ABSTRACT

Global health programs are compelled to demonstrate impact on their target populations. We study an example of social franchising – a popular healthcare delivery model in low/middle-income countries – in the Ugandan private maternal health sector. The discrepancies between the program’s official profile and its actual operation reveal the franchise responded to its beneficiaries, but in a way incoherent with typical evidence production on social franchises, which privileges simple narratives blurring the details of program enactment. Building on concepts of not-knowing and the production of success, we consider the implications of an imperative to maintain ambiguity in global health programming and academia.

One morning we visited the director of a private, not-for-profit hospital in western Uganda whose maternity ward was enrolled in a maternal health social franchising program. This program was run by an agency 300 kilometers away in the capital, Kampala, to support its delivery of maternal health services – offering staff training, subsidized materials, medical equipment and quality improvement monitoring. His clinic was one of 142 private health facilities that had signed on to this scheme, which also involved taking on the signature blue and yellow brand name of the franchise – ProFam – intended to boost name recognition amongst clients and thereby draw in maternity service users, increasing profits. We had completed research on the program the year before and traveled back to discuss our results with the clinics that had participated in the study. We asked the director whether the program had brought him more clients. He hesitated, before replying. “What I can say is, when ProFam leaves, it will be felt in the delivery of our services. The brand might not be an influencing factor, but the presence of ProFam is.”

The response that the brand did not actually do what it was intended to do was not that surprising to us. In fact, we believed that while the program was positive for clinics and clients, the social franchise was not, in practice, fully a social franchise – instead it was marketed as one at the global and national level, but enacted as a quality improvement program. In this article, through a case study of the Merck for Ugandan Mothers (MUM) ProFam social franchise, we explore the field of program implementation in lower income countries. We look at the discrepancies and opacity between a program’s higher-level discourse and its implementation (Biehl and Petryna Citation2013), and elaborate on how notions and representations of success are malleable when aligning with the ideal narratives and hegemonic rhetoric which dominate the global health field. We find that there is an implicit imperative for actors to maintain ambiguity around the details, reporting and evaluation of their programming, thereby enabling operations to continue.

What is social franchising?

Social franchising gained popularity in the early 2000s. Usually run by non-governmental organizations (NGOs), the model recognizes the role of the private sector and uses a commercial franchise approach to achieve social goals alongside financial goals (Volery and Hackl Citation2010). According to a popular definition, the core programmatic areas of social franchises are assuring: 1) the availability of services; 2) the quality of services; 3) the awareness and use of services (Montagu Citation2002). Many social franchises (including MUM) are fractional franchises, meaning that the program only supports a part of the business (such as maternal health).

The literature and debate surrounding social franchising demonstrate that it has been presented as a model that follows a standardized, recognizable form. While services, commodities, and implementation practices will differ between franchises, the logic of the model dictates that each franchise operates in a uniform way, to create homogeneous attributes across the brand.

As the model attracted significant interest and funding across health services in lower and lower-middle income countries, agencies and researchers have contributed to a growing body of literature evaluating its efficacy at reaching its goals, such as providing health services at a population level (Tougher et al. Citation2018) and improving equitable access to good quality health services and products (Haemmerli et al. Citation2018), finding mixed results. In 2015, 64 social franchises operated globally, most of them in sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia (Viswanathan et al. Citation2016), meaning that millions of donor dollars have been or are currently being invested in projects with limited evidence of effectiveness (Mumtaz Citation2018). This contributes a strong incentive to demonstrate that such trending projects are working (Cornwall Citation2010), alongside the motivation to fund projects that actually work.

Theoretical underpinnings

In this article, we look at the tension between programmatic models and the activities that are categorized under those model names but are actually enacted differently in practice. Our questions concern, within the global development project, agencies’ navigation of implementation and partnership, and we explore the phenomenon of programs’ alignment with models in theory but not practice.

Bringing external and local organizations together in health interventions can generate contexts of both shared and divergent interests and aims, with different standards for success and responsibilities toward demonstrating “results” from the partnership (Brown Citation2015). The tensions that emerge around gaining legitimacy on the global stage in terms of funding and recognition and at the local level in terms of producing positive impacts for program participants indicate that the mechanisms and pathways toward success are not always the same. As Mosse (Citation2004) writes, “Programme success depends upon the active enrolment of supporters including the beneficiaries. […] [T]he ethnographic question is not whether but how development projects work; not whether a project succeeds, but how success is produced” (Citation2004:646).

We comment on the conceptualization and implementation of health programs, and how an ambiguity imperative is part of how they produce success. With this case study in Uganda, we both describe an ethnographic account of maternal health social franchising, and reflect on the enactment and processes of “development” or “aid” programs in the private health sector. We argue that the aid landscape influenced program implementation, which subsequently diverged from standard definitions of social franchising. The modifications undertaken by the implementing agency served the project participants and improved the value of the program, but the necessary phenomenon of adaptation contributed a broader disservice to the global community and the production of evidence on a movement in global health.

Materials and methods

This study is part of an interdisciplinary research project in Uganda and India evaluating three maternal health social franchise networks, all funded by MSD (Merck, Sharp and Dohme) for Mothers, the charitable arm of Merck Pharmaceuticals. Our research team was contracted by the funder to scientifically evaluate a selection of the international programs they supported, and given space to investigate related questions that emerged from the evaluation. Makerere University and the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine ethical committees granted approval for this study.

