ABSTRACT

In some Ugandan fishing communities, almost half the population lives with HIV. Researchers designate these communities “HIV hotspots” and attribute disproportionate disease burdens to “sex-for-fish” relationships endemic to the lakeshores. In this article, we trace the emergence of Uganda’s HIV hotspots to structural adjustment. We show how global economic policies negotiated in the 1990s precipitated the collapse of Uganda’s coffee sector, causing mass economic dislocation among women workers, who migrated to the lake. There, they entered overt forms of sex work or marriages they may have otherwise avoided, intimate economic arrangements that helped to “engineer the spread of HIV,” as one respondent recounted.

Southern and East Africans make up 54% (20.7 million) of the world’s population living with HIV, a figure that remains disproportionately high despite billions of dollars invested in national prevention and treatment programs (UNAIDS Citation2020). To better target interventions, donors such as UNAIDS, WHO, PEPFAR, and The Global Fund have increasingly embraced efforts to map “HIV hotspots” within and across national borders, focusing on specific geographic locations with the highest HIV burdens. The hotspots paradigm has drawn researchers to the fishing communities surrounding Lake Victoria, Africa’s largest lake, bordered by the Masaka and Rakai districts of southcentral Uganda. Africa’s first cases of HIV, referred to locally as sirimu or “slim disease,” were documented in Rakai in the early 1980s, and by the early 2000s the area had become one of the world’s regions most devastated by AIDS (Serwadda et al. Citation1985). Decades later, prevalence rates remain disproportionately high: nearly fifty percent of the population in some of Rakai’s fishing communities live with HIV, compared to between ten and twenty percent in nearby agrarian communities and trading hubs (Chang et al. Citation2016; Kamali et al. Citation2016). In 2013, Uganda’s Ministry of Health classified Lake Victoria’s fishing communities as priority populations for targeted HIV prevention services, and the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation has since sponsored “hotspot” research in the area (Ratmann et al. Citation2020).

Subsequently, the question of why Lake Victoria’s fishing communities exhibit such disproportionately high disease burdens has generated numerous studies of the social behaviors shaping HIV vulnerability found among fisherfolk, including high rates of migration, alcohol use, and especially transactional sex. In fact, an entire literature has emerged that documents so-called “sex-for-fish” arrangements wherein women provide domestic service, care, and sex to acquire resources – fish – from fishermen (Mojola Citation2011, Citation2014; see also Béné and Merten Citation2008; Bradford and Katikiro Citation2019; Burke et al. Citation2017; Camlin et al. Citation2013; Deane and Wamoyi Citation2015; Fiorella et al. Citation2015; Kwena et al. Citation2012; Lubega et al. Citation2015; MacPherson et al. Citation2012 ; Merten and Haller Citation2007; Michalopoulos et al. Citation2017; Nathenson et al. Citation2017; Nunan Citation2010; Sileo et al. Citation2019). These studies have provided important evidence documenting how the gendered fishing economies specific to the lakeshores shape intimate relationships and therefore HIV vulnerabilities.

In this article, we expand on these studies of the social lives of fisherfolk while challenging the notion that “HIV hotspots” are the product of geography rather than history. Epidemic “hotspot” research risks naturalizing social behaviors as specific to particular places by disconnecting them from the broader political economies that have and continue to produce them. By contrast, we trace the emergence of the gendered and sexual economies found within Uganda’s fishing communities, and moreover the emergence of lakeshore communities themselves, to global economic policies instituted by the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund in the 1980 s and 90 s, referred to as structural adjustment programs (SAPs). Influenced by the neoliberal ideologies of the Thatcher and Reagan administrations, SAPs reduced state spending, deregulated trade, and privatized the public sector – with drastic consequences for national economies throughout the global south.

In the decades since their implementation, anthropologists have argued that by worsening poverty as well as diminishing state-funded health care, SAPs adversely affected the “social determinants of health,” defined by the World Health Organization as the “conditions in which people are born, grow, work, live, and age, and the wider set of forces and systems shaping the conditions of daily life” (World Health Organization Citation2021; see Forster et al. Citation2019; Kentikelenis Citation2017; Norris and Worby Citation2012; Pfeiffer and Chapman Citation2010; Whyte Citation1991). Many studies of the negative health effects of SAPs were inspired by Paul Farmer, who exhorted health researchers and anthropologists alike to relocate observations of individual behavior and small-scale social worlds to the “structural violence” endured under colonialism and reproduced by global capitalist expansion (Farmer Citation1992, Citation2004, Citation2005). Yet underspecified references to structural violence can render these structures “faceless,” which prevents holding their policies, institutions, and actors accountable (Dubal Citation2012). Put another way, critical medical anthropologists “still need to disentangle the causes, meanings, experiences, and consequences of structural violence and show how it operates in real lives” (Bourgois and Scheper-Hughes Citation2004: 318).

Building from this approach, we seek to unveil the “faces” of structural violence by tracing the historical effects of sector-specific policies enacted under structural adjustment on the everyday lives and livelihoods of southcentral Ugandans. We will show how credits configured by the IMF, the World Bank, and the US Treasury – specifically the Agricultural Sector Credit Program and the Uganda Railways Project – exacerbated Uganda’s HIV crisis by accelerating the collapse of the coffee sector, Uganda’s largest industry and a key source of waged labor for poor women. As coffee factories shuttered in the mid-1990 s, male employees moved into truck driving, brick laying, sand-mining, and other forms of physically intensive labor. Wage-earning women, on the other hand, faced rampant unemployment, making them increasingly dependent on men for the means of survival – to pay rent, taxes, food bills, and school fees. We argue that these shifts to what Mark Hunter calls the “geography and political economy of intimacy” – a way of conceptualizing the intimate and the economic in an “ever-changing relationship to one another and to other socio-spatial processes” (Hunter Citation2010: 4) – drove formerly wage-earning women into commercial sex, cohabiting relationships that community members described as “forced marriages,” or to the shores of Lake Victoria, where the fishing industry and the HIV epidemic were both beginning to boom.

Research setting and methods

The data presented in this article were collected after ethnographic research exploring the social-ecological contexts shaping adolescents’ transitions to adulthood revealed the widely held belief that unemployment predisposes young people to HIV. Observations, interviews (N = 43), focus group discussions (N = 24), and life history interviews (N = 26) undertaken from June-August 2019 in 6 southcentral Ugandan communities reflected widespread concerns with dwindling opportunities for formal employment, particularly for young men.Footnote1 Community leaders and young people cited unemployment as preventing young men from amassing the resources they need to marry and start families, not only causing the “crisis of masculinity” social scientists have documented across the African continent (Cole Citation2005; Hansen Citation2005; Hunter Citation2010; Mains Citation2007; Masquelier Citation2005; Wyrod Citation2016), but also lengthening the amount of time men spend in short term, non-marital, and concurrent sexual arrangements, forms of intimacy linked to HIV vulnerability.

Unemployment rates among young Ugandans are reported to be as high as 80%, a figure that includes unskilled laborers as well as university graduates (World Bank Citation2009). Bookshops in Kampala, Uganda’s capital and largest city, display locally published volumes with titles such as Opportunities and measures to overcome graduate unemployment (Nsamba Henry; see also Frye and Urbina Citation2019). Going abroad for work in domestic or military service has become not only desirable but frequent. For example, in 2019, Uganda’s national Daily Monitor reported “More than 100,000 citizens working in the Gulf states” and printed a photo of young women standing in line to apply for jobs in the UAE at the Entebbe Airport. Migration to the Middle East is so common that Saudi Arabia, Qatar, and the UAE have begun to erect schools in southcentral Uganda to facilitate Arabic fluency.

