ABSTRACT

Organizations are increasingly replacing performance ratings with continuous feedback systems. The current study assesses how people react to continuous performance feedback in terms of its content and sources concerning their performance, motivation to improve, and task engagement. A task-based experiment was conducted with 36 participants who received continuous feedback. The participants were divided into two groups, receiving either quantitative or qualitative feedback content. Feedback was delivered through computer-mediated, person-mediated, or no source. The results highlight that person-mediated feedback, regardless of content, positively influenced performance, motivation, and task engagement. On the other hand, quantitative feedback only showed a positive association with performance. These findings suggest that qualitative feedback is more effective, enhancing motivation and engagement. Managers should prioritize person-mediated feedback to optimize performance, as it yields superior outcomes compared to computer-mediated feedback. However, further research is required to comprehensively understand the effectiveness of continuous performance feedback and its specific characteristics.

Performance feedback is one of the most studied practices in the performance management literature, and organizational behavior management (OBM) has significantly contributed to this topic, as performance feedback is among its most researched interventions (Alvero et al., Citation2001; Balcazar et al., Citation1985; Sleiman et al., Citation2020; Tagliabue et al., Citation2020). Performance management can be defined as the process of identifying, measuring, and developing the performance of employees and aligning their efforts toward organizational goals and priorities (Aguinis, Citation2009). The theoretical and methodological approaches offered by OBM are particularly relevant to the performance management domain as it enables the study of performance feedback from a systems approach (Wilder et al., Citation2009; Wine & Pritchard, Citation2018). More specifically, OBM facilitates the study of performance feedback by examining how such interventions can be implemented in a way that changes employee behavior meaningfully and translates into increased employee performance (Daniels & Bailey, Citation2014; Wilder et al., Citation2009).

Despite the widespread use of performance feedback in organizations, recent evidence shows that employees are mostly dissatisfied with the feedback that they receive and that it is not always effective for improving future performance (Adler et al., Citation2016; Kluger & DeNisi, Citation1996). This is not surprising considering that we still observe mixed findings about the efficacy of performance feedback. While some studies have reported a positive association between performance feedback and employee performance (Alvero et al., Citation2001; Balcazar et al., Citation1985; Sleiman et al., Citation2020), others report no significant influence, or even negative impacts, on performance, especially when performance feedback is perceived as critical and/or excessively controlling of employees’ behaviors (Kluger & DeNisi, Citation1996). To circumvent these performance issues, and also engage and motivate employees to improve, more and more organizations are now promoting continuous performance feedback (Cappelli & Tavis, Citation2016; Deloitte, Citation2017a); a performance management practice that involves providing employees with performance-related information on a regular basis throughout the year (Traynor et al., Citation2021). In practice, this often takes the form of manager-employee check-in sessions, or informal performance discussions, on a weekly or monthly basis (Traynor et al., Citation2021).

We still know little about continuous performance feedback as a performance management practice (Budworth & Chummar, Citation2022; Doucet et al., Citation2019; Pulakos et al., Citation2019). Notably, there is a lack of empirical evidence that such a practice can deliver on organizations’ desires to enhance employees’ performance and motivation (Cappelli & Tavis, Citation2016; Deloitte, Citation2017a, Citation2017b). Furthermore, there is variability in terms of how the practice is implemented in organizations. For example, continuous performance feedback can be delivered with different types of feedback content (i.e., quantitative vs qualitative) and feedback sources (e.g., computer vs. person) (Kluger & Adler, Citation1993; Tekian et al., Citation2017). The purpose of the current study is to address these gaps in the literature by conducting an experiment that examines the impacts of continuous performance feedback, its contents, and sources, on employee performance, motivation to improve, and task engagement.

While the end goal of providing employees with performance feedback is performance per se, it is paramount that the performance feedback also motivates employees to improve in the future or engage more fully in their work (Fairclough et al., Citation2013; Fedor et al., Citation1989; Shkoler et al., Citation2021). When employees want to improve their performance, they can direct their work more purposefully (Pinder, Citation2008). In this sense, employees are inclined to take action to achieve their performance-related objectives and abstain from counter-productive work behaviors (Pinder, Citation2008; Shkoler et al., Citation2021). Task engagement is also an important variable to examine in the context of receiving continuous performance feedback because it gives us insights as to whether individuals invest themselves in the tasks that they must do after receiving feedback (Fairclough et al., Citation2013). Task engagement can be defined as the cognitive effort (or energy) that individuals direct toward a task to complete a goal (Fairclough et al., Citation2013). Furthermore, this construct has been extensively validated in the neuroscientific literature and has been mobilized in performance contexts (Charland et al., Citation2015; Pope et al., Citation1995).

In the context of performance management, feedback content refers to information that is provided to employees and which relates to their performance (Lampe et al., Citation2021; Lechermeier & Fassnacht, Citation2018). Such content can be quantitative in nature, like numerical representations of past performance which can reinforce desirable employee behaviors (Garber, Citation2004; Runnion et al., Citation1978). On the other hand, research on qualitative feedback explains that feedback can change employee behavior especially when it includes high-quality messages (i.e., messages that are specific and relevant to performance), as it can help employees interpret the appropriateness of their behaviors and take actions to improve their performance (Lampe et al., Citation2021; Whitaker & Levy, Citation2012). Nonetheless, what is unclear in the literature is how continuous performance feedback and its contents can impact employee performance and other important variables that are closely related to performance such as motivation to improve and task engagement. To respond to this gap in the literature we ask the following research question:

RQ1.

