Abstract

By examining the Wu family’s connection with the origin of zisha teapots, this study investigates how Ming literati used material culture to shape family reputation. It unravels the complicated relationship between Ming dynasty literati and the craft products they appreciated. The paper analyzes Ming and Qing dynasty texts discussing the origins of zisha ware as well as material evidence. This study found that the authors of these texts were all connected to the Wu family. This family had success in imperial examinations but wanted to raise their social profile further via their involvement in tea and teaware production and connoisseurship. Their association with the invention of teaware — a story spread via publications by relatives and friends — conveyed the Wu family’s artistic taste. Thus, texts praising tea and tea paraphernalia as well as the exchange of tea gifts became tools for actively creating material culture and establishing influence in literati circles.

Introduction

This paper aims to deepen current understanding of Ming dynasty craft production and literatiFootnote1 participation in it via an investigation of the politically powerful Wu family and their alleged connection to the origin story of zisha teapots. Drawing upon textual analysis of Ming and Qing dynasty texts, we posit that Gong Chun, purportedly the first potter in the history of zisha ware, may be a fictional character, possibly fabricated by the Wu family. We furthermore argue that the Wu family’s deep involvement in the preparation, serving, and consumption of tea may have been motivated by a desire to elevate their societal standing during the late Ming and early Qing periods. Our study delves into Ming literati engagement in the creation, consumption, and circulation of specific forms of material culture related to tea-making, illuminating the motivations behind the desire to be associated with the invention of these crafts, particularly zisha wares.

Zisha ware is a type of unglazed tea-making stoneware that originated in sixteenth-century China and is still popular today.Footnote2 Traditionally, zisha teapots are made from a specific clay local to Yixing primarily using a slab-building technique,Footnote3 and it is claimed that they are suitable for brewing a particularly fragrant cup of tea ().Footnote4 Analysis of Ming and Qing texts, including Changwuzhi 長物志 (Treatise on Superfluous Things), Chashu 茶疏 (Commentary on Tea), Yangxian Minghuxi 陽羨茗壺系 (Yangxian Teapot Series), and Yangxian mingtaolu 陽羨名陶錄 (Record of Renowned Pots in Yangxian) indicates that zisha teapots were considered important tea-preparation implements as early as the Ming dynasty.Footnote5 Although there is reasonable doubt as to the uniqueness of the raw material and brewing behavior,Footnote6 the perceived excellence of zisha teapots in tea preparation (most scholars describe the porosity of fired zisha teapots as beneficial for producing a particular fragrant brewFootnote7), and the increasing rarity of local Yixing zisha clay have made these teapots a valuable commodity whose creation has been subject to myth making since the Ming dynasty.Footnote8

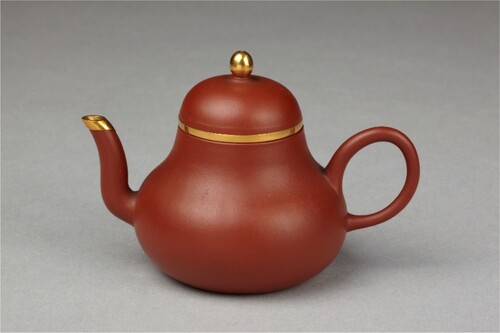

Fig. 1. Zisha teapot with a pear-shaped design, bearing Hui Mengchen (惠孟臣, a renowned potter in the Qing dynasty) inscriptions on its base. Dated from 1850 to 1900. Collection at the Victoria and Albert Museum.

The Ming dynasty was a period characterized by significant population growth, the expansion of urban networks, an increase in commodity production and exchange, prosperity in the literacy and publishing industry, and more.Footnote9 During that period, the Lower Yangtze River Plain, the specific geographic location this article focuses on, was the cultural heartland renowned for its literati culture.Footnote10

In the case of zisha teapot manufacture, some scholars consider the story of a person named Gong Chun 龔 (or 供) 春 being the first zisha potter and cultural hero to be a historical fact;Footnote11 others argue that Gong Chun may be an invented figure.Footnote12 Based on an analysis of textual sources regarding the story of Gong Chun, I argue for the likely apocryphal nature of this origin story and discuss the role of the Wu family in creating and popularizing this myth. Numerous scholars have commented on the importance of the Wu family in the popularization of zisha teapots.Footnote13 Nevertheless, most studies associating the Wu family with the start of zisha teapot manufacture in Yixing during the Ming dynasty focus on Wu Shi 吳仕 (1481–1545), the master of Gong Chun, while the present study is concerned with the Wu family as a whole and how its members endeavored, over the course of generations, to establish and improve their social standing via their involvement in the story and practice of zisha pottery making and appreciation.

Previous research has examined various aspects of visual culture and the production of artistic crafts in early modern China, including the creators, artisans, and authors of associated texts.Footnote14 These studies have addressed how consumption of art and artistic crafts has shaped elite identities in China, particularly during the Ming dynasty.Footnote15 Referring to Park’s study, this paper defines the term “elite” as a select group of individuals or entities with significant wealth, power, influence, or expertise, who often occupy privileged positions within society.Footnote16 As Brook points out, during the Ming dynasty, the elite class (composed of those who occupied a position higher than peasants, artisans, and merchants) became connoisseur consumers of “elegant things” which previously had been the purview of emperors and their courts. Rather than just wanting to possess valuable objects, they engaged in debates on aesthetics and good taste, reflecting on high cultural ideals.Footnote17 Possessing and engaging with such objects required not only financial means but also education and connections. As Park points out,Footnote18 holding an official title or academic qualifications was not enough to be considered part of the elite, but wealth, networks, and culturedness—including connoisseurship and skills in literati arts such as painting, music, or poetry—were also required. Connoisseurship in particular came to be reflected in an increasing number of manuals and other writings on the arts by literati.

Clunas argues that the eagerness of Ming dynasty literati to write about their taste in crafts and arts can be interpreted as an expression of their anxiety to preserve their literati status in society, which was challenged by the merchant class who not only accumulated increasingly more wealth but also started engaging in collecting and practicing fine arts to improve their social status.Footnote19 Stephens likewise holds that certain activities, such as playing the zither or collecting art and books, served to secure literati identity and status.Footnote20 In contrast, Wai-yee Li argues that the social landscape during the Ming dynasty was much more fluid, with notable literati coming from merchant families and individuals communicating and moving across these supposed social boundaries on a regular basis.Footnote21 Rather than anxiety about social boundaries, he concludes, the main reason may have been “personal and regional rivalries as well as assertion of individual differences.”Footnote22 Either way, these studies show that material culture appreciation and collection at the time was closely connected to social structures and inter-personal as well as intra-group interactions.

Our study enriches the existing body of research by arguing that influential Ming dynasty families, with the Wu family serving as an example, originated as commoners before gaining financial and political empowerment through imperial examinations. Over time, they crafted their family history to cultivate a social identity as literati, enabling them to assume the role of social elites. In the case of the Wu family and the origins of zisha teapots, documenting the story of the craft’s invention and connoisseurship served to increase their family’s reputation in literati circles as creators of major cultural goods, thus increasing and transcending the status already acquired by family wealth and/or success in imperial examinations. The process of building family reputation and transitioning from an average well-to-do educated family to a family that was influential in literati circles was not achieved overnight; it took several generations, as detailed below.

In the existing research, the literati, as consumers and creators, have mainly been studied or presented as individuals who acted and participated in shaping the surrounding material culture.Footnote23 The Wu family, however, is a case of several generations engaging in the creation of literati-appreciated objects and writing accounts of their family history detailing their cultural contributions.

In earlier research, the Wen family has been extensively studied, particularly in Elegant Debts by Craig Clunas.Footnote24 In this book, Clunas reconstructs the circle around artist Wen Zhengming 文征明 (1470–1559), a key member of the Wen family, known as “one of the four masters of the Great Ming.” The book discusses the roles and actions of transactions between artists, collectors, “friends” and pupils in Chinese literati arts. Although both the Wen and Wu families were active in the Lower Yangtze River Plain during the Mid to Late Ming dynasty, none of the Wen males achieved success in examinations before the seventeenth century.Footnote25 In contrast, rather than first achieving fame in the field of art and culture, the Wu family started as ordinary people and climbed the social ladder as they became politically successful via their accomplishments in the imperial examinations, as detailed in a later section. Therefore, the study of the Wu family can serve as an example for understanding the dynamics of Ming dynasty families with political backgrounds and their interactions with craft making. Unlike earlier studies on the topic, this research is not limited to Wu Shi, the supposed originator of zisha teapot making but also discusses the impact of different Wu family clan members on changes in tea fashion and the development of the family’s reputation, following the growing popularity of zisha teapots. This study thus contributes to our knowledge not only of the Wu family but also of general patterns concerning the shaping of social reputation among literati during the Ming dynasty. To achieve this two-fold aim, we discuss three Wu family members from different generations: tea practitionerFootnote26 Wu Lun 吳綸 (dates unknown), who was the father of zisha originator Wu Shi; zisha collector Wu Honghua吳洪化 (1608–48), who led the effort to rebuild the family’s reputation by celebrating zisha ware; and Wu Meiding 吳梅鼎Footnote27 (1627–99), writer of zisha poems.

