ABSTRACT

Drawing upon ethnographic research in Winnipeg, Manitoba, we complicate simplistic epidemiological and sexual health discourses that position African newcomer teen girls and young women as “at-risk” for HIV/AIDS and other consequences of being sexually active. By tracing the trajectories of sexual health messages and utilizing the concept of assemblage, we seek to account for the ways in which risk is actively made and negotiated in practice by African newcomer youth. By highlighting the perspectives and experiences of participants in relationship to Canadian literature on the subject of sexual risk, culture, and education, we work to counter essentializing, racializing, and pathologizing discourses.

© 2019 Taylor & Francis Group, LLC

Attended largely by youth from various African backgrounds and organized by a settlement agency, a newcomer girls’ group took place on a bi-weekly basis in a Winnipeg public high school. Ruta, a settlement worker, was training me to run some of the meetings. This helped me, a non-African anthropologist, to make connections with African newcomer youth for my ethnographic research on how sexual health messaging—and its gendered and racialized aspects—circulates within their social worlds. On this day, a sexual health educator, Lara, was giving a presentation.

The classroom was decorated with colorful posters representing African countries. Ruta and I put out the sandwiches while chatting about the upcoming presentation. Students trickled in and found their seats. Lara arrived and introduced herself, then handed out a single piece of paper titled “Sexually Transmitted Infections Quiz.” With the classroom teacher and I watching from the back, a series of exchanges unfolded between the settlement worker, the sex education educator, and the students, with Lara asking (and answering) most of the questions, addressing students’ concerns, and correcting statements made by the teen girls that Lara deemed factually incorrect.

Lara placed a clear emphasis on “how the girls really needed this,” referring to biomedical and epidemiological information about sexually transmitted infections and unwanted pregnancies, the message to abstain or delay sexual activity, and risk-based knowledge about how sexual contact posed dangers to teen girls’ sexual health. The Sexually Transmitted Infections Quiz on 8 × 11 papers acted as a visual reminder about the “correct” information they ought to know about their bodies. When a youth raised the question, “What is HIV?” Lara fired off statistics about infection and mortality rates, highlighting the importance of women taking control of their sexual health. Her answer portrayed sexual contact as a modality of contagion, sweeping aside desire, pleasure or notions of erotic intimacy that might otherwise make that sexual transmission of HIV fathomable. She stressed the need to be communicative with boyfriends about boundaries and sexual history and, if sexually active, to practice “safer sex,” meaning regular STI testing and condom use. Otherwise, Lara cautioned, “You put yourself at risk.” One student offered her own advice, urging, “If a boy was pressuring you to have sex, you should tell him to wait.” By stressing the importance of waiting until they are “mature enough to have sex,” Lara reinforced the student’s perspective. Responding to this advice to delay sexual relations until maturity, another student retorted in an incredulous tone, “Waiting… until we’re dead?”

Where does this ethnographic encounter with a sex educator, a settlement worker, a high school teacher, and a group of African newcomer young women interacting amidst the proliferation of expert sexual health knowledge lead? Adhering to the dominant Canadian sexual health educational paradigm, Lara encouraged the youth to wait until they were mature enough to manage the risks that came with sexual activity, assumed to be heterosexual. Aside from two students who bravely answered her questions, the rest fell silent or nervously laughed at the information proffered. Lara reinforced the notion that lay knowledge was to be viewed as potentially dangerous misinformation with the warning that “sometimes friends talk and they have the wrong information.” One wisecrack, “Waiting… until we’re dead?”, was the sole resistance to her authority. As a whole, the presentation’s moralizing gendered messages surrounding young people’s bodies and sexual practices was sombre. The emphasis placed on education as the solution to grappling with the dangers of becoming sexually active—particularly for racialized populations in Canada—resulted in the performance and reproduction of sex-as-risk discourse.

* * * *

This scene from an ethnographic fieldwork locale in Winnipeg provides an entryway into examining how African newcomer youth in Canada encounter and interpret sexual health discourses—especially risk narratives about heterosexual youth sex—in their everyday lives of settlement and integration. The sexual health presentation and quiz, deemed necessary for them as a “targeted population”, was merely one incident among various other scenarios and interactions playing out in their daily lives. Rather than analyzing how African immigrant and refugee youth sexual subjectivities in Canada are shaped by dominant “risky subjects” messaging that subjugates them, we show how the young women were agentive embodied actors situated complexly within a heterogeneous configuration of bodies, actors, and expert systems that relationally produced youth sexual risk in highly gendered and racialized terms—that is, as actors through which assemblages of sexual risk congeal (Collier and Ong Citation2005; Lupton Citation2013). The expert knowledge, the authoritative epidemiological figures and pie charts, the sombre overtones of the meeting, the various actors who espouse notions of “waiting,” the correcting of lay (mis)information, and the emergent emic notions of sexual health were disparate elements that converged and coalesced around the high school girls in the making of at-risk bodies and subjects, that is, risk assemblages—where assemblages are dynamic, not static, and are about embodied processes rather than a fixed state of being (Fox Citation2011:362).

We draw on critical medical anthropology and governmentality scholarship in utilizing assemblage theory (Collier and Ong Citation2005; Fox Citation2011; Marcus and Saka Citation2006; Weheliye Citation2014). In relation to risk, Lupton understands the concept of assemblage as the “constantly changing configurations of human bodies, discourses, practices, [and] ideas” where risk is actively made (Citation2013:40). Our aim is to better understand how racialized African newcomer teen girls and young women living in Winnipeg, Manitoba are affected by sexual health messages constructing and locating them as risky subjects. Using assemblage theory, we show that despite the presence of hegemonic sexual health discourses that sought to educate youth and regulate their sexual conduct so as to avert sexually transmitted infections, pregnancies, and sexual non-normativity (i.e., all forms of sexual dis-ease), such biopedagogies were by no means the only ways in which knowledge around sexual health and sexual subjectivity was communicated and negotiated in their daily lives. The young women we spoke with simultaneously negotiated migration and settlement processes as they forged connections to African culture, spaces, and social networks within their proximity as residents of Winnipeg; these are all sites where sexual health knowledge was created and discourses circulated in relation to, and interacting with, their gendered and raced embodied presence. Furthermore, we show how hegemonic and particular risk discourses are not static and over-determining as they act upon the youth and discipline them; but rather they are aspects of sexual health messaging that exist all around and interact with the youth, converge, and become embodied in constantly changing configurations, that is, risk assemblages (Lupton Citation2013:39). The youth (and their bodies) are therefore central subjects in these risk assemblages, and are not merely materialized by powerful discursive forces.