What are the effects of feedback content (i.e. quantitative vs qualitative) on performance, motivation to improve, and task engagement in the context of continuous performance feedback?

Furthermore, continuous performance feedback does not only vary in terms of its contents but also its sources (Johnson et al., Citation2022; Kluger & Adler, Citation1993; Warrilow et al., Citation2020). Most organizations have promoted the delivery of continuous feedback by encouraging managers to have one-on-one conversations with their employees about their performance (e.g., person-mediated feedback) (Alder & Ambrose, Citation2005b; Deloitte, Citation2017b; Kluger & Adler, Citation1993; Pulakos et al., Citation2019). However, a significant number of organizations have also promoted the use of technology (e.g., computers, mobile applications, etc.) to assist managers in delivering feedback to employees in a timely fashion (Brecher et al., Citation2016; Deloitte, Citation2017b; Zeng, Citation2016). Even though both feedback sources can be used to deliver feedback to employees, their impacts on performance, motivation, and task engagement are up to now inconsistent or non-existent.

On the one hand, Kluger and Adler (Citation1993) have reported that computer-mediated feedback is more effective than person-mediated feedback. This finding is sensible when we consider that managers often express difficulties in providing employees with feedback that can effectively change employees’ behaviors (Solomon, Citation2016), making computer-mediated feedback an interesting option to support performance (Alder & Ambrose, Citation2005a; Kluger & Adler, Citation1993). On the other hand, there is also evidence that person-mediated feedback can also foster performance (Johnson et al., Citation2022; Warrilow et al., Citation2020).

For instance, even though managers are not always well-trained to provide employees with feedback, the affective and social cues that are part of giving face-to-face feedback can positively impact employees’ behaviors (Warrilow et al., Citation2020). Yet, the relative effectiveness and the circumstances under which these feedback sources effectively support employees’ performance, desire to improve and engagement toward their work remains unclear. Research has yet to shed light on this subject in the context of continuous performance feedback (Alvero et al., Citation2001; Balcazar et al., Citation1985; Kluger & DeNisi, Citation1996; Sleiman et al., Citation2020). Hence, we ask the following research question:

RQ2.

What are the effects of feedback source (i.e., computer vs. person) on performance, motivation, and task engagement in the context of continuous performance feedback?

Method

Design

The present study used a mixed 2 × 3 factorial design containing between- and within-subjects factors. Participants were divided into two independent groups (based on the feedback content they were supposed to receive) that were labeled as: quantitative versus qualitative feedback. Participants in the quantitative feedback group received a numerical rating based on their performance (e.g., the correct percentage of responses) on each block of the experimental task. The qualitative feedback group did not receive any ratings during the task. Within each of these groups, all participants received after each block, qualitative feedback from different sources: a computer (i.e. pop-ups), a person (i.e. vocal messages), and no source.

Participants

An a priori power analysis was conducted using G*Power version 3.1 to determine the minimum sample size required to respond to our research questions (Faul et al., Citation2007). Results indicated the required minimum sample size to achieve 80% power for detecting a medium effect, at a significance criterion of α = .05, was n = 28 for a mixed factorial ANOVA. We recruited 38 participants and among these participants that were recruited for this study, two were eliminated from the final sample as they had incomplete/bad response patterns. To be more precise, the participants in question were not following task instructions and responding to stimuli haphazardly.

Our participants (n = 36) were between 18 and 41 years of age (M = 24.64, SD = 4.67, nmale = 16, nfemale = 20) and were mostly university students or recent graduates. Participants were solicited via the participant pool of our institution. Authorization to solicit participants was obtained from the research ethics board of our institution. Participants were compensated with a $50 Amazon gift card. The participants were healthy and screened to ensure that they had normal eye vision and no hearing difficulties. We excluded participants who declared that they had a psychiatric or neurological disorder as well as individuals who declared that they had a physical health problem. Each group contained 16 participants with a similar age range (MQuantitative = 25.00, SDQuantitative = 5.80, nfemale = 11, nmale = 7, MQualitative = 24.28, SDQualitative = 3.30, nfemale = 9, nmale = 9) and all participants were randomly assigned to the two different groups in the experiment. We excluded an additional four participants specifically for our EEG analyses due to low quality recordings (details are provided in the analyses section).

Task and stimuli

The experimental n-back task

An n-back task was used through E-Prime Software. The n-back task is a cognitive performance task that is commonly used in psychology and neuroscience to assess the working memory capacity of individuals (Gajewski et al., Citation2018; Scharinger et al., Citation2017). We chose this task because working memory is important for conducting tasks and activities in a variety of contexts that could be in and outside of the workplace and because it can be a good predictor of job performance (Alloway & Copello, Citation2013; Martin et al., Citation2020).

