Abstract

Informal foster care remains the preferred alternative care option for children in many parts of the world. However, the processes of reunification in informal foster care are largely unknown. This qualitative study sought to explore the reunification processes within informal foster care in Ghana to inform child protection services for better program design for such children. Twenty interviews were conducted with reunified fostered children and their biological parents. Data from the in-depth interviews with parents and children were analyzed thematically. Three main processes of reunification were identified in this study namely; open, flexible exit plans and educational threshold arrangements. The findings show that reunification pathways are informed by the factors that informed the placement. A model of reunification, based on the study findings has been suggested to guide further studies. Child protection workers should utilize the reunification model as a framework to design services for children who are reunified in informal foster care. Researchers could also utilize the reunification model as a tool to study the outcomes for children who have been reunified. Further research should also explore measures and mechanism that are needed to integrate best practices of the informal foster care processes within the formal child protection domain.

Introduction

In many developing countries, child protection concerns have been identified to be prevalent within informal care, including informal foster care (Bywaters, Citation2019; Connolly & Katz, Citation2019). This is because developing countries are generally characterized as having less developed formal child protection systems. Deininger et al. (Citation2003) found that one out of every three households in Uganda had a foster child in their care. Kuyini et al. (Citation2009) also identified informal foster care practices to be common in communities in the northern parts of Ghana. Studies have established that cultural motives and the quest to strengthen family ties are among the primary motives for informal foster care placements in Africa (Abdullah, Frederico et al., Citation2020; Ansah-Koi, Citation2006; Kuyini et al., Citation2009; Nnama-Okechukwu et al., Citation2020). These motives, to a larger extent, replace or supplement the child welfare intent of foster care placement. This suggests that reasons for informal foster placement and reunification with birth parents will differ.

Growing evidence shows that in Africa children in informal care experiences severe maltreatment, including sexual abuse (Nnama-Okechukwu et al., Citation2020; Ushie et al., Citation2016) and neglect (Abdullah, Frederico et al., Citation2020), which are indicative that children in informal foster care may return to their birth parents for safety. Therefore, unraveling the processes of reunification could enable the provision of better services by child protection workers for the best outcomes for such children.

Goal of Fostering in Africa

Foster care describes a temporary to long-term alternative care arrangement for children whose parents are deemed to be unable to guarantee their safety and wellbeing (Child Welfare Information Gateway, Citation2020). The goal of fostering is to safeguard the best interest, safety and welfare of children by providing them with adequate parental care (Gypen et al., Citation2017). In line with child welfare objectives of promoting permanency and wellbeing (Akin, Citation2011; Fowler & Schoeny, Citation2017), fostered children are required to reunite with their birth parents after conditions that precipitated their placement are eliminated, improved or restored. However, informal foster care underlies a care arrangement outside the formal child protection system. Unlike developed countries, which practice foster care formally (Fernandez, Citation2014; Fernandez et al., Citation2019), African countries mainly practice foster care informally (Nnama-Okechukwu et al., Citation2020). Informal foster care practice has its root in the culture and social structure of communities and neighborhoods (Nukunya, Citation2016).

Nnama-Okechukwu et al. (Citation2020) describe informal foster care as a temporal to long-term flexible care arrangement by families and communities, in which a child moves to stay with blood-related relatives or non-blood-related parents, for diverse reasons including adhering to cultural traditions and orphanhood. Ansah-Koi (Citation2006) revealed that informal fosterage becomes the most likely alternative care option for parentless children and children who have been left behind through parental death, migration, incarceration and mental illness. The preference for informal foster care in Ghana is supported by the evidence that most children that are placed in institutional care homes report more negative than positive outcomes (Abdullah, Frederico et al., Citation2018; Manful et al., Citation2020) and also exhibit behaviors that are different from those who are raised in Ghanaian families (Darkwah et al., Citation2016).

