ABSTRACT

In this scholarship, I present insights from a sensory ethnographic study on novice educators’ embodied experiences of learning to teach sex education. I query how educators sense-make their role as knowledgeable sex educators in relation to the official and erotic discourses of sex education, and examine the experiential divisions between these discourses. Employing an arts-based approach to data generation and interpretation, my central argument proposes that increasing the permeability of the boundaries between official and erotic discourses in sex education can expand the ways learners’ bodies are understood in erotic, relational, and intimate contexts within pedagogy. By presenting these arguments, I aim to contribute to addressing the enduring challenges of the discourse of erotics ‘being’ in K-12 sex education and suggests ways to support educators in delivering effective pedagogical practices.

Introduction

Knowing what to teach in sex education is a demanding prospect. Perhaps more overtly than in many disciplinary areas, sex education acts as a cultural sponge, absorbing ideas, narratives and debates about the nature of sexuality, how might ‘healthy’ sexuality be ‘developed’, and notions of sexuality-based appropriateness (Trimble, Citation2012). Sex educators are tasked with wringing out this sponge – deeming what constitutes sexuality knowledge and what does not, and how this knowledge can be best addressed pedagogically.

In this work, I take up a long-standing academic discussion about the limits of sexuality knowledge conveyed by sex educators, via Western K-12 school-based settings, including considerations for expanding that knowledge (Fine, Citation1988; see also Allen, Citation2001; Citation2004; Allen & Carmody, Citation2012; Fine & McClelland, Citation2006; Koepsel, Citation2016). Although scholarship has documented that youth want ‘erotics’ included in sex education classrooms – defined here as discussion of sexual and/or feelings of sexual sensations – evidence suggests that such knowledge is not consistently brought into classrooms across cultures and contexts, especially for women and gender/sexuality minoritized people (Astle et al., Citation2021; Francis & DePalma, Citation2015; Waling et al., Citation2021; Walters & Laverty, Citation2022). I agree with Sciberras and Tanner (Citation2024), who argue that the traction of the fourth-wave feminist movement in valuing feminine experiences of sexuality; the visual affordances of digital technologies; as well as the current emphasis on creative, collaborative research methods have re-invigorated the erotic possibilities for sex education. I likewise heed Jolly’s (Citation2010) reminder that the who, what and how of ‘acceptable’ sexuality and sexual knowledge is an ever-topical question, and is one that orients my inquiry on the pedagogy, politics, and priorities of sex educators about erotics.

I contribute to this discussion an analysis of focal insights generated through a sensory ethnographic study (Pink, Citation2015) on novice educators’ embodied experiences of learning to teach sex education. I explore educators’ sense-making of being ‘knowledgeable’ sex educators in relation to Allen’s (Citation2004) erotic and official discourses of sex education, including querying key experiential divisions between these discourses. My central argument is that increasing the permeability of sex education’s official/erotic discursive bounds can expand how learners’ bodies are viewed in corporeal, relational, and intimate ways in pedagogy. In putting forward this argument, I strive to express how educators’ embodied sense-making may be meaningful for addressing enduring challenges of K-12 sex education and suggest possibilities for shifting pedagogical practices.

Erotic/official discourses in sex education

In 1988, Michelle Fine articulated the ‘missing discourse of desire’ to capture how anti-sex rhetoric in sex education in the United States denies youth, especially low-income women, sexual subjectivity and sexual responsibility. Continuing in this vein, Allen (Citation2004) delineated the distinction of the ‘official discourse’ and the ‘discourse of erotics’ in Western educative contexts. Allen (Citation2004) highlighted how the official discourse, which is composed of clinical, scientific and sanctioned information about sexuality (often institutionally framed as sexual health), differs from knowledge concerning/arousing sexual desire or giving sexual pleasure (defined as the discourse of erotics). Delineating the limitations of the official discourse, Allen and Carmody (Citation2012) have further called for educators to include the discourse of erotics within sexuality education to provide information and skills that young people need to negotiate pleasurable and ethical sexual intimacy. Indeed, the erotic discourse is based on the embodied acknowledgement that young people are sexual beings with the right to experience pleasure and desire. I further view that including erotics in sex education can help counter noted challenges of heteronormativity, stigma, and shame by enhancing youth’s ability to articulate their desires, know their sexual selves, and increase their likelihood of having satisfying sexual experiences (Edwards, Citation2016; Fine & McClelland, Citation2013). Said by Hunt (Citation2023), when educators provide knowledge helpful for decision-making about if and what kinds of sexual activities individuals want to engage in, educators can explicitly recognize and honor the lived experiences of people with diverse gender, sex, and sexualities in pedagogical practices.