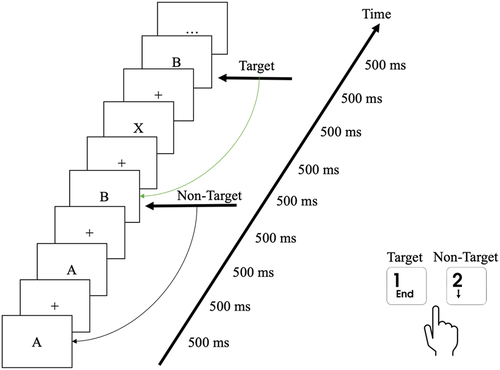

During the task, participants were presented with a series of letters, and they had to decide whether the present stimulus (i.e. letter) was congruent with the one they saw two trials ago (Gajewski et al., Citation2018). The stimulus was presented every 500 ms and an inter-onset interval of 500 ms was set. The stimuli were presented sequentially at the center of the computer screen. When the stimuli were congruent or incongruent, participants could press one of two keyboard buttons to confirm the presence or the absence of a match (Please see ).

Participants only saw their performance data when the block was complete, and the stimuli matched in approximately 25% of the trials. For each condition, there were 4 blocks and each block contained 25 trials. In addition to participants being randomly assigned to their groups, the order of presentation for the experimental blocks was counterbalanced for all participants.

Feedback content: quantitative feedback and qualitative feedback

In the experiment, participants in the quantitative feedback group received a numerical performance rating (i.e. the correct percentage of responses that is based on their accuracy after each block) on their screen which was followed by qualitative feedback after each block. For example, if a participant had 18 out of 25 correct responses, the correct percentage of responses (i.e., 72%) would appear on their screen. Participants in the qualitative feedback group continued the task without being presented with a rating. All participants were exposed to qualitative performance feedback from different sources continuously (i.e. after each block).

The qualitative feedback that was provided to participants was in the form of an instructional script. Scripts were developed based on the change-oriented feedback model of Carpentier and Mageau (Citation2013) to ensure the transmission of high-quality performance feedback to all participants regardless of the feedback source. Change-oriented feedback is a type of feedback that seeks to help underperforming individuals achieve optimal levels of performance and foster individual autonomy (Carpentier & Mageau, Citation2013). The feedback scripts in the computer-mediated condition would appear as a pop-up message on the computer screen that the participant could read, whereas the feedback scripts in the human-mediated condition would be read verbatim to the participant by the same experimenter for all participants (See Appendix). In the condition in which they received no qualitative feedback, participants carried on with the task.

Adaptive testing

The n-back task was adapted in this experiment to create a challenging task that would put participants in a situation in which they can improve their performance. We did this by adapting the participants’ response time so that they would receive on average an accuracy level of 80%. The goal here was to continuously put participants in a zone of potential improvement. Participants who scored below 65% were given more time to respond (i.e. 2000 ms to respond instead of 1500 ms), and participants who had very high performance (i.e. above 80%) were given less time to respond (i.e. 1000 ms to respond instead of 1500 ms). This approach would not only prevent low performers from giving up but also limit the possibility of higher performers diverting their attention away from the task.

Dependent variables

Performance

Behavioral measures were collected during the experiment through E-Prime software. Performance was extracted after each block that the participant had conducted in the experimental task and was calculated as a percentage of the number of correctly identified matches and mismatches by the participant. This dependent variable represents the accuracy with which the participants responded to the task.

Motivation to improve performance

The Motivation to Improve Performance Scale by Fedor et al. (Citation1989) was used to measure participants’ motivation after receiving feedback from different feedback sources. Motivation to improve performance can be defined as people’s desire to improve their performance after receiving feedback that relates to their past performance (Fedor et al., Citation1989). This scale is a 5-point Likert scale (1= “strongly agree” and 5 = “strongly disagree”). Thus, a lower score demonstrates higher levels of motivation to improve and vice versa. The scale has three items; here is a sample item, “The feedback encouraged me to improve my performance”.

Two versions of the scale were presented to the participants at the end of the study. First, the participants that only received qualitative feedback completed the original version of the scale. Second, the participants that received both quantitative and qualitative feedback completed the original and the adapted versions of the scale. The adapted version measured their motivation to improve their performance after receiving a performance rating. To adapt the scale of Fedor et al. (Citation1989) we replaced the word “feedback” in the items with the word “rating.”

Task engagement

In the current study, we measured participants’ levels of engagement by using the index developed by Pope and his colleagues (Pope et al., Citation1995). Task engagement can be defined as “a fundamental dimension of user psychology related to human performance” (Fairclough et al., Citation2013, p. 65) that reflects how invested an individual is during a task (Fairclough et al., Citation2013; Mikulka et al., Citation2002; Pope et al., Citation1995).

Our EEG measures were acquired by setting up an EEG montage (Brain Products, Germany). Engagement was calculated by extracting brain activity on four electrode sites, Cz, Pz, P3, and P4 (Bailey et al., Citation2006). These electrode sites were chosen as they are the most effective at calculating engagement and are closest to Pope’s method (Bailey et al., Citation2006; Pope et al., Citation1995). The following formula was used: β/(α+γ) (Chaouachi et al., Citation2010). Its values range from 0 to 1; with higher values demonstrating higher levels of engagement/cognitive effort. We measured participants’ cognitive activity throughout the experimental task.

Procedure

The study was completed in several steps. First, subjects were recruited, and qualifying participants were then scheduled, for an appointment at the laboratory. Second, at the time of the appointment, each participant was greeted, we obtained their consent, and then they were brought to an experimentation room they were instructed to sit on a chair while the experimenter arranged the EEG montage. Third, after the EEG cap was placed, the participant was set in place for the experimental n-back task. Lastly, the participant had to fill out a posttest questionnaire on Qualtrics that evaluated their motivation to improve.

