Abstract

COVID-19 restrictions prompted change to clinical placements for students, including a move to a remote supervision model where students, clinical educators, and patients were geographically remote from each other but connected via videoconferencing technology. A total of seven students and 11 clinical educators from occupational therapy and speech pathology participated in focus groups, reflecting on their experiences and perceptions of the rapid transition to remote supervision. Qualitative data were analyzed using a thematic analysis approach. No participants had experience with remote supervision prior to COVID-19. Three key themes were generated from the data: (a) key considerations, processes, and suggestions for remote supervision, (b) impact of remote supervision on relationship development, and (c) development of student professional competencies within the model. This study provides insights and practical considerations for implementing remote supervision and confirms this model can effectively meet students’ supervision needs and support the development of professional competencies.

Introduction

Background

The COVID-19 pandemic and associated restrictions, social distancing requirements, and travel limitations resulted in significant disruption to clinical placements for allied health (AH) students in 2020. Despite restrictions, the School of Health and Rehabilitation Sciences at the University of Queensland (UQ) was committed to students continuing clinical placements, with the ultimate aim of students progressing toward graduation with minimal disruption.

The UQ Health and Rehabilitation Clinics (UQHRCs) offer AH services across the disciplines of audiology, occupational therapy, physiotherapy, and speech pathology. The primary aim of these clinics is to provide pre-entry students with clinical placement opportunities centered around the delivery of clinical services to members of the public, under the supervision of discipline-specific clinical educators (CEs). On placement, students receive direct, synchronous supervision from a qualified allied health professional (AHP) as their CE who supports them to develop clinical competence assessed against discipline-specific criteria (Cantatore et al., Citation2016; McAllister & Nagarajan, Citation2015; Speech Pathology Australia, Citation2018). Uniquely, CEs are not only responsible for the training and education of students, ensuring they develop required clinical competencies, but are also responsible for ensuring clients receive high-quality, evidence-based, and safe healthcare.

Clinical placement model

Proctor's model of clinical supervision and adult learning theories have been widely adopted by AHPs as a means of supporting clinicians and students in formative (development of skills), restorative (supporting the emotional burden of the role), and normative (compliance with professional standards) domains of practice (Mukhalalati & Taylor, Citation2019; Snowdon et al., Citation2020), and underpin the model implemented in the UQHRCs.

CEs must be aware of adult learning theory to determine the most appropriate approach based on their unique context; that is, the clinical setting, the students’ needs, and the purpose of the teaching activity (Mukhalalati & Taylor, Citation2019). For the UQHRC context, this resulted in the development of a model of clinical supervision whereby students are supported to translate theory into practice, developing clinical and professional skills with defined time for reflection and debriefing post-clinical sessions (Mukhalalati & Taylor, Citation2019; Russell, Citation2006).

In the traditional model, UQHRC CEs, students, and clients are colocated at the clinical placement site, with the exception of clinical placements involving delivery of services via telehealth. In all instances, a fundamental element is that CEs observe the clinical interactions between students and clients directly and in real time.

Remote supervision

Remote supervision refers to a model whereby the student, CE, and client are in three locations, all connected via telehealth technologies. Despite geographical distance, the CE is present online to observe all clinical sessions and provide synchronous, direct supervision to students.

This remote supervision model was informed by studies describing supervision of qualified health professionals (HPs) via telehealth. In most instances, these models describe supervision of HPs working in specialist or rural contexts, where access to on-site supervision was either limited or unavailable (Cameron et al., Citation2015; Dudding & Justice, Citation2004; Marrow et al., Citation2002; Martin et al., Citation2018; Moran et al., Citation2014; Takimoto & Udagawa, Citation2022; Varela et al., Citation2021). In these papers, the focus of sessions was typically case-based discussion and facilitation of professional development, as opposed to direct supervision of client care. Most participants reported satisfaction with the model, particularly for reducing isolation, increasing access to professional support, and developing relationships between supervisees and supervisors (Cameron et al., Citation2015; Dudding & Justice, Citation2004; Marrow et al., Citation2002; Martin et al., Citation2018; Moran et al., Citation2014; Varela et al., Citation2021). The success of remote supervision was contingent upon prior experience with the model, the quality of the relationship, communication skills, and the reliability of technology used (Cameron et al., Citation2015; Martin et al., Citation2018; Moran et al., Citation2014; Varela et al., Citation2021).

Although remote supervision is an acceptable and feasible alternative to in-person clinical supervision of qualified HPs, there is a paucity of literature describing remote supervision as the primary method of supervision of pre-entry AH students. When designing clinical placements during the COVID-19 pandemic, the knowledge of and experience with existing frameworks of clinical supervision combined with the literature on remote supervision were used to inform a remote supervision model for pre-entry AH students that supported continuation of students’ clinical placements. The aim of this study was therefore to examine the unique challenges, experiences, and perceptions of students and CEs participating in the remote supervision model of clinical education.

Method

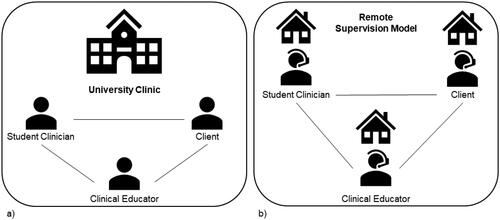

Data for this qualitative study were collected via in-depth focus groups to understand CE and student perspectives of the remote supervision model of clinical placement (). Ethical approval was obtained from the UQ Human Research Ethics Committee (approval number: 2020000940), and informed consent was obtained prior to focus groups being conducted in May 2021. This study was conducted using a constructivist approach, underpinned by social constructionism (Cohen et al., Citation2017). This theoretical framework posits knowledge as being constructed through social interaction and emphasizes the importance of understanding the perspectives of participants in their own contexts (Creswell & Poth, Citation2017). In this study, we sought to understand participants’ view of remote supervision in the context of pre-entry AH student clinical placements.

