Abstract

This study employs descriptive and regression analyses of the National Sports and Society Survey (N = 3,993) to examine the patterns and implications of sexual stigma and prejudice in sports contexts by focusing on U.S. adults’ reports of sports-related mistreatment and involvement. Results indicate that about 1/3 of adults perceive sports as unwelcoming to LGBT athletes and nearly 40% report experiencing sports-related mistreatment; adults who identify as a sexual minority are particularly likely to perceive sports as unwelcoming and to report personal mistreatment. They are also less likely than self-identified heterosexuals to play, spectate, and talk about sports; sports-related mistreatment and childhood sports histories do not explain these patterns. Overall, the findings suggest that more action is needed to offset the presence and influence of sexual stigma and prejudice and to provide more welcoming sports environments for all.

Introduction

Sport is a popular form of leisure throughout the life course (Denison & Kitchen, Citation2015; Dionigi, Citation2006; Myrdahl, Citation2011). Although sports involvement may enhance health, well-being, and social belonging, it can also lead to exclusionary, restrictive, and oppressive experiences. Critical sport and leisure studies seek to identify the contexts and means through which sport and leisure may reproduce or transform social inequalities; understanding the inclusivity of sports cultures, especially for people who identify as lesbian, gay, or bisexual (LGB), has been a particular concern (Allison & Knoester, Citation2020; Barbosa et al., Citation2020; Carter & Baliko, Citation2017; Elling-Machartski, Citation2017; Mock et al., Citation2019; Symons et al., Citation2017).

On the one hand, there is evidence that sexual stigma (i.e., stigma attached to anything that is not heterosexual) and prejudice (i.e., internalization of societal stigma that leads to negative assessments of individuals who identify as, or are thought to be, a sexual minority) have declined in sport, as in society (Anderson, Citation2014; Herek, Citation2009; Myrdahl, Citation2011). For example, men have increasingly adopted “inclusive” masculinities that embrace actions that were previously stigmatized as “feminine” and “gay” such as emotional expressiveness and physical closeness. Generally, inclusive masculinities encourage respect for diverse sexual identities (Anderson, Citation2011, Citation2014; Symons et al., Citation2017). Decreases in sexual stigma and prejudice have also resulted in greater acceptance of lesbian and bisexual women in sports and have lessened the “lesbian” connotation associated with women’s sports (Cahn, Citation2015; Griffin, Citation1998; Lenskyj, Citation2003). Although sports contexts are still commonly viewed as heterosexist, changes that include increasing numbers of athletes coming “out,” high-profile campaigns against prejudice and discrimination in sport, and sport organizations’ support for laws and policies that address inequalities (e.g., marriage equality) are reshaping them (Anderson et al., Citation2016; Cavalier & Newhall, Citation2018: Krane, Citation2019). Also, notably, sports have traditionally offered unique opportunities for community for individuals who identify as a sexual minority (Barbosa et al., Citation2020; Carter & Baliko, Citation2017; Mock et al., Citation2019; Myrdahl, Citation2011).

On the other hand, however, sport may lag behind other social institutions in its inclusivity of diverse sexualities. As a rather isolated, gender segregated, quasi-total institution that is partially insulated from broader social forces, sport may be more immune to the effects of broader social movements (Anderson, Citation2005; Kian et al., Citation2015). Sport was founded on the reproduction of heterosexual masculinities defined through the marginalization of women and sexual minorities, evidenced in women’s “apologetic” stance toward challenging traditional gender expectations in sports and expectations of silence about sexual identities (Allison, Citation2018; Birrell & Richter, Citation1987; Theberge, Citation2000). Although the number of publicly “out” athletes has grown, their scarcity at higher levels of competition and near absence in men’s college and professional team sports is revealing (Cavalier, Citation2019; Griffin, Citation2012). Research on athletes and industry workers indicates a decline in sexual stigma and prejudice, but a persistence of heterosexism (Cavalier, Citation2016; Herrick & Duncan, Citation2018; Mann & Krane, Citation2019). Thus, sport does not seem to be a utopia for individuals who identify as, or are thought to be, a sexual minority (Denison & Kitchen, Citation2015; Myrdahl, Citation2011; Symons et al., Citation2017).

Nevertheless, quantitative research on sports involvement experiences across different sexual identities is lacking (Denison & Kitchen, 2015; Gill et al., Citation2010). Qualitative research that relies on small numbers of participants within single sporting contexts, often with homogeneous sexual and gender identities, is useful (Baiocco et al., 2018; Carter & Baliko, Citation2017; Cronan & Scott, Citation2008; Myrdahl, Citation2011). Yet, quantitative work is needed to identify broader patterns of attitudes and experiences (Denison & Kitchen, Citation2015; Elling & Janssens, Citation2009). Thus, this study uses quantitative data to investigate: How common are sexual stigma and prejudice in U.S. sports contexts? Do these result in lower levels of sports involvement for individuals who identify as a sexual minority, compared to self-identified heterosexuals?

Specifically, this study examines the relationships between U.S. adults’ sexuality, sports-related mistreatment, and sports involvement. The focus is on the extent to which individuals who identify as a sexual minority, compared to self-identified heterosexuals, are especially likely to perceive sexual stigma, experience mistreatment, and disengage from sports participation, spectatorship, and conversations as adults. Potential generational changes in the recognition of sports-related mistreatment are also considered; also, the research assesses links between reports of perceived sexual stigma, sports-related mistreatment, childhood sports histories, and adult sports involvement. Finally, this study investigates whether identifying as lesbian, gay, bisexual or as another sexuality, compared to identifying as heterosexual, has different implications for sports-related experiences depending on one’s gender.

The research builds upon and extends understandings of the relationships between sexuality and sports and leisure experiences from qualitative work (e.g., Anderson, Citation2014; Dolance, Citation2005; Myrdahl, Citation2011) and large-scale descriptive information from U.S. youth (e.g., Kosciw et al., Citation2012; Citation2018) and adults (e.g., Denison & Kitchen, Citation2015). It specifically complements Denison and Kitchen (Citation2015) landmark cross-national study by using different measures of sports-related mistreatment and involvement and uniquely employing multiple regression analyses that isolate associations between sexuality, sports-related mistreatment, and sports involvement after taking into account background characteristics, gender identities, and childhood sports histories. Consequently, this research more comprehensively considers the interconnections between diverse sexualities, sports-related mistreatment (i.e., perceptions of LGB, as well as transgender (T), athlete unwelcomeness and reports of personal mistreatment), sports involvement (i.e., participation, spectatorship, and sports-related conversation), gender identities (e.g., including nonbinary identities), childhood sports histories (e.g., athlete identities and organized sports participation), and other social contexts (e.g., age, SES, race/ethnicity, and family contexts) in the analysis. Furthermore, this research studies more U.S. adults, who were not recruited with invitations to study homophobia and are not disproportionately under the age of 40; thus, it may offer more representative information about sports-related mistreatment and involvement in the U.S. population as well as allow for more legitimate subsample considerations in the analytic models that include, but also go beyond, sexuality (e.g., age, gender identities, SES, race/ethnicity, etc.).

