ABSTRACT

Engaging young children in sustainability challenges poses a pedagogical dilemma to the field of early childhood education. Using species extinction as an exemplary sustainability challenge, this study explores the pedagogical possibilities to engage young children with the potentially cataclysmic death of the bee. The study is framed within a posthumanist framework and draws ideas from post-qualitative research orientation. The study is empirically anchored to a narrative emerging from a staged theatrical performance of child-bee assemblage that enacts the collective agency of ‘bee-ness’. Enabling possibilities of ‘becoming-with the bees’, the performance lends itself to triggering response-abilities and forming of relationships and thus a concomitant emotional affective response to the death of bees. The article suggests alternative directions for a sustainability pedagogy in early childhood education that represent a shift from loving, caring and preserving nature as an object outside ourselves, towards a perspective of ‘becoming-with-nature’, which considers humans as part of/entangled with nature.

Introduction

The Anthropocene is marked as an age wherein humans’ destructive consumptive behaviour has significantly altered the state of the planet (Crutzen & Stoermer, Citation2000). Climate change, global warming, ocean acidification, loss of biodiversity, and species extinction are some of the major manifestations of the Anthropocene. This paper focuses on how to deal with species extinction issues within Early Childhood Education (ECE). As scholars argue, we are entering the sixth wave of mass extinction, which is entirely anthropogenic, i.e. caused by humans (Barnosky et al., Citation2011; Kingsford et al., Citation2009; Rose, Van Dooren, & Chrulew, Citation2017). This scenario begs the question: How can we rethink our way of knowing and relating with other-than-human species in ECE in such a way that they do not become extinct due to our own actions?

Of the various endangered species, this study deals with the alarming death of the honey bee which is becoming increasingly vulnerable in the Anthropocene. Bees play an essential role as pollinators for a healthy ecosystem which provides most of our food production, and an interruption of this process brings about a massive decrease in food productivity and a concomitant breakdown of the food chain (Brown & Paxton, Citation2009). This very creature that sustains our ecosystem and brings nutrition to us is in the grip of an extremely high mortality rate. As indicated by Cox-Foster et al. (Citation2007), the phenomenon called colony collapse disorder has resulted in the loss of millions of beehives for beekeepers in different countries across the globe. This drastic decline in bee population is a result of multiple human-induced (anthropogenic) causes of bee death including habitat destruction and the use of pesticides (Neumann & Carreck, Citation2010). The death of such a vital creature has become foregrounded as a foreboding threat to humans’ survival and the ecosystem at large, which urgently calls for a rethinking of the relationship between bees and humans as an exemplary template for human-animal relationships. Taking up the case of the dying honey bees, this paper explores a different way of knowing and relating to them. What kind of human-bee relationship is needed and possible at this precarious edge of extinction? This challenge calls for the need to better inform ourselves about bees, their role and capacities, in a way that entwines our own prospects and fate with theirs, where we begin to recognize that they are an integral part of our ecosystem and, indeed, of us.

Such anthropogenic changes bring huge challenges. particularly for young children who, compared to older people, are disproportionately affected as they will be inheriting a damaged planet, possibly a catastrophically damaged one. Although the damage has been caused by previous and present older generations, its effects fall unjustly on the young who, at least for now, have hardly contributed to this damage. It is important to explore how this exemplary extinction event is a harbinger of greater destruction and how to address it pedagogically in early childhood education. As we cannot afford to just tell dark doom and gloom stories to young children, lest they give up the dream of change and challenge, we need to have a mechanism to tell stories of entanglement that possibly give hope to our young children without denying and hiding the precarious situation of the ecosystem. Engaging young people meaningfully and responsibly in responding to this destruction brings a tremendous pedagogical challenge to the field of early childhood education. How to prepare children to meet this challenge and understand their relationship with the changing world, and what stories we tell (Haraway, Citation2016; Van Dooren, Citation2014) for the same end, matter a great deal.

With a view to rethink child–animal relationships and pertinent pedagogies, scholars have been calling for a paradigm shift that promotes the entanglement and enmeshment of human/children with the more-than-human world at large and other forms of life in particular. A notable example is the Common Worlds Research Collective (Citation2018), which challenges the ingrained idea of an autonomous individual child, and introduces the common worlds framework which calls for the reconceptualization of the child as entangled with the more-than-human world – particularly animals. They argue that this entanglement has concomitant ‘ethical, political and pedagogical’ implications (Taylor, Citation2013, p. 115). Scholars within the collective (Nxumalo & Pacini-Ketchabaw, Citation2017; Taylor & Pacini-Ketchabaw, Citation2015; Taylor & Pacini-Ketchabaw, Citation2018; Taylor, Pacinini-Ketchabow, & Blaise, Citation2012) have been advocating a collective future rooted in a more-than-human entanglement thinking that invites children to ‘learn-with’ other species in their everyday common world in a non-hierarchical manner.

