ABSTRACT

While recent decades have seen a rapid rise in cases of infant tongue-tie and in surgery to correct it, a controversy is now raging over the condition. Opinion is especially divided over so-called posterior tongue-tie, a variant which is detected based on the “feel” of the sub-lingual space. Drawing on ethnographic research with clinicians in England, we clarify the professional and personal commitments involved in the controversy. Our analysis is informed by Douglas’ theory of cultural representations (grid-group theory), in which ideas of what is natural and unnatural constitute central metaphors.

In this article we focus on an anatomical condition of infancy that has become something of a lightning rod for contending ideas about mothers, babies, and medicine. Ankyloglossia (infant tongue-tie) is a congenital anomaly of the lingual frenulum that can restrict movement of the tongue, and make it difficult for children to latch onto the breast. It has long been treated by frenotomy, a surgical intervention to sever the lingual frenulum (Douglas Citation2018; Francis et al. Citation2015).Footnote1 Tongue-tie as a diagnosis and frenotomy as a procedure have gone in and out of fashion for centuries. Both Aristotle and Galen recorded tongue-tie as causing problems in some infants but also noted that frenotomy had uncertain outcomes (Obladen Citation2010). Like tonsillectomy and non-therapeutic circumcision (Dwyer-Hemmings Citation2020; Grob Citation2007; Waldeck Citation2003), frenotomy has drawn criticism on ethical grounds, with practitioners subscribing to a more conservative model of care arguing it is unnecessary, while those who are more interventionist defend it.

While any surgical intervention in childhood is cause for concern, this is all the more so when there are spikes in the frequency of procedures. In recent years there has been a marked increase in tongue-tie in many countries. Diagnoses of ankyloglossia appear to have risen sharply since 2000, with the frequency of frenotomy procedures more than doubling in the US and Canada (Joseph et al. Citation2016; Walsh et al. Citation2017; Wei et al. Citation2020). In Australia, the frenotomy rate rose from 1.22 to 6.35 per 1000 live births between 1997 and 2012 (Kapoor et al. Citation2018). Figures for England are harder to obtain, but NHS data suggest a rise from 3,671 frenotomies in 2010–11 to 5,487 frenotomies in 2016–17 (Hospital Episode Statistics).Footnote2 Most frenotomies in England are performed by lactation professionals in private practice, however, and on these no data are available.

Official UK guidelines represent frenotomy as a relatively safe procedure and recommend it if (a) tongue-tie is diagnosed and (b) breastfeeding problems have not been resolved through skilled breastfeeding support (Butenko et al. Citation2019; NICE Citation2005). But risks associated with surgery to sever the frenulum include oral aversion, respiratory events, bleeding, pain, scarring, and weight loss; as well as delay in diagnosis of alternative conditions that might cause feeding difficulties (Hale et al. Citation2019; Solis-Pazmino et al. Citation2020).

Adding to the confusion, there is disagreement on how tongue-tie should be classified, with no clinical consensus on assessment methodology (Caloway et al. Citation2019; Jin et al. Citation2018; Lisonek et al. Citation2017). In addition to the “anterior” tongue-tie that medical professionals have long recognised, there is a relatively new category of “posterior tongue-tie” (PTT), which cannot be verified visually – diagnosis depends on the clinician feeling the space under the child’s tongue. Posterior tongue-tie (PTT) was first described in an American Academy of Pediatrics newsletter (Coryllos et al. Citation2004). It is controversial partly because it can only be felt rather than seen, and partly because it is treated with a deep incision to the sub-lingual space, after which the tissue is often said to re-attach, requiring repeated interventions to rectify (Douglas Citation2018). In a recent opinion piece, three surgeons in the UK argued that diagnosis of PTT is driven by a “lucrative private industry” (Fraser et al. Citation2020). Impassioned arguments about PTT, and tongue-tie more generally, have taken place on social media among parents, professionals, and the broader public (e.g. Ray et al. Citation2019).

Tongue-tie has provoked controversy because it pits varieties of medicine that emphasize surgical intervention against those that emphasize care and support, and because it raises questions about the basis of clinicians’ authority to diagnose (by sight or palpation). Frenotomy also raises a contentious bioethical question regarding the grounds on which it is justified to inflict pain on an infant. How much confidence should we have in the benefits of a procedure in order to justify both the immediate pain of surgery and the risks associated with it? In the case of tongue-tie, the risk-benefit calculation is fraught, both because of the absence of consensus regarding diagnosis and because the purported benefits – the potential for improved likelihood of a satisfactory latch in breastfeeding, alleviation of maternal breast pain, a decreased likelihood of speech defects in later life, and “being able to lick an ice cream” – require detailed, long-term follow-up of a kind that medical research has yet to offer.

An ethnographic approach to tongue-tie

In this article we consider the professional and personal commitments related to major contending positions in the tongue-tie controversy. In order to do this, we immersed ourselves in the world of the clinicians who participate in it. Sixty healthcare practitioners were identified using judgment and snowball sampling, all of whom had experience diagnosing or treating ankyloglossia. Initial contacts were practitioners from the Association of Tongue-tie Practitioners (ATP), which represents tongue-tie practitioners from the NHS and the independent sector in the UK. The experience of one of the present authors (ML) as an osteopath practicing in London helped in rapport-building. Interviews with 21 healthcare professionals were conducted by the first author, 5 in person and 16 remotely (over Skype or FaceTime) for a duration of 30–80 minutes. Most respondents were based in England, with a geographical spread across the southern counties. In addition, two health professionals in Australia and one in the US (identified through their publications on the subject of tongue-tie and breastfeeding) were invited to participate in order to provide comparative perspectives. All were encouraged to reflect both on their own practice and on that of other health professionals. Given the controversial nature of the subject matter and the serious implications for professional reputations (e.g. the potential for allegations of malpractice), participants were often more forthcoming regarding what others did than what they themselves did. We have anonymized all but one participant who expressed a strong desire to be identified. In the following text, pseudonyms are indicated by quotation marks at first mention.

