Abstract

While the number of older people living with dementia grows, savings in public resources leads to situations where services and supports for older people are cut, even in the traditionally generous Nordic welfare states, such as Finland. This development is expected to lead to care poverty, meaning older people are not receiving the services they need. Our aim was to uncover whether care poverty already exists within institutional care for older adults in Finland. Thematic analysis was utilized to study 19 interviews with family members of people with dementia living in a nursing home. Signs of care poverty were found in relation to timeliness and safety of access to long-term care and quality of professional care. In addition, the threshold of questioning the care system was high, and managing disagreements about care with professionals was challenging for the family members. The results raise concerns that reducing long-term care risks the whole concept of welfare states. Family members should be more systematically involved in needs assessment and decision-making concerning the care of older people with dementia.

Introduction

Aging societies are facing challenges regarding sufficient provision of care for older citizens, especially persons living with dementia. There are around 9.8 million people living with dementia in Europe (Alzheimer Europe, Citation2019). This is expected to rise as the population ages—the number of people living with dementia in the European Union (EU) is expected to reach 14.3 million in 2040 (OECD/European Union, Citation2018). While number of people aged 85+ is expected to more than double in Finland between 2022 and 2040 from 159,114 to 340,640 (Finnish Institute for Health and Welfare, Citation2023), the number of people with dementia will grow from about 150,000 to 247,000 simultaneously (National Institute for Health and Welfare, Citation2024). This rise in numbers has resulted in even northern European welfare states, such as Finland, moderating their principles on universality of social and health care services (Szebehely & Meagher, Citation2018). Austerity of common resources has already resulted in lower coverage of services for older people (Finnish Institute for Health and Welfare, Citation2023), and the future of care for older people is currently under lively public discussion in Finland. The discussion centers around the urgent demand to increase the number of care professionals working with older people, but both the available work force and money to hire them are lacking.

When a person is living with advanced dementia, their everyday care needs are substantial and it is known that in all cases these care needs are not met. Teppo Kröger (Citation2022) has constructed a concept of care poverty that combines gerontological studies on the unmet needs of older people; sociological and social policy studies on structures of the welfare state; feminist social policy approach on care and care deficits; and poverty and inequality research’s viewpoint on deprivation. Kröger’s concept identifies three domains of care poverty: personal, practical, and socio-emotional. Personal care poverty concerns limitations in functional abilities and makes use of the scale of Activities of Daily Living (ADLs, such as eating, dressing, and using the toilet) used in gerontological research, while practical care poverty is based on Instrumental Activities of Daily Living (IALDs, such as transportation and managing medication) (see e.g. Lima & Allen, Citation2001). Socio-emotional care poverty, on the other hand, concerns unsatisfied social and emotional needs of belonging and connecting to others. While some studies have focused on absolute care poverty which refers to the full absence of care, in this study we utilize Kröger’s (Citation2022, pp. 47–51) concept of relative care poverty, which refers to insufficient care or care that does not correspond with the care recipients’ care needs. Our aim is to investigate whether, from the perspective of family members, older adults living in Finnish nursing homes receive professional care that is mistimed, insufficient, or of poor quality.

According to previous research, family members’ supporting role increases as dementia advances. Gradually, helpers become carers when responsibility for the wellbeing of the person with dementia shifts to family members (Huang et al., Citation2015). While taking care of the person with dementia may provide family members with experiences of personal accomplishment and strengthening relationships, it also increases their emotional burden and eventually care burden (Lindeza et al., Citation2020; Teahan et al., Citation2021). Informal caregivers are the main providers of care and services for people with dementia along the dementia trajectory (Lethin et al., Citation2016). In Finland, of those that have an official status as a family carer, more than a half take care for a person with dementia (Ministry of Social Affairs and Health, Citation2019).

Even after the transfer to a nursing home, family members offer various support to persons with dementia. They contribute to maintaining a sense of personhood, assist with care, and act as advocates for people with dementia (Verbeek, Citation2017). They can also be a huge support to the staff by noticing signs of changes in their loved ones’ health and informing care staff about these (Powell et al., Citation2018). In addition, family members monitor the quality of institutional care while visiting (Duggleby et al., Citation2013), especially when their loved one is living with dementia (Graneheim et al., Citation2014). Sometimes family members participate in care specifically because they are unhappy with the quality of professional care (Duggleby et al., Citation2009; Roberts & Ishler, Citation2018). In addition to residents’ loneliness and lack of socioemotional support (Ekström et al., Citation2019), the family members worry about lack of stimulation and activity for the resident, updating practices, and the involvement of families in care planning and decision-making (Givens et al., Citation2012; Jakobsen et al., Citation2019). Some of these worries may be connected to family members’ feelings of guilt regarding their relatives’ transfer from a private home to a care facility (Sury et al., Citation2013). However, the concerns may also be indicators of real insufficiency of formal care as family members’ satisfaction ratings of nursing home care have been shown to be higher than the ratings given by the residents (Castle, Citation2006). Family members’ observations of low care quality can also indicate poor family involvement in care, as family member support and involving family members in decision-making are associated with high-quality ratings of care (Voutilainen et al., Citation2006).

The transfer to a nursing home should always be made as safe as possible, since it can be a very stressful situation for older adults in terms of sense of control and lack of influence in one’s own life (Boström et al., Citation2017; O’Neill et al., Citation2020). Where people with dementia are concerned, admission to a nursing home has been linked to increased behavioral symptoms and in particular depression and agitation, decreasing cognition, frailty, and falls (Sury et al., Citation2013). In addition to safety, timeliness of the transfer has been found important. Successful timing of the transfer entails proper planning and preparations of the concrete move as well as drafting and executing detailed tripartite care plans involving the care recipient, their family members, and care professionals (Groenvynck et al., Citation2021).

The Finnish law on supporting functional abilities of older individuals states that health and social services must correspond with the person’s current service needs. Finnish wellbeing services counties must provide long-term care based on medical grounds and reasons connected to patient safety, and they are also obliged to secure constancy of long-term services. (Act on changing the Act on Supporting the Functional Capacity of the Older Population and on Social and Health Care Services for Older Persons 604/Citation2022, 14 §, 14a §.) The Finnish Ministry of Social Affairs and Health (Citation2020) list safety, constancy, individuality, reliability, and professionality of care as principles of implementation of care, and recommend a customer-oriented approach that also involves family members in care planning.

