ABSTRACT

As part of introducing accrual accounting in the public sector, many governments have – voluntarily – implemented the International Public Sector Accounting Standards (IPSAS) for financial reporting. Amongst other claimed benefits, IPSAS have been argued to facilitate comparison of adopters’ financial reports and to lead to favourable conditions on credit markets. However, governments that are confronted with the implementation decision face a trade-off between unaltered adoption, partial adoption, adaptation and non-adoption of standards. Drawing on insights from the literature on standardization and practice variation, this paper analyses the reasons, expressed by various actors from nine European countries, for deviating from implementing unaltered IPSAS and proposes a taxonomy of these reasons. The results show that, first, substantial deviations exist, and second, there is a plethora of reasons for them. These deviations are presented and then structured in the further course of the paper. As a consequence of deviations, achieving comparability as the central aim of standardization runs the risk of being undermined.

1. Introduction

International Public Sector Accounting Standards (IPSAS) have been promoted as a “multi-purpose answer” to better meet the specific information needs of the public sector, to improve the transparency and reliability of public accounts and to facilitate consolidation of financial statements (e.g. Christiaens et al., Citation2015; for critical views outlining unintended and negative consequences, see Adhikari et al., Citation2019; Goddard et al., Citation2016). First and foremost, however, the IPSAS are said to enable comparison of the financial reports of implementers (Christiaens et al., Citation2015; IPSASB, Citation2020). The objective of IPSAS is “to ensure comparability both with the entity’s financial statements of previous periods and with the financial statements of other entities” (IPSASB, Citation2020, p. 163). Another expected positive effect of comparability is favourable conditions for borrowers on credit markets (ACCA, Citation2017; Chytis et al., Citation2020), so governments are expected to have an interest in aligning their national counterparts with these established international standards.

Adoption of IPSAS issued by the IPSAS Board (IPSASB) is not mandatory (IPSASB, Citation2020; Oulasvirta & Bailey, Citation2016). Given this, governments confronted with the decision to implement IPSAS (we synonymously refer to this as the “translation of IPSAS into national accounting systems”) have the choice between unaltered adoption, partial adoption (i.e. not adopting all standards), adaptation of certain standards and not implementing IPSAS at all. In this paper, we refer to partial adoption and adaptation as “deviations”. There is a trade-off between an increased comparability of financial statements among countries (and possibly easier access to the credit market) in the case of unaltered adoption and the necessity to respect national accounting particularities (Manes Rossi et al., Citation2016). As a consequence of deviations (and of non-adoption), there is a threat that the comparability of reporting between entities will be undermined, with the risk of leaving the full reform potential to be unleashed by IPSAS’ implementation unrealized (Mattei et al., Citation2020). This is also echoed by the current discussion on whether the plurality of accounting options allowed by IPSAS may actually reduce comparability (EY, Citation2016; PwC, Citation2019). Given these issues, we are interested in better understanding the particular reasons why governments decide against appropriate comparability of their financial reports with those of other governments.

Several studies – with both national (e.g. Ada & Christiaens, Citation2018; Grossi & Steccolini, Citation2015; Oulasvirta, Citation2014) and international-comparative focus (e.g. Christiaens et al., Citation2015; Polzer et al., Citation2020; Schmidthuber et al., Citation2020; Sellami & Gafsi, Citation2019) – have explored the implementation of IPSAS. Most of them, however, have only differentiated between unaltered and non-adoption of standards and have paid scant attention to issues of the partial adoption and adaptation of IPSAS. That said, little is known about the reasons for deviations from a comparative perspective (Caperchione et al., Citation2017). Recently, a number of studies have focused on the adoption of global accounting standards (IFRS) in the private sector, mapping national deviations and discussing underlying reasons for these (e.g. Albu et al., Citation2014; Botzem, Citation2012; Dahlgren & Nilsson, Citation2012; Nobes, Citation2013). The work by Albu et al. (Citation2014) seems particularly relevant to our research, as the authors argue that expressed reasons for non-compliance can come in the form of either active explanations or justifications, with the goal of seeking legitimacy. Given the differences between the two sectors regarding goals and involved actors and stakeholders, the reasons for adopting or adapting international standards are likely to differ between the private and public sectors. As accounting harmonization has so far received less scholarly attention in the public sector and a systematic analysis is lacking, a taxonomy of reasons is needed. We expect that a more nuanced view of implementation variations will shed greater light on the different forms of deviations from IPSAS and on governments’ underlying motives. We ask the following research question: What are the expressed reasons of various actors in nine European countries for deviations from IPSAS or for refusing to adopt IPSAS at all?

Focusing on financial reporting at the central government level, this study analyses the reasons for deviating from implementing unaltered IPSAS in Austria, Estonia, Iceland, France, Poland, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland and the United Kingdom (UK). These countries provide an appropriate picture of governments with diverging administrative and accounting traditions and stages of financial management reforms; they mirror well the different implementation variants (see the section on methods for further reasons for country selection).

Conceptually, this paper draws on previous research on standardization (Brunsson et al., Citation2012) and the concept of “practice variation” from new institutional theory (Ansari et al., Citation2010; Lounsbury, Citation2008). Standards have been claimed to make coordination and cooperation between implementers easier (Brunsson & Jacobsson, Citation2002). However, the fact that subscribing to standards such as IPSAS is voluntary “often limits their implementation in some countries or regions” (Brunsson et al., Citation2012, p. 621). Our methodological approach combines document analyses, interviews and communication with reform actors and experts.

This study adds to the growing body of literature on harmonization of accounting systems in the public sector (e.g. Manes Rossi et al., Citation2016). In a nutshell, we find that the selected European governments implemented the IPSAS heterogeneously, and a range of diverse reasons exists for decisions not to implement certain standards and/or to adapt standards. We show that comparability of financial reporting, as the central objective of standardization, is undermined. With this, the paper adds empirically to the literature on standardization in public sector accounting. Conceptually, we contribute to the stream of “competitive regulation” in the literature on standardization (Djelic & Den Hond, Citation2014; Jamal & Sunder, Citation2014), adding the notion of “dual moving targets”, as both IPSAS and corresponding national standards develop at the same time. We argue that governments, nonetheless, might continue with (selectively) adopting IPSAS for reasons of gaining or maintaining legitimacy (e.g. Oulasvirta, Citation2014; Tagesson, Citation2015).

The remainder of this research is organized as follows: Section 2 outlines the conceptual orientation, by discussing the literature on IPSAS and their diffusion, as well as the extant literature on standardization and “practice variation” from new institutional theory. Next, after data and methods are introduced (Section 3), we present the results of our investigation and provide a discussion in which we structure the reasons that are put forward for deviations (Sections 4 and 5). The paper concludes with a summary, which outlines implications for theory and practice (Section 6).

2. Conceptual orientation

2.1. IPSAS implementation in Europe and reasons for deviations

The harmonization of accounting systems is described as a process by “which accounting moves away from total diversity of practice” (Roberts et al., Citation2005, p. 11). Harmonization is intensively researched in the current accounting literature, in the private (Nobes & Parker, Citation2016; Roberts et al., Citation2005), the non-profit (Cordery et al., Citation2019) and the public sectors (Caperchione, Citation2015; Manes Rossi et al., Citation2016). Fuertes (Citation2008) differentiates harmonization from standardization. While the former “involves a reduction in accounting variations, […] standardization entails moving towards the eradication of any variation” (ibid., p. 327). Doupnik and Perera (Citation2012) differentiate between harmonization and convergence. Convergence implies the adoption of one set of international standards; instead, harmonization allows different countries to have different standards, as long as the standards do not conflict (Doupnik & Perera, Citation2012). The diversity of national responses to global standards is conditioned by the interplay between actors “searching for legitimacy and the attainment of their own (mutually conflicting) interests” (Albu et al., Citation2014, p. 489).