Interviews were supplemented by participation in professional workshops (two tongue-tie study days for midwives, breastfeeding counselors, health visitors and lactation consultants, and at a tongue-tie study weekend for osteopaths) and in a surgical setting – a pediatric ENT surgeon was observed performing four frenotomies on infants in a private hospital in London. We also observed public Facebook forums where parents and professionals interacted. In this article our reference to social media is limited to what participants told us about their own experiences on Facebook. Interviews and fieldwork were carried out between February and July 2018.Footnote3

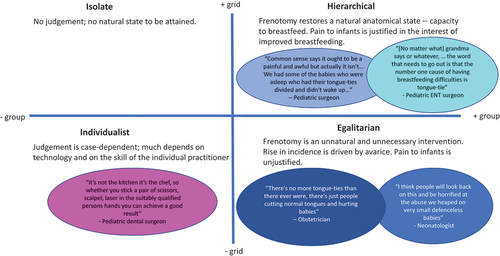

Our analysis is informed by Mary Douglas’ theory of cultural representations – also known as grid-group theory or the theory of cultural bias. This theory is part of Douglas’ later work, which remains less well known than her earlier writings (especially Purity and Danger Citation1970[1966]). Beginning with Natural Symbols Citation1996(1970) Douglas made important contributions to theories of conflict. Grid-group theory, which was further developed by Douglas’ students (notably Thompson et al. Citation1990), is distinctive in that it does not presume to classify positions on a given issue in a binary way – for example lumping them as “conservative” versus “liberal”– or even to assort them along a single continuum, such as Kleinman’s “softer” and “harder” professions (Kleinman Citation1995). Instead, it classifies ideological positions according to their location within a two-dimensional space characterized by degree of subscription to the ideal of authority (a rule-bound or grid framework) and the ideal of community (group membership). This framework is commonly represented by a two-by-two grid, the quadrants of which are conventionally described as hierarchical (high grid, high group), egalitarian (low grid, high group), individualist (low grid, low group), and isolate (high grid, low group) (see Thompson et al. Citation1990).

Grid-group theory has been applied to conflicts over climate change (e.g. Verweij et al. Citation2006), to public policy in the UK, and to competing narratives in global health policy (Ney Citation2012; see 6 and Richards Citation2017 for review). To our knowledge it has not so far been applied specifically to medical practice. Clinical medicine, however, provides many instances in which the universe of opinions is not so much polarized (suggesting two clearly opposed positions) as characterized by thorny, convoluted or messy disagreements, in which health conditions and treatments are conceived in multiple, incommensurable ways.

A frenotomy observed

“It is just a bit of fibrous tissue,” the ENT surgeon told the mother. The baby was swaddled in a blanket by a nurse and put on a small operating table. The surgeon was wearing surgical headlights and confidently put her fingers under the baby’s tongue and lifted it to show the mother the tongue-tie. The baby struggled, and its face went bright red, but was quickly soothed with sucrose drops. With a small pair of round-ended scissors, the surgeon quickly and skillfully cut once, twice, and then turned the scissors to stretch the wound. It sounded like cutting through leather or felt. The baby gave a high-pitched squeal but was quickly muzzled by gauze to stop the bleeding. Within seconds the child was asleep in its mother’s arms.

“See, it didn’t hurt at all,” the surgeon said to the mother, and off they went to the recovery room.

Left on the table were the pair of scissors and the bloody gauze, which the nurse quickly discarded.

The procedure described here occurred at a private hospital in London in March 2018. The encounter between surgeon, mother and baby constitutes one small – albeit decisive – part of the problematics involved in infant tongue-tie and frenotomy. It provides a window onto the stress and discomfort involved for patients and carers, as well as risks of complications such as oral aversion (feeding refusal), bleeding, and scarring.

Focusing on the surgical event in isolation, however, may be misleading: The procedure is preceded and followed by other important encounters, including diagnosis and follow-up, that bring patients into contact with health professionals with various and sometimes overlapping remits. The positions these professionals take on frenotomy relate partly to official remits on who can “suspect,” diagnose, and treat tongue-tie. An important distinction exists between those professionals who carry out frenotomies and those who do not – dividers versus non-dividers (see ).

Table 1. Health professions involved in diagnosis of ankyloglossia affecting breastfeeding and its treatment according to professional consensus statements

To get a feel for the controversy it is necessary to hear the voices of the participants, and we therefore devote much of the following text to testimony from our interviews. Because it is an area where feelings run especially high, we begin with the rising incidence of tongue-tie, and of posterior tongue tie (PTT) in particular.

A tsunami of tongue-ties

Common to all the people we interviewed was a feeling that diagnosis of tongue-ties was rising fast. The diagnosis, one participant said, seemed like it had “taken a life of its own” on account of demand for intervention from parents. Surgeon Mervyn Griffiths, who had taught many others to carry out frenotomy, saw himself and his colleagues as confronting “a tsunami of tongue-ties.” This was of special concern given the simultaneous rise in the diagnosis of posterior tongue-tie. Whereas there was broad consensus regarding the existence of anterior tongue-tie (which can be easily verified by visual and functional examination), posterior tongue-tie was a matter of heated debate among participants, with some endorsing the diagnosis, others expressing doubt and uncertainty, and yet others outright rejecting its existence as a clinical finding. In the view of one midwife and IBCLC,Footnote4 “Liesel”:

My worry is, what about the ones that aren’t a tongue-tie? They’re posterior and they’re normal and we are digging deeper and going further back. They’re getting older when being diagnosed by private people. Are we really sure we are not causing any side-effects? What about the salivary glands? What about the breast refusal?

