?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

Identity and resilience are critical during adolescence, especially when facing contextual challenges. This longitudinal study explored the trajectories of identity and resilience in adolescents (n = 546; MAge = 16.22) living in an under-resourced South African community. Associations between identity and resilience were analyzed across three time points using repeated measures ANOVA’s. The dimensions of identity did not vary substantially across time, but resilience scores fluctuated significantly. Participants with high resilience showed a substantial decrease in Exploration in Depth over time, while participants with low resilience showed an increase. The findings provide insights into how to foster resilience in adolescents living in under-resourced communities.

Introduction

The existence of a variety of life choices toward developing optimal functioning and experiencing a sense of well-being not only promotes individual differentiation but also places adolescents in limbo (Hatano & Sugimura, Citation2017; Markovitch et al., Citation2017). Adolescence is a critical period of human development, where individuals are tasked to establish a coherent sense of identity. However, the struggle of transitioning from the childhood world to adolescence comes with multiple challenges. This involves intense weighing of their roles, beliefs, goals, and values to negotiate their place in society. It is important, therefore, to explore how social forces and individual attributes contribute to the development of adolescents and, in particular, those living in disadvantaged communities (Erikson, Citation1968; Mampane, Citation2014; Theron, Citation2019).

Furthermore, identity formation is significantly influenced by resilience. People often come to a deeper self-understanding and acceptance when facing adversities and challenges. Identity can be enhanced while negotiating challenging circumstances (Masten, Citation2018). Many adolescents are driven to overcome the incapacitating effects of risk in their environment and to construct a coherent identity. Mutual interactions between the individual and the environment help adolescents access contextually and culturally meaningful resources and opportunities specific to the adolescent stage. This reality poses unique challenges to South African adolescents from under-resourced backgrounds (Gittings et al., Citation2021; Lebone, Citation2012; Mampane, Citation2012; Theron, Citation2019).

Conceptualizing resilience and identity

Resilience is conceptualized as a dynamic process of interaction between the individual and the environment that mitigates a person’s adaptation to adversity and determines one’s mental health outcomes (Govender et al., Citation2020; Mampane, Citation2012). Moreover, resilience in adolescents is regarded as a dynamic process which changes over time (Masten, Citation2014; Theron & van Rensburg, Citation2018). This implies that social ecologies contribute to the development of resilience by offering adolescents resources and opportunities. Therefore, there is a need to investigate risk and protective factors, scrutinize the interactions in the resilience process and explore the trajectories taken toward resilience by adolescents declared at risk in the South African context (Mampane, Citation2012; van Rensburg et al., Citation2015).

Identity formation is a critical task for adolescents to clarify their roles, values, and beliefs (Erikson, Citation1968; Liu & Ngai, Citation2020). Researchers acknowledge the existence of continuous changes in identity (Luyckx et al., Citation2005, Citation2016; Weiten, Citation2014). The process of forming one’s identity peaks in adolescence but continues for the rest of one’s life (Erikson, Citation1968; Markovitch et al., Citation2017; Tsang et al., Citation2012). Identity formation is conceptualized as an iterative process during which adolescents decide upon options and commit to given decisions after completing a process of exploration, whereby these commitments are subject to constant revision (Crocetti, Citation2017; Luyckx et al., Citation2008). This means that identity formation is a dynamic, recursive, and long-term process that entails continuous loops of feedback and reciprocal cycles that have a bearing on one another (Luyckx et al., Citation2008). Luyckx et al. (Citation2008) suggest a five-dimensional, dual-cycle model to examine such identity development trajectories during adolescence: Exploration in Breadth occurs when adolescents reflect and gather information related to several different options and alternatives, whereas Exploration in Depth helps strengthen and evaluate commitments. Commitment Making is the extent to which individuals adhere to goals, beliefs, and values but does not inevitably imply that one identifies with or is confident with choices made. On the other hand, Identification with Commitments means individuals are content with decisions, which gives them a sense of certainty that they have made the right decisions. Ruminative Exploration is the constant worry about one’s choices and the inability to commit to a given direction. The dual cycle process of the five-dimensional model allows for a differential understanding of identity formation since individual identity formation processes are generally influenced by a myriad of factors across time (Markovitch et al., Citation2017). For instance, the time and the extent of exploration differ from one person to the other. Furthermore, the ability to commit to life choices forming a coherent identity varies from person to person (Cramer, 2017; Klimstra et al., Citation2013; Kroger et al., Citation2010; Markovitch et al., Citation2017). Therefore, it is essential to investigate the different styles individuals use to approach identity-related issues and the factors contributing to identity formation in adolescents.

The relationship between resilience and identity formation

Difficulty and traumatic events have the potential to disrupt identity functioning during adolescence. Individuals often come to a deeper understanding of their identity when confronted with adversity (Masten, Citation2018; Sevilla-Vallejo, Citation2023). People respond differently to challenging events. Exposure to the same incident may result in compromised well-being in some, while it will not affect others. Some individuals might never fully recover from the incident, others might heal slowly, and others might heal rapidly. Individuals who are less affected by difficulty and recover relatively quickly are said to be resilient (Schwartz & Petrova, Citation2018; Waterman, Citation2020). According to Erikson (Citation1968), people with a more established identity structure are more aware of their strengths and shortcomings. Resilience can be observed in individuals who have successfully overcome adversity. The ability to continue expressing personally significant identity commitments in the face of adversity is a sign of identity resilience. The capacity to manage identity-related questions efficiently, leading to healthy identity functioning and quality of life, is a hallmark of identity resilience (Koni et al., Citation2019; Waterman, Citation2020).

