Abstract

Inclusion and diversity have become paramount within the festival sector and beyond, often focusing on bringing together a diverse group of people within one space. Within leisure studies, there has been a longstanding interest in leisure as spaces where people meet “others.” Nevertheless, previous research found that physical proximity is often not sufficient to enable social mixing. Adopting a cross-disciplinary approach combining urban planning and design with cultural sociology and leisure studies, this article addresses how music festival organizers produce spaces of encounter within festival spaces. The study is based on semi-structured interviews with 31 organizers of music festivals in Rotterdam. Findings indicate that organizers use their knowledge of spatial design and symbolic boundaries to stimulate or block movement of audience groups, which affects segregation and mixing of audience groups within a festival. Spaces of encounter therefore are consciously designed through symbolic and social boundaries that have spatial consequences.

1. Introduction

Many music festivals in Rotterdam have put in efforts to diversify and create inclusive spaces (Berkers et al., Citation2018). Even more so: they are expected to. There has been a move toward the “responsibilization” of festivals, which means that they are supposed to constitute sites of “good governance” for instance related to diversity and inclusion (Woodward et al., Citation2022). Social mixing has become part of this story. Festivals are often defined as periodically recurrent, social occasions “in which, through a multiplicity of forms and a series of coordinated events, participate directly or indirectly and to various degrees, all members of a whole community, united by ethnic, linguistic, religious, historical bonds, and sharing a worldview” (Cudny, Citation2016, p. 16). Much like other public spaces (Peters, Citation2010), festivals are leisure spaces where people are co-present with strangers and are therefore much more likely to interact with “others.” Nevertheless, whereas music festivals can be spaces where people from diverse backgrounds meet, they have also been found to be spaces where people with similar backgrounds come together in a shared celebration (Mair & Duffy, Citation2017; Wilks, Citation2011). Even though attracting a diverse audience remains a relevant research topic, less attention has been paid to how, when and where social mixing can occur at festivals. As previous research found that physical proximity does not equal social mixing (Lees, Citation2008), questioning how and why some public spaces could be more conducive to encounters taking place than others is of significance.

Moreover, festivals are being purposefully designed for people to meet and connect with others (Cudny, Citation2016), mostly focusing on so-called “conviviality” (Fincher & Iveson, Citation2008), referring to more temporary, in-situ identifications. Consequently, festival organizers play a key role in creating a space that allows for encounters with “others” (Walters et al., Citation2021). Placing our research within critical event studies, we aim “to highlight relationships of power and subordination at work within events” (Lamond & Platt, Citation2016, p. 8). This is especially important as organizers’ vision on the production of space and diversity remains understudied (Dashper & Finkel, Citation2020; Laing & Mair, Citation2015). Drawing on semi-structured interviews with 31 organizers of Rotterdam-based music festivals, we therefore explore how music festival organizers design spaces of encounter within festivals. We focus on the practices organizers employ, referring to their use of programming and the production of space, to build spaces that may facilitate social mixing. The analysis reveals the spatial representation of taste across spaces within music festivals, as well as how these spatial boundaries can be crossed through programming and spatial design.

We draw from cross-disciplinary literatures combining leisure studies, cultural sociology and urban planning and design. Within leisure studies there has been a long-standing interest in leisure, space and social identity. Leisure spaces are important for people to express their individual and social identities, which are “formed in daily practices and emerge in spatial settings” (Peters, Citation2010, p. 420). We explore how the design of a space can contribute to the expression of certain identities over others and how mixing across social groups can be stimulated, at least in the perception of the organizers. On the one hand, cultural sociology adds to our understanding of mixing in public space by allowing for a spatial perspective on taste, showing how symbolic boundaries can have spatial consequences through festival organizers’ design choices. Organizers consciously use their tacit knowledge of symbolic and social boundaries to design festival spaces. At the same time, we consider urban design and planning by showing how considerations regarding taste and symbolic boundaries can be used in spatial designs. Providing a new perspective on social mixing in public spaces, we consider how music festival organizers try to influence the consumer experience of festivals and mixing occurring there by strategically designing these spaces. In doing so we show how symbolic boundaries related to music can be used consciously in urban design to bring people together or drive them apart.

2. Concepts and theory

2.1. Symbolic and social boundaries: music and festivals

From cultural sociology we know that music can rhythmically and ritually bond groups of people (Mair & Duffy, Citation2017), while it can also divide people through symbolic and social boundaries. Symbolic boundaries are “conceptual distinctions made by social actors to categorize objects, people, practices, and even time and space” (Lamont & Molnár, Citation2002, p. 168). From a Bourdieusian perspective, people use cultural capital, such as cultural attitudes, preferences and behaviors, as a source of social selection to exclude and unify people with a similar cultural taste (Lamont & Molnár, Citation2002). These lifestyle and consumption patterns are expressed in leisure venues such as music festivals (Bennet & Woodward, Citation2014), for example through clothing, hairstyles and dancing, thereby performing people’s social positions. When these symbolic boundaries are widely agreed upon, they can take the form of social boundaries, which “are objectified forms of social differences manifested in unequal access to and unequal distribution of resources (material and nonmaterial) and social opportunities” (Lamont & Molnár, Citation2002, p. 168). Existing research has shown that there is some correspondence between esthetic (or symbolic) boundaries, for instance music genres, and social boundaries of race, gender and class (Roy, Citation2004; Schaap & Berkers, Citation2019;). For example, previous research shows how “good” rock music is often (implicitly) classified as white and male (Schaap & Berkers,2019). Festivals, then, can be seen as spaces where classed, gendered and racialized identities are performed.