This position was countered by others who emphasized the relief women experienced after the procedure. As another midwife and IBCLC, “Victoria,” put it:

You’d have to look at some of the people who are actually questioning it, saying, “Does it need treating?” Where are they coming from? Have they seen a lot of mums who’ve been really struggling and mums who’ve got babies who are really significantly tied, and when you release it, they go “Oh, that is so different!”? That’s more than a placebo effect.

While PTT is without doubt the most controversial diagnosis, there was substantial variation in opinion about the appropriateness of frenotomy to resolve other kinds of tongue-tie as well. This begs the question: what demographic, professional, or ideological commitments are involved in judgments over frenotomy and tongue-tie?

Divided professions?

We noted some suggestive patterns of variation in opinions regarding tongue-tie according to the gender and age of participants in our study, but the number of professionals we interviewed was too small for us to confidently establish correlations, and the patterns we observed were largely confounded by profession. Three physicians who were themselves women were generally critical of lactation professionals (the great majority of whom are women) who diagnosed and cut tongue-ties. One of the two surgeons interviewed, Mr. Mervyn Griffiths was very supportive of lactation professionals learning to divide tongue-ties, as he viewed them as specialists in everything related to breastfeeding. The other, pediatric ENT surgeon “Mrs Armstrong,” while also supportive of tongue-tie division, reported a bias against the procedure among male surgeon colleagues, which she attributed to them not having experienced, as she had herself, the pain of breastfeeding a baby with a tight frenulum.

The clearest divide in opinions was between certain physicians who were critical of the position of midwives and lactation professionals, and midwives and lactation professionals, who argued that physicians were “out of touch.” This may reflect variation in personal experience. Most lactation professionals, like Mrs Armstrong, had themselves breastfed tongue-tied babies. In the view of some doctors, however, lactation professionals and midwives had “simplistic” views, and possessed “quasi-knowledge” in contrast to the “real knowledge” of physicians. “Kathryn,” a neonatologist, noted that while the indications for diagnosis of tongue tie were diverse, lactation professionals tended to err on the side of diagnosing.

The checklist of signs that a baby’s got a tongue-tie include being miserable, losing weight … Hang on, it could be anything! They [lactation professionals] don’t have the knowledge, so when you say to them, “Lots of conditions look like that” – they wouldn’t know that, so they wouldn’t even refer a baby back, because many of them aren’t midwives either, and [even] midwives know very little about baby physiology.

Differences of opinion on this issue had eroded trust between some pediatricians and lactation professionals. Again, according to neonatologist Kathryn:

It’s distorted breastfeeding support and the image of breastfeeding supporters in the eyes of pediatricians and the public … So now if I ask someone to see a breastfeeding support worker or a lactation professional, I don’t know if they’re just going to come back to me with their tongue-tie cut without having provided other support for breastfeeding.

As Kleinman (Citation1995) observed, “hard” professions (interventionists such as surgeons) are accorded more prestige and earn higher salaries than soft professions (those concerned with behavioral support) and this may set up biases in interprofessional relations. All of the lactation professionals we interviewed felt that performing frenotomies was a natural progression from their work in supporting breastfeeding. Taking ownership of the diagnosis and treatment of tongue-tie, one IBCLC and midwife suggested, offered lactation professionals more power in the “inter-professional game,” in effect making them “harder” as a profession. As we explore below, this had implications for financial remuneration, especially for those practicing in the private sector. Another midwife and IBCLC reflected that the pressure to add surgery to their skillset had led them to intervene more than was necessary, and expressed unease at the manner in which diagnoses were being issued, especially with regard to PTT.

I am absolutely convinced I cut way more than I needed to when I first started three years ago because I was learning, because I was time-pressured, because it was what women expected – because you cut it and then you ring them a week later and they say things are a lot better … I’m not convinced they are real results. I think it is the most incredible placebo and I think that what we’re now doing is cutting tons, where they [mothers] are being told it’s a posterior tongue-tie …

The fact that opinions were divided not only between professions (e.g. physicians versus midwives) but within professions (e.g. among midwives and IBCLCs), however, suggests that the controversy goes deeper than simply a contest between professions, or between hard and soft varieties of medicine. To explore these patterns further we draw below on the idea of what is “natural” versus “unnatural,” which is central to grid-group theory.

Grid-group theory and the un/naturalness of frenotomy

The idea of recuperating a natural state (of oral anatomy, or of a way of feeding a baby) was fundamental to the position of many professionals – both those who were opposed to surgery as the primary way of resolving tongue-tie and those who defended it. For some, judgments about the naturalness of the end state served to justify the “unnatural” act of cutting of the frenulum. For others, natural variation among children was being medicalized, and an unnecessary procedure was being promoted against the best interests of children and parents. These judgments about Nature constituted a clue that what was at stake was not only a judgment about anatomy, but also a value position. In writing on grid-group theory, ideas of Nature constitute a sort of Ur-metaphor (Thompson et al. Citation1990).

Below we analyze the positions that participants articulated using the categories of grid-group theory – namely, hierarchical, egalitarian, and individualist – as a heuristic device (see ). Each of these categories corresponds to a distinct moral position. (The fourth category of “isolates” – sometimes referred to as ‘fatalist’ (Thompson et al. Citation1990) – does not imply an active moral position, and is not represented here.) After describing each of these we also consider boundary cases that do not fit neatly in any of the canonical grid-group categories.

Cutting to save the breastfeeding relationship: hierarchical views

A hierarchical worldview tends to extol authoritative or expert knowledge. In the case of tongue-tie this implies emphasis on the reality of the condition as a barrier to successful breastfeeding, and support for the utility of surgery to “save the breastfeeding relationship.” From this point of view, the risks associated with frenotomy were less pressing than the risk of a baby not breastfeeding, and surgery would address the root cause of the problem. As pediatric ENT surgeon Mrs Armstrong said:

The first thing to look for in a baby that is struggling to breastfeed is if they have got tongue-tie. [No matter what] grandma says or whatever, … the word that needs to go out is the Number-One cause of having breastfeeding difficulties is tongue-tie … The baby has the problem, not the mum.