Figure 1. a) Traditional model of clinical supervision in the University of Queensland Health and Rehabilitation Clinics; b) Remote supervision model of clinical supervision in the University of Queensland Health and Rehabilitation Clinics.

Participants

CEs and students who completed a clinical placement via remote supervision between March 2020 and December 2020 were invited to participate in this study. CEs in the disciplines of occupational therapy and speech pathology were invited to participate by a clinic manager, and participation was voluntary. For the clinical placement to be considered as occurring via remote supervision, the occupational therapy and speech pathology CEs and students had to be in their respective homes (either in Australia or internationally) for the duration of the placement. All clients were based at home, school, or their place of work.

Data collection

Focus groups were conducted with CEs by an experienced qualitative researcher (MHR) external to the UQHRCs, with no prior relationship with participants. Student focus groups were conducted by two novice qualitative researchers (AW & KB) who were trained by MHR prior to conducting sessions. Focus groups were held following completion of clinic placements (after final marking) and with CEs unfamiliar to the students to ensure no influence over student response. As the research team, we collaboratively developed focus group guides (Appendixes A & B) to gain an in-depth understanding of CEs’ and students’ perceptions of the remote supervision model and to ensure a range of perspectives and experiences were garnered. Focus groups are frequently used to garner a comprehensive understanding of the shared experiences, perceptions and attitudes of participants through a moderated interaction (Kitzinger, Citation1995).

Focus groups were conducted and recorded via Zoom. Focus groups with CEs were between 35 and 60 minutes in duration; focus groups with students were between 44 and 48 minutes in duration. Recordings were deidentified and saved according to university data management protocols and transcribed verbatim by a professional transcription service.

Analysis

Inductive thematic analysis of interview transcripts was performed using NVivo version 12 Plus software and guided by social constructionism. In this way, we sought to understand and explore the experiences and perspectives of participants using a data-driven approach (Braun & Clarke, Citation2019; Creswell & Poth, Citation2017). Using this inductive, bottom-up approach, we sought to identify patterns and themes in the data through iterative steps of analysis. First, the coding protocol was developed by one researcher (AW) (data organization) and refined at regular meetings with the research team who have extensive experience across clinical education (AW & KB) and qualitative research methodology (MHR & TR). The dataset was then coded independently by two members (AW & KB), before we met to review preliminary themes and subthemes (data reduction) (Braun & Clarke, Citation2006; Maguire & Delahunt, Citation2017). Next, two of us returned to the complete dataset to ensure consistency of themes generated from the data prior to finalizing the coding protocol and analysis (data interpretation and representation) (Braun & Clarke, Citation2019). Study rigor was guided by Tracy (Citation2010) and the Consolidated Criteria for Reporting of Qualitative Research (Tong et al., Citation2007). We are all AHPs with varying levels of clinical experience, expertise in telehealth, clinical education, and research. Consistent with the constructivist approach, we reflexively acknowledged and considered the impact of our backgrounds and experiences in the interpretation and representation of data.

Results

A total of 15 CEs remotely supervised clinical placements during the study period; 11 (73%) responded and participated in a focus group. CEs were predominantly female (91%), from the discipline of speech pathology (91%), between 29 and 55 years of age, and had 2 to 22 years’ experience as a CE (). A total of 48 students were remotely supervised during the study period, and seven (15%) participated in a focus group. Students were predominantly female (86%), from the discipline of speech pathology (74%), between 22 and 33 years of age and located overseas for their clinical placement (86%) (). No CEs or students reported previous experience with remote supervision. Further detailed participant demographics are provided in and .

Table 1. Participant characteristics–Clinical educators (n = 11).

Table 2. Participant characteristics–Students (n = 7).

CEs and students described their perceptions of remote supervision during the COVID-19 pandemic. Three key themes and 11 subthemes emerged from the data. Themes and subthemes are described below with supporting quotes used verbatim throughout to support interpretation and explanation of themes and subthemes. Individual participant quotes are identified by a unique participant ID (e.g., CE001 or SC001).

Theme 1: Key considerations, processes, and suggestions for communicating and providing & feedback to students; facilitating success; and implementing remote supervision in the future

Three key factors were identified to optimize the success of the remote supervision model: communicating and providing feedback; facilitators for success of remote supervision, and future considerations for the success of the remote supervision model.

Communicating and providing feedback

CEs described making modifications to clinical supervision to better support students participating in remote supervision. Practical modifications included scheduling regular time for pre- and debriefs and changing how feedback was provided within sessions, for example:

I schedule specific times to meet and catch up with a student over Zoom, because you can’t do that incidental catch-up between sessions … like you can with the students that are in-person with you … I just feel like you have to keep checking in … making sure you’re giving opportunity for that student to catch up with you … I think that planning or scheduling those times in [makes] a big difference. (CE005)

For some students, the use of email as the primary means of receiving feedback was at times difficult, particularly for those in different time zones to their CEs: “At the start I emailed … that was … a lot of back and forth, and I think I always forgot about the time difference … I thought I would get back an answer like soonish, but … it goes back to another day” (SC002). As a result, students modified the way they interacted with CEs to gain the most from supervision: “I tend to collate my questions and just ask for a time when I can Zoom my CE” (SC002).