From risk discourses to risk assemblages

Statistics from the Public Health Agency of Canada underscore disconcertingly high rates of HIV transmission in Canada for young people between 15 and 39 years of age, especially from HIV-endemic countries in Africa and the Caribbean and women of childbearing age (PHAC Citation2010a, Citation2010b, Citation2012a, Citation2012b). Public health scientists and policy makers utilize these rates to emphasize the urgent need to address sexual health awareness, particularly in Canadian cities with growing African communities such as Toronto, Windsor, and Calgary (Este, Worthington, and Leech Citation2009; Gardezi et al. Citation2008; Omorodion, Gbadebo and Ishak Citation2007). Discourses which position “key populations” (such as youth, women, and immigrants from Sub-Saharan African countries) as “at-risk” for HIV/AIDS, found in the media at both the national (Pauls Citation2017) and local (Froese Citation2018) level further reinforce this portrayal of vulnerability and public threat.

In response to the need for HIV intervention, research specifically with immigrant youth in Canada is emerging. In an Alberta study, HIV was articulated by youth as “ineffable” (Graffigna and Olson Citation2009:793), illustrating its paradoxical stigmatization and distance from the lives of some Canadian youth. The gendering of HIV risk is prominent in this body of literature, emphasizing the vulnerability of heterosexual young women in gendered power dynamics, such as negotiating condom use with male sexual partners (Larkin and Mitchell Citation2004; Baidoobonso et al. Citation2013; Dworkin Citation2005; Omorodion et al. Citation2007). Nationally youth are broadly identified as “at-risk” (Brown et al. Citation2013), particularly within the field of sexual health (Healey Citation2016). Although health scientists and scholars alike working in the field of youth and HIV in Canada resist pathologized characterizations of youth sexuality, they nevertheless tend to portray youth as somehow being not fully aware of how their own “age-related” behaviors place them at risk of bodily harm (Flicker et al. Citation2010). This perspective serves to reinforce the positionality of the expert in sexual health educational matters. What if ethnographic research did not begin with the assumption that young people are automatically at risk for negative sexual health outcomes but instead chose to focus on how sexual health itself becomes socially embedded as it gets discerned and (re)made by people in their everyday lives?

Assumptions based on statistics alone run the risk of reducing human experiences to something manageable and calculable, effectively erasing agency and resistance (Allen Citation2002:38; Gupta Citation2001). Statistics and dominant discourses that place racialized youth in categories of high risk by virtue of the underpinning racism, sexism, and ageism mean that youth sexual health can feel divorced from people’s actual lives. For example, Feven was a 22 year old from Eritrea. She laughed at the claim that heterosexual African young women are at risk for health consequences of having sex, such as contracting HIV. Yet young heterosexual women from HIV-endemic countries such as those in sub-Saharan Africa, as newcomers to Canada, are placed in a three-fold risk category, where age, race, gender, and sexuality converge (Public Health Agency of Canada Citation2010a, Citation2010b, Citation2012a).Footnote1 Feven scoffed at this notion, replying “At risk? Really? I think anyone can get it.”

While holding in tension the ethnographic imperative to understand HIV risk in its complexity in people’s experiences and social worlds, identified almost 20 years ago by Richard Parker (Parker Citation2001) with the need to challenge the racialized categorization of African youth as “risky,” we pursue a line of analysis that conceptualizes members of a targeted population as entangled in risk assemblages. As we alluded to above, assemblages are “the product of multiple determinations that are not reducible to a single logic” (Collier and Ong Citation2005:12). While assemblage theory has been utilized in Science and Technology Studies (STS) in relation to Actor-Network-Theory (ANT) (Latour Citation2005), we use assemblage through an anthropological lens to inquire into the formation of subjectivity rather than scientific knowledge. Broadly speaking, ANT draws attention to the tying together of disparate and both human and nonhuman actors through institutional and social practices in the creation of scientific facts (Nguyen Citation2005:126; Sayes Citation2014:135), with an emphasis on nonhuman agents (e.g. retroviruses, Sayes Citation2014:141). For our research, we follow Nguyen’s cultural anthropological use of assemblage—examining how practices, technologies, and knowledge shape subjectivity (126), rather than focusing our attention on the agency of nonhumans as an ANT assemblage framework tends to do.

We understand assemblages to not exist and operate independently from people but through people and their embodied social relations, reflecting how risk is constructed relationally and in practice. Together, the epidemiological risk discourses targeting African immigrant youth, the pathological framing of youth sexuality as inherently risky, the construction of youths’ bodies as in continual need of intervention, and the ineffability of HIV are underpinning forces that lead to the creation of (sexual) “risk assemblages” (Lupton Citation2013) in which immigrant and refugee youth are complexly entangled, like the embodied affective fulcrum in a constantly changing formation. We aim to disrupt the normalizing, essentializing epidemiological profiles that cast certain bodies as “at-risk” and “vulnerable” by considering instead the profoundly productive force of risk discourses in the formation of subjectivities and bodies. In short, we consider how social actors become caught up in and re-assemble risk assemblages without ever being fully determined by them.

Methods

The largest city in the Prairies with a population of 700,000, Winnipeg is demographically diverse, including many immigrants and a large urban Aboriginal population. Starting in the 1960s and escalating in the 1990s, new trends of refugee-classified individuals and families arrived from Eritrea, Ethiopia, Somalia, and numerous other African countries. In the mid-2000s, the numbers again grew significantly. A wide range of ethno-racial groups from various African countries, of which Ethiopia contributes the largest group, make up approximately 10,000 African residents in Winnipeg, with roughly half of them arriving within the past five years (figures for 2011) (Ervick-Knote and Garang Citation2015). The number of African and Middle Eastern immigrants steadily grew from 2006 to 2015 (Citizenship and Immigration Canada Citation2015). This trend continued, with the number of Eritreans immigrating to Manitoba jumping from 3.5 percent in 2014 to 8.4 percent in 2016 (Province of Manitoba Citation2017). African immigrants in Manitoba tend to be younger than other immigrant groups, and with many settlement services as well as cheaper housing located in the inner core, a concentration of youth from different African backgrounds reside downtown.