Nukunya (Citation2016) suggest that informal foster care practices are considered mechanisms and pathways for children to be integrated into Ghanaian culture. This is because it is the belief that family members are in a better position to socialize and inculcate societal norms into a child (Ansah-Koi, Citation2006). Also, the pursuit of quality education (Asuman et al., Citation2018) and skills training (Kuyini et al., Citation2009) are some of the common reasons informal foster care exists in most Ghanaian and African communities.

In addition, informal fostering serves as an opportunity to invest in a child as social insurance. Some parents in Ghana, who do not have biological children, are often given the opportunity to care for children of their relatives as their own, to compensate for their security in the future (Ansah-Koi, Citation2006; Ardington & Leibbrandt, Citation2010). Informal foster care alumni often in return support their carers through the provision of care, remittances and support throughout their adulthood (Asuman et al., Citation2018). This implies that children in care serve as insurance for their foster parents when they become independent and foster parents also become old.

Reunification in Informal Foster Care

Reunification is a core aspect of the formal foster care process that begins the moment a child is separated from his or her birth parent (Balsells Bailón et al., Citation2018). There are formal guidelines for the formal reunification process including active involvement of parents and child welfare workers who participate in the placement of the child in foster care. The reunification process aims to promote child permanency and wellbeing (Akin, Citation2011; Fowler & Schoeny, Citation2017). However, the variability and flexibility of the motives for the placement of children in informal foster care (Kuyini et al. (Citation2009), suggest that the circumstances for reunification with birth families will vary from those in formal foster care.

Yet, evidence on reunification processes in informal foster care is limited. The growing evidence of children’s maltreatment experiences in formal foster care makes it essential to study practices in informal foster care, including informal foster care reunification. Nnama-Okechukwu et al., (Citation2020) argued that informal foster care created opportunities for child abuse. Hence, reunification with birth parents could be considered protective measures, particularly against cumulative and severe maltreatments meted by informal caregivers. Therefore, understanding reunification processes in informal foster care is a necessary step within the child welfare and alternative care discourse. This study aimed to explore the reunification processes utilized for children who are placed in informal care in Ghana.

Methods

Research Design and Purpose

The study adopted the phenomenological research design to explore the lived experiences of children from informal foster care, who have been reunified with their birth parents. The phenomenological design presents a methodological framework for researchers to make sense of how people experience, feel about, describe, reflect, report and judge a particular phenomenon (Padgett, Citation2016). The approach helped to explore the informal foster care reunification process from the lived experiences of reunified foster care children and their birth parents in the Kumasi Metropolis.

Sample

Children who have been reunified with their birth parents after a period of staying with an informal foster carer were eligible for this study. Also, biological parents, whom the children have been reunified with were included among the eligible participants for this study. The reunified children and their biological parents were recruited based on a community social network strategy. This approach involves recruiting participants through the social networks of the researcher or key informants in the community. Which is an adaptation of the snowball sampling technique. The Snowball technique is particularly useful for recruiting samples from a population that is considered as “hidden” and hard to reach (Heckathorn, Citation2011; Silverman, Citation2013). Although the informal foster care practice is common, the possibility of identifying children who have returned to their birthparents after a short to long-term stay with foster carers is considered challenging (Nnama-Okechukwu et al., Citation2020). Hence, in this study, reunified children from informal foster care were operationalized as a hard to reach population group. However, unlike the traditional snowballing approach, the community-wide social network approach ensured that anyone in the community could assist in the identification of eligible research participants. Therefore, for this study community gatekeepers, such as Assemblymen/women, were involved in the recruitment of participants. In all, 20 participants (10 parents and children) from the Kumasi Metropolis were identified and interviewed for the study. No participant declined to participate in the interview after initial contact and invitation to participate in the interviews.

