ABSTRACT

As global mobility and communications proliferate, ever-increasing exchanges and influences occur across cultures, geographies, politics, and positions. This paper addresses the practice of literacy education in this context, and in particular the nature of engagement across difference and the role of the imaginary in literacies of globality. Grounded in a theorisation of difference and the imaginary in spaces of learning and inquiry, the paper proposes a methodological framework for working across difference that acknowledges and engages with the inevitable but enigmatic resource of often conflicting imaginaries in literacy practices.

Introduction

Thinking with post-critical theorists across disciplines of philosophy, literacy, and globality, this paper is based on an underlying assumption that the world is not ‘fixed and finished, objectively and independently real’ as articulated by Maxine Greene in 1995 in her book, Releasing the Imagination (p. 19). Furthermore, it is in constant and active interrelation across space, material, and time as explored variously by scholars and practitioners in holistic, Indigenous, and new materialist fields of work (see for e.g. Achebe, Citation1988; Barad, Citation2007; Bennett, Citation2010; LaDuke, Citation1999). In the context of contemporary educational research, these propositions are common place, if not obvious. However, within the diverse paradigms and disciplines that coalesce in the transdisciplinary and transnational research and practice of globality, including public health and environmental sciences, for example, they pose direct challenges to positivist approaches to knowledge and education and therefore cannot be taken for granted. An awareness of the onto-epistemological differences that mediate our work in global contexts motivates this article. Through a conceptual inquiry and practical proposition, I argue for the role of the imaginary in education, with a particular attention to literacies of globality.

I begin with a provocation: In between a ‘text’ and a meaning is an imagined space. It is a fluid practice of meaning-making in relation to an understanding of contexts and processes. When a meaning is easily recognisable and familiar in relation to existing circumstances, then the imagination required to support it might be minimal in comparison to the practices of decoding; for example, a red heart on a greeting card signed from a loved one. When a meaning is outside of one’s pre-existing experience, then the imagination required to support meaning making may be much more significant; a facial tattoo or facial scarification on someone from outside of your culture, for example.

In a quickly changing world, literacies are expanding to embrace practices that acknowledge new mobilities, platforms, communications, and contexts; to support people preparing for jobs that have yet to have been invented; for relations that have yet to be introduced. This is a call to ‘imagined futures’ and ‘imagined others’. This article specifically relates to research and pedagogy in literacies of globality. I use the term globality to refer to the state of globalisation, a state that is not fixed (not simply a particular ‘end-result’ of globalisation), but that acknowledges and foregrounds the global scale of affect and interrelationality in our every act from the personal to the political, from the cultural to the ecological (Scholte, Citation2005). Building in particular on the practice and theorisation of literacies of place (e.g. Comber, Citation2015; Sommerville, Citation2007), artefactual literacy (e.g. Pahl & Rowsell, Citation2010), and literacies of sustainability (e.g. Stibbe, Citation2009), literacies of globality involve the practices of sense making in fluid and interrelational global contexts through the multiple texts of culture, language, place, and materials that we navigate from our various positions on the globe. This concept takes seriously the role of globalisation on literacy studies, that pushes us to ‘rethink our conceptual and analytic apparatus’ in this context (Blommaert, Citation2010, p. 1) and consider our work ‘in terms of trans-contextual networks, flows and movements’ (p. 1). Literacy of globality is not a literacy of any particular place, topic, or people; rather it is a practice of making sense and forming actions in relation to an always emerging global context.

This work is motivated by a commitment to literacy education responsive to a world that is unsustainable in its current practices, to a world that faces increasing fragmentation (socially) and vulnerability (ecologically); whilst certain types of expertise, technologies, and global infrastructures continue to proliferate (Ellsworth & Kruse, Citation2013; Singh, Citation2018). The work is grounded in the assumption that to engage with literacies in this context requires not only information but also imagination of other places and contexts, of other futures and pasts. This notion of ‘other’ has always existed in literacy education in terms of positionality in relation to age, gender, class, for example, but increasingly in our globalised and connected world our literacy practices spread over increasing differences of culture, geography, materialities, and language.

