ABSTRACT

The definitions of internationalisation have been contested and require contextualisation. Despite the long-standing practice of and research on higher education internationalisation in Mainland China, ambiguities regarding the concept persist. This study examines academic discourses on the internationalisation of Chinese higher education. It draws on a systematic literature review of 240 journal articles published in Mandarin Chinese and English. Findings reveal the prevalence of defining internationalisation using Western discourses and attempts to provide Chinese definitions of internationalisation. The review also identifies the coexistence of educational, economic, political, and cultural logic clusters in the discourses on the internationalisation of Chinese higher education. In addition, the article discusses temporality, spatiality, affectivity and relationality in the discourses and their corresponding themes. It concludes with a discussion on the ‘Chinese characteristics’ of higher education internationalisation, and reflections on the common dichotomies and myth in the existing literature.

1. Introduction

Contemporary Chinese higher education has been strongly shaped by internationalisation (Yang, Citation2014). But what does ‘internationalisation’ mean? Despite the plethora of studies on the internationalisation of higher education (IHE), a consensus on its definition has yet to be reached.

‘Internationalisation’ is often discussed with relevance to ‘globalisation’. For instance, Knight (Citation1999) considered internationalisation as a ‘proactive response’ to its ‘catalyst’ – globalisation (p. 14). The later definitions by Knight (Citation2003) followed this distinction, and defined IHE as ‘the process of integrating an international, intercultural, or global dimension into the purpose, functions, or delivery of post-secondary education’ (p. 2).

The ‘constructed antagonism’, ‘ideological binary’ and ‘linear causal framework’ between internationalisation and globalisation have been questioned (Brandenburg & De Wit, Citation2015; Marginson, Citation2022). Marginson (Citation2009, Citation2022) argued that internationalisation and globalisation create conditions and possibilities for the other, and the definition of internationalisation should be non-ideological and neutral. He suggested that internationalisation is to ‘create the action or growth of relations between nations, or between organisations or persons in nations’ (Marginson, Citation2022). Matus and Talburt (Citation2009, p. 525) revealed that universities tend to position themselves ‘as actors responding to the inevitability of economic globalisation’ and construct a binary of an abstract global space ‘out there’ and their local space. Following Massey (Citation2005), Matus and Talburt (Citation2009) proposed moving beyond the binary positioning. They argued that the global is constructed, and that universities are active participants in its production.

Ideas of ‘internationalisation’ also face critical scrutiny, when considering their colonial and postcolonial roots, neoliberal ideologies, power hegemony and struggles, and values and ethics (Brandenburg & De Wit, Citation2015; Marginson, Citation2022; Pashby & de Oliveira Andreotti, Citation2016; Stein, Citation2021). Despite the ‘critical turn’ in mainstream internationalisation studies towards critical perspectives, a review by Stein (Citation2021) revealed ‘a persistent failure to reckon with both the enduring role of colonialism in internationalisation, and relatedly, a failure to address complexity, uncertainty, and complicity in our efforts to address this colonialism’ (p. 1773).

Specifically, does the concept of ‘internationalisation’ developed from ‘Western’ groundings fit with non-Western contexts? Rui Yang (Citation2021) pointed out that Knight’s definitions largely reflect Western and institutional perspectives, rather than seeing the higher education system as a whole. Yang (Citation2014, Citation2021) also highlighted the need to understand the tension between internationalisation and endogenisation, which is central to contemporary East Asian and Chinese higher education (Marginson & Xu, Citation2022). Nonetheless, Yang (Citation2021) argued that in the Chinese context, ‘the concept of internationalisation has been used for a long time and massively, both in official and unofficial academic and public discourses; therefore, its connotation has become ambiguous’ (p. 167). Similarly, the concepts of the ‘West’ and ‘Westernisation’ also require unpacking in the Chinese context (Marginson & Xu, Citation2022).

This study approaches ‘internationalisation’ as an ambiguous, complex and dynamic concept that requires contextualisation. It draws on a systematic review of 240 journal articles published in Mandarin Chinese (‘Chinese’ hereafter) and English on the internationalisation of Chinese higher education (ICHE). In this article, academic discourses are not only texts in scholarly publications. The author understands discourses as constructed historically, socially, culturally and politically. Therefore, discourses carry the power to define the thinkable and unthinkable, and construct knowledge, realities and imaginaries (Bacchi, Citation2000; Foucault, Citation1980; Matus & Talburt, Citation2009). Based on the analysis, this study discusses the definitions of the IHE, multiple logic of the IHE, and key features of the academic discourses on the IHE in the Chinese context.

2. Past reviews on higher education internationalisation

2.1. Past reviews of English-language literature

Previous meta-reviews published in English language identified a steady growth of English-language publications on this topic (Tight, Citation2021; Yemini & Sagie, Citation2016). The search conducted by Tight (Citation2022) in Scopus identified 3295 publications on IHE in English. Some reviews covered English-language publications in Google Scholar, Scopus and Web of Science (WoS) (Kosmützky & Putty, Citation2016; Tight, Citation2021, Citation2022; Yemini & Sagie, Citation2016), whereas others focused on publications in specific English-language journals (Bedenlier, Kondakci, & Zawacki-Richter, Citation2018; Mittelmeier & Yang, Citation2022; Mwangi et al., Citation2018).

Five meta-reviews published in Chinese included English-language literature on IHE. Three of them examined English-language publications in the Web of Science (WoS) (Hong & Zhang, Citation2020; Liu, Citation2018; Ma & Cai, Citation2016), with two using network and bibliometric analysis methods. The other two reviews conducted network and bibliometric analyses on the Chinese and English publications in both WoS and the Chinese Social Sciences Citation Index (CSSCI) (Liu, Yang, & Ni, Citation2020; Yi & Zeng, Citation2020).

Past meta-reviews revealed that the major themes in IHE research are diverse, wide ranging and evolving (Bedenlier et al., Citation2018; Lee & Stensaker, Citation2021; Liu, Citation2018; Mwangi et al., Citation2018; Tight, Citation2021; Yemini & Sagie, Citation2016; Yi & Zeng, Citation2020). Lee and Stensaker (Citation2021, p. 160) concluded that internationalisation and globalisation research is embedded in multiple perspectives, namely, political, economic and cultural, thereby leading to ‘theoretical silos’ in the field. In terms of the concept of ‘internationalisation’, a review by Mwangi et al. (Citation2018) found that it was not explicitly defined or conceptualised in most of the publications; and when defined, the concept is interpreted with mainly positive connotations that require critical examination.

All reviews identified patterns of ‘Western’ or Anglophone dominance. The top three geographical focuses of IHE research are the United States (US), Australia, and the United Kingdom (UK) in Bedenlier et al. (Citation2018); the UK, the US, and Australia in Tight (Citation2021); and Australia, the UK, and New Zealand in Mittelmeier and Yang (Citation2022). The dominance of hegemonic powers is also reflected in Western-dominated institutional affiliations of the authors and editorial boards (Mwangi et al., Citation2018; Tight, Citation2021), unbalanced citation counts of publications from different regions (Hong & Zhang, Citation2020; Ma & Cai, Citation2016; Yi & Zeng, Citation2020), and one main theme on global English as the lingua franca in higher education and research (Tight, Citation2021; Yemini & Sagie, Citation2016).

Notably, previous reviews identified the lack of criticality to address power and hegemony issues in IHE research (Mwangi et al., Citation2018), the need to explore beyond national borders using multi-level and multi-actor approaches (Lee & Stensaker, Citation2021), and the trends of pluralisation in IHE research in terms of geographical focuses (Mittelmeier & Yang, Citation2022; Tight, Citation2022).

2.2. Past reviews of Chinese-language literature

Previous meta-reviews of Chinese-language literature on the IHE revealed a similar pattern of expansion in this field (Hong & Zhang, Citation2020; Jiang, Su, & Cui, Citation2011; Liu et al., Citation2020), despite a slow growth rate in the past decade (Dong, Dong, & Zhang, Citation2021; Liu, Citation2018). Most of such reviews were published in Chinese, with two published in English (Li & Xue, Citation2022; Wu & Zheng, Citation2022).

Most of the reviews used the China National Knowledge Infrastructure (CNKI, which includes the CSSCI) or CSSCI databases, while a few focused on selected CSSCI journals (Li & Xue, Citation2022; Liu, Citation2013; Wu & Zheng, Citation2022). Cai, Zhu and Xiong (Citation2020) searched the CNKI and Chao Xing Periodical databases and identified 5656 Chinese-language publications on the IHE between 1949 and 2019. Many of the reviews used network and bibliometric analysis methods, with a few using content or thematic analysis methods.