The Story of the “First Zisha Potter” in Ming Dynasty Texts

The name of Gong Chun is recorded in Ming and Qing dynasty texts, including Changwuzhi, Chashu, Mingji 茗笈 (Dossier on Tea), and Chajian 茶箋 (A Note on Tea).Footnote28 Yangxian minghuxi and Yangxian minghufu 陽羨茗壺賦 (Poem about Famous Teapots in Yangxian) also include details of the invention process and note that Gong Chun was the first to create zisha teapots.Footnote29

The story of the “first zisha potter” in the Yangxian minghuxi

The Yangxian minghuxi is a monograph on zisha ware completed during the late Chongzhen reign (1611–44).Footnote30 Not much is known about the writer, Zhou Gaoqi 周高起. According to the Jiangyin xianzhi 江陰縣誌 (Jiangyin Chronicle), Zhou Gaoqi, who used the pen name Bo Gao 伯高, was killed during the late Ming rebellions.Footnote31 His book reflects on zisha teapot manufacture during the late Ming period and describes zisha production, history, potters, and connoisseurship in seven sections: Chuangshi 創始 (Initiation), Zhengshi 正始 (Official Beginnings), Dajia 大家 (Great Masters), Mingjia 名家 (Renowned Craftsmen), Yaliu 雅流 (Elegant School), Shenpin 神品 (Superb Work), and Biepai 別派 (Other Schools).

In the section on “Official Beginnings,” the author states that the teapots were first made in the Jinsha 金沙 temple, in present-day Yixing. This section describes how Gong Chun (who may have been male or female), the servant of Wu Shi (pseudonym Yishan), learned a special pottery-making technique from the monk(s) (it is unclear whether one or several individuals were involved or what their names were) and used it to make zisha teapots with Wu Shi at the Jinsha temple.Footnote32 The text reads:

供春,學憲吳頤山公青衣也。頤山讀書金沙寺中,供春於給役之暇,竊仿老僧心匠,亦淘細土摶胚。Footnote33

Gong Chun was the attendant serving the scholar Wu Yishan [Wu Shi’s pen name] in his studies. While Yishan studied in the Jinsha temple, Gong Chun secretly imitated the pottery-making technique of the old monk(s) by purifying the clay and forming the clay body during the spare time they had from their duties as a servant.

The story of the “first zisha potter” in the Yangxian minghufu

In the Yangxian minghufu, Wu Meiding describes Gong Chun as a teapot manufacturer of great intelligence.Footnote35 Wu Meiding, who lived during the late Ming and early Qing dynasties, claimed that he was a descendant of Wu Shi. His poem states that Gong Chun was an attendant serving his great-grandfather, Wu Shi, when he studied in the Nanshan 南山 region (the present-day Hufu region of Yixing), where the Jinsha temple was located:

余從祖拳石公讀書南山,攜一童子名供春,見土人以泥為缶,即澄其泥以為壺,極古秀可愛,世所稱供春壺是也。Footnote36

My great-grandfather, Quan Shi (Wu Shi), studied in Nanshan, accompanied by an attendant called Gong Chun. Gong Chun saw local people using clay for making daily wares, refining the clay to make teapots by levigating it to remove impurities. The teapots [Gong Chun made] were adorable, simple, and delicate. Thus, people called them the Gong Chun teapots.

Based on these two texts, Yangxian minghuxi and Yangxian minghufu, the official beginnings of the zisha story were supposedly as follows: Gong Chun, the servant of Wu Shi, learned pottery-making techniques while serving his master Wu Shi during his stay at Nanshan. He then proceeded to make artistic zisha pieces that came to be associated with his name. In the two texts, this story of the first zisha potter thus included two main characters: Gong Chun and his master Wu Shi.

The questionable historicity of the “first zisha potter” accounts

The story of the “first zisha potter” appears to be apocryphal for three reasons. First, Gong Chun’s name varies across Ming and Qing texts, and the literal meaning of the Chinese characters Gong Chun is likely a reference to tea practice rather than the name of a real person. Second, although there are numerous texts written by Wu Shi, none of them mention Gong Chun or the invention of zisha teapots. Third, there is no archaeological evidence for the existence of Gong Chun teapots. Below, each of these points will be argued in turn.

Two versions of Gong Chun’s name appear in textual accounts, and they have a similar pronunciation: “龔” and “供.” Wu Meiding and Wen Zhengheng 文震亨 (1585–1645) use the character “供,” while Xu Cishu 許次疏 (ca. 1549–1604), Tu Benjun 屠本畯 (1573–1620), and Wen Long 聞龍 (ca. early seventeenth century–mid/late seventeenth century) use “龔.”Footnote37 In the text Yangxian minghuxi, Zhou Gaoqi argues that Gong Chun’s surname should be “龔,” since he had found evidence that the surname of Gong Chun’s grandson was Gong “龔.”Footnote38 Furthermore, the character “龔” does appear as a surname, while the character “供” is rarely used this way.Footnote39

Furthermore, in addition to being a name, Gong Chun is also a phrase with a literal meaning. “供” can mean “to provide” or “to supply,”Footnote40 as does “龔.” The character “春” means spring.Footnote41 The combination of these two Chinese characters can be read as “providing” or “serving” spring, which can be understood as a simile for making/serving tea. The story of the “first zisha potter” may thus have been an invention; however, it could also have been the story of a real person who was given the name Gong Chun as an honorific for their outstanding contributions to tea preparation and enjoyment.

What throws more serious doubt on Gong Chun being an actual historical person is the fact that their supposed master Wu Shi, himself a literatus and prolific writer, never mentioned Gong Chun or the invention of zisha teaware in his writings. In the Yishan sigao 頤山私稿 (Private Draft from Yishan), a literary collection written by Wu Shi, no pottery making by his attendant is mentioned, nor is the manufacture or the use of unglazed pots for tea practice.Footnote42 This casts doubt on the narrative of Gong Chun inventing the zisha teapot process in the presence of Wu Shi and adds considerable weight to the theory this zisha origin story was fabricated at a later point in time.

Furthermore, no physical evidence of the existence of Gong Chun’s teapots has ever been found in the archaeological record. The National Museum of China holds a piece that has a tree gall design with the carved inscription “Gong Chun” on the bottom ().Footnote43 Chu Nanqiang 儲南強 (1876–1959) purchased this teapot at a market in Suzhou and donated it to the museum, but the provenance beyond that is unclear.Footnote44 Another teapot bearing the inscription “Gong Chun” can be found in the Hong Kong Flagstaff House Museum of Tea Ware’s K.S. Lo collection ().Footnote45 This piece has petal-shaped impressions on its body and a long spout for pouring tea. The characters “龔春” are stamped on the bottom alongside a seal. This piece, too, lacks provenance. As Gong Chun was supposedly the inventor and as early zisha ware was typically made of coarser materials with less refined production techniques and no surface decoration,Footnote46 one would expect Gong Chun’s pieces to be relatively plain and coarse, but this is not the case for either of these teapots. The items from the Chinese National Museum and the Flagstaff House Museum have very smooth surfaces and the former is decorated. It is therefore unlikely that they were manufactured as early as the period during which Gong Chun was supposedly creating teapots.Footnote47

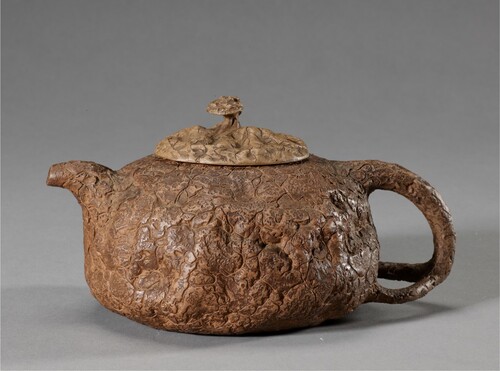

Fig. 2. Teapot with tree gall design, carrying the inscription “Gong Chun” on its bottom. Held by the National Museum of China. Image taken by the National Museum of China.

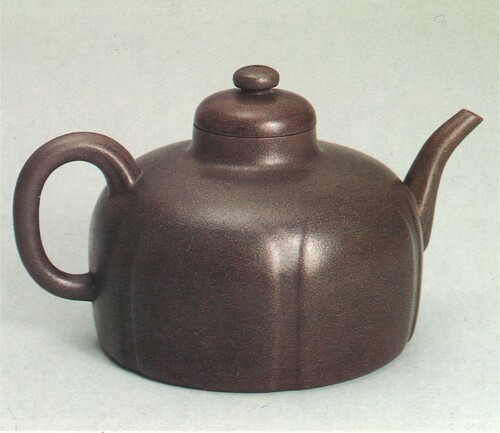

Fig. 3. Teapot with petal-shaped impressions, carrying the inscription “Gong Chun” on its bottom. Held by the Hong Kong Flagstaff House Museum of Tea Ware. Image from Lo (1986, 52). Image reproduced with the generous permission of the museum.

Alternatively, the name Gong Chun, frequently mentioned in Ming and Qing dynasty texts, could also be understood as a method for identifying and categorizing commodities to ascertain their quality and value. Craig Clunas analyzed the “names” found on objects such as bamboo carvings, jade, and ceramic wares, and determined that these names could “travel along with the object” during transactions, becoming an “index of value independent of the status of the seller or the purchaser.”Footnote48 According to this interpretation, the name Gong Chun may also serve as an indicator of craftsmanship and marketing value. On the whole, it is thus impossible to determine whether Gong Chun was an actual historical potter and maker (let alone inventor) of zisha ware. This raises the question why the texts that mention Gong Chun and credit them with the invention of zisha teapots did so. Below, it is argued that the answer to this question is closely connected with the identity of Gong Chun’s supposed master, Wu Shi.

