.

- Friese, S. (2012). Qualitative data analysis with ATLAS.ti. SAGE.

- Gilman, R., & Anderman, E. M. (2006). The relationship between relative levels of motivation and intrapersonal, interpersonal, and academic functioning among older adolescents. Journal of School Psychology, 44(5), 375–391. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsp.2006.03.004

- Harder, A. T. (2011). The downside up? A study of factors associated with a successful course of treatment for adolescents in secure residential care (Doctoral dissertation). Groningen, the Netherlands: University of Groningen.

- Harder, A. T. (2018). Residential care and cure: Achieving enduring behavior change with youth by using a Self-Determination, Common Factors and Motivational Interviewing approach. Residential Treatment for Children and Youth, 35(4), 317–335. doi:10.1080/0886571X.2018.1460006

- Harder, A. T., & Eenshuistra, A. (2017). Up2U: Een handleiding voor motiverende mentor/coachgesprekken in de residentiële jeugdzorg [Up2U: A manual for motivational mentor/coach conversations in residential youth care]. Groningen, the Netherlands: University of Groningen.

- Harder, A. T., Knorth, E. J., & Kalverboer, M. E. (2013). A secure base? The adolescent-staff relationship in secure residential youth care. Child and Family Social Work, 18(3), 305–317. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2206.2012.00846.x

- Harder, A. T., Knorth, E. J., & Zandberg, T. (2006). Residentiële jeugdzorg in beeld: Een overzichtsstudie naar de doelgroep, werkwijzen en uitkomsten [Residential youth care in the picture: A review study of its target group, methods and outcomes]. Amsterdam: SWP Publishers.

- Hicks, L. (2008). The role of manager in children's homes: The process of managing and leading a well‐functioning staff team. Child & Family Social Work, 13(3), 241–251. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2206.2008.00544.x

- Hicks, L., Gibbs, I., Weatherly, H., & Byford, S. (2009). Management, leadership and resources in children's homes: What influences outcomes in residential child-care settings? British Journal of Social Work, 39(5), 828–845. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjsw/bcn013

- Horner, R. H., Sugai, G., & Fixsen, D. L. (2017). Implementing effective educational practices at scales of social importance. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 20(1), 25–35. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10567-017-0224-7

- Hruschka, D. J., Schwartz, D., St. John, D. C., Picone-Decaro, E., Jenkins, R. A., & Carey, J. W. (2004). Reliability in coding open-ended data: Lessons learned from HIV behavioral research. Field Methods, 16(3), 307–331. https://doi.org/10.1177/1525822X04266540

- James, S. (2017). Implementing evidence-based practice in residential care: How far have we come? Residential Treatment for Children & Youth, 34(2), 155–175. https://doi.org/10.1080/0886571X.2017.1332330

- Jensen, C. D., Cushing, C. C., Aylward, B. S., Craig, J. T., Sorell, D. M., & Steele, R. G. (2011). Effectiveness of motivational interviewing interventions for adolescent substance use behavior change: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 79(4), 433–440. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0023992

- Kim, J. S. (2008). Examining the effectiveness of solution-focused brief therapy: A meta-analysis. Research on Social Work Practice, 18(2), 107–116. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049731507307807

- Knorth, E. J., Harder, A. T., Zandberg, T., & Kendrick, A. J. (2008). Under one roof: A review and selective meta-analysis on the outcomes of residential child and youth care. Children and Youth Services Review, 30(2), 123–140. doi:10.1016/j.childyouth.2007.09.001

- Kromhout, M. (2002). Marokkaanse jongeren in de residentiële hulpverlening [Moroccan youth in residential care] [Doctoral Dissertation]. Leiden University.

- Landis, J. R., & Koch, G. G. (1977). The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics, 33(1), 159–174. https://doi.org/10.2307/2529310

- Leloux-Opmeer, H., Kuiper, C., Swaab, H., & Scholte, E. (2016). Characteristics of children in foster care, family-style group care, and residential care: A scoping review. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 25(8), 2357–2371. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-016-0418-5

- Maslach, C., Schaufeli, W. B., & Leiter, M. P. (2001). Job burnout. Annual Review of Psychology, 52, 397–422. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.52.1.397

- Miller, W. R., & Rollnick, S. (2013). Motivational interviewing: Helping people change. Guilford Press.

- Miller, W. R., Yahne, C. E., Moyers, T. B., Martinez, J., & Pirritano, M. (2004). A randomized trial of methods to help clinicians learn motivational interviewing. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 72(6), 1050–1062. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.72.6.1050

- Moyers, T. B., Manuel, J. K., & Ernst, D. (2014). Motivational interviewing treatment integrity coding manual 4.1 [Unpublished manuscript]. https://casaa.unm.edu/download/MITI4_2.pdf

- Moyers, T. B., Miller, W. R., & Hendrickson, S. M. L. (2005). How does motivational interviewing work? Therapist interpersonal skill predicts client involvement within motivational interviewing sessions. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 73(4), 590–598. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.73.4.590

- Naar-King, S., & Suarez, M. (2011). Motivational interviewing with adolescents and young adults. Guilford Press.