Drawing on the case of child-pet encounters in urban classrooms, Nxumalo and Pacini-Ketchabaw (Citation2017) highlight the inadequacy of simplistic and anthropocentric relationships to loving, caring and learning about animals. Instead, they underline the need to engage with situated, complex and emerging temporal relationships producing different affective and ethical engagements while learning with the animal, which is required to deal with contemporary anthropogenic challenges that children are inheriting. Likewise, Nxumalo (Citation2018) indicates children’s everyday entanglement with the dying bumblebees and the emerging possibilities it offers to relate, learn with and respond to anthropogenic loss through various affective and embodied modes of knowing. Moreover, drawing on the case of the swamp hen, eel and the turtle, Gannon (Citation2017) demonstrates how an encounter with these animals can serve as a pivotal point for affective and creative engagement leading to critical inquiry and multiple modes of responding to their coexistence with humans. Although Gannon’s work is empirically anchored with secondary school students, its conceptual approach is situated within the ‘common worlds’ framework of early childhood studies. While Nxumalo and Pacini-Ketchabaw (Citation2017) employed a multispecies ethnography to explore children’s encounter with a walking stick pet introduced to a classroom, Nxumalo (Citation2018) employed a worlding methodology as a mode of attuning to the child-bee encounter.

Drawing on the aforementioned earlier studies, this contribution is framed within a posthumanist framework and draws ideas from post-qualitative research orientations (Nordstrom, Citation2015). The paper is empirically anchored in a narrative that emerges from a theatrical performance (of becoming-bee) with an active characterization of the bee. Conceptually, the study focuses on Haraway’s (Citation2008) notion of ‘becoming-with-others’. The central question is: What kind of pedagogies and stories can be used to engage young children with the life and potentially cataclysmic death of the bees?

The article is organized as follows. The first section provides a brief overview on the notion of performance as a practice of becoming-with-others and its conceptualization. The second section presents ideas from post-qualitative inquiry approach with details on the research context and how data are produced in relation to an encounter with a theatrical performance that leads to the emergence of different responses, affects and relationships. The subsequent section offers a description of the theatre per se, and how it affects becoming and learning with the bees. This is followed by a presentation and elaboration of how the theatre lends itself to mobilizing affect which in turn results in forming relationships with and responses to the situation of bees. The following section discusses the strategic benefits of becoming-with-bees. The article ends with a section that suggests alternative directions for a sustainability pedagogy in early childhood education, a shift from loving, caring, and preserving nature as an object outside ourselves towards becoming nature, i.e. humans as co-members of nature.

Performing-others as a practice of becoming-with-others

As indicated earlier, the article is anchored with a theatrical performance of child-bee assemblage wherein humans are acting, doing and ‘becoming-with’ bees. The term performance can have different meanings in different contexts. In a broader sense, the notion of performance entails how we perform and act our life-the doing of it. In everyday life, we act and we become something as we do it. Drawing on Austin’s speech act theory, Reinelt (Citation2002) describes performance as ‘part of an ongoing poststructural critique of agency, subjectivity, language and law’ (p. 203). Fleishman (Citation2009) states that:

Performance involves acts of storying, sounding, moving, feeling and relating that are all embodied and constitute alternative ways of knowing that are non-representational, experimental, and potentially political, both in the sense of transforming knowledge in the academy but also as a means of creating voice in marginalised communities. And that these ways of knowing that proceed from the body give us access to a vast range of ideas that distant and dispassionate contemplation cannot. (p. 126)

While heightening the performative characteristics of language in gender construction, Butler (Citation1999) describes the notion of performativity as a subject formation process, which creates that which it purports to describe and occurs through language and other social practices. Hence, she argues that gender constitutes a continuous series of performative acts not a representational entity (Butler, Citation1999). When something is performative, it produces a series of both effects and affects.

Haraway’s (Citation2008) concept of ‘becoming-with’ as a practice of ‘becoming worldly’ (p. 3) is used as a way to rethink humanness and experience bee-ness. Haraway argues ‘to be one is always to become with many’ (p. 4). She points out that being human is inextricably tied to ‘becoming with’ multi-species others. Haraway specifically writes about political ‘becoming with’ in cross-species relations, i.e. becoming-other of humans. While working with Haraway’s notion of becoming-with, Giugni (Citation2011) highlights that ‘cross-species relational entanglements are useful to transgress all kinds of “borders” of “self”, “other”, spaces, places, languages, politics, pedagogies in new ways’ (p. 12). By highlighting the entangled world we live in and share with multiple other species, Haraway’s (Citation2008) notion of becoming-with captures the relationality and interdependence between humans and non-humans. Humans and non-humans (e.g. animals) share agency and become together while influencing each other. As much as what humans do matters and affects the bees, what the bees do also matters and affects humans. The theatrical performance of child-bee assemblage helps make the entanglement explicit through a performance.