An awareness of difference in education is not uncommon, and extensive models have been proposed to address it. From power analyses (e.g. Apple, Citation1996; Ball, Citation2013; Lewis, Citation2001); to intercultural education (e.g. Dolan, Citation2014; Gorski, Citation2008); from epistemologies of the Global North and South that has challenged Northern frameworks of knowledge creation (Santos, Citation2016); to inter-disciplinary research (Callard & Fitzgerald, Citation2015; Nowak, Citation2013; Vogel, Scott, Culwick, & Sutherland, Citation2016). Common across many of these frameworks is a process of making transparent the multiple positions that people bring to a space of learning or inquiry, and of valuing multiple forms of knowledge (Indigenous knowledges, cultural, embodied, and technical knowledges). Taking up the opportunity of the imaginary in spaces that cross differences of many kinds, this article presents the possibility of literacy practices for new understandings; knowledge as ‘a thing in-the-making’ (Ellsworth, Citation2005), or meaning-making as action. This beckons beyond pre-existing knowledges or meanings (without discounting the political, ethical, and pragmatic purpose to working with and across multiple and different knowledges). What I propose in this work is that knowledge or meanings made or materials created are not sufficient to address the variously understood and imagined futures and contexts of our world. Meanings that have been made in contexts past, are located in temporal, spatial, cultural, and political contexts and interactions that are at varying distances from our always emerging present. In order to work with knowledge and meaning-making in action across spaces of ontological difference, there is a need to engage with the imaginary. Both as a site of contestation (e.g. when spiritual belief and physical science are put into direct contact with differing findings) but also, in its always evolving nature, as an essential site of new relations and foundations for new pathways of meaning-making and action (e.g. when a student or researcher takes on a new perspective on something that was unavailable before direct encounter with the subject or collaborator).

From a premise that literacies of globality inherently cross spaces of difference and spaces of the imagination then, this paper proceeds by framing difference as an ontological constant and goes on to address theories of the imaginary in social, global, and material contexts. From here, I take up the concepts of common ground and the collective imaginary as a resource framework within which ethical, situated, and productive literacy practices can emerge. The first part of the paper outlines the conceptual tools upon which the practical implications, proposed in the latter part of the article, are based.

Difference as an ontological constant

In any pedagogical or inquiry endeavour – where one is coming to know – difference is fundamental to the dynamics of engagement. A teacher supports a student, different in position; one idea develops into another different idea, and so on. Literacy practices of globality inherently engage with different times and places (we are locally situated in a global context). Although difference is commonly used with a categorical function – distinguishing one thing from another – conceptions of pedagogy from new materialist theory (e.g. Coole & Frost, Citation2010) and differential ontology (e.g. Deleuze, Citation1994) prompt us towards other ways of working with this fundamental element of our interactions.

Poststructural and postcolonial theory supports complex understandings of how difference works as a mediator in various social and educational contexts (see e.g. Appadurai, Citation1990; Trifonas, Citation2003; Warren, Citation2008). Bronwyn Davies, in Pedagogical Encounters (Davies, Citation2009), draws on Deleuze to describe an understanding of difference that is a continual state of becoming, always becoming different with every new encounter. In this way, difference becomes an ongoing process of differenciation (Davies, Citation2009; Deleuze, Citation1994; Weinstein & Colebrook, Citation2017). In every pedagogical encounter, therefore, be it with a student as a teacher, or with a teacher as a student, be it with a new experience, or new insight, we differenciate in relation. The relations that come into contact through space, through curriculum, through medium, through reading are the momentum for meaning-making and for change. This gives difference expanded potential in literacies that respond to our global and always emerging context. If we shift away from a notion of fixed positions that relate and respond to one another and consider these entities always differenciating in relation to one another, then difference becomes a resource (Rinaldi, Citation2006, cited in Davies, Citation2009), a fuel that feeds an always emerging present. Differences become tools for relations and convergences that are generative.

In literacy practices of globality, differenciation frees us from thinking of the ‘north’ as separate from the ‘south’, or the person as separate from their land or the land of another. The identity of these entities (person, place, land) can be seen as built from their relations with each other and other entities and forces, as opposed to the other way around. Cisney (Citation2013) explains,

the identity of any given thing is constituted on the basis of the ever-changing nexus of relations in which it is found, and thus, identity is a secondary determination, while difference, or the constitutive relations that make up identities, is primary. (np)

Differenciation pushes us to think of the person as a porous entity always becoming different in relation to (amongst other things) their land, that is also always becoming different in relation to (amongst other things) the person. This does not liberate us from identity; rather it requires us to recognise our own positions, but in acknowledgement and in relation to the positions of others, human and non-human. It is this understanding of difference, as an ontological constant, that underpins the proceeding proposal of literacy practices of globality.