Extensive research has been done on the potential disruption of identity development when adolescents are exposed to severe degrees of risk. Facing traumatic events may alter the identity processes, dimensions, meanings, and ideologies they hold (Scott et al., Citation2014; Waterman, Citation2020). Adversity can serve as a reinforcer when adolescents have already committed to identity-relevant choices. Some tend to continue their exploration process by being more dedicated to their goals, roles, beliefs, and values. In this case, the challenge faced is used as a mechanism to confirm their identity-related decisions. However, because of the emotional suffering caused by the encountered challenges, others may abandon their identity-related commitments, causing identity delays (Koni et al., Citation2019; Waterman, Citation2020). Depending on the type of environment and the circumstances surrounding the adolescent, some individuals resume the same path of exploration, whereas others abandon prior commitments (Waterman, Citation2020).

Findings on the adaptive functions of identity have illustrated that adolescents who are endowed with autonomy and motivation are most likely to adjust from a maladaptive status to a resilient status (Masten et al., Citation2004; Masten & Tellegen, Citation2012). Adolescents showing resilience tend to be stable, a phenomenon that manifests across various identity domains. This stability in identity domains provides a psychological strength that allows adolescents to overcome threats to identity due to challenging events. As a result, they are able to keep meaningful commitments or keep exploring despite the hardships and obstacles to identity formation (Schwartz & Petrova, Citation2018; Waterman, Citation2020). In essence, the commitment dimensions of the dual cycle process are positively associated with well-being, whereas the explorative dimensions are negatively related to well-being (Luyckx et al., Citation2006, Citation2008). Moreover, ruminative exploration is related to low levels of well-being (Lindekilde et al., Citation2018; Luyckx et al., Citation2006, Citation2008).

Contextual perspective

From the previous section, it is clear that identity development and resilience are crucial processes during adolescence. Adolescence is a critical period of human development, where individuals are tasked to establish a coherent sense of identity. All societies regard adolescence as a period of social transition to adulthood, which impacts them in different domains (Erikson, Citation1968; Tsang et al., Citation2012). Given the transitional nature of the social context, it is imperative to examine the contextual factors critical to the development of identity and resilience in a South African context. Demographically, South African adolescents living in under-resourced communities face political, social, and economic adversities (Mampane, Citation2014; Ndimande, Citation2009; Romero et al., Citation2018). In the context of this study, the under-resourced community consisted of rural communities which were economically, socially, and educationally disadvantaged by the South African apartheid government. Individuals living in these communities are still socio-economically deprived (Das-Munshi et al., Citation2016; Gradin, 2018; Mal-Sarkar et al., Citation2021). Such under-resourced settings often have high levels of violence and crime with low levels of educational opportunities and income potential. Most adolescents living in such communities experience adverse situations such as exposure to poverty, abuse, trauma, and multiple forms of violence and have limited access to support structures and social resources (Mampane, Citation2014; Ndimande, Citation2009; Romero et al., Citation2018). This reality poses unique challenges for South African adolescents from under-resourced backgrounds (Gittings et al., Citation2021; Lebone, Citation2012; Mampane, Citation2012).

The ramifications of the COVID-19 pandemic exacerbated the conditions of hardship. South African adolescents encounter numerous risks that jeopardize healthy outcomes, and these escalated in the unprecedented times of the COVID-19 pandemic. The effects of the pandemic were evident among adolescents living in contexts of necessity in South Africa, where they experienced heightened stress over the uncertainty regarding education, food security, and widespread hunger due to the strict COVID-19 lockdown (Divala et al., Citation2020; Gittings et al., Citation2021; Govender et al., Citation2020). In essence, adolescents had to suffer the burden of the indirect effects of the pandemic. But most importantly, the possible lifelong ramifications of the COVID-19 pandemic on adolescents’ well-being must be noted (Divala et al., Citation2020; Gittings et al., Citation2021; Govender et al., Citation2020).

The body of research on identity and resilience development mainly focuses on Western populations, and changes in identity formation during adolescence in non-Western contexts remain underexplored (Hatano & Sugimura, Citation2017; Skhirtladze et al., Citation2016). Hatano and Sugimura (Citation2017) highlight the scarcity of longitudinal design studies on the five-dimensional model in non-western populations. Moreover, the longitudinal trajectories taken by South African adolescents toward resilience development remain unexplored (Theron & Van Rensburg, Citation2018). In addition, very few studies have used a longitudinal design to explore the interaction between identity formation and resilience trajectories.

Therefore, the aim of the current study was to examine the longitudinal trajectories of identity formation based on the five-dimensional model of Luyckx et al. (Citation2008) and to explore resilience processes as they pertain to adolescents living in under-resourced communities in South Africa. This included an investigation of the risks and the protective mechanisms that are important in shaping resilience in this particular population of adolescents. The following main research question guided this study: What are the identity and resilience trajectories of adolescents living in under-resourced communities? This question was unpacked through two sub-questions:

Are there significant differences/changes over time in the five identity dimensions (Commitment Making, Exploration in Breadth, Ruminative Exploration, Identification with Commitment, and Exploration in Depth) and resilience? (i.e., What is the effect of time on identity and resilience?)