As global standards for public sector accounting, IPSAS have emerged step-by-step since the establishment in 1986 of the Public Sector Committee of the International Federation of Accountants (IFAC), which was later transformed into the IPSASB (see, e.g. Aggestam-Pontoppidan & Andernack, Citation2016). Standards are issued after intensive discussions in the IPSASB, based on guidelines, consultation papers and exposure drafts. Further, in late 2014, the IPSASB published the first parts of a conceptual framework.

As they formally have the character of recommendations (IPSASB, Citation2020; Oulasvirta & Bailey, Citation2016), the IPSAS serve as guidelines for governments and national standard setters to formulate or revise their own national accounting standards, which then comply to a greater or lesser degree with IPSAS (Caruana, Citation2019). Especially for emerging economies, the IPSAS take the role of a quasi-benchmark (Toudas et al., Citation2013). Therefore, each IPSAS is formulated in a very detailed way, providing information about objectives, scope, definitions and details of recognition, disclosure and measurement (see IPSASB, Citation2020). Currently, 42 IPSAS have been issued – the majority of them for financial reporting, which lies at the heart of this paper.

The IPSAS follow the International Accounting Standards/International Financial Reporting Standards (IAS/IFRS), wherever appropriate, with very few material differences (such as additional commentaries, different terminology and definitions; see EY, Citation2013). However, from a material perspective, public sector entities deviate from private corporations with regard to different issues (e.g. sovereign revenues like taxes, transfer payments to citizens and other entities, assets for community use or concessions; Biondi, Citation2016) so that a number of specific standards and also deviations from IFRS are necessary.

The development of standards is an ongoing and stepwise process: A number of standards were established only several years after the pronouncement of the first 30 standards, particularly such standards which deal with specific public sector issues, like social benefits or heritage assets. With an increasing focus on public sector accounting particularities, the IPSASB seems to be more open to a public sector specific regulation of such issues, at the expense of the full compliance of IPSAS with IFRS (Jensen, Citation2020).

Harmonization of public sector accounting systems, such as through IPSAS, is argued to have several advantages, particularly in the context of the European Union regarding comparable financial information in the annual accounts of member states. On the other hand, however, the accounting literature presents a variety of arguments and motivations for deviations from established international accounting standards. More particularly, the public sector related literature (e.g. Adhikari et al., Citation2013; Caperchione, Citation2015; Caperchione et al., Citation2017; Christiaens & Neyt, Citation2015; Manes Rossi et al., Citation2016) offers broadly speaking seven groups of reasons for deviations from IPSAS or not adopting IPSAS at all. These can be summarized in the following taxonomy:

IPSAS are inadequate for public sector accounting (“publicness”);

Lacking the specificity of the existing standards (IPSAS are principle-based and allow too many disclosure and valuation options);

Maturity and completeness of the IPSAS: Deviations are necessary because IPSAS do not cover or disregard certain accounting issues, such as social benefits, pension provisions, heritage assets. Authors also critically remark that IPSAS do not pay much attention to the issue of budgeting, which is of particular relevance in the public sector;

Contradictions and conflicts between IPSAS and established national accounting standards or existent administrative or accounting traditions: In this context, concerns are also expressed regarding a reduction in national sovereignty or a loss of the power of national standards setters;

IPSAS and national accounting standards as dual moving targets: Both the IPSAS and the national standards are in continuous development, as new standards are amended, and existing ones revised. Deviations between IPSAS and national standards are therefore to some extent unavoidable;

Limited incentives or pressures to adopt IPSAS in a certain country: In contrast to the private sector, governments are less dependent on the reactions of creditors, lenders or market players, which usually request comparable financial reports following common accounting standards. Similarly, a government may hesitate to adopt IPSAS because other countries with the same administrative traditions have decided for non-adoption. And finally, a government may be reluctant to adopt IPSAS, because its accounting staff is not familiar with IPSAS and the underlying accruals concept;

IPSAS adoption not economically feasible: Governments argue against IPSAS because of the disproportionate cost of implementation and/or operation.

As this list shows, there is quite a range of reasons against a full adoption of IPSAS as national public sector accounting standards, which (may) play a role in the decision-making process of governments regarding how to cope with the complex issue of IPSAS’ adoption for their own governmental reporting concept and the extent to which to deviate from IPSAS. Consequently, various countries and international organizations (such as the United Nations, the European Commission, etc.) have only partially implemented IPSAS or have made significant amendments to certain standards (Grossi & Steccolini, Citation2015). This is possibly because IPSAS serve primarily as principle-based guidelines for governments to establish their own standards and therefore represent a set of “soft” standards (Oulasvirta & Bailey, Citation2016).

Given different degrees of implementation and compatibility with IPSAS standards between countries (PwC, Citation2014 and Citation2019), the starting point of this paper are recent claims that implemented IPSAS

only allow for de jure comparability of financial reports at a very broad level. Their implementation and interpretation in practice (due to the options permitted and the judgement required) does not allow for de facto [comparability in financial reporting]. (Mattei et al., Citation2020, p. 158, emphases in the original)

2.2. Standardization, deviations and practice variation

Organizational theory, and here in particular extant research in the area of standardization and practice variation (Ansari et al., Citation2010; Lounsbury, Citation2008), provides the conceptual lens to look at the implementation of IPSAS. We chose this analytical lens because other analytical perspectives, such as “diffusion of innovations” (Rogers, Citation2003) or “policy transfer” (Dolowitz & Marsh, Citation2000), lack a dedicated focus on possible adaptations during the translation of standards and are therefore not able to fully explain the observed deviations.

Following Ada and Christiaens (Citation2018), we use the term “deviation” when a difference in material content between an issued standard and translation can be observed. This is especially relevant, as IPSAS are principle-based and not rule-based standards. There are manifold understandings of what constitutes a deviation, and the literature refers to three sources of such deviations. First, regarding linguistic translations stemming from translating standards from English into national languages (Dahlgren & Nilsson, Citation2012), on the stricter end of the spectrum, Evans et al. (Citation2015) hold that issuing standards in British English instead of American English could already constitute a deviation in the translation of accounting standards. A second stream of the literature is concerned with sociological aspects of translation and the “glocalization” of concepts and ideas (Drori et al., Citation2014). In this context, the role of actors engaged in the translation of accounting standards has recently received scholarly attention (Jensen, Citation2020). Third, the administrative (i.e. the organization of public sectors) and accounting contexts in adopting countries matter (Nobes, Citation2013).

Although standards are ubiquitous in modern life, standardization has claimed to be under-studied so far in organizational research (Brunsson & Jacobsson, Citation2002). Scholarly interest in standardization (Brunsson et al., Citation2012) has acknowledged that contemporary standard setting often includes a “transnational” element and that there are “interactions between national and transnational institutional orders” (Djelic & Quack, Citation2008, p. 317). What is more, Djelic and Den Hond (Citation2014) state that we live in a world of plural and multiple standards. Their research finds that, while “standardization would seem to suggest regularity, rationalization, and a reduction of diversity if not the advance of homogeneity and convergence, we can easily document a surprising multiplicity and plurality in our transnational world of standards” (ibid., p. 67). The plurality of accounting standards and the relationships between them are echoed by current research (Jamal & Sunder, Citation2014).

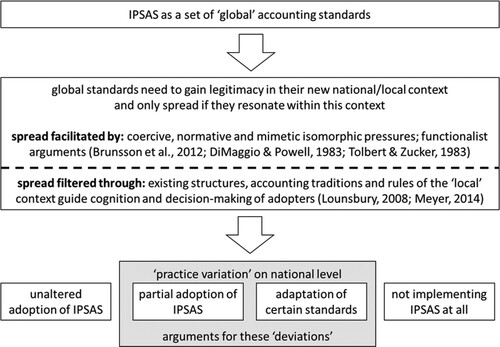

illustrates our analytical framework. It may be questioned why standards like the IPSAS are implemented by organizations at all, given that there are no legal sanctions for non-implementation. Extant literature points towards functionalist (e.g. achieving higher performance: Brunsson et al., Citation2012, or receiving better conditions when borrowing on the credit market: Chytis et al., Citation2020) and institutionalist perspectives (coercive, normative and mimetic isomorphic pressures to gain and maintain organizational legitimacy; Jorge et al., Citation2020; Oulasvirta, Citation2014; Tagesson, Citation2015). Coercive pressures are particularly relevant for emerging economies (stemming from donor organizations), as, e.g. illustrated by Goddard et al. (Citation2016). Signalling compliance might already be sufficient (Tagesson, Citation2015), which explains the possibility of different “variations of the IPSAS theme” in implementation. Tolbert and Zucker (Citation1983) combine the two perspectives and argue that early implementers of a new standard can benefit from efficiency gains, while a motive for late implementers might be to gain legitimacy from embracing a practice already institutionalized elsewhere.