Site selection

In Uganda, a parallel economics evaluation randomly selected 15 of the 134 MUM clinics in operation for at least two years. From these 15, we purposively sampled ten for qualitative research. These 10 clinics represented rural and peri-urban areas, doctor-owned clinics, midwife-owned clinics, private-not-for-profit (PNFP), faith-based and non-faith-based clinics, private-for-profit clinics (PFP), and hospitals run by medical and non-medical professionals. Four were equipped to carry out Cesarian-sections, while six clinics offered basic obstetric care and referred their clients for C-sections. All the PNFP clinics in our sample were supported to some degree by a combination of the Ugandan Protestant Medical Bureau (UPMB), foreign charitable agencies, and other foreign and local donors, and priced their services at reduced rates. During fieldwork, we examined how clinics with such varying business plans and institutional structures responded to the standard MUM-ProFam model.

Data collection

All clinics were visited by team members to establish introductions before later beginning more formal fieldwork. Among the ten clinics, we undertook a package of qualitative methods in six, and conducted only interviews in four. The “intensive” package allowed us to probe questions around the logic of the clinic and staff experiences with the social franchise and triangulate our data. Christine Nalwadda (CKN), Juliet Kiguli (JK) and Isabelle Lange (ILL) spent at least a week in each of the six sites completing the following tasks: a) at least 20 hours participant observation of routine patient care at the clinic, in particular the maternity ward, including informal chats with clinic staff, patients and companions; b) semi-structured interviews with five women (at their own homes) who had used its services; c) semi-structured interviews with two community health workers (CHWs, called Maama Ambassadors) affiliated with the site and program; and d) semi-structured interviews with clinic owners, directors, and maternity ward heads.

We conducted interviews only after we had already spent some days observing and chatting to staff and patients, to better be able to pose context-specific questions. We also purposively sampled five other clinic directors for interviews: one who declined to join the franchise, another who had been asked to leave the franchise, and three who chose to leave the franchise. Interviews were private and lasted between 40 minutes and two hours. Additionally, we visited staff and directors of four other active clinics throughout our research.

Over a two-year period we conducted repeat-interviews with six staff members from the implementing NGO in Kampala, the Programme for Accessible Health Communication and Education (PACE), who contributed to various aspects of the program including social marketing, program management, quality of care supervision, and the conceptualization and implementation of the franchise network.

We met with funders and implementers during workshops, research activities, and dissemination events across this project between 2015 and 2018 which allowed for discussion of study themes. Two follow-up activities also inform this study: 1) In October 2016, we presented the results of our interdisciplinary evaluation in Kampala at PACE’s day-long close-of-project event attended by an audience of national-level stakeholders, program clinic directors, and Maama Ambassadors. 2) In June and July 2017, ILL visited 10 focal clinics to share the results of the overall evaluation with clinic directors and maternity staff. This occasion also served to gather feedback on our results, probe on hypotheses specific to this article topic that had emerged from the first round of analysis, and undertake further participant observation. Many of the staff and directors visited formed part of the initial evaluation between 2015 and 2016, allowing us to follow up on whether and how their perspectives had changed after having more experience with the program, and on their reflections after it had ended.

Our position as researchers and evaluators at the intersection of funder, implementer and program targets meant that different stakeholders could perceive us as occupying varying roles. Sharing with us experiences and opinions that may have been intimately entangled with their livelihoods, responsibilities, social/professional networks, and careers meant that a certain negotiation was likely present in each encounter. While our role in the production of evidence surrounding social franchising is another piece in the puzzle of narrative production in global health programming, in this article we focus on the story of how social franchising is enacted to elaborate our theories on the ambiguity imperative.

Setting

Despite progress in reaching the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) and the attention generated by the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), high maternal mortality and morbidity remain challenges in many low-income countries (LICs), with access barriers and poor quality care still problematic (Graham et al. Citation2016). Global maternal and reproductive health financial aid to LICs has risen in the last decades, supporting efforts to tackle these concerns (Pitt et al. Citation2018), however, amounts fluctuate and are inconsistent.

Some donors prefer to partner with individual agencies on vertical projects, to better demonstrate their funding’s impact (Martinez-Alvarez et al. Citation2017). This impact is generally measured through narrow, quantitative definitions of evidence, especially in the age of evidence-based policy making, which in turn feeds into the pressure to produce the “appearance of global health accomplishment” (Erikson Citation2019:509). Underlying this is the ever-growing culture of output-evaluation and metrics to determine priority funding areas and placing stress on program performance (Davis et al. Citation2012).

Recently, global donors have intensified their investment in the private healthcare sector despite surrounding ideological debates, with several studies and commentaries (such as The Lancet Global Health Series, 2016) highlighting the major role private clinics and health professionals play in delivering care.

These circumstances apply to Uganda, where until recently over 50% of the nation’s health budget came from external donors (Taylor and Harper Citation2014). Since 2001, maternal health services such as antenatal care (ANC) and delivery care have been free for women in government facilities. Nevertheless, the private sector plays a significant role in the provision of maternal services in Uganda, with 25% of deliveries conducted in private clinics in 2011 (Benova et al. Citation2018). While the diverse array of private providers is said to take the burden off strained government facilities, quality of care is often subpar (Waiswa et al. Citation2015), and costs can be prohibitive for many women. Recognizing a gap, various donors in Uganda and elsewhere are thinking of ways to work with the often-unregulated private sector to improve services through programs such as voucher schemes and social franchising.

Staff we visited at MUM clinics named several challenges facing private facilities: lower nursing salaries than government jobs and few pension arrangements; high staff turnover; lack of possibilities for career advancement; and skill training deficits. That said, private facilities were frequently perceived to be better equipped, less crowded, have fewer stock-outs, offer personalized care, and be more efficient.

