ABSTRACT

In Denmark, injunctions of “early” cancer diagnosis increasingly imply surveillance of small tissue changes, which may or may not develop into cancer. Based on fieldwork at diagnostic lung cancer clinics and with people in CT surveillance for tissue changes, I explore how detected tissue changes are ascribed meaning as signs of “nothing” or “something.” Inspired by Peircean semiotics, I suggest that the semiotic indeterminacy of tissue changes points to how diagnostic socialities both expand medical semiotics and enable this expansion. The article, thereby, contributes to understandings of signs as diagnostic infrastructures.

Throughout the twentieth century, public health interventions and population screening have increasingly naturalized attempts to push the timely limits of illness prevention by lowering risk thresholds and specifying yet smaller abnormalities. Today, one key arena for biomedicine is the detection and surveillance of “at-risk” states to control possible future disease. This has been termed a predictive healthcare complex (Andersen Citation2023). In the case of cancer, the detection and surveillance of possible pre-cancerous conditions has increasingly been cast as a form of cancer control (Cantor Citation2008; Löwy Citation2010). A prominent example concerns molecular and so-called personalized medicine, which has expanded the medical sign system and enhanced the temporal focus on “early detection” and “early diagnosis” (Keating and Cambrosio Citation2012; Manderson Citation2015). Novel developments include the application of non-hereditary genetics in experimental oncology and the continuous search for biomarkers to predict future disease development (Bogicevic et al. Citation2021; Arteaga Pérez Citation2021). Historian and biologist Ilana Löwy has pointed to a concurrent development in what she terms “morphological prediction” (Löwy Citation2010). Here, small changes in the form or structure of tissue are tied to an increased risk of cancer in the future. Notably, the practices of predictive morphology have been subject to minimal public debate in contrast to the similar practices of predictive genetics (Löwy Citation2010).

In this article, I explore diagnostic practices that detect, evaluate, and monitor morphological tissue changes as potential signs of lung cancer. Cancer is a leading cause of death worldwide, and lung cancer has been one of the most frequent types of cancer death for half a century. In technologically affluent settings, CT scanning is increasingly used as a tool to detect low stage cancer in order to enhance chances for survival. For instance, in Denmark, the use of CT scanning has increased tremendously during the past two decades; from 230,000 CT scans in 2003 to 850,000 CT scans in 2014 (Sundhedsstyrelsen [Danish Health Authority] Citation2015). The detection of tissue changes has seen a corresponding explosion; in the US, it has been assessed to have increased from 150,000 per year in 2003 to 1,500,000 per year in 2015 (Gould et al. Citation2015). In my fieldwork, chief clinicians suggested that the number of people in extended surveillance due to a detected tissue change was double the amount of diagnosed lung cancers. As anthropological research suggests, these practices of cancer control have extended the spatial and temporal scope of cancer, thereby enhancing its potentiality and reaching far into people’s bodies and everyday lives as well as into experiences and concerns of the present, future, and past (Frumer et al. Citation2021; Jain Citation2013; Offersen et al. Citation2018). As being directed toward a future that may or may not arrive, cancer may or may not develop. Diagnostic processes become increasingly speculative in nature as they are directed toward unknowable futures (Adams et al. Citation2009:247). Diagnostics, here, are directed less toward possible prevention in the strict sense, but more toward a vigilant anticipation in an attempt to prepare in advance. In a recent collection, Rikke Sand Andersen and Marie Louise Tørring (Citation2023) present contributions that point to how early diagnosis as a medical paradigm establishes anticipation as a new temporal reframing of cancer. On theoretical and empirical bases, the collection suggests that in anticipating that cancer may become part of the future, cancer as anticipation is always already part of the present through the steering of practices, embodied experiences, ethics, and expectations. As in this article, these developments are set in the relatively affluent Danish welfare state.

Denmark has a tax-based, publicly funded healthcare system. In the wake of the 2000s, political agendas to improve cancer detection and survival came into being in Denmark, England, and other Northern European and Anglo-Saxon countries. Through a focus on “timely action,” it afforded an, at the time, unprecedented restructuring of healthcare systems that expanded infrastructures of cancer control and surveillance. Illustrated with Denmark, this included designated cancer referral pathways with strict time-management (Pedersen and Obling Citation2020), national cancer screening programs (Kirkegaard et al. Citation2019), and messages of “do not delay” in cancer awareness campaigns (Offersen et al. Citation2018). Today, both laypeople and doctors are urged to promptly react to increasingly smaller changes or vague and common sensations, such as fatigue, changed bowel habits, pains, and coughing (Andersen Citation2017). As Offersen and colleagues argue, the often straightforward presentation of “alarm symptoms” and “do not delay” messages implies “an unintended illusion of certainty.” This obfuscates the complexities of everyday – and clinical, I add – considerations of potential cancer (Offersen et al. Citation2018).