In 2013, anthropologist Susan Frohlick in partnership with a local sexual health education organization, a neighborhood youth organization, an immigrant and refugee support organization, a medical anthropologist (Robert Lorway), and two graduate students began an ethnographic community-based research project looking at the experiences and negotiations of sexual subjectivities and sexual networks for African immigrant and refugee youth living in the heterogeneous inner city. HIV risk was an overarching concern while the project’s main aim was to contextualize HIV risk within a broad range of experiences that emerged from youths’ stories about their settlement. Over five years, the team carried out ethnographic interviews and other ethnographic strategies in downtown Winnipeg with 80 youth from a range of backgrounds, countries of origin, and migration paths to Canada. They were between 15 and 25 years old, mostly cisgendered, an equal number of men and women, one transgender person, predominantly heterosexual, and six LGBTQ participants. Members of local African communities also took part as research coordinators and peer researchers. I (Odger) was one of the graduate students and carried out ethnographic fieldwork for seven months in downtown Winnipeg. My research focused on the role of sexual health messaging in the lives of young women between the ages of 15 and 25 years old and, more specifically, how young women react to and negotiate multiple discourses related to sex that position them as “at-risk” (Odger Citation2015).

For my fieldwork I volunteered, helping with homework and group facilitation. Participant-observation in these spaces helped me understand the everyday lived places and social relations newcomer youth inhabited. This included hanging out in high schools and community organizations with programs for African youth. These programs were created to open a space for discussions around dating, hygiene, domestic violence, youth rights, and gender norms, as well as for recreational activities, especially soccer and basketball.Footnote2 Services for immigrant youth included sex education programming that reflected the state’s concern with HIV and other sexual and reproductive health issues. There is some sense in which these newcomer youth came to see themselves, in the diaspora, as forming an “African” peoplehood (differently perhaps than when they are living in their countries of origin) as they confront similar challenges around becoming “Canadian” (Frohlick, Migliardi and Mohamed Citation2018). With the increasing number of African youth in downtown Winnipeg intersecting with a growing immigration and refugee service industry, sexual health discourses took hold in their everyday lives in this context.

Within the larger project, my project sought to find out how young women come across sexual health messaging in their daily lives, such as high school classes for immigrant girls, not unlike the one described in the introduction, sex education workshops, television and other media, or with families or friends. Frohlick and I devised a strategy whereby I could trace the women’s emplaced, culturally located, and random encounters with sexual health messaging. As one facet of the ethnographic approach overall, we refer to this main method as “sexual health messaging trajectories,” both a methodology and analytical lens, which dovetails with assemblage theory. Sexual health messaging trajectories serve as a methodological strategy for data collection, rooted in global, transnational, and multi-local ethnographic sensibilities that follow subjects and trace material objects (see Appadurai Citation1986; Marcus Citation1995), such that we can better understand the specific “relations, knowledges, technologies and affects” that impact subjectivity (Raikhel and Garriott Citation2013:10). Trajectories are, simply, paths of meaning and knowledge that ethnographers attempt to follow, in our case, tracing the perspectives and experiences of our interlocutors in relation to anything that imparts what they take to be a message about sexual health. However, we also use trajectories conceptually, to reflect not only a pathway but also the forward movement or projectile track of something in motion. This allowed us to “track” particular messaging in each participant’s life, and provided a conceptual apparatus, which enabled us to keep an analytical view on how pathways of sexual health information, moral codes, and narratives were contingent and influenced by each other in a kind of forward “thrust” or trajectory.

In using trajectories, we were able to examine the movement of our interlocutors within various circulations of heterogeneous sexual health discourses. Within these new contexts risk assemblages are actively created for and through immigrant youth. Sexual health messaging trajectories refer to the pathways along which messages and messaging about sexual health promotion and precaution came to the attention of key informants. In this way, the participants were not passive recipients of risk messaging or subjugated “risky subjects.” We asked participants to collect sexual health messages they encountered, as we explain below, and then we connected the messages to people’s social locations and diverse realities, a methodological approach that gives credence to the “social life” of documents and information. This approach allowed an analysis of explicit and implicit discourses, not only of what was said but also of the context and pathways in which these messages were circulated and enfolded around the young women and girls as forming risk assemblages.

The tool consisted of several steps. First, an initial meeting with participants in cafés or libraries facilitated rapport. Next, ethnographic interviews elicited details about participants’ migration to Canada, and discerned the meanings they ascribed to the notion of “sexual health.” During this meeting I went over informed consent, explaining the voluntary nature of their participation and the benefits and risks of participating, seeking their verbal consent, and explaining the honorarium offered (two bus tickets and twenty-five dollars cash) as a way to show appreciation for the time they spent with us.Footnote3 At that meeting, the subsequent step in the research strategy was explained: this entailed participants taking approximately two weeks to collect sexual health messages they came across in the course of their everyday lives. While examples of sexual health messaging were provided when asked, the types of messages were left broad so as to encourage participants to decide for themselves what they considered to be a sexual health message.Footnote4

The third step was a two-week period where participants collected their sexual health messages, sometimes in communication with the researchers and sometimes not. During this time participants occasionally sent me text messages, asking for clarification on what they should be doing. However, most participants collected materials without contacting us. Following the two weeks, we met with them again so that they could share and talk about the messages they had collected. Each participant was asked about the content of the message (some of them brought images on their phones or photocopied). They also were asked to explain the contexts in which they found messages, and to reflect on the meaning of the messages.

A research coordinator and a peer researcher from the Winnipeg Eritrean community played important roles in recruitment through their social networks and professional contacts within local African communities, and they obtained informed consent from mothers of minor-aged participants. Because one participant had been in Canada only several months and was more comfortable speaking in Tigrinya than English, the peer researcher acted as a translator during interviewing.

While ten participants were interviewed, six participants completed the entire sexual health messaging trajectories strategy. We had multiple meetings with them over an extended period of time, which allowed for a depth of insight beyond single interviews. The remaining four participants did not participate after the preliminary interview or second meeting, partly because of their busy schedules and parents’ regulation of their activities. In addition, the sensitive topic of sexuality and moral underpinnings of sexual health may have influenced their decisions not to participate.