Are there significant changes over time in the five identity dimensions (Commitment Making, Exploration in Breadth, Ruminative Exploration, Identification with Commitment, and Exploration in Depth) for individuals with high and low resilience? (i.e., Does resilience have a significant impact on identity over time?)

Research methods

This study forms part of a larger longitudinal, mixed-methods research project related to the first author’s doctoral research. In the current study, the relationship between identity formation trajectories and resilience was verified at different points in time. This involved collecting data over a period of twelve months with an interval of six months between the initial time point, the second time point, and the third time point (from March 2020 to March 2021).

Participants and sampling procedures

The population of interest was male and female adolescent high school learners living in under-resourced communities and attending local public schools in the Greater Taung Municipality in the North West province of South Africa. Convenience sampling was employed to select participants for the study. Adolescence is a developmental stage that begins at about the age of 10 years and ends at the age of 24. Variations in the age boundaries of adolescence have been noted by several authors (Louw & Louw, Citation2020; Sawyer et al., Citation2018; Van der Cruijsen et al., Citation2023). Therefore, adolescents between the ages of 12 and 24 years could participate in this study. This age range places the participants in the phase of transition during which adolescents work toward a synthesized identity (Hatano & Sugimura, Citation2017; Louw & Louw, Citation2020; Marcia, Citation1966). All participants who took part in the first time point of the data collection were followed (in intervals of six months) through a second and third time point. The final sample, excluding participants who took part in only one or two phases of the data collection, consisted of 564 participants. The demographics of the sample are presented in .

Table 1. Distribution of the sample regarding age, gender, and language.

Gender groupings were quite evenly represented, with 52.3% female participants and 47.7% male participants. The ages of the participants ranged from 12 to 24 years, with the mean of the sample being 16.22 years (SD = 1.902). Most of the participants were Setswana speaking (96.1%).

Measures

Standardized self-administered surveys were completed at three time intervals: at the initial time point, after six months, and after twelve months. To assess the five dimensions of identity, the Dimensions of Identity Development Scale (DIDS) was used (Luyckx et al., Citation2008; Mastrotheodoros & Motti-Stefanidi, Citation2017). The DIDS consists of 25 five-point Likert-type items, ranging from strongly disagree (1) to strongly agree (5). High scores for each of the five subscales are indicative of a high endorsement of that specific identity dimension (Luyckx et al., Citation2008). Examples of items used to describe each of the five dimensions are: I know which direction I am going to follow in my life (Commitment Making); I think about different goals that I might pursue (Exploration in Breadth); I worry about what I want to do in my future (Ruminative Exploration); My future plans give me self-confidence (Identification with Commitments); and I think about the future plans I already made (Exploration in Depth).

A subscale of the Resilience Questionnaire for Middle-Adolescents in Township Schools (R-MATS) of Mampane (Citation2012) was used to measure resilience. The R-MATS subscale comprises 24 items, measured on a four-point Likert scale, ranging from untrue all the time (1) to true all the time (4). The scores can range from 24 to 96. High scores are indicative of highly resilient behavior (Mampane, Citation2012). Items include: I am in control of what happens to me; I believe that I am able to do better; and I am a tough person.

Cronbach’s alpha coefficients for the DIDS and R-MATS subscales are presented in .

Table 2. Reliability of identity and resilience subscales.

Ethical aspects

The study was granted ethical clearance by the institution’s General Human Research Ethics Committee and the Scientific Committee (Social Sciences) of the Faculty of the Humanities. The principals of the schools and the Department of Basic Education gave their approval for the study to be conducted. Participants who met the requirements for inclusion provided written assent. Parental consent was also gained.

To protect the interests of the participants, the researcher complied with ethical standards throughout the study (Republic of South Africa, Citation2013). The pertinent ethical concepts were informed consent, autonomy, beneficence and non-maleficence, confidentiality, respect for participants, impartiality, and justice (Allan, Citation2017).

Data analyses

The data were analyzed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS, version 28, 2019) and included basic descriptive data analysis, Pearson’s product-moment correlation coefficient (r; to establish the direction and strength of the relationships between identity and resilience) and repeated measures analyses of variance (ANOVA; to analyze the associations between identity and resilience over time).

Results

To answer the first research question (i.e., What is the effect of time on identity and resilience?), a one-way repeated measures ANOVA was performed to analyze the associations between identity and resilience across different points in time (see ). The F statistic was computed to establish the effect of time on identity and resilience. The Mauchly’s Test was conducted to test the assumption of sphericity; sphericity was assumed with the exception of Ruminative Exploration.

Table 3. Results of one-way repeated measures ANOVA for the total group (N = 564).