Wu Shi and the Status of His Family

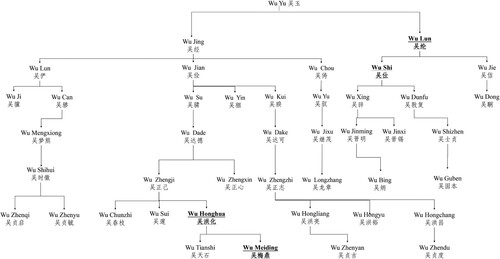

This paper highlights a small branch of the extensive Wu family related to Wu Shi, starting with Wu Yu 吳玉 (), who served as an official in the Ming court. Wu Lun was the son of Wu Yu;Footnote49 he was key in driving Ming-era tea practice and became renowned for his tea preparation skills. The elder son of Wu Lun was Wu Shi, the supposed master of Gong Chun.Footnote50

Fig. 4. Genealogical tree of part of the Wu family, concentrating on Wu Yu and his descendants (Wu 1926).

Wu Shi, the son of Wu Lun, successfully completed the highest imperial examination as Jinshi 進士 (Metropolitan Graduate, a title that guaranteed graduates civil service careers), and subsequently started his political career, serving as Anchasi Fushi Tixue 按察司副使提學 (Vice Surveillance Commissioner in Charge of Educational Affairs) in Fujian and Henan.Footnote51 This position involved inspecting provincial government schools and overseeing provincial examinations.Footnote52 Wu Shi’s success was credited to the support of his cousin, Wu Yan 吳儼, the grandson-in-law of the Ming dynasty Neige Daxueshi Shoufu 內閣大學士首輔 (Chief Counselor of Grand Secretaries), Xu Pu 徐溥 (1429–99).Footnote53 Wu Shi’s career was not an isolated case in the Wu family. Beginning with Wu Li 吳禮 (ca. fifteenth century), who took the imperial examinations in 1448, more than twenty Wu family members were successful in these exams, enabling them to serve the court as bureaucrats.Footnote54 The family owned only a moderate amount of land, and prior to Wu Yu, none of the Wu family members had an official title. Success in imperial examinations was associated not only with an honorable title but also with a position in the court and an income, which was particularly attractive for families of moderate means such as the Wu.

The Ming dynasty imperial examination system meant that political power was no longer held exclusively by aristocratic families connected by blood ties, as it had been from the Han through the Tang dynasty; people from other parts of society could also gain access to court positions.Footnote55 The expanded and consolidated Ming dynasty imperial examinations system allowed people from a range of strata in society and various levels of familial wealth to gain prestige and access to state power.Footnote56

The consistent success of Wu family members in the imperial examinations suggests that, after the first family member achieved an official position, the Wu family was able to provide the next generation with better educational opportunities which led to higher-level employment. In the late Ming period, a vigorous economy also allowed those within affluent kinship groups better access to educational resources and thus successful completion of examinations, particularly in the Lower Yangtze River Plain, where the Wu family lived.Footnote57

Nevertheless, following their successes in completing the imperial examinations, the Wu family was not content to simply enjoy their newly acquired power and fortune, but continued pursuing even better positions. A particular way of life as well as the consumption of certain items signaled an individual’s place within upper-class society.Footnote58 Tea practices and teaware developed as a way to express artistic taste and reflect leadership positions within the elite in terms of culturedness and refined taste.

Literati Connections: Wu Family Members in the Tea Circle

The Wu family’s reputation within tea circlesFootnote59 was shaped in the time of Wu Lun (1440–1522), Wu Shi’s father.Footnote60 Wu Lun’s influence on Ming tea-making methods is evident in the Ming dynasty tea manuscript Chapu 茶譜 (Tea Ledger), written by Gu Yuanqing 顧元慶 (1487–1565), who gained his tea knowledge from Wu Lun. Gu Yuanqing notes that Wu Lun pursued tea making and tea tasting with great fervor.Footnote61 Moreover, for Wu Lun, tea was a medium for building and consolidating friendships with other members of the literati circle. In response to Wu Lun sending him tea, Wen Zhengming wrote a poem to express his gratitude for the gift, and another poem to detail his subsequent tasting experience.Footnote62 By gifting fine tea, When Zhengming, one of the “Four Masters” of the Ming dynasty, and Wu Lun forged a friendship. Their shared passion for tea solidified this friendship.Footnote63 Similarly, when Wu Lun sent tea to Shao Bao 邵寶, Shao also wrote two poems to express his gratitude.Footnote64 Shao Bao lived in Wuxi, while Wen Zhengming was active in Suzhou. Although gift-giving, connoisseurship, economic transactions, and power exchanges were highly intricate aspects of literati social lives during the Ming dynasty, as detailed in Elegant Debts, in the case of Wu Lun, tea and tea connoisseurship were pivotal in establishing and nurturing relationships between Wu Lun and the literati of the Lower Yangtze region.Footnote65 Other experts who practiced tea ceremonies, such as Wang Dezhao 王德昭 and Wang Yongzhao 王用昭,Footnote66 also visited Yixing. The friendship between Wang Yongzhao, a well-known tea practitioner, and Wu Lun’s son Wu Shi, is clearly reflected in Wu Shi’s writing.Footnote67 Both father and son thus used tea as a medium for building social networks across the Lower Yangtze Plain.

Wu Lun’s achievements in tea circles must be considered within the context of changes in tea-making methods in Chinese history. During the Ming dynasty, significant transformations occurred in tea-consumption methods, which shifted from the use of powdered tea to the prevalence of brewed loose-leaf tea. The Tang and Song dynasty tea cakes were meticulously ground into a fine powder and often combined with various additives to enhance flavor.Footnote68 Archaeological evidence, such as Tang dynasty tea grinders and tea sieves excavated from the Famensi 法門寺 (Famen temple) site, evince the consumption of powdered tea.Footnote69 The tea powder was sieved and then mixed with boiling water to create a concentrated tea “soup,” which was traditionally served to consumers in tea bowls.Footnote70 During the Song dynasty, a new tea-consumption method was introduced, known as diancha 點茶; it involved the ritualistic pouring of boiling water directly onto the blended tea powder in the tea bowl.Footnote71 During the Ming dynasty, the Hongwu Emperor (1368–98) changed the tribute tea policy: he banned tea cakes and ordered loose-leaf tea sent to the court as tribute instead.Footnote72 The official preference for loose-leaf tea within the court accelerated its spread in Ming society. These distinct tea forms, tea powder and loose tea, required different containers and different tea practices. Thus, Wu Lun’s tea practices are particularly important in the context of the transition of teawares and the exploration of the “new” tea practices and teawares of the Ming era.

The natural resources of Yixing, including tea and raw material to make teawares, enabled the Wu family to take on a leading role in tea practice. The tea in Yixing, known as Yangxian 陽羨tea, has a history that goes back at least to the eighth century. Lu Yu, the author of the Chajing 茶經 (Classic of Tea), lauded Yangxian tea as the best tea available during the early Tang period.Footnote73 Every year, an imperial envoy investigated the quality of the teas and dispatched the best among them to the court. This annual Yangxian tea tribute constitutes the origin of tribute tea.Footnote74 At the end of the eighth century, more than 30,000 people had come to be part of this elaborate tea tribute system by picking and firing tea leaves. Lu Tong 盧仝 (795–835) wrote a poem mentioning how “the spring flowers dare not open, as the emperor still awaits the annual toll of Yangxian tea.”Footnote75 This is a reference to the emperor’s obsession with Yangxian tea. As the best tea was required for the court, Tang officials established a tribute tea factory in the region of Guzhu Mountain, on the northern boundary of Zhejiang province, which produced zisun 紫筍 (purple shoots) tea. Because it was appreciated by the elites at court for its taste and the cultural events surrounding it, officials dispatched the tea and items needed for its preparation (including zisha teaware) in large quantities to the capital.Footnote76

Because he was from Yixing which was and still is in an important tea-growing region, Wu Lun had direct access to the high-quality tea which he would send to friends and acquaintances as gifts. His status and location in Yixing may also have rendered Wu Lun’s views on tea and his preferences in terms of tea-consumption methods and paraphernalia definitive among literati living in the Lower Yangtze Plain. As previously noted, Wen Zhengming and Shao Bao were sent high-quality tea on behalf of Wu Lun. This tea had likely been produced in Yixing, based on the renown of the locally grown tribute tea. Sending this high-quality tea as a present to other literati helped Wu Lun reinforce his social networks. Accordingly, high-quality tea and Wu Lun were intimately linked in literati circles. Wu Lun, a local tea expert on tribute tea sent to the emperor, was likely influential in shaping practices and trends and stimulated a preference for Yixing tea.

Though Wu Lun and his son Wu Shi were active in the tea circles of the Lower Yangtze Plain, this does not prove that the invention of zisha teapot by Wu Shi’s attendant Gong Chun was a historical fact, but it provides some background for understanding how this story came about. To better assess the reason the zisha origin story in the Yangxian minghufu and Yangxian minghuxi was written, the background of the authors of these two texts must be examined in detail.

The Authors of the Zisha Origin Story: Publications as Tools

Numerous texts telling the story of the origins of zisha were produced by or inspired by Wu family members. Wu Meiding, the son of Wu Honghua, a member of the Wu family and teapot collector, composed a poem describing the origins of zisha. When Zhou Gaoqi stayed with Wu Honghua, he was inspired to write his zisha monograph that mentioned Gong Chun. According to the Yangxian minghuxi, Zhou Gaoqi visited Wu Honghua to see his zisha teapot collection, and then memorialized the visit in a poem.Footnote77 The poem shows the friendship between collector Wu Honghua and Zhou Gaoqi. Furthermore, Zhou praises Wu’s taste in art and his collection. Although there is no direct evidence to suggest the Wu family sponsored Zhou’s writing of the Yangxian minghuxi, the Wu family’s taste in zisha teapots clearly impressed Zhou and is mentioned in his writing. He writes:

羈愁共語賴吳郎,曲巷通人每相喚 … 吳郎鑒器有淵心,曾聽壺工能事判。源流裁別字字矜Footnote78

The sorrow of leaving one’s hometown is driven away by communication with Mr. Wu. This gentleman always asked me to come over to his place when he passed by the alley, I stayed … Mr. Wu is knowledgeable and a connoisseur of art pieces. He has assessed the quality of a teapot based on his knowledge of the techniques used for making teapots. Mr. Wu’s every word is accurate regarding the sources of origin and difference in craftsmanship of teapots.