I also see the discourse of erotics as further opening a generative space for inquiry. To build upon scholarship about the absence of pleasure, McGeeney and Kehily (Citation2016) highlight the importance of considering what can and does the erotic ‘do’ in sex education research and practice. I further extend this by asking how can the erotic ‘be’ – specifically, how do educators experience the erotic as ‘being’ alive or having existence in sex education? In doing so, I strive to –

… hold possibilities for cultivating pedagogical dispositions which can enable both teachers and researchers to move away from linear and hierarchical approaches to sexuality education in schools and cultivate possibilities for making it more relevant and meaningful for young people. (Quinlivan, Citation2018, p. 146)

Erotic/official discourses and educators

I view sex education pedagogy as inseparable from sex educators; as Koepsel (Citation2016) and others have demonstrated, sex educators are integral to successfully supporting learners in experiencing sexuality in positive ways. Building from Trimble (Citation2012), I define sex educators as those with specific training about sexuality-related knowledge and pedagogies, who participate in learning and teaching activities dedicated to sex education in various settings (e.g. school classroom or Instagram). Conceptualizing sex educators in connective ways allows us to consider how they embody varied and ideologically driven information, knowledge, and experiences, including assessments, standardizations, performance, purpose, and excitement.

I explore sex educators’ negotiations of the challenges of sex education pedagogy in K-12 schools in ways that I hope are ethical, generative and constructive. Like Koepsel (Citation2016), I am wary of how the literature on sex education can, at times, overemphasize teachers’ individualized failings in delivering sex education or suggest that educators develop different personal and disciplinary pedagogies without consulting those educators. Likewise, I strive to counter a tendency I have noted in literature of unevenly excluding educators’ experiences from discussions on pedagogical challenges, but including educators as agents of proposed advancements. I argue there is great value in not only including, but centering, educators in discussions of promoting embodied, eroticized approaches to sex education, as they can help scholars more fully understand the challenges that exist around shifting what Sciberras and Tanner (Citation2024) have termed ‘biologically essentialist approaches’ (p. 3).

Methodology

My methodology is oriented by a theoretical focus on embodiment, which I take up as the intersubjective, lived experiences of feeling, sensing bodies (Hare, Citation2021; Citation2024). The arts-based data analyzed here have been generated through a sensory ethnographic study (Pink, Citation2015) that I carried out to document my own and five focal participants’ embodied experiences of a community-based, sexual health educator training program [SHEC] in Vancouver, Canada.

Program overview

SHEC is a long-standing, professionalization program for individuals interested in learning to teach comprehensive sexual health education in schools and community settings in Canada. The comprehensive sexual health education pedagogical approach of SHEC is appropriate for this inquiry as the official discourse of sex education is typically framed as health (for discussion of challenges of the pedagogical approach see Gilbert, Citation2014; Gilbert, Fields, Mamo, & Lesko, Citation2018); and SHEC is recognized as an optimal standard of practice within Canada (Sieccan, Citation2019). This study was carried out in partnership with Options for Sexual Health, which is the organization that provides SHEC. In the program, novice sex educators are taught information on topics such as human rights, gender and sexual identities, anatomy, reproduction and contraception, as well as how to enact ‘value-neutral, evidence-based’ pedagogy. SHEC is highly interactive, with educators completing a prerequisite workshop before attending five 3-day-long modules over five months containing both theoretical and applied lessons. Homework, group work and quizzes are conducted between modules. Educators may complete a formal community practicum for program certification.

Methods

Ethical approval for the study was obtained from the University of British Columbia institutional ethics board and proceeded with free and informed consent. For the sensory ethnographic study, I completed two research stages: data generation and data interpretation. Data generation comprised two primary research components: (1) sensory ethnographic fieldwork and (2) solicited multisensory accounts, which had entailed qualitative and arts-based methods for data generation. The multisensory accounts were generated with the five focal participants and myself as a sixth participant, as I was also enrolled in the training program as a novice sex educator/ethnographer. Six participants allowed for in-depth, fine-grained, arts-based inquiry that attended to matters of embodiment. A summary of the participant characteristics is described in .

Table 1. Participant characteristics.

The methods for the solicited multisensory accounts included: (1) body maps (Sweet & Ortiz Escalante, Citation2015); (2) a book of expressive undertakings (James, Dobson, & Leggo, Citation2013); (3) body enactions (Winters, Citation2008); (4) sensorial interviews (Pink, Citation2015); and (5) erasure poetry (James, Citation2009). Utilizing multiple forms of expressive methods aligns with sex education research that hold the political objective of unsettling singular discourses about sexuality.

