Abstract

This paper demonstrates how liminality provides a core framework for understanding the processes and practices through which Lego® Serious Play® can positively influence the student experience and wellbeing of children and young people (CYP). The study adopts a creative multi-sensory methodology whereby the focus is upon the Lego® and not the child. Using a play-based learning approach within an educational setting, data was collected in a UK junior school, involving sixty-four children, ranging from seven to eleven years of age. An initial group session was repeated two weeks later to monitor and observe changes. The results highlight that the Lego® Serious Play® methodology uses liminality to further the debate about the use of play as a leisure-based activity in educational settings. This study contributes to knowledge by utilizing Lego® Serious Play® (LSP) through a playful lens as a creative methodology and highlights the unique interaction between leisure, liminality and Lego®.

Introduction

The focus of this study is upon using a playful lens (Reeve, Citation2021) to create a positive narrative surrounding those children and young people (CYP), in this case school children, who were so negatively affected by the covid-19 global pandemic. The main purpose of this study was to help better manage pupil anxiety and facilitate a clearer understanding of the school ‘transition process’, whereby pupils move either between year groups, or to a new school (Shipway, Henderson & Inns, Citation2022). An associated research question was to explore how Lego® Serious Play® can support children’s mental health, when delivered in everyday educational environments, and with the focus upon the immersion of children within a leisure-based activity. Using Lego® Serious Play® to unlock tacit knowledge is an essential basis for developing children’s ability to express and understand problems (Collins, Citation2001). Without the transformation of tacit knowledge children can become confused in how to solve the underlying issues or challenges they face (Tan et al Citation2019; Chamidy et al Citation2020). We propose that the interaction of leisure, Lego®, and liminal experiences, with tacit knowledge transfer, can offer a mechanism for platforming and amplifying diverse, authentic voices and perspectives of children within those settings. It can also allow children and young people (CYP) to feel comfortable expressing their personal views and lived liminal experiences, given the focus is more on the model constructed than on the child.

Using the creative methodology of Lego® Serious Play®, this study draws further attention to the contemporary landscape of mental health and wellbeing, and the liminal experiences that children and young people (CYP) bring to their education environment and everyday social and leisure-based encounters, within the school setting. The Lego® Serious Play® method is one where “participants use Lego blocks as mediating artefacts to build symbolic or metaphorical representations of abstract concepts” (McCusker, Citation2014, p. 27). The study also advocates the increased use of new pedagogies such as play-based learning and Lego® Serious Play®. The findings explore the potential for real-world impact from this creative methodological approach, and a co-created process whereby both children and teachers are actively involved in the development and testing of the study (Shipway & Henderson, Citation2023).

An overview of the literature

Liminality

Liminality was developed in the field of anthropology to explain the phases in the tribal ritual processes where an ambiguous state is created by participants (Turner, Citation1982). Liminality has been used “to describe a subjective state of being on the ‘threshold’ of, or betwixt and between, two different existential positions, and it presents a particular challenge for the enactment of identity” (Ybema et al., Citation2011, p. 22). Liminoid is a term developed to describe a temporary state during the change associated with liminality, but in secular rather than sacred terms, and it has been broadly used to describe political and cultural change, and the temporary state in the change (Lee et al., Citation2016).

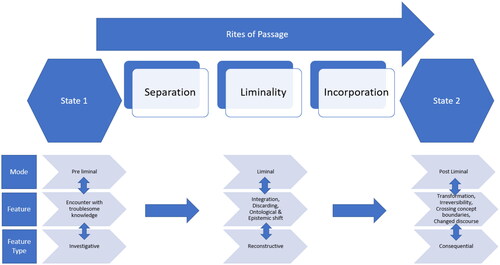

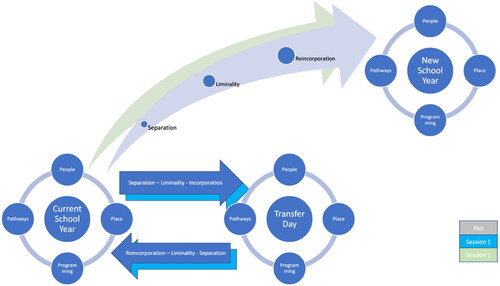

The origins of liminality are not a new phenomenon, being first explored by van Gennep (Citation1960) when considering the links between separation, liminality and (re)incorporation, and the various stages in the rites of passage sequence (Söderlund & Borg, Citation2018), as illustrated in . As noted by Turner (Citation1967), these concepts further evolved to consider the existing ambiguity of social boundaries and inbetweenness. A person’s personality is shaped by the experience of liminality as well as the integration of the liminal experience and the sense of communitas provided in the liminal space (Turner Citation1969). This sense of communitas it is made up of people who are a community of equal individuals, be it structured or unstructured (Lee et al., Citation2016). Communitas, as the temporary state of communal human relationship, is identified as one of the ambiguous states constructed through liminality or during the liminoid phase (Turner, Citation1982). Lee et al (Citation2016) highlight a special sense of togetherness that exists outside ordinary social structure where participants have something very specific in common and can build temporary relationships among themselves within the group.

Figure 1. Stages in the rites of passage schematic showing van gennep’s rites of passage sequence (from Söderlund & Borg, Citation2018) integrating threshold concepts and troublesome knowledge (Land et al Citation2005).

In the leisure context, Lee et al (Citation2016) acknowledge that leisure practices contain a liminoid phenomenon as a leisure activity is an experience occurring outside normal social processes, and participants can experience the transient state whilst engaged in their leisure practice. In the context of this study, for school children liminality is a rite of passage each year of their formative and formal education, as they transition either between schools or year groups. Hockey (Citation2002) notes that it commences with the termination of the previous social state, followed by a period of ambiguity and being betwixt and between positions, and concludes with the reentry into a new social position. The use of liminality as a notion and framework has evolved and grown in several disciplines, including leisure. For example, in health studies liminality is at the core of understanding the participants experience of betwixt and between (Atkinson & Robson Citation2012). Whilst our study is embedded in mental health and wellbeing, liminality has also been investigated in health studies linked to dialysis (Martin-McDonald & Biernoff Citation2002), cancer (Mckenzie Citation2004), and strokes (Donetto et al Citation2021). Atkinson and Robson (Citation2012, p. 1352) found “arts-based interventions can generate the relational and transitional spaces, characterized by security, social integration, therapeutic experiences and capabilities, within which resources may be built and mobilized to affect the gains in a situated personal wellbeing” .This creation of space that lends itself to wellbeing is essential and has been adopted in the use of liminality to explore co-design and/or participatory research in a health care setting (Donetto et al, Citation2021). Their study identifies the use of liminality as an analytical lens to further understand the integration of the relationship the environment, mind, and body. This approach has similarities with our own exploration in the context of mental health and wellbeing.