This paper employs the concept of becoming-with by analyzing the theatrical performance of a child-bee assemblage. The assemblage enacts the collective agency of bee-ness where children are performing becoming-bee and enacting bee collective agency. The theatre invites the children: to become bee-like, to try out bee behaviour, and enact bee concerns. The theatrical assemblage is constituted of: actors (in bee suits), a bee set and props, children-becoming-bee-like, and an ecological narrative about bee pollination. In doing so, the theatre captures the urgency and what is at stake within the temporality of the created space. The next section contextualizes the empirical study upon which the article is based.

Encountering a theatrical performance of ‘bee-ness’

This article is based on a post-qualitative study performed within a Swedish pre-school class consisting of 16 children (ages 4–6 years) and three teachers. Prior to the study, consent was obtained from the children. The school administration, the teachers and the parents offered their consent through a written signature. This allowed me to join, follow the group, participate, take notes and record (both audio and video) different emerging encounters in their daily routines.

One characteristic of post-qualitative research orientations is the decentring of the human researcher by consciously avoiding, for a much as is possible, predefined method but rather to begin with an intelligible encounter that compels and presses the researcher to think with the subjects of inquiry (St Pierre, Citation2018). While beginning and thinking with an encounter, a post-qualitative enquirer works with and hopes for what might be possible to emerge from the unexpected, which St Pierre refers as the ‘not yet’ rather than simply what is expected, rationalized or planned for – as in the case with structured methodology. My inquiry began with an encounter with a theatrical performance of child-bee assemblage that captivates and forces me to think with the bees. Hence, as shown below, the theatre per se has become my data and I started to think with it.

In one of the days of my scheduled visit, the preschool group was invited to watch a bee theatre. This is an educational excursion of the children to a free in-store theatre hosted by COOP, one of the biggest grocery companies in Sweden, forming part of the Swedish Cooperative Union. The overall idea of the COOP project is to create ecological awareness, ideas about organic food and sustainable environmental thinking among children (3–7 years old) and the significance of the bees in a fun and playful manner. Both the teachers and I had nothing to do with the performance. None of us intentionally set it up to create enmeshment. It was rather an initiative from COOP to teach and inform children about bees. I just joined the children that day without any intention other than to be with the children to see what might emerge. Being with the children on that day, I had the chance to witness the theatre, which brings about the emergence of the bee as a focus of inquiry.

While serving as a moment of potentiality, the encounter created affect that forced me to rethink and feel the threats posed on the bees. The theatre presents a moment portraying human’s encroachment in the bees’ life through destruction of their habitats. My prior knowledge on the central role bees play in the ecosystem was activated and that urged me to rethink human’s entanglement with this insect, and the attributed vulnerability. As much as the affect the theatre creates in me, as will be shown, it affected the children and the teachers who were also captivated and drawn to the bees and their threatened situation.

Drawing on ideas from post-qualitative thought, my inquiry particularly employs Nordstrom’s (Citation2015) concept of data assemblage. The term assemblage, originally introduced by Deleuze and Guattari (Citation1987), broadly refers to a principle of connectivity wherein any number of things (e.g. words, ideas, people and objects) are gathered within a context. The constituents of an assemblage are in a loose, ad hoc and changing relationship. Thinking and becoming-with the theatre has rhizomatically elicited different responses and consequences in the children’s verbal reactions (discursive responses) and doings (material responses) forming what Nordstrom (Citation2015) refers as data assemblage. For successive weeks and months after the theatre, the children and also the teachers have been repeatedly coming back to the bees every now and then in relation to their everyday pedagogical activities, mundane conversations, outdoor free play, and other instances in the pre-school environment. Various verbal utterances, comments, a song about a flower, bee drawings, bee crafts and bees’ ‘swimming pool’ constitute the data assemblage. The next section offers a description of the theatre in in focus.

The theatre

The theatre piece is an assemblage of actors in bee suits (‘Biesta’ – the queen bee, and ‘Biffen’ and ‘Stickan’ – the two worker bees), a bee set and props, children-becoming-bee-like (participant children), and an ecological narrative about bee pollination. Rosen and Ring (Citation2017) are the playwrights who are playing the character of Biffen and Stickan. The theatre is performed on a stage where the children are invited by Biffen and Stickan to become-like a bee, participate in their activity (reading the instruction from Biesta, dancing, pollinating, fighting back people who spray pesticide on flowers, treating sick bee with medicine and planting flowers) and follow them in a typical day in a beehive. The play is 40 minutes long and presented as a performance mode comedy fable and has three phases: prologue, the disaster phase, and happy ending.

