PRELUDE

Violence. Dead crabs by the many thousands on the beach. Dead fish too. Ponds full of tires. Bubbles surfacing from broken gas pipes somewhere at the bottom of the river. The wind sweeping through the wreckage of an abandoned steelworks providing an incessant hum that echoes across this coastal ‘wasteland’ of the Anthropocene. Someone fishing sits huddled on a concrete jetty. A surfer, shivering, hurriedly pulls and tugs on a neoprene wetsuit as they dance on the snow. His mates wait for him. A beachcomber hunts for washed up mining tools to turn into art. Relationships with nature—this post-industrial ‘wasteland’ is nature too—in this place may make you feel better. They may not, also. This is polluted leisure in the Anthropocene.

Introduction

Clifton Evers (Citation2019a, Citation2019b) explains that polluted leisure references the embodied, sensorial, emotional, intellectual, spatial, and technological occurrences of pollution as it mingles with leisure. Scholars are increasingly interested in examining the daily relationships people have with pollution—cultural, social, embodied—that go beyond epidemiological accounts of ill-health (Alaimo, Citation2016; Davies, 2018; Lora-Wainwright, Citation2021). My particular interest lies in everyday and even mundane leisure/recreational relationships with pollution. In this article I provide evidence for and analyze how ‘place attachment’ (Lewicka, Citation2011) as the embodied relationship between place and subject, influences how some men who live in a post-industrial region experience their striving for well-being through polluted leisure. The study site is the coastal conurbation of Teesside in north-east England.Footnote1 For 200 years the region has been home to heavy industries such as steel, manufacturing, nuclear, chemical production, and shipbuilding. Over the last 40 years the region has undergone widespread deindustrialization and disinvestment. There is a widespread legacy pollution and continuing pollution: affecting water, soil, and air. Legacy pollution refers to the long-term environmental contamination that persists even after the cessation of the original source of pollution. It refers to pollution that was generated in the past but continues to impact the environment and human health in the present and potentially for future generations. Legacy pollution can stem from various sources, including industrial activities, improper waste disposal, historical agricultural practices, and past mining activities. Residents have been pejoratively called ‘smoggies’ by others in the region but have reclaimed the label to signify pride in their identity, community, place, and industrial heritage.

Parts of Teesside are ‘toxic geographies’. By ‘toxic geographies’ I mean ‘lived environments, where people encounter hazards in their day-to-day lives, in mundane and incremental ways’ (Davies, Citation2022, p. 409). Toxic geographies can arrive spectacularly, through oil spills, sewage overflows after heavy rain, or dredging that stirs up toxins embedded in riverbeds. Toxic geographies are also the result of what Robert Nixon (Citation2011) calls ‘slow violence’. He explains this ‘as a violence that occurs gradually and out of sight, a violence of delayed destruction that is dispersed across time and space, an attritional violence that is typically not viewed as violence at all’ (p. 2).

This article begins with a look at how gender and the Anthropocene are intertwined, followed by an overview of how men from the Global North are generally situated regarding the current socio-environmental situation. I then introduce how scholars explain connections between men and leisure, and set up the associations between outdoor recreation, well-being, and blue spaces (e.g. waterways and surrounding areas, seas, rivers, lakes, etc.). To further situate the contribution of this study toward thinking about relationships between pollution and leisure, I present a selection of studies and conceptualize the concept place attachment, that I argue is useful to understand daily relationships people have with pollution during their leisure. Next, I explain the ‘arts-based research’ (ABS) process (Leavy, Citation2017; Castro et al., Citation2023) and arts-informed ethnography (including autoethnography) used to conduct the study. These methods affectively integrate creativity, and self-reflexivity into the research context. The ethnography included informal interviews, leisure activity ‘go-alongs’, photo-voice, collaging, and textile banner making. Teesside is then introduced as the setting, accompanied by a presentation and analysis of men and polluted leisure that explores the connection between place attachment, pollution, and well-being.

A provocation called the Anthropocene in blue spaces

We are now living in a geological epoch called the Anthropocene (Crutzen & Stoermer, Citation2000). This period is marked by human activities, technologies, and alterations to the global stage that have a greater impact on ecologies than ever before. As we stand on the precipice of change and adaptation, ‘science, governance, technology and citizens’ (Spannring & Hawke, Citation2022, p. 4) must converge productively, creatively, and inclusively toward sustainable futures that are realizable. This article is written in the United Kingdom, one of the Global North societies that has benefited from the export of capitalism and the associated damage of pollution and extraction (Hawke, Citation2022; Román & Molinero-Gerbeau, Citation2023; Sultana, Citation2022). However, it is important to note that pollution and extraction occurs in this heartland of capitalism and colonialists too. The damage caused by these systems is not restricted to ‘over there’ but is experienced daily by low-income and marginalized populations in England.

The experiences of ecological collapse and everyday living is unevenly distributed among demographics, and consequently takes different forms due to socio-cultural processes of gender, class, ethnicity, religion, sexuality, disability, caste, age, nationality, and location (Sultana, Citation2022; Taylor, Citation2014). Feminist environmental organizations (e.g. Women’s Environment & Development Organization), the United Nations, and researchers have identified connections between environmental crises, climate justice, vulnerability, activism, adaptation, youth and gender (MacGregor, Citation2017; Spannring & Hawke, Citation2022; UN Women, 2022). While all gendered identities are implicated, and women and gender non-conforming people (particularly those from the Global South) face the brunt of the effects of the environmental crises, there is still a need for critical studies about how men in the Global North understand and embody and communicate their everyday lives (Hultman & Pulé, Citation2018; MacGregor & Seymour, Citation2017).

The current epoch has also been labeled the ‘m(A)nthropocene’ to draw attention to a masculine dualist logic of domination perpetuating environmental and social harms (Di Chiro, Citation2017; Plumwood, Citation1993). Men in the Global North are associated with domination and damage to the environment. Those men are over-represented when it comes to carbon emissions and damaging ecological footprints, climate denialism, lower perceived risk of relying wholly on geoengineering ‘solutions’ to address environmental crises, and relationships—intellectually and emotionally; conceptually and physically—with fossil fuels (Alaimo, Citation2016; Brough et al., Citation2016; Daggett, Citation2018; Hultman & Pulé, Citation2018; MacGregor & Seymour, Citation2017; Sikka, Citation2019; Twine, Citation2021). There are men working to better their relationships with the environment through environmental management, sustainable agriculture, and renewable energy initiatives. However, many of those men continue to try to master nature; understanding themselves as apart from nature rather than as a part of nature (MacGregor & Seymour, Citation2017; Paulsen et al., Citation2022; Plumwood, Citation1993; Sikka, Citation2019). Cultural, social, and embodied perspectives about men’s relationships with pollution remain vague in leisure studies.

Leisure is a way for men to express their identity and secure their sense of belonging (Blackshaw, Citation2003). Men build knowledge about the world and perform masculine identities through leisure, including in relation to age, race, sexuality, and other genders (for example, see Evers, Citation2019a; Haywood, Citation2022; Johnson & Cousineau, Citation2018; Liechty & Genoe, Citation2013; Pringle et al., Citation2011). The leisure experiences of men in relation to pollution and environmental challenges more broadly have been neglected, even though during leisure men have contact with toxins, plastics, bacteria, sewage, and radiation. The intimate relationship people have with catastrophic environments, including pollution—material and cultural—produces adaptations that include new leisure practices, new leisure activities, new leisure places, as well as new leisure-ecology sensibilities (Cherrington & Black, Citation2023). The adaptations complicate human-nonhuman separations, interactions, and outcomes commonly expected during outdoor leisure e.g. well-being, therapeutic benefits, or environmental activism (Cherrington & Black, Citation2023; Evers, Citation2019a, Citation2019b, Evers & Phoenix, Citation2022; O’Connor et al., Citation2022; Olive, Citation2022).