The imaginary as an onto-epistemological mediator

Literacy is a situated (cultural, political, etc.) practice, but these positions are formed on complex, historical, interrelational, and material grounds. Understanding the contexts of education from various perspectives makes up a great deal of theory and research in the field of education. Here, I focus on the role of the imaginary as a pedagogical and literacy context, but further as a mediator of the onto-epistemological differences that characterise much of our work.

From the space of the imagination comes the imagined (it has happened in the imagination), and the imaginary (an ongoing presence of something beyond the empirical). The relationship between the imagination and the empirical world is a complex one, but one of prime importance in this inquiry. Imaginaries variously describe the ways that people imagine and ‘know’ their world, how they understand it, what they expect of it, and how they interrelate with the various material and immaterial aspects of it. Imaginaries are formed of the myriad memories, experiences, knowledges, beliefs, and behaviours that a person is exposed to directly and indirectly in their lives. Imaginaries include but exceed the empirical, the logical, and the material.

With roots that emerge from philosophy and aesthetics (Sartre, Citation1940/Citation2004), Mills (Citation1959/Citation2000) made famous the concept of the imagination in the social sciences with The Sociological Imagination in 1959. Astutely, Mills saw the role of the social scientist in linking the individual biography of self (or subject) to the historical contexts surrounding that self, to the social structures present and at play. Mills’ thesis considered today can be seen as humanist and reductive in terms of the complexity of contemporary experience; however, it gestures beyond empiricism, and brings interrelationality to the foreground in a way that is still challenging to many social research practices. Succinctly, Mills proposes that ‘the sociological imagination enables us to grasp history and biography and the relations between the two within society’ (Mills, Citation1959/Citation2000, p. 6).

The imaginary, however, cannot be described in terms of its parts, nor as a web of relations. That being said, relations, connections, and pathways of influence are significant in terms of the roots and causes of behaviour, and this focus is a welcome movement away from atomistic approaches that still dominate much of our educational practice. Charles Taylor (Citation2002, Citation2003) foregrounded the function of the imaginary in his study on the Modern Social Imaginary. In this work, he defines the Social Imaginary as that which ‘enables’ the practices of society. In his understanding, the practices of a society (which include literacies) emerge based on the interrelation of social practices and underlying normative narratives that underpin them. He describes the social imaginary as –

the ways people imagine their social existence, how they fit together with others, how things go on between them and their fellows, the expectations that are normally met, and deeper normative notions that underlie these expectations. (p. 23)

In this way, the social imaginary is again a web of connections and knowledges that inform literacies and behaviour, including ‘deeper normative notions’. It is these deeper normative notions that are of most interest here. The ‘normative’ descriptor may imply a sociological dimension suggesting grand narratives (Lyotard, Citation1984) such as those that contribute to the construction of gender and gender roles, or those that construct class and racial differentiation. But equally, these notions may emerge from cultures of faith, for example, Christianity, and the social and behavioural norms promoted through the variations of organised and informal Christian practices.

In a fixed place, these imaginaries (of future, of present, of past) are developed over time in shared and interconnected ways. In any given culture, overlapping and interdependent ideas of future, present, and past are shared through media, discourse, and behaviours, and create a common imaginary which then informs our actions, choices, anticipations, and fears – differently dependent on our needs and positions. However, as a concept that describes ideas that emerge from beyond one’s empirical senses, the imaginary also has an ever-increasing role in our global reaching policy and practice in international research, mobilities, and pedagogies. As we design projects, solutions, innovations, and interventions into or about physical and social spaces and contexts that are outside of our own, we stretch our imaginations to apply our own empirical literacies to those other spaces.

The imaginary is taken up in various ways to support sociological or sociologically related inquiries and claims. For example, the environmental imaginary is described as –

the constellation of ideas that groups of humans develop about a given landscape, usually local or regional, that commonly includes assessments about the environment as well as how it came to be in its current state. (Davis & Burke, Citation2012, p. 3)

The ‘multi-sited imaginary’ (Anderson, 1983, as cited in Medina & Wohlwend, Citation2014) emerges from people’s engagements and influences as distributed across multiple locations. Perhaps most usefully, Medina and Wohlwend (Citation2014) outline a notion of collective imaginaries (p. 14) that emerge in the convergence of multiple intersecting identity performances and cultural practices.