The six young women who fully participated in the sexual health messaging trajectories strategy ranged in age from 15 to 25 years old. Their ethnic, racial, and class backgrounds also varied, although the majority identified as Christian. Their length of time in Canada varied from a few months to six years (average three years). Countries of origin were Eritrea, Ethiopia, Mauritius, and Rwanda. A few of the ten participants had spent months or years in Kenya or Uganda as asylum seekers prior to coming to Canada. Dehab, Candace, and Semira were high school students. Feven, Cheyenne, and Gretah were university students.Footnote5

Below we highlight how and where the participants read, heard, or otherwise came across sexual health messaging. Although high school and university were key settings where sexual health messages appeared in their lives, other everyday spaces such as television watching and family households were also central.

Ubiquity

“In Canada, it’s everywhere and nowhere” – Feven

Aged 15 and 16 respectively, respectively, Semira and Candace were friends and attended high school in Winnipeg together, along with other African youth (). Candace was born in Ethiopia, and, sponsored by her mother, immigrated to Canada with her older brother when she was 12. She was happy that her family was together again, even if her mother had to work long hours to support them. Candace had not seen her mother for several years; after her parents separated, her mother lived in Egypt for five years before coming to Canada. Semira was born in Kenya to Eritrean parents and lived in Kenya before coming to Canada at age 11, also as refugees through family sponsorship. As the oldest of five siblings, she helped her mother take care of the children when she wasn’t in school, while her father had moved to another province for better job prospects. Both families attended an Orthodox Christian church, which the girls jokingly referred to as “the Ethiopian one.”

Figure 1. Youth outside a high school in Winnipeg. Photo taken by a research participant for a social media project where participants provided us with images that represented their lives in Winnipeg (africanyouthts.com). Used with permission from the participants appearing in the photo.

Candace and Semira were close friends and felt comfortable being involved together in the research. They were shy in the early meetings with us but seemed to gain confidence in one another’s presence. Youth were always given the option to be interviewed individually or with others to ensure they felt safe talking about sexuality with researchers and safe travelling to and from the interview. We also wanted them to participate in the research in a way that was most compelling, or interesting, to them.

The pathways in which these young women came across the messaging began “back home,” in reference to their childhoods in Ethiopia and Kenya; the trajectories did not simply start when they arrived in Canada. When asked when they first started hearing about sexual health, Candace said students began talking about it in elementary school. Their teachers were hesitant though, and had only provided “basic things, like how it’s done, and how it’s gonna be in a safe way, [and] that kind of stuff.” The sexual health education Candace and Semira received in their childhoods was premised on notions of sex as reproductive, entangled with the idea that providing too much information to youth will lead them to engage in sexual activity before they were ready for parenthood.

In Winnipeg, their everyday routines revolved around two spaces—their high school and their respective homes. They went to school, returned home to watch television for a couple of hours before doing homework, sometimes babysat younger siblings, and went to bed. Candace also had a part-time job, had a cell-phone, and occasionally went to the mall. In these daily geographies, they came across sexual health messaging frequently as Semira explained: “Everywhere! On the buses, at the school… everywhere.” When asked about the content of the messages, though, nothing in particular had come to their minds. They couldn’t say how sexual health was defined in their health classes at school.Footnote6 In their social worlds, the messaging was ubiquitous but the content was hazy or varied so much across spaces that no one message coalesced too strongly, except to “be safe,” implying the potential risks sexual activity posed to them.

Dehab was born in Eritrea and arrived to Canada from the Sudan after living there for two years with her mother and younger sister. Her father had emigrated to Canada years before them and brought them to Winnipeg through the family sponsorship program. Dehab had migrated to Winnipeg a few months before we interviewed her. At 18 years old, she attended a public high school in Winnipeg. Education was the most important aspect of her life, and her days were spent travelling between home and school, occasionally visiting organizations that offered programming for newcomer youth.

Dehab’s narrative served to locate and historicize her experiences in relation to sexual education and HIV/AIDS messaging—discussing the differences in the various cities in which she had lived during her migratory journey to Canada. In Eritrea, sexual education workshops were conducted in the seventh grade. Dehab believed the emphasis on safer sex was important since these kinds of things were not typically discussed at home. She contrasted her early experiences with sexual education to her time in the Sudan, when such matters were not discussed, particularly in public. Dehab felt that Winnipeg was not lacking for information on sexual health, citing science classes and access to clinics, but she felt that in comparison to Eritrea, Canada did not have many public messages pertaining to HIV/AIDS. As a newcomer to Canada, she seems to have felt both an omnipresence of sexual health messaging and a conspicuous public absence in contrast to back home.

While the high school students (Candace, Semira, and Dehab) spoke about the relative availability of sexual health messages in Winnipeg, these were largely a product of thinking about the future. They were not involved in a romantic or sexual relationship when we interviewed them, and for them sexual health was a potentiality that one needed to plan for through accessing the right kinds of information and services. In contrast, the university students linked the ubiquitous safer sex message to monogamy. When asked how she would define sexual health, Cheyenne, a 22 year-old international student from Mauritius who identified as African and Mauritian, said:

For me personally, I don’t believe [the rule] about no sex before marriage or anything like that. So it’s more about maintaining your sexual health, getting checked, not having STIs, [and] asking your partner if he’s clean. For me, that’s sexual health. And not having too many sexual partners at a time…Footnote7

At 25 years old, Feven, an Eritrean woman from Kenya, participated in the sexual health messaging strategy together with Cheyenne. She also linked sexual health to monogamous—and trusting and communicative—relationships:

I would say [sexual health] is being more aware of the sexual diseases around. I guess being true to your partner, [if] you’re sleeping with that person, and that person is true to you. Unless one of you has an STI or an STD, it wouldn’t come to you, right? So, I guess [sexual health means] being more open.

Cheyenne spoke about the relative availability of sexual health information in Mauritius, describing workshops held in a central community center. Upon immigrating to Canada three years earlier, first living in Toronto and then Winnipeg, she observed how information pertaining to STIs was more visible than HIV/AIDS specifically. This led her to believe that these types of infections were a “problem” in Winnipeg, and she had overheard students on campus discussing how they contracted and treated various infections. While Feven emphasized monogamy as key to sexual health, Cheyenne spoke of clinical aspects of sexual health, which involved getting tested regularly for sexually transmitted infections. Despite the different emphasis, both women offered meanings of sexual health associated with knowledge about the risk of disease that could be applied to their bodily self-regulation, in order to remain “clean” and free from sexually transmitted infections.