Inspired by Andrew Lakoff’s characterization of “vigilance” as a new form of governmentality in global health security (Lakoff Citation2015), I see these shifts in cancer control as a form of vigilant biopolitics. Analyzing global responses to the H1N1 influenza pandemic in 2009, Lakoff distinguishes between two contemporary ways of approaching disease threats: first, an actuarial approach of cost-benefit, statistical risk management and, second, a precautionary approach based on sentinel devices. These sentinels provide “early warnings” as a measure to control potential future threats that cannot be prevented but only managed (Lakoff Citation2015:43–45). With this shift from risk management to vigilance, I suggest Danish healthcare governance as an exemplar of a vigilant biopolitics seeking to control cancer even before it has materialized. Specifically, a vigilant biopolitics transforms healthcare infrastructures to be sensitive toward these early and vague signs (Andersen Citation2023; Frumer Citation2023). Furthermore, as I suggest in this article, it creates an elusive pathway outside the main cancer pathways, where doctors are occupied by filtering out all sorts of “trifles” and determining them as “signs of nothing,” that is, not a sign of cancer. Thus, in this article, I document how contemporary cancer control infrastructures expand diagnostic time and medical semiotics indeterminately by plotting bodies on a path of not-becoming cancerous and by plotting diagnostic practices on a path of ruling out cancer. To explore this, I turn the analysis of diagnostic processes around and, instead of looking at what it takes to establish a diagnosis, I look at the work done to “rule out” cancer or to establish that “this is nothing.” I argue that the expanding medical semiotics, which is evident in cancer control in the predictive healthcare complex, makes this work of establishing “nothing” increasingly central in the everyday clinical setting. Thus, inspired by Peircean semiotics, I suggest that the semiotic indeterminacy of tissue changes is a key element in the doctors’ processes of distinguishing between “nothing” and “something.” I have condensed these signification processes analytically in two moves, where the doctors attempt to strengthen relations away from cancer: size and figuration, and time and stability. I will conclude by briefly considering how the signification of “nothing” reveals a vigilant biopolitics and how it affects anthropological understandings of diagnostics.

Approach and material: Semiotic pragmatism and fieldwork

Because I explore “tissue changes” as signs and the process of signification, I center on the diagnostic meaning-making practices of tissue changes in the clinical setting and their relation to cancer. Tissue changes are not cancer. However, they gain significance in their ability to point toward cancer anticipations: the possibility of ensuring “timely detection” of cancer. Yet, the diagnostic process of establishing a relation between tissue changes and cancer produces a myriad of signs. Here, the pulmonary doctors do not only “read” tissue changes; they also try to figure out what the tissue changes might be and what they may do to foretell and take action against future illness events.

All signs re-present and thus point to something not immediately present. The information they provide is not absolute or certain; it needs to be interpreted and set in relation. According to pragmatist philosopher Charles Sanders Peirce, the process of signification consists of a triad of object, sign, and interpretant. Simply put, Peirce defines a sign as anything that mediates between an object (that which is signified) and an interpretant (the response or effect produced). A sign is determined by an object (and in turn determines an interpretant) in the sense that it is linked and stands in a given relationship (Peirce et al. Citation1998:402). As Timmermans (Citation2017) argues, the focus on how meaning-making is a practical achievement within a dynamic flow of signs is key in understanding the semiotics of Peirce. A sign needs to be interpreted as a sign. Accordingly, the effect produced in this interpretation, the interpretant, may act as a new sign in a chain of signification. In this line of research, “knowing” is understood as “doing” and, therefore, my focus is directed to how meaning is done. Here, I am interested in the dynamic relations between object, sign, and interpretant, that is, in the ways that tissue changes come to mean through practices of differentiating and not differentiating. Various elements form part of the signification process, but the meaning of the specific tissue change detected on a CT image takes center stage.

The article is based on fieldwork that I carried out in the fall of 2015 and again in the period between the summer of 2018 and the spring of 2020. The fieldwork took place in Central Denmark Region at two hospital outpatient clinics for lung cancer diagnostics. A major part of my fieldwork consisted of observing consultations about tissue changes and daily clinical practice at the lung clinics, including CT conferences at the radiology departments. At the clinics, I gained a broad insight into daily practices and the context for the detection, negotiation, and surveillance of tissue changes. I joined in with daily tasks, especially consultations about tissue changes and the offer of surveillance. Additionally, I followed “tissue changes” through diagnostic practices, from CT scan to CT description, in professional guidelines, in public and professional online debates, at conferences, and not least in the homes and everyday lives of people in surveillance for tissue changes (Frumer et al. Citation2021). In some cases, I was able to follow a detected tissue change from the interpretation of the CT images through the consultations about tissue changes and until after the results of the first surveillance scan.

I conducted fieldwork in accordance with the codes of ethics by the American Anthropological Association. All participants received written and oral information about the project, including purpose, anonymity, voluntariness, and the possibility to withdraw at any time. I have tried to “listen differently,” as suggested by Lisa Stevenson (Citation2014), that is, not to filter out inconsistencies but to partake in the indeterminacy and uncertainty implied in practices of tissue changes. Both doctors and laypeople were frustrated about how to order the meaning and implications of tissue changes. Taking these frustrations seriously made me look deeper into the ambivalences and dissonances in the efforts to “control” cancer. With the aim to document the nuances and reflections embedded in everyday clinical practices, the inherent ambivalences in the distinction between “nothing” (ingenting) and “something” (noget), which is a distinction originating from the field, have become a key analytical framing in the article. To further the distinction between “nothing” and “something,” I will elaborate the analysis of tissue changes as phenomena below.

Tissue changes as diagnostic object

Small lung changes are ambiguous and shape-shifting: they might represent an embryonic cancer; they might be caused by a recent infection or perhaps a scar from a long gone infection. Often, there is no obvious reason to explain them. Sometimes, they are described as related to age and linked to exterior signifiers of old age like wrinkles and spots on the skin. Sometimes, the relation to smoking is enhanced and the damage to lung tissue that this causes. Through a lifetime, lungs are constantly exposed to small particles because of the inevitable embodied practice of breathing. Most of the times, the lungs cleanse themselves, but sometimes a particle is deposited, encysted, and left inside the lungs. Tissue changes below 10 mm are very common and hold only a small risk of cancer (around 1–3%). Furthermore, as CT images are moments of snapshots, a tissue change might have developed many years ago. In the time to come, it might stay as it is (“perhaps this is just how you look”), it might shrink or even disappear, or it might grow in size. Adding to this an element of various growth rates completes the shape-shifting aura of small lung changes – as is also the case with cancer.