The only structures in southcentral Uganda larger than its freshly stuccoed Arabic-language school buildings are now-neglected coffee factories, once the center of the district’s small towns. Seized by the government in the early 2000s as collateral for debts incurred during structural adjustment, factories built to process the country’s highest-earning export now sit empty, many with still-functional machinery, weigh scales, and vehicles. These observations of the built environment resonated with community members’ assessment that unemployment is the key social determinant of HIV among young people, presenting a new set of research questions: How have patterns of employment changed as the coffee industry contracted? What caused coffee processing factories to close? And what were the effects of those closures for citizens of southcentral Uganda, especially as factories shuttered during the height of Uganda’s HIV epidemic?

To answer these questions, our research team reconstructed the recent history of the coffee sector in southcentral Uganda (1980–2005) and the overlapping period of growth of the area’s contemporary fishing communities (1995–2019) by combining evidence from oral history interviews with demographic data, policy documents, secondary source materials, and an archive of national periodicals, policy papers, dissertations, and white paper publications held at Makerere University’s Africana Library. Oral history interviews were conducted in English and Luganda with 14 former employees of state-regulated coffee factories, nine men and five women, who had worked in a variety of different roles at the factories, including as security guards, manual laborers, accountants, and managers. To locate former factory employees, we visited a shuttered factory in the small town of Kalisizo to ask nearby residents about its history. Then, using snowball sampling, we located and interviewed former technocrats for the state-run coffee cooperative, who facilitated connections to others formerly involved in coffee processing and union management, including formerly high-ranking officers and union managers. 12 additional oral histories were collected from coffee farmers, the owners of private coffee factories, bar owners, and migrants to Lake Victoria’s fishing communities. To gather information about changing marriage practices, we interviewed eight local religious and cultural leaders who oversee wedding and bridewealth ceremonies.

In order to determine the scale and gendered patterns of unemployment caused by the closure of coffee factories, our team gathered evidence to map the coffee sector as it operated from 1980–2005 in Rakai and Masaka districts. We collected information for 10 coffee factories in the area, controlled by 2 different cooperative unions, as well as on union-wide operations. Data included estimates of factory size, operations, machinery, management, and the composition of the workforce, including the number, age, and gender of waged laborers. We also collected data on workers’ salaries, housing, and places of leisure. For comparison, we gathered data on the workforce and operations of four privately owned factories and two major coffee storage and trading centers in the area.

To trace patterns of migration to Lake Victoria’s fishing communities, we asked former factory workers who had remained in coffee factory towns to connect us with people who migrated to the lakeshores between 1995–1998, and we interviewed 8 elder members, including locally elected officials, of 3 fishing communities. These oral histories conveyed respondents’ impressions of population growth, industrial development, and changes in the built environment. Several respondents were interviewed more than once to compare and verify data from other sources, including international trade statistics and agricultural export reports published by the World Bank, the IMF, USAID, the Bank of Uganda, the Uganda Bureau of Statistics, the Uganda Coffee Development Authority, the African Fine Coffees Association, and the International Coffee Organization. We also consulted experts on the history of the coffee sector from Makerere University’s Department of International Development and the Uganda Coffee Development Authority, the state agency currently regulating coffee farming, processing, and marketing.

Women, work, and changing patterns of intimacy in industrializing Uganda

To understand how the collapse of the coffee sector reconfigured the political economy of intimacy, we must first locate female labor migrants in southcentral Uganda’s social history (1900–1995). Mobile, wage-earning women have not yet been well represented in the scholarship on its HIV epidemic because the literature linking southern and East African labor migrations to HIV/AIDS has overwhelmingly presumed that labor migrants are male (see Hunter Citation2007, Citation2010). This assumption, reflected in work going back to colonial medical research into the syphilis and gonorrhea epidemics of the 1940 s, and continued in contemporary studies of HIV, holds that male labor migrants transmit HIV acquired while working in town to wives at home in the village (Packard and Epstein Citation1992). Yet Ugandan women have since at least the colonial period earned waged incomes in agricultural processing factories, through farming, and by other means that enabled them to live relatively independently.

In fact, historical evidence indicates that long before Uganda became a British protectorate in 1900, women lived independently, acted as heads of households, and divorced, eloped, and otherwise entered and exited different types of marriages with regularity in Buganda, the kingdom that encompasses southcentral Uganda (Stephens Citation2016). Some forms of marriage granted women higher social status and afforded them household help while others essentially enslaved them to their husbands. The significant flexibility of domestic and sexual relationships often bewildered late nineteenth century missionaries, who had to determine marital status before baptizing new converts (Stephens Citation2016). Some women eschewed marriage altogether. As described by Christine Obbo (Citation1980), “free women,” or banakyeombekedde, conducted sexual liaisons with whomever they pleased, usually men from outside their villages. Because these liaisons did not involve domestic service to men to whom they were not married, the relationships were widely accepted – at least until the colonial period. Moreover, the land tenure systems established by the Buganda Agreement allowed women to inherit and buy land, which meant that “free women” continued to have legitimate, socially sanctioned means to support themselves. At the same time, another less neutral term for unmarried women has been used since the precolonial period: bakirerese, or “restless people” (Obbo Citation1980). Female bakirerese moved from home to home, forming cohabiting relationships with men who supported them economically, particularly by buying them fashionable clothing. In contrast to “free women,” bakirerese have long been negatively stereotyped as prostitutes because they exchanged domestic services along with sex for money with men to whom they were not officially married. As the existence of bakirerese and banakyeombedde illustrates, not only were marriage and cohabitation practices long in flux, but many women lived independently and migrated freely well before twentieth century urbanization altered gendered patterns of labor, residence, and intimacy.

The Ugandan countryside urbanized over the course of the twentieth century as men and women moved to plantations and trading hubs, which facilitated colonial agricultural trade of sugar, cotton, tea, and especially coffee. Coffee became Uganda’s prized cash crop in 1911, following a spike in global coffee prices driven by the United States’ emergence as the world’s leading coffee buyer (Bergquist Citation1978). At the onset of World War I, needing to marshal revenues to fund war efforts, Britain rapidly expanded coffee production in Uganda. In the years following the war, coffee and tea farming replaced sugar and cotton crops on colonial plantations, largely because British colonizers were “not prepared to engage in forcible labor recruitment” for the more physically intensive labor required to pick sugarcane and cotton, as they wrote in letters to London (Weiss Citation2003; Young et al. Citation1981). Plantations drew – often conscripted – seasonal labor migrants, placing them in temporary, dormitory-style housing near the farms. Plantation farming, however, proved far less lucrative than encouraging “native” farmers to produce coffee as a cash crop and relying on South Asian traders to buy, sell, and process it for export (Asiimwe Citation2002).Footnote2 By 1920, South Asian traders had established trading posts in small towns throughout central Uganda, where they bought coffee from African growers to process and sell to British exporters (Mamdani Citation1976). Between 1920 and 1930, South Asian traders received financing from the National Bank of India to build small-scale coffee processing factories, which drew laborers from the countryside to urbanizing factory towns. International and colonial investments in the coffee trade in the early twentieth century created new patterns of migration, residence, and socializing for both men and women.

Beyond the comforts of home

Such changing patterns of migration and social life were familiar to other urbanizing African contexts during the colonial period; industrial towns across Southern and East Africa drew male migrants for seasonal waged labor as well as women who generated livelihoods by providing “the comforts of home,” Luise White’s (Citation1990) term for feminine care and sex services. White showed how prostitution followed cash crop production, as women migrated to cities to cook, clean, and care for seasonal male migrants; male migrants lived in state-provided dormitory-style bachelor quarters without kitchens, suggesting the state assumed cooking, laundry, and companionship would take place elsewhere. Romantic exchanges thus took on the form of “family work,” and women provided wifely services to male migrants while using the resources they acquired from men to support their own households. In fact, as White demonstrates, many women who earned incomes by providing the comforts of home eventually became urban property owners and landlords in their own right.

