?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

This study investigates how the European Union (EU) Directive (2014/95) on Non-Financial Reporting and employee representation within the board affects the extent and quality of employee-related disclosures. Using a sample of Swedish firms listed on the Nasdaq OMX Stockholm Exchange, we find that both the Directive and employee representation on the board positively affect the extent and quality of disclosures on employee-related matters. We document that employee-related disclosures are more precise and less uncertain among firms with employee representatives, although the level of uncertainty increases after implementing the Directive. Moreover, our interaction analysis indicates that the Directive and employee representatives affect employee-related disclosures independently. This finding suggests that both internal corporate governance and external regulation are important, and that the Directive ensures a minimum extent of disclosures at firms that lack internal governance mechanisms (i.e. employee representation on their corporate boards).

1. Introduction

This study considers how the European Union (EU) Non-Financial Reporting (hereafter NFR) Directive (2014/95) and employee representatives on the board (i.e. directors appointed by and drawn from company employees) affect employee-related disclosures. Specifically, we investigate the degree to which the extent and quality (measured by the information content and tone) of employee-related disclosures depend on (i) the Directive, (ii) employee representatives, and (iii) the interaction between the two.

NFR has become an essential part of corporate communications and is frequently discussed in corporate boardrooms (Cho et al., Citation2015). In response to social and environmental challenges, the NFR Directive was passed in 2014 and came into effect in 2018 (applied to the fiscal year 2017). The Directive provides minimum legal requirements and promotes the harmonisation of NFR across EU Member States (European Commission, Citation2014; Johansen, Citation2016; La Torre et al., Citation2018). However, the regulation of corporate reporting presents a dilemma. On the one hand, when corporate practices are regulated, companies have less freedom to make motivated and justifiable choices, and regulatory costs increase (Christensen et al., Citation2021; Grewal et al., Citation2019). Corporate social responsibility (CSR) activities and reporting can be used as signalling devices by firms to convey their superior social performance and gain a competitive advantage through market segmentation (cf. Arora & Gangopadhyay, Citation1995). On the other hand, the absence of regulation can result in undesired practices such as greenwashing and impression management through voluntary disclosure (Cho et al., Citation2010; Cuomo et al., Citation2022).

The outcome of any regulation depends on the institutional environment in which it is implemented (Christensen et al., Citation2021). While disclosure regulations generally result in increased corporate reporting, imposing mandatory disclosures is costly to implement and enforce (Christensen et al., Citation2021; Leuz & Wysocki, Citation2016). Previous studies show that regulation and corporate governance mechanisms can complement or substitute one another (Adams & Ferreira, Citation2012; Becher & Frye, Citation2011; Joskow et al., Citation1993). Thus, regulations that substitute for existing governance mechanisms may become inefficient. However, if regulation and corporate governance mechanisms act as complements, regulation could instead augment existing corporate governance resources (Becher & Frye, Citation2011). These insights call for consideration of how corporate governance features affect the outcomes of new regulations.

This study focuses on employee-related disclosures specifically, rather than on NFR generally, for the following reasons. First, employee representatives should have stronger incentives and more power to affect employee-related disclosures than general NFR. Second, existing environmental, social, and governance (ESG) scores that measure overall NFR quality lack comparability and completeness (Amel-Zadeh & Serafeim, Citation2018; Barker & Eccles, Citation2018; Christensen et al., Citation2022). By focusing on employee-related disclosures, we define our metrics using computerised textual analysis to make thorough and comparable assessments of disclosures. Lastly, we study employee-related disclosures because employee-related information is shown to drive value (Edmans, Citation2011; Li et al., Citation2022), whereas research on NFR more broadly shows mixed results concerning value implications (Gillan et al., Citation2021).

Employee representation is a corporate governance mechanism gaining increasing interest. Employees have legal rights to some form of board-level representation in no less than 19 European countries, and employee codeterminationFootnote1 is also debated in several countries without such legal rights (Conchon et al., Citation2015). For instance, in 2016, Theresa May promised to allow worker representation on corporate boards in the UK. As a consequence, the UK Corporate Governance Code (Financial Reporting Council, Citation2018) prescribed the appointment of one employee director as one of three available options to engage with the workforce. However, less than 4% of firms choose to do so (Fulton, Citation2019). In France, trade unions have supported reforms for enhanced employee representation, and Emmanuel Macron promised to extend codetermination during his presidential campaign (Rehfeldt, Citation2019). In the United States, Senator Elizabeth Warren proposed the “Accountable Capitalism Act” in 2018, according to which employees would elect 40% of board directors (Senate Bill 3348, Citation2018). Later, President-elect Joe Biden stated that his administration intended to promote worker empowerment and board diversity (Peregrine & Elson, Citation2020).Footnote2 This increased interest in employee representation underscores the need to learn more about how this governance mechanism interacts with regulations.

We investigate the employee-related disclosures of firms in Sweden, a country with strong legal support for worker codetermination (Vitols, Citation2010) and the world’s lowest threshold for board-level employee representation (Conchon et al., Citation2015). Sweden can be contrasted with Germany (the research setting of most studies on board-level employee representation). Whereas Germany has a two-tier board structure where employee representatives can have up to 50% of the supervisory board seats, Sweden has a one-tier board system where employee representatives can hold only a minority of board seats (Lopatta et al., Citation2020).Footnote3 Therefore, the board structure in Sweden is more similar to the UK and the United States, where employee representation is currently under debate (Kelley, Citation2018; O’Grady & Bowman, Citation2017). The easy access – limited power approach to employee representation in Sweden makes it an interesting research setting, as we can study the effects of employee representation in a sample of firms with greater variation in size. Additionally, moderate levels of employee representation are more likely to have healthy outcomes for firm performance (see Fauver & Fuerst, Citation2006, who underscore the importance of the “judicious” use of employee representation).

Based on a dataset of 1,222 firm-year observations of firms listed on the Nasdaq OMX Stockholm Exchange before and after the implementation of the Directive (2014–2019), we investigate the effect of the NFR Directive on disclosures, the effect of employee representatives (ER) on disclosures, and the interaction effect between these two factors on disclosures. To test the effect of employee representatives on employee-related disclosures, we use several measures to capture the extent and quality of disclosures and follow the Heckman specification to address endogeneity concerns related to selection bias. Furthermore, to test the simultaneous effect of the Directive and employee representatives, we use a difference-in-differences design with a matched sample, where ER and non-ER firms are matched based on observable factors.

Our results indicate that Swedish firms responded to the NFR Directive by providing more information about employees in non-financial reports. Furthermore, we find that ER firms, on average, disclose higher levels and more specific information on employee-related matters than non-ER firms. Concerning the tone of the text, we do not observe any significant changes before and after the regulation. However, for ER firms, we find that employee-related disclosures are less uncertain, less optimistic, less litigious, and include more concrete language and numerical terms. In the difference-in-differences analysis, we verify that the Directive and ER firms are positively related to employee-related disclosures. However, we find no significant interaction effect, indicating that both affect employee-related disclosures independently. In an additional analysis, we compare the effect of the passage of the Directive in 2014 and the implementation in 2017 and find that a significant change in disclosures occurred in the implementation stage (mitigating concerns that the parallel trends assumption is violated). Finally, we examine alternative ESG performance measures and find that ER firms are more likely to score highly for the social pillar, while the Directive positively and significantly affects the overall ESG score and all underlying ESG pillars.