Analyses

Experimental data were analyzed using SPSS v.23. (SPSS Inc.). To gauge the absence of multicollinearity, a Pearson correlation matrix amongst the dependent variables (performance, motivation to improve, and task engagement) was produced, to assess their intercorrelations. As portrayed in , the associations are statistically non-significant. This indicates that multicollinearity or singularity is not present, and, thus, will not confound the results. Additionally, the relatively weak correlations alleviate redundancy considerations for the dependent variables. As such, we analyzed our experimental data using the following statistical tests.

Table 1. Correlations between performance, motivation to improve and task engagement.

Mixed analyses of variance (mixed ANOVAs) with repeated measures were conducted to compare the effect of continuous performance feedback content (quantitative feedback vs qualitative feedback) and feedback source (computer vs person vs none) on participants’ performance and their reactions (i.e., motivation to improve performance following feedback and task engagement) with continuous performance feedback content as the between and feedback source as the within-subjects condition.

A one-way repeated-measures analysis of variance (one-way ANOVA) was conducted to examine the impact of performance ratings on motivation to improve performance following a rating in the three different experimental conditions.Footnote1,Footnote2 Bonferroni pairwise posthoc comparisons were conducted in all our analyses to detect main and simple effects (interactions) (Jaccard et al., Citation1984). Violations of homogeneity of variances and sphericity were not detected using Mauchly’s test and Levene’s test; statistical corrections were not necessary for all the statistical tests (Field & Hole, Citation2002). Please note, since none of the interaction effects were statistically significant, descriptive statistics depicting these effects are omitted.

Results

The effect of continuous performance feedback content and feedback source on performance

A 2 × 3 mixed factorial analysis of variance (ANOVA) with one between-subject factor of continuous performance feedback content (quantitative and qualitative feedback) and three within-subject factors of feedback source (computer, person, and none) was conducted to examine the effects of the independent variables (continuous feedback content and feedback source) on the dependent variable (performance). Results demonstrated that there was a statistically significant main effect for continuous performance feedback (F (1, 34) = 4.115, p = .05, ηp2 = .11) and Bonferroni pairwise comparisons showed that participants in the quantitative feedback group (M = 81.43, SD = 4.84) scored higher than the qualitative feedback group (M = 77.89, SD = 5.60).

Our results also showed a statistically significant main effect of feedback source (F (2, 68) = 8.34, p < .01, ηp2 = .18). Bonferroni pairwise comparisons revealed a statistically significant difference between computer-mediated and person-mediated feedback (p < .01), as participants scored higher when they received feedback from a person (M = 82.28, SD = 6.88) than when they received feedback from a computer (M = 77.31, SD = 8.32). However, no differences were observed with the no-feedback condition (M = 79.39, SD = 5.43) (Please see and ).

Table 2. statistics and repeated measures mixed ANOVA results for feedback content and feedback source on performance scores.

The effect of quantitative feedback and feedback source on motivation to improve performance

A one-way repeated-measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) with three within-subject factors of motivation to improve (computer, person, and none) after receiving quantitative feedback (rating) was conducted to examine the effects of the independent variables (quantitative feedback and feedback source) on the dependent variable (motivation to improve after receiving quantitative feedback).

The results of the analysis showed there was no main effect of quantitative feedback on motivation to improve performance following the administration of quantitative feedback (rating), regardless of feedback source (F (1,17) = 2.21, p = .13, ηp2 = .12) (Please see ).

Table 3. statistics and F-test results for one-way repeated measures ANOVA on motivation to improve scores following quantitative feedback.

The effect of continuous performance feedback content and feedback source on motivation to improve performance

A 2 × 2 mixed factorial analysis of variance (ANOVA) with one between-subjects factor of continuous performance feedback content (quantitative and qualitative feedback) and one within-subject factor of feedback source (computer and person) was conducted to examine the effects of the independent variables, continuous performance feedback content and feedback source on the dependent variable motivation to improve performance following qualitative feedback. Please note that the scale is reversed, thus a score closer to 1 represents greater motivation and a score closer to 5 represents lower motivation.

Our results demonstrate that there was no statistically significant main effect of continuous performance feedback content (F (1, 34), = 0.89, p = .44, ηp2 = .02), but that there was a statistically significant main effect of feedback source (F (2, 68) = 20.19, p < .01, ηp2 = .37). Bonferroni pairwise comparisons showed that participants felt significantly less motivated to improve on the task when they received feedback from a computer (M = 2.87, SD = 0.95) than when they received feedback from a person (M = 2.21, SD = 0.96) (Please see ).

Table 4. statistics and repeated measures mixed ANOVA results for feedback content and feedback source on motivation to improve.

effect of continuous performance feedback content and feedback source on task engagement

A 2 × 3 mixed factorial analysis of variance (ANOVA) with one between-subjects factor of continuous performance feedback content (quantitative and qualitative feedback) and three within-subject factors of feedback source (computer, person, and none) was used to examine the effects of the independent variable, continuous performance feedback content and feedback source on the dependent variable task engagement.