Women in colonial urban Uganda likewise had sexual affairs, provided domestic services, and otherwise made money through men outside of marriage (Davis Citation2000; Southall and Gutkind Citation1956). Yet further historical evidence shows that women also earned incomes through waged labor and by farming land they owned (Mair Citation1940). As early as 1925, Luganda newspapers lamented that in some villages there were as many households headed by independent women as by men (Doyle Citation2013: 156). While it was relatively uncommon for women to find industrial work in the first half of the twentieth century, by 1950 the economist Walter Elkan had observed that over 250 women were employed by a British tobacco factory in eastern Uganda. Following a strike organized by male employees, the factory had sought a “more docile” labor force (Elkan Citation1956).

Waged labor in agricultural processing factories gave women who did not inherit or could not afford to buy land options for living independently. All but 2 of the 250 women factory workers Elkan interviewed in the 1950s reported living alone or with a sister. One even reported that she refused to accept money from her “town friend” because she felt it would “give him rights” over her and that he might steal her wages (Elkan Citation1956: 42). For this reason, most of the women he and his research assistants interviewed claimed that “friendships” with men were better than marriages, and that the factory enabled them to feed and clothe themselves (Elkan Citation1956: 42). Moreover, by the middle of the twentieth century both cohabiting relationships and divorce were common enough to come up in disputes taken to colonial courts over the repayment of bridewealth, indicating that it was common for women to live alone and support themselves and their families financially (Doyle Citation2013).

Women continued to enter the workforce both as waged laborers and, increasingly, as educated professionals in the latter half of the twentieth century. As described by Grace Bantebya Kyomuhendo and Marjorie Kenniston McIntosh (Citation2006), by the time of Uganda’s independence from Britain in 1962, enough women were earning incomes outside their homes that the Lukiiko (Buganda’s Parliament) introduced an income tax for working women, which sparked virulent debates in national newspapers. Many women rejected the tax because they had no female political representation, while others supported it on the grounds that it would grant them recognition as independent wage earners and therefore allow them to seek improvements in working conditions. Men objected not to the income tax but to their loss of employment to women. As one man wrote to the Uganda Argus in 1965, “I feel spellbound to say that some firms … have taken to employing women workers instead of ambitious men who wait the whole day outside. There are numerous such work seekers who seem ready to do any kind of job allotted for a wage. It is especially annoying to see women employed in some dangerous machine-work … or serving drivers with fuel” (quoted in Kyomuhendo and McIntosh Citation2006: 139). Newspapers themselves, both Luganda- and English-print, began promoting women’s participation in the cash economy as essential to Uganda’s national economic development. In 1970, the newspaper Taifa Empya featured a set of photographs on Ugandan “working women” that featured street vendors, tailors, hairdressers, healers, city sweepers, local politicians, bar attendants, secretaries, and farmers.

Women in the coffee economy

In the 1970s and 80s, women were encouraged to grow coffee as a cash crop as part of Uganda's national economic development, a campaign commemorated by the Bank of Uganda’s colorful five-shilling note featuring a woman picking ripened red coffee cherries, issued in 1982 (see ). While rural women entered the coffee-based cash economy by harvesting coffee cherries, often in partnership with their husbands though sometimes on their own plots of land, migrant women found opportunities for waged labor in coffee processing factories owned and managed by cooperative unions and controlled by the state. The coffee sector – plantations, processing factories, and export marketing – had remained in the hands of British and South Asian managers until World War II, when Ugandan farmers revolted and took control of the agricultural trade, which they modeled after the Danish cooperative movement system (Asiimwe Citation2002; Asiimwe and Wilfred Citation2006). By 1969, Uganda had ratified the Coffee Marketing Act, which gave the state monopoly power over the cooperative unions and therefore over the purchase, processing, and sale of coffee. State-backed unions controlled the coffee sector from the 1950 s to the late 1990s.

Of the roughly six thousand people employed by state-controlled, union-run coffee processing factories in southcentral Uganda in the late 1980s, women comprised at least three quarters of the workforce. From 1980–1995, coffee factories employed roughly 15% of the district’s population, or about 6000 people (Uganda Bureau of Statistics Citation2006). Most union factories employed several educated women who worked as clerks at the managerial level, but the vast majority of women workers were bapakasi, or itinerant laborers, hired to “sort” hulled coffee beans, a crucial step in the coffee commodity chain. As employees of coffee factories, bapakasi women had steady access to incomes, and many lived independently. For example, one survey of the area conducted in 1983 reported that at least 39% of households in the area were headed by women (Bond and Vincent Citation1991: 115).

While several of the women interviewed for this study had begun working at cooperative factories as early as 1970, our respondents reported that bapakasi women took on sorting work en masse in 1984, following an uncharacteristically dry season that made the sorting work performed by women more demanding than usual. Union factories had also received foreign loans for machinery and infrastructure in the 1980 s, which expanded processing and created more sorting jobs for women. Unions hired women (and sometimes children) because female labor was often cheaper. Despite disparities in pay, however, many women earned enough to support themselves and their families. Mama Moses, for example, a former coffee sorter, spoke with pride of her ability to afford school fees and rent in town on her own with her income from a union factory, especially after her divorce.

Coffee unions and the factory towns that developed around them also provided women with new opportunities for sociality, intimacy, and residence. The unions provided female and male factory workers with co-ed, dormitory-style lodgings (see ). Factory workers also rented similar single-room dwellings called muzigos in town. According to our respondents, men and women socialized together regularly, including at union-sponsored parties held at local bars. Respondents remembered that life was good, if not “much better,” when the cooperative union factories were open because “people had money” for school fees, for rent, and for leisure. By all accounts, union factories were economic engines driving the towns that had urbanized around them.

Figure 2. Unions provided dormitory-style housing to men and women near coffee factories, such as the old muzigo (single-room) style building depicted. Kalisizo, Uganda. Photo by the authors.

By 1998, however, union factories throughout southcentral Uganda had closed, creating widespread unemployment, especially among women. To be sure, some women who lost work at the cooperatives were hired by private factories, but not many. Private factory owners, interested in maximizing profits and aided by improving computer and machine technologies, automated administrative tasks formerly carried out by educated women, eliminating the need to employ female clerks. Of greater consequence for bapakasi women, private factories outsourced sorting work to Kampala. As a result, the vast majority of female factory workers in southcentral Uganda were left without the incomes they had formerly relied upon to pay for housing, school fees, and entertainment. Life went from being good, according to former employees, to agonizing. Mama Catherine put it this way, “In the past, you bought and sold coffee and knew that your child will go to school … We didn’t have diseases. If you wanted to enjoy life through fun, you would do that without fear.” The closure of union factories caused mass economic dislocations from inland southcentral Uganda, which profoundly reconfigured patterns of migration, intimacy, household formation, and social life – and therefore population health. As respondents linked thesereconfigurations to the collapse of the state-controlled coffee industry, another question arose: What caused the coffee sector to collapse?