The 20 participants recruited through the community social network strategy were engaged throughout the research process. They included 10 children and 10 biological parents. The ages of parents and children ranged from 28 to 75 years old and 12 to 17 years old respectively. More so, 6 out of the 10 parents were married with the rest categorized as either divorced or widowed. All the parent participants were also informal workers including farmers, petty traders and casual workers. Six out of the 10 parent participants had no formal education whilst the remaining had primary and Junior High school education. All the child participants except two had at least a minimum of two years of stay in care whereas the longest stay was eight years. The longevity of their care experience is indicative that informal foster care provides stability for some children who require adequate parental care.

Instruments and Procedure

The study employed an in-depth qualitative interview method (with children and parents) using a semi-structured interview guide or instrument. The use of a semi-structured interview guide in qualitative interviews provides researchers with the flexibility and ability to probe participants’ narratives in detail (Rubin & Babbie, Citation2016), which helps to obtain the depth of information required for in-depth analysis. Specifically, questions relating to the processes involved in the reunification of informal foster care children with their birth parents were explored. The in-depth interviews that averaged 40 minutes per interview were conducted with the parents and reunified children using the Twi language (the common local language spoken in the Kumasi Metropolis). The use of the Twi language was a choice made by all participants as that allowed participants to express themselves well. The interviews were conducted between February and April 2021, at the residence of each research participant in Kumasi. Interviews with each respective parent and child were conducted separately. This was to especially allow children to express themselves without the intrusion of their parents. The researchers ensured that privacy was assured at the interview settings. Interviews with participants were recorded for easy transcription. The parents’ interview questions were on how the children were placed with the informal carers and how they were reunited with them. Whilst the children responded to questions on the causes and the processes adopted to reunite them with their birth parents.

Ethical approval was granted by the Departmental Ethics Research Committee of the University. Prior to the beginning of each interview, informed consent was obtained from all research participants, thus written and verbal consents were sought from parents’ whiles accents were granted from child participants. A section of the consent form explained to the participants in this study their right not to answer some questions or withdraw from the interview midway without facing any challenge. Participants were also made aware of the concealment of their identity throughout the entire research process.

Data Analysis

The data analysis procedure followed the reflexive thematic analysis procedure as suggested by Braun and Clarke (Citation2006). Audio recorded interviews were transcribed ad verbatim using Microsoft Word 16. Transcripts were then checked along with interview audios for correctness. Initial codes were developed after researchers engaged in a thorough reading of the transcripts. Codes generated were organized using the NVivo 12 qualitative analysis software. Codes that shared similar meanings were merged to form themes. The themes and sub-themes generated were discussed by both researchers to form the final themes for the study.

Findings

Findings from this research show that the reunification processes in informal foster care are embedded within three pathways/arrangements, namely (1) Open arrangement, (2) Flexible exit plan, and (3) Educational threshold arrangement. Additionally, interfamilial arrangement and participation were identified as important precursors for successful reunification. The findings that were generated from the interview data are presented and supported with quotes from both the reunified children and their birth parents. The findings are presented using pseudonyms to replace the real names of the research participants.

Open Arrangement

The open arrangement highlights a type of informal foster care placement in which there was no mention of when and how the child would be reunified with their birth parents prior to placement. Its openness also underscores the lack of laid down procedures and arrangements for reunification in informal foster care. The findings revealed that children who were sent into informal foster care due to reasons such as foster parents’ loneliness, and biological parents’ poor socio-economic status, had an open arrangement path to reunification.

A parent confirmed that there was no pre-arrangement of reunification prior to her child’s placement into foster care. The parent stated:

“We had no arrangement. The foster parent only said that because the child goes to school, she will pay for her school expenses and that was all. There was no other arrangement between us regarding when she will return and how she will return.” (Parent 8)

The lack of pre-arrangement and laid down procedure regarding when a child could return to stay with their birth parents means that the care arrangement could be truncated, and the child returned to the birth parent at any point in time. A parent supported this surmise:

“No, we didn’t do anything of that sought [no arrangement], so anytime at all that is necessary she could come back to me. And I could order for her to come at any time” (Parent 10)

