ABSTRACT

It is nearly a century since the Buff-breasted Button-quail Turnix olivii was last definitively recorded, resulting in the species being recently classified as one of Australia’s most imperilled species. However, conservation action to recover the species has been hampered by an inability to locate an extant population. To overcome this problem we conducted extensive surveys across the species’ presumed distribution. We surveyed historical sites where the species was collected, and also where habitat deemed suitable for the species occurred on Cape York Peninsula. We also surveyed sites on the northern Atherton Tablelands where a contemporary population has been reported. Surveys were conducted from 2018 to 2022 and employed a variety of survey methods known to be suitable for detecting button-quail. No evidence of Buff-breasted Button-quail was detected. However, Painted Button-quail Turnix varius where found to be widespread at sites surveyed in the Wet Tropics and Einasleigh Uplands bioregions as well as in southern areas of Cape York Peninsula. We discuss the implications of these results including the likely effectiveness of the different survey methods for detecting the Buff-breasted Button-quail specifically, and button-quail generally.

Introduction

The ability to detect a threatened species is fundamental to conserving it (Whittaker et al. Citation2005). If a species cannot be detected it is very difficult to assess its geographical distribution and population trajectory (Lees et al. Citation2021; Brook et al. Citation2023). If the species is also poorly known, any efforts to better understand that species’ autecology or the threatening processes it faces will be thwarted (Watson et al. Citation2022). For these reasons, when detectability is a problem, it should become a critical focus for conservation research (Lees et al. Citation2021). It also follows that not detecting a species despite a significant search effort should raise significant concerns around that species’ conservation status (Bland et al. Citation2015).

A threatened species emblematic of this conundrum is the Buff-breasted Button-quail Turnix olivii, a small (≈120 g) ground-dwelling bird endemic to the tropical savannas of northeastern Queensland, and recently uplisted to Critically Endangered under state legislation (Queensland Government Citation2022). The type specimen and the only first-hand field reports supported by verifiable evidence come from the Cape York Peninsula bioregion (Webster, Leseberg, Murphy, Joseph et al. Citation2022). Following the last specimen collected in 1924 (Webster, Leseberg, Murphy, Joseph et al. Citation2022), the species then went largely unreported until a population was discovered in the 1970s much further south, near Mareeba in the Wet Tropics and Einasleigh Uplands bioregions (hereafter WT/EU) (Squire Citation1990). Importantly, over the next few decades there were multiple sightings from this region (Rogers Citation1995; Nielsen Citation2000, Citation2015; Mathieson and Smith Citation2009, Citation2017; Smith and Mathieson Citation2019).

As all recent published reports of the Buff-breasted Button-quail have come from the WT/EU, the species’ conservation status has been based largely on our understanding of this WT/EU population. However, accounts of the species from the WT/EU are all anecdotal, with no sightings supported by tangible evidence such as a photo or skin. Most reports describe an extremely shy and cryptic species that is very difficult to detect, never heard calling, almost never seen until flushed and, once flushed, rarely seen again (Rogers Citation1995; Nielsen Citation2015). These reports contrast markedly with the experiences of McLennan (Citation1922), who reported that, like most other button-quail, the Buff-breasted Button-quail is relatively easy to detect by call, and could be readily observed by imitating the call to coax it towards the observer. It also now appears that many ‘detections’ were actually of the similar but much more common Painted Button-quail Turnix varius (Webster, Leseberg, Murphy, and Watson Citation2023).

The inability to reliably detect any Buff-breasted Button-quail populations has resulted in the species becoming one of Australia’s least known and potentially most imperilled species (Garnett et al. Citation2022; Backstrom et al. Citation2023). This has also affected the conservation attention it has received, with the species not captured in the Threatened Species Strategy Action Plan 2021–2026 (DAWE Citation2022) and therefore receiving no federal funding or attention. In 2018, we aimed to alleviate that uncertainty through a four-year program of intensive surveys for the Buff-breasted Button-quail, covering both the Cape York Peninsula and WT/EU bioregions. We used multiple survey methods known to be effective for finding button-quail and present the results of those surveys here. We discuss the implications of these results in light of our current understanding of the status of the Buff-breasted Button-quail.

Materials and methods

Survey sites

Thirty-two broad survey sites were selected based on meeting one or more of three criteria; (1) confirmed sites where Buff-breasted Button-quail had been historically collected (McLennan Citation1922; Webster, Jackett et al. Citation2022); (2) sites where Buff-breasted Button-quail had been reported but not confirmed (see e.g. Mathieson and Smith Citation2009; Nielsen Citation2015); and, (3) sites of intact savanna which conformed to the description of suitable habitat as provided by McLennan (Citation1922) (). Sites where McLennan collected Buff-breasted Button-quail were described in his field diary using local landmarks. We consulted McLennan’s diary and, with the help of local experts, were able to pinpoint the exact collection locations, at which we conducted surveys. Sites where Buff-breasted Button-quail had been reported but not confirmed were extracted from published literature and reports and consultation with the local bird watching community.