Past reviews revealed diverse and increasingly pluralised themes in Chinese-language publications on IHE (Cai et al., Citation2020; Dong et al., Citation2021; J. Xu, Citation2006; Yi & Zeng, Citation2020). Several reviews identified links between national policy changes, international geopolitics and Chinese scholars’ research directions (Dong et al., Citation2021; Jiang et al., Citation2011; Liu, Citation2013; Wu & Zheng, Citation2022; Yi & Zeng, Citation2020), which they termed as ‘chasing (research) hotspots’ (J. Xu, Citation2006). Meta-reviews throughout the years found that theoretical discussions on internationalisation, empirical research, and micro-level research are scarce in the Chinese-language literature. Some reviews also found ‘repetitive contents and opinions’ in the Chinese-language literature (Jiang et al., Citation2011; Liu, Citation2013; Wu & Zheng, Citation2022; J. Xu, Citation2006; Yi & Zeng, Citation2020).

Most of the reviews approached IHE as a general topic, including IHE in China and in other countries. Only one review focused on the ICHE, but only examined the ICHE in the post-COVID-19 period (Li & Xue, Citation2022). The most examined foreign countries are the US, the UK and France in Jiang et al. (Citation2011), which they termed as ‘Western’ and ‘developed countries’. Jiang et al. (Citation2011) pointed out the need to broaden the research scope to ‘developing countries and regions’ (p. 149). Jining Xu (Citation2006) observed that the relationship between globalisation, internationalisation and indigenisation is an important topic in the scholarship. Some of the reviews also highlighted the importance of protecting Chinese research and warned against the risk of ‘Westernisation’, ‘cultural invasion’ and ‘cultural hegemony’ in IHE research (Dong et al., Citation2021, p. 6; J. Xu, Citation2006).

3. Methodology

This study drew on a systematic review of the literature on the ICHE published in Chinese and English languages. The reasons behind the inclusion of both languages are threefold.

First, as the publications in the two languages represent most of the research on this topic, bilingual reviews are more comprehensive than monolingual reviews in terms of coverage. Second, in the humanities and social sciences, publications in different languages can differ in their ontologies, epistemologies and paradigms. Therefore, this review aims to explore such differences and similarities. Third, the ‘international’ higher education research space is largely Western and English dominated (Mwangi et al., Citation2018). Thus, by bridging the discourses in Chinese and English, this study intends to contribute to the epistemic diversification of this space (e.g. X. Xu, Citation2022).

3.1. Literature search and screening

The author, who is proficient in Chinese and English, conducted the literature search on 18 February 2022 in the Scopus, WoS and CNKI databases with the following search strings (see ).

Table 1. Search strings.

For the English-language literature, the search terms were ‘internationalisation’, ‘China’ and ‘higher education’ and their variations. For the Chinese-language publications, the search terms were ‘internationalisation’ and ‘higher education’ and their variations in Chinese. The terms ‘China’ and ‘Chinese’ were omitted, as they did not consistently appear in the publications in Chinese on Chinese higher education. The search areas were titles, abstracts and keywords in Scopus and the CNKI, and ‘topic’ in WoS, which included titles, abstracts, authors, keywords and keywords plus. The Chinese search was limited to the ‘core’ academic journals defined by the Peking University Core Journal List and CSSCI journal list.

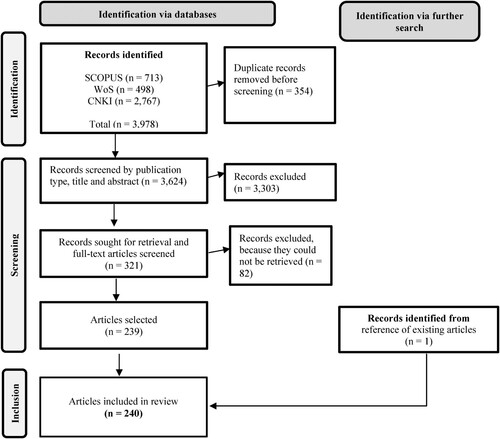

The initial search resulted in 3978 publications, including 713 from WoS, 498 from Scopus, and 2767 from the CNKI. Notably, although the three databases were widely used due to their relatively large coverage, each has limitations (e.g. Mongeon & Paul-Hus, Citation2016; Shengli, Citation2014). The coverage limitations were addressed through the search of multiple databases and review of the references listed in the final selection. Nonetheless, this search may have missed some publications on this topic.

All the search results were imported to Rayyan, a web-based tool for systematic reviews, for deduplication and screening. illustrates the screening process, which was informed by the PRISMA protocol (Page et al., Citation2021). The screening was based on publication type, titles and abstracts.

Figure 1. Flow chart of article-filtering process. Informed by Page et al. (Citation2021).

Books, book chapters and review articles were included in the initial search but excluded in the screening stage. This is because the initial search resulted in 89 books and 36 book chapters in English, but no books or book chapters in Chinese. Not all the books and book chapters in English were relevant to the scope of the review or available as full texts. To ensure the comparability of the analysis in Chinese and English, the author decided to only include journal articles.

When screening the titles and abstracts, the inclusion criteria are conceptual discussions and empirical studies on the IHE in Mainland China (excluding comparative studies using China as one of the cases). Included studies need to be predominantly at the national scale, rather than regional, institutional or individual scales.

In the final screening stage, references used in the selected articles were scanned, and one additional journal article was identified. The final collection included 240 journal articles, 224 in Chinese and 16 in English.

3.2. Analysis of the literature

This review used a thematic analysis approach, rather than network or bibliometric analysis methods commonly used in the previous meta-reviews on Chinese literature, to bring more in-depth discussions drawing on the contents of the literature. All 240 journal articles were coded and analysed thematically using NVivo 12 and handwritten notes. The codes were generated inductively based on the texts. Some of the codes were in English, others were in Chinese. The codes were categorised, thematised and compared after the first round of coding. Key themes identified in the final analysis lead the Section 4 of this article.

When writing this article, the author translated all Chinese codes and quotations into English. Some of the Chinese articles had English translations of their title in the original publication. The author translated the titles of the rest. When necessary, the author also noted the original Chinese characters and pinyin for some translated terms. Because of formatting requirements, Chinese names were mostly converted into Romanised pinyin, and a name–surname order was adopted.

3.3. Features of the literature

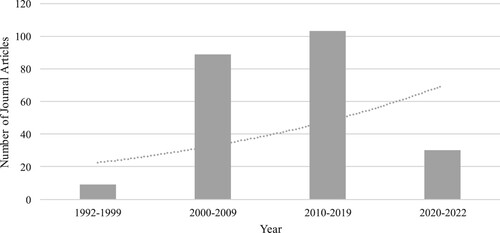

shows the steady growth of the macro-scale discussions on the ICHE from 1992 to 2022. The earliest publication on the ICHE was ‘The localisation and internationalisation of Chinese higher education’, published in Chinese by Shengbing Li (李盛兵) and Maoyuan Pan (潘懋元) in 1992 (Li & Pan, Citation1992).

Most of the authors were based in universities, research institutions and government offices in Mainland China, with only a small number of them based outside China. In Chinese publications, 102 of them provided information on the authors’ gender. Among them, 88 male authors appeared in 69 articles, and 66 female authors appeared in 56 articles; 45% publications were by only male authors, 32% were by only female authors, and 23% were by female and male authors. This showcases a relatively balanced yet still male-dominated authorship pattern in this field.

Among the 240 articles, 179 (75%) were published in journals on (higher) education studies, 59 were published in journals with a broad scope covering social sciences research in general, two were in economics and political sciences journals. A large proportion (93%) of the articles were published in Chinese, which echoed the fact that Chinese remains the main language of publications in Chinese social sciences (Zhang, Shang, Huang, & Sivertsen, Citation2020). Most of the Chinese papers were not empirical research. In some of them, arguments were more like opinions not supported by evidence, literature, or empirical findings. This is in line with the findings of previous meta-reviews (see Section 2). This finding also reflected the overall picture of Chinese higher education studies, which focused mainly on macro-scale issues, with few empirical investigations (e.g. Li & Zhou, Citation2020). In comparison, all English-language articles reviewed drew on empirical findings, evidence, and literature to develop their arguments. As the following section will reveal, although some of the key themes appeared in both English-language and Chinese-language articles (such as multiple-logic), some other themes were discussed with more nuance in Chinese-language articles.

4. Academic discourses on the internationalisation of Chinese higher education

4.1. Definitions

Not all the publications defined ‘internationalisation’. Among those with definitions, referencing Western and English-language discourses was prevalent. Notably, the definitions of internationalisation by Knight (Citation1994, Citation1997, Citation2003), and the adapted definition by the International Association of Universities (IAU) were the most frequently cited. Such definitions appeared in 66 articles (54 in Chinese and 12 in English). The definitions formulated by Knight were often remarked as the most cited, frequently used or widely accepted (e.g. Fang, Citation2021; Wang & Ieong, Citation2019; Yang, Citation2014) or defined by an internationally renowned scholar (e.g. Meng, Citation2009; Wu & Song, Citation2018a). The IAU definition was noted as ‘a relatively authoritative definition’ used internationally (Zhou, Citation2010, p. 80). The IAU was also commonly mentioned as affiliated with UNESCO (United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation), as if it added a sense of legitimacy (e.g. Ren, Citation2017; Song & Zhu, Citation2002). Some of the other frequently cited definitions were from scholars based in the US, the UK, Canada, Australia and Western Europe.

