Abstract

People with severe self-harming behavior and histories of lengthy psychiatric inpatient admissions can represent a challenge to care providers. This interview-based study illuminates healthcare provider experiences (n = 12) of Brief Admission (BA) among self-harming individuals, with >180 days of psychiatric admission the previous year. Qualitative content analysis revealed that providers experienced benefits of increased predictability, and a shift from trigger and conflict to collaboration with individuals admitted to BA. Staff participants expressed an increased sense of safety and a strengthened link between inpatient and outpatient caregiving. Results indicated that BA is a promising intervention for self-harming individuals with extensive psychiatric histories.

Background

People with prolonged and imminent suicidal ideation and severe self-harming behavior can be a challenge to treat within general psychiatric care (Holth et al., Citation2018; O'Connor & Glover, Citation2017). These individuals often present with complex mental illness including borderline personality disorder (BPD). Suffering is pervasive and mortality rates are high despite extensive inpatient care (Holth et al., Citation2018; Lieb, Zanarini, Schmahl, Linehan, & Bohus, Citation2004).

Negative attitudes towards self-harming individuals are common among healthcare providers (Karman, Kool, Poslawsky, & van Meijel, Citation2015; O'Connor & Glover, Citation2017). Frequent and lengthy admissions related to difficulties at discharge may lead to emotionally challenging situations for psychiatric care providers. A recent study conducted in Norway describes how providers may set boundaries towards the individual seeking healthcare that are either too strict (e.g. rejecting responsibility for the individual) or lacking limitation (e.g. permitting extensive admission without clear benefits) (Holth et al., Citation2018). Perceptions of individuals with self-harm as challenging, evoking irritation, anger, and frustration as well as hopelessness among staff are common. However, they undermine the very essence of psychiatric nursing as a person-centered approach with focus on building and maintaining relationships that are essential for the delivery and outcome of care (Kristiansen, Hellzén & Asplund, Citation2010; Molin, Graneheim & Lindgren, Citation2016). Education, support, structure, and clarity in inpatient systems may contribute to reduced negative attitudes towards self-harming individuals and lead to a more mutually beneficial experience of psychiatric inpatient care (Karman et al., Citation2015; Saunders, Hawton, Fortune, & Farrell, Citation2012).

Brief self-referral initiatives (also called brief admission, self-admission, or patient-controlled admission) have evolved as a promising alternative to lengthy and unstructured psychiatric admissions for those diagnosed with BPD (Helleman, Goossens, Kaasenbrood, & van Achterberg, Citation2014a), eating disorders (Strand, Gustafsson, Bulik, von, & Juhlin, Citation2015); schizophrenia, and bipolar disorder (Moljord et al., Citation2017; Sigrunarson, Moljord, Steinsbekk, Eriksen, & Morken, Citation2017; Thomsen et al., Citation2018). These structured crisis management programs are founded on predefined agreements regulating admission length and services included. Autonomy is promoted by removing gatekeeping mechanisms and encouraging self-admission.

Brief Admission (BA) is a standardized crisis-management intervention in which individuals with recurrent self-harm at risk for suicide and three or more diagnostic criteria of BPD, can refer themselves to brief hospital admissions after the negotiation of a contract. BA is currently being evaluated in a randomized controlled trial (Brief Admission Skåne Randomized Controlled Trial; BASRCT; Liljedahl, Helleman, Daukantaité, Westrin, & Westling, Citation2017) within Psychiatry Skåne, a county in southern Sweden serving 1.3 million inhabitants.

The BA contract gives the individual access to BA and contains information about the parameters and routines of BA as well as individualized components of care such as goals of the BA and strategies to reach those goals. It states the maximum dose of the intervention (maximum 3 nights per admission and three admissions per month), what is offered to the individual during BA – up to two daily conversations with ward staff (15–20 minutes each) and participation in activities organized at the ward. Contracts also state what is not offered (medication, consultation with a ward physician/psychiatrist, and changes in treatment). Additionally, the contract describes the individual's commitments during BA. Typical examples are to bring and administer own medication, not to harm themselves or others, not be intoxicated or violent. If individuals are unable to maintain these commitments during BA, the result is early discharge from BA alongside a discussion of what went wrong. The prematurely discharged individual is welcome to return for future BAs as soon as they can learn and describe what skills will be necessary to maintain BA commitments going forward. This typically takes place in a review of the BA contract, which takes place every 6 months, at which time the individual and their outpatient clinician meet with BA ward staff to discuss progress.

