Abstract

This research explored the acceptability of an evidence-informed healthy relationships program with newcomer youth at three newcomer-serving agencies. Utilizing mixed methods in an embedded multiple case study design, qualitative and quantitative data were collected from seven facilitators, three administrators, and 20 youth recipients from three agencies. Findings suggested the program is promising in terms of acceptability and fit as facilitators and youth recipients enjoyed the program and felt the content was relatable to youths’ experiences. Stakeholders also shared recommendations for tailoring content and activities to be more accessible and culturally meaningful for newcomer youth.

Youth in Canada experience violence in relationships and negative mental health at rates that warrant public health approaches to prevention, particularly as these health concerns predict challenges in adulthood (Leadbeater et al., Citation2017; Malla et al., Citation2018). To address these concerns, there has been a growing emphasis on the use of evidence-based programs (EBPs) that combine prevention and promotion strategies to promote healthy development (Mihalic & Elliott, Citation2015). These programs can benefit all youth, not just those exhibiting challenges, by taking a strength-based approach to build resilience while reducing the prevalence of challenges (e.g., Crooks et al., Citation2018). Extending these practices into diverse settings with vulnerable and marginalized groups is also critical given that these groups tend to experience greater rates of violence and negative mental health outcomes (Canadian Mental Health Association Ontario, Citation2014; Centre for Addiction and Mental Health, Citation2014).

Despite increased emphasis and availability, there remain many challenges to the successful implementation of EBPs (e.g., funding, program fit, lack of agency buy-in, difficulties with adaptations, sustainability) and the field of implementation science has grown significantly to investigate how to bridge the gap between research and practice (Vroom & Massey, Citation2022). Acceptability is a major domain within the implementation science field that considers how appropriate (i.e., agreeable, palatable, and satisfactory) a program is perceived to be by stakeholders (Proctor et al., Citation2011). The focus of the current exploratory case study was to investigate the acceptability of an evidence-informed healthy relationships promotion and violence prevention program for newcomer youth.

Growing population of newcomers in Canada

Immigration currently accounts for approximately 75 percent of population growth in Canada (Immigration, Refugees, and Citizenship Canada, Citation2022). The country welcomed the largest number of permanent residents in a single year in its history in 2021, including more than 250,000 immigrants for economic development and more than 20,000 refugees (IRCC, Citation2022). Notably, Canada was identified as having resettled more refugees in 2021 than any other country in the world, according to the United Nations Refugee Agency Global Trends Report (United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, Citation2022).

Immigrants and refugees often have situational differences in their migration trajectories and experiences. Immigrants may relocate willingly and are typically well-prepared for their departure and settlement in a new location; whereas refugees are forced out of their country, often come with few personal belongings and no documentation, have few financial resources upon arrival, and experience uncertainty about their citizenship status upon entry into a new country (Chrismas & Chrismas, Citation2017). Refugees may have left family behind, and many experience traumatic life events (e.g., war, violence, death of a loved one, and torture) that may result in post-traumatic stress symptoms (McCarthy & Marks, Citation2010). However, immigrants may also experience trauma and similar hardships. Furthermore, heterogeneity exists both across and within these sub-groups, contributing to diverse outcomes related to adjustment, mental health, and well-being (Robert & Gilkinson, Citation2012). Although immigrant and refugee migration trajectories tend to differ, post-arrival stresses can be experienced by all newcomers who have resettled in a new country where they must adapt to a new society, navigate a new culture and language, and reconstruct their social networks. The term newcomer will be used throughout this paper as an inclusive category that describes immigrants and refugees who have been resettled in a country for 5 years or less.

Adversities and specific risk factors related to migration put newcomer youth, and particularly refugee youth, at risk for experiencing challenges that could impede healthy development and well-being (Kirmayer et al., Citation2011). Following the journey to a new country, stressors that young people may experience include further separation from family, acculturation and intergenerational conflict, language barriers, and unwelcoming communities and schools (Kirmayer et al., Citation2011). Although there are integration supports in schools and communities, recent newcomer youth have reported concerns with respect to their relationships and social interactions, including lack connection with peers, being the victim of bullying, and racism and discrimination, which can result in difficulty making friends, feelings of isolation, and lack of belonging (Guo et al., Citation2019; Hadfield et al., Citation2017; Smith et al., Citation2022). Furthermore, these adversities may contribute to engagement in risk behaviors and result in negative outcomes (i.e., susceptibility to peer pressure, substance use, poor school performance, high school dropout, mental health issues, violence in relationships) that can impede healthy development (Chrismas & Chrismas, Citation2017; Rossiter & Rossiter, Citation2009).

While these young people demonstrate an incredible amount of resilience, there is a need to provide specific support promoting the well-being and healthy development of many newcomer children and youth (Eruyar et al., Citation2018; Marshall et al., Citation2016). Newcomer youth who are experiencing concerning health behaviors and issues impacting their mental well-being are not as likely to reach out to receive support in their community (Bushell & Shields, Citation2018). Reducing barriers and linking young newcomers to supports is essential for positive adjustment, and newcomer-serving agencies are often one of the first sites of support for these youth upon arrival to Canada.

Implementation gap

EBPs have become more readily available and utilized in the last three decades as recognized approaches (i.e., activities, frameworks, policies, and strategies) that are supported by rigorous research for improving service outcomes (Vroom & Massey, Citation2022). While there are social-emotional learning (SEL) approaches for promoting healthy development and reducing risky behavior with evidence to support their effectiveness and efficacy (e.g., see Taylor et al., Citation2017), to date, few studies have specifically evaluated the development and implementation of EBPs for young newcomers (Eruyar et al., Citation2018). Furthermore, implementation research to better understand and support successful community implementation (i.e., acceptable and sustainable) of programming for youth, particularly as it relates to adaptations of programs to other cultural, linguistic, and socioeconomic groups, remains relatively unexplored to date (Arora et al., Citation2021; Brown et al., Citation2018; Cabassa & Baumann, Citation2013; Kim et al., Citation2020). Thus, not much is known about “what works” with newcomer populations and “how it works” in real-world settings such as newcomer-serving agencies.

Adapting existing EBPs to increase cultural relevancy and meet the unique needs for newcomer populations is one approach to expanding public health efforts to improve the healthy development of vulnerable and marginalized populations (O'Connell et al., Citation2009). In addition to having empirically-supported intervention principles, adapting EBPs is typically quicker and less expensive than developing programs from the ground up to bring to scale and to exert a public health effort (Okamoto et al., Citation2014). The growing literature suggests that delivering interventions with cultural adaptations can result in positive outcomes with ethnocultural groups (e.g., Barrera et al., Citation2013; Bernal et al., Citation2009; Castro Olivo et al., Citation2022; Hoskins et al., Citation2018; Ivanich et al., Citation2020).

There is a need to explore how to effectively adapt and implement programming in locations serving vulnerable and marginalized youth, such as newcomer-serving agencies, given the gaps in research and practice. Adoption of EBPs in social service settings often requires the formation of community-research partnerships and an infrastructure to support technical, logistical, financial, administrative and evaluative needs associated with the program (O'Connell et al., Citation2009). As such, there has been a move toward co-creation research which involves external, university-based researchers collaborating with community-based practice sites to produce and share knowledge related to programming for child and youth mental health (Craig et al., Citation2021).