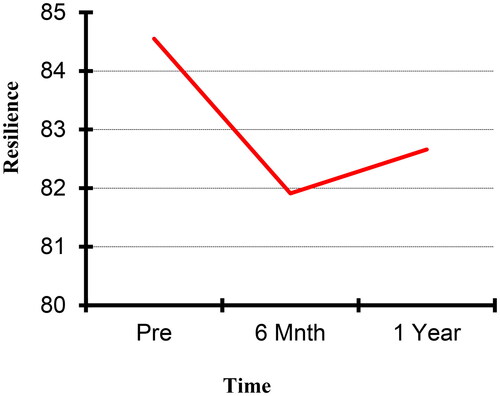

From , it can be deduced that most of the DIDS subscale scores tended to be in the higher ranges, and there were no significant differences in the identity dimensions between the three time points. The mean of Resilience showed a statistically significant difference between the three time points (F2;1124 = 27.29; p < .001) with a corresponding medium effect size (Eta2 = .046), thus indicating at least one statistically significant difference between the means over time. Bonferroni’s post hoc results revealed that the pairwise comparison of Resilience statistically significantly decreased from Time 1 to Time 2 (mean difference = 2.642; p < .001) and from Time 1 to Time 3 (mean difference = 1.889; p < .001). However, no statistically significant difference (mean difference = −.753; p = .112) was identified between the Time 2 and Time 3 measurements.

The mean for Resilience dropped from Time 1 (M = 84.55, SD = 7.34) to Time 2 (M = 81.91, SD = 8.63) and then slightly increased from Time 2 to Time 3 (M = 82.66, SD = 8.57). The findings are presented in .

To answer the second research question (i.e., Does resilience have a significant impact on identity over time?), a two-way repeated measures ANOVA was conducted. Participants were divided into two groups: High Resilience individuals (the 25% of participants with the highest scores on Resilience, n1 = 147) and Low Resilience individuals (the 25% of participants with the lowest scores on Resilience, n2 = 139). To establish whether resilience had an influence on the five dimensions of identity over time, the F statistic for each main effect was computed. Levene’s test for equality of variances was not significant, thus meeting the assumption of equal variance. The Mauchly’s Test results for the two-way repeated measures ANOVA were significant at p < .05; sphericity was assumed with the exception of Commitment Making. The two-way repeated measures ANOVA results are presented in .

Table 4. Results of two-way repeated measures ANOVA.

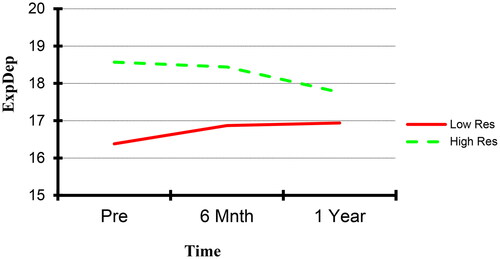

The results in indicate one statistically significant main effect on the dependent variable, Exploration in Depth (F2;568 = 2.62; p < .10) between the participants with low and high resilience. Independent t-tests were performed to determine specific differences in Exploration in Depth between the two groups of participants over the three time points. The results are presented in .

Table 5. Results of independent t-tests for two resilience groups of individuals over three time points

According to the results in , at all three time points, the participants with high resilience obtained a significantly higher mean score for Exploration in Depth than the participants with low resilience. The findings are presented in .

The scores for Exploration in Depth in participants with high resilience (intermitted line) decreased over time. This is an indication that participants with high levels of resilience tended to engage less and less in the reevaluation of the decisions and commitments that they had already made. The scores for Exploration in Depth in participants with low resilience (solid line) increased from Time 1 to Time 2, with a very slight increase from Time 2 to Time 3. This could imply that participants with low resilience struggled to make identity commitments and, therefore, kept the exploration process ongoing.

Discussion

In the current study, identity trajectories in adolescents living in under-resourced contexts were examined using the five-dimensional model developed by Luyckx et al. (Citation2013). The aim was to determine whether these identity trajectories were associated with resilience and to test the potential impact of time on identity and resilience development.

The scores for the dimensions of identity did not vary substantially across time, implying that the adolescents in this study maintained the same identity processes throughout the period of data collection. These findings do not align with findings from prior studies (Hatano & Sugimura, Citation2017), arguing that adolescence is a stage when individuals engage in a heightened exploration of various identity alternatives. Indeed, weighing and discarding irrelevant identity options is regarded as the main task of adolescents (Beal & Crocett, Citation2010; Erikson, Citation1968; Luyckx et al., Citation2013). The stable trajectories observed in the current study might reflect the effect of going through adolescence in a context that lacks resources. When adolescents face limited possibilities and options in life, they are often forced to abandon exploring alternatives and reviewing choices, resulting in substantial obstacles in developing their identities (Liu & Ngai, Citation2020). Many adolescents from under-resourced areas show decreased interest in exploration because of the desire to find a job and contribute to the family’s life. Consequently, adolescents living in such an environment tend to feel overwhelmed with identity tasks, thus hampering the exploration and commitment processes (Fomby & Sennott, Citation2013). In addition to this, the stability in identity trajectories might be the result of the short-term longitudinal design of the current study (Hatano & Sugimura, Citation2017; Luyckx et al., Citation2013).