This study adds to the literature on the effects of mandatory NFR (Cuomo et al., Citation2022; Fiechter et al., Citation2022; Grewal et al., Citation2019) by analysing its interplay with employee representation on corporate boards. The results indicate that both employee representation and external NFR regulation can enforce disclosures on employee-related matters. There is growing research on mandated employee-related disclosures using measures solely based on statutory requirements (Day & Woodward, Citation2004) or requirements combined with the Global Reporting Initiative (GRI) guidelines (Agostini et al., Citation2022; Costa & Agostini, Citation2016). We complement this research by using a set of measures to analyse the content of employee-related disclosures, including a newly constructed and more extensive wordlist, the tone of the text, and the extent of such disclosures. Moreover, by studying employee representatives, we learn how board structure relates to non-financial reporting (Dienes & Velte, Citation2016). This study also extends the knowledge of how employee representatives affect board decision-making (Blandhol et al., Citation2020; Fauver & Fuerst, Citation2006; Jäger et al., Citation2021, Citation2022; Lin et al., Citation2018). Specifically, by illustrating that employee representatives enhance employee-related disclosures, we extend the discussion on how employees contribute to the quality of corporate reporting (Arslan-Ayaydin et al., Citation2021; Gleason et al., Citation2021; Lopatta et al., Citation2020; Overland & Samani, Citation2021) and the quality of employee-related disclosures (Kent et al., Citation2021; Kent & Zunker, Citation2017).

2. Research setting

2.1. The NFR Directive (2014/95) and its adoption to Swedish law

The NFR Directive (2014/95) emerged as a response to stakeholders’ higher demands for transparency in NFR (La Torre et al., Citation2020). The European Commission acknowledged that NFR is important for measuring, monitoring, and managing corporations’ impacts on society, stating that it should cater to the information needs of all relevant stakeholders (EU: C/2017/4234). In this vein, starting from the 2017 financial year, the NFR Directive mandates NFR for companies with more than 500 employees, total assets exceeding EUR 20 million, or sales exceeding EUR 40 million (European Commission, Citation2014, Citation2017). To harmonise regulation for NFR across EU countries, Member States had to pass the Directive as national legislation until December 2016, with the option to extend requirements beyond the mandates of the Directive (Fiechter et al., Citation2022).

In 2016, the NFR Directive was adopted as part of the Swedish Annual Accounts Act (SFS 2016:947), mandating the NFR for the financial year 2017.Footnote4 Swedish law goes further than mandated by the NFR Directive and applies to all Swedish companies that meet two of the following three thresholds: (i) more than 250 employees, (ii) net turnover exceeding SEK 350 million, and (iii) total assets exceeding SEK 175 million. These firms are obliged to provide information on the policies, processes, and outcomes of their sustainability practices concerning environmental protection, social responsibility and treatment of employees, respect for human rights, anti-corruption and bribery, and diversity on corporate boards.

Implementing the NFR Directive in the national legislation of EU Member States has led to increased disclosures, but quality varies across companies and countries due to the flexible legislative approach (Johansen, Citation2016) and a lack of coherent guidance and quality assessment (Arvidsson & Dumay, Citation2022). The NFR Directive was recently renamed the Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive (CSRD), and the European Commission proposed bringing “sustainability reporting on a par with financial reporting” by developing European sustainability reporting standards (EFRAG, Citation2021). Considering the ongoing nature of this process, our study provides timely and relevant insights into the roles and effects of NFR regulations and corporate governance mechanisms in shaping corporate social and environmental disclosure practices.

2.2. Employee representation in Sweden

In Sweden, employees are granted representation through two legal acts: the Co-Determination Act (Lag (1976:580) om medbestämmande i arbetslivet) and the Board Representation Act (Lag (1987:1245) om styrelserepresentation för de privatanställda).

The Co-Determination Act stipulates that conflict measures such as strikes and lockouts are not allowed if the employer has a collective agreement with a labour union,Footnote5 which is a strong incentive for the employer to enter into a collective agreement in the first place. Under the same act, employees are granted the right to negotiate all the major operational changes that affect them. This act also grants union representatives the right to access vital company information, as employers regularly provide data on production, financials, and guidelines for employee policy. Union representatives can also access company books, accounts, and other documents if necessary to safeguard the interests of their members.

The Board Representation Act grants employees, companies with collective agreements, and more than 25 employees the right to appoint two representatives to the board of directors.Footnote6 These appointments are made through the local trade union of the company, and the representatives should be employees. In addition, a third employee representative can be appointed to the board of firms with 1,000 employees or more. While the Board Representation Act grants the right to appoint employee representatives, the Company Act (Aktiebolagslag (2005:551)), stipulates that employee representatives have the same rights and responsibilities as shareholder-elected directors. These responsibilities include a duty to promote the company’s interests (not only employees’) and the risk of litigation if they fail to uphold this duty.Footnote7 This litigation risk presents a cost that likely explains, in part, why local trade unions choose to appoint employee representatives in less than half of the companies in our sample.Footnote8

3. Hypothesis development

3.1. The effect of the NFR Directive (2014/95)

It is argued that NFR fosters transparency about corporate sustainability impacts (Bebbington et al., Citation2014), and contributes to corporate accountability by addressing the interests of broader stakeholder groups (Herremans et al., Citation2016). Moreover, NFR is valued by investors because it can decrease capital costs (Dhaliwal et al., Citation2014). However, NFR has also been criticised for its lack of quality (Boiral, Citation2013; Patten, Citation2012) and for being used as a tool by firms to manage stakeholder perceptions (Cho et al., Citation2012), thus motivating the regulation of NFR.

The stated goal of the NFR Directive is to improve firms’ disclosures by establishing a minimum legal requirement for NFR and coordinating the national provisions for NFR (European Commission, Citation2014; Johansen, Citation2016; La Torre et al., Citation2018). By establishing a minimum legal requirement, firms that previously did not disclose non-financial information are now required to do so. Therefore, with the NFR Directive, the total extent of NFR should increase. However, Hoffmann et al. (Citation2018) report that companies new to NFR often provide incomplete reports that fail to meet the requirements set out by the NFR Directive. Similarly, Carungu et al. (Citation2021) find that the quality of NFR does not increase for companies that move from voluntary to mandatory regimes. Moreover, Fiechter et al. (Citation2022) document that firms, on average, increase their CSR activities in response to the regulation but that firms with low pre-Directive levels of CSR are more likely to do so (indicating a “catching-up” effect).

A few studies investigate how regulation drives the disclosure of employee-related matters. Day and Woodward (Citation2004) study employee-related disclosures in UK companies following the enactment of the UK Companies Act of 1985, which mandated such disclosures. The authors conclude that companies disregard statutory disclosures and that disclosures meet only the minimum requirements. Costa and Agostini (Citation2016), in their study of Italian firms concerning a 2007 legal decree on NFR, report that the regulation led to more, but not better quality, disclosures on employee-related matters. Further, Agostini et al. (Citation2022) analyse the effect of the NFR Directive on NFR and firms’ financial performance. Their results, like those of Costa and Agostini (Citation2016), indicate that the extent of employee-related disclosures increased, while disclosure quality did not. However, the lack of a visible effect on the quality of these disclosures could be partly due to the rather small sample sizes in these studies; Costa and Agostini (Citation2016) examine a total of 96 reports, and Agostini et al. (Citation2022) study only 20 Italian firms.

In sum, the NFR Directive is expected to lead to an overall increase in the extent and possibly quality of employee-related disclosures. To examine this, we provide several measures that capture the extent of disclosures and more qualitative features, such as the content and tone of the text. Accordingly, we hypothesise as follows:

H1: The implementation of the EU Directive (2014/95) is positively associated with the extent and quality of employee-related disclosures

3.2. Employee representatives and employee-related disclosures

NFR is largely discretionary and affected by firm-based and managerial incentives. Managers weigh the costs and benefits associated with disclosing non-financial information, where economic incentives, litigation risks, and socio-political pressures are shown to explain NFR outcomes (Brammer & Pavelin, Citation2006; Simnett et al., Citation2009). Prior research documents that corporate governance mechanisms such as the board of directors constrain managers from opportunistically manipulating discretionary narrative disclosures (García Osma & Guillamón-Saorín, Citation2011; Lee & Park, Citation2019).

One of the board of directors’ primary tasks is to monitor managers’ behaviour, and board composition is crucial for the quality of financial reporting (Adams et al., Citation2010; Armstrong et al., Citation2010) and is related to NFR. For instance, firms with more independent directors provide higher quality non-financial disclosures and are more likely to support managerial compensation tied to sustainability-related performance (Hong et al., Citation2016). Employee representatives can contribute to board monitoring as they constitute informed and knowledgeable monitors and reduce agency costs by transferring inside information to other board members (Fauver & Fuerst, Citation2006; Lin et al., Citation2018). Overland and Samani (Citation2021) find that employee representatives in Swedish companies contribute to better earnings quality through their engagement in board monitoring. Moreover, Gleason et al. (Citation2021) state that firms with worker representatives in Germany have better tax planning and monitoring, and lower real earnings management, which helps avoid wage cuts or job losses. One can assume that employee representatives adopt an even more vigilant stance on matters closely related to their core interests.