Overview of the Healthy Relationships Plus-Enhanced program

The Healthy Relationships Plus-Enhanced (HRP-Enhanced) program is an evidence-informed approach developed for vulnerable youth aged 14 to 21 in school or community settings. This 16-session manualized program occurs in small groups format and draws on core components from the Fourth R, an evidence-based curriculum delivered in schools that addresses healthy relationships promotion and violence prevention (Wolfe et al., Citation2009, Citation2012). The evidence base for the Fourth R curriculum includes rigorous research demonstrating positive benefits from participation related to reduced dating violence, increased condom usage, a protected effect on violent crime among maltreated youth, development of peer resistance skills for managing peer pressure, and increased awareness of the impact of violence and healthy coping skills (Crooks et al., Citation2018).

Like the Fourth R, the HRP-Enhanced program was designed to simultaneously address both risk and protective factors by focusing on healthy relationships. Specifically, the program is rooted in competence enhancement and social resistance skills training to promote healthy development and reduce risk related to adverse health outcomes, including mental health, substance misuse, and bullying (Exner-Cortens et al., Citation2020). Youth participating in the HRP-Enhanced program are taught skills and strategies through interactive learning (i.e., extensive skills practice) and discussion (Crooks et al., Citation2018). The program addresses topics such as media literacy, peer pressure, impacts of substance use, help-seeking, healthy vs. unhealthy forms of relationships, healthy communication, mental health, and suicide prevention. An outline of all topics covered can be found elsewhere (Kerry, Citation2019).

Implementation of the HRP-Enhanced program in the context of newcomer-serving agencies has not previously been evaluated to date, however, the program offers flexibility in where and how it is delivered and has been successfully implemented in other novel settings such as youth justice systems and child and youth protection organizations (e.g., Kerry, Citation2019; Houston, Citation2020). The program has also been adapted for other youth groups including Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Trans, Two Spirit, Queer/Questioning (LGBT2Q+) youth (Lapointe & Crooks, Citation2018). In a randomized controlled trial in a non-clinical sample of youth (n = 212) recruited from high schools, it was found that youth who participated in the HRP program experienced decreased bullying victimization and demonstrated increased help-seeking behavior (Exner-Cortens et al., Citation2020). Furthermore, in this study, the most vulnerable youth reported decreased cannabis use. In another study examining the effectiveness of the program, Lapshina et al. (Citation2018) used a latent class growth analysis to assess depression and anxiety before and after participation in the HRP (n = 170). They found that youth with the highest levels of depression showed significantly reduced depression at the conclusion of the program. With respect to anxiety, although youth with the highest levels of anxiety did not show a significant decrease, those with moderate levels did show significant improvement.

Rationale for implementation of HRP-Enhanced at newcomer-serving agencies

Healthy relationships are essential to youth well-being and development. In the case of migration, social connection, including relationships networks and social structures, are viewed as a vital component for successful integration (Ager & Strang, Citation2008). The HRP-Enhanced has a focus on acquiring interpersonal skills with opportunities for skill-building through interactive role-playing that may assist recent newcomer youth in developing healthy relationships. Additionally, the program could assist these young people with navigating their social world in a new country and developing a sense of belonging. These benefits could be particularly important for prevention of risky behavior given that newcomer youth may be vulnerable to peer pressure (Chrismas & Chrismas, Citation2017) and can experience violence during their pre-migration journey and in their familial relationships that might put them at risk of violence later in life (Rossiter & Rossiter, Citation2009; Timshel et al., Citation2017).

Although many existing programs for newcomers have predominantly been prevention-oriented or risk-focused, scholars have suggested that culturally-responsive programming should aim to promote resilience in addition to addressing risk among youth (Crooks, Smith, et al., Citation2020). This view aligns with a positive youth development approach that emphasizes successful development as resulting from the presence of protective factors such as positive social connections rather than the absence of risk (Guerra & Bradshaw, Citation2008). The HRP-Enhanced includes sessions on mental health promotion and resiliency including opportunities to increase social and emotional competencies and develop healthy stress management and coping skills. Further, the program was tailored for vulnerable populations and takes a trauma-informed lens that may be particularly important for refugee youth who have experienced trauma and distress during their migration journey. Finally, the program was developed with supported literacy options (i.e., fewer reading and writing tasks), which increases the accessibility for newcomer youth who are learning or struggling with the official languages of Canada.

It was recognized that the HRP-Enhanced was not developed to meet all the complex integration needs of newcomer youth upon arrival to Canada, nor does this program address the ongoing systemic concerns around racism and oppression that exist; discussion of policies and programs addressing these matters are also extremely important to support the adjustment and well-being of newcomers and can be found elsewhere (e.g., Blower, Citation2020; Brar-Josan & Yohani, Citation2019; Korntheuer & Pritchard, Citation2017). Understanding the role of individual programs needs to be embedded in an understanding of the larger structures and systems that play a role in youths’ adjustment. Nonetheless, individual strengths-based programs have the potential to benefit youth (Shek et al., Citation2019). We believe the HRP-Es focus on universal vulnerabilities, as well as strengths and assets, targets important areas of need for newcomer youth and the program’s flexibility lends itself to implementation in unique settings such as a newcomer-serving agency. Furthermore, delivering programming in a service setting that is trusted and accessed by newcomer youth and their families can increase program engagement (Murray et al., Citation2008).

Present research

It was anticipated that adaptations would be required to make the existing HRP-Enhanced program more culturally appropriate and meaningful for youth prior to conducting efficacy and effectiveness testing. Feasibility studies determine how relevant and beneficial intervention is to a specific context and population, and whether further examination is warranted (Bowen et al., Citation2009). In other words, researchers can test a program on a smaller scale to determine “whether something can be done, should we proceed with it, and if so, how?” (Eldridge et al., Citation2016, p. 8). Furthermore, assessing feasibility is useful when establishing community partnerships in circumstances where limited data exist on the topic, and with populations requiring unique considerations (Bowen et al., Citation2009).

Acceptability is a key area addressed by feasibility studies and can generally be defined as stakeholders’ (i.e., facilitators, administrators, and youth participants) reactions to an intervention (Bowen et al., Citation2009), and more specifically, how appropriate they perceive the program to be (Proctor et al., Citation2011). Assessing acceptability can involve exploring satisfaction, intent to continue use, perceived appropriateness, fit within an organizational context, and perceived positive or negative effects. Implementation outcomes related to acceptability can have implications for long-term success of implementation in the intended settings including adoption, penetration, and sustainability (Proctor et al., Citation2011).

This research was exploratory in nature as we chose a mixed-methods case study format to capture aspects of acceptability. Fàbregues and Fetters (Citation2019) outline key features of case studies including in-depth analysis of a particular case, whereby the study design allows for a naturalistic approach, often utilizing a variety of methods and data sources to capture the context in which a case being examined is embedded. Case studies have been previously used as an appropriate method for assessing acceptability in terms of evaluating programs and determining if further evaluation is warranted (e.g., Esquivel et al., Citation2022; Rajaraman et al., Citation2012). Thus, we chose a case study to assess acceptability in the context of real-world messiness where variability in community settings was a factor (vs. research conducted in controlled settings). We investigated the following research question: How do youth, facilitators, and administrators view the acceptability of the HRP-Enhanced at newcomer-serving agencies?

Theoretical framework

Our research was grounded in a perspectivism framework, recognizing the importance of contexts and developing partnerships with community stakeholders as co-producers of knowledge (Tebes et al., Citation2014). Our research team worked in close collaboration with agencies to learn about their implementation experiences, determine the acceptability of a healthy relationships program with the community of youth with whom they work, and how to make it more meaningful for their youth. Additionally, Sekhon et al.’s (Citation2017) multi-construct theoretical framework was used to organize our understanding of acceptability. This comprehensive framework was developed to assess acceptability for recipients and facilitators of healthcare interventions and can be used both prospectively and retrospectively. Acceptability in this framework is defined as “A multi-faceted construct that reflects the extent to which people delivering or receiving a healthcare intervention consider it to be appropriate, based on anticipated or experienced cognitive and emotional responses to the intervention” (Sekhon et al., Citation2017, p. 4).

