Abstract

Higher education institutions have been following the global trend of advocating open educational resources (OER) for tuition and learning. In the South African context of higher education, there is also an increasingly strong call for decolonisation in educational content. However, there is a lack of knowledge and theories for the decolonisation of learning content. This study sought to establish the possibilities of decolonisation of OER in digital learning. To employ the appropriate lens for the decolonisation of content, the study opted for contextualised theory, contextual knowledge world views, and the African indigenous knowledge frameworks, while following the Transformative Learning Theory. This theory made it possible to follow the decolonisation elements relevant to low-income contexts. Consequently, the decolonisation lesson guided the appropriate systems for the decolonisation of the tuition content. After decolonisation, the concepts of Africanisation and transformative learning were considered by using the Technology Appropriation Model as a guide for adopting and developing OER appropriate for the African context. The study employed the qualitative approach and case study strategy by focussing on one of the largest comprehensive open distance e-learning (CODEL) institutions in South Africa and on the African continent. The study established that CODEL encourages the use of OER for the decolonisation of tuition content. However, there is still a lack of strategies, models, policies, and practical guidelines for the decolonisation of OER. Therefore, the study proposed the decolonisation of an e-learning content model that academia can use to advance the decolonisation of e-learning content.

Introduction and background

The Open Educational Resources (OER) initiative – which was introduced in 2001 during the Commonwealth Congress in Berlin – emerged with particular opportunities. The OER initiative proposal was based on its potential to close the existing gaps generated by inequalities and the lack of infrastructure in low-income countries (UNESCO, Citation2002). The major assumption was that OER are intended to be freely accessible to any information seekers (Grimaldi et al., Citation2019). That is noticeable since there is a significant increase in OER adoption in both low-income and high-income countries (Dejica et al., Citation2022). However, it does not signify that all OER users are well equipped for the use of these resources, mainly because the digital divide still exists – particularly in low-income countries (Bordoloi et al., Citation2021). In academia, OER are applauded, because they have widened the scope of learning by providing numerous teaching and learning opportunities (Mncube & Mthethwa, Citation2022).

The popularity of OER has emerged in an era in which numerous African universities in different spheres of academia are advocating for decoloniality. Decolonisation is an intense phenomenon, because it calls for questions on coloniality (Fanon, Citation1963). Practically, decolonisation is described as “the process by which colonial powers transferred institutional and legal control over their territories and dependencies to indigenously based, formally sovereign, nation states” (Duara, Citation2004, p. 2). Furthermore, decolonisation is associated with the “undoing” of colonisation and seeks to overturn the orders of the colonial condition (Moeke-Pickering, Citation2010). The concept of decolonisation has been broadly applied to numerous entities in the ideology of transformational nations (Jansen, Citation2019).

The decolonisation phenomenon has been recognised in numerous spheres, including those of race and apartheid (Oyedemi, Citation2021); politics (Ndlovu-Gatsheni, Citation2021); science and engineering (Nwokocha & Legg-Jack, Citation2024); and computing and technology (Reddyhoff, Citation2022; Tompkins et al., Citation2024). Decolonisation involves a multidisciplinary action that requires continuous attention from all disciplines. The literature confirms that decolonisation can be achieved easily through education (Baloyi, Citation2024). Higher education institutions continue to advocate for the decolonisation of education in postcolonial countries (Mampane et al., Citation2018). This can be achieved by focussing on and employing an Afrocentric epistemology, which is at the heart of this educational reframing (Fataar, Citation2018), in the hope that the new generation can be realigned with contextual knowledge, culture, beliefs, and values. This may be a meaningful initiative to break colonial boundaries. OER are considered highly relevant in the decolonisation and transformation of the educational environment (Olivier, Citation2020). This needs to be achieved to fast-track decolonisation by continuously developing learning content. In such an event, institutions and academics need to use opportunities to develop content suitable for their contextual settings (Mudavanhu et al., Citation2024).

Employing OER in decolonisation may make it possible to keep up with trends and developments in the current era, such as the Fourth Industrial Revolution (4IR). Higher education institutions should capacitate academics on the decolonisation of curricula for change (Al-Azab et al., Citation2022), which encourages integration between indigenous knowledge systems and new and emerging technologies (Oguamanam, Citation2022). The decolonisation of the curriculum may contribute to diversifying educational resources (Heleta & Chasi, Citation2024), which, in turn, may offer more opportunities for academics to decolonise learning content. In the event of collaboration, open sources and open access are aligned and characterised by OER. The decolonisation of online learning content has vast possibilities to reach a wider audience. Higher education institutions recognise their decolonisation responsibility by promoting democratic and diverse access to knowledge and focussing on the development of localised educational governance and institutional policy for the development of open educational practices (OEP) and the licencing of quality OER (Wimpenny et al., Citation2022). The literature affirms that although the decolonisation of knowledge and the educational system (Rangan, Citation2022) has been explored, there is still a need to recognise and transform decolonisation processes. However, the decolonisation of e-learning content has not been well articulated in the existing literature. Therefore, the study sought to provide answers to the following research question. How can open educational resources contribute to the decolonisation of e-learning content?

To find answers to the existing problem, the study was carried out in a comprehensive open-distance e-learning (CODEL) institution in South Africa. The selected institution is the largest in South Africa and beyond Africa, since it can accommodate more than 400,000 students (UNISA, Citation2022). This institution employs academics from different South African provinces and from different African regions and countries. The characteristics of employed academics seem to demonstrate differences, based on ethnicity, gender, culture, and values. The selection of this research context was based on the fact that it provides tuition and learning through e-learning and advocates for the utilisation of OER. The ODeL institution might be doing well in the development and adoption of OER. The existing literature opines that the study context was the first in the world to have an approved OER strategy (De Hart et al., Citation2015).

Contextualisation of OER

In the transformation of the educational context, it is necessary to contextualise the development of OER. OER are developed in complex contexts in terms of location, format, language, specific culture, specific curriculum, teaching methods and infrastructure (Bradshaw & McDonald, Citation2023). For example, academics from underserved groups should not convert OER into their native tongue and reuse it without considering representing their own voice and are appropriate for local circumstances (Hodgkinson-Williams & Trotter, Citation2018). To validate the proposition of the potential of OER to make a positive contribution to a selected context, one of the patterns is that OER needs to be contextualised before they are adapted and shared for open education (Nascimbeni et al., Citation2021). These dynamics create social exclusion, particularly if some of the issues are not well addressed before the appropriation occurs (Mncube et al., Citation2021). Therefore, the entire process of contextualising OER can contribute to reducing the barriers created by colonisers.