Table 1. Locations where surveys for Buff-breasted Button-quail occurred. The years surveys occurred and methods utilised are given for each area. The latitude and longitude refer to the approximate centroid of the site.

Surveys occurred between October 2018 and August 2022 across the Cape York Peninsula and the WT/EU bioregions of north Queensland. Although surveys focused on locating a population of Buff-breasted Button-quail, all species of button-quail and similar ground dwelling species (e.g. Brown Coturnix ypsilophora and King Quail Synoicus chinensis) were recorded.

Survey methodology

Flush surveys

Traditionally researchers attempting to survey button-quail have resorted to walking ‘flush’ surveys (Chaplin Citation2011; Lee et al. Citation2018), where an observer walks through an area of suitable habitat intending to disturb a button-quail, thereby causing it to take flight. Survey sites were traversed on foot at a slow walking pace by a single observer (PW) for ‘solo flush surveys’ or by a group of two to six individuals for ‘group flush surveys’. For group flush surveys, observers would walk side by side at a distance of approximately five metres. When a button-quail was seen on the ground or flushed, details pertaining to the overall size, shape and plumage patterns were noted. If a button-quail was flushed and insufficient detail was observed to identify the species, an attempt was made to relocate and flush the bird. The distance and duration of each walking survey were recorded. Solo flush surveys covered 736 km, across 217 surveys. Group flush surveys covered 300 km, across 114 surveys (see ).

Acoustic surveys

The advent of technologies such as camera traps and autonomous recording units (ARUs) has provided effective techniques to survey otherwise cryptic wildlife populations (Lambert and McDonald Citation2014; Bessone et al. Citation2020). The ability to deploy these machines for lengthy periods greatly increases the potential to detect rare and/or cryptic species (Leseberg et al. Citation2022). However, a limitation of ARUs is the need for a thorough understanding of the target species’ vocalisations. Except for the Buff-breasted Button-quail, the vocalisations of button-quail present in Australia’s tropical savannas have been described recently in detail (Webster et al. Citation2021, Webster et al. Citation2023). These studies have suggested button-quail present in Australia’s tropical savannas are highly vocal during periods of breeding, which occurs during the wet season. This concurs with the research of McLennan (Citation1922) who noted that Buff-breasted Button-quail are vocal during the wet season when breeding and, although there is no known recording of the species’ vocalisation, he provided a written description of the call which would be sufficient to enable identification.

ARU surveys were conducted during northern Australia’s wet season (December to April) across 125 sites, amounting to 9,940 survey days (see ). ARUs used were Song Meter 2, 3, 4 and Mini (Wildlife Acoustics, Massachusetts, USA). ARUs recorded in mono at 8000 Hz, which satisfies the need for the sample rate to be more than twice the highest known frequency of the target call (Landau Citation1967). Initially units were set to record from 1 hour before sunrise for 4 hours and then from 3 hours before sunset for 4 hours. This was later modified to record from sunrise for 3 hours and from 3 hours before sunset to sunset to reduce the quantity of data collected, as most vocalisations in the early sampling protocol were detected during daylight hours. Audio data was processed using the audio analysis software Kaleidoscope (Wildlife Acoustics, Massachusetts, USA).

Potential button-quail calls were extracted by applying the following parameters: the minimum and maximum frequency range was 175–450 Hz; the minimum and maximum length of detection was 5–45 s; the maximum inter-syllable gab was 1.5 s; and the window size was FFT 21.33 ms. These parameters were selected to encompass the diversity of known button-quail vocalisations. Although there are no recordings of the Buff-breasted Button-quail, based on first-hand descriptions by McLennan (Citation1922), the species’ call is expected to fall within these parameters, and would therefore be extracted from the acoustic data if present (noting that we detected other non-button-quail, low frequency sounds). A spectrogram of each potential call extracted by Kaleidoscope was first scanned to determine if it was a likely button-quail call; button-quail calls have distinctive visual signatures (Webster et al. Citation2021, Webster et al. Citation2023). Likely calls were further analysed in Audacity (version 2.2.2; Audacity Team 2018) by listening to the complete call using Dynamic Stereo Headphones (MDR-7506, Sony, Tokyo, Japan), and assigned to a species.

