ABSTRACT

Employing Bourdieu’s practice theory, this paper explores factors that influence corporate executives’ behaviour towards corporate governance regulation. Drawing insights from a weak institutional environment (Nigeria) and relying on a qualitative research methodology (semi-structured interviews with 31 executives), this research uncovers how nine nuanced situational and cultural field factors determine executives’ regulatory response to the severity of punishment, the certainty of penalties, and the cost–benefit compliance considerations. The study further explains how sequential rationalisation between the severity and certainty of punishment contributes to the regulatory apathy that executives exhibit. Theoretically, this study demonstrates how practice theory components (habitus, capital, and field) blend to establish executives’ regulatory practice.

ACCEPTED BY:

1. Introduction

The corporate governance literature suggests that national laws, capital market requirements, and firm-level decisions are central to corporate governance systems (Filatotchev et al., Citation2013). Governance mechanisms across countries are embedded in their business systems and are influenced by political, social, and legal macro-institutions (Armitage et al., Citation2017). In this regard, weak institutional arrangements in developing economies frustrate their corporate governance effectiveness (Adegbite, Citation2010; Kumar & Zattoni, Citation2016; Yoshikawa & Rasheed, Citation2009).

While a battery of techniques has been proposed to enhance corporate governance in developing economies, effective regulation remains the central focus (Kirkbride & Letza, Citation2004; Siddiqui, Citation2010). For instance, scholars examine rules versus principles-based approaches to corporate governance regulation (Arjoon, Citation2006; Black et al., Citation2007; Nakpodia et al., Citation2018), emphasising their benefits and drawbacks as well as the rationale for their adoption in specific institutional contexts. Other studies (e.g. Judge et al., Citation2008) examine civil and common law dichotomies. Yet, an under-researched but important area of the corporate governance regulation literature relates to executives’ regulatory behaviour. This paper addresses this gap.

The regulatory system is crucial in addressing weak corporate governance by corporate agents (e.g. directors, regulators). While prior studies offer useful theoretical underpinnings within this research space, they do not account for what informs agents’ disposition to regulations (Aguilera et al., Citation2018). For example, the agency theory assumes that agents are typically rational (Fama, Citation1980; Shleifer & Vishny, Citation1997), but cognitive psychology and behavioural theorists show that judgement, decision-making, and behaviour are not entirely driven by logical reasoning (Blanchette & Richards, Citation2010; Marnet, Citation2005). Instead, they are characterised by several heuristics and cognitive biases (Marnet, Citation2005). As such, our study relies on a theoretical framing (Bourdieu’s practice theory) that accommodates underlying social mechanisms, which goes beyond legal descriptions to explain agents’ interactions with their socio-cultural environments.Footnote1

We draw on Bourdieu’s (Citation1977) practice theory to explore how social realities influence executives’ attitudes to corporate governance regulation. We acknowledge that executives have preferences and that their corporate choices/decisions are affected by these preferences (Levin & Milgrom, Citation2004). We also note that conflict in economic choices and self-interests can trigger non-compliance with regulation. Given the frequent reports of corporate governance regulatory failures in developing countries, we centre our research on the question – what informs corporate executives’ behaviour towards corporate governance regulations in Nigeria?

Our empirical setting – Nigeria –Footnote2 is a major economy in Africa (McKinsey Global Institute, Citation2014) and offers a valuable research context given its similar economic, political, and cultural characteristics with many developing countries (Decker, Citation2008; Isukul & Chizea, Citation2017). Nigeria is also one of the first developing countries to establish a corporate governance regulatory system (see Appendix for corporate governance codes in Nigeria). However, despite the regulatory infrastructure, there have been various corporate governance scandals, such as those at Cadbury, Unilever, Siemens, and Haliburton, as well as a banking crisis that culminated in the demise of several banks (Fosu et al., Citation2020; Okike & Adegbite, Citation2012; Tahir et al., Citation2017). These challenges are typically attributed to weak institutional arrangements (Nakpodia et al., Citation2018) and ineffective corporate regulation (Adekoya, Citation2011).

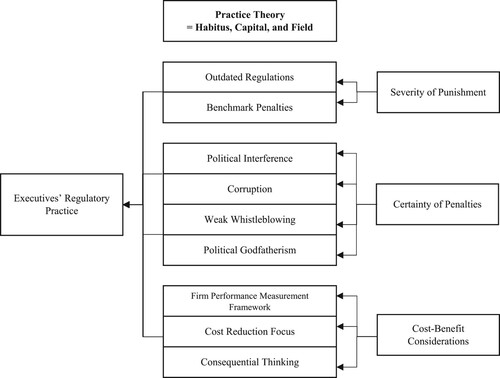

Relying on semi-structured interviews with 31 executives of listed companies in Nigeria, this paper extends Bourdieu’s theorising by identifying situational and cultural field factors that inform executives’ attitudes towards regulation. We find that, in Nigeria, nine field factors (outdated regulations, benchmarked penalties, political interference, political godfatherism, corruption, passive whistleblowing, firm performance measurement framework, consequentialist thinking, and cost reduction focus) influence regulatory compliance. We categorised these factors into broader fields: the severity of punishment, certainty of punishment, and cost–benefit considerations. These nine nuanced situational and cultural field factors are forces that determine executives’ practice in Nigeria, signposting the country as a weak institutional context. For instance, the executives’ ability to deploy their capital (e.g. social capital via relationships with political agents) frustrates and erodes the certainty of punishment. Also, the severity of punishment is far less important to erring stakeholders than the certainty of that punishment. Besides, we find evidence of sequential rational ordering between the severity and certainty of punishment. The limited understanding of corporate governance’s broader benefits and the opportunity to exploit regulatory weaknesses intensify the motivation for cost–benefit considerations towards regulation. Lastly, our data indicate that the operating environment amplifies the significance of non-economic capital relative to economic capital. The rest of the paper proceeds as follows: we review the literature and present our theoretical anchor. Next, we introduce our methodology and data analysis approach. We then discuss our findings, highlight their implications, and conclude.

2. Theory and literature review

In many developing economies, corporate agents seem to be indifferent to regulation (Adegbite & Nakajima, Citation2011), with a propensity to resist control mechanisms and circumvent rules of economic behaviour (Ahunwan, Citation2002). The disregard for regulation and control is visible in the lack of transparency and accountability, and disrespect for the law (Adekoya, Citation2011). To explain the foregoing statement, Cornish and Clarke (Citation1986) emphasise the role of contextual features, adding that infractions persist because they offer the most effective means of achieving agents’ desired objectives. Cornish and Clarke (Citation1986; Citation2002) further maintain that a range of factors – self-control, moral beliefs, emotional state, and association with delinquent peers – influence an individual’s decision to breach regulations as a means for realising defined goals. Becker (Citation1968) also links rational choice to cost–benefit validation (efficiency). Indeed, corporate governance systems worldwide derive from contrasting legal, regulatory, and institutional environments, as well as historical and cultural features (Maher & Andersson, Citation1999). But, as Archer and Tritter (Citation2000) observe, the literature pays limited attention to the effects of situational and cultural influences on decision-making, thus compelling an understanding of regulatory practices that accounts for the complexity of human decision-making (Jolls et al., Citation1998).

To explore situational and cultural influences on decision-making, we embrace Bourdieu’s practice theory. The theory aids our understanding of the scientific rationality logic that underpins several organisational and social science theories (Sandberg & Tsoukas, Citation2011). Besides, it helps in investigating, explaining, and theorising aspects of management and organisational practice in an informed way, providing more accurate accounts of the logic of practices (Sandberg & Tsoukas, Citation2016). The benefit of practice theory is that it has practice as its primary object of study (Rouse, Citation2007), allowing its recognition as a fundamental component of social life (Schatzki, Citation1996). In doing so, practice theory acknowledges the importance of domain activity, performance, and work in the contextual perpetuation of all aspects of social life (Nicolini, Citation2012).