Africanisation realities in the development of OER

In an African context, the realities of indigenous African knowledge have not been widely recognised or fully considered in the development of OER to accommodate the decolonisation of learning content. Africanisation involves incorporating, adapting, and integrating other cultures into and through African visions to provide the dynamism, evolution, and flexibility so essential in the global village (Makgoba, Citation1997). Academics and universities become more relevant for contextualised realities via the legitimisation of African indigenous knowledge systems (Mbah et al., Citation2021; Rumajogee, Citation2002). This must be done at the expense of promoting the voices, artefacts, histories, customs, and knowledge of the indigenous communities in an African context. African universities through formal engagement with indigenous knowledge can support social and environmental justice, which is at the core of sustainable development. Therefore, in the African context including South Africa, there is a crucial need for the development of contextualised OER. Academics need to demonstrate the characteristics of the structure, work, and teaching to help students and other individuals to make sense of the world around them using OER (Motaung, Citation2024). Considering indigenous knowledge in Africa can help decolonise education and promote sustainable development that does not ignore African realities through education (Mbah et al., Citation2021).

Transformative approach for appropriating OER

Several development initiatives are occurring in the spheres of education, and, as one of the artefacts emerging in academia, OER have been transforming; particularly because of the advent of Industry 4.0 and Society 5.0. Industry 4.0 refers to the emergence of automation and digitisation, whereas Society 5.0 promotes human centricity in response to modern societal issues, such as global climate change, pandemics and hybrid (Golovianko et al., Citation2023). Transformation plans for academic preparation must be evaluated in terms of the subjects and skills to be covered, as well as the delivery methods to be employed (García-Peñalvo, Citation2020). All these developments present opportunities, such as hyperconnectivity, artificial intelligence (AI), the Internet of Things (IoT), blockchain, 3D printing, cybersecurity, big data, and cyberphysical systems, which, in turn, enable new practices and business models (Rodríguez-Abitia & Bribiesca-Correa, Citation2021). Although technologies have been acknowledged at numerous universities – although they have achieved their goals; particularly their educational goals – the maturity of their digital transformation programmes has been compromised (García-Peñalvo, Citation2021). Because the appropriation of OER occurs in digital spaces, the transformation of content digitisation becomes a necessity.

The adoption and development of OER cannot be denied any kind of transformation, be it of content or technology. The transformation of the educational environment, based on digital technologies, contributes to the improvement of academic activities in tuition and administration (Mncube & Mthethwa, Citation2022), although institutions in low-income countries may still be behind in terms of technological transformation. In South Africa or Africa as a whole, a digital divide is also an issue that continues to impact digital access, the affordability of devices and data being key inhibitors (Masavah et al., Citation2024). Higher education institutions are undergoing radical transformations driven by the need to transform education and training processes in record time, with academics lacking innate technological capabilities for online teaching (Wanjiku Wang’ang’a, Citation2024). Innovative activity requires the availability of appropriate learning systems for the use of the latest technologies (Mncube et al., Citation2023; Nansubuga et al., Citation2024). This encourages countries and higher education institutions to incorporate new technologies in their strategies and the development of user skills (Nansubuga et al., Citation2024).

Conceptual framework

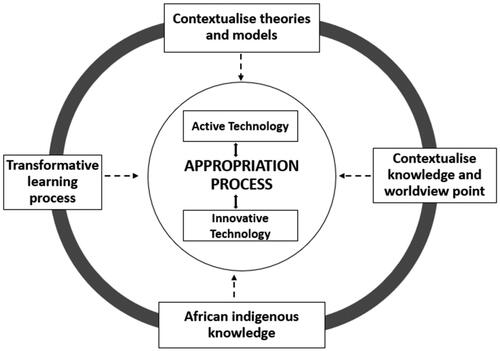

This study was informed by different concepts related to decolonisation, Africanisation of content, and the use of ICT systems. To achieve this, the study opted for various concepts, such as contextualised theory and model, world views of contextual knowledge, and indigenous African knowledge (Van der Westhuizen & Greuel, Citation2017); the concept of the transformative learning process (Mezirow, Citation1997); and the appropriation process (Carroll et al., Citation2002). After engaging with the concepts, the researcher was able to propose a new conceptual framework (decolonisation of e-learning content), as illustrated in .

Contextualisation of theories and models

Decolonial actions encourage the contextualisation of practices, methods, models, and theories. This is related to the application of the realities of indigenous knowledge realities of any given context. Constructivist theories, situated or contextualised learning theories, multimedia learning cognitive theories, self-regulated learning theories, output hypotheses, flow theory, collaborative learning theories, and motivation theories must be applied in practice (Zhang et al., Citation2023). Considering contextualised practices and theories has the capability to contribute to the new knowledge either in a particular context or in global spheres. For example, referring to indigenous African knowledge which refers to the system of understanding what emanates from “Africanisation,” which implies understanding of the African context and the socioeconomic realities of African people (Van der Westhuizen & Greuel, Citation2017). This encourages or emphasises the consideration of existing methodologies, models, theories, and other processes developed in the existing African context. Recently, gaps have been occurring in open educational practices in the global south; particularly in terms of contextualised resources to support the student agency (Olivier et al., Citation2022). In addition, African scholars and content developers in academia still rely on Western theories to solve African problems (Shai, Citation2023; Shokane & Masoga, Citation2023). Relying on Western theories is not bad at all; however, it is the time to try and simplify learning for native learners by considering their practices, methodologies, and culture. Therefore, scholars can look at the possibilities of integrating both Western and African theories. In so doing, the integration has a great potential to simplify learning content.

Contextualisation of knowledge and worldview points of view

The global south is in a better position to expose their values, perceptions, knowledge, and viewpoints concerning knowledge creation and distribution. The current curriculum marginalises and subjugates African perspectives and epistemologies in favour of western perspectives (Sadiki & Steyn, Citation2022). The worldview of contextual knowledge needs to reflect on teaching with a curriculum that informs African people. This is confirmed by Thabede (Citation2014, p. 234), who opines that the African point of view must reflect on “African cultural beliefs, practice and values.” OER developments have acquired social and cultural meaning beyond their ordinary functions (EdTech Hub, Citation2023). Furthermore, the contextualised knowledge can only be expressed through procedures in a particular context and with the clear intention of handling a specific situation (Radović et al., Citation2021). Relying on contextualised knowledge and viewpoints in academia is essential for academics and students, as they should be given more opportunities to apply their knowledge in the context of the (future) working environment (Gulikers et al., Citation2008). Higher education studies are also concerned with the impact of civilisations, cultures, institutional organisations, and contexts on West approaches to knowledge, education, and research (Hayhoe & Pan, Citation2016). Therefore, this concept promotes the development of new contextualised knowledge using OER, and this knowledge is suitable for African environments.

Indigenous knowledge

The African context has been known and characterised by its indigenous knowledge. The existing knowledge has the potential to contribute to the decolonial agendas. Indigenous knowledge cannot be distinct from indigenous peoples who have a long and rich connection to the environments from which they descended a connection that has informed a deep and multifaceted understanding of the relationship between human well-being and the environment (Zurba & Papadopoulos, Citation2023). This implies that the African scholars should take a role in the creation and distribution of indigenous knowledge. However, African scholars have not made significant contributions to the production of indigenous knowledge (Olaopa & Ayodele, Citation2022), which continues to pose questions as to whether Africans are falling behind in knowledge production and who is going to capture and preserve their indigenous education systems.