Most of the articles adopted the aforementioned definitions without critical reflection, with only a few exceptions, including Yang (Citation2021) discussed in the Introduction section of this paper. Liu and Huang (Citation2001, p. 23) noted that the notion of internationalisation ‘was first raised by a few experts from developed countries in the West, and could have a certain degree of Western political overtones’ (政治色彩) and agendas. Mei Li (Citation2021, p. 177) and Yingqiang Zhang (Citation2021) argued that Knight’s definitions focus on the process of internationalisation at the institutional scale, with the premise that ‘internationalisation happens in a democratic and equal environment’. The authors pointed out that the definition could not fully explain the unequal power structures, or capture the tension between indigenous experiences and imported models for postcolonial countries, or explain the mutual influences among agents. Wang and Ieong (Citation2019) stressed that the definitions from the West do not consistently apply to China and ‘non-Western societies’, where ‘from the very outset, internationalisation has meant learning from the West and importing Western science and technology, with an outward look and a catch-up mentality’ (p. 347).

A few articles cited definitions by Chinese scholars or proposed their own definitions. For instance, Shousong Zhang (Citation2003, p. 15) cited Fang Gong, who argued that the IHE should have ‘academic excellence and education quality recognised and valued by other countries’; ‘outstanding talents cultivated for the world’; ‘strong research powers with a large proportion of regional and global research topics, with research outcomes that have significant international impacts’; and an open and flexible education system ‘to open to the world and exchange with other countries’. Wending Zhou (Citation2010, p. 80) reviewed previous definitions and proposed to define IHE as ‘the processes and outcomes of higher education being open and making exchanges inter-nationally’. Meanwhile, Ning Liu (Citation2015, p. 151) acknowledged the definitions by Deguang Yang, Arum and Water, Nanzhao Zhou and Shousong Zhang and further proposed the following definition:

Higher education internationalisation can be understood as the diversity of exchanges, interactions and cooperation between higher education institutions in different countries, to adapt to the globalisation of the economy and to enhance the international standard of education, aiming to cultivate for their own countries generalist talents with international awareness, international communication skills and international competitiveness. (Liu, Citation2015, p. 151)

4.2. Multiple logic

The discussions on the ICHE demonstrated four clusters of logic: educational, political, economic, and cultural. The four clusters constellated and coexisted, yet at times contradicted one another.

Two quotes are taken as an example. The first quote was in English, and the second one was in Chinese. The italic texts in the square brackets are notes made by the author of this article, to indicate the main logic manifested. The quotes showcased how the multiple logic clusters in internationalisation were often entangled.

By preparing a highly skilled labour force [economic] and promoting Chinese culture and values to the world [cultural], education is used as an important tool to facilitate China’s rise [educational and political] by improving its global economic competitiveness [economic] as well as enhancing its international influence not only in educational terms [educational] but also in economic [economic] and political terms [political]. (Wang, Citation2014, p. 24)

The so-called culture ‘going out’ strategy [cultural and political] is to carry out multi-channel, multi-form and multi-level cultural exchanges with the outside world [cultural], to participate extensively in the dialogue of world civilisations [cultural], to continuously improve the ability to spread culture internationally [cultural], to continuously develop outward-looking cultural industries [cultural and economic], and to expand the share of China’s cultural products and services in the world market [cultural and economic], so as to enhance the international community’s understanding of Chinese culture and China [cultural], enhance the international influence of Chinese culture [cultural] and China’s international discourse power (话语权, hua yu quan)Footnote1 [political], and further enhance China’s cultural soft power [cultural and political]. (Yu, Citation2012, p. 35)

Each logic cluster had diverse directions and layers. Educational logic was centred around issues on education quality, world-class universities, curriculum reform, the cultivation of students and the internationalisation of academic research. The commonly shared argument was that IHE contribute to the educational function of universities and generally improve education and research quality. Many of the studies pointed out the need for quality control in the ICHE, particularly in transnational education cooperation and international students’ education in China (e.g. Jiang, Citation2016; Wang, Citation2020).

Economic logic included two focuses. One strand focused on the global and discussed the role of universities in economic globalisation, international (education) trade, the importing and exporting of (educational) services, and competition in the international (education) market. The discussions included the need of Chinese higher education to engage in economic globalisation, as well as the benefits, challenges and risks in joining the global neoliberal competition (e.g. Xia & Zhang, Citation2004). The other strand focused on the national and highlighted how IHE could contribute to national economic development by facilitating economic modernisation, preparing internationalised human capital, generating economic benefits, and contributing to the knowledge economy. This strand also included ‘brain drain’ and ‘brain gain’ discourses and studies on returnees. Economic logic appeared in many of the studies in Chinese in the 1990s and 2000s, which corresponds the periods of China’ transformation from a state economy to a market economy (Yang, Citation2000). Many of the studies cited China’s joining the World Trade Organisation (WTO) in 2001 as a significant threshold (e.g. Liu & Huang, Citation2001; Zhang, Citation2005). Research on the WTO and ICHE reached its peak around the early 2000s then almost disappeared after 2004. This trend was also identified in the previous meta-reviews, and is an example of how research can be ‘chasing hotspots’ (Jiang et al., Citation2011; Liu, Citation2013).

Political logic manifested a similar ‘global–national’ division. One group of discussions concentrated on geopolitics, global leadership and international political battles. Some discourses were expressed with war-related phases such as ‘strategy’, ‘vanguard’ and ‘battleground’ (e.g. Yu, Citation2012, p. 35), and highlighted the need to enhance the global standing of China and Chinese higher education. The other group centred around the ideologies and political value systems in China, and expressed concerns over how IHE could challenge Chinese ideologies or be in conflict with Chinese political values. Both groups of discourses appeared in the scholarship throughout time.

Cultural logic had two seemingly conflicting starting points, in which one direction foregrounded power inequality across cultures. Challenges to Chinese (or endogenous, 本土, ben tu) cultures, traditions and values during internationalisation were discussed in 60% of the reviewed articles (145 out of 240; 137 in Chinese and eight in English). Such discourses viewed Chinese culture as valuable but under threat when facing the influx of ‘Western’ cultures and ‘(neo)-cultural colonisation’ (e.g. Liu, Citation2003, p. 130; Wu & Mao, Citation2012, p. 19). Several articles pointed out the need for ‘cultural self-awareness’ (文化自觉, wen hua zi jue) and cultural autonomy. They therefore proposed to follow the Chinese idea of he er butong (和而不同, ‘harmony without conformity’) in cultural exchanges (e.g. Li & Niu, Citation2015; Zhang, Citation2009, p. 14). Some of the studies raised questions about what ‘Chinese’ culture means and the implications of privileging Confucianism (Zheng & Kapoor, Citation2021). The other discussion direction emphasised multiculturalism and that, as part of world civilisation, Chinese culture can contribute to world civilisation on an equal basis. Such discourses argued that universities play an important role in building equal cross-cultural exchanges (e.g. Chen, Citation1998). Notably, discourses on equal cultural exchanges and power struggles can appear in the same article (e.g. Chen, Citation1998), displaying an ‘is-ought’ paradox when approaching this issue (Hume, Citation1888) – while Chinese culture is treated as inferior to Western cultures, it ought to be considered as having equal values and contributions.

Contradictions existed not only in each logic cluster but also across the different logic clusters. For instance, tension can exist between the economic logic of market competition and cultural logic of equal sharing and exchanges. However, the four sets of logic also intersected with one another. summarises the common themes under each logic cluster and under the intersections of two logic clusters. Although intersections between more than two sets of logic existed, they could not be illustrated with a two-dimensional figure simply but meaningfully. The main examples of the multiple logic are the discussions on Confucius Institutes and the Belt and Road Initiatives. Most of such discourses applied soft power and cultural diplomacy lenses, which demonstrated cultural and political logic (e.g. Zheng & Kapoor, Citation2021). Some of the studies also included educational discourses, such as quality control, and economic discourses, such as how the initiatives could expand China’s international education market and prepare a highly skilled labour force (e.g. Liu & Chen, Citation2018). In sum, the distinctions between political, economic, cultural and educational logic can be ambiguous and they can overlap.

Table 2. Key themes relevant to the educational, economic, political and cultural logic.

4.3. Multiple features

The discourses on the ICHE demonstrated four features: temporality, spatiality, affectivity and relationality. Each feature intersected with the multiple logic clusters discussed above.