In this study, we will examine family members’ views of timeliness and safety of access to long-term care as well as their perceptions of unmet care needs in long-term care. In addition, we illustrate family member’s opportunities to affect care in situations in which they disagree with healthcare professionals. Although politicians and decision-makers picture informal care as a solution to the austerity problem, we argue that family members are already bearing responsibility for care to excess, and that their views on the care recipients’ well-being, and their own well-being, do not receive enough attention.

Research questions

Our research questions were:

How do family members of people with dementia experience the quality of transition from home to long-term care facilities, such as nursing homes, specifically in regards to the timeliness of the process of transition and safety of care recipients?

How do the family members perceive the quality of care provided by healthcare professionals in the facilities considering the care needs of the care recipients?

If the family members have perceived the professional care as insufficient and disagree with the care decisions, how have they managed the situation with healthcare professionals?

Method

The research was conducted using inductive thematic analysis as the method (Braun & Clarke, Citation2006, Citation2019). Thematic analysis is a rigorous and theoretically flexible method for analyzing qualitative data, and therefore suited our purpose of analyzing interviews. The analysis was driven by the research team’s interest in the themes of unmet care needs and care poverty of people with late stage dementia, but the specific research questions (see above) were formed through coding both the semantic and latent content of the data set broadly.

Data

The data consists of telephone interviews conducted in March–May 2021 with 19 family members of people with dementia who had lived in a nursing home. Each family member was interviewed once. The interviews’ average duration was about 46 min, resulting in 872 min in total. The interviews were audio recorded and then transcribed verbatim by an external commercial enterprise, carrying out a strict privacy policy.

The interviewees were recruited based on a prior COVID-19 related survey targeted to nursing home residents’ family members (Pirhonen et al., Citation2022). In the survey, participants were asked if they were willing to give an additional interview about their experiences on nursing home care and they were able to provide their phone numbers. A list was formed of the phone numbers received, and the first ten persons were contacted and interviewed. After this, we evaluated the sufficiency of the data and decided to double it to make sure it covered all our future research interests. Eventually, nine additional persons from the list were contacted and interviewed. All the contacted persons were willing to give an interview. In seven of the interviews, the care recipient had died after the family member had taken the survey in May–June 2021. The interviews were conducted a year after the COVID-19 lockdown occurred in March–June 2020 in nursing homes. In addition to exploring the effects of the lockdown, family members’ experiences regarding their loved ones’ care earlier and currently were discussed widely. In this research, our interest was not on the influences of the pandemic in nursing homes but on family members’ perceptions of care services at ‘normal’ times. Thus, we were especially interested in questions regarding the transfer to a nursing home as well as the perceived quality of care there outside the lockdown period (see Appendix 1 for interview questions).

Participants

Twelve of the interviewees were adult children of the care recipient, and seven were spouses. The vast majority of the interviewees, 17 out of 19, were female, which was expected as most of the residents’ visitors in nursing homes are female, especially daughters and wives (Holmgren et al., Citation2013), and because females are also overrepresented among informal carers (Kröger, Citation2022). All the discussed nursing home residents had been transferred there due to dementia.

Defining the Main Themes

The thematic analysis was completed in six phases (Braun & Clarke, Citation2006, p. 87): (1) close reading and noting down initial ideas, (2) systematic coding of all interesting features, (3) searching for themes, (4) reviewing themes, (5) defining and naming themes, and (6) reporting and selecting data extracts. Postdoctoral researcher Paananen coded the data with NVivo 12 Plus software. Paananen, Pirhonen, and Kulmala reviewed the codes and the themes together, and finally the whole research team participated in defining and reporting the results.

The coded passages of data varied in length: They could consist of a single utterance or even several turns of talk that formed a continuous narrative, and several codings could be assigned to one passage (see ). Although in thematic analysis, the main themes are not defined by the quantity of items within the theme but rather on whether the theme captures something relevant in relation to the research questions, we have given exact numbers of interviews containing the code in order to describe the distribution of certain codes truthfully in the analysis section.

Table 2. Example of a data extract, with codes applied.

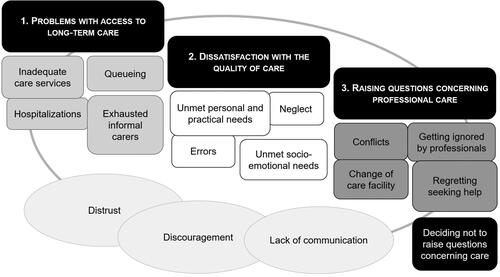

Problems with access to long-term care, dissatisfaction with the quality of professional care and raising questions concerning professional care were chosen as the main themes. Firstly, by analyzing family members’ experiences on the transition to long-term care, our goal was to assess the aspects of timeliness and safety from the lay perspective, which is often overshadowed by institutional processes and professional evaluations. A comprehensive understanding of the transition process is necessary, as access to formal care goes hand in hand with low rates of care poverty (Kröger, Citation2022).

Secondly, by focusing on family members’ dissatisfaction with nursing home care, our aim was to highlight family members’ life-world perspective on the quality of care and to contemplate whether the problems identified by the family members can be seen as reflections of relative care poverty within the formal care system despite its’ high standards. Finally, we decided to focus on family members’ narratives on raising questions concerning professional care, as the theme illustrated the family members’ opportunities to intervene when the care seemed insufficient. Especially in the context of late stage dementia care, being able to negotiate with the nursing professionals is essential in order to plan the care so that it respects the care recipient’s views and wishes. Therefore, knowledge on how disagreements between family members and nursing home staff are managed is needed to improve collaboration.

Ethical Considerations

Ethical approval for the research was obtained from the Research Ethics Committee in the Humanities and Social and Behavioral Sciences at the University of Helsinki, and the Finnish ethical guidelines for research (Finnish National Board on Research Integrity, Citation2023) were followed accurately. Participation in the study was voluntary. Before giving their consent orally, the participants received information about the research, recording of the interviews, data protection, and anonymity. The participants’ consent was audio recorded before starting the interview. Pseudonyms are used to identify the participants in the extracts presented in this study. The presentation of the findings was guided by the Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ) checklist.