When BA is added to an individual’s treatment plan, a negotiation discussion takes place. During the negotiation discussion the contract is introduced and signed by the individual receiving BA and by BA staff who leads the conversation and signs as a witnesses. The individual is informed about the intervention, and all individual adaptations are discussed and incorporated into the contract. Examples are goals for using BA, early signs of needing BA, what to do to reduce emotional arousal, and so (Liljedahl, Helleman, Daukantaitė, & Westling, Citation2017).

The clinical approach of staff is carefully described during training that all staff must complete prior to delivering BA. The approach is characterized by being welcoming with warmth, enthusiasm, acceptance, genuineness, openness, validation of current difficulties that individuals experience and a willingness to collaborate on equal terms. Prospective BA staff are also trained on the BA care providing structure, ward routines for admission, discharge as well as premature discharge (Liljedahl, Helleman, Daukantaitė, et al., Citation2017). Even with a BA contract, the overall responsibility for the psychiatric treatment remains with the individual, in collaboration with their previously-ongoing outpatient care providers. A person with a BA contract continues to have access to other types of psychiatric admission in addition to their outpatient care as usual.

Included in the BASRCT are people aged 18–60 years with current self-harm and/or recurrent suicidal behavior, at least three diagnostic criteria for BPD (DSM-5; American Psychiatric Association, Citation2013), and hospital admission at least 7 days or presenting to the emergency department at least three times during the last 6 months. Study participants were randomized to the intervention group (BA alongside treatment as usual; TAU) or control group (TAU) with access to BA after completing 12 months in BASRCT.

People with a wide range of previous experience of hospital admissions were included in BASRCT, ranging from 7 to 331 days the year before inclusion in BASRCT. Of fourteen participants with >180 days of psychiatric admission the year prior to inclusion, eight were randomized to the intervention group and six to the control group. Of these, 11 have negotiated a BA contract during or after the intervention year, and were therefore eligible to add BA to their treatment plan. The individuals were diagnosed with 2–7 disorders (mean = 3.5 (median = 3) diagnoses, SD ± 2.5). These included BPD, (n = 2, 18%), depressive disorder (n = 6, 54.5%), panic disorder (n = 3, 27.3%), PTSD (n = 5, 45.5%), ADHD (n = 3, 27.3%), autism (including Asperger’s Disorder) (n = 2, 18%), among other diagnoses. All 11 participants reported suicidal ideation during last month and self-harming behavior. Ten (91%) reported suicidal behavior during the last year.

Overall, little research has been published addressing health care providers’ experiences of treating people with recurrent self-harming behavior at risk for suicide, with multiple psychiatric diagnoses. The present study focuses on outpatient and inpatient healthcare providers who have cared for individuals with extensive experience of hospital admissions and severe self-harm using BA. Qualitative research on personal experiences of BA from the perspective of health care providers will be an important complement to quantitative results forthcoming in the BASRCT and promote a deeper understanding of BA for individuals with a history of extensive psychiatric inpatient care.

Aim

The aim of this study was to illuminate staff experiences of providing BA to individuals with self-harm at imminent risk for suicide with histories of more than 180 days of general psychiatric admissions during the 12 months before they received access to BA.

Methods

Design

This is a qualitative inductive interview study, examining the perspectives of health care providers working with BA. Subjective realities shared in interviews are illuminated and interpreted, where the health care provider is viewed in their role providing BA as well as providing treatment as usual. Knowledge is gained in the interactive process between the researcher and the participant (Dahlgren, Emmelin, & Winkvist, Citation2007).

Setting and participants

All health care providers (n = 98) at wards providing BA for one or several of the 11 patients who had > 180 days of psychiatric hospital admission prior to negotiating a BA contract within the BASRCT were approached for study participation. Recruitment was described with a focus on how staff experienced providing care to the most severely ill individuals receiving BA. Outpatient care contacts (n = 18) for the same 11 patients were approached. They included nurse’s assistants, nurses, psychiatrists, psychologists, social workers, and an occupational therapist.

A total of 116 prospective participants were invited to participate by email, followed up by telephone calls to those who responded with interest to participate. One reminder email was sent out to outpatient care staff due to low initial response. provides a description of study participants (n = 12).

Table 1. Overview of study participants.

