?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

We investigate firms’ disclosures related to environmental liabilities (EL), how these vary with media exposure, and whether they have information content. Using a sample of European-listed firms reporting under IFRS from 2005 to 2016, we observe diversity in disclosure practices across industries and regions. Although there is an increasing disclosure trend, the level of disclosure of key inputs used to estimate EL (i.e. discount rates and horizons) remains low, with only 35% of firm-years with material EL containing disclosures of both inputs. Furthermore, we test and find that firms facing more media exposure related to environmental matters provide disclosures that are more specific and are more likely to disclose discount rates. Finally, we show that EL disclosure specificity is associated with lower bid-ask spreads following the filing of the annual report and reduced analyst forecast error and dispersion, suggesting specific disclosure reduces information asymmetry.

1. Introduction

Firms involved in extractive activities and those operating in the utilities industry need to recognise liabilities related to future clean-up and environmental rehabilitation following site closures (henceforth referred to as environmental liabilities, EL). Examples include such activities as removing toxic materials from the ground, decommissioning mines and nuclear power plants, and plugging and abandoning oil wells at the end of their useful lives. Because these activities often take place far into the future, estimations of the liabilities are subject to significant uncertainty with respect to future technological developments and key inputs such as discount rates and horizons (i.e. the timing of future cash outflows). Due to the potentially negative economic and environmental externalities associated with EL and the inherent uncertainty involved in estimating the liabilities, firms are reluctant to provide information about EL and treat disclosure as a strategic choice (Abdo et al., Citation2018; Michelon et al., Citation2020; Schneider et al., Citation2017). By resorting to “box-ticking”, firms ostensibly comply with the letter of the standard, without providing decision-useful disclosure. Since there is no specific claimant for this type of liability (as in the case of a traditional bank loan), there is little explicit demand for disclosure. However, because the cost of clean-up is potentially material and will have to be covered by shareholders and other stakeholders, users of financial reports benefit from high-quality information about EL.

In a European context, International Accounting Standards 37 Provisions, Contingent Liabilities and Contingent Assets (IAS 37) and International Financial Reporting Interpretations Committee 1 Changes in Existing Decommissioning, Restoration and Similar Liabilities (IFRIC 1) provide guidance on the accounting treatment of decommissioning and dismantling costs. However, IAS 37 has been criticised as being difficult to interpret with respect to both disclosure and recognition criteria, resulting in diverse reporting practices.Footnote1 The main criticism against the standard is its lack of clarity concerning which inputs firms should use to determine the present value of liabilities (IASB, Citation2016, Citation2019a, Citation2019b; Michelon et al., Citation2020).Footnote2 This problem is compounded by lacking disclosure regarding the basis for estimations. For example, the audit- and consultancy firm KPMG examines the Oil and Gas industry and finds that discount rates are not disclosed by a majority of firms, and that even when rates are disclosed, underlying assumptions are many times not, which prevents meaningful cross-sectional comparisons (KPMG, Citation2008). In another report, Cap Gemini (Citation2015) finds that firms do not adequately explain the methods used for estimating the decommissioning costs in their annual reports, and rely only on the estimates of their own experts.Footnote3 Recent research also documents diversity in terms of disclosure quantity and preciseness (Abdo et al., Citation2018; Gray et al., Citation2019; Schneider et al., Citation2017), with, for example, discount rate levels being treated as a discretionary accounting choice (Michelon et al., Citation2020). These findings are partly attributed to IAS 37 containing little explicit guidance, and that managers perceive information not explicitly required as optional.

Given discretionary disclosure behaviour, we argue that the quality of EL disclosures is associated with external pressure to disclose. Specifically, we investigate whether media exposure amplifies environmental concerns and makes targeted firms more likely to provide detailed EL disclosures. Prior research shows that media plays an important monitoring role by exerting pressure on firms concerned with their reputation and raising the expected cost of non-disclosure (Brown & Deegan, Citation1998; Capriotti, Citation2009). Moreover, we investigate whether investors perceive disclosures to have information content. Theories on information asymmetry suggest that more disclosure resolve uncertainties and has positive market implications (Botosan, Citation1997; Diamond & Verrecchia, Citation1991; Lang & Lundholm, Citation1996; Skinner, Citation1994). However, recent research on implications of risk disclosures and critical accounting policies and estimates show that they may not resolve uncertainties to the extent that they also increase investors’ risk perceptions (Glendening et al., Citation2019; Gordon et al., Citation2019; Hope et al., Citation2016; Kravet & Muslu, Citation2013; Levine & Smith, Citation2011). Consequently, the capital market effect of disclosures about EL (which are difficult to estimate and inherently uncertain) is ambiguous.

The aim of this paper is threefold. First, we describe and corroborate prior findings on disclosure practices concerning EL in a comprehensive sample of European-listed firms operating in environmentally sensitive industries (specifically Oil and Gas, Mining and Utilities) between 2005 and 2016. Second, we investigate how external pressure in the form of media exposure is associated with the quality of the EL disclosure under IAS 37. Third, we examine the information content of the disclosures with respect to the market, given the uncertain nature of these disclosures and the underlying liabilities.

We use three related proxies for high-quality disclosure: the overall specificity of disclosure as well as the disclosure of two individual “key inputs” used to estimate EL (discount ratesFootnote4 and horizons, respectively). Disclosure specificity refers to an aggregate text-based measure of firm-specific information content based on the word count of named entities (the categories covered are: Authority, Measure, Method, Money, Organisation, Percentage, Region, Site, Substance, and Time). Meanwhile, estimates of the discount rates and horizons are two of the most important determinants of EL, as the discount factor and timing have a bearing on the amount of estimated future cash outflows (Sterner & Persson, Citation2008).Footnote5

Descriptive results highlight diversity in practice and corroborate prior findings of inadequate disclosures in single-country and -industry studies. Our results further show that disclosure specificity and disclosure levels of key inputs increase over time for all types of disclosures (especially for less material disclosures). One possible explanation is the increased public and media attention directed at environmental issues over the sample period. However, disclosure rates may still be regarded as low: In the most recent year of our sample (2016), 53% of firms provide information about discount rates, while the corresponding level for horizons is 59%. Notably, for firms reporting a material environmental liability, only 35% disclose both discount rates and horizons and a full 19% report neither key input. The fact that disclosures of horizons are consistently more common than disclosures of discount rates may be interpreted as an effect of horizon disclosures being explicitly required under IAS 37.

With respect to the effect of external pressure, we find overall evidence of a positive association between media exposure and disclosure quality. Specifically, we use two different types of proxies for media exposure: media coverage and tone (specifically uncertain and litigious sentiments) based on news articles from the Dow Jones Factiva database. We regress each disclosure variable on media exposure and find that media coverage is associated with a higher specificity score and a higher probability of reporting discount rates but not horizons. Again, we attribute this latter result to the timing of future cash outflows being an explicitly required disclosure item under IAS 37 and that firms ex ante are more likely to disclose it. Meanwhile, we find that litigious and uncertain media sentiments are positively associated with all of our disclosure variables.

Next, with respect to capital market implications, we find that overall disclosure specificity is negatively associated with bid-ask spreads in the period immediately following the filing date of the annual report, as well as analysts’ one-year-ahead earnings forecast errors and dispersion. In further analysis, we disaggregate the specificity score into its individual components and find that information about organisations, sites and substances (i.e. qualitative non-estimates-based components) drive the results. Overall, our findings suggest that EL disclosures reduce information asymmetry among market participants and thus have information content in capital markets.

A recent review study by Gray et al. (Citation2019) emphasises the need for more research to support standard-setting, pointing to the high level of uncertainty of EL and lack of rigorous accounting standards. Our study responds to their call for further research and informs standard-setters about EL disclosure practices in Europe. We extend prior research showing diversity in practice under IAS 37 among Oil and Gas firms in single-country settings (Abdo et al., Citation2018; Schneider et al., Citation2017), by documenting disclosure levels over time, across multiple environmentally sensitive industries, and across regions using a European-wide sample. Furthermore, we add to findings showing that firms are reluctant to disclose information about decommissioning activities (e.g. Abdo et al., Citation2018), by providing evidence that disclosure outcomes are sensitive to external pressure (such as media exposure). Specifically, our results suggest that EL disclosure levels have increased over time, but remain discretionary and are thus affected by the external pressure exerted on firms. In particular, media – in exposing firms to the public – plays a potentially important role in raising disclosure of this type of information. Furthermore, more specific EL disclosures appear to have information content as they reduce market uncertainty. Taken together, though public environmental concerns may have increased disclosures over time, we believe that more explicit disclosure guidelines for EL would contribute to less heterogeneous disclosure practices and thus improve the information environment. Given that external pressure appears to have an effect on disclosure levels, more explicit guidelines would empower auditors and other monitoring parties to request more useful disclosures.