While this article is not solely focused on masculinities, it does attend to how men live with pollution during their leisure-time. Hence, I refer to masculinities throughout the article. When referring to masculinities I do so through a framework that understands them as institutionalized and organized within and across societies in ways that produce a multiplicity of masculinities and internal complexity, whilst also accommodating the necessary in-situ modifications and creativity expressed during contingent social, cultural, and material events (Connell, Citation1995; Gorman-Murray & Hopkins, Citation2014; Green & Evers, Citation2020; Watson, Citation2015).

The north-east of England’s industrial history and associated predominance of manual labor has shaped masculinities at the study site. This industrialization and the attendant masculinities have contributed to UK colonization and subjugation of many people alongside extensive environmental damage that today culminates as ecological catastrophe. The story of the relationship between British masculinities, industrialization, and the ecological catastrophe needs to be unpacked, however it is not an undertaking possible in this article which is focused on experiences of some men at one site in the UK. Because of de-industrialization there has been a displacement of masculinities away from production (the colliery, shipyard, or factory) at this site to consumption activities such as football, drinking, and going out (Nayak, Citation2006). However, embodied rituals of stoicism, strength, being the breadwinner, resilience, aggression, and masculine interpretations of respect stubbornly remain consistent not only at this site but throughout the UK (Nayak, Citation2006; McDowell & Bonner-Thompson, Citation2020). These rituals mixed with the deindustrialization and disinvestment have resulted in marginalization, poor health and well-being, and the region that includes the study site having England’s highest male suicide rate (Atherton, Citation2019; McDowell & Bonner-Thompson, Citation2020). To survive difficult circumstances some men in the region strive for well-being through outdoor leisure in toxic geographies (Evers, Citation2019a).

Leisure may be beneficial or restrictive for well-being (Carruthers & Hood, Citation2004; Mansfield et al., Citation2020). The model of well-being I work with frames it as multifaceted and relational, where an individual’s capacities to interact with the world can be both improved or decreased due to biological, emotional, economic, psychological, sociological, cultural, spiritual, and environmental assemblages (Atkinson, Citation2013). To refine my focus further, I am working specifically with relationships between leisure and subjective well-being, which is the subjective evaluation of whether a person’s capacities are enriched or not (Mackenzie & Hodge, Citation2020).

There are different natures with which people strive for well-being during outdoor leisure. They are all contaminated by pollution. The contaminated nature for this study is a post-industrial blue space. Blue spaces can function as ‘therapeutic landscapes’ (Bell et al., Citation2015; Olive & Wheaton, Citation2021). There is convincing evidence that blue space leisure activities—for example, swimming, surfing, artisanal fishing, beachcombing, coastal walking—are positively correlated with well-being, as well as healthy and pro-environmental sensibilities (Britton et al., Citation2020; Denton & Aranda, Citation2020; Foley et al., Citation2019; Gascon et al., Citation2017; Olive & Wheaton, Citation2021; Wheaton et al., Citation2020). However, it is worth bearing in mind that such correlations are variously informed and enacted depending on factors such as accessibility, skill, cultural exclusion, risk, and pollution (Bell et al., Citation2015; Foley et al., Citation2019; Olive, Citation2022; Pitt, Citation2018; Evers, Citation2019a, Evers, Citation2019b; Evers & Phoenix, Citation2022).

Pollution is now always entangled with leisure, in blue spaces or otherwise. There is no escaping it. It is an outcome of leisure activity, and can be a moderator of participation e.g. lowering participation to negatively affect well-being (An & Xiang, Citation2015; Chang et al., Citation2019; Huang et al., Citation2023; Yang, Citation2020). Pollution alters and produces new sensory experiences of outdoor leisure, for example, when air pollution and asthma combine to produce challenging experiences of urban running (Zajchowski & Rose, Citation2020). How to regulate and reduce waste/pollution to achieve sustainability through leisure and reckon with the waste of leisure is an urgent task (Mair, Citation2022; Tirone & Halpenny, Citation2019).

As we learn to live with it, pollution will continue to remind us, if we listen, that we are not in control at all. Through theories like ‘more-than-human’, ‘vital materialism’, and ‘new materialism’, scholars are exploring how outdoor leisure is an outcome of a coextensive world and affective relationship with the non-human (Cherrington & Black, Citation2023; O’Connor et al., Citation2022; Olive, Citation2022; Stinson & Grimwood, Citation2022; Thorpe et al., Citation2020). The non-human, including pollution, co-constitute leisure activities and places of leisure (Evers, Citation2019a, Citation2019b; O’Connor et al., Citation2022).

I understand place as more than a physical location with geographical coordinates and features. Place is also a way of perceiving and comprehending the world and giving meaning to people’s lives. It is personal and subjective, as well as social, cultural, and material. As Doreen Massey (Citation1994) explains, place is relational. It is constantly being created. Attachment realized through place-making relationships—human and non-human—is what creates a meaningful location. Pollution is part of the relationships of places and concomitant attachments.

Place attachment involves durable and intimate emotional, cultural, social, and physical bonds between a person and locations (Manzo & Devine-Wright, Citation2011). Lauren Berlant (Citation2011) explains that attachments enable people to make locations meaningful and livable even in difficult circumstances. Because of attachments people may remain committed to locations with attendant circumstances and promises that do not work for them. We might find ourselves attached to things, circumstances, and promises that are harmful, or both sustain and harm us, thereby blurring any line between flourishing and damaging. This coupling of place and attachment, as I argue, provides an additional consideration when exploring how some men live with pollution as they strive for well-being with a post-industrial contaminated blue space. I will discuss this argument in a moment. Before that I want to explain where the study is happening and how I am going about it.

Teesside

Map: Wikipedia (retrieved from https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tees_Valley)

The industrialized River Tees flows through the Tees Valley Combined Authority (TVCA). It is the combined authority for the Tees Valley urban area in England consisting of the following five unitary authorities: Darlington, Hartlepool, Middlesbrough, Redcar and Cleveland and Stockton-on-Tees, covering a population of approximately 700,000 people. The riverbed and seabed are heavily contaminated with 200-years of industrial waste, including a cocktail of toxic metals, plastics, manufactured chemicals, petroleum, urban and industrial wastes, pesticides, fertilizers, agricultural runoff, and sewage. At the mouth of the River Tees—the main study site—is South Gare. This two-mile long promontory was constructed between January 1861 to 1884, using 5 million tonnes of solid blast furnace slag—a by-product of the steel industry—and 18,000 tons of cement with back-filling being around 70,000 tons of material dredged from the riverbed.

To get to South Gare, you will drive past a variety of small businesses such as car repair garages and waste facilities. When arriving at South Gare, the atmosphere can be quite surreal. It is a combination of industry, nature, and leisure. You will encounter working and derelict industrial sites, noise, pollution, and sometimes unpleasant smells. The historical remains of World War Two are also visible, such as bunkers and pillboxes. An old shipwreck rots on Bran sands, a part of the river foreshore. In Paddy’s Hole, you can spot fishing boats, some functional and others in disrepair. Fishermen spend time in a cluster of green huts that belong to the South Gare Fisherman’s Association. Further out in the sea, you can see a wind farm that symbolizes a greener future. Perched at the north end of a breakwater is a lighthouse, built in 1884. At South Gare you will also encounter the sea, sand, flowers, and marram grasses as well as foxes, seals, birds, and the occasional deer that persist in this two-hectare ‘wasteland’. Those non-human encounters can inspire a sense of freedom, hope, pride, and a sense of well-being. For some residents the steelworks, towers, and gas-powered flames contrasted against a pink and orange sunset do too. The South Tees Development Corporation is now in the process of developing a section of South Gare as a part of a Freeport endeavor backed by the UK Government. Freeports are zones that have reduced or no tax to stimulate commerce. While some citizens celebrate the potential for work, others are concerned about the potential ramifications this initiative may have on their relationships with South Gare. .