Data collection

In-depth face-to-face interviews (lasting 48–74 minutes) were held at a time convenient for the participants in the period June–September 2018 in private locations at their workplace. A semi-structured interview guide was developed for the study, focusing on how participants experienced working with BA related to their preexisting expectations and to safety aspects of BA, along with thoughts regarding potential improvements and adaptations of BA. After a pilot interview, included in the analysis, the interview guide was further refined to improve interview flow. Interviews focused on following participants using non-leading, open-ended questions to encourage participants to openly convey their viewpoints. Interviews ended with asking participants to consider anything important that they had not been asked.

Data analysis

Audio-recorded interviews were transcribed and analyzed with qualitative content analysis (Graneheim & Lundman, Citation2004) to systematically illuminate and interpret the latent content of shared experiences of working with BA. Division into meaning units, condensing and coding were performed by RL and discussed with KL until joint agreement was achieved. Identification of latent sub-themes and themes were derived from the data as a result of a process of reflection and discussion between coauthors. Data was managed using the software Open Code (ICT Services & System Development & Division of Epidemiology & Global Health, Citation2013).

Ethical considerations

This study was granted ethical approval (2018/313). All participants were given oral and written information about the study and signed informed consent prior to interviews.

Results

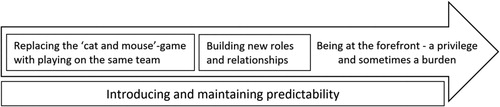

Analysis revealed four themes () with subthemes (). These are described below including quotes marked with a number indicating participant.

Table 2. Overview of themes and subthemes.

Replacing the “cat and mouse”-game with playing on the same team

With the introduction of BA, participants described experiencing a shift from destructive patterns of power struggles between staff and patients. Participants described the former “cat-and-mouse-game,” in which staff tried to guard patients to protect them from self-harm. They spoke about how patients then tried to evade staff. This vicious cycle was sensed to be replaced by partnership and the joy in being able to offer meaningful help.

My patients who have had BA often say how they sense that there is a…a collaboration between them and the staff. It’s no longer a fight. (I 12)

Reducing triggers and conflicts

Participants described experiences of BA in relation to how general psychiatric admissions triggered destructive behavior in individuals with self-harming behavior. According to the participants’ experiences prior to the implementation of BA, individuals were too often faced with mistrust, ejected from their bed at the emergency unit or experiencing uncertainty around the length of their admission. They said that individuals therefore had been forced to put energy into strategies to be and stay admitted (including self-harm) rather than to focus on getting well. Participants expressed how this along with an unclear division of responsibility led to lengthy admissions and frustration between staff and patients.

On the one hand you take responsibility away from patients, and then you demand that patients take their own responsibility. And you sort of get angry and irritated when they don’t. (I 12)

Participants shared experiences of disrespectful and unwelcome approaches from fellow staff towards patients presenting for repeated lengthy general psychiatric admissions. These staff behaviors were described as arising from fatigue and misplaced frustration in not being able to help individuals to become well. Participants expressed how colleagues implied that patients self-harmed to get attention and “just to be deliberately uncooperative with staff” (I 9) and therefore consistently should be ignored.

Attempts to have surveillance and control to prevent self-harm among individuals on a general psychiatric admission was described as “mission impossible”. Participants talked about staff overcontrol creating a false sense of security for staff while in fact contributing to trigger escalation of self-harm behaviors amongst individuals admitted. They described hesitation towards removing any item that could potentially be used for cutting, such as glass-framed pictures and light bulbs as well as restricting access to items that could be used for strangulation like mobile phone chargers, bras, and nylons. They sensed that patients responded to these increasing limitations by using any opportunity to self-harm. Participants expressed concern regarding the end result of trying to create a completely safe environment.

Are they supposed to run around naked with helmets on their heads? And have, like, no things anywhere? Rubber cutlery, or what? (I 8)

Being able to meet patients’ needs

With the introduction of BA participants described how they were able to encourage individuals to seek and receive immediate help as needed. Participants talked about greeting individuals admitted to BA with a sincere welcome, and witnessing improvement within days. They described experiencing joy and fulfillment when the open clinical approach of BA contributed to individuals being more relaxed and less inclined to cling to hospital admission. That approach was by one participant considered to “make all the difference in the world” (I 8)

The nicest thing is to see how they feel better after only 3 days. Many patients may be admitted for 6 months, even for a year. And then you think, “nothing is happening”. Here you notice a difference within 3 days. How they just say “thank you for this time”, and leave. (I 1)

Participants described experiencing BA as the missing link between compulsory general admission where patients´ all rights were taken away, and leaving individuals without care to fend for themselves.

