ABSTRACT

Napsin A is an aspartic proteinase expressed in some types of carcinomas, such as lung adenocarcinomas and renal cell carcinomas but rarely in squamous cell carcinomas. No specific studies have been carried out focusing on napsin A antibody expression in oral squamous cell carcinomas (OSCC). The aim of this study was to investigate the reactivity of this antibody in primary OSCC. This retrospective study included 70 OSCC cases of which 31 (44.3%) presented metastasis involvement. Patient data, including age, gender, tumor location, histological grade, regional and distant metastasis, were collected. OSCC edge epithelium with intraepithelial neoplasia and healthy oral mucosa (n = 10) were included in the analysis. Sections of lung adenocarcinomas (n = 2) were used as the positive control and an immunohistochemical assay for napsin A was performed on all cases. Napsin A expression was negative in all 70 cases of OSCC, as well as in the intraepithelial neoplasia adjacent to the carcinoma area and in healthy oral mucosa epithelium. Metastatic neck lymph nodes and distant organs were also negative for napsin A. This study shows that napsin A is consistently not expressed in oral squamous cell carcinoma, or in metastatic sites of primary OSCC, intraepithelial neoplasia, and healthy oral mucosa

Introduction

Napsin A, also known as aspartyl protease 4, ASP4, napsin 1 TA01/TA02, KDAP, snapA, is a single-chain aspartic proteinase involved in the N- and C-terminal processing of prosurfactant protein B. It is normally expressed in type II pneumocytes, Clara cells, and macrophages in the lungs, as well as in the proximal tubular epithelium of normal kidney, amongst others [Citation1–4]. It has been shown that this protein is intensely expressed in lung adenocarcinomas [Citation2–15] as well as in some subsets of renal cell carcinomas [Citation16] and clear cell carcinomas of the gynecologic tract [Citation17,Citation18]. This marker is, however, negative for adenocarcinomas in other sites, such as the colon, pancreas, and breast [Citation3]. The majority of studies published have indicated that napsin A is rarely expressed in squamous cell carcinomas of the lung [Citation3,Citation5,Citation7,Citation8,Citation11,Citation13]. For the oral cavity, with the exception of one article, no further specific studies focusing on napsin A expression in OSCC were found in the literature.

Oral squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC) is the most common malignancy that arises in the head and neck and despite recent advances, its prognosis remains dismal with a 5-year mortality rate in approximately 50% of the cases [Citation19,Citation20].

The aim of our study was to determine the napsin A expression in a series of OSCC cases or in metastatic sites of primary OSCC, intraepithelial neoplasia, and healthy oral mucosa.

Materials and methods

Seventy formalin-fixed paraffin-embedded biopsies and/or excisions of primary OSCC were selected from the archives of the Laboratory of Oral & Maxillofacial Pathology, Oral Medicine, Oral and Maxillofacial Pathology Unit, Department of Surgery, Geneva University Hospitals. The study (protocol number 12–162 R/Psy 12–013 R) was approved by the Ethics Commission of the University Hospitals of Geneva (UHG), University of Geneva, Geneva, Switzerland. Additional informed consent was not required for this retrospective study.

The OSCC cases with the previous history of chemotherapy or radiotherapy treatment were excluded. Ten cases of healthy oral mucosa, as well as the OSCC edge epithelium with intraepithelial neoplasia, were included in this analysis. Sections of lung adenocarcinomas (n = 2) served as the positive control. The number of cases were as follows: healthy oral tissue in the vestibular mucosa (n = 1), the lower lip (n = 1), oral mucosa (n = 6), and palatine mucosa (n = 2). Neck lymph nodes and different organs which have undergone primary OSCC infiltration were also analyzed. Sections 3 µm thick of all cases were stained with Harris hematoxylin (1.092530500, Merck, Switzerland) and Eosin Y 1% (1.15935.0025, Merck), were examined microscopically, and tumors graded according to the system proposed by the World Health Organisation (WHO).