Methodology

Since 2016 I have been doing an ethnography in Teesside, as well as surrounding areas. The participants in the ethnographic studies are from the White British group. 98.6% of citizens from the borough of Redcar-Cleveland, which borders South Gare, identify as White British which makes (Office for National Statistics, Citation2021). The age range of the men is 19 to 71 years old, and most are working-class. I am also a white man and come from a working-class and British background, although I am an immigrant from Australia. My background meant we shared some meaning systems and helped with access to participants, although I am an outsider in some ways so had to ask participants to explain and expand some local contexts and nuances (Dwyer & Buckle, Citation2009). Some of the men are retired and/or do not have a paid job, while others are employed in a variety of occupations, such as fishing, industrial agriculture, construction, as well as taxi and delivery driving. Participants previously worked at, and some continue to do so for Wilton, Billingham, and Seal Sands chemical sites. These sites make products such as petrochemicals, commodity chemicals, pharmaceuticals, fertilizers, and polymers. Additionally, some men have been and are employed at Teesside oil terminal, Hartlepool Nuclear Power Station, North Sea oil rigs, PD Ports, and British Steel’s Teesside Beam Mill.

While there is industry, much of it has been scaled back, and nearly all the wealth is extracted from the region. The north-east of England is behind the rest of the country in terms of employment, wealth, health, and wellbeing. There are a few affluent pockets in the region, but most people face an economically challenging life. Tees Valley is the second most deprived Local Enterprise Partnership in England and is classified as a ‘left-behind area’ due to its lack of community and civic infrastructure, relative isolation, and low levels of participation (Tees Valley Combined Authority, Citation2021). The Tees Valley employment rate has seen some improvement over the last five years, but unemployment remains above the England average (Ibid). Tees Valley residents have lower qualifications than those of many other parts of the country, which suppresses wages (Ibid). The north-east of England has seen the sharpest increase in child poverty across the UK and currently has the highest rate in the country (Loughborough University, 19 May Citation2021). Health and well-being indicators across the Tees Valley are worse than the England average, including personal measures of life satisfaction that inform any feeling that the things done in life are worthwhile as well happiness and anxiety. The north-east of England also has the highest rate of male suicides in England (Office for National Statistics, Citation2021).

To find participants I use leisure activity social media pages, put up posters at equipment-related stores, as well as undertake snowball sampling via existing relationships I have with gatekeepers. I use mixed methods to achieve ‘a more comprehensive and a more robust perspective by combining the vantage points that different methods afford’ (Crossley & Edwards, Citation2016, p. 3). Multiple methods produce different data. I can then analyze the differences (e.g. tensions, similarities, contradictions, paradoxes) and compare realizations to arrive at more robust, nuanced, and to be honest, interesting, and challenging stories about living with pollution.

The ethnography has involved 48 in-situ primary informal interviews to-date. Part of this practice includes auto-ethnography. By this I mean that the studier is also the studied subject. The participants have told me they prefer the casual conversations and outdoor setting of these informal interviews because this helps them to feel more comfortable and their ideas can be inspired by the more-than-human relationships that make the leisure activities and location of the study meaningful for them. The informal interviews happen while we are engaged in outdoor activities together, such as walking, fishing, surfing, and swimming. By engaging in the places and leisure practices of participants I am gifted access to nuanced understandings of cultural practices and values as well as opportunities to build relationships that provide not only access to the field and participants but also moments to co-produce interpretations of data (Carpiano, Citation2009; Moles, Citation2008; Denton et al., 2021; Evers, Citation2018; Stoodley & lisahunter, 2020). The participants choose the routes, activities, and sites for these leisure research go-alongs. I keep fieldnotes and all interviews are recorded—using GoPro cameras, hydrophones, recorders—with the participants’ permission and transcribed in full (Evers, Citation2016).

I also use Arts Based Research (ABR) methods with participants to co-produce data. ABR is a transdisciplinary approach that integrates the creative arts into research contexts (Leavy, Citation2017). My intention when using ABR is to work collaboratively on meaning-making and enable opportunities that prompt reflection about changes to normalized sensibilities and challenge assumptions, which artmaking can assist in doing (Riddett-Moore & Siegesmund, Citation2012). Data are constructed during an ever-evolving research activity rather than found ‘out there’ (Ibid). That process of meaning-making tends to provide opportunities to explore the re-presenting of meaning (Hall, Citation1997). The ABR also helps the participants and I document and explore the contribution of the more-than-human—sensory and non-human—relationships of place attachment and related polluted leisure (Hickey-Moody, Citation2020). As one participant explains

I’m less interested in the human story. When I’m making art, I’m more interested in what the objects and place are saying. I try to absorb and share their story … like how the chemicals from the chemical factory stain the sand

My early research findings suggest that ABR helps participants express what they cannot in words alone. The photo-voice visual research method is popular among the participants. Photo-voice is a method through which participants use photography to document, reflect on, and communicate experiences and topics that are important to them (Liebenberg, Citation2018).

Example photo voice image from fieldwork (used with permission of participant).

During and after the ‘go-alongs’ I sit down with the participants and discuss the photographs as well as the experience of taking the photographs e.g. choices made about composition. These are in-situ stimulated recall and co-analysis moments that I record.

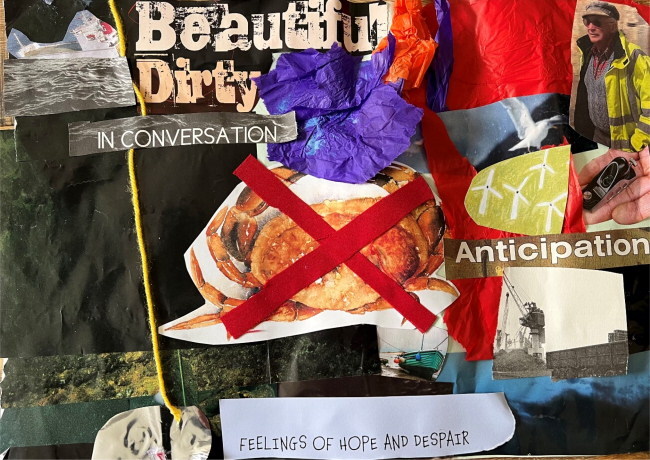

The ABR also includes collaging and textile banner-making. Collage is a productive way for research participants to re-present multisensory experiences of place (Gerstenblatt, Citation2013). It is not only visual. The act of re-arranging calls forth hearing, touching, and other senses the participants want to communicate. Collage as a research method can manifest in various forms. It can be focused on asking participants to reflexively construct narrative about their lives and places, as well as ‘cut up’ the dominant stories about place and their identity resulting in sensitivity to and consideration of alternative interpretations and multiple realities (De Rijke, Citation2023). By employing collage, researchers can incorporate perspectives beyond the human realm thereby decentering the human, as collage-makers respond to and try to map the many fragments, relationships, and agencies that shape their worlds as they intra-act with the materials in the process of making (Ibid). During this project, the process of collage-making was directed toward reflexive narrative, ‘cutting up’, and exploring more-than-human relationships. We spoke about contradictions, disturbances, what comes to be considered normal, what mattered and did not for each other, alternative arrangements, and what surprised us. The collage meaning-making was an iterative process that worked to defamiliarize and refamiliarize relationships, objects, and place aspects of the men’s lives.