Notably, tissue changes are outside the reach of bodily perception. They are not thought to produce “symptoms.” Yet, with a size below 10 mm, they are too small to be biopsied, as would have been the standard way of determining their pathological meaning. In other words, tissue changes cannot be articulated or rendered as bodily experiences, and they cannot materialize through a biopsy. They may only be seen. This embodied and biological indeterminacy, in its indeterminate relation to cancer, is what drives the CT surveillance of tissue changes and the diagnostic work around it. As theoretical physicist and feminist theorist Karen Barad describes it, a techno-phenomenon is not “a preexisting object of investigation with inherent practices,” but it is continuously constituted through concrete practices and materials in a specific historical and social setting (Barad Citation2007:217). In the case of tissue changes, I suggest that their qualities as objects are constituted through concrete semiotic work as well as through specific technologies of visualization that make increasingly smaller changes detectable in the setting of prioritizing “early diagnosis” as cancer control.

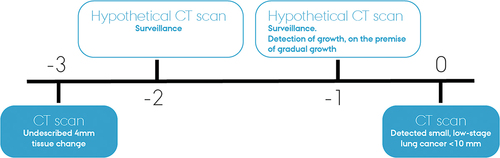

After a CT scan, the CT images are interpreted and described by a radiologist and then often discussed with a pulmonologist at a clinical conference. In a dimly lit room, with the black and white CT images taking center stage, the doctors would run through the individual patient cases. CT images are toned in black and white with organs appearing in tones of gray (see ). This representation is visually related to the level of absorption of X-rays: a higher absorption of X-rays is represented as more white areas and interpreted as denser tissue. For instance, air-filled cavities, like the lungs, appear as darker or black areas, whereas bone tissue shows as white. Even for an outsider like me, untrained in radiology, some entities are easy to distinguish from normal-looking lung tissue. In a long-time smoker’s lungs, the intense blackness of emphysema, a form of damaged lung tissue, stands in sharp contrast to the gray tones of normal-looking lung tissue. Increasingly easy to detect, but more difficult to interpret, tissue changes appear as white dots or light gray, diffuse shadows.

Figure 1. CT images of tissue changes (pulmonary nodules), encircled (Rubin et al. Citation2015).

The clinical conferences were scheduled to take no more than half an hour each, and they were conducted in a tightly woven time frame allowing for a couple of minutes for each case. Some patients needed referrals to other departments, some needed further investigations due to suspicion of lung cancer, some cases were closed right away, and others were recommended surveillance. Often, a case was introduced, discussed, and decided upon within 30 seconds.

In this process of making sense of a tissue change, the task for the team of pulmonary doctors became to decide whether a tissue change should be conceived as “something,” indicating a strong association to cancer, or as “nothing,” indicating very little likelihood of cancer. The significance of tissue changes appears on the backdrop of an absence of (clear-cut) cancer as interpreted from a specific set of CT images. With such a CT scan, the preliminary suspicion that guided the motivation for diagnostics has been cleared. Yet, the relation to cancer cannot be cut fully. Even though tissue changes will most likely not become cancer, it takes work for the clinicians to make it plausible that it is safe to consider a specific tissue change as “nothing.” In these cases, I suggest that the diagnostic work of the pulmonary doctors revolves around attempts to stabilize the interpretation of signs that strengthen relations directed away from cancer. These are relations that point toward a future where a tissue change has not become “something.”

Processes of signification

The shared process of signification, which is focused on deciding a way forward, starts at the clinical conference. Here, the doctors introduced new cases with the person’s name and age. The radiologist would then describe the key indications for the CT scan, as noted in the referral. Often, it stated symptoms like prolonged coughing and shortness of breath, or more general symptoms like tiredness. After specifying the detected tissue change, the doctors would focus on deciding the plan of action and, in the case of surveillance, the interval for CT scanning. Thus, the indication of symptoms acted as an entry point to the CT scan. However, if the initial sign suggested that this was not cancer, but “only” a detected tissue change, these symptoms could not stabilize a relation of “something.” Between radiologists and pulmonologists, these discussions often concluded with phrases like “surveillance not indicated. But make sure to note in the patient’s medical record that the tissue change cannot explain the symptoms.” In these exchanges, the indicated symptoms and the detected tissue change seemed unrelated. Therefore, as a sign, the CT-detected tissue change lacked an immediate object to signify, and the doctors could work toward annulling its value as a sign. In that process of interpreting the tissue change as “no-thing” – not a thing – the doctors especially worked with “size” and “time” as core signs in relation to cancer.

To analyze these signs, I find the Peircean description of a sign’s relation to its object meaningful. PeirceFootnote1 Peirce distinguishes between three main kinds of sign-object relations: icons, indexes, and symbols. Simply put, an icon has a direct resemblance with its object (like a picture of fire), whereas an index draws an association through a correlation in time and space for example by pointing (like the smoke coming up in the horizon pointing toward a fire). A symbol primarily anchors its meaning through convention without requiring any correlation in time or space between the sign and its object. Symbols can easily be removed from their context and associated with large sets of other symbolic relations (like the word “fire”). In the next sections, I describe these distinctions of sign-object relations in the case of tissue changes.

Size and figuration

The first pair of signs in the movement away from cancer concerns the measured size and figuration of the tissue change. Here, the quality and characterization of the object is at stake, and the CT image as a sign stands in an iconic relation to the actual existing tissue change: its object. The size measured on a CT image is understood to be like the size of the tissue change inside the body. The difference between the two are ignored or rather unnoticed, or what anthropologist Eduardo Kohn phrases as an “absence of attention to difference” when he clarifies what characterizes an iconic relation (Kohn Citation2013: 31). As an icon, the CT image does not, in this case, point toward similarities between entities that the doctors interpret to be different, instead it suggests – through them not noticing this difference – an indistinction between object (tissue change) and sign (size on CT image).