Bourdieu’s practice theory consists of three concepts – habitus, capital, and field – that cumulate as “practice” (Bourdieu, Citation1984). It is succinctly reflected in the formula: “[(habitus) (capital)] + field = practice” (Bourdieu, Citation1984, p. 101). According to Power (Citation1999), practice emerges from the relationship between an individual’s habitus, varieties of capital, and the field of action. Thus, practice should not be reduced to habitus, field, or capital but grow from their interrelationship (Swartz, Citation2012). Fields are structured spaces organised around specific forms of capital, consisting of dominant and subordinate positions (Power, Citation1999). At the macro level, fields represent arenas of production, circulation, and appropriation of goods, services, knowledge, or status, and the competitive positions held by agents in their effort to accumulate and monopolise these different kinds of capital (Swartz, Citation2012). Examples of fields that Bourdieu studied include the field of law and the field of science. However, as evident from the foregoing, fields cannot exist without capital (Power, Citation1999; Vincent & Pagan, Citation2019).

Bourdieu explains that capital offers agents a resource to extend their interest in fields (Vincent & Pagan, Citation2019). The capital terminology signifies various resources that earn different relevance in specific contexts (Hill, Citation2018). Also, capital can be conceived as every tangible and intangible resource that could be exchanged, from physical goods to invisible ones, such as recommendations (Hill, Citation2018). Bourdieu articulates four primary forms of capital: economic, cultural, social, and symbolic, and Karataş-Özkan (Citation2011) further noted that economic capital provides the central channel for interactions within the economic system of capitalism. The economic capital can be transformed into three other capital forms (social, cultural, and symbolic) to capture unaccounted value (Favotto & Kollman, Citation2021).

The concept of field and capital is closely linked to habitus in that what is seen as valuable in the field shapes agents’ interpretation and motivations to perform specific actions, thereby permitting specific social practices (Sandberg & Tsoukas, Citation2016). Habitus emphasises “the generative principle of regulated improvisation” (Bourdieu, Citation1990, p. 57). “Habitus is this kind of practical sense for what it is to be done in a given situation – what is called in sport a “feel” for the game, that is, the art of anticipating how a particular game will likely evolve, which is inscribed in the present state of play” (Bourdieu, Citation1998, p. 25). Habitus thus allows practice theory to depart from the objectivism (fact)–subjectivism (reason) dichotomy that Bourdieu criticises for failing to capture the logic of social practices appropriately.

According to Bourdieu, objectivism projects humans as deterministic causality machines that are only connected contingently to their social environments (Sandberg & Dall'Alba, Citation2009). Such understanding fails to account for how human interpretation determines their actions. Gans (Citation1996) queries whether “reason” explains the connection between action and consequence. Reason may be influenced by ethics, environment, culture, and ambition etc. For example, when managers engage in activities that shrink shareholder wealth, can “reason” sufficiently explain the motivation for such behaviour? Whether “fact” and “reason” offer sufficient explanation for practical decisions is debateable. However, practice theory provides a system of durable but changeable and adaptable dispositions of how to perceive, think, and act that enable agents to respond and adjust to the unfolding contingencies of the situation at hand in ways that give consistency and coherence to social practices over time (Bourdieu, Citation1977; Sandberg & Tsoukas, Citation2016). Such insights are critical in establishing effective corporate governance regulations that acknowledge broad influences regarding regulatory compliance.

Corporate governance regulation has been explored from a range of perspectives. While legal systems assume that punishment deters crimes (Dölling et al., Citation2009), a critical consideration in corporate governance regulation is the severity of punishment. The severity of punishment emphasises the degree, size, or extent of a penalty (punishment). There has been an inconsistent stream of results in the literature investigating how the severity of punishment deters infractions. Whereas Friesen (Citation2012) and Hansen (Citation2015) report that increasing the severity of punishment is a more effective deterrent than increasing the probability (certainty) of punishment, scholars such as Grasmick and Bryjak (Citation1980), Loughran et al. (Citation2015), and Chalfin and McCrary (Citation2017) disagree, suggesting that punishment’s severity does not deter misbehaviour. Grasmick and Bryjak (Citation1980) explain that the failure to account for differences (economic, social, etc.) among agents hinders the deterrent effect of punishment severity. It is worth noting that the literature generally mirrors practices in robust institutional environments. Weaker institutional settings present different challenges. Agents in such countries can manipulate state and corporate machinery in desired directions. Nakpodia and Adegbite (Citation2018) expose how corporate governance practices in Nigeria mirror elites’ preferences. In Nigeria, the deterrence prospects of the severity of punishment depend on what it is thought to be, rather than its actual levels (Waldo & Chiricos, Citation1972). It is crucial to examine whether the benefits of circumventing governance rules exceed related penalties in weak institutional environments.

In addition to punishment severity, another primary consideration in corporate governance regulation is the certainty of punishment. The certainty of punishment reflects the likelihood or probability of a penalty (Walters, Citation2018). Unlike severity of punishment, Walters and Morgan (Citation2019) note that there is a substantial body of support for certainty of punishment as a deterrent to crime. Doob and Webster (Citation2003) accept that certainty of punishment is deemed more important than its severity in deterring misbehaviour. Given that high levels of certainty produce substantial decreases in crime (Tittle & Rowe, Citation1974), the question then is whether regulators should maximise certainty of punishment (Grogger, Citation1991; Loughran et al., Citation2015). A further concern focuses on the inconsistency in applying certainty of punishment. For instance, how is certainty applied among agents in weak institutional settings? The need to enrich the debate demands an investigation that extends to understudied contexts.

There is a recent shift in corporate governance regulation in Nigeria from “comply or explain” to “apply and explain”. The new code compels the application of all principles, with an explanation of how organisations have applied the principles. We note that external conditions impact the probability of punishment for corporate infractions. In this regard, the public interest theory suggests that regulation results from public demand for correction of market failures to maximise social welfare (Johnston et al., Citation2021; Scott, Citation2015). However, from a practical perspective, the theory is superficial and naïve (Scott, Citation2015), especially when the legislature’s ability to force the regulatory bodies to act in the public interest is unconvincing (Babayanju et al., Citation2017). According to the regulatory or social capture theory (Fisher et al., Citation2013), when regulators are weak, professionals (e.g. managers and directors) dominate the regulatory mechanism, overpower the regulators, and eventually circumvent their regulations. Regulatory capture is visible in countries like Nigeria, as most regulatory agencies appear to be dominated by corporate agents (Babayanju et al., Citation2017).

Moreover, any regulatory transaction must be considered as a triadic engagement consisting of buyers, sellers, and the social space (fields) within which the economic transaction occurs (Bourdieu, Citation2005). In fields, social relations can be distinct and separate or sometimes overlapping, indicating that agents belong to several fields and have fields in common with other agents (Hill, Citation2018). Field identifies a power domain that shapes agents’ behaviour in that field, just as the agents themselves shape the field structures. The field for this study is “corporate governance regulation in Nigeria”, where the buyers are “executives” and “regulators” are the sellers. In this field, corporate agents move around this space freely depending on their capital (technical, social, cultural, or financial). Employing Bourdieu’s practice theory, we leverage the relationship between buyers, sellers, and the social space to generate valuable insights that explain what informs corporate executives’ behaviour towards corporate governance regulations. Our research methodology is presented next.

3. Research methodology

This article adopts a qualitative methodology to negotiate the country’s data challenges and facilitate direct engagement with stakeholders key to corporate governance regulatory practice. Bebchuk and Weisbach (Citation2010) identified seven themes that dominate corporate governance research. Core to these themes is the critical role of executives. Similarly, studies exploring corporate governance in emerging and developing economies have paid sizeable attention to executives (see, for example, Abraham & Singh, Citation2016; Hearn et al., Citation2017). To explore how regulatory practice evolves, we focus on executives and the influences on their regulatory decisions.