Camera trapping

Camera trapping offers similar benefits to ARUs; rare and/or cryptic species or events can be detected by passive infrared motion-triggered sensors and a photograph taken. This can prove extremely important where such detail is required to enable identification. Camera traps are now commonly used to survey ground-dwelling mammals (Diete et al. Citation2015) and birds (Znidersic Citation2017) and, to a lesser extent reptiles, invertebrates and amphibians (Hobbs et al. Citation2017). Camera trapping has been used effectively to survey for Black-breasted Button-quail Turnix melanogaster (Webster, Shimomura et al. Citation2022) and Painted Button-quail Turnix varius scintillans (Carter et al. Citation2022).

In addition to camera trap data collected as part of this research, further camera trap data were sourced from camera trap deployments by the Australian Wildlife Conservancy (AWC), and other researchers in this region (Christopher Pocknee, pers. comm.). A total of 1091 sites were covered across the three datasets, see , amounting to 40,154 trap days. Camera traps used were Reconyx Hyperfire HC500, Hyperfire HC600 and Hyperfire HF2X (Reconyx, Wisconsin, USA). When setting cameras, they were positioned on steel pickets or attached to trees at a height of approximately 50 cm, in apparently suitable habitat. Surveys conducted by AWC and other researchers were typically targeting various mammal species and, therefore, the following baits/lures were used; chicken, peanut butter and oat or synthetic cat pheromone.

Call playback surveys

Performing call playback, when a series of the target species’ vocalisations are broadcast into a survey area, is another common survey method used when searching for cryptic species. It is effective across a diversity of taxa including birds, terrestrial and marine mammals, and amphibians (Vrezec and Bertoncelj Citation2018; Fouquet et al. Citation2021; Bilney et al. Citation2022; Ethier et al. Citation2022; King and Jensen Citation2022). All female button-quail give an advertising oom call, and response to playback of the advertising oom has been documented in Painted and Chestnut-backed Button-quail Turnix castanotus (Webster and Stoetzel Citation2021; Webster, Leseberg, Murphy, and Watson Citation2022). Similarly, McLennan (Citation1922) would imitate what, according to its description, is likely to be the Buff-breasted Button-quail’s advertising oom to bring a bird closer so it could be shot for collection. This method is therefore likely to be an effective means of surveying for Buff-breasted Button-quail. However, it is heavily reliant on knowledge of the target species’ vocalisations and, currently, there is no known recording of the Buff-breasted Button-quail’s advertising oom.

Call playback surveys were conducted in areas where Buff-breasted Button-quail had been reported or in areas deemed suitable habitat for the species based on McLennan’s descriptions and also the purported habitat definition from WT/EU (Mathieson and Smith Citation2009), see (). A Bluetooth speaker (JBL GO2, Harman International Industries, California, USA) was used to broadcast button-quail vocalisations. The observer would sit 10–20 metres from the speaker concealed in vegetation or covered in camouflage netting. The advertising oom vocalisations of Painted Button-quail and Chestnut-backed Button-quail (Webster et al. Citation2021, Webster et al. Citation2023) were used, along with a call initially thought to be a Buff-breasted Button-quail (Smith and Mathieson Citation2019) but which was later shown to be a Painted Button-quail (Webster, Leseberg, Murphy, and Watson Citation2023). The vocalisations, which last 30–40 seconds, were played on a loop with a 15 second break between vocalisations for a period of 15 minutes. Playback was stopped when a response was detected. If an additional bird was seen or heard responding, playback continued until the observer was confident all responding birds had been recorded. Call playback surveys were performed at 593 sites using Painted Button-quail (n = 197), Chestnut-backed Button-quail (n = 112) and the purported Buff-breasted Button-quail vocalisation (n = 396) ().

Table 2. Results of button-quail survey across northern Queensland. Number of detections for each button-quail (BQ) species for each survey method. For ARU surveys this represents total detections (in parentheses is the number of survey sites/ARUs which had a detection of that species).

Results

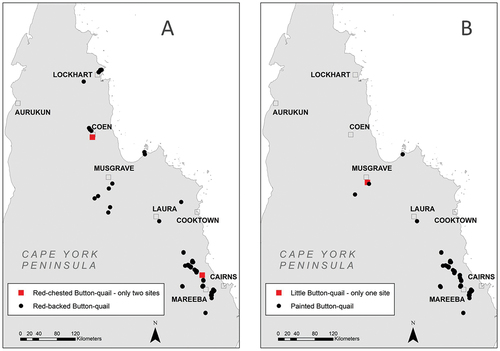

No evidence of Buff-breasted Button-quail was detected at any site throughout this survey. Four other button-quail species were detected (). Red-backed Button-quail Turnix maculosus were the most frequently detected species (n = 1463), followed by Painted Button-quail (n = 1119). Red-chested Turnix pyrrhothorax (n = 4) and Little Button-quail Turnix velox (n = 1) were detected but in much lower numbers. Brown and King Quail were also detected. Painted Button-quail were located at four locations in the Cape York Peninsula bioregion, representing significant range extensions (Webster, Leseberg, Murphy, and Watson Citation2022). Painted Button-quail were also found to be common in the WT/EU where contemporary reports of Buff-breasted Button-quail had been made.