Resilience scores fluctuated significantly. Participants showed an initial significant decrease (followed by a non-significant increase) in resilience; participants started well, but as time passed, they struggled to maintain or improve their resilience scores. This is unsurprising because resilience tends to be affected by temporal factors, such as the COVID-19 pandemic. The data collection started (Time 1) just before the strict lockdown and the difficult circumstances of COVID-19 that were experienced in South Africa (Republic of South Africa, Citation2021). Time 2 of data collection occurred when the participants experienced many changes in their lives due to COVID-19. However, the participants had regained some of their resilience by Time 3, and at this stage, a small increase in their resilience was observed. This may be due to the relaxation of the COVID-19 restrictions and the fact that some adolescents have indeed experienced positive effects due to the pandemic. These included adolescents spending more time with family, having more time for their hobbies, exercising, and resuming school and classes (Oosterhoff et al., Citation2020). The slight increase in resilience may point to the fact that adolescents manage to thrive despite hardships and exposure to contextual risks, provided they receive adequate support and protection within their environment (Mampane, Citation2014; Masten, Citation2018; Ungar, Citation2018; Van Rensburg et al., Citation2018).

Participants with high resilience obtained a significantly higher mean score for Exploration in Depth than those with low resilience, implying that (especially during the first time point) participants with high resilience were actively searching for identity alternatives (Luyckx et al., Citation2008). Over time, their Exploration in Depth tended to decrease slightly but remained higher compared to those with low resilience. Participants with high levels of resilience tended to engage less and less in the reevaluation of the decisions and commitments that they had already made. This may imply that, as time passed, these participants tended to dwell less on alternatives (Luyckx et al., Citation2008). These findings support the idea that resilience helps individuals adapt to diverse situations, including making identity-related decisions (Sevilla-Vallejo, Citation2023). Consistent with these findings, prior research studies show that adolescents who exhibit high resilience tend to be mentally stable and can continue exploring their current options and keeping meaningful commitments despite difficulties and barriers to identity formation (Schwartz & Petrova, Citation2018; Waterman, Citation2020).

Participants with low resilience showed a gradual increase in Exploration in Depth; they continued to reevaluate their current decisions, review their existing choices, and not commit to already existing identity-related options. Probably due to their low resilience, they struggled to find commitments that best fit their goals. Additionally, low resilience may suggest that this group of adolescents experienced self-doubt and considered their current commitments inadequate by gradually reviewing their existing identity-related decisions. This is consistent with findings by Luyckx et al. (2006, Citation2008), who posit that explorative dimensions of identity tend to be negatively associated with well-being. This implies that individuals in this study carried on with the Exploration in Depth, probably due to their vulnerable state of self and confusion stemming from their low resilience. These findings also support Erikson’s view that individuals with a developed identity structure are more aware of their strengths and weaknesses in their decision-making processes. Thus, the less developed their identity, the more they tend to be confused and overwhelmed (Erikson, Citation1968; Luyckx et al., Citation2008). However, the results of the current study are inconsistent with the findings of Koni et al. (Citation2019), who posit that identity exploration is associated with a stronger sense of resilience. These inconsistent findings regarding resilience and Exploration in Depth can be explained by the fact that adolescents do not follow linear pathways in their identity and resilience development. Some adolescents are able to take on positive trajectories, while others become involved in less optimal paths (Klimstra et al., Citation2013; Luyckx et al., Citation2008; Syed & Seiffge-Krenke, Citation2013). Moreover, as reported by Waterman (Citation2020), adolescents’ exploration processes can be interrupted depending on the type of environment in which they find themselves. Consequently, some end up abandoning, altering, replacing, or delaying prior commitments. In fact, according to Luyckx et al. (Citation2013), it is normal for adolescents to move back and forth in the process of exploration.

Limitations of the study

The study was conducted in three public schools in the Greater Taung Municipality in the North West province of South Africa, using non-probability convenience sampling. Non-probability sampling methods are quick and cost-effective, but the samples are not representative (Stangor, Citation2015). Therefore, the results cannot be generalized to the adolescent population living in South Africa’s under-resourced communities. The use of probability sampling techniques to obtain a representative sample is recommended.

Disadvantages in the use of self-report surveys include response biases and social desirability that influence the validity and internal consistency of measures (Foxcroft & Roodt, Citation2013). While the surveys used in this study have sound psychometric properties, the information was based purely on participants’ self-reporting and individual experiences. It would be valuable to consider involving parents and teachers who might have a different perspective on the issue at hand.

The survey instruments were administered in English, while the majority of the participants’ first language was Setswana. English was used in the study because it is the medium of instruction in schools; thus, the language participants use most frequently during reading and writing tasks. Some of the concepts in the surveys were difficult for some participants to understand. However, the researcher, being cognizant of this, encouraged the participants to ask questions to clarify any possible misunderstanding. In future, researchers should consider conducting language proficiency tests on participants prior to administering surveys. Preferably, participants should be allowed to respond in the language they feel most competent (Foxcroft & Roodt, Citation2013). Therefore, using surveys designed in the participants’ home language or using a translator during the data collection process is recommended.

In this study, some of the identity and resilience theories discussed, such as the work of Erikson (Citation1968), Masten et al. (Citation2004), Luyckx et al. (Citation2008), and Ungar (Citation2018), were developed for a Western population and not primarily for the South African context. Given the contextual factors and the historical background of the participants, these theories should be used with caution. South African research studies were included to account for the contextual understanding of adolescents (Mampane, Citation2014; Theron, Citation2019; Van Rensburg et al., Citation2018). In future research, theories with an African perspective on understanding identity and resilience should be considered.