I interpret the expressive methods not only individually, but collectively and holistically, using arts-informed education scholarship to create composition pieces (Blaikie, Citation2009; White & Lemieux, Citation2015). Using different fonts and integrated images, I integrate with scholarly literature carefully chosen, relevant data from the different methods (e.g. components of body maps, erasure poems and poetic units, expressions, thin descriptions, and quotes); my reflective narratives/insights; and relevant connections to programmatic content. I also use juxtaposition to try to stimulate the reader’s own forms of sense-making to surface differences of genders, sexualities, languages, and other parts of knowing. To this end, although I offer a pointed, particular analysis, I agree with Waskul (Citation2009) that an intention behind embodied work in sexuality studies is to present findings in a way that renders them open to other interpretations.

Composition pieces: educators’ embodied insights

The interpretation of these findings focuses on the educators’ sense-making in relation to the official and erotic discourses of sex education to gain insights into the potential ‘beings’ of erotics. I present findings thematically based on two embodied senses: Outside In and Inside Out. In each theme, I highlight key experiential divisions between the official/erotic discourses, including moments where educators troubled their discursive bounds.

Official/erotic discourse: outside in

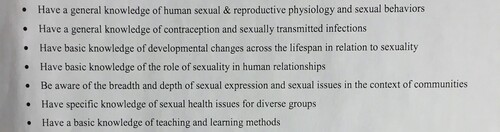

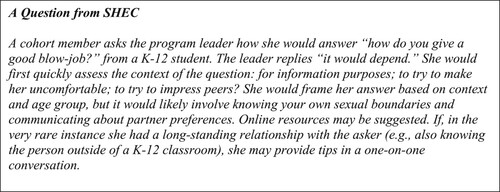

Becoming knowledgeable about sexual health was a crucial part of SHEC. Of the 19 program learning objectives, nine involved acquiring forms of knowledge for the instrumental purposes of teaching comprehensive sexual health. By the end of the program, the educators were expected to be accountable for basic, general or specialized knowledge of a range of topics, including contraceptives, sexual behaviors, and reproductive physiology. is a section of the program’s learning objectives from the course syllabus, with the bulleted list emphasizing a programmatic focus on skill acquisition and development.

The programmatic concentration paralleled one of the novice educators’ primary motivations for enrolling in SHEC – gaining a specific kind of knowledge about sexuality. The educators began SHEC with the perception that they wanted to acquire a concrete, definable, and bounded way of communicating about sexuality, which reflects the official discourse of sex education. The educators prioritized acquiring sexuality-related scientific information – also expressed as evidence and facts – and developing the ability to communicate this information easily to others. The discourse of erotics was not included in this knowledge. For instance, Llyr remarked:

I can be like, ‘hey these are the options’ … This is the sort of thing that you can do, or ‘this is better information’, or ‘this information is incorrect. Let’s look at it scientifically’ … I can talk about it scientifically, clinically, and directly.

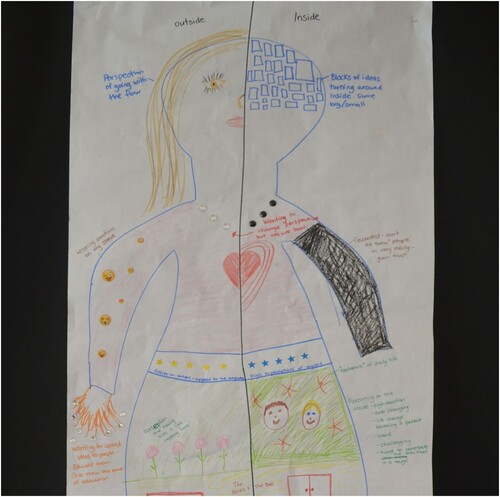

Reflecting a division between sexual health and sexuality, as well as the binaries (e.g. personal/professional, factual/emotional, failure/success, religious/secular) that often typify notions of best practices (see Francis & DePalma, Citation2015; Rasmussen, Citation2015), the official discourse was considered external to or outside of the educators’ bodies. Likewise, the official discourse was viewed by the educators as something that must be acquired by one’s mind and not generated through personal or bodily experiences. Visualized in Llyr’s body map (), wherein the colors blue and pink are knowledge, the educators conceived of this form of sexuality knowledge as being procured and then internalized through the SHEC training. Vanessa’s body map in shows the same pattern with acquired, external knowledge being around her neck (prism necklace) and then once embodied, coming out of her left hand.