Figure 2. Map of northern Queensland, Australia showing the locations where Painted and Little Button-quail were recorded (A) and Red-backed and Red-chested Button-quail were recorded (B). Note Little Button-quail were recorded at only one site and Red-chested Button-quail were recorded at only two sites.

Each survey method was successful in detecting button-quail, and a total of 2587 individual detections were obtained. ARU surveys produced the most detections, amounting to 89% of all detections (844 Painted Button-quail and 1452 Red-backed Button-quail detections). Painted and Red-backed Button-quail were detected on 17.6% and 25.6% of ARU surveys, respectively.

Only Painted Button-quail were detected during call playback surveys. These detections were all in response to the broadcast of conspecific vocalisations. No response was detected to the Chestnut-backed Button-quail vocalisation. Call playback surveys represented 6.3% of detections and achieved the fastest return on survey effort.

Camera trap surveys had the largest sampling effort of all methods but generated the lowest number of button-quail detections. Over 40,154 trap days, only 73 button-quail were detected and these were either Painted or Red-backed Button-quail. This is an average of one button-quail detection per 550 trap days.

Flush surveys produced only marginally more detections. Over 168 days of flush surveys totalling 1033 km, 75 button-quail were detected, which comprised only Painted, Red-backed, Red-chested and Little Button-quail. During solo ‘flush’ surveys 35 button-quail were detected and 41 were detected in group ‘flush’ surveys. This represents a single button-quail detection per 13.8 km of survey effort.

Discussion

The survey effort presented here spanned four years and used various survey techniques that have been demonstrated as effective for detecting other species of button-quail. We failed to detect Buff-breasted Button-quail throughout both the theorised contemporary distribution in the WT/EU and the known historical distribution on Cape York Peninsula. The inability to detect the presence of a single Buff-breasted Button-quail over a four year period is very concerning given this is the largest documented search effort for this species.

Potential reasons for non-detection in areas where it was recently detected

One possible reason we did not detect Buff-breasted Button-quail in the WT/EU was the preferred weather conditions, as theorised by Squire (Citation1990) and Nielsen (Citation2015), did not occur during the survey period. Both Squire (Citation1990) and Nielsen (Citation2015) argued Buff-breasted Button-quail are nomadic or partially migratory. Squire (Citation1990) suggested that Buff-breasted Button-quail are encountered in the WT/EU in years of above average rainfall. In contrast, Nielsen (Citation2015) proposed that they arrive to breed in the WT/EU when rainfall is low and grass growth is below average. We note that limited data were presented by either Squire (Citation1990) or Nielsen (Citation2015) to support these claims, which limits our ability to investigate them properly. Nonetheless, both claims contrast with the observations of McLennan (Citation1922) who recorded Buff-breasted Button-quail breeding in areas of dense tall grass during what was apparently a typical monsoonal wet season. The claims of Squire (Citation1990) and Nielsen (Citation2015) also contrast with the sedentary nature of the other two species of large savanna dwelling button-quail, Chestnut-backed and Painted Button-quail (Marchant and Higgins Citation1993; Debus Citation1996). Both of those species are sedentary in tropical savannas throughout the wet and dry seasons of Australia’s monsoon tropics and breed during the wet season (Webster, Jackett et al. Citation2022).

The different theories, however, do not explain why we did not detect Buff-breasted Button-quail. Using 836.1 mm as the annual average rainfall for typical WT/EU Buff-breasted Button-quail locations (based on Mareeba Airport (Australian Government Bureau of Meteorology Citation2023) which is near most of the records), the first two years of our surveys (2019 and 2020) had below average rainfall (666.4 mm and 567.4 mm respectively). According to Nielsen (Citation2015) this period should have provided the conditions conducive to Buff-breasted Button-quail occupancy in the WT/EU. In the latter two years, 2021 and 2022, the annual rainfall was above average (1031 mm and 971.4 mm respectively), and this should have provided the conditions conducive for detection, as described by Squire (Citation1990). In light of this evidence, it is unlikely unsuitable weather conditions explains our result of not detecting Buff-breasted Button-quail in the WT/EU.