The textile banner making involves collaging with textile to make banners. It is a creative process requested by the participants. Banner making has a rich tradition in north-east working-class industrial communities, especially mining. Women and men made banners representing their identity and community values and to this day parade them at, for example, mining galas. Some men preferred to draw on this tradition to explore and re-present their identity and living with pollution. During the art-making process, participants discuss each other’s work and I guide them to also discuss relationships between pollution, leisure, and place. I record and transcribe the dialogue.

I use reflexive thematic analysis to analyze all the transcripts as well as the art. This technique involves a recursive and inductive processing of research aims/questions, field, data, coding, theory, and researcher experiences (Braun & Clarke, Citation2021). As mentioned, sometimes I collaborate with participants to co-analyze in-situ. This collaboration multiplies realizations (‘aha moments’) and there is a lot of ‘checking in’ about accuracy of interpretations. During analysis I also consult sources such as popular media (online, print, radio), scholarly studies, and my fieldwork documentation (sound, fieldnotes, photographs, video recordings). I like to think that I am braiding the methods so they work together to provide lessons that are sensitive to the multiplicity of knowledge(s) and world(s) (Watson, Citation2020).

This braiding method has produced multiple stories and lessons about how place attachment influences how pollution, leisure, and well-being combine for some men in a toxic geography. So, I’ll now turn to those stories and lessons.

Place attachment pollution, leisure, and well-being in a contaminated blue space

The men regard the natural environment of the blue space as a significant part of their leisure identity and experience. The art and interviews commonly referenced and celebrated the sand, sea, river, wind, seals, marram grass, dolphins, fish, and foxes, as well as feral animals such as cats and rats. Birds were particularly popular among the men. We would spend many hours watching, listening, and documenting as they flew over the sea and oil rigs as well as nested in the sand dunes and industrial ruins. Their names are known

Bridled Tern, Thrush Nightingale,

White–throated Robin, Hooded Merganser, Glaucous–winged Gull, Citrine Wagtail, Bluethroat, Wilsons Phalarope,

White–rumped Sandpiper, Broad–billed Sandpiper,

Red–necked Phalarope, Garganey, Whiskered Tern, Pied Wheatear, Yellow–browed Warbler, Greenish

Warbler, Barred Warbler,

Black Redstart, Bluethroat, Woodchat Shrike,

Shearwaters, Gannets, Gulls, Skuas,

Auks, Waders, Terns.

The participants commonly referenced a clear relationship between the animal encounters and their well-being sensibilities, confirming the many studies that evidence the correlation (Bell et al., Citation2018). Two participants explicitly brought together place, attachment, and the birds when discussing their photographs.

The come and go. Lots of them are migratory. They keep coming back. Like me. The noise of the remaining industry disturbs some of them, I reckon. Sometimes you won’t see some species for a few years. I’ve left to find work and then felt the need to come back. I’ll sit at that old jetty, even if it’s a bit slimy. You get a good view there. The birds stick around maybe meaning there’s still something good for them here. Or it’s habit … New industries will come. They [local and national government] promise a green industrial revolution. Do you know anything about that?

We’ve got to go green. I go litter picking here after work. Some of the birds get trapped in the rubbish he’s told you about. I’ll do my bit to fix the place. It’ll help the birds and that makes me feel a bit better.

I am struck by the optimism in government initiatives and a green future despite the legacy pollution, industrial ruination, and to-date many failed promises by politicians heralding the arrival of tens of thousands of green industries. What does exist, is, further construction on the river foreshore and increased dredging of the river to extend the port.

Promises are a form of attachment to place. They contribute to what Berlant (Citation2011) calls cruel optimism. This term refers to an attachment to a desire, object, or place that can harm you or others while at the same time holding out the promise of something better, a flourishing. A person or people may remain attached to promises even though they are amid harmful circumstances and what is desired is unlikely to be attained. Berlant (Citation2011) writes

optimism is cruel when the object/scene that ignites a sense of possibility actually makes it impossible to attain the expansive transformation for which a person or a people risks striving; and, doubly, it is cruel insofar as the very pleasures of being inside a relation have become sustaining regardless of the content of the relation, such that a person or a world finds itself bound to a situation of profound threat that is, at the same time, profoundly confirming. (p. 2)

The participants use the birds to signify optimism that sustains place attachment in a toxic geography. That optimism inspires one to litter pick in his leisure time, a form of polluted leisure. Yet, as Berlant notes, the individual as being able to improve circumstances for the better, when in fact what is required is structural change or, indeed, ontological and epistemological transformation is foundational to cruel optimism. The litter picker’s striving for well-being through polluted leisure individuates change and attachment, arguably an act of survival that unfortunately distracts from the structural, ontological, and epistemological steps required to realize alternative green futures.

Some of the other men in the group are magnet fishermen, who use powerful magnets to scavenge for metallic industrial waste to ‘hang onto their history’ (e.g. tools). When they discussed photographs with the litter picker there was disagreement. One person mentioned that the litter picker takes stuff away ‘will nilly’ without ‘appreciating the history’ of some of the items . The magnet fishermen use their polluted leisure to remain attached to the industrial history of the place, to ensure that ‘the past is not forgotten’. Pollution isn’t necessarily matter out of place (Douglas, Citation1996), but can be a sign of life (Reno, Citation2014).

While the magnet fishermen regularly represented and celebrated past industrial economic accomplishments in some collages they made, they also represented future economic growth based on those past industrial economic accomplishments. Their vision was the rebuilding of previously thriving industries that ‘made them who they are’. It’s another story of cruel optimism and place attachment.

Collage by participant. Photo by author.

It would be easy to be quick to judge their place attachment and polluted leisure that celebrates a return of industries that did so much environmental damage. And I did, initially thinking of what they describe as bad or negative attachment. This interpretation is simplistic and a mistake. In fact, Berlant (Citation2011) warns against such a move when she writes

Even when it turns out to involve a cruel relation, it would be wrong to see optimism’s negativity as a symptom of an error, a perversion, damage, or a dark truth: optimism is, instead, a scene of negotiated sustenance that makes life bearable as it presents itself ambivalently, unevenly, incoherently. (p.14)

The magnet fishermen’s attachment to place and use of their leisure to inform a particular optimistic story of an economic future is sensible. The magnet fishing connects them with a heritage that they feel proud of and that sustained well-being for centuries. Those industries continue to do so through the tools scavenged during polluted leisure. Each find is a thrill that resonates with pride and heritage, making life bearable until a better future arrives.

A participant banner. Photo by author.

When documenting South Gare and Seal Sands a group of surfers prioritized representing the post-industrial esthetics of heavy industry and falling ill from immersion in the sea and river. Images included: surfing in front of the burn off flames from a chemical plant chimney and a rusted blast furnace from an abandoned steelwork; riding waves next to container ships docking at the port and oil rigs; and most recently protests about the construction of a Freeport. The construction has caused much controversy due to increased dredging of the River Tees, which has stirred up toxins they are only now learning the names of, unlike the birds e.g. pyridine. Pyridine is a colorless flammable liquid with a strong and unpleasant fish-like odor. It is used as a solvent for paints, rubber, dyes and resins. A small amount of pyridine may occur naturally in the environment but is more often a result of human activities. It is deadly to crustaceans. Surfers, fishing enthusiasts, and university researchers claim the stirring up of pyridine led to a mass die-off of marine life in 2021, particularly crustaceans. The UK Environment Agency and local government deny the claim.

