Abstract

This study analyses changes in students’ perceptions of online examinations during the transition from a face-to-face to a fully online assessment system. We compare data from a survey administered to two samples of students at a distance learning university at the end of two consecutive academic years in which a new online examination system was introduced. The survey focused on students’ experiences and opinions of online examinations and the digital requirements associated with them. Analyses of variance were conducted on the data from the two student samples, finding significant evidence of changes in students’ perceptions as they became more familiar with online examinations. The results suggest that familiarity with digital tools positively influences preference for online over face-to-face exams, as well as positive perceptions of the procedures associated with online exams, particularly webcam proctoring and the use of a digital interface to answer exam questions.

Introduction

Digital assessment methods in higher education is a broad field that has been analyzed from many approaches. The expansion of distance education in its various forms has widened the methodological options for assessing students at a distance and has multiplied the development of pilot studies of digitized examinations and assessment activities. According to recent systematic reviews of research on digital assessment in higher education, analyses from the student perspective have focused on key issues, such as preference for online vs. paper-based exams, time required to complete online exams, potential for cheating, and technological barriers (Butler-Henderson & Crawford, Citation2020; Conrad & Witthaus, Citation2021; Muzaffar et al., Citation2021). To further explore this topic, this paper aims to analyze students’ perceptions by exploring variation as uncertainty about assessment procedures and tools decreases. This may provide more accurate knowledge about students’ views on the processes of implementing online assessment systems.

Literature review

Familiarity with a digital system refers to the degree of recognition and natural interaction that users have with the components of that system. Familiarity is directly related to experience with the system and is a critical factor in the usability of a given technology, but it can also influence users’ perceptions of the technology (Casaló et al., Citation2008). The influence of technology familiarity and self-efficacy on students’ perceptions and use of digital tools is a topic that has been addressed from a variety of approaches and contexts. For example, Shin and Kang (Citation2015) analyzed the acceptance of a mobile learning management system in an online university and its impact on student satisfaction and performance. The results showed that students began to accept the new mobile technology, which had a direct and indirect impact on their academic performance. Lazar et al. (Citation2020) developed and validated a scale to measure digital technology adoption in the context of blended learning in higher education. This scale included the external two-dimensional factor of familiarity with digital tools, making the instrument an appropriate way to assess students’ perceived familiarity and usefulness with digital tools. In another study, Han and Yi (Citation2018) examined the relationship between smartphone use and academic performance among university students and found that greater familiarity with mobile phone-mediated communication improved self-efficacy and positively influenced students’ intention to use smartphones for academic purposes. Lee et al. (Citation2019) conducted a study on high school students’ perceptions of technology use in the classroom and found that although students had positive attitudes and self-efficacy to use technology, their actual use in the classroom was limited and did not correlate with perceived usefulness. Finally, there is another group of studies that focus on perceptions of digital learning spaces and deepen the analysis of various factors, such as learner adaptation to features, external variables, such as confidence (Abdullah & Ward, Citation2016; Deepamala & Shivraj, Citation2019), readiness (Benson, Citation2019; Joosten & Cusatis, Citation2020; Martin et al., Citation2020; Šumak et al., Citation2011) and, to a lesser extent, familiarity (Lazar et al., Citation2020).

The literature suggests that familiarity with digital tools has a positive effect on students’ intentions and use. However, few studies have analyzed students’ familiarity and self-efficacy with technology and their relationship with online exams (Kitmitto et al., Citation2018). Previous research on familiarity and online exams has focused on pointing out unfamiliarity with digital devices as the main threat to question the validity and fairness of online assessment systems. When looking more closely at the factor of familiarity with online examinations and its relationship with academic performance, it has been suggested that the importance lies in how students have been used and what kind of experiences they have had, rather than in the simple use of online examination systems (Laurillard, Citation2002; Papanastasiou et al., Citation2003). On the other hand, more recent work has found no evidence that technological accessibility or students’ familiarity with digital devices is a determining factor in performing well in online exams (Kitmitto et al., Citation2018; Soto Rodríguez et al., Citation2021; Zhang et al., Citation2016).

Regarding students’ perceptions and online examinations, this is a topic of increasing interest as digital assessment becomes more prominent (Afacan Adanır et al., Citation2020; Böhmer et al., Citation2018; Domínguez Figaredo et al., Citation2022; Ilgaz & Adanır, Citation2020; Matthíasdóttir & Arnalds, Citation2016; Pagram et al., Citation2018; Rios & Liu, Citation2017). The literature shows that students’ perceptions of the elements and situations specific to online examinations are generally positive. Students are satisfied with the digital version of the exam, the appropriateness of the questions, the quasi-automatic feedback they provide, and the logistical facilities, while they are more concerned about the possibility of cheating, technical glitches, lack of time, and the ability to enter mathematical calculations (Backman, Citation2019; Böhmer et al., Citation2018; Elmehdi & Ibrahem, Citation2019; Ilgaz & Adanır, Citation2020). Most of these challenges expressed by students have been overcome with the latest technological developments in online examination software. The most sensitive case is the issue of cheating, which has received much attention (Bawarith et al., Citation2017; D'Souza & Siegfeldt, Citation2017; Gokulkumari et al., Citation2022; Kocdar et al., Citation2018; Kolhar et al., Citation2018; Krienert et al., Citation2022), and a consensus has been reached to ensure integrity by using software that prevents access to the internet, various forms of monitoring students while they are taking the exam, time limits for answering, and combining questions to create different versions of the exam (Backman, Citation2019).