Rather, BA serves as a small stopover. And, like, it gets a little easier to both seek help early and be discharged. (I 12)

Building new roles and relationships

Participants described that the characteristics of BA contributed to reduced hierarchy among staff and patients. They described experiencing how this in turn improved their relationships with individuals admitted to BA as patients were given increased responsibility for their autonomy and well-being.

Giving back what was taken away

Participants expressed that with BA the link to reality and dignity was rightfully returned back to the individual receiving care. Daring to truly trust individuals with serious self-harm behavior to be able to take responsibility over their own well-being and safety was considered instrumental. With BA, staff had to trust the individual’s ability to handle their own medications and ensure that other individuals could not access them.

Participants shared experiences of how individuals admitted to BA grew with their successes, gained hope and resumed contact with their lives, due to BA.

They may come in on BA and feel that they have made it. And can go home after 3 days and continue with their lives. (…) You get them out of this healthcare system to take care of themselves. (I 4)

Participants described experiencing how individuals admitted to BA became more independent as they were able to take active part in decision-making and influence the care they received. Also, they said that they sensed that the framework of BA contributed to giving back access to individuals’ human rights and dignity that were lost by being forced to receive compulsory care. Writing and signing a binding contract with individual wishes and needs formulated in a stable condition, which is a component of BA, was said to be a concrete way of granting individuals influence over situations characterized by instability.

Even though you are in a very poor mental condition, you still don’t have everything related to free will, or your own point of view on things, taken away from you. (I 8)

Participants spoke about the beneficial effects of how individuals admitted to BA could experience the challenges of a normal adult life. Participants described perceiving that individuals admitted to BA grew as they were no longer “overly protected” from uncomfortable real-life feelings, such as the guilt of leaving children or pets to be taken care of by others while admitting themselves to BA (I 12).

A less hierarchical system: Redefining roles

Particularly, the nurses’ aides at the wards described how hierarchical structures were loosened with increased independence of psychiatric nursing staff working with BA. They said that this was achieved by having less direct involvement with physicians. Nursing staff talked about how they felt that this resulted in a more effective use of their training and experience, strengthening their own professionalism.

We have more responsibility. Or at least that’s how you feel. Since you don’t ask the physician for advice about things, and you’re not required to inform physicians about things… And so, in that way it’s a different job for us. Actually, in that way you become a bit more independent. You feel that you can make your own decisions regarding BA. (I 1)

Participants described experiencing individuals admitted to BA to be profoundly different from the passive individuals they had experienced on general psychiatric admissions; now they were active, informed and influential. They perceived individuals to be different when they arrived to the BA ward, proud to have decided to admit themselves, coming and going for 3 days, taking care of their own medicines and appointments. Staff experienced less frustration in general as they adapted to individuals´ needs and wishes, instead of the other way around. Participants also described experiences of a strengthened link and interest between staff from outpatient and inpatient care within BA, especially emphasized by outpatient care staff.

Participants described experiencing that BA contributed to greater harmony in how colleagues approached individuals admitted to BA. They spoke about how staff used to be experienced as either limitless or extremely firm in their way of nursing. With BA participants experienced a more balanced mix of requiring responsibility of individuals while still validating the situation and condition in which they presented.

There is a kind of balance. We are not being close-minded, but both/requiring responsibility and validating the situation/are present in BA, … in how you work with the patients. (I 10)

Meeting the person behind the patient

Participants described perceiving that individuals admitted to BA were in a more stable condition, less nervous, more themselves and easier to connect with compared to being on regular psychiatric admissions. They said that on regular admissions these individuals are typically highly suicidal with high levels of anxiety. As a result, participants described how they saw individuals admitted to BA in a new light as they got to know them better.

Now I don’t think about it that much anymore, but I know it was like that in the beginning. Right, “you don’t always feel this bad”. Because often we have gotten them in here when they are in their very worst shape and when it is, like, chaos. (I 2)

Introducing and maintaining predictability

Participants emphasized the value of predictability for staff as well as for individuals admitted to BA, arising from the structured approach of BA. They experienced how predictability created a sense of safety from knowing what to expect and experiencing few unforeseen events during admissions. Also, participants talked about how they sensed that BA removed destructive patterns associated with unpredictability. The latter involved experiences of individuals being difficult to discharge because of a high level of suicide risk always being present.