Results show that there was no main effect for continuous performance feedback content (F (1, 31) = 0.61, p .43, ηp2 = .02). However, the data demonstrated that there was a statistically significant main effect for feedback source on task engagement (F (2, 62), = 4.028, p = .02, ηp2 = .12). Bonferroni pairwise comparisons were conducted across feedback sources and showed that only the mean difference between computer-mediated and person-mediated feedback was statistically significant (p = .02). Participants tended to be more engaged toward the task when they received feedback from a person (M = 0.66, SD = 0.21) than from a computer (M = .61, SD = 0.19). No differences were observed for the no-feedback condition (M = 0.62, SD = 0.19) (Please see ).

Table 5. statistics and repeated measures mixed ANOVA results for feedback content and feedback source on task engagement.

Discussion

The current study drew from the literature to examine how continuous performance feedback and feedback sources are associated with performance, motivation to improve, and task engagement. Two key findings emerged from our study.

First, we demonstrated that feedback content has a positive effect on performance. More precisely, participants in the quantitative feedback group performed better compared to individuals who only received qualitative feedback. Furthermore, in our study, we found that feedback content did not influence participants’ motivation to improve their performance and task engagement. This may be due in part to the feedback that was conveyed to participants. While the change-oriented feedback model has proven to be effective at changing people’s behaviors and fostering performance, it may be that the cues and messages that were used to address participants’ performance might not have equally covered all dimensions of change-oriented feedback (Carpentier & Mageau, Citation2013). Thus, the feedback content that was provided may have not been sufficiently motivating and engaging for participants. Future research could consider mobilizing different feedback cues and messages, or other feedback models (e.g., strengths-based feedback, objective feedback, evaluative feedback) and examine whether they can foster the above-mentioned outcomes (Aguinis et al., Citation2012; Johnson, Citation2013). Additionally, researchers could also include post-task surveys that would examine the extent to which participants would describe themselves as motivated and whether their motivation is congruent with the feedback cues and messages.

Second, concerning feedback sources, our results showed that people had higher levels of performance, motivation to improve, and task engagement when they received continuous performance feedback from a person rather than a computer. This may be because person-mediated feedback is more salient than computer-mediated feedback as managers can grab employees’ attention and convey the relevant information needed to reinforce desirable performance-related behaviors. Additionally, person-mediated feedback may have had a more powerful effect on the above-mentioned outcomes because this type of feedback is accompanied by affective and social cues that a computer cannot convey (Alder & Ambrose, Citation2005a).

Interestingly, this finding corroborates some of our knowledge of person-mediated feedback (Alder & Ambrose, Citation2005a; Johnson et al., Citation2022; Warrilow et al., Citation2020). But, this finding is also at odds with some empirical studies which have stated that person-mediated feedback would not be as effective (Baytak et al., Citation2011; Kluger & Adler, Citation1993; Sherafati et al., Citation2020; Zarei & Hashemipour, Citation2015). Further research on the boundary conditions of performance feedback sources is therefore warranted. For example, it may be that receiving person-mediated feedback is more effective under certain conditions, such as working on more complicated tasks. Computer-mediated feedback may be more effective for specific tasks. Nonetheless, the literature on performance feedback suggests that either way, electronic sources should not be the single source of performance feedback for employees and that managers should provide employees with feedback as well (Alder & Ambrose, Citation2005a). Thus, we suggest that future studies take a closer look at the interplay between computer-mediated feedback and other feedback sources (e.g., supervisors, colleagues, and clients).

Limitations and future research directions

The present study did not come without limitations. First, concerning our sample, even though the analyses were based on sufficient statistical power, the sample size by itself was low with respect to statistical significance as opposed to other studies that boast substantially higher sample sizes (e.g., Anseel et al., Citation2009; Kaymaz, Citation2011). Additionally, due to data constraints and limitations, the sample was composed of students. As they tend to share similar characteristics, our sample could be more homogenous, and less reflective of the general population. Thus, to increase external validity, we suggest that future research use more diversified samples, or directly target employees.

Second, despite the n-back task’s wide use in neuropsychological testing, it focuses on a single dimension of cognition, which is working memory. Even though working memory is a good predictor of job performance, employees not only use their working memory in the workplace but also in other executive functions such as problem-solving and cognitive flexibility (Diamond, Citation2013; Martin et al., Citation2020). Future research should examine the potential impacts of performance feedback with a greater variety of cognitive tasks that assess multiple dimensions of people’s executive functioning.

Third, even though the task was designed to be challenging for participants, the task could have been more challenging to allow for a greater range of performance scores. We do recognize that the magnitude of these improvements, albeit significant, were not very strong. Future research should consider putting participants in more challenging and complicated tasks to better capture participants’ performance scores.

Fourth, as rigorous as experiments can be, it is important to keep in mind that a laboratory experiment cannot fully recreate the richness of appraisals in a real context. For example, in our study, feedback (quantitative and qualitative) was administered right after a participant completed a block, whereas in real life there would be longer delays. Thus, it would be relevant for future researchers to examine how people perform in field settings where the richness and complexity of the dynamics and reactions to performance appraisal can be better captured.

Fifth, whereas some scholars have argued that receiving more frequent feedback may be conducive to more desirable behaviors at work (Salmoni et al., Citation1984), other research has suggested the opposite (Lam et al., Citation2011). These seemingly misaligned findings lead us to believe that indirect factors might impact the relationship between feedback frequency and performance (i.e., moderators and/or mediators). For example, in terms of feedback valence, receiving frequent positive feedback is more likely to lead to performance than receiving negative feedback which can often derail employees (Ilgen & Davis, Citation2000; Kluger & DeNisi, Citation1996). We therefore recommend including such characteristics in future research designs.