The MUM social franchise

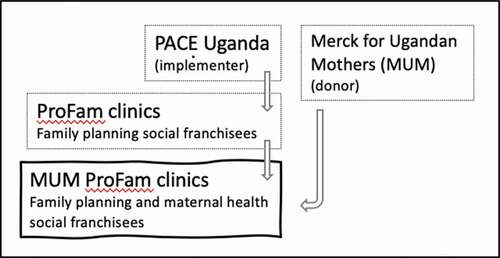

In 2011, MSD for Mothers issued a social franchising funding call to which three organizations were successful – two in India, and one in Uganda (PACE). Through its partnership with MSD for Mothers, PACE expanded its existing ProFam fractional social franchise with MUM (see ). Originally established in 2008 for the provision of family planning services, the ProFam social franchise increased its scope to offer maternal health (antenatal care, delivery services, and postnatal care) as a franchised service. At its peak, it operated in 43 districts and offered services through 142 private health facilities. These facilities varied in type of services offered, size and profit orientation, with the majority PFP and others PNFP – in which case they were generally faith-based.

MUM’s overall goals were to complement the government’s efforts to reduce maternal mortality by increasing utilization of quality maternal health services provided through the private sector and expanding community level outreach. They anticipated that this would, in turn, free up government resources for those most in need and unable to pay for maternal healthcare services, easing the burden on the public sector.

PACE’s proposal sought to achieve these goals by expanding the number of ProFam clinics and extending the scope of their services to maternal healthcare. With the MUM fractional social franchise network, PACE aimed to leverage ProFam’s brand recognition and maternal health training and tools to rapidly expand and improve provider practices. Franchisees received technical and business training, subsidized products and equipment, monitoring, supervision, and on-site coaching from PACE. PACE’s promotion of the brand as offering high quality, affordable services would subsequently increase client flows to the provider. Expanding community-level outreach through a network of CHWs called Maama Ambassadors was an additional strategy. In turn, as part of the partnership, the franchisee committed to meeting PACE service delivery quality standards, and providing certain products at agreed prices.

Our wider analysis based on 15 clinics found that there was no clear demonstration that clinics saw client numbers increase due to their membership in MUM (Haemmerli et al. Citation2018). Why then did franchisees stay on board, and, largely, have positive things to say about their involvement with the program? We argue that this is because members experienced many other positive aspects of the implementation and effects of MUM that did not meet the typical “target indicators” by which social franchises are usually measured. It is this discrepancy that creates benefit for the facilities in the project, but is at the potential detriment to the discourse of the wider academic and global programmatic community which ultimately skews the dialogue on social franchising.

In the following sections, we first describe the local aid landscape into which the social franchise was introduced and how that shaped implementation. Following this, we explain the implementation of the model focusing on five of its key features: branding; membership fees; improvement of quality of care; community health workers’ roles; and pricing of client services.

The influence of the local landscape on program implementation

Donor-dominated landscape

MUM-ProFam operated in a landscape of free governmental maternal healthcare and several social franchise member facilities received donor aid from other agencies in support of their reproductive and maternal services. When PACE proposed layering the MUM franchise onto their existing ProFam family planning network, they anticipated being able to recruit from a larger selection of clinics. However, many of those meeting their criteria were already involved in other agencies’ exclusive schemes and were therefore unavailable. This reduced selection resulted in PACE expanding their search to include nonprofit clinics in some areas, meaning that different business models needed to be accommodated by their platform.

PACE staff commented on the challenges of working in a private sector populated by a plenitude of initiatives. One donor agency in particular was singled out as a competitor, “breaking the market” with their methods to achieve their target numbers by, for example, offering free products, making it difficult for other schemes to be successful. Some of PACE’s target clinics did not join ProFam because they perceived these other programs to be more advantageous.

Not only did the donor-dominated landscape impact site selection, but the historical presence and prevalence of other projects – sometimes with a high-turnover rate – influenced PACE’s arrangements with members of the community involved with MUM. We found that Maama Ambassadors compared the amenities and payments they received from PACE to those from other donor projects with larger budget lines for their outreach activities, and consequently expected more from MUM. At the mention of this topic, PACE staff exclaimed, “Yes! Please, speak about this – it affects everything we do!” Many of their stakeholders were accustomed to a unilateral relationship in which knowledge, funds, and goods flowed from the (donor) agency to the clinic and community, meaning that negotiating terms and communicating the reciprocal and “social good” aspects of the social franchising partnership were occasionally complicated. They had been courted by foreign projects for years and had high expectations of receiving money and commodities from them.

Keeping the coals hot on many burners

Some clinic directors told us that despite the presence of many donors in the healthcare sector in Uganda, most left out the private sector. The head midwife at a private hospital told us how valuable MUM and PACE were to her: “Most of the donors help the community, but they don’t help us do our work with the community.”

Both larger and smaller PFP and PNFP clinics sought alliances with multiple actors (NGOs and international agencies) as a means of supporting their work. These collaborations were sometimes consecutive and at times simultaneous but not overlapping in program areas to MUM. Not all clinics were successful at gathering multiple strands of support, and funding lines could dry up unexpectedly.

In northern Uganda, we visited a MUM-ProFam clinic whose largest supporter was a Christian congregation in the United States. This was an expanding PFP facility headed up by a dynamic gynecologist whose dual expertise in fundraising and project management was apparent alongside his clinical skills. He said the most challenging aspect was finding partners who could respond to the needs of his clinic, community, and the context he was working in after the war. “How can you support me; respond to my needs? Not just come in and tell me what you need us to do.”

Three hundred kilometers away, the director of a PNFP hospital serving a poor, rural community at subsidized rates listed the programs he had been involved with the last six years. Project V: “Gone.” Program W: “Vanished. Funders tend to leave when a project stops.” Charity X: “Comes through in a crisis and bails us out, but we pay them back.” Program Y: “We receive the cryotherapy machine, but it is up to us to get the gas to run and assure its maintenance.” Project Z: “I anticipate it coming back in a couple years after the restructuring of their funding schemes, but am also anticipating challenges in the partnership and handover for things to run smoothly. New partners, new challenges …”

During our visit, this director learned the Ministry of Health slashed his budget by 50% for the coming year. We sat in his office and discussed the ramifications for his facility. How was he going to make it work? This remote clinic supported partly by government funds (unlike the majority of MUM facilities) offered care to an isolated community at subsidized rates and would struggle performing its services. In this moment, the relationship with PACE seemed at once trivial in the face of such critical operational funding challenges, and yet essential and significant for its help and solidarity in even a small way.