Several tongue-tie dividers said that, according to mothers’ reports, the baby’s latch was much deeper and less painful after frenotomy, meaning breastfeeding could continue. (This view was particularly common among lactation professionals who were also tongue-tie dividers.) For them, frenotomy was a minor procedure, and relatively safe. While recognizing the controversy over the surgery, they emphasized the high level of demand for the procedure among mothers, and the improvements they saw after the surgery. From this point of view, frenotomy restored a natural state – an “untied” tongue – after which the baby was freed to feed in a natural way. The pain involved in the procedure was downplayed, and the benefits emphasized. “I don’t believe that it does as much harm to do it, as it would to not breastfeed,” said one of the eldest of the lactation professionals, a woman who had trained in midwifery in the 1980s.

Unnatural procedures and corrupt practices: egalitarian views

For others, by contrast, frenotomy was cast as an unnatural intervention, posing substantial hazards for infants. This corresponded to what in grid-group theory is referred to as an egalitarian position. Neonatologist Kathryn emphasized the pain involved, especially in the case of PTT. “Even if you’re going to argue that the frenulum didn’t have a nerve supply and wasn’t painful,” she said, “that wouldn’t apply to the posterior tongue-tie, where they really go very deep under the tongue.” “Iris,” an obstetrician, extended the argument to tongue-ties more generally: “In the wild, nobody was cutting tongue-ties, so the whole idea of snipping a baby’s tongue … it’s very painful for these babies, it’s about as far from natural as you could possibly get.” These participants emphasized the pain caused to infants by a procedure that might be unwarranted.

Those who emphasized infant pain and over-diagnosis also tended to note the financial incentives to recommend and carry out the surgery, which they saw as a driver of the rising incidence of tongue-tie, whether in private practice or within the NHS. “Sarah,” a midwife and IBCLC, reported, “I have seen quite a few practitioners who are out there exploiting women and telling them their babies need clipping, when actually what they need is really skilled time from somebody who knows about breastfeeding.” Some saw a financial incentive for hospitals to provide surgeon-led tongue-tie services, rather than midwife-led services, because they could charge the commissioners more. Surgeon-led tongue-tie clinics in the NHS, they suggested, were motivated more by the imperative of remedying hospitals’ budget deficits than by clinical need. “If you can get a 20-minute appointment, get one through at £200 at a time, that can help you with your deficit, can’t it?” said “Tonia,” a former Health Visitor/IBCLC and a tongue-tie practitioner who works in private practice.

The right tool for the job: individualist views

A third position on frenotomy is represented by “Peter,” a pediatric dental surgeon who released tongue-ties and lip-ties with laser. Peter noted the superiority of his “high-tech” approach over scissor frenotomies and emphasized the degree of control it provided over the surgery.

I’ve now done enough to know that my level of treatment with a laser is better because I can actually see everything I’m doing. There is generally a bloodless field. I’ve got magnification and proper lighting.

From Peter’s point of view, the main concerns were the skills of the surgeons and the tools at their disposal. He lamented the way the procedure was carried out, especially by midwives:

The stories we get where it’s the midwife on the kitchen table or even on the bedroom floor, with naked eyes, not seeing properly what they’re doing! More than half my caseload is repeats of the scissor jobs.

While he was dismissive of some midwives, Peter recognized that he was just one link in a chain of professionals involved in managing tongue-ties, and he emphasized the “teamwork” necessary for successful treatment. Among the members of this team he counted not only professionals (including lactation consultants and osteopaths) but also families. He asked parents to carry out “after-care” on their babies, which included stretching their children’s wounds several times a day after the procedure.Footnote5 The fact that parents were willing to accept this arrangement is indicative of the level of demand for the procedure. Demand from parents was one factor that has contributed to the professionalization of tongue-tie practice in recent years, a theme we explore below.

Boundary cases, and the rise of tongue tie practitioners as a profession

In 2012, the Association of Tongue-tie Practitioners (ATP) was established in the UK to provide information, share up-to-date research, and offer support to those managing tongue-ties.Footnote6 In 2017 it had approximately 200 members. At the time of our fieldwork in 2018, frenotomy was an unregulated practice, and the ATP aimed to provide assurance for parents, doctors, and the public that their members were adequately trained and insured. One ATP member reported that there was a need to combat the criticism and suspicion leveled at tongue-tie practitioners, particularly from pediatricians who were concerned about the number of procedures carried out in the private sector (Templeton and Gillespie et al. Citation2016). The ATP deliberately sought to present itself as neither interventionist nor denialist, and as such the institution straddles the divide between what we have described as hierarchical and egalitarian positions.

Liesel, who served as a hospital infant feeding lead, exemplified this boundary position. Liesel had been “losing sleep” over the high frenotomy rates in her hospital, and was concerned that too many children were being operated upon unnecessarily. As an infant feeding lead, she had oversight of an entire pipeline of children and their responses to treatment. She streamlined the service by having six infant feeding midwives using the same diagnostic procedure and criteria for treatment, but only two midwives performing the procedure. This reduced the frenotomy rate in her hospital considerably without affecting breastfeeding rates. It confirmed her belief that tongue-ties were over-diagnosed. In her opinion, many competent lactation consultants had lost confidence in their “soft” skills, and were diagnosing children with tongue-tie as a precaution against criticism from colleagues in the private sector. “If they plant the seed that it might be [tongue-tie],” Liesel said,

they’re covering their own backs, because some private practitioner is going to come along in a week’s time and say “That’s a tongue-tie” and “Why wasn’t it diagnosed?” and “You saw a lactation consultant – they were obviously a bit crap.” You see it all the time on Facebook.