Another potential reason for not detecting any Buff-breasted Button-quail is that the population had declined to an undetectably low level immediately prior to our survey. In the period 2010–2018 multiple reports were made at three distinct sites across the WT/EU, the most recent being a series of sightings made near Mount Mulligan in 2016 (Mathieson and Smith Citation2017) and a large number of reported sightings near Mount Carbine from 2016 to 2018 (Australian Wildlife Conservancy Citation2016, Citation2018). In the four years prior to our survey (2015–2018) there were 29 published sightings of Buff-breasted Button-quail across the WT/EU, the greatest number of reports ever reported in the WT/EU. Since 2019, however, there have been no published reports of Buff-breasted Button-quail from the WT/EU, or elsewhere. This coincided with the start of our systematic research on the species. No apparent threatening processes emerged or increased that would explain the abrupt disappearance of Buff-breasted Button-quail during this timeframe or the preceding decades. It seems anomalous that the species both stopped being reported by others at the onset of this survey, and was not detected during the survey period, despite frequent reports in the years immediately prior.

Another explanation for our inability to locate Buff-breasted Button-quail within the WT/EU is that the species does not occur, and perhaps never has occurred, in this region. There are three lines of evidence supporting this explanation. First, the methods we used are known to be effective at detecting other species of button-quail (Lee et al. Citation2018; Carter et al. Citation2022). We detected four other button-quail species during these surveys, including significant range extensions of the Painted Button-quail (Webster, Leseberg, Murphy, and Watson Citation2022), suggesting our methods were effective at detecting button-quail where they occur. Second, a recent review found that there has never been any tangible evidence provided to support any sightings of the Buff-breasted Button-quail in the WT/EU (McKelvey et al. Citation2008). The only evidence of the species’ occurrence in the region is anecdotal, and should therefore be treated with caution (McKelvey et al. Citation2008). Third, there is emerging evidence that many of the Buff-breasted Button-quail reports from the WT/EU are misidentifications of the more common Painted Button-quail (Webster Citation2022; Webster, Leseberg, Murphy, and Watson Citation2023).

Buff-breasted Button-quail near Coen

While it is alarming that we have been unable to detect the Buff-breasted Button-quail in the WT/EU, as discussed above there are some plausible explanations for why this may have been the case. Our inability to detect the species near Coen is far more concerning. Coen is the only location where Buff-breasted Button-quail have ever been collected or recorded by a reliable observer with direct and verifiable field experience with the species (Webster, Leseberg, Murphy, Joseph et al. Citation2022). In the 1920s the species appears to have been common in the tropical savanna around Coen: multiple specimens were collected from 1921 to 1924, and the species’ autecology was described in some detail based on firsthand accounts (White Citation1922a, Citation1922b). From the mid-1920s to the present, it seems this population has declined to the point that either it is now extirpated, or exists at a level undetectable using our methods and level of effort.

Declines of other savanna dwelling avifauna that were also apparently common around Coen in the 1920s have been documented. Notably, Golden-shouldered Parrots Psephotellus chrysopterygius have disappeared (Garnett and Baker Citation2021; Crowley and Garnett Citation2023), and Brown Treecreepers Climacteris picumnus and Black-faced Woodswallows Artamus cinereus also now appear to be absent or greatly reduced in populations and/or distribution (Garnett and Crowley Citation1995). These declines are probably related to changes in land use; specifically, a shift from land management by First Nations People to the introduction of cattle grazing, changes in fire regimes, the arrival of introduced predators and other invasive species, and possibly dingo persecution (Garnett and Baker Citation2021). These pressures alter resource availability, predation pressure and lead to a complex shift in vegetation structure known as woody thickening (Crowley and Garnett Citation1998). Woody thickening itself triggers further changes in resource availability and a further intensification of predation pressure (Murphy et al. Citation2021). Whether these threatening processes have also impacted the Buff-breasted Button-quail is unknown, but seems probable.

Conclusion

We did not detect a single Buff-breasted Button-quail during this survey period, nor did we have any ambiguous sightings that could have possibly been Buff-breasted Button-quail. These results are concerning. Most recent assessments of the species’ conservation status have relied on the presence of a population in the WT/EU. We found no evidence for the occurrence of this population. Further, we found no evidence that the species still occurs in the Coen area of Cape York Peninsula, the only site where the species is conclusively known to have occurred. However, we note that there are still extensive areas of habitat in this region that have not been searched.