Conceptual framework

The conceptual framework for this study draws upon Herek’s (Citation2009) theorizing of sexual stigma and prejudice in the US. It also integrates insights from studies of the relationships between sexuality and sports and leisure experiences in society (e.g., Denison & Kitchen, Citation2015; Kivel & Kleiber, Citation2000; Myrdahl, Citation2011). The framework recognizes that sexual stigma, prejudice, and mistreatment are commonly embedded (and continually challenged) in sport and leisure structures, cultures, and interactions (Griffin, Citation1998; Herek, Citation2009; Pavlidis & Fullagar, Citation2013; Symons et al., Citation2017) – with individualized effects (e.g., sense of self, values, and aspirations). It highlights that heterosexism has had adverse effects on the experiences of individuals who identify as, or are thought to be, a sexual minority. Largely, this occurs through heteronormativity, or the assumption of heterosexuality, and, when variance in sexualities becomes apparent, the activation of prejudices about people who identify as a sexual minority such that they are viewed as inferior and often mistreated (Griffin, Citation1998; Herek, Citation2009; Symons et al., Citation2017). Nonetheless, sports and leisure experiences can also be important sources of positive interactions, including their functioning as places for community for people who identify as a sexual minority (Carter & Baliko, Citation2017; Denison & Kitchen, Citation2015; Myrdahl, Citation2011; Theberge, Citation2000).

The framework highlights what Herek (Citation2009) describes as felt stigma and enacted stigma. Felt stigma involves becoming aware of the existence of sexual stigma and assessing the likelihood of it being enacted in different situations. An example is one’s perception of how welcome individuals who identify as a sexual minority may be in sports contexts. Felt stigma can shape behaviors – such as sports involvement patterns. Enacted stigma includes overt expressions of sexual stigma; thus, it entails mistreatment in sports contexts because of sexual prejudice. The framework for this study anticipates that sexual stigma, prejudice, and mistreatment that includes both felt and enacted stigma, result in lower levels of sports participation among adults who identify as a sexual minority (Baiocco et al., Citation2018; Denison & Kitchen, Citation2015; Symons et al., Citation2017). Previous research and theorizing has recognized the presence and negative implications of felt stigma and enacted stigma in sports; yet, virtually no research has examined these processes among large U.S. adult populations (Denison & Kitchen, Citation2015; Kosciw et al., Citation2012; Myrdahl, Citation2011; Symons et al., Citation2017).

Sexuality, gender, and sports contexts

Indeed, extant research suggests that sexual stigma and prejudice in sport persist, although relationships between sexuality and sports experiences have evolved and still seem to depend on gender. Researchers largely began to study the associations between sexuality and sport in the late 1970s (Cavalier, Citation2019; Lenskyj, Citation2003). Early studies documented widespread and overt homophobia, defined as prejudice, discrimination, and harassment – including acts of violence – that are based on fear, distrust, dislike, or hatred of individuals who identify as, or are thought to be, a sexual minority (Griffin, Citation1998; Hekma, Citation1998). Thus, sexual identities were often concealed – making it difficult to appropriately describe the experiences and social contexts relating to sexuality and sports (Anderson, Citation2005; Griffin, Citation1998).

Anderson (Citation2011, Citation2014) characterizes this era as possessing high levels of “homohysteria,” which involves a fear of being homosexualized by association with people who identify as a sexual minority. This is a product of: (a) an awareness of homosexuality as a sexual orientation, (b) high levels of homophobia within the culture, and (c) the conflation of perceived feminine behaviors in men with the assumption that these behaviors are indicative of same-sex desires. Indeed, hegemonic masculinity maintains its dominance through the repudiation of subordinated masculinities and the feminine during times of high homohysteria. As sexual stigma and prejudice have declined, however, multiple forms of masculinity have become more culturally valued; consequently, masculinities that embrace expressions previously defined as feminine have now become normative. Further, it is now more acceptable to “come out” as gay (Anderson, Citation2011; Citation2014; Myrdahl, Citation2011).

Sexual stigma and prejudice have operated somewhat differently in women’s sports (Griffin, Citation1998, Citation2012; Hekma, Citation1998). Historically, women were “masculinized” by their participation in sports and presumed to be lesbian due to the assumed associations between perceptions of women’s masculinity and their homosexuality; yet, the assumed lesbianism of women’s sports has eroded. The emergence of more queer and inclusive communities surrounding especially women’s sports have challenged sexual stigma and prejudice – as well as traditional notions of gender (Cahn, Citation2015; Elling-Machartski, Citation2017; Lenskyj, Citation2003; Mann & Krane, Citation2019; Myrdahl, Citation2011; Pavlidis & Fullagar, Citation2013). Yet, the consequences of declining sexual stigma and prejudice for women’s sports contexts, compared to men’s, have been less frequently studied (Anderson et al., Citation2016; Mann & Krane, Citation2018).

Griffin’s (Citation1998) typology of hostile, tolerant, and inclusive environments describes an evolving relationship between sexuality and sport. By 2000, the era of hostility had seemingly ended; LGB individuals were accepted in sports, although their presence was tempered by expectations of silence and invisibility (Anderson, Citation2011; Griffin, Citation2012). Yet, the transition from tolerance to inclusion remains incomplete. Inclusivity is characterized by public recognition of minority identities, positive attitudes, policy supports, and welcoming team cultures. However, sexual stigma and prejudice continue to affect how athletes, coaches, administrators, and others view and experience sports cultures (Denison & Kitchen, Citation2015; Petty & Trussell, Citation2018).

Enacted stigma seems commonplace. For example, thousands of lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer (LGBTQ) youth ages 13–21 have reported on their school-related experiences across the US over the past 20 years. In 2011, 27.8% of the surveyed LGBTQ athletes reported ever having been harassed or assaulted because of their sexual orientation in school sports contexts. Also, over 50% of the LGBTQ youth who took physical education (PE) classes reported being bullied or harassed during class because of their sexual orientation (Kosciw et al., Citation2012). Further, 11% of more recently surveyed LGBTQ youth reported enacted stigma through being prevented or discouraged from school sports because of their sexual or gender identity (Kosciw et al., Citation2018).

Denison and Kitchen (Citation2015) found that 80% of their volunteer participants (N = 9,494) reported witnessing or experiencing enacted sexual stigma such as verbal slurs, bullying, verbal threats, or physical assault. The cross-national study reports the sports experiences of many self-identified gay (49% of sample), lesbian (15%), bisexual (7%), straight (26%), and other sexuality (2%) individuals, although it focuses on LGB experiences among younger adults (e.g., 70% of sample is <40 years old). Gay and bisexual men were about twice as likely as lesbians and bisexual women to have reported being bullied, threatened, or assaulted, which suggests that the enacted stigma associated with identifying as a sexual minority may depend on gendered identities and sports contexts, with women’s sports cultures potentially being safer than men’s sports cultures (Dolance, Citation2005; Myrdahl, Citation2011; Theberge, Citation2000).