In this section, we have shown how migration trajectories converge with pathways in which our interlocutors come across sexual health messages when they are settling into Canada as gendered African refugees and international students. The university students compared their teen years in African towns and cities before arriving in Canada where sexual health discourses had taken different forms, including international HIV prevention campaign radio shows broadcast in villages, and abstinence messages preached by parents and grandparents. Once in Canada, they perceived that sexual health messaging focused on a wider range of sexually transmitted infections rather than HIV and pregnancy prevention, and that such messages were ubiquitous (“everywhere”). In consequence, sexual health messaging for them in Winnipeg was hard to pinpoint in practice.

Events and incidents

Utilizing trajectories to trace both the circulation of sexual health messages in Winnipeg and the ways in which participants’ migratory pathways shaped how they understood the risks sex posed to their sexual health, key moments emerged from the narratives. We understand these key moments as important events and incidents in which participants encountered both implicit and explicit discourses of risk in relation to sex. In what follows, we discuss a Winnipeg Regional Health Authority poster, a high school workshop, and an American television program, in order to illustrate the multiplicity of sources and formats that sexual health messages take in participants’ lives. This reinforces a notion of the dangerousness of sex as a part of an emergent risk assemblage.

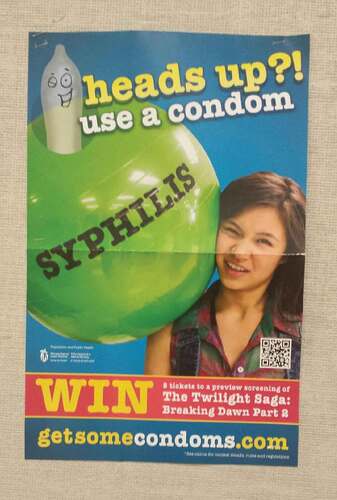

Candace and Semira told us about a poster pinned to their high school’s bulletin board. This poster is a part of the ‘Heads up!? Use a condom” campaign created by the Winnipeg Regional Health Authority, where it was posted at bus stops, high schools, and other public venues throughout the city (). This campaign encourages youth to use condoms to reduce the spread of STIs. Semira explained that while she was not currently thinking about beginning a sexual relationship, the campaign message made her think about what she would need to do in the future in order to maintain her sexual health (i.e. practicing safer sex): “I feel like before [I came to Canada and took part in the sexual education system], I probably wouldn’t [have noticed] … but realizing that it can be a long term thing if you do have HIV or AIDS, I could probably start looking into it, and [be] more careful.”

Figure 2. One sexual health message that participants, Candace and Semira, encountered during our research with them. Candace took the photo, of a Winnipeg Regional Health Authority poster, from a bulletin board at their high school. It serves here as an event in a risk assemblage.

The expert knowledge utilized in this particular campaign poster—as a part of a risk assemblage—compelled Semira to pay some attention to HIV prevention messaging targeting the youth population in Canada. This illustrates how our sexual health messages in Winnipeg affected our interlocutors as they held sway over Semira, who had chosen to delay intimate relations until she was older yet felt the campaign nevertheless applied to her. In Semira’s case, her parents exerted little influence over her decisions about dating and sex (her father lived in another province and her mother was simply uninterested), which partially explains her attentiveness to public discourses on youth sexual health. The poster serves an event—a catalyst that resulted in Semira reflecting on her potential vulnerability to STIs and HIV/AIDS.

In addition to city-wide poster campaigns, the participants mentioned workshops as significant events for learning about sexual health. Dehab excitedly discussed a “safer sex” workshop she attended with one of her friends shortly after moving to Winnipeg. The workshop was gender segregated and took a lecture-and-discussion format co-run by both teachers and students. Dehab mentioned a question box where students could anonymously pose an issue for the class to discuss. One question stood out in her memory, where someone sought advice about how to navigate a romantic relationship with someone who wanted to begin a sexual relationship. The workshop staff provided their own example of what could happen if a girl was pressured into having sex, citing a case where a girl became pregnant and had to drop out of high school. Through linking teen sex, heteronormativity, and pregnancy, the workshop reinforced the conceptualization of (hetero-) sexual activity as one that posed serious and gendered risks.

The public health poster and the safer sex workshops were identified by participants as events where sexual health messages were communicated. Yet popular culture also was a space where implicit messages around sex and risk circulated. American television shows, such as “Teen Mom” and “Sixteen and Pregnant,” were named by Semira and Candace as prime examples of key moments where their parents used the programs to indirectly communicate specific values to their daughters about sex and relationships. Candace recalled how when she came home and saw her mother had the television tuned into one of these shows, she would try to escape to her room. This did not always work, as her mother would call her back into the living room in order to express her frustration with reality shows glamorizing teenage pregnancy and motherhood. Drawing on the messages conveyed in these reality television programs, the mothers utilized the characters starring in the television shows to warn their daughters of the consequences of premarital sex.

Through analyzing three distinct events and incidences, we emphasize multiple ways in which risk assemblages became a part of the women’s everyday lives as newcomers in Winnipeg. In different ways the public health poster, the safer sex workshop, and family discussions surrounding television programs all led to the effect that sex posed a risk to youth and that correct information could lessen the risk. Furthermore, these examples show the contingent, unpredictable ways in which assemblages operate, reflecting women’s agency as social actors. By this we mean that assemblages do not unilaterally and predictably impose a force or influence over women’s actions. Instead, they allow us to see how people are agentive actors in the production of risk and in the processes by which risk narratives are made through and around embodied subjects and social relations.

Racialized bodies

When she was 19, Gretah travelled from Rwanda to Winnipeg as an international student. Two years later when I met her, she spoke passionately about her growing interest in feminism and gender studies. At one point during our interview, she explained that before she came to Canada, she thought of the “West” as being a place where there was a lot of wealth and privilege. It was not until she moved to Winnipeg when she learned this was not the case, as inequality and racism are very much present. In particular, she saw the downtown core as a space where racist discourses occurred with frequency. While she recognized that different groups—particularly racialized ones—could be considered vulnerable due to social and economic inequalities. Gretah did not understand sexual health risk, such as contracting HIV, to be an inherent quality attached to race or ethnicity. Rather, she understood vulnerability to poor health as a result of systemic racism. In their recent article on racialized diabetes risk in the United States, Bell and colleagues emphasize the need to take seriously the “consequences of labeling some groups of patients as inherently ‘at risk’” (Citation2018:3), and this is something Gretah and many of the other young women we spoke with grappled with in their narratives.