For the purpose of this study, we selected four constructs of interest (out of seven) outlined in the framework of acceptability that aligned well with our data collection instruments as data were collected as part of a larger project prior to selecting a data analysis approach for this particular study. We believed that data collected could provide rich, detailed information related to the four constructs selected while our data instruments did not capture such data related to the other three constructs. The constructs selected included: affective attitudes, or how stakeholders feel about the program; ethicality, or the extent to which the program has good fit with stakeholders’ value system; burden, in other words, the perceived amount of effort that is required to implement and participate in the program; and perceived effectiveness, which includes perceptions about whether the program is likely to achieve its purpose. These constructs are believed to capture key dimensions of acceptability based on systematic reviews of the literature on acceptability (Sekhon et al., Citation2017).

Methods

Selection of recruitment of study sites

Our research team contacted five newcomer-serving agencies in three cities in Canada to assess potential interest in the implementation of the HRP-Enhanced with youth at their sites. Our team had an existing relationship with one site and formed relationships with the remaining four sites. The first author and other members of the project team conducted site tours to four agencies to learn about the services and support available for newcomer youth and their families and met with staff working with youth. Our team provided a one-day training of the HRP-Enhanced for staff selected by each site and provided a manual to each participant that attended the training. Each agency proceeded in a manner that fit with their mandate and agenda. Consultation was offered to each site, but our team respected their autonomy to implement the program, leading to variability in terms of the group selection process and program delivery.

The current research examined acceptability at three of the five newcomer-serving agencies. The two sites that did not participate in research were unable to complete research; in one case this was due to concerns around a partnership agreement and the other was related to staff turnover (i.e., facilitators and administrators that were trained were no longer working at the site) and low attendance at existing youth programming. Of the three sites that participated in research, two were located in a mid-sized city in Ontario, and the other in a large city located in British Columbia. Although initial plans were to implement the program with youth in person, the COVID-19 pandemic led to all groups being adapted for online implementation. We provided funding to one agency, and another was funded independently to provide healthy relationships programming. The third agency implemented the program with their existing funding.

Description of sites recruited

Site A

Located in a medium-sized city in Ontario, Site A is a large newcomer-serving agency with approximately 100 employees. This agency provides a wide range of services for newcomers of all ages to support integration, including employment assistance, language services, housing for families who have recently arrived in the city and orienting families to the community and resources available. To support youth, services are provided to meet immediate needs and youth can also participate in after-school services to receive assistance with homework, attend classes and programs to learn life skills (e.g., cooking/baking), and connect with other youth in a relaxed space. A unique feature of this site is its offering of Settlement Workers in Schools (SWIS) programming to support children and youths’ integration into the education system. Our team contacted this site and they expressed interest in incorporating the HRP-Enhanced into existing programming (i.e., after school program and SWIS). Fourteen staff members were trained including one administrator.

Site B

Site B, located in British Columbia, is also a large settlement agency in Canada with over 300 employees throughout the province. Similar to site A, site B offers a wide range of services to newcomers of all ages. Youth programming focuses on adjusting to Canada, accessing community supports and resources, life skills classes, opportunities to connect with other youth, community participation opportunities, and one-to-one case management support. This agency also utilizes EBPs to support minority at-risk youth. Staff at Site B reached out to our team expressing interest in implementing the HRP-Enhanced because they had been funded to provide evidence-based violence prevention programming with newcomer youth and their families. In addition to supporting youth with the HRP-Enhanced, site B produced a caregiver workshop series that aligned with the youth sessions to support the family unit. They also conducted focus groups prior to implementation with newcomer parents to determine the needs of youth and their families as it related to relationships. Six staff members were trained for facilitation at this agency.

Site C

Site C is located in a medium-sized city in Ontario and is devoted to supporting the integration of families from Muslim communities and providing culturally-informed services. This agency has approximately 20 staff and focuses on developing EBPs to meet the needs of the individuals and families they serve. Our team had an existing relationship related to programming and research with this site prior to our contact about the HRP-Enhanced. The HRP-Enhanced program aligned well with several of the agency’s core foci, including promotion of family safety, well-being, antiviolence, and augmenting connections. Two staff members attended the initial training and two more attending a subsequent training.

Participants

The HRP-Enhanced was facilitated with youth aged 11–20 who identified as immigrants or refugees. Overall, a total of seven facilitators and three administrators across community partner agencies participated to provide their experiences and perspectives on the program. Six of the facilitators and all administrators identified as female, while the other facilitator identified as male. Three facilitators indicated that they had not previously implemented structured programming like the HRP-Enhanced. Educational backgrounds were in the areas of social work, psychology, child and youth work, and sociology. Facilitators reported a range of 1–15 years of experience working with newcomer youth (M = 5.57; SD = 5.06) and all but one had newcomer backgrounds.

Of the 49 youth who participated in the program across the three sites, 24 youth were eligible to participate in research following program completion. One site did not permit youth focus groups, though facilitator feedback at this site captured youth experiences from their perspectives. Of the eligible youth, 20 provided consent/assent (and parental consent in cases where youth were under 16 years old) to participate in research. Most youth participants (75%) identified as female. See for additional youth participant details. The study was reviewed and approved by our university’s Non-medical Research Ethics Board.

Table 1. Youth participant demographics.

Study design and data collection

To structure our data collection and analyses, we utilized an embedded multiple case design, with the three agencies being the core units of analysis of the study, and facilitators, administrators, and youth identified as subunits embedded within the larger cases. This design allowed for within and between analyses (Yin, Citation2014). Utilizing the perspectivism framework and the multi-construct theoretical framework of acceptability, our findings focused on facilitator, administrator and youth experiences to produce knowledge on the HRP-Enhanced program in newcomer-serving agencies as their experiences are valuable for determining the fit and acceptability (Sekhon et al., Citation2017; Tebes et al., Citation2014). We used multiple sources of data to gain a comprehensive understanding of the implementation process and acceptability. We recognized at the outset that not all sites would be able to complete all measures, so we wanted to offer a range of options that might fit the logistics of the sites.

Measures and data sources

Session tracking sheets

Facilitators were asked to complete a session tracking sheet following the delivery of each session. Session tracking sheets asked facilitators to report on activities completed, successes and challenges experienced during the session, as well as modifications to the session. Examples of questions include: “Was there a specific section or activity that was problematic?” and “Were any modifications or changes made to the session?”

Attendance/engagement tracking sheets

Facilitators completed de-identified attendance/engagement sheets following the delivery of each session to track attendance (i.e., how many sessions each youth received and program completion rate) and rate youths’ level of participation using a legend from 0 to 4 (0 = Absent; 1 = Did not participate; 2 = Minimal participation; 3 = Overall good participation; 4 = Highly active participation).

Research team meeting notes

Throughout the implementation period, bi-weekly team meetings were held by the research team. At these meetings, the team discussed partnerships and contact with partners. Additionally, any concerns that were flagged through communication with the sites were discussed and addressed where possible. For example, consultation was provided to a facilitator who shared some challenges related to meeting youth needs in sessions given the diverse make-up of the group (in terms of age, language, and background), and again later when concerns around online privacy surfaced. At another site, we made note of challenges related to implementation with youth under the recommended age range for the program. A review of these meeting notes was undertaken to inform the results and fill in missing pieces about the implementation process at each site.