Official/erotic discourse: inside out

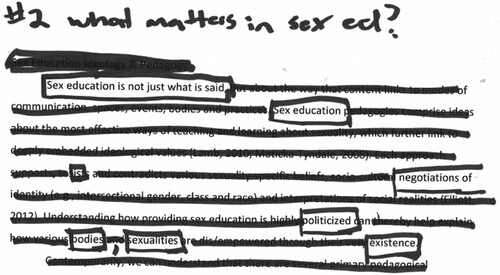

The focus on sexual health/official discourse is not to suggest that the educators weren’t aware of other forms of sexuality knowledge/discourses, including the discourse of erotics. See for example, the Kaye’s blackout poem about what matters in sexual education.

As reflected in the poem’s blacking out visual qualities and content emphasizing that discursive forms of sex education may benefit by including politicized bodies, the educators had multiple, varied experiences with the discourse of erotics. Mirroring literature documenting that the discourse of erotics exists outside the typical bounds of sex education pedagogy in Canadian classrooms (Action Canada, Citation2020; Byers, Sears, & Foster, Citation2013; Hare, Gahagan, Jackson, & Steenbeek, Citation2014), although the discourse of erotics existed alongside the official discourse in SHEC, much like the poem, erotics was heavily abstracted in emerging practices. While the novice sex educators adopted a sex-positive perspective to highlight concepts like erotics, pleasure, and sexual joy/fun, the specific information provided was figurative, vague, and lacked experiential connections (e.g. using the word ‘pleasure’ or ‘enjoyment’ in verbal descriptions); pleasure existed as a secondary topic.

Further increasing this abstraction, it became apparent that ‘scientific evidence’ was invoked differently by resources (e.g. online lesson plans, textbook information from SHEC) centered on conveying the official discourse versus the discourse of erotics, including topics that support erotics such as sexual identity and values. Vanessa discussed the relationship between ‘fact’ and sexual diversity as one of her most meaningful embodied insights of SHEC:

The next question is: what content did you find the most meaningful in the course of everything that we learned?

I guess there’s two things. Number one like the, basically like the scientific information. I always find that interesting. But also the diversity within the information … You know, I mean there’s definitely a right or a wrong with science. But just the diversity within people right … and how diverse that can be.

For people or are you also meaning how you talk about [diversity]?

Both, yeah. But then like say HIV – ‘these are the facts’, you know. So, they kind of, those two things kind of contradict each other …

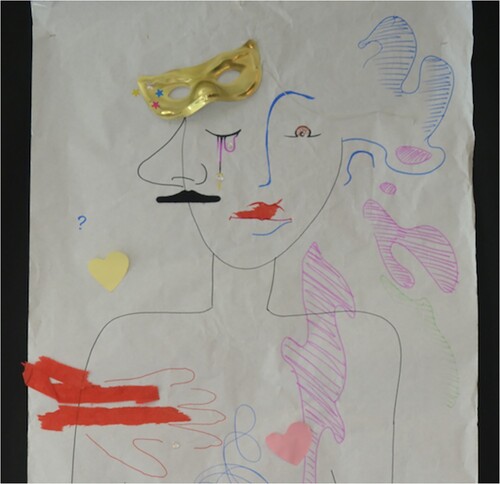

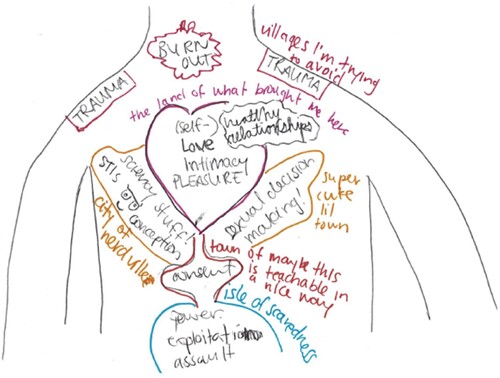

In probing these differences with the focal educators, it became apparent that although they didn’t feel the erotic and official discourses were mutually exclusive and corporeal elements were recognized as a valid part of sex education in general, the discourse of erotics considered less feasible within the parameters of K-12 sexual health education. One of Jasper’s drawings in her expressive undertaking booklet () helps capture this sense-making.

Jasper’s drawing shows the strains of educators recognizing youth as sexual beings (e.g. the centering of love, intimacy, and pleasure), while simultaneously feeling as though meeting youth’s erotic needs may not be possible (e.g., ‘town of maybe this teachable in a nice way’ written in red beside consent and the avoidance of ‘villages of trauma’).