The Buff-breasted Button-quail requires urgent research to locate a population so that its status can be confirmed, threats can be understood and conservation actions undertaken. However, given a lack of autecological knowledge, this will be difficult. Further research needs to focus on mapping likely habitat based on McLennan’s validated descriptions from Cape York Peninsula, augmented with information from the Buff-breasted Button-quail’s sister taxa, Chestnut-backed and Painted Button-quail. Using these results, potential sites could be selected and widespread surveys undertaken, ideally with the assistance of Traditional Owners, many of whom still have detailed knowledge of country. Given the extent of potentially suitable habitat on Cape York Peninsula, we are optimistic that a targeted survey effort will lead to the discovery of a population.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the traditional custodians throughout the region in which this work was conducted. Field work was supported by Emily Rush, Henry Stoetzel, Gina and Anders Zimny, Nigel Jackett, George Swann, Andy Howe, Catherine Hayes, Mark Allen, Richard Allen, Carlos Gutiérrez-Expósito, Rigel Jensen and Sue Shephard. Access to localities to perform this research was generously provided by the Australian Wildlife Conservancy, Forever Wild, Andrew Francis, Fiachra Kearney, John Colless, Kalan Enterprises, Paddy Shephard and Tom and Sue Shephard. Field work was funded by the Australian Government’s National Environmental Science Program under project NESP 2.6, the University of Queensland Research and Recovery of Endangered Species Group, the Conservation and Wildlife Research Trust, Birds Queensland and the Graham Harrington Research Award. This research was conducted under the University of Queensland’s Animal Ethics approval SEES/025/19/NT and the Queensland Government’s scientific research permits: PTU19-001834 & WA0015339.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Australian Government Bureau of Meteorology (2023). Monthly rainfall Mareeba Airport. (Australian Governmnet Bureau of Meterology.) http://www.bom.gov.au/jsp/ncc/cdio/weatherData/av/p_nccObsCode=139&p_display_type=dataFile&p_startYear=&p_c=-194815587&p_stn_num=031210 [Verified 15 March 2022].

- Australian Wildlife Conservancy (2016). Brooklyn: A stronghold for the Buff-breasted Button-quail, one of Australia’s rarest birds. Wildlife matters Winter 2016. Subiaco East, Australian Wildlife Conservancy: 11.

- Australian Wildlife Conservancy (2018). First ever pictures of rare button-quail. Wildlife Matters Winter 2018. Subiaco East, Australian Wildlife Conservancy: 10–11.

- Backstrom, L. J., Leseberg, N. P., Callaghan, C. T., Sanderson, C., Fuller, R. A. and Watson, J. E. M. (2023). Using citizen science to identify Australia’s least known birds and inform conservation action. Emu - Austral Ornithology 1–7. doi:10.1080/01584197.2023.2283443

- Bessone, M., Kühl, H. S., Hohmann, G., Herbinger, I., N’Goran, K. P., Asanzi, P., et al. (2020). Drawn out of the shadows: Surveying secretive forest species with camera trap distance sampling. The Journal of Applied Ecology 57(5), 963–974. doi:10.1111/1365-2664.13602

- Bilney, R. J., Kambouris, P. J., Peterie, J., Dunne, C., Makeham, K., Kavanagh, R. P., et al. (2022). Long-term monitoring of an endangered population of yellow-bellied glider ‘Petaurus australis’ on the Bago Plateau, New South Wales, and its response to wildfires and timber harvesting in a changing climate. Australian Zoologist 42(2), 592–607. doi:10.7882/AZ.2022.035

- Bland, L. M., Collen, B., Orme, C. D. L., and Bielby, J. (2015). Predicting the conservation status of data‐deficient species. Conservation Biology 29(1), 250–259. doi:10.1111/cobi.12372

- Brook, B. W., Sleightholme, S. R., Campbell, C. R., Jarić, I., and Buettel, J. C. (2023). Resolving when (and where) the Thylacine went extinct. Science of the Total Environment 877, 162878. doi:10.1016/j.scitotenv.2023.162878

- Carter, R. S., Lohr, C. A., Burbidge, A. H., van Dongen, R., Chapman, J., and Davis, R. A. (2022). Eaten out of house and home: Local extinction of Abrolhos painted button-quail Turnixvarius scintillans due to invasive mice, herbivores and rainfall decline. Biological Invasions 25(4), 1119–1132.

- Chaplin, D. (2011). BANQ Buff-breasted Button-quail search: 3–4 December 2011, BirdLife Northern Queensland.

- Crowley, G. M., and Garnett, S. T. (1998). Vegetation change in the grasslands and grassy woodlands of East-central Cape York Peninsula, Australia. Pacific Conservation Biology 4(2), 132–148. doi:10.1071/PC980132

- Crowley, G., and Garnett, S. (2023). Distribution and decline of the golden-shouldered parrot Psephotellus chrysopterygius 1845–1990. North Queensland Naturalist 53, 22–68.

- DAWE (2022). Threatened Species Strategy Action Plan 2021–2026. Canberra.

- Debus, S. (1996). Family Turnicidae (Buttonquail). Handbook of the Birds of the World, Volume 3: Hoatzin to Auks (Eds.J. del Hoyo, A. Elliott, and J. Sargatal), pp. 44–59. (Lynx Edicions: Barcelona, Spain.)