Implementation survey

Upon completion of the program, participating facilitators completed an online survey adopted from a feasibility evaluation of a program developed for young newcomers (Crooks, Hoover, et al., Citation2020). Facilitators rated their experience implementing the HRP-Enhanced program. The survey included rating scales and open-ended questions addressing a wide range of topics including recruitment and consent, successes and challenges, modifications made, perceived benefits for youth and facilitators and basic demographic questions about the facilitators. Examples include “How did you identify and recruit youth to participate in the program?” and “Was there anything about the HRP Program that made it difficult to implement? Check all that apply.” The purpose of the survey was to understand facilitators’ view of the program and quantify relevant implementation factors.

Facilitator/administrator focus group

Post-intervention, ten facilitators and administrators participated in four focus groups to further explore experiences implementing the program. The focus group followed a semi-structured guide and inquired about implementation successes and challenges, perceived benefits for youth, and recommendations for changes to the program. The focus group included questions such as, “Overall, what were the biggest successes of the program in your setting?” and “What recommendations would you have to modify/change the program or the process to meet the needs of newcomer youth?” Focus groups ranged in length from 66 to 108 minutes long. The purpose of these discussions was to gather more descriptive data as they related to acceptability and the implementation process. Participants completed a brief demographic questionnaire prior to focus groups.

Youth focus groups

Three focus groups were conducted with 18 youths following the HRP-Enhanced delivery. Focus groups took a semi-structured format in which youth were specifically asked about what they liked/disliked, what they learned, any changes they’ve noticed from participating in the program, activities they thought were most helpful and which were challenging or unhelpful, and recommendations for modifications to the program. Focus groups ranged in length from 33 to 47 minutes. Participants were compensated with a $20 gift card. Youth also completed a brief demographic questionnaire.

Data analyses

Audio-recorded focus group interviews were transcribed using Trint voice-to-text software and reviewed and revised by the first author. Qualitative data, including focus groups and facilitator responses to open-ended questions on the session tracking sheets and implementation surveys, were analyzed using a blended analytical approach (i.e., combining deductive and inductive coding) to organize data into themes and understand how the program was experienced by stakeholders. A within-case analysis was conducted first (for sites B and C), followed by a cross-case analysis to generalize analytically across cases to produce themes.

The primary author created a provisional codebook utilizing the constructs from Sekhon et al.’s (Citation2017) theoretical framework of acceptability. Data were coded line by line using an open-ended coding process that involved reading the raw data and summarizing participant responses related to the research question into short statements. Using the scissor-and-sort method, codes were then organized into meaningful categories and then classified into related constructs from the framework that lent themselves to a key assertion of acceptability (Saldaña, Citation2016). Theme names were produced based on constructs from the framework and content within each theme. Descriptive statistics were used to analyze the quantitative data collected from de-identified attendance/engagement sheets and implementation surveys.

Trustworthiness

To ensure trustworthiness in the data, we implemented several checks that are widely accepted by researchers (Shenton, Citation2004). Data triangulation was achieved through the use different research instruments (i.e., focus groups, implementation surveys, and tracking sheets) and different informants (i.e., youth, facilitators, and administrators) to support credibility of the data (Anney, Citation2014). A purposeful sample was used in this research and thick descriptions related to context of the study, participants, methods, and procedures were provided to allow for transfer of the findings (Anney, Citation2014). To help ensure dependability, members of our team reviewed the texts selected by the first author to illustrate the themes. Though these members did not directly assess coding reliability for the entire interview transcripts, the first author reviewed her process and interpretation of data with her supervisor to allow for deeper reflective analysis (Anney, Citation2014). Finally, focus groups were audio-recorded to ensure that interpretations accurately represented the participants’ responses.

Researchers position

We believe it is important for readers to understand our identities, interest in the topic, and intention for this paper as a context for our findings. We identify as white, heterosexual, cisgender females from Canada. The first author recently completed her doctoral degree in the field of school and applied child psychology, and she completed her dissertation under the second author’s supervision. This manuscript is an adapted version of one of the papers from her dissertation which had an overall aim of accentuating the perspectives of newcomer youth to identify considerations for programming and strategies to promote their healthy development. The second author is a registered psychologist and faculty member at an Ontario university with extensive research experience. Both authors have an interest in supporting the healthy development of children and youth with respect to practice as well as research that evaluates how effective programs get adapted and implemented in different school and community contexts (i.e., for marginalized and vulnerable groups of children and youth).

We recognize we are cultural outsiders and lack shared experience with the participants in this research, and that we are not the experts in understanding how the sites involved in this study operate most effectively in terms of providing programming for their youth. Our intention for this paper was therefore to leverage stakeholder perspectives, including hearing from youth themselves, in order to obtain knowledge and inform adaptations of the HRP-Enhanced and promote youth well-being.

Results

Implementation experiences

As noted, the three sites implemented the HRP-Enhanced with newcomer youth based on their mandate and the context of each site. Additionally, research components depended on the interest, capacity, and logistics of each site. presents information related to program delivery and data collected at each site and presents a high-level overview of facilitators’ implementation experiences, as well as context and differences between sites based on data from surveys and focus groups.

Table 2. Program delivery and data collected at each site.

Table 3. Facilitator implementation experiences.

Acceptability of HRP-Enhanced at newcomer-serving agencies

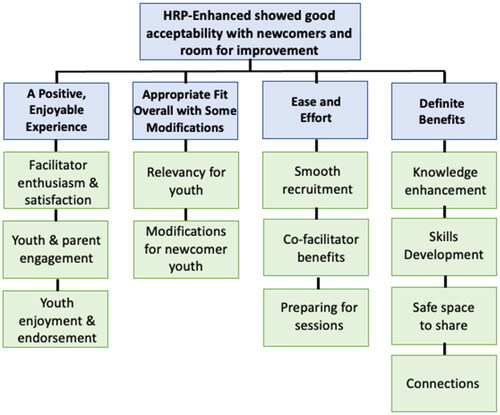

Our qualitative data analysis identified the following: three categories related to affective attitudes that indicated a positive, enjoyable experience; two categories related to the construct ethicality that suggest an appropriate fit for newcomer youths’ needs overall with some modifications; three categories related to the construct burden, representing both ease and effort to implement and participant in the HRP-Enhanced; and four categories related to perceived effectiveness that suggest benefits for youth recipients. A thematic map was developed to display the final overarching assertion, themes, and categories (See ).

Affective attitudes: a positive, enjoyable experience

Across sites, perceptions and feelings toward the HRP-Enhanced program were positive overall as evidenced by facilitator enthusiasm and satisfaction, perceptions of participant engagement, and youth enjoyment and endorsement. Firstly, facilitators and administrators expressed enthusiasm and satisfaction with the program. Facilitator one from site B commented, “Well, I personally love the curriculum…There’s so many things to learn from the curriculum.” Another facilitator who had previous experience implementing the program said, “So [administrator] kind of asked me because she knows I really like this program and I'm the one who gets excited to kind of get it started whenever there are new batch of youths coming in” (Facilitator 1, site A). With respect to content and activities, facilitators liked being able to make connections to earlier topics and build on previous themes. These views were highlighted by facilitators at sites B and C where more content from the HRP-Enhanced was covered in comparison to site A where approximately only half of the program was covered. Facilitators from all three sites liked observing youth learn and engage in critical thinking during sessions.