In this research, we define executives as board members in publicly quoted organisations. Participants must have been board members for a minimum of three years to participate in this study. While 29 (94%) participants have more than three years of board experience, we opine that three years is adequate to comprehend corporate governance issues in organisations. We checked each potential participant’s profile to certify that this criterion is fulfilled before inviting them to participate in the study. To ensure broad coverage of the research context, we recruited executives whose companies are listed on the Nigerian Stock Exchange (NSE).Footnote3 Relying on the sector classification, we employed a cluster sampling technique (Sekaran & Bougie, Citation2016) to recruit participants. We selected at least one participant from every industrial group (see ), thereby ensuring that the sample covers the entire NSE.

Table 1. Sectoral Distribution of Participants.

Given executives’ economic and social reputation, they constitute a hard-to-reach population (Abrams, Citation2010). Consequently, securing access was challenging due to power distance (Hofstede et al., Citation2010). At the outset, letters and emails were sent to potential participants, after which we sent the interview guide to those who responded positively to our invitation. The authors reached out to participants via telephone and LinkedIn professional. Dusek et al. (Citation2015) and Utz (Citation2016) emphasise the value of LinkedIn in accessing a hard-to-reach population. While “personal contacts” and LinkedIn proved helpful, the deployment of the snowballing strategy also helped in increasing the number of participants that meet our defined criteria for participation. It is important to note that access to researchers’ professional data on LinkedIn (and LinkedIn networks) increased participants’ confidence, encouraging their participation in this research.

We used the semi-structured interview technique to collect data. The literature examining corporate governance and rational, practical choices is scant, thus requiring an in-depth exploration of the issues under consideration. The search for data that embody social cues (e.g. voice, body language) (Opdenakker, Citation2006) was also central in our decision to use the interview technique. Once interviewees were confirmed, an interview guide was sent to participants. The interviews were conducted in two phases. The first set of interviewees were undertaken in the third quarter of 2013 as part of a larger project. These interviews, involving 18 executives, were undertaken face to face and were tape-recorded.

To generate more data and account for recent developments in Nigerian corporate governance (such as amendments to the mainstream Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) Code of Corporate Governance), we conducted additional interviews in the third and fourth quarters of 2018. The latest round of interviews involved 13 executives. Nine of these interviews were conducted face to face, while the other four were undertaken via telephone. However, six of the 2018 interviews were not recorded, as some interviewees asked not to be recorded, but interviewers took detailed notes during the conversations. In sum, 31 interviews were conducted until we achieved data saturation.Footnote4 Twenty-five of these were tape-recorded. At the commencement of the interviews, participants were asked to sign a consent form. This enabled us to document their acceptance to participate in the study and communicate to participants that their anonymity and confidentiality of their responses would be protected. Participants were reminded of their right to withdraw their participation at any time during the interview. Each interview, on average, lasted about 45 min.

Data were analysed using the qualitative content analysis (QCA) technique (Elo & Kyngäs, Citation2008; Schreier, Citation2012). QCA goes beyond merely pondering on word frequency but instead focuses on language characteristics to categorise large amounts of text into a manageable number of clusters that denote similar meanings (Weber, Citation1990). Given the relationship between language and practical rational choice (Colomer, Citation1990), exploring interview texts offered more in-depth insights into interviewees’ preferences. Also, the thrust of QCA helped generate a better understanding of an understudied phenomenon (Downe-Wamboldt, Citation1992; Morgan, Citation1993) within the developing economy context, helping to broaden the opportunity to investigate the nexus between corporate governance, corporate regulation, and rational choices.

The data analysis commenced with the transcription of the recorded interviews. Data was transcribed manually to aid “data immersion” – a process that allowed us to immerse ourselves in the data collected via detailed reading and rereading of the transcribed text (Bradley et al., Citation2007). While reading the transcribed text, the text was also checked for completeness and errors were corrected. The transcribed interview data generated 264 pages of text. Considering the volume of data, we turned to NVivo 12 (a qualitative data analysis software) to store and manage the data efficiently. NVivo aids a systematic and structured analysis of transcribed data (Jackson & Bazeley, Citation2019), increases the rigour of the data analysis process (Leech & Onwuegbuzie, Citation2011), and permits the comparison and cross-comparisons of codes and themes present in the data (Welsh, Citation2002). The transcribed interview text was loaded into NVivo software as Word documents. We relied on Hsieh and Shannon’s (Citation2005) and Elo and Kyngäs’s (Citation2008) suggestions to analyse the data.

The data analysis involved three stages of coding. First, we embarked on an open coding procedure. We used the “explore – word frequency – run query” function in NVivo to generate a word cloud (), which uncovered the interviewees’ most frequently cited words. Some of these words include regulation, corruption, institutions, influence, management, governance, economic, among others. While these words provided our initial field of analysis, these words were used to create “nodes” to allow the coding of responses from interviewees relating to a specific theme. It is important to state that in “cleaning” the data to ensure that we focus on relevant themes, we used the “stop word list” tool in NVivo to isolate themes deemed irrelevant in the analysis. Some of the words added to the stop-word list include however, may, also, etc. Nigerians use these words extensively in their day-to-day communication. Once the subcategories (from open coding) were created and populated with appropriate responses, we embarked on the next coding procedure, i.e. the axial coding (Corbin & Strauss, Citation2015).

The axial coding procedure, which demands a further round of coding, requires regenerating the subcategories (from open coding) into more focused categories (higher-order conceptualisations), e.g. severity of punishment. As part of this procedure, we investigated the link among the subcategories to articulate higher-order categories. At this stage, we observed that some subcategories, e.g. corruption and regulation, are relevant to more than a single higher-order category, e.g. certainty of punishment. Consequently, such subcategories were added to the respective higher-order categories. In the final stage of data analysis, we adopted a selective coding approach to explore the relationship between the higher-order categories. The selective coding process helped create the main category, which identifies the core influences in the choice decisions of executives in Nigeria.

While the above stages substantially reflect the conventional content analysis approach, the premise of QCA demands that themes that are not widely referenced by interviewees but convey significant insights are incorporated in the analysis. In deciding which themes satisfy this expectation, we examined such themes in the context of the extant literature. For instance, themes such as government, society, reality, etc., were referenced by a few interviewees, but these themes have attracted considerable attention in the literature. Besides, considering the interest alluded to these themes by the interviewees that identified them, we contend that these topics deserve greater scrutiny. Based on the coding and categories generated from the analysis, findings were formulated by connecting subcategories with related characteristics, merging the categories, and creating the main categories from the interconnections. We discuss these next, using supporting extracts from the anonymised data (E1 – E31).

4. Findings and discussions

While individuals and firms in a country operate under similar regulations (Aguilera et al., Citation2018), understanding infinite rules is problematic because it requires an infinite number of thoughts to comply with regulations (Taylor, Citation1993). Therefore, regulating corporate governance by creating more rules may be counter-effective as agents interpret and reconcile regulations (Gadamer, Citation1979). How then do corporate agents develop their corporate governance regulatory practice? Our data unmasks field factors that inform executives’ behaviour towards corporate governance regulations. We link these situational and cultural field factors to Bourdieu’s concept of field, capital and habitus. Our data emphasises three areas – the severity of regulatory penalties, the certainty of regulatory penalties, and cost–benefit considerations (see ).

4.1. Severity of regulatory penalties

Regulators and government officials rely on corporate regulations to enact penalties with varying severity levels to establish corrective, detective, and preventative controls (Sadiq & Governatori, Citation2015). In this subsection, we present two field factors that influence executives’ disposition to the severity of penalties.

4.1.1. Outdated regulations

From the interviews, a consistently referenced factor that influences executives’ disposition regarding the severity of regulatory punishment is outdated regulations. Twenty-four interviewees mentioned conflicting and outdated regulations that create loopholes in the field and shape their regulatory habitus (E5, E6, E13, E27, and E30). Such opportunities allow operators to desist from acting in the spirit of the law (Sandberg & Tsoukas, Citation2016). E13 commented that

Most of the penalties in the country’s corporate governance regulations have limited effect because the regulation’s strength diminishes over time. As the regulatory response to new market developments is sluggish, the effectiveness of existing regulation is eroded. The existing penalties do not provide for current developments created by new market opportunities.