Structural adjustment and the collapse of Uganda’s coffee sector

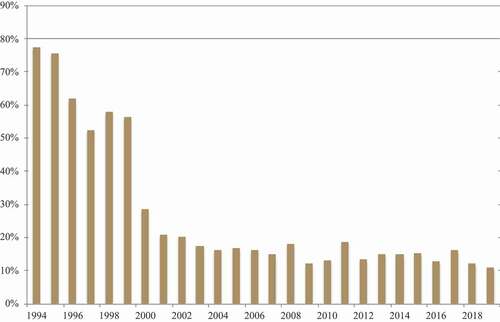

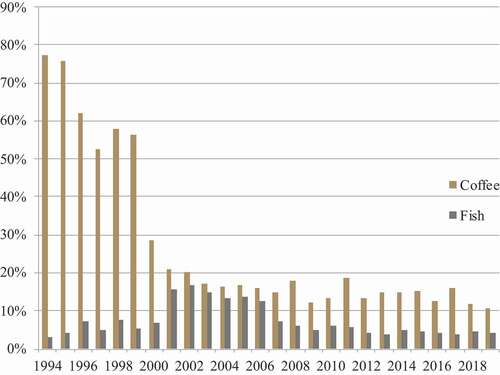

From the mid-1990 s to the early 2000 s, coffee went from generating almost 80% of Uganda’s export revenues to less than 20% (). Uganda’s coffee sector collapsed following economic restructuring and credit agreements negotiated under structural adjustment that privatized Uganda’s coffee market and instituted logistics requirements that impeded its long-running cooperative unions from buying and selling coffee. Structural adjustment in Uganda officially began in 1981 under President Milton Obote, who, in exchange for debt relief following the global oil crisis, ceded control of the coffee sector to the World Bank, the IMF, and USAID, which began setting prices and managing capital investments in crops, machines, and transportation (Asiimwe Citation2002; Bunker Citation1984; Johnson and Wilson Citation1982). Uganda’s first round of structural adjustments did little to mitigate Uganda’s foreign debt, however, which continued to grow through the 1980 s. In 1990, Uganda began a second round of adjustments under the “Washington Consensus,” an agreement established by the IMF, World Bank, and the US Treasury to offer credits to indebted nations in exchange for commitments to minimizing state budget expenditures and lowering prices on exportable goods.

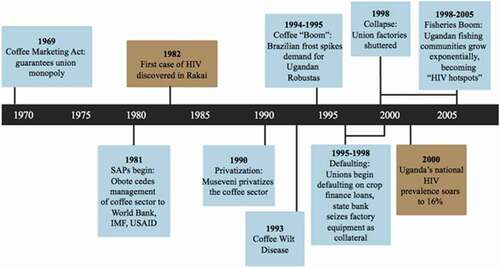

Figure 3. Timeline of key events: Blue boxes show developments in the coffee sector. Gold boxes track the HIV epidemic.

Under the Washington Consensus, President Yoweri Museveni entered into the World Bank’s Agricultural Sector Adjustment Credit program by repealing the Coffee Marketing Act of 1969, which had guaranteed the cooperative unions’ monopoly over the coffee trade. The government began issuing export licenses to private buyers, who thanked the Museveni administration prodigiously in ads taken out in the state-run newspaper New Vision. For example, Kyagalanyi Coffee Limited published an ad commemorating 26 January, the date Museveni’s National Resistance Movement (NRM) government overthrew his predecessor, which read: “Long Live your Excellency. Long Live the peace-loving Ugandans. Long Live the liberalized Ugandan Coffee Industry” (New Vision 1998). The “liberalization” of Uganda’s coffee industry brought multinational private buyers flush with cash into the market for buying coffee from farmers, weakening the monopoly held by the cooperative unions, which had previously bought and sold coffee at fixed prices – and often on credit – from farmers.

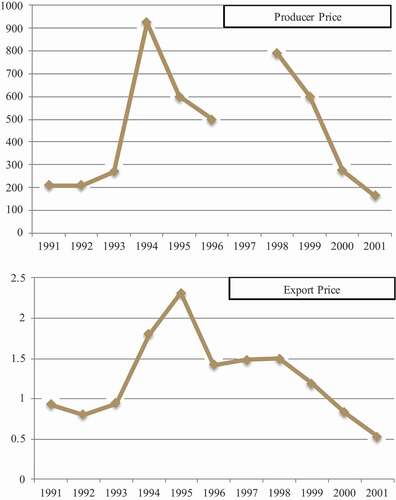

The privatization of Uganda’s coffee sector created a short-lived economic boom for coffee growers, intensified by two significant ecological events. First, Coffee Wilt Disease destroyed at least half the Robusta crops in central Uganda in 1993, spreading to 22 of 30 Robusta producing districts (Phiri and Baker Citation2009).Footnote3 The Rakai and Masaka districts were least impacted, however, which brought buyers from other Robusta-producing regions and generated increased demand for the crop. Second, the Brazilian Frost of 1994 destroyed at least a third of the Robusta crops usually available on the world market, sending the world price for coffee soaring. That year, Brazil was the world’s leading producer, Uganda the fifth (New York Times 1994). During this period, described by economists as Uganda’s “coffee boom” (Belshaw et al. Citation1999), exporters scrambled to buy coffee, spiking the prices paid to producers ().

The privatization of the coffee sector and the brief rise in coffee prices had long-lasting, detrimental effects for Uganda’s coffee sector as suppliers responded to growing demand for Robustas by increasing the speed of production, which ultimately reduced the quality of Ugandan coffee crops. To speed production, coffee growers sold coffee cherries that had not been fully dried, increasing the water content of coffee beans, which diminished their quality. The worldwide standard for water content in Robusta coffee is 13%, with even a half percent making a significant difference in quality; by 1995, Uganda was exporting coffee with 17% water content (Iyamulemye Citation2017). Moreover, industry officials reported that buyers and sellers both began mixing processed coffee beans with small stones, referred to as BHP, or byproduct, to increase coffee weight and therefore its sale price. In a few short years, the increased water content and poor BHP grades associated with Ugandan coffee gave it a global reputation for being low quality, and European and American buyers – the world’s largest importers – all but stopped buying it. The price of Ugandan coffee plummeted. By 1997, journalists reported that the government had launched a “quality campaign of cracking down on traders adulterating coffee” in southcentral Uganda (New Vision 1997), but it did little to stop the price of Ugandan coffee from falling on the world market ().

Figure 4. Coffee has long been Uganda’s most exported commodity. This chart shows its percentage of Uganda’s Total Export Revenue for as long as the Bank of Uganda has collected data. The coffee sector boomed from 1994–1995; southcentral Uganda's union factories were shuttered by 1998 (Bank of Uganda 2019).

Figure 5. Graphs showing prices paid to farmers (Producer Price) and Ugandan Robusta’s price on the world market (Export Price). Graphs constructed from data found in IMF Staff Country Report No. 97/48 (1997) and No. 08/84 (2003); no producer price data was available for 1997.

Meanwhile, the coffee unions began facing problems on the supply side as private buyers were able to pay farmers higher prices – problems exacerbated by logistics requirements attached to IMF and World Bank debt relief agreements. The unions had already been purchasing coffee on credit from farmers, and farmers were growing irritated by delayed repayments. As early as 1980, a journalist for the newspaper Munno reported, “Members of cooperatives … are tired of being patient. This may cause the collapse of all the groups.” Growing mistrust of coffee unions made farmers all the more eager to sell to private buyers, flush with capital, when the coffee market privatized.

Unions’ ability to compete with private buyers for coffee crops was exacerbated by the Uganda Railways Project, a $7 million credit agreement negotiated between the government of Uganda and the IMF and World Bank, that mandated union-processed coffees ship from Kampala to Mombasa, the port city, by train (International Monetary Fund Citation1989). The credit was intended to facilitate the reconstruction of the railway, which meant that unusable tracks and construction work often delayed shipments by weeks. International buyers released payments only once coffee was weighed for export in Mombasa, so unions often faced significant delays repaying farmers. By contrast, private buyers, exempt from the IMF/World Bank’s logistics requirements, delivered coffee to Mombasa by truck in a matter of days. Consequently, private buyers generated returns far more quickly than the unions, which allowed them to pay farmers upon delivery of coffee crops, rather than when processed coffee beans were ready for international export.

Constrained by the IMF’s Uganda Railways Project and increasingly unable to compete with private buyers, the unions were forced to take on “Crop Finance” loans from the World Bank’s Agricultural Sector Credit Program, which they began defaulting on in 1995 – just as the quality, and thus world price, of Uganda’s coffee began to plummet. Unable to repay the loans, the state-run Uganda Commercial Bank seized union equipment, even entire factories, as collateral, all but halting union operations. The Kalisizo Coffee Factory in Rakai District, for example, which had employed nearly 800 people, started laying off workers in 1995. By 1998, it, along with most other southcentral Ugandan union factories, had completely shuttered.