Another category supporting this theme related to facilitators’ perceptions of youth and parent engagement. During focus groups, facilitators discussed youths’ enjoyment and indicated youth were generally engaged with content and activities except for some instances where there was limited to no responses from youth. Instances when youth were not engaged often seemed to be related to shyness/lack of comfort, particularly near the beginning of the program, in coed groups (site A and B), and possibly due to language differences or lack of understanding (site A). Nevertheless, one facilitator said:

I mean, first, I think youth really did enjoy the program and I think they really enjoyed especially the games and activities. They seemed to really be engaged. It just kind of showed through their participation and engagement… and that’s what also made it very successful.” (Facilitator 2, site A)

Youth themselves expressed a high degree of enjoyment and endorsement with the program. When prompted to discuss the specific aspects of the programming they found enjoyable, several youth commented that they liked all the topics, although particularly enjoyable topics included assertive communication, boundaries, managing stress, and handling peer pressure. With respect to activities, youth liked the informal structure (i.e., being able to “talk freely”), discussion and hearing other youths’ perspectives, having check-ins, and working through scenarios to be able to think critically and build skills. Youth shared the following:

So, I really like that- how they went into detail with this stuff. And they also focused on how you can manage this stuff in real life, like using the assertive communication skills or how to manage stress by jogging, running, doing yoga, reading books and so on and so forth. (Youth 1, site A)

For me, actually, I feel like all the session(s) was like, very good. All of them [were] good because we learned so much…but the specific thing that I liked is about the mental health, like how we talk about it. And there are like sessions with facilitators- like all of them- they were like we can speak with them like normally, but that was a good thing. (Youth 3, site C, group 2)

It’s a really good eye opener for youth, especially for the ones that are coming to Canada directly to high school or maybe even other teenagers. Maybe they haven’t learned about this, or they have and haven’t really taken it seriously, or nobody actually told them how important these things are. So, yeah, I would. (Youth 5, site A)

Yeah, for me, I would [recommend], because I think it will help them a lot of developing, being a social person and talking about your thoughts and how you think about your ideas. So I think it will be really helpful for them. Even if they don’t know English, it will be comfortable to say in their language. (Youth 4, site C, group 1)

Survey data further supported the overall positive experiences with the HRP-Enhanced. Facilitators who completed the implementation survey rated implementation to be “very much” a positive experience and indicated that they would definitely implement the program again. They all also indicated they would recommend the HRP-Enhanced to colleagues and felt youth enjoyed the program “very much”. Facilitators’ ratings of youth engagement ranged from 2 to 4 at site A (M = 2.90, SD = 0.16), and 1 to 4 at site C (Group 1 M = 3.66, SD = 0.39; Group 2 M = 3.53, SD = 0.47). The mean ratings suggest participants were generally well-engaged throughout sessions. In sum, this theme suggests mostly positive feelings and views toward the HRP-Enhanced.

Ethicality: an appropriate fit overall with some modifications

Focus group data suggested that the HRP-Enhanced was viewed as a good fit for youths’ needs and values as most content was perceived to be relevant; however, some modifications were undertaken by facilitators to make the program more accessible for newcomers. Recommendations were also provided by all sites to make the program more meaningful for youth at newcomer-serving agencies.

When speaking about the relevancy of the HRP-Enhanced content for youth in general, one facilitator said:

…because they come across them in their everyday lives, but maybe don’t have the space to really reflect or to talk or to think about how skills are related to friendships or communication. And so- and it’s all everyday stuff for all of us. Sometimes even [Facilitator 2], [Facilitator 3], and I would reflect, I wish I had a program like this when I was younger. (Facilitator 1, site C)

I had a girl who was- when we were talking about the topic of dating violence and abuse, which is a very sensitive topic, and she even mentioned something about her friend and how her friend was maybe experiencing some of these things… she was talking to her friend about it. Maybe even mentioned about the content she has learned in the program, you know, which is really great. (Facilitator 2, site A)

The emphasis on parents is that having run the focus groups before we started the workshop and having the parents input as well as youth input was important because when we did a focus group with the Mandarin community, it came through very loud and clear that they wanted this…we learned the community needs and I think knowing that really helped us focus or get participants be really interested in what we had to deliver. (Administrator 1, site B)

With respect to youth perspectives, recipients of the program shared that discussion topics related to their experiences as teenagers and believed the skills they learned will be useful to help them navigate social interactions. As one youth explained, “Yeah, because especially in high schools, so we get to see a lot of these discussions and fights. Sometimes we don’t know how to respond and sometimes we need to be in the situation just to help” (Youth 2, site C, group 2). A number of youth believed the knowledge they gained was “good preparation” for what they might experience in the future, and commented on the diversity of topics. One youth said, “I personally like that they have a variety of topics. If there’s one topic you don’t really enjoy, you’ll still like to a lot of them. So, there’s a lot that really fit for me” (youth 2, site A). Relating the relevance to the newcomer experience, another said:

When newcomers come to Canada, in my opinion, they will be very shy, they won’t be able to communicate with other people, they are not going to be a social person. Where if they joined this group, they will be more comfortable where they can talk with others and not be shy. Yeah, and it will help them in the future in their lives. (Youth 5, site C, group 1)

We had to simplify a lot of the stuff because I know- I remember one of them even asked, “what is dating violence?” Yeah. And so, I had to kind of on the spot explain what that means and what this looks like, you know, because I mean, it’s a concept that we use in English and we know what it refers to. (Facilitator 2, site A)

So, we kind of have to show them what this looks like. So, I think that the modeling piece had to be there. So, they kind of could then conceptually understand what we were asking them, because I think some of the activities were quite new to them, you know?…And then another thing I wanted to mention was having visuals…We kind of had to make it short and sweet. And if you had a visual, to show what we’re trying to do or, you know, then they would respond to that faster. (Facilitator 2, site A)

Burden: ease and effort

This theme reflects perceptions related to effort required to implement and participate in the HRP-Enhanced program as well as factors that reduce this effort. Facilitators shared that recruitment was straightforward and having co-facilitators was beneficial. That said, planning for sessions required time and consideration, especially because the program needed to be adjusted for virtual implementation. The modifications made to support newcomer youth also required additional time and planning.

Firstly, with respect to ease, youth recruitment was perceived to be smooth in all three settings. Reasons for smooth recruitment included existing relationships with participants and their families, community connections, and engagement with settlement workers to help identify participants: “Settlement workers reached out to parents and then in return, parents passed on the information and then got to more know about it and then give a consent to it. So, it came along well is what I feel” (Facilitator 1, site A).

Another key finding related to ease was the presence of a co-facilitator. Co-facilitators can share the workload required to implement the program, monitor youth during sessions, and support each other:

…having [a] co-facilitator really did help because both of us could be cohosts if one drops out, the other would pick up or if, you know, for some reason, if I'm not able to check the chat box, then the other person can check the check box and kind of, you know, hold the questions as well… (Facilitator 1, site A)

Yeah. And some girls, they didn’t know how to explain their ideas in Arabic, they explained in English, and the same in English. [If] they didn’t know how to explain it in English, they explain in Arabic. Like if we speak Arabic, they understand this. If we speak English, they understand us (Youth 1, site C, group 1)

I would definitely say if it’s one hour a workshop, you really need to have plenty of time before deciding which activity you’re doing and reading each activity and preparing the handouts and everything. So, lots of preparation needed, especially if it’s online. I think it’s even when it’s in person too, you need those handouts and everything ready. The key word, I would say is definitely preparing before the workshops (Facilitator 1, site B)

Effort was also required to modify content for online implementation and address challenges including technical issues (i.e., losing internet connection; microphone not working), difficulty reading reactions without cameras on and privacy concerns, lower attendance, and sessions taking longer than what might be expected in-person.

With respect to recipient perceptions, a couple of youth commented on language being challenging to understand at times. For example, one youth said, “For me personally, not everybody, because I don’t know, like some words that are harder and uncommon, I might not understand it. Just me, probably not everybody” (Youth 2, site A). In this sense, despite youths’ enjoyment with the program and the convenience of joining virtually from home, it was challenging for some youth to participant in discussions at times due to language differences. Some youth also commented on technical challenges and being very busy with school as factors that would make it difficult to participate at times. Youth 2 from group 1 at site C shared, “Yeah, like when it’s online, like, you know, like sometimes like you [have] issue[s] with the Wifi or like steady school." Overall, this theme captured the perceived amount of ease and effort to implement and participate in the HRP-Enhanced at newcomer-serving agencies.