A major consequence of the open arrangement and the unplanned nature of the care arrangement is that it offers any party (be it the child, the foster parent, or the biological parent) the freedom to initiate termination of the care arrangement and seek for reunification without recourse to any laid down procedure or without any reasonable justification. Description from a parent shows an example of the processes involved in reunification within open arrangement type of informal foster care:

“A food vendor around here offered to let one of my children stay with her so she can relieve me of the burden of taking care of the six children. But later I realized that her care was not the best, so I asked her to come back here because she [fostered child] used to come and complain to me how badly she was being treated at the woman’s place.” (Parent 4)

Comments from other parents indicated that some foster parents also initiate the reunification process within the open arrangement. One parent stated:

“I was here one day when the foster parent brought her back here that my daughter said she won’t stay with them anymore, so they brought her” (Parent 9)

Flexible Exit Plan

In this reunification arrangement plan, children who were placed in informal foster care due to reasons such as: to provide support to foster parents’ businesses and foster parents’ lack of own biological child and child’s desire to experience life in the city, had a flexible exit plan for reunification with birth parents but without exact dates. The reunification period for children who were sent into care to provide “assistance” to the foster parent, in his/her business, was tied to some duration, mostly after the peak business period. A parent reflected on the exit arrangement she had with the foster parent:

“I agreed with her [foster parent] that the child will return to me when the cocoa harvesting period is over. You know that businesses boom during the cocoa harvesting period, so Ekyaa [not the foster child’s real name] went there to support my elder sister in her business. Then after the peak period, she would be made to come.” (Parent 3)

Another parent who had her child sent into informal foster care to be a nanny, commented on the exit plans she had with the foster parent:

“All 4 of her [foster parent] children were between 1 to 8 years, so she requested to have Aku to support her in caring for the children in the home. We agreed that Aku will come back to me after one of her children come of age” (Parent 4)

The comment “may” suggest the existence of a flexible exit procedure for such children in informal foster care where reunification is discussed but with no definite time.

Educational Threshold Arrangement

The interview data revealed that sometimes parents agree on common terminal grounds or threshold for reunification. Such parents often agree that when the child attains certain age or level of education, mostly after completing the Junior High School, they should be reunified. Children in this arrangement type were placed into care for reasons such as education. The child’s education becomes a terminal ground and threshold for reunification. A parent narrated the agreement she had with the foster parent before the child was sent into care.

“Before she went to stay with her [foster parent] we agreed that she will come back when she obtains the Basic Education Certificate Examination (BECE) and the High school placements are out. So, the moment the High school placements came, then she (foster parent) allowed her to come back to continue with the school here.” (Parent 1)

Others believed that by the time the child completes High school, she/he might be of age and would require some time to pursue their career. One parent narrated this way:

“We agreed that she [foster child] return after completing High School. She would be 18 or 19 years by then. And we thought at that age she should have the capacity to make certain life decisions and pursue them. Instead of continuing to receive strict guidance from others.” (Parent 5)

The quotes suggest that, in this study, education, specifically completing Junior or Senior High school, is a common threshold for reunification.

Facilitators of Successful Reunification

Interfamilial Involvement

Narratives from the parents and fostered children showed that the decision to reunify and initiate the process of reunification in the informal foster care arena is not unilaterally made by the caregivers or parents. Instead, informal consultations are sometimes made with other family members, especially those who were stakeholders in the placement of the foster child. A parent described how she went about the reunification process of her child:

“I first informed the sister of the foster parent to tell her [foster parent] to allow my child to come back. So, she informed her to which she also agreed and sent my child back to me. The next morning, I woke up and found my child in the house.” (Parent 2)

Excerpts from the interviews with the children indicated that interfamilial consultations take place when the reunification process is initiated by the foster parents. Comments from two children support the sub-theme of interfamilial stakeholder involvement. One child commented on the role of the family head [abusuapanyin] in the reunification process.