Within a certain methodological diversity—Van der Kleij and Lipnevich’s (2021) literature review mentions surveys, interviews, focus groups, open-ended written questions, experimental manipulations, and observations as preferred methods in studies of students’ perceptions—it is common for perceptual analyses to focus on the dual nature of direct and indirect factors of perception. For example, Roscoe et al. (Citation2017) analyzed the influence of students’ perceptions of automated writing assessment on aspects, such as their writing performance and revision behavior, for which they considered both indirectly collected feedback and students’ direct experience with the software. In the case of online exams, indirect factors influencing students’ perceptions would be interfaces (Hasan & Ahmed, Citation2007; Karim & Shukur, Citation2016) and other indirect, non-specifically academic variables of the exams, such as the time spent, the context in which the exams are taken, or the opportunities for cheating (Butler-Henderson & Crawford, Citation2020). While direct factors are preferentially analyzed through behavioral analysis in digital academic spaces (Greiff et al., Citation2016; Rienties & Toetenel, Citation2016), contrasting academic performance (Cakiroglu et al., Citation2017; Ćukušić et al., Citation2014; Domínguez Figaredo et al., Citation2022), and questionnaires with direct questions (Budge, Citation2011; Kitmitto et al., Citation2018; Muzaffar et al., Citation2021).

Despite a variety of studies and research approaches on related topics, the literature shows that there is insufficient evidence on the evolution of students’ perceptions of online examinations over time or during the implementation cycle of online examinations from a paper-based modality. The usual approaches are based on the influence of aspects of online exams on students’ preferences contextualized at a particular point in time, but few studies focus on the evolutionary aspect and how familiarity and learning curve with online exams influence perceptions. The current study aims to provide evidence in this area by analyzing the evolution of students’ perceptions during the transition process of a university that rapidly migrated from a paper-based to a fully online final examination system during the COVID-19 pandemic. Specifically, the two variables involved—familiarity and perception—are examined from a dual perspective, direct and indirect, considering both the projection of students’ opinions and direct data on their behavior and actual experience with online and paper-based exams.

The analysis was organized to answer the following research questions (RQ):

RQ1: Does familiarity with digital assessment influence students’ preference for online exams?

RQ2: Does familiarity with digital assessment influence students’ perceptions of the specific requirements of online exams?

Methods

Research approach and variables

The purpose of this study is to better understand the possible influence of familiarity and self-efficacy with digital assessment systems on students’ perceptions of online exams. The research design focuses on analyzing how increased familiarity with online examination systems (VI) influences students’ perception of and preference for this type of online assessment (VD).

With these premises, the research analyzed changes in preferences and perceptions of online examinations in two different groups of undergraduate students (GA, GB, that are explained later in the paper under Participants subsection) at a large distance learning university [Universidad Nacional de Educación a Distancia (UNED), Spain] using a novel online assessment system. The university changed the final examination system from face-to-face—the usual method at this university—to a fully online format—never used before—during the COVID crisis. The new online system was supported by a proctored examination platform developed by the university’s technical services. This platform enabled secure and monitored online examinations, with features, such as remote proctoring via webcam, automated identity verification, and real-time monitoring to detect and prevent academic dishonesty. The system also facilitated the secure submission of exams and provided tools for managing different types of assessments, including multiple choice, short answer, and essay questions. As a distance university, students and teachers have access to online learning, and the university provides support for the use of newly introduced digital tools, which ensures the availability of technological infrastructure and digital skills to use the system.

The two groups of students completed an online survey to obtain contextual data and to determine their perceptions of key aspects of the online examination process. Participation was voluntary and students accessed the survey through an invitation sent via university communication channels. The survey was anonymous, and respondents consented to use the results for research purposes. The University’s Research Ethics Committee does not require an ethics approval report if the study does not affect fundamental rights and only non-identifying personal data are used, as it was the case. Before administering the survey, a content validation process was conducted by consulting with subject matter experts who reviewed the survey to ensure that it accurately measured the intended variables and was free of bias and ambiguity. The survey included closed-ended questions, Likert-type questions, and an open-ended question for additional observations that students wished to express (see Appendix for a detailed description). From an analytical approach, the items were grouped into a set of variables that addressed the research questions and complemented the dependent variable. These variables are described below, and lists the corresponding questionnaire items:

VD1 is related to “familiarity” and consists of two items asking students about the number of years they have been enrolled at the university—i.e., the more years at the university the more experience with face-to-face exams and vice versa—and about previous experience with online exams. Experience with online exams is expected to be significantly higher in GB than in GA, as students had already practised with online exams at university at the time of the second survey.