“Emily,” who had been a Health Visitor in the NHS before becoming an IBCLC in 2005 and training to be a tongue-tie practitioner, was another boundary case. While she identified as a tongue-tie practitioner, she was also concerned that tongue-tie had “taken over” breastfeeding support, and recognized that in infant feeding there was “a whole host of [parental] anxieties, that are also part of that issue.” In her clinical practice she would first refer clients experiencing breastfeeding problems to an osteopath for “bodywork” (the term used for manual therapy that aims to release tension in an infant’s body and thereby improve the ability to latch). If the problems were not resolved after a couple of sessions of osteopathy, she would perform a frenotomy.

Both Liesel and Emily shared some of the concerns of “egalitarians” about the financial incentives to carry out frenotomy, while also taking seriously the challenge tongue-tie could pose to breastfeeding and the demand among mothers to have their children treated.

Authority, community, and visibility

Alongside the themes of authority and community – which the grid-group theory orients us toward – another theme that emerged clearly from the discourse around tongue-tie is visibility and invisibility. Questions of what is visible or invisible in relation to tongue-tie operate at three levels: first, the literal availability of tongue-tie to visual inspection; second, the variability in the kinds of patients whom health professionals see and the circumstances in which they see them; and finally, the way tongue-tie and frenotomy are represented in statistics, in the medical literature, and in other forums including social media.

The availability of tongue-tie to visual inspection was something stressed by the dentist, Peter, who emphasized the difference that “magnification and proper lighting” made to his practice, compared to the midwife “with naked eyes.” This is clearly relevant to the controversy over PTT, in which the means of diagnosis is palpation rather than visual inspection. It also relates to historically deeper conflicts between the authority of physicians based on the purportedly objective scientific gaze and that of folk healers and carers whose authority rests upon cumulative experience (Davis-Floyd and Sargent Citation1997).

Second, professionals are privy to different aspects of their patients’ experience depending on the interval in the patients’ journey at which they see them. The clearest illustration of this dynamic comes from the testimony of infant feeding leads, who have an unusual vantage point on their patients, given their oversight of a whole team of midwives and associated health professionals. Liesel’s perspective was shared by “Sylvia,” an infant feeding lead who discovered that by streamlining “clinical pathways” and getting the ENT surgeon in the hospital on board by referring babies older than 12 weeks to them, she could decrease the frenotomy rate considerably.Footnote7 She described her approach as follows:

… I get referrals to say, “This mum had a tongue-tied baby before, she had to wait three weeks and she’s really anxious” and I’ll see them as early as I can, or speak to them and say, “This is how it works, this is how the waiting list is, this is what we’re going to do,” sort of step-by-step and they find that really reassuring. I suppose it’s a kind of a holding, really a psychological holding, isn’t it?

This combination of “psychological holding” with clinical practice marries approaches that are more commonly associated with different branches of medicine – midwifery and surgery. Farmer (Citation1999, 6) has written of the “visual-field defects” and “selective blindness” of medicine and anthropology. By analogy, each professional specialty has its own spotlights, areas of soft focus, and blind-spots. Since tongue-tie is a fundamentally relational problem, professions focused on one or another of the mother-baby dyad may be inherently prone to bias in one direction or another.

The third way in which visibility enters into the problematics of tongue-tie is in terms of its representation in statistics, in the medical literature, and social media. Despite the explosion of research and publications on tongue-tie in recent years, statistics on basic matters such as the numbers of practitioners operating, and the number of surgeries carried out in specific jurisdictions – especially in the private sector – are hard to come by. The dearth of reliable information has provided fertile ground for speculation and for the projection of broader anxieties about threats to children’s health and well-being, exemplified for example by discourse on the internet in which parents and others represent tongue-tie as a threat to their children’s life chances, quite independent of their prospects of breastfeeding (Ray et al. Citation2019).

England as exemplar or anomaly?

While some of the dynamics we have described in this article may map onto controversies over tongue-tie in other parts of the world, other aspects likely reflect conditions peculiar to the UK, or to England in particular. The UK has the lowest lactation rate after 12 months in the world: Although 81% of women initiate breastfeeding, only 23% continue to exclusively breastfeed to 6 weeks, with many citing painful nipples, inability of babies to latch, or low milk supply as reasons for stopping (McAndrew et al. Citation2012; Victora et al. Citation2016). At the same time, public messaging of “breast is best” – in a culture that fails to support breastfeeding adequately (Brown Citation2016) – may dispose mothers to seek professional help or to shift responsibility for the problem onto infants. Breastfeeding in England is therefore increasingly medicalized and breastfeeding support increasingly professionalized. Infant feeding has become the responsibility of lactation consultants, who are often also midwives or Health Visitors. Since some midwives have acquired the surgical skills to treat tongue-tie, old animosities between midwives and surgeons appears to have re-surfaced (Obladen Citation2010).

In addition to these historical legacies, other aspects of the professional landscape merit consideration, including recent reforms to the NHS. The UK Health and Social Care Act of 2012, which decentralized administration of medical services and established a new tier of Clinical Commissioning Groups, increased pressure on NHS providers to compete not only with each other but also with private practitioners who can easily be accessed by phone or through social media. In the wake of these reforms, many midwives left the NHS or began to supplement their income by offering services privately while still working for the government system. Some justified this move by reference to the moral imperative of helping babies to breastfeed. As one midwife and IBCLC said:

I decided I would go private to be able to provide women with an option. It’s not ideal because I think it should be available on the NHS, but on the other hand if people paying to have it done meant that a baby would still be breastfeeding, then I had to concede that that was the only way I could help that happen.

In 2014, Luciana Berger, the then Labor Member of Parliament for Liverpool Wavertree and Shadow Minister for Public Health, took up the case of “missed” diagnoses, long waiting lists and lack of tongue-tie services leading to women having to give up breastfeeding early. “The length of the waits is forcing them [parents] to go private and pay for an expensive operation,” Berger noted. “The government must tackle these delays and ensure that the procedure is available for all on the NHS.” (Boffey Citation2014).Footnote8

In summary, the English setting in which the controversies we describe have played out is one in which mothers face considerable pressure to initiate breastfeeding but also great obstacles to sustaining it. When they turn to professionals for advice, they are likely to encounter a diversity of views but also (especially from private practitioners) a chorus of concern about tongue-tie as a potential barrier to breastfeeding, and about frenotomy as a way of resolving it. Finally, given ongoing conflicts within the NHS, the competition between the NHS and the independent sector, and the political capital attached to waiting lists, the issues of tongue-tie and frenotomy have come to carry a heavy load of ideological baggage.