Some students found changes to the way feedback was provided in a remote supervision model challenging at times, but acknowledged the potential benefits of written feedback:

When you’re in-person with your CE you can ask … they give you feedback right away and even during the session, but during a tele-session I think it’s a little bit harder to … read what your CE is kind of feeling … but I think they … made that up with … typing out feedback or letting us know things while they are watching online and then we read it back a little bit later. (SC005)

When I go to visit the site with my CE, it’s much easier for my CE to jump in and model something for me … As opposed to telehealth because … all of a sudden your cameras will be on and your face is there and the client’s like, ‘Oh, what’s happening?’ Yeah, it kind of throws off … the flow of the session I think.” (SC002)

Facilitators for success of remote supervision

Both CEs and students felt that a well-planned placement structure was important for success. From the CE perspective, “planning documentation” and “a good timetable around when things had to be submitted, and also a timetable around when we had a planning meeting, when we had a reflection meeting, when we had supervision” (CE011) facilitated remote supervision placements. Students also acknowledged the benefit of structure, with many recognizing the utility of this with comments such as:

CEs put in a lot of effort [for] structuring … making sure there's a certain routine that we go through … I feel like with just doing everything on your own you can get quite lost, but I think [if] we have a structure that we follow, that is a lot easier. (SC003)

I did some clinician-led sessions before we had students running the sessions and so that really helped me. I remember learning how to screen share … I’d used some boom cards so I knew what the students might be going to use. I think going straight in without having done that would have been really tricky. (CE003)

I did quite a lot of contingency planning with my student based around … what could potentially happen … and what we would do if it’s at the start, or if it’s in the middle, or if it’s at the end … we had lots of plans in place for that. (CE001)

We were all learning very quickly at the same time … I think there was comfort knowing we were all in the same boat … just doing as best we could … talking to people outside the clinic setting in different roles … everyone was doing things differently for the first time and no one had been in this … position before. I felt that we had quite good communication with our managers and regular meetings were built in. (CE005).

Future considerations for the success of the remote supervision model

CEs identified factors which would facilitate future implementation of remote supervision. Factors included the CE to student ratio, development of training resources for CEs new to remote supervision, and opportunities for students and CEs to develop skills in the use of technology.

For CEs inexperienced in the remote supervision model, reducing the number of clients and/or students for the CE to support could allow them to focus on skill development initially:

It depends on how many students you’re supervising at a time … last year, with the rapid transition … I had the luxury of supervising two students and watching one client at a time, which was a very luxurious position to be in … you feel like you could be really comprehensive and have a really good feel for what the student was doing and how they were going with their skills … whereas I’m currently doing four and I feel that’s a push … I feel like I’m very at the surface level … I think the number of students and clients is also important. (CE005)

Previous experience with telehealth in a clinical setting facilitated CEs to feel prepared to deliver clinical supervision remotely. For example, one CE who had supervised students using telehealth to deliver clinical services stated:

I know what we’re doing now … this is how it's going to work, let’s see how we can make it better, so I feel like my perspective of remote supervision has almost changed just because of how prepared I was coming into this semester versus last year. (CE009)

Similarly, students who had clinical placement experience prior to participating in remote supervision felt more prepared than their peers who had minimal prior experience. This apprehension about physical distance and remote supervision was managed in part by additional support from CEs at the commencement of their clinical placement. One student said:

I didn’t feel prepared at all, especially because this was my first placement … And knowing that, I guess … the physical distance … between you and your supervisor … I felt a bit more like I was alone doing the placement … I felt initially … like, ‘oh, I'm doing this alone’ … But I think my CE really did help, and I think I asked a lot of questions as well. I think that helped a lot, especially when, the first few sessions … there was quite a bit of support. I think after that I felt more prepared, but yeah, [initially] it was really quite scary and daunting. (SC002)

I love that we have the option that if … especially at the moment … if you need to get a COVID test … and you can’t be at work it's so nice to know that we can do that style if need be or if things change really quickly I think we could slip back into it relatively easily … so I think that is a nice reassuring in the back of your mind type thing. (CE007)

I met the students in person first. We'd established a bit of a relationship … which I think makes a difference … rather than having started from scratch … via tele; I think that would have been a bit more challenging … particularly with that pastoral care … which I really find helpful with learning a lot about my students. (CE005)

Theme 2: Impact of remote supervision on relationship development

This theme describes the impact of remote supervision on relationship development across two different levels: CE to student, and student to student.

CE to student relationships

Overwhelmingly, CEs felt that it was more difficult to develop rapport and a subsequent supervisory relationship with students via remote supervision:

I think really the whole relationship with the student develops differently than when you’re face-to-face. There’s just something about the face-to-face aspect that helps you develop the relationship and you have to work slightly harder to do that when you’re not in-person. (CE001)

That casual conversation that they have when they're writing up their progress notes and we're all sitting in a room together … it just starts discussions … that people will drop in and out of … Depending on how much time they have to divert their attention … and that will be discussing other things … [than what] they're learning through their lectures. Also, me just giving general information and advice about working clinically … I just find I learn a lot more about the students as we have those discussions. And I just can't imagine having that sort of, chit-chat … via tele. (CE006)

It felt almost kind of normal I guess, but sometimes I feel that it is a bit harder to express yourself over Zoom … and trying to like interpret the facial expressions. (SC003)

I think there's definitely … personalities that we will be more inclined to be successful in this role … for example … we had very quiet students … I tried some of those get to know you games and people thought I was crazy … and, you know, it wasn’t really [in] my comfort zone as well … but I tried to [and] it just … didn’t [work]. (CE011)

Another CE mentioned that they were “very fortunate” and they “had two very strong confident students so … I think even if I had them face-to-face or online I don't think it [was] affected–it was just their personalities” (CE007).