There are two inherent tensions in standardization. First, (universal) standards must be de-contextualized, i.e. to be “necessarily abstract to some degree and general in scope” (Brunsson et al., Citation2012, p. 621). Standards therefore cannot completely “cater to the idiosyncrasies of the organizations to which they apply” (ibid.).

Second, new institutional theory holds that “broader cultural beliefs and rules structure cognition and guide decision-making” (Lounsbury, Citation2008, p. 350). Furthermore, before (global) ideas such as standards become accepted, they “have to pass through a powerful filter of local cultural and structural constraints to also gain legitimacy in their new local context and can, thus, only spread if they resonate within this context” (Meyer, Citation2014, p. 81). Given this, the question that arises when implementing standards

is whether a standard should be adapted to the local context [here, the national context, the authors] or whether the local context should be changed to fit the standard. Such processes are characterized by what has been described as the dynamics of “adjustment” and “translation” (Brunsson et al., Citation2012, p. 621).

While new institutional theory was initially concerned with questions of isomorphism, i.e. why organizations become increasingly alike, issues regarding “practice variation” have become more prominent over time (Lounsbury, Citation2008). Here, the issue of “adaptation” or “translation” – i.e. implementing (global) ideas and standards in a certain political/administrative context – has been inspiring research in both the public and private sectors (Albu et al., Citation2014; Albu et al., Citation2020; Jorge et al., Citation2019; Krishnan, Citation2018). Global standards and their national/local translations represent an example of a form of “glocalization”, which is characterized by the “mutually constitutive character of the global and the local” (Albu et al., Citation2014, p. 85).Footnote1 National deviations are an outcome of such “glocalization” processes. However, Brunsson and Jacobsson (Citation2002) point out that there might be inherent tensions between the national and global dimensions: An obvious consequential strategy to deal with these tensions would be decoupling (Tagesson, Citation2015), i.e. where an implementer “standardizes its practice but does not practice the standard” (Brunsson & Jacobsson, Citation2002, p. 128).

Moreover, potential implementers of IPSAS can react to the standards in different ways. Extant literature has come up with different concepts for summarizing reactions to and strategies for dealing with changes in (accounting) regulations (e.g. Jeppesen, Citation2010; Walker, Citation2016). In this research, however, we follow the categorization of Brunsson and Jacobsson (Citation2002), who differentiate between unaltered adoption, partial adoption, adaptation and non-adoption of standards. This categorization ultimately helps us better understand the different “shades of grey” of harmonization in public sector accounting (Caruana, Citation2019; Manes Rossi et al., Citation2016), including limits and unintended consequences (Adhikari et al., Citation2019; Goddard et al., Citation2016).

To conclude, while standard setting has been intensively researched in private-sector accounting (Albu et al., Citation2014; Krishnan, Citation2018; Nobes, Citation2013), few studies take such a conceptual lens in the public sector. This paper addresses this research gap. The next section outlines our methodological approach.

3. Method, data and analysis

Building on studies that analyse the degree of national implementations of IPSAS (e.g. Christiaens et al., Citation2015), we are particularly interested in exploring the reasons for deviations from IPSAS. In order to fulfil this aim, we examine cases from countries where the financial reporting legislation (at least partly) draws on or is informed by IPSAS. The selected cases are reasonably well documented in both the academic debate and the practitioner-oriented literature. In order to obtain a comprehensive overview of the multifaceted deviations in the IPSAS “universe”, we sample our cases following the “diverse” method of case selection, to illuminate “the full range of variation” (Seawright & Gerring, Citation2008, p. 297) of both deviations and the corresponding reasons. Therefore, our approach to the selection of cases can be described as “purposeful sampling” (Patton, Citation2015, p. 265). With such a research strategy, generalizability of the results cannot be claimed.

The countries under review were selected with regard to the following criteria: In general, our review concentrates on Europe and more specifically on countries whose governments have shifted their public sector accounting system at central level to accruals and have issued appropriate accounting standards. With this, countries which do meet our selection criteria (such as Germany, Italy or the Netherlands) were omitted. We chose countries with different regional affiliations, i.e. countries from Continental, Northern, Central-Eastern, Southern and Western Europe. This selection also covers diverging administrative (Meyer & Hammerschmid, Citation2010) and accounting traditions (Nobes & Parker, Citation2016). Further, we paid attention to varying periods of accounting change, as we expect different opinions on IPSAS from early movers compared with late movers.

We include the UK in our analysis, although it has opted to implement not IPSAS but (EU adapted) IFRS for public sector financial reporting. The reasons for including the UK are that there is a substantial overlap between IPSAS and IFRS and that the UK scrutinizes new IPSAS when developing its own regulations.

For data triangulation purposes (Hopper & Hoque, Citation2018), we drew on multiple sources of information in each country. Besides official documentation (e.g. laws and regulations, comments to laws, government handbooks on financial reporting), we reviewed academic and practitioner literature (e.g. ACCA & IFAC, Citation2020; PwC, Citation2014 and Citation2019). Interviews and correspondence with senior bureaucrats, politicians, national standard setters, auditors, professionals from accounting bodies and academics in each country complemented this desk research. Initially, respondents were selected from the personal networks of the researchers. We then used a snowball sampling approach to recruit further interviewees or informants until saturation was reached (i.e. additional interviews yielding little new information). For example, in Iceland we started with a contact in the International Monetary Fund (IMF) who recommended two further interviewees in the Ministry of Finance and the Financial Management Authority, leading to yet another interview in the Icelandic National Audit Office. About a year later, we followed up with these interviewees for updates.

Overall, 28 persons were contacted and/or interviewed (see for details). Interviewees and informants quite often held multiple roles, e.g. as an academic and as one involved in standard setting.

Table 1. Number and affiliation of contact persons in the reviewed countries (source: the authors).

To compare the cases, we compiled an overview table (), in which we present a description of both accounting change and the present situation in the selected countries. In a rather general assessment, we further estimate the extent to which the respective national public accounting standards correspond with IPSAS. Here, we were aided by studies published by PwC (Citation2014 and Citation2019) on the “maturity” of national accounting systems (although the underlying valuation concept of these assessments is not fully transparent). Additionally, the table provides information on both the way the respective governments implemented the current accounting standards and a standard setting board (if existing). In a summary form, the table finally shows important deviations from IPSAS and the underlying reasons.Footnote2

Table 2. IPSAS Implementation, deviations and expressed reasons (source: based on PwC, Citation2014 and Citation2019, amongst others).

4. Extent of IPSAS implementation and national deviations

The accounting standards of the countries under review show diverging trajectories in terms of harmonization towards IPSAS (). The compliance of the accounting concepts and standards of the reviewed countries with the IPSAS is generally quite high, even if some national standards – e.g. in France or Sweden – do not refer explicitly to IPSAS. The UK, Switzerland, Spain and Estonia show only quite minor deviations from IPSAS (which is not surprising in the case of the UK, given that these standards are IFRS-based which are closely affiliated with IPSAS). The differences of national accounting standards in countries like Sweden, Austria or Spain from the so-far issued IPSAS can be explained with an early implementation date in these countries: Because of the ongoing development of IPSAS, several of the more recent IPSAS had not yet been published when the respective accounting rules were passed.