When considering the use of liminality in education and learning in a higher education context, early scholars highlighted the positive outcomes of strategy development to enable students to be supported appropriately through a transition period (Meyer & Land Citation2005). They highlighted that once students were reincorporated, they were able to grow and display characteristics of transformation. However, not all education-based studies using liminality were positive (Kligyte et al (Citation2022). For example, Keefer (Citation2015, p. 18) identified feelings of “uncertainty, confusion, and lack of confidence”, and that adopting liminal approaches often left participants in “a suspended state in which students sometimes can struggle to cope”. This highlights the difficulty in understanding liminality thresholds and the proposed delineation of this by mode, feature and type (Land et al, Citation2005, Citation2010). integrates and presents this concept, which is likened to Van Gennep’s rites of passage. However, the addition of ‘feature’ and ‘type’ could act as a further resource for building strategy and support for students. Within the preliminal mode of the threshold model is the encounter with troublesome knowledge, which can be tacit knowledge (Land et al Citation2005). The key driver behind the frequent use of liminality is the concept of the creative space (Turner Citation1967), and third space (Lee et al, Citation2016). Turner proposed that spaces developed through utilizing a liminal framework can enable inclusion, communitas, diversity participation and co-creation to support new strategies and ways of thinking (Kligyte et al Citation2022). This is symbiotic with the Lego® Serious Play® methodology.

Mental health and wellbeing

The World Health Organization (2020) reports that 16% of children and young people worldwide suffer from a mental health condition. Alarmingly, half of known mental health conditions occur before the age of 14, and if not diagnosed in this window, then there is a probability that the condition will have a lifelong impact upon their well-being (NHS Citation2020). Research findings indicate the priority given to mental health for children and young people is significantly less than the attention given to the adult reporting of disability adjusted life years (DALYs) (WHO Citation2003). It is argued by Palmquist et al (Citation2017) that limited consideration has been given to understanding, or researching, the perspectives and experiences of children and young people regarding their mental health. This relative paucity of investigation is despite UNICEF’s stance that “children have the right to give their opinions freely on issues that affect them. Adults should listen and take children seriously” (UNICEF Citation1989, p. 3). Attard et al (Citation2021) highlight that the implementation of child-centered practices in health services can be problematic. This can involve complications between the decisions made by adults responsible for their care (medical and parental), versus the child’s wishes for having an equal voice. This study proposes that these complexities which face parents, staff and children can be co-creatively addressed through leisure-based activities such as Lego® Serious Play®, whilst highlighting opportunities for the development of child-centered support within their formal everyday education setting.

The impact of the covid-19 pandemic further emphasized the importance of supporting the wellbeing of children and young people (DfE, Citation2023). Hall (Citation2022) highlighted that young people felt powerless and overwhelmed living in an anxiety-induced era. Kellaway (Citation2022) highlighted that with the onset of energy crises, cost of living increases, the war in Ukraine, and global pandemics, children have experienced significant disruption in their lives. Similarly, education bodies and federations have highlighted that children were missing out on social, academic and personal milestones, leaving them feeling grief, loss, uncertainty and a lack of confidence (DfE, Citation2023). In the initial post-pandemic period, Shipway, Henderson and Inns (Citation2022) suggested that schools are an ideal location to use Lego® Serious Play® to address issues and promote positive mental health as part of the solution. They also detailed the prevalence of pupil mental health issues including increased levels of low self-esteem, depression, and feelings of anger. Globally, health systems continue struggling to cope with these demands (Shipway & Henderson, Citation2023).

In the United Kingdom (UK), where this study was based, during the 2021/22 academic year anxiousness among both primary and secondary-age pupils increased and was higher than in 2020/21 (DfE, Citation2022). Similarly, the percentage of children and young people in the UK reporting low happiness with their health had increased in recent years (The Children’s Society, Citation2022). Findings from the Department for Education’s State of the Nation 2022 research report, published in February 2023, suggested an inconsistent recovery of children and young people’s mental health and wellbeing toward pre-pandemic levels (DfE, Citation2023). This report also highlighted how the daily experiences, thoughts and feelings about school expressed by children reflected their current mental health and wellbeing, offering some avenues for positive action. Given these ongoing challenges, this study seeks to better understand mental health and the developing mind of young people aged between seven and eleven within educational settings, whilst supporting the call for further research addressing the impact of the covid-19 pandemic upon the leisure experience of children and young people (Holt & Murray, Citation2022).

Leisure and play

The phenomenon of leisure has been viewed from many perspectives, from social sciences to science, over a considerable period (Dimitrijević & Petrović Citation2018). This narrative surrounding the role of leisure in supporting well-being has been advocated by poets, philosophers, and academics (Newman et al Citation2014). The concept of leisure enhancing subjective well-being has gained traction and literary coverage underpinned by numerous theories including both self-determination theory (Ryan & Deci Citation2000) and flow experiences through leisure (Csikszentmihalyi Citation1990). For children it is essential that both formal and informal leisure opportunities are created, to realize the known benefits of leisure and to facilitate competence in adulthood (Barnett, Citation1990). There are various challenges and influencing factors to enabling these opportunities including age, type of school, number of opportunities, and influence of family and friends (Dimitrijević & Petrović Citation2018). There is also a body of evidence linking leisure to improved well-being which subsequently can impact school performance and/or behavior (Eccles et al., Citation2003; Fletcher et al., Citation2003). A common theme emerging from studies is the central role of structured leisure time, be it in school or through extracurricular activities (Mahoney & Stattin, Citation2000; Coleman & Kohn, Citation2007, p. 1) provide perspective upon the “discipline of leisure and taking play seriously’. Likewise, the interrelationship between ‘leisure and play: play and leisure, leisure as play” has been extensively considered by Stebbins (Citation2016, p. 1), drawing insight from Plato to more present-day dialogues. The value and relevance of this study is that the creative methodology used incorporates play to produce leisure-based wellbeing outcomes.

Serious play has been established as a set of activities and process which engender creativity and innovation (McCusker, Citation2020), and help to bring this creativity and vitality within play to serious matters, including mental health. Shipway and Henderson (Citation2023) place significant emphasis upon the importance of playfulness for children and young people (CYP) in times of crisis. They cited contemporary societal challenges of a world faced with pandemics, wars, energy crises, and cost of living increases. In doing so, they highlighted the opportunities for playful activities toward supporting mental health issues within educational settings. Schottelkorb et al. (Citation2015) emphasized that Lego® Serious Play® (LSP) can provide an alternative support mechanism, through the power of play to foster joy. Whilst LSP was primarily developed for use in business contexts (Peabody, Citation2015), many of the principles which underpin the methodology are supported within the educational research literature, in the context of further and higher education (McCusker, Citation2014). The LSP process facilitates free-thinking, nonjudgmental and playful interactions between participants (Jensen et al., Citation2018). Play-based learning (PBL) is playful with child-led aspects guided by adults to achieve learning objectives (Weisberg et al., Citation2013).