CEs found disclosing to students that remote supervision was a new experience for them also was beneficial for relationship development: “It was good to be able to be a little bit more relatable to the students being back in that learning role as opposed to having lots of experience doing it.” (CE005). Students also appreciated this opportunity to learn together, reporting a feeling of collegiality and teamwork: “It was a very collaborative effort between the CE and us with the clients, when there was a problem or issue. There was more problem solving together, rather than doing it alone” (SC007).

CEs were concerned for student mental health and anxiety, and were particularly concerned about how to support students while separated geographically. They were particularly mindful of international students who had remained in Australia and were isolated from their families, and of international students who had returned overseas and were isolated from their peers:

Both of our students were quite anxious with what was happening at the time, with COVID and lockdown, and one student was domestic and the other student was international in Canada … The domestic student was an international student but had stayed in Australia … There were a lot of personal factors that had come into the student’s experience on placement, and the anxiety for the international student about being able to return to Australia to complete her studies. So in terms of the environment and the external factors … that needed to be taken into consideration in supporting the student in their placement. Not necessarily, you know, supporting them in their issues, but having awareness of those coming into the student experience on placement. (CE004)

I think just the remoteness … it just … didn’t feel like a nice experience doing it online … because you have to work really hard, I think, looking at the student clinician’s sort of non-verbal cues … if they’re becoming upset and letting them have time to process … So I found it more challenging … it’s never easy anyway. I think it’s a challenging thing for educators to do, regardless of if the student is in-person or not, but I think I felt more anxious about it, just because I knew the student wasn’t in the same place at the university. (CE005)

Student to student relationships

Both CEs and students identified that it was more challenging for remote students to develop team-based relationships with peers, especially in terms of sharing resources and experiences. One CE said that remotely, “the teamwork of the students together was lacking … I feel like when we're on site together … it's better for that team building and collaboration” (CE006).

Both CEs and students described that having a mix of in-person and online students made relationship building even more difficult, particularly when sharing resources and experiences.

If I only have one remote student and I actually have in-person students, I find that much harder than say I have at least two remote students or that they are all remote students … I feel like the … one remote student … misses out on sort of that collegial support. (CE005)

Because I'm the only one not in Australia right now, it was a bit hard … a bit more strange for me. Because the rest are meeting each other in the clinic sessions. I'm the only one looking through the camera. I guess that’s a bit more awkward. (SC002)

Theme 3: Student and CE perceptions of how students developed professional competency within a remote supervision model

The third theme explores competency development across two key subthemes: student responses and CE perceptions of student ability to develop professional competencies while remotely supervised on clinical placements.

Student responses to remote supervision

Students indicated an overall acceptance of remote supervision and described feeling adequately supported throughout their placements: “I think my supervisor is very supportive … I wasn’t really worried about being supervised online.” (SC004). Students did not feel that remote supervision impacted the quality of their clinical placement and the clinical supervision they received; “I don’t think I had any different expectations from my supervisor, in terms of … in-person and online. I think I kind of expected the same sort of … support and stuff like that as well” (SC005).

Students did not express concerns regarding their ability to meet competency while being supervised remotely. Students felt they developed sufficient skills in the specific clinical area of their remote supervision placement, which would transfer to an equivalent in-person workplace, for example:

I think with this placement … I did definitely develop some skills … but I guess with every other … area that we would work in, there's always so much more to learn even as a new grad. So I guess … remote supervision didn’t affect how much I was able to learn on paeds. (SC003)

CE perceptions of students’ professional competency

CEs were not concerned about the students’ ability to demonstrate clinical skills and achieve clinical competency. One CE said they “found no difference, really, in assessing the students [professional competency] at all … whether it was face to face or in this mode.” (CE008). Furthermore, as one CE explained:

I felt that the students had lots of opportunity to demonstrate skills and even if they didn’t have opportunities with the clients, we could … set up some clinical activities where they could record themselves doing things … and then sending that through … that was the only way to get to be able to watch them do it. (CE005)

Concerns were raised about the cumulative effect (for some students) of trying to develop clinical, communication and technology skills concurrently while being remote, and the potential impact on professional competency. For example, one CE said, “I had some concerns with students who I was aware English wasn’t their first language … and that we had talked about needing time to process … and I was concerned about the lag in Zoom adding to that as well” (CE005). Despite these concerns, CEs felt that students were able to progress to the expected level of competency, for example: “But those students were fine … I think I was just a little bit concerned how that was going to go on top of all the other things they were having to juggle if English wasn’t their first language” (CE005).

Discussion

The findings of our study describe overall positive experiences with remote supervision of students and highlight opportunities and key considerations to facilitate this model in the future. Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, studies exploring remote supervision with student groups presented the model as an option to provide additional supervision to some students (e.g., supporting off-site students and CEs during an at-risk placement); however, the applicability of remote supervision of direct clinical interactions between a student and client was not explored ((McAllister & Nagarajan, Citation2015; Nagarajan et al., Citation2016; Nagarajan et al., Citation2018). Given there were no known studies exploring CE and student experiences of participating in remotely supervised clinical placements at the time of implementing this model, our study provides a novel contribution to the existing body of literature on models of clinical education of pre-entry students.

Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, remote supervision of AH students generally described situations where students on clinical placement received on-site, in-person supervision of clinical interactions from their primary CE, supplemented by remote, asynchronous supervision from an additional person (e.g., a placement coordinator or a second CE). In this way, remote supervision was presented as an option to provide additional supervision to some students (e.g., supporting off-site students and CEs during an at-risk placement) but not in lieu of in-person supervision of clinical services. While remote supervision may contribute to the student learning experience when used as an adjunct, the applicability of remote supervision of direct clinical interactions between a student and client was not explored.

Research exploring distance education for adult learners has highlighted additional considerations required to facilitate success when compared to in-person education (Cao, Citation2002; Hardy & Boaz, Citation1997). Our findings highlight that establishing online placements also requires additional considerations. CEs progressively developed strategies to ensure they could support students to achieve clinical competencies, and acknowledged that prior development of resources and processes would have been advantageous. Research shows preparation and familiarization with technology and access to resources ensures stakeholders feel more confident using telehealth (Ross et al., Citation2022a, Citation2022b).

Providing students with feedback while on placement is an integral aspect of attaining clinical competence and supports adult learners to remain self-directed and goal oriented (Allen & Molloy, Citation2017; Russell, Citation2006). This study highlights the importance of modifying how clinical supervision and feedback were provided as a key factor for successfully supporting students remotely. Scheduling regular opportunities for pre- and debrief with students in lieu of the informal opportunities that exist in a more traditional clinical placement model was integral to effectively provide feedback to students on performance. Both CEs and students also recognized the pivotal role increased written feedback played in the remote model, whether it was the use of the chat function in Zoom to provide live, in-session feedback (Ross et al., Citation2022a) or emailing feedback post-session to ensure students were able to access information readily.

A successful clinical placement provides students with a positive learning environment that supports them to develop their required clinical competencies (Nyoni et al., Citation2021). Kara et al. (Citation2019) also highlighted that adult learners need to structure and schedule their study to support balance around external commitments. To achieve this within a remote supervision model, CEs identified that a clear placement structure was required, including clear expectations, scheduled and regular meeting times, and deadlines. This ensured students were motivated, aware of their CE’s expectations, and had sufficient opportunity to meet with their peers and CEs for feedback, prepare for sessions, and establish effective relationships (Nyoni et al., Citation2021).

The CE-student relationship is acknowledged as playing an important part in effective clinical supervision (Martin et al., Citation2018; Nyoni et al., Citation2021), with interaction identified as a predictor of learning in adult learners (Kara et al., Citation2019). Some research suggests that detachment may arise in the relationship when the CE and student are not colocated (i.e., interacting solely via videoconferencing) (Miller & Gibson, Citation2004). In our study, both CEs and students felt the remote model impacted their relationship development, which is consistent with adult online learning literature (Kara et al., Citation2019; Venter, Citation2003; Zembylas, Citation2008; Zhang & Krug, Citation2012). Additional strategies were required to support relationship development, with CEs describing intentionally spending individual time with each student online, discussing nonclinical factors (e.g., weekend plans, current lecture content). The ability to meet with students in-person prior to remote supervision was also suggested to assist with relationship development, which has been identified as a key factor in optimizing the quality of the supervisory relationship in a remote supervision model (Cameron et al., Citation2015; Moran et al., Citation2014; Varela et al., Citation2021) and is one of eight major themes found to influence the quality and effectiveness of remote supervision (Martin et al., Citation2018).

Remote supervision was facilitated by previous experience with telehealth for CEs, and previous clinical placement experience for students. Similar to findings from our previous studies, this suggests that a new model of clinical service delivery is most effective when only one aspect is new or unfamiliar (Ross et al., Citation2022a, Citation2022b). Students appreciate the opportunity to focus on one area of skill development (i.e., clinical skills) before adding complexity (i.e., technology) (Ross, et al., Citation2022b). Considered together with findings from our current study, this suggests that remote supervision is likely to be most successful when being remote is the only novel aspect; that is, for CEs and students to have experience with telehealth, and students to have some previous clinical placement experience, where possible, before engaging in remote supervision.

Delivering clinical services within a remote supervision model can provide valuable learning experiences for student learning. Studies have indicated that remote supervision is a suitable means of providing support and supervision to students, although few of these papers used remote supervision in isolation (Carlin, Citation2012; Chipchase et al., Citation2014; Dudding & Justice, Citation2004; Nagarajan et al., Citation2016; Nagarajan et al., Citation2018; Salter et al., Citation2020). In our study, no students or CEs reported impacts to the development of formal competencies, though CEs did describe some concerns regarding the development of additional professional skills which are learnt through in-person interactions in the workplace. This is a consideration for future implementation of this model and could be mitigated by ensuring students are provided with a variety of clinical placements which support in-person as well as remote supervision.

Future considerations

The findings and recommendations from this study have the potential to significantly impact the way clinical supervision is provided to AH students across a wide range of clinical settings. In fact, many of the recommendations from the focus groups described in this study have already been implemented in the UQHRCs and have largely become standard practice in the “new normal” in the context of managing COVID-19 post-2020. Remote supervision has the potential to ensure minimal disruption to clinical placements through ensuring that CEs, students, and clients are all prepared to engage in this model as required (e.g., in the instance of illness or enforced isolation periods). Clinical placement managers should therefore consider how to embed remote supervision into their programs so that CEs, students, and clients are prepared to engage with this model as required. Clinical placement managers should not assume that even experienced CEs will be able to easily transition to a remote supervision model and programs should therefore invest time in developing specific training packages, resources, and systems and processes. details the key considerations for sites considering implementation of remote supervision.