Recommendations for future studies

The longitudinal approach to the study aimed to capture the changes in identity and resilience over time. The time interval between the phases of data collection was six months. Although time intervals can range from several hours to several weeks for change processes requiring a short period of time (Wang et al., Citation2017), it is recommended that future researchers consider a long-interval longitudinal design and follow participants for a longer period. This will better capture the long-term change processes of the measured variables. On the other hand, carrying out short-term longitudinal research might reveal other short-term shifts in identity and resilience, which might have been missed in this study because of the six-month interval.

The study was carried out during the time of COVID-19. Repeating the study when adolescents are not faced with life-threatening conditions, such as COVID-19, will provide added perspectives on the variations observed in the identity dimensions and resilience in the current study. Given the important role of contextual factors, it may be beneficial to replicate the study with participants from affluent backgrounds.

The formation of identity evolves over time and involves complex interactions with various factors. Considering this complex interplay between resilience and identity, additional studies can focus on the mediating or moderating factors in this relationship, such as the impact of specific traumatic events, personality traits, and social-cultural factors (i.e., socio-economic status, school delays, and career aspirations).

Implications for practice

The findings of the current study demonstrate the identity and resilience trends adopted by adolescents from under-resourced communities. Although the findings are not generalizable, the results can be used to facilitate new theoretical developments and policies. It is clear that having high resilience does not always imply having the capacity to actively reflect on one’s choices and evaluate current commitments. Therefore, support to adolescents is essential in helping them not only to navigate identity-related challenges but also to work on aligning their resilience and ability to make autonomous decisions in important life areas. Hence, support for adolescents from under-resourced contexts should be designed within an identity-resilience framework that encourages the development of skills such as agency, decision-making, and self-reflection. The identity-resilience framework can inform counselors, teachers, and mentors working with adolescents about the varied nature of identity exploration and how to proactively enable resilience development in adolescents living in under-resourced communities. Improving resilience can promote identity development in adolescents. Thus, community leaders and school counselors can design intervention programmes aimed at promoting adolescent resilience and identity development, with a specific focus on facilitating adolescents’ ability to face adversity. Teachers, school counselors, and social workers can promote a supportive school environment by helping adolescents develop positive adult-adolescent connections to develop their identities. For example, schools can intentionally organize different types of explorative learning experiences and career days to offer opportunities for adolescents to deepen their self-understanding and to learn about opportunities available to them. In addition, practitioners should encourage social integration and focus on strengthening peer networks, supportive parent-child relationships and positive, meaningful connections with their families and communities to empower adolescents to cope with challenges, especially given the challenging socio-economic contexts from which they hail.

Conclusion

The present study followed a longitudinal approach to advance the understanding of the relationship between identity and resilience trajectories in adolescents from under-resourced contexts. The findings emphasize the need to consider the intricate relationships between identity, resilience, and contextual factors.

Ethical approval

All procedures performed in this study involving human participants were in keeping with the ethical standards of the institutional research committee. Ethical clearance number for this study: UFS-HSD2019/1876.

Informed consent

All subjects gave informed consent for inclusion before participating in the study.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

The data supporting this study’s findings are available on request from the corresponding author.

References

- Allan, A. (2017). Law and ethics in psychology: An international perspective. Inter-Ed.

- Beal, S. J., & Crockett, L. J. (2010). Adolescents’ occupational and educational aspirations and expectations: Links to high school activities and adult educational attainment. Developmental Psychology, 46(1), 258–265. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0017416

- Crocetti, E., Branje, S., Rubini, M., Koot, H. M., & Meeus, W. (2017). Identity processes and parent-child and sibling relationships in adolescence: A five-wave multi-informant longitudinal study. Child Development, 88(1), 210–228. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdev.12547

- Das-Munshi, J., Lund, C., Mathews, C., Clark, C., Rothon, C., & Stansfeld, S. (2016). Mental health inequalities in adolescents growing up in post-apartheid South Africa: Cross-sectional survey, SHaW study. PLoS One, 11(5), e0154478. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0154478

- Divala, T., Burke, R. M., Ndeketa, L., Corbett, E. L., & MacPherson, P. (2020). Africa faces difficult choices in responding to COVID-19. The Lancet, 395(10237), 1611. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(20)31056-4

- Erikson, E. H. (1968). Identity: Youth and crisis. WW Norton.

- Fomby, P., & Sennott, C. A. (2013). Family structure instability and mobility: The consequences for adolescents’ problem behaviour. Social Science Research, 42(1), 186–201. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssresearch.2012.08.016

- Foxcroft, C., & Roodt, G. (2013). Introduction to psychological assessment in the South African context (4th ed.). Oxford University Press.