Even in the current fourth industrial revolution era, indigenous knowledge can be created and managed through information and communication technology systems. ICT as a means of preserving African knowledge and cultures in a more liberal viewpoint holds that ICT should be used as long as it promotes indigenous knowledge (Warbrick et al., Citation2023). The appropriation of OER as enabler of Africanisation of content relies on ICT systems and platforms. Therefore, the OER development, which encourages the infusion of content that addresses African indigenous knowledge. Cannot be separated from the ICT as an enabler. This is an indication that treating indigenous knowledge, OER and ICT cannot be treated in isolation from each other.

Transformative learning process

Our cultural and linguistic frameworks, referred to as frames of reference, shape the meaning we assign to our experiences. These frameworks influence our beliefs and intentions, influencing our thoughts, perceptions, and emotions. The transformative learning process not only addresses several issues related to culture, norms, and values (Mezirow, Citation1997); it also fosters self-direction. The emphasis is on creating an environment in which students become interested in learning in groups and in assisting one another in problem solving (Mezirow, Citation1997). The essence of this process is its suitability for learning practices in a higher education context. Therefore, in the transforming African context, it encourages students to be self-directed learners, who use more OER for learning. Therefore, at the development stage where academics create or develop learning content using OER, regardless of subject or content specifics considerations such as culture, beliefs, norms, and context must be considered. That could contribute to contextualised knowledge. It cannot be disputed that as the human race, we are different base on our context, locations, beliefs, morals, and social values. The transformative learning process encourages scholars to be themselves at the developmental stage. This is the time where the human distinctiveness has to be embraced and respected.

In this context, the transformation of the learning process is highly recognised through the adoption of ICT for e-learning. ICT is currently an important basis for transformative learning and development of the knowledge economy, including indigenous knowledge. The technical and economic growth of high-tech innovation significantly improves computing power and intellectual potential, rapidly changing outdated standards and technological platforms in information and communication systems (Akhmedov, Citation2023). Therefore, the concepts of transformative learning in this study can be described as the process that considers the development of e-learning content through consideration of human capital, culture, context, and ICT as a tool for innovation. Using OER as an artefact is the final stage of processing and making content accessible in different societies.

Appropriation

The appropriation process focusses on existing ICT systems used in OER development (Mncube et al., Citation2021). These systems play a role in determining if academics are using OER or if they stop developing OER, based on encountered opportunities and challenges. The social aspects involved in Africanisation result in decolonisation being well-attended in academia. Academics need to be comfortable with appropriating technology when decolonising e-learning. The actual process of decolonisation enables the acquisition of systems or technologies designed and systems used (Carroll et al., Citation2002). The significance of the appropriation phase manifests if all four significant decolonisation concepts are addressed or recognised, resulting in the appropriation of technological systems carrying knowledge, information and decolonised content.

The proposed concepts have an impact on the decolonisation of the e-learning context. The application of these concepts, therefore, encourages the value of the societal issues which inform the existing population and more solutions to decoloniality. Lesson learnt, if the researcher is studying decolonisation of e-learning (which is an IT artefact), cannot engage with decolonisation or Africanisation theories or concepts in isolation from ICT theories. The appropriation of ICT should comprehend the transformation of emerging technologies and other social realities to enhance organisation productivity (Mncube et al., Citation2022). That was the main reason for the study to incorporate all concepts to propose a main framework relevant to the decolonisation of e-learning.

Methodology

This study relied on the interpretivism paradigm, to reveal and interpret the facts on the potential impact of OER on the decolonisation of e-learning in an CODeL context. In the interpretivism paradigm and in qualitative research, the case study was necessary to study the information system phenomenon (Jensen & Aanestad, Citation2007). In interpretivism research, meanings are disclosed, discovered, and experienced, and, therefore, the emphasis is on sense-making, description, and detail. For example, for the antinaturalistic interpretivism researcher, human action constitutes the subjective interpretation of meaning (Anchin, Citation2008). Therefore, the creation of meaning is underscored as the primary goal of interpretivism research, to reach an understanding of social phenomena. Based on that, it can be assumed that opting for the interpretivism paradigm and the qualitative approach enabled the researcher to provide rich descriptions necessary for the interpretation of the findings and the full understanding of the contexts.

Along with ontological and epistemological viewpoints, the researcher’s positionality is influenced by their background, identity, experiences, values, and preconceived notions. A black African working as a researcher at an CODeL university. The researcher was born and raised in South Africa, where he or she lived through most of the crucial historical periods, including apartheid and the post-apartheid period. Such events put us in a better position to engage in this type of research. The current CODeL institution, which supports the appropriation of OER (Mncube et al., Citation2021) and decolonisation education, influences the reasons for conducting such a study. It was challenging to consider the decolonisation of ICT while educating on the subject. ICT is efficient in any organisation, especially higher education institutions (Chen et al., Citation2023). Decolonising e-learning content was one of the gaps that needed to be filled to address some of the institutional emergent challenges, such as decoloniality.

The study opted for a qualitative approach. Opting for a qualitative approach in studying decolonisation was considered for three major reasons: the researcher’s view of the world; the nature of the research questions; and the practical reasons associated with the nature of qualitative methods. To provide answers to the research question, the study opted for the following concepts: the transformative learning process (Mezirow, Citation1997) and a contextualised theory and model; contextual knowledge world views; indigenous knowledge, as proposed by Van der Westhuizen and Greuel, (Citation2017); and appropriation (Carroll et al., Citation2002). Therefore, a qualitative approach was necessary to establish how the decolonisation of e-learning takes place when academics adopt or develop e-learning content using OER in an CODeL university.

The study opted for a single case study as the research design. The case study can also be referred to a single case which may involve the opportunity to study several contexts within one domain. The opted single case (CODEL), which is composed of more than eight schools and more than eighty-five academic departments. The CODEL institution has more than two thousand five hundred academics employed. The researcher selected the case study design because it is described as an intensive approach to the study of individuals, events, domains, and or certain environments (Trochim et al., Citation2015).

The use of snowball sampling helped because the first participants selected from a heterogeneous institution with eight colleges, 18 schools, and 85 departments. Snowball is a selection process that is usually done by using networks or connections. Once ethical clearance and permission to research a CODeL was obtained, that was the beginning of approaching academics. Due to the heterogeneous and large size of the institution, the researchers wrote letters to all seventy (p. 70) chairs of departments (COD) to request permission to conduct research in their departments. Most CODs responded with the names of the possible OER users, developers, and academics who were well-versed in the departments. Upon receiving names of potential academics, the researcher went to the UNISA staff directory, which contains the UNISA employees’ details including the contact numbers and emails. All names given by the CODs were considered in the first process and emails were sent requesting permission. Some of the academics responded positively, and others declined the invitation, while some did not respond at all.