With regard to the way that codification of accounting changes takes place, we found some interesting differences: None of the selected countries implemented the IPSAS in a direct form. Instead, all countries implemented IPSAS by issuing national rules or standards which are influenced by IPSAS (e.g. Bauer et al., Citation2011). Switzerland is the country with the closest link between national legislation and IPSAS, as “[a]t federal level IPSAS has been directly adopted through references in legislation […]. The aim is to eliminate departures from IPSAS over time” (European Commission, Citation2013, p. 90). The Continental Rechtsstaat governments issued specific budgeting and reporting laws covering the accounting standards (Austria and Switzerland; Bauer et al., Citation2011). Other countries either established common national accounting standards valid for both the public and the private sector (Estonia and Poland; Argento et al., Citation2018) or issued specific standards for public sector organizations (PSOs; France and Sweden). As already mentioned, the UK has implemented IFRS instead of IPSAS. Here, the government financial reporting manual (FReM) provides the technical accounting guide for the preparation of financial statements.

Interesting, from a processual perspective of closing differences between IPSAS and national legislation, is that Estonia has established a procedure in which the national standards are updated on an annual basis to the state of the art of IPSAS:

The main target is not the full adoption of IPSAS but the better adaption into the Estonian guidelines. The guidelines are annually updated and developed, and also the alignment to IPSAS is carefully taken into consideration. (Estonia #2)

As a small country, we tried to be practical and pragmatic. So, why develop something else if there is an international system already? And probably also the belief that it’s a matter of time until all countries will implement IPSAS. (Estonia #1)

We are a small country, and maintaining different accounting principles, even only from the point of view of IT and people, does not make sense. (Estonia #1)

Non-adoption of standards: Countries such as Austria, Sweden and Iceland disregard, e.g. standards on “Financial Reporting in Hyperinflationary Economies” (IPSAS 10) or “Investment Property” (IPSAS 15) (ESV, Citation2013; IMF, Citation2014; MoF Austria, Citation2013). Segment reporting (IPSAS 18) has not been implemented in Poland and Switzerland (CFFR, Citation2015; Federal Council Switzerland, Citation2018). Finally, consolidation (IPSAS 6 and 35) is an area where national governments have decided on quite diverse regulations. In some states, this issue has yet to be approached at all (e.g. Austria, France and Poland; Bauer et al., Citation2011; CFFR, Citation2015). Iceland is still in the process of deliberating whether the standard on consolidation is to be implemented (Iceland #4).

Time lag of national implementation: In some countries, there is a time lag between the IPSASB issuing a new IPSAS and its implementation by a certain government: The number of standards implemented still mirror the status quo of the IPSAS by the decision time (25 in Spain; Jorge et al., Citation2019, and 32 in Austria; MoF Austria, Citation2013). In this context, one interviewee from Austria explained:

The public administration did not receive an order by Parliament or by the Cabinet to continuously implement new IPSASs. (Austria #2 [translated by the authors])

Simplification: In some countries, the presentation of the financial statements differs from the regulation in IPSAS 1. For example, in Poland, the presentation of financial statements (IPSAS 1) and cash flow statements (IPSAS 2) is less detailed than prescribed by the IPSAS (CFFR, Citation2015). In some case, the recognition of financial instruments follows more simplified rules. For example, Austria implemented IPSAS 15 and 29 only in part: i.e. they adapted these standards (MoF Austria, Citation2013).

Measurement and consolidation methods: A number of countries follow different measurement principles for Property, Plant and Equipment (IPSAS 17), e.g. by emphasizing the “cost principle” for asset valuation over the “fair value” principle (e.g. France or Sweden; see ESV, Citation2013). Furthermore, Switzerland deviates regarding the capitalization of some types of military equipment (Federal Council Switzerland, Citation2018).

Diverging consolidation methods are used (full, proportional and at equity). These results are in line with the recent study on consolidation methods and approaches in OECD countries (Bergmann et al., Citation2016) showing significant national deviations from IPSAS 6 and 35.

Accounting basis (cash vs accrual): Switzerland is an example of this type of deviation. Contrary to IPSAS 1, it recognizes a particular type of tax retention concerning taxpayers in European Union countries, by following the cash principle (Federal Council Switzerland, Citation2018).

Alternative formats of presentation: Finally, a more particular issue is the disclosure of provisions and employee benefits (IPSAS 39, superseded IPSAS 25), which in some countries is not presented in the balance sheet but in its appendices or in separate notes (e.g. in Switzerland for pensions).

5. Expressed reasons for deviations and interpretation

5.1. Deviations

Moving to the heart of our investigation, a plethora of reasons for deviations from IPSAS as issued by the IPSASB (partial adoption, adaptation and non-adoption) came to the fore. We will summarize these in the following paragraphs:

Issues covered in specific IPSAS are not relevant: Regarding a partial adoption of particular IPSAS, actors point to the fact that certain issues regulated in an IPSAS are not material in a particular country, making an implementation unnecessary. For example, IPSAS 10, 11, 15 and 16 are not regarded as relevant for Iceland (IMF, Citation2014). Similarly, Bauer et al. hold for Austria that IPSAS 10, 11 and 16 “are not included into the central government accounting due to a lack of relevance” (Citation2011, p. 13 [translated by the authors]; see also MoF Austria, Citation2013). The same is true in the UK for IPSAS 10 (FRAB, Citation2017).

IPSAS offer many options: Other critical comments focus on the accounting options that are offered by several IPSAS, e.g. concerning disclosure or valuation regulations, because such accounting options are seen as a hindering factor for comparability. Against this background, some national regulations offer fewer alternatives (e.g. in France or Sweden; CNOCP, Citation2014; ESV, Citation2013).

IPSAS were perceived as premature at the time of decision-making: Further, some countries take a critical position regarding cases where the IPSAS had not (yet) offered appropriate solutions for the public sector when transition to accrual accounting occurred. A reason for leaning towards IFRS instead of IPSAS is that national standard formulation had already started in a period when IPSAS were still considered premature, e.g. in the UK:

The French standard setting board, for instance, points to heritage assets, transfer expenses or social benefits, where appropriate IPSAS are considered absent:However, there was also little appetite for adopting dedicated public sector accounting standards (which were arguably in their infancy at the stage when a decision had to be made which standards to adopt). (UK #1)

Also:IPSAS do not cover the specific transactions carried out by public entities (in particular they do not address the accounting treatment of social benefits, which make up more than half of general government spending in France). The standards are still incomplete on points of crucial importance to the public sector. (CNOCP, Citation2012, p. 15; see also Biondi, Citation2016)

Given these perceived shortcomings, IPSAS were perceived to serve as one but not the only point of reference for developing national standards (see also CNOCP, Citation2018).Three further matters were also identified as topics that call for standards: entity combinations in the public sector, historical and cultural assets and emission trading schemes. (CNOCP, Citation2014, p. 5)

In Sweden, regarding their already quite sophisticated national rules, the National Financial Management Authority (ESV) argued in a report that “Central Government accounting rules are well in front in an international context” (ESV, Citation2013, p. 7).