Finally, our study is subject to a few caveats. First, although we apply instrumental variable (IV) estimation and obtain results consistent with our initial findings, we acknowledge that the discourse in media and firm-provided disclosures inevitably interact and the direction of causation is therefore not possible to fully disentangle. Second, the findings relating to the information content of the disclosures should be interpreted with caution as EL disclosure specificity (despite the inclusion of control variables) is likely to reflect the informational quality of the annual report as a whole, and may not capture the incremental information effect of the EL disclosure.

2. Background and prior research

2.1. EL disclosures under IFRS

IAS 37 specifies in par. 84 and 85 (see Online Appendix Section 1) that for each class of provision (such as EL), an entity should disclose the carrying amount at the beginning and end of the period; additional provisions made and amounts used during the period; any potential reversals; as well as changes to the discounted amount as a result of the passage of time or changes to the discount rate. This type of information is commonly a concise summary of amounts, reported in a tabular format. To bring context to the numbers, the standard requires complementary disclosure, including a brief description of the nature of the obligation, the expected timing of any resulting outflows of economic benefits (horizons), and indications of the uncertainties relating to the amount or timing of those outflows. Where necessary, “major assumptions” concerning future events, should also be disclosed.

Extant research on EL disclosures, such as provisions for decommissioning and site remediation, provides evidence of diverse disclosure practices despite mandatory disclosure requirements (Al-Shammari et al., Citation2008; Barbu et al., Citation2014; Peters & Romi, Citation2013; Rogers & Atkins, Citation2015; Schneider et al., Citation2017). Overall, firms provide disclosures strategically, taking into account the trade-off between costs and benefits of disclosure, especially when the information refers to items that are inherently uncertain and complex, such as EL (Abdo et al., Citation2018; Li et al., Citation1997). It is shown that companies provide poorer disclosures when they have strong incentives to withhold environmental information or when the cost of non-compliance is low (Peters & Romi, Citation2013).

Findings also point to opportunistic reporting to avoid recognising impairment of mining assets (Hilton & O'brien, Citation2009) and to poor compliance with disclosure requirements relating to asset retirement obligations under US GAAP (Statement of Financial Accounting Standards 143) by oil and gas companies (Rogers & Atkins, Citation2015). An investigation of compliance with IAS standards by companies listed in the Gulf Co-Operation Council, shows that while compliance has increased over time, there is significant variation across different accounting standards, with the lowest level of compliance for IAS 37 (Al-Shammari et al., Citation2008). A comparison of EL disclosures in France, Germany and UK shows that compliance varies across jurisdictions and depends on firm size (Barbu et al., Citation2014). This is in line with extant literature on environmental voluntary disclosures, which shows that these disclosures vary depending on the legal, social, financial, cultural, and political context (e.g. Adams et al., Citation1998; Adams & Kuasirikun, Citation2000). In particular, Dhaliwal et al. (Citation2014) argue that the wider corporate social responsibility disclosures depends on the extent to which a country’s law and public awareness support non-shareholder stakeholders’ interest and CSR requirements.

2.2. Hypothesis development

The general benefits of corporate disclosure are well documented in prior literature. Signalling theory posits that firms provide information to “signal” their performance and thus achieve market benefits such as decreased cost of capital (Hughes, Citation1986; Lambert et al., Citation2007). While this clearly applies to firms with “good news”, it is also plausible that firms with unfavourable information choose to disclose to avoid penalisation by investors who see “no news as bad news”, or to prevent legal and reputational repercussions (Chen et al., Citation2014; Skinner, Citation1994). Meanwhile, proprietary cost theory (Dye, Citation1985; Verrecchia, Citation1990) predicts that alongside the benefits of disclosure, firms consider potential proprietary costs of disclosing. Examples of such costs include the costs of regulatory action, potential legal penalties, competitors gaining informational advantages, reduced consumer demand for the firm’s products, and renegotiated supplier and labour contracts (Dye, Citation1985). EL are, by nature, proprietary because they are more likely to trigger public or political responses (Li et al., Citation1997) and are potentially associated with subsequent costs, including competitive disadvantages and litigation risk. Additionally, prior research on EL disclosures suggests that managers are aware of the potential negative market consequences of such disclosures – thus causing firms to strategically bias the information to avoid negative investor reactions (Abdo et al., Citation2018; Gray et al., Citation2019). For example, De Villiers and van Staden (Citation2006) find that mining companies provide lower levels of environmental disclosures due to legitimacy concerns and a desire to preserve their image following negative environmental impact.

Meanwhile, firms’ tendency to provide proprietary information is arguably higher when the expected costs of subsequent detection are high, such as when there is public scrutiny or potential penalties for non-disclosure. More disclosure is then required to maintain corporate reputation and legitimize firm operations to stakeholders, such as future investors, consumers and the public (Deegan, Citation2019; Peters & Romi, Citation2013). The media, in reflecting and shaping public priorities, can exert pressure on firms that are concerned with their reputation (Brown & Deegan, Citation1998; Capriotti, Citation2009). Individuals particularly rely on media as their source of information for issues with which they have no direct or little personal contact, such as environmental issues (Aerts & Cormier, Citation2009). Prior research indicates that media’s attention to environmental issues is associated with increased environmental disclosure in response to public pressure (Coetzee & van Staden, Citation2011; Cormier et al., Citation2005; Cormier & Magnan, Citation2003; Islam et al., Citation2018; Islam & Deegan, Citation2010). Furthermore, prior studies show that media coverage can play a disciplinary role by detecting accounting fraud (Miller, Citation2006), and that media tone influences strategic decisions of managers who are concerned with their reputation (Liu & McConnell, Citation2013) as well as voluntary environmental disclosures (Rupley et al., Citation2012). In particular, prior research shows that litigious and uncertain tone in media can reveal ambiguity, potentially reducing investor trust and thereby market value (Barakat et al., Citation2019). We argue that firms that face larger media coverage and are exposed to a more uncertain tone (reflecting an uncertain business environment) or litigious tone (reflecting potential threats to the firm’s legitimacy and reputation), are likely to provide more specific disclosure to reduce information asymmetry and avoid negative market consequences. Therefore, we predict that:

H1a: Media coverage is positively associated with the specificity of firm disclosures, as well as key inputs relating to the estimation, of environmental liabilities.

H1b: Uncertain and/or litigious media tone is positively associated with the specificity of firm disclosures, as well as key inputs relating to the estimation, of environmental liabilities.

For disclosures about risk factors or accounting items involving a high level of estimation uncertainty, it is less obvious what the capital market effects are. For example, empirical research examining disclosures of critical accounting policies and estimates show that such disclosures increase analyst forecast errors and dispersion (Gordon et al., Citation2019) and are negatively associated with the predictive value of earnings (Glendening, Citation2017; Levine & Smith, Citation2011).

Nearly all financial reporting items reflects estimates about the future and the inherent uncertainty in these estimates has increased over time (Barth, Citation2006; Christensen et al., Citation2012; Glendening et al., Citation2019). This uncertainty is especially pronounced in environmentally sensitive industries, such as the extractive industries (Gray et al., Citation2019). In particular, estimations of EL involve a number of subjective assumptions about the magnitude and timing of future cash outflows. Evidence from disclosures about management’s forecasts of future cash outflows in, for example, mining firms points to considerable forecast inaccuracy, which may limit the decision-usefulness of such disclosures (Gallery et al., Citation2008; Gray et al., Citation2019). However, a high level of disclosure specificity (as opposed to volume, which can reflect on boilerplate information) may counteract the negative effect of the inherent uncertainty in disclosures about risks or critical accounting estimates. In particular, the specificity of such disclosures is found to be associated with positive market reactions and reduced analyst forecast uncertainty in recent studies by Hope et al. (Citation2016) and Gordon et al. (Citation2019). These results are consistent with theoretical predictions that more precise disclosures reduce the premium associated with investors’ uncertainty about the variance of firm’s cash flows (Heinle & Smith, Citation2017). It follows that more specific disclosure about EL could improve the information content of the disclosure, thus allowing us to posit the following hypotheses:

H2a: The specificity of firm disclosures of environmental liabilities is negatively associated with bid-ask spreads.