Conclusion

This study provides the first in-depth and ethnographic account of the opinions of healthcare professionals concerning tongue-tie and frenotomy. It is also, to the best of our knowledge, the first to apply grid-group theory to a controversy in clinical medicine. We do not pretend that our sample is statistically representative of healthcare professionals in England – indeed, the snowball sampling methodology we used meant that some were selected precisely by virtue of their strong opinions. However, many of our participants were leading (and therefore sought-after) representatives of the tongue-tie dividing profession, with a great deal of clinical experience between them.

The views that participants held were diverse, and represented multiple contending takes on tongue-tie and the extent to which it is an impediment to successful breastfeeding. While the extreme case of PTT has amplified the controversy, real disagreements persist over tongue-tie more generally. Despite a broad distinction between the views of physicians who tended to be more conservative and lactation professionals who tended to be more liberal in diagnosis, participants were not cleanly divided into two camps. Our interviews and observations allowed us to go beyond acknowledgment of a professional dispute, to explore the range of moral positions in the controversy.

The heuristic device of grid-group theory proved useful in helping us to identify distinctive bioethical positions related to the participants’ takes on contentious issues of risk and benefit in a situation in which knowledge was partial and contested. These major positions, which we describe as hierarchical and egalitarian, cross-cut professional identities. A third position, the individualist, although represented by only one case, illustrates another distinctive take on the issues. Each of the major positions contains elements of the truth: Tongue-tie can be an impediment to breastfeeding and frenotomy can help resolve it. At the same time, however, medical professionals may overstep their authority and diagnose or operate when it is not warranted; financial and reputational conflicts of interest are at play here. Which aspect of this complex reality one chooses to prioritize is indicative of the cultural differences that crosscut medical professions.

We also identified a number of boundary cases which did not fit neatly in the canonical categories of grid-group theory. These boundary cases were especially common among those who identified closely with the recently established Association of Tongue-Tie Practitioners, and among infant feeding leads who had an unusually broad vantage point on the tongue-tie landscape. Who sees whom is a fundamental question to ask in relation to medicine, and considering it led us to think hard about the distinction between seeing and feeling as modalities of diagnosis and – taking the term feeling in a wider sense (as emotional valence or intuition) – the ways value judgments necessarily enter into medical practice – not least when the nature of the problem or the intervention in question involves short-term suffering for uncertain, long-term gain. To the extent that these concerns are common to other medical debates – and we have no reason to believe they are unique to tongue-tie and frenotomy – the approach we have taken here may hold promise for exploring other bioethically difficult and convoluted, value-driven subjects in medicine.

Acknowledgement

We are grateful to our participants and to the Association of Tongue-tie Practitioners (ATP). We would like to extend special thanks to Renee Kam and Felicity Bertin, who helped us navigate the medical literature on tongue-tie. In the course of working on this subject we benefited from conversations with Cecilia Tomori, Ben Kasstan and Bob Simpson, and from participation in the Mary Douglas Seminars at UCL in the years 2016-2019. The article was further improved on the basis of feedback from Kay Gilliland Stevenson and three anonymous reviewers. Approval for this study was granted by the Ethics Committee of the Anthropology Department at University College London.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Maria Larrain

Maria Larrain is a practicing osteopath in London. She is currently studying the comparative maternal experience of tongue-tie and breastfeeding in England in a public and private setting as her doctoral research with the Department of Anthropology, University College London.

Edward G.J. Stevenson

Edward G.J. (Jed) Stevenson is Assistant Professor of Global Health Anthropology at Durham University. His research focuses on conflict and cooperation over access to vital resources. ORCID ID orcid.org/0000–0003-2018–8920

Notes

1. Note on terminology: In relation to medical literature, we use the term ankyloglossia and in relation to clinical practice we use tongue-tie. Although frenotomy, frenectomy, frenulotomy or frenuloplasty are used interchangeably in the literature to describe the division of the frenulum, we refer to the procedure as frenotomy.

2. The National Health Service (NHS) is Britain’s publicly funded healthcare system, established in 1948. The NHS is an umbrella for four largely independent systems operating in the four nations of the United Kingdom (England, Wales, Scotland, and Northern Ireland). In April 2013 led to far-reaching reforms to the service. The legislation established Clinical Commissioning Groups (CCGs) that oversee NHS Trusts and primary care services (England.NHS.UK, 2021). In this article, where we use the term NHS, we refer primarily to NHS England in its post-2013 incarnation.

3. We provided all participants with an information sheet and invited them to provide consent to participate. One of the participants declined to sign the consent form and was excluded on these grounds; data from another was removed from the corpus of transcripts at the participant’s request after the fieldwork was completed. All interviews were audio recorded and transcribed verbatim. We kept a methods diary and made reflective field notes to document the observational components of the study. NVIVO was used to code the transcripts and field notes, and a node diary was used to extract the sub-themes emerging from the analysis (Bazeley 2013). In the first instance, we used open coding, allowing for prominent themes to emerge. Subsequently we coded the interview transcripts using the grid-group typology as a guide, flagging quotations characteristic of particular positions in relation to risks versus benefits of frenotomy. The authors conferred throughout the research process (the second author was the academic supervisor of the MSc thesis on which the study was based).