Results

The main results of the thematic analysis are presented as a thematic map ().Footnote1 In the next sections, we will summarize our findings on the family members’ views on the three main themes (1) problems with access to long-term care, (2) dissatisfaction with the quality of professional care, and (3) raising questions concerning professional care. Our focus is on the problems connected to long-term care in nursing homes, but we have also analyzed family members’ narratives of hospitalizations of the person with dementia that were connected either to the access to long-term care or to events in a long-term care facility, as hospitalizations were identified as a recurring theme in the interview data.

Distrust, discouragement, and lack of communication were identified as overarching sub-themes that hindered family member involvement in nursing home care and care planning. Family members’ negative perceptions of care provision, care quality, and decision-making reduced their trust in care professionals and the whole care system, and distrust was often accompanied with experiences of lack of communication and feelings of discouragement. We will demonstrate this in more detail in the next sections and return to this in the conclusion.

Main Theme 1: Problems with Access to Long-Term Care

Ideally, the transition to long-term care in a nursing home comes as the result of careful evaluation of the care needs of the care recipient. In other words, a person who is considered to need substantial care in order to live a safe and healthy life should be eligible for a place in a care facility, and the transition should be timely so that no harm is caused by not meeting the existing care needs. Our interviews, however, illustrate a different reality, where access to long-term care is the last choice after all other solutions are deemed inadequate. Thus, the transition not only depended on the care needs of the person with dementia but also actualization of serious incidents or other imperative conditions that proved that the minimum standards of care were not met by other professional care services and/or informal carers.

Risky Conditions and Queue Management in Accessing Long-Term Care

Ten out of nineteen interviewees disclosed that a place in a nursing home was organized after one or several hospitalizations of the care recipient with dementia. Some had a fall and lost their mobility, whereas others were taken to hospital repeatedly due to serious delusions, confusion, and getting lost (see Excerpts 1 & 2).

Excerpt 1.

Kirsi (daughter): “She fell on the stairs at home, and was paralyzed from the waist down. So she was in the hospital and had an operation, and then she was in the rehabilitation hospital. And after that, the transition ((to a nursing home)) was clear. That there was absolutely no way that she could manage at home, living alone with a cat."

Excerpt 2.

Seppo (son): “It ((the transition to a nursing home)) felt necessary. He could no longer manage at home, so there were no options. It was kind of a relief as well, because he had to lay in hospital all the time. He was constantly taken to the hospital and brought back home again.”

Seppo’s father got a placement in the nursing home as soon as there was an opening. According to Finnish law (Act on Supporting the Functional Capacity of the Older Population and on Social and Health Care Services for Older Persons 980/Citation2012, 18 §) the waiting period for a position in long-term care should be three months at maximum after receiving a favorable decision from the local authorities, but the waiting period can be longer, if “the investigation for any reason the demands more time”. This means that in addition to increased care needs and actualized threats to the care recipient’s safety, prerequisites for accessing long-term care include that the process in itself is smooth and that there is room in the care facilities, which may take some time due to the growing number of old people in society.

Exhausted Informal Carers

Half of the family members (10/19) talked about the exhaustion experienced by informal carers before getting a place in a nursing home for the care recipient. From their viewpoint, the care needs of the care recipients were substantial and evident, yet they were expected to manage with little professional support such as home help service and institutional respite care until the need for long-term care was officially decided and an available place in a nursing home was found. The family members consistently described the last months or weeks before the transition as tough. For example, Elli confessed taking her husband with her everywhere, even to work, so that he would not have to be home alone. Eventually, while waiting for a placement for her husband, Elli became so exhausted that she found no other solution but to take her husband to the hospital emergency department so that the responsibility of his care would be on someone else, even if for a little while.

In fact, in three cases, a permanent place in a nursing home was eventually acquired not due to the poor condition of the care recipient but of the spouse who acted as their informal carer. Kauko had applied for a placement for his wife, but while waiting for a place his wife’s condition deteriorated to the extent that it took three people to take care of her, and he had to help the care assistants with lifting. Eventually, Kauko had a heart attack:

Excerpt 3.

Kauko (husband): “At times I had to go lift her off the toilet as they ((care assistants)) could not manage on their own. In the end, the transition to the nursing home was sudden because I… I had such burning, such intense pain. At two at night I called myself an ambulance and I called my oldest son to wake him up at night. And he arranged another ambulance to take my wife to a care facility.”

Table 1. Sample characteristics.

Main Theme 2: Dissatisfaction with the Quality of Professional Care

In comparison with narratives on access to long-term care, narratives on the quality of care, once a placement was acquired, were more clearly divided, which reflects the fact that the process of access to care is quite similar to all whereas the realization of care is more dependent on the individual units within the care home. Twelve of the interviewees had at least some concerns about the care, ranging from continuous worries about unmet care needs to single events of neglect. We will analyze the accounts of dissatisfaction more closely in the next sections, as they can be interpreted as reflections of relative care poverty. However, it is important to acknowledge that almost half of the interviewees (7/19) expressed satisfaction with the care and believed that the care recipient was also content. For example Kirsi, whose mother was transitioned after being paralyzed (Ex. 1), experienced a huge relief and considered the nursing home as the best possible place for her mother:

Excerpt 4.

Kirsi (daughter): “She gets the best possible care there is, and us family members can feel relieved. I mean, it started to be so worrying in the home environment despite the home care visits. Her dementia caused that she took medications on her own and there were pills on the floor and all that. Food in the fridge was untouched. (…) Indeed, I cannot imagine a better place than where she is now.”

Unmet Personal and Practical Needs

The biggest worry for the family members was caused by the negative consequences of unmet personal care needs, such as the person with dementia wetting or soiling themselves and getting hurt due to lack of support in moving around. For example, Riitta said that her mother was showered only once a month due to lack of staff and smelled awful. Elli’s husband was not showered in weeks because he was unwilling. Mirja’s husband had been tied down for ten months without having a doctor’s written license for physical restriction, which is compulsory in Finland.

However, more often family members disclosed single errors and individual cases of neglect that had caused them to doubt the quality of care. This type of narratives also highlighted unmet practical care needs connected to instrumental activities of daily living such as transportation and managing visits to acute care. For example, Mari’s mother had fallen out of a wheelchair despite having a formal decision to use a safety belt, which resulted in a cut on her head. Riitta’s mother had been sent out to a health center to see a doctor on her own after hurting her leg despite her apparent need for assistance:

Excerpt 5.