4.3.1. Temporality

Temporality showcased three aspects: approaching the ICHE as having different phases, dynamics between ‘being late’ and ‘catching up’, and paradoxes between ‘fast and slow’ paces.

Several studies suggested that the ICHE underwent different historical phases. Most of the studies focused on the period of the People’s Republic of China (PRC, 1949–) and referred to the national Reform and Opening Up in 1978 as the starting point of the ICHE (e.g. Wu & Song, Citation2018b). Some of the studies explored beyond the PRC period and suggested that the ICHE started as early as the nineteenth century, during the ‘self-strengthening movement’ (洋务运动; Chen & Guo, Citation2018; Liu, Citation2015) or earlier, when ancient China’s education system and cultures influenced other countries in (South) East Asia (Jain, Citation2019; Liu, Citation2001; Wu, Citation2019; Zhang, Citation2008).

Many of the studies categorised the post-1978 period into different phases. Despite the different categorisations, they all identified a linear and upward-moving trajectory. The ICHE was depicted as changing, from learning from the West to ‘going out’, from being inward oriented to being outward oriented, and from being ‘on the periphery’ to moving to ‘the centre’ (e.g. Wu, Citation2019).

Temporality was also related to the discourses on China ‘being late’ and needing to ‘catch up’. In 47 articles, China was described as a ‘late-comer’ or ‘late mover’ (后发, hou fa) country to the IHE, with a ‘catch-up’ mentality. Behind such discourses was the unarticulated metaphor of a playing field. The discourses suggested that China should make use of its ‘late mover advantage’ to catch up and change from ‘following the run’ (跟跑, gen pao) to ‘running alongside’ (并跑, bing pa) (Liu & Li, Citation2020).

The final aspect of temporality involved the pace and speed of internationalisation. Tension between ‘fast’ and ‘slow’ was highly visible. Some of the scholarly discourses identified the fast pace of internationalisation, globalisation and economic development, and hence the need for fast and prompt ICHE adaptation (e.g. Liu & Chen, Citation2018). Meanwhile, a few articles discussed the risks of being ‘too hasty’ (操之过急, cao zhi guo ji) when ‘internationalising indigenous education, in the face of the onslaught of strong cultures’ (e.g. Liu, Citation2015, p. 153).

4.3.2. Spatiality

Spatiality in the discourses on the ICHE was manifested in five dimensions: the ‘inside-and-outside’ divide, ‘inward-and-outward’ directionality, division between internationalisation abroad and at home, ‘centre-periphery’ system of hierarchies, and duality of the ‘China-and-the-West’ imagery of the world.

The first dimension involved the division between ‘inside’ and ‘outside’. What divided the inside from the outside? Here, the national border is an important notion in not only the material sense but also imaginaries. The phrase ‘gate of the country’ (国门, guo men) was used in 54 Chinese-language articles. The notion originated from Imperial China, when each country and city was surrounded by city walls, and the gate connected such countries/cities to the outside world. The gate would be closed for protection against external threats and open for business, people’s mobility and the expansion of the realm.

In the discourses that mentioned this notion, internationalisation was depicted as ‘opening the gate of the country’ (打开国门, da kai guo men) or ‘going out of the gate of the country’ (走出国门, zou chu guo men) and ‘moving towards the world’ (走向世界, zou xiang shi jie). As noted, the world was perceived as space out there. The other metaphorical spaces out there included the tide, trend and track of internationalisation that cannot be resisted. Such discourses suggested that China should join the trend and ‘ride the tide’ (e.g. Feng, Citation2003). The literature also frequently noted a ‘track’ outside China, which is seen as important, universal and must be connected to. The need was expressed by the metaphorical phrase ‘to connect tracks’ (接轨, jie gui) in 106 articles, meaning to converge with the pathways and trends outside China.

Spatiality also showed directionality. Some of the discourses on the ICHE followed a division between ‘inward-outward’ orientations (e.g. Wu, Citation2019), and many highlighted the importance of having not only one-directional ‘bringing in’ (引进来, yin jin lai) but also two-directional ‘going out’ (走出去, zou chu qu), which may lead to ‘win-win situations’ (e.g. Liu & Zhang, Citation2020).

Although the idea of ‘internationalisation at home’ first appeared in the late 1990s, it was not until recently that discourses on ‘internationalisation at home’ in the ICHE began to emerge (Fang, Citation2021). By distinguishing internationalisation at home from internationalisation abroad, such discourses emphasised that internationalisation need not happen out there, which seems highly relevant in the post-COVID-19 period (Zhang & Jiang, Citation2020).

The global space was perceived to be stratified and hierarchical. Several studies used the ‘centre-periphery’ framework and positioned China as moving from the ‘periphery’ to the ‘centre’ (e.g. Zheng & Yan, Citation2021). Such discourses typically intersected with the relationality dimension and followed political and cultural logic to discuss power paradigms and shifts.

The final feature of spatiality was the division between China and the ‘West’ and the imagination of the West representing the rest of the world. The ‘West’; ‘Western’ countries, systems and cultures; or ‘Westernisation’ were discussed in 144 of the 224 Chinese articles and 14 of the 16 English articles. In many of the articles, the ‘West’ was used to refer to the foreign, non-Chinese and non-Eastern world, though the actual non-Chinese and non-Eastern world is much larger than the ‘West’. The ‘West’ was depicted as ‘developed’, ‘advanced’ and ‘strong’, which can be learnt from, but also demonstrating ‘(cultural) hegemony’, ‘Western centrism’ and ‘linguistic advantages’, which other countries should be cautious against (e.g. Zhang, Citation2009). Most of the research discussed how the ICHE was shaped by Westernisation and how internationalisation should not be equal to Westernisation, which can lead to neo-colonisation. Finding a balance between the West and China, international and national, and global and indigenous was a recurring theme. In the recent discourses relevant to the Belt and Road Initiative, the non-Chinese and non-Western parts of the world, such as Africa, received some research attention.

4.3.3. Affectivity

Although research can be ‘implicitly seen as emotionally detached, rational and objective’, a growing body of literature pointed out the need to use the affective lens for research and analysis (e.g. Guo, Citation2020; Kenway & Fahey, Citation2011, p. 187; Shahjahan, Sonneveldt, Estera, & Bae, Citation2020). This systematic review found that many of the articles were charged with affective language, expressions and metaphors. China, Chinese higher education, Chinese culture, and Chinese higher education institutions were personified as having agency and feelings. Such affective concepts largely fell on a spectrum ranging from negativity to positivity.

Negative emotions were related to being passive and lacking agency, including ‘passive’, ‘concerned’, ‘anxious’, ‘cautious’, ‘wary’, ‘self-abased’, ‘inferior’, ‘fear’, ‘vigilant’, ‘low self-esteem’, ‘grief’, ‘powerless’, ‘insecure’, ‘confused’ and ‘distrust’. Affectivity was also temporal. Most negative emotions were linked with past traumas and a sense of nostalgia, coupled with fear of the future. Worries and cautiousness were often attributed to the collective ‘anxiety of modernity’, dread of losing autonomy, concern over Westernisation and colonisation in the political, economic, cultural and educational sense, as well as other undesirable consequences of internationalisation (Chen, Citation2018; Liu & Li, Citation2020). According to Yeh (Citation2017):

The one-sided ‘internationalisation’ with only ‘identifying’ the Western knowledge system manifests an amnesia of historical and cultural contexts. It is a natural reflection of a cultural inferiority complex, as a result of being emptied of self-confidence due to long-term historical trauma. (p. 84)

Positive emotions were associated with agency, proactivity, love, national pride, and responsibility for humankind, including ‘proactive’, ‘(self-) confident’, ‘proud’, ‘love the country’,Footnote2 ‘responsible’, ‘(national) pride’ and ‘sense of responsibility’. Such positive emotions were often future-oriented and expressed as aspirations, desires, hope and longing for alternative futures. Such discourses were mostly raised as counterpoints to negative affectivity and highlighted what should be done. For example, the ICHE should be proactive rather than passive, Chinese higher education (institutions) should strengthen cultural confidence rather than feeling inferior, Chinese civilisations should ‘rejuvenate’ and enhance ‘national pride’, and Chinese higher education should be responsible as it develops into ‘a strong country in education’ (教育强国, jiao yu qiang guo) (e.g. Liu & Chen, Citation2018).

4.3.4. Relationality

The discourses on the ICHE addressed two types of relationships. One strand of discourses focused on competition and relevant concepts such as rivalry, battles, wars and colonisation. The other strand of discussions centred on cooperation, collaboration, partnership, friendship; a community with a shared future for humankind; the world as a family; and dialogues across civilisations. The two directions of expressions are not mutually exclusive and may exist in one article. They were also coupled with economic, political, cultural and educational logic in the different articles.