Immunohistochemistry

An immunohistochemical assay was done manually. Paraffin sections were mounted on organosilane-pretreated slides (Superfrost Plus, J1800AMNZ, Thermo Scientific, Switzerland) deparaffinized with xylene, rehydrated in a descending alcohol gradient and distilled water (DIH2O). For antigen retrieval, slides were immersed in Target Retrieval Solution, Citrate pH 6 (S236984, Dako/Agilent Technologies, USA) and boiled three times, 5 min each, in a microwave oven 400 W (Panasonic NM-S2559w, Switzerland). Phosphate buffered saline (PBS, pH7, S3024, Dako) was used between each step as a rinse. The endogenous peroxidase activity was removed by immersion in 3% hydrogen peroxide according to instructions in EnVision+ Dual Link HRP DAB, Rabbit/Mouse kit (K4065, Agilent), for 5 min. Mouse anti-Napsin A, monoclonal, IgG2b clone IP64, (code NCL-L-Napsin A, Novocastra/Leica Biosystems, RRID: AB_10555426, Switzerland) at 1:400 dilution using Dako Antibody Diluent with Background Reducing Components (S3022, Agilent) was applied to sections and incubated for 30 min at RT. Colon was used as a negative control. For the negative control of the reaction, the primary antibody was omitted and replaced by a Mouse IgG2b kappa Isotype Control (eBMG2b, eBioscience, Switzerland), with the same concentration as the mouse anti-Napsin A monoclonal antibody. The sections were incubated with biotinylated secondary rabbit/mouse antibodies HRP from the kit for 30 min and visualized with the kit 3.3ʹ-diaminobenzidine-DAB for 10 min, counterstained with Harris hematoxylin (1.092530500, Merck) for 30 sec, dehydrated in graded alcohols, cleared in xylene and cover glass mounted with Neo-mount (1.09016.0500, Merck, Germany). Napsin A analysis was performed using a light microscope (Olympus BX50, Olympus Corp, Japan) at a 40x magnification.

Results

Within the OSCC cases analyzed, 50 (71.4%) were male, and 20 (28.6%) were female. The age ranged from 32 to 81 years (mean age = 61 years). Of all the 70 cases, 29 were classified as well-differentiated OSCC, 35 as moderately differentiated OSCC, and 6 as poorly differentiated OSCC. Thirty-nine cases (55.7%) did not present metastases, while 31 (44.3%) had neck lymph node metastatic involvement. Seven of these 31 cases also had a distant metastasis in the liver (n=1), lung (n=2), and multiple organs (n=4) including the lung among others. The primary sites of OSCC included tongue (n = 26); floor of the mouth (n = 17); retromolar area (n = 10); tongue + floor of the mouth (n = 5) and others (n = 12) such as gingiva and the hard and soft palates ().

Table 1. Summary of patient population (n = 70) and clinical characteristics

Immunohistochemistry assay

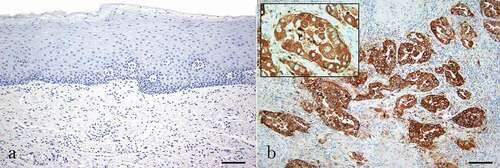

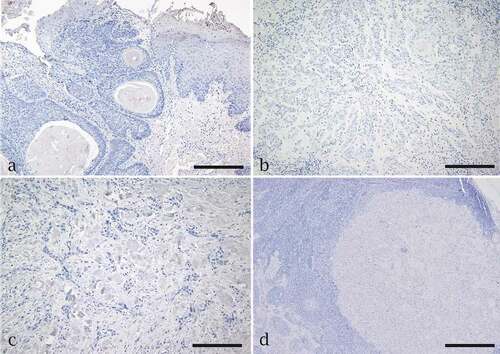

The healthy oral mucosa cases (n = 10) presented a negative expression for napsin A (). In the positive control lung adenocarcinoma (n = 2), napsin A expression was intensely positive in the cytoplasm of tumor cells with greater than or equal to 90% of labelled cells (). All cases (n = 70, 100%) of OSCC, which included well-differentiated, moderately differentiated, and poorly differentiated tumors were negative for napsin A. Areas adjacent to the carcinoma presenting intraepithelial neoplasia did not stain for that antibody (). The IHC results also revealed no napsin A expression in tumor cells from primary OSCC that had metastasized into either neck lymph nodes () or different organs, such as the liver or lung (results not shown).

Figure 1. Immunohistochemistry assay for Napsin A expression. (a) Negative expression in healthy oral mucosa. (b) Napsin A has strong, diffuse granular cytoplasmic expression in pulmonary adenocarcinoma. (DAB) Scale bar = 400 µm

Figure 2. Immunohistochemistry assay for Napsin A expression in oral squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC). Negative expression of napsin A is seen in (a) a well-differentiated tumor and edge of the epithelium, (b) a moderately differentiated tumor, (c) a poorly differentiated tumor and (d) OSCC metastasis to neck lymph node. Scale bar = 200 µm for a, b,c. Scale bar = 50 µm for d