“Before informing me that she [foster parent] wants me to go back to my parents, she called the Family Head to come and talk to me and thank me for coming to stay with her. So, he also came and did that, because he was the one who convinced my parents for me to come here” (Child 3, 15 years old)

Quotes from the parents and the reunified children underscore a multilevel and multifaceted interfamilial involvement. The multifaceted interfamilial involvement is evident in the different kinds of familial engagements carried out by the key stakeholders who have been identified to initiate reunification in informal foster care, namely, the children, the biological parents, and foster parents.

Discussion

This study sought to explore the processes involved in the reunification of children who were placed into foster care informally. This study’s findings revealed three pathways of reunification arrangements (open, flexible and educational) and the facilitators of the reunification. Some parents in this study stated that they did not make any arrangements with the foster parents regarding reunification. The processes of reunification took the form of children leaving care after noticing they are unhappy and/or foster parent sending child back to their parents without any justification. The lack of agreement on reunification procedures makes the informal foster care process and reunification to be contingent on sudden and dramatic events. Existing studies on kinship and informal foster care in Ghana have suggested that the care arrangement is often open and sometimes with no agreement on reunification measures (Abdullah et al., Citation2020; Cudjoe et al., Citation2019). Findings from this study suggest that the lack of arrangements for reunification opens the care process and grants all stakeholders (foster parents, biological parents and foster children) the capacity to initiate reunification anytime.

Essentially, the sudden and disorganized nature of the reunification may have child protection implications. Children reunified following experiences of maltreatment may have hidden traumatic experiences to be addressed. This becomes more profound when reunification is triggered by adverse childhood experiences. Also, it affects children’s emotional stability, especially for children who may have established strong connections with the foster parent. The sudden nature of removing children affects a child’s permanency in care (Akin, Citation2011; Winokur et al., Citation2009). Undoubtedly, the reunification procedure in the open arrangement form of informal foster care contradicts the laid down procedures for reunification in the formal foster care system (Balsells et al., Citation2015; Cheng, Citation2010; López et al., Citation2013).

Children who were sent into care purposely to support the foster parent (including helping the foster parent’s business) were found to have flexible exit plans between the foster and biological families. The arrangements involved the child returning to the birth parent after the conditions for their placement are met. Outlining conditions for reunification are a key procedure of reunification in formal foster care (Carlson et al., Citation2020; Fernandez et al., Citation2019). Findings from this study, however, showed different exit conditions which are often not satisfied as the placement truncates suddenly due to the maltreatments of foster children. In some cases, the fostered children truncate the care process by running back to their biological parents for safety. Children’s ability to truncate their care and reunify with their birth parents indicates their agency (Abebe, Citation2019; Berthelsen & Brownlee, Citation2005) and empowerment (Wong et al., Citation2010) to resist maltreatment. However, it emerged that agency is linked with longevity in care, as children who spent a minimum of four years in care demonstrated agency.

Reunification procedures for children whose placements were motivated by typical child welfare issues such as acquiring an education were found to be terminal. This implies that within informal foster care, children are conditioned to return after they have successfully completed their education. These reunification procedures could be termed as an educational threshold arrangement because it is conditioned on common thresholds including children completing junior high school or acquiring a skill.

For a placement that had to be curtailed, it was also found that regardless of the sudden nature of the reunification process, the processes entail the involvement of key stakeholders in the family. Stakeholders who were involved in the placement processes are in most cases informed or consulted before reunification is taken place. The finding confirms the need to have open and broad consultation before reunification is effected (Balsells Bailón et al., Citation2018). However, the familial involvement undertaken by participants in the study is not tantamount to the assessment-based collaborative engagements in formal child protection practices (Fernandez et al., Citation2019) since the stakeholders are only informed of the reunification. Also, the stakeholders often have no opportunity to contribute and alter the decisions of the one initiating the reunification. This is understandable given that the reunification process is often swift and sudden which gives no room for detailed/broad consultations to ensue. Collaboration and consultation among families will positively impact the welfare of children as it could lead to the development of proper informal care plans (Carlson et al., Citation2020) and follow-up measures (Biehal et al., Citation2015).