All the discussions on relationality acknowledged that differences exist across nations, and certain value chains exist within the internationalisation process. Many of the studies expressed critical reflections on how Western, foreign, international and global sciences and technologies can be perceived as having more value than Chinese, national, local, indigenous, humanities and social sciences in the ICHE (e.g. Ma & Tian, Citation2017). ‘Value’ was referred to as educational, cultural, economic and political in different discourses.

The discourses on competition were built on an ontological understanding of global higher education as a battlefield of limited resources, where zero-sum competition is unavoidable. The competition discourses focused on Western hegemony within global higher education (several discourses applied the ‘centre-periphery’ model; see Liu, Citation2008). They see differences as immiscible and the value chain as static. In contrast, the discourses on internationalisation being collaborative and can be equal dialogues were built on an ontological understanding of the world as an open space with potential for equality. They align with ideas of ‘the community of a shared future for humankind’ and building on normative appeals for he er bu tong (harmony without conformity), from not only the cultural but also economic, political and educational perspectives (e.g. Jin, Citation2008).

5. Discussions and conclusion

5.1. ‘Chinese characteristics’ of internationalisation

The review of the literature on the ICHE revealed the prevalence of defining internationalisation with Western discourses, coupled with attempts to create alternative definitions. The discourses on the ICHE were grounded in multiple logic clusters, namely, educational, economic, political, and cultural, and showcased temporal, spatial, affective and relational features.

The multiple logic clusters in the academic discourses reflected the multifaceted reality of the ICHE. For instance, Lo and Pan (Citation2021) conceptualised the ‘Chinese characteristics’ of the IHE as:

Party-state-centrism, authoritarianism, diplomatisation, cultural hybridity, economisation, techno-nationalism, catch-up mentality, and strategy-oriented differentiation. These features are multi-dimensional and multi-faceted, but incoherent, inconsistent, and conflict-prone. (p. 240)

Thus, some of the studies proposed using multiple lenses to investigate and understand the ICHE (H. Xu, Citation2006). Research on the IHE also identified the need to understand internationalisation ‘as a multi-faceted and complex assemblage of practices in which multiple intentions and ideas are interwoven with particular economic, political, social and cultural concerns with shift over time and space’ (Bamberger, Morris, & Yemini, Citation2019, p. 212).

This review further proposed that the ICHE was about not only education, research and knowledge; political, diplomatic and ideological powers; international markets, cross-border educational services, economic development, the labour market and neoliberal competition; and cultural colonisation, hegemony, communication and exchanges. The ICHE is about all of them.

The analysis also revealed that ICHE was by no means a neutral or natural process. Rather, it was infused with power tensions between internationalisation, Westernisation, (neo)-colonisation and indigenisation/endogenisation. This echoes previous research, which identified various degrees of Westernisation and indigenisation/endogenisation in Chinese higher education (Wang, Sung, & Vong, Citation2021; Yang, Citation2014). Although previous research suggested the dominance of Western imprints and influences in ICHE, this article argues that ICHE is never entirely Westernisation. An example is that, as noted, the urges for valuing Chinese cultures and treating Chinese higher education as equal contributors to world civilisations persist in the academic discourse on ICHE.

The hybridity of the diverse and occasionally conflicting logics, as well as the long-standing power struggles formed the ‘Chinese characteristics’ of ICHE and relevant discourses. Some of these characteristics were shared with other contexts. For instance, the neoliberal and economic logic is also dominant in many countries’ IHE and discourses on IHE (Stier, Citation2004; Vavrus & Pekol, Citation2018).

However, the political and cultural logic clusters seemed to be the specific focuses in the Chinese context. In particular, the affective dimension relevant to such discourses is worth noting. Affect was not only experienced and expressed individually but also constructed collectively based on social, cultural, political and ethical conditions (Ahmed, Citation2007; Zembylas, Citation2022). In addition, affect is temporal. Collective memories and post-memories (Hirsch, Citation1992) of China’s past played an important role in the ICHE discourses. Post-memories (Hirsch, Citation1992) refer to memories of events not experienced first-hand but inherited from past generations through continuing narratives, artefacts and behaviours.

Memories and post-memories of China’s engagement with the world have three main clusters. The first cluster is the ‘chosen glories’ of the 5000-year-old Chinese civilisation as the ‘Central Kingdom’ within tianxia (literal translation is ‘all under heaven’, meaning the world) (Carrai, Citation2021). The second cluster includes ‘chosen trauma’ of the Century of (National) Humiliation (百年国耻, bai nian guo chi) under Western colonisation and Japanese incursions since the 1800s (Carrai, Citation2021; Li & Niu, Citation2015; Wang, Citation2008), as well as the later Cold War periods when China was isolated from ‘the western bloc’ (Yang, Citation2000, p. 325). The third cluster is the living (post-) memories of China’s re-opening to the world since the late 1970s, and subsequent successes and geopolitical tensions. In addition, some ‘chosen amnesia’ of certain periods of Chinese history shaped how the collective memories were constructed (Carrai, Citation2021, p. 9). The ‘chosen’ attribute emphasised that such collective memories and post-memories were party–state mandated and politically constructed (Carrai, Citation2021; Hubbert, Citation2022).

The post-memories of past glories and trauma led to a collective sense of nostalgia and sense of victimisation. They were related to the prevailing passive emotions regarding the ‘West’ and longing for rejuvenation in the discourses on ICHE. Hubbert (Citation2022) argued that in contemporary China, collective nostalgia is ‘about winning the hearts and minds of local and global populations through glorifying a romanticised past that offered ostensibly alternative forms of modernity’ (p. 50). Confucius Institutes are among such examples (Hubbert, Citation2019). Wang (Citation2008) found that since the early 1990s, the ‘victimisation narrative’ has replaced the previous Maoist ‘victor narrative’ in China. The former tends to ‘blames the West’, and emphasised the legitimacy of the Chinese Communist Party as the one ‘restored national unity and practical independence’ (p. 792).

Similar political narratives have persisted in Xi Jinping’s China since the 2010s. One example is the frequently used term ‘the great struggle’ (伟大斗争, wei da dou zheng; can also be translated as ‘the great fight’), which emphasised external threats and conveyed a message to confront Western pressures or ‘bullies’ (Li & Wang, Citation2022). Another example is the narrative of ‘rejuvenating China’ (振兴中华, zhen xing zhong hua) and ‘the great rejuvenation’ (伟大复兴, wei da fu xing). Such political discourses stemmed from the 1980s and were rephased as the ‘China dream of great rejuvenation’ (伟大复兴的中国梦, wei da fu xing de zhong guo meng) in Xi’s China (Carrai, Citation2021; Wang, Citation2008), which linked the past to the future based on ‘nostalgic futurology’ (Callahan, cited in Carrai, Citation2021).

As discussed in the previous sections, the same expressions and similar sentiments were found in many of the academic discourses on the ICHE. Although the previous meta-reviews identified the close association between the research topics and national policy changes in China (e.g. Dong et al., Citation2021), this review further revealed how political narratives, geopolitical agendas, and collective affectivity could creep into and shape the academic discourses in Chinese higher education studies.

5.2. Future research on ICHE

This article concludes with a reflection on four common sets of dichotomies and one myth found in the existing discourses, and proposes thoughts about future research on ICHE.

The first dichotomy is between empirical research and theoretical/conceptual research. The findings of this review are in line with those of previous meta-reviews, that few empirical studies exist in the Chinese literature, despite the recent increase in empirical research. Many of the previous meta-reviews called for increased empirical research examining meso- and micro-scales. This article agrees with previous meta-reviews on the need for diversified focuses at different scales. This article also echoes previous meta-reviews’ findings that there are repetitive arguments in Chinese-language literature, and that arguments in some of the Chinese-language articles were not well-supported by evidence. This is rarely the case in English-language articles reviewed. Therefore, this article joins previous meta-reviews in proposing that future research in Chinese language should further enhance academic rigour.

However, previous meta-reviews’ arguments on ‘a lack of empirical research’ and calls to move from conceptual to empirical studies are problematic. Firstly, empirical research and theoretical research are not mutually exclusive, and the development of one type of research does not stop the other from growing. Furthermore, the ideas implied that empirical research, perceived to be more commonly used in ‘international/Western/English-language’ research, bore more academic rigour and value than conceptual research. This notion is highly debatable, considering ‘Western’ hegemony in the research paradigms and the fact that the higher education studies in English were found to suffer from a ‘theory deficit’ (Hamann & Kosmützky, Citation2021).