Felt stigma also appears to be pervasive. Among the Out on the Fields respondents, only 1% felt that people who identify as LGB were completely accepted in sporting culture (Denison & Kitchen, Citation2015). In addition, 25% of the LGBTQ youth from the 2017 school climate study reported avoiding athletic fields and facilities at school because they felt unsafe or uncomfortable; relatedly, about 40% of respondents avoided both PE classes and locker rooms, for these reasons (Kosciw et al., Citation2018). Herrick and Duncan (Citation2018) focus groups (N = 42 LGBTQ + participants) revealed persistent fears of discrimination and violence that were linked to gender or sexuality, as well, in physical activities. Further, Cavalier’s (Citation2016) interviews with LGB employees in both men’s and women’s sports found that those working in men’s sports especially perceived these institutions as heterosexist and were thus more persuaded to remain closeted. Relatedly, Denison and Kitchen (Citation2015) found some evidence that felt stigma is linked to the intersections between sexuality and gender, in that most self-identified gay and bisexual men remained at least partially in the closet while participating in team sports due to felt stigma; comparable women were less likely to report remaining closeted.

More generally, sports contexts have been described as “transitioning” because sexual stigma and prejudice have seemingly declined, although they remain present (Mann & Krane, Citation2018; Petty & Trussell, Citation2018). Piedra et al. (Citation2017), in their study (N = 879 adults) of adults in the UK and Spain who were actively participating in or following a sport(s), developed and employed a scale that tapped perceptions of both “non-rejection” (i.e., more abstract perceptions of the visibility and equality afforded to LGBT individuals – such as being willing to join a sports club with LGBT members) and “acceptance” (i.e., more personal feelings about being in close contact with LGBT individuals – such as being equally glad with having a heterosexual or homosexual coach for your child) of sexual diversity in sports. They found that non-rejection attitudes were relatively high, indicating substantial tolerance of sexual diversity in sports; however, acceptance scores were characterized as mid-level. Furthermore, responses clustered around low tolerance, partial inclusion, and high tolerance views – each of which represented about 1/3 of the distribution. Similarly, Gill et al. (Citation2010) surveyed undergraduate students (N = 200) about the sports cultures in PE, exercise, and organized sports settings. Overall, the students rated the sports inclusiveness for LGBT students at their former high school as “neither inclusive or exclusive” (where 1 = very inclusive; 5 = very exclusive) for each of these dimensions of sports cultures, on average.

Altogether, these empirical findings reflect felt stigma, wherein respondents recognize the existence of sexual stigma and use their knowledge of this stigma and its context to gauge the probability that the stigma becomes enacted in different situations. Nonetheless, previous research has focused on LG individuals and their experiences; virtually no research has comprehensively considered the experiences of individuals with bisexual or other non-heterosexual identities – especially with quantitative research approaches. Also, research on the intersectional implications of sexuality and gender is limited; work has largely isolated the experiences of gay men and lesbian women and occasionally contrasted their experiences with their heterosexual counterparts or examined small samples of individuals with diverse sexual identities (Anderson, Citation2014; Denison & Kitchen, Citation2015; Herrick & Duncan, Citation2018). Thus, these considerations warrant further study.

Sexuality, gender, and sports participation

In conditions of hostility or even tolerance, compared to inclusivity, individuals who identify as a sexual minority may be motivated to avoid sports or seek out segregated leagues in which to participate (Elling & Janssens, Citation2009; Mock et al., Citation2019; Symons et al., Citation2017). Thus, felt and enacted sexual stigma can reduce sports participation among individuals who identify as a sexual minority. Indeed, individuals who identify as a sexual minority seem to participate in sports at markedly lower rates than heterosexuals; also, women appear to participate in sports at lower rates than men (Calzo et al., Citation2014; Kosciw et al., Citation2012; Toomey & Russell, Citation2013; Zipp, Citation2011). However, there is a lack of clarity about the extent to which such gaps reflect self-selection into participation, disengagement from sports, or the influence of other factors. Further, research has not comprehensively studied patterns of disengagement from sports across diverse gender and sexual identities (Calzo et al., Citation2014; Denison & Kitchen, Citation2015; Elling-Machartski, Citation2017).

Hekma (Citation1998) suggests that the dominance of heterosexual masculinity in sports pushes gay and bisexual men to avoid sports, relative to heterosexual men. Meanwhile, more progressive women’s sports cultures often encourage lesbian and bisexual women to seek out and engage in sports participation (Birrell & Richter, Citation1987; Theberge, Citation2000). Indeed, Elling and Janssens’ (Citation2009) study of Dutch adults (N = 1,225) found gender differences in reported sports participation across sexual identities along these lines. Individuals who identify as a sexual minority may avoid or leave sports as a result of negative experiences, including encounters with bias, prejudice, and discrimination (Petty & Trussell, Citation2018; Zipp, Citation2011). In fact, Baiocco et al. (Citation2018) survey of Italian men (N = 88 gay men; 120 heterosexual men) found evidence of an association between reported dropout from sports and a fear of being bullied, as well as experiences of bullying due to sexual identity, among gay men. Further, Symons et al. (Citation2017) Australian study of 294 LGB adults found that 40% of the respondents reported sports-related mistreatment based on sexuality; men were twice as likely as women to report such mistreatment. The mistreatment was linked to harmful emotional impacts, negative sports experiences, and often sports avoidance – especially for men. Relatedly, Denison and Kitchen (Citation2015) discovered that gay men were less likely than lesbians to play sports as adults and were substantially more likely to point to previous mistreatment and felt stigma as reasons for withdrawing from sports. Yet, comparatively little research has considered disengagement from sports across diverse gender and sexual identities among U.S. adults.

Sexuality, gender, and other forms of sports involvement

There is even more limited research on how diverse sexual and gender identities may be associated with other forms of sports involvement, including sports spectatorship and talking about sports with others. Overwhelmingly, inquiries have focused on comparing men’s and women’s sports fandom. This work suggests that although women’s involvement as sports fans has grown, women remain underrepresented as fans, compared to men. For instance, a Gallup poll of U.S. adults found that 66% of men, but 51% of women identified as sports fans (Jones, Citation2015). Additionally, women report somewhat lower levels of fan involvement than men, watching fewer hours of sports on TV and talking less about sports with others (Bahk, Citation2000). Fan cultures in men’s spectator sports often marginalize women through defining and policing definitions of “authentic” fandom that represent cultural constructions of heterosexual masculinity (Allison & Knoester, Citation2020; Denison & Kitchen, Citation2015).

In fact, the Out on the Fields respondents indicated that enacted stigma is most likely to occur in spectator stands, as opposed to other locations in sports contexts. Nearly 80% reported felt stigma such that they thought an openly LGB individual would not be very safe as a sports spectator. Yet, Allison’s (Citation2018) ethnographic study of U.S. women’s professional soccer found that lesbian fans were a large and visible presence at games, albeit one that was downplayed by team management given fears of alienating heterosexual fans and corporate partners. This study supports other scholars’ assertions that safe spaces for queer fans have sometimes been cultivated within women’s sports, despite the persistence of sexual stigma and prejudice (Mock et al., Citation2019; Ravel & Rail, Citation2007; Myrdahl, Citation2011). However, virtually no research to our knowledge has considered how sexual identities shape men’s commitments to sports spectatorship and talking frequently about sports. In sum, it seems that sexual stigma, sexual prejudice, and gendered constructions of “true” fandom that operate within men’s mass spectator sports likely contribute to the marginalization of individuals who identify as a sexual minority and discourage sports spectatorship and frequent conversations about sports – especially among men (Allison, Citation2018; Denison & Kitchen, Citation2015; Symons et al., Citation2017).