As stated in the diagnostic guidelines, size defines the risk of cancer as the number of surveillance visits is reduced with decreasing size. Most often, small size sets the ground for the doctors to believe a specific tissue change to be “nothing.” At CT conferences, smaller tissue changes could be described as “unspecific discrete changes” (diskrete forandringer) or “very uncharacteristic;” which meant that their cancer potential was negligible. Size refers to cancer through its relation to potential growth, which again relates to the danger of cancer as being capable of uncontrollable growth. A term of “micronodules” was used as a sign that changes may be interpreted as “mere changes” without an actionable relation to cancer. In their focus on precision and accurate measurement, the doctors come to act with inattention to the indeterminacy of the sign. As Antonia Walford suggests in the case of climate change scientists, measurement breaks the continuity of a world in motion into specific determinable points (Walford Citation2021). For the pulmonary doctors, it became possible to establish a straightforward relation between the visualized tissue change, size, and a recommended surveillance plan. To illustrate these dynamics, the doctors’ discussion of Henrik’s CT images is instructive. Here, the negotiation of the tissue change as “probably not cancer” mediates a focus on size:

I was sitting in the back of the small room, next to the pulmonologist, where I could see the radiologist sitting by the computer and her screens. The large PC screens displaying CT images was the main light source in the room, as the roller window blinds blocked out natural light to enhance the contrasts of black and white on the CT images. This discussion involved the CT images of Henrik, case number 14 out of 16 (and four more not on the list).

The radiologist read aloud the name of the patient and described the imaging modality. Then she turned away from the computer screen and added, “Ah, this was the one with no referral. It just says all sorts of odd things about blood tests.” She continued to describe that Henrik had been coughing for some time, was a non-smoker, and that a small, round opacity [a tissue change] had been detected in one of his lungs.

Then the pulmonologist interrupted asking, “What are the dimensions?”

Radiologist, “9 mm.”

Pulmonologist, “Can you measure it again?”

The radiologist laughed, “Yes. What do you want it to be? I can get it to 8.5 mm.”

Pulmonologist, “All right. Then a CT scan again in three months’ time.”

Both of them wrote the conclusion on their papers and continued with patient number 15.

After the conference, the pulmonologist and I rushed from the radiology department through the labyrinthine corridors in the hospital to the pulmonology department. I told her that patient number 14 was interesting from my point of view and asked, “It seemed like you and the radiologist weren’t that worried?” The pulmonologist nodded and agreed. She explained that she wanted to be sure that the change could not be re-measured to be below the threshold of the most intense surveillance. She wanted to check whether a repeated CT scan in three months was necessary. At that point in time, it was.

At the clinical conference, the doctors tried to stabilize the sign chain of tissue change and “nothing.” By questioning the measured size, the pulmonologist draws attention to difference, and a possible indexical relation between size and tissue change. Thus, questioning size establishes a crack between sign and object. The relation between size measured at the CT image and the tissue change is still iconic in the perception that the tissue change is actually there with some stable properties. However, the indexical relation is also present in the attempts to negotiate size. At this moment in the sign process, the pulmonologist points toward something that is not yet stable: There is a distance between image and tissue change that makes it possible to negotiate size. Perhaps the size could be smaller? The answer to this question determines the interpretation, “I can get it to 8.5 mm.” Acknowledging these constraints of the specific sign, the doctors need to interpret and act in a specific way, and they decide to recommend the most intense three-month surveillance scan, despite their conviction that this change will not turn out to become cancer.

Still, at times, the relation between size and surveillance is more open; size can be bent to align more with the perceived understanding of cancer potential and the effect (interpretant) the doctors intend to be produced: “nothing” or “something.” In the case of Henrik, he later granted me access to his patient records. In a summary, I could read that the initial 9 mm tissue change that was re-measured as 8.5 mm at the clinical conference was described as “measuring approx. 8 mm.” In the second summary, the tissue change was described as “approx. 0.7 cm.” These differences in measured size have no practical significance as the recommended intervals for surveillance stayed the same. However, they clearly indicate that the doctors perceived the tissue change to be “nothing,” a “mere tissue change.”

Additionally, size as an indexical sign of “nothing” pointing away from cancer is also related to other characteristics of the detected tissue change. If a tissue change seems “regular” without spikes and “delimited” (velafgrænset), the doctors may tinker with the relation between size and surveillance. An “incidentally detected 9 mm [change]” that is “difficult to see, but appears right after a blood vessel” could be interpreted by the radiologist as “perhaps it’s all just vessels” (måske er det hele bare kar). Thus, the effect becomes a questioning of the surveillance interval of three months (as the size would indicate). Instead, settling on the tissue change as “nothing,” the doctors recommended an interval of six months. In other words, as size measured on CT images is also understood to be in an iconic (actual) relation to the existing tissue change in a person’s lungs, it becomes an indication for surveillance even though it may not be understood as a sign of cancer in some cases. As an icon, the doctors cannot do away with the CT-visualized tissue change.

The CT image of a tissue change is somewhat out of time: In the iconic relation between size and tissue change, it signals a matter-of-fact statement about existence (“here is a tissue change of this size”) that does not in itself point toward a temporal process. As shown, this fact-like attribute was constituted in the processes of signification that were negotiated at the clinical conference including the materialities of tissue changes as techno-phenomena (Barad Citation2007). In the second signification process away from cancer, I will introduce the question of “growth” as inscribing the tissue change and its signs in time. This is done when the doctors compare new CT images with older images.