Competing standards with regard to reporting: The IPSAS have to be seen in the light of other available “competing” reporting standards, one of which would be the IFRS, which were chosen in the UK instead of IPSAS:

The European Public Sector Accounting Standards (EPSAS) are a project of Eurostat, the statistical office of the European Union (Polzer & Reichard, Citation2020) and are expected to become another potential “competing” set of standards in the future. The development of EPSAS has made progress over recent years (for more details, see Caruana et al., Citation2019; Polzer & Reichard, Citation2020). The EPSAS are supposed to be implemented on a mandatory basis and differ in this regard from the IPSAS. Accordingly, actors expressed concerns about having to implement yet another accounting reform in the near future (e.g. Austria #2, Poland #4):Why choose IFRS instead of IPSAS? First, I think it is important to recall that UK PLCs [public limited companies] had switched to IFRS two years before – there would be many who would wish to see the same standards underlie public sector accounts – effectively some sort of sector neutrality. (UK #3)

Poland supports the idea of increased transparency of the public finance, but shares the doubts on whether EPSAS and IPSAS in the proposed form by the European Commission and Eurostat are the best way forward. (Poland #4)

Further reporting requirements: Moreover, actors refer to other regulations that need to be obeyed (e.g. statistical reporting within the scope of the ESA) and which impede the application of certain IPSAS:

One example of this are pension liabilities: “In the light of harmonization with “Maastricht” reporting, pension liabilities for civil servants according to IPSAS 25 are not included” (Bauer et al., Citation2011, p. 13 [translated by the authors]; see also SAI Austria, Citation2019).The “Maastricht results”, i.e. reporting according to the ESA 2010 rules, are very present in the public dialogue; also, the outcome performance indicators of the MoF are based on the ESA 2010 rules. (Austria #2 [translated by the authors])

Concerns about the value added compared with the implementation costs: Another often expressed reason is that the full adoption of IPSAS is considered too costly or too time-consuming (e.g. regarding data collection or valuation of infrastructure assets). For example, the Swedish ESV (Citation2013, p. 9) is also still quite sceptical towards the full introduction of IPSAS for economic reasons:

And:The conclusion of ESV is that a full implementation of IPSAS would probably be costly and time-consuming […].

The Swedish agency introduces a cost–benefit perspective for potential users of accounting information and is of the opinion that:With a possible full introduction of IPSAS the assessment of ESV is however that the costs would be comparably extensive. Additional resources would be required both at ESV and the Ministry of Finance, and probably also at the agencies. (ibid., p. 85)

Similarly, IPSAS 23 (Revenue and Non-Exchange Expenses) was only partly implemented in Austria, as the national “regulation deviates from the accrual principle required by IPSAS 23; it was chosen, however, for reasons of administrative simplification” (Bauer et al., Citation2011, p. 13 [translated by the authors]). A similar reasoning was also made for the area of disclosure of financial instruments (IPSAS 30), where simplified reporting is performed, also for cost–benefit reasons (SAI Austria, Citation2019).IPSAS make very heavy demands on supplementary disclosures. ESV considers these demands in many cases being too far-reaching than would be interesting for the Government and the Parliament as users of financial information and as basis for performance management (ibid, p. 20).

Some governments refrained from rolling out the complete set of IPSAS to all government entities because of value-for-money considerations (e.g. in Iceland or Estonia). In the Icelandic MoF, some concerns were raised about the value added, for example with respect to consolidation (IPSAS 6), given the relatively small budget and assets of central government agencies (Iceland #4).

Keeping reform changes to a minimum: In Austria, it was argued that the changes in the accounting system still need time to bed down:

In Iceland, it was also pointed out that the implementation of IPSAS is a time-consuming exercise:The use of accrual results still has to be learnt by employees in the MoF, line ministries and parliament; at the moment, accrual accounting primarily creates more effort in the administration. (Austria #2 [translated by the authors])

We are at the end of the three year implementation period and the accounts for 2019 shall, according to law, be in full compliance with IPSAS. However it is clear that the implementation of some standards will be postponed for some time. (Iceland #3)

Accounting traditions: Finally, regarding adaptation of standards, IPSAS are perceived to conflict with more appreciated standards, which often are based on long-established accounting traditions (e.g. the prudence principle in Continental European accounting; Lorson & Haustein, Citation2019). This led, for instance, to the modification of the fair value principle, as emphasized by the IPSASB (e.g. in Switzerland).

5.2. Discussion of results

Our analytical framework (), on the one hand, helps to identify the factors and institutional pressures contributing to the spread of IPSAS (Brunsson et al., Citation2012; Tolbert & Zucker, Citation1983). On the other hand, the framework facilitates the unveiling of the filters of national structural and contextual constraints (Meyer, Citation2014), in order to understand the diverging responses and variations in countries’ practices (Albu et al., Citation2014; Caruana, Citation2019; Lounsbury, Citation2008) – i.e. partial adoption, adaptation and non-adoption of standards. As previously stated, adoption of the IPSAS is not mandatory (IPSASB, Citation2020; Oulasvirta & Bailey, Citation2016). Therefore, our empirical material differs from research examining practice variation when imposed accounting tools and standards are implemented in organizations (e.g. Adhikari et al., Citation2013).

Regarding isomorphic pressures, in line with the extant literature, we found in our empirical analysis both isomorphic pressures and functional narratives for the implementation of IPSAS across countries, in the first place. Coercive and mimetic pressures (Jorge et al., Citation2020; Tagesson, Citation2015) were identified, i.e. the IPSAS either have been pushed by international organizations (such as the IMF in Iceland, in reacting to the financial crisis) or serve as an “orientation device” for issues where the IFRS remain silent (in UK; CIPFA, Citation2012). We also found a number of functionalist arguments advanced, for example by professional accounting bodies:

IPSAS are important in promoting transparency and thereby curbing fraud and corruption. (ACCA, Citation2017, p. 5)

Financial statements prepared in accordance with IPSAS provide confidence and comparability for investors at an international level. These investments potentially create spin-off benefits for the broader economy in terms of jobs, welfare and societal improvement. (ibid.)

The role of transnational standards. Revisiting Djelic and Quack’s (Citation2008) notion that standards encompass more and more “transnational” elements, the IPSAS can be seen as an attempt at setting transnational accounting standards that impacts on the accounting rules of national and international PSOs. First, we have to note that IPSAS compliance is a “dual moving target”: On the one side, IPSAS are under continuous development, as new standards are continuously decided and published by the IPSASB, which might lead to growing discrepancies between IPSAS and national regulations over time (see EY, Citation2013 for the similar situation between IFRS and IPSAS). On the other side, national standards are also in continuous development, as our observations, e.g. in France and Sweden, show. Therefore, it can be concluded that one of the reasons for the non-adoption of standards might simply be time lags, i.e. that two regulations develop at “different speeds”.

In line with Brunsson et al.’s finding, according to which standards “cannot cater to the idiosyncrasies of the organizations to which they apply” (Citation2012, p. 621), we observed that, in a number of countries, e.g. France, Poland, Sweden – and even Estonia and Switzerland, which show high compliance with IPSAS – IPSAS were considered too detailed and/or offering too many accounting options with respect to the national context. Consequently, simplifications were made. This reflects current discussions that there are several (perhaps too many) measurement options offered by the IPSAS (EY, Citation2016; PwC, Citation2014). Given this, standards are adapted to the national context, and processes of translation and manifestation of “glocalization” can be observed (Baskerville & Grossi, Citation2019). Yet, these developments can be seen as running counter to comparability – one of the central objectives of the IPSAS project (Jorge et al., Citation2019; Mattei et al., Citation2020).

Competition between alternative sets of standards. The plurality of (accounting) standards and the relationship between them (Djelic & Den Hond, Citation2014) became evident when looking at how the IPSAS relate to other frameworks for public sector accounting and reporting (e.g. the IFRS or planned EPSAS). The relative infancy of the IPSAS (see above) was one of the main reasons why the UK decided to support a sector-neutrality approach and implemented IFRS instead. When Austria decided to implement the IPSAS, this process “stopped” with IPSAS 32 – one reason being that Austria is observing how the EPSAS as a set of potentially alternative accounting standards will develop.

Indeed, under the situation of “regulatory competition” (Jamal & Sunder, Citation2014), different standards would have to be followed, and therefore IPSAS were adapted to match existing regulations. Such a reasoning was made, for example, by Austrian actors, who argued that the new accounting rules would still have to fit ESA standards in order to fulfil EU reporting requirements. We therefore find evidence for Brunsson et al.’s remark that “if there are competing standards, adopters are likely to select the one that is least demanding or fits best with their existing practices” (Citation2012, p. 626) – especially when IPSAS are to be implemented on a voluntary basis. However, extending their point, instead of a choice among different sets of standards, we rather observe forms of “glocalization”, where particular IPSAS are adapted to the local context (e.g. through simplification), or where some standards are omitted.