Prologue

The theatrical performance begins with an opening with how Biesta founded the hive after observing what pollen does on flowers. Opening story goes:

Biesta was flying from one flower to another, a pollen suddenly stuck on her and fell on another flower, which later became an apple. Biesta noticed the magical nature of pollen and told other bees how a pollen multiply flowers and turn them into a fruit.

Scene I

Biffen and the children come into the hive and find Stickan oversleeping and snoring. They mock and wake him. Then comes the day’s instruction from Biesta asking Biffen and Stickan to pollinate apples. Biffen and Stickan read the instruction together with the children. The instruction reads: put pollen on the flower, flower becomes an apple, put pollen on the flower, flower becomes an apple … and so on. Together, they repeat the jingle: pollen, flower and apple … pollen, flower and apple … pollen, flower and apple … along with a dance. It is a small choreography with a song having a main verse ‘pollination poll pollination’. After dancing, the bees pollinate the flowers and one big apple is produced. The children and the bees are happy to see the big apple and decide to have an apple fest. Since one apple is not enough for the feast, they agree to pollinate more.

Scene II

The second round of pollination starts with the pollination dance. This time something unexpected happens. Suddenly, a strange voice is heard from outside the beehive, there is smoke in the air, the flowers and other plants are being sprayed with pesticides, and most of them start to fall down and die. The few remaining flowers do not taste good for the bees due to the pesticides. Suddenly, Stickan is struck by a virus. He feels strange, dizzy and can’t find his way around and becomes unable to pollinate. He becomes sick and lies down on the floor. Biffen comes back to the beehive and observes what happened to Stickan, and feels very sad. Biffen continues to pollinate and the next apple has grown, but this time the apple is very small, unlike the earlier one. Stickan suddenly dies. Everything goes wrong. Biffen is distraught and asks the children what to do? Biffen and the children decide that they must do everything again, but this time they have to do it right. Stickan wakes up with the help of medicine suggested by the children.

Scene III

The third round of pollination starts with the dance. This time Biffen is struck by a virus but the children solve the problem with the medicine and the bees go on with the pollen dance. Again the voice and the smoke comes back but the children protect the bees and scare away the people who came to spray on the flowers. Biffen and Stickan check the flowers and learnt that no one has sprayed on them and say ‘the flowers are fine – let’s pollinate more to have the fest’. Biffen and Stickan ask the children to join and help them to pollinate more fruits. Then the children participate in the pollination process, including the dancing and singing that help the bees pollinate. Biffen and Stickan give the children pollen (white round objects), and they jointly pollinate until enough apples grow. Now it is time for the apple fest! Biffen comes with a big plate with the apples.

Epilogue

At the end they all sit together and eat the apples. Biffen & Stickan ask the children if they are willing to help them with one more thing. The children agree. Then, all the children receive a small bag with seeds so that they can plant flowers for the bees at home.

Affect-production and response-abilities

The theatrical performance creates affect in the children that allows them to affectively understand and form relationships with the bees, which in turn lead to the emergence of children’s response-abilities (Haraway, Citation2016) towards the precarious situation of bees. The performance creates a temporal space that yields the potential for the children to deterritorialize (Deleuze & Guattari, Citation1987) and become-with the bees, which allows them to identify themselves with the insects, with intertwined fates and consequences.

‘Response-ability’ to refer to one’s ethical sensitivity and the ability to respond accordingly. Haraway defines ‘response-ability’ as ‘cultivating collective knowing and doing’ (p. 34), ‘sympoiesis’ (making-with) (p. 58), and as responses of becoming-with and rendering each other capable. Deterritorialization, borrowed from Deleuze and Guattari (Citation1987), entails establishing a new relationship, new process and differentiation of role.

Reflecting on what happened in hindsight, pedagogically speaking, the theatre mobilizes affective forces and by doing so enables the children to ‘become-with’ and to ‘engage in’ multiple response-able practices. The emergence of multiple responses is manifested in a range of modes by evoking different thinking, feeling, actions (hands on doings) and utterances by the children. After the show, the bee has become an interesting subject and the children continued to engage with them, which continue to shape their response-abilities towards the insects’ precarious situation. The play serves as a pivotal point for the children in helping them to recognize the extent to which they are implicated in the bees’ lives and deaths. Below I will describe a range of responses and affects produced by the children in the successive weeks and months after the theatre encounter.