Riitta (daughter): “You see, my mother, who is transported in a wheelchair most of thetime and who has no idea of who she is and cannot say anything else but “mom” anymore. They put her in a wheelchair and in a taxi, and sent to the health center. Alone. With nothing, with no one. No one. In the health center, they could not do anything, so they had to send her to the central hospital of the area, which is even further away. Again, they put her alone in a taxi. She waited eight hours in the emergency duty. They didn’t even give her a glass of water. (…) Her diapers were soggy and leaked through, nobody changed her. I called there three times, but they just said it is not part of their job description.”

Unmet Socio-Emotional Needs

In terms of socio-emotional needs of the care recipients, half of the interviewees (10/19) were content that there were opportunities for meaningful activities such as joint exercises, music, and parties in the nursing home. Some of the family members (4/19) also felt that the transition to long-term care increased the social contacts of the care recipient, as there were more people around for the person with dementia to spend time with, and more activities to take part in than at home. However, half of the family members nevertheless conveyed the opposite (9/19): the possibilities for activities in the nursing home were scarce or nonexistent, visits from friends and family had become less frequent, and the transition prevented the care recipients from maintaining their hobbies and participating in social gatherings outside the nursing homes. Having dementia could also increase the care recipients’ experiences of loneliness due to being unable to remember family members’ visits.

A major factor that affected social connections in nursing homes was the Covid-19 pandemic. Even though the official restrictions concerning family members’ visits in nursing homes had been lifted during the previous year, many facilities had established new guidelines for visiting that were more restricted than before and ceased to arrange leisure time activities. A majority of the family members (15/19) had experienced the contact with the care recipient as difficult or insufficient due to the effects of the Covid-19 pandemic. This could also limit the family members’ possibilities to monitor the care as well as the care recipient’s satisfaction, which made it difficult for some of the interviewees to evaluate how well the needs of the care recipients were met.

Another noteworthy finding was that some family members interpreted the care recipient’s passivity and withdrawal as personality traits rather than consequences of dementia or unmet socio-emotional needs. Four family members deemed that the care recipient deliberately avoided the company of others and wanted to be left alone. Seppo, for example, described his father as someone who “enjoys being on their own, surrounded by their own thoughts,” while Tiina explained that it is her mother’s choice to not participate in social activities. In these cases, family members perceived the care recipient as lonely and passive but also believed that they were content with their life in the nursing home.

Main Theme 3: Raising Questions Concerning Professional Care

In total seven of the interviewees had experiences of handling disagreements on care with healthcare professionals. The arguments concerned medication, isolation and social distancing during the Covid-19 pandemic, neglect, poor hygiene, transition decisions to another unit, and diet. Some of the interviewees identified more than one problem.

Prolonged Conflicts and Getting Ignored by Healthcare Professionals

As we anticipated, managing disagreements was experienced as straining: the family members described the negotiations with the professionals as debates and fights. Another common feature in the narratives was that the issues persisted: the family members confronted the professionals several times on the same matter. Some had acquired another expert opinion to support their view, while others tried to improve the care by treating the care recipient by themselves or by buying care products for the care unit.

For Inkeri, the path of their family members’ dementia journey was figuratively paved with conflicts with healthcare professionals. Before the transition to long-term care, Inkeri’s husband had been hospitalized. During the hospital stay, he had first wandered outside at night in his underwear in a freezing temperature and later had a fall, breaking his hip, due to insufficient surveillance. Inkeri was not informed about these incidents until she called the hospital to ask how her husband was doing, which gave her the impression that professional carers could not be trusted. After her husband got a placement in a nursing home, Inkeri continued to monitor his care closely, and encountered more faults in both his care and hygiene.

On one visit, Inkeri noticed that her husband could not walk properly and that he was clearly in pain. There was bruising and a small cut on his knuckles. Inkeri confronted the nursing staff, who initially denied the possibility that he could have fallen. Later, however, one of the nurses found more bruises around his body, and moreover, it was discovered that the alarm bell on his wrist had been connected to the wrong room. This meant that for over a year, Inkeri’s husband’s calls for help had been in vain. On another visit, Inkeri witnessed a nurse offering an inhalable medication for her husband to swallow as a whole capsule and intervened just in time. This time Inkeri complained not only to the nursing home management but to the local municipality responsible for care homes as well, but the incident was deemed as a misunderstanding on behalf of Inkeri.

Excerpt 6.

Inkeri (wife): “They lie. The municipality sent me an answer that stated that the nurse was not going to give the medication orally. (…) They twist and bend everything as they please. And the municipality just repeats these lies.”

Change of Care Facility

Despite the difficulty in doing so, three of the interviewees had eventually gone through the process of moving the care recipient to another care unit due to mistrust. Unfortunately, even this had virtually no effect on the care of one of the care recipients, since the new unit was soon merged with the previous one:

Excerpt 7.

Riitta (daughter): “No, I am not happy with the care and have not been happy this whole time. That is why I changed the care unit, but it went badly. I changed to a completely different company, I mean, he is in private care, and I switched to an entirely different service producer. For a year and a half, thing were great until the company I had just took my mother away from, bought ((laughs)) this new company I had switched to. Out of the frying pan, into the fire, so to speak.”

Deciding Not to Raise Questions and Regretting Seeking Help

Overall, the threshold of questioning the care system was high for family members. Accordingly, even though there was an apparent lack of communication and growing suspicion concerning the care not meeting the care needs, some family members trusted the care system to the extent that they had decided to not raise questions concerning the quality of care. In this way, they could avoid the burden that comes with managing disagreements, although at the same time that meant that the care recipient was left in an unsatisfactory and potentially harmful situation.

What is notable is that even those who did raise questions and demanded changes in care could regret doing so. After everything that happened, Inkeri lost her trust in the whole care system and regretted agreeing with her husband’s transition to long-term care in the first place. Elli, too, felt remorse for her decision to seek help during a tough phase. Her husband was heavily medicated during a temporary hospitalization and lost his abilities to speak and walk for a period. In her own words, Elli fought outrageously hard to get the doctors to discontinue her husband’s medication, but it was not until after the transition to a nursing home that he was rehabilitated. Nevertheless, Elli never filed a complaint.

Excerpt 8.

Elli (wife): “In retrospect, I should have demanded that the medication be discontinued and maybe even taken him back home at that point, but I just did not have resources to do that. I was utterly exhausted at that time, I mean, I had spent several years without sleeping and all. (…) and I do judge them, and I think there would have been a reason to make a complaint, but the thing is that when someone is so tired and so weary, it is wrong to expect them to do anything like that.”