Time and stability

The second pair of signification is time and stability. In the case of tissue changes, the pulmonary doctors anchor “time” by comparing new CT images with an older scan of the same patient. If they can show stability or slow growth of a change, it becomes an indication that this change is “probably nothing” and will not cause suffering. Whether it could be (or become) a rather slow-growing cancer may still be indeterminate, but the rate of progression and its potential for suffering and death seem minimal. The relation between time and cancer is often portrayed as “the sooner the better” (Andersen and Tørring Citation2023; Aronowitz Citation2001). This paradigm of “early diagnosis” forms part of the clinical rationale for recommending surveillance for tissue changes. A central assumption is that cancer tumors grow with significantly higher rates than other changes. Rapid growth is, therefore, a strong indication for cancer. Yet, “cancer time” is specific for different cancer types and where in the specific cancer story that time is unfolding. For instance, some tissue changes may be evaluated to have grown too rapidly in a few weeks to indicate cancer. Furthermore, even if a tumor has not been classified as cancer, a tumor that grows may still damage the surrounding tissue and cause suffering, thereby making the distinction between cancer and not-cancer less important from both a clinical perspective and a patient perspective (Llewellyn et al. Citation2018). Still, for most patients being diagnosed with “cancer” does imply a distinctive experience enforcing dread and fear or even stigma (Bennett et al. Citation2023; Jain Citation2013).

Recalling that an index has a relation of pointing to the object it represents, I suggest that when considering “growth,” the relation between CT image and tissue change is characterized by this pointing toward potential cancer. An index brings a possible future into the present by pointing to an event or object: the entity of the sign says “look here toward this object, this might mean this future.” As Kohn explains, indexes “encourage us to make a connection between what is happening and what might potentially happen” (Kohn Citation2013:33), in this case the potential of cancer. For the pulmonologist, interpreting size becomes an indeterminate index of the tissue change that may (or may not) hold a future of cancer. For the pulmonologist, size might indexically point toward growth, which indexically points toward cancer. This is the focus of attention, not the tissue change in itself. Thus, size as a sign is iconic in referring to the actual size of an actual tissue change, but it is also indexical when anchored in time and pointing toward stability or possible growth. The openness of interpretation in the pointing toward a possible future is a central element in the indeterminacy of tissue changes. This indeterminacy drives the doctors’ work on stabilizing an interpretation of “nothing.”

Thus, when stability is shown in time, through comparison of new CT images with older CT images of the same patient, it becomes a sign of movement between tissue change and cancer that diverts away from “something” toward “nothing.” This mediates the interval of surveillance, with radiologists sometimes arguing about a detected tissue change that “it’s nothing,” “it seems unimportant,” or “it doesn’t shout malignancy.” Yet, even though a tissue change seems like no-thing, surveillance is often recommended if the passing of time did not confirm possible stability. The surveillance becomes a safety net to not miss out on cancer. That cancer cannot be missed is central to this form of vigilant biopolitics. Thus, within the indexicality of the sign and in the specific setting of prioritizing “early diagnosis,” there is always a residue of meaning that makes it impossible for the doctors to annul the potential relation to cancer. Here, semiotic indeterminacy points to how cancer as anticipation (Andersen and Tørring Citation2023) makes it impossible to tell “nothing” and “something” apart, since “nothing” is inherently anticipated to become “something.” This indeterminacy is also present when the doctors look back in time and compare the past with the present on the backdrop of a re-opening and re-interpretation of a detected tissue change.

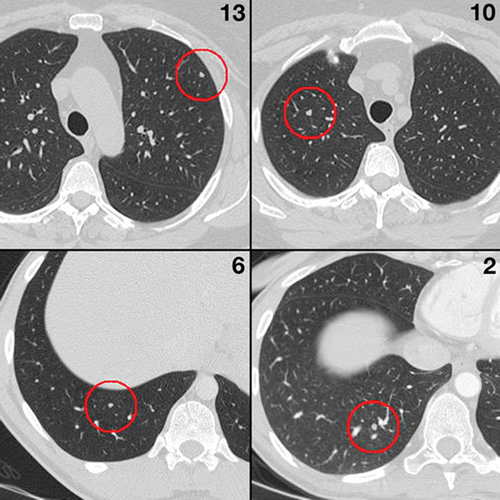

Unlike some public imaginaries, time in the case of cancer is not necessarily measured in a few months, especially not when considering small changes. As a pulmonologist explained to me about a specific case of complaint, “one year more or less was diagnostically insignificant.” The pulmonologist elaborated on a recent episode, where one of the radiologists at the hospital had overlooked a 4 mm tissue change three years earlier (see ). Or as the pulmonologist put it, “rather, the radiologist didn’t describe it.” Three years later, the patient had a CT scan again, and it turned out that “something” had developed exactly where the doctors had seen this 4 mm something three years back.

Strictly speaking, the clinic could have detected the cancer one year earlier than it did, or, the pulmonologist explained, “supposedly we could.” If the doctors had recommended a surveillance scan of the change one year after the first scan and then again after a year, as they should have according to the guideline, possible growth could have been detected. Yet, this would be on the premise that the tissue change had really grown during the standard two-year surveillance period, because, as the pulmonologist imagined, the doctors might also have closed the case after two years if nothing had happened.Footnote2 In other words, it is actually impossible to know whether the tissue change had grown gradually during the three years or more rapidly in the last year, which would not have been covered by the surveillance. Still, the Danish Agency for Patient Complaints had decided that the doctors should have offered surveillance, and the Agency had reprimanded the clinic for not having done it. At the same time, the patient was not granted any compensation because the supposed delay did not have any diagnostic significance after all as it did not influence treatment options. As it happened, the treatment would have been the same after two years as after three years. With this cancer, one year more or less did not matter.

The above case illustrates how the meaning-making process of tissue changes continuously resurfaces. Thus, the possibility that a detected tissue change proves to be cancer in the future is an instance in which the indexical relation signifying cancer becomes iconic. Timmermans (Citation2017) refers to this as a process of reification. In the case of tissue changes, past interpretive actions are re-configured in light of the present lines of signification. In other words, there is no singular or definitive process of signification; it may always begin again. This possibility makes the interpretation of tissue changes as “nothing” inherently instable. Furthermore, in line with Lakoff’s suggestions on vigilant biopolitics (Lakoff Citation2015:45), the practices of extended surveillance in the predictive healthcare complex are increasingly condensing as attempts to not be held accountable (or hold oneself accountable as a doctor or patient) if lung cancer does develop.