The problem with time passage is that sanctions lose their severity. For example, in the Corporate and Allied Matters Act (CAMA) 1990 and its amended version (2004), Section 55 of the CAMA (1990 and 2004) stipulate a fine of N2500 (about £5 at current exchange rate) when a foreign company violates the requirements of Section 54 (incorporation of foreign companies) of the same Act. In the updated CAMA (2016), the penalty was increased to N300,000 (about £650 at the current exchange rate). This means that companies violating Section 54 between 1990 and 2015 were expected to pay the same amount over 26 years.

The value of Nigeria’s currency (the naira) is weak due to inflation and an unstable exchange rate regime. Thus, the socio-economic situation allows executives to bear perceived severe penalties (Cornish & Clarke, Citation1986), offering an economic capital that executives can transform to other forms of capital such as social and cultural capital. In addition, the penalties are not updated regularly to reflect the intended severity of infractions. Therefore, as executives easily afford the fines, it increases their discretion to evade regulation, especially when the market lacks the structure to punish such acts.

4.1.2. Benchmarked penalties

Another area of interest that 27 participants cited is the use of benchmark penalties. Interviewees focus on this strategy’s effectiveness in the Nigerian regulatory field, questioning the rationale for such rigid penalties. They note that given the widespread inequalities in the country’s socio-economic space, variables such as repeat offence, type of organisation, and stakeholders affected, amongst others, should inform a scenario-based penalty strategy that may deter executives from governance abuses. Indeed, respondents note that a case-based punishment regime for penalising executives integrates other attributes (e.g. reputation – symbolic capital) that are overlooked in regular penalties. A case-based penalty system also minimises executives’ rational disposition to selecting alternatives that promote their self-interest (Becker, Citation1974; Matsueda et al., Citation2006). Geeraets (Citation2018) argues that punishment systems must adopt an inclusive, justifiable, and neutral concept of punishment that takes the outward appearance of the harm inflicted as its starting point. This links with E4’s comment:

I do not subscribe to a situation where a repeat offender, for example, is given the same penalty as provided in the regulation. The regulators and the law should also pay more attention to specific industries. The impact of a bank manager that steals depositors’ money has broader economic implications than fraud committed by a manager in the retail industry. Regulators should recognise these peculiarities.

Respondents suggest that the severity of punishment in Nigeria could benefit from “locally informed strategies” that resonate with executives. These strategies would stifle the cultural, social, and symbolic capital that executives leverage to maximise their economic capital. E8 captures this position and proposes a system that enhances punishment severity:

Most times, we tend to ignore the fact that our systems will work better with locally informed strategies. You know we have a very strong affinity to our social class and our culture. Could you imagine how effective the punishment will be if offenders are denied some social rights? For instance, if executives are disallowed from taking up chieftaincy titles in their towns or villages whenever they violate corporate codes? This would increase the severity of punishments, as against the payment of fines.

4.2. Uncertainty in administering penalties

Participants indicate that uncertainties in dispensing penalties influence how executives formulate their regulatory practice. Our analysis shows that political interference, political godfatherism, corruption – who regulates the regulator, and passive whistleblowing are field factors that define how the (un)certainty of punishment influences executives’ regulatory habits.

4.2.1. Political interference

Like most developing economies, Nigeria’s economy significantly reflects the preferences of politicians responsible for public governance. This explains the increased political interference in the country’s economic sectors (Adegbite et al., Citation2012). Participants acknowledge the growing influence of politicians on the economy. E2 states that

In recent times, the power and authority of politicians are growing. They should typically call the shots, but how they are going about their responsibilities is a cause for concern. And because he who pays the piper dictates the tune, they have the power to influence the (institutions) in the country.

The regulatory system is continuously in a state of unpredictability. You are not sure what will happen when someone commits a (corporate) crime because punishments or the absence of it depends not on the prescribed legal procedures but on what feeds the desires of certain politicians. There are examples when penalties for corporate offenders are either wholly set aside or lessened because a politician or government official has intervened.

4.2.2. Political godfatherism

In addition to political interference, participants stress that political godfatherism and connections prevalent in the country’s corporate environment provide further openings to frustrate the certainty of regulatory punishment. According to E5,

Executives seek to establish relationships with politicians to maximise their chances of taking advantage of the system. Because of the informal nature of the business environment, one way of ensuring that regulators are not on your case is to have a political godfather.

There is an increasing practice by organisations to recruit politicians onto their corporate boards. Most times, these appointments neither comply with the laid down process nor is the appointment based on merit. Two reasons mostly inform this recruitment. First, to attract government patronage and second, to have a go-to person in government.

4.2.3. Corruption – who regulates the regulator

Interviewees also indicate that the capacity of regulations to deter corporate misdemeanours suffers from widespread systemic corruption. Participants cite cases where regulators are bribed, allowing offenders to evade punishment. E16 puts it thus:

How are you sure that regulators will penalise offenders when you can bribe most of them? Let me tell you something interesting. Some of the regulators or institutions even conduct themselves in a way that suggests that they want bribes. Some people pay these bribes because it saves time, especially the time it takes to dispense justice in courts.

I think poverty does not help in ensuring that appropriate punishment is handed out to people who violate laws. Have you seen the pay package of some regulators? It is tough for them to turn down bribes because of their meagre salaries.

Who regulates the regulator? Corporate governance is a check and balance system. What checks and balances are in place for regulators? For example, I am not aware of any requirement to comment on the performance of a regulator. The lack of accountability means that they (regulators) could alter and misinterpret provisions of the law to satisfy ulterior objectives.

4.2.4. Passive whistleblowing mechanism

Interviewees explain that the lack of accountability in the socio-economic field contributes to executives’ regulatory habitus. In particular, they note that the ineffectiveness of the regulatory system impedes sound whistleblowing practices. According to E6,

Because the whistleblowing mechanism is weak, regulators and industry actors get away with a lot of things. To whom do you report? Reporting them to their bosses or even to the ministry does not help. On top of that, there is no protection for you, so your identity is exposed. That means lots of trouble for you and your organisation.

There is no doubt that corruption bears a damaging effect on regulation. Still, I think that the understanding of the benefit of corporate governance on firm performance is shallow among executives and even regulators. I feel that these (stakeholders) merely pay lip service to corporate governance. I am also on the board of a consulting outfit. When we try to sell corporate governance-related services to organisations, that approach is often rebuffed because many consider it a waste of resources.

In agreement with Walters and Morgan (Citation2019), participants affirm that the certainty of punishment deters infractions. The data suggests that executives’ concerns about the certainty of penalties stem from political interference, political godfatherism, corruption (who regulates the regulator), and a passive whistleblowing system. The four field factors identified fuel institutional concerns, thereby hampering the prospect of certainty of penalties as a way of checking executives’ regulatory habitus. Dietrich and List (Citation2013) explain that facts and reason dictate agents’ practical choices, but Becker (Citation1974) affirms that self-interest and the pursuit of material gain drive individuals’ behaviours. These contentions stress how operators react, especially when presented with opportunities that depart from the norm. Our data reflects Bourdieu’s position on practice, underlining the executives’ desire to make decisions that integrate reason, available facts, self-interest, and field imperfections. This, in turn, dents the deterrence projections of regulators as operators leverage their social and symbolic capitals (political connections and godfatherism) in a corrupt field to escape the certainty of penalties and build their regulatory habitus.

4.3. Cost–benefit considerations

The corporate governance literature abounds with studies that reinforce cost–benefit rationalisation in regulation-based decision-making (see Coates, Citation2015). From our analysis, interviewees indicate that firm performance measurement framework, consequentialist thinking, and cost reduction focus are situational and cultural field factors that underpin executives’ cost–benefit thinking.