Elli’s story shows that defying decisions made by medical experts takes a lot of strength and that people who are already exhausted may not be able to demand justice even if they would want to. Arguments with professionals can also be discouraging, and family members could feel that they were pushed to accept the care as it was. Inkeri, for example, was told to take her husband elsewhere if she was not satisfied with the care, but she did not have any other options. Mirja, who had repeated disagreements over the use of tranquilizers, recalled that she was told to care for her husband herself:

Excerpt 9.

Mirja (wife): “After one dose, I said that maybe they should not continue with the medication because he reacted to it. ‘One cannot react to a single dose like that. If you know better than doctors, care for him yourself’.”

Discussion

In this study, we analyzed family members’ perceptions of the quality of long-term dementia care in Finland using thematic analysis of telephone interviews, drawing on Kröger’s (Citation2022) theory of relative care poverty. Three main themes were identified: (1) access to long-term care, (2) quality of professional care, and (3) handling disagreements about care with healthcare professionals.

From family members’ perspective, the transition to long-term care was often far from safe and timely. Rather, the transition took place as the last resort after all other solutions were proven as insufficient and threats to the care recipient’s well-being had already been actualized. The family members were forced to manage care with little professional support until the need for long-term care was officially accepted and an available place in a nursing home was found. Half of the interviewees disclosed that a place in a nursing home was organized after one or several hospitalizations of the care recipient with dementia. What is important to acknowledge here is that many of the described incidents could have been avoided with sufficient care measures and that hospitalizations per se are problematic for older people’s functional capacity. In fact, over 30% of patients older than 70 years are known to develop an ADL disability during hospital stays (Covinsky et al., Citation2011). Thus, failures in daily care cannot necessarily be compensated with occasional visits to specialists, which is why the care system should react to changes in care needs faster than they do now. Poor access to formal care is also one sign of care poverty (Kröger, Citation2022).

The waiting period can also affect the family members’ own health. The family members consistently described the last months or weeks before the transition as tough and exhausting. In fact, in three cases, a permanent place in a nursing home was acquired only after the family member was no longer able to continue informal care due to their poor condition. Behavioral problems and psychological symptoms of the person with dementia (Chiao et al., Citation2015) as well as binding nature of care (Lindt et al., Citation2020) have been associated with informal caregiver burden. Many of our interviewees reported similar stressors. It is also essential to bear in mind that all older adults with care needs do not have family members monitoring their health and covering for lacking professional care like in this study. Relying heavily on family members’ persistence may increase the risk that older people who live alone and do not have informal support are left outside the care system and face absolute care poverty (see also Kröger, Citation2022).

After attaining a place for the care recipient in a nursing home, the family member’s perceptions on the quality of care were divided, which highlights the differences between individual care units. While nearly half of the interviewees were satisfied with the care, the rest had at least some concerns that can be interpreted as signs of relative personal, practical, and socio-emotional care poverty, to make use of Kröger’s (Citation2022) conceptualization. The family members were most worried about unmet personal care needs, such as continence, hygiene, and getting out of bed. Some family members also disclosed serious malpractices in terms of safety and medication that had led to injuries and decrease in care recipients’ functional capacity. In addition to personal care poverty, family members’ narratives highlighted practical care poverty connected to insufficient support with instrumental activities of daily living such as transportation and managing visits to acute care.

However, although there were signs of socio-emotional care poverty in family members’ narratives, for example lonely and depressed care recipients and lack of meaningful activities in the nursing homes, family members themselves did not necessarily connect them with the quality of care. In fact, some of the family members interpreted the care recipients’ passiveness and withdrawal as acceptable personality traits rather than consequences of dementia or unmet socio-emotional needs. Yet according to literature, people with dementia are often at risk of being cast out of social groups because they tend to be seen as incompetent or unwilling to connect with others (Pirhonen et al., Citation2023). This kind of malignant social positioning (see Sabat, Citation2006) easily results in narrowed perceptions of care and thus lower quality of life.

Family members nevertheless acknowledged the negative effects of the Covid-19 pandemic on the care recipients’ social life. A majority of the family members (15/19) experienced staying in contact with the care recipient as difficult or insufficient due to the changes made to visiting policies (see also Paananen et al., Citation2021; Pirhonen et al., Citation2022). The lack of contact also made it difficult for some of the interviewees to evaluate how well the needs of the care recipients were met.

Finally, our analysis showed that the threshold of questioning the care system was high for family members. Previous studies have already shown that the interactional relationship between family members and nursing home staff can sometimes be problematic (Falzarano et al., Citation2020; Petrovic & Konnert, Citation2017), and that family members can avoid asking questions and making proposals in order to avoid reputation as complainers (Hoek et al., Citation2021). As making a demand for changes is socially more confrontational than merely asking or proposing something, managing disagreements on care needs was highly exhausting for family members. Those who had disagreements with the care professionals felt that their views were ignored and that they did not have power over the decisions on care and medication. Another worrying finding on the disagreements in this study was that the issues persisted despite several confrontations on the same matter. This suggests that the family members’ perspective and experiences may only be respected when they align with the professional perspective, which is against the guidelines of patient- and family-centered care (Tjia et al., Citation2017). A protocol for managing disagreements with family members respectfully is needed to avoid burdensome conflicts.

According to Kröger (Citation2022), targeting care for those with greatest personal care needs and the lowest incomes can alleviate unmet care needs substantially, and the optimal solution for eradicating care poverty would be to develop a universal long-term care system. However, even in the Nordic welfare societies, it is exactly long-term care that the government and wellbeing services counties are planning to further reduce long-term care for older people and the aim is to increase relying on informal care, home care, and communal housing of older people (Anttonen & Karsio, Citation2017; Szebehely & Meagher, Citation2018). As the resources in long-term care of older people are already partly inadequate and lack of care may compromise the well-being of care-recipients, their family members, and healthcare professionals (see Lindt et al., Citation2020; Puthenparambil & Kröger, Citation2016; Van Aerschot et al., Citation2022), decisions to reduce long-term care may lead to increased care poverty. However, it should also be noted that in our study the data collection period coincided with the COVID-19 lockdowns in nursing homes, and this most likely affected the perceived care poverty, since the lockdowns had numerous negative effects (Benzinger et al., Citation2023; Jones et al., Citation2022). Care poverty is also influenced by other contemporary challenges that the health and social care sector face in many countries, such as the rapidly increasing number of older individuals who need long-term care and the lack of educated personnel.