Lakeshore migrations and Uganda’s fisheries boom

As coffee was the primary industry in southcentral Uganda, women who lost work at coffee processing factories had few other options to earn a living. Between 1995–1998, bapakasi women left southcentral Uganda’s small factory towns to find work in the growing capital city, on nearby plantations, or, especially, in the communities developing on Lake Victoria’s shores. “I will not lie to you,” one respondent explained, couching his statement in terms that emphasized both the salacious and sorrowful nature of these migrations, “Most women went to fishing communities. They were very many.” According to long-time residents, while there were very few, if any, women living in the seasonal labor camps that housed fishermen in the 1980 s, by the early 2000 s women constituted at least half the population residing on the lakeshores.

While East African people have fished Lake Victoria for centuries, the established fishing communities now familiar to epidemiologists as “HIV hotspots” have a much more recent history. By the accounts of their oldest residents, fishing community populations boomed from the late 1990 s through the early 2000 s, when inland labor migrants traveled to the lake. According to local officials and long-time residents, the populations of Ddimu, Kasensero, and Malembo, port towns in Rakai, doubled in size between 1995 and 1997, and then exploded with residents in the late 90s and early 2000 s. For example, in 1995, Ddimu’s population was estimated to be 200 semi-permanent residents, 400 people by 1997, and around 1500 people by the year 2000. (By 2019, the population had grown to around 20,000 people during its busiest seasons, a figure that includes young children.)

Migrations to the lakeshores converged with a significant boom in Uganda’s fishing industry: by the late 90s, fish had become Uganda’s second leading export after coffee (see ). Market deregulation under structural adjustment facilitated the construction of privately-owned fishing factories, while foreign investments in loading docks, cold storage chains, fish processing plants, and in fish crops themselves led to an increase in the availability of exportable fish in Lake Victoria. Nile Perch, preferred by Northern European consumers to the lake’s indigenous tilapia, had been introduced to Lake Victoria decades earlier, but only by the mid-1990 s had the crop fully matured; since the 1970 s Nile Perch had only been sold locally in Uganda, but by the late 1990 s Nile Perch filets were available frozen or chilled on at least four continents (Johnson Citation2014: 38). Moreover, Lake Victoria had been relatively unfishable anyway until the late 90s: from 1994–1995, during the Rwandan genocide, fishermen found work instead helping NGOs bury bodies washed ashore (Mirembe Citation1994). In the following years, increases in exportable fish crops created a boom in the fishing industry, while the growing availability of refrigeration systems allowed fisherfolk to settle more permanently in lakeshore communities.

Figure 6. Fish became Uganda’s second highest source of export revenue in 2001, after the collapse of the coffee sector (Bank of Uganda 2019).

The rapid growth of fishing communities was further evident in changes to the types of housing available. For example, in the mid-1990 s, migrants to fishing communities arrived to find grass-thatched dwellings erected on the sands of the lakeshores, which were used periodically by fishermen. Otherwise most of the land was “bush,” or dense forest. “Then,” as a woman who accompanied her husband to Ddimu in 1995 described, “people started settling in this place slowly. Remember, after the collapse of coffee factories, the market for coffee went down. As a result, the former employees started coming to this place. A person would first seek permission from the local council chairperson to have a piece of land where to build the house.” By the early 2000 s, forest lands were cleared and blocks of single room muzigos were constructed from durable materials such as wood, mud, and cement; electricity became widely available, which powered refrigeration systems for fish, allowing fishermen to travel less frequently in search of fresh catches. Mosques, churches, pharmacies, retail shops, movie halls, and bars and restaurants, typically run by women, opened to cater to the growing community.

According to elder residents, women who migrated to fishing villages after the coffee factories closed found some piecemeal work in the fishing industry, particularly by catching smaller fish to cook and sell to other residents. Others were banakyeombekedde, older “free women” who lived alone, earning livelihoods by selling locally brewed beer, firewood, or seashells collected for chicken feed. However, as the “sex-for-fish” literature has documented, women’s most consistent access to resources – fish – was largely guaranteed by exchanging intimacies with fishermen. Our respondent’s insistence that he “would not lie” that most disenfranchised bapakasi women migrated to the lakeshores further suggests the stigma associated with women’s labor in the area; it is and was widely assumed that these migrations involved unsavory forms of transactional sex. Overt sex work aside, local strictures precluded formalizing other romantic relationships in fishing communities as culturally sanctioned marriages: residents reported a common saying, “ku Ddimu bawasaako?” (literally, “do you think it is appropriate to marry from the Ddimu port?”), invoked to encourage fishermen to return to their inland villages to seek appropriate wives. Fisherfolk instead entered a form of “conditional” marriage, referred to as “obufumbo obwensonga,” which union residents described as temporary, and often multiple. Residents further noted that many women, unable to compete with men for jobs in fisheries, “started going to work in lodges,” or brothels, meaning they entered the growing market for commercial sex.

Women’s economic disenfranchisement: “engineered the spread of HIV”

Whether on the lakeshores or in factory towns, women’s economic disenfranchisement following structural adjustment changed where and how individuals socialized, married, formed households, and engaged in other forms of romantic-economic exchange – all changes that have long been associated with HIV vulnerability, including by residents of the area. Longtime residents of southcentral Uganda spoke with great sadness and sympathy for the women affected by the factory closures. For example, Mr. Ssekajja, a former union factory manager, explained:

Sex work was not a lot during the cooperative era because people were independent. They could get money to pay for their children’s school and food. There was permanency with sexual partners. After the collapse of the unions, they rebelled against each other. Everyone blamed each other for not buying food, not paying school fees, among others. They decided to look after themselves, thus women ended up in sex work for survival. Before, women survived because they had permanent partners. Both partners were earning money and they could look after their family. A man could bring 20,000USh ($5.28) and a woman adds on 30,000USh ($7.91) and catered for the family needs like food, school fees, and rent. Women decided to separate from their partners because they could not provide food, clothes, hair, among others. After the collapse of the union, women started getting several sexual partners: one to cater for hair, the other to buy food, and one to pay rent. That kind of life engineered the spread of HIV in families that resulted in deaths.

Mr. Ssekajja reported perceiving that women who had been economic equals to their male partners while employed by state-run coffee factories became dependent on men – and on the transactional sexual economy – once they lost access to wages. His observation that women ended up in “sex work for survival” reflects a well-established, if well-challenged, association between economic despair, transactional sex, and HIV vulnerability in sub-Saharan Africa (see Obbo Citation1990; Schoepf Citation1988; Susser Citation2009; Swidler and Watkins Citation2007).

Long a capacious category in East Africa, “transactional sex” involves a spectrum of activities ranging from ongoing relationships to one-time sexual encounters with a price negotiated ahead of time (Nyanzi et al. Citation2004; Stoebenau et al. Citation2016). Moreover, the lines between “transactional sex” and other intimate-economic arrangements have always been blurry, including those found in loving and romantic relationships, not least in marriages (Cole Citation2005; Cole and Thomas Citation2009; Hirsch and Wardlow Citation2006). Even in this context, however, respondents reported that changes to how women socialized, exchanged sex, and formed households reflected their economic despair. For example, respondents described bapakasi women, both those who migrated to the lakeshores and those who remained closer to town, entering “forced marriages” (embeera yabaakakanga okufumbirwa, literally “the situation was forcing them to get married”).