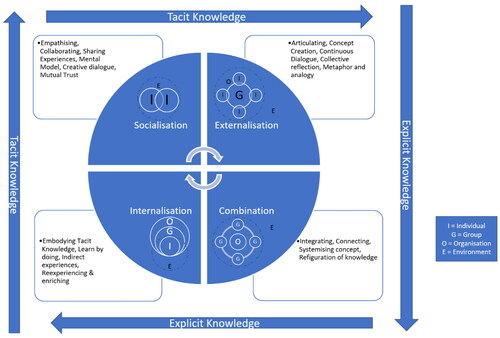

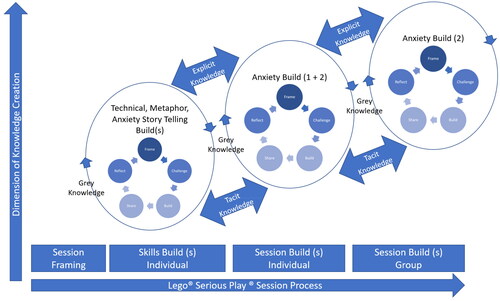

Play allows participants, like the children in this study, to explore and experience familiar problems in a new way, both unlocking and transforming tacit knowledge (Chamidy et al Citation2020). For the children it also creates safe liminal spaces in their everyday classroom environments and helps mitigate issues that might become more prevalent in a formal health setting (Attard et al Citation2021). This approach can then be applied to the knowledge creation process and knowledge conversion. This can be observed within the component parts of Socialization Externalization Combination and Internalization (SECI) theory, as illustrated in . A more person-centric approach has seen the SECI theory used outside of business organizations and crossing over into both education (Farnese et al Citation2019) and health (Morris et al Citation2022) research contexts. The SECI theory moves through four knowledge conversion phases which interact with the individual, group, organization and environment. According to Nonaka and Konno (Citation1998), the phases include (i) socialization (collaboration to encourage empathy, dialogue, and trust); (ii) externalization (articulating and sharing concepts converting tacit into explicit); (iii) combination (integrating, connecting, classifying and converting into explicit working concepts); and (iv) internalization (where learning, understanding, practice, review and embodying explicit knowledge is converted into tacit knowledge). This also complements , which also supports the conversion of tacit knowledge within preliminal thresholds.

Figure 2. Knowledge creation process: knowledge conversion SECI theory (adapted from Nonaka & Konno Citation1998; Song, Citation2008 cited in Rachmawati, Citation2017; Maras et al Citation2022).

The concept of ‘play’ in education describes a process where a child or young person can learn to make sense of the world around them (Shipway & Henderson, Citation2023), whereby meanings are ‘constructed’ through the interaction of their ideas and liminal experiences. Similarly, McCusker (Citation2020) identifies that LSP can create a play state which allows authentic voices to emerge and to be heard. Play can create opportunities for constructing and adapting stories that relate to participants’ lived experiences and personal perspectives (Hinthorne & Schneider, Citation2012). In an educational setting playful activities can help students improve communication and creativity through a liberated, unfiltered and less self-preserving expression (Jensen et al. Citation2018). Reeve (Citation2021) advocated the need for compassionate playfulness in dark times. In contemporary society faced with pandemics, wars, energy crises, and cost of living increases, this study will critique the important role of playfulness in times of crisis, and the potential contribution of a leisure-based activity, Lego®, toward supporting mental health within educational settings (Shipway, Henderson & Inns, Citation2022).

Shipway and Henderson (Citation2023) illustrate that the creative methodology of Lego® Serious Play® is based on four central pillars (i) the use of metaphors; (ii) underpinned by the concept of play, (iii) theory of flow; and (iv) constructivism. Lego® Serious Play® applies these concepts to support learning through exploration and metaphorical explanations of realities. Lego® Serious Play® uses visual, auditory, kinesthetic learning (Blair Citation2021) so it is inclusive within the domain of learning styles faced in an education context. This also aligns with the conversational framework (Laurillard, Citation2013; Henderson & Shipway, Citation2023). Using this creative methodology enables children to unlock tacit knowledge and to convert this into an explicit concept, and thus provide leisure-based solutions for their own well-being during their school transition process. The contribution of the approach adopted in this study is that the Lego® Serious Play® methodology facilitates reflection points, which are not incorporated within the SECI theory, and in doing so allows grey knowledge to be integrated in the children’s mind, through both reflection and further practice (Li et al Citation2018).

Methodology

Using Lego ® as a creative methodology

This research study adopts a creative methodology, bringing together Lego® Serious Play® (LSP) and mental health and wellbeing outcomes for children, within an educational setting (Shipway & Henderson, Citation2023). Wengel et al (Citation2021) suggest that traditional qualitative methods, including interviews and focus groups, do not capture the co-construction of the participants’ realities or address the impact of wider social dynamics. Similarly, McCusker (Citation2020) argues that traditional data collection tools typically see interactions as merely facilitating talk-based content rather than collaborations for learning. This study suggests that using a creative data collection methodology such as Lego® Serious Play® (LSP) allows tacit ‘hidden’ experiences and knowledge to be communicated, stimulates new awareness of ‘reality’, and provides deeper metaphorical meanings and depth of participants’ lived experiences which are not captured by alternative methods (Wengel et al., Citation2016; Henderson & Shipway, Citation2022). This study aims to both advocate and illustrate ‘real-world’ opportunities for building capability and scalability through methodological creativity.