Nina (4.5 years old) wanted to have the bees come to the preschool, and said to the teacher ‘I want to invite the bees to the preschool’. This subsequently urged the teacher to ask ‘What do you think we can do to realize that?’ Nina came up with the idea of planting flowers in the schoolyard that led to planting flowers project by the entire group on the gardening day at the preschool. Hence, the preschool’s environment is being made flower rich and pollinator friendly; and the bees are ‘being cohabitated’ in the school yard that challenges territory binaries.

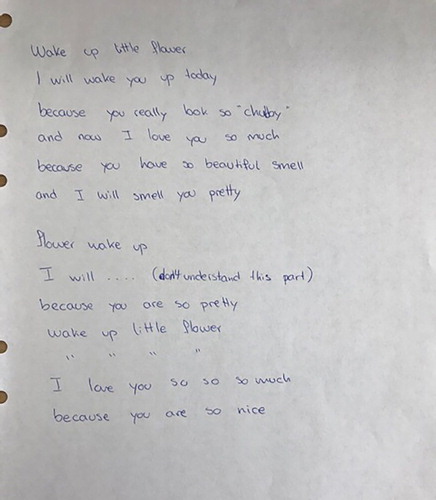

Noah (4.3 years old) refrained from picking flowers: ‘When I play outside, if there are not much flowers, I will not pick any. I will leave it for the bees to drink it.’ Noah’s response reflected an effort to ethically care and also shows some kind of connection to ecosystem of which bees are part, which indicates the reverence the theatre has created in him. Another utterance by Nina was expressed in the form of song ‘The Wake up Flower’ love song – lyrics below as written by her teacher ().

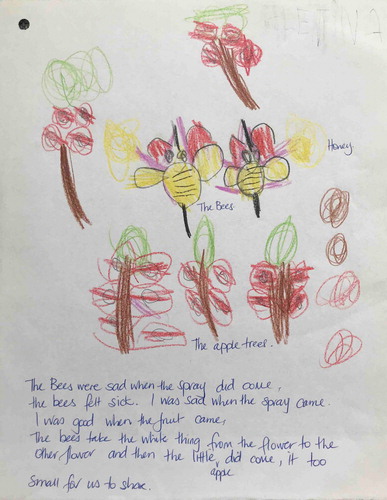

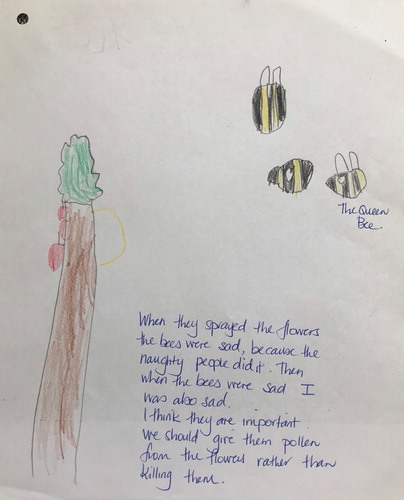

While relating it to the fruits he eats for snack at school, Tom said, ‘Bee give us apples so we can have snack. We also make smoothie for carnival with the apple we got from the bee. Otherwise if all bees die we cannot make smoothie’. Tom’s comment indicates humans’ implication in the disappearance of the bees and our intertwined fate. Impassioned by the bees, Jonas said, ‘Bees do magic … and make fruits … pollen is magical’. In a morning drawing session, Jack came up with an idea of drawing the bees which was well received and joined by many children. A range of thoughts and emotions are expressed in the children’s drawing. Leya’s sad and sick bees and Zena’s naughty people spraying on the bees are presented in and .

Alicia expressed that ‘Spray didn’t make the bee feel good and they don’t drink the flower because it tastes yuck’. Vanessa mentioned ‘When the spray comes the flowers and bee are not happy. It was not nice and the apple became tiny’. Alicia’s yucky response to the spray has also been reflected in her drawing. Zena () describe the people putting the spray as ‘monsters’. While expressing her sympathy, Sara commented:

the spray is bacteria, the bees are sad because the apples are small like a baby … I said go away to the spray … I like it best when the bees dance and pollinate … the bees are scared because the people are bigger than them.

As time goes, the affects the theatre produced, the ideas generated and the conversations emerged continued and meandered along different inroads of possibilities. The bees have continued to be part of the children’s and the group’s everyday activity at the preschool environment. The children have continued to come into an alliance with the bees through various discursive and material engagements. More doings are generated forming larger and larger data assemblages. The teacher extended the bee drawing activity to a whole group bee craft project. On another day, during outdoor free play, Tom made a swimming pool, out of stones and glass balls, because he thinks the bees want to swim and relax when it is warm ( and ).