H2b: The specificity of firm disclosures of environmental liabilities is negatively associated with analysts’ one-year-ahead earnings forecast errors and dispersion.

3. Research design

3.1. Sample selection

Our study examines long-term EL related to decommissioning and dismantling, land restoration, rehabilitation and clean-up. We identify three industries prone to recognising this type of liability: Oil and Gas (ICB: 0533–0577), Mining (ICB: 1771–1779) and Utilities (ICB: 7535–7577). The reason for restricting our sample to said industries is that the term “environmental liabilities” may refer to different types of costs in different industries and not be related to decommissioning and clean-up costs.Footnote6 Furthermore, even if disclosures in other industries and sectors refer to restoration or decommissioning costs, they are likely less material and/or unrelated to environmental issues.Footnote7 Our sampling frame includes all firms publicly traded on European stock exchanges and operating in above-described industries from 2005 to 2016. The initial sample consists of 4,788 firm-year observations (399 unique firms). We exclude firm-year observations if the firm is not listed in a given year, does not follow IFRS, does not have available annual reports, or does not have any EL. Furthermore, we lose some observations due to missing data in the public databases used in this study (S&P Capital IQ, Thomson Reuters Worldscope, or Factiva). The final sample yields 1,152 firm-year observations and 164 unique firms. presents the sample composition and the distribution of observations by year, country and industry.

Table 1. Sample selection and breakdown.

3.2. EL disclosure quality

We collect all narrative EL disclosures from the accounting policy note as well as the note for provisions in the financial statements and generate three proxies for high-quality disclosure. We generate two dummy variables indicating whether firms provide estimates of two key inputs for measuring the liabilities, namely discount rates (Discount) and horizons (Horizon). We also create a sample-specific index of named entities (Named Entity Recognition, NER) to measure the specificity of the text (Specificity).Footnote8 By counting only entity-specific words rather than all words, we attempt to avoid generic and boilerplate information. Specifically, using Python, we identify all the unique words (approximately 6,000) in our text corpus and apply labels to all named entities, grouping them into nine categoriesFootnote9 (Authority, Measure, Money, Organisation, Percentage, Region, Regulation, Site, Substance, and Time). presents detailed descriptions and some examples from these nine categories. We then apply a bag-of-words technique to tabulate word counts and generate a total specificity score for each firm-year based on our specificity wordlist. The total scores constitute the variable Specificity. All words contribute equally to the index (equal-weighting is thus applied) due to a lack of theory and given the evidence that equal-weighted measures are as powerful as weighted alternatives (Henry & Leone, Citation2016).

Table 2. The specificity measure and its underlying components.

3.2.1. Validity tests for the specificity measure

We argue that our specificity measure serves as a proxy for information content and is also able to reflect compliance with IAS 37. To validate our specificity measure, we read the EL disclosures for a subsample of firms to establish whether firms comply with IAS 37. Specifically, two researchers separately reviewed all disclosures in the Oil and Gas and Utilities industries for the years 2005, 2010, and 2015 and assessed whether those disclosures were “insufficient”, “sufficient”, or “comprehensive”.Footnote10 In cases where there was a disagreement between the two researchers, a third researcher reviewed and assessed the disclosures. We then compared the three points in time and reviewed cases in which there was a change in our assessment across periods or a firm-year observation was missing. Based on this procedure, we conclude that among 982 firm-year observations in the Oil and Gas and Utilities industries, 68 firm-year disclosures are “comprehensive”, 205 are “sufficient”, and 709 are “insufficient”. This suggests that for the majority of firm-years (approx. 72%), the provided information is not compliant with IAS 37 requirements. However, when applying a materiality threshold and include only observations that have provisions above 5% of total liabilities (228 firm-year observations), we find 26 comprehensive, 64 sufficient, and 138 insufficient disclosures. While the number of comprehensive and sufficient disclosures increases when we take into account materiality, the percentage of firms with insufficient (non-compliant) disclosures is still relatively high (approx. 60%). Finally, we generate a dummy variable that equals one for firms that provide either comprehensive or sufficient disclosures (representing compliance), and zero otherwise. Untabulated results of Pearson (Spearman) tests indicate that there is a 35% (39%) positive correlation between disclosure specificity and compliance (p-values < 0.001). We also conduct a mean difference test which compares specificity between groups of firms that comply with those that do not comply. We find that the mean value of our specificity measure is considerably higher for firms that have sufficient or comprehensive disclosures, as compared to firms with insufficient disclosures (mean diff: 15.806, t-value: 10.68). In Online Appendix Section 2, we present examples of three disclosures at low, medium and high specificity scores (at the 5th, 50th and 95th percentiles, respectively) together with their corresponding compliance levels.

3.3. Media exposure variables

We measure media exposure using both coverage and the tone of news articles found in Factiva, a database provided by Dow Jones Reuters that offers historical firm-specific media coverage.Footnote11 We argue that Factiva is a suitable measure of media exposure as our sample firms are less likely to be exposed on social media platforms than, for instance, companies on consumer product markets (such as food and drinks, electronics, clothing, etc.). In addition, the majority of social media users are unlikely to consult information provided in the notes of annual reports. They are instead more likely to pick up this information from regular news sources, meaning social media exposure would be a reflection of the content of regular news sources. Further, we assume that our sample firms are aware of this and are therefore more likely to respond to regular media exposure. We target publications from the following sources: “major news and business sources” and “Reuters Newswires” (excluding firms’ press release wires), and – restrict sample articles to the following subject filters: “environmental pollution”, “corporate environmental responsibility”, “sustainable development”, “natural environment” and “natural disasters”. We use the total number of unique publications (in any language) related to these environmental topics published during the twelve months leading up to the filing date of a firm’s annual report to construct a measure of media coverage (Media_cov).Footnote12

Furthermore, we extract the text from all publications available in English and measure the sentiment of the text. Similar to prior accounting research on textual analysis (e.g. Chen et al., Citation2014b; Lim et al., Citation2018; Liu & McConnell, Citation2013), we use the Loughran and McDonald’s (Citation2011) wordlists (henceforth LM), which are based on word usage in 10-K filings from 1994 to 2015 (updated annually) and thus well-suited to capture the interpretation of words in a business context (Loughran & McDonald, Citation2016).Footnote13 We use two dictionaries, Litigious (e.g. legal, law, litigation, forbade) and Uncertainty (e.g. ambiguity, approximate, assume, risk), to create two sentiment variables: Media_uncertain and Media_litigious.Footnote14 Though uncertain and litigious words connote a negative attitude, we deem uncertain and litigious wordlists to be more context-dependent and less ambiguous than a purely negative wordlist.

3.4. Multivariate models

3.4.1. Disclosure and media exposure

To test our first hypothesis (H1), we regress our disclosure variables on media exposure (while controlling for other factors that may drive variations in disclosures) using the following OLS and logit models:

(1)

(1)

(2)

(2) where subscripts i, j, and t refer to firm, country and time, respectively and Λ represents the logit function.

Specificity refers to the specificity score as described in Section 3.2 and KeyInput refers to either the Discount or Horizon variable. Media refers to either coverage (Media_cov) or tone (Media_litigious and Media_uncertain). The above models include a set of control variables that may influence disclosures. As firms with more (material) EL are likely to disclose more (Barth et al., Citation1997), we control for the size of EL, measured as EL scaled by total liabilities (EL), and the materiality of EL (MaterialEL), an indicator variable that equals “1” if the disclosed liability exceeds 5% of total liabilities, and “0” otherwise.