Finally, the arguments undervalued the conceptual contributions of Chinese research. They risk falling back into ‘academic colonisation’ many of the studies were critical of. This article has revealed the prevalent use of ‘Western’ definitions of ‘internationalisation’, which does not fit the Chinese context properly. Existing attempts to define internationalisation from Chinese perspectives also have limitation. In this context, we need not only more empirical studies about ICHE, but also solid conceptual work to develop Chinese definitions on higher education internationalisation. Otherwise, the field of the ICHE may continue to suffer from ‘academic colonisation’, in which Chinese research only provides data to feed in ‘Western’ theoretical developments. There are potentials to develop Chinese definitions of IHE. During the review, I have encountered several Chinese articles with original and critical perspectives not fully captured in the English-language scholarships. One important example is about the concept of he er bu tong, and its potentials for internationalisation with respect and equality. Such discussions appeared largely in Chinese-language articles, but have potential for further development in both Chinese and English-language scholarships.

Critical, original and endogenous conceptual work from the Chinese perspective would benefit not only ICHE research but also IHE research. Among the English articles analysed in this review, few engaged with substantial bodies of literature in Chinese, despite their focus on Chinese higher education and the existence of numerous studies on the topic published in Chinese. Therefore, this article argues that for future research on Chinese higher education in English, it would be beneficial to move beyond the English-language silos to acknowledge and engage with the literature in Chinese.

The second dichotomy is between China and the West. Despite the dominance of the discourses on the ‘West’ and ‘Westernisation’, they largely followed the imagination of the world as a binary form mainly including ‘China and the West’. As discussed previously, though most of the discourses proposed that in practice, internationalisation should not be Westernisation; in such academic discourses, the foreign, non-Chinese and non-Eastern parts of the world were often referred to as the ‘West(ern)’.

The focus on the West can be explained through the historical, affective and political lenses discussed in the previous section. As noted, the West has been historically acting as a threat and reference point, creating not only senses of threats and victimisation, but also longing and aspiration. Contemporary political narratives such as ‘the great fight’ (with the West) reinforces the importance of Western existence and the need to constantly pay attention to the West. In general, there exists a dual-perception of the ‘West’: the West is both hegemonic and threatening powers that created damage and need to be cautious of, as well as models that have left imprints and still need to learn from or collaborate with (Marginson & Xu, Citation2022).

Another important note is that the ‘West’ is a loaded, constructed, and debatable concept (Hall, Citation1992). In all the literature reviewed in this article, ‘the West’ is often used as a homogenous entity. However, heterogeneity exists within the ‘Western’ bloc. For instance, different degrees of ‘Whiteness’ and relevant hierarchies of hegemonies exist across Western and global higher education, which are based on not simply ethnicity, but more importantly other elements like culture, language, and history (Shahjahan & Edwards, Citation2021). This creates different implications on ICHE. Therefore, future research may benefit from further critical reflections on the construction of ‘the West’ in ICHE and their implications.

The world is not binary, the ‘non-Chinese’ and foreign parts are not only the ‘West’. This article joins some previous meta-reviews, and proposes that future research may benefit from moving beyond the pairing of ‘China and the West’. This means not only the broadening of research scope to other contexts, but most important, an ontological shift in imagining the world beyond the binary construction of China and the West. Some studies identified in this review, such as those on the Belt and Road Initiatives, have begun researching more about Africa in ICHE. Some previous research has also pointed out the need to further explore higher education cooperation between China, Africa, and ASEAN countries (Hayhoe, Citation2017). Furthermore, future research on foreign theories can extend the epistemological and conceptual scope beyond Western theories. Jun Li’s (Citation2021) work on the synergies between Confucian values and Ubuntu values in international educational development is an illustrative example.

The third dichotomy is between the global and national. Similar to research on internationalisation in other contexts, most of the discourses on the ICHE followed a binary spatial positioning of the global and national. Such discourses mainly argued the existence of a world out there for China to engage with through internationalisation, and that internationalisation is a (passive) ‘response’ to globalisation. However, the national intersects with the global and shapes the global through its engagements. Following the critical reflection on spatiality in higher education (Marginson, Citation2022; Massey, Citation2005; Matus & Talburt, Citation2009), this study invites future research on ICHE to move beyond the binary positioning of the national and global. This could mean shifting the perception of China being ‘outside’ a fixed world that it needs to ‘connect tracks’ with, to understanding China as part of the world it already shapes. In this perception, the local and national are not isolated from the global, nor are they inferior to the global. Synergies between indigenisation and internationalisation then become possible.

The fourth dichotomy is between the ‘centre and periphery’. As noted, many of the discourses applied this lens and positioned China as moving away from ‘the periphery’ towards ‘the centre’. However, the positionality of China under the centre-periphery framework is questionable. If sticking to the framework, on which basis can one meaningfully judge the position of China? More importantly, the centre-periphery framework cannot fully grasp the dynamics of global higher education and research, and it radically underestimates the agency of non-hegemonic powers (see Marginson & Xu, Citation2023). Other approaches to explain, understand and imagine global higher education and research exist. For instance, injustice and unequal power relations can be explained through the lens of cultural hegemony (Gramsci, Citation1971), where multiple hegemonic powers can co-exist and the agency of various parties are not denied. In addition, if imagining the world through ‘the ecology of knowledges’ (de Sousa Santos, Citation2007), one may better understand and facilitate the co-presence of diverse knowledges – such as the local and global knowledges – as well as the interdependence between them.

The final comment concerns the myth about the linear development of internationalisation. As discussed, most the studies that examined the temporality of the ICHE associated it with a linear progress trajectory. However, this linear assumption ignores the oscillations, stepping back and circular movements in internationalisation (e.g. X. Xu, Citation2021). For future research with temporal dimensions, it could be helpful to distinguish between the seemingly linear passing of time and the complexity of the trajectories through time.

Acknowledgements

The author sincerely thanks Dr William Yat Wai Lo and the two anonymous reviewers, as well as Professor Simon Marginson, for their kind support and constructive review comments. Some findings of this study were presented at a University of Oxford China Centre Mandarin seminar. The author also thanks the seminar organiser and audience for their questions and feedback.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1 The original Chinese term 话语权 (hua yu quan) can be translated in English as ‘discourse power’ or ‘right to speak’, but neither fully captures its nuance (see Friedman, Citation2022). It is translated in this study as ‘discourse power’ based on the author’s interpretation.

2 The original Chinese phrase was 爱国 (ai guo). It was not translated as ‘patriotism’ or ‘nationalism’, as such words do not reflect the historical, political and cultural textures of the original Chinese term (see Guo, Citation2020).

References

- Ahmed, S. (2007). The cultural politics of emotion (2nd ed.). Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

- Bacchi, C. (2000). Policy as discourse: What does it mean? Where does it get us? Discourse, 21(1), 45–57. doi:10.1080/01596300050005493

- Bamberger, A., Morris, P., & Yemini, M. (2019). Neoliberalism, internationalisation and higher education: Connections, contradictions and alternatives. Discourse: Studies in the Cultural Politics of Education, 40(2), 203–216. doi:10.1080/01596306.2019.1569879

- Bedenlier, S., Kondakci, Y., & Zawacki-Richter, O. (2018). Two decades of research into the internationalization of higher education: Major themes in the Journal of Studies in International Education (1997–2016). Journal of Studies in International Education, 22(2), 108–135. doi:10.1177/1028315317710093

- Brandenburg, U., & De Wit, H. (2015). The end of internationalization. International Higher Education, 62, 15–17. doi:10.6017/ihe.2011.62.8533

- Cai, J., Zhu, Z., & Xiong, J. (2020). 新中国成立70周年高等教育国际化研究的可视化分析 [Visualization analysis of China’s higher education internationalization research over the past 70 years]. Forum of Contemporary Education, 296(2), 14–30. doi:10.13694/j.cnki.ddjylt.20200211.002

- Carrai, M. A. (2021). Chinese political nostalgia and Xi Jinping’s dream of great rejuvenation. International Journal of Asian Studies, 18(1), 7–25. doi:10.1017/S1479591420000406

- Chen, B., & Guo, L. (2018). 一带一路”建设背景下我国高等教育国际化的转型与升级 [The transformation and upgrading of higher education internationalization in China under the background of ‘the Belt and Road’ construction]. Journal of National Academy of Education Administration, 3, 9–15.

- Chen, C. (1998). 国际合作:高等学校的第四职能——兼论中国高等教育的国际化 [International collaboration: The fourth function of higher education institutions – discussions on the internationalisation of Chinese higher education]. Journal of Higher Education, 5, 11–15.

- Chen, X. (2018). 焦虑、认同与中国高等教育现代化 [Anxiety, identity and the modernization of higher education in China]. Educational Development Research, 38(23), 1–8.

- de Sousa Santos, B. (2007). Beyond abyssal thinking: From global lines to ecologies of knowledges. Review, 30(1), 45–89. doi:10.4324/9781315634876-14

- Dong, W., Dong, S., & Zhang, Y. (2021). 我国高等教育国际化领域研究主题识别与演化特征分析 [An analysis of identification and evolution characteristics of research topics in the internationalization of higher education in China: A perspective based on text mining]. Theory and Practice of Education, 41(36), 3–7.