Hypotheses

The conceptual framework for this study and previous research suggest:

H1: Perceptions of sports-related mistreatment will be common and individuals who identify as a sexual minority will be more likely than self-identified heterosexuals to realize sports-related mistreatment towards athletes who identify as a sexual minority and towards themselves, personally.

H2: Mixed evidence about generational changes in reports of sports-related mistreatment among individuals who identify as a sexual minority suggest competing hypotheses (Anderson, Citation2014; Denison & Kitchen, Citation2015).

H2a: The youngest generation of individuals who identify as a sexual minority will be less likely to perceive unwelcomeness and personal mistreatment in sports, compared to older generations.

H2b: There will be no generational differences in perceptions of sports-related mistreatment among individuals who identify as a sexual minority.

H3: Individuals who identify as a sexual minority will report less frequent sports participation, spectatorship, and conversation compared to self-identified heterosexuals; recognition of sports-related mistreatment and differing childhood sports histories will partially explain these discrepancies.

H4: Men who identify as a sexual minority will be more likely to disengage from adult sports involvement than women who identify as a sexual minority, compared to their heterosexual counterparts.

Method

Data collection

Data come from the 2018 to 2019 National Sports and Society Survey (NSASS). Respondents were drawn from the American Population Panel (APP), a group of over 20,000 U.S. adults who volunteer to participate in social science research studies. APP participants between 21 and 65 years of age received invitations to complete the NSASS until a quota of 4,000 respondents was obtained; promotional materials highlighted that the survey was designed for everyone to take – not just sports fans. The online survey took approximately an hour to complete and respondents received $35 for their time and efforts. Respondents were from all U.S. states and Washington, D.C., but were disproportionately white, female, and Midwestern (Knoester & Cooksey, Citation2020). The sample for this study contains all NSASS respondents (N = 3,993) because of the wealth of information that they provide across our variables of interest – even when there is some missing data that exists for some variables. To address the missing data, multiple imputation with chained equations over 10 imputations is used.

Survey instrument and created variables

The NSASS survey instrument is far-ranging and notably allows for a comprehensive analysis of sexuality, sports-related mistreatment, and adults’ sports involvement. Below, we describe the background characteristics, independent variables and dependent variables that are employed for the present study.

Background characteristics include age, socioeconomic status, race/ethnicity, and family structure. Age consists of mutually exclusive dummies for being (a) ≤30 years old (reference category), (b) 31–40, (c) 41–50, or (d) 51+. Education dummies reflect having a college degree (reference category), some college, or a high school or less education. Race/ethnicity dummies indicate White (reference category), Black, Latinx, or Other race/ethnicity. Working in paid labor (0 = no; 1 = yes) and household income (in $10,000 s, up to 15) are economic indicators. Family structure dummies indicate being single (reference category), married, or cohabiting. Number of coresident children belonging to the respondent or a partner is also included.

The primary independent variables indicate sexuality. These stem from responses to the question “Do you consider yourself to be…,” with response options that include heterosexual, gay or lesbian, bisexual, or another sexual identity. One dichotomous variable distinguishes individuals who identify as a sexual minority from self-identified heterosexuals (0 = self-identified heterosexual; 1 = self-identified sexual minority). Dummy variables further distinguish sexual identities; these indicate self-identifying as: (a) gay or lesbian, (b) bisexual, (c) another sexual identity, or (d) heterosexual (reference category).

Other independent variables include gender, sports-related mistreatment indicators, and reports of childhood sports histories. Respondents self-identify as male (used as the reference category), female, or nonbinary. Sports-related mistreatment variables include perceptions of LGBT athlete unwelcomeness and reports of personal mistreatment; since they are first employed as dependent variables, they are discussed in detail with the other dependent variables, below. Finally, childhood sports history measures include: (a) reports of the frequency that one thought about sports (coded in hours per week), during a typical week, while growing up (i.e., between the ages of 6 and 18), (b) the extent to which one reported identifying as an athlete (0 = Not at all; 1 = A little; 2 = Somewhat; 3 = Quite a bit; 4 = Very much so), while growing up, and (c) organized sports experiences, while growing up (coded as mutually exclusive dummies for never playing organized sports, playing organized sports but completely dropping out before the end of one’s childhood, or playing organized sports and never dropping out, completely).

Finally, the dependent variables indicate sports-related mistreatment and adults’ sports involvement. First, a measure of felt sexual stigma was formed from responses (1 = strongly disagree, 2 = somewhat disagree, 3 = somewhat agree, 4 = strongly agree) to the statement: “LGBT (Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender) athletes are not welcomed in sports.” This indicator is a general and conservative estimate of felt sexual stigma in sports contexts. It is general because respondents may draw upon their life experiences to assess their perceptions of LGBT athlete inclusivity; it is conservative because sports are idealized as relatively inclusive and meritocratic – sexual stigma and prejudice seem to be heightened among spectators compared to among athletes (Anderson, Citation2014; Denison & Kitchen, Citation2015). To assess the potential for enacted stigma, reports of personal mistreatment in sports are used. The variable derives from responses (0 = no; 1 = yes) to the question: “Have you ever been mistreated in your sports interactions (e.g., called names, been bullied, discriminated against, or abused)?”

Sports involvement includes sports participation, spectatorship, and sports-related conversations over the past year. Sport participation (0 = no; 1 = yes) indicates whether adults reported playing a sport(s) regularly (i.e., more than occasionally). Respondents were encouraged to consider both informal (i.e., in the backyard, amongst friends, or pick-up) and formally (i.e., with coaches, adults in charge, and uniforms) organized sports. Sports spectatorship (0 = no; 1 = yes) denotes having watched or followed a sport, through attending in person. Sports-related conversation indicates the frequency of talking about sports with others (0 = Never; 1 = 1 − 2x a year, 2 = 1 − 2x a month, 3 = 1–2 times a week; 4 = 3 − 5x a week; 5 = Every day or nearly every day).

Sample descriptive characteristics

The sample descriptive characteristics, shown in , indicate that the NSASS respondents are not representative of the U.S. in terms of their gender (e.g., 72% female), educational attainment (e.g., 47% college educated), and race/ethnicity (e.g., 72% White). Nevertheless, there are many respondents from each subgroup, which bolsters the usefulness of the multiple regressions.

Table 1. Descriptive statistics for all variables used in the analyses.

Particularly relevant to this study is that many respondents identify as a sexual minority. Twenty-seven percent of NSASS respondents did not identify as heterosexual; specifically, 9% identified as lesbian or gay, 14% identified as bisexual, and 4% reported another sexual identity. Furthermore, consistent with the first hypothesis, sports-related mistreatment seems common. About 1/3 of respondents reported that they somewhat or strongly agree that LGBT athletes are not welcomed in sports; 38% reported being personally mistreated (e.g., called names, been bullied, discriminated against, or abused, etc.) in sports interactions. Finally, 59% of NSASS adults reported playing a sport(s) regularly, 39% attended a sporting event in person, and the typical frequency of talking about sports was about a few times per month.