Not only PNFP, but also PFP clinic owners felt the need to diversify their partnerships with agencies due to the turnover of programs and maintain independence regarding branding and buying in completely to one sponsor. Regarding his simultaneous involvement with MUM and other programs, one PFP doctor said: “… I think that it’s ok, because tomorrow ProFam will say, ‘Sorry, we are closing shop.’ And we will have to continue. [Our clinic] will have to continue.”

They need us

The multiplicity of programs was not lost on some of the PFP clinic owners who saw these agencies as vying for a share of the healthcare delivery market and identified a certain power in their own role in the system. Two directors highlighted the reciprocal relationship they believed they had with PACE through the MUM-ProFam network. Without participating clinics, they claimed, PACE would not be able to exercise their mandate. “ProFam needs me – they don’t have an office, and without an office they can’t reach the population!” one owner explained. For PACE to achieve their aims, obtain funding, and make their mark on the programmatic map, a partnership with these clinics was indispensable. In this sense, clinics turned the tables and subverted the traditional articulation of the donor-recipient relationship. Furthermore, this perspective could be regarded as fundamentally undermining the social franchising concept as the perceived mutual need makes it harder for PACE to assert its membership requirements, such as maintaining quality of care standards. PACE staff acknowledged they “gave away” plenty of materials and resources to clinics in order to bring them on board and settle them in to the network. They were practically “begging the clinics to join.”

After having set the scene of the implementing landscape above, in the next section we turn to describe five flagship characteristics of the social franchise and how they were enacted.

The implementation of the MUM social franchise

Belonging to the brand and the network

MUM as a separate brand itself did not exist at the facility level, instead it was subsumed to the original ProFam brand which was more established. This blurred the lines in our evaluation, as the distinction between the original family planning franchise and the addition of the maternal health component to a selection of the ProFam clinics sometimes created an invisible unit of study. Not all staff viewed them as separate entities, which indeed they were not, even if they had different donors, foci and lifespans. We saw some evidence of ProFam at all facilities but the extent varied – from the whole building exterior painted brightly in the brand’s signature blue and yellow colors, to simple skill-refresher posters for health staff hung in the labor room.

Clinic managers did not emphasize the ProFam brand as drawing maternal health clients to the facility. Instead, they referred to the responsibility of the MUM Maama Ambassadors to carry out education, outreach and sensitization workshops to encourage women to attend. Beyond this, all clinics reported relying on their own brand rather than ProFam’s. They had been in business before joining the ProFam network and, they noted, it was important to ensure that their reputations were independently strong. A staff member at a popular PNFP clinic touched on the point of visual branding:

I personally think if their [women’s] decisions to come here is at a rate of 80 percent, maybe it would go to 90 percent. Meaning, whether we brand or not, they would still come. But when you brand, there are a few who respond to that, but also it is just healthy that if I am partnering with you, why not identify you? So, it is ok. (Clinic director (CD)/PNFP2)

This clinic had very little visible ProFam branding on the outside – only a faded plaque – but plenty of ProFam posters hung in the maternity ward. Staff at other member clinics believed that ProFam had an impact on their business and that they acquired more family planning clients, but not necessarily more maternal health clients. “I don’t know whether our mothers come because of ProFam, just looking at it …,” said one owner of a hospital – a reflection that was echoed by others of a similar size. His clinic was a free facility, however, and did not charge for services – in itself a draw to local women. When we interviewed women about why they chose to deliver at MUM facilities they mentioned the positive characteristics of the clinic, the reputation of individual health workers or the reputation of the clinic, but did not mention the ProFam brand, which they associated with family planning (if anything), but not maternal health services.

What is a social franchise if it cannot create a recognizable brand? Widely identifiable branding could be particularly challenging with a fractional franchise, as the external program does not support the entire clinic. Could branding be less significant for maternal services, in that women seek these out for different reasons than they do other healthcare, with word of mouth and personal recommendations playing a larger role? The short duration of MUM could also influence our results on brand recognition in the community; the program had been operating three to five years at the time of our fieldwork, and brands and reputations could need more time to become established.

Nevertheless, we found that clinic directors preferred not to subsume their brand to that of the franchise and found it important to retain their own identity. PACE made no requirements for clinics to weaken their own brand with membership to the franchise; instead, it was seen as an additional tool for them to market their services.

Membership fees

A reciprocal component of the MUM protocol involved charging membership fees of all participating clinics. In return for paying these fees and complying with the memorandum of understanding signed by both parties, clinics would have access to the program perks described earlier, such as access to subsidized medicines, branding, training, and supervision visits. A two-year membership with MUM officially cost 50,000 UGX (about 16 USD at the time of fieldwork).

Many clinics reported not being asked to pay joining or membership fees, and others quoted payments that were under the official rates. Some owners told us that they did not realize that payment was even a component to the program. PACE field staff articulated a reluctance to ask for the dues, and demonstrated the perceived clash between conducting “business” and “social good.” Ultimately, only one percent of PACE’s investment costs were recovered from fees and other services, making the program largely unsustainable without external donor support (a point that was arguably acknowledged at the start of the program).

By not charging these fees, the reciprocal tenet of the franchise is lost, and a core act of collaboration and mutual investment between franchisor and franchisee is omitted from the program. Instead of being considered something of a partnership, where both parties invest (as in a typical business relationship in the private sector), the one-sided donor aspect of the relationship is reinforced – one where funds flow in only one direction in exchange for the opening of spaces to receive goods, training, and monitoring. This flexible approach to charging membership fees was a symptom of how the tenets of social franchising in this program were relaxed in order to accommodate the clinics and to “get it off the ground.”