Following Bourdieusian and Durkheimian thinking, festivals would most commonly be seen as bonding experiences, solidifying rather than bridging symbolic and social boundaries. From a Bourdieusian perspective, people sharing similar lifestyles and cultural capital would come together. This could be related to bonding social capital which is “inward looking, reinforcing exclusive identities and promoting homogeneity” (Wilks, Citation2011, p. 10). This would thus be about increasing solidarity between people who are already similar. Similarly, from a Durkheimian perspective festivals would create a sense of community and belonging because of their rhythm and rituals (Mair & Duffy, Citation2017), related to the role of music (Bennet & Woodward, Citation2014). Rituals would contribute to a charged sociality in which people feel bound to a group they are already familiar with. Even though these perspectives mostly argue for festivals as sites where bonding takes place, previous research has found moments of social mixing at festivals (Mair & Duffy, Citation2017). Only a Durkheimian perspective can partially help us understand why this is the case. Namely, a ritual does not necessarily reinforce existing boundaries but could also help re-engineering social life. As Leal (Citation2016) argues: “Durkheim did not completely exclude the possibility of ritual as a site for the making, remaking and unmaking of groups” (p. 596). From this perspective, there might be a chance for bridging social capital to occur at festivals, which promotes links between various social categories (Wilks, Citation2011). Nevertheless, neither perspective provides a satisfactory understanding for how, when and where boundaries can be crossed and how the design of a festival may play a role in this.

2.2. Space and types of encounters

Cultural sociology does not help us understand how social mixing can occur within a space. We therefore apply a spatial perspective focusing on the concept of encounters. An encounter can be defined as “a face-to-face meeting between adversaries or opposing forces” (Wilson, Citation2017, p. 452), which means that they are inherently about crossing boundaries. There are many types of places where encounters can occur, including streets, parks, markets, nurseries, gyms, school playgrounds, public transport, food sharing initiatives and other projects based in communities and neighborhoods (Phillips, Citation2014). These spaces are often differentiated in micro-public, semipublic and public spaces, based on the type of encounter likely to occur, the depth and duration of contact, and the extent to which the encounter is consciously organized. Micro-publics are often seen as ideal spaces for encounters to occur, as these spaces are often more organized, consciously stimulating diverse groups to intermingle, and are considered to lead to more intensified forms of contact because of the depth and duration of contact occurring there. Think for instance about recurring interactions between people at communal gardens, workplaces, schools and theater groups. Encounters within public spaces, on the other hand, are argued to be more incidental and fleeting in nature (Valentine, Citation2008).

Festivals fall right in between these categories, as they are often purposefully organized for people to enjoy, meet and connect (Cudny, Citation2016), while at the same time being too crowded and temporary for meaningful encounters to occur. Even more than other leisure activities in public spaces, such as parks (Peters, Citation2010), festivals are purposefully designed for people to express their diverse backgrounds and identities (Bennet & Woodward, Citation2014). Fincher and Iveson (Citation2008) argue for the notion of festivals as “sites of conviviality.” This term better accounts for interactions that are focused on a more temporary identification with others and the creation of some sense of familiarity, mainly referring to the sense of being “at ease with difference” (Ganji & Rishbeth, Citation2020), where diversity becomes the new norm. These fleeting encounters might then contribute to a spillover and produce more meaningful social relationships that continue to have an emotional relevance after the event (Berkers & Michael, Citation2017).

2.3. The production of diverse (festival) spaces

Nevertheless, the festival spaces where encounters may occur do not come into existence naturally. They are built based on the organizers’ vision (an active role that was foregrounded by Sharpe, Citation2008). For positive encounters to occur at festivals, they must be planned and managed to allow festival attendees to share the festival atmosphere (Mair & Duffy, Citation2017). Here, we therefore draw on the concept of “curated sociability” (Rishbeth et al., Citation2019), which “reflects intentional action rather than simply observations of ‘what happens’” (p. 127). As we will show, the design of festivals draws on a more active framing of encounters in public space, which this concept reflects. Since we are focusing on spaces where conviviality is more common (Fincher & Iveson, Citation2008) and we are considering the design of spaces, we will use the concept “designed conviviality” instead.

Even though their perspective has been understudied, earlier research can give us some indication as to how organizers think they can bring together diverse groups of people within a festival. For example, Laing and Mair (Citation2015) found that organizers felt they could produce inclusive spaces by including local suppliers, authorities and volunteers, partnerships with community-based organizations, offering internships and volunteer programs, marketing strategies to reach marginalized groups, providing free or discounted tickets and showcasing local talent and live broadcasts. Organizers can also put in place initiatives to keep their festival accessible to people with low income and individuals with disabilities. Programming might also play a role in creating diverse events (Sharpe, Citation2008).

Nevertheless, most of these strategies imply bringing together diverse groups in one space, whereas earlier research has shown that physical closeness of diverse groups does not equal social mixing (Peters, Citation2010). An area of research that focuses specifically on physical proximity and the possibility of social mixing is that of the effects of gentrification, where the state invests in buildings and houses that will attract the middle-class, while diminishing the amount of social rent housing within neighborhoods (Uitermark et al., Citation2007). Most studies find that bringing diverse groups of people within physical proximity, does not automatically lead to social mixing. Social networks amongst neighbors are likely to still be socially segregated, mostly along the lines of socioeconomic status and ethnicity (Lees, Citation2008). Physical proximity may not be enough, as people still need to have similar backgrounds or common interests for interactions to become stronger (Van Beckhoven & van Kempen, Citation2003). Similarly for festivals, people primarily come together to celebrate a shared lifestyle (Bennet & Woodward, Citation2014) rather than meeting “others.” As bringing together people within one (festival) space apparently is not enough to foster encounters, we need to consider the strategies organizers can employ in building festival spaces that may be conducive to encounters taking place. Moreover, social mixing may require different strategies within more temporal festival spaces.

2.4. Urban design and the production of space

To understand how a space and its physical structuring can affect behavior, and thus encounters, we turn to urban planning and design. Thwaites (Citation2001) describes the application of urban planning and design as beneficial “particularly where social inclusion objectives are to be met” (p. 253). Three factors are important in the design of spaces related to encounters: 1) change, 2) movement, and 3) safety (Ganji & Rishbeth, Citation2020, p. 14).