The final total sample size of the study was forty-four (p. 44) academics. Additionally, two documents such as the CODEL policy and the UNISA (Citation2011) inauguration report were analysed as part of data triangulation. This was done to validate academic views on facts related to Africanisation and decolonisation. Initially, the first heterogeneous sampling of the representation of participants considered professors, associate professors, senior lecturers, lecturers, and junior lecturers at each college, school, and department participating in the study. In the presentation and discussion of the data, the professors and associate professors were combined into one category, “professors.” In qualitative research, sampling is not used to generalise information but rather to elucidate the phenomenon under investigation (Creswell & Poth, Citation2016). All participants (p. 44) were selected because they were responsible for tuition and research in different departments. The sample size was sufficient, based on the representation of the participants. Furthermore, given the researcher’s participation in data transcription, analysis, and presentation, the saturation point was reached, and similar themes that were recurring were noticed.

The study relied on semi-structured interviews to collect primary data from academics. The study conceptual framework used a guide to develop semi-structured interview questions and served as the lens to guide the interview process. The focus of instrument development was on the decolonisation process, as the main research question was to establish how academics decolonise e-learning content for tuition in an CODEL. The main data source was academics, as they are appropriating OER in their daily lives at the CODeL institution. The study was particularly interesting to hear the views of academics on the usage, adoption, and development of OER for decolonisation at the institution. Therefore, academics could contribute to the potential role of OER in the decolonisation of e-learning content. The open-ended interview questions covered several topics related to the decolonisation of e-learning. Secondary data sources, such as documents, were used in the form of data triangulation to establish relations from academic data.

All the data generated from audio to Microsoft Word was imported into NVivo qualitative data analysis software. The transcripts were anonymised, coded in NVivo, and analysed. As part of data analysis, coding has been used in different approaches, varying in terms of the way in which theory is incorporated into the coding strategy (Coffey & Atkinson, Citation1996). The researcher reviewed all the coded data and themes into main themes and relationships. After recognising or amalgamating the themes, the researcher began to redefine and rename the final themes to finalise the analysis.

The researcher adhered to ethical considerations. The study population was ODeL employees and permission had to be obtained from the ODeL institution (i.e., UNISA). The UNISA Policy on Research Ethics (2016, p. 8) encourages that “research involving UNISA employees, students, and/or data must comply with the UNISA policy to conduct research involving UNISA employees, students, or data.” Therefore, permission was requested and granted to conduct research at UNISA, in this case, to conduct interviews with UNISA academics.

Findings

The purpose of this study was to determine how OER artefacts could aid in the decolonisation of e-learning content. The results demonstrate that academics are involved in the creation and use of OER in their instruction. Academics agreed that OER can be used as the primary tool for decolonising OER in the context of higher education, which is in line with the main study topic. The findings are presented based on the proposed conceptual framework, themes such as OER as a decolonial tool; integration of culture and values in the OER decolonial process; and the e-learning platforms emanated as the main actions for the decolonisation of the content of e-learning.

OER as a decolonial tool

OER viewed by academics as a crucial instrument for decolonising online learning materials. They provided instruction using contextualised OER, which facilitated students’ learning. If properly used in a setting where students are thinking and learning, contextualisation is crucial, since the students may quickly acquire or comprehend the subject matter. Additionally, OER support decolonisation because they provide academics the freedom to choose the best information that fits their local context.

OERs are significant in the promotion of Africanisation because academics can develop OERs to increase African knowledge written in indigenous languages. For example, some academics develop OER to close existing gaps by creating OER contextualised knowledge written in indigenous languages. Academics are therefore in a better position to Africanise and distribute knowledge through OER to fulfil one of the institutional mandates. Academics are passionate about the promotion of African knowledge through OER and the production of learning materials in local languages. The enabling institution encourages academics to comply with the ODeL agendas.

The institution expects academics to produce African knowledge and African ways of doing, thinking in the public spaces in a form of OER to support students, and the current institutional curriculum transformation policy encourages the adoption of OER. (Academic 32)

Academics focused on promoting African scholarship and the Africanisation of OER content are developing OER. In addition to the Africanisation of content, academics develop OER, because there is a shortage of content and knowledge produced by African scholars in the African context. Therefore, the developed OER has the potential to create opportunities for African academics to increase knowledge that represents African perspectives, thus enriching African students.

Africanisation involves the centring of Africa and African intellectual thoughts, knowledge systems, epistemologies, innovations and technologies, whilst not neglecting understanding and learning from those knowledge systems, philosophies, epistemologies and or insights which derive from other contexts, regions and/or the broad global community. (UNISA 2010 Report).

In the process of using OER in the Africanisation process, academics still value foreign content and theories. The existing theories and content from the West continue to be used as a guide to develop contextualised content and theories suitable for the African context.

Integration of culture and values in the decolonial OER process

The diversity of academics, based on their disciplines and cultural backgrounds, plays a role in showing the different strategies to infuse the culture and value elements involved in decolonised learning content. At UNISA, academics are expected to develop study material, such as tutorial letters, module outcomes, and study guides, for their subjects. The tutorial letters refer to documents that are prepared to communicate on issues regarding teaching, learning, and assessment (UNISA, Citation2019) with registered students in each module offered at the ODeL institution. Academics use practical examples based on their different backgrounds and knowledge. This is done to accommodate all students, even those who are in rural settings (considered underprivileged communities). History still plays a role in cultural considerations, as academics can align and infuse cultural aspects, based on their upbringing in the South African context. A practical example made by an academic participant:

Back in the days, many of us did not have watches to wake us up in the morning, instead we relied on the sun and the sun and we [academics] were always on time at school. (Academic 15)

During drought seasons, my grandmothers will go to the royal place of Nomkhubulwane [a Zulu goddess of rain] to ask for rain. (Academic 17)

On the other hand, a minority of academics still struggle to infuse cultural values in the development of e-learning content. Some academics seemed reluctant to do so, e.g., some academic participants mentioned that, when conducting lessons on sensitive issues such as sex education, they find themselves compromised, because the particular group of people in the South African context does not feel comfortable with the issue, a trend that has originated in their geographical upbringing and their different views on this type of topic.

I will compromise the other different groups of students who do not have any problems when it comes to sex education. (Academic 11)

Virtual systems for OER decolonisation

Academics started to be innovative by developing different technologies (platforms) to accommodate OER and adhere to the decolonisation of e-learning content. Some of the emerging developments are custom-made applications and created online common spaces. Custom applications are indicated that are compatible with smart devices that many students own. Academics promote the use of custom-made mobile applications and podcast platforms to provide ease of access to OER. That is confirmed by the institutional policy.

