ABSTRACT

Medical schools are important nodes in the reproduction of medical knowledge, and an often-visited field site for medical anthropologists. To date, the spotlight has been on teachers, students and (simulated) patients. I broaden this focus to look at the practices of medical school secretaries, porters and other staff, investigating the embodied effects of their “invisible work.” Drawing from ethnographic fieldwork in a Dutch medical school, I mobilize the more multisensory term “shadow work” to understand how such practices become part of medical students’ future clinical practices through highlighting, isolating, and exaggerating, necessary elements of their medical education.

I cannot share here an image of the immaculately repaired leather teaching model I was shown one afternoon in the Dutch medical school where I do fieldwork. I cannot show the close-up photograph I took of the rip in the soft worn leather of the truncated mannequin, caused by the awkward pressure of so many medical students’ sweaty palms. I cannot show how the rip was now but a faint scar in the leather-skin, stitched neatly together with suture thread leftover from surgical stitching classes. I cannot show a photograph of how the chamois cloth – chosen carefully at a local hardware store for its texture and its slight stretchiness – created such a perfect soft patch for another of the mannequin’s lesions.

These carefully repaired mannequins are used to teach medical students the embodied skills potentially required while a woman is in labor. The reason I cannot share pictures of the repairs I was shown is because Mieke (pseudonym), the secretary who worked in the medical school and who did many of the repairs herself, asked me not to share the photographs I took. She asked that I only use them for my own “research purposes.” I am still not entirely sure why this is. I know Mieke was proud of the repairs – of her thriftiness with the thread, her stitching and knowledge of materials “learned from her mother” – it was why she wanted to show them to me in the first place. And I know that this work was sanctioned by her manager, for she was given time to do it as part of her workday. Some models she told me needed special care “because they were expensive” (others were merely “replicas”). Yet, she was also unsure of her repairs too, she wanted them hidden: “this was the first time [doing this type of repair], it was quite difficult.” Perhaps she did not want to cause any damage to the reputation of the university, which took pride in its technological innovation? Perhaps Mieke did not think her craftwork met her own or her colleagues’ exacting standards, or that it was even to be considered work? These were among the many unanswered questions that I left my field site with and encountered back at the desk, with the daunting and productive chasm between fieldwork and deskwork stretching between (Strathern Citation2015). I have in some ways betrayed the secretary by sharing the repair in words, however this model has a lot more to teach than a medical lesson about childbirth.

The work involved in the leather mannequin’s care and repair offers to medical anthropology and related fields an expanded understanding of the labor that is so central to, yet largely hidden within, the reproduction of medical knowledge. The cramped storage room with its flickering fluorescent light, where Mieke and I stopped to look at the repairs, is a rather theatrical place to set the opening scene for such an account. Lined top to bottom with shelves crammed with a woolly uterus, unblinking plastic dolls and sticky silicon ovaries, the storage room is part of what is known locally as the Skills Lab. This building and learning place is dedicated to teaching students clinical skills such as gynecological and obstetric techniques, needle insertions or eye examinations.

During my years of fieldwork in this and other medical schools in Australia, studying how medical practice is learned and enacted, I have taken many other photographs. Photographs of the obstetrics models stored in this room for example, photographs where Mieke and her colleagues’ repair work has left traces that are not so easily perceptible – the leather polish, for example, rubbed into the models has been absorbed and is felt only in the lack of cracking and the softness of these expensive simulated women. Care for these models involves significant resources not only of maintenance but also in their purchase, storage, cataloging, and ordering. It is this kind of labor that is the focus of this article. Looking at examples such as what is repaired in a leather model and how it is repaired or looking at how a lesson is set up helps to make explicit, I suggest, some of the details of learning a medical skill which otherwise remain buried in tacit exchanges.

Somewhat speculatively, based on an academic year of doing ethnographic fieldwork in a Dutch medical school, I consider how this labor may have a more lasting effect in the embodied learning of clinicians. Medical schools have long been important sites for ethnographically understanding the making of doctors (e.g Prentice Citation2013; Taylor Citation2011; Underman Citation2015). To date, medical anthropologists and sociologists have developed important insights into concepts such as hidden curricula (Taylor and Wendland Citation2014), sensory skills (Maslen Citation2016; Rice Citation2013) and professional identity (Cassell Citation1991). They have expanded theoretical concepts such as habitus and the clinical gaze (DelVecchio Good Citation1995; Holmes et al. Citation2011). Even if it may not reflect who the ethnographers spent their time with during fieldwork, the written results of these studies often focus on the educators and the educated, the teachers and the students, with excellent exceptions looking at patients in these lessons (e.g. Guarrasi Citation2015; Taylor Citation2011). Less attention has been paid however to other staff in medical schools, those people doing what could be considered the “invisible work” of medical education (see Wyatt Citation2022 for an exception). Yet as others have argued for science, understanding the nature of knowledge production is impoverished without attention to this kind of “behind the scenes” work. In my fieldwork I followed the teaching materials, which led me behind the scenes so to speak, to engage through informal interviews and participant observation with many different kinds of work and workers. To help stretch the frame of focus of learning in medicine beyond the teacher-student dyad, in the next section I consider what we can learn from the body of invisible work scholarship to think through these practices of medical learning.

The invisibility task force

Science and technology studies (STS) scholars, historians of science, and feminist technoscience scholars have long been attuned to the invisible technicians, servants, preparators and laborers of science (Wyatt Citation2022). In these fields, which have many overlaps and points of intersection with medical anthropology, the concept of invisibility has found great momentum since the 1990s. Classic texts include Star and Strauss (Citation1999) article on “invisible work” in science and technology studies and Steven Shapin’s (Citation1989) essay on “invisible technicians” in the history of science. While Star and Strauss used examples of the invisible practices of computer supported cooperative work systems, Shapin’s concern was with the invisible labor that was unacknowledged in scientific research. More recent studies have shed further light on the work of the uncredited (Newlands Citation2021; Plantin Citation2018), the temporality of scientific technician’s work (Bruyninckx Citation2017), the role of trust and value (Wylie Citation2018) and craft (Palfreyman Citation2022; Whiteley Citation2022) in invisible labor, its collective enterprise (Russell et al. Citation2000), and the embodied dimensions of scientific practice (Morus Citation2016; Sharp Citation2011).