- Gittings, L., Toska, E., Medley, S., Cluver, L., Logie, C. H., Ralayo, N., Chen, J., & Mbithi-Dikgole, J. (2021). “Now my life is stuck!”: Experiences of adolescents and young people during COVID-19 lockdown in South Africa. Global Public Health, 16(6), 947–963. https://doi.org/10.1080/17441692.2021.1899262

- Govender, K., Cowden, R. G., Nyamaruze, P., Armstrong, R. M., & Hatane, L. (2020). Beyond the disease: Contextualized implications of the COVID-19 pandemic for children and young people living in Eastern and Southern Africa. Frontiers in Public Health, 8(1), 504–512. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2020.00504

- Hatano, K., & Sugimura, K. (2017). Is adolescence a period of identity formation for all youth? Insights from a four-wave longitudinal study of identity dynamics in Japan. Developmental Psychology, 53(11), 2113–2126. https://doi.org/10.1037/dev0000354

- Klimstra, T. A., Luyckx, K., Goossens, L., Teppers, E., & De Fruyt, F. (2013). Associations of identity dimensions with Big Five personality domains and facets. European Journal of Personality, 27(3), 213–221. https://doi.org/10.1002/per.1853

- Koni, E., Moradi, S., Arahanga-Doyle, H., Neha, T., Hayhurst, J. G., Boyes, M., Cruwys, T., Hunter, J. A., & Scarf, D. (2019). Promoting resilience in adolescents: A new social identity benefits those who need it most. PloS One, 14(1), e0210521. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0210521

- Kroger, J., Martinussen, M., & Marcia, J. E. (2010). Identity status change during adolescence and young adulthood: A meta-analysis. Journal of Adolescence, 33(5), 683–698. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2009.11.002

- Lebone, K. (2012). Crime and security. https://www.sairr.org.za/services/ publications/south-africa-survey/south-africa-survey-online-2010-2011/crime-and-security

- Liu, Y., & Ngai, S. Y. (2020). Social capital, self-efficacy, and healthy identity development among Chinese adolescents with and without economic disadvantages. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 29(11), 3198–3210. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-020-01833-y

- Louw, D. A., & Louw, A. E. (2020). Child and adolescent development. SunBonani Books. https://doi.org/10.18820/9781928424475

- Luyckx, K., Goossens, L., & Soenens, B. (2006). A developmental contextual perspective on identity construction in emerging adulthood: Change dynamics in commitment formation and commitment evaluation. Developmental Psychology, 42(2), 366–380. https://doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.42.2.366

- Luyckx, K., Goossens, L., Soenens, B., Beyers, W., & Vansteenkiste, M. (2005). Identity statuses based on 4 rather than 2 identity dimensions: Extending and refining Marcia’s paradigm. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 34(6), 605–618. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-005-8949-x

- Luyckx, K., Klimstra, T. A., Duriez, B., Van Petegem, S., & Beyers, W. (2013). Personal identity processes from adolescence through the late 20s: Age trends, functionality, and depressive symptoms. Social Development, 22(4), 701–721. https://doi.org/10.1111/sode.12027

- Luyckx, K., Schwartz, S. J., Berzonsky, M. D., Soenens, B., Vansteenkiste, M., Smits, I., & Goossens, L. (2008). Dimensions of Identity Development Scale (DIDS) [Database record]. APA PsycTests. https://doi.org/10.1037/t09523-000

- Luyckx, K., Schwartz, S. J., Rassart, J., & Klimstra, T. A. (2016). Intergenerational associations linking identity styles and processes in adolescents and their parents. European Journal of Developmental Psychology, 13(1), 67–83. https://doi.org/10.1080/17405629.2015.1066668

- Mal-Sarkar, T., Keyes, K., Koen, N., Barnett, W., Myer, L., Rutherford, C., Zar, H. J., Stein, D. J., & Lund, C. (2021). The relationship between childhood trauma, socioeconomic status, and maternal depression among pregnant women in a South African birth cohort study. SSM - Population Health, 14(1), 100770. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssmph.2021.100770

- Mampane, R. (2012). Psychometric properties of a measure of resilience among middle-adolescents in a South African setting. Journal of Psychology in Africa, 22(3), 405–408. https://doi.org/10.1080/14330237.2012.10820545

- Mampane, R. (2014). Factors contributing to the resilience of middle-adolescents in a South African township: Insights from a resilience questionnaire. South African Journal of Education, 34(4), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.15700/201412052114

- Marcia, J. E. (1966). Development and validation of ego-identity status. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 3(5), 551–558. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0023281

- Markovitch, N., Luyckx, K., Klimstra, T., Abramson, L., & Knafo-Noam, A. (2017). Identity exploration and commitment in early adolescence: Genetic and environmental contributions. Developmental Psychology, 53(11), 2092–2102. https://doi.org/10.1037/dev0000318

- Masten, A. S. (2014). Global perspectives on resilience in children and youth. Child Development, 85(1), 6–20. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdev.12205

- Masten, A. S. (2018). Resilience theory and research on children and families: Past, present, and promise. Journal of Family Theory & Review, 10(1), 12–31. https://doi.org/10.1111/jftr.12255

- Masten, A. S., Burt, K., Roisman, G. I., Obradović, J., Long, J. D., & Tellegen, A. (2004). Resources and resilience in the transition to adulthood: Continuity and change. Development and Psychopathology, 16(4), 1071–1094. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954579404040143

- Masten, A. S., & Tellegen, A. (2012). Resilience in developmental psychopathology: Contributions of the Project Competence Longitudinal Study. Development and Psychopathology, 24(2), 345–361. https://doi.org/10.1017/S095457941200003X

- Mastrotheodoros, S., & Motti-Stefanidi, F. (2017). Dimensions of Identity Development Scale (DIDS): A test of longitudinal measurement invariance in Greek adolescents. European Journal of Developmental Psychology, 14(5), 605–617. https://doi.org/10.1080/17405629.2016.1241175