Finally, computer-mediated feedback might have had more impact on our participants’ performance and reactions if displayed in another format, like if an avatar personified a manager, instead of text in a pop-up window. For instance, user-experience research shows that people tend to comply more with instructions when they receive advice from an avatar with human-like traits, compared to when they read the same information through text (Op den Akker et al., Citation2016). This may provide researchers with important anchors to examine how avatars could be used in the context of performance management.

Conclusion

This study helped us better understand how people perform when they receive continuous performance feedback. We found that providing participants with quantitative and qualitative feedback continuously contributes to employee performance. Furthermore, we also observed that, compared to computer-mediated feedback, person-mediated feedback improved the motivational aspects of employee performance, as it increased motivation and engagement. In the end, continuous performance feedback systems are more likely to be successful in fostering performance if they prioritize the role of managers rather than the role of technology.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. The sample size for our analyses on performance, motivation to improve performance following feedback is 36. Our sample size for our analysis on task engagement was reduced to 32 because of low quality recordings for some participants.

2. Please consult Tables 2–5 for descriptive and inferential statistics tables.

References

- Adler, S., Campion, M., Colquitt, A., Grubb, A., Murphy, K., Ollander-Krane, R., & Pulakos, E. D. (2016). Getting rid of performance ratings: Genius or folly? A debate. Industrial and Organizational Psychology, 9(2), 219–252. https://doi.org/10.1017/iop.2015.106

- Aguinis, H. (2009). Performance management. Pearson Prentice Hall.

- Aguinis, H., Gottfredson, R. K., & Joo, H. (2012). Delivering effective performance feedback: The strengths-based approach. Business Horizons, 55(2), 105–111. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bushor.2011.10.004

- Alder, G. S., & Ambrose, M. L. (2005a). An examination of the effect of computerized performance monitoring feedback on monitoring fairness, performance, and satisfaction. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 97(2), 161–177. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.obhdp.2005.03.003

- Alder, G. S., & Ambrose, M. L. (2005b). Towards understanding fairness judgments associated with computer performance monitoring: An integration of the feedback, justice, and monitoring research. Human Resource Management Review, 15(1), 43–67. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hrmr.2005.01.001

- Alloway, T. P., & Copello, E. (2013). Working memory: The what, the why, and the how. The Australian Educational and Developmental Psychologist, 30(2), 105–118. https://doi.org/10.1017/edp.2013.13

- Alvero, A. M., Bucklin, B. R., & Austin, J. (2001). An objective review of the effectiveness and essential characteristics of performance feedback in organizational settings (1985-1998). Journal of Organizational Behavior Management, 21(1), 3–29. https://doi.org/10.1300/J075v21n01_02

- Anseel, F., Lievens, F., & Schollaert, E. (2009). Reflection as a strategy to enhance task performance after feedback. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 110(1), 23–35. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.obhdp.2009.05.003

- Bailey, N. R., Scerbo, M. W., Freeman, F. G., Mikulka, P. J., & Scott, L. A. (2006). Comparison of a brain-based adaptive system and a manual adaptable system for invoking automation. Human Factors: The Journal of the Human Factors & Ergonomics Society, 48(4), 693–709. https://doi.org/10.1518/001872006779166280

- Balcazar, F., Hopkins, B. L., & Suarez, Y. (1985). A critical, objective review of performance feedback. Journal of Organizational Behavior Management, 7(3–4), 65–89. https://doi.org/10.1300/J075v07n03_05

- Baytak, A., Tarman, B., & Ayas, C. (2011). Experiencing technology integration in education: Children’s perceptions. International Electronic Journal of Elementary Education, 3(2), 139–151. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ1052441

- Brecher, D., Eerenstein, J., Farley, C., & Good, T. (2016). Is performance management performing? Accenture.

- Budworth, M.-H., & Chummar, S. (2022). Feedback for performance development: A review of current trends. In S. Greif, H. Möller, W. Scholl, J. Passmore, & F. Müller (Eds.), International handbook of evidence-based coaching: Theory, research and practice (pp. 337–347). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-81938-5_28

- Cappelli, P., & Tavis, A. (2016). The performance management revolution. Harvard Business Review, 94(10), 58–67. https://hbr.org/2016/10/the-performance-management-revolution

- Carpentier, J., & Mageau, G. A. (2013). When change-oriented feedback enhances motivation, well-being and performance: A look at autonomy-supportive feedback in sport. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 14(3), 423–435. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2013.01.003

- Chaouachi, M., Chalfoun, P., Jraidi, I., & Frasson, C. (2010). Affect and mental engagement: Towards adaptability for intelligent systems. Proceedings of the 23rd International FLAIRS Conference. https://www.iro.umontreal.ca/~frasson/FrassonPub/FLAIRS-2010-Chaouachi-et-al.pdf

- Charland, P., Léger, P.-M., Sénécal, S., Courtemanche, F., Mercier, J., Skelling, Y., & Labonté-Lemoyne, E. (2015). Assessing the multiple dimensions of engagement to characterize learning: a neurophysiological perspective. Journal of Visualized Experiments: JoVe, 101(101), 52627. https://doi.org/10.3791/52627

- Daniels, A. C., & Bailey, J. S. (2014). Performance management: Changing behavior that drives organizational effectiveness (5th ed.). Performance Management Publications.