More desires have continued to be evoked: Sara described what she experienced during a weekend as follows:

On Saturday, I did go to a car and saw a bee on a cold floor … he can’t fly because it has only one wing. I tried to pick and help him fly but he didn’t fly. I think he was injured and I tried to see if he can move and fly, but he can’t. I cannot do anything for him so I did leave him there … I think he is not better, I think.

Ela recalled an earlier bee-encounter and stated:

One day, when I was in my summer house, my sister was trying to catch the bee. It is not nice, but the bee did fly fast and she could not catch it. We have to leave the bees alone.

Few days after the theatre, an email sent to the teachers from Peter’s mum indicates his reaction to the theatre:

When I picked him on Wednesday, he was bouncing home with his fruit bag (which contained fruits and flower seeds …) in hand and he talked about Biffen and Stickan and a rap song that goes ‘pollenera poll-poll-inera’. He thought that was very good.

Likewise, a comment from one of the teachers also confirms how the theatre influences the children:

Ever since the theatre, the children talk a lot about it – they really took it to their heart. They love singing the song – it is stuck in their head. Last week, we also walked around and pollinated while enjoying the sun. We looked at and documented spring signs and small insects in nature.

All the aforementioned excerpts are examples showing how the children have been affected by the theatre. Framing it with Haraway’s (Citation2016) term, these response-abilities – Noah’s thought to refrain from picking, Nina’s compassionate singing/doing, Sara’s sympathy (feeling) for the bee on the cold floor, Tom’s understanding of not to take the smoothie for granted, Jonas’ appreciation of pollen as magic, and Alicia’s association of yucky feeling with the spray/pesticide – are all provoked by the theatre. These response-abilities are conveyed in the form of ‘thinking-feeling-doing’ (Barad, Citation2007) together not only as a separate cognitive activity that we often expect from an agentic child, but rather enact a collective child-bee assemblage.

Sustainability benefits of becoming a bee

As a mode of pedagogy, becoming-with the bees in the theatre offers an alternative possibility to the wider practice in ECE, which tends to moralizing children to sympathize and care for animal subjects. By urging ethical responses that address the entangled subjectivities, the theatre enables possibilities to imagine for what Haraway (Citation2008) refers to as ‘opening to shared pain and mortality and learning what that living and thinking teaches’ (p. 83). In doing so, the performance has served as a way of knowing and relating to the bees, which ultimately led to the emergence of response-abilities in the children.

As indicated in the emerged data assemblage, there are ‘quite definitive response-abilities that are strengthened’ (Haraway, Citation2016, p. 115) in the children’s reactions which are manifested in various discursive and material engagement with the bees. All the aforementioned actions and utterances of the children have a performative effect as they result in a change or transformation, i.e. generate response-abilities. The theatre of the performing bees created the possibility of understanding species relations as a performance with the performative effect, which could be a way to deterritorialize and become nature. As the children encounter and engage with the theatre, they experience themselves as part of nature, not separate from it, i.e. they become with the bees.

The theatre offers this possibility of becoming-with the bees without signalling a discouraging and pessimistic view about the situation of the bees. Rather, it creates a joyful moment to deal with the problem, which allows us to engage with and engender a life-giving process, pollinations, and form kinship with the bees. It created and led to moments wherein human beings are part of nature, included with other species, both imaginative and real. Moreover, the theatrical performance of becoming-with provides a moment of reassessment, and of rethinking of our own capacity and vulnerability. It allows a different way of knowing, caring and hearing about the bees by portraying how to learn to collectively think with the bees. It also enables the potential to expound the human’s integrated relationship with the bees, and the encounters exhibited in the play permitted to see this relationship differently.

While producing the children’s ‘becoming-with’ the bees, the theatrical child-bee assemblage, opens up spaces to relate to the bees and engage with their situation in different discursive and material expressions. Performing ‘bee-ness’ opens up possibilities for post anthropocentric analytical position and paves the way to see humans’ relation/entanglement differently, which can help to re-position humans in a shared and interrelated world that we live in. In doing so, the performance de-centres the human child and triggers the becoming of a symbiotic network and the unity with ‘nature’-bees in particular. As a strategy, becoming-with-bees appears to have elucidated the human-bee entanglement – a story that matches the historicity of our time (Anthropocene) and what is happening to us – humans. The theatre catalyses a possibility to recode and decentre the human and, by doing so, to compose an alternative ontology in today’s precarious time.