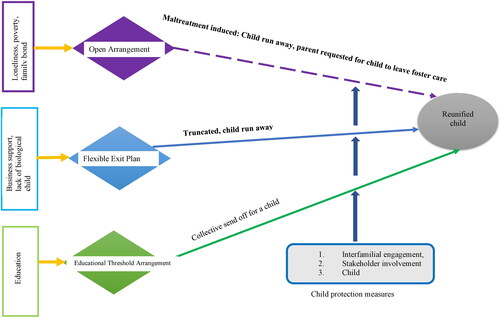

A Conceptual Model of Reunification in Informal Foster Care

Based on the study findings, it was deemed necessary to develop a conceptual framework to capture the reunification process in informal foster care to provide a working framework for further research and practice.

shows the open, flexible exit plan and educational threshold, herein the OFE framework and its associated pathways.

Implications for Practice

This study has highlighted the varied reasons for placing children in informal foster care and the different pathways to reunification. The open reunification process and procedures show that reunification may be silent in some informal foster care arrangements. The lack of attention on reunification contradicts standard alternative child care practices, which often mandate children to return to their primary caregivers to achieve permanency. The child welfare objective of achieving permanency may still be achieved in the open arrangement when the children spend their childhood with a single caregiver. Therefore, child welfare workers examining child permanency in informal foster care should consider the possible effects of open arrangements. Further, children in open arranged placements may have an unplanned and sudden reunification, as evident in this study. The unprepared nature of the reunification process could increase negative outcomes for children, after reunification. Therefore, care should be taken by child welfare workers when addressing concerns of children who experience an open reunification process.

Both the flexible and educational threshold reunification paths are closer to the expected reunification processes in foster care. They highlight the fact that reunification is a standard requirement for children who are sent into foster care. However, the lack of a standard documented process regarding how the child would be reunified after placement goals are achieved or when terminal thresholds are met, opens the process to a lot of irregularities and knee-jerk decisions. Yet, the presence of exit plans and terminal thresholds that are based on child welfare concerns signify a beginning point that should be considered by child protection professionals when conducting educational programs. Also, the acknowledgement of threshold measures for reunification makes it possible for an adequate and consultative reunification process to take place. Particularly, it provides a plan for which children can participate and have their voices heard.

Limitation

This study has some limitations. The sample size of 20 participants is not adequate to draw statistical inferences or generalizations from the findings. Yet, 20 participants for an in-depth qualitative study are adequately powered to provide analytic insight into the phenomenon. We recruited children and their birth parents, whom they have reunified with. Engaging the foster carers may deepen the study findings and reveal nuances into the processes of informal foster care reunification as well as the facilitators of successful reunification. Second, the study findings are limited to the Ashanti culture and the Ghanaian contexts. Furthermore, studies from other cultural contexts are desired to deepen the study findings.

Conclusion

The cultural underpinning of informal foster care in Ghana indicates an important fabric within alternative care. Unlike the formal foster care process, little is known about the reunification process in informal foster care. This study explored the processes of informal foster care reunification through interviews with reunified children and their birth parents. It is evident that in most cases placements within informal foster care do not involve arrangements for reunification. At best, certain conditions or thresholds, mostly educational attainment, are considered the benchmark for reunification. The model for reunification, which has been developed based on the three common pathways for reunification, provides a useful framework, which can be used by formal child protection workers to design interventions that will gear toward the formalization of the reunification processes to ensure better outcomes for children. Researchers can utilize the framework as a tool to examine the outcomes for children who have been reunified following the three unique pathways. Further research can also focus on the triggers of reunification for each unique pathway and explore the mechanisms that are needed to realize the child protection intentions of reunification in foster care.