VD2 corresponds to students’ “indirect perception” of online exams. It is a set of Likert-type items asking about the difficulty of online vs. face-to-face exams, the proctoring system, and the usability of the interface. According to the focus of the items, a lower response score indicates a more positive perception of online exams. The reliability of the scale was based on the larger sample of GB and the resulting Cronbach Alpha value was estimated at 0.57, which is considered acceptable for a non-standardised design with <10 items (Loewenthal & Lewis, Citation2001).

VD3 refers to the “direct perception” of online examinations and consists of a question about students’ preference for face-to-face or online examinations.

Table 1. Grouping of survey items and research dependent variables.

Participants

The two groups of students responded to the survey at two different times, one year apart, during the university’s implementation of the new online assessment system:

The first sample of students (GA) responded to the survey in July 2020, at the end of the first final examination period supported by the new online system. The final sample of GA was n = 714 (Age Mean = 37.2; Std. Dev. = 10.2).

The second sample (GB) was surveyed one year later, in July 2021, immediately after taking the online exams in the same call as GA, but in the following academic year. By this time, the online exams had been administered in four previous calls—according to the university assessment calendar, in June 2020, September 2020, February 2021, and June 2021—so students in GB had the opportunity to practice with the system. The final sample from GB was n = 6660 (Age Mean = 37.3; Std. Dev. = 11.0).

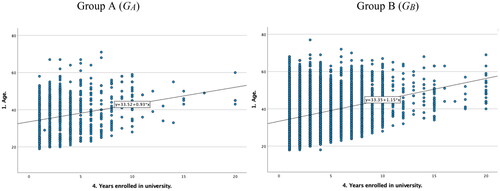

The two samples refer to slightly different student populations. The GA corresponds to students enrolled in undergraduate courses in 2020 and the GB corresponds to students enrolled in the same courses in 2021. The university has only one enrolment window at the beginning of the academic year, which ends in October. Exogenous factors, such as stoppages and closures during the year represented by GB led to a significant increase in enrolments in that academic year: from 126,653 students in 2020 to 140,508 in 2021 (source: University Data Centre). In general, enrolments at distance learning universities increase during periods of economic downturn as students—many of whom are unemployed and of working age—seek to upgrade their skills at university. In addition, the pandemic conditions led to a slight decline in enrolments at residential universities in favor of distance universities (UNESCO, Citation2021). This meant that the cohort of new entrants in 2021 included more students with a profile typical of face-to-face universities, entering directly from Secondary Education. shows the impact of these circumstances in the two study samples, such that the relationship between younger age and fewer years at university is stronger in GB (R2 Linear = 0.09) than in GA (R2 Linear = 0.07).

Analysis and results

Research question 1: Does familiarity with digital assessment influence students’ preference for online exams?

To answer RQ1, the relationships between VD3—related to exam type preference—and VD1—related to familiarity—were statistically analyzed, looking for some significance in the variances of the data collected.

First, a Kruskal-Wallis test was performed to compare the data on students’ years at university (Item 4. Years at university) and their preference for online or face-to-face exams (Item 19. Preferred exam method). The aim was to find out whether the distribution of years enrolled at university was the same across the categories of preferred examination method. The two groups of students were tested and only in GB were there significant differences (p < 0.000; α = 0.05). This significance in the GB suggests that students’ years at university are a factor influencing their preferences for exam types, and it is consistent with the composition of the sample, which contained a greater number of newly enrolled students and therefore fewer years of experience at the university. Thus, students who had been at university longer showed different preferences compared to newer students.

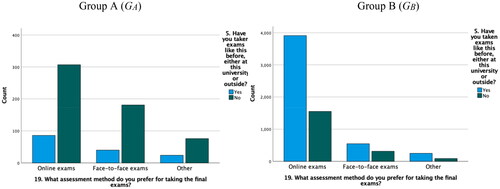

In addition, pairwise comparison was used to determine which specific groups differed from each other. In this study, pairwise comparisons revealed that students who chose the options “other” (p < .001) and “face-to-face” (p < .000) had been enrolled at university for more years than those who chose online exams (see ). These comparisons indicate that students who preferred face-to-face or other types of exams had significantly more years at university than those who preferred online exams. The large negative test statistic for the comparisons between “online exams” and “face-to-face exams” (−845.144) and “online exams” and “other” (−593.969) suggests a strong difference in preference based on years at university. And the significant p-values (<0.001) confirm that this difference is statistically significant.

Table 2. Pairwise comparisons of the preferred exam type for the final evaluation (GB).

To complete the analysis of RQ1, comparisons of the familiarity variable (VD1) related to previous experience with online exams (Item 5. Experience with online exams) and the perception variable (VD3) related to exam type preference (Item 19. Preferred exam method) were calculated using a Chi-Square test, with the target level of statistical significance set at <5% (p < 0.05). The test was performed on the two groups, resulting in a favorable level of significance only in GB (p < 0.001).

The results of the Chi-Square test were supplemented with a breakdown of the variation in the differences between the two samples. illustrates the relationship between students’ previous experience with online exams and their preferred exam type for both groups (GA and GB). The figure shows that in both groups, students with previous experience of online exams are more likely to prefer online exams to face-to-face exams. This trend is more pronounced in GB, where students had an additional year of practice with the online assessment system. Thus, the data in shows how increased familiarity with online exams correlates with an increased preference for this mode of assessment, reinforcing the findings from the previous analysis.