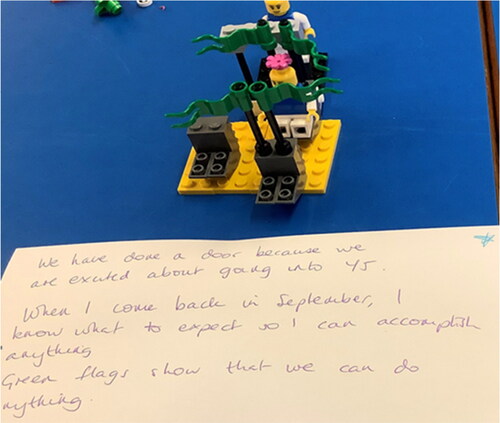

A Lego® Serious Play® (LSP) session will generate a nonhierarchical and collaborative environment where children interact playfully, building models in response to challenges set by the facilitator. When using the LSP technique, the methodological creativity is not the Lego® per se but using Lego® as the tool to deliver bottom-up mental health and well-being outcomes, which are pupil led. Creatively, the use of Lego® Serious Play® (LSP) will also allow mental health to be openly discussed by building abstract models. These abstract models, in 3D format, help to facilitate the imagination and visualization of thoughts and ideas and contribute innovative solutions to challenges presented by a session facilitator. For example, illustrates a model that considers personalized learning for young people (Henderson & Shipway, Citation2022). If we delineate this model build, the Lego® minifigure portrays the young person and the purple brick, as a head, represents neurodiversity. At the base of the model, the green base plate represents the learning environment, the lilac brick pictures the physical environment, and the green brick illustrates emotional environment. Similarly, the red brick portrays parts of the social environment, the light blue brick depicts aspects of culture, the royal blue brick characterizes pedagogy, the beige brick exhibits technology, and the purple brick represents the personalized learning model. Finally, the green leaves portray the teacher, and the purple flower depicts creativity (Shipway & Henderson, Citation2023).

Research sample and data collection

Data was collected in two stages during June and July 2022 in a Southwest of England Junior school. The junior school is a UK state school for boys and girls, with approximately 700 pupils aged between seven and eleven. Participating pupils came from all four age groups (year groups 3-6) which were the year groups directly affected by the annual school transition process, whereby pupils move either between year groups, or to new schools. The first stage of pupil sessions took place on 27th and 28th June and this was then repeated in a second session with the same students three weeks later, on 18th and 19th July, following the annual school ‘transfer day’, held in early July (Shipway, Henderson & Inns, Citation2022).

Recruitment and promotion of the workshops was led by the junior school assistant head teacher and year group teachers, with all the required information and consent documentation sent home and signed by parents. This documentation included participant agreement forms and information sheets for both parents and teachers, with modified information sheets and assent form distributed to each pupil to help illustrate the aims of the workshop (Shipway et al., Citation2022). Both authors led and delivered the workshops, with support from both the assistant head teacher and several teaching assistants (TAs) who were available to help guide and support pupils. A pre-briefing session was held for all non- Lego® accredited participants to ensure they were confident and aware of the theoretical basis for the Lego® Serious Play® approach. Their commitment to the process was an essential requirement. This procedure was different for the children, who had a clearer focus upon the play component of the workshop from the outset (Henderson & Shipway, Citation2023).

During each 55-minute session, pupils were asked to complete four tasks which aligned with the Lego® Serious Play® (LSP) methodology. During both stages of data collection, sixty-four pupils took part with four class groups of sixteen students addressing ‘transition’ related issues linked to their anxieties surrounding movement between either schools or year groups (Henderson & Shipway, Citation2022). Stage 2 of the data collection, post ‘transfer day’, allowed pupils to repeat certain Lego® tasks and to ascertain whether the school or year group changes made, based on the outcomes of the first stage of pupil sessions prior to the transfer day, had reduced levels of anxiousness toward the broader transition process (Shipway & Henderson, Citation2023). The children were able to reflect on their thoughts, emotions, perspectives and feelings toward the broader school transition process. The pupils were all given pseudonyms to protect their anonymity.

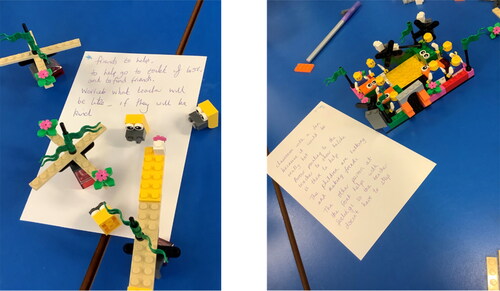

Completing the sessions within the school, in a natural and familiar setting, allowed for informal observations of actions and interactions with the Lego®. The Lego® Serious Play® methodology moves through repeated phases, whereby the facilitator will frame the session and/or build (Henderson & Shipway, Citation2022), and then set the children a challenge, which is termed a ‘build’ question. For example, the children might be asked to ‘build a model of what worries you about changing classes at school’, or to ‘build a model of something that would make changing classes at school better’. The children build their response to the challenge, thinking with their hands (Shipway & Henderson, Citation2023), and understanding that there are no ‘wrong answers’. The children are then invited to share their build both verbally and by writing it down on a flash card (see ). The children are then asked reflection questions about the built model. The Lego® Serious Play® process is detailed in , illustrating the stages of the session, and the dimension of knowledge that is created. This shows that there is a cycle within the process of the Lego® Serious Play® builds that compliments the spiral of knowledge transfer between the stages. The process used in this study advances knowledge from the SECI model approach, as the reflection phase of the process can further support the conversion of knowledge into outcomes, and then the cycle can be repeated.

Figure 4. Spiral knowledge creation through Lego® Serious play® (adapted from Li et al., Citation2022; Henderson & Shipway, Citation2023).

The first workshop session was split into four component parts, comprising (1) Technical Build: build a model of a free-standing Tower [3 min]; (2) Brick Metaphor: build something that reflects your ‘favourite thing’, which might include places, food or pets [1 min]; (3) Story Telling: build a model of what worries you about changing classes at school [5mins]; and (4) Session Build: build a model of something that would make changing classes or school better [5mins]. In the first session the children completed all component parts (1,2,3 and 4). In the second session, after the ‘transfer day’, the children only repeated component two, the Brick Metaphor, before a fifth component was introduced. This fifth element was an adaptation of the original fourth Session Build but had both an individual and group component. This fifth Session Build (Individual and Group) was to build a model of the things that would make your ‘perfect first day back at school after the summer holidays’ [5mins] (Shipway & Henderson, Citation2023). The key differentiating activity in the second session was the collaborative group build.

Each child was given a similar pack of Windows Explorer Lego®, as displayed in . As data was collected shortly after the covid-19 pandemic, the use of prepackaged bags of Lego® Window Explorer kits were considered the most hygienic option (Henderson & Shipway, Citation2022). The first two ‘builds’ were effectively ‘warm up exercises’ for the children, to ensure they were both confident and comfortable with the activities. The final two builds investigated the main aim of the study, linked to pupil anxieties surrounding the school transition process.