As they made the banner the surfers discussed conflicting feelings they have about the relationship between pollution, industry, and leisure.

I can feel happy in the middle of all the industry, even though you can see it’s also meant pain for the animals and us when we get sick. I shouldn’t feel happy when I surf here, but I do.

Surfing makes me happy too. I find the mix of nature and industry unique. It’s north-east surfing. It’s not all the tropical magazine stuff here. This is the reality. The bad stuff like the industry is part of me and us and surfing but so is the good stuff like surfing with the seals.

I’m addicted to the place and surfing. When I surf here it clears my head and I’ll feel better. There’s nothing reasonable about that though. It’s just a feeling. Like he said, there’s fun and pain. Yeah, there’s both.

The mixture of surfing, animal encounters, industry, and pollution create a fractured narrative of attachment, well-being, and polluted leisure. Surfing can be a moment of temporary care and respite from the complications of life here, even though it happens in a toxic geography. The men went on to share their collective grief about a friend who they don’t see ‘around the place anymore’ and they think ‘he’s even stopped surfing altogether!’ He’s ‘one of the lads’ because he used to work and surf with them for decades. They’re ‘worried about how he’s doing’. It’s an expression of care.

Care of men toward other men can take place in unexpected ways and places, challenging traditional masculine norms. Feminist scholars have been critically evaluating and examining the ethics of care for a long time (Gilligan, Citation1982; Puig de la Bellacasa, Citation2017). Normatively, care is not celebrated openly as a part of masculine norms in this region, yet it does occur (Bonner-Thompson & McDowell, Citation2020). Practices of care expressed by men are relational and place-specific, and not always positive (Ibid).

At a later group beachcombing one of the surfers was present and told me he’d ‘rescued that friend’ and ‘he’s over here’. I was wary of this pressure and let the individual know it was alright to not talk to me. He insisted.

I’m here now, ain’t I? He’s just looking out for me. He’s trying. I didn’t like him pestering me to come to this place though. I’ve tried to stay away because it depresses me. Let me show you the mess they won’t face up to so they can feel good here

He walks me to a part of the beach where dead crabs are piled knee-high.

It’s an apocalypse. They’ll step over the bodies and still fish and surf! I can’t do that. They’ve gotten too used to this sort of thing or they’re in denial. I get angry and then feel at a bit of a loss. The pollution is killing the crabs and it’s probably killing us too.

Research has found that pollution may discourage people from outdoor leisure (An & Xiang, Citation2015). However, it has also been found that pollution may not deter other people from visiting waterways for walking, boating, fishing, and swimming, especially when they are used to it (Ziv et al., Citation2016). People who are attached to place tend to perceive it as less polluted and risky than someone without an established relationship to the area (Rollero & De Piccoli, Citation2010). But what about the denialism mentioned?

Polluted leisure activities can be used to come to terms with, resist, and cope with pollution, but can also work as a form of denialism. To understand the denialism, we can turn to Kari Marie Norgaard’s (2011) research about climate denialism in everyday life in a small rural town in Norway, through which she argues that people will try to protect themselves from uncomfortable emotions such as helplessness, doubt, guilt, and shame. I raised this argument with the surfers during a session in which we were mending the banner which has got damaged in transit. One person tells me that the pollution and die off upsets them ‘all the time too … how couldn’t it!?’ Another of the men adds ‘don’t dwell on it too much or you’ll end up like “Dave”’ [pseudonym of the participant who mentioned denialism]. He continues

If you get angry, you’ll stop coming here [South Gare] and that’ll make it harder to stick around … if you can get a little bit of joy here you can survive here, what’s the point otherwise?

Norgaard notes that denialism is connected to privilege. For example, not having to face the worst of the environmental violence and damage during everyday life. The men’s denialism via polluted leisure is a form of white male privilege. Individuals from minoritized backgrounds are most affected by the destruction of the Anthropocene, and denialism is not possible. However, Teesside is a contaminated community. The men are attached to a toxic geography. The circumstances are different to Norgaard’s Norwegian study site. There’s more to this denialism than privilege.

Norgaard mentions that men are under greater pressure to manage the emotions than women, particularly concerning climate change. This point fits with the wider literature on masculinity and emotional management (de Boise & Hearn, Citation2017). It also fits with how men in the region tend to avoid and decry discussing difficult emotions (Bonner-Thompson & McDowell, Citation2020), as the conversation presented earlier about dead crabs and surfing, demonstrates. By participating in polluted leisure activities some of the men can experience positive emotions that sustain attachment to place and concomitant well-being. At the same time, they can avoid the difficult emotions and manage emotional distress connected to an environmental disaster.

The Freeport’s construction also prompted some artisanal fishermen to debate the recovery of the place and indeed themselves. The South Tees Development Corporation promotes the Freeport as part of the recovery of South Gare and the wider Teesside conurbation. It is a framing of recovery through a medical sensibility, which is a restoration to a prior state of ‘health’. The South Tees Development Corporation is reclaiming so-called unproductive and wasted spaces for capital. The fishermen weren’t ‘sold on this recovery since the die off’. I experienced a profound moment when fishing with one of the men during winter, when South Gare is at its most wild and wooly. It is brutally cold and can all look a bit bleak and dystopian as the storms are regular, winds strong, and sunshine weak. It’s when it’s ‘throwntogetherness’ is most vivid. This is the terminology used by cultural geographer Doreen Massey (Citation1994) to refer to thinking about (and with) place: a ‘time-space’ of relational encounters, open and progressive, full of potential, and of the eventfulness of place. This fisherman doesn’t speak much, so I wasn’t expecting the observation.

You know, we’ve suffered a lot, so we need this place. We don’t just need jobs. The place looks like a mess to outsiders, but we know it well … I love it. I need this place to go fishing and walk the dog. I can come here and do nothing too. It’s a place to do my own thing. I think a few people come here to heal in their own way. We all got tossed together and cast aside, up here [South Gare]. I’m worried with all the development they’ll change the place. They [developers, government, industry] want it back … They may take it away because it’s an eyesore for the fat cats. We’re an eyesore.

The reason I found this monologue profound, beyond my surprise at him speaking up, is because he gestures toward a form of recovery through ‘throwntogetherness’ rather than the medical model. The contamination and ramshackle conditions of the area have caused people to deepen and form new connections to it, allowing them to reclaim their self-worth and autonomy in a place where these were previously taken away by those same interests and economic structures who now seek to profit from exploiting the place and people further.

Some men have deepened and formed new attachments to place as well as moments to reflect on how they relate to humans and non-humans. Any story about well-being is not framed as ‘in spite of’ the harm, flaws, pollution, dereliction, wounding, and negligence. Rather stories of striving for well-being include explanations of living with these features and the challenges in doing so.

Donna Haraway (Citation2016) calls for us to form relationships with non-human life forms to reject the logic of domination and consequently many Global North men’s environmental ideology. Polluted leisure, though not ideal, can create a sense of curiosity in some men around the relationship between humans and non-humans and even motivate them to resist any effortless re-creation of beliefs and orientations that sustain catastrophic environmental perspectives.