The point that employee representatives are knowledgeable is also in line with resource dependency theory (Hillman & Dalziel, Citation2003; Pfeffer & Salancik, Citation1978), underscoring the benefits that board directors provide in the form of advising. Hillman and Dalziel (Citation2003) point out that a proper understanding of boards’ monitoring efficiency incorporates a view of board capital (directors’ human and relational capital) in addition to the more extensively studied aspects of incentives and independence. Moreover, Hillman et al. (Citation2000) outline which types of resources directors bring to the board (e.g. firm expertise, channels of communications between firms, legitimacy and expertise, and connections with powerful groups in the community). The addition of such resources by employee representatives can manifest themselves in several ways. For instance, employee representatives possess firm-specific knowledge (Fauver & Fuerst, Citation2006; Overland & Samani, Citation2021) that should add value in the form of advice. Furthermore, employee representation creates an institutionalised communication channel between labour and capital, which through repeated interactions, mitigates hold-ups and other problems (Jäger et al., Citation2021, Citation2022). Levinson (Citation2001) reports that the majority of surveyed chairpersons in Sweden believe that employee representatives contribute to a positive, cooperative climate, that board decisions become rooted among employees, and that it is easier to make tough decisions. Employee representation also facilitates access for central stakeholder groups such as labour unions and politicians.Footnote9

Resource dependency has been applied in studies focusing on the link between boards and sustainability performance (Dixon-Fowler et al., Citation2017) and sustainability reporting (Dienes & Velte, Citation2016; Herremans et al., Citation2016). For instance, Herremans et al. (Citation2016) find that resource dependency explains stakeholder engagement strategies and that dependencies on different stakeholders (e.g. employees) determine whether firms adopt informing, responding, or involving engagement strategies. Employee representatives also increase board diversity, as they typically come from different backgrounds than other directors and can offer complementary experiences and perspectives. Employee representatives thereby contribute to the functional diversity of boards (Pelled et al., Citation1999), which is especially beneficial for teams that engage in debates (Jackson et al., Citation2003). Abbott et al. (Citation2012) assert that diverse boards are more likely to challenge assumptions and make inquiries. Similarly, employee representatives can improve diversity and promote board performance by generating better discussions and communication. For instance, employee representatives may promote risk-reducing measures to a more considerable degree (Lin et al., Citation2018; Overland & Samani, Citation2021), and employee representatives often raise issues related to working conditions and health risks (Jäger et al., Citation2022).

Although the direct relationship between employee representation and employee-related disclosures is not explicitly documented, few studies consider how employees influence reporting on employee-related matters. Kent and Zunker (Citation2017) and Kent et al. (Citation2021) report that “employee power,” proxied by employee ownership and concentration, is positively related to employee-related disclosures. We examine whether employee representation on the board (another channel in which employees can exercise power) improves the disclosure of non-financial information, especially concerning employee-related disclosures. Informed employees who are part of the board have a direct interest in the well-being of employees. Therefore, their involvement in board decision-making can make managers more forthcoming with employee-related disclosures. Therefore, concerning employee representatives, we hypothesise the following.

H2: Employee representation is positively associated with the extent and quality of employee-related disclosures.

3.3. The interaction effect between the NFR Directive and employee representatives

The NFR Directive possibly impacts the NFR of firms with employee representatives (ER firms) differently than firms without representatives (non-ER firms). The Directive could reinforce the positive relationship between employee representation and the quality of disclosures of employee-related matters; that is, the Directive could complement the effect of employee representatives (cf. Becher & Frye, Citation2011). The Directive would then help unleash the positive effects of better access to firm-specific knowledge (Fauver & Fuerst, Citation2006) and more functional diversity (Hillman & Dalziel, Citation2003; Jackson et al., Citation2003) from employee representatives. However, the Directive could instead act as a substitute for employee representation (cf. Joskow et al., Citation1993). If employee representatives have successfully promoted voluntary disclosures of employee-related matters before the Directive, it is less likely that the Directive creates additional informational value. At worst, the regulation could even undermine previous achievements made by employee representatives if it steers NFR downwards toward new legal minimum requirements (cf. Bénabou & Tirole, Citation2006; Rajgopal & Tantri, Citation2018).

Thus, it is unclear how the effect of mandatory NFR varies for ER and non-ER firms. If employee representatives successfully promoted more disclosures before the Directive, one might not see any significant incremental change in employee-related disclosures in ER firms. Instead, the main effect is expected to materialise for non-ER firms. Alternatively, the effect of a mandatory requirement can help empower employee representatives to require more high-quality disclosures. Hence, without predicting the direction of change, we compare the effect of the NFR Directive on employee-related disclosures in ER and non-ER firms. Accordingly, we hypothesise as follows:

H3: The relative change in the extent and quality of employee-related disclosures following the implementation of the EU Directive (2014/95) varies between ER and non-ER firms.

4. Research design

4.1. Multivariate models

We examine how the extent and quality of non-financial disclosures on employees vary before and after the implementation of the EU Directive (2014/95/EU) as of 2017 in Sweden (Hypothesis 1) by estimating the following OLS model:

(1)

(1) where EM_Disclosure represents a set of separate dependent variables that measure the extent and quality of non-financial disclosures on employees; a detailed description of disclosure variables is provided in section 4.2, Disclosure variables; Post represents the effect of the EU Directive, which came into force for the fiscal year 2017 and is a dummy variable equal to one for financial years 2017–2019 and zero for financial years 2014–2016Footnote10; Control constitutes firm and governance variables that, based on previous studies (e.g. Kent et al., Citation2021; Khan et al., Citation2020), are expected to affect non-financial disclosures.

We control for firm size (logarithm value of total assets, lnTA), profitability (return on assets RoA), growth opportunities (logarithm value of market-to-book ratio, lnMB), firm leverage (total debt divided by total equity, Lev), ownership (percentage of shares held by controlling shareholders, Blockholders), and firm age (number of years since a firm was founded, FirmAge).Footnote11 We also control for the structure of the board of directors, including the size of the board (i.e. the total number of shareholder-elected directors on the board, BoardSize), the percentage of outside directors on the board (OutsideDr),Footnote12 and whether the CEO is a board member (CEOonBoard). We include the effect of employee participation on the board in this model as a control variable (D_ER). Finally, we control for industry-fixed effects (two-digit SIC codes) and year-fixed effects in all the regression models.

Next, we focus on the effect of employee representatives on the extent and quality of employee-related disclosures (Hypothesis 2), considering the potential endogeneity problem related to selection bias. Specifically, we follow Heckman’s (Citation1979) two-stage procedure to control for the potential selection bias associated with employee representatives’ choice to participate on the board of directors. Model 2 presents the first stage, where we estimate the probability of employees participating in the board of directors in a probit model. In addition to all control variables, we include two exogenous variables excluded from the second-stage regression. These exogenous variables are not associated with any of our outcome variables in the main regressions (fulfilling the reliability criterion) but are correlated with employee representatives on the board (fulfilling the relevance criterion) (Lennox et al., Citation2012). First, we use a dummy variable that equals one for registered firms located in municipalities outside the capital region, and zero otherwise (OutsideCapital). This variable is expected to be highly correlated with employee representation on the board because local unions are more likely to elect employee representatives due to fewer alternative employment possibilities (Gregorič & Rapp, Citation2019; Overland & Samani, Citation2021). Second, we use the average percentage of employee representatives on the boards of firms in the same industry category each year (ERRIndustry) as another instrument, as firms have employee representatives on the board if there is a tendency to have employee representation at other firms in the same industry (Fauver & Fuerst, Citation2006; Overland & Samani, Citation2021).Footnote13

(2)

(2) We calculate the inverse Mills ratio using estimated parameters from the probit model and include that in Model 3 (the second stage), where we test the association between employee participation on the board and employee-related disclosures.