Evidence of women’s increased dependency on men’s resources also emerged from bar owners’ memories of the disappearance of women as paying customers. At once-bustling local hotspots like the Tropic Inn and the Go Down Bar, men and women had socialized together on union factory paydays, drinking beer and listening to wambuuza music, melodic love songs of marriage promises and family futures. Without disposable incomes, however, women ceased patronizing bars themselves, and women who spent time in bars became known as “good-time girls,” or women who hung around hoping to benefit from the generosity of male patrons (Ogden Citation1996). Women also took jobs as bartenders, gendered labor long synonymous with sex work for demographers surveying the area (Sewankambo et al. Citation2000). Respondents also remembered sex work becoming newly “visible” as the factories closed. Several recalled bapakasi women who lost jobs at union factories moving to an area of town known as kubassi, for “bus,” a long stretch of single rooms where sex workers entertain clients. For these women, “commercial sex” became the only remaining dependable form of renumeration, replacing the factory work that had formerly allowed them to live independently. Compounding women’s lost access to wages during this time, the growth of informal markets for coffee smuggling called magendo further consolidated money in the hands of men, rendering women “victims to the sexual exploitation and opportunism brought about by the sudden increase in wealth in the area” as some historians have argued (Kuhanen Citation2008: 311; see also Donovan Citation2021).

By 1998, southcentral Uganda’s formal coffee sector had entirely collapsed, creating a gendered imbalance in access to resources that transformed the geography and political economy of intimacy at a time when Uganda’s HIV epidemic was rapidly spreading. In the early-1990 s, AIDS was killing one adult per every three households in Rakai; by 2000, the Rakai district's prevalence rates were among the highest in the world - 16% of people between the ages 15 and 59 were HIV positive (Iliffe Citation2006). In the two ensuing decades, HIV infections continued to increase disproportionately in the area, alongside the exponential growth of Uganda’s fishing communities. Now, Uganda’s fishing communities are the center of HIV “hotspot” research.

Conclusion

Since 2015, UNAIDS has discouraged the use of the term “hotspots,” urging researchers to “Use this term with caution, as it may be seen as having a negative connotation for the people in the hotspot. Instead, describe the actual situation you want to convey.” Rather than “hotspot,” UNAIDS prefers researchers and practitioners “Use location or local epidemic, and describe the situation or context” (UNAIDS Citation2015: 9). While a helpful and humanistic corrective, this framing nonetheless proposes a cursory, terminological shift rather than a paradigmatic one. It still risks laminating social practices onto geographic locations, suggesting that such “social determinants” are specific to place rather than dynamic products of history.

In challenging the HIV hotspots paradigm, we suggest that serious engagement with the social determinants of health must denaturalize them, primarily by investigating and naming the specific institutions and policies that have and continue to produce them. This mode of investigation requires looking well beyond proximate health behaviors to “meso-level” determinants, or the social processes through which structural factors shape population health, such as how the economic organization of production reorganizes where and how people live (Hirsch Citation2014). Taking this approach, we have demonstrated how the Agricultural Sector Credit Program and the Uganda Railways Project, policies configured by the IMF, World Bank, and US Treasury under structural adjustment, contributed to the collapse of Uganda’s coffee sector and therefore to mass economic disenfranchisement and dislocation among women. In turn, these profound social changes reconfigured the political economy of intimacy in ways that affected the spread of HIV in southcentral Uganda. Concentrating on meso-level determinants in this way allows researchers to construct chains of accountability that stretch, for example, from global economic institutions and world commodity markets to national manufacturing sectors to community-level health vulnerabilities – and likewise to press for interventions that seek to transform policies rather than individual behaviors.

Acknowledgments

Dr. Erin V. Moore and co-authors wish to thank the many people from Rakai and Masaka who spoke with us about this difficult period in southcentral Uganda’s history. We are especially indebted to our interlocutor pseudonymized above as Mr. Ssekajja, who generously welcomed our interest in coffee unions by helping to facilitate much of this study. We also thank Dr. Godfrey Asiimwe, Professor of Development Studies at Makerere University, for sharing his expertise on Uganda’s cooperative movement. We are grateful to the editors of Medical Anthropology and to three anonymous reviewers for their insightful comments on this article, and to Bridget Morse-Karzen for her excellent editorial assistance. Dr. Moore also thanks Malavika Reddy, Anna Jabloner, Adam Sargent, Joseph Jay Sosa, Thomas McDow, and Jennifer Cole for helpful feedback on earlier drafts, and Grant Sabatier for locating the image of Uganda’s five-shillings note.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Erin V. Moore

Dr. Erin V. Moore is the Dr. Carl F. Asseff Assistant Professor of Anthropology and the History of Medicine at the Ohio State University.

Rodah Nambi

Rodah Nambi and Dauda Isabirye are researchers with the Social and Behavioral Sciences (SBS) Department at the Rakai Health Sciences Program (RHSP).

Dauda Isabirye

Rodah Nambi and Dauda Isabirye are researchers with the Social and Behavioral Sciences (SBS) Department at the Rakai Health Sciences Program (RHSP).

Neema Nakyanjo

Neema Nakyanjo is the Head of the SBS Department at RHSP.

Fred Nalugoda

Dr. Fred Nalugoda is the Head of Grants, Science and Training at RHSP.

John S. Santelli

Dr. John S. Santelli is a Professor of Population and Family Health and Pediatrics at Columbia University’s Mailman School of Public Health.

Jennifer S. Hirsch

Dr. Jennifer S. Hirsch is a Professor of Sociomedical Sciences and Co-Director of the Columbia Population Research Center.

Notes

1. All research activities were approved by the Institutional Review Boards at Columbia University, the Uganda Virus Research Institute and Ethics Committee, and by the Uganda National Council of Science and Technology (UNCST). All respondents gave consent to be interviewed. Most of the oral history interviews were recorded, transcribed, and translated. However, given the politicized nature of the coffee industry’s history, some respondents requested their identities be protected and that interview notes be taken by hand rather than tape-recorded; all names used are pseudonyms.

2. South Asians, now referred to as Ugandan Asians or Ugandan Indians, came to Uganda under the British beginning in the late nineteenth century to work on the East African railroad.

3. Arabica beans, grown in Northern and Eastern Uganda, were processed and transported differently than Robustas, which meant that structural adjustment had different effects for these regions (see Bunker Citation1984).

References

- Asiimwe, G. B. 2002 The Impact of Post-Colonial Policy Shifts in Coffee Marketing at the Local Level in Uganda: A Case Study of Mukono District, 1962-1998. Maastricht: Shaker Publishing BV.

- Asiimwe, G. B., and N. K. Wilfred 2006 A Historical Analysis of Produce Marketing Co-operatives in Uganda: Lessons for the Future. Kampala: Network of Ugandan Researchers and Research Users.

- Belshaw, D., P. Lawrence, and M. Hubbard 1999 Agricultural tradables and economic recovery in Uganda: The limitations of structural adjustment in practice. World Development 27(4):673–90. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/S0305-750X(99)00030-3.

- Béné, C., and S. Merten 2008 Women and fish-for-sex: Transactional sex, HIV/AIDS and gender in African f isheries. World Development 36(5):875–99. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2007.05.010.

- Bergquist, W. C. 1978 The Coffee Conflict in Colombia,1886-1910. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

- Bond, G. C., and J. Vincent 1991 Living on the edge: Changing social structures in the context of AIDS. In Changing Uganda: The Dilemmas of Structural Adjustment and Revolutionary Change H.B. Hansen, ed., Pp. 113–29. Oxford: James Currey Limited.

- Bourgois, P., and N. Scheper-Hughes 2004 Comments: An anthropology of structural violence. Current Anthropology 45(3):318–20.

- Bradford, K., and R. E. Katikiro 2019 Fighting the tides: A review of gender and fisheries in Tanzania. Fisheries Research 216:79–88. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fishres.2019.04.003.

- Bunker, S. G. 1984 Agricultural and political change in the Ugandan economic crisis. American Ethnologist 11(3):586–89. doi:https://doi.org/10.1525/ae.1984.11.3.02a00120.