First, change can entail a variety of structures and demarcations but is focused on design options that physically distinguish spaces from one another. Edges, thresholds, changes of levels or corridors can be used to construct a clear hierarchy between more and less important spaces (Gehl, Citation2010) or mark a passage from “here” to “there” (Thwaites, Citation2001). Distinguishing smaller spaces within a larger space creates more intimate, approachable spaces where people will want to be (Gehl, Citation2010; Stevens & Shin, Citation2014). Encounters are made easier that way, because when people share spaces of activity and proximity they feel “they have a license to speak with others” (Anderson, Citation2004, p. 18). Through marking and detailing of structure people feel a sense of belonging to certain areas within their neighborhood while outsiders will feel like visitors (Gehl, Citation2010). The same may be occurring within festivals, where people feel a sense of belonging only to particular spaces within a festival.

Secondly, diverse and intersecting movement is important for conviviality. Spaces with varied rhythms of movement, such as parks and streets, provide the opportunity for encounters as people engage in activities of lingering, people-watching and playing (Ganji & Rishbeth, Citation2020). More relaxed walking at festivals increased opportunities for informal social interaction (Stevens & Shin, Citation2014). Movement can be stimulated and “is more likely when choices have to be made, when imagination is exercised, and attention attracted” (Thwaites, Citation2001, p. 249) and when one is encouraged to explore (Gehl, Citation2010). Moreover, the presence of visual devices helps to emphasize a sense of direction as well as providing orientation aids (Thwaites, Citation2001). Movement can also be discouraged. For example, if one can see the whole route at once before starting to walk, it will feel as a “tiring length.” If, however, the route is “divided into manageable segments, where people can walk from square to square” (Gehl, Citation2010, p. 127) this naturally breaks up the walk.

Third is the protection and safety of people within a space (Gehl, Citation2010). Safety is enhanced when people can easily find their way around and can distinguish important places. Physical demarcations enhance security and ability to read a situation. Feeling safe is important for conviviality too, as that requires people to feel relaxed, both mentally and physically, and open to the unexpected (Ganji & Rishbeth, Citation2020). As we will show, safety is an important consideration in festival design too.

3. Data and methods

All 31 participants are organizers of popular music festivals in Rotterdam. Rotterdam is an interesting case for two reasons. Firstly, Rotterdam is often considered a superdiverse city, where majorities and minorities can no longer be distinguished (Scholten et al., Citation2019). Secondly, Rotterdam profiles itself as a festival city (Van der Hoeven, Citation2016). Music festivals were selected in three steps, based on the diverse-case method, assuring “maximum variance along relevant dimensions” (Gerring, Citation2008, p. 8) First, from a dataset on festivals in the Netherlands between 2008 and 2018 acquired from festivalinfo.com, we selected all festivals taking place in Rotterdam. We used this dataset to familiarize ourselves with the festival landscape with available data at the start of this project in 2019. Second, we selected festivals focusing on five criteria which were based on relevant literature and further limited to relevant criteria to this research (Cudny, Citation2016; Paleo & Wijnberg, Citation2006), namely: 1) pricing (paid or unpaid), 2) genres (multi or focused), 3) scale (large, medium or small), 4) maturity (number of editions) and 5) diversity goals. Then, a representative of a local municipal festival organization was consulted on the representativeness of this selection and possible additions. This resulted in a focus on four music festivals: Blijdorp, Magia, Metropolis and Rotterdam Unlimited. During our research the selection was broadened to include organizers of festivals that were deemed important to broaden our understanding of festivals and diversity within Rotterdam (for a more extensive description of most festivals see Swartjes & Berkers, Citation2022).

Participants had different roles within festival organization, ranging from business direction to artistic direction, from programming to production, artist handling or marketing and communication (see ). As festival teams are usually small, these roles often overlap. The selection of interviewees within a team was based on their roles, availability and information festival directors provided. Our final selection is indicative of the racialized, gendered and classed nature of the profession of festival organization. Most participants identified as white and male and had completed higher education. Because of the broad selection of music festivals, we would argue that the sample has not caused the overrepresentation of these backgrounds, but that this is inherently part of the festival organization profession.

Table 1. Festival organizers’ roles and music festivals (N = 31).

Semi-structured interviews took place between January 2019 and June 2021. Due to the restricting measures during COVID-19 interviews took place live, online or by telephone. Because of time constraints, some organizers were interviewed on multiple occasions, resulting in 34 interviews. Fifteen interviews took place live, seventeen took place digitally and two via telephone. Interviews lasted between 1 and 3 hours, with most interviews lasting about 90 minutes. In addition, four walking interviews were conducted with festival directors, including Blijdorp, Metropolis and Rotterdam Unlimited. These interviews were approached inductively, letting the participants come up with the themes as we walked. This helped to broaden our understanding of how festival organizers perceive and produce space.

All interviews started with an informal chat in which the aims and background of the research were discussed. Participants read and signed the consent form before the interview and consent was verified before starting. Participants were made aware that in publications the name of the festival they work for and their role in it would be mentioned. Interviews were conducted by the first author, who identifies as white, cis-gender female. Trustworthiness, meaning the way in which our study captures the context as it was constructed between the researcher and participants (Peters, Citation2010), was considered in two ways. First, by thoroughly exploring the Rotterdam festival context through a considerable number of festival organizers we have made a detailed account of their perception of the local festival industry, ensuring the possible (theoretical) transferability of the research findings. Moreover, interviewees had the opportunity to review quotes used in publications, which did not result in any alterations.