Conclusion

While care recipients’ own assessments of care needs are generally considered more accurate than proxy respondents’, the problem with dementia is that it decreases cognitive functioning and can make self-reports less valid or even unusable. In this study, the interviews were conducted via telephone and as we were interested in the family members’ perspective, we deemed the use of proxy respondents justifiable. However, it is important to acknowledge that self-reports and proxy reports follow different values and standards, and family members’ views should therefore not be understood as direct substitutes of care recipients’ reports. For example, in previous studies, informal carers of older people have reported higher unmet needs for services compared to care recipients (Brimblecombe et al., Citation2017), and they have also been found to project part of their own quality of life into the assessments of care recipients’ quality of life (Arons et al., Citation2013). Another limitation of this study is that the interviews did not reach family members from linguistic or ethnic minorities, whose perspectives on the access and quality of care should receive more attention due to the effects of language and attitudinal barriers (see also Kröger, Citation2022).

Another issue to consider regarding the results is the COVID-19 pandemic. Although the interviews were conducted a year after the lockdown of nursing homes, and we concentrated on analyzing family members’ COVID-19-free experiences, the pandemic might have affected the interviewees’ general opinions on care or everyday life. For example, in seven cases the loved one living in a nursing home had died during the year between the lockdown and the interviewing period. None of the family members expressed worry that the death would have been caused by the COVID-19 virus, yet some anticipated that the lack of activities during the lockdown had worsened the care recipient’s condition and resulted in premature death. Thus, the COVID situation might have made some of the family members more critical toward the care received in general. This does not, however, invalidate the issues they reported.

Care poverty is a new theoretical concept launched by Kröger in 2019. The concept has the potential to become a general, internationally recognized concept since it captures the phenomenon of inadequate or misplaced care regardless of structures of the care system. One strength of this research is that we show what Kröger’s theoretical concept looks like in the real nursing home world of real older adults. We show how even people residing in round-the-clock care facilities may lack the care they would specifically need, and, thus, also participate in care-ethical discussions. In addition, stretching the standards of care for older people also indicates social inequality based on age.

The findings in this study can also contribute to the development of better services in future. It seems crucial to enhance communication between family members and the nursing staff. Better communication would benefit both sides and especially the care recipients. Listening to family members’ life-long experiences and knowledge on their close ones’ situation would help the staff to make decisions in the care recipients’ favor, just as the previous research suggests (Verbeek, Citation2017; Powell et al., Citation2018). And when the information from the staff is scarce, the family members become less trusting and more skeptical regarding the care (see also Givens et al., Citation2012). To avoid discouragement and distrust and to improve communication and overcome disregard, a protocol for managing disagreements with family members should be instituted in every nursing home. Our findings add to a solid foundation to develop a protocol for settling disputes between family members and the staff in nursing homes in future.

Ethical Approval Statement

Ethical approval for the research was applied from the Research Ethics Committee in the Humanities and Social and Behavioral Sciences.

Acknowledgements

We wish to thank all the interviewees who participated in this research and shared their valuable insights on matters that were not always easy to discuss. Gerontology Research Center is a joint effort between Tampere University and the University of Jyväskylä. The research was carried out in the framework of the Center of Excellence in Research on Ageing and Care (CoEAgeCare).

Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data Availability Statement

Data not available/The data that has been used is confidential. Due to the sensitive nature of the questions asked in this study, informants were assured raw data will remain confidential and will not be shared. The article does not use previously published materials.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 The thematic map is figurative; it depicts the main themes and the most significant sub-themes (see Braun & Clarke, Citation2006, p. 91). The figure was drawn with Microsoft Powerpoint.

References

- Act on Supporting the Functional Capacity of the Older Population and on Social and Health Care Services for Older Persons. (980/2012). Ministry of Social Affairs and Health, Finland. https://www.finlex.fi/fi/laki/ajantasa/2012/20120980#L3P18

- Act on changing the Act on Supporting the Functional Capacity of the Older Population and on Social and Health Care Services for Older Persons. (604/2022). Ministry of Social Affairs and Health, Finland.

- Alzheimer Europe. (2019). Dementia in Europe Yearbook 2019. Estimating the prevalence of dementia in Europe. Available at: https://www.alzheimer-europe.org/sites/default/files/alzheimer_europe_dementia_in_europe_yearbook_2019.pdf

- Anttonen, A., & Karsio, O. (2017). Marketization from within: Changing governance of care services. In F. Martinelli, A. Anttonen & M. Mätzke (Eds.), Social services disrupted changes, challenges and policy implications for Europe in times of austerity. New Horizons in Social Policy. Elgar Online.

- Arons, A. M., Krabbe, P. F., Schölzel-Dorenbos, C. J., van der Wilt, G. J., & Olde Rikkert, M. G. M. (2013). Quality of life in dementia: A study on proxy bias. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 13, 110. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2288-13-110

- Benzinger, P., Wahl, H. W., Bauer, J. M., Keilhauer, A., Dutzi, I., Maier, S., Hölzer, N., Achterberg, W. P., & Denninger, N.-E. (2023). Consequences of contact restrictions for long-term care residents during the first months of COVID-19 pandemic: A scoping review. European Journal of Ageing, 20(1), 39. article number 39. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10433-023-00787-6

- Boström, M., Ernsth Bravell, M., Björklund, A., & Sandberg, J. (2017). How older people perceive and experience sense of security when moving into and living in a nursing home: A case study. European Journal of Social Work, 20(5), 697–710. https://doi.org/10.1080/13691457.2016.1255877

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–−101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2019). Reflecting on reflexive thematic analysis. Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health, 11(4), 589–597. https://doi.org/10.1080/2159676X.2019.1628806

- Brimblecombe, N., Pickard, L., King, D., & Knapp, M. (2017). Perceptions of unmet needs for community social care services in England: A comparison of working carers and the people they care for. Health & Social Care in the Community, 25(2), 435–446. https://doi.org/10.1111/hsc.12323

- Castle, N. G. (2006). Family members as proxies for satisfaction with nursing home care. Joint Commission Journal on Quality and Patient Safety, 32(8), 452–458. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1553-7250(06)32059-4