Within these specialized processes of signification, cancer lurks as an underlying reference point. It is a threat resonating in daily clinical practice; an insistent presence. Although it may sometimes materialize in a specific tissue change, the relation to cancer is most forcefully expressed when interpreted in symbolic form. Symbols refer indirectly through convention. Unlike icons and indexes, symbols “can retain referential stability even in the absence of their objects of reference” (Kohn Citation2013: 55). This allows a form of subjunctive “what if” that enables a sharing of what might be (Whyte Citation2005). Here, the “what if” of cancer, with all its symbolic relations, drives the surveillance for CT-detected tissue changes. Even though cancer is not present and size, time, and other characteristics point toward “nothing,” the symbolic relation to cancer may not be fully cut. After all, no matter how unlikely the event of cancer suffering related to the specific tissue change might be, these surveillance regimens and the vigilance that guides the CT scanning practices are about cancer; about ensuring timely diagnosis and treatment of cancer to enhance survival. As I have shown, the processes of distinction and indistinction, thus, drive the precautionary diagnostic cycles to continue and re-surface.

Conclusion: Expanding diagnostics

The detection, evaluation, and surveillance of tissue changes is a thoroughly social and situated achievement: specified referral possibilities, healthcare infrastructures, cancer imaginaries, CT scanning possibilities, doctors of various kinds, patients, relatives, and bodies, which all affect the configuration of “tissue changes” as techno-phenomena. Inspired by Peircean semiotics, I have documented “tissue changes” as a process of signification in detail. I have argued that, in practical judgments among doctors, the measured size of a tissue change is understood as an icon of the actual tissue change in a body, and the CT-detected tissue change serves as an index pointing toward a possible relation to cancer. This also expresses a symbolic relation to cancer, even if this relation to cancer has not yet materialized and, most likely, never will.

Overall, “tissue changes” as a case testifies to an increasingly vigilant healthcare system, where the surveillance of potential illness drives indeterminacy and expands medical semiotics. The prioritization of cancer control in the predictive healthcare complex produces an infrastructure that encourages diagnostics due to increasingly smaller changes and vague suspicions. As a diagnostic infrastructure, the vigilant form of cancer control depends upon an extensive pathway or workflow outside the main cancer patient pathway that is occupied with filtering out “nothing,” with determining the character of the specific tissue change and ruling it out as a thing. In the Danish setting, cancer control in the shape of diagnostics and “at risk” surveillance seem to bypass discussions about resource-management and prioritization. Even though these discussions are fiercely debated in other arenas e.g. when considering costly treatment modalities, they are generally not publicly voiced when considering “early diagnosis.” Instead, these practices of CT surveillance may be understood as part of “ordinary medicine,” where the technological possibilities and imaginaries of modern medicine drives expectations of longevity through controlling life and death (Kaufman Citation2015). Kaufman suggests that the desire for disease prevention and control ─ “watching, waiting, testing, and treating” (Kaufman Citation2015:21) ─ is taken for granted as an essential part of “good” healthcare. Consequently, this kind of “ordinary medicine” frames the body as “infinitely fixable” and life as “infinitely extendable” (Kaufman Citation2015:26). At the same time, I suggest that these moral and political concerns about “early diagnosis” conceal the effects of the vigilant politics of care on specific bodies, as this biopolitics continuously re-produces recalcitrant inequities in healthcare (Andersen et al. Citation2023; Bennett et al. Citation2023).

Further exploring cancer temporalities, research suggests that cancer is increasingly thought of as a chronic condition to live with in the everyday (e.g. Arteaga Pérez et al. Citation2022 Greco and Graber Greco and Grabers Citation2022). Referencing Emily Martin in her work on bipolar disorder, Lenore Manderson argues that a cancer diagnosis has become something to live “under” (Manderson Citation2022:268). A diagnosis of cancer has a social and biological “afterlife,” as it tends to continuously reconfigure everyday life, subjectivities, and sociality with a continuous living “in prognosis” (Jain Citation2013). The diagnostic process of “tissue changes” enhances this expansion of what may be called a diagnostic temporality. Unlike conceptualizations of a diagnostic “moment,” “event,” or “act” (Smith-Morris Citation2016), in the case of morphological changes, diagnostic time and medical semiotics are expanded in terms of a path that does not have a clear beginning and never really stops, since the signification of “nothing” is a continuous achievement. Diagnostics, here, is not “an event” that is clearly distinguishable from an everyday routine. Instead, it diffuses subtly, also for the people living with surveillance (Frumer et al. Citation2021). On this trajectory of not becoming cancerous, there is always a residue of meaning that cannot be annulled. As I have suggested, at the scale of specific interactions, this meaning may be only temporarily annulled if someone (doctor, patient, or relative) takes the responsibility for the annulment.

Notably, the presented case documents how doctors aiming to diagnose do not necessarily seek a stable ground from where to intervene. Diagnosing “nothing” is not about” fixing the terrain,” as Llewellyn et al. (Citation2018:415) argue, when defining biomedical diagnosis as moments that fixate uncertainty in static landscapes in order to act. Instead, diagnostics as a process of signification is emerging, relational, and dynamic. A semiotic approach highlights these aspects, and it also helps tease out how healthcare infrastructures that encourage vigilance toward ruling out cancer will expand diagnostic time and meaning, since object, sign, and effect are always underway. The signification may only be put to rest firmly – “this is cancer” – when looking back. As in other cases arguing against the pre-requisite of stability in knowledge practices (Singleton Citation1998; Vernooij Citation2021; Walford Citation2017), I conclude here by emphasizing how the doctors’ ability to encompass semiotic indeterminacy contributes to maintaining the vigilant healthcare infrastructure. Additionally, it produces a temporal reframing of cancer as anticipation. In these processes, establishing signs of “nothing” to encompass the indeterminacy of not-knowing what may constitute a future cancer makes cancer control and the extended surveillance for tissue changes robust and viable. Otherwise, if every detected sign of potential cancer was to be surveilled, the system would end up imploding. This a double bind: even though these practices expand medical semiotics, they also secure this expansion through the filtering out of “nothing.”