Interview themes included background of participants, festival characteristics and work processes taking place before, during and after the festival related to marketing and promotion, designing the festival space and programming. Organizers knew that the research was about diversity, but this was not brought up by the interviewer until the end. This strategy helped to uncover when diversity mattered in the organization process. All interviews were audio recorded and transcribed verbatim. The interviews were coded in Atlas.ti in three steps. Firstly, the coding of the first 10 interviews was approached inductively, trying to find central themes in the data. Secondly, codes resulting from the first round were organized in themes and applied to the first 10 interviews. Lastly, all interviews were coded using organizing themes while including new themes when deemed necessary. The organizing themes resulting from coding all interviews were compared using a code tree (available on request).

4. Findings

4.1. Symbolic and social boundaries

Organizers show a keen awareness of the symbolic boundaries associated with different music genres and the audience types these genres attract. Although they mostly describe this connection in generic terms, for example stating that a “certain type of people [is] attracted to that [music genre]” [VRIJ_F01], many organizers see connections between various genres and social boundaries of mostly age/generation, race-ethnicity and social class (Schaap & Berkers, Citation2019).

Hip hop, grime, urban, skatepunk, emo, techno and electronic music are seen as genres for younger people, whereas house and rock are argued to be for older people. Besides age and generation, organizers often connect genres to race-ethnicity. Interestingly, mostly when they connect a particular music genre to ethno-racial categories they seem to be hesitant in their phrasing and say things such as “not to be dickish but […] there’s more people with a dark skin colour there” [EEN_H02], which may be due to sensitivity surrounding the topic. Several music genres are connected to white audiences, such as punk, salsa, electronic, world-music, techno and singer-songwriter, where hip hop, grime, reggae, urban and soul are connected to black audiences. One organizer for example discusses the similarity in audiences for reggae and hip-hop music: “The biggest target audience in the Netherlands is with people from a non-Western background” which he earlier also related to the genre’s history when stating that “they’re both genres born in struggle. Right, struggle of the black community within America and Central America […] they both sing about that struggle and that is something these target audiences find each other in” [EEN_H01]. Here, this organizer unifies these audience groups by drawing symbolic boundaries of taste, while at the same time connecting these boundaries to patterns of segregation (Lamont & Molnár, Citation2002).

Third, some genres are connected to social class, which can be reflected in for example peoplés income, occupation, educational level and cultural capital (Savage et al., Citation2015). For instance, techno is seen by one organizer as a music genre connected to people with low cultural capital, stating that “techno just attracts another […] audience. Yeah maybe it’s mean to say but a bit [break] more simple yeah how [mumbles/laughs] I’m trying to find a decent word for that. People that maybe look a bit less for something deeper” [BF_F02]. World music is seen by some organizers as a genre for people with higher educational levels.

4.2. Spatial organization of taste (stages as islands)

These symbolic distinctions between genres based on audience groups have spatial implications. When designing festivals, organizers think of the festival space as consisting of separate stages and locations, or even “islands,” each with their own function: “I think a lot of festivals see their stages as separate islands, and every island needs to be right” [CON_F01]. These distinct spaces are separated by designing them along spatial, symbolic and social boundaries.

The stages are spatially separated by physically demarcating the area, reminding us of the dimension “change” where certain spaces within a larger area are “enclosed” and made to feel more intimate (Gehl, Citation2010). As an organizer states: “you have to be able to step into each stage” [BF_F01]. Even though organizers from festivals that use existing locations consider this too, especially organizers from festivals where stages are built seem to consider how to create a space in which people will behave in certain ways and that feels intimate (Gehl, Citation2010). This can for example be done by clearly demarcating the area, naturally creating an island:

“With containers we chose to demarcate all those stages so that you force people to come together in an area in front of a DJ. You’re pushing them together. And then you place something above their heads and in their backs […] you try to build stages where people feel comfortable as fast as possible and start to dance” [CON_F01]

Enclosure thereby ensures a high social density (Stevens & Shin, Citation2014). Islands are also facilitated through sound as organizers want to avoid overlap in sounds from different stages “this [stage] is very close to that one and if you blow that way then you will overlap in sound with that stage” [RU_F02]. These demarcations could affect the sense of belonging people feel to parts of the festival space, sensing that they do belong to certain parts of the festival space while not to others (Gehl, Citation2010).

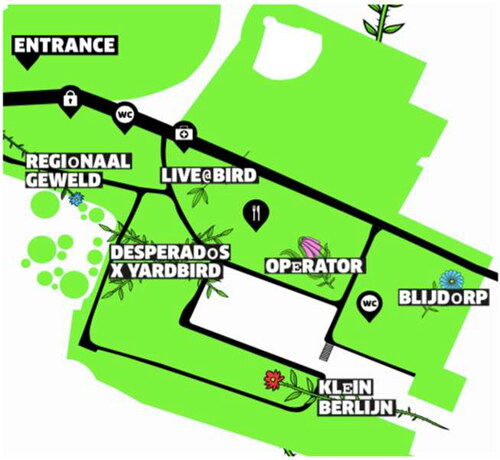

Organizers use their tacit knowledge of symbolic and social boundaries in designing separate areas, connecting specific genres or programming partners to separate stages or locations, based on the variation they expect in the type of audience the genres attract. Thereby, they create conceptual distinctions between varying spaces (Lamont & Molnár, Citation2002). An example of a festival that uses this strategy in terms of stages is Blijdorp. As shown below in the festival map that was shared by the festival right before the 2019 edition, the festival had six stages (Blijdorp Festival, Citation2019). Some of these stages are related to local program partners, for instance Bird with a live stage, Yardbird with an urban corner and Operator with electronic music ().

Figure 1: Festival map Blijdorp Festival, Citation2019.

When discussing their stages, the director argues:

“We don’t have four techno, deep-house, or like that stages, right, we choose to bring different cultural groups together […] Really through the partners we work with we speak to a completely different group of people at the stages we have”.