Some literature in this domain is particularly pertinent to the Dutch medical school case and the reproduction of medical knowledge I explore there more generally. Ethnographic studies of the “secret life” of objects, such as medical records and insurance paperwork (Van Eijk Citation2017) for example look at the unremarkable and mundane practices entailed in organizing documents in medicine. Some of this research aims to “reveal” the issues and opportunities of focusing on this invisible work (Martin and Wall Citation2008). Research on hospital cleaners investigates how such actors make their work more visible, leaving traces such as a light on or a cleaning smell, traces not always appreciated by others in the hospital (Messing Citation1998). Taking the embodied nature of this labor more centrally (and looking outside of the often-focused upon US context), Craddock’s (Citation2021) study of the hidden role of embroiderers in transplant surgical innovation for example highlights the role of class in medicine. Rapport’s (Citation2008) ethnography of hospital porters in the Scottish city of “Easterneuk” shows how those on the fringes of a medical establishment are part of the fabric of the hospital’s social life (see also Mesman Citation2008; Street Citation2014).

Without addressing issues of class and hierarchy, understandings of how medical practices are enacted and by extension, how medical knowledge is reproduced, will always be partial. This also concerns an understanding of gender politics. Invisible women are the topic of a growing body of academic literature, particularly in many domains of history including medical history. Invisible women have also captured the attention of the public (Cheney and Shattuck Citation2020; Criado-Perez Citation2019). Much important work has also been done to raise awareness and counteract the White privilege inherent in science, education, and technological innovation (Benjamin Citation2019). Intersectional studies of invisibility in medicine, such as Timmermans (Citation2003) essay on a Black technician in STS, or popularly taught in many medical anthropology courses, The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks (Skloot Citation2010) are just two examples which consider the intersections of race, class and gender in medical breakthroughs.

In this small selection of studies of invisibility in medicine, what is considered invisible depends largely on the contexts of the studies, and on the researchers and actors’ viewpoints but is generally the work that does not receive credit, is ignored and absent from historical accounts. The practices I write about in the Skills Lab speak to many of the issues highlighted by these invisibility scholars – the site is steeped in colonial legacies, the actors I write about are largely female (but not only), their work also steeped in gendered assumptions about who, what, and how materials are dealt with. And less evident, though threaded through, are stories of class, part of larger divisions between academic and non-academic staff in university settings.

I build from, and contribute to, the body of literature on invisible labor when considering the practices of those in the Skills Lab. To further contribute to medical anthropological understandings of invisible labor in medical knowledge reproduction however, I return to an earlier term used in some of this literature. This is a term from sociology: “shadow work” (Illich Citation1981). Although Ivan Illich’s (Citation1981) term has now come to be equated with non-paid labor, I find thinking in the shadows more helpful than invisibility/visibility. In the following section I reconsider this word often used in anthropology in methodological and self-reflexive ways, to consider what it means to look not only from but also in the shadows.

In praise of shadows

Looking in, or from, the shadows has a lurking connotation. A shadow cast is ominous. Shadowlands are forgotten places. Shadows are also used in anthropology to describe the positionality of researchers (MacLean and Leibing Citation2007) or the role they might play in a community (e.g., shadowing participants is a term often used in clinical ethnographies where medical doctors are used to the junior doctor shadowing the senior doctor). Here I want to think generatively with the term shadow beyond its methodological connotations to better understand the “shadowy” work in my medical school fieldsite and its relations to bodies and materials.

Shadows form because of light cast upon obstructions; something is both causing the shadow, and in the way. In studies of education the light is mostly cast on certain actors: teachers, students, and occasionally curricula designers. In anthropology, education is considered much more broadly than the institutions of learning (Ingold Citation2018), yet still the focus is mostly on master/apprentice, expert/novice, teacher/learner. By looking in their shadows we see the outlines of these actors’ bodies, but we can also find other people, objects, and places too. For shadows are always connected to other things and connect us to other things. In the case of our own bodies, our shadows can connect to other shadows in distorted dimensions, as children delight in discovering in a puppet show on the wall. The psychoanalyst Carl Jung (Citation2012 [1951]) writes that everyone carries a shadow, forming an unconscious snag, thwarting our most well-meant intentions. One can only become conscious of their shadow with considerable effort.

Acknowledging work in the shadows, just like giving credit to the invisible technicians in scientific papers, takes conscious effort. While Jung is concerned with the individual and moral implications of shadow work, in his book In Praise of Shadows, cultural theorist Junichirō Tanizaki (Citation2001 [1977]: 33) takes shadows into spaces, objects, and architecture:

And even as we children would feel an inexpressible chill as we peered into the depths of an alcove to which the sunlight has never penetrated. Where lies the key to this mystery? Ultimately it is the magic of shadows. Were the shadows to be banished from its corners, the alcove would in that instant revert to mere void.

Shadows are not only dark and painful places but also add depth to what is in the light. This may be, I suggest, where some of the mysteries of how medicine is learned and reproduced around the world may also lie. While invisible implies no trace – invisible pen can only be found when someone rubs a crayon over it, an invisible cloak only if it gets snagged on a branch – shadows are more than a void, they are multisensory, have texture, are seen, felt, and become affectively entangled with bodies.

Shadow (field) work

My conceptualization of shadows in the remainder of this article is inspired by some of the previous literature, but as mentioned, what I develop largely draws on ethnography. I have spent over 10 years conducting fieldwork in the Dutch and other medical schools in Australia, studying sensory learning in medical education. In hospitals and universities, I have spent time with ward clerks, personal service attendants, interpreters, security guards, cleaners, theater technicians, secretaries, engineers, cleaners, porters, and IT staff. I am also the daughter of two parents who could be seen to have worked in shadows, one in the shadows of an educational institution – my mother was an art teacher aide, her work involving anything from firing (and repairing) students’ ceramics, to library research – and my father in architecture firms, designing houses privately on the drawing-board in our home since I was a child. My parents were not always in the spotlight at their workplaces like the teachers or the firms’ partners, but their work was always crafted with skill and care. I am continually drawn to work done in the shadows, finding the nightside of hospital life or the infrastructures of medical work revealing (Harris and Fuller Citation2014), so it was probably then of no surprise that when doing fieldwork in the Skills Lab, my time was spent not only with the teachers and students but also with those in the shadows.