Acknowledgments

I am grateful to the doctors and nurses at the diagnostic clinics as well as the people with tissue changes who agreed to be part of the project and who generously allowed me into their daily (work) practices and engaged in dialogues. Thank you to the three anonymous reviewers for insightful comments that helped further the article and to the editorial team at Medical Anthropology. This type of study needed no approval from the Committee on Health Research Ethics in Denmark, as no biological material was included. The project was registered in the record of processing activities at the Research Unit of General Practice in accordance with the provisions of the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) of the European Union. All material was encrypted and stored on secure servers domiciled in Denmark.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Michal Frumer

Michal Frumer is an anthropologist and postdoctoral researcher at the Research Unit of General Practice, Aarhus and Aarhus University Hospital, Denmark. Her interests revolve around the management of signs, uncertainty, and ethical predicaments in diagnostic work, as well as questions of prioritization and trust in biomedical expertise. She draws on insights from her PhD studies on pulmonary nodules and the production of “precancerous populations” for this article.

Notes

1. Peirce also described the sign’s relation to itself (describing the quality of the sign) and the sign’s relation to its interpretant (describing the level of generality for the effect produced). I restrict the article to the triad about the sign’s relation to its object, as this is sufficient to argue for the work that needs to be done in the signification process away from cancer.

2. See Brodersen et al. (Citation2014) for an account of the heterogeneity in cancer growth patterns and Brodersen et al. (Citation2020) for a specific analysis of the likelihood of overdiagnosis in lung cancer screening. See Welch (Citation2004) for an engaging and accessible exploration of the pitfalls of medical testing and screening.

References

- Adams, V., M. Murphy, and A. Clarke 2009 Anticipation: Technoscience, life, affect, temporality. Subjectivity 28:246–65. doi:10.1057/sub.2009.18.

- Andersen, R. S. 2017 Directing the senses in contemporary orientations to cancer disease control: Debating symptom research. Tidsskrift for Forskning i Sygdom og Samfund [Journal for Research in Disease and Society] 14:145–67. doi:10.7146/tfss.v14i26.26282.

- Andersen, R. S. 2023 Introduction: Crafting cancer anticipations. In Cancer Entangled: Anticipation, Acceleration, and the Danish State R. S. Andersen and M. L. Tørring, eds. New Brunswick, Camden, and Newark, New Jersey, and London: Rutgers University Press.

- Andersen, R. S., S. M. H. Offersen, and C. H. Merrild 2023 Noisy bodies and cancer diagnostics in Denmark: Exploring the social life of medical semiotics. In Cancer and the Politics of Care. L. R. Bennett, L. Manderson, and B. Spagnoletti, eds. Vol. Pp. Pp. 190–209. UCL Press. doi:10.2307/j.ctv2tsxmmn.14

- Andersen, R. S., and M. L. Tørring (eds.) 2023 Cancer Entangled: Anticipation, Acceleration, and the Danish State. New Brunswick, Camden, and Newark, New Jersey, and London: Rutgers University Press.

- Aronowitz, R. A. 2001 Do not delay: Breast cancer and time, 1900-1970. The Milbank Quarterly 79:355–86. doi:10.1111/1468-0009.00212.

- Arteaga Pérez, I. 2021 Learning to see cancer in early detection research. Medicine Anthropology Theory 8(2):1–25. doi:10.17157/mat.8.2.5108.

- Arteaga Pérez, I., S. Gibbon, and A. Lanceley 2022 Therapeutic values in cancer care. Medical Anthropology 41:121–28. doi:10.1080/01459740.2021.2021902.

- Barad, K. M. 2007 Meeting the Universe Halfway: Quantum Physics and the Entanglement of Matter and Meaning. Durham: Duke University Press.

- Bennett, L. R., L. Manderson, and B. Spagnoletti 2023 Cancer and the Politics of Care: Inequalities and Interventions in Global Perspective. UCL Press. doi:10.14324/111.9781800080737.

- Bogicevic, I., K. S. Rohrberg, E. Hogdall, and M. N. Svendsen 2021 The somatic mode: Doing good in targeted cancer therapy. New Genetics and Society 40(2):178–98. doi:10.1080/14636778.2020.1799345.

- Brodersen, J., L. M. Schwartz, and S. Woloshin 2014 Overdiagnosis: How cancer screening can turn indolent pathology into illness. APMIS 122:683–89. doi:10.1111/apm.12278.

- Brodersen, J., T. Voss, F. Martiny, V. Siersma, A. Barratt, and B. Heleno 2020 Overdiagnosis of lung cancer with low-dose computed tomography screening: Meta-analysis of the randomised clinical trials. Breathe 16:1–12. doi:10.1183/20734735.0013-2020.

- Cantor, D. (ed.) 2008 Cancer in the Twentieth Century. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

- Frumer, M. 2023 “Keeping an eye on it”: Infrastructures of lung cancer uncertainty and certainty. In Cancer Entangled: Anticipation, Acceleration, and the Danish State R. S. Andersen and M. L. Tørring, eds. New Brunswick, Camden, and Newark, New Jersey, and London: Rutgers University Press.