Most importantly, so he reasons, this is because of the hosts and the music genres attached to them, which attract varying types of audiences:

“they’re [the hosts] just bringing in their own audiences. That’s the most important thing. […] you know they just have a specific Yardbird audience, if you would have to describe that for example those are ladies between 20 and uh- 27. Who like it when John Fraser or Snelle comes. A lot of desperados is being drunk there. […] at Operator you have more people they bring in more audiences that’s a bit more credible”

This organizer connects the taste of particular audience groups to social boundaries of age, gender and cultural capital and he distinguishes between groups of people who like listening to different types of music at different stages. By considering social and symbolic boundaries in their festival design, these boundaries come to be spatially represented within the festival space. What can be done by organizers to bridge these boundaries from their perspective?

4.3. Designing movement to foster encounters

While programming and the production of space are used to distribute and separate audience groups within festivals, the same factors are used to prevent genre-specific segregation within the festival and thereby stimulate social mixing. For instance, the director of Rotterdam Unlimited, which strongly focuses on cultural diversity, stated that:

“when you make sure that the programming is like that that audience groups keep moving then people keep walking from location to location from program to program part, they have fun, they mix. You’re not getting monocultural clusters. So it’s part of crowd management that through programming you keep all those groups moving, and […] those get to mix too […] and they’re also coming into contact with things they otherwise wouldn’t have seen, they come into contact with people they otherwise wouldn’t have seen, instead of accumulating in one little area”.

Thus, even if audience groups might be spatially segregated across locations and stages, this organizer argues that movement creates the possibility for social mixing, even if only fleetingly. Some other organizers also see the connection between movement and mixing, albeit formulating it less strongly. The artistic director from Blijdorp for example argues:

“I think it’s the most fun when you go to a festival and you go for your favourite house artist but all of a sudden you get caught up in a live stage and then you’re really standing between people you normally don’t see”.

The connection made between movement and mixing also exemplifies organizers’ focus on short-term encounters. They mostly discuss social mixing as “running into” others, “people coming together” or standing in the same field as people you would not normally interact with. Still, a few argue for a slightly more active engagement, for example stating that “diversity is not only the people walking there [at the event] but also how they engage with one another, how- and that they’re really dancing with each other” [RU_F03].

Organizers use four strategies to overcome genre-specific segregation at their festival: 1) mixing by spatial design, 2) mixing by timetable design, 3) mixing by program design and 4) mixing by visual design. All these strategies are built on the premise that they help people move across the separated festival areas, mixing in between, or mix at a specific area within the festival space. As Ganji and Rishbeth (Citation2020) previously argued diversity of functions and intersecting movement is important for the mediation of conviviality within spaces, an argument supported by our findings as we will show below.

Firstly, movement can be stimulated through spatial design of the program:

“It’s our job to tempt people. […] we make sure that: okay everyone has their own thing… but to accidentally put something that’s very close to that, but that they wouldn’t go to themselves right around the corner, or that people walk across that before they go to their own thing and then for example: ‘oh yeah! This is actually pretty cool too’ we want to get people outside of their own music spectrum” [EEN_F02].

Clearly, this organizer uses his knowledge about different audience groups and their taste, to make a place-based estimation of where these groups will go and where the possibilities to mix with others and discover new music are. This closely relates to the way in which Stevens and Shin (Citation2014) describe axiality in one of their cases, where they found that circulation enhances interaction “as people encounter those walking in the opposite direction” (p. 10).

Secondly, organizers, and programmers particularly, consider their timetable design:

“you look at how people walk- because […] you want people to walk from location to location and that it’s a bit of fun […] so that’s something you work with in how you program- so the times of everything- so that you have a big artist at place A and then 10 minutes in between and a big artist at place B or some smaller things in between. But […] that you give people the opportunity to go from place to place to place” [MAG_F03].

This means that organizers not only pay attention to where specific genres, and hence audiences, will be located, but also to when these audience groups will want to go somewhere.

Thirdly, organizers try to mix genres at separate stages so that broader audience groups are attracted to specific locations, thereby consciously blocking movement and creating mixing in one area. This mainly happens at the main stage. For example, in the case of Toffler:

“We have the main […] and there we program a bit mixed. We start with house and we go to a bit of techno, but we try to keep that more general, so that everyone likes it” [TOF_F03]

Another organizer similarly argues: “I mean at Eendrachtsplein [main stage] we wouldn’t program a-ehh really heavy metal band, but we want people that pass by, ehmm that they think ‘Oh what interesting, fun, music thing is going on here?’” to “Attract them with the main stage and let them walk on to the rest of the program from there” [EEN_F02]. Besides at the main stage, organizers can choose to do this at a separate stage, or even within one act: “We don’t want to chase certain audiences away with an act, so-eh we’re trying to look for cross-overs. Uhm yeah we’re trying to get the overlap of genres across within the acts, so that it actually is something for everyone” [BAR_F01]. Here, they purposefully cross symbolic boundaries, by providing a program that mixes genres.

Lastly, regarding mixing by visual design, the organizers’ goal is that “every stage has to be that good that people want to stay there all day, but at the same time the other stages have to be so cool that you want to keep walking around” [BF_F04]. The festival director of Rotterdam Unlimited shares how this can be done through spatial arrangements:

“you make sure that there’s a good market [break] which is why people have to constantly walk to get food and drinks, you make sure there’s outdoor cafes and you make sure that if you stand at stage 1 you can already see stage 2 so that you’re challenged. and you design the place, so you want to see everything, it looks good visually and you constantly see a program you’re curious about and you make sure the food is divided in such a way that- that you ‘I have a need for that then I shouldn’t be here I should be there’ you know- so in all these ways you stimulate people to keep moving. But programming is primary”.

Other organizers also share that it is important to provide the possibility to hop from stage to stage, to create an experience and make the space visually interesting so that people will want to move around and to steer people in certain directions through signing. Attracting people through visuals and stimulating their imagination (Thwaites, Citation2001), is thus used by organizers to stimulate movement.