Leaning on structure

Participants emphasized the importance and value of the structured approach in their work with BA. For example, two scheduled appointments per day during admission were experienced as giving persons on BA more opportunities to connect with staff compared to patients admitted to an ordinary hospitalization.

I almost believe that they get more contact as BA is so very structured and predictable… Because they never need to wonder if they are seen or if anyone cares and will talk to them. Because they know that at six o’clock we have a BA-appointment. (I 12)

Participants shared experiences of how the framework of BA, including the preparatory BA education and the contract negotiation provided concrete knowledge on how to approach individuals admitted to BA. The work with BA was experienced as having positive effects on approaching ‘difficult’ patients in particular, and all patients more generally.

Participants experienced that the fixed and articulated structure of BA was well-tailored to meet the challenges of individuals with traits of BPD and self-harming behavior. The fact that individuals admitted to BA had co-written the contract in a more stable condition was perceived as a help for all parties to stick to the structure as agreed regarding the clinical management of self-harm, consistent with the ongoing DBT-treatment that many individuals were concurrently receiving.

Many of those that we have signed contracts with have, you know, great difficulty handling impulses, strong thoughts of self-harming, and many also have, like, constant thoughts of maybe not wanting to live. And that’s why I think it’s so important that it is clear to them, that they can’t get around it. (I 3)

Looking ahead, beyond the inflexible framework of a clinical trial, participants talked about the importance of keeping the structure of BA and the link between in- and outpatient care contacts. They also talked about how the BA framework and approach should be used as a model for other psychiatric interventions, and how knowing what to expect should be the rule for all patients, not only those offered BA.

Sensing safety and security

Participants described experiencing a sense of safety when individuals admitted to BA responded positively to trust and responsibility. Related to this, participants perceived that BA contributed to a more sustainable sense of safety reaching beyond the walls of the ward, as compared to the more limited physical safety measures used within general admission. Individuals admitted to BA were experienced as more stable and predictable since they sought help before hitting rock bottom, which in turn allowed staff to feel less stressed. Participants expressed feeling safe to leave individuals admitted to BA alone on their rooms with medicines and sharp items like razor-blades, and shared examples of not having to count the minutes when patients showered.

We tell them “now we have a contract, and if you violate it you will be discharged. You are welcome again tomorrow, but you will have to go home today and then you have neglected one of your admissions this month and you will only have two left.” So the safety is also in them not wanting to use them [brief admissions] up if they aren’t here. (I 5)

Participants said that they experienced BA as an effective safety net. Participants in outpatient care described planning strategies together with individuals in case of a crisis where admitting themselves to BA was part of the plan. They spoke about how knowing BA was accessible created a sense of security among individuals with BA contracts. In turn, according to participants, this resulted in individuals feeling less need to admit themselves to BA. Participants from outpatient care emphasized that a significant factor generating reassurance with BA was not the admissions as such, but the mere accessibility of BA should it be needed.

Stepwise testing & expanding limits – Learning by doing and sometimes failing

Participants described BA as a practice for individuals to manage their own well-being; a step-wise pedagogical transfer from inpatient care to self-care. Even if 3 days were not enough to be cured, it was perceived as being sufficient to give individuals time to recover “from 20% to 90% wellness” (I 5). Participants talked about how regular contract revisions every 6 months served as an effective tool to gradually develop and evaluate strategies together. They said that even small steps of progress became detectable through this process. The possibility for all parties to acknowledge progress was viewed as important. Again, participants from outpatient care shared experiences of extensive use of BA in their therapeutic work, as part of crisis management, stressing the benefits of a BA contract even when BA was not used actively.

Participants shared experiences of how severely ill individuals sometimes were not able to manage BA. One participant said that she felt a sense of failure when an individual on BA had to be admitted as a regular patient via the emergency department. Participants also shared experiences of how they used BA to offer hope to individuals in situations of failure, in a learning-by-doing/trial and error approach to test different solutions and issues with BA. Participants referred to BA as something very exciting that should be tested even by those with a history of very long psychiatric admissions.