- Fang, Y. (2021). ‘在地国际化’之‘旧’与‘新’:学理思考及启示 [The ‘old’ and ‘new’ respects of internationalization at home: The rational thinking and the enlightenment to our country. Jiangsu Higher Education, 8, 41–45.

- Feng, J. (2003). 论全球化背景下我国高等教育的国际化 [On the internationalization of China’s higher education with the background of globalization]. China Soft Science Magazine, 1, 27–32.

- Foucault, M. (1980). Power/knowledge: Selected interviews and other writings, 1972–1977. New York: Pantheon Books.

- Friedman, T. (2022). Lexicon: ‘Discourse power’ or the ‘right to speak’ (话语权, Huàyŭ Quán). DigiChina. https://digichina.stanford.edu/work/lexicon-discourse-power-or-the-right-to-speak-huayu-quan/

- Gramsci, A. (1971). Selections from the prison notebooks. London: Lawrence and Wishart.

- Guo, T. (2020). Politics of love: Love as a religious and political discourse in modern China through the lens of political leaders. Critical Research on Religion, 8(1), 39–52. doi:10.1177/2050303219874366

- Hall, S. (1992). The west and the rest: Discourse and power. In S. Hall & B. Gieben (Eds.), Formations of modernity (pp. 275–332). Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Hamann, J., & Kosmützky, A. (2021). Does higher education research have a theory deficit? Explorations on theory work. European Journal of Higher Education, 11(S1), 468–488. doi:10.1080/21568235.2021.2003715

- Hayhoe, R. (2017). China in the center: What will it mean for global education? Frontiers of Education in China, 12(1), 3–28. doi:10.3868/s110-006-017-0002-8

- Hirsch, M. (1992). Family pictures: Maus, mourning, and post-memory. Discourse, 15(2), 3–29.

- Hong, S., & Zhang, L. (2020). 高等教育国际化研究的现实脉络与演进逻辑——基于WOS 数据库的实证研究 [Development trends and logics of the research on higher education internationalisation: An empirical study based on WOS database]. Higher Education Exploration, 5, 120–128.

- Hubbert, J. (2019). China in the world: An anthropology of Confucius Institutes, soft power, and globalization. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press.

- Hubbert, J. (2022). On nostalgia and returns. Made in China Journal, 7(1), 46–51. doi:10.1136/bmj.320.7235.657/a

- Hume, D. (1888). A treatise of human nature. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- Jain, R. (2019). The tightening ideational regimentation of China’s higher education system. Economic and Political Weekly, 54(30), 55–63.

- Jiang, J. (2016). 我国高等教育“走出去”的若干对策研究 [Research on the measures of ‘going abroad’ of higher education in China]. Theory and Practice of Education, 36(3), 3–5.

- Jiang, W., Su, J., & Cui, Q. (2011). 十年来高等教育国际化研究述评——以2001–2010年CNKI数据库为本的统计分析 [A review of the research on higher education internationalisation in the past decade: Statistical analysis of publications in CNKI database in 2001–2010]. Higher Education Exploration, 4, 146–149.

- Jin, L. (2008). 和而不同:面对高等教育国际化的精神立场 [He er butong: A conceptual standpoint when facing higher education internationalisation]. Modern Education Science, 3, 24–27 + 31.

- Kenway, J., & Fahey, J. (2011). Getting emotional about ‘brain mobility’. Emotion, Space and Society, 4(3), 187–194. doi:10.1016/j.emospa.2010.07.003

- Knight, J. (1994). Internationalization: Elements and checkpoints. CBIE Research No. 7. In Canadian Bureau for International Education (CBIE)/Bureau canadien de l’éducation internationale (BCEI) (Vol. 7). Canadian Bureau for International Education Research. Retrieved from http://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED549823.pdf

- Knight, J. (1997). Internationalisation of higher education in Asia Pacific countries – chapter 1. Amsterdam: European Association for International Education.

- Knight, J. (1999). A time of turbulence and transformation for internationalization. CBIE Research, 14.

- Knight, J. (2003). Updating the definition of internationalization. International Higher Education, 33, 2–3.

- Kosmützky, A., & Putty, R. (2016). Transcending borders and traversing boundaries: A systematic review of the literature on transnational, offshore, cross-border, and borderless higher education. Journal of Studies in International Education, 20(1), 8–33. doi:10.1177/1028315315604719

- Lee, J. J., & Stensaker, B. (2021). Research on internationalisation and globalisation in higher education – reflections on historical paths, current perspectives and future possibilities. European Journal of Education, 56(2), 157–168. doi:10.1111/ejed.12448

- Li, J. (2021). China’s humanistic Zhong-Yong approach to educational partnerships for international development in Post-Covid-19: Confucian and Ubuntu perspectives on Confucius Institutes and classrooms in Africa. Bandung: Journal of the Global South, 8, 251–269.

- Li, J., & Xue, E. (2022). New directions towards internationalization of higher education in China during post-COVID 19: A systematic literature review. Educational Philosophy and Theory, 54(6), 812–821. doi:10.1080/00131857.2021.1941866

- Li, J., & Zhou, Y. (2020). 论高等教育研究的“中国模式 [The ‘Chinese model’ in higher education research]. Journal of Higher Education, 41(3), 61–67.

- Li, M. (2021). 全球化新变局与高等教育国际化的中国道路 [New changes in globalisation and China’s path to higher education internationalisation]. Peking University Education Review, 19(1), 173–188.

- Li, S., & Pan, M. (1992). 中国高等教育的地方化与国际化 [The localisation and internationalisation of Chinese higher education]. Higher Education Exploration, 3, 11–16.

- Li, X., & Niu, J. (2015). 高等教育国际化的本质与内涵:文化流的视角 [Essence and connotations of higher education internationalisation: The perspectives of cultural flows]. Higher Education Exploration, 11, 36–41.

- Li, Z., & Wang, Q. (2022). The radicalization of China’s global posture: Narratives and strategies. In S. Hua (Ed.), The political logic of the US-China trade war (pp. 127–146). Lanham: Lexington Books.

- Liu, F. (2013). 高等教育国际化相关问题研究综述 [A review of research on higher education internationalisation]. Heilongjiang Research on Higher Education, 231(7), 8–11.

- Liu, H. (2001). 高等教育的国际化与本土化 [The internationalisation and indigenisation of higher education]. China Higher Education, 2, 22–23+29.

- Liu, H., Yang, R., & Ni, S. (2020). 国内外高等教育国际化研究的对比分析——基于 CiteSpace可视化知识图谱的应用 [A comparative analysis of higher education internationalization research at home and abroad: Based on the application of CiteSpace visualization knowledge graph]. Modern Educational Technology, 30(12), 48–54.

- Liu, J. (2008). 高等教育的依附发展与学术殖民 [On dependence development and academic colonization of higher education]. Journal of Higher Education, 29(12), 8–11.

- Liu, J., & Chen, J. (2018). 改革开放40年: 面向“一带一路”的高等教育国际化转向 [The Belt and Road Initiative and the internationalization of higher education]. Journal of Hebei Normal University / Educational Science Edition, 20(5), 62–67.

- Liu, J., & Huang, M. (2001). 试论我国高等教育的国际化 [Tentative discussions on the internationalisation of higher education in our country]. China Higher Education Research, 2, 25–27.

- Liu, K. (2003). 国际化:中国高等教育回顾与展望 [Internationalisation: Reviews and prospects of China’s higher education]. Educational Development Research, 5, 128–130.

- Liu, N. (2015). 高等教育国际化与本土化关系研究 [Research on higher education internationalisation and indigenisation]. Social Sciences in Xinjiang, 6, 151–153.

- Liu, Y. (2018). 高等教育国际化研究评介——基于WOS数据库的统计分析 [Review of the research on higher education internationalisation: An analysis based on WOS database]. Higher Education Exploration, 2, 119–128.

- Liu, Y., & Li, X. (2020). 消解中国高等教育现代性焦虑并重塑文化认同 [Dispelling the anxiety of modernity of Chinese higher education and reshaping its cultural identity]. Heilongjiang Researches on Higher Education, 38(11), 16–20.

- Liu, Y., & Zhang, Y. (2020). “一带一路”倡议与中国高等教育国际化的新图景 [The Belt and Road Initiative and new vision of internationalization of higher education in China]. Tsinghua Journal of Education, 41(4), 81–87.

- Lo, T. Y. J., & Pan, S. (2021). The internationalisation of China’s higher education: Soft power with ‘Chinese characteristics’. Comparative Education, 57(2), 227–246. doi:10.1080/03050068.2020.1812235

- Ma, J., & Cai, J. (2016). 教育国际化领域的研究进展与趋势 ——基于WoS期刊文献的可视化分析 [The research progress and trend in educational internationalization field: Based on the visual analysis of journal articles of WoS]. Studies in Foreign Education, 43(316), 3–17.