Research question 2: Does familiarity with digital assessment influence students’ perceptions of the specific requirements of online exams?

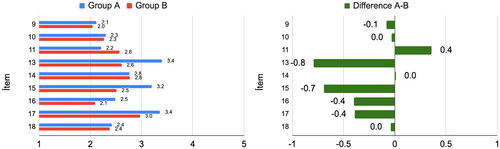

To answer RQ2, evidence was gathered using descriptive statistics. Indirect perception of online exams—measured by VD2, sub-variables 2, 3, and 4—was compared with the phenomenon of “familiarity,” which in this case is determined by contrasting the data obtained in GA—with less experience with online exams—and GB—with more experience with online exams. shows the mean scores of the responses to the Likert-type items of the variables analyzed, as well as the difference between the responses of GA and GB. The Likert-type scale ranges from 1 to 5 points, with scores below 3 indicating a better perception of online testing and scores above 3 indicating a worse perception.

Analysis of the data reveals some findings that explain how familiarity with digital assessment influences students’ perceptions of specific online exam requirements:

In general, all mean scores decrease or remain the same in GB students’ responses. This suggests that the overall perception of the conditions of online exams improves when students have had previous experience with them. There is only one case (item 11; difference = 0.4) where the mean score increases in GB compared to GA, suggesting that students with previous experience consider the time taken to complete an online exam to be less critical than a face-to-face exam.

The most significant change in trend occurs in three items where students move from a negative perception—mean score above 3—in GA to a positive perception in GB—mean score below 3. These are the perception of digital proctoring (item 13; difference = −0.8) and the perception of the digital interface when typing open-ended questions (item 15; difference = −0.7) and when writing digitally (item 17; difference = −0.4). In this sense, familiarity with online exams leads to a better consideration of webcam proctoring vs. teacher invigilation in face-to-face exams, to a more positive perception of typing vs. handwriting, and the possibility of sending handwritten answers in online exams is less relevant.

A final analysis of the comparative descriptive data refers to those mean scores associated with positive perceptions that do not vary from one group to the other. This indicates that there is a common perception—both before and after practicing with online assessment systems—about sensitive aspects of online exams, such as the convenience of checking by hand vs. clicking the answer in MCQ (item 16; difference = −0.4), the difficulty of online exams vs. face-to-face exams (item 9; difference = −0.1), the difficulty of cheating in online systems (item 10; difference = 0.0), the appropriate use of the webcam for proctoring (item 14; difference = 0.0), and the preference for the keyboard over systems, such as voice recordings for submitting questions (item 18; difference = 0.0).

Discussion

This research has parallels with other works that analyze students’ perceptions of key elements of the learning process, although we have tried to address some of the methodological limitations suggested in the literature. In the case of the online survey used in the study, it appears to be an appropriate tool for analyzing students’ perceptions. In their systematic review of research on students’ perceptions of assessment feedback, Van der Kleij and Lipnevich (Citation2021) identified the survey as the data collection tool in more than 50% of the studies. This estimate is also consistent with the view of Brown and Harris (Citation2018), who suggest that it is a common tool in research aimed at capturing participants’ attitudes, understanding, and general experiences. However, the use of surveys in this type of research is not always ideal, and cases of poor rigor have been identified, mainly due to the quality of the items, small samples, lack of validation of the instrument, and poor description of the data analysis (Van der Kleij & Lipnevich, Citation2021).

This study sought to overcome these obstacles by focusing on systematizing the research design, clearly identifying the variables involved, and combining inferential statistics based on analysis of variance—a very common method in research on students’ perceptions (Afacan Adanır et al., Citation2020; Das, Citation2007; FitzPatrick et al., Citation2011; Guillén-Gámez et al., Citation2020; Pavanelli, Citation2018; Weiss et al., Citation2016)—with a descriptive approach that leads to more precise interpretations. Most importantly, the aim was to improve the representativeness of the study by expanding the samples. Here, large samples are essential to ensure the quality of experimental studies, which is another common limitation in perceptual research (Smith & Lipnevich, Citation2018; Van der Kleij & Lipnevich, Citation2021). In the current study, a sequential group comparison was used, as opposed to the traditional procedure of a control group and random assignment. The group comparison to determine the effect of the independent variable followed a rigorous process in which the survey was administered to the two samples at the same time during the academic year, using the same selection procedure to ensure diversity of individuals and degrees. Thus, as in the highly controlled small experimental studies, the procedure allows the results to be attributed to the independent variable—as defined in each case—without compromising the ecological validity and generalizability of the results.