The zisha monograph, Yangxian minghuxi, thus not only mentioned but bolstered the link between the first zisha pots and the Wu family via the story of Gong Chun and the expertise on teawares of Wu family members. Wu Honghua may have played a critical role in shaping Zhou Gaoqi’s knowledge of teapot connoisseurship and the history of zisha. The monograph, in this way, served to disseminate information about the Wu family and its connection to zisha ware.

Another text that included the zisha origin story mentioned above was written by Wu Meiding, the son of Wu Honghua. Little is known about the author. According to the Yijin wushi zongpu 宜荊吳氏宗譜 (Genealogy of the Yijing Wu Family), he was an expert in poetry and calligraphy. In the Yangxian minghufu, Wu Meiding also mentions that his family collection had been ruined by war. The description of his experience living through the unstable situation of war implies that Wu Meiding was grieving the former glory of his family. He writes:

先子以蕃公嗜之, 所藏頗夥,乃以甲乙兵燹,盡歸瓦礫,精者不堅,良足歎也 … … 爰有供春侍我從祖 … … Footnote79

My late ancestor Lord Yifan was very fond of his [zisha teapot] collection, which is rather rich. However, when soldiers and warfare come, all stoneware is reduced to sherds. The finest ware is not solid; this is enough to make one sigh … previously Gong Chun served by great-grand father … .

Yijin wushi zongpu (two volumes) was compiled and published in 1926, during the fifteen-year Republican period. Jimeitang (济美堂), appearing on each page of it, is the name of the Wu family shrine and also denotes a later branch of the Wu family in Yixing which shares the same family shrine. Thus, the Wu family genealogy was most likely privately printed by the family. The preface of the Yijin wushi zongpu mentions that the aims of this publication were to record Wu family social achievements, to demonstrate their loyalty to the court, and to show filial piety toward older family members. Presumably, the intended audience was future generations of the Wu family.Footnote84

The earliest preserved version of the Yangxian minghuxi is included in the Tanji congshu 檀幾叢書, which was printed in the thirty-sixth year of Kangxi (1697), by Wang Zhuo 王晫 (1636–1705) and Zhang Chao 張潮 (1650–1707). So far, no records or information regarding any versions of the Yangxian Minghuxi earlier than the Yanji congshu 檀幾叢書 version have been found.Footnote85

Kinship, Valuable Crafts, and Social Identity

The above discussion of Wu family members Wu Lun, Wu Shi, Wu Honghua, and Wu Hongyu makes it clear that although they represent different generations, they all contributed to connecting their family history to the creation of zisha ware. This raises the question why they continuously made efforts to build their family history in this way and make it known via their social connections and via publications.

During the Ming and Qing dynasties, the power of kinship played a critical role in establishing and maintaining personal social status.Footnote86 Kinship in this period can be described as arranged around lineages connecting the male family lines, which functioned in social networks through the sharing of resources to strive for social space.Footnote87 Kinship was important because it provided a means of preserving property and social status.Footnote88 As noted by Freedman, “In the first place, the glory of one party determined that of the other. The virtues of ancestors descended to their offspring who could cast honor back upon their name.”Footnote89 The kinship and the ties of lineage in Chinese families also enabled the transition of virtues and merits from the dead to the living and from ancestors to later descendants.

Families, considered the foundation of the state, played a critical role in ensuring political stability and social harmony during the Ming dynasty.Footnote90 This principle was emphasized and strengthened through intellectual endeavors, notably the compilation of clan and family genealogies. The reconstitution of family histories bolstered solidarity among relatives by reminding them of their shared lineage. On the one hand, family genealogies motivated and instilled pride in younger members by celebrating the virtues of their ancestors.Footnote91 On the other hand, the reinforcement of family clans through genealogies also yielded practical social benefits, facilitating socialization among clan members and fostering morally binding connections between affluent and less privileged relatives.Footnote92 Consequently, at the societal level, Ming intellectuals greatly valued family history, recognizing it as a vital component for sustaining local social stability.

The shaping of the literati family image on the local level is intertwined with the regional development of cultural and intellectual history, particularly through the compilation of local gazetteers.Footnote93 Joseph R. Dennis, in an analysis of the Chinese gazetteer, explains that the portrayal of local literati families in regional documentation not only promotes the acceptance and practice of prevailing Confucian literati values but also contributes to the formation of a collective identity within the local social unit. In this context, the cultivation of family reputation practiced by the Wu family, which was recognized in local gazetteers as a literati family because of its members’ political and literary accomplishments, further enriched the local intellectual history and fortified the collective identity of the community.

In the case of the Wu family, the claiming of Wu Shi and his influence on the development of zisha allowed his descendants to share his honor, associated with the creation of literati-favored zisha teapots. The desire to claim to have had a major hand in the invention of zisha is also associated with the increasing commercial value of zisha teapots in the late Ming period. The success of zisha ware was reflected in its price, which was high compared to the price of other ceramic items, especially for pieces by the renowned potters of the Ming dynasty. The text Tao’an mengyi 陶庵夢憶 (Dream Reminiscence of Tao’an) provides a clear price range for ceramics produced in Jingdezhen and Yixing. Li Rihua (1565–1635) ordered 50 cups from a famous Jingdezhen potter and paid three ounces of silver (0.085 kilograms per cup); Zhang Dai (1597–1684) noted his red stoneware teapot from Yixing cost 5–6 ounces (0.14–0.17 kilograms) of silver.Footnote94 The Qing dynasty text Chashi 茶史 (History of Tea) notes that a rare teapot made by Gong Chun and Shi Dabin was worth twenty thousand to thirty thousand coins.Footnote95 Meanwhile, zisha teapots from famous artisans became desirable items for the literati and collectors. Wen Long, in Chajian 茶笺 (Notes on Tea), notes that teapot enthusiast Zhou Wenfu 周文甫 treasured his Gong Chun teapot and had it buried with him in his tomb.Footnote96 He writes:

嘗畜一龔春壺,摩挲寶愛,不啻掌珠,用之既久,外類紫玉,內如碧雲,真奇物也。後以殉葬。Footnote97

He [Zhou Wenfu] owned a Gong Chun teapot and treasured it like a pearl in his palm[s]. After it had been used for a long time, the outside became like purple jade and the inside like a green–blue cloud when brewing tea. It was a truly remarkable object. Later on, it was buried with him.

The creation and circulation of craft items, in this case ceramic teapots, at considerable prices and surrounded by debates on their artistic value among a certain part of society, indicate artistic taste and are associated with social class. Socially distinguishable art forms, periods, and schools always correspond to the social hierarchy of their consumers, and the taste of these artistic objects functions as a symbol of class.Footnote98

According to French sociologist Pierre Bourdieu, each “class fraction [is] characterized by a certain configuration of this distribution to which there corresponds a certain life-style, through the mediation of the habitus.”Footnote99 In 1979, Bourdieu presented his theories about social stratification and aesthetic taste in the book Distinction: A Social Critique of the Judgement of Taste, which expanded the concept beyond cultural tastes to encompass the processes by which these preferences emerge and become entangled in contests for social recognition or status.Footnote100 In 1899, the term “conspicuous consumption” was introduced by sociologist Thorstein Veblen to describe the expenditure of money on luxury goods and services, primarily as a public demonstration of the economic prowess—in terms of both income and accumulated wealth—of the purchaser. Conspicuous consumption is evidence of financial superiority and, at the same time, the selective process reflects previously established habits or thoughts.Footnote101 It is noteworthy that both Bourdieu and Thorstein were twentieth-century scholars whose research predominantly focused on analyzing modern societies, and who paid particular attention to their respective home countries, France and the United States. However, their studies and theories on consumption, taste, and social structures remain essential for understanding the societal-level consumption of luxury goods.

Considering the considerable price of teawares, which were considered luxury items during the Ming dynasty, these sociological theories offer a new perspective for understanding the use and consumption of Yixing wares on a social level, particularly as a symbol of social identity. Because tea reflected taste and general cultural refinement in literati circles and helped to denote social class and social identity, the Wu family’s efforts in building taste and a way of life in the literati circles likely served the purpose of building and reinforcing their social status. As previously described, the Wu family accumulated its political and financial strength through imperial examinations, but that was not enough to gain and maintain social status in the wider sense. They neither were part of the upper class nor had elite status simply by being successful in the imperial examinations, as those were only part of the story. To further build their reputation and weight in society, they established themselves as tea and teaware connoisseurs, eventually becoming leaders in these trends. The creation of zisha origin texts was a means of reinforcing their social status.

Discussion and Conclusion

This case study examines the process involved in building family reputation through the creation of connoisseurship and origin stories surrounding tea and teawares as reflected in textual records from Ming dynasty China. The Wu family transitioned from common people to a family with political power through their sustained success in the imperial civil examinations. Consistent success in imperial examinations permitted a political career and financial security, but to achieve truly elevated social status, more was needed. Locally produced fine tea became a vehicle for building social networks and created a new type of tea practice in the era of Wu Lun and Wu Shi, as indicated in letters and poems shared between them and their contemporaneous literati friends.