Building on Medina and Wohlwend, if we consider the imaginary as a place of convergence (of cultural, environmental, experiential information and influence), it not only allows us to address it as a resource but also as a contextual and mediating factor in designing literacy practices. Can we ‘know’ another’s imaginary, like we can know their age, their gender, their language skill-level? No, probably not. But I argue that if we consider the imaginary as a space of convergence, and we can engage with the imaginary as a resource in literacy education, then we can create spaces of collective deep understanding where ideas, objectives, and horizons are not proposed by one and taken up by another; but rather, developed equitably and genuinely across identity, cultural, and disciplinary differences. Nowak (Citation2013), in his work on the ontological imagination, refers to working with and across multiple ‘frames of reference’, and this term provides a useful metaphor for working with the imaginary in practical terms. If we can engage, from our own imaginaries of teaching, of social change, of disciplinary literacy, with those of another, then we can create a new collective space, specific to that convergence. Put another way, if one person can share their frame of reference with another, and overlay it with another’s, then a new frame of reference emerges (that incorporates and is also transformed by the previous two). It is from this new collective space/frame/imaginary that we can hope to move forward pedagogically in relevant, equitable, and globally responsive ways. Imagine an adolescent British or North American person shopping with friends on a weekend: if the ‘reading’ of an imported cheap t-shirt in the high-street shop window (a practice that will draw on a social imaginary along with processes of decoding of colour, style, brand, and so on) can be put into relation with the ‘reading’ of an Egyptian cotton farmer, or the ‘reading’ of young Indian factory worker, or an environmental ecologist (and so on), how might the literacy to make meaning of that object emerge? And how might it affect the actions that are then available to each person to take? Nowak (Citation2013) has described this level of engagement in relation to an ‘ontological imagination’ and as ‘radical, courageous work of the imagination which consists of working through the limitations resulting from historical and institutional conditions, institutional inertia’ (p. 172).

To imagine is associated with dreaming, with play and make believe. It is typically contrasted with that which is real, logical or empirical. The act of imagining brings something forth into the world; it brings forth a new behaviour, a new idea, a new characteristic to the way in which one individual relates to another. As the imagined bears influence on the imaginer, it is brought into relation with the layers of reality, of context that surround that person, and into relation with other individuals. As the imagined monster under the child’s bed is brought to mind, a new behaviour or relationship materialises for that child, with the tangible bed, the visible darkness, the audible wind. Or, building on the example above, as the imagined future with a new t-shirt is taken on, it moves into relation with the money available in that young person’s wallet, with the size and shape in relation to body, and so on. The imaginary then describes the coalescing of empirical experiences and imagined states, both directly impacting each other and creating a context that is neither real nor imagined, but an interrelation of both. The imagined and the experienced mingle to create a social context including the rules, conventions, cultures, and expectations that go along with it. No one encounter can be known by another in its pure sense, but only in terms of its relation (Burnett, Merchant, Pahl, & Rowsell, Citation2014; Ellsworth, Citation2005).

Collective imaginaries and common ground as the first pedagogical objective

Like any other proposition, working with the imaginary as a tool for pedagogy or research is not a benign one. It brings with it an epistemological assumption that is far from normative, let alone neutral. The imaginary, as an interplay of empirical and imagined states, demands us to reject the notion that the world as we know it is predefined, that the learning can be pre-planned, and that the social world can be known through representational analysis, scientific experimentation, or empirical documentation. Data collected in these ways can only represent a moment in time that has been translated and represented into discourse of some kind (language, image, category, etc.). Teaching planned in this way, will only ‘meet’ a fraction of needs to varying degrees. The imaginary, by definition, will constantly elude planning, data collection or representation. Planning precedes, and data collected lags behind, the imaginary.

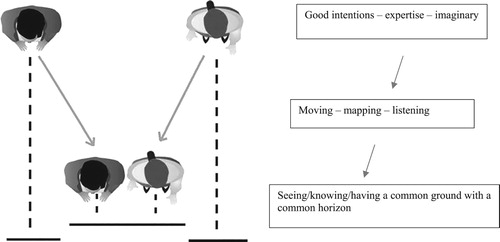

By the same token, we can recognise the agency and possibility in every new encounter; our challenge is to acknowledge that encounter and act according to it. This article does not set out a template but highlights key obstacles and opportunities that can inform existing practices and approaches to literacy teaching and inquiry contexts. What I propose is a literacy encounter whereby each person involved moves, or is moved into new relation, a new collective imaginary, or common ground with the other. That is, through dialogue, shared experience, play, and peer learning, the teacher and the learner, the researcher and participant or collaborator, the high-street shopper and the producer, are moved into a space that they previously couldn’t have occupied. In that space, that common ground – and the corresponding horizon – looks slightly different to the one they had before (see ). It is from this space that a global literacy can emerge, and with which, ethical and appropriate acts, decisions, interventions become possible pathways.