- Ndimande, B. S. (2009). “It is a catch 22 situation”: The challenge of race in post-apartheid South African desegregated schools. International Critical Childhood Policy Studies Journal, 2(1), 123–139. https://journals.sfu.ca/iccps/index.php/childhoods/article/download/14/18

- Oosterhoff, B., Palmer, C. A., Wilson, J., & Shook, N. (2020). Adolescents’ motivations to engage in social distancing during the COVID-19 pandemic: Associations with mental and social health. The Journal of Adolescent Health, 67(2), 179–185. https://doi.org/10.1016/jjadohealth.2020.05.004

- Republic of South Africa. (2013). National Health Amendment Act, No. 12 of 2013. Government Gazette, No. 36702, 24 July. https://www.gov.za/sites/default/files/gcis_document/201409/36702gon529_1.pdf

- Republic of South Africa. (2021). COVID-19 alert system. https://www.gov.za/covid-19/about/about-alert-system

- Romero, R. H., Cluver, L., Hall, J., & Steinert, J. (2018). Socioeconomically under-resourced adolescents and educational delay in two provinces in South Africa: Impacts of personal, family and school characteristics. Education as Change, 22(1), 1–33. https://doi.org/10.25159/1947-9417/2308

- Schwartz, S. J., & Petrova, M. (2018). Fostering healthy identity development in adolescence. Nature Human Behaviour, 2(2), 110–111. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-017-0283-2

- Scott, B. G., Sanders, A. F. P., Graham, R. A., Banks, D. M., Russell, J. D., Berman, S. L., & Weems, C. F. (2014). Identity distress among youth exposed to natural disasters: Associations with level of exposure, posttraumatic stress, and internalizing problems. Identity, 14(4), 255–267. https://doi.org/10.1080/15283488.2014.944697

- Skhirtladze, N., Javakhishvili, N., Schwartz, S. J., Beyers, W., & Luyckx, K. (2016). Identity processes and statuses in post-Soviet Georgia: Exploration processes operate differently. Journal of Adolescence, 47(1), 197–209. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2015.08.006

- Stangor, C. (2015). Research methods for the behavioural sciences (2nd ed.). Wadsworth Cengage Learning.

- Syed, M., & Seiffge-Krenke, I. (2013). Personality development from adolescence to emerging adulthood: Linking trajectories of ego development to the family context and identity formation. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 104(2), 371–384. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0030070

- Theron, L. (2019). Championing the resilience of sub-Saharan adolescents: Pointers for psychologists. South African Journal of Psychology, 49(3), 325–336. https://doi.org/10.1177/0081246318801749

- Theron, L., & Van Rensburg, A. (2018). Resilience over time: Learning from school-attending adolescents living in conditions of structural inequality. Journal of Adolescence, 67(1), 167–178. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2018.06.012

- Tsang, S. K. M., Hui, E. K. P., & Law, B. C. M. (2012). Positive identity as a positive youth development construct: A conceptual review. The Scientific World Journal, 2012(1), 529691. https://doi.org/10.1100/2012/529691

- Ungar, M. (2018). The differential impact of social services on young people’s resilience. Child Abuse & Neglect, 78(1), 4–12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2017.09.024

- Van Rensburg, A., Theron, L., & Rothmann, S. (2015). A review of quantitative studies of South African youth resilience: Some gaps. South African Journal of Science, 111(7/8), 9. 1https://doi.org/10.17159/sajs.2015/20140164

- Van Rensburg, A., Theron, L., & Rothmann, S. (2018). Adolescent perceptions of resilience- promoting resources: The South African Pathways to Resilience Study. South African Journal of Psychology, 48(1), 73–85. https://doi.org/10.1177/0081246317700757

- Wang, M., Beal, D., Chan, D., Newman, D., Vancouver, J., & Vandenberg, R. (2017). Longitudinal research: A panel discussion on conceptual issues, research design, and statistical techniques. Work, Aging and Retirement, 3(1), 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1093/workar/waw033

- Waterman, A. S. (2020). “Now what do I do?”: Toward a conceptual understanding of the effects of traumatic events on identity functioning. Journal of Adolescence, 79(1), 59–69. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2019.11.005

- Lindekilde, N., Lübeck, M., & Lasgaard, M. (2018). Identity formation and evaluation in adolescence and emerging adulthood: How is it associated with depressive symptoms and loneliness? Scandinavian Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Psychology, 6(2), 91–97. https://doi.org/10.21307/sjcapp-2018-010

- Sevilla-Vallejo, S. (2023). The interplay of identity and resilience: Unleashing inner strength in the face of adversity. Mental Health & Human Resilience International Journal, 7(1), 1–2. https://doi.org/10.23880/mhrij-16000223

- Sawyer, S. M., Azzopardi, P. S., Wickremarathne, D., & Patton, G. C. (2018). The age of adolescence. The Lancet. Child & Adolescent Health, 2(3), 223–228. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2352-4642(18)30022-1

- Van der Cruijsen, R., Blankenstein, N. E., Spaans, J. P., Peters, S., & Crone, E. A. (2023). Longitudinal self-concept development in adolescence. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience, 18(1), nsac062. https://doi.org/10.1093/scan/nsac062

- Weiten, W. (2014). Psychology: Themes and variations.