Although the credibility of the “first zisha potter” records is questionable, Wu Shi was successfully associated with the creation of zisha teapots. As the master of the “first zisha potter” recorded in the texts, Yangxian minghuxi and Yangxian minghufu, Wu Shi played an important role, having been involved in the invention of zisha teapots. The authors of these records, Zhou Gaoqi and Wu Meiding, either were descendants of Wu Shi or maintained close relations with his descendants. Zhou Gaoqi delivered a poem addressing the inspiration provided by Wu Hongyu and Wu Honghua, who showed him their teapot collections. Wu Meiding also wrote a poem that mentioned Wu Shi and the origins of zisha production, intended to highlight the ancestral endeavors in pottery creation. All these links between text contributors and the Wu family indicate that Wu family members played an active role in the writing of these texts containing the zisha origin story, building connections between zisha ware and their family’s reputation.

The Wu family was empowered by the imperial examinations, acquiring a certain social status by serving the court. More than twenty Wu family members served the royal family, which indubitably provided the family with fortune and power. Nevertheless, their political success was not the end of their efforts, but rather an opportunity for reframing their family reputation. Their final objective was to build and consolidate the family’s social status through reforming their family history by associating it with the creation of zisha teapots. The prosperity of the publishing industry during the late Ming dynasty offered them a chance to build family history through texts. The process of building family reputation took efforts by generations of Wu family members.

Future research into the “events” and “history” related to craft production is needed to determine whether certain content on textual sources was intentionally fabricated by the literati and thus does not represent historical truths. When examining texts concerning material culture, contextualization is vital; analysis of the authors’ intentions and the motivations behind writing these texts is especially important. Investigating these texts within their historical and social context provides insights into the motivations and aspirations of the authors. By questioning the underlying reasons for the creation of these narratives, we can gain a deeper understanding of the political, social, and cultural agendas that influenced them. This analytical process not only enriches our understanding of historical events but also serves as a caution against the uncritical acceptance of texts as absolute truth.

The proliferation of printed materials facilitated the dissemination of narratives, effectively linking writers to the cultural events they described. It suggests that literary production was not a solitary act of creation; rather, it was intricately intertwined with the cultural landscape of the time. Focusing on this connection provides a fresh lens through which to interpret preserved texts, illuminating how they were both products and shapers of their cultural milieu.

The analysis of the zisha origin story reveals that the motives behind the extensive documentation of objects during the Ming dynasty are considerably more complex than previously recognized. They extend beyond shaping social identity and expressing personal taste and they encompass a range of factors, including social mobility facilitated by the civil examination system, the flourishing publication industry, and the concept of kinship within Chinese society. All these elements need to be considered in future studies that evaluate the documentation of objects in Ming and Qing dynasty literature.

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s) .

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Xuyang Gao

Xuyang Gao is a DPhil candidate at the School of Archaeology, University of Oxford. She holds a bachelor’s degree from the Central Academy of Fine Arts in Beijing and a master’s degree from UCL. She is a trained potter from a family of zisha ware makers. Her main research interests are ceramic making in seventeenth- through nineteenth-century China, ceramic culture and crafting for Ming and Qing dynasty elites. Her book chapter, co-authored with Dr Anke Hein, was published in the book Understanding Authenticity in Chinese Cultural Heritage.

Anke Hein

Anke Hein is an Associate Professor in Chinese Archaeology at the University of Oxford and St Hugh’s College. She is an anthropological archaeologist focusing on issues of culture contact, identity formation, and expression, in particular via the lens of ceramic technology. She also conducts research on the history and practice of archaeology as a discipline.

Notes

1 In this study, the term “literati” transcends its traditional association with holders of imperial examination degrees. Following Craig Clunas, it encompasses a group that not only intersects with the social elite but is also characterized by shared aesthetic, moral, and intellectual interests across various dimensions of material culture, united by a common engagement in literati culture. Clunas, Superfluous Things, 72; Wu, Zhihe 吳智和, “Mingdai charen de chaliao yijiang 明代茶人的茶寮意匠,” 15–23.

2 Hang, Tao 杭濤 and Ma Yongqiang 馬永強, “Yixing shushan yaozhi de fajue 宜興蜀山窯址的發掘,” 44–51.

3 Kerr and Wood, Ceramic Technology, 275–77.

4 Han, Renjie 韓人傑 et al., Gao Haigeng 高海庚, “Yixing zishatao de shengchan gongyi tedian he xianwei jiegou 宜興紫砂陶的生產工藝特點和顯微結構,” 26–35.

5 Wu, Qian 吳騫, Yangxian mingtaolu 陽羨名陶錄 (Record of Renowned Pots in Yangxian); Zhou, Gaoqi 周高起, Yangxian minghuxi 陽羨茗壺系 (Yangxian Teapot Series).

6 Gao, Xuyang, “Unravelling the Complex Meanings.”

7 A series of laboratory experiments have argued that there was a positive correlation between the porosity of fired zisha and the flavor of tea brewed in these pots. However, author Gao, in their 2023 DPhil thesis, challenged prior research on the porosity of zisha teapots, utilizing scanning electron microscopy results, and questioned the standards of “good tea” employed in earlier studies. Previous studies: Han, Renjie 韓人傑 et al., “Yixing zishatao de shengchan gongyi tedian he xianwei jiegou 宜興紫砂陶的生產工藝特點和顯微結構,” 26–35; He, Panfa 賀盤發, “Yixing zishani zongshu 宜興紫砂泥綜述,” 30–38; Sun, Jin 孫荊, and Ruan Meilin 阮美玲, “Yixing zishatao de xianweijiegou he zishaqi de touqixing 宜興紫砂陶的顯微結構和紫砂器的透氣,” 21–25.

8 Gao and Hein. “The Authenticity Problem,” 171–85.

9 Mote and Twitchett, The Cambridge History of China, 1.

10 Chen, “Ming Dynasty Literati: Differentiation and Analysis,” 187–218. In this paper, we adopt the transliteration “Gong Chun” for the characters 龔 (or 供) 春, found in Ming and Qing dynasty texts. This decision is based on two considerations: firstly, our discussion centers on the earliest zisha monograph, Yangxin Minghuxi, which portrays Gong Chun as a servant with the surname Gong 龔. Following this interpretation, we translate 龔 (or 供) 春 as Gong Chun. Secondly, for consistency and readability, we consistently use the name “Gong Chun” throughout the manuscript — although, later in this article, we explore the possibility that Gong Chun might be a fictional entity, suggesting that 龔 (or 供) 春 may not denote a real historical figure.

11 Gu, Jingzhou 顧景舟 et al., Yixing zisha zhenshang 宜興紫砂珍賞, 13–14; Hong Kong Museum of Art, The Art of the Yixing Potter, 44; Lo, Kwee-seong, “Patronage and Its Influence,” 11.

12 Jiang, Jun 蔣君, “Zhongguo diyipian zanmei zisha jiafu de zuozhe — Wu Meiding yu yixing zisha 中國第一篇讚美紫砂佳賦得作者 — 吳梅鼎與宜興紫砂,” 203–11; Zhan, Zhijie 戰志傑, “‘Gongchun’ kaobian ‘供春’考辨,” 41–43.

13 He, Yue 何嶽, “Gongchun: yige chuanqi yihuo ‘yangmou’ 供春:一個傳奇抑或‘陽謀’,” 77–84; Hu, Jing 胡婧, “Ming Zhongqi Yixing Jimeitang Wushi Yanjiu 明中期宜興濟美堂吳氏研,” 43–48; Jiang, Jun 蔣君, “Zhongguo diyipian zanmei zisha jiafu de zuozhe — Wu Meiding yu yixing zisha,” 203–11; Jiang, Jun 蔣君. “Zhongguo zisha taogong shishang jizai de diyige mingzi — zishahu bizu Gongchun 中國紫砂陶工史上記載得第一個名字 — 紫砂壺鼻祖供春,” 181–90; Yang, Zhenya 楊振亞, “Guanyu gongchunhu de jige wenti 關於供春壺的幾個問題,” 35–38; Zhan, Zhijie 戰志傑, “‘Gongchun’ kaobian ‘供春’考辨,” 41–43.

14 Clunas, Pictures and Visuality; Clunas, Superfluous Things; Ko, The Social Life of Inkstones.

15 Brook, The Troubled Empire; Park, Art by the Book.

16 Park, Art by the Book, 3.

17 Brook, Troubled Empire, 193.

18 Park, Art by the Book, 14.

19 Clunas, Superfluous Things, 163.

20 Stephens, “Boundaries, Names, Texts, and a Bamboo Cap,” 51.

21 Li, The Promise and Peril of Things, 99–103.

22 Li, The Promise and Peril of Things, 103.

23 Clunas, Superfluous Things; McNair, The Upright Brush.

24 Clunas, Elegant Debts.

25 Clunas, Elegant Debts, 19.

26 In this article, the term “tea practitioners” is used to describe individuals who were deeply involved with or passionate about tea culture and the art of tea. The term refers to more than just a habit of drinking tea; it also encompasses cultural and aesthetic dimensions associated with tea drinking. It reflects a broader appreciation of various aspects of tea, including its history, cultivation, preparation, and the different types and varieties. The Chinese equivalent of the term would be “茶人.”

27 Wu Meiding 吳梅鼎 (1627–99), whose style name is Tianzhuan 天篆 and whose courtesy name is Fuyue 浮月, was the son of Wu Honghua 吳洪化. He earned the lingongsheng (廩貢生, who obtain the status of a provincial degree called gongsheng 貢生 through donation) degree in the imperial examinations. As per the family genealogy, Yijin wushi zongpu, he is recognized for his poetry, calligraphy, and paintings.