Qualitative content analysis techniques and procedures were then applied. Thematic analysis has been described as well suited for qualitative research within the field of health and wellbeing (Braun & Clarke, Citation2014). Lego® Serious Play® as a creative methodology entails similar critiques and limitations of a constructivist paradigm, including lack of generalizability and replicability of the data (Wengel et al., Citation2021). However, the structured process of each session allowed pupils to test ideas and perspectives without fear of saying something wrong, and in a relatively small sample it enabled common themes to emerge (Henderson & Shipway, Citation2022). In this instance, codes were driven by the data, extracted from both the models built and the written comments on blank flash cards. The use of blank flash cards, where pupils could further articulate their thoughts, meanings, values and perceptions were particularly helpful for supporting analysis of the data and adding additional detail on the meaning of the bricks and the models which were constructed (Shipway & Henderson, Citation2023). The cards were collected after the sessions and thematically analyzed.

The role of the two authors was to co-create, whilst minimizing bias from their own experiences of working within the education sector. Following several rounds of comments, revisions and discussions between the authors and the assistant head teacher at the school to verify they were an accurate reflection of the views and perspectives of the children, a set of reconciled codes, key themes and sub themes were finalized (Jones, Citation2022; Holloway & Galvin, Citation2016).

Results and discussion: Lego®, liminality, leisure and the school transition process for children and young people

Four key overarching themes emerged from the data. During the first cycle of sessions, these themes were extracted from analysis of both the constructed Lego® models and the written comments on the flash cards provided (). The key themes for managing the school transition process, termed the 4P’s and previously documented in the study by Shipway and Henderson (Citation2023), focused upon (i) Places (negotiating everyday spaces and places within a school setting); (ii) Pathways (navigating complexities of the transition process); (iii) Programming (pupil concerns about school curriculum and activities); and (iv) People (centrality and importance of peer friendships and teachers). In their study, also embedded within the leisure context, Shipway and Henderson utilized their 4P’s framework to focus on (i) exploring underlying child transition worries; (ii) opportunities to better manage the transition process for children, and (iii) short term tactics and strategies to optimize the transition process. The findings below will further develop some of these themes using the concept of liminality to provide a core framework for understanding the processes and practices through which Lego® Serious Play® can positively influence the student experience and wellbeing of children.

The four underlying 4P’s themes, identified by Shipway and Henderson (Citation2023) were mapped against the stages in van Gennep’s schematic as introduced in (adapted from Söderlund & Borg, Citation2018). They were then further modified, as exhibited in , to reflect the combination of both the 4P’s key themes and the rites of passage sequence. It is worth noting that due to the school ‘transfer day’ there is a simulation in the passage which then occurs over the summer holiday. Delineating how the four P’s themes support this process from the Lego® Serious Play® sessions was essential as it enabled a feed forward process, where children were directed toward their next steps, tasks or activities, to take place prior to the actual rites of passage occurring. Rites of passage(s) are not linear processes, and in the context of the school transition process, they are cyclical. Each iteration will intrinsically support resilience, using Shipway and Henderson’s 4P’s framework to help develop an understanding of the modes and features of the thresholds. A better understanding of some aspects of the 4P’s framework has potential to contribute toward part of a wider educational ‘tool kit’ to help support and develop children and young people. This is likely achievable, and the results start to highlight this, because tacit knowledge as an experience and skill promotes the children’s understanding, which can then help support the creation of solutions to help resolve issues causing them anxiety (Ibidunni et al., Citation2018).

The children’s storyboard of ‘builds’ on their worries and solutions, as illustrated in and , provided a basis for the coding and classification of prospective solutions suggested by the children. Additionally, the children were able to convert, and articulate mental images of what additional future leisure activities could be introduced both inside and outside of the everyday school environment to help improve their wellbeing, through the construction of Lego® models. Using flash card was an invaluable and supportive tool to ensure that the artifact of the model and the associated narrative were accurate (see ). Using this process for both the individual and group builds supported the coding and analysis of the data (Henderson & Shipway, Citation2022), and was illustrative of a creative approach to both data collection and the subsequent analysis.

Figure 8. Lego®, Liminal experiences, and rites of passage through the school transition process (adapted from Söderlund & Borg, Citation2018; Shipway & Henderson Citation2023).

The participants in this study experienced a transformation of identity within their daily school life, due to the process of liminality emerging from the Lego® sessions (Turner, Citation1982). This enabled the pupils to become more deeply and intensively involved in the Lego® ‘builds’, within the designated leisure space. The liminal characteristics, as previously explored in leisure spaces by Lee et al., (Citation2016) were also evident during these sessions, as the children were given space to become part of a different world, away from their ordinary, everyday, traditional, structured school routine. Three staff members commented that crucially the ‘voice’ of the children was heard, and all six teaching assistants were in unanimous agreement that the sessions had provided ideas for better facilitating an effective and smooth transitions process. The high levels of engagement with Lego®, as a leisure-based activity allowed children to gather around the shared core values associated with Lego®. Thus, the shared leisure experience increased the intensity of links amongst the pupils and affirmed their enthusiasm and involvement in relation to Lego® Serious Play®. Lisa (TA1) commented ‘they enjoy Lego. Lego is a game, so therefore positive and relaxed connotations are assumed, and they have an “I can do” mentality, as they have used Lego before’.

The second series of sessions enabled the students to reflect on their experiences of the school ‘transfer day’, in the context of a simulated rite of passage. This helped prepare them for the start of the new forthcoming academic year, in September. It also enabled further utilization of the spiral knowledge creation process, as advocated in , and the conversion of grey knowledge to help support the children to formalize their next steps. The pupils were able to do this having had a period of internalization, as described in , through following the knowledge creation and conversion process using a SECI theory approach. As illustrated in , this internalization process was evidenced in the timing of session one, the transition day, and during session two.

The slight change in the format of the second session enabled the children to collaborate, using their own models and bricks, in a ‘group build’ activity which took place on their classroom tables. The theme of the group ‘build’ was to plan ‘their perfect first day back at school in September’. As illustrated in , the findings show a far more positive outlook toward the new forthcoming academic year. The common themes in the builds were the acceptance of ‘making new friends’ and the importance of sign posting for ‘help’ and assistance, be that through friends, family, guardians, class teacher or other school staff members. The content analysis allowed the research team to provide direct quotes from the notecards as evidence to support the key themes. Sofia (TA4) observed:

Figure 9. Examples of a children’s group builds with flash card Story illustrating their ‘perfect first day back at school in September’.

It was a good way of showing the children they were not alone in their worries. It allowed the children to think creatively about what they were worried about, and therefore what could be done to help them. This, in turn, helped me to plan the transition day for those specific children in my class, and others, who may well have felt the same.