- Diete, R. L., Meek, P. D., Dixon, K. M., Dickman, C. R., and Leung, L. K. P. (2015). Best bait for your buck: Bait preference for camera trapping north Australian mammals. Australian Journal of Zoology 63(6), 376–382. doi:10.1071/ZO15050

- Ethier, D. M., Torrenta, R., and Kouwenberg, A.-L. (2022). Spatially explicit population trend estimates of owls in the Maritime provinces of Canada and the influence of call playback. Avian Conservation and Ecology 17(1), 1. doi:10.5751/ACE-02075-170112

- Fouquet, A., Tilly, T., Pašukonis, A., Courtois, E. A., Gaucher, P., Ulloa, J., and Sueur, J. (2021). Simulated chorus attracts conspecific and heterospecific Amazonian explosive breeding frogs. Biotropica 53(1), 63–73. doi:10.1111/btp.12845

- Garnett, S. T., and Baker, G. B. (2021). ‘The Action Plan for Australian Birds 2020.’ (CSIRO Publishing: Clayton South, VIC.)

- Garnett, S., and Crowley, G. (1995). The decline of the black treecreeper Climacteris picumnus melanota on Cape York Peninsula. Emu - Austral Ornithology 95(1), 66–68. doi:10.1071/MU9950066

- Garnett, S. T., Hayward-Brown, B. K., Kopf, R. K., Woinarski, J. C. Z., Cameron, K. A., Chapple, D. G., et al. (2022). Australia’s most imperilled vertebrates. Biological Conservation 270, 109561. doi:10.1016/j.biocon.2022.109561

- Hobbs, M. T., Brehme, C. S., and Crowther, M. S. (2017). An improved camera trap for amphibians, reptiles, small mammals, and large invertebrates. PLOS ONE 12(10), e0185026–e0185026. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0185026

- King, S. L., and Jensen, F. H. (2022). Rise of the machines: Integrating technology with playback experiments to study cetacean social cognition in the wild. Methods in Ecology and Evolution 14(8), 1–14. doi:10.1111/2041-210X.13935

- Lambert, K. T. A., and McDonald, P. G. (2014). A low-cost, yet simple and highly repeatable system for acoustically surveying cryptic species. Austral Ecology 39(7), 779–785. doi:10.1111/aec.12143

- Landau, H. J. (1967). Sampling, data transmission, and the Nyquist rate. Proceedings of the IEEE 55, 1701–1706.

- Lees, A. C., Devenish, C., Areta, J. I., de Araújo, C. B., Keller, C., Phalan, B., and Silveira, L. F. (2021). Assessing the extinction probability of the purple-winged ground dove, an enigmatic bamboo specialist. Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution 9, 1–14. doi:10.3389/fevo.2021.624959

- Lee, A. T., Wright, D. R., and Reeves, B. (2018). Habitat variables associated with encounters of hottentot Buttonquail Turnix hottentottus during flush surveys across the Fynbos biome. Ostrich 89(1), 13–18. doi:10.2989/00306525.2017.1343209

- Leseberg, N. P., Venables, W. N., Murphy, S. A., Jackett, N. A., and Watson, J. E. M. (2022). Accounting for both automated recording unit detection space and signal recognition performance in acoustic surveys: a protocol applied to the cryptic and critically endangered night parrot (Pezoporus occidentalis). Austral Ecology 47(2), 440–455. doi:10.1111/aec.13128

- Marchant, S., and Higgins, P. J. E. (1993). ‘Handbook of Australian, New Zealand & Antarctic Birds Raptors to Lapwings.’ (Oxford University Press: Melbourne.)

- Mathieson, M. T., and Smith, G. (2009). National recovery plan for the black-breasted button-quail (Turnix melanogaster). Brisbane.

- Mathieson, M. T., and Smith, G. C. (2017). Indicators for Buff-breasted Button-quail Turnix olivii? Sunbird 47(1), 1–9.

- McKelvey, K. S., Aubry, K. B., and Schwartz, M. K. (2008). Using anecdotal occurrence data for rare or elusive species: The illusion of reality and a call for evidentiary standards. BioScience 58(6), 549–555.

- McLennan, W. (1922). ‘Diary of a collecting trip to Coen District Cape York Peninsula on behalf of H.L. White.’ ( Held at Queensland Museum.)

- Murphy, S., Shephard, S., Crowley, G. M., Garnett, S. T., Webster, P., Cooper, W., and Jensen, R. (2021). Pre-management actions baseline report for artemis antbed parrot nature refuge. Brisbane, NESP Threatened Species Recovery Hub Project 3 2.6.