Disclosure statement

The authors report there are no competing interests to declare.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Abdullah, A., Frederico, M., Cudjoe, E., & Emery, C. R. (2020). Towards culturally specific solutions: Evidence from Ghanaian Kinship caregivers on child neglect intervention. Child Abuse Review, 29(5), 402–415. https://doi.org/10.1002/car.2645

- Abdullah, A., Cudjoe, E., & Manful, E. (2018). Barriers to childcare in Children’s Homes in Ghana: Caregivers’ solutions. Children and Youth Services Review, 88, 450–456. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2018.03.045

- Abdullah, A., Cudjoe, E., & Manful, E. (2020). Creating a better kinship environment for children in Ghana: Lessons from young people with informal kinship care experience. Child and Family Social Work, 25(S1), 207–214. https://doi.org/10.1111/cfs.12764.SSCI

- Abebe, T. (2019). Reconceptualising children’s agency as continuum and interdependence. Social Sciences, 8(3), 81. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci8030081

- Akin, B. A. (2011). Predictors of foster care exits to permanency: A competing risks analysis of reunification, guardianship, and adoption. Children and Youth Services Review, 33(6), 999–1011. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2011.01.008

- Ansah-Koi, A. A. (2006). Care of orphans: Fostering interventions for children whose parents die of AIDS in Ghana. Families in Society: The Journal of Contemporary Social Services, 87(4), 555–564. https://doi.org/10.1606/1044-3894.3571

- Ardington, C., & Leibbrandt, M. (2010). Orphanhood and schooling in South Africa: Trends in the vulnerability of orphans between 1993 and 2005. Economic Development and Cultural Change, 58(3), 507–536. https://doi.org/10.1086/650414

- Asuman, D., Boakye-Yiadom, L., & Owoo, N. S. (2018). Understanding why households foster-in children: Evidence from Ghana. African Social Science Review, 9(1), 6.

- Balsells, M. À., Pastor, C., Mateos, A., Vaquero, E., & Urrea, A. (2015). Exploring the needs of parents for achieving reunification: The views of foster children, birth family and social workers in Spain. Children and Youth Services Review, 48, 159–166. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2014.12.016

- Balsells Bailón, M. À., Mateos Inchaurrondo, A., Urrea Monclús, A., & Vaquero Tió, E. (2018). Positive parenting support during family reunification. Early Child Development and Care, 188(11), 1567–1579.

- Berthelsen, D., & Brownlee, J. (2005). Respecting children’s agency for learning and rights to participation in child care programs. International Journal of Early Childhood, 37(3), 49–60. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03168345

- Biehal, N., Sinclair, I., & Wade, J. (2015). Reunifying abused or neglected children: Decision-making and outcomes. Child Abuse & Neglect, 49, 107–118. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2015.04.014

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. [Database] https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Bywaters, P. (2019). Understanding the neighbourhood and community factors associated with child maltreatment. In B. Lonne, D. Scott, D. Higgins, & T. I. Herrenkohl (Eds.), Re-Visioning Public Health Approaches for Protecting Children (1st ed., pp. 269–286). Springer.

- Carlson, L., Hutton, S., Priest, H., & Melia, Y. (2020). Reunification of looked-after children with their birth parents in the United Kingdom: A literature review and thematic synthesis. Child & Family Social Work, 25(1), 192–205. https://doi.org/10.1111/cfs.12663

- Cheng, T. C. (2010). Factors associated with reunification: A longitudinal analysis of long-term foster care. Children and Youth Services Review, 32(10), 1311–1316. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2010.04.023

- Child Welfare Information Gateway. (2020). Supporting Reunification and Preventing Reentry Into Out-of-Home Care. Washington, U.S.: Department of Health and Human Services, Children’s Bureau. Retrieved from https://www.childwelfare.gov/pubPDFs/srpr.pdf—Google Search. (n.d.). Retrieved May 26, 2020

- Connolly, M., & Katz, I. (2019). Typologies of child protection systems: An international approach. Child Abuse Review, 28(5), 381–394. https://doi.org/10.1002/car.2596