In a school setting and using a child-centered approach the SECI model, detailed in , provided a useful insight into the knowledge creation process of uncovering children’s anxieties surrounding the annual school transition process (Söderlund & Borg, Citation2018). One caveat is that the socialization stage during session 2 occurred in a group format, and the children’s views were shaped by both the internal school setting and external factors outside of the school environment. The stages of both externalization and combination were consistent within an educational setting, although the combination stage might vary for pupils who transition to a new school, rather than onto a new year group. In that instance, the role of the school would not be the center of combination but involve separate communication with their new school, as part of the child’s rite of passage (Van Gennep, Citation1960). The internalization stage would be reinforced during both the ‘transfer day’ and during the second session. Opportunities for offering the children additional leisure activities, both inside and outside of school, to support mental health and wellbeing could then also be incorporated within the socialization stage.

The spiral knowledge creation model (adapted from Li et al., Citation2022; Henderson & Shipway, Citation2023), provides a useful platform to understand the various dimensions of knowledge and the spiral of knowledge transfer process (be that tacit, explicit, or grey) through the cycle of the Lego® Serious Play®. The children were able to both understand the LSP process and then articulate their own solutions. In doing so, this helped build their resilience, whilst also solving problems, as an embedded part of their liminal rites of passage (Söderlund & Borg, Citation2018). As highlighted above, from a leisure perspective, the school was then better placed to offer pupils additional school based and external leisure activities, to help support pupil wellbeing. An example noted by the lead teacher was ‘going outside’, which was also mentioned by many children. A break from the classroom was a key request from the children. It was established that this could be as straight forward as practising the walk to assembly or to the fire drill lining-up point to something more substantial such as a physical activity or wellbeing event. This study is the first to incorporate a group Lego® model build for this age group (seven to eleven). This highlighted how the use of a creative methodology such as Lego® Serious Play® can foster collaborative thinking, problem solving, and deliver tangible outcomes for better supporting child wellbeing within a learning environment of shared understanding and to foster a degree of pupil excitement (Shipway, Henderson and Inns, Citation2022).

Conclusion

The findings highlight that the Lego® Serious Play® methodology uses liminality to enable a change in the way play can be utilized in educational settings. This is not always related to learning outcomes or free play and enables children and young people to drive a bottom-up approach, one led by the children rather than the teachers, to solving issues that cause them anxiety. This is fundamentally important, as early interventions can help reduce the probability of these issues developing into more substantial and broader mental health challenges for schools, health service providers and broader education stakeholders.

One limitation of the study is the focus upon seven to eleven-year-old children. There is scope for future studies linked to adolescents in the age range of ten to twenty-four, and in other ‘transition’ contexts which both diversify the age ranges investigated and expand upon transition scenarios and environments. This might include scrutiny of adolescent transition into college/university settings, their entry into the workplace from the school environment, or amongst younger five- or six-year-old ‘primary’ school children to better understand how they navigate, and transition, throughout the full spectrum of their education (Shipway & Henderson, Citation2023).

The findings of this study contribute to knowledge in the following four areas. Firstly, they highlight the impact of using Lego® Serious Play® as a creative methodology that can elicit child centered and leisure-based interventions to help support the wellbeing of children in educational settings. The LSP process delivered child centered outcomes which explored how best to manage child anxieties toward their school transition process. The richness of delivering two sessions, one either side of the annual ‘transfer day’, enabled structured leisure activities to be integrated into both the transfer day and preparations for the new academic year. It also allowed social connections to emerge through new peer group formations and establishing closer connections between the pupils and their new teacher and teaching assistants. This was evidenced in the Lego® models built in the second session.

Secondly, the Lego® Serious Play® methodology produces a cycle of learning and a spiral effect in relation to new knowledge creation. Both pupil and teacher were able to move through various transitions using a bottom-up approach. As the sessions developed, the teachers were able to adopt more of a ‘backseat’ role with an emphasis more upon observing the children rather than formally instructing and directing them, and often providing teachers with precious time and space. In doing so, teachers and staff were able to develop suitable support strategies for anxious pupils. This differentiates from the previous use of SECI theory by both Nonaka and Konno (Citation1998) and Li et al. (Citation2022), as it replicates the five-phase cycle used in the LSP approach (as detailed in the methodology) to enable grey knowledge to be converted during the spiral stage. Having two sessions allowed for a period of reflection and for adjustments to be embedded into the second session.

Thirdly, using a formal education setting to address mental health issues and concerns removes some of the challenges faced when exploring anxieties within a medical setting, and any subsequent conflict this might cause parents, medics or children. This allows structured leisure outcomes to be achieved, via the 4P’s approach, advocated by Shipway and Henderson (Citation2023). Effectively, barriers to accessing leisure outside of the school environment are removed, and it allows the children’s voice to be clearly heard, aligned with the UNICEF goals on child rights (UNICEF, Citation1989). Lego® Serious Play® can provide a vehicle to support reductions in long term mental health issues as both a creative method, and to help identifying child-led strategies for leisure and wellbeing. Fourthly, within an educational setting, the findings of this study enhance the understanding of liminality and thresholds. It supports the use of a ‘transfer day’ to simulate the process that enables children to move through the various stages of the transition process in preparation for the start of a new academic year, using a leisure-based activity, Lego® as the underpinning mechanism.

There are numerous opportunities to further use a creative methodology like Lego® Serious Play®. These include (i) introduction into educational settings across a variety of age ranges (seven to sixteen) as a model of best practice; (ii) measuring the impact of leisure interventions on wellbeing and anxiety using the Hamilton Anxiety Scale, or similar scales, amongst children at both the pre and post intervention stages; (iii) further developing the SECI model to support both implementation and integration with Lego® Serious Play® in an education and health context, for a child-centered wellbeing model; and (iv) considering piloting the LSP methodology for young people in the higher 16+ and 18+ age ranges, in conjunction with stakeholders and partners across mental health and wellbeing, education and leisure sectors.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Atkinson, S., & Robson, M. (2012). Arts and health as a practice of liminality: Managing the spaces of transformation for social and emotional wellbeing with primary school children. Health & Place, 18(6), 1348–1355. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthplace.2012.06.017

- Attard, C., Elliot, M., Grech, P., & McCormack, B. (2021). Adopting the Concept of ‘Ba'and the ‘SECI'Model in Developing Person-Centered Practices in Child and Adolescent Mental Health Services. Frontiers in Rehabilitation Sciences, 2, 744146. PMID: 36188764; PMCID: PMC9397818. https://doi.org/10.3389/fresc.2021.744146

- Barnett, L. A. (1990). Developmental benefits of play for children. Journal of Leisure Research, 22(2), 138–153. https://doi.org/10.1080/00222216.1990.11969821

- Blair, S. (2021). How to facilitate Lego serious play method online: New facilitation techniques. ProMeet.