CODeL [institution] will make effective use of educational and social technologies in learning programmes in appropriate and innovative ways that improve the quality of teaching and learning. (CODeL Policy)

All the aforementioned platforms or applications were described as easily accessible through smartphones, which is regarded as an advantage, because numerous academics and students own smart devices. Academics prefer to develop these applications and systems, because they are convenient and easily accessible to their students, which means that they can use them wherever they are – on the train, in restaurants, and in gymnasiums. Academic participants further recommended that even the size and types of file streaming should not be too lengthy and more suitable for OER, which are accessible through smartphone applications.

I developed a mobile app for practical teaching skills, so it is already there; I had pictures on it. (Academic 2)

Some academics recommended institutions creating common platforms for OER only, with classified information according to schools, colleges, departments, and subject-specific areas. In addition to online platforms, they noted the need for relevant systems and application software that are compatible with OER. Academics proposed that OER platforms should also cater to all OER-related research and community engagement, which encourages the decolonisation of e-learning content.

Any enhancement features can be database, system, platform… I think a platform would be. If we can have a separate platform…platform… where academics can share or exchange their opinions and experience regarding OER, and we should also encourage. (Academic 3)

After conceptualizing and decolonising e-learning content, academics recommended that institutions consider the use of artificial intelligence (AI) for institutional OER. Resulting of the advent of the 4IR, academics opined that machine learning can assist in the decolonisation of e-learning content in the development, adoption, and distribution of OER. They assumed that institutions investing in robotics for the OER may speed up the process. Some of the assumptions of the academics were that human interaction can be a misleading factor in the search for OER, while AI is more accurate.

If we integrate robotics, into the facilitation of OER…OER… I mean that that robotics can help you, they can talk to you, they can engage with you, they can lead you to the information that you are looking for. (Academic 6)

Discussion

Contextualisation of African theories and knowledge

OER are gradually contributing to the decolonisation of knowledge and education. The findings showed that OER can contribute to the decolonisation of e-learning content. This is elicited from the fact that academics have come to realise that OER innovations can facilitate the Africanisation of learning and research content. This is confirmed by Makgoba (Citation1997:199) who defines the term Africanisation as:

It is not a process of exclusion, but inclusion… is a learning process and a way of life for Africans. It involves incorporating, adapting, and integrating other cultures into and through African visions to provide the dynamism, evolution, and flexibility so essential in the global village. ‘Africanisation’ is the process of defining or interpreting African identity and culture.

African countries still face difficulties in constructing local curricula, as the ideas of high-income countries are still considered predominant (Oyedoyin et al., Citation2024). On the other hand, Western curricula are not always helpful in the African context, because there is a lack of commonalities between the prescribed content and the experiences of the targeted audience (Matsilele et al., Citation2024). The research findings revealed that African scholars can develop their own OER that are relevant to their educational systems, cultures, and theories. This may eliminate some perceptions that “Africanisation of the curriculum seen as an antidote to the rigid imposition of western models” (Rumajogee, Citation2002, p. 7). Rumajogee’s opinion supports the research findings showing that African academics have made significant contributions to OER. Therefore, integrating Africanisation in the curriculum encourages the development of scholarship and research established in African intellectual traditions (Gumbo et al., Citation2024) and the adaptation of teaching and learning relevant to African realities and conditions (Bradshaw & McDonald, Citation2023).

Several or all African countries are still facing obstacles, such as inequalities and access to education and resources. Unlike any other low-income country, numerous rural schools in South Africa are under-resourced, with predominantly poor learners and poor parents (Dreyer, Citation2018). Given such challenges, the decolonisation of OER must consider eliminating some of the challenges. Therefore, the decolonisation of e-learning content is more valuable if the OER developers consider the needs, theories, and methodologies of society and the context in which these are appropriated.

African indigenous knowledge in Africa

Indigenous knowledge can make a potential contribution to the decolonisation of e-learning content and create more opportunities to produce contextualised content. This is confirmed by Rumajogee (Citation2002) and Sadiki and Steyn (Citation2022) observe that indigenous knowledge is essential for education, as it involves removing the barriers that have silenced non-Western voices in a contextualised education system and battling the epistemological injustices of a system dominated by Western thought. This is not only beneficial for academics, but also for students, because tuition using African indigenous knowledge systems pedagogy enables the decolonisation of knowledge processes by building knowledge that is more relevant and connected to students’ own lives, realities, histories, and stories (Olaopa & Ayodele, Citation2022) and socio-cultural, political, and economic implications (EdTech Hub, Citation2023). African indigenous knowledge systems have distinctive qualities that can support and promote the process of openness for the sharing of African indigenous knowledge and improving the growth of open educational resources (Mbah et al., Citation2021). Sharing and creating traditional knowledge using the technologies of openly shared educational resources of the 21st century harness the collaborative spirit of today and the development of relevant educational approaches (EdTech Hub, Citation2023). In terms of the research findings of the study and the relevant literature, it can be claimed that the integration of indigenous knowledge in the development of contextualised OER has the capability of decolonising e-learning content and provides opportunities to enhance open access and collaborative tuition.

Transformative learning systems

If academics are innovative, the transformation of teaching and learning can be through the appropriation of OER. Technological innovation systems are conceptualised as “a set of networks of actors and institutions that jointly interact in a specific technological field and contribute to the generation, diffusion and use of variants of a new technology or a new product” (Carroll et al., Citation2002). Globally, the method of developing ICT for educational systems is seen as one of the active approaches to creating an ingenious strategy for the management of tuition and the modernisation of educational processes (Mezirow, Citation1997). Furthermore, for the creation of online and virtual courses and remote learning technologies for courses, there is a need for a generation of highly skilled professionals in the development of digital technologies. As academics decolonise e-learning content, there is a necessity for the concurrent development of IT systems suitable for their needs.

In addition to the newly developed applications and systems, academics recommended robotic technologies for information processing and storage. This is consistent with the research findings and the existing literature, which opine that instructors should support the active and successful use of the Internet and AI by students to foster innovative thinking among students and to raise the standard of instruction (Rodríguez-Abitia & Bribiesca-Correa, Citation2021). Furthermore, AI is found to be relevant to closing gaps, such as access inequities and academic means of production and decolonial practices in data empowerment (Reddyhoff, Citation2022). Incongruent empirical findings and literature have led to the articulation of the following proposition. Transformative IT systems for the decolonisation of e-learning content can be transformed through system development and application of artificial intelligence suitable for the context.