Regarding the findings of the study, the data obtained reinforce and nuance some of the findings of previous research on students’ perceptions of online examinations. A large body of evidence regarding students’ preference for online over paper-based examinations can be consolidated (Attia, Citation2014; Böhmer et al., Citation2018; Elmehdi & Ibrahem, Citation2019; Marius et al., Citation2016; Matthíasdóttir & Arnalds, Citation2016; Pagram et al., Citation2018; Schmidt et al., Citation2009). This study confirms the reasons given previously, such as the increased speed and ease of editing answers (Attia, Citation2014; Pagram et al., Citation2018) and the more positive, flexible, and authentic experience in the online exam environment (Matthíasdóttir & Arnalds, Citation2016; Schmidt et al., Citation2009; Williams & Wong, Citation2009). The positive acceptance of the digital space and interface used in online exams has also been confirmed, with overall positive rankings. However, the data suggests that perceptions of usability are influenced by familiarity and are not always positive when students first encounter the system. This initial learning curve can lead to resistance that gradually diminishes as students gain more experience with the system. And the opposite is true of the perceived speed of online exams: this research has shown that this opinion is somewhat a priori, and as familiarity with online exams increases, students tend to perceive that they take no less time to complete than paper versions.

The study also found that students’ perceptions of specific online exam requirements, such as webcam proctoring and digital interfaces for answering questions, improved with familiarity. This change can be attributed to a reduction in anxiety and uncertainty as students gain experience with the system. Initial concerns about the fairness and integrity of online exams, particularly in relation to cheating and technical issues, diminish as students become more familiar with the technology. This is consistent with findings from previous studies that have shown that familiarity with digital tools reduces anxiety and improves user experience (Kim et al., Citation2019; Shin & Kang, Citation2015).

Furthermore, the significant improvement in perceptions related to the digital proctoring system, the usability of the digital interface for typing open-ended questions, and digital writing, as seen in the comparative analysis between GA and GB, highlights the central role of familiarity. In particular, students’ acceptance of the webcam proctoring and digital typing interfaces shows a marked positive shift, indicating less discomfort with monitoring and more ease with digital text entry.

In response to RQ2, the results of this study suggest that students with prior experience consider the time required to complete an online exam to be less critical than a face-to-face exam. This finding can be rationalized by considering that experienced students are more efficient at navigating the digital exam interface and managing their time effectively. Familiarity with the online exam format is likely to reduce the cognitive load associated with understanding and following digital procedures, allowing students to focus more on the content of the exam itself rather than the logistics. As a result, they may find the time constraints less problematic than the initial adjustment period experienced by less familiar students. This is supported by research suggesting that familiarity with digital interfaces can lead to improved efficiency and reduced cognitive load (Paas et al., Citation2003; van Gog et al., Citation2010).

Finally, with regard to cheating, previous studies have shown that an (adjusted) majority of students perceive the online exam environment as facilitating cheating (Attia, Citation2014; Pagram et al., Citation2018). However, these studies have an important limitation in that they did not use a proctored exam tool as a reference. It has been widely demonstrated that there is a significant difference between proctored and non-proctored online exams in terms of key variables, such as academic performance, among others (Ardid et al., Citation2015; Krienert et al., Citation2022; Rios & Liu, Citation2017). Thus, in the case of this research, the reference exam tool included a cheating control system—which is a minimum standard nowadays—and mediated the different perceptions of students, who in all cases claimed that it is not easier to cheat in online exams, regardless of the familiarity variable.

Conclusions

The current study took a time perspective to analyze changes in student perceptions during the process of transitioning to an online examination system. The evidence suggests that there are significant changes in student perceptions as familiarity with the digital system used increases. In general, it is concluded that students show a clear preference for online exams over paper-based exams, a finding that is consistent with other similar research. Specific contributions of this research suggest that this preference is influenced by familiarity with online examination systems, as it is significantly more pronounced for students accustomed to taking online exams than for those accustomed to taking paper-based exams.

Familiarity also influences students’ perceptions of the procedures and requirements associated with taking online exams. In general, students perceive the requirements associated with taking online exams as positive, and familiarity is a determining factor in shifting from negative to positive perceptions of the specific processes associated with taking exams via webcam and using a digital interface to write answers.

These findings provide new insights into students’ perceptions of learning assessment using online systems. They suggest a new scenario for research by highlighting the evolving component of perception and the importance of prior experience and familiarity with digital systems as a predominant factor to be considered. Thus, these findings may be of particular interest for designing transitions from analog approaches to large-scale digital assessment systems.

In particular, it points to a changing trend in students’ perceptions of digital monitoring and surveillance systems, which, along with cheating, is one of the most sensitive elements when it comes to online examinations. The two elements are closely related, as proctored exams are justified to the extent that they help to prevent cheating. The feature of proctored systems that causes the most anxiety among students is webcam surveillance. It is therefore somewhat remarkable that this study finds that as students become more familiar with digital systems, their preference for this type of control increases over teacher monitoring in the face-to-face examination classroom.

In the same order is the preference for digital interfaces when it comes to mediating between students and the digital system supporting online exams. The literature shows that this is a sensitive issue and sometimes a barrier identified by educators. The fact that the preference for digital interfaces is shown to be conditioned by familiarity in the case of answering open-ended questions again points to the importance of properly designing the transition to digital systems to have a successful implementation and acceptance by students.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank the UNED students who replied to the survey.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

Data is available from the corresponding author upon request.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Daniel Domínguez-Figaredo

Daniel Domínguez-Figaredo is an Associate Professor in the Faculty of Education at the Universidad Nacional de Educación a Distancia-UNED, Spain. He has been a Research Scholar at the NYU Center for Responsible AI, a Visiting Research Scholar in the Department of Computer Science and Engineering at the NYU Tandon School of Engineering, and a non-resident fellow of the European Distance and E-learning Network (EDEN). His recent research analyzes the impact of digitization and automation on learning practices.