Improvement of quality of care

Quality improvement programs have long faced challenges in health settings to improve medical outcomes and indicators, with one shortcoming being that they frequently fail to take wider system circumstances into consideration and focus on change at the individual clinic level. As the aim of the social franchise was to “improve access to good quality of care” (PS1), a core element of the program included the strengthening of skills, medication availability, and infrastructure to boost the quality of care.

PACE developed an impressive system for monitoring quality of care in its member facilities, incorporating World Health Organization standards and Ugandan Department of Health guidelines. However, we did visit some clinics that were allowed to remain in the franchise without meeting PACE quality standards, which was justified in that clients would at least receive some improved care if MUM maintained the relationship.

Clinic directors considered PACE’s quality of care skill training to be a major benefit of joining MUM. This gave them access to educational opportunities they in the private sector may not have otherwise had access to.

You know, they say that knowledge is power. I have always liked the training part because when you give somebody knowledge you are empowering them and since the world is developing, we need to go … (CD/PFP5)

Shortcomings flagged by both clinics and program staff are well-known for the private healthcare sector in the region, such as the detriment high staff turnover can have on retaining lessons from skills training. Nevertheless, the overall message we heard was that the quality of care component was one of the main motivations for joining the MUM project, in part because as small facilities in the private sector they needed to be able to get all the support they could get.

Community outreach through Maama Ambassadors

Maama Ambassadors, hired and paid each quarter by PACE to promote MUM services at ProFam clinics, told us they were happy to be involved with the MUM project, and saw it as an opportunity to strengthen and widen their relationships to their communities. A sense of social responsibility to improve maternal health in their circles motivated many to join. Some already functioned as CHWs, trained by the government to work as liaisons between patients and health facilities, and as agents who could communicate government programs to the community. This meant that with the addition of MUM they straddled dual roles between promoting government and private sector resources.

Maama Ambassadors emphasized that there were limitations to their influence over women’s care seeking decisions. What they could offer was to act as a resource for them, which was in line with how PACE envisioned their roles.

However much you convince her to go a place of your choice, she will say no. Therefore, since I am connected to both places, I always let her go to her place of choice where she feels comfortable. But we get more clients in the private than in the government facility because mothers say that they are mistreated in government facilities—from family planning to deliveries. (MA/PFP6)

Other Mamma Ambassadors mentioned that they felt conflicted about being trusted and established in their roles as CHWs, while also advising their neighbors to seek private maternal services that could be costly. PACE did not ask them to misguide anyone who could not afford treatment, but the strategy of hiring already existing government-trained CHWs to work for a private initiative, even if they were useful because of the knowledge and position they already had, was complicated. Our observations indicated that Maama Ambassadors’ messages may have been diluted through their involvement in many programs with different aims.

Pricing of services

One of the “social good” aims of social franchising is to place private sector care within easier reach of a range of clients from different socio-economic status (SES) by offering services at a more affordable cost. For MUM, the strategy entailed reducing fees compared to similar providers with the franchisor’s support in technical tactics and materials, and boosting clientele numbers through franchise membership. While the goals surrounding this aspect changed for the implementer and the donor as the project evolved, our evaluation found that the services of this and the other two maternal health social franchises we studied in India were mostly accessed by women of higher socio-economic status (Haemmerli et al. Citation2018).

Many franchisees were encouraged to keep their prices lower than other competitors, but PACE advised at least one PNFP clinic in our sample to raise its fees for vaginal childbirth, which they did. Although directors (across both PNFP and PFP) indicated that they benefited from the MUM subsidies, some found it difficult to reconcile their business models with the social franchise guidelines regarding patient fees, even deciding to leave the network.

The PNFP facilities sampled chose to accommodate these conditions and still charge little or nothing, but they also received support from other agencies. For anyone hoping to make direct profits off of MUM, we were told that it was an “expensive model for a poor community” – even with the subsidies going toward the reduction of fees. A director who quickly left the network suggested that the “community let them [PACE] down,” because patients could not pay the fees that were associated with their services.

We observed free and subsidized supplies (such as filing cabinets and office materials) that came from other budget lines being given to MUM members. In effect, MUM social franchising was also subsidized by other sources, and was able to support its member clinics through items at reduced cost or credit lines, prompting questions about the sustainability of the program without donor support.

Discussion

Our results show that the MUM social franchise was well-received by both doctor and midwife-run clinics as well as the maternity units of smaller hospitals, and that as a result of the efforts of both program and clinic staff, it integrated well into supporting and enhancing existing services. Clinics made few compromises and minimal investments into the social franchise as members, both in terms of financial and or practical commitments.

Especially appreciated was the support that the franchise offered in terms of business advice, quality of care improvements, skill development, and material support, which PACE tailored to the clinics’ needs where possible. In this sense, MUM mirrored other donor projects operating in the area, and did not operate decisively and recognizably as a social franchise. Ambiguity surrounded the actual implementation of the model. Competition among externally funded projects due to the donor landscape highlighted how the multiplicity of competing programs duplicated efforts in the area and limited PACE’s means to exercise the social franchise model.

Our results synchronize with those of others who have studied social franchising. For example, Sieverding et al. (Citation2015) found that creating meaningful change through branding was challenging. The suitability of social franchising for the delivery of maternal health services has been questioned, and there is evidence that its application in healthcare may find greater success when it deals in commodities. MUM was layered onto the existing ProFam family planning franchise, which might have provided an appropriate vehicle for the positive introduction of a maternal social franchise. Could MUM have stood on its own? Was the support it received from an array of broader programs a smart, forward-thinking arrangement by PACE that pooled resources, reduced duplication, and benefited the community?