- Pelletier, L. G., Tuson, K. M., & Haddad, N. K. (1997). Client motivation for therapy scale: A measure of intrinsic motivation, extrinsic motivation, and amotivation for therapy. Journal of Personality Assessment, 68(2), 414–435. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327752jpa6802_11

- Petrie, P., Boddy, J., Cameron, C., Wigfall, V., & Simon, A. (2006). Working with children in care: European perspectives. Open University Press/McGraw Hill Education.

- Prinzie, P., Onghena, P., & Hellinckx, W. (2006). A cohort-sequential multivariate latent growth curve analysis of normative CBCL aggressive and delinquent problem behavior: Associations with harsh discipline and gender. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 30(5), 444–459. https://doi.org/10.1177/0165025406071901

- Prochaska, J., & DiClemente, C. (1982). Transtheoretical therapy: Toward a more integrative model of change. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research and Practice, 19(3), 276–288. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0088437

- Quick, E. K., & Gizzo, D. P. (2007). The “doing what works” group: A quantitative and qualitative analysis of solution-focused group therapy. Journal of Family Psychotherapy, 18(3), 65–84. https://doi.org/10.1300/J085v18n03_05

- Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2000). Intrinsic and extrinsic motivations: Classic definitions and new directions. Contemporary Educational Psychology, 25(1), 54–67. https://doi.org/10.1006/ceps.1999.1020

- Schwalbe, C. S., Oh, H. Y., & Zweben, A. (2014). Sustaining motivational interviewing: A meta‐analysis of training studies. Addiction, 109(8), 1287–1294. https://doi.org/10.1111/add.12558

- Seti, C. L. (2008). Causes and treatment of burnout in residential child care workers: A review of the research. Residential Treatment for Children & Youth, 24(3), 197–229. https://doi.org/10.1080/08865710802111972

- Stals, K. (2012). [De cirkel is rond]. [Onderzoek naar succesvolle implementatie van interventies in de jeugdzorg [The circle is round. Research towards successful implementation of interventions in child and youth care] [Doctoral dissertation]. Utrecht University.

- Stals, K., Van Yperen, T., Reith, W., & Stams, G. J. (2009). Jeugdzorg kan nog veel leren over implementeren [Youth care can still learn a lot about implementation]. Jeugd en Co Kennis, 3(4), 19–28. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03087527

- Stanger, C., Achenbach, T. M., & Verhulst, F. C. (1997). Accelerated longitudinal comparisons of aggressive versus delinquent behaviors. Development and Psychopathology, 9(1), 43–58. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0954579497001053

- Steinlin, C., Dölitzsch, C., Kind, N., Fischer, S., Schmeck, K., Fegert, J. M., & Schmid, M. (2017). The influence of sense of coherence, self-care and work satisfaction on secondary traumatic stress and burnout among child and youth residential care workers in Switzerland. Child & Youth Services, 38(2), 159–175. https://doi.org/10.1080/0145935X.2017.1297225

- Teixeira, P. J., Palmeira, A. L., & Vansteenkiste, M. (2012). The role of self-determination theory and motivational interviewing in behavioral nutrition, physical activity, and health: An introduction to the IJBNPA special series. The International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity, 9, 13–17. https://doi.org/10.1186/1479-5868-9-17

- Ten Brummelaar, M. D. C., Knorth, E. J., Post, W. J., Harder, A. T., & Kalverboer, M. E. (2018). Space between the borders? Perceptions of professionals on the participation in decision-making of young people in coercive care. Qualitative Social Work, 17(5), 692–711. https://doi.org/10.1177/1473325016681661

- Van Binsbergen, M. H., Knorth, E. J., Klomp, M., & Meulman, J. J. (2001). Motivatie voor behandeling bij jongeren met ernstige gedragsproblemen in de intramurale justitiële jeugdzorg [Motivation for treatment of young people with serious behavioral problems in intramural judicial youth care]. Kind en Adolescent, 4(22), 193–203.

- Van Dam, C., Nijhof, K. S., Veerman, J. W., Engels, R., Scholte, R. H. J., & Delsing, M. (2011). Group care worker behavior and adolescents’ internalizing and externalizing problems in compulsory residential care. Residential Treatment for Children & Youth, 28(3), 232–250. https://doi.org/10.1080/0886571X.2011.605050

- Van der Ploeg, J. D. (2003). The underappreciated residential care workers. In J. D. van der Ploeg (Ed.), Bottlenecks in child and youth care: Underexposed topics (pp. 94–104). Lemniscaat (in Dutch).

- Verhage, V. (2022). Psychosocial care for children and adolescents: Functioning of clients and professionals [Doctoral dissertation]. University of Groningen.

- Wigboldus, E. H. M. (2002). Opvoedend handelen in een justitiële jeugdinrichting. Systematisering van het behandelaanbod binnen Rentray [Parenting in a judicial youth institute. Systematisation of the treatment program within Rentray] [Doctoral Dissertation]. University of Groningen.