The educators’ discussions of why erotics may be out of their capacity mirrored explanations from literature: the lack of cultural acceptability about discussing erotic activities (Fine & McClelland, Citation2013; Lamb, Lustig, & Graling, Citation2013); different intersectional experiences of sexuality and erotics (Koepsel, Citation2016); and logistical reasons (Oliver, van der Meulen, Larkin, & Flicker, Citation2013). Interestingly, however, the educators’ ways of making sense of their own bodies came up as an additional tension. Two educators discussed viewing the employment of official discourses of knowledge as the key, defining feature of being a sexual health educator. Sexual health educators were felt to be individuals whose pedagogy focused on evidence-based, scientific knowledge, as differentiated from broad-based sex educators who might provide information on a variety of topics. As articulated by Jasper:

How do you do that kind of work and ask people to be vulnerable and like talk about really intimate things, or like really kind of body sort of sexual things … that is not really a possibility in a lot of careers unless you want to be like a weird sex coach.

Either you’re like, yeah, she has a degree in the education and like all the good stuff so like she’s a scientific one versus she’s the sex educator that will pose in her like lingerie and in front of a red background and will do like – like how to give a blow job workshop.

Not all the educators felt like Jasper and Malka. Social worker Aurora, who worked closely with young men who are parents and had the status of being a mature woman, felt friction on the topic. For her, it was a source of frustration that the discourse of erotics was not a primary part of SHEC. Aurora undertook erotic knowledge acquisition through her own initiatives detailed in her description and body enaction:

What else should I be supplementing … Talking to other sexual health educators. What do they do, how do they do it, what are they bringing in? Where are they getting their information from? What’s out there? How conservative is your community? How conservative is not your community.

Aurora - Body enaction #1 Watching Reputable Porn

Aurora's wide eyes are focused on a point in front of her and her mouth is open. She squints her eyes and furrows her brow. She moves her head back briefly, unfurrowing her brow and closing her mouth slightly…She then clasps her hand up to her mouth, with her eyes going wide.

Drawing on her own embodied and internal forms of knowledge, Aurora explicitly linked the discourse of erotics to the official discourse, saying ‘we can talk about sex too. That’s the other thing. It’s okay … ’. She suggested that there was a need to explore embodied sensations of sexuality for what Jafari Allen (Citation2012) has phrased the ‘deepening and enlivening’ of learners’ experiences, and move past confusion like that expressed via her body enaction. Aurora felt that to more directly link pedagogy to lived experiences of sexuality, sexual activities should be discussed:

The health piece ties into the sexuality piece but if you have never done sexuality work and you are very … in my case very naïve, very vanilla, if you will … it is all very new to me … I guess in a sense of exploring my own sexuality. It is not even about my values and beliefs. It is ‘oh that doesn’t make me feel good’ or ‘oh I really like how that felt’.

Implications for the erotic/official discourse

The educators’ embodied insights into the official discourse and discourse of erotics (Allen, Citation2004), highlighted key experiential differences about (a) clinical, scientific and sanctioned information, and (b) relational, intimate and embodied information about sexuality/sexual health. Such findings contribute to existing literature that explores the feasibility of the discourse of erotics in sex education (Fine & McClelland, Citation2013; Koepsel, Citation2016; Lamb et al., Citation2013) – or how erotics can ‘be’ in sex education. Key sense-making included educators’ feelings that official discourse was external to bodies and conceptual, while the discourse of erotics was considered to be abstract and untethered within bodies. The educators expressed the sense that the official discourse is supported by facts, while the discourse of erotics is variable and can be enabled in individual learners via the official discourse. The findings further highlighted the meanings the educators placed on embodying the discourses, including the sense that teaching different discourses publicly marked their bodies as educative versus erotic (or in Jasper’s words ‘a weird sex coach’) and granted them legitimacy. Such framing was rife with tensions, as highlighted through Aurora’s sense that excluding the erotic discourse from sex education reduces the applicability and meanings that learners might make; the educators agreed that the inclusion of discourse of erotics into pedagogy would need to be contextually considered.

Considering the study’s implications in relation to the well-established benefits of the discourse of erotics ‘doing’ in sex education (McGeeney & Kehily, Citation2016; see also Hunt, Citation2023), I suggest that a path forward for erotics ‘being’ may be challenging the perceived mutual exclusiveness of the official and erotic discourses. In particular, I put forward two strategies for increasing the porousness of these discourses: incorporating erotic bodies into the official discourse and grounding the discourse of erotics within bodies by increasing its physical tangibility and concreteness.