My own fieldwork is part of a larger historical-ethnographic study of the materiality of learning in medical education across sites in West Europe, Central Europe, and West Africa. Our team’s research looks at how students learn the embodied skills of their profession, such as anatomy and physical examination (e.g., listening to hearts, feeling lumps, looking at rashes). In particular we are interested in the materiality of this embodied learning (see also Hirschauer Citation1991; Johnson Citation2007)) – the meaning of chalk and chalkboards, the technologies to teach touch, the colonial legacies imparted through donated objects and the effects of humble instruments like the measuring tape.

Each of our three field sites were filled with shadows. In the Ghanaian site they may be seen in the shade of the intense sun; in the Hungarian site, shadows lie in the green tiled corners of the cool dissecting labs; and in the Netherlands, they inhabit the tutorial rooms where the blinds stay drawn to keep the simulation intact, disappearing as the lights come on automatically when you enter the room. There are many kinds of work in the shadows in these places that I could discuss – preparing dissections and slides for the microbiology classes in Hungary, or the handling required in donation and upkeep of the European models in Ghana. My focus in this article will mainly be on the ethnographic material from the Skills Lab in the Netherlands however, looking specifically at that which highlights the affective nature of shadow work and its role on the materiality of embodied learning and medical knowledge reproduction.

Every day when I arrived at the Skills Lab, I was greeted by the building’s porter Pieter (pseudonym). Sometimes he was looking at the computer, other times labeling urine jars for the medical students’ microbiology laboratory class. When he was not in the glass porter cubicle, he might be out in the car park monitoring unknown cars in the parking lot or showing medical students to the self-practice rooms they had access to, to practice their physical examination skills. “I see everything that is going on here,” he tells me. “I love helping students find rooms, helping the secretaries out … I know many people in the university who fix things or bring things.” As he would greet various passerbys, he would chat about his weekend cycling and with the grandchildren, or the weather, and invariably he asked what I was doing there that day. If I had to meet someone, he would tell me if they were in or not and guess which room I might find them. More often than not though he would already know who and where I was meeting before I arrived, helping me find my way.

Making clinical sense, like learning anything, is rarely solely the concern of teachers and learners. It involves a vast ecology of objects, people, and other elements. Without looking in the shadows, medical anthropological understandings of medical education remain impoverished. We have learned a lot about the kinds of invisibility work that occur in science and medicine, the reasons they exist and the ways that technicians describe this work, but we know less about the consequences this labor has on knowledge formation. How does shadow work become bound up in learner’s bodies? I speculate, based on my fieldwork in conversation with that of my team’s, that shadow work is relational and perceptible, that it is potentially visible, audible and felt in/by learners and their future practice. That is, I suggest that the work which is often described as invisible, and which I describe here as happening in the shadows, has embodied effects on doctors’ ways of knowing medicine. I suggest we can find traces of this by paying attention to what is involved in setting up materials, in the care and craft involved in repairing and maintaining these objects, and in the way in which these material lessons are ordered. Stepping further into this work in the shadows, the next section concerns the learning set-ups.

Setting up teaching materials

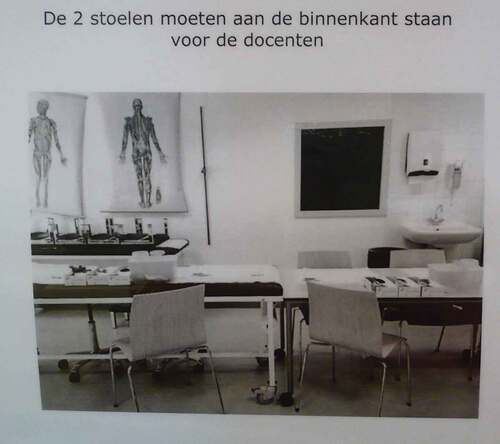

In the Skills Lab, a set-up is taking place. The secretaries of the medical school are arranging the props and materials needed to teach a physical examination lesson. Large leather obstetric models will be used by medical students to practice the techniques involved with the final stages of delivery, the objects’ hollow centers and crevices most important here as teachers squeeze soft suede dolls through the vaginal opening. Blue boxes containing silicon vaginas will be used to train novices’ “haptic memories” of cervical dilation, as the students put their fingers inside and try to learn what 0–10 cm feels like. Knitted uteruses are used with dolls too, to show dilation in action, the ribbed cuff of the knitting allowing for expansion to be made visible and more tactile. These are just some of the many objects that the students learn with. The Skills Lab used to have a template image for how to set up the room (see ), to show where to put which tool and instrument, and how to lay out the table and chairs. In the newer medical school where the Skills Lab moved at the start of my most recent fieldwork, there is no guide. Still, there is a list of required objects, slightly modified by the teachers based on their personal preferences. Models and charts are laid out on the tutorial tables, the tables themselves arranged to allow both tutorial group discussion and space to move around the five beds resembling those in a hospital. The beds are covered with disposable paper sheets and situated besides little trolleys of supplies. In the storage cupboards of each of these tutorial rooms are more models and tools for the students to access if they need them.

Usually in ethnographies of medical education the action starts when the professor or teacher enters the room. The set-up I have just described rarely finds its way into thick descriptions. Instead, we know much more about the visceral details of dissection, or the deep-end learning on the wards. Yet all these classes would have required set-ups, that is, the material conditions required for learning, just as in experiments, to highlight the phenomena in question. Set-ups have captured the interests of ethnographers of sensory learning. Teil (Citation1998) and Latour (Citation2004) both talk about the setting-up required to learn perfume smelling and wine tasting, attending to the materiality of how sensing is trained. Latour (Citation2004: 209) calls these “artificial set-ups,” using the example of the material role of smell kits in learning wine tasting. Teil is more interested in the care involved in maintaining the materials which become part, she argues, of the sensing apparatus, the sensing bodies of the makers. Many sensory trainings involve material set-ups – tea tasting (Xiao Citation2016) and coffee cuppings (Goldstein Citation2011) for example are elaborate rituals with particular tools.