Perceived effectiveness: definite benefits

Facilitators who completed surveys indicated they felt the program was “very much” beneficial to youth. During the focus group discussions, facilitators discussed benefits for youth related to obtaining knowledge and learning relationship skills, as well as increased comfort to share in a safe space and develop connections. As one facilitator summarized:

Firstly, the group provided … a point of connection for youth within the context of the pandemic. Second, I believe that participants were actively engaged in taking in new information and reflecting on skills. There were quite a few sessions where we asked participants if they learned something that they feel they can apply and often they indicated yes. This was true for understanding what boundaries are and why they are important, understanding what is and isn’t a good apology, what is meant by assertive communication, and how to recognize healthy versus unhealthy relationships. (Site C, group 1 Implementation Survey)

So in my life, I react fast. So, when I think about this situation, I need to think first, what is the best for me, because if something happens to me, I will be the responsible- responsible for it. So, I think about the situation and after that, I will focus on how to deal with it. (Youth 4, site C, group 1)

It wasn’t really common sense, but like, there was all the ideas that needed to be said and all the rules that majority- you know, majority of how relationships work or how we also talked about substance abuse and how does that work…So there was just like reminding you that, oh, you have a voice, you are in control of you and what you talk to and you always should be. And there are people there that can help. So, you’re not alone. You know, all these reminders. But it was all like knowledge that majority of teenagers needed to know. Not even teenagers, maybe even young adults that just graduated high school. (Youth 5, site A)

I think it definitely help[ed] them a lot. Just having those safe space[s] to talk about those conversations, because coming to new country, like they don’t, you know- the trauma they have before and now- having that space to talk and share experiences. And you know, learn from each other. And I think it was very, very powerful. And if they-I believe that they left with something from this program, you know, they will remember that program. (Facilitator 3, site C)

For me, I think they built a good relationship between the kids who joined the program and in just 10 days. At the beginning, they didn’t really want to involve. But at the end of the sessions, they were really enjoying the activities and having new friendship. (Facilitator 2, Site B)

Yeah, you feel like you can trust them, they’re like your sisters or like somewhere, you know, from long time, you just can trust them. You can say anything, like your feelings. It’s hard (inaudible) to trust. Like I said, show your emotions and your true self. But with this group, you can just be who you really are. (Youth 3, site C, group 2)

Discussion

The purpose of this case study was to explore factors of acceptability for a healthy relationships program implemented with youth at newcomer-serving agencies. Findings suggested the need for healthy relationships programming with newcomer youth and indicated the HRP-Enhanced is promising in terms of fit and acceptability; however, it would be beneficial to tailor particular sections of the program content to be more culturally meaningful and more accessible for newcomer youth by modifying, adding, or substituting content and activities depending on the youth in the group and their needs.

To some extent, the different successes and challenges at each site reflected site characteristics. For example, site A had the least experience implementing structured programming, and perhaps unsurprisingly, offered the fewest sessions. In contrast to other sites, this site also did not offer language support and as such, challenges were noted related to the understanding of some of the content presented in English. Additionally, the group composition was diverse in terms of culture/race and age range which presented some challenges not seen at other sites with respect to how to make adaptations that were suitable for all youth in the group (e.g., some content that would be appropriate for older youth did not seem appropriate for younger youth).

Site B had a mandate and funding to deeply engage families and was able to align that work to promote the successful implementation of the HRP-Enhanced. Discussion around parent buy-in and involvement in the program (i.e., parent focus groups prior to implementation to discuss content to be covered and a caregiver workshop created to align with youth content) was highlighted in the facilitator focus group as a success. Additionally, this appeared to play a role in youth attendance which was described as another success at this site; youth attendance varied at the other sites where there was no parent component, and was noted as a particular challenge at site C.

Site C has a long history of implementing structured groups and gender-based violence prevention with youth and families from Muslim communities and were able to leverage their expertise and bilingualism to promote successful implementation. Youth at this site spoke of the benefits of having content presented in both English and in their native language when needed. This site also added supplementary cultural content, which they were able to do with ease given their knowledge of the communities they serve. Additionally, a key difference from other sites was the existing relationships between the youth and with groups leaders which promoted comfort and participation. Lastly, the composition of female only groups also seemed to promote comfort and played a role in how content was adapted whereas groups at other sites were coed.

At all sites, we observed surface-structure adaptations (i.e., modifications to curriculum language and images) throughout implementation as described by Okamoto et al. (Citation2014). Stakeholder feedback suggested that surface-structure adaptations to the HRP-Enhanced might be sufficient for newcomer youth to feel connected with the curriculum content. This was a positive finding given that adapting programming is both less expensive and less time-consuming than developing an intervention for a particular group (Okamoto et al., Citation2014).

There were also some deep-structure adaptations, or more substantial changes, at site C to incorporate cultural teachings and to connect to the participants’ values, norms, and lived experiences (e.g., what it means to be a girl in the Middle East; additional focus on gender equality). These adaptations were very well-received by the girls in both groups at this site and highlighted in youth focus groups. Findings reflect the importance of integrating culturally-relevant concepts into programming to most effectively promote well-being (Murray et al., Citation2010). The capacity for this site to go deeper into issues of gender likely reflect the particular experience and expertise at this site, as their primary focus is on the prevention of gender-based violence. Furthermore, as previously mentioned, female groups were only offered at this site.

Authentically engaging newcomer youth

A significant benefit of implementation with youth at newcomer-serving organizations was facilitators’ knowledge about the youth they serve. The value of their expertise in this sense was evident as staff at these agencies have years of working with newcomer youth, and many have their own newcomer background; the lived experiences of facilitators were perceived to promote understanding and the ability to relate and connect with participants in the program. Further, findings suggest in addition to learning social and emotional skills that support their well-being and healthy development, youth benefited from connections and the safe space built through the HRP-Enhanced. Social connections with peers and adults in the community are important for youth following resettlement to support successful integration (Ager & Strang, Citation2008).

Implications

The results of this pilot, along with continued consultation through newcomer partnerships and best practices in the literature for newcomer programming, will be utilized to inform adaptations of a newcomer version of HRP-Enhanced. While a new curriculum does not appear to be warranted, the addition of supplemental materials with suggestions for implementation with newcomer youth would be valuable. This could include a document with considerations for working with newcomer youth and possible adaptations (i.e., modifications and substitutions) for various populations of newcomer youth.

Considerations will still need to be made by organizations for how to implement the program with the unique youth they serve, but program developers can work toward improving ease for planning and implementation. Given that some facilitators indicated they had not previously delivered programming like the HRP-Enhanced, consultation and materials to further increase facilitator knowledge and comfort level would be important. Developing materials to make it easier for facilitators to learn how to deliver programming, fostering a collaborative learning environment, and providing ongoing consultation are a few strategies to enhance adaptation, implementation, and sustainability of a program (Powell et al., Citation2015). Further, organizations should consider selecting facilitators whose experience may complement the trauma-informed care that this program warrants.