- Deloitte. (2017a) . Rewriting the rules for the digital age: 2017 Deloitte global human capital trends. Deloitte University Press.

- Deloitte. (2017b). Research report: Continuous performance management. Deloitte Development LLC.

- Diamond, A. (2013). Executive functions. Annual Review of Psychology, 64(1), 135–168. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-113011-143750

- Doucet, O., Giamos, D., & Lapalme, M.-È. (2019). Peut-on gérer la performance et le bien-être des employés? Une revue de littérature et quelques propositions de recherche sur les pratiques innovantes en gestion de la performance [Can we manage employee performance and well-being? A literature review and propositions on innovative performance management practices]. Ad Machina: L’avenir de l’humain Au Travail, 3, 165–176. https://doi.org/10.1522/radm.no3.1106

- Fairclough, S. H., Gilleade, K., Ewing, K. C., & Roberts, J. (2013). Capturing user engagement via psychophysiology: Measures and mechanisms for biocybernetic adaptation. International Journal of Autonomous and Adaptive Communications Systems, 6(1), 63–79. https://doi.org/10.1504/IJAACS.2013.050694

- Faul, F., Erdfelder, E., Lang, A.-G., & Buchner, A. (2007). G*power 3: A flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behavior Research Methods, 39(2), 175–191. https://doi.org/10.3758/BF03193146

- Fedor, D. B., Eder, R. W., & Buckley, M. R. (1989). The contributory effects of supervisor intentions on subordinate feedback responses. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 44(3), 396–414. https://doi.org/10.1016/0749-5978(89)90016-2

- Field, A., & Hole, G. (2002). How to design and report experiments. Sage.

- Gajewski, P. D., Hanisch, E., Falkenstein, M., Thönes, S., & Wascher, E. (2018). What does the n-back task measure as we get older? Relations between working-memory measures and other cognitive functions across the lifespan. Frontiers in Psychology, 9, 2208. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.02208

- Garber, P. R. (2004). Giving and receiving performance feedback. HRD Press.

- Ilgen, D., & Davis, C. (2000). Bearing bad news: reactions to negative performance feedback. Applied Psychology, 49(3), 550–565. https://doi.org/10.1111/1464-0597.00031

- Jaccard, J., Becker, M. A., & Wood, G. (1984). Pairwise multiple comparison procedures: A review. Psychological Bulletin, 96(3), 589–596. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.96.3.589

- Johnson, D. A. (2013). A component analysis of the impact of evaluative and objective feedback on performance. Journal of Organizational Behavior Management, 33(2), 89–103. https://doi.org/10.1080/01608061.2013.785879

- Johnson, D. A., Johnson, C. M., & Dave, P. (2022). Performance feedback in organizations: understanding the functions, forms, and important features. Journal of Organizational Behavior Management, 1(1), 1–26. https://doi.org/10.1080/01608061.2022.2089436

- Kaymaz, K. (2011). Performance feedback: Individual based reflections and the effect on motivation. Business and Economics Research Journal, 2(4), 115–134. https://www.berjournal.com/performance-feedback-individual-based-reflections-and-the-effect-on-motivation-2

- Kluger, A. N., & Adler, S. (1993). Person- versus computer-mediated feedback. Computers in Human Behavior, 9(1), 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1016/0747-5632(93)90017-M

- Kluger, A. N., & DeNisi, A. (1996). The effects of feedback interventions on performance: A historical review, a meta-analysis, and a preliminary feedback intervention theory. Psychological Bulletin, 119(2), 254–284. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.119.2.254

- Lam, C. F., DeRue, D. S., Karam, E. P., & Hollenbeck, J. R. (2011). The impact of feedback frequency on learning and task performance: Challenging the “more is better” assumption. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 116(2), 217–228. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.obhdp.2011.05.002

- Lampe, J. H., Schäffer, U., & Schaupp, D. (2021). The performance effects of narrative feedback (SSRN Scholarly Paper No. 3825100). Social Science Research Network. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3825100

- Lechermeier, J., & Fassnacht, M. (2018). How do performance feedback characteristics influence recipients’ reactions? A state-of-the-art review on feedback source, timing, and valence effects. Management Review Quarterly, 68(2), 145–193. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11301-018-0136-8

- Martin, N., Capman, J., Boyce, A., Morgan, K., Gonzalez, M. F., & Adler, S. (2020). New frontiers in cognitive ability testing: Working memory. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 35(4), 193–208. https://doi.org/10.1108/JMP-09-2018-0422

- Mikulka, P. J., Scerbo, M. W., & Freeman, F. G. (2002). Effects of a biocybernetic system on vigilance performance. Human Factors: The Journal of the Human Factors & Ergonomics Society, 44(4), 654–664. https://doi.org/10.1518/0018720024496944

- Op den Akker, H. J. A., Klaassen, R., & Nijholt, A. (2016). Virtual coaches for healthy lifestyle. In A. Esposito & L. C. Jain (Eds.), toward robotic socially believable behaving systems—volume II : Modeling social signals (pp. 121–149). Springer International Publishing.

- Pinder, C. C. (2008). Work motivation in organizational behavior (2nd ed.). Psychology Press.