Conclusion

Place attachment augments men’s relationships with pollution and well-being sensibilities during their polluted leisure. Including analysis of place attachment when considering polluted leisure provides a platform to reflect on the relationship between humans and non-humans and learn from men unforeseen moments of resistance any seamless re-creation of a traditional masculine Western logic of domination and associated orientations that sustain catastrophic environmental perspectives, cultures, and socio-economic structures. With pollution, some men have been able to find moments of care and connection with their environment and each other, providing a unique insight into how they are living in a toxic geography. For example, in relation to cruel optimism, denialism, and recovery. As I am with the men, I am witnessing some men take small steps toward the sort of ontological and epistemological shifts—a part of nature rather than apart (Hawke, Citation2022)—needed to construct, narrate, and fabricate necessary narratives of well-being out of fractured, complicated, conflictual, disputed, and uncertain conditions of possibility amid a post-industrial geography (Mah, Citation2010; Warren, Citation2017). There are moments of dispute that evidence curiosity about what can be done differently, as we confront a catastrophic environmental reality. These small, humble, even vulnerable actions could be of great consequence (Probyn, Citation2021). As ecofeminists have long argued, it is the everyday material practices that make life among ruination livable (MacGregor, Citation2021). So, mine is a sympathetic framework of men and the environment through which it is possible to work with men and boys on progressive, healthy, ethical, caring, and environmentally friendly identities and practices so we can better live on a damaged planet together.

Feminists Gibson et al. (Citation2015) suggest we pursue methodologies of connection and interdependence as part of our daily living in the Anthropocene. They maintained that the rejection of a logic of domination as well as separation or binary thinking is imperative in recognizing the realities that human and non-human beings co-produce. Polluted leisure can evoke reflection about and critique of place attachment and a logic of domination and binary thinking as through it we come to know and appreciate ‘throwntogetherness’. Sometimes polluted leisure can evoke new, critical ideas that could, if encouraged, lead to different ways of living .

I am not being idealistic in my outlook. Rather, I see it as critical for men not to shield our/themselves from environmental catastrophe and to face up to complicities past and present. Caring for ourselves and each other’s well-being and demonstrating our attachment to a particular place using polluted leisure activities is crucial even if at times it is motivated by selfish reasons. Care is not always positive; it can also work as control and violence. Male politicians and developers in Teesside also purport to show concern for community and place but remain mired in the logic of domination and binary thinking as evidenced by their approach to managing and recovering South Gare.

Further, what is considered care-full here may not be the same elsewhere. According to feminist philosopher Val Plumwood (Citation2008), any effort to care for our community and home place must be taken in connection to what she calls ‘shadow places’, that are ‘the multiple disregarded places of economic and ecological support’ (p. 139). We have a duty of care to remember, acknowledge and take responsibility for such shadow places. Teesside is connected to the global shadow places through UK colonialism and its industrial-level polluting of the planetary oceans and atmosphere. Place attachment cannot simply be about where we are familiar and more obviously attached. During my study I did not prompt the participants to think about the global connections between place attachment, polluted leisure, and well-being. This is perhaps a mistake that has left me wondering if polluted leisure can connect and nurture more collective and inclusive well-being globally, including shadow places? An expanded and relational notion of connection to multiple places, people, and species is needed in the face of environmental crises (Potter et al., Citation2022). Additionally, there is a call to challenge the established and intricate network of capitalism and fossil fuel industries that moves through and across the planet in ways that shape the economic, social, and cultural components of leisure. This paper gestures toward that realization.

Acknowledgments

I am deeply thankful to the multiple places, people, and species both local and global who contributed their wisdom to this research. This has been instrumental in the formation of this article, and the men and I will endeavour to use it to contribute more ethically and care-fully to living in the Anthropocene.

Disclosure statement

The author(s) declare no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 In this article, the term "England" is used to specifically denote the independent country, while "United Kingdom" (UK) encompasses a broader framework that includes England, Scotland, Wales, and Northern Ireland as interconnected entities in terms of governance and geography. The evidence presented in the article may at times pertain solely to the context of England, while at other times it may encompass the wider context of the entire UK. It is important to note that the term "British" refers to the citizens of the broader UK, whereas "English" specifically refers to the citizens of England.

References

- Alaimo, S. (2016). Exposed: Environmental politics and pleasure in posthuman times. University of Minnesota Press.

- An, R., & Xiang, X. (2015). Ambient fine particulate matter air pollution and leisure-time physical inactivity among US adults. Public Health, 129(12), 1637–1644. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.puhe.2015.07.017

- Atherton, K. (2019). The concept of masculinity and male suicide in north-east England. Psychreg Journal of Psychology, 3(2), 37–51.

- Atkinson, S. (2013). Beyond components of wellbeing: The effects of relational and situated assemblage. Topoi : An International Review of Philosophy, 32(2), 137–144. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11245-013-9164-0

- Balayannis, A. (2020). Toxic sights: The spectacle of hazardous waste removal. Environment and Planning D: Society and Space, 38(4), 772–790. https://doi.org/10.1177/0263775819900197

- Bell, S. L., Phoenix, C., Lovell, R., & Wheeler, B. W. (2015). Seeking everyday wellbeing: The coast as a therapeutic landscape. Social Science & Medicine (1982), 142, 56–67. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2015.08.011

- Bell, S. L., Westley, M., Lovell, R., & Wheeler, B. W. (2018). Everyday green space and experienced well-being: The significance of wildlife encounters. Landscape Research, 43(1), 8–19. https://doi.org/10.1080/01426397.2016.1267721

- Berlant, L. (2011). Cruel optimism. Duke University Press.

- Blackshaw, T. (2003). Leisure life: Myth, modernity and masculinity. Routledge.

- Bonner-Thompson, C., & McDowell, L. (2020). Precarious lives, precarious care: Young men’s caring practices in three coastal towns in England. Emotion, Space and Society, 35, 100684. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.emospa.2020.100684

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2021). Thematic analysis: A practical guide. SAGE.

- Britton, E., Kindermann, G., Domegan, C., & Carlin, C. (2020). Blue care: A systematic review of blue space interventions for health and wellbeing. Health Promotion International, 35(1), 50–69. https://doi.org/10.1093/heapro/day103

- Brough, A. R., Wilkie, J. E. B., Ma, J., Isaac, M. S., & Gal, D. (2016). Is eco-friendly unmanly? The green-feminine stereotype and its effect on sustainable consumption. Journal of Consumer Research, 43(4), 567–582. https://doi.org/10.1093/jcr/ucw044

- Carpiano, R. M. (2009). Come take a walk with me: The "go-along" interview as a novel method for studying the implications of place for health and well-being. Health & Place, 15(1), 263–272. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthplace.2008.05.003

- Carruthers, C. P., & Hood, C. D. (2004). The power of the positive: Leisure and well-being. Therapeutic Recreation Journal, 38(2), 225–245.

- Castro, L. R., Barry, K., Bhattacharya, D., Pini, B., Boyd, C., Ben, D., Bayes, C., Nevin, B., Narayan, P., Lobo, M., Ginsberg, N., & Hine, A. (2023). Editorial introduction: Geography and collective memories through art. Australian Geographer, 54(1), 13–31. https://doi.org/10.1080/00049182.2022.2052556

- Chang, P.-J., Song, R., & Lin, Y. (2019). Air pollution as a moderator in the association Between leisure activities and well‑being in urban China. Journal of Happiness Studies, 20(8), 2401–2430. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-018-0055-3

- Cherrington, J., & Black, J. (2023). Sport and physical activity in catastrophic environments. Routledge.

- Connell, R. W. (1995). Masculinities. Routledge.

- Crossley, N., & Edwards, G. (2016). Cases, mechanisms and the real: The theory and methodology of mixed-method social network analysis. Sociological Research Online, 21(2), 217–285. https://doi.org/10.5153/sro.3920

- Crutzen, P. J., & Stoermer, E. F. (2000). The Anthropocene. In L. Robin, S. Sörlin & P. Warde (Eds.), The future of nature (pp. 483–490). Yale University Press.