What does a set-up do in these learning environments, and what is the role of those who set-up in this learning? What is happening in medical education I suggest is that the set-up works toward eliminating distraction in a lesson and organizing knowledge, just as technicians iron “the glitches” out of a scientific experiment (Barley and Bechky Citation1994). The lessons in the cases I and my team studied aimed to simulate the reality it speaks to, the clinical encounter, rather than replicate it. That is, the artifice was often not disguised, but rather the simulation attempted to extract a particular part of a clinical encounter for learning.

The set-up works by arranging, in a kind of mise-en-place (Schlegel et al. Citation2019), the tools and materials that enable learning to happen smoothly, without glitches, and those setting-up thus become an integral part of the lesson. The secretaries and technicians do not just “follow” the plans and protocols provided. They enacted them, with their own individual preferences, and they had critical opinions on how things should be run. I saw how these shadow workers were part of Skills Lab meetings and discussions on the clinical trainings. In workshops and presentations of our ethnographic project we would give in the Skills Lab for example, the secretaries and planning staff would often be present, sharing their knowledge of the objects we were interested in, telling stories of their use. At the same time, the technicians and secretaries also contributed to consistency and sameness in the lessons, so that the students, year after year, or within the same year group, can learn a similar lesson, and can later build differences upon these first learnings.

Timmermans (Citation2003: 200–201) reminds us that a laboratory is “not just the locale where science takes place, but it might also become a preferred intermediary to negotiate a particular division of labor grounded in occupation and race … in the laboratory, marginal people might accumulate autonomy and authority that would otherwise remain inaccessible.” In skills laboratories, the set-up can also be a place for actors to take charge. An excellent example of this is the gynecological teaching assistant (GTA) who has dedicated her time and her body to guide medical students in their learning of the pelvic examination. Underman (Citation2022) writes about how GTAs are very careful with the set-ups in their lessons, particularly concerning the use of gloves. They may bring their own boxes of gloves if the medical schools’ supplies are not satisfactory, always keeping an eye on how gloves are being handled, as this is the point of contact between their own bodies and those of the learners.

In the medical school in the Netherlands, the setting up time was certainly the domain of the secretaries and technicians. I found it very difficult to access the secretaries in the Skills Lab when they were involved in setting up lessons. Setting up for the assessment periods were particularly busy and important times. Just as with crediting in scientific work (Timmermans Citation2003: 214), this labor is rarely described or made an obvious part of the lesson, yet it leaves, I suggest, its perceptible trace in the way the stories are told and embodied in the lesson. The work that is done in the shadows, in the tutorial rooms before the teacher unlocks the door to the students, meaning that there are fewer distracting complexities. The material performances that are taking place in the shadows of the medical schools, I believe, are part and parcel of the sensory skills learned. In the next section I look at how those in the shadows of medical schools look after these materials, expanding on the vignette at the beginning of the article.

Care and repair

Every summer the secretaries in the Skills Lab would arrange many of the teaching models on tutorial tables in the empty classrooms and inspect them carefully, searching for those in need of repair or discarding that year. Numerous other teaching materials would need some care as well in the quiet summer months, not only the expensive leather mannequins. Traces of this work could be found in the cupboards and classes that followed if you looked closely. Opening the pencil sharpeners by the sinks in each room for example might reveal dermatological pencil shavings (or eyeliner pencils), which secretaries prepare for the respiratory examination lesson to help the students with the embodied skill of marking out the lung sounds they hear with stethoscopes. Cupboards and side-drawers and other storage places would be neatly stacked and labeled, again by the secretaries. The teachers who take the classes on microbiology also clean the microscopes, they inspect the lens and prepare the slides. The secretaries stitch broken pediatric dolls’ toes and glue back missing parts.

There was a sense of salvage and upcycling of materials at the Skills Lab in Maastricht. The concept of repair and care has received a lot of attention in medical anthropology, with many scholars working on this topic more recently drawing from the speculative feminist work of Maria Puig de la Bellacasa (Citation2017). Her work is particularly relevant because of her attention to materiality and touch. She rethinks Joan Tronto’s influential work on care to consider care as a “concrete work of maintenance, with ethical and affective implications” (de la Bellacasa Citation2017: 5). By considering labor/work, affect and ethics together, she offers a useful philosophy to think about the kind of care practices we see in the Skills Lab shadows. For de la Bellacasa (Citation2017: 43), to care is a notion of doing, as an ethical obligation: “we must take care of things in order to remain responsible for their becomings.” She expands (de la Bellacasa Citation2017: 66): “Care stands for necessary yet mostly dismissed labors of everyday maintenance of life, an ethico-political commitment to neglected things, and the affective remaking of relationships with our objects. All these dimensions of caring can integrate the everyday doings of knowledge in and about technoscience.” This is a concept of care that embraces the work of maintenance, and at the same time it is an idea which brings care and maintenance into the technoscientific work of medical knowledge reproduction. Repair and maintenance has captured the attention of a growing body of anthropologists as well (see for example Jackson Citation2015). Despite this interest, the repair of materials in educational contexts has eluded attention to date. Similarly, little has been written about repair work in medical education research, despite medical practice being a profession seen as doing care work. What does it say, when those taking care of things in the classroom are in the shadows, and not the clinicians-in-training? Might this open up ethical questions of how relations to patients-in-the-future are being taught in medical schools, where the care work in the institutions of those being trained to do care work, is so hidden?