We also control for the effect of firm size measured as the natural logarithm of a firm’s market value of equity (lnMV), a firm’s growth potential as captured by the book-to-market ratio (BM), firm performance as measured by the return on assets (ROA), leverage as measured by the ratio of debt to total assets (Lev), and stock return volatility as measured by the standard deviation of daily stock return (sdRet). Furthermore, we control for ownership dispersion (FreeFloat) as a dispersed ownership structure may affect the demand for disclosure and thereby firm behaviour, and the number of business segments (NumSegments), a measure of the complexity of operations. Prior research on disclosure practices under IFRS shows that the strength of country-level enforcement drives cross-sectional differences (Brown et al., Citation2014; Cascino & Gassen, Citation2015; Gao & Sidhu, Citation2018; Mazzi et al., Citation2017). We use the combined enforcement and audit index created by Brown et al. (Citation2014) as a measure of accounting enforcement (Enforce). This index, which is based on data from the International Federation of Accountants (IFAC), Fédération des Experts Comptables Européens (FEE) and the World Bank, considers the relative power and influence of securities market regulators and other monitoring bodies of financial reporting, as well as the structure and quality of the audit profession in a given country.Footnote15 We also use two variables to control for whether firms provide additional environmental disclosures: GRI, an indicator variable that equals “1” if the firm is included in the Global Reporting Initiative’s (GRI) database of sustainability reports (see Clarkson et al., Citation2008), and “0” otherwise; and CSR_leg, an indicator variable that equals “1” if sample countries mandate CSR reporting during our sample period (see Dhaliwal et al., Citation2012), and “0” otherwise. Finally, to control for audit quality, we include a dummy variable for whether a company has a “Big 4” auditor.

3.4.2. The information content of EL disclosures

Our first test of the second hypothesis (H2) uses bid-ask spreads as a measure of the liquidity of a firm’s stock and thus as a proxy for information asymmetry (see Balakrishnan et al., Citation2014; Campbell et al., Citation2014; Chen et al., Citation2015; Hope & Wang, Citation2018). We apply the following OLS model:

(3)

(3) where subscripts i, j, and t refer to firm, country and time, respectively.

The bid-ask spread (BidAsk) is calculated as the average difference between a firm’s daily closing bid and ask price scaled by the average bid and ask price over n trading days following the firm’s annual filing date (i.e. ). To reduce noise in the measurement period, we focus on changes in the information environment in a relatively short interval following the filing date (n = 5 and n = 60). The variable of interest in the above model is Specificity.Footnote16

Our second test focuses on the relation between disclosure and analysts’ forecast properties. Analysts, who gain expertise within specific industries, need high-quality disclosures for their information processing ability (Kadan et al., Citation2012; Peterson et al., Citation2015). In the case of our sample firms, future clean-up costs are core for value assessments. When useful EL information is made public, e.g. through accounting disclosures, analysts’ uncertainty about firms’ future cash flows and earnings should decrease. The two measures that are commonly used to capture the accuracy and dispersion of analyst forecasts, are the absolute difference between the consensus earnings per share estimate and the actual earnings per share (AF_error) and the standard deviation of the estimates (AF_disp). Both variables are scaled by actual earnings per share. AF in the OLS model below refers to either of these measures.

(4)

(4) where subscripts i, j, and t refer to firm, country and time, respectively.

In models 3 and 4, we control for media coverage as it may be associated with market variables (see, e.g. Kothari et al., Citation2009). Furthermore, in addition to variables from Equation (1) and (2), we include the following variables that may be associated with information asymmetry: the size of total accruals in firms (Accruals) calculated as the change in operating noncash working capital (Francis et al., Citation2005), the number of analysts following the firm (NumEstimates), and earnings volatility as measured by the natural logarithm of the standard deviation of net income over the past five years (sdNI). We also control for the effect of share trading volume in the bid-ask spread regression, using a short and a long window as described above (Volume), and we include the total number of words in the EL disclosures to capture overall disclosure quantity (NumWords). Finally, in all models, we control for region, industry, and year fixed effects and use double-clustered standard errors (at the firm and year level). All continuous independent variables are winsorized at the 1st and 99th percentiles. The detailed definitions of all variables are provided in .

Table 3. Variable definitions.

4. Univariate and bivariate analyses

4.1. Summary statistics

shows summary statistics for all regression variables. The mean (median) number of specific words disclosed by sample firms is 13.25 (7). With respect to key inputs, only 40.3% of firm-year observations contain information about the discount rate, and only 53% contain information about horizons. The mean (median) number of publications (Media_cov) related to environmental issues is 27.4 (1). The large difference between the mean and median indicates that this variable is considerably skewed and potentially driven by other factors, such as firm size. We therefore carry out various robustness tests using a standardised version of this variable (see Section 5.1). EL, which is the environmental liability scaled by total liabilities, has a mean (median) of 5.9 (2.8) percent (this may be compared to a benchmark of 5% of total liabilities as a materiality threshold, see Barth et al., Citation1997). In our sample, the mean value of MaterialEL indicates that approximately 37% of firm-year observations have ELs that exceed 5% of total liabilities.

Table 4. Summary statistics.

The pairwise (Pearson) correlation matrix in shows a positive and significant correlation (p-value < 0.01) among all proxies for media exposure (Media_cov, Media_litigious, Media_uncertain) and the disclosure variables, except for Horizon, which is only correlated with Media_uncertain. This indicates that horizon disclosures are less sensitive to media exposure. Bid-ask spreads (BidAsk5, BidAsk60), proxies for information asymmetry, are negatively and significantly correlated with our specificity index (p-values < 0.05-0.1), and there is also a negative and significant correlation between analyst forecast dispersion (AF_disp) and disclosure specificity. As expected, the size of the EL is also positively and significantly correlated with disclosure specificity as well as the disclosure of horizons and discount rates (p-value < 0.01). Among other firm factors, Leverage (Lev), the number of business segments (NumSegments), earnings volatility (sdNI) and having a sustainability report (GRI) are also positively and significantly correlated with the disclosure variables.

Table 5. Pairwise correlations.

4.2. Trend and cross-sectional analysis of EL disclosures

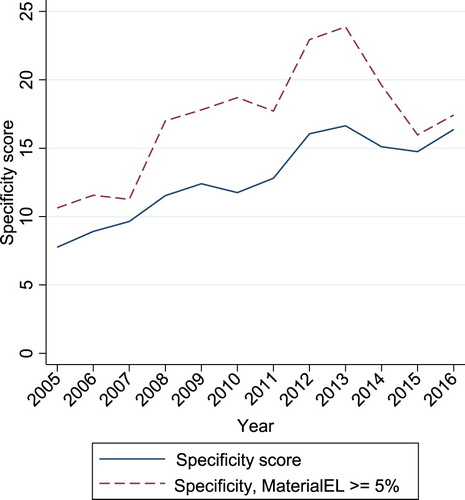

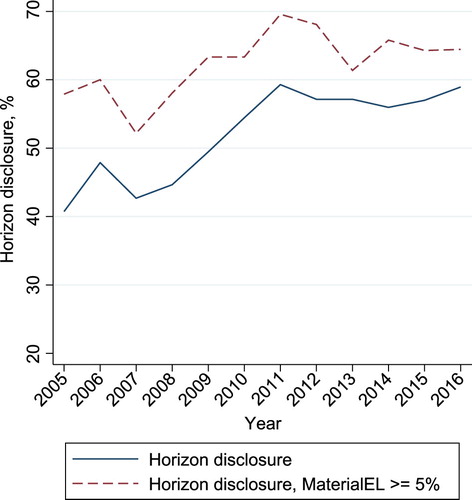

We examine disclosure practices over time for the whole sample and for a subsample of firm-observations with material EL (>=5%). shows variations for disclosure specificity levels over time, but also an overall increasing trend for our specificity score, both in the whole sample and in the sub-sample of firms with material EL.

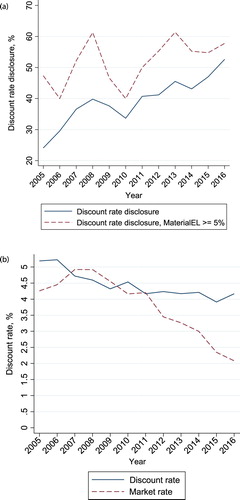

With respect to disclosures of discount rates over time, we examine both whether discount rates are disclosed at all ((a)) and discount rate levels ((b)). We find an overall increase in the disclosure trend, except for a drop in disclosures between 2008 and 2010 (especially when disclosures are material). Around these years, Europe was facing a financial crisis and market rates were (and still are) extremely low. We speculate that firms might have attempted to avoid drawing attention to the difference between the discount rate used for EL and the market rate at the time. We investigate this further by examining the actual discount rates reported. We see that up until 2011, reported discount rates are, to some degree, aligned with long-term (country-specific) government bond rates.Footnote17 However, as of 2011 going forward (a period with very low market interest rates in the aftermath of the financial crisis) the alignment with market rates discontinues and the gap increases over time.Footnote18 Thus, it appears that firms perceive both reporting of discount rates and the level of the discount rate used for measuring EL as a discretionary choice.