(3)

(3) D_ER indicates employee representation on the board and is a dummy variable equal to one if there are employee representatives on the board, and zero otherwise; Control constitutes firm and governance variables, as described under Model 1, and industry and year fixed effects;

represents the inverse Mills ratio and controls for sample selection bias.

In Model 4, using a matched sample, we investigated the interaction effect between the NFR Directive and employee representatives (Hypothesis 3) using the following difference-in-differences model:

(4)

(4) where the interaction variable

captures the differential effect of the EU Directive on ER and non-ER firms. Specifically, we the interaction coefficient indicates whether there are significant differences in disclosures between the two groups before and after regulation (

). This design also allows us to separately examine the effect of regulation in firms without employee representatives (β1) and in firms with employee representatives (β2 + β3). In our analysis, we match the treated group (firms with employee representatives) with the control group (firms without employee representatives) using a propensity score matching design.Footnote14 We include the inverse Mills ratio (

), as described above, to address the selection issues and minimise the underlying differences between the treatment and control groups.Footnote15

Detailed descriptions of all variables are presented in .

Table 1. Variable definition.

4.2. Disclosure variables

Earlier disclosure research focused on the extent, informativeness, and tone of narratives (see Loughran & McDonald, Citation2016). Following recent disclosure studies (e.g. Hassan, Citation2022; Paananen et al., Citation2021), we use a set of variables to measure both the extent and quality (i.e. content and tone) of employee-related disclosures. With these variables, we capture how much they disclose (the extent of disclosures), what they disclose (the content of disclosures), and how they disclose it (the tone of disclosures).

Specifically, we first measure the extent of information, meaning the quantity of information, as prior research on non-financial reporting shows that the extent of information can indicate its sufficiency and transparency in reports (Hassan, Citation2022; Vanstraelen et al., Citation2003). To capture disclosure quality (content and tone), we performed a textual analysis of the extracted disclosures and use the word count approach (also known as the “bag-of-words” technique). First, we capture the content of employee-related disclosures by creating a wordlist specific to employees and their well-being, based on existing social and employee matters guidelines. Second, we measure the tone of the text across several dimensions using wordlists developed by Loughran and McDonald (Citation2011) and provided in DICTION. We describe our disclosure variables in detail in Online Appendix Section 1.

4.3. Sample and descriptive statistics

Our sample consists of all firms listed on the Nasdaq OMX Stockholm Exchange between 2014 and 2019.Footnote16 shows the sample selection procedure (Panel A) and the number of ER and non-ER firms each year (Panel B). The initial sample includes 1,403 firm-year observations with available annual reports and information on the board of directors (hand-collected from these reports). 86 firm-year observations are dropped due to missing non-financial information in the annual reports or a lack of English versions of the reports. An additional 109 observations are dropped because of the lack of data on firm-specific variables on the S&P Capital IQ platform. The final sample consists of 1,222 firm-year observations, of which 511 (711) are related to ER (non-ER) firms.

Table 2. Sample.

, Panel A, presents the descriptive statistics for all variables. Almost 42% of firm-year observations have employee representatives on the board. The average percentage of employee representation in the whole sample is around 10%, indicating a moderate representation.Footnote17 The mean values of other board-related variables indicate that Swedish boards, on average, have 7 members (excluding employee representatives); most members are outside directors (68%), and in 37% of observations, the CEO sits on the board as an ordinary member. Among the disclosure variables, there are, on average 44 references (References) on employee-related matters in non-financial reports, while the average coverage (Coverage) of employee information (as scaled by the whole information in the non-financial report) is 5%. On average, employee-related words (EM_Words) account for 18% of the total disclosures about employees. Overall, the mean value of Coverage indicates that a small proportion of the whole non-financial report conveys information about employees, while the average value of EM_Words suggests that only about one-fifth of disclosures about employees contain relevant and specific information. The average values of NumericalTerms and Concreteness are about 51.83 and 17.87, respectively.Footnote18 The mean values of LM_positive (4.13%), LM_uncertain (3.53%), and LM_litigious (1.99%) indicate that a small proportion of the text conveys thematic language. Firm-specific variables are presented in logarithmic values (lnTA and lnMB) or are winsorized at the 1% level (RoA and Lev) to address the potential outlier problem.

Table 3. Descriptive statistics and mean comparison analysis.

In Panel B, we compare the mean value of the disclosure variables in ER and non-ER firms before and after the implementation of the Directive. The results indicate substantial differences between the mean values of the disclosure variables, especially when comparing ER and non-ER firms. Specifically, in ER firms, texts on employees have a significantly higher number of employee-related words and more references and coverage. Furthermore, these texts include significantly more numerical features and are more concrete, as the average scores of NumericalTerms and Concreteness are significantly higher in ER firms. The mean values of the tone variables (LM_positive, LM_uncertain, and LM_litigious) also indicate that in ER firms, the texts are significantly less optimistic, less uncertain, and less litigious. These results suggest that in ER firms, employee-related disclosures are more informative and focused (cf. Melloni et al., Citation2017). When comparing firms before and after the regulation, we observe that there is more information about employees in non-financial reports after the implementation of the Directive, as shown by the significantly higher mean values of References, Coverage, and EM_words. However, there are no significant differences between the mean values of the tone variables pre – and post-regulation.

In Panel C, we carry out a mean comparison analysis for disclosure variables before and after the Directive and in ER and non-ER firms. The mean values are significantly higher in both groups, indicating that an increase followed the implementation of the Directive in 2017 in employee-related disclosures for all firms. However, the major differences between ER and on-ER firms are still noticeable; for example, the mean values of References and Coverage in non-ER firms’ post-regulation are considerably lower than the corresponding mean values in ER firms’ pre-regulation. Furthermore, the mean difference in EM_Words before and after the regulation in ER firms (0.013) is higher than the corresponding mean difference in non-ER firms (0.009). Regarding the tone variables, there are no substantial changes after the regulation, except concerning the uncertainty tone (LM_uncertain) that has increased in ER firms after the regulation.

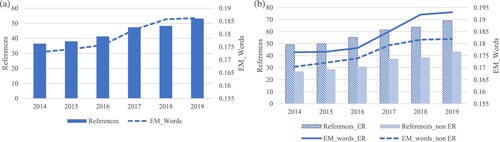

Next, we show the evolution of the two key variables related to the extent (References) and content (EM_Words) of employee-related disclosures over time in . (a) shows the general trend for the whole sample, while (b) partitions the sample into ER and non-ER firms. Both figures illustrate a sharp increase in employee-related disclosures starting in 2017 when the NFR Directive was transposed into national legislation. The extent of employee-related disclosures continued to increase in 2018 (an indication of some later adopters), while the increase in disclosures levelled off in 2019. (b) shows that the extent of employee-related disclosures is considerably higher in the reports provided by ER firms during all the observed years. Both ER and non-ER firms show similar dynamics as the extent of employee-related disclosures has significantly increased in both groups after implementing the Directive (consistent with the univariate analysis in , Panel C). Furthermore, comparing the relative increase in the proportion of employee-related words (EM_Words), we can see that ER firms have continued to increase their disclosures in 2018 to a greater extent than non-ER firms, while for both groups, there is a slowdown in the increase in 2019.

Figure 1. (a) Employee-related disclosures over time (whole sample) (b) Employee-related disclosures over time (in ER and non-ER firms).

Note: The figure plots two disclosure variables over time. The variables are the number of paragraphs with employee-related information (Reference) and the number of employee-related words divided by the total number of words in employee-related disclosures (EM_Words). The time span includes pre – (2014–2016) and post-regulation (2017–2019) periods. (a) and 1(b) illustrate the trend in the whole sample and separately in ER and non-ER firms, respectively.