Newcomer-serving organizations implementing the HRP-Enhanced should consider the community-based needs of the youth they serve and core cultural constructs (Okamoto et al., Citation2014). Additionally, organizations may consider parental engagement if it seems beneficial to the youth populations they serve. Having clear pathways to engage with parents and key members of the cultural community acted as a facilitator to successful implementation as demonstrated at site B. Furthermore, parents engagement seemed to promote youth attendance at site B. Pre-established connections with families in the communities they serve likely fostered trust which often is perceived to increase the likelihood of participation in community-based interventions (Tsai et al., Citation2021). Further, parental involvement in programming can enhance the program’s impact on their child (Haine-Schlagel et al., Citation2012), and building on family strengths through family engagement can improve programming success and outcomes for newcomer youth (Murray et al., Citation2008; Weine et al., Citation2008).

Across sites, facilitator and administrator perceptions suggested that the program is most meaningful with newcomer youth when intentional recruitment occurs (i.e., “knowing who is in the room”; having clear eligibility requirements) and facilitators are flexible (i.e., prepared to make adaptations). Thus, facilitators may think about considerations for intentional recruitment, including group members’ identities including background, ages, and gender, language proficiency, and migration journeys. For instance, paying attention to language is critical, not only to ensure the vocabulary makes sense to the youth from a cognitive capacity, but also in terms of their lived experience and culture as it seemed that westernized language limited ways for youth to engage at times. The use of visuals was also recommended to promote material accessibility which is consistent with other suggestions for newcomer programming (Crooks, Smith, et al., Citation2020). With respect to age, background, and lived experiences, an important consideration is that the HRP-Enhanced program was developed for mid to late teenagers (i.e., 14 years and older) who may be engaging in risky behavior. As such, some content did not fit with some of the needs of youth (e.g., substance use content was not relevant for younger youth who did not know what the term meant or have exposure to substances). Regarding participants’ migration journey and developmental level, considerations around information processing are relevant for those youth who have experienced trauma (Steele & Malchiodi, Citation2012), while disruption in education throughout migration can also further delay learning. Facilitator flexibility is also important in this sense to accommodate youth’s learning processes and to give youth agency to talk about content they are comfortable with. Furthermore, facilitators implementing the HRP-Enhanced with newcomer youth should be prepared to adapt manual content to be appropriate for participants’ values and needs from a developmental, cultural and language proficiency standpoints.

The inclusion of youth feedback was a significant contribution of this study. Often youth feedback is not gathered during implementation research, yet, their feedback is critical as key stakeholders for which the program was developed for (Flores, Citation2007). Our use of youth focus groups is consistent with recommendations to involve youth in program development and evaluation (Edwards et al., Citation2016). Study designs that examine the effectiveness of programming through youth feedback can encourage reflective learning and be empowering for them (Zimmerman, Citation2000). It could also be beneficial to utilize other methods of obtaining youth feedback to supplement youth focus groups such as brief, directed or nondirected, audio-logs for recoding participant perspectives following each session.

Future research should continue to explore the implementation science behind programming for youth at newcomer-serving agencies as a greater understanding of these factors will improve programming within this context. Incorporating frameworks to guide modifications to the curriculum could help facilitators make changes that are consistent with the goals and philosophy of the program. For instance, the traffic light model which classifies adaptations into green light (safe to change), yellow light (make changes with caution), and red light changes (avoid changes) is a straight-forward and practical approach that clinicians can use to guide and track adaptations (Balis et al., Citation2021; Crooks et al., Citation2015; Rolleri et al., Citation2014).

In the present study, success was established through community-research partnerships as our team’s knowledge of research methods was utilized and partners’ knowledge of participants and implementation experiences in their settings was shared. Collaboration between community organizations and researchers is often important for effective delivery of programming (Chambers & Azrin, Citation2013; O'Connell et al., Citation2009), and for producing and mobilizing knowledge for positive youth development (Craig et al., Citation2021).

Although there were drawbacks, this study additionally adds support for successful implementation of online programming. Zoom was used as a vehicle to meet youth where they were at during pandemic and connect them with others during an isolating time. The virtual implementation of HRP-Enhanced provided structured programming, increased social connections and the quality of relational interactions that had been disrupted by the pandemic (Courtney et al., Citation2020). This could be especially valuable for youth struggling with mental health issues as the pandemic has been reported as exacerbating symptoms. Additionally, for families without transportation or for those with demanding schedules, online implementation improved accessibility because there was no need for physical attendance.

Online implementation would also allow for reaching youth across the country and possibly even youth in rural and remote areas. This could also enable drawing from across geographical jurisdictions resulting in a larger pool of youth participants that would allow for matching of facilitator language to participant language, as well as gendered groups, narrower developmental ages and stages of participants, and groups where participants share first language or cultural backgrounds. One drawback, however, may be losing the benefits associated with preexisting relationships between facilitators and the youth and their families. The success of online implementation has also led to relevant opportunities related to virtual training and communities of practice. Over the past year, our team has offered virtual trainings of the HRP-Enhanced and monthly community of practice meetings to support and build capacity in facilitators from organizations across Canada.

Limitations

This study has several limitations. Firstly, the study design and descriptive nature of results limits the generalizability of findings. Although we began implementing the program with five newcomer-serving agencies, only three elected to participate in this evaluation. The scope of the case study is limited to the contexts at these three agencies and may not apply to other circumstances. Still, the present research adds to the sparse literature on implementing and adopting programming to promote newcomers’ healthy development and the study design seemed appropriate because of the limited control the researchers had over the implementation process. Times of data collection, as well as some methods and informants differed across some sites which limits the conclusions. For instance, no youth data was collected from site B, and thereby, the results only captured youths’ experiences through the perspectives of facilitators and administrators. Although the first author followed steps to increase trust in the data, her biases and lack of shared experience may have influenced the analysis. Finally, given that we included only four of the seven constructs from the comprehensive theoretical framework that we used to organize our understanding of acceptability (because the framework was applied after data were collected), we may have missed capturing other important aspects of acceptability (i.e., intervention coherence, opportunity costs, and self-efficacy; see Sekhon et al., Citation2017). Moreover, as we focused on specific constructs, some data collected fell outside of the constructs and therefore were not included in the results of the present study. Nonetheless, this framework was developed following the first systematic approach to reviewing the literature to define and theorize acceptability and was therefore useful in our current assessment of this concept.

Conclusion

Relationships are a critical context within which youth develop, and although many programs may cover healthy relationship topics to some capacity, the HRP-Enhanced is an entire program focused on essential life skills related to relationships that allow unpacking through discussion and interactive learning. Stakeholder perspectives indicated the HRP-Enhanced is promising for newcomer-serving organizations and considerations were shared for future implementation to improve the meaningfulness of the program for newcomer populations. A strength of the study was the use of triangulated data, offering a more accurate and culturally sensitive approach when conducting research with participants from diverse backgrounds (Suárez-Orozco et al., Citation2010). This work also revealed the need to be intentional and incorporate the voices of stakeholders (i.e., facilitators, youth, and administrators) when considering how content can be augmented to be relevant for the youth these organizations serve to move toward closing the implementation gap.