- Cudjoe, E., Abdullah, A., & Chiu, M. Y. L. (2019). What makes kinship caregivers unprepared for children in their care? Perspectives and experiences from kinship care alumni in Ghana. Children and Youth Services Review, 101, 270–276. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2019.04.018

- Darkwah, E., Daniel, M., & Asumeng, M. (2016). Caregiver perceptions of children in their care and motivations for the care work in children’s homes in Ghana: Children of God or children of white men? Children and Youth Services Review, 66, 161–169. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2016.05.007

- Deininger, K., Garcia, M., & Subbarao, K. (2003). AIDS-induced orphanhood as a systemic shock: Magnitude, impact, and program interventions in Africa World Development, 31(7), 1201–1220. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0305-750X(03)00061-5

- Fernandez, E. (2014). Child protection and vulnerable families: Trends and issues in the Australian context. Social Sciences, 3(4), 785–808. https://doi.org/10.3390/socsci3040785

- Fernandez, E., Delfabbro, P., Ramia, I., & Kovacs, S. (2019). Children returning from care: The challenging circumstances of parents in poverty. Children and Youth Services Review, 97, 100–111. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2017.06.008

- Fowler, P. J., & Schoeny, M. (2017). Permanent housing for child welfare-involved families: Impact on child maltreatment overview. American Journal of Community Psychology, 60(1–2), 91–102. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajcp.12146

- Gypen, L., Vanderfaeillie, J., De Maeyer, S., Belenger, L., & Van Holen, F. (2017). Outcomes of children who grew up in foster care: Systematic-review. Children and Youth Services Review, 76, 74–83. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2017.02.035

- Heckathorn, D. D. (2011). Comment: Snowball versus respondent-driven sampling. Sociological Methodology, 41(1), 355–366. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9531.2011.01244.x

- Kuyini, A. B., Alhassan, A. R., Tollerud, I., Weld, H., & Haruna, I. (2009). Traditional kinship foster care in northern Ghana: The experiences and views of children, carers and adults in Tamale. Child & Family Social Work, 14(4), 440–449. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2206.2009.00616.x

- López, M., Del Valle, J. F., Montserrat, C., & Bravo, A. (2013). Factors associated with family reunification for children in foster care. Child & Family Social Work, 18(2), 226–236. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2206.2012.00847.x

- Manful, E., Umoh, O. & Abdullah, A. (2020). Examining welfare provision for children in an old relic: Focusing on those left behind in residential care homes in Ghana. Journal of Social Service Research, 46(6), 825–836. https://doi.org/10.1080/01488376.2019.1670322

- Nnama-Okechukwu, C., Agwu, P., & Okoye, U. (2020). Informal foster care practice in Anambra State, Nigeria and safety concerns. Children and Youth Services Review, 112, 104889. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2020.104889

- Nukunya, G. K. (2016). Tradition and change in Ghana: An introduction to sociology (Rev). Woeli Publishing Services.

- Padgett, D. (2016). Qualitative methods in social work research (3rd ed.). SAGE Publications, Inc.

- Rubin, A., & Babbie, E. R. (2016). Empowerment series: Research methods for social work. Cengage Learning.

- Silverman, D. (2013). Doing qualitative research: A practical handbook (4th ed.). SAGE Publications Ltd.

- Ushie, B. A., Osamor, P. E., Obieje, A. C., & Udoh, E. E. (2016). Culturally sensitive child placement: Key findings from a survey of looked after children in foster and residential care in Ibadan, Nigeria. Adoption & Fostering, 40(4), 352–361. https://doi.org/10.1177/0308575916667672

- Winokur, M., Holtan, A., & Valentine, D. (2009). Kinship care for the safety, permanency, and well-being of children removed from the home for maltreatment. The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 1, CD006546. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD006546.pub2

- Wong, N. T., Zimmerman, M. A., & Parker, E. A. (2010). A typology of youth participation and empowerment for child and adolescent health promotion. American Journal of Community Psychology, 46(1–2), 100–114. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10464-010-9330-0