28 Tu, Benjun 屠本畯, “Mingji 茗笈 (Dossier on Tea),” 332–44; Wen, Zhenghen 文震亨, Changwuzhi jiqita liangzhong 長物志及其他兩種 (Treatise on Superfluous Things and other Two); Wen, Long 聞龍, “Cha Jian茶箋 (A Note on Tea),” 410–12; Xu, Cishu 許次紓, “Chashu 茶疏 (Commentary on Tea),” 257–65.

29 Wu, Qian 吳騫, Yangxian mingtaolu 陽羨名陶錄 (Record of Renowned Pots in Yangxian); Zhou, Gaoqi 周高起, Yangxian minghuxi 陽羨茗壺系 (Yangxian Teapot Series).

30 Li, Minxing 李敏行, “Yangxian minghuxi zhi kaozheng 陽羨茗壺系 之考證,” 68–73.

31 Gong, Zhiyi 龔之怡, “Jiangyin Xianzhi 江陰縣誌 (Jiangyin Chronicle),” 210. According to the book The Troubled Empire, the late Ming rebellions were a series of rebellions that took place when the Ming dynasty underwent a decline as it faced economic difficulties, corruption, natural disasters, famine, and external threats on the northern border. The two most notable rebellions were the one led by Li Zhicheng 李自成 (1606–45) and the one led by Zhang Xianzhong 張獻忠 (1606–47). Li crowned himself in Xian 西安 in 1644, while Zhang proclaimed himself the “The King of Great West” 大西王 in Sichuan province in 1643; Brook, Troubled Empire, 252–55.

32 Zhou, Gaoqi 周高起, Yangxian minghuxi 陽羨茗壺系 (Yangxian Teapot Series).

33 Zhou, Gaoqi 周高起, Yangxian minghuxi 陽羨茗壺系 (Yangxian Teapot Series), 2.

34 Wu, Hongyu 吳洪裕 (1598–1650) with courtesy name Wenqing 問卿. According to Zhou Gaoqi’s Yangxian minghuxi, he saw a Gong Chun teapot in Wu Hongyu’s collection. Wu Hongyu, originally from present-day Yixing, held the title of Juren after passing the imperial examination. He was also a well-known art collector and owned the renowned painting Fuchun shanjutu 富春山居图 (Dwelling in the Fuchun Mountains).

35 Wu Meiding 吳梅鼎, “Yangxian minghufu 陽羨茗壺賦 (Poem about Famous Teapots in Yangxian),” 880–81.

36 Wu Meiding 吳梅鼎, “Yangxian minghufu 陽羨茗壺賦 (Poem about Famous Teapots in Yangxian),” 880.

37 Tu, Benjun 屠本畯, “Mingji 茗笈 (Dossier on Tea),” 332–44; Wen Zhenghen 文震亨, Changwuzhi jiqita liangzhong 長物志及其他兩種 (Treatise on Superfluous Things and other Two); Wen Long 聞龍, “Cha Jian 茶箋 (A Note on Tea),”; Wu, Meiding 吳梅鼎, “Yangxian minghufu 陽羨茗壺賦 (Poem about Famous Teapots in Yangxian)”; Xu, Cishu 許次紓, “Chashu茶疏 (Commentary on Tea),” 267–78.

38 Zhou, Gaoqi 周高起, Yangxian minghuxi 陽羨茗壺系 (Yangxian Teapot Series).

39 Hu, Zhen 胡真, Baijiaxing 百家姓, 97.

40 Wang, Li 王力, Cen Qixiang 岑麒祥, and Lin Taoyuan 林燾原, Guhanyu changyongzi zidian 古漢語常用字字典, 125.

41 Kroll, A Student’s Dictionary, 62.

42 Wu, Shi吳仕, Yishan sigao 頤山私稿 (Private Draft from Yishan).

43 National Museum of China 中國國家博物館, Gong Chun zishahu 供春紫砂壺.

44 Yao, Minsu 姚敏蘇, “Cong ‘zini xinpin’ shuodao ‘gongchunhu’ 從‘紫泥新品’說到‘供春壺’,” 103–04.

45 Lo, “Patronage and Its Influence on Yixing Teapots,” 52.

46 Gao, “Unravelling the Complex Meanings.”

47 Zhu, Yunfeng 朱雲峰, Liu Liming 劉李明, and Zhou Wei 周瑋, “Dui zishahu qiyuan zhizheng de bianxi 對紫砂壺起源之爭的辨析,” 63–69.

48 Clunas, Superfluous Things, 63–71.

49 Wu, Chengyi 吳誠一, Yijin wushi zongpu 宜荊吳氏宗譜 (Genealogy of the Yijing Wu Family). Wu Yu became the Nanjing Guozijian student (南京國子監生; students who were enrolled in the Guozijian of Nanjing.) The Guozijian, often translated as the Imperial Academy or Imperial College, was the national central institute of learning in ancient Chinese dynasties.

50 Zhou, Gaoqi 周高起, Yangxian minghuxi 陽羨茗壺系 (Yangxian Teapot Series).

51 Hu, Jing 胡婧, “Ming zhongqi Yixing jimeitang wushi yanjiu 明中期宜興濟美堂吳氏研究,” 23–32.

52 Wilkinson, Chinese History: A Manual, 261.

53 Hu, Jing 胡婧, “Ming zhongqi Yixing jimeitang wushi yanjiu 明中期宜興濟美堂吳氏研究,” 26.

54 Cui, Laiting 崔來廷, Mingqing jiake shijia yanjiu 明清甲科世家研究, 396–400. Wu Li (1411–unknown) was born in Yixing and obtained a Jinshi degree. He passed the imperial examination in 1448 and became an official in the Nanjing hubu 南京戶部 (Department of Revenue in Nanjing). He was subsequently promoted and served as Taizi taifu 太子太傅 (Grand Mentor to the Crown Prince), and eventually attained the position of Jianjidian daxueshu 建極殿大學士 (Grand Secretary of the Hall of Jianji).

55 Ebrey, The Aristocratic Families, 3; Qin, and Kung, “Social Mobility in Late Imperial China,” 628–61. Tackett, The Destruction of the Medieval Chinese Aristocracy.

56 Elman, A Cultural History, 147–53.

57 Elman, “Political, Social, and Cultural Reproduction,” 7–28.

58 Ebrey, Aristocratic Families, 1; Gronow, The Sociology of Taste, 20–21.

59 The tea circles mentioned in this study involved individuals who were passionate about tea; they often possessed extensive knowledge about various types of tea, tea culture, and tea ceremonies, and they may have engaged in activities related to the production, preparation, and appreciation of tea, as well as the promotion of tea culture. According to Wu Zhihe 吳智和’s article, Zhongming caren jituan de yincha xingling shenghuo 中明茶人集團的飲茶性靈生活, Ming dynasty tea circles mainly consisted of educated literati who could afford tea and enjoyed a lifestyle of leisure. Tea practices and connoisseurship were among their interests and the theme of their social gatherings; Wu Zhihe 吳智和, “Zhongming caren jituan de yincha xingling shenghuo 中明茶人集團的飲茶性靈生活,” 52–63.

60 Chen, Lin Wei 陳遴瑋 and Wang Sheng 王升, “Chongxiu Yixing xianzhi 重修宜興縣誌 (Revised Chronicles of Yixing County).”

61 Gu, Yuanqing 顧元慶 and Qian Chunnian 錢椿年, “Chapu 茶譜 (Tea Ledger),” 197.

62 Wen, Zhengming 文征明, “Xie Yixing Wudaben jicha 謝宜興吳大本寄茶 (Thanking Yixing’s Wu Daben for Sending Tea),” 178.

63 Clunas, Elegant Debts, 7.

64 Shao, Bao 邵寶, Rongchutang ji 容春堂集 (Rongchun Hall Collection), 1258–413.

65 Clunas, Elegant Debts.

66 Few known records include dates or biographical information regarding Wang Dezhao 王德昭 or Wang Yongzha 王用昭. It is clear from a few preserved poems that these individuals were known for their tea-making skills and that they maintained friendships with Wu Shi. Wen Zhengming 文征明 wrote a poem titled Yangchenghui Yixing Wang Dezhao wei peng yangxiancha 相城會宜興王德昭為烹陽羨茶 (The Xiangcheng gathering invited Wang Dezhao from Yixing to brew Yangxian tea), which describes Wen Zhengming 文征明 meeting Wang Dezhao 王德昭 and the two having tea together. In this poem, Wen highly praised Wang’s tea-making skills. Wang Yongzhao maintained a close friendship with Wu Shi; this is made clear in Ji Wangshuishi wen 祭王水石文 (A lament for Wang Shuishi), a mourning article Wu Shi wrote to commemorate his friendship with Wang Yongzhao.

67 Wu, Shi吳仕, Yishan sigao 頤山私稿 (Private Draft from Yishan), 772–73.

68 Benn, Tea in China: A Religious and Cultural History, 112; Hinsch, The Rise of Tea Culture in China: The Invention of The Individual, 22.

69 Shanxisheng Kaogu Yanjiusuo 陝西省考古研究所 et al., Famensi kaogu Fajuebaogao 法門寺考古發掘報告.

70 Liao, Baoxiu 廖寶秀, Lidai chaqi yu chashi 歷代茶器與茶事, 7–8.

71 Cai, Xiang 蔡襄, Chalu ji qita jizhong 茶錄及其他幾種 (Record of Tea and Several Others); Yang, Zhishui 楊之水, Hunshi louji juanliu liangsong chashi 棔柿樓集 卷六 兩宋茶事, 33–37.