- Ma, J., & Tian, J. (2017). 高等教育国际化的主要特征——基于高等教育经济属性和文化属性的分析 [The main characteristics of higher education internationalization: Based on the analysis of higher education’s economic property and culture property]. International and Comparative Education, 39(5), 44–52.

- Marginson, S. (2009). The academic professions in the global era. In J. Enders & E. de Weert (Eds.), The changing face of academic life (pp. 96–113). Palgrave Macmillan. doi:10.1057/9780230242166_6

- Marginson, S. (2022). Is the idea wrong or is the fault in reality? Once more on the definition of ‘internationalisation’ of higher education. Unpublished manuscript, shared by the author.

- Marginson, S., & Xu, X. (2022). The ensemble of diverse music: Internationalisation strategies and endogenous agendas in East Asian higher education. In S. Marginson & X. Xu (Eds.), Changing higher education in East Asia (pp. 1–30). London: Bloomsbury.

- Marginson, S., & Xu, X. (2023). Hegemony and inequality in global science: Problems of the center-periphery model. Comparative Education Review, 67(1). doi:10.1086/722760

- Massey, D. B. (2005). For space. London: SAGE Publications.

- Matus, C., & Talburt, S. (2009). Spatial imaginaries: Universities, internationalization, and feminist geographies. Discourse, 30(4), 515–527. doi:10.1080/01596300903237271

- Meng, Z. (2009). 高等教育国际化的动因及其反思 [Drivers of higher education internationalisation and its reflections]. Modern Education Management, 7, 16–19.

- Mittelmeier, J., & Yang, Y. (2022). The role of internationalisation in 40 years of higher education research: Major themes from higher education research and development (1982–2020). Higher Education Research and Development, 41(1), 75–91. doi:10.1080/07294360.2021.2002272

- Mongeon, P., & Paul-Hus, A. (2016). The journal coverage of Web of Science and Scopus: A comparative analysis. Scientometrics, 106(1), 213–228. doi:10.1007/s11192-015-1765-5

- Mwangi, C. A., Latafat, S., Hammond, S., Kommers, S., Thoma, H., Berger, J., & Blanco-Ramirez, G. (2018). Criticality in international higher education research: A critical discourse analysis of higher education journals. Higher Education, 76(6), 1091–1107. doi:10.1007/s10734-018-0259-9

- Page, M. J., McKenzie, J. E., Bossuyt, P. M., Boutron, I., Hoffmann, T. C., Mulrow, C. D., … Moher, D. (2021). The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ, 372, n71. doi:10.1136/bmj.n71

- Pashby, K., & de Oliveira Andreotti, V. (2016). Ethical internationalisation in higher education: Interfaces with international development and sustainability. Environmental Education Research, 22(6), 771–787. doi:10.1080/13504622.2016.1201789

- Ren, Y. (2017). 高等教育国际化的人文价值取向研究 [Researach on the humanistic value approaches to higher education internationalisation]. Zhonghua Wenhua Luntan, 12, 154–157.

- Shahjahan, R. A., & Edwards, K. T. (2021). Whiteness as futurity and globalization of higher education. Higher Education. doi:10.1007/s10734-021-00702-x

- Shahjahan, R. A., Sonneveldt, E. L., Estera, A. L., & Bae, S. (2020). Emoscapes and commercial university rankers: The role of affect in global higher education policy. Critical Studies in Education, 63(3), 275–290. doi:10.1080/17508487.2020.1748078

- Shengli, L. (2014). 《中文核心期刊要目总览》和CSSCI来源期刊目录比较研究 [A comparative study on a guide to the core journals of China and Chinese Social Sciences Citation Index]. Journal of Library and Information Sciences in Agriculture, 26(10), 93–97.

- Song, W., & Zhu, Y. (2002). 21世纪中国高等教育国际化的思考 [Reflections on the internationalisation of Chinese higher education in the 21st century]. Higher Education of Sciences, 4, 1–6.

- Stein, S. (2021). Critical internationalization studies at an impasse: Making space for complexity, uncertainty, and complicity in a time of global challenges. Studies in Higher Education, 46(9), 1771–1784. doi:10.1080/03075079.2019.1704722

- Stier, J. (2004). Taking a critical stance toward internationalization ideologies in higher education: idealism, instrumentalism and educationalism. Globalisation, Societies and Education, 2(1), 1–28. doi:10.1080/1476772042000177069

- Tight, M. (2021). Globalization and internationalization as frameworks for higher education research. Research Papers in Education, 36(1), 52–74. doi:10.1080/02671522.2019.1633560

- Tight, M. (2022). Internationalisation of higher education beyond the west: Challenges and opportunities: The research evidence. Educational Research and Evaluation, 27(3–4), 239–259. doi:10.1080/13803611.2022.2041853

- Vavrus, F., & Pekol, A. (2018). Critical internationalization: Moving from theory to practice. FIRE: Forum for International Research in Education, 2(2). doi:10.18275/fire201502021036

- Wang, L. (2014). Internationalization with Chinese characteristics. Chinese Education & Society, 47(1), 7–26. doi:10.2753/CED1061-1932470101

- Wang, Y. (2020). 后疫情时代教育国际化三题 [On three themes of internationalization of education in the post-pandemic era in China]. International and Comparative Education, 42(9), 8–13.

- Wang, Y., & Ieong, S. L. (2019). Will globalized higher education embrace diversity in China? Frontiers of Education in China, 14(3), 339–363. doi:10.1007/s11516-019-0018-4

- Wang, Y., Sung, M.-C., & Vong, K.-I. P. (2021). The global v the local: Knowledge construction and building western university with Chinese/local characteristics. International Journal of Educational Research, 109. doi:10.1016/j.ijer.2021.101835

- Wang, Z. (2008). National humiliation, history education, and the politics of historical memory: Patriotic education campaign in China. International Studies Quarterly, 52(4), 783–806. doi:10.1111/j.1468-2478.2008.00526.x

- Wu, C., & Song, Y. (2018a). 高等教育国际化内涵式发展的依据、维度及实现路径 [On the basis, dimensions and approaches to the connotative development of the internationalization of higher education]. China Higher Education Research, 8, 17–22.

- Wu, C., & Song, Y. (2018b). 改革开放40年来我国高等教育国际化发展的变迁与展望 [The changes and prospects of internationalization of higher education in China during 40 years of reform and opening-up]. China Higher Education Research, 12, 53–58.

- Wu, H. (2019). Three dimensions of China’s ‘outward-oriented’ higher education internationalization. Higher Education, 77(1), 81–96. doi:10.1007/s10734-018-0262-1

- Wu, H., & Mao, Y. (2012). 全球化进程中我国高等教育发展的自主性 [The autonomy of higher education development in globalization process]. China Higher Education Research, 9, 17–21.

- Wu, H., & Zheng, J. (2022). Examining China’s academic narratives surrounding higher education internationalization in foreign countries: A multi-theoretical lens. Journal of Studies in International Education, 1–20. doi:10.1177/10283153221082719

- Xia, R., & Zhang, M. (2004). 高等教育国际化:从政治影响到服务贸易 [Internationalisation of higher education: From political influences to trade in services]. 教育发展研究, 2, 23–27.

- Xu, H. (2006). 高等教育国际化的多视角分析 [A multiple-lens analysis on higher education internationalisation]. Jiangsu Higher Education, 2, 51–53.

- Xu, J. (2006). 国内高等教育国际化研究新进展 [New development of research on Chinese higher education internationalisation]. Heilongjiang Researches on Higher Education, 152(12), 4–9.

- Xu, X. (2021). A policy trajectory analysis of the internationalisation of Chinese humanities and social sciences research (1978–2020). International Journal of Educational Development, 84. doi:10.1016/j.ijedudev.2021.102425

- Xu, X. (2022). Epistemic diversity and cross-cultural comparative research: Ontology, challenges, and outcomes. Globalisation, Societies and Education, 20(1), 36–48. doi:10.1080/14767724.2021.1932438

- Yang, R. (2000). Tensions between the global and the local: A comparative illustration of the reorganisation of China’s higher education in the 1950s and 1990s. Higher Education, 39(3), 319–337. doi:10.1023/A:1003905902434

- Yang, R. (2014). China’s strategy for the internationalization of higher education: An overview. Frontiers of Education in China, 9(2), 151–162. doi:10.3868/s110-003-014-0014-x

- Yang, R. (2021). 中国高等教育国际化:走出常识的陷阱 [The internationalisation of Chinese higher education: Moving out of the traps of common sense]. 北京大学教育评论, 19(1), 165–172.

- Yeh, C. (2017). 高等教育“国际化/在地化”的吊诡与超越的彼岸 [The paradox of internationalization/indigenization and its beyond in higher education]. Peking University Education Review, 15(3), 73–190.