4.3.1. Firm performance measurement framework

Practice theory stresses the importance of performance and success in the workplace and all aspects of social life (Nicolini, Citation2012). Thirty interviewees assert that the performance measurement framework – guidelines that firms use to facilitate corporate success and measure business operations’ effectiveness – influences executives’ reasoning. Moreover, in Nigerian firms, financial performance metrics are accentuated far more than non-financial performance metrics (E8, E25, E15, and E14). According to E8,

Shareholders’ expectations regarding my performance cut across various parameters, but I know those (measures) that they constantly monitor. They want regular dividends, which is tied to profits. If I underperform profit-wise, I may be sacked.

My decision-making focuses on two areas. The first is how I can recover my cost, while the second is to what extent I can maximise shareholders’ wealth. Both objectives demand that I monitor my costs and look for how to achieve these objectives.

More than ever, organisations aim to grow financial results quickly that they are ready to set aside regulatory guidelines. For instance, some organisations are no longer willing to engage in CSR because of cost considerations. They mostly think short term, forgetting that social engagement can boost their reputation, which may help their companies survive over the long term.

4.3.2. Consequentialist thinking

In exploring Gans’s (Citation1996) contention on how reason justifies action, most participants suggest that the consequences of one’s conduct offer the basis for arbitrating that conduct’s rightness (or wrongness). As interviewees note, consequentialist thinking among executives nurtures the desire to achieve corporate outcomes at all costs. Participants (E3, E28, and E31) suggest that consequentialism as a component of the cost–benefit evaluation is rife even when the benefit is marginal and short term. E3 comments that

Business is about making decisions. My responsibility is primarily to my shareholders. They provide the money and ask me to use my knowledge and expertise to grow their investment. So, I am always in the business of comparing the costs and benefits of every decision as I must deliver on the promise that I made.

The economic impact of losing your job surpasses the shame of not adhering to regulatory guidelines, especially as the system is weak in penalising non-compliance.

4.3.3. Cost reduction focus

The focus on cost reduction in Nigeria’s corporate field, according to E3, E28, and E22, encourages firms to leverage loopholes in regulations that emphasise “minimum” standards rather than “global best practices”. Though interviewees view corporate regulation in Nigeria as guidelines to encourage ethical business practices, there are many gaps in the regulations that provide businesses with opportunities to undermine the system. E22 explains that

Because governance regulations are a mere guide that encourages businesses to act ethically, most organisations focus on the minimal requirements even when it is apparent that the organisation will benefit from implementing the broad provisions of the regulation. Organisations do this to minimise their costs.

We operate a traditional business environment that lacks the sophistication that you find in the West. The people are frustrated by too many socio-economic problems, which means that they cannot question the corporate choices of their directors, especially if the financial report looks okay.

What can the market do? Do they even know their rights? How many consumer movements call out companies? Customers are oblivious of their rights. They are unaware of how they can impact a firm’s reputation and its prospect.

These factors have attracted muted interest among governance scholars. Our data resonates with the concerns in Cornish and Clarke (Citation2002), emphasising that these ignored factors precede executives’ regulatory habitus. For instance, the desire to maximise shareholder wealth compels executives to increase income and reduce costs. The widespread short-term focus in the Nigerian field implies that the benefits of a sound corporate governance system, which is typically evident in the long term, are sacrificed in favour of options that maximise payoffs in the short term. Consequently, it is common practice to adopt these elements in evaluating the cost and benefit of complying with relevant regulations. Arguably, Bourdieu’s (Citation1990) concept of “field” indicates the effect of social-economic pressures in an environment. In this instance, given the institutional forces, we contend that executives rely less on their technical capacity. Instead, they seek to reap economic rents without much field resistance. Therefore, we maintain that executives’ cost–benefit considerations shape their governance regulatory habitus in ways that contradict sound corporate governance principles.

5. Implications

Becker (Citation1974) notes that the use of punishment has been recommended as a panacea for regulatory non-compliance. However, empirical evidence regarding its effectiveness is mixed (Chalfin & McCrary, Citation2017; Loughran et al., Citation2015), with scholars pointing to the field to explain these variations. Field weaknesses increase executives’ latitude to control regulations, enabling them to maximise their capital while reinforcing their regulatory habitus. This research highlights nine factors (outdated regulations, benchmarked penalties, political interference, political godfatherism, corruption – who regulates the regulator, passive whistleblowing, firm performance measurement framework, consequentialist thinking, and cost reduction focus) fortifying executives’ regulatory practice in Nigeria. It sheds light on how corporate executives draw on social macro elements, and how these macro features shape behaviour at the micro-level (Hill, Citation2018). As a result, we outline two main implications of this research.

First, we observe that the field factors interfere with the severity of punishment, the certainty of penalties, and cost–benefit considerations and explain executives’ attitude to corporate governance regulations in Nigeria. Therefore, the combination of Bourdieu’s concept of habitus, capital, and field attributes ultimately establishes executives’ regulatory practice. Field characteristics in weak institutional contexts frustrate certainty and severity of penalties in different ways. The widespread corruption and ineffective regulations allow executives to utilise their capital to manipulate the punishment system. Consequently, we note that the severity of punishment is less important to erring executives relative to the certainty of that punishment. This uncovers a model of sequential rationalisation in executives’ decision-making as they embark on an ordering that considers punishment certainty ahead of its severity. To make decisions, executives evaluate the severity and certainty of regulatory provisions. We observe that where it is possible to evade a specific regulation, its severity becomes secondary and irrelevant. Besides, the severity of penalties rests on a mix of factors that include the form of punishment, the impact of punishment, and the nature of the industry. In contexts where market reaction to corporate malfeasance is feeble, the severity of punishment weakens. Consequently, the value of the severity of punishment in deterring executives’ infractions is negligible. While this position challenges Friesen’s (Citation2012) and Hansen’s (Citation2015) findings, it supports Loughran et al.’s (Citation2015) and Chalfin and McCrary’s (Citation2017) results. Moreover, sequential rationalisation encourages “technical compliance” (see Nakpodia et al., Citation2018) that promotes adherence to the letter, instead of to the spirit, of regulations among executives.

Second, we reflect on Bourdieu’s practice theory in a weak institutional environment. We observe the significance of field in the emergence of practice, noting that executives’ regulatory disposition (practice) responds to field attributes. We find that executives’ practices reflect the fluid and flexible nature of the field, considering its dependence on the changing positions of key players in a context (Croce, Citation2019). Hence, executives’ regulatory habitus is in constant flux as they react to emerging forces that define the field. Capital represents a significant fraction of these emerging forces in the field because field cannot exist without capital (Power, Citation1999). We find that increase in different forms of capital enables executives to adopt a regulatory habitus that shapes their practice.

Still on Bourdieu’s practice theory, our findings extend the capital debate. The literature (Hill, Citation2018; Vincent & Pagan, Citation2019) stresses the primacy of economic capital vis-à-vis other forms of capital, i.e. social, symbolic, and cultural. Hill (Citation2018) notes that economic capital is central to Bourdieu’s capital notion, given that it can be used to acquire other forms of capital (e.g. buying network memberships). However, drawing insights from Nigeria, we find evidence supporting the preference and dominance of non-economic capital. Most factors shaping executives’ regulatory habitus (see ) relate to non-economic forms of capital. While these factors (e.g. political interference, political godfatherism) help executives acquire non-economic capital, our data indicates that executives seek to accumulate social, symbolic, and cultural capital before economic capital. Poor institutional arrangements and a largely informal business environment minimise the resources required to acquire non-economic capital compared to economic capital.

6. Conclusion

In the face of growing corporate governance failures, calls to review corporate governance regulations and the regulatory approach are mounting (Jabotinsky & Siems, Citation2018). A central feature of these calls is the need to increase regulation and punish corporate offenders more heavily (Geeraets, Citation2018). However, achieving the foregoing demands an understanding of the drivers of executives’ regulatory attitudes. Relying on Nigeria’s peculiar institutional configuration, this research employs Bourdieu’s practice theory to investigate the factors that explain executives’ behaviour towards corporate governance regulations.