72 Lü, Weixin 呂維新, Qian Kaixin 錢開信, and Wang Xuejin 王學進, “Ping mingtaizu ‘bazaolongtuan’ 評明太祖 ‘罷造龍團,’” 126–28.

73 Hinsch, The Rise of Tea Culture in China, 40; Lu, The Classic of Tea.

74 Blofeld, The Chinese Art of Tea. 9.

75 Lu, Tong 盧仝, “Zhoubi Xie Mengjian Yijixincha 走筆謝孟諫議寄新茶 (A Hastily Written Thank You Note to Advisor Meng Jian for Sending New Tea),” 4379.

76 Hinsch, The Rise of Tea Culture, 40.

77 Zhou, Gaoqi 周高起, Yangxian minghuxi 陽羨茗壺系 (Yangxian Teapot Series).

78 Zhou, Gaoqi 周高起, Yangxian minghuxi 陽羨茗壺系 (Yangxian Teapot Series), 9–10.

79 Wu Meiding 吳梅鼎, “Yangxian minghufu 陽羨茗壺賦 (Poem about Famous Teapots in Yangxian),” 880.

80 Brokaw and Chow, Printing and Book Culture.

81 Brokaw and Chow, Printing and Book Culture, 24.

82 McDermott, A Social History of the Chinese Book, 102; Meyer-Fong, “The Printed World,” 787–817.

83 Brokaw and Chow, Printing and Book Culture, 24.

84 Wu, Chengyi 吳誠一, Yijin wushi zongpu 宜荊吳氏宗譜 (Genealogy of the Yijing Wu Family).

85 Li Minxing 李敏行, “Yangxian minghuxi zhi kaozheng 《陽羨茗壺系》 之考證.” 68–73; Chen Ning 陳寧. “Yangxian minghuxi neirong jiazhi pingxi 《陽羨茗壺系》 內容價值評析.” 174–77.

86 Brook, Troubled Empire, 135–36.

87 Brook, Troubled Empire, 136–37.

88 Waltner, Getting an Heir, 1.

89 Freedman, Lineage Organization, 90.

90 Chu, “Intellectual Trends in the Fifteenth Century,” 2.

91 Chu, “Intellectual Trends in the Fifteenth Century,” 2.

92 Chu, “Intellectual Trends in the Fifteenth Century,” 3.

93 Bol, “The Rise of Local History,” 37–76.

Dennis, Writing, Publishing, and Reading Local Gazetteers, 29–30.

94 Clunas, Superfluous Things, 132.

95 Cai, Dingyi 蔡定益, Xiangming yaqi: Mingdai chaju yu Mingdai shehui 香茗雅器:明代茶具與明代社會, 116.

96 Wen, Long 聞龍, “Cha Jian 茶箋 (A Note on Tea),” 411.

97 Wen, Long 聞龍, “Cha Jian 茶箋 (A Note on Tea),” 411.

98 Bourdieu, Distinction: A Social Critique, 257–317.

99 Bourdieu, Distinction: A Social Critique, 260.

100 Jenkins, Pierre Bourdieu, 82–86.

101 Veblen, Conspicuous Consumption, 42; Veblen, The Theory of the Leisure Class, 39.

Bibliography

- Ao Xuanbao 奧玄寶 “Minghu tulu 茗壺圖錄.” In Zhonghua meishu congshu 中華美術叢書, vol. 12, edited by Deng Shiru 鄧實, and Huang Binhong 黃賓虹, 7–8. Beijing: Beijing guji chubanshe, [1874] 1998.

- Benn, J. A. Tea in China: A Religious and Cultural History. Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press, 2015.

- Blofeld, J. The Chinese art of tea. Boston: Shambhala, 1985.

- Bol, P. K. “The rise of local history: history, geography, and culture in southern Song and Yuan Wuzhou.” Harvard Journal of Asiatic Studies (June 2001): 37–76.

- Bourdieu, P. Distinction: A Social Critique of the Judgement of Taste. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1996.

- Brokaw, C. J., and K. Chow. Printing and Book Culture in Late Imperial China. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2005.

- Brook, T. The Troubled Empire: China in the Yuan and Ming Dynasties. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2010.

- Cai Dingyi 蔡定益. Xiangming yaqi: Mingdai chaju yu Mingdai shehui 香茗雅器:明代茶具與明代社會. Beijing: Zhongguo shehui kexue chubanshe, 2021.

- Cai Xiang 蔡襄. Chalu ji qita jizhong 茶錄及其他幾種. Shanghai: Shangwu yinshuguan, [1064] 1936.

- Chen Baoliang. “Ming Dynasty Literati: Differentiation and Analysis.” Hanxue Yanjiu (Chinese Studies) 19 (2001): 187–218.

- Chen Linwei 陳遴瑋, Wang Sheng 王升. Wuxi wenku diyiji: chongxiu Yixing xianzhi 無錫文庫第一輯:重修宜興縣誌. Nanjing: Fenghuang chubanshe, [1590] 2012.

- Chen Ning 陳寧. “Yangxian minghuxi neirong jiazhi pingxi 《陽羨茗壺系》 內容價值評析.” Nongye kaogu 農業考古 2 (2016): 174–177.

- Chu Hung-lam. “Intellectual trends in the fifteenth century.” Ming Studies 1 (1989): 1–33.

- Clunas, C. Elegant Debts: The Social Art of Wen Zhengming, 1470–1559. Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press, 2004a.

- Clunas, C. Pictures and Visuality in Early Modern China. London: Reaktion Books, 1997.

- Clunas, C. Superfluous Things: Material Culture and Social Status in Early Modern China. Honolulu: University of Hawai’I Press, 2004b.

- Cui Laiting 崔來廷. Mingqing jiake shijia yanjiu 明清甲科世家研究. Beijing: Zhishi banquan chubanshe, 2013.

- Dennis, J. R. Writing, publishing, and reading local gazetteers in imperial China, 1100–1700. Cambridge: Harvard University Asia Center, 2015.

- Ebrey, P. B. The Aristocratic Families of Early Imperial China: A Case Study of the Po-ling Ts’ui Family. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1978.

- Elman, B. A. “Political, Social, and Cultural Reproduction via Civil Service Examinations in Late Imperial China.” The Journal of Asian Studies 50, no. 1 (1991): 7–28.

- Elman, B. A. A Cultural History of Civil Examinations in Late Imperial China. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2000.

- Freedman, M. Lineage Organization in Southeastern China. London: Athlone Press, 1965.

- Gao, X., and A. Hein. “The Authenticity Problem in Contemporary Techniques of Zisha Teapot Making.” In Understanding Authenticity in Chinese Cultural Heritage, edited by Anke Hein, and Christopher J. Foster, 171–185. London: Routledge, 2023.

- Gao, X. “Unravelling the Complex Meanings and Origins of Zisha Teapots in the Ming and Qing Dynasties.” PhD diss., University of Oxford, 2023.

- Gong Zhiyi 龔之怡 “Jiangyin Xianzhi 江陰縣誌.” In Wuxi wenku 無錫文庫, edited by Gongzuo Weiyuanhui 無錫文庫工作委員會, 1–380. Nanjing: Fenghuang chubanshe, [1654–1722] 2011.

- Gronow, Jukka. The Sociology of Taste. London: Routledge, 1997.

- Gu Jingzhou 顧景舟, Xu Xiutang 徐秀棠, and Li Changhong 李昌鴻. Yixing zisha zhenshang 宜興紫砂珍賞. Hong Kong: Xianggang sanlian shudian, 1992.

- Gu Yuanqing 顧元慶 and Qian Chunnian 錢椿年. “Chapu 茶譜.” In Zhongguo lidai chashu huibian jiaozhuben 中國歷代茶書彙編校注本, edited by Zheng Peikai 鄭培凱, and Zhu Zizhen 朱自振, 178–185. Hong Kong: Shangwu yinshuguan youxian gongsi, [ca. 1536–1541] 2014.

- Han Renjie 韓人傑, Han Renjie 韓人傑, Ye Longgeng 葉龍耕, He Panfa賀盤發, Li Changhong李昌鴻, Gao Haigeng 高海庚. “Yixing zishatao de shengchan gongyi tedian he xianwei jiegou 宜興紫砂陶的生產工藝特點和顯微結構.” Guisuan yantongbao 矽酸鹽通報 (1981): 26–35.

- Hang Tao 杭濤 and Ma Yongqiang 馬永強. “Yixing shushan yaozhi de fajue 宜興蜀山窯址的發掘.” Gugong wenwu yuekan 故宮文物月刊 302 (2008): 44–51.

- He Panfa 賀盤發. “Yixing zishani zongshu 宜興紫砂泥綜述.” Jiangsu taoci 江蘇陶瓷 (1988): 30–38.

- He Yue 何嶽 “Gongchun: yige chuanqi yihuo ‘yangmou’ 供春:一個傳奇抑或‘陽謀’.” Zisha yishu 紫砂藝術 28, no. 5 (2013): 77–84.

- Hinsch, B. The Rise of Tea Culture in China: The Invention of The Individual. Washington: Rowman & Littlefield, 2015.

- Hong Kong Museum of Art. The Art of the Yixing Potter: The K.S. Lo Collection, Flagstaff House Museum of Tea Ware. Hong Kong: Hong Kong Urban Council, 1990.

- Hu Jing 胡婧. “Ming zhongqi Yixing jimeitang wushi yanjiu 明中期宜興濟美堂吳氏研究.” Master’s diss., Nanjing University 南京大學, 2018

- Hu Zhen 胡真. Baijiaxing 百家姓. Shanghai: Shanghai guji chubanshe, 2014.

- Jenkins, R. Pierre Bourdieu. London: Routledge, 2013.