- Frumer, M., R. S. Andersen, P. Vedsted, and SMH. Offersen 2021 In the meantime”: Ordinary life in continuous medical testing for lung cancer. Medicine Anthropology Theory 8(2):1–26. doi:10.17157/mat.8.2.5085.

- Gould, M. K., T. Tang, I. A. Liu, J. Lee, C. Zheng, K. N. Danforth, and A. E. Kosco, et al. 2015 Recent trends in the identification of incidental pulmonary nodules. American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine 192:1208–14. doi:10.1164/rccm.201505-0990OC.

- Greco, C., and N. Grabers 2022 Anthropology of new chronicities: Illness experiences under the promise of medical innovation as long-term treatment. Anthropology & Medicine 29(1):1–13. doi:10.1080/13648470.2022.2041550.

- Jain, S. L. 2013 Malignant: How Cancer Becomes Us. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Kaufman, S. R. 2015 Ordinary Medicine: Extraordinary Treatments, Longer Lives, and Where to Draw the Line. Duke University Press.

- Keating, P., and A. Cambrosio 2012 Cancer on Trial: Oncology as a New Style of Practice. University of Chicago Press.

- Kirkegaard, P., A. Edwards, and B. Andersen 2019 A stitch in time saves nine: Perceptions about colorectal cancer screening after a non-cancer colonoscopy result. Qualitative study. Patient Education and Counseling 102:1373–79. doi:10.1016/j.pec.2019.02.025.

- Kohn, E. 2013 How Forests Think: Toward an Anthropology Beyond the Human. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Lakoff, A. 2015 Real-time biopolitics: The actuary and the sentinel in global public health. Economy and Society 44:40–59. doi:10.1080/03085147.2014.983833.

- Llewellyn, H., P. Higgs, E. L. Sampson, L. Jones, and L. Thorne 2018 Topographies of ‘care pathways’ and ‘healthscapes’: Reconsidering the multiple journeys of people with a brain tumour. Sociology of Health & Illness 40:410–25. doi:10.1111/1467-9566.12630.

- Löwy, I. 2010 Preventive Strikes: Women, Precancer, and Prophylactic Surgery. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

- Manderson, L. 2015 Afterword. Cancer enigmas and agendas. In Anthropologies of Cancer in Transnational Worlds. Vol. Pp. H. F. Mathews, N. J. Burke, and E. Kampriani, eds. Pp. 241–54. New York and London: Routledge.

- Manderson, L. 2022 Cancers’ multiplicities: Anthropologies of interventions and care. In A Companion to Medical Anthropology. M. Singer, P. I. Erickson, and C. E. Abadía-Barrero, eds. Vol. Pp. Pp. 260–74. John Wiley & Sons Ltd.

- Offersen, S. M. H., M. B. Risør, P. Vedsted, and R. S. Andersen 2018 Cancer-before-cancer: Mythologies of cancer in everyday life. Medicine Anthropology Theory 5:30–52. doi:10.17157/mat.5.5.540.

- Pedersen, K. Z., and A. R. Obling 2020 It’s all about time: Temporal effects of cancer pathway introduction in treatment and care. Social Science & Medicine 246:112786. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2020.112786.

- Peirce, C. S., N. Houser, J. R. Eller, A. C. Lewis, A. De Tienne, C. L. Clark, and D. B. Davis 1998 The essential peirce. In Selected Philosophical Writings Vol. 2. Pp. 1893–913. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

- Rubin, G. D., J. E. Roos, M. Tall, B. Harrawood, S. Bag, D. L. Ly, D. M. Seaman, et al. 2015 Characterizing search, recognition, and decision in the detection of lung nodules on CT scans: Elucidation with eye tracking. Radiology 274(1):276–86. doi:10.1148/radiol.14132918.

- Singleton, V. 1998 Stabilizing instabilities: The role of the laboratory in the United Kingdom cervical screening programme. In Differences in Medicine M. Berg and A. Mol, eds. Pp. 84–104. New York, USA: Duke University Press.

- Smith-Morris, C. 2016 Introduction: Diagnosis as the threshold to 21st century health. In Diagnostic Controversy: Cultural Perspectives on Competing Knowledge in Healthcare C. Smith-Morris, eds. Pp. 11–34. New York; London: Routledge.

- Stevenson, L. 2014 Life Beside Itself: Imagining Care in the Canadian Arctic. Berkeley, USA: University of California Press.

- Sundhedsstyrelsen [Danish Health Authority] 2015 Udvikling i brug af røntgenundersøgelser i Danmark – med fokus på CT 2003–2014, [Developments in the use of radiologic investigations in Denmark - with a focus on CT 2003–2014]. https://www.sst.dk/-/media/Udgivelser/2015/Udviklingen-i-brug-af-r%C3%B8ntgenunders%C3%B8gelser-i-Danmark.ashx.

- Timmermans, S. 2017 Matching genotype and phenotype: A pragmatist semiotic analysis of clinical exome sequencing. The American Journal of Sociology 123:136–77. doi:10.1086/692350.

- Vernooij, E. 2021 Infrastructural instability, value, and laboratory work in a public hospital in Sierra Leone. Medicine Anthropology Theory 8:1–24. doi:10.17157/mat.8.2.5167.

- Walford, A. 2017 Raw data: Making relations matter. Social Analysis 61:65–80. doi:10.3167/sa.2017.610205.

- Walford, A. 2021 Analogy. In Experimenting with Ethnography A. Ballestero and B. R. Winthereik, eds., Pp. 209–18. New York, USA: Duke University Press.

- Welch, H. G. 2004 Should I Be Tested for Cancer?: Maybe Not and Here’s Why. University of California Press.

- Whyte, S. R. 2005 Uncertain undertakings: Practicing health care in the subjunctive mood. In Managing Uncertainty R. Jenkins, H. Jessen, and V. Steffen, eds., Pp. 245–64. Copenhagen: Museum Tusculanum Press.