- Chiao, C. Y., Wu, H. S., & Hsiao, C. Y. (2015). Caregiver burden for informal caregivers of patients with dementia: A systematic review. International Nursing Review, 62(3), 340–−350. https://doi.org/10.1111/inr.12194

- Covinsky, K. E., Pierluissi, E., & Johnston, B. (2011). Hospitalization-associated disability “She was probably able to ambulate, but I’m not sure”. JAMA, 306(16), 1782–−1793. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2011.1556

- Duggleby, W., Schroeder, D., & Nekolaichuk, C. (2013). Hope and connection: The experience of family caregivers of persons with dementia living in a long-term care facility. BMC Geriatrics, 13(1), 112. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2318-13-112

- Duggleby, W., Williams, A., Wright, K., & Bollinger, S. (2009). Renewing everyday hope: The hope experience of family caregivers of persons with dementia. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 30(8), 514–521. https://doi.org/10.1080/01612840802641727

- Ekström, K., Spelmans, S., Ahlström, G., Nilsen, P., Alftberg, Å., Wallerstedt, B., & Behm, L. (2019). Next of kin’s perceptions of the meaning of participation in the care of older persons in nursing homes: A phenomenographic study. Scandinavian Journal of Caring Sciences, 33(2), 400–408. https://doi.org/10.1111/scs.12636

- Falzarano, F., Reid, M. C., Schultz, L., Meador, L. H., & Pillemer, K. (2020). Getting along in assisted living: Quality of relationships between family members and staff. The Gerontologist, 60(8), 1445–1455. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gnaa057

- Finnish Institute for Health and Welfare. (2023). Sosiaali- ja terveysalan tilastollinen vuosikirja 2023 (julkari.fi) [Statistical yearbook on social welfare and health care 2023]. Finnish Institute for Health and Welfare (THL).

- Finnish Ministry of Social Affairs and Health. (2020). Quality recommendation to guarantee a good quality of life and improved services for older persons 2020–2023: The Aim is an Age-friendly Finland. Helsinki: Finnish Ministry of Social Affairs and Health. http://urn.fi/URN:ISBN:978-952-00-8427-1

- Finnish National Board on Research Integrity. (2023). Hyvä tieteellinen käytäntö ja sen loukkausepäilyjen käsitteleminen Suomessa. Guidelines of the Finnish National Board on Research Integrity. Helsinki. Available at: https://tenk.fi/fi/hyva-tieteellinen-kaytanto-htk

- Givens, J. L., Lopez, R. P., Mazor, K. M., & Mitchell, S. L. (2012). Sources of stress for family members of nursing home residents with advanced dementia. Alzheimer Disease and Associated Disorders, 26(3), 254–259. https://doi.org/10.1097/wad.0b013e31823899e4

- Graneheim, U., Johansson, A., & Lindgren, B.-M. (2014). Family caregivers’ experiences of relinquishing the care of a person with dementia to a nursing home: Insights from a meta-ethnographic study. Scandinavian Journal of Caring Sciences, 28(2), 215–224. https://doi.org/10.1111/scs.12046

- Groenvynck, L., de Boer, B., Hamers, J. P. H., van Achterberg, T., van Rossum, E., & Verbeek, H. (2021). Toward a Partnership in the Transition from Home to a Nursing Home: The TRANSCIT Model. Journal of the American Medical Directors Association, 22(2), 351–356. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamda.2020.09.041

- Hoek, L. J., van Haastregt, J. C., de Vries, E., Backhaus, R., Hamers, J. P., & Verbeek, H. (2021). Partnerships in nursing homes: How do family caregivers of residents with dementia perceive collaboration with staff? Dementia (London, England), 20(5), 1631–1648. https://doi.org/10.1177/1471301220962235

- Holmgren, J., Emami, A., Eriksson, L. E., & Eriksson, H. (2013). Being perceived as a ‘visitor’ in the nursing staff’s working arena – the involvement of relatives in daily caring activities in nursing homes in an urban community in Sweden. Scandinavian Journal of Caring Sciences, 27(3), 677–685. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-6712.2012.01077.x

- Huang, H. L., Shyu, Y. I. L., Chen, M. C., Huang, C. C., Kuo, H. C., Chen, S. T., & Hsu, W. C. (2015). Family caregivers’ role implementation at different stages of dementia. Clinical Interventions in Aging, 10, 135–146. https://doi.org/10.2147/CIA.S60574

- Jakobsen, R., Sellevold, G. S., Egede-Nissen, V., & Sørlie, V. (2019). Ethics and quality care in nursing homes: Relatives’ experiences. Nursing Ethics, 26(3), 767–−777. https://doi.org/10.1177/0969733017727151

- Jones, K., Schnitzler, K., & Borgstrom, E. (2022). The implications of COVID-19 on health and social care personnel in long-term care facilities for older people: An international scoping review. Health & Social Care in the Community, 30(6), e3493–e3506. https://doi.org/10.1111/hsc.13969

- Kröger, T. (2022). Care poverty. When older people’s needs remain unmet. Springer Nature e-book. Palgrave MacMillan. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-97243-1

- Lethin, C., Leino-Kilpi, H., Roe, B., Soto, M. M., Saks, K., Stephan, A., Zwakhalen, S., Zabalegui, A., & Karlsson, S. (2016). Formal support for informal caregivers to older persons with dementia through the course of the disease: An exploratory, cross-sectional study. BMC Geriatrics, 16(1), 32. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-016-0210-9

- Lima, J. C., & Allen, S. M. (2001). Targeting risk for unmet need: Not enough help versus no help at all. The Journals of Gerontology, Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 56(5), S302–S310. https://doi.org/10.1093/geronb/56.5.s302

- Lindeza, P., Rodrigues, M., Costa, J., Guerreiro, M., & Rosa, M. M. (2020). Impact of dementia on informal care: A systematic review of family caregivers’ perceptions. BMJ Supportive & Palliative Care, 20, 304. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjspcare-2020-002242

- Lindt, N., van Berkel, J., & Mulder, B. C. (2020). Determinants of overburdening among informal carers: A systematic review. BMC Geriatrics, 20(1), 304. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12877-020-01708-3

- Ministry of Social Affairs and Health. (2019). Development of informal care and family care in 2015–2018. Conclusions and recommendations for further measures. http://urn.fi/URN:ISBN:978-952-00-4022-2

- National Institute for Health and Welfare. (2024). Memory disorders - THL. Finnish Institute for Health and Welfare (THL).