Appropriation of ICT

Although there are several different types of emerging digital platforms, the study was interested in three platforms that are used mainly at UNISA, i.e., learning management systems (LMS), MOOC platform, and learning experience platforms (LEP). LMS serves the dual purpose of offering a learning platform for students, as well as assistance with course management for administrators and academics (Mncube et al., Citation2017). In addition to lectures presented as brief videos, the majority of MOOC platforms feature formative quizzes, automatic assessments, peer or self-assessment, and an online forum for peer help and debate (Heil & Ifenthaler, Citation2023). The learning experience platforms (LEP), on the other hand, integrate social media and allow students to communicate with academics and their peers, thereby adding to “a social media-style stream of information” and producing content (Cockrill, Citation2021). One of the main reasons is that social networks can create social relationships for educational purposes and can attract the interest of academics and students (Papademetriou et al., Citation2022).

Concerning decolonisation of e-learning content, the implementation of pedagogical scenarios relies on educational resources developed by experts, academics or educators and consumed by educators and students (Gillet et al., Citation2022). If they are not carefully developed, they can contribute to unethical behaviour and social exclusion, because their nature is less social than that designed for digital spaces (Mncube & Mthethwa, Citation2022). This is confirmed by Ng (Citation2022) who indicates that the appropriation of e-learning should cater for the on-line blended learning mode, which promotes cognitive and social learning support via simulation, collaboration, group facilitation, and self-directed learning. Therefore, the study can conclude that digital platforms play a significant role in the decolonisation of e-learning content, the transformation of tuition and showcasing the OER knowledge produced for public use.

Conclusions and recommendations

This study sought to establish how OER can contribute to the decolonisation of e-learning content. Through the proposed decolonisation of concepts from e-learning content, the study found that OER has a positive impact on the decolonisation of e-learning content. Additionally, the study proposed a possible model for the decolonisation of e-learning. The proposed model can be applicable nationally and beyond the South African context. This model will provide solutions to higher education institutions, academics, teachers, course developers, curriculum instructors, and other stakeholders interested in decolonisation of general learning or e-learning content.

The study proposes the future use of the newly developed model to design content in fields such as computer sciences, information systems, computer engineering and any other fields. This will be done to test the capabilities of the “decolonisation model” in the actual development of systems and platforms, rather than the development of e-learning content. For further recommendations, the study poses a challenge to African or global scholars to explore the decolonisation of the e-learning model, which consists of five interlinking concepts found to be useful in the decolonisation process. Academia, students, and any other researchers may apply this model in their particular context and criticise or strengthen it according to their needs.

Notes on contributor

Siphamandla Mncube is a senior lecturer in the Department of Information Science at the University of South Africa (UNISA). He holds a PhD in Information Systems (University of Cape Town); a Masters in Information Science (University of South Africa); Bachelor’s and Honours in Information Science (University of Zululand). His research niche areas lie in ICT4D, Information Systems, Information Science, Open educational resources, Open Access, Adoption of technology models, Domestication Theory, Grounded theory, Web technologies, Internet of things, artificial intelligence, Virtual learning, Open distance e-learning. He supervises masters and doctoral students in the field of Library and Information Science on ICT-related research topics.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Data availability

The data is kept in the institutional repository and available upon request.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Akhmedov, B. A. (2023). Improvement of the digital economy and its importance in higher education in the Tashkent region. Uzbek Scholar Journal, 12, 18–21.

- Al-Azab, M., Utsumi, T., & ElNashar, G. (2022). The 4th IR and AI skills required for business, industry, and daily life via education. International Journal of Internet Education, 21(1), 40.

- Anchin, J. C. (2008). Contextualizing discourse on a philosophy of science for psychotherapy integration. Journal of Psychotherapy Integration, 18(1), 1. https://doi.org/10.1037/1053-0479.18.1.1

- Baloyi, M. E. (2024). Who must lead decoloniality: A practical theological interrogation on the possible qualification to lead decolonisation: A South African study. Phronimon. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.25159/2413-3086/13880

- Bordoloi, R., Das, P., & Das, K. (2021). Perception towards online/blended learning at the time of Covid-19 pandemic: An academic analytics in the Indian context. Asian Association of Open Universities Journal, 16(1), 41–60. https://doi.org/10.1108/AAOUJ-09-2020-0079

- Bradshaw, E. D., & McDonald, J. K. (2023). Informal practices of localizing open educational resources in Ghana. International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning, 24(2), 18–36. https://doi.org/10.19173/irrodl.v24i2.7102

- Carroll, J., Howard, S., Peck, J., & Murphy, J. (2002). A field study of perceptions and use of mobile telephones by 16 to 22 year olds. The Journal of Information Technology Theory and Application, 4(2), 49–61. http://aisel.aisnet.org/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1178&context=jitta

- Chen, W., Zhang, S., Kong, D., Zou, T., Zhang, Y., & Cheshmehzangi, A. (2023). Spatio-temporal evolution and influencing factors of China’s ICT service industry. Scientific Reports, 13(1), 1–13.

- Cockrill, A, (2021). From learning management systems to learning experience platforms: Do they keep what they promise? Reflections on a rapidly changing learning environment. Cardiff Metropolitan University.

- Coffey, A., & Atkinson, P. (1996). Making sense of data: Complementary research strategy. SAGE.

- Dejica, D., Muñoz, O. G., Șimon, S., Fărcașiu, M., & Kilyeni, A. (2022). The status of training programs for E2R validators and facilitators in Europe. CoMe Book Series–Studies on Communication and Linguistic and Cultural Mediation. Scuola Superiore per Mediatori Linguistici di Pisa, Italy. Esedra.

- Creswell, J. W., & Poth, C. N. (2016). Qualitative inquiry and research design: Choosing among five approaches. SAGE.

- De Hart, K., Chetty, Y., & Archer, E. (2015). Uptake of OER by staff in distance education in South Africa. The International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning, 16(2), 18–45.

- Dreyer, J. (2018). The impact of using geography open education resources (OER) to capacitate Natural Science teachers teaching the earth and beyond strand in South African schools. Alternation Journal, 21, 159–184. https://journals.ukzn.ac.za/index.php/soa/article/view/1263

- Duara, P. (Ed.). (2004). Introduction: The decolonization of Asia and Africa in the twentieth century. In Decolonization: Perspectives from now and then (pp. 1–18). Routledge.

- EdTech Hub. (2023). Decolonising Open Educational Resources (OER): Why the focus on ‘open’ and ‘access’ is not enough for the EdTech revolution. Retrieved: https://opendeved.net/2022/04/08/decolonising-open-educational-resources-oer-why-the-focus-on-open-and-access-is-not-enough-for-the-edtech-revolution/?utm_source=rss&utm_medium=rss&utm_campaign=decolonising-open-educational-resources-oer-why-the-focus-on-open-and-access-is-not-enough-for-the-edtech-revolution

- Fanon, F. (1963). The wretched of the earth. Grove Press.

- Fataar, A. (2018). Decolonising education in South Africa: Perspectives and debates. Educational Research for Social Change, 7(SPE), vi–ix.