5. Results

shows the results for Models 1 (Panel A) as well as Model 2 and 3 (Panel B). The dependent variables are related to the extent (References and Coverage) and content (EM_Words) of employee-related disclosures.Footnote19 The independent variable of interest in Panel A is the effect of the NFR Directive as of 2017 (Post). Consistent with expectations and in line with the results of the univariate analysis, there is a significant increase in employee-related disclosures after 2017. The coefficients of Post are consistently positive and significant in all three columns, indicating that there is significantly more reporting on employees and employee-related matters after the implementation of the Directive. For example, the coefficient of Post concerning References (coefficient:13.055; t-stat:5.87) indicates that, on average, there are 13 more references (number of paragraphs including employee disclosures) after the Directive, while the coefficient of Post concerning EM_Words (coeff:0.012; t-stat:5.71) indicates that the average value of EM_Words increases by approximately 6.66% after the regulation (0.012/0.180). Regarding the control variables, we find that larger and more profitable firms (lnTA and RoA) provide more reporting on employee-related matters, while firms with more concentrated ownership report less. Concerning the board variables, D_ER is consistently positive and significant, whereas Board Size is only positive and significant concerning References. Interestingly, the effect of CEOs on the board (CEOonBoard) is consistently negative and significant for all three dependent variables.

Table 4. EU Directive, employee representatives and employee related disclosures.

The results in Panel BFootnote20 focus on the association between employee representation on the board and disclosure on employee-related matters, controlling for selection bias. The probit regression results (first stage) reveal that several firm factors affect the probability of employee representation, underscoring the importance of firm-specific differences between ER and non-ER firms. Specifically, ER firms are significantly larger (lnTA), older (FirmAge), less profitable (RoA), less levered (Lev), and have more concentrated ownership (Blockholder). These results suggest that employees are more inclined to sit on the boards of larger and older firms (Berglund & Holmén, Citation2016) and when there is a stronger need to protect their interests (Forth et al., Citation2017). The two exogenous instruments are significant and positive in line with expectations (fulfilling the relevance condition). In the second-stage regressions, controlling for all firm-specific variables and the calculated inverse Mills ratio, we find that the coefficient of D_ER is positive and significant concerning all measures of employee disclosure. In untabulated results, we also examine the effect of employee representatives’ proportion (ERR) on disclosure variables and find consistent results, that is, ERR is positively and significantly associated with the extent and information content of employee-related disclosures.

shows the effect of the EU Directive on employee-related disclosures and compares ER firms (treatment group) and non-ER firms (control group). The results are based on a matched sample of 863 firm-year observations, in which firms in the two groups are matched using the propensity score (PS) matching technique. We also include the inverse Mills ratio to address endogeneity. The coefficient of D_ER indicates the estimated mean difference between the treatment and control groups before the implementation of the EU Directive. The significant coefficients of D_ER (concerning References and EM_Words) indicate significant differences between the two groups, independent of regulation. The coefficient of Post shows the effect of regulation in non-ER firms and is positive and consistently significant, indicating that, in non-ER firms, there is a significant increase in employee-related information in non-financial reports after the implementation of the EU Directive. The coefficient of Post × D_ER indicates whether the expected mean change in disclosure variables before and after the regulation is significantly different in the two groups. The insignificant coefficient of Post × D_ER indicates that both ER and non-ER firms have increased employee-related disclosures.Footnote21

Table 5. Implementation of EU regulation in ER and non-ER firms.

In Panel B, the estimated margins – that is, the expected means of outcome variables in ER and non-ER firms before and after the regulation – corroborate these results and show that the extent of disclosures has increased in non-ER firms, while it is still considerably lower than the disclosures in ER firms. For instance, the estimated margin for EM_Words post-regulation (0.18) reached the corresponding estimated margin in the ER firms’ pre-regulation (0.181).

shows the results for the tone of employee-related disclosures, where Panel A (Panel B) corresponds to Model 3 (Model 4). In the untabulated analysis, we also examine the effect of Post on tone variables (Model 1), but given the results from the mean comparison analysis, we do not expect, nor do we find any significant changes in tone variables before and after the regulation. In Panel A, the results indicate positive and significant associations between D_ER and dictionaries that imply a concrete language (including Numerical terms and Concreteness) but negative and significant associations between D_ER and tone variables that connote positivity (LM_positive), ambiguity (LM_uncertain), and legitimacy (LM_litigious). These results suggest that overstatement and ambiguity are avoided in ER firms, and more neutral and precise statements are preferred in texts about employees. Panel B compares the tone variables before and after the regulation in a matched sample of ER and non-ER firms and shows insignificant coefficients for Post and Post × D_ER. These results suggest that changes in employee-related disclosures after the regulation are primarily related to the extent and content of information and less to the qualitative attributes of the text. An exception is found concerning LM_uncertain, as the text is significantly more uncertain after regulation. The estimated margins (in Panel C) corroborate this result, showing that among tone variables, there is an increase in uncertain and litigious tones in ER firms after the regulation.

Table 6. Analysis of the tone of employee related disclosures.

6. Additional analysis and robustness check

We perform several additional analyses and robustness tests to investigate whether our results are driven by measurement choices, year differences, or selection biases. All these additional tests and corresponding tables are provided in Online Appendix Sections 2 and 3. In this section, we summarise these tests.

First, to see whether firms have made changes in disclosures before 2017 but after the passage in 2014, we define two Post variables: Post1 refers to the years after the Directive’s passage and before its implementation (2014–2016), and Post2 refers to the years after the implementation of the Directive (2017–2019). We include both dummies in the regression, extend the sample to include 2013 (as the base year for comparison analysis), and find that the effect of the Directive materialised in Sweden from 2017 (when the Directive came into force).

Second, to compare our disclosure variables with ESG scores (commonly used for capturing the overall quality of NFR), we collect data from Refinitiv ESG Research Data (Refinitiv, Citation2021) on total ESG scores and the ESG indicators corresponding to the Environmental (E), Social (S) and Governance (G) pillars. We find that the coefficients for Post are consistently positive for all ESG variables, supporting the positive effect of the NFR Directive on firms’ ESG disclosure. We also find that D_ER is positive and significant (at the 1% level) concerning D_ESG_S, indicating that the effect of employee representatives is primarily related to the social pillar.

Third, we perform several robustness tests and obtain consistent results. These tests include (i) accounting for the “first-year” implementation impact by using 2018 and 2019 as the post-period, (ii) excluding firms that have changes in the board structure concerning employee representation over time (while only 15 unique companies go through any changes), and (iii) controlling for the endogeneity problem by performing two-stage least square (2SLS) regressions. In the first stage of the 2SLS regression, we include all control variables together with the instruments used in the Heckman model; in the second stage, we use the predicted value of D_ER (or ERR).

7. Conclusion

We investigate how the NFR Directive affects corporate disclosures on employee-related matters and how it interacts with the governance mechanism of employee representation. Using a sample of firms listed on the Nasdaq OMX Stockholm Exchange (2014–2019), we find that Swedish firms responded to the NFR Directive by increasing their reporting on employee-related matters. However, the NFR Directive does not substitute for the effect of employee representation; firms with employee representatives provide higher quality employee-related disclosures compared to firms without such representation (both before and after the implementation of the Directive). We argue that the positive effect of employee representation on employee-related disclosures is driven by the human and relational capital provided by incentivized employee representatives on corporate boards. However, the potential endogeneity problem requires caution when establishing a direct causal effect.

We also observe an increase in the tone of uncertainty following the implementation of the Directive in firms with employee representatives. We argue that this increase in uncertainty may be partly due to the approach taken by the Directive, including a combination of abstract formulations of the minimum requirements and voluntary disclosures (Johansen, Citation2016), which opens interpretations and discretion during the implementation stage. Alternatively, given that there are words in the uncertainty wordlist related to risk and that the Directive also requires more descriptions of risks related to employee matters, the increase in a report’s uncertainty tone could be evaluated as a positive outcome. Thus, our results on this measure should be interpreted with caution. Future research on the effects of the Directive could explore how an uncertain tone relates to disclosure quality and risk-related information.