4.4. Designing movement to foster safety and enjoyment

The connection between movement, mixing and spatial organization is made by many but not all organizers. This might have to do with the division of tasks. Seemingly, organizers that need to have an overview of everyone’s tasks (the directors), the founders, the organizers with more experience and the organizers who have a particular role in programming or staging seem to connect movement, mixing and spatial organization more. Nevertheless, many of them also argue that they want to create audience movement for reasons of 1) enjoyment and 2) safety, which are often connected.

Creating an enjoyable space is one of the organizers’ main concerns. Partially, this is about excluding the possibility of negative experiences, for example by using overflow areas so that large groups can move around without trampling each other. They are not only concerned with this themselves but “These questions are asked by fire safety, by police, firemen etc. They ask us okay how are you going to make sure the walking lines are good, how do you make sure people can flee, you know it is, we know that ourselves, but others are also keeping us pointed to that” [MAG_F02].

Preventing negative experiences is also related to preventing negative encounters. As an organizer argues: “because in the moment that groups become static, then they’re becoming more difficult to regulate then you’re getting group formation and group formation can lead to excesses” [RU_F01]. Another organizer states that they produce separate stages “to separate the audiences, so just a safety measure” [BAR_F01]. This means that both separation of social groups as well as movement of those groups is important to create a safe environment. Another organizer recalls one edition of a festival he organized, where separation of social groups across stages and movement between stages provided the context for negative encounters to occur:

“we had a separate urban stage and a separate main dance stage, and the urban always stopped half an hour earlier than dance, urban went to dance, and then it was a fight. Those are two target audiences you want to serve with an event, but set up in this way-uhmm, they became two sides instead of what it is now, with everything mingled” [MAG_F02].

Thus, it seems that organizers feel the need to meticulously consider which social groups can and cannot be mixed within a festival space to create a safe(r) space and to keep negative encounters at bay.

Conceptualizations of safety can also be linked to how Gehl (Citation2010) defined it, meaning that safety is about creating a space that makes sense and where people can easily distinguish important places. This is important for encounters, as for these to occur people need to feel relaxed, both mentally and physically (Ganji & Rishbeth, Citation2020). This also means that organizers seem to define safety mostly as a crowd control issue. As one organizer argues: “if you walk a round- then you can pretty clearly see where everything is, so it’s sort of- it naturally became pretty clear […] Naturally every part has its own function” [MET_F05]. This similarly applies to helping people move around a festival space: “A good festival has to be produced well in terms of routing. It has to make sense, you have to be able to walk from A to B in a logical way” [BF_F02]. Mostly, organizers create these spaces by considering their own experiences with and knowledge about audience behavior.

Some organizers also discuss the production of enjoyable spaces and movement by creating places of discovery. Here, we confirm Morgan’s (Citation2007) findings, who argued that a good festival for audiences is one where one can move around, where permeability is considered (Stevens & Shin, Citation2014). As one organizer argued: “That’s a good festival for me. That you can go exploring. That you have weird corners, recesses, weird paths” [BF_F02]. Enjoyable movement is for example created in such a way so that people do not have to walk in straight lines (Gehl, Citation2010): “people say it’s a very long walk and then you question them a bit more and then you find out it’s not necessarily the distance but the mental distance because it’s just an annoying walk, two hours the same route back and forth is less fun” [BF_F03]. As another organizer corroborates, you should not be able to see the end of the terrain from the entrance because “it’s fun if there’s still things to discover” [MOD_F01].

4.5. Serendipity of creating movement

Designing social behavior is not foolproof. As the festival director of Metropolis recalls:

“we had a hip hop stage in 2018. And then we thought okay we have hip hop and that starts at 9 and then if it ends a little earlier they can mix a little bit, but that those [people] only stood there. And then we thought okay then next year we will not only do that as a hip hop stage, but then we will program them [hip hop acts] between other acts, because then you get more of a flow, but actually that’s not what happened. They only came for that act and then they left again and then they came for the act again and then they left. […] then I thought maybe it is good that we give them a place where they can be that and where they feel good and they don’t have to mix with other people and other acts where they actually don’t feel like it.”

Clearly, this organizer doubts the necessity of the norm that mixing has become and values the bonding moments within social groups that can occur at festivals. We also see that strategies of mixing by timetable and spatial design did not work. What first springs to mind is that audiences are co-creators of the festival (Morgan, Citation2007) and that they may not have been interested in other parts of Metropolis, which traditionally is a more rock and indie festival. The way in which the programmer of Metropolis describes his rationale behind programming, might make us think about it in this way:

“There are festivals and programmers who work differently like yeah, there has to be something for everyone. […] and then I think, no, at some point we chose to build a strong profile, a strong story, a strong identity of the program”.

This means that the program has to fit a certain musical framework, which is similarly argued for by the programmer of Boothstock, a progressive electronic music festival:

“You have a Drum ‘n Bass stage, a bit further you have Latin-house, if you walked more to the right you had a techno-uh thing, you walked a bit more you had house, so […] those labels got the freedom to showcase their own musical thing. But within a […] framework - you have to be able to walk from stage to stage and still have fun so it is not that you would put hardrock next to house […] the quadruple time is the basis”.

Thus, even though programming might be the way to get diverse groups of people within a festival space, the different genres still have to fit a certain framework for people to start moving around.

5. Concluding discussion

This article addressed how music festival organizers may design spaces of encounter at festivals. Based on semi-structured interviews, we found that organizers clearly distinguish audience groups along symbolic and social boundaries, being highly aware of the “typical” groups varying music genres attract. These distinctions organizers make, are spatially represented in “stages as islands,” as organizers produce their separate stages and locations with distinct music genres and related audiences in mind. Using spatial boundaries, organizers try to separate audience groups by enclosing separate stages through barriers, thresholds, nets and sound. Consequently, they create a smaller, more intimate space, where people feel comfortable and can connect with others in their immediate surroundings (Stevens & Shin, Citation2014). This means that the boundaries organizers perceive between social groups, mainly based on age/generation, race-ethnicity and social class in relation to varying music genres, are “enclosed” in separate stages and locations within the festival space, possibly creating within-space segregation while simultaneously stimulating bonding moments at festivals.