Taking up the first, one strategy may be for sex educators to trouble practices wherein the official discourse is viewed as external and conceptual (reinforcing a Cartesian mind/body split). Evidenced by this study and others (see also Koepsel, Citation2016), this split can happen through pedagogical practices that falsely divide bodies into physical sensations/arousal versus emotional responses versus intellectual reason. I suggest, however, that the more educators conceive of bodies as an integrated whole, the more likely it is that pedagogical practices involving the official discourse can connect with different bodies that feel, sense, respond and make meaning in a multitude of ways. Inspired by Walters, Czechowski, Courtice, and Shaughnessy (Citation2021), an example of one such practice may be for educators to expand their discussion from the ‘fit’ of external condoms, gloves and dental dams to their ‘feel’ in ways that consider sensation and emotional closeness. For instance, when educators explain how to know if a barrier has the appropriate tightness or fit, length and positioning, they can likewise mention the importance of asking oneself: ‘Do I feel safer?’; ‘Do I feel protected?’; and ‘Does it feel better for my genitals/hand/tongue/sex toy to have a barrier?’ or ‘Do I feel the right amount of connectedness with my partner(s)?’ Simply integrating the differently-evocative term ‘feel’ with ‘fit’, can help to foster connections through the official discourse that may be severed through focusing on physical sensations. These body-based connections can also encourage educators to check the discursive messages around risk or sex-negativity they might be subtly conveying in language (e.g. assuming that people think barriers reduce how ‘good’ sex feels).

Taking up the second, a practice that may create more concrete evidence about the discourse of erotics is to use fulsome descriptors and adjectives when discussing the erotic aspects of sexuality. Recognizing that the discourse of erotics and pleasure may already be scarcely deployed in K-12 education settings (Allen, Citation2004; Allen & Carmody, Citation2012; Rasmussen, Citation2015), I think that there is value for sex educators to employ the same preciseness in discussing aspects of pleasure as used when discussing other topics, like arousal. Often the word ‘pleasure’ is used to simultaneously mean desire, sexual touching, erotic feelings, or any and all things that may feel good. But as explained by Darnell (Citation2019), the word pleasure can be confusing and is a special form of embodiment. Pleasure is a complex embodied state that is often defined as enjoyment and satisfaction – conditions that suggest end states rather than ongoing, evolving, and changing bodily responses. Adding to this, what people expect to be/not be pleasurable and how people express pleasure are all influenced (and often limited) by circulating social configurations of power, morality, sexual orientation and gender identity (Darnell, Citation2019; Hills, Pleva, Seib, & Cole, Citation2021)

Following the trend to use specific language in K-12 sex education (e.g. ‘body with a penis’ instead of ‘boy’), I think there is merit in using phrasing like ‘stimulation that feels good’ or ‘nervousness that can be exciting’ instead of using ‘pleasure’. When educators discuss stimulation, it becomes possible to talk about bodily sensations and perceptions including the senses, and then highlight how these (can) become more active, intense or heightened. Moreover, educators can talk about specific bodily responses in terms of physiological and emotional states, including how these can mirror other states of arousal like fear, aggression, or nervousness. Rather than stating there is ‘enjoyment’ in sexuality, educators can talk about specific qualities, such as a feeling of enthusiastic consent, an absence of preoccupation with body/genital image, a sense of building intimacy, or a feeling of disinhibition. These are all concrete qualities that can provide learners with opportunities for more expansive meanings and can also be applied in multiple sexual contexts (e.g. assessing for self-willingness to engage in an activity) and used for important determinations like consent.

The point of discussing pleasure precisely, is not to turn it into a de-eroticized science lesson, but to recognize and correct (at least) the uneven treatment of pleasure in scientifically or health-framed official discourses of sex education, which further obfuscate the already limited presence of the erotic discourse. Focusing on components of pleasure can also identify differences in how people engage and define sexual activity and encourage educators to move away from prescriptive sex education that prioritizes some sexual acts over others. Indeed, opening pleasure up will likely be particularly beneficial for those learners who have not been previously recognized within sex education. In applying specific content to their own bodies, learners are invited to reflect upon their own preferences, including what forms of sexual enjoyment may or may not be wanted – the more expansive but meaningful education posited by Quinlivan (Citation2018).

Finally, using such strategies can help educators provide more contextual, tailored information that does not contribute to false divides that also cast educators’ bodies as either informative or erotic – with authority only being granted to the former. Increasing the permeability of discourses can allow educators to participate in re-imagining sex education’s purpose more fully, including their role of educators who provoke life-enhancing ways of thinking about and expressing sexuality that can expand prevailing instrumental approaches. Sex education wherein educators teach with imagination, spontaneity, and ambiguity, may help unlock creative pedagogical potentials that are relational, emergent, and non-linear.

Ethics Agreement

University of British Columbia H18-02776.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Action Canada. (2020). State of sex-ed report. Action Canada for Sexual Health & Rights. https://www.actioncanadashr.org/resources/reports-analysis/2020-04-03-state-sex-ed-report.