In the context of the recent evaluation and re-framing of the Directive as CSRD and the development of the European sustainability reporting standards (EFRAG, Citation2021), our study on the effects of the NFR Directive provides timely and relevant insights into how mandatory NFR interacts with existing corporate governance mechanisms. Overall, our results suggest that the Directive contributes to more reporting on employee matters, particularly important when there is no substitute governance mechanism, that is, no employee representation. The introduction of the NFR Directive is the first attempt in the EU to regulate the minimum requirements for NFR; thus, whether companies symbolically comply with the minimum requirements or are also accountable to stakeholders’ needs and concerns remains a question worth further investigation.

The lack of monitoring and enforcement concerning NFR requirements may result in symbolic practices “by enacting the requirements rather than with the substantive intent of making organisations accountable” (Day & Woodward, Citation2004, p. 56). Although we do not find that the Directive acts as a substitute or complement for employee representatives’ monitoring, we concurred with Adams and Ferreira (Citation2012) that board monitoring may provide significant complements to regulatory pressure. Consequently, future research should further investigate how compliance with NFR requirements depends on existing governance mechanisms. For example, considering recent changes to improve and harmonise the quality of environmental disclosures (in line with the European Green Deal Agenda), policies for the inclusion of knowledgeable directors to represent the voice of nature (Quattrone, Citation2022) on corporate boards could enhance sustainability reporting.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Word (76.5 KB)Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the Guest Editors and Reviewers for their insightful comments and suggestions, which have led to substantial improvements in the paper. We also appreciate the helpful comments and suggestions from Taylan Mavruk, Tom Berglund, Emmeli Runesson, and Jan Marton. We thank the participants at the 23rd Annual Conference on Financial Reporting and Business Communication (Henley Business School 2019), the 11th Nordic Corporate Governance Network workshop (BI Oslo 2019), and the workshop on Sustainability Reporting, Regulation & Practice (Essex Business School and Norwich Business School, 2021).

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Codetermination refers to the different laws, by-laws, and collective agreements that grant workers some influence over company decisions that concern employees.

2 A conservative case for enhanced codetermination also has been made, where Republicans Marco Rubio and Jim Banks proposed a bill in February 2022 that supported board-level (albeit non-voting) worker representation (Cass, Citation2022).

3 In Germany employee representatives can have 50% (33%) of the supervisory board seats in firms with at least 2,000 (500) employees, whereas in Sweden there can be 2 (3) employee representatives in firms with at least 25 (1,000) employees (see Section 2).

4 There were no mandatory guidelines for external CSR reporting in Sweden before this law was implemented, except for state-owned companies, which needed to disclose non-financial information based on the GRI guidelines.

5 Data on which firms have entered into collective agreements with trade unions is not readily available as it is not mandated in corporate reporting. However, Kjellberg (Citation2022) reports that, in 2020, 85% of the entire workforce (ages 16–64) in the private sector was covered by collective agreements and that employees without collective agreements were predominantly found at smaller firms. In 2015, one-third of firms with only 1–4 employees had collective agreements, whereas 83.5% of firms with 20–49 employees had entered into collective agreements. For larger firms, the coverage is even greater, as a survey in 2017 finds that 94% of firms with 250 employees or more had entered into collective agreements (Calmfors et al., Citation2018). Therefore, even though we cannot directly observe which listed firms have collective agreements, we assume that all of them do. However, we acknowledge that there are a few exceptions.

6 The rights to employee representation in Sweden are more widespread than in other EU countries. For example, in France, private companies with more than 1,000 employees must have employee representation, while in Germany, the corresponding figure is 500. For a detailed comparison of employee representation, see Conchon et al. (Citation2015).

7 It should be noted, however, that the stipulated duty toward the company has a wider scope than the fiduciary duty toward shareholders, which is distinct from such duties found in, e.g., the United States.

8 For more details on the Swedish system of employee representation, see Levinson (Citation2001) and Overland and Samani (Citation2021).

9 For instance, Levinson (Citation2001) reveals that most employee representatives are also chairpersons of the local trade union and that they typically confer with the local trade union before board meetings. There is also a close connection between labor unions and the largest Swedish political party, and many politicians at all levels (i.e., local, national, and European) have a background in the labor movement (e.g., as employee representatives).

10 As mentioned in Section 2, the NFR requirements in Sweden target firms with 250 employees or more (in addition to the requirements for total assets and sales). We check whether all listed firms in Sweden must adopt the Directive and find that only four companies fall outside these requirements, which should have little effect on our results.

11 We do not explicitly control for whether a firm has entered into a collective agreement because it is not directly observable in our data and because there is hardly any variation – almost all firms in the sample have collective agreements (see footnote 5).

12 Independent or outside directors are, according to the Swedish Code of Corporate Governance, “[to] be independent of the company and its executive management, as well as of major shareholders in the company” (Codes 4.4 and 4.5). However, the boards of Swedish firms are almost entirely composed of non-executive directors – the Code clearly stipulates that only one executive (often the CEO) may be elected on the board. Thus, this variable mostly refers to the proportion of outside directors who are independent with respect to the largest shareholders. Furthermore, even though the CEO can sit on the board, they cannot serve as chairperson. Therefore, CEO duality does not occur at Swedish-listed companies.

13 To check the relevance condition, we estimate the Pearson correlation coefficients between these instruments and both D_ER and ERR, which are positive and significant. To investigate the reliability or exogeneity condition, we regress each instrument against D_ER (or ERR) and other control variables to estimate the residual. If the residual is correlated with the dependent variable in the main models (here, disclosure variables), the instruments are not reliable. However, we establish a correlation and thus use these instruments in the Heckman model.

14 We use all firm-specific and governance variables and year and industry dummies in a probit model to predict the likelihood of having employee representatives on the board and then obtain the propensity score. Following the propensity score design, we need to specify certain conditions: we first define a restricted caliper (i.e., 0.001) to minimize the difference between the matched subjects and control subjects as much as possible; second, we request matching without replacement (i.e., one-to-one).

15 Including firm fixed effects in the difference-in-differences model can also address the endogeneity issue by removing any time-invariant unobservable factors. However, given that D_ER shows little variation over time, fixed effects are problematic. Instead, we use a matched sample (based on the propensity score) to control for observable firm differences. We add the inverse Mills ratio to the regression to control for unobservable factors (Lennox et al., Citation2012).

16 In an additional analysis, we collect additional data for the year 2013 to examine the effect of the passage of the NFR Directive in 2014 compared to the implementation of the Directive in 2017.

17 When we only look at the proportion of employee representatives on the board in firms with employee representatives, the mean and median become 22% which still is a minority representation on the boards by employee representatives.

18 The dictionary scores from DICTION are standardized and are based on word frequencies (corrected for homographs and built-in norms based on 50,000 previously processed passages). Therefore, these scores are interpreted only in relative terms, i.e., higher scores indicate more numerical terms and more concrete text.

19 We report the results on tone variables in a separate table () due to the lack of space.

20 In Model 2 and 3, the number of observations is reduced to 1,209. This is because of multicollinearity problems that arise when carrying out the probit-model with several industry dummies in the Heckman procedure. That is industries that perfectly predict the outcome are dropped.

21 As propensity score matching depends to a large extent on specifying a “correct” caliper and the choice of including a replacement or not, we change these parameters to check the robustness of our results (see Clatworthy et al., Citation2009). First, we use a more restricted caliper (0.0001), and we find that the coefficient of the interaction (Post x D_ER) becomes significant (at the 10% level) with respect to EM_Words, while using the same caliper (0.001) and removing the option of “no replacement” provide results consistent with our main analysis.