Figure 2. (a) Proportion of firm-years containing disclosures of discount rates (b) Disclosed discount rates and market rates over time.

Finally, our analysis of disclosures of horizons over time () suggests that the level of disclosure for this key input has increased over the sample period, though dropping somewhat after 2013. The pattern is especially pronounced for firms reporting material EL.

Next, we carry out a cross-sectional analysis of disclosure practices, with a breakdown of disclosure specificity and disclosures of key inputs by geographic region and industry. Panel A and B of show results for the pooled sample, including for a subsample of firms reporting material EL, while Panel C and D report the corresponding data for the most recent year in our sample (2016).

Table 6. Cross-sectional analysis of EL disclosures.

The average number of specific words is 13.3 in the pooled sample (material EL: 17.9). Looking at a cross-section of firms in 2016, the average number of specific words is 16.4 in the full sample (material EL: 17.4). Utilities firms make considerably more specific disclosures compared to firms in the extractive industries (with scores between 18.9 and 40). We speculate that these findings might be driven by the fact that these firms are, or were historically, state-owned; are subject to industry-specific regulation; and are considered of special public interest. Geographically, the highest specificity scores are found in the Continental and Eastern regions.

Turning to key inputs in the pooled sample, disclosures of discount rates and horizons are 40% and 53%, respectively (material EL: 53% and 63%). In 2016, the corresponding figures for discount rates and horizons are 53% and 59%, respectively (material EL: 58% and 64%). Notably, for firms reporting a material environmental liability, only 35% disclose both discount rates and horizons and a full 19% report neither key input (untabulated). Given the importance of these inputs for the estimation of EL, these figures may be considered fairly low. Comparing the two inputs, horizon disclosures are consistently higher than discount rate disclosures, which could be an effect of the explicit requirements in IAS 37 regarding disclosures of horizons. Examples of disclosures of discount rates and horizons are provided in the Online Appendix Section 2.

Comparing industries, we see that mining firms are most likely to disclose discount rates and horizons. With respect to regional differences, Anglo firms have the highest rates of horizon disclosure (but with comparatively small differences across materiality thresholds). This is consistent with potential box-ticking behaviour among firms facing relatively high financial reporting enforcement (see e.g. Brown et al., Citation2014). Meanwhile, disclosure levels of discount rates are highest in Continental and Eastern Europe (though there are too few observation to draw reliable inferences for Eastern Europe).

We make four main observations based on the above: (1) All types of disclosures are higher when EL are material, suggesting materiality thresholds and thus underlying economic factors affect disclosure choices; (2) disclosures of key inputs are relatively low, at levels around 50–65% for material EL; (3) disclosure levels in 2016 are higher compared to the full sample period, corroborating the trend analysis above (see ); and (4) we observe diversity among firms across industries and geographical regions, which can potentially be explained by country- and industry-specific norms or legal environments.

5. Tests of hypotheses 1 and 2

5.1. The effect of media exposure on EL disclosures

We test the first hypothesis by regressing the disclosure variables on media exposure. The results are presented in , where Panel A shows the effect of total media coverage on environmental issues (Media_cov) and Panels B and C present results on the tone of media articles (Media_litigious and Media_uncertain, respectively).Footnote19 The dependent variables of interest in Models 1 through 3 are Specificity, Discount, and Horizon, respectively.

Table 7. Tests of the association between media exposure and EL disclosure quality (H1).

Starting with Panel A, the coefficient of Media_cov is 0.063 in Model 1, which implies that an increase in media coverage by approximately 16 articles causes the company to provide one additional specific word (=16*0.063). This may be considered economically significant considering the mean (median) specificity score is around 13 (7).Footnote20 We also find a positive and significant association between media coverage and the disclosure of discount rates (Model 2: ME = 0.001, p-value < 0.01) but no association between the number of news items and disclosure of horizon. As the disclosure of horizons is explicitly required under IAS 37, there is a slightly lower dispersion in disclosure practices, and the disclosure is more likely to be driven by a materiality judgment (as evidenced by the positive and significant coefficient on MaterialEL in Model 3). Conversely, the specificity of the information and the disclosure of discount rates – in being more discretionary – increase with external pressure.

In Panels B and C, we consider the effect of media tone on disclosure. There is a positive and significant association between Specificity and Media_litigious (coeff. = 30.398, p-value < 0.05), and Specificity and Media_uncertain (coeff. = 34.970, p-value < 0.01). This indicates that when the media tone becomes 10 percentage points more litigious (uncertain), companies provide, on average, 3.1 (3.5) additional specific words. Furthermore, with respect to both horizons and discount rates, the coefficients on Media_litigious and Media_uncertain are positive and statistically significant. For example, as media tone becomes more litigious (uncertain), there is a 17.8% (41.7%) increased probability that companies disclose the discount rate.

Turning to the control variables, we find that the size of EL (EL) is significantly associated with disclosure specificity and the disclosure of discount rates. Furthermore, firm size (lnMV), leverage (Lev) and the standard deviation of returns (sdRet) are positively associated with disclosures variables in several model specifications. Firms are also more likely to disclose horizons when the number of segments are higher (NumSegments) or when operating in a country that has mandated CSR reporting (CSR_leg).

We carry out additional (untabulated) analyses to examine the robustness of our results with respect to the first hypothesis. First, to address potential concerns regarding whether the test variable is normally distributed, we use two alternative measures. The first variable is the natural logarithm of Media_cov, and the second measure is the residual from regressing Media_cov on the natural logarithm of total assets, market value, and the total number of environmental news articles in a given country and year. Using these alternative measures, results are consistent for all models, with retained significance levels. Second, we address potential endogeneity originating from reverse causality between our variables of interests, i.e. Media_cov and Specificity, by using an instrumental variable (IV) estimation technique. In the first stage, we regress Media_cov on all control variables along with two instruments, the level of democracy and the number of journalists for each European country and year. The predicted value of Media_cov is used in the second stage (i.e. the Specificity regression), where we find a positive and significant (at the 1% level) coefficient on Media_cov, supporting our hypothesis.Footnote21 A detailed description of these analyses are provided in the Online Appendix Section 3.

5.2. The information content of EL disclosures

Our second hypothesis concerns the association between disclosures and information asymmetry in equity capital markets, measured as bid-ask spreads and analysts’ earnings forecast errors and dispersion. presents estimated coefficients from the bid-ask spread model (Equation (3)) for two measurement intervals (n = 5 and n = 60). The coefficients on Specificity are negative and significant (e.g. for n = 5, coeff. = –0.006, p-value < 0.05), indicating that more specific disclosures about EL in general reduce bid-ask spreads in the days immediately following the filing date of the annual report and this effect persists throughout the next 60 trading days.

Table 8. Tests of the association between EL disclosure specificity and bid-ask spreads (H2a).

The coefficients on the control variables generally take on the expected signs: firms with higher leverage, larger number of segments, and higher return volatility have significantly larger bid-ask spreads. Larger firms, firms that are followed by a larger number of analysts, and firms in countries with CSR legislation, meanwhile, show lower spreads. The incremental effect of the number of words disclosed about EL is positive and significant, suggesting that after including measures of disclosure specificity and firm size, NumWords captures additional, non-specific and boilerplate, disclosures.

reports results from tests of analysts’ forecast errors and dispersion (Equation (4)). The specificity of disclosures is negatively associated with both analyst measures (AF_error: coeff. = −0.014, p-value < 0.05; AF_disp: coeff. = −0.017, p-value < 0.1), indicating that more specific information increase analysts’ accuracy and consensus about t+1 earnings per share. As expected, the number of analysts, firm size, and profitability, are negatively associated with at least analyst errors or dispersion, while leverage, ownership dispersion, and the standard deviation of net income are positively associated with errors and dispersion. Overall, findings are consistent with tests of bid-ask spreads and indicate that EL disclosures have information content and reduce information asymmetry among market participants.