- Allen, J. (2012). One way or another: Erotic subjectivity in Cuba. American Ethnologist, 39(2), 325–338.

- Allen, L. (2001). Closing sex education’s knowledge/practice gap: The reconceptualisation of young people’s sexual knowledge. Sex Education, 1(2), 109–122. doi:10.1080/14681810120052542

- Allen, L. (2004). Beyond the birds and the bees: Constituting a discourse of erotics in sexuality education. Gender and Education, 16(2), 151–167. doi:10.1080/09540250310001690555

- Allen, L., & Carmody, M. (2012). ‘Pleasure has no passport’: Re-visiting the potential of pleasure in sexuality education. Sex Education, 12(4), 455–468. doi:10.1080/14681811.2012.677208

- Astle, S., McAllister, P., Emanuels, S., Rogers, J., Toews, M., & Yazedjian, A. (2021). College students’ suggestions for improving sex education in schools beyond ‘blah blah blah condoms and STDs’. Sex Education, 21(1), 91–105.

- Blaikie, F. (2009). Knowing bodies: A visual and poetic inquiry into the professoriate. International Journal of Education & the Arts, 10(8), 1–32.

- Brömdal, A., Rasmussen, M. L., Sanjakdar, F., Allen, L., & Quinlivan, K. (2017). Intersex bodies in sexuality education: On the edge of cultural difference. In L. Allen & M. L. Rasmussen (Eds.), The Palgrave handbook of sexuality education (pp. 369–390). London: Palgrave MacMillan. doi:10.1057/978-1-137-40033-8_18

- Byers, E. S., Sears, H. A., & Foster, L. R. (2013). Factors associated with middle school students’ perceptions of the quality of school-based sexual health education. Sex Education, 13(2), 214–227. doi:10.1080/14681811.2012.727083

- Darnell, C. (2019). Consent lies destroy lives: Pleasure as the sweetest taboo. In B. Fileborn & R. Loney-Howes (Eds.), # MeToo and the politics of social change (pp. 253–266). Cham: Palgrave Macmillan. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-15213-0_16

- Edwards, N. (2016). Women’s reflections on formal sex education and the advantage of gaining informal sexual knowledge through a feminist lens. Sex Education, 16(3), 266–278.

- Fine, M. (1988). Sexuality, schooling, and adolescent females: The missing discourse of desire. Harvard Educational Review, 58(1), 29–54. doi:10.17763/haer.58.1.u0468k1v2n2n8242

- Fine, M., & McClelland, S. (2006). Sexuality education and desire: Still missing after all these years. Harvard Educational Review, 76(3), 297–338. doi:10.17763/haer.76.3.w5042g23122n6703

- Fine, M., & McClelland, S. (2013). Over-sexed and under surveillance: Adolescent sexualities, cultural anxieties, and thick desire. In L. Allen, M. L. Rasmussen, & K. Quinlivan (Eds.), The politics of pleasure in sexuality education (pp. 12–34). New York: Routledge. doi:10.4324/9780203069141.

- Francis, D. A., & DePalma, R. (2015). ‘You need to have some guts to teach’: Teacher preparation and characteristics for the teaching of sexuality and HIV/AIDS education in South African schools. SAHARA-J: Journal of Social Aspects of HIV/AIDS, 12(1), 30–38. doi:10.1080/17290376.2015.1085892

- Gilbert, J. (2014). Sexuality in school: The limits of education. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. doi:10.5749/j.ctt7zw6j4

- Gilbert, J., Fields, J., Mamo, L., & Lesko, N. (2018). Intimate possibilities: The beyond bullying project and stories of LGBTQ sexuality and gender in US schools. Harvard Educational Review, 88(2), 163–183. doi:10.17763/1943-5045-88.2.163

- Hare, K. (2021). ‘All the feels’– Exploring educators’ embodied experiences of sex education (Doctoral dissertation, University of British Columbia). Retrieved from https://open.library.ubc.ca/collections/ubctheses/24/items/1.0404514.

- Hare, K., Gahagan, J., Jackson, L., & Steenbeek, A. (2014). Perspectives on “Pornography”: Exploring sexually explicit internet movies’ influences on Canadian young adults’ holistic sexual health. The Canadian Journal of Human Sexuality, 23(3), 148–158. doi:10.3138/cjhs.2732

- Hare, K. A. (2024). “Sandpaper. Yeah.”: Educators’ embodied insights into comprehensive sexual health education pedagogy. Canadian Journal of Education, 47(1), 27–58. doi:10.53967/cje-rce.6133

- Hills, P. J., Pleva, M., Seib, E., & Cole, T. (2021). Understanding how university students use perceptions of consent, wantedness, and pleasure in labeling rape. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 50, 247–262.