While there is literature on medical equipment maintenance (Bahreini et al. Citation2019), we are still in the dark about much of the backstage care and repair that I suggest has an important role to play in the matters of medical knowledge reproduction. What gets repaired? How and by whom? In the Skills Lab the objects that did not make it to repair were those where it was considered that another material or medium, often digital, could replace the learning that it was involved in. Here we see curricula designers involved in the curation of the medical teaching objects, negotiating and navigating with the secretaries their preferences. Skills Lab teachers would also “save” their favorite objects from discard – a beloved knitted uterus was an example of this. These were objects that taught a sensory lesson in a particular way that the digital alternatives could not. Some of these objects such as the woolly uterus, also dolls for pediatric examination techniques, were handmade by teachers. This work was not always valued at the time – Janne (pseudonym), a teacher who made eight pediatric dolls to assess hip examination skills (see ) for example describes how the male pediatricians in the hospital were highly skeptical of her handmade creations. Her doll however, made of cheap and locally sourced materials with extra stitching to indicate kneecaps, was able to teach the clinical examination skill of child hip examination in a way that the plastic models could not. Medical students need to be able to learn how to flex a young baby’s hip quickly and expertly, and the woolen joints offered a tactile solution.

The practices of caring and repairing, as well as making these tools, are integral to the highlighting, isolation, and exaggeration that is required in a lesson. The doll for example is simple in its design, without distracting features. It is used solely for teaching and assessing hip examination, not for any other aspect of the exam. And finally, the flexibility of the hip of the doll means that the flexion and movement can be exaggerated. Thus, this object can closely attend to the sensory details that are most important for the lesson – the flexible hips of the doll in this example, or the ribbed cuff of the uterus for cervical dilation in the woolly uterus – allowing for the skill to be ingrained through an embodied and material lesson that is felt and remembered by students.

Making in medical education still happens in the shadows, to be occasionally “unearthed” by anthropologists (Hallam Citation2013) and entrepreneurs (Young Citation2021). Craftwork has had an important role in scientific knowledge production in other domains such as dolls houses in forensic science (Goldfarb Citation2020) and crochet in mathematics (Wertheim et al. Citation2005). While many of the female technicians working in mid-20th century London laboratories who historians Hartley and Tansey (Citation2015) spoke to reported being hired due to skills in sewing for example, female scientists using craft methods such as the dollhouse miniatures and crochet have also been celebrated (often decades after initial skeptical responses) for revolutionizing their fields (Criado-Perez Citation2019: 310). Those who make their own learning tools may be, along with the few scientists who make their own instruments (Mody Citation2005), a rarity in medicine, however it may also be that such practices are more common than medical education ethnographies and research lead us to believe.

Digital technologies are certainly changing the nature of this work, and many staff at the Skills Lab were reluctant to take on more digital aspects in their teaching, already suffering from the slow smartboards. Many preferred to work with the knitted and leather objects. Still, digital technologies of education change the nature and priorities of shadow work in the Skills Lab, work which may or may not be staying less in the shadows as teaching moves further online. While increased digitization does not necessarily diminish shadow work, the abstract universalism and internationalization that comes with many digital learning materials may. Work in the shadows not only enhances the highlighting, isolating, and exaggeration in lessons, but also localizes knowledge production and reproduction too. It contributes to some kind of work persisting over others, obvious in the Skills Lab through what is retained in the transition from material teaching models to digital teaching models, allowing for the teachers who prefer the sensory lessons with physical materials.

Thus, shadow work involves more than technical assistance in the ecology of practices in a medical school. It is has more impact, I would suggest, on training bodies. Shadow work is part of the material arrangements that get entangled in the embodied learning of the novices. That things are laid out well and run smoothly sends messages, but moreover, the kinds of materials they work with, materials repaired and cared for, also leaves traces in their future clinical encounters. It may be that these traces include that the caring for materials is done by others, and not the clinician, something to think further about as we face a material crisis in medicine, with excessive waste. The nature of shadow work in medical education will no doubt continue to evolve, with changing technologies requiring changing skills and changing technicians (Wylie Citation2018), and we need to pay attention to the effects of this in the broader ecology of learning, in medicine.

Conclusion

The shadows at the interstices of the ribs seem strangely immobile, as if dust collected in the corners had become part of [the paper] itself. (Tanizaki Citation2001 [1977]: 34)

In a medical school, a lesson takes place. It could be with the obstetric model that appeared in the opening scene, it could be with another material. The shadows seem still, strangely immobile in the interstitial spaces of the skeleton’s ribs standing inert in the corner of the tutorial room and dissection theater, in the spaces of the Skills Lab, the university, in any learning place. The dust, not evidence of disuse, but rather of much activity, collects and settles. It swirls when disturbed, and when we pay attention to it. From these shadows emerges the work of setting up a lesson, caring and repairing materials, the craft of making and tinkering.

In her work on biomedical illustration, STS scholar Belsky (Citation2022) writes about the labor required to make biomedical images appear so well crafted as to not be crafted at all and in this article I have put into the spotlight the shadow work involved in making a medical lesson run more smoothly, with less distraction, helping aspects of a skill taught to be highlighted, isolated and exaggerated. I have not had the space here to look at what happens when things go wrong, when the set-up is not right, however my previous work has shown that such “moments of mismatch” (Harris Citation2011) are similarly insightful for understanding the norms, sociomaterial settings, and habits of clinical work. Just as breakdowns reveal hidden infrastructures (Star and Strauss Citation1999), so too do those-out-of-place reveal the taken-for-granted assumptions of a medical institution (Harris and Guillemin Citation2021). It is important to keep in mind though, that smoothness and elimination of friction (Nott and Harris Citation2020) conveys certain messages to the medical student, just as keeping care work in the shadows does, messages that may be misleading and have potentially undesirable effects.