If this is where organizers’ considerations regarding encounters within festivals would stop, festivals could be considered to inherently stimulate segregation with different social groups belonging to different parts of the festival space. However, organizers consider four strategies to prevent genre-specific segregation within music festivals: 1) mixing by spatial design, 2) mixing by timetable design, 3) mixing by program design and 4) mixing by visual design. These strategies are based on the premise that intersecting movement is important for conviviality to occur (Ganji & Rishbeth, Citation2020). Our findings show that organizers try to stimulate people to move around the festival space so that audiences get to meet, see and engage with other audience groups not present at “their” stage, thereby engaging in more fleeting contact typical to conviviality. Where Stevens and Shin (Citation2014, p. 16) argue that the flows of people during festivals are relatively free, we show how this kind of “free” movement may be consciously designed by festival organizers through programming and spatial design.

First, by switching programming at different stages, people will have to move around to be able to see what they like and thereby cross “the other.” Secondly, by allowing for time between different program parts people get the opportunity to move around. Thirdly, through the connection and mixing of genres at one stage, organizers try to create a more accessible space for different people to meet, by purposefully crossing the symbolic boundaries within that area. Fourthly, spatial design plays an important role in the separation and mingling of people. Movement across spaces is created through visual design and signage, creating a space that allows for discovery and where you need to walk around to get food or see parts of the program. Agreeing with Morgan (Citation2007) and Stevens and Shin (Citation2014) we find that organizers try to provide a space where positive experiences can happen, as movement is often also facilitated for purposes of safety and enjoyment.

This article makes two key contributions to leisure studies. First, it provides a new perspective on social mixing in public spaces. Even though there has been much interest in this topic in the field of leisure studies and beyond for many years (Peters, Citation2010; Wilks, Citation2011), studies tend to neglect the importance of the design of spaces for encounters (Ganji & Rishbeth, Citation2020). Nevertheless, as we show, confirming earlier research (Gehl, Citation2010; Thwaites, Citation2001), design is important in how people, move, meet and experience a place. Secondly, we provide a more thorough understanding of the way in which festival producers perceive space and the effect the conscious production of space might have on consumer experiences by showing how taste can have spatial representations. We show that boundaries do not have to be fixed: the same design strategies that create boundaries can also build bridges. This is particularly important since the organizers’ perspective has been understudied (Dashper & Finkel, Citation2020). Moreover, following earlier research and our findings, their strategies may be significantly affecting where, when, and how encounters take place (Walters et al., Citation2021).

While our article has deepened our understanding of how spaces of encounter can be produced, we would like to set a future research agenda. The cancelation of events during COVID-19 limited our research but allowed us to thoroughly explore the production perspective on festivals. Considering festival and leisure studies, it is important to further investigate how the design strategies organizers employ work in practice, as we saw that these sometimes do not work, and how audiences are affected by them. Future research should investigate how people move within a festival space, where they do or do not go and where they feel like they belong. Moreover, research is needed to see the extent to which our findings apply to other urban contexts and leisure spaces that are less temporal in nature. How can symbolic and social boundaries be observed in the more permanent structures, of for example restaurants, parks, or concert venues and how could urban design strategies contribute to social mixing taking place there?

Festivals organizers make connections between symbolic, social and spatial boundaries and use their cultural and spatial knowledge to design festival spaces. While, on the one hand this knowledge seems to reproduce symbolic and social boundaries, segregating social groups within a festival space, at the same time this knowledge can be used to bridge the same boundaries. This means that the, at first sight maybe puzzling, paradox that music festivals are spaces of bonding and bridging (Mair & Duffy, Citation2017) can be understood by combining theoretical insights from cultural sociology and urban planning and design. Festivals are produced in a way that can create bonding with ingroups and affiliation with “others” at the same time, because of the way in which organizers have begun to understand and design them. Importantly, while audiences can be said to be co-creators of that experience (Morgan, Citation2007), we should not forget that organizers consciously design spaces where bridging and bonding can happen.

Acknowledgments

We would like to acknowledge members of the HERA-funded project Festiversities team and members of Rotterdam Popular Music Studies for productive conversations and feedback on first drafts. We would also like to thank the reviewers for insightful feedback on earlier versions of this article. Lastly, we would like to thank Jessica Warren for proofreading the manuscript.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Anderson, E. (2004). The cosmopolitan canopy. The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 595(1), 14–31. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0002716204266833

- Bennet, A., & Woodward, I. (2014). Festival spaces, identity, experience and belonging. In A. Bennet, J. Taylor, & I. Woodward (Eds.), The festivalization of culture (pp. 25–40). Ashgate Publishing Limited.

- Berkers, P., & Michael, J. (2017). Just what is it that makes today’s music festivals so appealing?. In: Koudstaal, P. (Eds.), Music brings us together: Music & art festivals (pp. 98–115). Uitgeverij Komma.

- Berkers, P., van Eijck, K., Zoutman, R., Gillis-Burleson, W., & Chin-A-Fat, D. (2018). De cultuursector is als een alp, hoe hoger je komt hoe witter het wordt. Boekman, 115, 20–24.

- Blijdorp Festival. (2019, July). Final info: Blijdorp festival 2019. Retrieved October 16, 2020, from https://www.blijdorpfestival.nl/news/final-info-blijdorp-festival-2019/

- Cudny, W. (2016). The concept, origins and types of festivals. In W. Cudny (Ed.), Festivalisation of urban spaces (pp. 11–42). Springer.