Discussion and conclusion

Although napsin A is strongly expressed in lung adenocarcinoma [Citation2–15], which can range from 65.3% to 90.7% [Citation2-5,Citation9], it is not specific for this tumor [Citation3,Citation16,Citation18]. Napsin A immunoreactivity is also found in the majority of papillary renal cell carcinomas (79% to 87.5%), in a smaller percentage (10% to 34%) of clear cell renal cell carcinomas [Citation3,Citation9,Citation14,Citation21], and is seen in papillary thyroid carcinomas [Citation21,Citation22], endometrial clear cell carcinoma, clear cell adenocarcinoma of the cervix and ovarian clear cell carcinoma [Citation17,Citation23]. Except for two studies [Citation24,Citation25], napsin A expression has not been observed in squamous cell carcinomas of the lung [Citation4,Citation5,Citation7,Citation9,Citation11,Citation13]. Hirano et al. [Citation2] published the first immunohistochemical study on napsin A expression in lung carcinomas in 2000. By using the mouse monoclonal antibody against TA02 (napsin A), these authors reported napsin A positivity in 81% of lung adenocarcinomas, but in none of the cases of lung squamous cell carcinomas. These results were subsequently confirmed by the same group of investigators who reported a high expression (90.7%) for TA02 (napsin A) in primary lung adenocarcinomas and no expressions in squamous cell carcinomas of the lung [Citation5]. Turner et al. [Citation25] studied the presence of napsin A in 555 lung neoplasms with positive expression seen in 264 (87%) out of 303 cases of lung adenocarcinoma, as compared to 5 (3%) out of 200 cases of primary pulmonary squamous cell carcinomas and no expression in 52 cases of lung small cell carcinoma. They also showed that in 703 cases of non-pulmonary adenocarcinomas from bladder, pancreas, breast, liver, biliary tract, colon, ovary, uterus, prostate, and stomach, all had a weak positive napsin A expression varying from 0% to 8%. In our results, all cases of OSCC were negative for napsin A. Metastatic OSCC to either neck lymph nodes () or various organs including the liver and lung were also negative for napsin A (not shown). The healthy oral mucosa and intraepithelial neoplasia areas adjacent to the carcinomas did not show any labelling for napsin A (). According to Pereira et al. [Citation24], no staining for napsin A was observed in squamous cell carcinoma of the oral cavity (with no region specification), pharynx, or larynx. Some immunoreactivity for this marker, however, was found in squamous cell carcinomas of the tongue (13.3%), skin (7.7%), and penis (37.5%). The variations regarding napsin A expression may have been the result of different case selections and different immunohistochemical techniques used. In conclusion, this study demonstrated that napsin A is not expressed either in OSCC or in oral intraepithelial neoplasia, healthy oral mucosa, or even in tumor cells that metastasized in neck lymph node and distant organs.

Acknowledgments

Nicolay Gaydarov was responsible for the selection of cases, literature search, and manuscript preparation. Carla P. Martinelli-Kläy participated in the drafting and revision of the manuscript as well as the microscopic analysis of the selected cases. Tommaso Lombardi had a major contribution to the conception and critical revision of the manuscript. The authors thank technicians, Eliane Dubois, and Claire Herrmann for their valuable contribution.

Disclosure statement

No conflicts of interest have been declared by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Stelow EB, Yaziji H. Immunohistochemistry, carcinomas of unknown primary, and incidence rates. Semin Diagn Pathol. 2018;35(2):143–152.

- Hirano T, Auer G, Maeda M, et al. Human tissue distribution of TA02, which is homologous with a new type of aspartic proteinase, napsin A. Jpn J Cancer Res. 2000;91(10):1015–1021.

- Bishop JA, Sharma R, Illei PB. Napsin A and thyroid transcription factor-1 expression in carcinomas of the lung, breast, pancreas, colon, kidney, thyroid, and malignant mesothelioma. Hum Pathol. 2010;41(1):20–25.

- Ueno T, Linder S, Elmberger G. Aspartic proteinase napsin is a useful marker for diagnosis of primary lung adenocarcinoma. Br J Cancer. 2003;88(8):1229–1233.

- Hirano T, Gong Y, Yoshida K, et al. Usefulness of TA02 (napsin A) to distinguish primary lung adenocarcinoma from metastatic lung adenocarcinoma. Lung Cancer. 2003;41(2):155–162.

- Inamura K, Satoh Y, Okumura S, et al. Pulmonary adenocarcinomas with enteric differentiation: histologic and immunohistochemical characteristics compared with metastatic colorectal cancers and usual pulmonary adenocarcinomas. Am J Surg Pathol. 2005;29(5):660–665.