References

- Abbott, L. J., Parker, S., & Presley, T. J. (2012). Female board presence and the likelihood of financial restatement. Accounting Horizons, 26(4), 607–629. https://doi.org/10.2308/acch-50249

- Adams, R. B., & Ferreira, D. (2012). Regulatory pressure and bank directors’ incentives to attend board meetings. International Review of Finance, 12(2), 227–248. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2443.2012.01149.x

- Adams, R. B., Hermalin, B. E., & Weisbach, M. S. (2010). The role of boards of directors in corporate governance: A conceptual framework and survey. Journal of Economic Literature, 48(1), 58–107. https://doi.org/10.1257/jel.48.1.58

- Agostini, M., Costa, E., & Korca, B. (2022). Non-financial disclosure and corporate financial performance under directive 2014/95/EU: Evidence from Italian listed companies. Accounting in Europe, 19(1), 78–109. https://doi.org/10.1080/17449480.2021.1979610

- Amel-Zadeh, A., & Serafeim, G. (2018). Why and how investors use ESG information: Evidence from a global survey. Financial Analysts Journal, 74(3), 87–103. https://doi.org/10.2469/faj.v74.n3.2

- Armstrong, C. S., Guay, W. R., & Weber, J. P. (2010). The role of information and financial reporting in corporate governance and debt contracting. Journal of Accounting and Economics, 50(2–3), 179–234. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacceco.2010.10.001

- Arora, S., & Gangopadhyay, S. (1995). Toward a theoretical model of voluntary overcompliance. Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization, 28(3), 289–309. https://doi.org/10.1016/0167-2681(95)00037-2

- Arslan-Ayaydin, Ö, Thewissen, J., & Torsin, W. (2021). Disclosure tone management and labor unions. Journal of Business Finance & Accounting, 48(1–2), 102–147. https://doi.org/10.1111/jbfa.12483

- Arvidsson, S., & Dumay, J. (2022). Corporate ESG reporting quantity, quality, and performance: Where to now for environmental policy and practice? Business Strategy and the Environment, 31(3), 1091–1110. https://doi.org/10.1002/bse.2937

- Barker, R., & Eccles, R. G. (2018). Should FASB and IASB be responsible for setting standards for non-financial information? SSRN Electronic Journal. University of Oxford. Available at SSRN 3272250. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3272250

- Bebbington, J., Unerman, J., & O’Dwyer, B. (2014). Introduction to sustainability accounting and accountability. In J. Bebbington, J. Unerman, & B. O’Dwyer (Eds.), Sustainability accounting and accountability (pp. 3–14). Routledge.

- Becher, D. A., & Frye, M. B. (2011). Does regulation substitute or complement governance? Journal of Banking & Finance, 35(3), 736–751. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbankfin.2010.09.003

- Bénabou, R., & Tirole, J. (2006). Incentives and prosocial behavior. American Economic Review, 96(5), 1652–1678. https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.96.5.1652

- Berglund, T., & Holmén, M. (2016). Employees on corporate boards. Multinational Finance Journal, 20(3), 237–271. https://doi.org/10.17578/20-3-2

- Blandhol, C., Mogstad, M., Nilsson, P., & Vestad, O. L. (2020). Do employees benefit from worker representation on corporate boards? National Bureau of Economic Research, No, w., 28269.

- Boiral, O. (2013). Sustainability reports as simulacra? A counter-account of A and A+ GRI reports. Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, 26(7), 1036–1071. https://doi.org/10.1108/AAAJ-04-2012-00998

- Brammer, S., & Pavelin, S. (2006). Voluntary environmental disclosures by large UK companies. Journal of Business Finance and Accounting, 33(7–8), 1168–1188. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-5957.2006.00598.x

- Calmfors, L., Ek, S., Kolm, A. S., Pekkarinen, T., & Skedinger, P. (2018). Arbetsmarknadsekonomisk rapport: Hur fungerar kollektivavtalen?, Arbetsmarknadsekonomiska rådet.

- Carungu, J., Di Pietra, R., & Molinari, M. (2021). Mandatory vs voluntary exercise on non-financial reporting: Does a normative/coercive isomorphism facilitate an increase in quality? Meditari Accountancy Research, 29(3), 449–476. https://doi.org/10.1108/MEDAR-08-2019-0540

- Cass, O. (2022). Why the US right wants to put workers in the boardroom (Opinion). Financial Times. https://www.ft.com/content/050e37b9-f5f9-4b4d-8b5d-a70e96981f28.

- Cho, C. H., Laine, M., Roberts, R. W., & Rodrigue, M. (2015). Organized hypocrisy, organizational façades, and sustainability reporting. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 40, 78–94. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aos.2014.12.003

- Cho, C. H., Michelon, G., & Patten, D. M. (2012). Impression management in sustainability reports: An empirical investigation of the use of graphs. Accounting and the Public Interest, 12(1), 16–37. https://doi.org/10.2308/apin-10249

- Cho, C. H., Roberts, R. W., & Patten, D. M. (2010). The language of US corporate environmental disclosure. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 35(4), 431–443. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aos.2009.10.002

- Christensen, D. M., Serafeim, G., & Sikochi, A. (2022). Why is corporate virtue in the Eye of The beholder? The case of ESG ratings. The Accounting Review, 97(1), 147–175. https://doi.org/10.2308/TAR-2019-0506

- Christensen, H. B., Hail, L., & Leuz, C. (2021). Mandatory CSR and sustainability reporting: Economic analysis and literature review. Review of Accounting Studies, 26(3), 1176–1248. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11142-021-09609-5

- Clatworthy, M. A., Makepeace, G. H., & Peel, M. J. (2009). Selection bias and the Big four premium: New evidence using Heckman and matching models. Accounting and Business Research, 39(2), 139–166. https://doi.org/10.1080/00014788.2009.9663354

- Conchon, A., Klugen, N., & Stollt, M. (2015). Table: Worker board-level participation in the 31 European economic area countries. European Trade Union Institute.

- Costa, E., & Agostini, M. (2016). Mandatory disclosure about environmental and employee matters in the reports of Italian-listed corporate groups. Social and Environmental Accountability Journal, 36(1), 10–33. https://doi.org/10.1080/0969160X.2016.1144519

- Cuomo, F., Gaia, S., Girardone, C., & Piserà, S. (2022). The effects of the EU non-financial reporting directive on corporate social responsibility. European Journal of Finance, 1–27. doi:10.1080/1351847X.2022.2113812

- Day, R., & Woodward, T. (2004). Disclosure of information about employees in the directors’ report of UK published financial statements: Substantive or symbolic? Accounting Forum, 28(1), 43–59. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.accfor.2004.04.003

- Dhaliwal, D., Li, O. Z., Tsang, A., & Yang, Y. G. (2014). Corporate social responsibility disclosure and the cost of equity capital: The roles of stakeholder orientation and financial transparency. Journal of Accounting and Public Policy, 33(4), 328–355. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaccpubpol.2014.04.006

- Dienes, D., & Velte, P. (2016). The impact of supervisory board composition on CSR reporting. Evidence from the German two-tier system. Sustainability, 8, 63. https://doi.org/10.3390/su8010063

- Dixon-Fowler, H. R., Ellstrand, A. E., & Johnson, J. L. (2017). The role of board environmental committees in corporate environmental performance. Journal of Business Ethics, 140(3), 423–438. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-015-2664-7

- Edmans, A. (2011). Does the stock market fully value intangibles? Employee satisfaction and equity prices. Journal of Financial Economics, 101(3), 621–640. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfineco.2011.03.021

- EFRAG. (2021). EFRAG welcomes its role in the European Commission’s proposal for a new CSRD. https://www.efrag.org/News/Project-489/EFRAG-welcomes-its-role-in-the-European-Commissions-proposal-for-a-new-CSRD

- European Commission. (2014). Directive 2014/95/EU of the European Parliament and of the Council of 22 October 2014 amending Directive 2013/34/EU as regards disclosure of non-financial and diversity information by certain large undertakings and groups.

- European Commission. (2017). Guidelines on non-financial reporting (methodology for reporting non-financial information) (2017/C 215/01).

- Fauver, L., & Fuerst, M. E. (2006). Does good corporate governance include employee representation? Evidence from German corporate boards. Journal of Financial Economics, 82(3), 673–710. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfineco.2005.10.005

- Fiechter, P., Hitz, J.-M., & Lehmann, N. (2022). Real effects of a widespread CSR reporting mandate: Evidence from the European Union’s CSR directive. Journal of Accounting Research, 60(4), 1499–1549. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-679X.12424

- Financial Reporting Council, F. R. C. (2018). The UK corporate governance code. Available at: UK Corporate Governance Code. Financial Reporting Council. https://www.frc.org.uk/directors/corporate-governance-and-stewardship/uk-corporate-governance-codefrc.org.ukhttps://www.frc.org.uk/directors/corporate-governance-and-stewardship/uk-corporate-governance-code.