Administrative and accounting traditions. A further often-mentioned reason for deviating from IPSAS is the concern of governments or standard setters to be independent from international regulations – or at least to demonstrate such independence and autonomy. France is such a case, where authorities continuously demonstrate formal independence from IPSAS (e.g. in consultations: CNOCP, Citation2012, Citation2014 and Citation2018), although the implicit compliance with IPSAS is astonishingly high (see ).

Also, the commitment to long-lasting and deeply rooted national accounting traditions (Anessi-Pessina & Cantù, Citation2017; Nobes, Citation2013), which emphasize certain principles like prudence or cautiousness as dominant valuation rules for assets or inventories, might be in conflict with certain IPSAS, for instance with the principle of “true and fair value”. As discussed earlier, critical observers, e.g. in France or Sweden (but even in Switzerland), worry about the relaxation of well-established regulations and an ostensible overvaluation of public assets. This rhetorical distance of the French standard setters and government from IPSAS can be interpreted as a signal of self-reliance. This struggle between national and international standards resonates with Ahrne and Brunsson’s finding (Citation2014, p. 40), according to which “[i]n some contexts and under some circumstances, foreignness generates a negative value, whereas local innovations trigger greater prestige”. The authors refer to this as the “not-invented-here syndrome”.

Next, specific administrative (Meyer & Hammerschmid, Citation2010) and accounting traditions (Anessi-Pessina & Cantù, Citation2017) certainly have some influence on the position of government authorities regarding IPSAS. If we look at France again, we observe a very distinct public service orientation (appreciation of the French “service public” particularities, CNOCP, Citation2014) and also a long-standing cash accounting tradition, which was only transcended a few years ago. The described distance from IPSAS is therefore not really surprising. Taking Switzerland as an opposite case, we look at a society with pragmatic attitudes and more than 40 years’ accrual experience in public sector accounting. In such a case, a closeness to IPSAS with their business sector focus is quite predictable (particularly, if one of the major promotors of IPSAS is influential in the Swiss government accounting realm). Similarly, the UK, as one of the NPM pioneers, opted for IFRS, which have been claimed to bring “the governments benefits in consistency and comparability between financial reports in the global economy and to follow private sector best practice” (Aggestam-Pontoppidan, Citation2011, p. 31).

Sweden and France have both incorporated a specific standard setting board for government accounting (ESV and CNOCP, respectively). In both cases, however, the standards are translated into legal ordinances or directives. On the contrary, in the former socialistic countries (e.g. Estonia and Poland), the influence of private sector accounting was stronger, and both countries established common national accounting standards issued by a national standard setter and valid for both the public and private sectors (sector neutrality).

In the UK, governmental accounting depends on international private business accounting principles (IFRS), with some adaptations made by the Treasury in its FReM. There is a highly developed accounting standard setting infrastructure in place that also has to some extent a quasi-regulatory function for the public sector. Although not relying on a specific public sector board, the Financial Reporting Advisory Board (FRAB) considers proposed changes to accounting policy and practice, constraining to some extent the freedoms of the UK government.

Finally, deeply rooted legal patterns of public financial management also influence somewhat the determination of accounting principles in the reviewed countries: Austria and Switzerland, the two countries with a Germanic administrative tradition, have not established a standard setting board. Instead, both regulate their public sector accounting principles in legal acts.

Overall, our cases are manifestations of what happens when global standards “meet” the local context – against the backdrop of the non-mandatory character of IPSAS’ implementation. The insights gained from the analyses of countries allowed the taxonomy that was developed from the literature review to be refined (Section 2.1). In particular, our results demonstrated how selected European countries deal with the concern that IPSAS do not cater adequately for the circumstances in the public sector (“publicness”). We pointed to a number of contradictions between national accounting traditions and IPSAS, as well as fears about a loss of national sovereignty in setting accounting standards. In addition, cost–benefit considerations play an important role. Finally, deviations between IPSAS and national standards are to some extent unavoidable, as both the IPSAS and the national standards are in continuous development (“dual moving targets”).

The research highlights the complexities involved in attempts to achieve inter-country comparability (e.g. for rating agencies). Taken together, these points illustrate the “filters” (Meyer, Citation2014) that are constraining the adoption of IPSAS in the unaltered form, leading eventually to practice variations (Lounsbury, Citation2008).

6. Conclusions

The aims of this paper were twofold: On the one hand, we sought to present an empirical picture of the deviations of national accounting rules from IPSAS, as most extant research treated IPSAS adoption as binary. On the other hand, we aimed to analyse and structure the reasons for deviations expressed by various actors. More specifically, we investigated different national reactions to IPSAS across the spectrum of unaltered adoption, adaptation and non-adoption. Focusing on the central government level in nine countries with different administrative traditions, which have implemented IPSAS to different degrees, we found considerable diversity in translated accounting standards. Actors advanced a plethora of reasons for their decision to deviate from IPSAS as issued by the IPSASB. As a consequence of deviations, there is a threat that the comparability of financial reporting between entities will be undermined, with the risk of leaving the full reform potential unrealized (Mattei et al., Citation2020).

This paper adds to the literature on harmonization in public sector accounting. First, we contribute empirically to the growing literature on the harmonization of national accounting standards towards IPSAS, by showing the reasons of various national actors from nine European countries for deviating from implementing unaltered IPSAS. Our more nuanced perspective on the “shades of grey” sheds greater light on the different forms of deviations from IPSAS and on governments’ underlying reasons. We analyse standard setting against the backdrop of “dual moving targets”, i.e. with both IPSAS and national standards continuously being further developed.

Second, we confirm Brunsson et al.’s (Citation2012) observation that, if adopters are faced with multiple standards, they possibly pick the one that aligns best with existing practices. Many of the arguments for adopting or aligning their financial reporting with IPSAS were connected to maintaining legitimacy (e.g. Tagesson, Citation2015). Further, we show that, instead of a choice among different existing standards, a form of “glocalization” of standards is also possible (Baskerville & Grossi, Citation2019), where IPSAS are adapted with a high degree of flexibility to the national context and needs during translation.

Taking the objectives of IPSAS (fulfilling specific information needs, improving the transparency and reliability of public accounts and facilitating the consolidation of annual accounts) as a benchmark, we may ask to what extent “glocalization” of standards undermines these objectives and restricts comparability. How much “deviation” is possible until there is again – as before – non-comparability among PSOs? This question of “one size does not fit all” (Tucker et al., Citation2019) is relevant to practitioners such as regulators or policy makers and needs to be addressed by further research.

Our research approach has several limitations, some of which provide further potential avenues for future research. First, with our sample of nine countries, we do not claim representativeness. This is also because this research provides a “snapshot”, with IPSAS and national legislations constantly evolving. We therefore call for the scope of our study to be updated and extended. Second, we focused on the deviations of accounting regulations as they have been decided by national governments, therefore excluding the stages before and after, i.e. the debate about possible deviations and deviations emerging in the “daily use” of translated IPSAS. Indeed, this seems to be particularly relevant in standardization, as Brunsson et al. (Citation2012, p. 622) found that “instead of changing its practices, an organization represents them so that they appear to be in line with a particular standard”. We therefore call for more in-depth case studies on the translation of accounting standards (such as those by Adhikari et al., Citation2019; Argento et al., Citation2018; Goddard et al., Citation2016). Third, differences do not only exist between countries but also within countries, when it comes to regional and local governments. Thus, next to an extension of the empirical field in terms of breadth, also increasing the depth (e.g. a central/local government perspective) could be an avenue for future research. Finally, deviance and responses to deviance could be analysed, looking at “the ways in which deviance is constructed and managed through interpersonal, organizational and state processes” (Walker, Citation2016, p. 46). Here, the role of individual and organizational actors in promoting accounting changes could be investigated (Argento et al., Citation2018). To conclude, taking a more complete picture of the IPSAS implementation might not actually lead to more complete answers, but it could lead to a situation where we are able to ask the proverbial “better questions” relevant to public sector accounting change.