- Daggett, C. (2018). Petro-masculinity: Fossil fuels and authoritarian desire. Millennium: Journal of International Studies, 47(1), 25–44. https://doi.org/10.1177/0305829818775817

- Davies, T. (2022). Slow violence and toxic geographies: ‘Out of sight’ to whom? Environment and Planning C: Politics and Space, 40(2), 409–427. https://doi.org/10.1177/2399654419841063

- de Boise, S., & Hearn, J. (2017). Are men getting more emotional? Critical sociological perspectives on men, masculinities and emotions. The Sociological Review, 65(4), 779–796. https://doi.org/10.1177/0038026116686500

- De Rijke, V. (2023). The And Article: Collage as research method. Qualitative Inquiry. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1177/10778004231165983

- Denton, H., & Aranda, K. (2020). The wellbeing benefits of sea swimming. Is it time to revisit the sea cure? Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health, 12(5), 647–663. https://doi.org/10.1080/2159676X.2019.1649714

- Di Chiro, G. (2017). Welcome to the white (M)Anthropocene? A feminist-environmentalist critique. In S. MacGregor (Ed.), Routledge handbook of gender and environment (pp. 487–505). Routledge.

- Douglas, M. (1996). Purity and danger: An analysis of concepts of pollution and taboo. Routledge.

- Dwyer, S. C., & Buckle, J. L. (2009). The space between: On being an insider-outsider in qualitative research. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 8(1), 54–63. https://doi.org/10.1177/160940690900800105

- Evers, C. (2016). Researching action sport with a GoPro™ camera: An embodied and emotional mobile video tale of the sea, masculinity, and men-who-Surf. In I Wellard (Ed.), Researching embodied sport: Exploring movement cultures (pp. 145–162). Routledge.

- Evers, C. (2018). Wearable technology and visual analysis. In K. Green, S. Lageson, D. Hartmann & C. Uggen (Eds.), Give methods a chance (pp. 155–164). WW Norton.

- Evers, C. (2019a). Polluted leisure. Leisure Sciences, 41(5), 423–440. https://doi.org/10.1080/01490400.2019.1627963

- Evers, C. (2019b). Polluted leisure and blue spaces: More-than-human concerns in Fukushima. Journal of Sport and Social Issues, 45(2), 179–195. https://doi.org/10.1177/0193723519884854

- Evers, C., & Phoenix, C. (2022). Relationships between recreation and pollution when striving for wellbeing in blue spaces. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(7), 4170. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19074170

- Foley R., Kearns R., Kistemann T., & Wheeler B. (Eds.). (2019). Blue space, health and wellbeing: Hydrophilia unbounded. Routledge.

- Gascon, M., Zijlema, W., Vert, C., White, M. P., & Nieuwenhuijsen, M. J. (2017). Outdoor blue spaces, human health and wellbeing: A systematic review of quantitative studies. International Journal of Hygiene and Environmental Health, 220(8), 1207–1221. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijheh.2017.08.004

- Gerstenblatt, P. (2013). Collage portraits as a method of analysis in qualitative research. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 12(1), 294–309. https://doi.org/10.1177/160940691301200114

- Gibson, K., Rose, D. B., & Fincher, R. (2015). Manifesto for living in the Anthropocene. Punctum Books.

- Gilligan, C. (1982). In a different voice: Psychological theory and women’s development. Harvard University Press.

- Gorman-Murray, A., & Hopkins, P. (Eds.). (2014). Masculinities and place. Ashgate.

- Green, K., & Evers, C. (2020). Intimacy on the mats and in the surf. Contexts, 19(2), 10–15. https://doi.org/10.1177/1536504220920188

- Hall, S. (1997). Representation: Cultural representations and signifying practices. SAGE.

- Haraway, D. J. (2016). Staying with the trouble: Making kin in the chthulucene. Duke University Press.

- Hawke, S. (2022). A part of nature or apart from nature. A case for bio-philiation. Visions for Sustainability, 18. https://www.ojs.unito.it/index.php/visions/article/view/6713

- Haybron, D. M. (2008). Philosophy and the science of subjective well-being. In M. Eid & R. J. Larsen (Eds.), The science of subjective well-being (pp. 17–43). Guilford Press.

- Haywood, C. (2022). Sex clubs: Recreational sex, fantasies and cultures of desire. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Hickey-Moody, A. (2020). New materialism, ethnography, and socially-engaged practice: Space-time folds and the agency of matter. Qualitative Inquiry, 26(7), 724–732. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077800418810728

- Huang, G., Jiang, Y., Zhou, W., Pickett, S. T. A., & Fisher, B. (2023). The impact of air pollution on behavior changes and outdoor recreation in Chinese cities. Landscape and Urban Planning, 234, 104727. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.landurbplan.2023.104727

- Hultman, M., & Pulé, P. M. (2018). Ecological masculinities: Theoretical foundations and practical guidance. Routledge.

- Johnson, C. W., & Cousineau, L. S. (2018). Manning up and manning on: Masculinities, hegemonic masculinity, and leisure studies. In D. Parry (Ed.), Feminisms in leisure studies: Advancing a fourth wave (pp. 127–148). Routledge.

- Leavy, P. (2017). Research design: Quantitative, qualitative, mixed methods, arts-based, and community-based participatory research approaches. Guilford Press.

- Lewicka, M. (2011). Place attachment: How far have we come in the last 40 years? Journal of Environmental Psychology, 31(3), 207–230. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2010.10.001

- Liebenberg, L. (2018). Thinking critically about photovoice: Achieving empowerment and social change. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 17(1). https://doi.org/10.1177/1609406918757631

- Liechty, T., & Genoe, M. R. (2013). Older men’s perceptions of leisure and aging. Leisure Sciences, 35(5), 438–454. https://doi.org/10.1080/01490400.2013.831287

- Lora-Wainwright, A. (2021). Resigned activism: Living with pollution in rural China. MIT Press.

- Loughborough University. (2021, May 19). Dramatic rise in child poverty in the last five years. https://www.lboro.ac.uk/news-events/news/2021/may/dramatic-rise-in-child-poverty/

- MacGregor, S. (2021). Making matter great again? Ecofeminism, new materialism and the everyday turn in environmental politics. Environmental Politics, 30(1-2), 41–60. https://doi.org/10.1080/09644016.2020.1846954

- MacGregor, S. (Ed.). (2017). Routledge handbook of gender and environment. Routledge.

- MacGregor, S., & Seymour, N. (Eds.). (2017). Men and nature: Hegemonic masculinities and environmental change. Rachel Carson Centre Perspectives, 4. https://www.environmentandsociety.org/perspectives/2017/4/men-and-nature-hegemonic-masculinities-and-environmental-change

- Mackenzie, S. H., & Hodge, K. (2020). Adventure recreation and subjective well-being: A conceptual framework. Leisure Studies, 39(1), 26–40. https://doi.org/10.1080/02614367.2019.1577478

- Mah, A. (2010). Memory, uncertainty and industrial ruination: Walker Riverside, Newcastle upon Tyne. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 34(2), 398–413. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2427.2010.00898.x

- Mair, M. (2022). Wasted: Towards a critical research agenda for disposability in leisure. Leisure Studies, 1–9. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1080/02614367.2022.2148718

- Mansfield, L., Daykin, N., & Kay, T. (2020). Leisure and wellbeing. Leisure Studies, 39(1), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1080/02614367.2020.1713195

- Manzo, L., & Devine-Wright, P. (2011). Place attachment: Advances in theory, methods and applications. Routledge.

- Massey, D. (1994). For space. SAGE.