Ethical approval

All procedures performed involving human participants were in accordance with the ethical guidelines outlined by the Research Ethics Board (REB) at our institution and the national panel for ethical conduct for research involving humans. Our REB operates in compliance with the Tri-Council Policy Statement Ethical Conduct for Research Involving Humans (TCPS2), the Ontario Personal Health Information Protection Act (PHIPA, 2004), and the applicable laws and regulations of Ontario. The project ID assigned by our REB is 114272.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Ager, A., & Strang, A. (2008). Understanding integration: A conceptual framework. Journal of Refugee Studies, 21(2), 166–191. https://doi.org/10.1093/jrs/fen016

- Anney, V. N. (2014). Ensuring the quality of the findings of qualitative research: Looking at trustworthiness criteria. Journal of Emerging Trends in Educational Research and Policy Studies (JETERAPS), 5(2), 272–281. http://hdl.handle.net/123456789/256

- Arora, P. G., Parr, K. M., Khoo, O., Lim, K., Coriano, V., & Baker, C. N. (2021). Cultural adaptations to youth mental health interventions: A systematic review. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 30(10), 2539–2562. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-021-02058-3

- Balis, L. E., Kennedy, L. E., Houghtaling, B., & Harden, S. M. (2021). Red, yellow, and green light changes: Adaptations to Extension health promotion programs. Prevention Science, 22, 903–912. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11121-021-01222-x

- Barrera, M., Jr., Castro, F. G., Strycker, L. A., & Toobert, D. J. (2013). Cultural adaptations of behavioral health interventions: A progress report. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 81(2), 196–205. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0027085

- Bernal, G., Jimenez-Chafey, M. I., & Domenech-Rodrguez, M. M. (2009). Cultural adaptation of treatments: A resource for considering culture in evidence-based practice. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 40(4), 361–368. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0016401

- Blower, J. (2020). Exploring innovative migrant integration practices in small and mid-sized cities across Canada (Working Paper No. 2020/7). Ryerson University. https://www.ryerson.ca/content/dam/centre-for-immigration-and-settlement/RCIS/publications/workingpapers/2020_7_Blower_Jenna_Exploring_Innovative_Migrant_Integration_Practices_in_Small_and_Mid-Sized_Cities_across_Canada.pdf

- Bowen, D. J., Kreuter, M., Spring, B., Cofta-Woerpel, L., Linnan, L., Weiner, D., Bakken, S., Kaplan, C. P., Squiers, L., Fabrizio, C., & Fernandez, M. (2009). How we design feasibility studies. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 36(5), 452–457. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2009.02.002

- Brar-Josan, N., & Yohani, S. C. (2019). Cultural brokers’ role in facilitating informal and formal mental health supports for refugee youth in school and community context: A Canadian case study. British Journal of Guidance & Counselling, 47(4), 512–523. https://doi.org/10.1080/03069885.2017.1403010

- Brown, C., Maggin, D. M., & Buren, M. (2018). Systematic review of cultural adaptations of school-based social, emotional, and behavioral interventions for students of color. Education and Treatment of Children, 41(4), 431–456. https://doi.org/10.1353/etc.2018.0024

- Bushell, R., & Shields, J. (2018). Immigrant settlement agencies in Canada: A critical review of the literature through the lens of resilience. A Paper of the Building Migrant Resilience in Cities (BMRC) Project. York University. https://bmrc-irmu.info.yorku.ca/files/2018/10/ISAs-A-Critical-Review-2018-JSRB-edits-Oct-9-2018.pdf

- Canadian Mental Health Association Ontario. (2014). Advancing equity in mental health: Understanding key concepts. http://ontario.cmha.ca/wp-content/files/2014/05/Advancing-Equity-In-Mental-Health- Final1.pdf

- Cabassa, L. J., & Baumann, A. A. (2013). A two-way street: Bridging implementation science and cultural adaptations of mental health treatments. Implementation Science, 8(1), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-8-90

- Castro Olivo, S. M., Ura, S., & dAbreu, A. (2022). The effects of a culturally adapted program on ELL students’ core SEL competencies as measured by a modified version of the BERS-2. Journal of Applied School Psychology, 38(4), 380–396. https://doi.org/10.1080/15377903.2021.1998278

- Centre for Addiction and Mental Health. (2014). Best practice guidelines for mental health promotion pro- grams: Children (7–12) & youth (13–19). https://www.porticonetwork.ca/documents/81358/128451/Best+Practice+Guidelines+for+Mental+Health+Promotion+Programs+-+Children+and+Youth/b5edba6a-4a11-4197-8668-42d89908b606

- Chambers, D. A., & Azrin, S. T. (2013). Research and services partnerships: partnership: A fundamental component of dissemination and implementation research. Psychiatric Services, 64(6), 509–511. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.201300032

- Chrismas, B., & Chrismas, B. (2017). What are we doing to protect newcomer youth in Canada, and help them succeed? Journal of Community Safety and Well-Being, 2(3), 87–90. https://doi.org/10.35502/jcswb.52

- Courtney, D., Watson, P., Battaglia, M., Mulsant, B. H., & Szatmari, P. (2020). COVID-19 impacts on child and youth anxiety and depression: Challenges and opportunities. The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 65(10), 688–691. https://doi.org/10.1177/0706743720935646

- Craig, S. G., Bondi, B. C., Diplock, B. D., & Pepler, D. J. (2021). Building effective research-clinical collaborations in child, youth, and family mental health: A developmental-relational model of co-creation. Journal of Therapeutic Schools and Programs, 13(1), 102–131. https://doi.org/10.19157/JTSP.issue.13.01.06

- Crooks, C. V., Chiodo, D., Dunlop, C., Lapointe, A., & Kerry, A. (2018). The Fourth R: Considerations for implementing evidence-based healthy relationships and mental health promotion programming in diverse contexts. In A. W. Leschied, D. Saklofske, & G. Flett (Eds.) The handbook of implementation of school based mental health promotion: An evidence-informed framework for implementation (pp. 299–321). Springer Publishing.

- Crooks, C. V., Hoover, S., & Smith, A. C. (2020). Feasibility trial of the school‐based STRONG intervention to promote resilience among newcomer youth. Psychology in the Schools, 57(12), 1815–1829. https://doi.org/10.1002/pits.22366

- Crooks, C. V., Smith, A. C., Robinson-Link, N., Orenstein, S., & Hoover, S. (2020). Psychosocial interventions in schools with newcomers: A structured conceptualization of system, design, and individual needs. Children and Youth Services Review, 112, 104894. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2020.104894.

- Crooks, C. V., Zwarych, S., Hughes, R., & Burns, S. (2015). The Fourth R implementation manual: Building for success from adoption to sustainability. https://cdn.shopify.com/s/files/1/0317/3099/1242/files/4rimplementationmanual1.4.pdf?v=1594138081

- Edwards, K. M., Jones, L. M., Mitchell, K. J., Hagler, M. A., & Roberts, L. T. (2016). Building on youth’s strengths: A call to include adolescents in developing, implementing, and evaluating violence prevention programs. Psychology of Violence, 6(1), 15. https://doi.org/10.1037/vio0000022

- Eldridge, S. M., Lancaster, G. A., Campbell, M. J., Thabane, L., Hopewell, S., Coleman, C. L., & Bond, C. M. (2016). Defining feasibility and pilot studies in preparation for randomised controlled trials: development of a conceptual framework. PLoS One. 11(3), e0150205. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0150205

- Eruyar, S., Huemer, J., & Vostanis, P. (2018). Review: How should child mental health services respond to the refugee crisis? Child and Adolescent Mental Health, 23(4), 303–312. https://doi.org/10.1111/camh.12252

- Esquivel, C. H., Wilson, K. L., Garney, W. R., McNeill, E. B., McMaughan, D. J., Brown, S., & Graves-Boswell, T. (2022). A case study evaluating youth acceptability of using the Connect – A sexuality education game-based learning program. American Journal of Sexuality Education, 17(1), 57–83. https://doi.org/10.1080/15546128.2021.1971128

- Exner-Cortens, D., Wolfe, D., Crooks, C. V., & Chiodo, D. (2020). A preliminary randomized controlled evaluation of a universal healthy relationships promotion program for youth. Canadian Journal of School Psychology, 35(1), 3–22. https://doi.org/10.1177/0829573518821508

- Fàbregues, S., & Fetters, M. D. (2019). Fundamentals of case study research in family medicine and community health. Family Medicine and Community Health, 7(2), e000074. https://doi.org/10.1136/fmch-2018-000074