- Burke, V. M., N. Nakyanjo, W. Ddaaki, C. Payne, N. Hutchinson, M. Wawer, F. Nalugoda, et al. 2017 HIV self-testing values and preferences among sex workers, fishermen, and mainland community members in Rakai, Uganda: A qualitative study. PLoS One 12(8):1–15. doi:https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0183280.

- Camlin, C. S., Z. A. Kwena, and S. L. Dworkin 2013 Jaboya vs. jakambi: Status, negotiation, and HIV risks among female migrants in the “sex for fish” economy in Nyanza province, Kenya. AIDS Education and Prevention 25(3):216–31. doi:https://doi.org/10.1521/aeap.2013.25.3.216.

- Chang, L. W., M. Grabowski, R. Ssekubugu, F. Nalugoda, G. Kigozi, B. Nantume, J. Lessler, et al. 2016 Heterogeneity of the HIV epidemic in agrarian, trading, and fishing communities in Rakai, Uganda: An observational epidemiological study. The Lancet HIV 3(8):e388–e396. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/S2352-3018(16)30034-0.

- Cole, J. 2005 The jaombilo of Tamatave (Madagascar), 1992-2004: Reflections on youth and globalization. Journal of Social History 38(4):891–914. doi:https://doi.org/10.1353/jsh.2005.0051.

- Cole, J., and L. Thomas, eds 2009 Love in Africa. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

- Davis, P.J. 2000 On the sexuality of “town women” in Kampala. Africa Today 47(3/4):28–62. doi:https://doi.org/10.2979/AFT.2000.47.3-4.28.

- Deane, K., and J. Wamoyi 2015 Revisiting the economics of transactional sex: Evidence from Tanzania. Review of African Political Economy 42(145):437–54. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/03056244.2015.1064816.

- Donovan, K. P. 2021 Magendo: Arbitrage and ambiguity on an East African frontier. Cultural Anthropology 36(1):110–37. doi:https://doi.org/10.14506/ca36.1.05.

- Doyle, S. 2013 Before HIV: Sexuality, Fertility and Mortality in East Africa, 1900-1980. London: British Academy.

- Dubal, S. 2012 Renouncing Paul farmer: A desperate plea for radical political medicine. Being Ethical in an Unethical World (blog). May 27. http://samdubal.blogspot.com/2012/05/renouncing-paul-farmer-desperate-plea.html. Accessed 12 February 2021.

- Elkan, W. 1956 An African Labour Force: Two Case Studies in East African Factory Development. London: King & Jarrett.

- Farmer, P. 1992 AIDS and Accusation: Haiti and the Geography of Blame. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Farmer, P. 2004 An anthropology of structural violence. Current Anthropology 45(3):305–25. doi:https://doi.org/10.1086/382250.

- Farmer, P. 2005 Pathologies of Power: Health, Human Rights, and the New War on the Poor. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Fiorella, K. J., C. S. Camlin, C. R. Salmen, R. Omondi, M. D. Hickey, D. Omollo, E. Milner, E A. Bukusi, Lia C.H. Fernald, J S. Brashares et al. 2015 Transactional fish-for-sex relationships amid declining fish access in Kenya. World Development 74:323–32. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2015.05.015.

- Forster, T., A. Kentikelenis, B. Reinsberg, R. Omondi, M. Hickey, D. Omollo, E. M. Milner et al. 2019 How structural adjustment programs affect inequality: A disaggregated analysis of IMF conditionality, 1980–2014. Social Science Research 80:83–113. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssresearch.2019.01.001.

- Frye, M., and D. R. Urbina 2019 Fearing such a lady: University expansion, underemployment, and the hypergamy ideal in Kampala, Uganda. Journal of Family Issues 41(8):161–1187.

- Hansen, K. T 2005 Getting stuck in the compound: Some odds against social adulthood in Lusaka, Zambia. Africa Today 51(4):13–16. doi:https://doi.org/10.2979/AFT.2005.51.4.2.

- Hirsch, J. 2014 Labor migration, externalities and ethics: Theorizing the meso-level determinants of HIV vulnerability. Social Science & Medicine 100:38–45. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2013.10.021.

- Hirsch, J., and H. Wardlow, eds 2006 Modern Loves: The Anthropology of Romantic Courtship & Companionate Marriage. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

- Hunter, M. 2007 The changing political economy of sex in South Africa: The significance of unemployment and inequalities to the scale of the AIDS pandemic. Social Science & Medicine 64(3):689–700. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.09.015.

- Hunter, M. 2010 Love in the Time of AIDS: Inequality, Gender, and Rights in South Africa. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

- Iliffe, J. 2006 The African AIDS Epidemic: A History. Athens: Ohio University Press.

- International Monetary Fund 1989 Annual report, No. 7608-UG. Washington, DC: IMF. https://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/ar/archive/pdf/ar1989.pdf. Accessed 11 December 2019.

- Iyamulemye, E. 2017 The history of coffee in Uganda. African Fine Coffees Review Magazine 7(4):8–11. https://afca.coffee/the-history-of-coffee-in-uganda/. Accessed 14 November 2019.

- Johnson, J. L. 2014 Fishwork in Uganda: A multispecies ethnohistory about fish, people, and ideas about fish and people. PhD thesis, Department of Natural Resources and Environment, University of Michigan.

- Johnson, W. R., and E. J. Wilson 1982 The “oil crises” and African economies: Oil wave on a tidal flood of industrial price inflation. Daedalus 11(2):211–41.

- Kamali, A., R. N. Nsubuga, E. Ruzagira, U. Bahemuka, G. Asiki, M.A. Price, R. Newton, P Kaleebu, P Fast, et al 2016 Heterogeneity of HIV incidence: A comparative analysis between fishing communities and in a neighbouring rural general population, Uganda, and implications for HIV control. Sexually Transmitted Infections 92(6):447–54. doi:https://doi.org/10.1136/sextrans-2015-052179.

- Kentikelenis, A. E. 2017 Structural adjustment and health: A conceptual framework and evidence on pathways. Social Science & Medicine 187:296–305. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2017.02.021.

- Kuhanen, J. 2008 The historiography of HIV and AIDS in Uganda. History in Africa 35:301–28. doi:https://doi.org/10.1353/hia.0.0009.

- Kwena, Z. A., E. Bukusi, E. Omondi, M. Ng’ayo, and K. K. Holmes 2012 Transactional sex in the fishing communities along Lake Victoria, Kenya: A catalyst for the spread of HIV. African Journal of AIDS Research 11(1):9–15. doi:https://doi.org/10.2989/16085906.2012.671267.

- Kyomuhendo, G. B., and M. K. McIntosh 2006 Women, Work & Domestic Virtue in Uganda, 1900-2003. Oxford: James Currey.

- Long Live your Excellency Long Live the peace-loving Ugandans. Long Live the Liberalized Ugandan Coffee Industry. 1998 New Vision, January 26.

- Lubega, M., N. Nakyaanjo, S. Nansubuga, E. Hiire, G. Kigozi, G. Nakigozi, T. Lutalo, et al. 2015 Understanding the socio-structural context of high HIV transmission in Kasensero fishing community, South Western Uganda. BMC Public Health 15:1033. doi:https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-015-2371-4.

- MacPherson, E., Sadalaki, M. Njoloma, V. Nyongopa, L. Nkhwazi, V. Mwapasa, D. Lalloo et al. 2012 Transactional sex and HIV: Understanding the gendered structural drives of HIV in fishing communities in Southern Malawi. Journal of the International AIDS Society 15(Suppl 1): 1–19. doi:https://doi.org/10.7448/IAS.15.3.17364.

- Mains, D. 2007 Neoliberal times: Progress, boredom, and shame among young men in urban Ethiopia. American Ethnologist 34(4):659–73. doi:https://doi.org/10.1525/ae.2007.34.4.659.

- Mair, L. 1940 Native Marriage in Buganda. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Mamdani, M. 1976 Politics and class formation in Uganda. New York: Monthly Review Press.