There are many interpersonal and pedagogical tools to build relationship and facilitate common ground; for the purposes of this article, I describe mapping as just one way of facilitating pathways and movement towards another (person, perspective, place, position). There are also substantial obstacles to navigate in this work, and for the purposes of this article, I highlight the obstacle of our own expertise. In contrast to the old adage of ‘we teach from where we are at’, I argue in this paper that we need to ‘de-throne’ (but not to discard) our own disciplinary or cultural expertise in order to move into common ground with another (see ).

‘Mapping’ the real and the imagined: social, material, and global influences

Mapping in qualitative research is a commonly known practice, taken up with a wide range of methods and tools, from personal mapping, collage techniques, to geographic information systems (e.g. Dodge, Kitchin, & Perkins, Citation2011; Gondwe & Longnecker, Citation2015; Parker, Citation2006). Applied to the imaginary, it involves considering the layers of influence, ideas, instincts, memories, and expectations that accumulate to inform one’s empirical engagement with the world. Mapping the imaginary field supporting or informing participants in the learning or inquiry process will have two specific functions. First, it will produce a level of reflection and positioning for learners, teachers, and researchers alike. Second, it will communicate contexts that extend beyond empirical demographics, cultural artefacts, histories, or ecological data.

Whatever the process of facilitation, to explore and share these layers of influence is a process fraught with imperfection, compromise, and contingency. The imaginary is, by definition, not ‘real’, and does not function in terms of logic, linear narratives, or sign systems of representation. However, with the process explicitly valued, learning and awareness can emerge without the need for a complete or comprehensive ‘map’. The process of mapping is flexible and can be taken up in many ways. A very literal use of the practice will involve visualising space, as in a topographic map of a physical area. This could involve paper and pens or digital software to draw spaces, to mark connections and relationships, to indicate proximities or hierarchies of influence. An alternative process of mapping might include metaphor and using visual or verbal metaphors to describe various influences on an overall sense of self. Yet another process might involve using material objects and space. At the end of the mapping process, tangible artefacts are created by a process of reflection and representation, and most importantly, pathways can be identified that lead to common ground between previously separated positions.

Expertise as obstacle

To allow professional access into spaces that cross differences (of age, discipline, culture, geography) requires expertise, qualification, and track record. The degree to which this is the case is often directly related to how well the work is resourced and supported. In this way, it is often the case that those with the most expertise work across the largest spans of difference. A leading US-based child protection specialist, for example, may be called to a work with a critical issue in a remote area of Western Africa (more readily than an emerging or lesser experienced person from the same field) due to his or her international reputation and expertise. A visual artist, well established and renowned may be approached (more quickly than an emerging, or amateur artist) by an epidemiologist to collaborate on a new public health initiative. There are well-founded reasons for the valuing of expertise and an academic culture that supports individual development and the honing of in-depth skill sets. In this way, we manage risk, we ensure the progress of specific fields, we build careers, and we develop new knowledge. Common across contexts of education and research is a privileging of disciplinary expertise.

Our expertise is wrapped up in the literacies we hone, the disciplines we claim, our positions, and the decision-making and practices we lead (Singh, Citation2018). Building on the decolonial arguments of Julietta Singh in Unthinking Mastery (Citation2018), our world can be seen as one in which our collective and individual expertise has defined and demarcated right from wrong, human from animal, life from inanimate matter. Our expertise has separated science from intuition, reason from emotion, you from me. Expertise has colonised not just empires and governance, but knowledges and ways of understanding life and this planet. To see this line of thought through (and its implications in the way we validate and adhere to certain literacies and types of knowledge), our infatuation with expertise is failing the environment, and failing a large percentage of the world’s population. Ignorance plays its part too – but it usually takes the blame, when actually, we who think we know, who have fixed ideas and formulas and facts to lay out, are as big an obstacle to ethical, relational pedagogy and change.

With self-awareness, reflexivity, and preparedness, we can enter a collaborative and educational or exploratory space with good intentions and best practices in place. I argue that to do this ethically, with the ability to genuinely engage with others across difference, requires also bringing into our work a practice of not knowing (Vasudevan, Citation2011). If we agree that there is traction in the idea of a new frame of reference or a convergence of alternative imaginaries to create literacies of globality and globally responsible actions, then we need to not know the frame of reference already, to not know everything we need to know in the specific space of practice before we begin (Nowak, Citation2013). It is with this capacity to not know, that the potential for emerging practice across difference becomes possible.