Table 3. Key considerations for implementing remote supervision.

Limitations

There are some methodological considerations specific to this study which limit the generalizability of the findings. The results reflect the perceptions of CEs and students at one university in Brisbane, Australia, and predominantly represent the opinions of CE and student groups in speech pathology, with minimal representation from occupational therapy and no representation from the audiology and physiotherapy disciplines, which may affect generalization of the results and recommendations. Although all students who participated in a remote supervision clinical placement were invited to participate, it is possible that those with strong opinions were more likely to respond.

Consistent with the constructivist approach, we acknowledge that our experience as AHPs, CEs, and researchers with experience in telehealth is likely to have impacted data analysis and interpretation. The clinical supervision needs of CEs and students as explored in this paper are very specific and differ significantly to those required of qualified HPs. Therefore, the results have relevance and applicability to clinical education providers and CEs involved in the design of clinical placements and the provision of clinical supervision to graduate-entry AH students. However, the broader applicability to managers and supervisors of qualified HPs may be limited. To the best of our knowledge, this study is the first to address the challenges and opportunities of implementing remote supervision in clinical placements models.

Conclusion

Remote supervision of students on clinical placement can effectively meet students’ supervision needs and support students to develop the necessary professional competencies. This study provides insights and practical considerations to facilitate implementation of remote supervision of clinical education.

Acknowledgments

The research team would like to thank the clinical educators and students of the University of Queensland Health and Rehabilitation Clinics for their time and effort in supporting this research.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was declared by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Andrea J. Whitehead

Andrea Whitehead is the manager of Speech Pathology and Telerehabilitation Clinics at the University of Queensland. She has had an extensive career as a clinician and strategic leader in both healthcare and tertiary education settings. As a novice researcher, she is interested in researching telehealth in clinical service delivery and clinical education.

Kelly. M. Beak

Kelly Beak is the statewide program manager for Speech Pathology Clinical Education and Training at Queensland Health, where she supports clinical education across the state. Her experience spans both health and university clinical education settings, and she has a passion for supporting innovative clinical education models.

Trevor Russell

Trevor Russell is a professor of physiotherapy and the director of the RECOVER Injury Research Centre. His research focuses on the use of digital technologies for the remote delivery of health services with a particular focus on telerehabilitation technologies. His work is among the earliest and most extensive in this field.

Megan H. Ross

Megan Ross is a postdoctoral fellow at RECOVER Injury Research Centre. She is part of a team focusing on developing effective and efficient technology-supported health services. She has a range of research skills spanning quantitative and qualitative methods, including cross-sectional study designs and data analysis, and focus group discussions and thematic analysis.

References

- Allen, L., & Molloy, E. (2017). The influence of a preceptor-student ‘daily feedback tool’ on clinical feedback practices in nursing education: A qualitative study. Nurse Education Today, 4, 57–62. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2016.11.009

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063o

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2019). Reflecting on reflexive thematic analysis. Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health, 11(4), 589–597. https://doi.org/10.1080/2159676X.2019.1628806

- Cameron, M., Ray, R., & Sabesan, S. (2015). Remote supervision of medical training via videoconference in northern Australia: A qualitative study of the perspectives of supervisors and trainees. BMJ Open, 5(3), Article e006444. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2014-006444

- Cantatore, F., Crane, L., & Wilmoth, D. (2016). Defining clinical education: Parallels in practice. Australian Journal of Clinical Education, 1, Article 2. https://doi.org/10.53300/001c.5087

- Cao, Y. (2002). Adult distance learners in distance education: A literature review. Graduate Research Papers, 462. https://scholarworks.uni.edu/grp/462/

- Carlin, C. H. (2012). E-supervision of graduate students in speech language pathology: Preliminary research findings. ASHA Perspectives on Telepractice, 2(1), 26–30. https://doi.org/10.1044/tele2.1.26

- Chipchase, L., Hill, A., Dunwoodie, R., Allen, S., Kane, Y., Piper, K., & Russell, T. (2014). Evaluating telesupervision as a support for clinical learning: An action research project. International Journal of Practice-based Learning in Health and Social Care, 2(2), 40–53. https://doi.org/10.11120/pblh.2014.00033

- Cohen, L., Manion, L., & Morrison, K. (2017). Research methods in education (8th ed.). Taylor & Francis Ltd. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315456539

- Creswell, J. W., & Poth, C. N. (2017). Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among five approaches (4th ed.). SAGE Publications Inc.

- Dudding, C. C., & Justice, L. M. (2004). An e-supervision model: Videoconferencing as a clinical training tool. Communication Disorders Quarterly, 25(3), 145–151. https://doi.org/10.1177/15257401040250030501

- Hardy, D. W., & Boaz, M. H. (1997). Learner development: Beyond the technology. In T. E. Cyrs (Ed.), Teaching and learning at a distance: What it takes to effectively design, deliver, and evaluate programs (pp. 39–51). Jossey-Bass.