- García-Peñalvo, F. J. (2020). Learning analytics as a breakthrough in educational improvement. In D. Burgos (Ed.), Radical solutions and learning analytics: Personalised learning and teaching through big data (pp. 1–15). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-15-4526-9_1

- García-Peñalvo, F. J. (2021). Digital transformation in the universities: Implications of the COVID-19 pandemic. Education in the Knowledge Society, 22, e25465. https://doi.org/10.14201/eks.25465

- Gillet, D., Vonèche-Cardia, I., Farah, J. C., Hoang, K. L. P., & Rodríguez-Triana, M. J. (2022). Integrated model for comprehensive digital education platforms. In 2022 IEEE Global Engineering Education Conference (EDUCON) (pp. 1587–1593). IEEE. https://doi.org/10.1109/EDUCON52537.2022.9766795

- Golovianko, M., Terziyan, V., Branytskyi, V., & Malyk, D. (2023). Industry 4.0 vs. industry 5.0: Co-existence, transition, or a hybrid. Procedia Computer Science, 217, 102–113. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.procs.2022.12.206

- Grimaldi, P. J., Basu Mallick, D., Waters, A. E., & Baraniuk, R. G. (2019). Do open educational resources improve student learning? Implications of the access hypothesis. PloS One, 14(3), e0212508. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0212508

- Gulikers, J. T. M., Bastiaens, T. J., Kirschner, P. A., & Kester. L. (2008). Authenticity is in the eye of the beholder: Student and teacher perceptions of assessment authenticity. Journal of Vocational Education and Training, 60(4), 401–412. https://doi.org/10.1080/13636820802591830

- Gumbo, M. T., Knaus, C. B., & Gasa, V. G. (2024). Decolonising the African doctorate: Transforming the foundations of knowledge. Higher Education. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-024-01185-2

- Hayhoe R., & Pan J. (2016). East-West dialogue in knowledge and higher education. Routledge.

- Heil, J., & Ifenthaler, D. (2023). Online assessment in higher education: A systematic review. Online Learning, 27(1), 187–218. https://doi.org/10.24059/olj.v27i1.3398

- Heleta, S., & Chasi, S. (2024). Curriculum decolonization and internationalization: A critical perspective from South Africa. Journal of International Students, 14(2), 75–90. https://doi.org/10.32674/jis.v14i2.6383

- Hodgkinson-Williams, C. A., & Trotter, H. (2018). A social justice framework for understanding open educational resources and practices in the global south. Journal of Learning for Development-JL4D, 5(3), 204–224. https://doi.org/10.56059/jl4d.v5i3.312

- Jansen, J. (Ed.). (2019). Decolonisation in universities: The politics of knowledge. Wits University Press.

- Jensen, T. B., & Aanestad, M. (2007). How healthcare professionals ‘make sense’ of an electronic patient record adoption. Information Systems Management, 24, 29–43. https://doi.org/10.1080/10580530601036794

- Makgoba, M. W. (1997). Mokoko: The Makgoba affair – a reflection on transformation. Vivlia.

- Mampane, R. M., Omidire, M. F., & Aluko, F. R. (2018). Decolonising higher education in Africa: Arriving at a global solution. South African Journal of Education, 38(4), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.15700/saje.v38n4a1636

- Masavah, V. M., van der Merwe, R., & van Biljon, J. (2024). The role of open government data and information and communication technology in meeting the employment-related information needs of unemployed South African youth. The Electronic Journal of Information Systems in Developing Countries, 90(1), e12292. https://doi.org/10.1002/isd2.12292

- Matsilele, T., Msimanga, M. J., Tshuma, L., & Jamil, S. (2024). Reporting on science in the Southern African context: Exploring influences on journalistic practice. Journal of Asian and African Studies. https://doi.org/10.1177/00219096231224668

- Mbah, M., Johnson, A. T., & Chipindi, F. M. (2021). Institutionalizing the intangible through research and engagement: Indigenous knowledge and higher education for sustainable development in Zambia. International Journal of Educational Development, 82, 102355. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijedudev.2021.102355

- Mezirow, J. (1997). Transformative learning: Theory to practice. New Directions for Adult and Continuing Education, 74, 5–12. https://doi.org/10.1002/ace.7401

- Mncube, L. S., & Mthethwa, L. C. (2022). Potential ethical problems in the creation of open educational resources through virtual spaces in academia. Heliyon, 8(6), e09623. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2022.e09623

- Mncube, L. S., Dube, L., & Ngulube, P. (2017). The role of lecturers and university administrators in promoting new e-learning initiatives. International Journal of Virtual and Personal Learning Environments (IJVPLE), 7(1), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.4018/IJVPLE.2017010101

- Mncube, L. S., Tanner, M., & Chigona, W. (2021). The contribution of information and communication technology to social inclusion and exclusion during the appropriation of open educational resources. International Journal of Higher Education, 10(6), 245–258. https://doi.org/10.5430/ijhe.v10n6p245

- Mncube, S., Tanner, M. C., & Chigona, W. (2022). Reconceptualisation of domestication theory through the domestication of open educational resources. In Proceedings Annual Workshop of the AIS Special Interest Group for ICT in Global Development. https://aisel.aisnet.org/globdev2022

- Mncube, S., Tanner, M., Chigona, W., & Makoe, M. (2023). Guidelines for the development of open educational resources at a higher education institution through the lens of domestication. In J. Olivier & F. Baroud (Eds.), Open educational resources and open pedagogy in Lebanon and South Africa (pp. 129–159). Axiom Academic Publishers.

- Moeke-Pickering, T. M. (2010). Decolonisation as a social change framework and its impact on the development of indigenous-based curricula for helping professionals in mainstream tertiary education organisations [Doctoral dissertation]. University of Waikato.

- Motaung, L. B. (2024). Translanguaging pedagogical practice in a tutorial programme at a South African university. International Journal of Language Studies, 18(1), 1–12.

- Mudavanhu, S. L., Mpofu, S., & Batisai, K. (Eds.). (2024). Decolonising media and communication studies education in Sub-Saharan Africa (1st ed.). Routledge.

- Nansubuga, F., Ariapa, M., Baluku, M., & Kim, H. (2024). Approaches to assessment of twenty-first century skills in East Africa. In E. Care, M. Giacomazzi, & J. Kabutha Mugo (Eds.), The contextualisation of 21st century skills: Assessment in East Africa (pp. 99–116). Springer International Publishing.