Data analysis

The data analysis weights descriptive estimates and then conducts multiple regressions of sports-related mistreatment and other sports experiences to examine the study hypotheses. That is, NSASS estimates are first weighted by age, gender, race, education, work status, marital status, income, and region according to 2018 American Community Survey characteristics. Then, ordinal, binomial, and OLS multiple regressions are conducted. To test for evidence of the hypothesized interactions, full sets of interaction terms were first entered into the regression models for sports-related mistreatment (i.e., age × sexuality) and sports involvement (i.e., gender x sexuality). If a significant interaction emerged, the results were graphed. Then, subsample analyses were performed to further verify understandings. Finally, the most parsimonious full models that illustrate the interactions are presented.

Results

Weighted estimates of sports-related mistreatment and involvement

The first hypothesis anticipated that sports-related mistreatment is common. Indeed, the weighted estimates indicate about 35% expected agreement with LGBT unwelcomeness and 36% expected reports of mistreatment, among U.S. adults. These estimates are very close to the actual reports from the NSASS respondents that were reviewed above and further suggest both that sports-related mistreatment is common, as expected, and that the nonrepresentative sampling of the NSASS did not produce major biases in respondents’ reports. In fact, weighted estimates for the expected levels of sports involvement among all U.S. adults (i.e., estimations that 62% of adults played sports regularly, 38% attended in person, and frequency of talking about sports was just shy of weekly) are also comparable to the actual NSASS reports.

Sexuality and sports-related mistreatment

The initial hypothesis also anticipated that heterosexual adults would be less likely than those who identify as a sexual minority to both recognize mistreatment toward athletes who identify as a sexual minority and to experience personal mistreatment in sports. As shown in , there is support for these expectations. First, as displayed in Model 1, the odds that adults who identify as a sexual minority strongly agree that LGBT athletes are not welcomed in sports, compared to offering another response, are 69% higher than those for self-identified heterosexuals (OR = 1.69, p < .001). As shown in Model 2, adults who identify as lesbian or gay (OR = 2.52, p < .001), bisexual (OR = 1.42, p < .001), or as having another sexual identity (OR = 1.62, p < .01) are each more likely to recognize greater levels of LGBT unwelcomeness than are self-identified heterosexuals. As shown in Model 3, these findings persist even after accounting for childhood sports histories.

Table 2. Results from ordinal and binary logistic regressions of LGBT unwelcomeness and personal mistreatment in sports.

Also, as displayed in Model 4 of , the odds for individuals who identify as a sexual minority reporting sports-related personal mistreatment are 76% higher than those for heterosexuals doing so (OR = 1.76, p < .001). Adults who identify as lesbian or gay (OR = 1.57, p < .001), bisexual (OR = 1.95, p < .001), or as having another sexual identity (OR = 2.10, p < .001) are each more likely to have experienced personal mistreatment in sports. This evidence persists after accounting for childhood sports histories, in Model 6.

Last, potential interactions between sexuality and age are considered as support for competing hypotheses (i.e. Hypotheses 2a and 2b) about whether young adults who identify as a sexual minority are less likely to perceive and experience sports-related mistreatment, compared to older generations. In fact, there is no significant evidence of sexuality by age interactions, which suggests that there are not generational differences (results not shown).

Sexuality and adults’ sports involvement

Finally, relationships between adults’ sexuality and their sports involvement are shown in and . To assess support for Hypothesis 3, the focus of each set of models is first on the extent to which there are sexuality differences in sports involvement; then, it is on the extent to which apparent differences persist after taking into account sports-related mistreatment and childhood sports histories. Potential sexuality and gender interactions are also considered, since the fourth hypothesis anticipated that men, relative to women, who identify as a sexual minority may be more likely to disengage from sports involvement, compared to their heterosexual counterparts.

Table 3. Results from logistic regressions of playing sports regularly and spectatorship, in the past 12 months.

Table 4. Results from OLS regressions of frequency talking about sports with others, in the past 12 months.

As shown in Model 1 of , there is some evidence (OR = 0.85, p < .10) that individuals who identify as a sexual minority are less likely than self-identified heterosexuals to report having played sports regularly over the past year. Adults who identify as bisexual (OR = 0.77, p < .05) or as having another sexual identity (OR = 0.55, p < .001) are significantly less involved, as displayed in Model 2. In Model 3, there is some evidence that perceptions of LGBT unwelcomeness may deter sports participation (OR = 0.91, p < .01). Yet, as seen in Model 4, childhood sports histories seem to be particularly linked to adults’ sports participation; thinking more about sports (OR = 1.01, p < .001), having a stronger athletic identity (OR = 1.48, p < .001), and playing organized sports continually while growing up are each positively associated with adults’ sports participation. In fact, there is only evidence that self-identified heterosexuals are more likely to regularly participate in sports compared to adults who identify as having another sexual identity (OR = 0.66, p < .05), after taking into account childhood sports histories. Finally, there is no evidence of a sexuality and gender interaction for sports participation (results not shown).

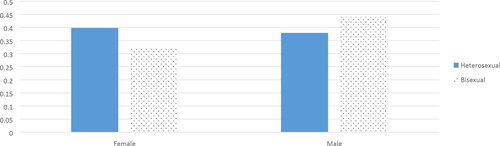

As displayed in Model 5 of , compared to self-identified heterosexuals, individuals who identify as a sexual minority (OR = 0.79, p < .01) are less likely to attend a sports event(s), as expected. It seems that individuals who identify as bisexual (OR = 0.78, p < .05) or as having another sexual identity (OR = 0.45, p < .001) are especially less likely to be sports spectators, as seen in Model 6. As shown in Model 7, there is not evidence that sports-related mistreatment is associated with sports spectatorship, as expected; in fact, personal mistreatment is positively associated with attendance (OR = 1.18, p < .05), presumably as a function of greater exposure to mistreatment opportunities. Furthermore, as displayed in Model 8, the sexuality differences in sports spectatorship hold up, even after accounting for childhood sports histories. Still, childhood sports histories are consistently associated with adults’ sports spectatorship, as expected; relatedly, there is some evidence that the sexuality differences in sports spectatorship are partially reduced in Model 8, as anticipated. Finally, as displayed in Model 9, there is evidence of an interaction between sexuality and gender in reports of sports spectatorship. Yet, unexpectedly, the interaction suggests that women, compared to men, who identify as bisexual may be especially less likely to engage in sports spectatorship, relative to their heterosexual counterparts. An illustration of this interaction is presented in , with all other variables set to their mean values.

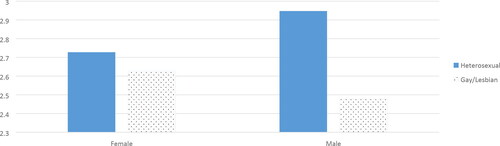

Last, as shown in Model 1 of , individuals who identify as a sexual minority report talking about sports less frequently than do self-identified heterosexuals (b = −0.19, p < .001). Adults who identify as lesbian or gay (b = −0.38, p < .001), bisexual (b = −0.15, p < .05), or as having another sexual identity (b = −0.49, p < .001) each talk about sports less frequently, as displayed in Model 2. These findings largely persist, in Models 3 and 4, although there is some evidence that accounting for childhood sports histories partially reduces the sexuality differences. Finally, as shown in Model 5, an interaction between sexuality and gender exists such that identifying as lesbian or gay is especially associated with a greater decrease in talking about sports among men, compared to among women. This interaction is illustrated in , with all other variables set to their mean values.