4. An IBCLC is a lactation consultant who has passed the International Board Certified Lactation Consultant exam. The Lactation Consultant examination was established in 1985 with funding from La Leche League to certify the emerging profession of lactation consulting (IBCLE 2021). Lactation consultants who are also regulated healthcare professionals such as midwives or health visitors (registered nurses), are referred to as lactation professionals in this article. A tongue-tie practitioner (also sometimes called tongue-tie divider) is anyone who is qualified to perform a frenotomy.

5. The practice of stretching the fresh wound to avoid re-attachment of tissues is controversial. In our sample, only the dentist and one lactation professional recommended this practice to parents.

6. The health professionals who carry out frenotomy are formally regulated by their own individual regulatory bodies, such as the Nursing and Midwifery Council. The ATP maintains a website (tongue-tie.uk, 2018).

7. Similar results have been reported in New Zealand, where streamlining assessment and referral pathways reduced frenotomy rates without affecting breastfeeding rates (Dixon et al. 2018).

8. After our study was completed, in February 2019, regulations were imposed on private frenotomy practice, requiring all tongue-tie practitioners to register with the Care and Quality Commission.

References

- 6, Perri, & Paul Richards. 2017. Mary Douglas: Understanding Social Thought and Conflict. New York, Oxford: Berghahn Books.

- Adams, Stephen. 2018. Spina Bifida charity accuses midwives of ‘scaremongering’. Mail Online. https://www.dailymail.co.uk/health/article-5589989/Spina-bifida-charity-accuses-midwives-scaremongering.html

- BBC News. 2021. Babies ‘don’t need tongue-tie surgery to feed. https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/health-48934994

- Boffey, Daniel. 2014. Concern over delays to treatment of babies suffering from tongue-tie. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/society/2014/jul/12/tongue-tie-babies-delays-treatment-nhs-breastfeeding

- Brown, Amy. 2016. Breastfeeding Uncovered. London: Pinter & Martin Ltd.

- Butenko, Hannah, Vanessa Fung, & Sarahlouise White. 2019. Effectiveness of frenectomy for ankyloglossia correction in terms of breastfeeding and maternal outcomes: A critically appraised topic. Evidence-Based Communication Assessment and Intervention 13(1–2):32–50. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/17489539.2019.1598012

- Caloway, Christen, Cheryl J Hersh, Rebecca Baars, Sarah Sally, Gillian Diercks, & Christopher J Hartnick. 2019. Association of feeding evaluation with frenotomy rates in infants with breastfeeding difficulties. JAMA Otolaryngology–head & Neck Surgery. doi:https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaoto.2019.1696.

- Coryllos, E, C Watson Genna, & A Salloum. 2004. Congenital tongue-tie and its impact on breastfeeding. Breastfeeding: Best for mother and baby. American Academy of Pediatrics Summer:1–6

- Davis-Floyd, RR, & Carolyn F. Sargent. 1997. Childbirth and Authoritative Knowledge. Berkeley (Ca.): University of California Press.

- Dixon, Bronwyn, Juliet Gray, Nikki Elliot, Brett Shand, & Adrienne Lynn. 2018. A multifaceted programme to reduce the rate of tongue-tie release surgery in newborn infants: Observational study. International Journal of Pediatric Otorhinolaryngology 113:156–63. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijporl.2018.07.045

- Douglas, Mary. 1970. Purity and Danger. London and New York: Routledge.

- Douglas, Mary 1996 Natural symbols: Explorations in cosmology. London: Routledge.

- Douglas, Pamela. 2018. Tongues tied about tongue-tie - Griffith review. Griffith Review. https://griffithreview.com/articles/tongues-tied-about-tongue-tie/

- Dwyer-Hemmings, Louis. 2018. ‘A wicked operation’? Tonsillectomy in twentieth-century Britain. Medical History 62(2):217–41. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/mdh.2018.5.

- Farmer, Paul (Arzt). 1999. Infections and Inequalities. 1st ed. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Francis, D O., S Krishnaswami, & M McPheeters. 2015. Treatment of ankyloglossia and breastfeeding outcomes: A systematic review. Pediatrics 135(6):e1458–e1466. doi:https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2015-0658

- Fraser, Lyndsay, Stuart Benzie, & Jenny Montgomery. 2020. Posterior tongue tie: The internet phenomenon driving a lucrative private industry - The BMJ. The BMJ 26:371.

- Grob, G N. 2007. The rise and decline of tonsillectomy in twentieth-century America. Journal of the History of Medicine and Allied Sciences 62(4):383–421. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/jhmas/jrm003

- Hale, Matthew, Nikki Mills, Liza Edmonds, Patrick Dawes, Nigel Dickson, David Barker, & Benjamin J Wheeler. 2019. Complications following frenotomy for ankyloglossia: A 24‐month prospective New Zealand paediatric surveillance unit study. Journal of Paediatrics and Child Health 56(4):557–62. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/jpc.14682.

- Hall, D M B, & MJ Renfrew. 2005. Tongue-tie. Archives of Disease in Childhood 90(12):1211–15. doi:https://doi.org/10.1136/adc.2005.077065.

- Hogan, Monica, Carolyn Westcott, & Mervyn Griffiths. 2005. Randomized, controlled trial of division of tongue-tie in infants with feeding problems. Journal of Paediatrics and Child Health 41(5–6):246–50. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1440-1754.2005.00604.x

- “IBLCE”. 2021. IBLCE. https://iblce.org

- Jin, Ruilin R, Alastair Sutcliffe, Maximo Vento, Claudelle Miles, Javeed Travadi, Kumar Kishore, & KEIJI Suzuki et al. 2018. What does the world think of ankyloglossia?”. Acta Paediatrica 107(10):1733–38. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/apa.14242.