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2014). What can "thematic analysis" offer health and wellbeing researchers? International Journal of Qualitative Studies on Health and Well-Being, 9(1), 26152. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4201665/ https://doi.org/10.3402/qhw.v9.26152

- Chamidy, T., Degeng, I., & Ulfa, S. (2020). The effect of problem based learning and tacit knowledge on problem-solving skills of students in computer network practice course. Journal for the Education of Gifted Young Scientists, 8(2), 691–700. https://doi.org/10.17478/jegys.650400

- Coleman, S., & Kohn, T. (2007). The discipline of leisure: Taking play seriously. The Discipline of Leisure: Embodying Cultures of ‘Recreation (pp. 1–22).

- Collins, G. (2001). So the little guys have more room to show their stuff. The New York Times. (pp. B1–B1)

- Csikszentmihalyi, M. (1990). Flow: The psychology of optimal experience. HarperPerennial.

- Department for Education (DfE). (2022). Parent, Pupil and Learner Panel—June wave. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/1122899/PPLP_report_rw4_june.pdf

- Department for Education (DfE). (2023). State of the nation 2022: Children and young people’s wellbeing. DfE.

- Dimitrijević, D., & Petrović, J. (2018). Leisure time of school children – The view on structure and organization. Годишњак ЗА Педагогију, 2, 7–18. https://doi.org/10.46630/gped.2.2018.01

- Donetto, S., Jones, F., Clarke, D. J., Cloud, G. C., Gombert-Waldron, K., Harris, R., Macdonald, A., McKevitt, C., & Robert, G. (2021). Exploring liminality in the co-design of rehabilitation environments: The case of one acute stroke unit. Health & Place, 72, 102695. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthplace.2021.102695

- Eccles, J. S., Barber, B. L., Stone, M., & Hunt, J. (2003). Extracurricular activities and adolescent development. Journal of Social Issues, 59(4), 865–889. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.0022-4537.2003.00095.x

- Farnese, M. L., Barbieri, B., Chirumbolo, A., & Patriotta, G. (2019). Managing knowledge in organizations: A Nonaka’s SECI model operationalization. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 2730. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.02730

- Fletcher, A. C., Nickerson, P. F., & Wright, K. L. (2003). Structured leisure activities in middle childhood: Links to well-being. Journal of Community Psychology, 31(6), 641–659. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcop.10075

- Hall, R. (2022). Pandemic still affecting UK students’ mental health, says helpline. https://www.theguardian.com/education/2022/nov/14/pandemic-still-affecting-uk-students-mental-health-says-helpline-covid

- Henderson, H., & Shipway, R. (2022, July 12–14). Leisure, LEGO® Serious Play (LSP), and Mental Health and Wellbeing. Paper Presented at Leisure Studies Association (LSA) Annual Conference, Falmouth, UK.

- Henderson, H., & Shipway, R. (2023). Speaking bricks: Lego, leisure, liminality and well-being. In M. Polkinghorne & G. Roushan (Eds.), Fusion Learning Conference 2023.

- Hinthorne, L. L., & Schneider, K. (2012). Playing with purpose: Using serious play to enhance participatory development communication. International Journal of Communication, 6, 2801–2824.

- Hockey, J. (2002). The importance of being intuitive: Arnold Van Gennep’s The Rites of Passage. Mortality, 7(2), 210–217. https://doi.org/10.1080/135762702317447768

- Holloway, I., & Galvin, K. (2016). Qualitative research in nursing and healthcare. John Wiley & Sons.

- Holt, L., & Murray, L. (2022). Children and Covid 19 in the UK. Children’s Geographies, 20(4), 487–494. https://doi.org/10.1080/14733285.2021.1921699

- Ibidunni, A. S., Ibidunni, O. M., Oke, A. O., Ayeni, A. W., & Olokundun, A. M. (2018). Examining the relationship between tacit knowledge of individuals and customer satisfaction. Academy of Entrepreneurship Journal, 24, S0144686X16001136. https://doi.org/10.1017/0144686X16001136

- Jensen, C. N., Seager, T. P., & Cook-Davis, A. (2018). LEGO® SERIOUS PLAY® in multidisciplinary student teams. International Journal of Management and Applied Research, 5(4), 264–280. https://doi.org/10.18646/2056.54.18-020

- Jones, I. (2022). Research methods for sports studies (4th ed.). Routledge.

- Keefer, J. M. (2015). Experiencing doctoral liminality as a conceptual threshold and how supervisors can use it. Innovations in Education and Teaching International, 52(1), 17–28. https://doi.org/10.1080/14703297.2014.981839

- Kellaway, L. (2022). The anxious generation—what’s bothering Britain’s schoolchildren? https://www.ft.com/content/1ae1d60f-b0c6-405e-9080-89f0bc649891

- Kligyte, G., Buck, A., Le Hunte, B., Ulis, S., McGregor, A., & Wilson, B. (2022). Re-imagining transdisciplinary education work through liminality: Creative third space in liminal times. Australian Educational Researcher, 49(3), 617–634. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13384-022-00519-2

- Land, R., Cousin, G., Meyer, J. H. F., & Davies, P. (2005). Threshold concepts and troublesome knowledge (3): Implications for course design and evaluation. In C. Rust (Ed.), Improving Student Learning - diversity and inclusivity, Proceedings of the 12th Improving Student Learning Conference (pp. 53–64). Oxford Centre for Staff and Learning Development (OCSLD). http://www.brookes.ac.uk/services/ocsld/isl/isl2004/abstracts/conceptual_papers/ISL04-pp53-64-Land-et-al.pdf

- Land, R., Meyer, J. H. F., & Baillie, C. (2010). Editors’ preface: Threshold concepts and transformational learning. In R. Land, J. H. F. Meyer, & C. Baillie (Eds.), Threshold concepts and transformational learning (pp. ix–xlii). Sense Publishers.

- Laurillard, D. (2013). Rethinking university teaching: A conversational framework for the effective use of learning technologies. Routledge.

- Lee, I. S., Brown, G., King, K., & Shipway, R. (2016). Social identity in serious sport event space. Event Management, 20(4), 491–499. https://doi.org/10.3727/152599516X14745497664352

- Li, M., Liu, H., & Zhou, J. (2018). G-SECI model-based knowledge creation for CoPS innovation: The role of grey knowledge. Journal of Knowledge Management, 22(4), 887–911. https://doi.org/10.1108/JKM-10-2016-0458

- Li, W., Zhao, Z., Chen, D., Peng, Y., & Lu, Z. (2022). Prevalence and associated factors of depression and anxiety symptoms among college students: A systematic review and meta‐analysis. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 63(11), 1222–1230. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpp.13606

- Mahoney, J. L., & Stattin, H. (2000). Leisure activities and adolescent antisocial behavior: The role of structure and social context. Journal of Adolescence, 23(2), 113–127. https://doi.org/10.1006/jado.2000.0302

- Maras, M.-H., Arsovska, J., Wandt, A. S., Knieps, M., & Logie, K. (2022). The SECI model and darknet markets: Knowledge creation in criminal organizations and communities of practice. European Journal of Criminology, https://doi.org/10.1177/14773708221115167

- Martin-McDonald, K., & Biernoff, D. (2002). Initiation into a dialysis-dependent life: An examination of rites of passage. Nephrology Nursing Journal: Journal of the American Nephrology Nurses’ Association, 29(4), 347–352.