Table 9. Tests of the association between EL disclsoure specificity and analyst forecast properties (H2b).

We also carry out two robustness tests for the second hypothesis. First, to investigate the direction of causation, we use the lagged values of the dependent variables (bid-ask spreads and analyst forecast properties) and expect no association with our test variable (Specificity). Using this alternative model specification, we do not find any significant association. Second, we use year-on-year changes in bid-ask spreads as the dependent variable and find that for both measurement intervals, the association between Specificity and bid-ask spreads remains significantly negative. The latter finding gives some support to the idea that disclosures are not directly affected by information asymmetries in the market, and that disclosures do vary over time (i.e. our main findings are not merely driven by firm-level effects).

Finally, we explore the information content of the underlying components of the specificity measure: Authority, Measure, Money, Organisation, Percentage, Region, Regulation, Site, Substance and Time. We find that those components that significantly explain bid-ask spreads and thus appear to drive the results in the main tests, are disclosures specifying regions (including countries); sites and locations; names of organisations and entities; and hazardous substances present in the company’s operations. Notably, these are qualitative disclosures that inform users about the nature of the operations and resulting liabilities, while quantitative, estimates-based disclosures do not significantly influence the market measures. For a detailed description of the analysis, please refer to the Online Appendix Section 4.

6. Conclusion

We study a particular type of liability that has no direct claimants and is difficult to measure mainly due to its longevity. This means that, although there is a public interest in environmental liabilities, few capital market actors (such as investors and creditors) actively demand disclosure on how they are estimated (Michelon et al., Citation2020). Further, due to their inherent uncertainty, companies are reluctant to provide information about these liabilities. These factors taken together creates an information vacuum related to EL, increasing the risk of the public having to take responsibility for clean-up costs in case of company failure.

As public awareness of environmental issues has increased in recent times, not least due increased media attention, the responsibility for clean-up and land restoration appears to be shifting from the public to the polluters themselves. The Canadian RedWater Energy Corp. (insolvent since 2015) might serve as a recent example of how bankruptcy trustee attempted but failed to shift the responsibility away from the company.Footnote22 The bankruptcy trustee wanted to sell valuable assets to pay back creditors and walk away from clean-up costs related to non-producing oil wells. However, Canada’s Supreme Court made the historic decision to overturn two lower court decisions and make EL a senior liability in the case of bankruptcy. In general, by forcing companies to recognise environmental costs, the associated externalities from their operations are internalised. However, whenever there is insufficient disclosure about estimated future cash outflows, or lacking formal and continuous monitoring of firm actions, the possibility of internalising future clean-up costs is reduced.

In this paper, we use a comprehensive sample of European-listed firms in environmentally sensitive industries and show diversity in EL disclosure practices across regions and industries. Although EL disclosures have increased over time, we show that only a little over half of our sample firms provide information about key inputs such as discount rates or horizons. We also find that external pressure in the form of media exposure remediates this situation and has a positive impact on firms’ disclosure practices, and that more specific disclosures appear to improve information content. Given that the disclosures reduce information asymmetry in the market, users would benefit from more homogeneous disclosures. We believe that more explicit disclosure guidelines from the IASB, such as requiring disclosure on key inputs used to estimate the EL, would contribute to companies being more forthcoming with information. Further, such guidelines would empower auditors and other enforcers to demand more detailed disclosure.

As to potential future research, low disclosure specificity and missing information about key inputs, coupled with little demand for disclosures, raises concerns of measurement errors in the EL. Given indications that qualitative EL disclosures drive our results in the capital market tests, future studies should investigate more closely which disclosure items and/or estimates are most useful for investors. In addition, recent developments in the area of non-financial reporting in the EU (see EU Directive 2014/95/EU) have further increased public awareness of (among other things) environmental issues and have put pressure on firms to be more transparent. We believe it would be beneficial to examine the effect of the new regulation on EL reporting, not least taking into account different sources of external pressure (including standard-setters, financial reporting enforcers, and media).

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (43.9 KB)Acknowledgements

We thank the IASB Standard Setting Process IAAER – KPMG Research Opportunities Programme Round 6 for funding. We also thank the program advisory committee members including Mary E. Barth, Holger Erchinger, Anne McGeachin, Paul Munter, Katherine Schipper, Donna L. Street, Ann Tarca, Alfred Wagenhofer, participants at the EAA Annual Congress 2018, the EUFIN conference in Stockholm 2018, the EAA Annual Congress 2019, Per Olsson, Thomas Schneider, Rok Spruk, Giovanna Michelon (Editor) and the two anonymous reviewers for helpful comments and discussions.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 “The IASB is considering possible amendments to IAS 37. Graham Holt discusses the areas that require clarification and consistency” https://www.accaglobal.com/vn/en/member/discover/cpd-articles/corporate-reporting/ias367-holt.html.

2 Issues focused on in these staff papers include provisions, discount rates and extractive activities.

3 Cap Gemini is calling for a Basel III style regulatory framework as they conclude that firms do not explain estimation methods and assumptions in their financial reporting (Cap Gemini, Citation2015).

4 The IASB is currently considering an amendment to IAS 37 with respect to the measurement inputs related to discount rates, something which, has also been raised within the scope of the IASB’s Discount Rate project.

5 Sterner and Persson (Citation2008) provide a telling example illustrating the importance of both the discount rate and the horizon. If the discount rate used were 1 percent, the discounted present value of a $1 million liability realised in 300 years would be around $50,000. If the discount rate were 5 percent, the discounted value would be less than 50 cents. Thus, the difference is non-linear, the discounted value changing by a factor of 100,000 while the discount rate merely changes by a factor of five.

6 For instance, European airlines routinely report provisions for CO2 emission recognized under the EU Emissions Trading Systems [EU ETS].

7 Meanwhile, Zalando, an online fashion retailer reports an increased restoration liability related to leasehold improvements of warehouses in the 2019 annual report.

8 Our sample-specific index of named entities is better suited to our specific context (i.e. financial reports issued by European-listed firms operating in the extractive industry or the utilities industry in a multi-language setting) compared to one of the already available NER classifiers, such as the Stanford NER, which identifies names of persons, locations and organizations, as well as money values, percentages, time and dates based on corpora of digital texts in a mainly US context (see, e.g., Hope et al., Citation2016).

9 We validate the categories across all research team members.

10 In making this assessment, a judgment had to be made whether the information would be considered decision-useful or not—that is, whether it could help a user determine the reasonableness of the estimations underlying the liabilities. In particular, in addition to considering compliance with explicit requirements (such as whether firms provide information about the timing of cash outflows), we assessed whether there were adequate descriptions and explanations of the inputs that go into the estimated future cash flows, as well as whether there was a discussion of the uncertainties involved (e.g. through sensitivity analyses).

11 Factiva provides superior data compared to for instance Twitter as historical data for neither the number nor the content of tweets are publicly available.

12 The Factiva database has a feature in the Search Builder screen that allows selecting only the unique stories by excluding identical duplicate articles from search results. Excluding duplicates has advantages as the media coverage variable could be artificially inflated for companies and subjects that have a lot of press coverage. Although we exclude duplicates in our main tests, we observe that the inclusion of duplicates does not have a considerable effect on the measure of media coverage (since the incidence of duplicates is low) and that results are unaltered using this alternative measure.

13 A note on scaling: In calculating sentiment scores, we follow Loughran and McDonald (Citation2011) and apply a tf-idf (term frequency—inverse document frequency) weighting scheme. tf(t,d) is calculated by tallying each term t in a given document d and dividing the score by the total number of words in d. tf is then multiplied by idf(t,D), which is the logarithm of the total number of documents N divided by the number of documents D in which term t appears. The first term is thus a frequency count scaled to prevent a positive bias towards longer documents, while the second term is an adjustment for the relative informativeness of the term—common terms being considered less informative. In calculating our specificity score, we do not apply such a weighting scheme but use the raw tf-score. This is because a scaled tf-score is more likely to capture conciseness rather than specificity (two firms providing the same number of specific words (named entities) may obtain very different scores, a lower score intuitively awarded to the more verbose firm). Furthermore, we do not apply idf weights as it is undesirable in the case of specificity to penalize firms whose named entities also occur in other firms (such as is the case with shared currencies, countries, etc.).