The children, while participating in the performance, became subjective seekers of bee-ness rather than posing as detached observers discovering and learning definitive facts/truth about the bees. By inviting the children to enter into a relational imagining of their own ‘bee-ness’, the theatre transports and carries the children into a different, imagined reality and life of bee and ‘bee-ness’, a new way of being, indeed, a new way of ‘bee-ing’. This evokes affect and allows for the children to feel the affectual charge of materialities. The children are not just cognitively taken in the moment, but also engaged with an affective experience of ‘bee-ness’ and their identities. They are moved into another world, one that is inevitably entangled with our own. This entangled world is brought into being through the material and discursive relationship that the children are experiencing.

As Haraway (Citation2016) indicates, we have to learn how to ‘stay with the trouble’ and live in tune with others as we are entangled with the more-than-human world. Highlighting the entanglement helps us see beyond the narrow anthropocentric view of the world and helps us pay attention to the complex and, mostly, symbiotic ways in which we are related with other species. Understanding such entanglement can open up and transform our way of being, thinking and doing which can help us to avoid our tendency to falsely separate ourselves from other creatures, which eventually can help us come to terms and ‘thrive’ with the more-than-human world. Drawing on Haraway (Citation2008), the theatrical performance can be taken as an exemplary instance demonstrating how ‘learning to play with strangers’ (p. 243) can take place in practice. In this regard, it is important to highlight the pedagogical significance of the theatrical comedy fable which could be utilized as a tool for addressing sustainability issues in early childhood. Such pedagogy could have the potential to contribute to the endeavour to restore environmental education in the early childhood. Thus, turning into a ‘multi-species becoming-with’ (p. 260) approach could be an alternative pedagogy towards sustaining humans in staying with the trouble on terra, the planet Earth (Haraway, Citation2016).

Conclusion and way forward

Through becoming-with bees, the theatre provides a possible strategy for moving away from anthropocentrism to a more bio-centric way of thinking. It does so by mobilizing affect that leads us (children, teachers, and researcher) to empathize with and relate to the bees while simultaneously being implicated in and sensing our own affective vulnerability through an emotional response to their cataclysmic death. The theatre serves both as a mode of pedagogy and as a powerful tool for exploring and stimulating new knowledge on complex issues such as species extinction and sustainability. Apart from being a mere experience, one among others, the theatre affected the preschool environment by shaping and altering the pedagogical activities to become geared towards the bees, thus changing the children’s sense of their relationship with the bees and the environment in general.

Here, teachers have an integral role to play by creating a pedagogical space that allows such encounters to flourish into a deeper inquiry. Traditionally, the pedagogy within early childhood education for sustainability (ECEfS) has taken a certain path which includes: nurturing love and care for nature and the need to preserve it, building agency, focusing on science, and action-oriented practices. However, these approaches do not transgress anthropocentrism. Teachers need to reflect on and ask important questions: what kind of knowledge has the power to influence us (researchers and educators) and hence to influence the children that we are educating? What kind of knowledge do we appreciate, and what conditions do we create for the same end? How can we become affected by the cataclysmic collective death stories of our time, and in turn allow the children to be affected? Are we fostering creativity, or are we unintentionally stopping it while sticking to certain conventional ways of knowing and being?

Therefore, the pedagogy in ECEfS should engage children and keep them closer to the problem, which Haraway (Citation2016) refers to as staying with the trouble and playing with the strangers (e.g. the bees) while telling lively stories. This calls for a transformative pedagogy that directly calls on teachers to think about how to recognize their pedagogical activities. A key point here is to move away from viewing children as sole agents and autonomous learners, or what Taylor (Citation2017) refers to as environmental stewards. Instead, children should be allowed to think and learn with the more-than-human world that they are immanently entangled with and that they constantly encounter in their everyday life. This is particularly important in early years education because children are still open and able to see themselves as integral to this world, and capable of developing a symbiotic relationship of ‘becoming with’ this world, whereas adults often will have lost this capacity, ironically, in part as a result of the education they received.

In closing, encounters such as the theatre can have the potential to offer multiple possibilities to engage with various environmental and global challenges of our time. Supporting Gannon’s (Citation2009) suggestion:

[W]e need to create a space for emergent pedagogical possibilities that are open to the flows and intensities of encounters and pedagogical moments each of which ‘has its own particular spatial, temporal and affective modalities and performances’ and each of which gives rise to its own ‘ethics of’ encounter and responsibility’ and response-abilities. (p. 69)

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

References

- Barad, K. (2007). Meeting the universe halfway: Quantum physics and the entanglement of matter and meaning. Durham: Duke University Press.

- Barnosky, A. D., Matzke, N., Tomiya, S., Wogan, G. O. U., Swartz, B., Quental, T. B., … McGuire, J. L. (2011). Has the Earth’s sixth mass extinction already arrived? Nature, 471, 51–57. doi: 10.1038/nature09678

- Brown, M. J., & Paxton, R. J. (2009). The conservation of bees: A global perspective. Apidologie, 40(3), 410–416. doi: 10.1051/apido/2009019

- Butler, J. (1999). Gender trouble: Feminism and the subversion of identity. New York: Routledge.