- Forth, J., Bryson, A., & George, A. (2017). Explaining cross-national variation in workplace employee representation. European Journal of Industrial Relations, 23(4), 415–433. https://doi.org/10.1177/0959680117697861

- Fulton, L. (2019). Board-level employee representation in the UK: Is it really coming? Recent developments and debates, Mitbestimmungsreport No. 55e [Hans-Böckler-Stiftung, Institut für Mitbestimmung und Unternehmensführung (I.M.U.), Düsseldorf].

- García Osma, B., & Guillamón-Saorín, E. (2011). Corporate governance and impression management in annual results press releases. Accounting, Organizations and Society, 36(4–5), 187–208. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.aos.2011.03.005

- Gillan, S. L., Koch, A., & Starks, L. T. (2021). Firms and social responsibility: A review of ESG and CSR research in corporate finance. Journal of Corporate Finance, 66, 101889. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcorpfin.2021.101889

- Gleason, C. A., Kieback, S., Thomsen, M., & Watrin, C. (2021). Monitoring or payroll maximization? What happens when workers enter the boardroom? Review of Accounting Studies, 26(3), 1046–1087. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11142-021-09606-8

- Gregorič, A., & Rapp, M. S. (2019). Board-level employee representation (BLER) and firms’ responses to crisis. Industrial Relations: A Journal of Economy and Society, 58(3), 376–422. https://doi.org/10.1111/irel.12241

- Grewal, J., Riedl, E. J., & Serafeim, G. (2019). Market reaction to mandatory non-financial disclosure. Management Science, 65(7), 3061–3084. https://doi.org/10.1287/mnsc.2018.3099

- Hassan, A. (2022). Social and environmental accounting research in vulnerable and exploitable less-developed countries: A theoretical extension. Accounting Forum, 1–25. https://doi.org/10.1080/01559982.2022.2051685

- Heckman, J. J. (1979). Sample selection bias as a specification error. Econometrica, 47(1), 153–161. https://doi.org/10.2307/1912352

- Herremans, I. M., Nazari, J. A., & Mahmoudian, F. (2016). Stakeholder relationships, engagement, and sustainability reporting. Journal of Business Ethics, 138(3), 417–435. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-015-2634-0

- Hillman, A. J., Cannella, A. A., & Paetzold, R. L. (2000). The resource dependence role of corporate directors: Strategic adaptation of board composition in response to environmental change. Journal of Management Studies, 37(2), 235–256. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-6486.00179

- Hillman, A. J., & Dalziel, T. (2003). Boards of directors and firm performance: Integrating agency and resource dependence perspectives. The Academy of Management Review, 28(3), 383–396. https://doi.org/10.2307/30040728

- Hoffmann, E., Dietsche, C., & Hobelsberger, C. (2018). Between mandatory and voluntary: Non-financial reporting by German companies, 26, 1–4. (pp. 47–63). Nachhaltigkeits Management Forum/Sustainability Management Forum.

- Hong, B., Li, Z., & Minor, D. (2016). Corporate governance and executive compensation for corporate social responsibility. Journal of Business Ethics, 136(1), 199–213. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-015-2962-0

- Jackson, S., Joshi, A., & Erhardt, N. L. (2003). Recent research on team and organizational diversity: SWOT analysis and implications. Journal of Management, 29(6), 801–830. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0149-2063(03)00080-1

- Jäger, S., Noy, S., & Schoefer, B. (2022). What does codetermination do? ILR Review, 75(4), 857–890. https://doi.org/10.1177/00197939211065727

- Jäger, S., Schoefer, B., & Heining, J. (2021). Labor in the boardroom. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 136(2), 669–725. https://doi.org/10.1093/qje/qjaa038

- Johansen, T. R. (2016). EU regulation of corporate social and environmental reporting. Social and Environmental Accountability Journal, 36(1), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1080/0969160X.2016.1148948

- Joskow, P., Rose, N., Shepard, A., Meyer, J. R., & Peltzman, S. (1993). Regulatory constraints on CEO compensation. Brookings Papers on Economic Activity. Microeconomics, 1993(1), 1–72. https://doi.org/10.2307/2534710

- Kelley, B. (2018). Many countries require workers on the board. Wall Street journal (Opinion). https://www.wsj.com/articles/many-countries-require-workers-on-boards-1537305449.

- Kent, P., McCormack, R., & Zunker, T. (2021). Employee disclosures in the grocery industry before the COVID-19 pandemic. Accounting & Finance, 61(3), 4833–4858. https://doi.org/10.1111/acfi.12755

- Kent, P., & Zunker, T. (2017). A stakeholder analysis of employee disclosures in annual reports. Accounting & Finance, 57(2), 533–563. https://doi.org/10.1111/acfi.12153

- Khan, H. Z., Bose, S., Mollik, A. T., & Harun, H. (2020). “Green washing” or “authentic effort”? An empirical investigation of the quality of sustainability reporting by banks. Accounting, Auditing & Accountability Journal, 34(2), 338–369. https://doi.org/10.1108/AAAJ-01-2018-3330

- Kjellberg, A. (2022). Kollektivavtalens täckningsgrad samt organisationsgraden hos arbetsgivarförbund och fackförbund. Lunds Universitet.

- La Torre, M., Sabelfeld, S., Blomkvist, M., & Dumay, J. (2020). Rebuilding trust: Sustainability and non-financial reporting and the European Union regulation. Meditari Accountancy Research, 28(5), 701–725. https://doi.org/10.1108/MEDAR-06-2020-0914

- La Torre, M., Sabelfeld, S., Blomkvist, M., Tarquinio, L., & Dumay, J. (2018). Harmonising non-financial reporting regulation in Europe. Meditari Accountancy Research, 26(4), 598–621. https://doi.org/10.1108/MEDAR-02-2018-0290

- Lee, J., & Park, J. (2019). The impact of audit committee financial expertise on management discussion and analysis (MD&A) tone. European Accounting Review, 28(1), 129–150. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638180.2018.1447387

- Lennox, C. S., Francis, J. R., & Wang, Z. (2012). Selection models in accounting research. The Accounting Review, 87(2), 589–616. https://doi.org/10.2308/accr-10195

- Leuz, C., & Wysocki, P. D. (2016). The economics of disclosure and financial reporting regulation: Evidence and suggestions for future research. Journal of Accounting Research, 54(2), 525–622. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-679X.12115

- Levinson, K. (2001). Employee representatives on company boards in Sweden. Industrial Relations Journal, 32(3), 264–274. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2338.00197

- Li, Q., Lourie, B., Nekrasov, A., & Shevlin, T. (2022). Employee turnover and firm performance: Large-sample archival evidence. Management Science, 68(8), 5667–5683. https://doi.org/10.1287/mnsc.2021.4199

- Lin, C., Schmid, T., & Xuan, Y. (2018). Employee representation and financial leverage. Journal of Financial Economics, 127(2), 303–324. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jfineco.2017.12.003

- Lopatta, K., Böttcher, K., Lodhia, S. K., & Tideman, S. A. (2020). The relationship between gender diversity and employee representation at the board level and non-financial performance: A cross-country study. The International Journal of Accounting, 55(1), 2050001.

- Loughran, T., & McDonald, B. (2011). When is a liability not a liability? Textual analysis, dictionaries, and 10-Ks. Journal of Finance, 66(1), 35–65. doi:10.1111/j.1540-6261.2010.01625.x

- Loughran, T., & McDonald, B. (2016). Textual analysis in accounting and finance: A survey. Journal of Accounting Research, 54(4), 1187–1230. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-679X.12123

- Melloni, G., Caglio, A., & Perego, P. (2017). Saying more with less? Disclosure conciseness, completeness and balance in integrated reports. Journal of Accounting and Public Policy, 36(3), 220–238. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaccpubpol.2017.03.001

- O’Grady, F., & Bowman, S. (2017). Should companies be forced to put workers on the board. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2017/aug/29/companies-workers-boards-theresa-may-u-turn.