Discussion

A focus of leisure studies is evaluating the accessibility, inclusivity, and climates of leisure spaces, with the goal of fostering feelings of belonging, pride, and social connectivity (Cronan & Scott, Citation2008; Kivel & Kleiber, Citation2000; Mock et al., Citation2019). This study sought to advance this aim by examining the relationships between sexuality, sports-related mistreatment, and sports involvement among U.S. adults. Indeed, being involved with sports (e.g., playing, watching, conversing about them) is a dominant form of leisure. Also, sport structures, cultures, and patterns of social interactions have the capacity to offer both positive and negative sports-related experiences and to both encourage and discourage sports involvement – with implications for social justice as well as individuals’ health and well-being (Allison & Knoester, Citation2020; Knoester & Ridpath, Citation2020; Silk et al., Citation2017). Although sport has long been recognized as a particularly heteronormative and patriarchal institution, it has also offered valuable sources of community, identity, and feelings of well-being for individuals with diverse sexual and gender identities. Also, sports contexts are increasingly recognized as becoming more inclusive (Anderson, Citation2014; Anderson et al., Citation2016; Griffin, Citation1998; Myrdahl, Citation2011). Yet, there is a lack of evidence of the extent to which sexuality is currently linked to U.S. adults’ sports-related mistreatment experiences and their patterns of sports involvement. Thus, informed by Herek’s (Citation2009) theorizing about sexual stigma and prejudice as well as previous sport and leisure research, the present study utilized new NSASS data to test four main hypotheses about the current patterns of sports-related mistreatment and sports involvement, the extent to which they are linked to sexuality, and the nature of these associations.

The first hypothesis anticipated that sports-related mistreatment would be common and that individuals who identify as a sexual minority would be more apt to recognize and experience sports-related mistreatment, compared to self-identified heterosexuals. As hypothesized, reports of sports-related mistreatment were common and they were substantially higher among individuals who identified as a sexual minority, compared to self-identified heterosexuals. It appears that over 1/3 of U.S. adults recognize having experienced personal mistreatment in sports interactions and a comparable percentage observe that LGBT athletes are not welcomed in sports. Individuals who identified as lesbian or gay, bisexual, or another sexual identity were especially likely to identify both LGBT (athlete) unwelcomeness and personal mistreatment in sports.

As Herek (Citation2009) and previous sport and leisure research suggest, felt sexual stigma is substantial and perceived mistreatment in sports is common among U.S. adults; this study’s findings better quantify some of this. Also, the disproportionate recognition of felt sexual stigma and personal mistreatment by NSASS respondents who identify as a sexual minority illustrates and quantifies that enacted sexual stigma is problematic and common in sports experiences, too. Thus, this study provides new and compelling quantitative evidence of sexual stigma and prejudice in U.S. sports; clearly, sexual stigma and prejudice in sports need to be reduced and sports need to become more inclusive (Allison, Citation2018; Denison & Kitchen, Citation2015; Myrdahl, Citation2011; Symons et al., Citation2017).

Second, in light of uncertainty about the extent of declines in sexual stigma and prejudice that have occurred in sports and leisure activities, competing hypotheses about whether or not there are generational differences in the realization of sports-related mistreatment were examined. In fact, there were no interactions between age and sexuality in adults’ reports of sports-related mistreatment. Thus, there is no empirical evidence that the recognition of sports-related mistreatment, from among adults who identify as a sexual minority, has declined among recent generations. It may be that even if generational experiences have changed, self-identified sexual minorities of different ages may be equally likely to be aware, and been the recipient, of sports-related mistreatment. Regardless, these findings may be complicated by the potential of more heightened awareness of inequalities among more recent generations and their greater opportunities, but less lifelong exposure, to sports interactions, compared to older generations. Thus, there is a need to continue to inquire about the existence of, and changes in, sports-related mistreatment for individuals who identify as, or are thought to be, sexual minorities. Regardless, reductions in sports-related mistreatment that is linked to sexuality are clearly further needed, along with more general reductions in sexual stigma and prejudice (Denison & Kitchen, Citation2015; Herek, Citation2009).

The third hypothesis expected that adults who identify as a sexual minority would be less involved in sports than their self-identified heterosexual counterparts, in part, due to sexual stigma and prejudice. In fact, the results revealed consistent evidence that individuals who identified as a sexual minority were less likely than self-identified heterosexuals to have played a sport(s) regularly, attended a sports event in person, and talked frequently about sports with others, over the past year. The evidence was most consistent for adults who identified as bisexual or as having another sexual identity. Furthermore, there was slight evidence that adults’ perceptions of LGBT (athlete) unwelcomeness were associated with reduced sports involvement, suggesting that non-inclusive sports contexts may be off-putting, and consistent evidence that adults’ reports of childhood sports histories predicted their sports involvement, in expected ways. Yet, there was quite modest evidence that these reports explained differences in sports involvement by sexuality; thus, there seems to be a need to better understand the sports involvement and sexuality associations. Sexual stigma and prejudice are difficult to measure and it is a challenge to further understand how they may restrict or (dis)encourage sports involvement for individuals with different sexual identities, at different stages in their lives (Denison & Kitchen, Citation2015; Kivel & Kleiber, Citation2000; Symons et al., Citation2017). Also, if NSASS respondents were asked to focus on the sexual stigma and prejudice that surrounds sports spectator and fan contexts, as opposed to simply athletes’ contexts, more evidence of sexual stigma and prejudice may have emerged as influential (Denison & Kitchen, Citation2015; Mock et al., Citation2019). Yet, there may also be some systematic differences in the relative interest in sports, across sexual identities, beyond any influence of sexual stigma and prejudice (Anderson, Citation2014; Denison & Kitchen, Citation2015; Kivel & Kleiber, Citation2000).

Finally, the fourth hypothesis anticipated that sexuality differences in sports involvement would be less pronounced among women, as compared to among men. This was based on the evidence that sports contexts are defined as hegemonically masculine and that the policing of heterosexist ideals has seemed to be more pronounced among men (Denison & Kitchen, Citation2015; Myrdahl, Citation2011; Symons et al., Citation2017). As expected, the results from this study suggest that gay men are especially less likely than heterosexual men to talk frequently about sports; meanwhile, lesbians talk about sports about as frequently as heterosexual women do. Yet, unexpectedly, women who identified as bisexual were particularly less likely than bisexual men to attend sports events, compared to their heterosexual counterparts. It may be that bisexual men can better blend into heteronormative male sports cultures because they can feign being completely heterosexual and they are recognized as appropriately in place, as men (Anderson, Citation2014). This finding suggests a continued need to better understand the intersectional ramifications of sports and leisure experiences as they may be unique for individuals in different social structural locations (Denison & Kitchen, Citation2015; Hawkes, Citation2018; Pavlidis & Fullagar, Citation2013).