As revealed in , we uncover nine primary field factors that impact executives’ behaviour in the presence of the severity of punishment, the certainty of punishment, and cost–benefit regulatory considerations. These field factors are responsible for the development of executives’ regulatory habitus and practice. These field factors allow executives to adopt a sequential rationalisation procedure that pays greater attention to the certainty of punishment while relegating the severity of penalties. Even so, our data indicates that the certainty of enforcing penalties can be negotiated using both economic and non-economic forms of capital. Furthermore, the study context enables us to examine the link between economic and non-economic capital. While the literature emphasises the supremacy of economic capital, our data indicates that the operating environment (field) amplifies the significance of non-economic capital relative to economic capital.

These findings offer broad opportunities to deepen the existing literature. This study relies on findings from a mono-stakeholder group, i.e. executives. Future research could engage a wider stakeholder group (e.g. government, regulators, customers, employees, etc.) who bear considerable influence on corporate governance regulation. In doing this, it is critical to understand other stakeholders’ viewpoints regarding the interactions between certainty, severity, and cost–benefit rationalisation with respect to corporate governance regulation. Also, drawing from a broad stakeholder group, scholars and practitioners should investigate how the blend of habitus, capital, and field facilitate practice, especially in less-studied contexts. As this paper demonstrates, evidence from other less-researched economies will enrich the literature. Given that regulators are responsible for setting and policing governance regulations, future studies can investigate regulators’ position regarding the interface between the regulatory concepts investigated in this paper. Such research will provide deeper insights into the challenges confronting regulators, as well as generate further insights into how operators circumvent provisions of corporate governance codes.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank the Journal's editor (Professor Carol Tilt) and the three anonymous reviewers for their constructive comments in helping us to improve the quality of the paper. We are also highly indebted to the participants of this study who cannot be identified due to confidential reasons. Early versions of this paper were presented at the International Conference on Corporate Governance and Business Ethics held in Singapore in July 2018 and the Global Regulatory Governance Research Network Conference held in Hong Kong in July 2019. The authors appreciate the comments and feedback received from participants at these conferences.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 Institutional and legal environments primarily inspire corporate governance systems and institutions. The scholarship exploring the nexus between institutional settings and corporate governance has mainly employed cross-country evaluations, as well as investigating changes over time (e.g. Judge et al., Citation2008). However, the last few decades have witnessed extreme changes in institutional environments, triggering new opportunities for scholars to research governance subjects in new contexts. Shifts towards excessive risk-taking (Chong et al., Citation2018), unhealthy firm cultures (Wang et al., Citation2021), and growing evidence of corporate misconduct (Zheng & Chun, Citation2017) are among a few of the numerous challenges to existing models of corporate governance prompted by weak institutional environments.

2 International organisations such as the World Bank (Citation2015) and PwC (Citation2017) have documented the country’s economic potential. PwC (Citation2017) estimates that Nigeria will rank among the top 15 economies of the world, based on GDP, by 2050. Nigeria has also remained a favoured destination for foreign direct investment.

3 As of September 2019, and with a total market capitalisation of USD$74.62 billion, NSE had 161 listed equities spread across 11 industry sectors.

4 At this point, we anticipated that further interviews would not provide fresh insights.

References

- Abraham, E., & Singh, G. (2016). Does CEO duality give more influence over executive pay to the majority or minority shareholder? (A survey of Brazil). Corporate Governance: The International Journal of Business in Society, 16(1), 96–115. https://doi.org/10.1108/CG-05-2015-0073

- Abrams, L. S. (2010). Sampling ‘hard to reach’ populations in qualitative research: The case of incarcerated youth. Qualitative Social Work, 9(4), 536–550. https://doi.org/10.1177/1473325010367821

- Adegbite, E. (2010). The determinants of good corporate governance: The case of Nigeria. Doctoral thesis, Cass Business School, City, University of London.

- Adegbite, E., Amaeshi, K., & Amao, O. (2012). The politics of shareholder activism in Nigeria. Journal of Business Ethics, 105(3), 389–402. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-011-0974-y

- Adegbite, E., & Nakajima, C. (2011). Institutional determinants of good corporate governance: The case of Nigeria. In E. Hutson, R. Sinkovics, & J. Berrill (Eds.), Firm-Level internationalisation, regionalism and globalisation (pp. 379–396). Palgrave Macmillan.

- Adekoya, A. (2011). Corporate governance reforms in Nigeria: Challenges and suggested solutions. Journal of Business Systems, Governance and Ethics, 6(1), 38–46. https://doi.org/10.15209/jbsge.v6i1.198

- Aguilera, R. V., Judge, W. Q., & Terjesen, S. A. (2018). Corporate governance deviance. Academy of Management Review, 43(1), 87–109. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2014.0394

- Ahunwan, B. (2002). Corporate governance in Nigeria. Journal of Business Ethics, 37(3), 269–287. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1015212332653

- Archer, M. S., & Tritter, J. Q. (Eds.). (2000). Rational choice theory: Resisting colonisation. Routledge.

- Arjoon, S. (2006). Striking a balance between rules and principles-based approaches for effective governance: A risks-based approach. Journal of Business Ethics, 68(1), 53–82. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-006-9040-6

- Armitage, S., Hou, W., Sarkar, S., & Talaulicar, T. (2017). Corporate governance challenges in emerging economies. Corporate Governance: An International Review, 25(3), 148–154. https://doi.org/10.1111/corg.12209

- Babayanju, A. G. A., Animasaun, R. O., & Sanyaolu, W. A. (2017). Financial reporting and ethical compliance: The role of regulatory bodies in Nigeria. Account and Financial Management Journal, 2(2), 600–616.

- Bebchuk, L. A., & Weisbach, M. S. (2010). The state of corporate governance research. Review of Financial Studies, 23(3), 939–961. https://doi.org/10.1093/rfs/hhp121

- Becker, G. S. (1968). Crime and punishment: An economic approach. Journal of Political Economy, 76(2), 169–217. https://doi.org/10.1086/259394

- Becker, G. S. (1974). Crime and punishment: An economic approach. In G. S. Becker, & W. M. Landes (Eds.), Essays in the Economics of Crime and punishment (pp. 1–54). National Bureau of Economic Research.

- Black, J., Hopper, M., & Band, C. (2007). Making a success of principles-based regulation. Law and Financial Markets Review, 1(3), 191–206. https://doi.org/10.1080/17521440.2007.11427879

- Blanchette, I., & Richards, A. (2010). The influence of affect on higher level cognition: A review of research on interpretation, judgement, decision making and reasoning. Cognition & Emotion, 24(4), 561–595. https://doi.org/10.1080/02699930903132496

- Bourdieu, P. (1977). Outline of a theory of practice (Vol. 16). Cambridge University Press.

- Bourdieu, P. (1984). Distinction: A social critique of the judgement of taste. Routledge.

- Bourdieu, P. (1990). The logic of practice. Stanford University Press.

- Bourdieu, P. (1998). Practical reason: On the theory of action. Stanford University Press.

- Bourdieu, P. (2005). The social structures of the economy. Polity Press.

- Bradley, E. H., Curry, L. A., & Devers, K. J. (2007). Qualitative data analysis for health services research: Developing taxonomy, themes, and theory. Health Research and Educational Trust, 42(4), 1758–1772. https://doi.org/10.1016/B0-08-043076-7/01022-6

- Bransen, J. (2001). Philosophy of verstehen and erklaren. In N. J. Smelser, & P. B. Baltes (Eds.), International encyclopedia of the social & behavioural sciences (pp. 16165–16170). Elsevier Science Limited.