Acknowledgements

We thank the participants of the conferences and workshops where this work was presented (such as at the European Accounting Association Conference 2019 and the Asia-Pacific Interdisciplinary Research in Accounting Conference 2019), for their constructive comments and feedback. We are also grateful to the two anonymous reviewers and the editors of Accounting Forum for their thoughtful comments on our manuscript. As always, all remaining errors and omissions are entirely our own.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 See Baskerville and Grossi’s (Citation2019) study regarding applying the concept of glocalization to public sector accounting.

2 Detailed reports for each country are available from the authors upon request.

References

- ACCA. (2017). IPSAS implementation: Current status and challenges.

- ACCA & IFAC. (2020). Is cash still king? Maximising the benefits of accrual information in the public sector. ACCA.

- Ada, S. S., & Christiaens, J. (2018). The magic shoes of IPSAS: Will they fit Turkey? Transylvanian Review of Administrative Sciences, 54(1), 5–21. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.24193/tras.54E.1

- Adhikari, P., Kuruppu, C., & Matilal, S. (2013). Dissemination and institutionalization of public sector accounting reforms in less developed countries: A comparative study of the Nepalese and Sri Lankan central governments. Accounting Forum, 37(3), 213–230. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.accfor.2013.01.001

- Adhikari, P., Kuruppu, C., Ouda, H., Grossi, G., & Ambalangodage, D. (2019). Unintended consequences in implementing public sector accounting reforms in emerging economies: Evidence from Egypt, Nepal and Sri Lanka. International Review of Administrative Sciences. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0020852319864156

- Aggestam-Pontoppidan, C. (2011). Selecting international standards for accrual-based accounting in the public sector: IPSAS or IFRS? Journal of Government Financial Management, 60(3), 28–32.

- Aggestam-Pontoppidan, C., & Andernack, I. (2016). Interpretation and application of IPSAS. Wiley.

- Ahrne, G., & Brunsson, N. (2014). The travel of organization. In G. S. Drori, M. A. Höllerer, & P. Walgenbach (Eds.), Global themes and local variations in organization and management: Perspectives on glocalization (pp. 39–51). Routledge.

- Albu, C. N., Albu, N., & Alexander, D. (2014). When global accounting standards meet the local context – insights from an emerging economy. Critical Perspectives on Accounting, 25(6), 489–510. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpa.2013.03.005

- Albu, N., Albu, C. N., & Gray, S. J. (2020). Institutional factors and the impact of international financial reporting standards: The central and Eastern European experience. Accounting Forum, 44(3), 184–214. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/01559982.2019.1701793

- Anessi-Pessina, E., & Cantù, E. (2017). Multiple logics and accounting mutations in the Italian national health service. Accounting Forum, 41(1), 8–27. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.accfor.2017.03.001

- Ansari, S. M., Fiss, P. C., & Zajac, E. J. (2010). Made to fit: How practices vary as they diffuse. Academy of Management Review, 35(1), 67–92. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.35.1.zok67

- Argento, D., Peda, P., & Grossi, G. (2018). The enabling role of institutional entrepreneurs in the adoption of IPSAS within a transitional economy: The case of Estonia. Public Administration and Development, 38(1), 39–49. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/pad.1819

- Baskerville, R., & Grossi, G. (2019). Glocalization of accounting standards: Observations on neo-institutionalism of IPSAS. Public Money & Management, 39(2), 95–103. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/09540962.2019.1580894

- Bauer, G., Pasterniak, A., & Seiwald, J. (2011). Österreich und die IPSAS. Die inhaltliche Fundierung des Rechnungswesens des Bundes. Das öffentliche Haushaltswesen in Österreich, 52(1–3), 5–13.

- Bergmann, A., Grossi, G., Rauskala, I., & Fuchs, S. (2016). Consolidation in the public sector: Methods and approaches in organisation for economic Co-operation and development countries. International Review of Administrative Sciences, 82(4), 763–783. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0020852315576713

- Biondi, Y. (2016). Accounting representations of public debt and deficits in European central government accounts: An exploration of anomalies and contradictions. Accounting Forum, 40(3), 205–219. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.accfor.2016.05.003

- Botzem, S. (2012). The politics of accounting regulation. Organizing transnational standard setting in financial reporting. Edward Elgar.

- Brunsson, N., & Jacobsson, B. (2002). Following standards. In N. Brunsson & B. Jacobsson (Eds.), A world of standards (pp. 127–137). OUP.

- Brunsson, N., Rasche, A., & Seidl, D. (2012). The dynamics of standardization: Three perspectives on standards in organization studies. Organization Studies, 33(5–6), 613–632. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0170840612450120

- Caperchione, E. (2015). Standard setting in the public sector: State of the art. In I. Brusca, E. Caperchione, S. Cohen, & F. Manes Rossi (Eds.), Public sector accounting and auditing in Europe. The challenge of harmonization (pp. 1–11). Palgrave.

- Caperchione, E., Demirag, I., & Grossi, G. (2017). Public sector reforms and public private partnerships: Overview and research agenda. Accounting Forum, 41(1), 1–7. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.accfor.2017.01.003

- Caruana, J. (2019). Shades of governmental financial reporting with a national accounting twist. Accounting Forum, 40(3), 153–165. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.accfor.2016.06.002

- Caruana, J., Dabbicco, G., Jorge, S., & Jesus, M. A. (2019). The development of EPSAS: Contributions from the literature. Accounting in Europe, 16(2), 146–176. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/17449480.2019.1624924

- CFFR. (2015). A comparison of Polish public sector GAAP with IPSAS. Centre for Financial Reporting Reform.

- Christiaens, J., & Neyt, S. (2015). IPSAS. In T. Budding, G. Grossi, & T. Tagesson (Eds.), Public sector accounting (pp. 23–62). Routledge.

- Christiaens, J., Vanhee, C., Manes Rossi, F., Aversano, N., & Van Cauwenberge, P. (2015). The effect of IPSAS on reforming governmental financial reporting: An international comparison. International Review of Administrative Sciences, 81(1), 158–177. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0020852314546580

- Chytis, E., Georgopoulos, I., Tasios, S., & Vrodou, I. (2020). Accounting reform and IPSAS adoption in Greece. European Research Studies Journal, 23(4), 165–184. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.35808/ersj/1678

- CIPFA. (2012). Assessment of the suitability of the International Public Sector Accounting Standards (IPSAS) for the member states.

- CNOCP. (2012). Response to eurostat.

- CNOCP. (2014). Réponse du conseil de normalisation des comptes publics.

- CNOCP. (2018). Central government accounting standards.

- Cordery, C. J., Crawford, L., Breen, O. B., & Morgan, G. G. (2019). International practices, beliefs and values in not-for-profit financial reporting. Accounting Forum, 43(1), 16–41. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/01559982.2019.1589906

- Dahlgren, J., & Nilsson, S.-A. (2012). Can translations achieve comparability? The case of translating IFRSs into Swedish. Accounting in Europe, 9(1), 39–59. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/17449480.2012.664391

- Djelic, M. L., & Den Hond, F. (2014). Introduction: Multiplicity and plurality in the world of standards. Symposium on multiplicity and plurality in the world of standards. Business and Politics, 16(1), 67–77. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1515/bap-2013-0034

- Djelic, M. L., & Quack, S. (2008). Institutions and transnationalisation. In R. Greenwood, C. Oliver, K. Sahlin, & R. Suddaby (Eds.), The SAGE handbook of organizational institutionalism (pp. 299–323). Sage.

- Dolowitz, D., & Marsh, D. (2000). Learning from abroad: The role of policy transfer in contemporary policy-making. Governance, 13(1), 5–23. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/0952-1895.00121

- Doupnik, T., & Perera, H. (2012). International accounting. McGraw-Hill.

- Drori, G. S., Höllerer, M. A., & Walgenbach, P. (2014). Unpacking the glocalization of organization: From term, to theory, to analysis. European Journal of Cultural and Political Sociology, 1(1), 85–99. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/23254823.2014.904205

- ESV. (2013). Report. Comparison with international accounting standards. Ekonomistyrningsverket.