There are many ways to ‘de-throne’, or de-centre one’s own expertise, and for some it is easier than others. Importantly, it is not a process of developing an awareness of the other, it is not a process of asking questions or carrying out research. But there are overlaps, and research skills such as reflexivity and questioning can certainly help to scaffold the process. The simplest practice to propose is to position oneself as a student, as a learner, in a field and context that is not your own (which differs from positioning yourself as a researcher) and start from a space of un-knowing. When we become used to the sense of not knowing, the potential for learning, for ‘break[ing] with what is supposedly fixed and finished’ (Greene, Citation1995/Citation2000, p. 19) and for engagement with the imaginary, expands. As teachers and researchers, we need to use our expertise but only in relation to a vulnerable and curious practice of not knowing. We need to be both teachers and learners, both facilitators and participants of inquiry, both masters and novices.

In pedagogical contexts, as a practice, this endeavour requires boundaries and structure in itself. An explicit practice of allowing the unknown, unrepresented, and unpredicted into our spaces of collaboration and creation requires intention and leadership that may challenge many traditional pathways of thought and practice. It requires a willingness to loosen our dependence on our own fixed knowledges (my own fixed or assumed knowledge will not match the lived reality of many others who live differently than me). It is with this practice that the imaginary can be put to work in literacies of globality.

Moving bodies-minds-selves, shifting horizons

At its most ambitious, the proposition I am making is that through working with the imaginaries of the diverse people engaged in literacy processes, we can create and act from new collective imaginaries that did not previously exist. In this way, there will be a different assemblage of memory, experience, knowledge, belief, and behaviour, that provides new influence and new possibility to decisions, designs, and practices (and a new frame of reference). That which is imagined and imaginable has shifted – is different. Over extended time and expansive engagement this may, and does, occur naturally (e.g. the gradual adjustment to a digital space that mediates much of our lived reality). At times, new information is discovered that shifts the imaginary abruptly (e.g. the reality of a man walking on the moon). The practical propositions here provide an invitation to address the role of the imaginary within the time-frames that we have as educators. Sometimes that is a week, sometimes it is a year.

‘Writing’ home

The common ground or collective imaginary in a pedagogical practice for literacies of globality may now have shifted, slightly or significantly, in the context of a collaborative endeavour. That endeavour, be it an action, a curriculum, or an intervention has not yet materialised. The process of beginning to act, to teach, to ask questions, from a collective imaginary can require a pragmatic ability to ‘speak’ to the many often disparate stakeholders in pedagogical practice. The imaginary, by its definition, will not teach, answer questions, or create a sustainable equitable world; likewise, on its own, an imagination is unlikely to persuade a learner or a funder. Therefore, a pragmatic practice is required in the pre-existing structures of local or international education or research. This is one of drawing again on specific areas of expertise, weaving knowledges (Cazden, Citation2006; Shukla, Barkman, & Patel, Citation2017), forming questions, and engaging with stakeholders. Nowak (Citation2013) divides the work of the imagination in research into two areas, ‘the sociological (holistic) and the constructive’ (Wesolowski, Citation1975, p. 172). In ‘Writing home’ then, I am referring to this constructive phase which is dependent on strategy and discourse, negotiating the needs and audiences that will inevitably vary in any collaborative or inter-disciplinary project. Within a literacy project this might look like project design, curriculum, or engagement strategies. Similarly, in a research project, this process would involve reporting back through articles, workshops, presentations, public engagement in specific discourses relevant to discipline, country, and sector.

The methodology of engagement with students or participants that has been described here is geared towards building a new foundation for practice or action together. This may involve unexpected outcomes, practices that are unconventional, that are untested, or unfamiliar in the context of the funder, the policy maker, or the institution. This may require that you move outside of your areas of expertise, or that you shift the timeline or objectives of your work. This does not relieve one of the responsibilities of reporting, of accounting for resources, of assessment for impact. Education is always, in part, political, and literacy education is no exception. With this in mind, ‘Writing home’ takes on a political dimension, but one that is specific to the writer(s), and not assuming an all-knowing or omnipresent state in the historical-social-political entanglement that is knowledge production.

Conclusion

If an imaginary is always present and influencing, it needs not only to be clearly understood, but it also needs to be addressed. To teach, to make meaning, to act, to change in the world, in relation to contexts that are outside of our own (e.g. the future, or other parts of the globe), an engagement with the imaginary cannot be ignored. To overlook our own imaginaries in research and pedagogy in a globalised world is to build houses without solid foundations. Houses without solid foundations will collapse with the next major event, be that from a natural or man-made force (and most likely in today’s context a relationship between the two).