- Kara, M., Erdoğdu, F., Kokoç, M., & Cagiltay, K. (2019). Challenges faced by adult learners in online distance education: A literature review. Open Praxis, 11(1), 5–22. https://doi.org/10.5944/openpraxis.11.1.929

- Kitzinger, J. (1995). Qualitative research: Introducing focus groups. British Medical Journal, 311(7000), 299–302. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.311.7000.299

- Maguire, M., & Delahunt, B. (2017). Doing a thematic analysis: A practical, step-by-step guide for learning and teaching scholars. All Ireland Journal of Teaching and Learning in Higher Education, 9(3), 3351–3354. http://ojs.aishe.org/index.php/aishe-j/article/view/335/553

- Marrow, C. E., Hollyoake, K., Hamer, D., & Kenrick, C. (2002). Clinical supervision using video-conferencing technology: A reflective account. Journal of Nursing Management, 10(5), 275–282. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2834.2002.00313.x

- Martin, P., Lizarondo, L., & Kumar, S. (2018). A systematic review of the factors that influence the quality and effectiveness of telesupervision for health professionals. Journal of Telemedicine and Telecare, 24(4), 271–281. https://doi.org/10.1177/1357633X17698868

- McAllister, L., & Nagarajan, S. V. (2015). Accreditation requirements in allied health education: Strengths, weaknesses and missed opportunities. Journal of Teaching and Learning for Graduate Employability, 6(1), 2–24. https://doi.org/10.21153/jtlge2015vol6no1art570

- Miller, R. J., & Gibson, A. M. (2004). Supervision by videoconference with rural probationary psychologists. International Journal of Innovation in Science and Mathematics Education, 11(1), 22–28. https://openjournals.library.sydney.edu.au/index.php/CAL/article/view/6065

- Moran, A. M., Coyle, J., Pope, R., Boxall, D., Nancarrow, S. A., & Young, J. (2014). Supervision, support and mentoring interventions for health practitioners in rural and remote contexts: An integrative review and thematic synthesis of the literature to identify mechanisms for successful outcomes. Human Resources for Health, 12(10), 1–30. https://doi.org/10.1186/1478-4491-12-10

- Mukhalalati, B. A., & Taylor, A. (2019). Adult learning theories in context: A quick guide for healthcare professional educators. Journal of Medical Education and Curricular Development, 6, 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1177/2382120519840332

- Nagarajan, S., McAllister, McFarlane, L., Hall, M., Schmitz, C., Roots, R., Avery, L., Murphy, S., & Lam, M. (2016). Telesupervision benefits for placements: Allied health students’ and supervisors’ perceptions. International Journal of Practice-based Learning in Health and Social Care, 4(1), 16–27. https://doi.org/10.18552/ijpblhsc.v4i1.326

- Nagarajan, S. V., McAllister, L., McFarlane, L., Hall, M., Schmitz, C., Roots, R., Drynan, D., Avery, L., Murphy, S., & Lam, M. (2018). Recommendations for effective telesupervision of allied health students on placements. Journal of Clinical Practice in Speech Language Pathology, 20(1), 21–25. https://speechpathologyaustralia.cld.bz/JCPSLP-March-2018

- Nyoni, C. N., Hugo-Van Dyk, L., & Botma, Y. (2021). Clinical placement models for undergraduate health professions students: A scoping review. BMC Medical Education, 21, Article 598. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-021-03023-w

- Ross, M. H., Whitehead, A., Jeffery, L., Hartley, N., & Russell, T. (2022a). Supervising students during a global pandemic: A qualitative study of clinical educators’ perceptions of a student-led telerehabilitation service during COVID-19. International Journal of Telerehabilitation, 14(1), Article e6464. https://doi.org/10.5195/ijt.2022.6464

- Ross, M. H., Whitehead, A., Jeffery, L., Hill, A., Hartley, N., & Russell, T. (2022b). Allied health students’ experience of a rapid transition to telerehabilitation clinical placements as a result of COVID-19. Australian Journal of Clinical Education, 10(1), 1–31. https://doi.org/10.53300/001c.32992

- Russell, S. S. (2006). An overview of adult-learning processes. Continuing Education, 26(5), 349–370. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/17078322/

- Salter, C., Oates, R. K., Swanson, C., & Bourke, L. (2020). Working remotely: Innovative allied health placements in response to COVID-19. International Journal of Work-Integrated Learning, 21(5), 587–600. https://www.ijwil.org/files/IJWIL_21_5_587_600.pdf

- Snowdon, D. A., Sargent, M., Williams, C. M., Maloney, S., Caspers, K., & Taylor, N. F. (2020). Effective clinical supervision of allied health professionals: A mixed methods study. BMC Health Services Research, 20. Article 2. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-019-4873-8

- Speech Pathology Australia. (2018). Clinical education in Australia: Building a profession for the future: A national report for the speech pathology profession.

- Takimoto, Y., & Udagawa, M. (2022). Development and evaluation of remote supervision in clinical ethics consultation training. Clinical Ethics. https://doi.org/10.1177/14777509221144568

- Tong, A., Sainsbury, P., & Craig, J. (2007). Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): A 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. International Journal for Quality in Health Care, 19(6), 349–357. https://doi.org/10.1093/intqhc/mzm042

- Tracy, S. J. (2010). Qualitative quality: Eight “big-tent” criteria for excellent qualitative research. Qualitative Inquiry, 16(10), 837–851. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077800410383121

- Varela, S. M., Hays., C., & Knight, S. (2021). Models of remote professional supervision for psychologists in rural and remote locations: A systematic review. Australian Journal of Rural Health, 29(2), 211–225. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajr.12740

- Venter, K. (2003). Coping with isolation: The role of culture in adult distance learners’ use of surrogates. Open Learning: The Journal of Open, Distance and e-Learning, 18(3), 271–287. https://doi.org/10.1080/0268051032000131035

- Zembylas, M. (2008). Adult learners’ emotions in online learning. Distance Education, 29(1), 71–87. https://doi.org/10.1080/01587910802004852

- Zhang, Z., & Krug, D. (2012). Virtual educational spaces: Adult learners’ cultural conditions and practices in an online learning environment. International Journal of Instructional Technology and Distance Learning, 9(7), 3–12. http://www.itdl.org/Journal/Jul_12/Jul_12.pdf

Appendix A

Clinical educator focus group guide

You have been asked to participate in this interview as we are interested in your perceptions, observations and experiences of student performance during the remote supervision clinical placement model.