- Masquelier, A. 2005 The scorpion’s sting: Youth, marriage and the struggle for social maturity in Niger. Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute 11:59–83.

- Merten, S., and T. Haller 2007 Culture, changing livelihoods, and HIV/AIDS discourse: Reframing the Institutionalization of fish-for-sex exchange in the Zambian Kafue Flats. Culture, Health, and Sexuality 9(1):69–83. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13691050600965968.

- Michalopoulos, L. T. M., S. N. Baca-Atlas, S. Simona, T. Jiwatram-Negron, A. Ncube, and M. Chery 2017 Life at the river is a living hell: A qualitative study of trauma, mental health, substance use and HIV risk behavior among female fish traders from the Kafue Flatlands in Zambia. BMC Women’s Health 17(1):1–15. doi:https://doi.org/10.1186/s12905-017-0369-z.

- Mirembe, S. 1994 Government declares lake water unsafe. Daily Monitor, May 16:17–20.

- Mojola, S.A. 2011 Fishing in dangerous waters: Ecology, gender and economy in HIV risk. Social Science & Medicine 72(2):149–56. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.11.006.

- Mojola, S.A. 2014 Love, Money, and HIV: Becoming a Modern African Woman in the Age of AIDS. Oakland: University of California Press.

- Nathenson, P., S. Slater, P. Higdon, C. Alidinger, and E. Ostheimer 2017 No sex for fish: Empowering women to promote health and economic opportunity in a localized place in Kenya. Health Promotion International 32(5):800–07.

- New Frost Hits Brazil Coffee 1994 New York Times, July 11. https://www.nytimes.com/1994/07/11/business/new-frost-hits-brazil-coffee.html. Accessed 17 January 2020.

- Norris, A., and E. Worby 2012 The sexual economy of a sugar plantation: Privatization and social welfare in Northern Tanzania. American Ethnologist 39(2):354–70. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1548-1425.2012.01369.x.

- Nunan, F. 2010 Mobility and fisherfolk livelihoods on Lake victoria: Implications for vulnerability and risk. Geoforum 41(5):776–85. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2010.04.009.

- Nyanzi, S., B. Nyanzi, B. Kalina, and R. Pool 2004 Mobility, sexual networks and exchange among bodabodamen is southwest Uganda. Culture, Health & Sexuality 6(3):239–54. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13691050310001658208.

- Obbo, C. 1980 African Women: Their Struggle for Economic Independence. Vol. 34. London: Zed Press.

- Obbo, C. 1990 Sexual Relations Before AIDS. Liege, Belgium: International Union for the Scientific Study of Population.

- Ogden, J.A. 1996 ‘Producing’ Respect: The ‘Proper Woman’ in Postcolonial Kampala. London: Zed Books.

- Packard, R. M., and P. Epstein 1992 Medical research on AIDS in Africa: A historical perspective. In AIDS: The Making of a Chronic Disease E. Fee and D.M. Fox, eds., Pp. 346–75. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Pfeiffer, J., and R. Chapman 2010 Anthropological perspectives on structural adjustment and public health. Annual Review of Anthropology 39:149–65. doi:https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.anthro.012809.105101.

- Phiri, N., and P. Baker 2009 A Synthesis of the Work of the Regional Coffee Wilt Programme 2000-2007: Coffee Wilt Disease in Africa. Wallingford, United Kingdom: Centre for Agriculture and Bioscience International. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/media/57a08b3fe5274a27b2000a51/Coffee_ExecSummary.pdf. Accessed 10 December 2019.

- Ratmann, O., J. Kagaayi, M. Hall, T. Golubchick, G. Kigozi, X. Xi, C. Wymant, et al. 2020 Quantifying HIV transmission flow between high-prevalence hotspots and surrounding communities: A population-based study in Rakai. The Lancet HIV 7(3):e173–e183. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/S2352-3018(19)30378-9.

- Schoepf, B. G. 1988 Women, AIDS, and economic crisis in Central Africa. Canadian Journal of African Studies 22(3):625–44.

- Serwadda, D., R. D. Mugerwa, N. K. Sewankambo, A. Lwegaba, J. W. Carswell, G. B. Kirya, A. C. Bayley, et al. 1985 Slim disease: A new disease in Uganda and its association with HTLV-III infection. The Lancet 326(8460):849–52. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(85)90122-9.

- Sewankambo, N. K., R. H. Gray, S. Ahmad, D. Serwadda, F. Wabwire-Mangen, F. Nalugoda, N. Kiwanuka, et al. 2000 Mortality associated with HIV infection in rural Rakai District, Uganda. AIDS 14(15):2391–400. doi:https://doi.org/10.1097/00002030-200010200-00021.

- Sileo, K. M., L. M. Bogart, G. J. Wagner, W. Musoke, R. Naigino, B. Mukasa, and R. K Wanyenze 2019 HIV fatalism and engagement in transactional sex among Ugandan fisherfolk living with HIV. SAHARA: Journal of Social Aspects of HIV/AIDS Research Alliance 16(1):1–9. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/17290376.2019.1572533.

- Southall, A. W., and C. W. Gutkind 1956 Townsmen in the making: Kampala and its Suburbs. East African Studies No. 9. Kampala: East African Institute of Social Research.

- Stephens, R. 2016 Whether they promised each other some thing is difficult to work out: The complicated history of marriage in Uganda. African Studies Review 59(1):127–53. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/asr.2016.6.

- Stoebenau, K., L. Heise, J. Wamoyi, and N. Bobrova 2016 Revisiting the understanding of “transactional sex” in sub-Saharan Africa: A review and synthesis of the literature. Social Science & Medicine 168:186–97. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2016.09.023.

- Susser, I. 2009 AIDS, Sex, and Culture: Global Politics and Survival in Southern Africa. Winchester: Wiley-Blackwell.

- Swidler, A., and S. C. Watkins 2007 Ties of dependence: AIDS and transactional sex in rural Malawi. Studies in Family Planning 38(3):147–62. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1728-4465.2007.00127.x.

- Uganda Bureau of Statistics 2006 2002 Uganda Population and Housing Census: Analytical Report, Population Size and Distribution. Kampala, Uganda: Uganda Bureau of Statistics. https://ubos.org/wpcontent/uploads/publications/03_20182002_CensusPopndynamicsAnalyticalReport.pdf. Accessed 12 December 2019.

- UNAIDS 2015 UNAIDS terminology guidelines. 9. https://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/media_asset/2015_terminology_guidelines_en.pdf. Accessed 7 July 2021.

- UNAIDS 2020 Global HIV & AIDS statistics – 2020 fact sheet. https://www.unaids.org/en/resources/fact-sheetresources/fact-sheet. Accessed 21 February 2021.

- Weiss, B. 2003 Sacred Trees, Bitter Harvests: Globalizing Coffee in Northwest Tanzania: Globalizing Coffee in Colonial Northwest Tanzania. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann.

- White, L. 1990 The Comforts of Home: Prostitution in Colonial Nairobi. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

- Whyte, S. R. 1991 Medicines and self-help: The privatization of health care in eastern Uganda. In Changing Uganda: The Dilemmas of Structural Adjustment & Revolutionary Change HB Hansen, ed., Pp. 130–40. London: James Currey.

- World Bank 2009 African development indicators 2008/2009. Washington, DC: World Bank. https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/bitstream/handle/10986/12350/46768.pdf?sequence=1&isAllowed=y. Accessed 12 December 2019.

- World Health Organization 2021 Social determinants of health. https://www.who.int/health-topics/social-determinants-of-health#tab=tab_1. Accessed 24 March 2021.

- Wyrod, R. 2016 AIDS and Masculinity in the African City: Privilege, Inequality, and Modern Manhood. Los Angeles: University of California Press.

- Young, C., N. P. Sherman, and T. H. Rose 1981 Cooperatives & Development: Agricultural Politics in Ghana and Uganda. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press.