- Suzuki A, Shijubo N, Yamada G, et al. Napsin is useful to distinguish primary lung adenocarcinoma from adenocarcinomas of other organs. Pathol Res Pract. 2005;201(8–9):579–586.

- Dejmek A, Naucler P, Smedjeback A, et al. Napsin A (TA02) is a useful alternative to thyroid transcription factor-1 (TTF-1) for the identification of pulmonary adenocarcinoma cells in pleural effusions. Diagn Cytopathol. 2007;35(8):493–497.

- Stoll LM, Johnson MW, Gabrielson E, et al. The utility of napsin-A in the identification of primary and metastatic lung adenocarcinoma among cytologically poorly differentiated carcinomas. Cancer Cytopathol. 2010;118(6):441–449.

- Terry J, Leung S, Laskin J, et al. Optimal immunohistochemical markers for distinguishing lung adenocarcinomas from squamous cell carcinomas in small tumor samples. Am J Surg Pathol. 2010;34(12):1805–1811.

- Yang M, Nonaka D. A study of immunohistochemical differential expression in pulmonary and mammary carcinomas. Mod Pathol. 2010;23(5):654–661.

- Fatima N, Cohen C, Lawson D, et al. TTF-1 and napsin A double stain: a useful marker for diagnosing lung adenocarcinoma on fine needle aspiration cell blocks. Cancer Cytopathol. 2011;119(2):127–133.

- Mukhopadhyay S, Katzenstein AL. Subclassification of non-small cell lung carcinomas lacking morphologic differentiation on biopsy specimens: utility of an immunohistochemical panel containing TTF-1, napsin A, p63, and CK5/6. Am J Surg Pathol. 2011;35(1):15–25.

- Ye J, Findeis-Hosey JJ, Yang Q, et al. Combination of Napsin A and TTF-1 immunohistochemistry helps in differentiating primary lung adenocarcinoma from metastatic carcinoma in the lung. Appl Immunohistochem Mol Morphol. 2011;19(4):313–317.

- Piljić Burazer M, Mladinov S, Ćapkun V, et al. The utility of thyroid transcription factor 1 (TTF-1), napsin A, Excision Repair Cross-Complementing 1 (ERCC1), Anaplastic Lymphoma Kinase (ALK) and the Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor (EGFR) expression in small biopsy in prognosis of patients with lung adenocarcinoma - a retrograde single-center study from Croatia. Med Sci Monit. 2017;23:489–497.

- Zhu B, Rohan SM, Lin X. Immunoexpression of napsin A in renal neoplasms. Diagn Pathol. 2015;10:4.

- Yamashita Y, Nagasaka T, Naiki-Ito A, et al. Napsin A is a specific marker for ovarian clear cell adenocarcinoma. Modern Pathol. 2015;28(1):111–117.

- Iwamoto M, Nakatani Y, Fugo K, et al. Napsin A is frequently expressed in clear cell carcinoma of the ovary and endometrium. Hum Pathol. 2015;46(7):957–962.

- Nocini R, Lippi G, Mattiuzzi C. Biological and epidemiologic updates on lip and oral cavity cancers. Ann Cancer Epidemiol. 2020;4:1–6.

- Epstein JB, Kish RV, Hallajian L, et al. Head and neck, oral, and oropharyngeal cancer: a review of medicolegal cases. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol. 2015;119(2):177–186.

- Kadivar M, Boozari B. Applications and limitations of immunohistochemical expression of Napsin-A” in distinguishing lung adenocarcinoma from adenocarcinomas of other organs. Appl Immunohistochem Mol Morphol. 2013;21(3):191–195.

- Wu J, Zhang Y, Ding T, et al. Napsin A expression in subtypes of thyroid tumors: comparison with lung adenocarcinomas. Endocr Pathol. 2020;31(1):39–45.

- Ju BH, Wang JM, Yang B, et al. Morphologic and Immunohistochemical study of clear cell carcinoma of the uterine endometrium and cervix in comparison to ovarian clear cell carcinoma. Int J Gynecol Pathol. 2018;37(4):388–396.

- Pereira TC, Share SM, Magalhães AV, et al. Can we tell the site of origin of metastatic squamous cell carcinoma? An immunohistochemical tissue microarray study of 194 cases. AIMM. 2011;19(1):10–14.

- Turner BM, Cagle PT, Sainz IM, et al. Napsin A, a new marker for lung adenocarcinoma, is complementary and more sensitive and specific than thyroid transcription factor 1 in the differential diagnosis of primary pulmonary carcinoma: evaluation of 1674 cases by tissue microarray. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2012;136(2):163–171.