By highlighting Gretah’s critical engagement with racializing discourses that homogenize an entire community, we can begin to unpack how young African women objected to the positioning of target populations as at-risk/risky by institutions such as the PHAC. Here we draw our attention back to the ways in which particular bodies—always racialized, gendered, and aged—become entangled in sexual health discourses in relation to risk. Rather than obscure, as biomedical narratives that categorize racialized populations as “at-risk” for sexually transmitted and other infections can do (Bell et al. Citation2018), we utilize the youths’ narratives to draw attention to the racialization that adheres to certain entities and “human physiology and flesh” within risk assemblages (Weheliye Citation2014:50).

The idea that Black African newcomers were more at-risk for negative sexual health outcomes was one that participants did not accept wholesale, and they negotiated this discourse in complex and nuanced ways. While discussing the sexual health messages they encountered, both Candace and Semira spoke to the importance of using protection when having sex, otherwise, in their words, “you might be putting yourself at risk.” In this formulation, having the right kinds of information and practicing safe sex was conceptualized as one way for young people to deal with the risks of sex. However, they did not see how a person would automatically be assumed to be more at risk than any other group by virtue of coming from an endemic country or particular ethnic/racial heritage. Instead, they shifted the location of risk away from individual place-and-raced bodies to the structural element of education. They discussed with us a website, found during the sexual health messaging trajectories activity, featuring an organization that provided educational services to newcomer communities. Both Candace and Semira thought targeted services were beneficial, connecting access to the right kinds of information to their risk level while dismissing any links to race. For them, being a newcomer was the crux of the issue, not being Black or African. However, they thought young adults were particularly subjected to the risk of negative consequences associated with sex; Semira invoked the idea that peer pressure and popularity might play a role in becoming sexually active, particularly for Canadian white youth.

In this exchange, the contingent, contradictory effects of risk assemblages became apparent in the way Candace and Semira interpellate racialized newcomer youth into notions of risk. On the one hand, they contested the idea that racialized groups could be identified as “at risk.” On the other hand, they agreed with the logic behind youth falling under one risk category due to their perception of young people as impulsive and lacking sexual health education. While Candace and Semira did not negate discourses of risk in relation to youths’ sexual practices, they distanced themselves from racialized discourses that categorize and naturalize certain “human physiology and flesh” as naturally pathological bodies, linked to countries of origin and race, as more at-risk than any other group (Weheliye Citation2014:50).

Semira, Candace, Dehab, and Gretah all understood young people to face the likelihood of pregnancy and STIs for a variety of reasons. Being “at risk” was a presumably natural stage in development for youth, where “risk” was emphatically entangled in the seemingly ever-present dangers of sexual practices. Dehab felt that it was better to teach youth who were going through puberty about the hazards sex posed and to provide them with factual information, that is, how they could reduce sexual risk. Yet while the idea of all sexually active youth as “at risk” is one that the participants wholeheartedly accepted, they repositioned themselves in relation to discourses that positioned them to be more at risk because of their race/ethnicity background. They were not the ones likely to be pregnant or contract a disease; instead they regarded other young people—and specifically white Canadian-born students attending their high school—who were engaging in sexual relationships as the risky ones.

The placement of the categorization of “at risk” onto white Canadian youth through a moralizing discourse served to reposition the fixing of Black immigrant youth bodies as the pathology and vectors of disease. We have argued that newcomer African youth hold a complex and sometimes conflicted relationship with dominant discourses of sexual health messaging, and in particular HIV prevention messaging, surrounding their bodies. As social actors with capacity to exercise agency, they negotiated a wide array of coalescing discourses, some more dominant than others. At the same time, the young women were the very fleshy subjects named by hegemonic risk assemblages that were, as our interlocutors articulated, intensely racialized. As we discussed earlier in this article, Feven was particularly shocked by the assertion that PHAC would categorize one group as more “at risk” than others. From her perspective, anyone who was engaging in sexual activity might suffer negative sexual health consequences. In the ethnographic details above, contradictions emerged—that is, how sexual health is simultaneously vague to youth and germane to their subjectivity, and how they acquiesced to the categorization of all youth as being “at risk” for HIV infection while also resisting the categorization of Black and/or African youth as particularly “risky.”

Lupton (Citation2013:106) has argued that the framework of governmentality allows risk to be seen as calculable and governable; epidemiological risk factors are seen as moral technologies that regulate and discipline citizens (118). She critiques governmentality though for overlooking how risk-related discourses may be taken up, negotiated, resisted or “reassembled” by differently positioned subjects (Lupton Citation2013:143; Lorway and Khan Citation2014). By looking at subjectivity, we suggest that risk discourses are not merely strategies that foster compliance in populations (Gupta Citation2001) but instead draw attention to the social contexts in which understandings of and responses to risk emerge. By utilizing the concept of assemblage and tracing sexual health messages as trajectories, we are in better position to illustrate the complex, contradictory, socially located, and culturally heterogeneous ways in which risk operates in the lives of our participants, particularly in relation to race.

Conclusion

“What do they think? That we have never heard about these things before coming in Canada?” —Selam

Ethnographic insights into the nature of meanings given to “sexual health” by teenagers and young adults from Eritrea, Ethiopia, Kenya, Mauritius, and Rwanda who had been living in Canada six years or less reveal complicated encounters with and interpretations of sexual health discourses. Each of the participants came to Canada through different migratory pathways and had different settlement experiences tied to their familial and social relationships. Their biographies and perspectives moved them along trajectories wherein they came across a variety of sexual health messages in the spaces and social networks they occupied during processes of settlement. Assuming that they would come across messages and take up messaging in the exact same way among themselves or among other Canadian youth, or that they would take them up at all would be incorrect. Additionally problematic is the assumption that newcomer youth are lacking knowledge when it comes to sexual health and HIV/AIDS. By examining the appearances of sexual health messages that had surfaced in the lives of participants in predictable and unpredictable ways through the methodology of trajectories and the theoretical lens of assemblage, we are able to show how the notion of risk, which is so heavily imbued in all of the sexual health messaging they came across, was nevertheless hardly over-determining.