Inés Gil-Jaurena

Inés Gil-Jaurena is an Associate Professor in the Faculty of Education at the Universidad Nacional de Educación a Distancia-UNED, Spain. She is an EDEN Senior Fellow, a member of the EDEN Fellows Council Board and the Steering Committee of the EDEN Network of Academics and Professionals (EDEN NAP), and a member of the Steering Committee of the UNESCO Chair in Distance Education, based at UNED. She has served as Editor-in-Chief of Open Praxis Journal, published by the International Council for Open and Distance Education (ICDE). His recent research interests are in the areas of intercultural education, community development, and open and distance education.

References

- Abdullah, F., & Ward, R. (2016). Developing a general extended technology acceptance model for e-learning (GETAMEL) by analysing commonly used external factors. Computers in Human Behavior, 56, 238–256. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2015.11.036

- Afacan Adanır, D. G., İsmailova, A. P. D. R., Omuraliev, P. D. A., & Muhametjanova, A. P. D. G. (2020). Learners’ perceptions of online exams: A comparative study in Turkey and Kyrgyzstan. The International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning, 21(3), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.19173/irrodl.v21i3.4679

- Ardid, M., Gómez-Tejedor, J. A., Meseguer-Dueñas, J. M., Riera, J., & Vidaurre, A. (2015). Online exams for blended assessment. Study of different application methodologies. Computers & Education, 81, 296–303. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2014.10.010

- Attia, M. A. (2014). Postgraduate students’ perceptions toward online assessment: The case of the faculty of education, Umm Al-Qura university. In E. N. H. Alromi, S. Alshumrani, & A.W. Wiseman (Eds.), Education for a knowledge society in Arabian Gulf countries (Vol. 24, pp. 151–173). Emerald. https://doi.org/10.1108/S1479-367920140000024015

- Backman, J. (2019). Students’ experiences of cheating in the online exam environment [Bachelor’s thesis]. Laurea University of Applied Sciences. Open Repository Theseus. https://www.theseus.fi/bitstream/handle/10024/167963/Thesis.pdf?sequence=2&isAllowed=y

- Bawarith, R., Abdullah, D., Anas, D., & Dr, P. (2017). E-exam cheating detection system. International Journal of Advanced Computer Science and Applications, 8(4), 176–181. https://doi.org/10.14569/IJACSA.2017.080425

- Benson, T. (2019). Digital innovation evaluation: User perceptions of innovation readiness, digital confidence, innovation adoption, user experience and behaviour change. BMJ Health & Care Informatics, 26(1). Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjhci-2019-000018

- Böhmer, C., Feldmann, N., & Ibsen, M. (2018). E-exams in engineering education—Online testing of engineering competencies: Experiences and lessons learned. 2018 IEEE Global Engineering Education Conference (pp. 571–576). https://doi.org/10.1109/EDUCON.2018.8363281

- Brown, G. T. L., & Harris, L. R. (2018). Methods in feedback research. In A. Lipnevich & J. Smith (Eds.), The Cambridge handbook of instructional feedback (Cambridge handbooks in psychology) (pp. 97–120). Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781316832134.007

- Budge, K. (2011). A desire for the personal: Student perceptions of electronic feedback. International Journal of Teaching and Learning in Higher Education, 23(3), 342–349. https://www.isetl.org/ijtlhe/pdf/IJTLHE1067.pdf

- Butler-Henderson, K., & Crawford, J. (2020). A systematic review of online examinations: A pedagogical innovation for scalable authentication and integrity. Computers & Education, 159, 104024. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2020.104024

- Cakiroglu, U., Erdogdu, F., Kokoc, M., & Atabay, M. (2017). Students’ preferences in online assessment process: Influences on academic performances. Turkish Online Journal of Distance Education, 18(1), 132–132. https://doi.org/10.17718/tojde.285721

- Casaló, L., Flavián, C., & Guinalíu, M. (2008). The role of perceived usability, reputation, satisfaction and consumer familiarity on the website loyalty formation process. Computers in Human Behavior, 24(2), 325–345. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2007.01.017

- Conrad, D., & Witthaus, G. (2021). Reimagining and reexamining assessment in online learning. Distance Education, 42(2), 179–183. https://doi.org/10.1080/01587919.2021.1915117

- Ćukušić, M., Garača, Ž., & Jadrić, M. (2014). Online self-assessment and students’ success in higher education institutions. Computers & Education, 72, 100–109. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2013.10.018

- Das, G. S. (2007). Student perception of globalization: Results from a survey. Global Business Review, 8(1), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1177/097215090600800101

- Deepamala, M. A., & Shivraj, K. S. (2019). Self-perception of information literacy skills and confidence level in use of information by women faculty members: An analysis. Asian Journal of Information Science and Technology, 9(S1), 104–107. https://doi.org/10.51983/ajist-2019.9.S1.212