PACE deviated from their original protocol as they rolled out the social franchise. Contrary to evaluation standards, we do not view these diversions from the social franchising protocol as an example of a failed initiative. Instead, we see adaptations made by PACE to have benefited their member community and fostered positive relationships. We argue that the actual implementation of the MUM franchise was responsive to the situation on the ground, but not in a way that is coherent with evidence production on social franchises, which privileges clear narratives blurring out the details of how franchises are actually enacted.

Production of “success”

This situation, we contend, is not unique to MUM, nor to social franchising in general, but indicative of the discourses straddling the local and global contexts of aid programs. Parker and Allen draw attention to the “hegemonic rhetoric” (Citation2014:236) that accompanies global health campaigns and masks actual activities, potentially labeling and framing projects undertaken in selectively advantageous ways. The language PACE uses with its clients was understandably different from that of its public relations activities aimed at global health audiences. As David Mosse writes: “Policy discourse generates mobilizing metaphors (‘participation’, ‘partnership’, ‘governance’, ‘social capital’) whose vagueness, ambiguity and lack of conceptual precision is required to conceal ideological differences, to allow compromise and the enrollment of different interests, to build coalitions, to distribute agency and to multiply criteria of success within project systems” (Mosse Citation2004:663).

We have seen this sort of ambiguity with popular buzz words in the social franchising world such as “social good” and “partnership” (Cornwall Citation2010), in that they are anchored in conceptualization, but operationalized in obscurity, without a consensus among actors on their significance and meaning. These gaps in definition and interpretation are favorable to those in charge such as donors and successful agencies, as they ride the funding rollercoaster to their advantage. A senior midwife at a northern Ugandan midwifery school lamented at a London maternal health workshop about the abundance of fruitless attention and action in her domain: “The policies are spinning very fast for us, but the reality remains the same, the end result is the same. Spinning and spinning, but we [at the hospital] see no benefit” (Sister Carmel Abwot, fieldnotes 14.6.2018).

MSD for Mothers’ funding call for maternal health social franchising suited PACE’s activities. Already running a social franchise for family planning, they subsequently developed their proposal to obtain funding – aligning their aims with the funders, the MDGs, the reduction of maternal mortality, providing a “social good,” and finding a way to work with the private sector. In Uganda, as in large swaths of the global scene, there is pressure to create interventions that are easily analyzable and actionable (Okwaro et al. Citation2015), and the social franchising model offered a practical, delineated vehicle through which to act.

Knowing about not knowing: or, ambiguity and silence in reporting what is known

We consider the lack of reporting on the discrepancy between program appearances and practice to be an “ambiguity imperative” among global health actors that facilitates collaborations and partnerships. Ultimately, for each of the core social franchising aims (social good, quality of care, equity, and support for both maternal health indicators and clinics) the program diverged from the model described in the protocol and the typical social franchising tenets. However, in dissemination of the project results to the global community, the program continues to be labeled as a social franchise.

Scholars have made useful contributions to conceptualizing the differences between practice and discourse. Geissler sets out the pervasiveness of an attitude of “knowing not to know” in scientific and programmatic work. Building on Murray Last’s pioneering text “The Importance of Knowing about not Knowing” (Citation1981). Geissler (Citation2013) describes not the opposite of knowing, but “unknowing,” the practice of interpreting what is known into a form that gels with the dominant, authorized scenario, and exercising refined recognition of which knowledge does not apply and “should not be known” nor disseminated. Through her case study of governmentality and aid in the health sector in Tanzania, Noelle Sullivan writes about how actors’ lack of transparency can serve them: “Without the possibility of skirting realities through practices of unknowing, development cooperation as a framework would break down” (Sullivan Citation2017:202). She argues that poor and difficult data collection and dissimilar reporting measures emblematic of programmatic and evaluation activities can work in favor of aid communities in that it heightens the challenge of showing what actually works and allows for narratives to gain clout without being verifiable. As Watkins and colleagues assert, evaluations of development projects are generally “designed not to evaluate but to create success” (Citation2012:303).

This presents a useful framework in global health research, in that knowing what not to know facilitates project implementation, and that communication between different levels of participants is defined by layers of inclusion and exclusion of information. In the example of this social franchise, the implementers know, and the donor knows – but the presentation of details to affiliated communities is curated. For example, during conference calls preparing our dissemination of results on equity in social franchising, it was the implementing agency’s parent organization – which deals with handling its programs’ global level image – that stepped in to negotiate the tone and content, cognizant of how these messages would feed into wider discourses of project success and funding prioritization. Kingori and Gerrets unpack a more extreme phenomenon through their research on deliberate “fakes” in what they call pseudo global health, the “indeterminate, blurry and messy spectrum that exists between binary oppositions” that can “can obscure and misrepresent ‘in-between phenomena’” (Citation2019:280). They highlight how power infuses every step of global health encounters, and caution recognizing only the power of northern actors or those who traditionally have held economic and social capital. For us that would mean creating an incomplete picture side-lining the agency of the less globally-visible actors who ultimately shape the texture and outcomes of relationships and collaborations.

Success with social franchising

In responding to Mosse’s interrogation at the beginning of this piece asking to understand “how” success is produced, we learn that it is also important to understand how success is measured. Is it through the success of the model or the success of the implementation of a program that may have been different from the model?

PACE’s adaptations to what their members preferred were ultimately positive for the clinics, and, in a sense, produced its “success.” While not compromising on quality of care or service standards, they were able to extend their program to clinics which benefited from support they otherwise would not have received. While most of the facilities in the program were smaller for-profit midwife-run clinics, the flexibility of PACE’s implementation strategy allowed them to include not-for-profit facilities and strengthen their services as well.