14 Available at http://www.nd.edu/~mcdonald/Word.List.html.

15 For example, countries score higher if the monitoring body has taken action regarding financial reporting, there are more extensive license requirements for auditors, and if there is a an audit oversight body that can apply sanctions (see p. 10 of Brown et al., Citation2014, for a full description of the index components). This index was updated in 2005 and 2008.

16 Since this is an aggregate measure of disclosure, it is more likely be associated with market uncertainty as compared to individual key inputs. However, in untabulated results we also examine the effect of key inputs such as discount rate and horizon (see Section 5.2).

17 We use yearly long-term government bond rates provided in the S&P Global market Intelligence database.

18 Firms regularly report several discount rates or a range of discount rates. Further, in many cases, firms also provide an inflation rate. We define reported discount rates as the average of rates provided subtracting the inflation rate, assuming that the discount rate is in nominal terms if the inflation rate is also provided. Incidentally, this assumption points to a potential problem for users in interpreting reported information and limited comparability among disclosures; however, for our purposes this is not a problem as this procedure would understate rather than overstate reported discount rates.

19 The sample size is significantly reduced using the tone of articles since we only use English-language articles. We acknowledge that the exclusion of media articles in local languages in non-English speaking countries may constitute a limitation in limiting the generalizability of our findings. However, there is no apparent reason why focusing on this subsample of firms would bias our results.

20 One word may appear insignificant but given that the proportion of specific words in sentences is small (i.e. the mean and median of specific word is 13 and 7, respectively), any additional specific word is potentially economically significant.

21 We test the validity of our instruments and conclude that the instruments do not suffer from over- or under-identification problem.

22 CBC News by Tracy Johnson on January 31, 2019. https://www.cbc.ca/news/business/supreme-court-redwater-decision-orphan-wells-1.4998995; Supreme Court Judgements on January 31, 2019, Case number 37627. https://scc-csc.lexum.com/scc-csc/scc-csc/en/item/17474/index.do.

References

- Abdo, H., Mangena, M., Needham, G., & Hunt, D. (2018). Disclosure of provisions for decommissioning costs in annual reports of oil and gas companies: A content analysis and stakeholder views. Accounting Forum, 42(4), 341–358. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.accfor.2018.10.001

- Adams, C. A., Hill, W.-Y., & Roberts, C. B. (1998). Corporate social reporting practices in Western Europe: Legitimating corporate behaviour? The British Accounting Review, 30(1), 1–21. https://doi.org/10.1006/bare.1997.0060

- Adams, C. A., & Kuasirikun, N. (2000). A comparative analysis of corporate reporting on ethical issues by UK and German chemical and pharmaceutical companies. European Accounting Review, 9(1), 53–79. https://doi.org/10.1080/096381800407941

- Aerts, W., & Cormier, D. (2009). Media legitimacy and corporate environmental communication. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 34(1), 1–27. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aos.2008.02.005

- Al-Shammari, B., Brown, P., & Tarca, A. (2008). An investigation of compliance with international accounting standards by listed companies in the Gulf Co-operation Council member states. The International Journal of Accounting, 43(4), 425–447. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intacc.2008.09.003

- Amihud, Y., & Mendelson, H. (1986). Asset pricing and the bid-ask spread. Journal of Financial Economics, 17(2), 223–249. https://doi.org/10.1016/0304-405X(86)90065-6

- Balakrishnan, K., Billings, M. B., Kelly, B., & Ljungqvist, A. (2014). Shaping liquidity: On the causal effects of voluntary disclosure. The Journal of Finance, 69(5), 2237–2278. https://doi.org/10.1111/jofi.12180

- Barakat, A., Ashby, S., Fenn, P., & Bryce, C. (2019). Operational risk and reputation in financial institutions: Does media tone make a difference? Journal of Banking & Finance, 98, 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbankfin.2018.10.007

- Barbu, E. M., Dumontier, P., Feleagă, N., & Feleagă, L. (2014). Mandatory environmental disclosures by companies complying with IASs/IFRSs: The cases of France, Germany, and the UK. The International Journal of Accounting, 49(2), 231–247. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.intacc.2014.04.003

- Barth, M. E. (2006). Including estimates of the future in today’s financial statements. Accounting Horizons, 20(3), 271–285. https://doi.org/10.2308/acch.2006.20.3.271

- Barth, M. E., McNichols, M. F., & Wilson, G. P. (1997). Factors influencing firms’ disclosures about environmental liabilities. Review of Accounting Studies, 2(1), 35–64. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1018321610509

- Botosan, C. A. (1997). Disclosure level and the cost of equity capital. Accounting Review, 323–349.

- Brown, N., & Deegan, C. (1998). The public disclosure of environmental performance information – a dual test of media agenda setting theory and legitimacy theory. Accounting and Business Research, 29(1), 21–41. https://doi.org/10.1080/00014788.1998.9729564

- Brown, P., Preiato, J., & Tarca, A. (2014). Measuring country differences in enforcement of accounting standards: An audit and enforcement proxy. Journal of Business Finance & Accounting, 41(1-2), 1–52. https://doi.org/10.1111/jbfa.12066

- Campbell, J. L., Chen, H., Dhaliwal, D. S., Lu, H. M., & Steele, L. B. (2014). The information content of mandatory risk factor disclosures in corporate filings. Review of Accounting Studies, 19(1), 396–455. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11142-013-9258-3

- Cap Gemini. (2015). EU regulation of nuclear decommissioning costs needed. http://uk.reuters.com/article/uk-nuclear-decommissioning-idUKKCN0SR2BV20151102

- Capriotti, P. (2009). Economic and social roles of companies in the mass media: The impact media visibility has on businesses’ being recognized as economic and social actors. Business & Society, 48(2), 225–242. https://doi.org/10.1177/0007650307305724

- Cascino, S., & Gassen, J. (2015). What drives the comparability effect of mandatory IFRS adoption? Review of Accounting Studies, 20(1), 242–282. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11142-014-9296-5

- Chen, J. C., Cho, C. H., & Patten, D. M. (2014a). Initiating disclosure of environmental liability information: An empirical analysis of firm choice. Journal of Business Ethics, 125(4), 681–692. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-013-1939-0

- Chen, H., De, P., Hu, Y. J., & Hwang, B.-H. (2014b). Wisdom of crowds: The value of stock opinions transmitted through social media. The Review of Financial Studies, 27(5), 1367–1403. https://doi.org/10.1093/rfs/hhu001

- Chen, S., Miao, B., & Shevlin, T. (2015). A new measure of disclosure quality: The level of disaggregation of accounting data in annual reports. Journal of Accounting Research, 53(5), 1017–1054. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-679X.12094

- Cheng, L., Liao, S., & Zhang, H. (2013). The commitment effect versus information effect of disclosure—evidence from smaller reporting companies. The Accounting Review, 88(4), 1239–1263. https://doi.org/10.2308/accr-50416

- Christensen, B. E., Glover, S. M., & Wood, D. A. (2012). Extreme estimation uncertainty in fair value estimates: Implications for audit assurance. Auditing: A Journal of Practice & Theory, 31(1), 127–146. https://doi.org/10.2308/ajpt-10191

- Clarkson, P. M., Li, Y., Richardson, G. D., & Vasvari, F. P. (2008). Revisiting the relation between environmental performance and environmental disclosure: An empirical analysis. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 33(4-5), 303–327. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aos.2007.05.003

- Coetzee, C. M., & van Staden, C. J. (2011). Disclosure responses to mining accidents: South African evidence. Accounting Forum, 35(4), 232–246. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.accfor.2011.06.001

- Cormier, D., & Magnan, M. (2003). Environmental reporting management: A continental European perspective. Journal of Accounting and Public Policy, 22(1), 43–62. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0278-4254(02)00085-6

- Cormier, D., Magnan, M., & van Velthoven, B. (2005). Environmental disclosure quality in large German companies: Economic incentives, public pressures or institutional conditions? European Accounting Review, 14(1), 3–39. https://doi.org/10.1080/0963818042000339617

- Deegan, C. (2019). Legitimacy theory. Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, 32(8), 2307–2329. https://doi.org/10.1108/AAAJ-08-2018-3638