- European Commission. (2013). Commission staff working document SWD(2013) 57 final.

- Evans, L., Baskerville, R., & Nara, K. (2015). Colliding worlds: Issues relating to language translation in accounting and some lessons from other disciplines. Abacus, 51(1), 1–36. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/abac.12040

- EY. (2013). A snapshot of GAAP differences between IPSAS and IFRS. EYGM.

- EY. (2016). Approach for narrowing down of options within IPSAS. EYGM.

- Federal Council Switzerland. (2018). Financial Budget ordinance (finanzhaushaltverordnung/FHV). Federal Council.

- FRAB. (2017). FRAB 128 (06) annex 2 2017/18 code.

- Fuertes, I. (2008). Towards harmonization or standardization in governmental accounting? The International public Sector Accounting Standards board experience. Journal of Comparative Policy Analysis, 10(4), 327–345. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13876980802468766

- Goddard, A., Assad, M., Issa, S., Malagila, J., & Mkasiwa, T. A. (2016). The two publics and institutional theory–A study of public sector accounting in Tanzania. Critical Perspectives on Accounting, 40(1), 8–25. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpa.2015.02.002

- Grossi, G., & Steccolini, I. (2015). Pursuing private or public accountability in the public sector? Applying IPSASs to define the reporting entity in municipal consolidation. International Journal of Public Administration, 38(4), 325–334. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/01900692.2015.1001239

- Hopper, T., & Hoque, Z. (2018). Triangulation approaches to accounting research. In Z. Hoque (Ed.), Methodological issues in accounting research: Theories and methods (pp. 562–572). Spiramus.

- IMF. (2014). IPSAS in Iceland–towards enhanced fiscal transparency.

- IPSASB. (2020). Handbook of international public sector accounting pronouncements. Volume I. IFAC.

- Jamal, K., & Sunder, S. (2014). Monopoly versus competition in setting accounting standards. Abacus, 50(4), 369–385. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/abac.12034

- Jensen, G. (2020). The IPSASB’s recent strategies: Opportunities for academics and standard-setters. Journal of Public Budgeting, Accounting & Financial Management, 32(3), 315–319. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/JPBAFM-04-2020-0050

- Jeppesen, K. K. (2010). Strategies for dealing with standard-setting resistance. Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, 23(2), 175–200. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/09513571011023183

- Jorge, S., Brusca, I., & Nogueira, S. P. (2019). Translating IPSAS into national standards: An illustrative comparison between Spain and Portugal. Journal of Comparative Policy Analysis: Research and Practice, 21(5), 445–462. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13876988.2019.1579976

- Jorge, S., Nogueira, S. P., & Ribeiro, N. (2020). The institutionalization of public sector accounting reforms: The role of pilot entities. Journal of Public Budgeting, Accounting & Financial Management 33, 114–137. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/JPBAFM-08-2019-0125

- Krishnan, S. R. (2018). Influence of transnational economic alliances on the IFRS convergence decision in India – institutional perspectives. Accounting Forum, 42(4), 309–327. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.accfor.2018.09.002

- Lorson, P., & Haustein, E. (2019). Debate: On the role of prudence in public sector accounting. Public Money & Management, 39(6), 389–390. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/09540962.2019.1583907

- Lounsbury, M. (2008). Institutional rationality and practice variation: New directions in the institutional analysis of practice. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 33(4–5), 349–361. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aos.2007.04.001

- Manes Rossi, F., Cohen, S., Caperchione, E., & Brusca, I. (2016). Harmonizing public sector accounting in Europe: Thinking out of the box. Public Money & Management, 36(3), 189–196. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/09540962.2016.1133976

- Mattei, G., Jorge, S., & Grandis, F. G. (2020). Comparability in IPSASs: Lessons to be learned for the European standards. Accounting in Europe, 17(2), 158–182. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/17449480.2020.1742362

- Meyer, R. E. (2014). ‘Re-localization’ as micro-mobilization of consent and legitimacy. In G. S. Drori, M. A. Höllerer, & P. Walgenbach (Eds.), Global themes and local variations in organization and management: Perspectives on glocalization (pp. 79–89). Routledge.

- Meyer, R. E., & Hammerschmid, G. (2010). The degree of decentralization and individual decision making in central government human resource management: A European comparative perspective. Public Administration, 88(2), 455–478. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9299.2009.01798.x

- MoF Austria. (2013). Geschäftsbericht. Eröffnungsbilanz des Bundes zum 1. Jänner 2013. Austrian Ministry for Finance.

- Nobes, C. (2013). The continued survival of international differences under IFRS. Accounting and Business Research, 43(2), 83–111. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/00014788.2013.770644

- Nobes, C., & Parker, R. (2016). Comparative international accounting. Pearson.

- Oulasvirta, L. (2014). The reluctance of a developed country to choose International Public Sector Accounting Standards of the IFAC. A critical case study. Critical Perspectives on Accounting, 25(3), 272–285. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpa.2012.12.001

- Oulasvirta, L. O., & Bailey, S. J. (2016). Evolution of EU public sector financial accounting standardisation: Critical events that opened the window for attempted policy change. Journal of European Integration, 38(6), 653–669. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/07036337.2016.1177043

- Patton, M. Q. (2015). Qualitative research & evaluation methods. Sage.

- Polzer, T., Gårseth-Nesbakk, L., & Adhikari, P. (2020). “Does your walk match your talk?” Analyzing IPSASs diffusion in developing and developed countries. International Journal of Public Sector Management, 33(2/3), 117–139. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/IJPSM-03-2019-0071

- Polzer, T., & Reichard, C. (2020). IPSAS for European Union member states as starting points for EPSAS. International Journal of Public Sector Management, 33(2/3), 247–264. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/IJPSM-12-2018-0276

- PwC. (2014). Collection of information related to the potential impact, including costs, of implementing accrual accounting in the public sector and technical analysis of the suitability of individual IPSAS standards. PricewaterhouseCoopers.

- PwC. (2019). Accounting maturity update. 2019 preliminary results. PricewaterhouseCoopers.

- Roberts, C., Weetman, P., & Gordon, P. (2005). International financial reporting. A comparative approach. Pearson.

- Rogers, E. M. (2003). Diffusion of innovations. Free Press.

- SAI Austria. (2019). Bundesrechnungsabschluss für das Jahr 2018. Textteil Band 1. Rechnungshof Österreich.

- Schmidthuber, L., Hilgers, D., & Hofmann, S. (2020). International Public Sector Accounting Standards (IPSASs): A systematic literature review and future research agenda. Financial Accountability & Management, https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/faam.12265

- Seawright, J., & Gerring, J. (2008). Case selection techniques in case study research. A menu of qualitative and quantitative options. Political Research Quarterly, 61(2), 294–308. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1065912907313077

- Sellami, Y. M., & Gafsi, Y. (2019). Institutional and economic factors affecting the adoption of International Public Sector Accounting standards. International Journal of Public Administration, 42(2), 119–131. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/01900692.2017.1405444

- Tagesson, T. (2015). Accounting reforms, standard setting and compliance. In T. Budding, G. Grossi, & T. Tagesson (Eds.), Public sector accounting (pp. 8–22). Routledge.

- Tolbert, P. S., & Zucker, L. G. (1983). Institutional sources of change in the formal structure of organizations: The diffusion of civil service reform, 1880–1935. Administrative Science Quarterly, 28(1), 22–39. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.2307/2392383

- Toudas, K., Poutos, E., & Balios, D. (2013). Concept, regulations and institutional issues of IPSAS: A critical review. European Journal of Business and Social Sciences, 2(1), 43–54.

- Tucker, B., Ferry, L., Steccolini, I., & Saliterer, I. (2019). Debate: The practical relevance of public sector accounting research; time to take a stand—A response to van Helden. Public Money & Management, 40(1), 5–7. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/09540962.2019.1660098

- Walker, S. P. (2016). Revisiting the roles of accounting in society. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 49(1), 41–50. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aos.2015.11.007