- McCusker, S. (2014). Lego®, serious play TM: Thinking about teaching and learning. International Journal of Knowledge, Innovation and Entrepreneurship, 2(1), 27–37.

- McCusker, S. (2020). Everybody’s monkey is important: LEGO® Serious Play® as a methodology for enabling equality of voice within diverse groups. International Journal of Research & Method in Education, 43(2), 146–162. https://doi.org/10.1080/1743727X.2019.1621831

- McKenzie, H. (2004). Personal and collective fears of death: A complex intersection for cancer survivors. In A. Fagan (Ed,), Making sense of death and dying (pp. 107–124). Rodopi.

- Meyer, J., & Land, R. (2005). Overcoming barriers to student understanding. Taylor & Francis.

- Morris, J. H., Kayes, N., & McCormack, B. (2022). Person-centred rehabilitation–theory, practice, and research. Frontiers in Rehabilitation Sciences, 3, 980314. https://doi.org/10.3389/fresc.2022.980314

- Newman, D. B., Tay, L., & Diener, E. (2014). Leisure and subjective well-being: A model of psychological mechanisms as mediating factors. Journal of Happiness Studies, 15(3), 555–578. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-013-9435-x

- NHS. (2020). Mental Health of Children and Young People in England, 2020. https://files.digital.nhs.uk/AF/AECD6B/mhcyp_2020_rep_v2.pdf

- Nonaka, I., & Konno, N. (1998). The concept of Ba: Building a foundation for knowledge creation. California Management Review, 40(3), 40–54.https://doi.org/10.2307/41165942

- Palmquist, L., Patterson, S., O’Donovan, A., & Bradley, G. (2017). Protocol: A grounded theory of ‘recovery’ - perspectives of adolescent users of mental health services. BMJ Open, 7(7), e015161. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2016-015161

- Peabody, M. A. (2015). Building with purpose: Using LEGO SERIOUS PLAY in play therapy supervision. International Journal of Play Therapy, 24(1), 30–40. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0038607

- Rachmawati, A. W. (2017). Socialization model of tacit-tacit transfer knowledge through appreciative inquiry approach. International Journal of Management, Entrepreneurship, Social Science and Humanities, 1(1), 7–14. https://doi.org/10.31098/ijmesh.v1i1.4

- Reeve, J. (2021). Compassionate play: Why playful teaching is a prescription for good mental health (for you and your students). Journal of Play in Adulthood, 3(2), 6–23.

- Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2000). Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. The American Psychologist, 55(1), 68–78. https://doi.org/10.1037//0003-066x.55.1.68

- Schottelkorb, A. A., Swan, K. L., Jahn, L., Haas, S., & Hacker, J. (2015). Effectiveness of play therapy on problematic behaviors of preschool children with somatization. Journal of Child and Adolescent Counseling, 1(1), 3–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/23727810.2015.1015905

- Shipway, R., & Henderson, H. (2023). Everything is awesome! Lego® Serious Play®(LSP) and the interaction between leisure, education, mental health and wellbeing. Leisure Studies. https://doi.org/10.1080/02614367.2023.2210784

- Shipway, R., Henderson, H., & Inns, H. (2022). Exploring the use of Lego to support junior school mental health and wellbeing initiatives. Coastal Learning Partnership: Dorset.

- Söderlund, J., & Borg, E. (2018). Liminality in management and organization studies: Process, position and place. International Journal of Management Reviews, 20(4), 880–902. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijmr.12168

- Song, J. H. (2008). The effects of learning organization culture on the practices of human knowledge‐creation: An empirical research study in Korea. International Journal of Training and Development, 12(4), 265–281. https://doi.org/10.31098/ijmesh.v1i1.4

- Stebbins, R. A. (2016). The interrelationship of leisure and play: Play as leisure, leisure as play. Springer.

- Tan, C. S., Tan, S. A., Mohd Hashim, I. H., Lee, M. N., Ong, A. W. H., & Yaacob, S. N. B. (2019). Problem-solving ability and stress mediate the relationship between creativity and happiness. Creativity Research Journal, 31(1), 15–25. https://doi.org/10.1080/10400419.2019.1568155

- The Children’s Society. (2022). The Good Childhood Report 2022. https://www.childrenssociety.org.uk/information/professionals/resources/good-childhood-report-2022

- Turner, V. (1967). Betwixt and between: The liminal period in rites de passage. In V. Turner (Ed.), The forest of symbols: Aspects of Ndembu ritual. Cornell University Press.

- Turner, V. (1969). The ritual process: Structure and anti-structure. Aldine.

- Turner, V. (1982). Celebration: Studies in festivity and ritual. Smithsonian Institution Press.

- UNICEF. (1989). Conventions on the rights of the child. https://www.unicef.org/child-rights-convention/convention-text-childrens-version

- Van Gennep, A. (1960). The rites of passage (M. B. Vizedom & G. L. Caffee, Trans.). University of Chicago Press. (Vol. 11, pp. 94–95).

- Weisberg, D. S., Hirsh-Pasek, K., & Golinkoff, R. M. (2013). Guided play: Where curricular goals meet a playful pedagogy. Mind, Brain, and Education, 7(2), 104–112. https://doi.org/10.1111/mbe.12015

- Wengel, Y., McIntosh, A. J., & Cockburn-Wootten, C. (2016). Constructing tourism realities through LEGO® SERIOUS PLAY®. Annals of Tourism Research, 56(C), 161–163. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2015.11.012

- Wengel, Y., McIntosh, A., & Cockburn-Wootten, C. (2021). A critical consideration of LEGO® SERIOUS PLAY® methodology for tourism studies. Tourism Geographies, 23(1–2), 162–184. https://doi.org/10.1080/14616688.2019.1611910

- WHO. (2003). Caring for children and adolescents with mental disorders: Setting WHO directions. https://www.who.int/mental_health/media/en/785.pdf?ua=1

- WHO. (2020). Adolescent Mental Health. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/adolescent-mental-health

- Ybema, S., Beech, N., & Ellis, N. (2011). Transitional and perpetual liminality: An identity practice perspective. Anthropology Southern Africa, 34(1–2), 21–29. https://doi.org/10.1080/23323256.2011.11500005