- McDowell, L., & Bonner-Thompson, C. (2020). The other side of coastal towns: Young men’s precarious lives on the margins of England. Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space, 52(5), 916–932. https://doi.org/10.1177/0308518X19887968

- Moles, K. (2008). A walk in third space: Place, methods and walking. Sociological Research Online, 13(4), 31–39. https://doi.org/10.5153/sro.1745

- Moore, J. W. (Ed.). (2016). Anthropocene or Capitalocene?: Nature, history, and the crisis of capitalism. PM Press.

- Nayak, A. (2006). Displaced masculinities: Chavs, youth and class in the post-industrial city. Sociology, 40(5), 813–831. https://doi.org/10.1177/0038038506067508

- Nixon, R. (2011). Slow violence and the environmentalism of the poor. Harvard University Press.

- Noorgaard, K. M. (2011). Living in denial: Climate change, emotions, and everyday life. MIT Press.

- O’Connor, P., Evers, C., Glenney, B., & Willing, I. (2022). Skateboarding in the Anthropocene: Grey spaces of polluted leisure. Leisure Studies, 1–11. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1080/02614367.2022.2153906

- Office for National Statistics. (2021). Census 2021. https://www.ons.gov.uk/

- Olive, R. (2022). Swimming and surfing in ocean ecologies: Encounter and vulnerability in nature-based sport and physical activity. Leisure Studies, 1–14. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1080/02614367.2022.2149842

- Olive, R., & Wheaton, B. (2021). Understanding blue spaces: Sport, bodies, wellbeing, and the sea. Journal of Sport and Social Issues, 45(1), 3–19. https://doi.org/10.1177/0193723520950549

- Paulsen, M., Jagodzinski, J., & Hawke, S. M. (2022). Pedagogy in the Anthropocene: Re-wilding education for a new earth. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Pitt, H. (2018). Muddying the waters: What urban waterways reveal about blue spaces and wellbeing. Geoforum, 92, 161–170. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2018.04.014

- Plumwood, V. (1993). Feminism and the mastery of nature. Routledge.

- Plumwood, V. (2008). Shadow places and the politics of dwelling. Australian Humanities Review, 44, 139–150.

- Potter, E., Miller, F., Lövbrand, E., Houston, D., McLean, J., O’Gorman, E., Evers, C., & Ziervogel, G. (2022). A manifesto for shadow places: Re-imagining and co-producing connections for justice in an era of climate change. Environment and Planning E: Nature and Space, 5(1), 272–292. https://doi.org/10.1177/2514848620977022

- Pringle, R., Kay, T., & Jenkins, J. M. (2011). Masculinities, gender relations and leisure studies: Are we there yet? Annals of Leisure Research, 14(2-3), 107–119. https://doi.org/10.1080/11745398.2011.618447

- Probyn, E. (2021). Wasting seas: Oceanic time and temporalities. In F. Allon, R. Barcan & K. Eddison-Cogan (Eds.), The temporalities of waste: Out of sight, out of time (pp. 179–191). Routledge.

- Puig de la Bellacasa, M. (2017). Matters of care: Speculative ethics in more than human worlds. University of Minnesota Press.

- Reno, J. O. (2014). Toward a new theory of waste: From ‘matter out of place’ to signs of life. Theory, Culture & Society, 31(6), 3–27. https://doi.org/10.1177/0263276413500999

- Riddett-Moore, K., & Siegesmund, R. (2012). Arts-based research: Data are constructed, not found. In S. R. Klein (Ed.), Action research methods (pp. 105–132). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Rollero, C., & De Piccoli, N. (2010). Place attachment, identification and environment perception: An empirical study. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 30(2), 198–205. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2009.12.003

- Román, S., & Molinero-Gerbeau, Y. (2023). Anthropocene, Capitalocene or Westernocene? On the ideological foundations of the current climate crisis. Capitalism Nature Socialism, 1–19. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1080/10455752.2023.2189131

- Sikka, T. (2019). Climate technology, gender, and justice: The standpoint of the vulnerable. Springer-Verlag.

- Spannring, R., & Hawke, S. (2022). Anthropocene challenges for youth research: Understanding agency and change through complex adaptive systems. Journal of Youth Studies, 25(7), 977–993. https://doi.org/10.1080/13676261.2021.1929886

- Stinson, M. J., & Grimwood, B. S. R. (2022). Defacing: Affect and situated knowledges within a rock climbing tourismscape. Journal of Sustainable Tourism, 30(7), 1602–1620. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669582.2020.1850748

- Stoodley, L., & lisahunter. (2021). Bluespace, senses, wellbeing, and surfing: Prototype cyborg theory-methods. Journal of Sport and Social Issues, 45(1), 88–112. https://doi.org/10.1177/0193723520928593

- Sultana, F. (2022). The unbearable heaviness of climate coloniality. Political Geography, 99, 102638. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.polgeo.2022.102638

- Taylor, D. E. (2014). Toxic communities: Environmental racism, industrial pollution, and residential mobility. New York University Press.

- Tees Valley Combined Authority. (2021). Local skills report Tees Valley annexes: Core indicators and additional data. https://teesvalley-ca.gov.uk/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/Local-Skills-Report-Annexes-Core-Indicators-and-Additional-Data-18-06-21.pdf#:∼:text=%E2%80%A2%20In%20addition%20to%20ranking%20as%20one%20of,the%20most%20deprived%2015%25%20of%20local%20authorities%20nationally

- Thorpe, H., Brice, J. E., & Clark, M. (2020). Feminist new materialisms, sport, and fitness: A lively entanglement. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Tirone, S., & Halpenny, E. (Eds.). (2019). Leisure and sustainability. Routledge.

- Twine, R. (2021). Masculinity, nature, ecofeminism, and the “Anthropo”cene. In P. M. Pulé, & M. Hultman (Eds.), Men, masculinities, and earth. Palgrave Macmillan.

- United Nations Women. (2022, February 28). How gender inequality and climate change are interconnected. https://www.unwomen.org/en/news-stories/explainer/2022/02/explainer-how-gender-inequality-and-climate-change-are-interconnected

- United Nations. (2021). United Nations sustainable development goals, 2021. https://www.un.org/en/desa/sustainable-development-goals-sdgs

- Warren, J. (2017). Industrial Teesside, lives and legacies: A post-industrial geography. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Watson, A. (2020). Methods Braiding: A technique for arts-based and mixed-methods research. Sociological Research Online, 25(1), 66–83. https://doi.org/10.1177/1360780419849437

- Watson, J. (2015). Multiple mutating masculinities. Angelaki, 20(1), 107–121. https://doi.org/10.1080/0969725X.2015.1017387

- Wheaton, B., Waiti, J., Cosgriff, M., & Burrows, L. (2020). Coastal blue space and wellbeing research: Looking beyond western tides. Leisure Studies, 39(1), 83–95. https://doi.org/10.1080/02614367.2019.1640774

- Yang, J. P. (2020). The impact of environmental pollution on leisure sports activities of urban residents. Journal of Coastal Research, 104(sp1), 913–916. Special Issue. https://doi.org/10.2112/JCR-SI104-157.1

- Zajchowski, C. A. B., & Rose, J. (2020). Sensitive leisure: Writing the lived experience of air pollution. Leisure Sciences, 42(1), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1080/01490400.2018.1448026

- Ziv, G., Mullin, K., Boeuf, B., Fincham, W., Taylor, N., Villalobos-Jimenez, G., Vittorelli, L., Wolf, C., Fritsch, O., Strauch, M., Seppelt, R., Volk, M., & Beckmann, M. (2016). Water quality is a poor predictor of recreational hotspots in England. PloS One, 11(11), e0166950. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0166950