In medical schools there are many reasons to keep the arduous work of setting up, caring for, and making materials in medical school lessons out of view of students and the public, to keep the shadow work behind the scenes (Star and Strauss Citation1999: 21). It means for example that the teachers can get on with the task of teaching and show a more finished product. This may also explain why these practices have not appeared in medical school ethnographies. Keeping such practices in the dark however may not only be impoverishing accounts in medical anthropology but also potentially replicating notions of a universal, learnable body that the field has spent decades dismantling. It may also disguise persistent outdated practices and neglected colonial legacies (Nott and Harris Citation2020). There is much more to understand here. In my own fieldwork for this article, I have not undertaken as many interviews with shadow workers as I did with teachers for example, as the importance of their work was most fully revealed after I left the field, and after comparing the Skills Lab material with the other sites in the bigger project. The interviews I did do were largely informal. There is more to understand about these actors, from their own stories about their own ethics of care, about a kind of work which seems to differ from that of invisible technicians in science where their work is more enforced. I suggest that such greater attention to shadow work would mean that medical anthropologists can shed more light on the vast ecology of practices involved in the reproduction of medicine around the world, and more generally, help to pry open the black box of learning a bit further.

The literature on invisible labor and that which focuses on the work of invisible technicians or invisible women for example, has expanded understandings of knowledge production in science and medicine. These scholars have shown that no work is inherently invisible or visible but is made to be so through our social relations, hierarchies, exclusions, biases, and priorities. The people I have focused on in this article also work in a laboratory, like the invisible technicians in the scientific laboratories that historians have studied. But they also resemble the team members of a hospital, part of the network of individuals and infrastructures that are part of our health care systems. From yet another perspective, those in the shadows of medical schools find alignment with the administrators and so-called “support staff” of universities. I hope that insights from the practices I have discussed here may be extrapolated to other medical settings that medical anthropologists may study. For it is often in the moving in and out of the shadows that we get our greatest insights.

A challenge of the work of invisibility studies is that it sometimes feels like a cloak, that the magician (i.e., historian, journalist, TV producer) pulls off to dramatic effect, to reveal the previously unseen practices, work and labor that was hidden underneath. Like others, I am aware of this, and want to try and avoid being the magician unveiling the object beneath the “invisible cloak.” Or in my case, the ethnographer who flicks on the fluorescent lights in a medical school cupboard brimming with handmade, hand-repaired, seemingly silent artifacts waiting to be written about. Just as care for objects comes with ethical obligations, so too does scholarship on this topic. What to share and what not to? What are the impacts of shedding light into the shadows? In this article I have kept some things – names, photographs – in the dark, deliberately. As Star and Strauss write: “on the one hand, visibility can mean legitimacy, rescue from obscurity or other aspects of exploitation. On the other, visibility can create reification of work, opportunities for surveillance, or come to increase group communication and process burden” (Star and Strauss Citation1999: 9–10).

Sensitive therefore to what can happen in an “unveiling,” one of my goals in this article has been to explore whether there may be other concepts which are also helpful to study the practices of those who are not in the limelight; those in the shadows. Invisibility studies have provided many examples and reasons for invisible labor in science but have focused less on the effect of the work, particularly the embodied effects, on knowledge reproduction. In this article I have felt my way into the shadows, with a bias toward praising them, to try and understand more about how shadow work gets embroiled in the social and material learning of doctors-in-training. Looking at the work in the shadows I found traces of how this may become perceptible and articulated, and felt in the atmospheres, affects, materials, and textures of the medical lessons. “Invisible” does not seem to adequately express these sensory impressions created in such work. Shadow work is not imperceptible – it is cast into the very materials and ways of knowing of the medical students.

And yet, something about shadows will always remain elusive. Parents do not check a book out of the library to learn how to form shadow puppets for their children. They remember the creatures and formations that were taught to them, through the hands of their own caretakers. Then they experiment themselves and enact the shadow puppets of their past in these embodied reperformances. Embodied, sensory practices in medical schools and elsewhere also elude easy analysis. Powerful shadow puppetry art installations of contemporary artists such as Kara Walker and William Kentridge more evocatively articulate material histories that have been deliberately buried. They expand an understanding of shadows as not mere “holes in light” (Baxandall Citation1995), but rather multisensory and textured phenomena, literal and metaphorical, magical, political, everyday, subjective and relational.

When “thinking through shadows” (Serres 1982 in Kelly and Sáez Citation2018: 42), medical anthropologists can attend ethnographically to the depths of shadow work, in the creative and lively ways I have focused on here in a Dutch medical school, as well as in darker corners and voids of exploitation and harm. We should look in the shadows, but also at the sources of light, and the obstructions causing them, the institutional barriers, the architecture, the locked rooms and traditions, the assumptions and narratives which mean that practices are not shared, or demand a different kind of unraveling. In medical anthropology medicine is thought of not only as knowledge, but as “practices and sociomaterial configurations” (de la Bellacasa Citation2017: 58). The medicine that the students are learning is intimately connected through practices and materials that entail care, so it seems incongruent that the care of materials, used in the lessons of these careworkers-in-training, remains in the shadows. Could it be that attending more closely to shadow work may be one way of opening up relations of care in medicine, of looking at the insistent yet not easily answerable question of “how to care” (de la Bellacasa Citation2017: 7)? And might this also force us, as medical anthropologists, to think more about the ethicality of such projects making the invisible perceptible? By looking in the shadows and making such affective engagements more explicit we can at least better understand how such practices – our own as researchers, and those in our fields – entangle, stretch and interlace with our bodies and materials, the places we learn in and inhabit, our ways of knowing, in medicine and elsewhere.

Ethical approval

Ethical approval for this research was granted by Maastricht University’s Ethical Review Committee Inner City Faculties (reference number ERCIC_030_01_03_2017) and the Dutch Medical Education Research Ethics Committee (NVMO) (Approval no. 888 and 293).