We identified three trajectories of sexual health messaging in which African immigrant and refugee young women encountered different formations of messaging while living in Winnipeg and traveling between home, school, and university: trajectories of ubiquity, of events and incidents, and of racialized bodies. The first trajectory traced how multiple factors—particularly immigration—shaped how and where interlocutors understood the concept of sexual health, and the visibility of specific issues (i.e. HIV/AIDS, pregnancy, STIs) was largely dependent on the context, emphasizing the everyday nature of sexual health messaging. The second builds upon this ubiquity of sexual health messages by focusing on key moments in their lives that illustrate how risk is actively made in concrete events and incidents along trajectories. The last examines how sexual health messages targeting particular bodies are negotiated and re-worked through the experiences and perspectives of young newcomers seeking belonging in places of settlement always against the way they are racialized in the city of Winnipeg.

Epidemiological and public health reports categorize African, Black, and Caribbean populations, persons between the ages of 15 and 39, and women of childbearing age as being key HIV risk groups and vulnerable to infection (Public Health Agency of Canada Citation2010a, Citation2010b, Citation2015), and it would be reasonable to proceed with this information as a given. However, we utilize ethnographic data to trouble simplistic understandings and applications of epidemiological statistics that are unable to account for the complicated ways in which social actors negotiate, resist, and shape these risk assemblages, through spatial and temporal pathways of both sexual health messages and participants’ narratives. By analyzing a few brief examples of how risk was actively made in practice in our fieldsite in Winnipeg, Canada, through the concept of assemblage, we begin to attend to the complexities of negotiating and thinking about one’s sexual health. We have aimed to ethnographically demonstrate how young racialized immigrant and refugee youth “do not respond like computers to stimuli, but in complex and sometimes unpredictable ways…[with] the capacity to make choices and act on the world” (Fox Citation2011:361). Through our in-depth exchanges with the young interlocutors, their knowledge and self-awareness became evident, challenging stereotypes of misinformed, naïve immigrant youth circulating within local networks of service providers. Our purpose is not to highlight African newcomer young women’s need for education, as we instead complicate simplistic risk discourses and illustrate the multiple ways knowledge around the body and sexual health are communicated. While we do not ignore HIV vulnerability facing some young people of African heritage in Winnipeg, our purpose has been to show the limitations of discursive constructions that associate sexual risk, and in particular the risk of contracting HIV through sexual contact, with population categories, in our case, with heterosexual female youth from sub-Saharan African countries who immigrated to Canada. Categorized as risky subjects, our interlocutors disassociated themselves from some of these categories while associating with others, yet again placing themselves in risk narratives quite different to those authoritative ones of the Public Health Agency of Canada. In this sense, we see them as re-assembling risk as they actively bump up against and interact with risk discourses, institutions, entities, and networks in their local and translocal social worlds and subject formations. The context in which identifications of risk take place can usefully be interrogated to better understand these vulnerabilities as complex and nuanced.

Acknowledgments

We thank the Immigrant Refugee Community Organization of Manitoba and Sexuality Education Resource Centre for their generous partnerships. The research could not be carried out without the dedication of peer researchers and research coordinators, including Selam Gheybrohannes, Winta Michaels, Huruy Michael, Weyni Abraha, Adey Mohamed, and the late Yoko Fwamba. Most of all, we acknowledge the research participants who cannot be named but to whom we are most grateful.

Supplemental data

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed on the publisher’s website.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Allison Odger

Allison Odger is a medical anthropologist and a Social Anthropology PhD candidate at York University.

Susan Frohlick

Susan Frohlick is a cultural anthropologist and professor of Anthropology and Gender and Women’s Studies in the Community, Culture and Global Studies Department at the University of British Columbia, Okanagan.

Robert Lorway

Robert Lorway is a medical anthropologist and associate professor in The Centre for Global Public Health and Community Health Sciences at the University of Manitoba. He holds a Social Science and Humanities Research Council of Canada Research Chair in Global Intervention Politics and Social Transformation.

Notes

1. According to the Public Health Agency of Canada, youth accounted for 26.5 percent of all HIV-positive test reports (Public Health Agency of Canada Citation2010a), women represented an increasing proportion with 26.2 percent (PHAC Citation2010b), and individuals from endemic countries (while only representing 2.2 percent of the Canadian population) account for 14 percent of HIV-positive test reports (PHAC Citation2012a).

2. We acknowledge our partnership with these organizations, Immigrant Refugee Community of Manitoba and Spence Neighbourhood Association, who welcomed us into their spaces and programming so that we could spend time with and gain rapport of youth as well as shared knowledge about programming for African youth in Winnipeg.

3. Youth peer researchers advised us on the informed consent process and honoraria amount.

4. We always made it clear to participants that we were not sexual health experts or sexual education providers and that we were not looking for “correct” or objective answers or for anyone to disclose any personal health information including HIV status.

5. All participants are referred throughout by pseudonyms to maintain anonymity and confidentiality.

6. Language translation played a role here, as in Tigrinya, for example, no word for sexual health exists.

7. Interview excerpts have been edited to remove words such as “like” and “um” to fairly represent the linguistic capacity of participants.

References

- Allen, D. 2002 Managing Motherhood, Managing Risk: Fertility and Danger in West Central Tanzania. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press.

- Appadurai, A. 1986 The Social Life of Things: Commodities in Cultural Perspective. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Baidoobonso, S., G. R. Bauer, K. N. Speechley, and E. Lawson 2013 HIV risk perception and distribution of HIV risk among African, Caribbean, and other Black people in a Canadian city: Mixed methods results from the BLACCH study. BMC Public Health 13(1):1–17. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-13-1.

- Bell, H., F. Odumosu, A. Martinez-Hume, H. Howard, and L. Hunt 2018 Racialized risk in clinical care: Clinician vigilance and patient responsibility. Medical Anthropology 38(3):224–238. doi: 10.1080/01459740.2018.1476508.

- Brown, S., J Shoveller, C. Chabot, and A. D. LaMontagne 2013 Risk, resistance, and the neoliberal agenda: Young people, health, and well-being in the UK, Canada, Australia. Health, Risk & Society 15(4):333–346. doi: 10.1080/13698575.2013.796346.

- Citizenship and Immigration Canada 2015 Facts and Figures 2015: Immigration overview: Permanent residents. Ottawa, ON: Immigration, Refugees and Citizenship Canada.