- Nielsen, L. (2000). Lack of ‘platelets’ in painted button-quail ‘Turnix varia’ in North- Eastern Queensland. Sunbird: Journal of the Queensland Ornithological Society 30(1), 25–26.

- Nielsen, L. (2015). ‘Birds of the Wet Tropics of Queensland & Great Barrier Reef & Where to Find Them.’ (Lloyd Nielsen: Mount Molloy, QLD.)

- Queensland Government. (2022). ‘Species profile—Turnix olivii (Buff-breasted Button-quail).’ https://apps.des.qld.gov.au/species-search/details/?id=1093.

- Rogers, D. I. (1995). A mystery with history the buff-breasted button-quail. Wingspan 26–31.

- Smith, G. C., and Mathieson, M. T. (2019). Unravelling the mysteries of the Buff-breasted Button-quail Turnix olivii: A possible booming call revealed. Corella 43, 26–30.

- Squire, J. E. (1990). Some Southern Records and other observations of the Buff-breasted Button-quail Turnix olivei. Australian Bird Watcher 13, 149–152.

- Vrezec, A., and Bertoncelj, I. (2018). Territory monitoring of Tawny Owls Strix aluco using playback calls is a reliable population monitoring method. Bird Study 65(1), S52–S62. doi:10.1080/00063657.2018.1522527

- Watson, J. E. M., Simmonds, J. S., Ward, M., Yong, C. J., Reside, A. E., Possingham, H. P., et al. (2022). Communicating the true challenges of saving species: Response to Wiedenfeld et al. Conservation Biology 36(4), e13961–n/a. doi:10.1111/cobi.13961

- Webster, P. (2022). Missing in action: The mystery of the Buff-breasted Button-quail. Australian Birdlife 2022, 18–21.

- Webster, P. T. D., Jackett, N. A., Mason, I. J., Rush, E. R., Leseberg, N. P., and Watson, J. E. M. (2022). Nests and eggs of the chestnut-backed button-quail ‘Turnix castanotus’: two new nests and a review of previous descriptions. Australian Field Ornithology 39, 12–18. doi:10.20938/afo39012018

- Webster, P., Jackett, N., Swann, G., Leseberg, N., Murphy, S., and Watson, J. (2021). Descriptions of the vocalisations of the Chestnut-backed Button-quail Turnix castanotus. Australian Field Ornithology 38, 137–144. doi:10.20938/afo38137144

- Webster, P., Leseberg, N., Murphy, S., and Watson, J. (2022). New records of painted button-quail Turnix varius in North Queensland suggest a distribution through southern and central Cape York Peninsula. Australian Field Ornithology 39, 199–205. doi:10.20938/afo39199205

- Webster, P., Leseberg, N., Murphy, S., and Watson, J. (2023). Unravelling the mystery of the Mt Mulligan ‘mystery call’: Analysis of a reported record of a buff-breasted button-quail vocalisation suggests misidentification with painted button-quail. Corella 47, 36–44.

- Webster, P. T. D., Leseberg, N. P., Murphy, S. A., and Watson, J. E. M. (2023). Descriptions of the vocalisations of the painted Button-quail Turnix varius in North Queensland. Australian Field Ornithology 40, 111–119. doi:10.20938/afo40111119

- Webster, P. T. D., Shimomura, R., Rush, E. R., Leung, L. K. P., and Murray, P. J. (2022). Distribution of black-breasted button-quail Turnix melanogaster in the great sandy region, Queensland and associations with vegetation communities. Emu 122(1), 71–76. doi:10.1080/01584197.2022.2047733

- Webster, P., and Stoetzel, H. (2021). First confirmed record of chestnut-backed button-quail Turnix castanotus in Queensland. Australian Field Ornithology 38, 145–150. doi:10.20938/afo38145150

- White, H. L. (1922a). A collecting trip to Cape York Peninsula. Emu - Austral Ornithology 22(2), 99–116. doi:10.1071/MU922099

- White, H. L. (1922b). Description of Nest and Eggs of Turnix olivii (Robinson). Emu - Austral Ornithology 22(1), 2–3. doi:10.1071/MU922002

- Whittaker, R. J., Araujo, M. B., Paul, J., Ladle, R. J., Watson, J. E. M., and Willis, K. J. (2005). Conservation Biogeography: Assessment and prospect. Diversity & Distributions 11(1), 3–23. doi:10.1111/j.1366-9516.2005.00143.x

- Znidersic, E. (2017). Camera traps are an effective tool for monitoring Lewin’s Rail (Lewinia pectoralis brachipus). Waterbirds (De Leon Springs, Fla) 40(4), 417–422. doi:10.1675/063.040.0414