- Hunt, C. (2023). ‘They were trying to scare us’: College students’ retrospective accounts of school-based sex education. Sex Education, 23(4), 464–477.

- James, K. (2009). Cut-up consciousness and talking trash. In M. Prendergast, C. Leggo, & P. Sameshima (Eds.), Poetic inquiry: Vibrant voices in the social sciences (pp. 59–74). Rotterdam: Sense Publishers.

- James, K., Dobson, T., & Leggo, C. (2013). English in middle and secondary classrooms: Creative and critical advice from Canada’s teacher educators. Toronto: Pearson Canada.

- Jolly, S. (2010). Why the development industry should get over its obsession with bad sex and start to think about pleasure. In A. Lind (Ed.), Development, sexual rights and global governance (pp. 23–38). New York: Routledge/Ripe.

- Koepsel, E. R. (2016). The power in pleasure: Practical implementation of pleasure in sex education classrooms. American Journal of Sexuality Education, 11(3), 205–265. doi:10.1080/15546128.2016.1209451

- Lamb, S., Lustig, K., & Graling, K. (2013). The use and misuse of pleasure in sex education curricula. Sex Education, 13(3), 305–318. doi:10.1080/14681811.2012.738604

- McGeeney, E., & Kehily, M. J. (2016). Young people and sexual pleasure – where are we now? Sex Education, 16(3), 235–239.

- Oliver, V., van der Meulen, E., Larkin, J., & Flicker, S. (2013). If you teach them, they will come: Providers’ reactions to incorporating pleasure into youth sexual education. Canadian Journal of Public Health; Ottawa, 104(2), e142–e147.

- Pink, S. (2015). Doing sensory ethnography (2nd ed.). Los Angeles: SAGE.

- Quinlivan, K. (2018). Exploring contemporary issues in sexuality education with young people: Theories in practice. London: Palgrave MacMillan.

- Rasmussen, M. L. (2015). Pleasure/desire, secularism, and sexuality education. In Progressive sexuality education (pp. 87–103). New York: Routledge. doi:10.1080/14681811.2012.677204

- Sciberras, R., & Tanner, C. (2024). ‘Sex is so much more than penis in vagina’: Sex education, pleasure and ethical erotics on Instagram. Sex Education, 24(3), 344–357.

- Sieccan. (2019). Canadian guidelines for sexual health education. Toronto: Public Health Agency of Canada. http://sieccan.org/sexual-health-education/

- Slovin, L. (2016). Learning that ‘gay is okay’: Educators and boys re/constituting heteronormativity through sexual health. Sex Education, 16(5), 520–533. doi:10.1080/14681811.2015.1124257

- Sweet, E. L., & Ortiz Escalante, S. (2015). Bringing bodies into planning: Visceral methods, fear and gender violence. Urban Studies, 52(10), 1826–1845. doi:10.1177/0042098014541157

- Trimble, L. M. (2012). Teaching and learning sexual health at the end of modernity: Exploring postmodern pedagogical tensions and possibilities with students, teachers and community-based sexualities educators [Unpublished Ph.D., McGill University (Canada)]. https://search.proquest.com/docview/1243510862/abstract/79CD5D89E8194286PQ/1.

- Waling, A., Fisher, C., Ezer, P., Kerr, L., Bellamy, R., & Lucke, J. (2021). ‘Please teach students that sex is a healthy part of growing up’: Australian students’ desires for relationships and sexuality education. Sexuality Research and Social Policy, 18, 1113–1128.

- Walters, L., Czechowski, K., Courtice, E. L., & Shaughnessy, K. (2021). An EFA of a revised condom fit and feel scale (CoFFee-R): Adding intimacy and pleasure. The Canadian Journal of Human Sexuality, 30(2), 252–264.

- Walters, L., & Laverty, E. (2022). Sexual health education and different learning experiences reported by youth across Canada. Canadian Journal of Human Sexuality, 31(1), 18–31. doi:10.3138/cjhs.2021-0060

- Waskul, D. D. (2009). ‘My boyfriend loves it when I come home from this class’: Pedagogy, titillation, and new media technologies. Sexualities, 12(5), 654–661. doi:10.1177/1363460709340374

- White, B. E., & Lemieux, A. (2015). Reflecting selves: Pre-service teacher identity development explored through material culture. LEARNing Landscapes, 9(1), 267–283. doi:10.36510/learnland.v9i1.757

- Winters, A. F. (2008). Emotion, embodiment, and mirror neurons in dance/movement therapy: A connection across disciplines. American Journal of Dance Therapy, 30(2), 84–105. doi:10.1007/s10465-008-9054-y