- Dashper, K., & Finkel, R. (2020). Accessibility, diversity and inclusion in the UK meetings industry. Journal of Convention & Event Tourism, 21(4), 283–307. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/15470148.2020.1814472

- Fincher, R., & Iveson, K. (2008). Planning and diversity in the city: Redistribution, recognition and encounter. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Ganji, F., & Rishbeth, C. (2020). Conviviality by design: the socio-spatial qualities of spaces of intercultural urban encounters. Urban Design International, 25(3), 215–234. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1057/s41289-020-00128-4

- Gehl, J. (2010). Cities for people. Island Press.

- Gerring, J. (2008). Case selection for case‐study analysis: qualitative and quantitative techniques. In J.M. Box-Steffensmeier H.E. Brady & D. Collier (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of political methodology (pp 645-684). Oxford University Press.

- Laing, J., & Mair, J. (2015). Music festivals and social inclusion: The festival organizers’ perspective. Leisure Sciences, 37(3), 252–268. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/01490400.2014.991009

- Lamond, I. R., & Platt, L. (2016). Introduction. In I.R. Lamond & L. Platt (Eds.), Critical event studies: Approaches to research (pp 1–14). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Lamont, M., & Molnár, V. (2002). The study of boundaries in the social sciences. Annual Review of Sociology, 28(1), 167–195. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.soc.28.110601.141107

- Leal, J. (2016). Festivals, group making, remaking and unmaking. Ethnos, 81(4), 584–599. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/00141844.2014.989870

- Lees, L. (2008). Gentrification and social mixing: Towards and inclusive urban renaissance? Urban Studies, 45(12), 2449–2470. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098008097099

- Mair, J., & Duffy, M. (2017). Festival encounters: Theoretical perspectives on festival events. Routledge.

- Morgan, M. (2007). Festival spaces and the visitor experience. In M. Casado-Diaz, S. Everett & J. Wilson (Eds.), Social and cultural change: Making space(s) for leisure and tourism (pp 113–130). Leisure Studies Association.

- Paleo, I. O., & Wijnberg, N. M. (2006). Classification of popular music festivals: A typology of festivals and an inquiry into their role in the construction of music genres. International Journal of Arts Management, 8(2), 50–61.

- Peters, K. (2010). Being together in urban parks: Connecting public space, leisure, and diversity. Leisure Sciences, 32(5), 418–433. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/01490400.2010.510987

- Phillips, D. (2014). Segregation, mixing and encounter. In S. Vertovec (Ed.), Routledge international handbook of diversity studies (pp. 255–362). Routledge.

- Rishbeth, C., Blachnicka-Ciacek, D., & Darling, J. (2019). Participation and wellbeing in urban greenspace: ‘Curating sociability’ for refugees and asylum seekers. Geoforum, 106, 125–134. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2019.07.014

- Roy, W. (2004). “Race records” and “hilbilly music”: Institutional origins of racial categories in the American commercial recording industry. Poetics, 32(3-4), 265–279. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.poetic.2004.06.001

- Savage, M., Devine, F., Cunningham, N., Friedman, S., Laurison, D., Miles, A., Snee, H., & Taylor, M. (2015). On social class, anno 2014. Sociology, 49(6), 1011–1030. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0038038514536635

- Schaap, J., & Berkers, P. (2019). “Maybe it’s… skin colour?” How race-ethnicity and gender function in consumers’ formation of classification styles of cultural content. Consumption Markets & Culture, 23(6), 599–615. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/10253866.2019.1650741

- Scholten, P., Crul, M., & van de Laar, P. (2019). Coming to terms with superdiversity: The case of Rotterdam. Springer Nature.

- Sharpe, E. (2008). Festivals and social change: Intersections of pleasure and politics at a community music festival. Leisure Sciences, 30(3), 217–235. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/01490400802017324

- Stevens, Q., & Shin, H. (2014). Urban festivals and local social space. Planning Practice & Research, 29(1), 1–20. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/02687459.2012.699923

- Swartjes, B., & Berkers, P. (2022). How music festival organizers in Rotterdam deal with diversity. In Smith, A., Osborn, G., & Vodicka, G. (Eds.), Festivals and the city: the festivalisation of urban places and spaces. University of Westminster Press.

- Thwaites, K. (2001). Experiential landscape place: An exploration of space and experience in neighbourhood landscape architecture. Landscape Research, 26(3), 245–255. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/01426390120068927

- Uitermark, J., Duyvendak, J. W., & Kleinhans, R. (2007). Gentrification as a governmental strategy: Social control and social cohesion in Hoogvliet, Rotterdam. Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space, 39(1), 125–141. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1068/a39142

- Valentine, G. (2008). Living with difference: Reflections on geographies of encounter. Progress in Human Geography, 32(3), 323–337. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0309133308089372

- Van Beckhoven, E., & van Kempen, R. (2003). Social effects of urban restructuring: A case study in Amsterdam and Utrecht, the Netherlands. Housing Studies, 18(6), 853–875. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/0267303032000135474

- Van der Hoeven, A. (2016). Het levend erfgoed van Rotterdam. Puntkomma, 10, 20–22.

- Walters, T., Stadler, R., & Jepson, A. S. (2021). Positive power: events as temporary sites of power which “empower” marginalized groups. International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management, 33(7), 2391–2409. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCHM-08-2020-0935

- Wilks, L. (2011). Bridging and bonding: Social capital at music festivals. Journal of Policy Research in Tourism, Leisure and Events, 3(3), 281–297. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/19407963.2011.576870

- Wilson, H. F. (2017). On geography and encounter: Bodies, borders, and difference. Progress in Human Geography, 41(4), 451–471. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0309132516645958

- Woodward, I., Haynes, J., & Mogilnicka, M. (2022). Refiguring pathologised festival spaces. Governance, risk and creativity. In Woodward, I., Haynes, J., Berkers, P., Dillane, A., & Golemo, K. (Eds.), Remaking culture and music spaces. Affects, infrastructures, audiences. Routledge.