- Domínguez Figaredo, D., Gil Jaurena, I., & Morentin Encina, J. (2022). The impact of rapid adoption of online assessment on students’ performance and perceptions: Evidence from a distance learning university. Electronic Journal of e-Learning, 20(3), 224–241. https://doi.org/10.34190/ejel.20.3.2399

- D'Souza, K. A., & Siegfeldt, D. V. (2017). A conceptual framework for detecting cheating in online and take-home exams. Decision Sciences Journal of Innovative Education, 15(4), 370–391. https://doi.org/10.1111/dsji.12140

- Elmehdi, H. M., & Ibrahem, A. M. (2019). Online summative assessment and its impact on students’ academic performance, perception and attitude towards online exams: University of Sharjah study case. In M. Mateev & P. Poutziouris (Eds.), Creative business and social innovations for a sustainable future. Advances in science, technology & innovation (IEREK Interdisciplinary Series for Sustainable Development). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-01662-3_24

- FitzPatrick, K. A., Finn, K. E., & Campisi, J. (2011). Effect of personal response systems on student perception and academic performance in courses in a health sciences curriculum. Advances in Physiology Education, 35(3), 280–289. https://doi.org/10.1152/advan.00036.2011

- Gokulkumari, G., Al-Hussain, T., Akmal, S., & Singh, P. (2022). Analysis of e-exam practices in higher education institutions of KSA: Learners’ perspectives. Advances in Engineering Software, 173, 103195. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.advengsoft.2022.103195

- Greiff, S., Niepel, C., Scherer, R., & Martin, R. (2016). Understanding students’ performance in a computer-based assessment of complex problem solving: An analysis of behavioral data from computer-generated log files. Computers in Human Behavior, 61, 36–46. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2016.02.095

- Guillén-Gámez, F. D., Mayorga-Fernández, M. J., & Ramos, M. (2020). Examining the use self-perceived by university teachers about ICT resources: Measurement and comparative analysis in a one-way ANOVA design. Contemporary Educational Technology, 13(1), ep282. https://doi.org/10.30935/cedtech/8707

- Han, S., & Yi, Y. J. (2018). How does the smartphone usage of college students affect academic performance? Journal of Computer Assisted Learning, 35(1), 13–22. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcal.12306

- Hasan, B., & Ahmed, M. U. (2007). Effects of interface style on user perceptions and behavioral intention to use computer systems. Computers in Human Behavior, 23(6), 3025–3037. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2006.08.016

- Ilgaz, H., & Adanır, G. A. (2020). Providing online exams for online learners: Does it really matter for them? Education and Information Technologies, 25(2), 1255–1269. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-019-10020-6

- Joosten, T., & Cusatis, R. (2020). Online learning readiness. American Journal of Distance Education, 34(3), 180–193. https://doi.org/10.1080/08923647.2020.1726167

- Karim, N. A., & Shukur, Z. (2016). Proposed features of an online examination interface design and its optimal values. Computers in Human Behavior, 64, 414–422. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2016.07.013

- Kim, H. J., Hong, A. J., & Song, H. D. (2019). The roles of academic engagement and digital readiness in students’ achievements in university e-learning environments. International Journal of Educational Technology in Higher Education, 16(1). Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41239-019-0152-3

- Kitmitto, S., George, B., Park, B. J., Bertling, J., & Almonte, D. (2018). Developing new indices to measure digital technology access and familiarity. NAEP Validity Studies (NVS). https://www.air.org/sites/default/files/2021-06/Developing-New-Indices-to-Measure-Digital-Technology-Access-and-Familiarity-October-2018.pdf

- Kocdar, S., Karadeniz, A., Peytcheva-Forsyth, R., & Stoeva, V. (2018). Cheating and plagiarism in e-assessment: Students’ perspectives. Open Praxis, 10(3), 221–235. https://doi.org/10.5944/openpraxis.10.3.873

- Kolhar, M., Alameen, A., & Gharsseldien, Z. M. (2018). An online lab examination management system (OLEMS) to avoid malpractice. Science and Engineering Ethics, 24(4), 1367–1369. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11948-017-9889-z

- Krienert, J. L., Walsh, J. A., & Cannon, K. D. (2022). Changes in the tradecraft of cheating: Technological advances in academic dishonesty. College Teaching, 70(3), 309–318. https://doi.org/10.1080/87567555.2021.1940813

- Laurillard, D. (2002). Rethinking university teaching: A framework for the effective use of educational technology (2nd ed.). Routledge.