Scholars, program developers, and policy makers have been debating whether social franchising works. By 2018, at a symposium on the private sector in maternal health at which our evaluation results on three social franchises were presented, the dialogue had already shifted to a dismissal of the narrative of social franchising. “We all know social franchising is rarely what they say it will be,” a discussant proclaimed at our panel (fieldnotes 21.5.2018). Recently, a series of commentaries in The Lancet Global Health engaged with the interpretation of evidence on social franchising. In one piece, a practitioner argues that the evaluation of narrowly defined social franchises misses those that do find success employing other methods and business models (McBride Citation2018). While it may very well be that social franchising in its various forms works in certain settings for certain health services, ultimately these nuances in their conceptualization and implementation are important when defining what does and does not work.

Implications for programmatic work and the global community

The ambiguity imperative and the tension between achieving meaningful results for participants and producing models that can be evaluated and potentially replicated at the global discourse level can result in a devaluation of knowledge surrounding what actually works outside of the scope of the model. More seriously, this means that through omission, misinformation can lead to policy recommendations that are ineffective, and the maldirection of funds that could be put to better use.

Initiatives that set parameters and call for the articulation and definition of approaches and programs are useful, and can be learned from. The “social franchise” model limited MUM’s structure, but did it also foment the program, give it shape, focus, and foster creativity to find solutions for these clinics?

Insights from this project may have something to offer the epistemological communities of those conceiving and implementing global development projects. Critically, it suggests that “success” be measured not solely in the replication of models or in the production of positive evidence that furthers buzz and energy around popular concepts. Instead, the process should be privileged alongside the product, to allow this discourse to be given space and to reveal the contradictions and messiness inherent in the production of quality programs in complex situations. Also, shared aims should be established from the outset. There are no “givens” in the interpretation of policies and programs.

The director of MSD for Mothers was credited with creating an environment where mistakes could be made, discussed, and learned from instead of covered up or ignored. An appreciated mantra of the donors was to “fail fast, fail quickly,” so that the implementers could move on swiftly, tweak, and subsequently get things “right.” While this made it more challenging to evaluate programs that underwent course corrections, implementation could be fine-tuned and required resources made available. Context holds considerable sway over uniform initiatives, and PACE’s keen knowledge and understanding of the terrain, care-seeking practices, and health issues affecting the area meant that they were in an ideal position to make nuanced and informed decisions on what worked – even when it did not fall under the definition of social franchising.

Instead of privileging research outputs which are often delayed in academic or peer review cycles, programmatic lessons can find complementary venues for diffusion, such as through communities of practice. Donors have a responsibility to not “push for success” but foster a learning environment where all results are valuable (and how they were achieved), not only those with positive results and/or demonstrating change and impact.

Conclusion

Through our analysis of this social franchise, we have seen that the implementation of health projects is greatly influenced by the landscape – comprising not just the participants, but also the circumstances created by the development community. This effects competition among donor projects, with the funding landscape limiting the implementer’s means to exercise the model by-the-book, and resulting in skewed communication of what social franchising is in practice to global level actors; a tacit agreement of the ambiguity imperative. This context also encourages the production of successful narratives for agencies to remain competitive and access funding, at the cost of evidence and transparency surrounding the messiness of global programs. In our case study, the modifications to this program were positive where it counts most: the beneficiaries, even if not for the global discourse. As long as healthcare in lower income countries remains polarized between private services for the wealthy, limited interventions for the poor run by NGOs and humanitarian agencies, and neglected public health systems (Prince Citation2017), perhaps we can consider this privilege of modification to be more correct than trying to align with global models simply for the sake of it. The key is to bring them together meaningfully and openly.

Acknowledgments

We thank the owners, staff and patients at MUM clinics and PACE staff for sharing time, space and thoughts with us during our research.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Isabelle L. Lange

Isabelle L. Lange is an anthropologist working on maternal health, hospital environments, quality of care and global health policy adaptation at LSHTM. Her further research interests surround questions of identity and health seeking, and the logics of humanitarian aid organizations.

Christine Kayemba Nalwadda

Christine Kayemba Nalwadda graduated with a PhD in Public Health from Makerere University and Karolinska Institutet. She is Senior Lecturer and Head of the Department of Community Health and Behavioural Sciences at Makerere University. Her research areas include maternal and newborn health, health policy, and community health.

Juliet Kiguli

Juliet Kiguli is a Senior Lecturer in the Department of Community Health and Behavioural Sciences, Makerere University. She is an ethnographic scientist and gender analyst holding a PhD in Anthropology from the University of Cologne, Germany (2001). Her work explores major debates in development studies, globalization, gender, power and cultural modernity, food policy, social theory, contemporary anthropology and health.

Loveday Penn-Kekana

Loveday Penn-Kekana is Assistant Professor at LSHTM with 20 years experience working as an activist, program manager, and technical advisor in the Department of Health in South Africa, and as an academic in the field of maternal health and health systems with a particular interest in the health workforce. Her focus has been on gender-based violence, reproductive and maternal health services, and nursing and midwifery practice.

References

- Benova, L., M. L. Dennis, I. L. Lange, O. M. Campbell, P. Waiswa, M. Haemmerli, Y. Fernandez, K. Kerber, J. E. Lawn, A. C. Santos, and C. A. Lynch 2018 Two decades of antenatal and delivery care in Uganda: A cross-sectional study using demographic and health surveys. BMC Health Services Research 18(1):1–15. doi:10.1186/s12913-018-3546-3.

- Biehl, J., and A. Petryna 2013 When People Come First. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Brown, H. 2015 Global health partnerships, governance, and sovereign responsibility in western Kenya. American Ethnologist 42(2):340–55. doi:10.1111/amet.12134.