Acknowledgments

For their ongoing support, generosity and inspiration for this research, I extend my thanks to the present and former staff of the medical school where my fieldwork was based, particularly all those whose work I have mentioned in this article. The article has benefited in its writing from feedback at my research group’s annual Summer Harvest (2021), especially by Flora Lysen who provided detailed comments, as well as Mareike, Denise, Jacob, Lea, Jo, and Dani. My thanks to Valentijn Byvank for introducing me to Tanizaki’s book, to the anonymous reviewers for their thorough reading and constructive, critical comments and to the journal editors for working with me on the piece. Finally, the article was born out of a comparative project called Making Clinical Sense, and I am especially grateful for inspiring collaborations with Rachel Vaden Allison, Andrea Wojcik, John Nott, and Paul Craddock.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Anna Harris

Anna Harris is an Associate Professor of the Social Studies of Medicine at Maastricht University, in the Netherlands. Working at the intersections of Science and Technology Studies and Medical Anthropology, her ethnographic research largely concerns the material, sensory, and bodily nature of medical practices. More information about the broader research project which Anna leads, and which this article is situated within, Making Clinical Sense, can be found at: www.makingclinicalsense.com

References

- Bahreini, R., L. Doshmangir, and A. Imani 2019 Influential factors on medical equipment maintenance management: In search of a framework. Journal of Quality in Maintenance Engineering 25(3):128–43. doi:10.1108/JQME-11-2017-0082.

- Barley, S. R., and B.A. Bechky 1994 In the backrooms of science: The work of technicians in science labs. Work and Occupations 21(1):85–126. doi:10.1177/0730888494021001004.

- Baxandall, M. 1995 Shadows and Enlightenment. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

- Belsky, D. D. 2022 Performed with care: Enacting accuracy in medical illustration. In Making Sense of Medicine: Material Culture and the Reproduction of Medical Knowledge J. Nott and A. Harris, eds., Pp. 219–231. Bristol: Intellect Books.

- Benjamin, R. 2019 Race After Technology: Abolitionist Tools for the New Jim Code. Cambridge, UK: Polity Press.

- Bruyninckx, J. 2017 Synchronicity: Time, technicians, instruments, and invisible repair. Science, Technology, & Human Values 42(5):822–47. doi:10.1177/0162243916689137.

- Cassell, J. 1991 Expected Miracles: Surgeons at Work. Philadelphia, PA: Temple University Press.

- Cheney, I., and S. Shattuck 2020 Picture a Scientist. United States.

- Craddock, Paul. 2021 Spare Parts. London: Penguin.

- Criado-Perez, C. 2019 Invisible Women: Exposing Data Bias in a World Designed for Men. London: Chatto & Windus.

- de la Bellacasa, M. P. 2017 Matters of Care: Speculative Ethics in More than Human Worlds. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- DelVecchio Good, M. 1995 Cultural studies of biomedicine: An agenda for research. Social Science and Medicine 41(4):461–73. doi:10.1016/0277-9536(95)00008-U.

- Goldfarb, B. 2020 18 Tiny Deaths: The Untold Story of Frances Glessner Lee and the Invention of Modern Forensics. London: Endeavour.

- Goldstein, J. E. 2011 The “Coffee Doctors”: The language of taste and the rise of Rwanda’s specialty bean value. Food & Foodways 19(1–2):135–59. doi:10.1080/07409710.2011.544226.

- Guarrasi, I. 2015 Residual categories in medical simulation: The role of affect in the performance of disease. Mind, Culture, and Activity 22(2):112–28. doi:10.1080/10749039.2015.1043000.

- Hallam, E. 2013 Anatomical design: Making and using three-dimensional models of the human body. In Design Anthropology: Theory and Practice W. Gunn, T. Otto, and R. C. Smith, eds., Pp. 100–16. London: Bloomsbury Academic.

- Harris, A. 2011 In a moment of mismatch: Overseas doctors’ adjustments in new hospital environments. Sociology of Health & Illness 33(2):308–20. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9566.2010.01307.x.

- Harris, A., and T. Fuller 2014. The night-side of hospitals, places: Public scholarship on architecture, landscape, and urbanism (The design observer). http://places.designobserver.com/feature/night-side-of-hospitals-migrant-doctors/38370/.

- Harris, A., and M. Guillemin. 2021. The right doctor for the job: International medical graduates negotiating pathways to employment in Australia. Diversité Urbaine. https://www.erudit.org/en/journals/du/2020-v20-n1-du05189/1084960ar/.

- Hartley, J.M., and E.M. Tansey 2015 White coats and no trousers: Narrating the experiences of women technicians in medical laboratories, 1930–90. Notes and Records 69(1):25–36. doi:10.1098/rsnr.2014.0058.

- Hirschauer, S. 1991 The manufacture of bodies in surgery. Social Studies of Science 21(2):279–319. doi:10.1177/030631291021002005.

- Holmes, S. M., A. C. Jenks, and S. Stonington 2011 Clinical subjectivation: Anthropologies of contemporary biomedical training. Culture, Medicine and Psychiatry 35(2):105–12. doi:10.1007/s11013-011-9207-1.

- Illich, I. 1981 Shadow Work. Boston: Marion Boyars.

- Ingold, T. 2018 Anthropology and/as Education. London and New York: Routledge.

- Jackson, S. 2015. Repair. Fieldsights. https://culanth.org/fieldsights/repair, accessed September 24.

- Johnson, E. 2007 Surgical simulators and simulated surgeons: Reconstituting medical practice and practitioners in simulations. Social Studies of Science 37(4):585–608. doi:10.1177/0306312706072179.

- Jung, C. G. 2012 [1951] Aion: Researches into the Phenomenology of the Self, the Collected Works of C.G. Jung. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Kelly, A. H., and A. M. Sáez 2018 Shadowlands and dark corners: An anthropology of light and zoonosis. Medicine Anthropology Theory 5(3):21–49. doi:10.17157/mat.5.3.382.

- Latour, B. 2004 How to talk about the body? The normative dimension of science studies. Body & Society 10(2):205–29. doi:10.1177/1357034X04042943.

- MacLean, A., and A. Leibing (eds) 2007 The Shadow Side of Fieldwork: Exploring the Blurred Borders Between Ethnography and Life. Oxford and Melbourne: Blackwell Publishing.

- Martin, N., and P. Wall 2008 The secret life of medical records: A study of medical records and the people who manage them. EPIC (1):51–63. doi:10.1111/j.1559-8918.2008.tb00094.x.

- Maslen, S. 2016 Sensory work of diagnosis: A crisis of legitimacy. The Senses & Society 11(2):158–76. doi:10.1080/17458927.2016.1190065.