- Jiang Jun 蔣君 “Zhongguo diyipian zanmei zisha jiafu de zuozhe — Wu Meiding yu yixing zisha中國第一篇讚美紫砂佳賦得作者 — 吳梅鼎與宜興紫砂.” In Zhongguo zisha hudian 中國紫砂壺典, edited by Jiang Jun 蔣君, 203–211. Beijing: Wenwu chubanshe, 2014a.

- Jiang Jun 蔣君. “Zhongguo zisha taogong shishang jizai de diyige mingzi — zishahu bizu Gongchun中國紫砂陶工史上記載得第一個名字 — 紫砂壺鼻祖供春.” In Zhongguo zisha hudian 中國紫砂壺典, edited by Jiang Jun 蔣君, 181–190. Beijing: Wenwu chubanshe, 2014b.

- Kerr, R., and N. Wood. Ceramic Technology, Chemistry and Chemical Technology, Vol. 5, Part XII of Science and Civilisation in China, edited by Joseph Needham. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2004.

- Ko, D. The Social Life of Inkstones: Artisans and Scholars in Early Qing China. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2017.

- Kroll, P. W. A Student’s Dictionary of Classical and Medieval Chinese: Revised Edition. Leiden: Brill, 2017.

- Li Minxing 李敏行. “Yangxian minghuxi zhi kaozheng 《陽羨茗壺系》 之考證.” Nanfang wenwu 南方文物 1 (2008): 68–73.

- Li Wai-yee. The Promise and Peril of Things: Literature and Material Culture in Late Imperial China. New York: Columbia University Press, 2022.

- Liao Baoxiu 廖寶秀. Lidai chaqi yu chashi 歷代茶器與茶事. Beijing: Gugong chubanshe, 2004.

- Lo, K.-S. “Patronage and Its Influence on Yixing Teapots.” In Innovations in Contemporary Yixing Pottery, edited by Hong Kong Urban Council, Flagstaff House Museum of Tea Ware, and Sheung Yu Ceramic Arts Limited, 15–31. Hong Kong: Hong Kong Urban Council, 1988.

- Lu Tong 盧仝. “Zhoubi Xie Mengjian Yijixincha走筆孟諫議寄新茶.” In Quan tangshi 全唐詩, edited by Cao Ying 曹寅, and Peng Dingqiu 彭定求, 4379. Beijing: Zhonghua shuju, [n.d.] 1960.

- Lü Weixin 呂維新, Qian Kaixin 錢開信, and Wang Xuejin 王學進. “Ping mingtaizu ‘bazaolongtuan’評明太祖 ‘罷造龍團’.” Nongye kaogao 農業考古 4 (1997): 126–128.

- Lu Yu. The Classic of Tea, trans. Francis Ross Carpenter. Boston: Little, Brown and Company, [764] 1974.

- McDermott, J. P. A Social History of the Chinese Book: Books and Literati Culture in Late Imperial China. Vol. 1. Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press, 2006.

- McNair, A. The Upright Brush: Yan Zhenqing’s Calligraphy and Song Literati Politics. Honolulu: University of Hawai’I Press, 1998.

- Meyer-Fong, T. “The Printed World: Books, Publishing Culture, and Society in Late Imperial China.” The Journal of Asian Studies 66, no. 3 (2007): 787–817.

- Mote, F. W., and D. Twitchett. The Cambridge History of China. Vol. 7, The Ming Dynasty, 1368–1644, Part I. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1991.

- National Museum of China 中國國家博物館. Gong Chun zishahu 供春紫砂壺, National Museum of China website, April 8, 2022, available online at https://www.chnmuseum.cn/zp/zpml/kgfjp/202011/t20201109_248041.shtml.

- Park, J. P. Art by the Book: Painting Manuals and the Leisure Life in Late Ming China. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2017.

- Qin Jiang and James Kai-sing Kung. “Social Mobility in Late Imperial China: Reconsidering the “Ladder of Success” Hypothesis.” Modern China 47, no. 5 (2021): 628–661.

- Shanxisheng Kaogu Yanjiusuo 陝西省考古研究所, Famensi Bowuguan 法門寺博物館, Bojishi Wenwuju 寶雞市文物局, and Fufengxian Bowuguan 扶風縣博物館. Famensi kaogu fajuebaogao 法門寺考古發掘報告. Bejing: Wenwu chubansh, 2007.

- Shao Bao 邵寶. Rongchutang ji 容春堂集. Shanghai: Shanghai guji chubanshe, [1534] 1992.

- Stephens, G. “Boundaries, Names, Texts, and a Bamboo Cap: Glimpses into the Arena of Late Ming ‘Literati Culture’.” Master’s diss. University of Oxford, 1995.

- Sun Jin 孫荊, and Ruan Meilin 阮美玲. “Yixing zishatao de xianweijiegou he zishaqi de touqixing 宜興紫砂陶的顯微結構和紫砂器的透氣.” Zhongguo taoci 中國陶瓷 (1993): 21–25.

- Tackett, N. The destruction of the medieval Chinese aristocracy. Cambridge: Harvard University Asia Center, 2014.

- Tu Benjun 屠本畯. “Mingji 茗笈.” In Zhongguo Gudai Chashu Jicheng 中國古代茶書集成, edited by Zhu Zizhen 朱自振, and Shen Dongmei 沈冬梅, 332–344. Shanghai: Shanghai wenhua chubanshe, [1606–1610] 2010.

- Veblen, T. Conspicuous consumption. London: Penguin, 2005.

- Veblen, T. The Theory of the Leisure Class. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007.

- Waltner, A. Getting an Heir: Adoption and the Construction of Kinship in Late Imperial China. Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press, 2019.

- Wang Li 王力, Cen Qixiang 岑麒祥, and Lin Taoyuan 林燾原. Guhanyu changyongzi zidian 古漢語常用字字典. Beijing: Shangwu yinshuguan, 2016.

- Wen Long 聞龍. “Cha Jian 茶箋.” In Zhongguo gudai chashu jicheng 中國古代茶書集成, edited by Zhu Zizheng 朱自振, and Shen Dongmei 沈冬梅, 410–412. Shanghai: Shanghai Wenhua Chubanshe, [1610–1630] 2010.

- Wen Zhengheng 文震亨. Changwuzhi jiqita liangzhong 長物志及其他兩種. Shanghai: Shangwu yinshuguan, [1621] 1936.

- Wen Zhengming 文征明. “Xie Yixing Wudaben jicha 謝宜興吳大本寄茶.” In Wen Zhengming ji 文征明集. Shanghai: Shanghai guji chubanshe, 1987.

- Wilkinson, E. P. Chinese History: A Manual, Vol. 52. Cambridge: Harvard University Asia Center, 2000.

- Wu Chengyi 吳誠一. Yijin wushi zongpu 宜荊吳氏宗譜. Yixing: Jimeitang, 1926.

- Wu Meiding 吳梅鼎. “Yangxian minghufu 陽羨茗壺賦.” In Zhongguo lidai chashu huibian jiaozhuben 中國歷代茶書彙編校注本, edited by Zheng Peikai 鄭培凱, and Zhu Zizhen 朱自振, 880–882. Xianggang: Shangwu yinshuguan, 2014 [1786].

- Wu, Qian 吳騫. “Yangxian mingtaolu 陽羨名陶錄.” In Zhongguo lidai chashu huibian jiaozhuben 中國歷代茶書彙編校注本, edited by Zheng Peikai 鄭培凱, and Zhu Zizhen 朱自振, 870–894. Xianggang: Shangwu yinshuguan, 2014.

- Wu Shi吳仕. “Yishan sigao 頤山私稿.” In Beijing Tushuguan guji zhenben congkan 北京圖書館古籍珍本叢刊, edited by Beijing Tushuguan Guji Chuban Bianjizu 北京圖書館古籍出版編輯組. Beijing: Shumu wenxian chubanshe, [ca. 1450–1550] 1998.

- Wu Zhihe 吳智和. “Mingdai charen de chaliao yijiang 明代茶人的茶寮意匠.” Shixue jikan 史學集刊 3 (1993): 15–23.

- Wu Zhihe 吳智和. “Zhongming caren jituan de yincha xingling shenghuo 中明茶人集團的飲茶性靈生活.” Shixue jikan 史學集刊 4 (1991): 52–63.

- Xu Cishu 許次紓. “Chashu 茶疏.” In Zhongguo lidai chashu huibian jiaozhuben 中國歷代茶書彙編校注本, edited by Zheng Peikai 鄭培凱, and Zhu Zizhen 朱自振, 257–265. Hongkong: Shangwu yinshuguan youxian gongsi, 2014.

- Yang Zhenya 楊振亞. “Guanyu gongchunhu de jige wenti 關於供春壺的幾個問題.” Jiangsu taoci 江蘇陶瓷 70, no. 3 (1995): 35–38.

- Yang Zhishui 楊之水. Hunshi louji juanliu liangsong chashi 棔柿樓集 卷六 兩宋茶事. Beijing: Renmin meishu chubanshe, 2015.

- Yao Minsu 姚敏蘇. “Cong ‘zini xinpin’ shuodao ‘gongchunhu’ 從‘紫泥新品’說到‘供春壺’.” Nongye kaogu 農業考古 4 (1992): 103–104.

- Zhan Zhijie 戰志傑. “‘Gongchun’ kaobian ‘供春’考辨.” Dazhong kaogu 大眾考古 1 (2016): 41–43.

- Zhou Gaoqi 周高起. Yangxian minghuxi 陽羨茗壺系. Beijing: Zhonghua shuju, [1697] 2012.

- Zhu Yunfeng 朱雲峰, Liu Liming 劉李明, and Zhou Wei 周瑋. “Dui zishahu qiyuan zhizheng de bianxi 對紫砂壺起源之爭的辨析.” Nongye kaogu 農業考古 2 (2015): 63–69.