Emerging out of postcolonial studies, and coinciding productively in relation to literacy and globality, epistemologies of the South describe a growing body of work that identifies ways of knowing of populations of people (across the globe) who are marginalised and threatened by capitalism and colonialism. Coincident with the political and ethical need to dismantle obstacles to these ‘souths’ needs to be the development of appropriate methodologies to communicate, exchange, and collaborate across the ‘norths’ and ‘souths’ of the world. Santos (Citation2016) in a powerful manifesto in this field writes:

… the diversity of the world is infinite. It is a diversity that encompasses very distinct modes of being, thinking and feeling; ways of conceiving of time and the relations among human beings and between humans and non-humans, ways of facing the past and the future and of collectively organising life, the production of goods and services, as well as leisure. This immensity of alternatives of life, conviviality and interaction with the world is largely wasted because the theories and concepts developed in the global North and employed in the entire academic world do not identify such alternatives. (p. 20)

In the classrooms and public spaces of today, these sentiments are a call to yet again unsettle the ground beneath critical literacies; to find ways to teach literacies that acknowledge the plurality of the world. Building on critical literacy pedagogy, working with difference and the imaginary in literacies of globality requires practices that refuse to lean only on printed texts (a medium dominated by only a small section of the world, and yet relied on to represent a complete picture), but honour the ‘texts’ of cultural practice, affect, place, and time. An approach to literacies that can engage and make meaning with the ecology in which we co-exist and co-create, requires methods that resist defaulting to humanism. What if the world, its meanings and movements, did not revolve around the human perception of them? How might that reposition us as literate people in relation to the places and objects we engage in? Finally, literacies of globality succeed with practices that do not reconfirm our own identities, and our mastery over signs, symbols, and objects; but rather they give us the skills to make meaning and act with awareness and an imaginary of our difference and at the same time our interdependence with the countless forces, peoples, and places of the world.

Engaging with the imaginary in literacy work provides a way forward in a practice that always has global implications. To be literate in a world that doesn’t share one set of values, one conception of time, and one version of human-relations, requires new spaces of convergence and common ground across these differences.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Achebe, C. (1988). Hopes and impediments: Selected essays, 1965–87. London: Heinemann.

- Appadurai, A. (1990). Difference and disjuncture in the global cultural economy. Theory, Culture, and Society, 7(2–3), 295–310. doi: 10.1177/026327690007002017

- Apple, M. W. (1996). Power, meaning and identity: Critical sociology of education in the United States. British Journal of Sociology of Education, 17(2), 125–144. doi: 10.1080/0142569960170201

- Ball, S. J. (2013). Foucault, power, and education. New York: Routledge.

- Barad, K. (2007). Meeting the universe halfway: Quantum physics and the entanglement of matter and meaning. Durham: Duke University Press Books.

- Bennett, J. (2010). Vibrant matter: A political ecology of things. Durham: Duke University Press.

- Blommaert, J. (2010). The sociolinguistics of globalization. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Burnett, C., Merchant, G., Pahl, K., & Rowsell, J. (2014). The (im)materiality of literacy: The significance of subjectivity to new literacies research. Discourse: Studies in the Cultural Politics of Education, 35(1), 90–103.

- Callard, F., & Fitzgerald, D. (2015). Rethinking interdisciplinarity across the social sciences and neurosciences. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Cazden, C. B. (2006, January 18). Connected learning: ‘Weaving’ in classroom lessons. Keynote presented at the ‘Pedagogy in Practice 2006’ Conference, University of Newcastle, New castle.

- Cisney, V. W. (2013). Differential ontology. Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Retrieved from http://www.iep.utm.edu/diff-ont/.

- Comber, B. (2015). Literacies of place and pedagogies of possibility. New York, NY: Routledge.

- Coole, D., & Frost, S. (2010). New materialisms: Ontology, agency, and politics. Durham and London: Duke University Press Books.

- Davies, B. (2009). Difference and differenciation. In B. Davies, & S. Gannon (Eds.), Pedagogical encounters. New York: Peter Lang.

- Davis, D. K., & Burke, E. (2012). Environmental imaginaries of the Middle East and North Africa. Athens: Ohio University Press.

- Deleuze, G. (1994). Difference and repetition. New York, NY: Columbia University Press. P. Patton, Trans.

- Dodge, M., Kitchin, R., & Perkins, C. (2011). The map reader: Theories of mapping practice and cartographic representation. Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell.