- Collier, S. J. and A. Ong 2005 Global assemblages, anthropological problems. In Global Assemblages: Technology, Politics, and Ethics as Anthropological Problems. A. Ong and S. J. Collier, eds. Pp. 3–21. Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing.

- Dworkin, S. L. 2005 Who is epidemiologically fathomable in the HIV/AIDS epidemic? Gender, sexuality, and intersectionality in public health. Culture, Health & Sexuality 7(6):615–623. doi: 10.1080/13691050500100385.

- Ervick-Knote, H. and R. Garang 2015 Housing and Affordability: A Snapshot of the Challenges and Successes for Winnipeg’s African Community. Winnipeg: The University of Winnipeg Institute of Urban Studies.

- Este, D., C. Worthington, and J. Leech 2009 Making Communities Stronger: Engaging African Communities in a Community Response to HIV/AIDS in Calgary. Final Report. Calgary: University of Calgary.

- Flicker, S., A. Guta, J. Larkin, S. Flynn, A. Fridkin, R. Travers, J. D. Pole, et al. 2010 Survey design from the ground up: Collaboratively creating the Toronto teen survey. Health Promotion Practice 11(1):112–122. doi: 10.1177/1524839907309868.

- Fox, N. J. 2011 The ill-health assemblage: Beyond the body-with-organs. Health Sociology Review 20(4):359–371. doi: 10.5172/hesr.2011.20.4.359.

- Froese, I. 2018 6% of Manitobans got HIV tests last year and that’s not enough, says local organizer of national testing day. CBC News, June 27. https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/manitoba/manitoba-national-hiv-testing-day-second-highest-rates-1.4724297

- Frohlick, S., P. Migliardi, and A. Mohamed 2018 “Mostly with white girls:” Settlement, urban space, and emergent interracial sexualities for African newcomer youth in Winnipeg. City & Society 3(2):165–185. doi: 10.1111/ciso.12176.

- Gardezi, F., L. Calzavara, W. Husbands, W. Tharao, E. Lawson, T. Myers, A. Pancham, et al. 2008 Experiences of and responses to HIV among African and Caribbean communities in Toronto, Canada. AIDS Care: Psychological and Socio-Medical Aspects of AIDS/HIV 20(6):718–725. doi: 10.1080/09540120701693966.

- Graffigna, G. and K. Olson 2009 The ineffable disease: Exploring young people’s discourses about HIV/AIDS in Alberta, Canada. Qualitative Health Research 19(6):790–801. doi: 10.1177/1049732309335393.

- Gupta, A. 2001 Governing populations: The integrated child development services program in India. In States of Imagination: Ethnographic Explorations of the Postcolonial State. T. B. Hansen and F. Steppetat, eds. Pp. 65–96. Durham, NC and London: Duke University.

- Healey, G. 2016 Youth perspectives on sexually transmitted infections and sexual health in Northern Canada and implications for public health practice. International Journal of Circumpolar Health 75(1):1–6. doi: 10.3402/ijch.v75.30706.

- Larkin, J. and C. Mitchell 2004 Gendering HIV/AIDS prevention: Situating Canadian youth in a transitional world. Women’s Health and Urban Life: an Interdisciplinary Journal 3(2):34–44.

- Latour, B. 2005 Reassembling the Social: An Introduction to Actor-Network-Theory. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Lorway, R. and S. Khan 2014 Reassembling epidemiology: Mapping, monitoring, and making-up people in the context of HIV prevention in India. Social Science & Medicine 112:51–62. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.04.034.

- Lupton, D. 2013 Risk. London: Routledge.

- Marcus, G. E. 1995 Ethnography in/of the world system: The emergence of multi-sited ethnography. Annual Review of Anthropology 24:95–117. doi:10.1146/annurev.an.24.100195.000523.

- Marcus, G. E. and E. Saka 2006 Assemblage. Theory, Culture & Society 23(2–3):101–109. doi: 10.1177/0263276406062573.

- Nguyen, V.-K. 2005 Antiretroviral globalism, biopolitics, and therapeutic citizenship. In Global Assemblages: Technology, Politics, and Ethics as Anthropological Problems. A. Ong and S. J. Collier, eds. Pp. 124–144. Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing.

- Odger, A. 2015 “At-risk? Really? I think anyone can get it”: Bio-pedagogy, sexual health discourses, and African newcomer youth in Winnipeg, Canada. MA thesis, Department of Anthropology, University of Manitoba.

- Omorodion, F., K. Gbadebo, and P. Ishak 2007 HIV vulnerability and sexual risk among African youth in Windsor, Canada. Culture, Health & Sexuality 9(4):429–437. doi: 10.1080/13691050701256721.

- Parker, R. 2001 Sexuality, culture, and power in HIV/AIDS research. Annual Review of Anthropology 30:163–179.

- Pauls, K. 2017 1 in 5 Canadians infected with HIV doesn’t know it. CBC News, December 1. https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/manitoba/aids-hiv-infection-public-health-1.4426643

- Province of Manitoba 2017 Manitoba immigration facts report 2016. Province of Manitoba.

- Public Health Agency of Canada 2010a HIV/AIDS among youth in Canada. Ottawa, ON: Government of Canada, Public Health Agency of Canada.

- ———. 2010b HIV/AIDS among women in Canada. Ottawa, ON: Government of Canada, Public Health Agency of Canada.

- ———. 2012a HIV/AIDS epi Updates. HIV/AIDS in Canada among people from countries where HIV is endemic. Ottawa, ON: Public Health Agency of Canada.

- ———. 2012b Populations at risk. Ottawa, ON: Public Health Agency of Canada.

- ———. 2015 Risk of HIV and AIDS. Government of Canada: Public Health Agency of Canada.

- Raikhel, E. and W. Garriott 2013 Introduction: Tracing new paths in the anthropology of addiction. In Addiction Trajectories. E. Raikhel and W. Garriott, eds. Pp. 1–35. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

- Sayes, E. 2014 Actor-network theory and methodology: Just what does it mean to say that nonhumans have agency? Social Studies of Science 44(1):134–149. doi: 10.1177/0306312713511867.

- Weheliye, A. G. 2014 Habeas Viscus: Racializing Assemblages, Biopolitics, and Black Feminist Theories of the Human. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.