- De Villiers, C., & van Staden, C. J. (2006). Can less environmental disclosure have a legitimising effect? Evidence from Africa. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 31(8), 763–781. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aos.2006.03.001

- Dhaliwal, D., Li, O. Z., Tsang, A., & Yang, Y. G. (2014). Corporate social responsibility disclosure and the cost of equity capital: The roles of stakeholder orientation and financial transparency. Journal of Accounting and Public Policy, 33(4), 328–355. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaccpubpol.2014.04.006

- Dhaliwal, D. S., Radhakrishnan, S., Tsang, A., & Yang, Y. G. (2012). Nonfinancial disclosure and analyst forecast accuracy: International evidence on corporate social responsibility disclosure. The Accounting Review, 87(3), 723–759. https://doi.org/10.2308/accr-10218

- Diamond, D. W. (1985). Optimal release of information by firms. The Journal of Finance, 40(4), 1071–1094. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6261.1985.tb02364.x

- Diamond, D. W., & Verrecchia, R. E. (1991). Disclosure, liquidity, and the cost of capital. The Journal of Finance, 46(4), 1325–1359. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6261.1991.tb04620.x

- Dye, R. (1985). Disclosure of nonproprietary information. Journal of Accounting Research, 23(1), 123–145. https://doi.org/10.2307/2490910

- Francis, J., LaFond, R., Olsson, P., & Schipper, K. (2005). The market pricing of accruals quality. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 39(2), 295–327. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacceco.2004.06.003

- Gallery, N., Gallery, G., & Nelson, J. (2008). The reliability of mandatory cash expenditure forecasts provided by Australian mining exploration companies in quarterly cash flow reports. Accounting Research Journal, 21(3), 263–287. https://doi.org/10.1108/10309610810922503

- Gao, R., & Sidhu, B. K. (2018). Convergence of accounting standards and financial reporting externality: Evidence from mandatory IFRS adoption. Accounting & Finance, 58(3), 817–848. https://doi.org/10.1111/acfi.12236

- Glendening, M. (2017). Critical accounting estimate disclosures and the predictive value of earnings. Accounting Horizons, 31(4), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.2308/acch-51801

- Glendening, M., Mauldin, E., & Shaw, K. W. (2019). Determinants and consequences of quantitative critical accounting estimate disclosures. The Accounting Review, 94(5), 189–218. https://doi.org/10.2308/accr-52368

- Gordon, E. A., Ma, X., & Runesson, E. (2019). Information uncertainty and critical accounting policies and estimates (Working Paper). http://www.business.uwm.edu/gdrive/Research%20Seminars/2019-20/GordonMaRunesson_20191104%20Final.pdf

- Gray, S. J., Hellman, N., & Ivanova, M. N. (2019). Extractive industries reporting: A review of accounting challenges and the research literature. Abacus, 55(1), 42–91. https://doi.org/10.1111/abac.12147

- Gupta, P. P., Sami, H., & Zhou, H. (2018). Do companies with effective internal controls over financial reporting benefit from Sarbanes–Oxley Sections 302 and 404? Journal of Accounting, Auditing & Finance, 33(2), 200–227. https://doi.org/10.1177/0148558X16663091

- Heinle, M. S., & Smith, K. C. (2017). A theory of risk disclosure. Review of Accounting Studies, 22(4), 1459–1491. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11142-017-9414-2

- Henry, E., & Leone, A. J. (2016). Measuring qualitative information in capital markets research: Comparison of alternative methodologies to measure disclosure tone. The Accounting Review, 91(1), 153–178. https://doi.org/10.2308/accr-51161

- Hilton, A. S., & O'brien, P. C. (2009). Inco Ltd.: Market value, fair value, and management discretion. Journal of Accounting Research, 47(1), 179–211. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-679X.2008.00314.x

- Hope, O.-K. (2003). Disclosure practices, enforcement of accounting standards, and analysts’ forecast accuracy: An international study. Journal of Accounting Research, 41(2), 235–272. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-679X.00102

- Hope, O.-K., Hu, D., & Lu, H. (2016). The benefits of specific risk-factor disclosures. Review of Accounting Studies, 21(4), 1005–1045. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11142-016-9371-1

- Hope, O.-K., & Wang, J. (2018). Management deception, big-bath accounting, and information asymmetry: Evidence from linguistic analysis. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 70, 33–51. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aos.2018.02.004

- Hughes, P. J. (1986). Signalling by direct disclosure under asymmetric information. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 8(2), 119–142. https://doi.org/10.1016/0165-4101(86)90014-5

- IASB. (2016). Staff paper: Present value measurement – discount rates research. Agenda ref 17C, London: International Accounting Standards Board.

- IASBa. (2019). Staff paper: Provisions. Agenda ref 22, London: International Accounting Standards Board.

- IASBb. (2019). Staff paper: Extractive activities, Agenda ref 19, London: International Accounting Standards Board.

- Islam, M. A., & Deegan, C. (2010). Media pressures and corporate disclosure of social responsibility performance information: A study of two global clothing and sports retail companies. Accounting and Business Research, 40(2), 131–148. https://doi.org/10.1080/00014788.2010.9663388

- Islam, M. A., Dissanayake, T., Dellaportas, S., & Haque, S. (2018). Anti-bribery disclosures: A response to networked governance. Accounting Forum, 42(1), 3–16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.accfor.2016.03.002

- Kadan, O., Madureira, L., Wang, R., & Zach, T. (2012). Analysts’ industry expertise. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 54(2-3), 95–120. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacceco.2012.05.002

- Kim, O., & Verrecchia, R. E. (1994). Market liquidity and volume around earnings announcements. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 17(1-2), 41–67. https://doi.org/10.1016/0165-4101(94)90004-3

- Kothari, S. P., Li, X., & Short, J. E. (2009). The effect of disclosures by management, analysts, and business press on cost of capital, return volatility, and analyst forecasts: A study using content analysis. The Accounting Review, 84(5), 1639–1670. https://doi.org/10.2308/accr.2009.84.5.1639

- KPMG. (2008). The application of IFRS: Oil and Gas. KPMG. http://www.energy.tt/plugins/p2009_download_manager/getfile.php?categoryid=26&p2009_sectionid=5&p2009_fileid=409&p2009_versionid=419.

- Kravet, T., & Muslu, V. (2013). Textual risk disclosures and investors’ risk perceptions. Review of Accounting Studies, 18(4), 1088–1122. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11142-013-9228-9

- Lambert, R. C., Leuz, C., & Verrecchia, R. E. (2007). Accounting information, disclosure, and the cost of capital. Journal of Accounting Research, 45(2), 385–420. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-679X.2007.00238.x

- Lang, M., & Lundholm, R. (1993). Cross-sectional determinants of analyst ratings of corporate disclosures. Journal of Accounting Research, 31(2), 246–271.

- Lang, M. H., & Lundholm, R. J. (1996). Corporate disclosure policy and analyst behavior. The Accounting Review, 71(4), 467–492.

- Lev, B. (1988). Toward a theory of equitable and efficient accounting policy. Accounting Review, 63, 1–22.

- Levine, C. B., & Smith, M. J. (2011). Critical accounting policy disclosures. Journal of Accounting, Auditing & Finance, 26(1), 39–76. https://doi.org/10.1177/0148558X11400579

- Li, Y., Richardson, G. D., & Thornton, D. B. (1997). Corporate disclosure of environmental liability information: Theory and evidence. Contemporary Accounting Research, 14(3), 435–474. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1911-3846.1997.tb00535.x

- Lim, E. K., Chalmers, K., & Hanlon, D. (2018). The influence of business strategy on annual report readability. Journal of Accounting and Public Policy, 37(1), 65–81. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaccpubpol.2018.01.003

- Liu, B., & McConnell, J. J. (2013). The role of the media in corporate governance: Do the media influence managers’ capital allocation decisions? Journal of Financial Economics, 110(1), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfineco.2013.06.003

- Loughran, T., & McDonald, B. (2011). When is a liability not a liability? Textual analysis, dictionaries, and 10-Ks. The Journal of Finance, 66(1), 35–65. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6261.2010.01625.x

- Loughran, T., & McDonald, B. (2016). Textual analysis in accounting and finance: A survey. Journal of Accounting Research, 54(4), 1187–1230. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-679X.12123