- Cornwall, A. 2010 Introductory overview–buzzwords and fuzzwords: Deconstructing development discourse. Deconstructing Development Discourse 1:1–18.

- Davis, K., A. Fisher, B. Kingsbury, and S. E. Merry 2012 Governance by Indicators: Global Power through Classification and Rankings. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Erikson, S. 2019 Faking global health. Critical Public Health 29(4):508–16. doi:10.1080/09581596.2019.1601159.

- Geissler, P. W. 2013 Public secrets in public health: Knowing not to know while making scientific knowledge. American Ethnologist 40(1):13–34. doi:10.1111/amet.12002.

- Graham, W, S Woodd, P Byass, V Filippi, G Gon, S Virgo, D. Chou, S. Hounton, R. Lozano, R. Pattinson, and S. Singh 2016 Diversity and divergence: The dynamic burden of poor maternal health. The Lancet 388(10056):2164–75. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31533-1.

- Haemmerli, M., A. Santos, L. Penn-Kekana, I. Lange, F. Matovu, L. Benova, K. L. Wong, and C. Goodman 2018 How equitable is social franchising? Case studies of three maternal healthcare franchises in Uganda and India. Health Policy and Planning 33(3):411–19. doi:10.1093/heapol/czx192.

- Kingori, P., and R. Gerrets 2019 Why the pseudo matters to global health. Critical Public Health 29(4):494–507. doi:10.1080/09581596.2019.1609650.

- Last, M. 1981 The importance of knowing about not knowing. Social Science & Medicine Part B: Medical Anthropology 15(3):387–92.

- Martinez-Alvarez, M., A. Acharya, L. Arregoces, L. Brearley, C. Pitt, C. Grollman, and J. Borghi 2017 Trends in the alignment and harmonization of reproductive, maternal, newborn, and child health funding, 2008–13. Health Affairs 36(11):1876–86. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.2017.0364.

- McBride, J. 2018 Setting the record straight on social franchising. The Lancet Global Health 6(6):e611. doi:10.1016/S2214-109X(18)30194-3.

- Montagu, D. 2002 Franchising of health services in low-income countries. Health Policy and Planning 17(2):121–30. doi:10.1093/heapol/17.2.121.

- Mosse, D. 2004 Is good policy unimplementable? Reflections on the ethnography of aid policy and practice. Development and Change 35(4):639–71. doi:10.1111/j.0012-155X.2004.00374.x.

- Mumtaz, Z. 2018 Social franchising: Whatever happened to old-fashioned notions of evidence-based practice? The Lancet Global Health 6(2):e130–e131. doi:10.1016/S2214-109X(17)30501-6.

- Okwaro, F. M., C. I. Chandler, E. Hutchinson, C. Nabirye, L. Taaka, M. Kayendeke, and S. Nayiga 2015 Challenging logics of complex intervention trials: Community perspectives of a health care improvement intervention in rural Uganda. Social Science & Medicine 131:10–17. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2015.02.032.

- Parker, M., and T. Allen 2014 De-politicizing parasites: Reflections on attempts to control the control of neglected tropical diseases. Medical Anthropology 33(3):223–39. doi:10.1080/01459740.2013.831414.

- Pitt, C., C. Grollman, M. Martinez-Alvarez, L. Arregoces, and J. Borghi 2018 Tracking aid for global health goals: A systematic comparison of four approaches applied to reproductive, maternal, newborn, and child health. The Lancet Global Health 6(8):e859–e874. doi:10.1016/S2214-109X(18)30276-6.

- Prince, R. J. 2017 Universal health coverage in the global south: New models of healthcare and their implications for citizenship, solidarity and the public good. Michael 14(2):153–72.

- Sieverding, M., C. Briegleb, and D. Montagu 2015 User experiences with clinical social franchising: Qualitative insights from providers and clients in Ghana and Kenya. BMC Health Services Research 15(1):49. doi:10.1186/s12913-015-0709-3.

- Sullivan, N. 2017 Multiple accountabilities: Development cooperation, transparency, and the politics of unknowing in Tanzania’s health sector. Critical Public Health 27(2):193–204. doi:10.1080/09581596.2016.1264572.

- Taylor, E. M., and I. Harper 2014 The politics and anti-politics of the global fund experiment: Understanding partnership and bureaucratic expansion in Uganda. Medical Anthropology 33(3):206–22. doi:10.1080/01459740.2013.796941.

- Tougher, S., V. Dutt, S. Pereira, K. Haldar, V. Shukla, K. Singh, P. Kumar, C. Goodman, and T. Powell-Jackson 2018 Effect of a multifaceted social franchising model on quality and coverage of maternal, newborn, and reproductive health-care services in Uttar Pradesh, India: A quasi-experimental study. The Lancet Global Health 6(2):e211–e221. doi:10.1016/S2214-109X(17)30454-0.

- Viswanathan, R., E. Schatzkin, and A. Sprockett 2016 Clinical Social Franchising Compendium: An Annual Survey of Programs: Findings from 2015. San Francisco: University of California, San Francisco. Global Health Sciences, The Global Health Group.

- Volery, T., and V. Hackl 2010 The Promise of Social Franchising as a Model to Achieve Social Goals. The Handbook of research in social entrepreneurship, edited by A. Fayolle, 155–179. Edward Elgar Publishing Limited.

- Waiswa, P., J. Akuze, S. Peterson, K. Kerber, M. Tetui, B. C. Forsberg, and C. Hanson 2015 Differences in essential newborn care at birth between private and public health facilities in eastern Uganda. Global Health Action 8(1):24251. doi:10.3402/gha.v8.24251.

- Watkins, S. C., A. Swidler, and T. Hannan 2012 Outsourcing social transformation: Development NGOs as organizations. Annual Review of Sociology 38:285–315. doi:10.1146/annurev-soc-071811-145516.