- Mesman, J. 2008 Uncertainty in Medical Innovation: Experienced Pioneers in Neonatal Care. Basingstoke, UK; New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Messing, K. 1998 Hospital trash: Cleaners speak of their role in disease prevention. Medical Anthropology Quarterly 12(2):168–87. doi:10.1525/maq.1998.12.2.168.

- Mody, C. C. M. 2005 The sounds of science: Listening to laboratory practice. Science, Technology & Human Values 30(2):175–98. doi:10.1177/0162243903261951.

- Morus, I. R. 2016 Invisible technicians, instrument-makers and Artisans. In A Companion to the History of Science B. V. Lightman, ed., Pp. 97–110. Chichester, UK; Malden, MA: John Wiley & Sons.

- Newlands, G. 2021 Lifting the curtain: Strategic visibility of human labour in AI-as-a-Service. Big Data & Society 8(1):1–14. doi:10.1177/20539517211016026.

- Nott, J., and A. Harris 2020 Sticky models: History as friction in obstetric education. Medicine Anthropology Theory 7(1):44–65. doi:10.17157/mat.7.1.738.

- Palfreyman, H. 2022 Material images: Flesh on paper in twentieth-century surgical drawing. In Making Sense of Medicine: Material Culture and the Reproduction of Medical Knowledge J. Nott and A. Harris, eds., Pp. 232–243. Bristol: Intellect Books.

- Plantin, J. 2018 Data cleaners for pristine datasets: Visibility and invisibility of data processors in social science. Science, Technology, & Human Values 44(1):52–73. doi:10.1177/0162243918781268.

- Prentice, R. 2013 Bodies in Formation: An Ethnography of Anatomy and Surgery Education. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

- Rapport, N. 2008 Of Orderlies and Men: Hospital Porters Achieving Wellness at Work. Durham, NC: Carolina Academic Press.

- Rice, T. 2013 Hearing and the Hospital: Sound, Listening, Knowledge and Experience. Canon Pyon, UK: Sean Kingston Publishing.

- Russell, N.C., E.M. Tansey, and P.V. Lear 2000 Missing links in the history and practice of science: Teams, technicians and technical work. History of Science xxxviii(2):237–41. doi:10.1177/007327530003800205.

- Schlegel, C., K. Flower, J. Youssef, B. Käser, and R. Kneebone 2019 Mise-en-place: Learning across disciplines. International Journal of Gastronomy and Food Science 16:100147. doi:10.1016/j.ijgfs.2019.100147.

- Shapin, S. 1989 The invisible technician. American Scientist 77(6):554–63.

- Sharp, L. A. 2011 The invisible woman: The bioaesthetics of engineered bodies. Body & Society 17(1):1–30. doi:10.1177/1357034X10394667.

- Skloot, R. 2010 The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks. London: Pan Macmillan.

- Star, S. L., and A. Strauss 1999 Layers of silence, arenas of voice: The ecology of visible and invisible work. Computer Supported Cooperative Work (CSCW) 8(1):9–30. doi:10.1023/A:1008651105359.

- Strathern, M. 2015 Outside desk-work. The Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute 21(1):244–45. doi:10.1111/1467-9655.12158.

- Street, A. 2014 Biomedicine in an Unstable Place: Infrastructure and Personhood in a Papua New Guinean Hospital. Durham and London: Duke University Press.

- Tanizaki, J. 2001 [1977] In Praise of Shadows. London: Vintage Books.

- Taylor, J. S. 2011 The moral aesthetics of simulated suffering in standardized patient performances. Culture, Medicine and Psychiatry 35(2):134–62. doi:10.1007/s11013-011-9211-5.

- Taylor, J. S., and C. Wendland 2014 The hidden curriculum in medicine’s “Culture of No Culture”. In The Hidden Curriculum in Health Profession Education F. W. Hafferty and J. F. O’Donnell, eds., Pp. 53–62. Hanover, NH: Dartmouth College Press.

- Teil, Geneviève. 1998 Devenir expert aromaticien: Y a-t-il une place pour le goût dans les goûts alimentaires? Sociologie du travail 40(4):503–22. doi:10.3406/sotra.1998.1321.

- Timmermans, S. 2003 A black technician and blue babies. Social Studies of Science 33(2):197–229. doi:10.1177/03063127030332014.

- Underman, K. 2015 Playing doctor: Simulation in medical school as affective practice. Social Science Medicine 136-137(201507):180–88.

- Underman, K. 2022 The context of touch: Gloves, materiality, and the pelvic exam. In Making Sense of Medicine: Material Culture and the Reproduction of Medical Knowledge J. Nott and A. Harris, eds., Pp. 187–193. Bristol: Intellect Books.

- Van Eijk, Marieke 2017 Insuring care: Paperwork, insurance rules, and clinical labor at a U.S. transgender clinic. Culture, Medicine & Psychiatry 41(4):590–608. doi:10.1007/s11013-017-9529-8.

- Wertheim, M., D. Henderson, and D. Taimina. 20042005. Crocheting the hyperbolic plane: An interview with David Henderson and Daina Taimina, into non-Euclidean space, with hook and yarn. Cabinet Magazine. https://www.cabinetmagazine.org/issues/16/wertheim_henderson_taimina.php.

- Whiteley, R. 2022 The Radford Collection: Exploring and experiencing the mid-nineteenth-century midwifery lecture. In Making Sense of Medicine: Material Culture and the Reproduction of Medical Knowledge J. Nott and A. Harris, eds., Pp. 245–266. Bristol: Intellect Books.

- Wyatt, S. 2022 Invisible work. In Making Sense of Medicine: Material Culture and the Reproduction of Medical Knowledge J. Nott and A. Harris, eds., Pp. 267–270. Bristol: Intellect Books.

- Wylie, C. D. 2018 Trust in technicians in paleontology laboratories. Science, Technology, & Human Values 43(2):324–48.

- Xiao, K. 2016 The taste of tea: Material, embodied knowledge and environmental history in northern Fujian, China. Journal of Material Culture 22(1):3–18.

- Young, A. 2021. MakerHEALTH. https://makerhealth.co/about/.