- Chalfin, A., & McCrary, J. (2017). Criminal deterrence: A review of the literature. Journal of Economic Literature, 55(1), 5–48. https://doi.org/10.1257/jel.20141147

- Chong, L.-L., Ong, H.-B., & Tan, S.-H. (2018). Corporate risk-taking and performance in Malaysia: The effect of board composition, political connections and sustainability practices. Corporate Governance: The International Journal of Business in Society, 18(4), 635–654. https://doi.org/10.1108/CG-05-2017-0095

- Coates, J. C. (2015). Towards better cost-benefit analysis: An essay on regulatory management. Law and Contemporary Problems, 78(1), 1–23.

- Colomer, J. M. (1990). The utility of bilingualism: A contribution to a rational choice model of language. Rationality and Society, 2(3), 310–334. https://doi.org/10.1177/1043463190002003004

- Corbin, J., & Strauss, A. (2015). Basics of qualitative research: Techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory (4th ed). Sage Publications.

- Cornish, D. B., & Clarke, R. V. (2002). Crime as a rational choice. In S. Cote (Ed.), Criminological theories: Bridging the past to the future (pp. 291–296). SAGE Publications.

- Cornish, D., & Clarke, R. (1986). Introduction. In D. Cornish, & R. Clarke (Eds.), The reasoning criminal: Rational choice Perspectives on offending (pp. 1–18). Transaction Publishers.

- Croce, M. (2019). The levels of critique. Pierre Bourdieu and the political potential of social theory. Sociologica, 13(2), 23–35.

- Decker, S. (2008). Building up goodwill: British business, development and economic nationalism in Ghana and Nigeria, 1945–1977. Enterprise and Society, 9(04), 602–613. https://doi.org/10.1093/es/khn085

- Dietrich, F., & List, C. (2013). A reason-based theory of rational choice. Nous (detroit, Mich ), 47(1), 104–134. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0068.2011.00840.x

- Doob, A. N., & Webster, C. M. (2003). Sentence severity and crime: Accepting the null hypothesis. Crime and Justice, 30, 143–195. https://doi.org/10.1086/652230

- Downe-Wamboldt, B. (1992). Content analysis: Method, applications, and issues. Health Care for Women International, 13(3), 313–321. https://doi.org/10.1080/07399339209516006

- Dölling, D., Entorf, H., Hermann, D., & Rupp, T. (2009). Is deterrence effective? Results of a meta-analysis of punishment. European Journal on Criminal Policy and Research, 15(1), 201–224. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10610-008-9097-0

- Dusek, G. A., Yurova, Y. V., & Ruppel, C. P. (2015). Using social media and targeted snowball sampling to survey a hard-to-reach population: A case study. International Journal of Doctoral Studies, 10, 279–299. https://doi.org/10.28945/2296

- Eells, E. (2016). Rational choice and causality. Cambridge University Press.

- Ellis, A. (2003). A deterrence theory of punishment. The Philosophical Quarterly, 53(212), 337–351. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9213.00316

- Elo, S., & Kyngäs, H. (2008). The qualitative content analysis process. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 62(1), 107–115. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04569.x

- Fama, E. F. (1980). Agency problems and the theory of the firm. The Journal of Political Economy, 88(2), 288–307. https://doi.org/10.1086/260866

- Favotto, A., & Kollman, K. (2021). Mixing business with politics: Does corporate social responsibility end where lobbying transparency begins? Regulation & Governance, 15(2), 262–279. https://doi.org/10.1111/rego.12275

- Filatotchev, I., Jackson, G., & Nakajima, C. (2013). Corporate governance and national institutions: A review and emerging research agenda. Asia Pacific Journal of Management, 30(4), 965–986. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10490-012-9293-9

- Fisher, C., Lovell, A., & Valero-Silva, N. (2013). Business Ethics and values: Individual, corporate and International perspectives (4th ed). Pearson.

- Fosu, S., Danso, A., Agyei-Boapeah, H., Ntim, C., & Adegbite, E. (2020). Credit information sharing and loan default in developing countries: The moderating effect of banking market concentration and national governance quality. Review of Quantitative Finance and Accounting, 55(1), 55–103. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11156-019-00836-1

- Friesen, L. (2012). Certainty of punishment versus severity of punishment: An experimental investigation. Southern Economic Journal, 79(2), 399–421. https://doi.org/10.4284/0038-4038-2011.152

- Gadamer, H.-G. (1979). Practical philosophy as a model of the human sciences. Research in Phenomenology, 9(1), 74–85. https://doi.org/10.1163/156916479X00057

- Gans, J. S. (1996). On the impossibility of rational choice under incomplete information. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 29(2), 287–309. https://doi.org/10.1016/0167-2681(95)00064-X

- Garland, D. (1991). Sociological perspectives on punishment. Crime and Justice, 14, 115–165. https://doi.org/10.1086/449185

- Geeraets, V. (2018). Two mistakes about the concept of punishment. Criminal Justice Ethics, 37(1), 21–35. https://doi.org/10.1080/0731129X.2018.1441227

- Goldman, E., Rocholl, J., & So, J. (2013). Politically connected boards of directors and the allocation of procurement contracts. Review of Finance, 17(5), 1617–1648. https://doi.org/10.1093/rof/rfs039

- Grasmick, H. G., & Bryjak, G. J. (1980). The deterrent effect of perceived severity of punishment. Social Forces, 59(2), 471–491. https://doi.org/10.2307/2578032

- Grogger, J. (1991). Certainty vs severity of punishment. Economic Inquiry, XXIX(2), 297–309. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1465-7295.1991.tb01272.x

- Hansen, B. (2015). Punishment and deterrence: Evidence from drunk driving. American Economic Review, 105(4), 1581–1617. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.20130189

- Hearn, B., Strange, R., & Piesse, J. (2017). Social elites on the board and executive pay in developing countries: Evidence from Africa. Journal of World Business, 52(2), 230–243. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jwb.2016.12.004

- Hill, I. (2018). How did you get up and running? Taking a bourdieuan perspective towards a framework for negotiating strategic fit. Entrepreneurship & Regional Development, 30(5-6), 662–696. https://doi.org/10.1080/08985626.2018.1449015

- Hofstede, G., Hofstede, G. J., & Minkov, M. (2010). Cultures and organisations: Software of the mind (3rd ed). McGraw Hill.

- Hsieh, H.-F., & Shannon, S. E. (2005). Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qualitative Health Research, 15(9), 1277–1288. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732305276687

- Isukul, A. C., & Chizea, J. J. (2017). Corporate governance disclosure in developing countries: A comparative analysis in Nigerian and South African banks. SAGE Open, 7(3), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244017719112

- Jabotinsky, H., & Siems, M. (2018). How to regulate the regulators: Applying principles of good corporate governance to financial regulatory authorities. The Journal of Corporation Law, 44, 351–384.

- Jackson, K., & Bazeley, P. (2019). Qualitative data analysis with NVivo (3rd ed). SAGE.

- Johnston, A., Amaeshi, K., Adegbite, E., & Osuji, O. (2021). Corporate social responsibility as obligated internalisation of social costs. Journal of Business Ethics, 170(1), 39–52. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-019-04329-y

- Jolls, C., Sunstein, C. R., & Thaler, R. (1998). A behavioral approach to law and economics. Stanford Law Review, 50(5), 1471–1550. https://doi.org/10.2307/1229304

- Judge, W. Q., Douglas, T. J., & Kutan, A. M. (2008). Institutional antecedents of corporate governance legitimacy. Journal of Management, 34(4), 765–785. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206308318615

- Karataş-Özkan, M. (2011). Understanding relational qualities of entrepreneurial learning: Towards a multi-layered approach. Entrepreneurship & Regional Development, 23(9-10), 877–906. https://doi.org/10.1080/08985626.2011.577817

- Kirkbride, J., & Letza, S. (2004). Regulation, governance and regulatory collibration: Achieving an “holistic” approach. Corporate Governance: An International Review, 12(1), 85–92. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8683.2004.00345.x

- Kumar, P., & Zattoni, A. (2016). Institutional environment and corporate governance. Corporate Governance: An International Review, 24(2), 82–84. https://doi.org/10.1111/corg.12160

- Leech, N. L., & Onwuegbuzie, A. J. (2011). Beyond constant comparison qualitative data analysis: Using NVivo. School Psychology Quarterly, 26(1), 70. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0022711

- Levin, J., & Milgrom, P. (2004). Introduction to choice theory. Stanford University Press.