- Common Worlds Research Collective. (2018). Common Worlds Research Collective website. Retrieved from http://commonworlds.net/

- Cox-Foster, D. L., Conlan, S., Holmes, E. C., Palacios, G., Evans, J. D., Moran, N. A., & Martinson, V. (2007). A metagenomic survey of microbes in honey bee colony collapse disorder. Science, 318(5848), 283–287. doi: 10.1126/science.1146498

- Crutzen, P. J., & Stoermer, E. F. (2000). Global change newsletter. The Anthropocene, 41, 17–18.

- Deleuze, G., & Guattari, F. (1987). A thousand plateaus: Capitalism and schizophrenia. London: Continuum.

- Fleishman, M. (2009). Knowing performance: Performance as knowledge paradigm for Africa. SATJ: South African Theatre Journal, 23, 116–136.

- Gannon, S. (2009). Difference as ethical encounter. In B. Davies & S. Gannon (Eds.), Pedagogical encounters (pp. 69–88). New York: Peter Lang.

- Gannon, S. (2017). Saving squawk? Animal and human entanglement at the edge of the lagoon. Environmental Education Research, 23(1), 91–110. doi: 10.1080/13504622.2015.1101752

- Giugni, M. (2011). Becoming worldly with: An encounter with the early years learning framework. Contemporary Issues in Early Childhood, 12(1), 11–27. doi: 10.2304/ciec.2011.12.1.11

- Haraway, D. (2008). When species meet. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press.

- Haraway, D. J. (2016). Staying with the trouble: Making kin in the Chthulucene. Durham: Duke University Press.

- Kingsford, R. T., Watson, J. E. M., Lundquist, C. J., Venter, O., Hughes, L., & Johnston, E. L. (2009). Major conservation policy issues for biodiversity in Oceania. Conservation Biology, 23(4), 834–840. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1739.2009.01287.x

- Neumann, P., & Carreck, N. L. (2010). Honey bee colony losses. Journal of Apicultural Research, 49(1), 1–6. doi: 10.3896/IBRA.1.49.1.01

- Nordstrom, S. (2015). A data assemblage. International Review of Qualitative Research, 8(2), 166–193. doi: 10.1525/irqr.2015.8.2.166

- Nxumalo, F. (2018). Stories for living on a damaged planet: Environmental education in a pre-school classroom. Journal of Early Childhood Research, 16(2), 148–159. doi: 10.1177/1476718X17715499

- Nxumalo, F., & Pacini-Ketchabaw, V. (2017). ‘Staying with the trouble’ in child-insect-educator common worlds. Environmental Education Research, 23(10), 1414–1426. doi: 10.1080/13504622.2017.1325447

- Reinelt, J. (2002). The politics of discourse: Performativity meets theatricality. SubStance, 31(2), 201–215. doi: 10.1353/sub.2002.0037

- Rose, D. B., Van Dooren, T., & Chrulew, M. (2017). Extinction studies: Stories of time, death, and generations. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Rosen, A., & Ring, K. (2017). Biffen’ and ‘Stickan’: Narrative sequence for children’s bee theatre. https://www.coop.se/Globala-sidor/OmKF/.../Coop-Vast/Coops-Lilla-Ekoskola

- St Pierre, E. A. (2018). Post qualitative inquiry in an ontology of immanence. Qualitative Inquiry, doi: 10.1177/1077800418772634

- Taylor, A. (2013). Reconfiguring the natures of childhood. London: Routledge.

- Taylor, A. (2017). Beyond stewardship: Common world pedagogies for the Anthropocene. Environmental Education Research, 23(1), 1–14. doi: 10.1080/13504622.2016.1149553

- Taylor, A., & Pacini-Ketchabaw, V. (2015). Learning with children, ants, and worms in the Anthropocene: Towards a common world pedagogy of multispecies vulnerability. Pedagogy, Culture & Society, 23(4), 507–529. doi: 10.1080/14681366.2015.1039050

- Taylor, A., & Pacini-Ketchabaw, V. (2018). The common worlds of children and animals: Relational ethics for entangled lives. London: Routledge.

- Taylor, A., Pacinini-Ketchabow, V., & Blaise, M. (2012). Children’s relations to the more-than-human world: Editorial. Contemporary Issues in Early Childhood, 13(2), 81–85. doi: 10.2304/ciec.2012.13.2.81

- Van Dooren, T. (2014). Flight ways: Life and loss at the edge of extinction. New York: Columbia University Press.