For the purposes of our discussion today, remote supervision refers to a model whereby the student, clinical educator, and client are in three different locations, all connected via telehealth technologies. When answering the questions below, think about how your supervision of students may have differed when you were remotely supervising students in their delivery of telehealth services, versus supervising students in-person while they were delivering telehealth services.

NOTE: These questions will be used as a general guide for the interview to facilitate discussions.

(1) Tell me about your experiences of working within a remote supervision clinical placement model? Prompts:

• How did your supervision of students differ when you compare supervision of students in person while they deliver tele services with supervision of students remotely while they deliver tele services?

• What elements of the remote supervision model did you find the same as or easier than in-person supervision (of telehealth?)? Why do you think this was the case?

• What elements of the remote supervision model were more challenging? What strategies you use to overcome these challenges?

(2) Do you feel you received adequate information to prepare to deliver this clinical education model?

Prompts:

• What would have helped you to prepare better to supervise students remotely?

(3) How did your experiences working within remote supervision clinical placement model compare to working within a traditional clinical placement model (ie student and clinical educator co-located)?

Prompts:

• What would your preference for the model of clinical supervision be and why?

• How did your supervision of students differ when you compare supervision of students inperson while they deliver tele services with supervision of students remotely while they deliver tele services?

(4) From your observations, how do you feel the students presented in a remote supervision clinical placement model?

Prompts:

• Can you tell me about your observations of student preparedness for this activity?

• What were your observations of the students’ confidence?

• What were your observations of the students’ professional competency? For example, interactions with yourself, their clients, responding accordingly, turn-taking etc..

• What were your observations of the students’ clinical competency?

• What were your observations of the students’ technical proficiency?

(4) Tell me about how you felt in your role of a clinical educator in assessing students’ competency within a remote supervision clinical placement model?

Prompts:

• How confident did you feel in conducting this clinical placement solely via telehealth?

• How confident did you feel with your own technical skills?

• How did you feel interacting with students solely in an online format?

• Did you feel like you were able to provide sufficient feedback in this online manner to support student learning and competency attainment?

• Did you feel that there were some areas (particularly in relation to areas of competency assessment) in which it was easier to support student learning in this remote supervision model? If so, can you provide detail around this?

• Did you feel that there were some areas (particularly in relation to areas of competency assessment) in which it was more difficult to support student learning in this remote supervision model? If so, can you provide detail around this?

○ If you had been supervising the student in person, what would you have been able to do to support the student that you weren’t able to do?

• Did you feel concerned at any point that a remote supervision model would affect your students’ ability to achieve competency overall on clinical placement? If so, could you please explain what your concerns were and why? If not, could you please explain why?

• Did you find it difficult to grade students on particular elements or competencies of the COMPASS (speech path) / SPEF-R (OT) with remote supervision?

Appendix B

Student focus group guide

You have been asked to participate in this focus group as we are interested in your perceptions of and experiences with a remote supervision clinical placement model which you have participated in in 2020.

I would like you to think back to the clinical placement you completed with remote supervision. For the purposes of our discussion today, remote supervision refers to a model whereby the student, clinical educator, and client are in three different locations, all connected via telehealth technologies.

NOTE: These questions will be used as a general guide for the focus group to facilitate discussions.

(1) Tell me about your experiences with the remote supervision clinical placement model.

Prompts:

• What did you like about the remote supervision clinical placement model? Why?

• What didn’t you like about the remote supervision clinical placement model? Why? What would you have liked to change? How could this clinical placement model be changed?

(2) If you think about the clinical placements you’ve completed before, tell me:

• What elements of this clinical placement model were better than your other placements?

• What elements of this clinical placement model were more difficult than your other placements? How did this impact your learning and skill development in this area?

• How would you compare the quality of clinical supervision you received in this model of supervision vs in person supervision?

• If you have completed in-person placement, how did remote supervision compare to in-person supervision of telehealth?

(3) Tell me how you felt while you were in a remote supervision clinical placement?

Prompts:

• How did you react to being told that you would complete your clinical placement with remote supervision?

(4) How prepared did you feel to conduct your clinical placement with remote supervision?

Prompts:

• What made you feel prepared?

• How did this prepare you?

• What other preparation or training would you have benefited from?

(5) How were you able to manage your supervision with your clinical educator during remote supervision clinical placement model? What was it like interacting with everyone in the session?

Prompts:

• How was your interaction with your clinical educator?

• How was your interaction with the client?

• Do you have comments regarding feedback you received during the remote supervision clinical placement model, either the type of feedback your received or how that feedback was delivered?

(6) If you are not graduating this year, how would you feel about doing further clinical placements within a remote supervision model?

Prompts:

• Are there particular aspects you would be concerned about?

• Are there particular aspects you would enjoy/benefit from?

(7) What was your overall satisfaction with the remote supervision clinical placement model?

Prompts:

• Why do you say this?

• Do you feel that you received sufficient supervision via remote supervision to work confidently in this area of clinical practice once you graduate from university?

• How would you feel if you did not undertake another clinical placement in this area of clinical practice before graduation?