- Dolan, A. (2014). You, me and diversity: Picturebooks for teaching development and intercultural education. London: Institute of Education.

- Ellsworth, E. (2005). Places of learning: Media architecture pedagogy. New York, NY: Routledge/Falmer.

- Ellsworth, E., & Kruse, J. (2013). Making the geologic now: Responses to material conditions of contemporary life. Brooklyn, NY: Punctum Books.

- Gondwe, M., & Longnecker, N. (2015). Scientific and cultural knowledge in intercultural science education: Student perceptions of common ground. Research in Science Education, 45(1), 117–147. doi: 10.1007/s11165-014-9416-z

- Gorski, P. C. (2008). Good intentions are not enough: A decolonizing intercultural education. Intercultural Education, 19(6), 515–525. doi: 10.1080/14675980802568319

- Greene, M. (1995/2000). Releasing the imagining: Essays on education, the arts and social change. San Francisco, CA: Jossey Bass.

- LaDuke, W. (1999). All our relations: Native struggles for land and life. Cambridge, MA: South End Press.

- Lewis, C. (2001). Literacy practices as social acts: Power, status, and cultural norms in the classroom. New York: Routledge.

- Lyotard, J.-F. (1984). The postmodern condition: A report on knowledge. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

- Medina, C. L., & Wohlwend, K. (2014). Literacy, play, and globalization: Critical and cultural performances in children’s converging imaginaries. New York, NY: Routledge.

- Mills, C. (1959/2000). The sociological imagination. New York: Oxford University Press. (Original work published 1959).

- Nowak, A. W. (2013). Ontological imagination: Transcending methodological solipsism and the promise of interdisciplinary studies. AVANT. The Journal of the Philosophical-Interdisciplinary Vanguard, IV(2), 169–193.

- Pahl, K., & Rowsell, J. (2010). Artifactual histories: Every object tells a story. New York: Teachers College Press.

- Parker, B. (2006). Constructing community through maps? Power and praxis in community mapping. The Professional Geographer, 58(4), 470–484. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9272.2006.00583.x

- Rinaldi, C. (2006). In dialogue with Reggio Emilia: Listening, researching and learning. Oxon: Routledge.

- Santos, B. (2016). Epistemologies of the south and of the future. From the European South: A Transdisciplinary Journal of Postcolonial Humanities, 1, 17–29.

- Sartre, J.-P. (1940/2004). The imaginary: A Phenomenological Psychology of the Imagination (J. Webber Trans.). London and New York: Routledge. (Original work pubilshed 1940).

- Scholte, J. A. (2005). Globalization: A critical introduction (2nd ed.). Hampshire: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Shukla, S., Barkman, J., & Patel, K. (2017). Weaving indigenous agricultural knowledge with formal education to enhance community food security: School competition as a pedagogical space in rural Anchetty, India. Pedagogy, Culture & Society, 25(1), 87–103. doi: 10.1080/14681366.2016.1225114

- Singh, J. (2018). Unthinking mastery: Dehumanism and decolonial entanglements. Durham: Duke University Press.

- Sommerville, M. (2007). Place literacies. Australian Journal of Language and Literacy, 30(2), 149–164.

- Stibbe, A. (2009). The handbook of sustainability literacy: Skills for a changing world. Devon: Green Books.

- Taylor, C. (2002). Modern social imaginaries. Public Culture, 14(1), 91–124. doi: 10.1215/08992363-14-1-91

- Taylor, C. (2003). Modern social imaginaries. Durham: Duke University Press.

- Trifonas, P. P. (Ed.). (2003). Pedagogies of difference: Rethinking education for social change. New York, NY: Routledge.

- Vasudevan, L. (2011). An invitation to unknowing. Teachers College Record, 113(6), 1154–1174.

- Vogel, C., Scott, D., Culwick, C., & Sutherland, C. (2016). Environmental problem-solving in South Africa: Harnessing creative imaginaries to address ‘wicked’ challenges and opportunities. South African Geographical Journal, 98(3), 515–530. doi: 10.1080/03736245.2016.1217256

- Warren, J. (2008). Performing difference: Repetition in context. Journal of International and Intercultural Communication, 1(4), 290–308. doi: 10.1080/17513050802344654

- Weinstein, J., & Colebrook, C. (2017). Posthumous life: Theorizing beyond the posthuman. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Wesolowski, W. (1975). Wyobraźnia socjologiczna i przyszlość, W. Wesolowski, Z problematyki struktury klasowe [Sociological imagination and the future: From the problems of class structure]. Warsaw: Book and Knowledge.