Overall, this study is first important because it presents new estimates of U.S. adults’ sports-related mistreatment and sports involvement. The estimates suggest that sports mistreatment and involvement are both very common; thus, they need to be better researched and sports-related mistreatment needs to be recognized and addressed as problematic (Allison & Knoester, Citation2020; Denison & Kitchen, Citation2015; Kosciw et al., Citation2012).

Yet, centrally, this study highlights the elevated levels of sports-related mistreatment toward individuals who identify as a sexual minority and lower levels of sports involvement among such individuals, compared to self-identified heterosexuals. We suspect that these trends are linked, although the evidence from this study offers modest support for this. Nevertheless, the reported associations between U.S. adults’ sexuality, sports-related mistreatment, and sports involvement in this study are generally consistent with assumptions about how sexual stigma and prejudice operate in sports as well as in other leisure activities (Barbosa et al., Citation2020; Denison & Kitchen, Citation2015; Herek, Citation2009; Myrdahl, Citation2011; Symons et al., Citation2017). Movements toward social justice require more welcoming environments for individuals who identify as a sexual minority in all sports and leisure spaces (Pavlidis & Fullagar, Citation2013; Silk et al., Citation2017).

There are some delimitations of this study. First, NSASS respondents were not randomly selected and are not representative of all U.S. adults. Also, 27% of NSASS respondents identified as a sexual minority, which is consistent with recent research that indicates that only 2/3 of U.S. adults now identify as completely heterosexual – but is relatively disproportionate, compared to traditional estimates that suggest that over 90% of the U.S. population is heterosexual (YouGov Poll, Citation2019; Zipp, Citation2011). Thus, additional research about sexuality, sports-related mistreatment, and sports involvement is needed, with different samples. Also, this study relies on secondary cross-sectional data, many single-item measures and dichotomous variables, and retrospective accounts; more comprehensive measures and prospective accounts from multiple sources are preferable – especially if they are combined with longitudinal data analyses that could enhance causal evidence. Relatedly, the study is unable to analyze detailed information about respondents’ subjective perceptions of sexual stigma and prejudice and how it may or may not have impacted their sports involvement, over the life course. Furthermore, it is unable to distinguish perceptions of inclusivity – for example, for each of LGBT athletes – from among athletes, fans, sport industry workers, and other roles, within different sports contexts.

Nonetheless, this study offers important contributions to understanding sexuality, sports-related mistreatment, and adults’ sports involvement. It reaffirms the usefulness of Herek’s (Citation2009) theorizing of sexual stigma and prejudice and contributes new estimates of sports-related mistreatment. It details discrepancies in the recognition of mistreatment across sexualities, showing consistent evidence that self-identified heterosexuals are less likely to recognize sports-related mistreatment than individuals who identify as a sexual minority. The research also notes reduced levels of adults’ sports involvement in playing, spectating, and talking about sports for individuals who identify as a sexual minority, compared to self-identified heterosexuals. Sports and leisure contexts are in need of continued growth toward inclusion, appreciation, and the nurturing of allyships. Future work should continue to (re)consider the climate of sports and other leisure contexts and how they can be modified to be more welcoming, open, and inclusive to all individuals, regardless of their sexuality.

Acknowledgments

The NSASS also relied upon the willingness of thousands of American Population Panel participants to complete the survey and upon the efforts of hundreds of adults and students who were willing to test and help edit the survey instrument. Thank you.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Allison, R. (2018). Kicking center: Gender and the selling of women’s professional soccer. Rutgers University Press.

- Allison, R., & Knoester, C. (2020). Gender, sexual, and sports fan identities. Sociology of Sport Journal, 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1123/ssj.2020-0036

- Anderson, E. (2005). In the game: Gay athletes and the cult of masculinity. State University of New York Press.

- Anderson, E. (2011). Masculinities and sexualities in sport and physical cultures: Three decades of evolving research. Journal of Homosexuality, 58(5), 565–578. https://doi.org/10.1080/00918369.2011.563652

- Anderson, E. (2014). 21st Century Jocks: Sporting men and contemporary heterosexuality. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Anderson, E., Magrath, R., & Bullingham, R. (2016). Out in sport: The experiences of openly gay and lesbian athletes in competitive sport. Routledge.

- Bahk, C. M. (2000). Sex differences in sport spectator involvement. Perceptual and Motor Skills, 91(1), 79–83. https://doi.org/10.2466/pms.2000.91.1.79

- Baiocco, R., Pistella, J., Salvati, M., Ioverno, S., & Lucidi, F. (2018). Sports as a risk environment: Homophobia and bullying in a sample of gay and heterosexual men. Journal of Gay & Lesbian Mental Health, 22(4), 385–411. https://doi.org/10.1080/19359705.2018.1489325

- Barbosa, C., Ribeiro, N. F., & Liechty, T. (2020). “I’m being told on Sunday mornings that there’s nothing wrong with me”: Lesbian’s experiences in an lgbtq-oriented religious leisure space. Leisure Sciences, 42(2), 224–242. https://doi.org/10.1080/01490400.2018.1491354

- Birrell, S., & Richter, D. M. (1987). Is a diamond forever? Feminist transformations of sport. Women’s Studies International Forum, 10(4), 395–409. https://doi.org/10.1016/0277-5395(87)90057-4

- Cahn, S. K. (2015). Coming on strong: Gender and sexuality in women’s sports (2nd ed.). University of Illinois Press.

- Calzo, J. P., Roberts, A. L., Corliss, H. L., Blood, E. A., Kroshus, E., & Austin, S. B. (2014). Physical activity disparities in heterosexual and sexual minority youth ages 12–22 years old: Roles of childhood gender nonconformity and athletic self-esteem. Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 47(1), 17–27. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12160-013-9570-y

- Carter, C., & Baliko, K. (2017). ‘These are not my people’: Queer sport spaces and the complexities of community. Leisure Studies, 36(5), 696–707. https://doi.org/10.1080/02614367.2017.1315164

- Cavalier, E. S., & Newhall, K. E. (2018). ‘Stick to soccer’: Fan reaction and inclusion rhetoric on social media. Sport in Society: Cultures, Commerce, Media, Politics, 21(7), 1078–1095. https://doi.org/10.1080/17430437.2017.1329824

- Cavalier, E. S. (2016). I don’t ‘look gay’: Different disclosures of sexual identity in men’s, women’s, and co-ed sport. In J. Hargreaves & E. Anderson (Eds.), Routledge handbook of sport, gender and sexuality (pp. 300–308). Routledge.

- Cavalier, E. S. (2019). Conceptualizing gay men in sport. In V. Krane (Ed.), Sex, gender, and sexuality in sport: Queer inquiries (pp. 87–104). Routledge.