- Jones and Kestenberg 2020 Rebuttal to the statement from the Australian Dental Association (ADA) on ankyloglossia. https://www.enhancedentistry.com.au/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/Rebuttal-to-ADA-consensus-statement-on-ankyloglossia-June-2020.pdf

- Joseph, K S., B Kinniburgh, A Metcalfe, N Razaz, Y Sabr, & S Lisonkova 2016 Temporal trends in ankyloglossia and frenotomy in British Columbia, Canada, 2004-2013: A population-based study. CMAJ Open 4(1):E33–E40. doi:https://doi.org/10.9778/cmajo.20150063

- Kapoor, Vishal, Pamela S Douglas, Peter S Hill, Laurence J Walsh, & Marc Tennant 2018 Frenotomy for tongue-tie in Australian children, 2006-2016: An increasing problem. The Medical Journal of Australia 208(2):88–89. doi:https://doi.org/10.5694/mja17.00438.

- Kleinman, Arthur 1995 Writing at the Margin. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Lisonek, Michelle, Shiliang Liu, Susie Dzakpasu, Aideen M Moore, & K S Joseph 2017 Changes in the incidence and surgical treatment of ankyloglossia in Canada. Paediatrics & Child Health 22(7):382–86. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/pch/pxx112.

- McAndrew, F, J Thompson, L Fellows, A Large, M Speed, & MJ Renfrew 2012 Infant feeding survey - UK, 2010 - NHS digital. NHS Digital. https://digital.nhs.uk/data-and-information/publications/statistical/infant-feeding-survey/infant-feeding-survey-uk-2010

- Messner, Anna H, M Lauren Lalakea, Janelle Aby, James Macmahon, & Ellen Bair 2000 Ankyloglossia: Incidence and associated feeding difficulties. Archives of Otolaryngology–head & Neck Surgery 126(1):36–39. doi:https://doi.org/10.1001/archotol.126.1.36.

- Mills, Nikki, Donna T Geddes, Satya Amirapu, & S Ali Mirjalili 2020 Understanding the lingual frenulum: Histological structure, tissue composition, and implications for tongue tie surgery. International Journal of Otolaryngology 2020:1–12. doi:https://doi.org/10.1155/2020/1820978.

- Mills, Nikki, Seth M Pransky, Donna T Geddes, & Seyed Ali Mirjalili 2019 What is a tongue tie? Defining the anatomy of the in‐situ lingual frenulum. Clinical Anatomy 32(6):749–61. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/ca.23343.

- Ney, S 2012 Making sense of the global health crisis: Policy narratives, conflict, and global health governance. Journal of Health Politics, Policy and Law 37(2):253–95. doi:https://doi.org/10.1215/03616878-1538620

- NHS England 2017 Involving people in their own health and care: Statutory guidance for clinical commissioning groups and NHS England. https://www.england.nhs.uk/wp-content/uploads/2017/04/ppp-involving-people-health-care-guidance.pdf, accessed December, 2021.

- NICE “Overview | Division of Ankyloglossia (Tongue-Tie) for Breastfeeding | Guidance | NICE” 2005 Nice.Org.Uk. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ipg149

- O’-Shea, Joyce E, Jann P Foster, Colm PF O’-Donnell, Deirdre Breathnach, Susan E Jacobs, David A Todd, & Peter G Davis 2017 Frenotomy for tongue-tie in newborn infants. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.cd011065.pub2.

- Obladen, Michael 2010 Much ado about nothing: Two millenia of controversy on tongue-tie. Neonatology 97(2):83–89. doi:https://doi.org/10.1159/000235682

- Ray, Shagnik, Tai Kyung Hairston, Mark Giorgi, Anne R Links, Emily F Boss, & Jonathan Walsh 2019 Speaking in tongues: What parents really think about tongue-tie surgery for their infants. Clinical Pediatrics 59(3):236–44. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0009922819896583.

- Robertson, Judith H, & Ann M Thomson 2016 An exploration of the effects of clinical negligence litigation on the practice of midwives in England: A phenomenological study. Midwifery 33:55–63. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.midw.2015.10.005.

- Solis-Pazmino, Paola, Grace S Kim, Eddy Lincango-Naranjo, Larry Prokop, Oscar J Ponce, & Mai Thy Truong 2020 Major complications after tongue-tie release: A case report and systematic review. International Journal of Pediatric Otorhinolaryngology 138:110356. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijporl.2020.110356.

- Templeton, Sarah-Kate, & James Gillespie 2016 Doctors attack ‘needless’ baby tongue surgery. The Times. https://www.thetimes.co.uk/article/doctors-attack-needless-baby-tongue-surgery-sqpbp7gtg

- Thompson, John M. T, Richard J Ellis, & Aaron B Wildavsky 1990 Cultural Theory. Boulder, Colo: Westview Press.

- Verweij, Marco, Mary Douglas, Richard Ellis, Christoph Engel, Frank Hendriks, Susanne Lohmann, Steven Ney, Steve Rayner, & Michael Thompson 2006 Clumsy solutions for a complex world: The case of climate change. Public Administration 84(4):817–43. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-8159.2005.09566.x-i1

- Victora, Cesar G, Rajiv Bahl, Aluísio J D Barros, Giovanny V A França, Susan Horton, Julia Krasevec, Simon Murch, Mari Jeeva Sankar, Neff Walker, & Nigel C Rollins 2016 Breastfeeding in the 21st century: Epidemiology, mechanisms, and lifelong effect. The Lancet 387(10017):475–90. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(15)01024-7.

- Waldeck, Sarah E 2003 Social norm theory and male circumcision: Why parents circumcise. The American Journal of Bioethics 3(2):56–57. doi:https://doi.org/10.1162/152651603766436261.

- Walsh, Jonathan, Anne Links, Emily Boss, & David Tunkel 2017 Ankyloglossia and lingual frenotomy: National trends in inpatient diagnosis and management in the United States, 1997-2012. Otolaryngology-Head and Neck Surgery 156(4):735–40. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0194599817690135.

- Wei, Eric X, David Tunkel, Emily Boss, & Jonathan Walsh 2020 Ankyloglossia: Update on trends in diagnosis and management in the United States, 2012-2016. Otolaryngology–head and Neck Surgery:019459982092541. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/0194599820925415.