- Lazar, I. M., Panisoara, G., & Panisoara, I. O. (2020). Digital technology adoption scale in the blended learning context in higher education: Development, validation and testing of a specific tool. PLOS One, 15(7), e0235957. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0235957

- Lee, C., Yeung, A. S., & Cheung, K. W. (2019). Learner perceptions versus technology usage: A study of adolescent English learners in Hong Kong secondary schools. Computers & Education, 133, 13–26. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2019.01.005

- Loewenthal, K., & Lewis, C. A. (2001). An introduction to psychological tests and scales (2nd ed.). Psychology Press. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315782980

- Marius, P., Marius, M., Dan, S., Emilian, C., & Dana, G. (2016). Medical students’ acceptance of online assessment systems. Acta Medica Marisiensis, 62(1), 30–32. https://doi.org/10.1515/amma-2015-0110

- Martin, F., Stamper, B., & Flowers, C. (2020). Examining student perception of readiness for online learning: Importance and confidence. Online Learning, 24(2), 38–58. https://doi.org/10.24059/olj.v24i2.2053

- Matthíasdóttir, Á., & Arnalds, H. (2016). E-assessment: Students’ point of view. CompSysTech ‘16: Proceedings of the 17th International Conference on Computer Systems and Technologies 2016 (pp. 369–374). https://doi.org/10.1145/2983468.2983497

- Muzaffar, A. W., Tahir, M., Anwar, M. W., Chaudry, Q., Mir, S. R., & Rasheed, Y. (2021). A systematic review of online exams solutions in e-learning: Techniques, tools, and global adoption. IEEE Access, 9, 32689–32712. https://doi.org/10.1109/ACCESS.2021.3060192

- Paas, F., Renkl, A., & Sweller, J. (2003). Cognitive load theory and instructional design: Recent developments. Educational Psychologist, 38(1), 1–4. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15326985EP3801_1

- Pagram, J., Cooper, M., Jin, H., & Campbell, A. (2018). Tales from the exam room: Trialing an e-exam system for computer education and design and technology students. Education Sciences, 8(4), 188. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci8040188

- Papanastasiou, E. C., Zembylas, M., & Vrasidas, C. (2003). Can computer use hurt science achievement? The USA results from PISA. Journal of Science Education and Technology, 12(3), 325–332. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1025093225753

- Pavanelli, R. (2018). The flipped classroom: A mixed methods study of academic performance and student perception in EAP writing context. International Journal of Language and Linguistics, 5(2), 16–26. https://doi.org/10.30845/ijll.v5n2a2

- Rienties, B., & Toetenel, L. (2016). The impact of learning design on student behaviour, satisfaction and performance: A cross-institutional comparison across 151 modules. Computers in Human Behavior, 60, 333–341. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2016.02.074

- Rios, J. A., & Liu, O. L. (2017). Online proctored versus unproctored low-stakes internet test administration: Is there differential test-taking behavior and performance? American Journal of Distance Education, 31(4), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1080/08923647.2017.1258628

- Roscoe, R. D., Wilson, J., Johnson, A. C., & Mayra, C. R. (2017). Presentation, expectations, and experience: Sources of student perceptions of automated writing evaluation. Computers in Human Behavior, 70, 207–221. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2016.12.076

- Schmidt, S. M., Ralph, D. L., & Buskirk, B. (2009). Utilizing online exams: A case study. Journal of College Teaching & Learning, 6(8). Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.19030/tlc.v6i8.1108

- Shin, W. S., & Kang, M. (2015). The use of a mobile learning management system at an online university and its effect on learning satisfaction and achievement. The International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning, 16(3), 110–130. https://doi.org/10.19173/irrodl.v16i3.1984

- Smith, J., & Lipnevich, A. (2018). Instructional feedback: analysis, synthesis, and extrapolation. In (Eds.), The Cambridge handbook of instructional feedback (Cambridge handbooks in psychology) (pp. 591–603). Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781316832134.029

- Soto Rodríguez, E. A., Fernández Vilas, A., & Díaz Redondo, R. P. (2021). Impact of computer-based assessments on the science’s ranks of secondary students. Applied Sciences, 11(13), 6169. https://doi.org/10.3390/app11136169

- Šumak, B., Heričko, M., & Pušnik, M. (2011). A meta-analysis of e-learning technology acceptance: The role of user types and e-learning technology types. Computers in Human Behavior, 27(6), 2067–2077. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2011.08.005

- UNESCO (2021). COVID-19: Reopening and reimagining universities, survey on higher education through the UNESCO National Commissions (ED/E30/HED/2021/01). UNESCO. https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000378174

- Van der Kleij, F. M., & Lipnevich, A. A. (2021). Student perceptions of assessment feedback: A critical scoping review and call for research. Educational Assessment, Evaluation and Accountability, 33(2), 345–373. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11092-020-09331-x

- van Gog, T., Paas, F., & Sweller, J. (2010). Cognitive load theory: Advances in research on worked examples, animations, and cognitive load measurement. Educational Psychology Review, 22(4), 375–378. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-010-9145-4

- Weiss, D., Hajjar, E. R., Giordano, C., & Joseph, A. S. (2016). Student perception of academic and professional development during an introductory service-learning experience. Currents in Pharmacy Teaching and Learning, 8(6), 833–839. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cptl.2016.08.016

- Williams, J. B., & Wong, A. (2009). The efficacy of final examinations: A comparative study of closed-book, invigilated exams and open-book, open-web exams. British Journal of Educational Technology, 40(2), 227–236. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8535.2008.00929.x

- Zhang, T., Xie, Q., Park, B. J., Kim, Y., Broer, M., & Bohrnstedt, G. (2016). Computer familiarity and its relationship to performance in three NAEP digital-based assessments (AIR-NAEP Working Paper #01-2016). American Institutes for Research. https://www.air.org/sites/default/files/downloads/report/AIR-NAEP_01-2016.pdf