- Cronan, M. K., & Scott, D. (2008). Triathlon and women’s narratives of bodies and sport. Leisure Sciences, 30(1), 17–34. https://doi.org/10.1080/01490400701544675

- Denison, E., Kitchen, A. (2015). Out on the Fields: The First International Study on Homophobia in Sport. Nielsen, Bingham Cup Sydney 2014, Australian Sports Commission, Federation of Gay Games. www.outonthefields.com

- Dionigi, R. (2006). Competitive sport as leisure in later life: Negotiations, discourse, and aging. Leisure Sciences, 28(2), 181–196. https://doi.org/10.1080/01490400500484081

- Dolance, A. (2005). “A whole stadium full”: Lesbian community at women's national basketball association games. The Journal of Sex Research, 42(1), 74–83. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224490509552259

- Elling, A., & Janssens, J. (2009). Sexuality as a structural principle in sport participation. International Review for the Sociology of Sport, 44(1), 71–86. https://doi.org/10.1177/1012690209102639

- Elling-Machartski, A. (2017). Extraordinary body self-narratives: Sport and physical activity in the lives of transgender people. Leisure Studies, 36(2), 256–268. https://doi.org/10.1080/02614367.2015.1128474

- Gill, D. L., Morrow, R. G., Collins, K. E., Lucey, A. B., & Schultz, A. M. (2010). Perceived climate in physical activity settings. Journal of Homosexuality, 57(7), 895–913. https://doi.org/10.1080/00918369.2010.493431

- Griffin, P. (1998). Strong women, deep closets: Lesbians and homophobia in sport. Human Kinetics.

- Griffin, P. (2012). LGBT equality in sports: Celebrating our successes and facing our challenges. In G. B. Cunningham (Ed.), Sexual orientation and gender identity in sport: Essays from activists, coaches and scholars (pp. 1–12). The Center for Sport Management Research and Education.

- Hawkes, G. L. (2018). Indigenous masculinity in sport: The power and pitfalls of rugby league for Australia’s Pacific Island diaspora. Leisure Studies, 37(3), 318–330. https://doi.org/10.1080/02614367.2018.1435711

- Hekma, G. (1998). “As long as they don't make an issue of it”: Gay men and lesbians in organized sports in The Netherlands. Journal of Homosexuality, 35(1), 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1300/J082v35n01_01

- Herrick, S. S. C., & Duncan, L. R. (2018). A qualitative exploration of LGBTQ+ and intersecting identities within physical activity contexts. Journal of Sport & Exercise Psychology, 40(6), 325–335. https://doi.org/10.1123/jsep.2018-0090

- Herek, G. M. (2009). Sexual stigma and sexual prejudice in the United States: A conceptual framework. In D. A. Hope (Ed.), Nebraska symposium on motivation: Vol. 54. Contemporary perspectives on lesbian, gay, and bisexual identities (pp. 65–111). Springer Science + Business Media. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-0-387-09556-1_4

- Jones, J. M. (2015). As industry grows, percentage of U.S. sport fans steady. Gallup. https://news.gallup.com/poll/183689/industry-grows-percentage-sports-fans-steady.aspx

- Kian, E. M., Anderson, E., Vincent, J., & Murray, R. (2015). Sport journalists’ views on gay men in sport, society and within sport media. International Review for the Sociology of Sport, 50(8), 895–911. https://doi.org/10.1177/1012690213504101

- Kivel, B. D., & Kleiber, D. A. (2000). Leisure in the identity formation of lesbian/gay youth: Personal, but not social. Leisure Sciences, 22(4), 215–232. https://doi.org/10.1080/01490409950202276

- Knoester, C., Cooksey, E. C. (2020). The National Sports and Society Survey methodological summary. https://doi.org/10.31235/osf.io/mv76p

- Knoester, C., & Ridpath, B. D. (2020). Should college athletes be allowed to be paid? A public opinion analysis. Sociology of Sport Journal, 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1123/ssj.2020-0015

- Kosciw, J. G., Greytak, E. A., Zongrone, A. D., Clark, C. M., & Truong, N. L. (2018). The 2017 National School Climate Survey: The experiences of lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer youth in our nation’s schools. GLSEN.

- Kosciw, J. G., Greytak, E. A., Bartkiewicz, M. J., Boesen, M. J., & Palmer, N. A. (2012). The 2011 National School Climate Survey: The experiences of lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer youth in our nation’s schools. GLSEN.

- Krane, V. (2019). Introduction: Lgbtiq people in sport. In V. Krane (Ed.), Sex, gender, and sexuality in sport: Queer inquiries (pp. 1–12). Routledge.

- Lenskyj, H. J. (2003). Out on the field: Gender, sport and sexualities. Women’s Press.

- Mann, M., & Krane, V. (2018). Inclusion and normalization of queer identities in women’s college sport. Women in Sport and Physical Activity Journal, 26(2), 76–88. https://doi.org/10.1123/wspaj.2017-0033

- Mann, M., & Krane, V. (2019). Inclusion or illusion? Lesbians’ experiences in sport. In V. Krane (Ed.), Sex, gender, and sexuality in sport: Queer inquiries (pp. 69–86). Routledge.

- Mock, S. E., Misener, K., & Havitz, M. E. (2019). A league of their own? A longitudinal study of ego involvement and participation behaviors in LBGT-focused community sport. Leisure Sciences, 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/01490400.2019.1665599

- Myrdahl, T. M. (2011). Lesbian visibility and the politics of covering in women’s basketball game spaces. Leisure Studies, 30(2), 139–156. https://doi.org/10.1080/02614367.2010.513714

- Pavlidis, A., & Fullagar, S. (2013). Narrating the multiplicity of “Derby Grrrl”: Exploring intersectionality and the dynamics of affect in roller derby. Leisure Sciences, 35(5), 422–437. https://doi.org/10.1080/01490400.2013.831286

- Petty, L., & Trussell, D. E. (2018). Experiences of identity development and sexual stigma for lesbian, gay, and bisexual young people in sport: ‘Just survive until you can be who you are’. Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health, 10(2), 176–189. https://doi.org/10.1080/2159676X.2017.1393003

- Piedra, J., García-Pérez, R., & Channon, A. G. (2017). Between homohysteria and inclusivity: Tolerance towards sexual diversity in sport. Sexuality & Culture, 21(4), 1018–1039. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12119-017-9434-x

- Ravel, B., & Rail, G. (2007). On the limits of “gaie” spaces: Discursive constructions of women’s sport in quebec. Sociology of Sport Journal, 24(4), 402–420. https://doi.org/10.1123/ssj.24.4.402

- Silk, M., Caudwell, J., & Gibson, H. (2017). Views on leisure studies: Pasts, presents & future possibilities? Leisure Studies, 36(2), 153–162. https://doi.org/10.1080/02614367.2017.1290130

- Symons, C. M., O’Sullivan, G. A., & Polman, R. (2017). The impacts of discriminatory experiences on lesbian, gay, and bisexual people in sport. Annals of Leisure Research, 20(4), 467–489. https://doi.org/10.1080/11745398.2016.1251327

- Theberge, N. (2000). Higher goals: Women's ice hockey and the politics of gender. State University of New York Press.

- Toomey, R. B., & Russell, S. T. (2013). An initial investigation of sexual minority youth involvement in school-based extracurricular activities. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 23(2), 304–318. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-7795.2012.00830.x

- YouGov Poll. (2019). LGBTQ pride – kinsey. https://today.yougov.com/topics/lifestyle/articles-reports/2019/06/20/kinsey-scale-sexuality-millennials-2019-poll

- Zipp, J. F. (2011). Sport and sexuality: Athletic participation by sexual minority and sexual majority adolescents in the U.S. Sex Roles, 64(1–2), 19–31. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-010-9865-4