- OECD/European Union. (2018). Dementia prevalence. In Health at a glance: Europe 2018: State of health in the EU cycle. OECD Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1787/health_glance_eur-2018-19-en

- O’Neill, M., Ryan, A., Tracey, A., & Laird, L. (2020). “You’re at their mercy”: Older peoples’ experiences of moving from home to a care home: A grounded theory study. International Journal of Older People Nursing, 15(2), e12305. https://doi.org/10.1111/opn.12305

- Paananen, J., Rannikko, J., Harju, M., & Pirhonen, J. (2021). The impact of Covid-19-related distancing on the well-being of nursing home residents and their family members: A qualitative study. International Journal of Nursing Studies Advances, 3, 100031. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnsa.2021.100031

- Petrovic, A., & Konnert, C. A. (2017). How do family members deal with conflict in long-term care? Application of conflict theory. Innovation in Aging, 1(suppl_1), 853–853. https://doi.org/10.1093/geroni/igx004.3071

- Pirhonen, J., Forma, L., & Pietilä, I. (2022). COVID-19 related visiting ban in nursing homes as a source of concern for residents’ family members: A cross sectional study. BMC Nursing, 21(1), 255. Open Access: https://rdcu.be/cVBU5 https://doi.org/10.1186/s12912-022-01036-4

- Pirhonen, J., Vähäkangas, A., & Saarelainen, S. (2023). Religious bodies: Lutheran chaplains interpreting and asserting religiousness of people with severe dementia in Finnish nursing homes. Journal of Ageing and Longevity, 3(1), 92–106. https://www.mdpi.com/2673-9259/3/1/8 https://doi.org/10.3390/jal3010008

- Powell, C., Blighe, A., Froggatt, K., McCormack, B., Woodward-Carlton, B., Young, J., Robinson, L., & Downs, M. (2018). Family involvement in timely detection of changes in health of nursing homes residents: A qualitative exploratory study. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 27(1-2), 317–327. https://doi.org/10.1111/jocn.13906

- Puthenparambil, J. M., & Kröger, T. (2016). Using private social care services in Finland: Free or forced choices for older people? Journal of Social Service Research, 42(2), 167–−179. https://doi.org/10.1080/01488376.2015.1137534

- Roberts, A. R., & Ishler, K. J. (2018). Family involvement in the nursing home and perceived resident quality of life. The Gerontologist, 58(6), 1033–1043. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gnx108

- Sabat, S. R. (2006). Mind, meaning, and personhood in dementia: The effects of positioning. In Julian C. Hughes, Stephen J. Louw & Steven R. Sabat (eds.), Dementia: Mind, meaning and the person., 287–302. Oxford University Press.

- Sury, L., Burns, K., & Brodaty, H. (2013). Moving in: Adjustment of people living with dementia going into a nursing home and their families. International Psychogeriatrics, 25(6), 867–−876. https://doi.org/10.1017/s1041610213000057

- Szebehely, M., & Meagher, G. (2018). Nordic eldercare – Weak universalism becoming weaker? Journal of European Social Policy, 28(3), 294–−308. https://doi.org/10.1177/0958928717735062

- Teahan, Á., Lafferty, A., Cullinan, J., Fealy, G., & O’Shea, E. (2021). An analysis of carer burden among family carers of people with and without dementia in Ireland. International Psychogeriatrics, 33(4), 347–−358. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1041610220000769

- Tjia, J., Lemay, C. A., Bonner, A., Compher, C., Paice, K., Field, T., Mazor, K., Hunnicutt, J. N., Lapane, K. L., & Gurwitz, J. (2017). Informed family member involvement to improve the quality of dementia care in nursing homes. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 65(1), 59–−65. https://doi.org/10.1111/jgs.14299

- Van Aerschot, L., Puthenparambil, J. M., Olakivi, A., & Kröger, T. (2022). Psychophysical burden and lack of support: Reasons for care workers’ intentions to leave their work in the Nordic countries. International Journal of Social Welfare, 31(3), 333–−346. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijsw.12520

- Verbeek, H. (2017). Inclusion and Support of Family Members in Nursing Homes. In: Schüssler, S., Lohrmann, C. (eds.) Dementia in Nursing Homes., 67–−76. Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-49832-4_6

- Voutilainen, P., Backman, K., Isola, A., & Laukkala, H. (2006). Family members’ perceptions of the quality of long-term care. Clinical Nursing Research, 15(2), 135–−149. https://doi.org/10.1177/1054773805285697

Appendix 1.

Interview Themes and Questions

Theme 1: Background

Examples of questions:

What is your relation to the person with dementia living in a nursing home?

How long has your family member had dementia?

How long has your family member been living in a nursing home?

How often do you visit the nursing home?

Theme 2: The Transition to the Nursing Home

Examples of questions:

What do you remember about the time of the transition?

How did you feel about the transition? How did the person with dementia take it?

How do you think transition affected the person’s social relationships and networks?

At the time of the transition, what type of background information was gathered about your family member?

Theme 3: Living in the Nursing Home

Examples of questions:

How does your family member get along in the nursing home?

What kind of hobbies or recreation activities do they have in the nursing home?

How and how often do the nursing home staff keep in contact with you?

How often do you contact the nursing home?

Do you feel adequately informed by the nursing home regarding relevant information?

How do you see your role in your family member’s life now?

How would you evaluate the quality of care provided by the nursing home?

Theme 4: Social Identity

Examples of questions:

How has dementia changed your family member?

How has your family member’s dementia affected you?

How would you describe the nursing home personnel’s attitudes toward your family member?

Could you describe the changes you have observed in your family member’s condition?

Have you discussed the current situation with your other family members?

Theme 5: Covid-19

What do you remember about the time of Covid-19 isolation?

Theme 6: Death (for Interviewees Whose Family Member is No Longer Alive)

Examples of questions:

What do you remember about the death of your family member?

Did your family member have a palliative care decision?

Did the nursing home staff members prepare you for your family member’s death? How?

Were you present at the time of death? How did you experience it?

Did you receive some kind of support after the loss? What kind of support, from where?

How were practical matters concerning your family member’s residence handled after the death?

If the family member with dementia was no longer alive, the questions in previous themes were formatted in past tense (How long has your family member had dementia → How long did your family member have dementia?).