- Loughran, T. A., Brame, R., Fagan, J., Piquero, A. R., Mulvey, E. P., & Schubert, C. A. (2015). Studying deterrence among high-risk adolescents. Juvenile Justice Bulletin (August), 1–16.

- Maher, M., & Andersson, T. (1999). Corporate governance: Effects on firm performance and economic growth. Organisation for Economic Co-Operation and Development, 1–51. https://www.oecd.org/sti/ind/2090569.pdf.

- Marnet, O. (2005). Behaviour and rationality in corporate governance. Journal of Economic Issues, 39(3), 613–632. https://doi.org/10.1080/00213624.2005.11506837

- Matsueda, R. L., Kreager, D. A., & Huizinga, D. (2006). Deterring delinquents: A rational choice model of theft and violence. American Sociological Review, 71(1), 95–122. https://doi.org/10.1177/000312240607100105

- McKinsey Global Institute. (2014). Nigeria’s renewal: Delivering inclusive growth in Africa’s largest economy. https://www.mckinsey.com/featured-insights/middle-east-and-africa/nigerias-renewal-delivering-inclusive-growth.

- Morgan, D. L. (1993). Qualitative content analysis: A guide to paths not taken. Qualitative Health Research, 3(1), 112–121. https://doi.org/10.1177/104973239300300107

- Nagin, D. S. (2013). Deterrence in the twenty-first century. Crime and Justice, 42(1), 199–263. https://doi.org/10.1086/670398

- Nakpodia, F., & Adegbite, E. (2018). Corporate governance and elites. Accounting Forum, 42(1), 17–31. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.accfor.2017.11.002

- Nakpodia, F., Adegbite, E., Amaeshi, K., & Owolabi, A. (2018). Neither principles nor rules: Making corporate governance work in Sub-saharan Africa. Journal of Business Ethics, 151(2), 391–408. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-016-3208-5

- Nicolini, D. (2012). Practice theory, work, & organization: An introduction. Oxford University Press.

- Okike, E., & Adegbite, E. (2012). The code of corporate governance in Nigeria: Efficiency gains or social legitimisation? Corporate Ownership and Control, 95(3), 262–275. https://doi.org/10.22495/cocv9i3c2art4

- Opdenakker, R. (2006). Advantages and disadvantages of four interview techniques in qualitative research. Paper presented at the Forum: Qualitative Social Research.

- Piotroski, J. D., & Zhang, T. (2014). Politicians and the IPO decision: The impact of impending political promotions on IPO activity in China. Journal of Financial Economics, 111(1), 111–136. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfineco.2013.10.012

- Power, E. M. (1999). An introduction to Pierre Bourdieu’s key theoretical concepts. Journal for the Study of Food and Society, 3(1), 48–52. https://doi.org/10.2752/152897999786690753

- PwC. (2017). The long view: How will the global economic order change by 2050? https://www.pwc.com/gx/en/world-2050/assets/pwc-the-world-in-2050-full-report-feb-2017.pdf.

- Rouse, J. (2007). Practice theory. Division 1 Faculty Publications. Wesleyan University, Paper 43.

- Sadiq, S., & Governatori, G. (2015). Managing regulatory compliance in business processes. In J. vom Brocke, & M. Rosemann (Eds.), Handbook on Business process Management 2: Strategic alignment, governance, people and culture (2nd ed., pp. 265-288). Springer.

- Sandberg, J., & Dall'Alba, G. (2009). Returning to practice anew: A life-world perspective. Organisation Studies, 30(12), 1349–1368. https://doi.org/10.1177/0170840609349872

- Sandberg, J., & Tsoukas, H. (2011). Grasping the logic of practice: Theorising through practical rationality. Academy of Management Review, 36(2), 338–360. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203795248

- Sandberg, J., & Tsoukas, H. (2016). Practice theory: What it is, its Philosophical base, and what it offers Organization studies. In R. Mir, H. Willmott, & M. Greenwood (Eds.), The Routledge companion to Philosophy in Organization studies (pp. 184–198). Routledge.

- Schatzki, T. R. (1996). Social practices: A wittgensteinian approach to human activity and the social. Cambridge University Press.

- Schreier, M. (2012). Qualitative content analysis in practice. Sage Publications.

- Scott, W. R. (2015). Financial Accounting theory. Pearson.

- Sekaran, U., & Bougie, R. (2016). Research method for business: A skill Building approach (7th ed). John Wiley.

- Shleifer, A., & Vishny, R. W. (1997). A survey of corporate governance. The Journal of Finance, 52(2), 737–783. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6261.1997.tb04820.x

- Siddiqui, J. (2010). Development of corporate governance regulations: The case of an emerging economy. Journal of Business Ethics, 91(2), 253–274. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-009-0082-4

- Swartz, D. (2012). Culture and power: The sociology of Pierre bourdieu. University of Chicago Press.

- Tahir, S., Adegbite, E., & Guney, Y. (2017). An international examination of the economic effectiveness of banking recapitalisation. International Business Review, 26(3), 417–434. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ibusrev.2016.10.002

- Taylor, C. (1993). To follow a rule. In C. J. Calhoun, E. LiPuma, & M. Postone (Eds.), Bourdieu: Critical perspectives. Polity Press Publishers.

- Tittle, C. R., & Rowe, A. R. (1974). Certainty of arrest and crime rates: A further test of the deterrence hypothesis. Social Forces, 52(4), 455–462. https://doi.org/10.2307/2576988

- Utz, S. (2016). Is LinkedIn making you more successful? The informational benefits derived from public social media. New Media & Society, 18(11), 2685–2702. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444815604143

- Vincent, S., & Pagan, V. (2019). Entrepreneurial agency and field relations: A realist bourdieusian analysis. Human Relations, 72(2), 188–216. https://doi.org/10.1177/0018726718767952

- Waldo, G. P., & Chiricos, T. G. (1972). Perceived penal sanction and self-reported criminality: A neglected approach to deterrence research. Social Problems, 19(4), 522–540. https://doi.org/10.2307/799929

- Walters, G. D. (2018). Change in the perceived certainty of punishment as an inhibitor of post-juvenile offending in serious delinquents: Deterrence at the adult transition. Crime & Delinquency, 64(10), 1306–1325. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011128717722011

- Walters, G. D., & Morgan, R. D. (2019). Certainty of punishment and criminal thinking: Do the rational and non-rational parameters of a student’s decision to cheat on an exam interact? Journal of Criminal Justice Education, 30(2), 276–295. https://doi.org/10.1080/10511253.2018.1488982

- Wang, Y., Farag, H., & Ahmad, W. (2021). Corporate culture and innovation: A tale from an emerging market. British Journal of Management, 32(4), 1121–1140. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8551.12478

- Weber, R. P. (1990). Basic content analysis (2nd ed). Sage.

- Welsh, E. (2002). Dealing with data: Using NVivo in the qualitative data analysis process. Forum: Qualitative Social Research, 3(2), 1–9.

- World Bank. (2015). Nigeria Economic Report. Washington, DC. https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/handle/10986/23581

- Yoshikawa, T., & Rasheed, A. A. (2009). Convergence of corporate governance: critical review and future directions. Corporate Governance: An International Review, 17(3), 388–404. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8683.2009.00745.x

- Zheng, Q., & Chun, R. (2017). Corporate recidivism in emerging economies. Business Ethics: A European Review, 26(1), 63–79. https://doi.org/10.1111/beer.12132