- Nascimbeni, F., Burgos, D., Spina, E., & Simonette, M. J. (2021). Patterns for higher education international cooperation fostered by open educational resources. Innovations in Education and Teaching International, 58(3), 361–371. https://doi.org/10.1080/14703297.2020.1733045

- Ndlovu-Gatsheni, S. J. (2021). The cognitive empire, politics of knowledge and African intellectual productions: Reflections on struggles for epistemic freedom and resurgence of decolonisation in the twenty-first century. Third World Quarterly, 42(5), 882–901. https://doi.org/10.1080/01436597.2020.1775487

- Ng, D. T. K. (2022). Online aviation learning experience during the COVID-19 pandemic in Hong Kong and Mainland China. British Journal of Educational Technology, 53(3), 443–474. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjet.13185

- Nwokocha, G. C., & Legg-Jack, D. (2024). Reimagining STEM education in South Africa: Leveraging indigenous knowledge systems through the M-know model for curriculum enhancement. International Journal of Social Science Research and Review, 7(2), 173–189. https://doi.org/10.47814/ijssrr.v7i2.1951

- Oguamanam, C. (2022). Transition to the fourth industrial revolution: Africa's science, technology and innovation framework and indigenous knowledge systems. African Journal of Legal Studies, 15(1), 1–37. https://doi.org/10.1163/17087384-bja10058

- Olaopa, O. R., & Ayodele, O. A. (2022). Building on the strengths of African indigenous knowledge and innovation (AIK&I) for sustainable development in Africa. African Journal of Science, Technology, Innovation and Development, 14(5), 1313–1326. https://doi.org/10.1080/20421338.2021.1950111

- Olivier, J. (2020). Self-directed open educational practices for a decolonized South African curriculum: A process of localization for learning. Journal of E-Learning and Knowledge Society, 16(4), 20–28.

- Olivier, J., du Toit-Brits, C., Bunt, B. J., Dhakulkar, A., Terblanché-Greeff, A., Claassen, A., & Coetser, Y. M. (2022). Contextualised open educational practices: Towards student agency and self-directed learning. AOSIS.

- Oyedemi, T. D. (2021). Postcolonial casualties: ‘Born-frees’ and decolonisation in South Africa. Journal of Contemporary African Studies, 39(2), 214–229. https://doi.org/10.1080/02589001.2020.1864305

- Oyedoyin, M., Sanusi, I. T., & Ayanwale, M. A. (2024). Young children’s conceptions of computing in an African setting. Computer Science Education, 1–36. https://doi.org/10.1080/08993408.2024.2314397

- Papademetriou, C., Anastasiadou, S., Konteos, G., & Papalexandris, S. (2022). COVID-19 pandemic: The impact of the social media technology on higher education. Education Sciences, 12(4), 261. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci12040261

- Radović, S., Firssova, O., Hummel, H. G., & Vermeulen, M. (2021). Strengthening the ties between theory and practice in higher education: An investigation into different levels of authenticity and processes of re-and de-contextualisation. Studies in Higher Education, 46(12), 2710–2725. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2020.1767053

- Rangan, H. (2022). Decolonisation, knowledge production, and interests in liberal higher education. Geographical Research, 60(1), 59–70. https://doi.org/10.1111/1745-5871.12510

- Reddyhoff, D. (2022). Dependency, data and decolonisation: A framework for decolonial thinking in collaborative AI research. arXiv preprint arXiv:2206.03212. https://arxiv.org/abs/2206.03212

- Rodríguez-Abitia, G., & Bribiesca-Correa, G. (2021). Assessing digital transformation in universities. Future Internet, 13(2), 52. https://doi.org/10.3390/fi13020052

- Rumajogee, A. (2002). Distance education and open learning in sub-Saharan Africa: A literature survey on policy and practice. Association for the Development of Education in Africa.

- Sadiki, L., & Steyn, F. (2022). Decolonising the criminology curriculum in South Africa: Views and experiences of lecturers and postgraduate students. Transformation in Higher Education, 7, 150. https://doi.org/10.4102/the.v7i0.150

- Shai, K. B. (2023). An Afrocentric critique of South Africa’s contemporary knowledge production regime. EUREKA: Social and Humanities, 1, 72–80. https://doi.org/10.21303/2504-5571.2023.002542

- Shokane, A. L., & Masoga, M. A. (2023). Indigenous knowledge and social work crossing the paths for intervention. In D. Hölscher, R. Hugman, & D. McAuliffe (Eds.), Social work theory and ethics. Social Work (pp. 251–265). Springer, Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-19-1015-9_14

- Thabede, D. (2014). The African worldview as the basis of practice in the helping professions. Social Work/Maatskaplike Werk, 44(3), 233–244. https://doi.org/10.15270/44-3-237

- Tompkins, Z., Herman, C., & Ramage, M. (2024). Perspectives of distance learning students on how to transform their computing curriculum: “Is there anything to be decolonised?” Education Sciences, 14(2), 149. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci14020149

- Trochim, W., Donnelly, J. P., & Arora, K. (2015). Research methods: The essential knowledge base. Cengage.

- UNESCO. (2002). Forum on the impact of Open Courseware for higher education in developing countries: Final report. http://unesdoc.UNESCO.org/images/0012/001285/128515e.pdf

- UNISA. (2011). Makhanya, M.S and LenkaBula, P.: Inauguration and Investiture Speech. African intellectuals, knowledge systems and Africa’s futures’. Retrieved: https://www.unisa.ac.za/sites/corporate/default/News-&-Media/Articles/Regaining-consciousness-of-Africa%27s-intellectual-futures

- UNISA. (2016). Policy on research ethics. UNISA_Ethics_Policy.pdf

- UNISA. (2019). UNISA integrated report 2019. https://www.UNISA.ac.za/sites/corporate/default/

- UNISA. (2022). UNISA’s definition of CODeL. Policy - Open Distance e-Learning - rev appr Exco of Council - 10.12.2018.pdf (unisa.ac.za)

- Van der Westhuizen, M., & Greuel, T. (2017). Are we hearing the voices? Africanisation as part of community development. HTS: Theological Studies, 73(3), 1–9.

- Wanjiku Wang’ang’a, A. (2024). Consequences of artificial intelligence on teaching and learning in higher education in Kenya: Literature review. East African Journal of Education Studies, 7(1), 202–215. https://doi.org/10.37284/eajes.7.1.1718

- Warbrick, I., Heke, D., & Breed, M. (2023). Indigenous knowledge and the microbiome—Bridging the disconnect between colonized places, peoples, and the unseen influences that shape our health and well-being. Msystems, 8(1), e00875-22. https://doi.org/10.1128/msystems.00875-22

- Wimpenny, K., Nascimbeni, F., Affouneh, S., Almakari, A., Maya Jariego, I., & Eldeib, A. (2022). Using open education practices across the Mediterranean for intercultural curriculum development in higher education. Teaching in Higher Education, 27(1), 54–69. https://doi.org/10.1080/13562517.2019.1696298

- Zhang, R., Zou, D., & Cheng, G. (2023). A review of chatbot-assisted learning: Pedagogical approaches, implementations, factors leading to effectiveness, theories, and future directions. Interactive Learning Environments. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1080/10494820.2023.2202704

- Zurba, M., & Papadopoulos, A. (2023). Indigenous participation and the incorporation of indigenous knowledge and perspectives in global environmental governance forums: A systematic review. Environmental Management, 72(1), 84–99. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00267-021-01566-8