- Pope, A. T., Bogart, E. H., & Bartolome, D. S. (1995). Biocybernetic system evaluates indices of operator engagement in automated task. Biological Psychology, 40(1), 187–195. https://doi.org/10.1016/0301-0511(95)05116-3

- Pulakos, E. D., Mueller-Hanson, R., & Arad, S. (2019). The Evolution of performance management: searching for value. Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior, 6(1), 249–271. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-012218-015009

- Runnion, A., Johnson, T., & McWhorter, J. (1978). The effects of feedback and reinforcement on truck turnaround time in materials transportation. Journal of Organizational Behavior Management, 1(2), 110–117. https://doi.org/10.1300/J075v01n02_01

- Salmoni, A. W., Schmidt, R. A., & Walter, C. B. (1984). Knowledge of results and motor learning: A review and critical reappraisal. Psychological Bulletin, 95(3), 355–386. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.95.3.355

- Scharinger, C., Soutschek, A., Schubert, T., & Gerjets, P. (2017). Comparison of the working memory load in n-back and working memory span tasks by means of eeg frequency band power and P300 Amplitude. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 11, 11. https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fnhum.2017.00006

- Sherafati, N., Largani, F. M., & Amini, S. (2020). Exploring the effect of computer-mediated teacher feedback on the writing achievement of Iranian EFL learners: Does motivation count? Education and Information Technologies, 25(5), 4591–4613. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-020-10177-5

- Shkoler, O., Tziner, A., Vasiliu, C., & Ghinea, C.-N. (2021). A moderated-mediation analysis of organizational justice and leader-member exchange: cross-validation with three sub-samples. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 12. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.616476

- Sleiman, A. A., Sigurjonsdottir, S., Elnes, A., Gage, N. A., & Gravina, N. E. (2020). A quantitative review of performance feedback in organizational settings (1998-2018). Journal of Organizational Behavior Management, 40(3–4), 303–332. https://doi.org/10.1080/01608061.2020.1823300

- Solomon, L. (2016). Two-thirds of managers are uncomfortable communicating with employees. Harvard Business Review. https://hbr.org/2016/03/two-thirds-of-managers-are-uncomfortable-communicating-with-employees

- Tagliabue, M., Sigurjonsdottir, S. S., & Sandaker, I. (2020). The effects of performance feedback on organizational citizenship behaviour: A systematic review and meta-analysis. European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 29(6), 841–861. https://doi.org/10.1080/1359432X.2020.1796647

- Tekian, A., Watling, C. J., Roberts, T. E., Steinert, Y., & Norcini, J. (2017). Qualitative and quantitative feedback in the context of competency-based education. Medical Teacher, 39(12), 1245–1249. https://doi.org/10.1080/0142159X.2017.1372564

- Traynor, S., Wellens, M. A., & Krishnamoorthy, V. (2021). Continuous performance management. In S. Traynor, M. A. Wellens, & V. Krishnamoorthy (Eds.), SAP success factors talent: Volume 1: A complete guide to configuration, administration, and best practices: Performance and goals (pp. 613–643). Apress. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4842-6600-7_13

- Warrilow, G. D., Johnson, D. A., & Eagle, L. M. (2020). The effects of feedback modality on performance. Journal of Organizational Behavior Management, 40(3–4), 233–248. https://doi.org/10.1080/01608061.2020.1784351

- Whitaker, B. G., & Levy, P. (2012). Linking feedback quality and goal orientation to feedback seeking and job performance. Human Performance, 25(2), 159–178. https://doi.org/10.1080/08959285.2012.658927

- Wilder, D. A., Austin, J., & Casella, S. (2009). Applying behavior analysis in organizations: Organizational behavior management. Psychological Services, 6(3), 202–211. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0015393

- Wine, B., & Pritchard, J. K. (Eds.). (2018). Organizational behavior management: The essentials. Hedgehog Publishers.

- Zarei, A., & Hashemipour, M. (2015). The effect of computer-assisted language instruction on improving EFL Learners’ autonomy and motivation. Journal of Applied Linguistics, 1, 40–58. http://ftp.ikiu.ac.ir/public-files/profiles/items/090ad_1440271469.pdf

- Zeng, M. (2016). What alternative performance appraisal methods have companies used to replace forced rankings?. https://ecommons.cornell.edu/handle/1813/74454

Appendix

Feedback Script Sample

The feedback script is based on Carpentier and Mageau’s (2013) and Mouratidis’s (2010) papers. Here were the following criteria we used to construct the feedback scripts:

Being empathetic:”We understand that your performance is not optimal at the moment. However, the good news is that there is room for improvement. Please remember that the n-back task is not an easy cognitive task, it may be confusing at times”

Paired with choices or solutions: “Here is some advice! (a) Take a deep breath, rest your eyes for 30 seconds and clear your thoughts. (b) You can increase your score by paying close attention to the stimuli that match together. (c) It is best to rote memorize the sequence. *Also takes into account step 4.

Based on clear and attainable objectives: “You can definitely increase your performance in the next block! If you do better on 5 more sequences you will have had a major improvement !”

Avoiding person related statements: *There are no statements that personally attack the participant.

Pairing the feedback with tips on how to improve future performance: (see recommendation 2).

Being delivered promptly: Feedback will be delivered after every block

Being delivered privately: Feedback is only delivered to the participant through his screen (Computer) and in a soundproofed room where the participant is alone (Human).

In a considerate tone of voice: Feedback is written in the most professional manner.