It always turns into some sort of, how should I put it, detective-work. “this doesn’t work now” but that door is not forever closed. No, but we might have to dig somewhere else… And that is also a different kind of attitude towards persons who so easily fall into ‘I am a hopeless case’ or “I will never get well”. And so it is possible to change that as well. (I 9)

Participants talked about being impressed by how individuals managed BA despite a potentially triggering environment, as they were admitted alongside very ill patients. Participants also experienced how individuals on BA were reminded of themselves in the worst shape and experienced pride of not being there anymore, while at the same time being able to offer hope as role models to fellow patients on general admission. BA was also experienced as testing limits for the staff themselves and opening their minds to reevaluate routines and own beliefs.

Being at the forefront – A privilege and sometimes a burden

Participants emphasized the privilege of being able to work with preventive care, providing well-needed help and hope to individuals with a history of extensive psychiatric admission. They shared experiences of a practical and ethical struggle when implementing a new intervention within the old framework and stressed the importance of enthusiastic support.

Health care in a “sick-care” system

Participants described how BA challenged old belief systems that suicidal individuals belong in hospital, unable to care for themselves. Participants shared experiences of how the implementation of BA had made them feel concerned about safety and potential effects of mixing patients on different admissions. They had feared that jealousy would arise between patient groups.

Will this become some sort of a small elite patient group? And then the other patients become some kind of B-team, who are here involuntarily, or on long admissions? (I 2)

Participants said that they liked the fact that BA focused on building competence for long-term healthy living by protecting against self-harm at home instead of locking persons into institutions for temporary protection.

You are supposed to feel safe out there. At home. Really. Because that is where you are supposed to build up your life. Not here. (I 7)

Participants shared experiences of how the hospital environment sometimes awakened trauma from previous general psychiatric admissions, triggering suicidal thoughts and thereby making it impossible for some persons to use BA.

Psychiatry has a problem, which is affecting our patients. In a perfect world, it simply would not need to be there. (I 9)

Participants described experiences of ethical dilemma when the ward was full and they had to prioritize individuals admitted to BA over those on general admission, and overhearing individuals on general admission discussing if those admitted to BA are worth more than others.

you have to start choosing between these 16 persons. Who can we send on leave or who can we discharge, or who can we move to another department? And then… Then, as staff, I find that you end up in a dilemma. Because then my thinking shifts. Okay, these 16 patients who are already admitted and so sick, where is their dignity in this? (I 4)

Participants also described how individuals admitted to BA were understanding when scheduled BA conversations with ward staff had to be canceled and how persons decided to leave BA early due to turbulence at the ward. Relating to this, participants argued strongly for an unlocked BA environment that could be beneficial for individuals admitted to BA and for other patients as well as for staff.

Relying on enthusiasm

Participants experienced comfort from an enthusiastic and knowledgeable project leader to turn to for support and advice.

Just knowing that you may call the project leader even in the evening and just state either the research number or initials, and she knows exactly who it is. (I 5)

Also, participants emphasized their own and others joy and inspiration of working with BA, indicating that BA may be the beginning of a major reform in psychiatry. Participants mentioned the importance of the project leader being a medical doctor with authority to overcome hierarchy-related barriers, and lifted the importance of enthusiastic professionals being involved in BA for the successful implementation and impact of the project.

It has been very fortunate, to have this group at the department who really want to work with this. I mean, there has been some form of own drive, own motivation among the staff doing this. (I 8)

Discussion

The aim of this study was to illuminate staff experiences of providing BA to individuals with self-harm, risk for suicide, and extensive previous psychiatric admission. In semi-structured interviews outpatient and inpatient staff shared experiences of BA establishing a beneficial foundation of predictability, which was an essential factor in shaping of positive attitudes towards individuals with self-harm behavior (O'Connor & Glover, Citation2017). Participants emphasized that they could lean on the pre-established structure of BA, providing them a framework on how to meet “difficult patients” with traits of BPD and self-harm. Importantly, shaping positive attitudes is recognized as a key component for successful implementation of BA (Helleman, Goossens, Kaasenbrood, & van Achterberg, Citation2014b; Helleman, Lundh, Liljedahl, Daukantaité, & Westling, Citation2018). Alongside experiences of individuals admitted to BA responding well to trust and responsibility were experiences of a change in the workplace related to a transmission of more positive attitudes towards all patients. This is in line with Mårtensson, Jacobsson, and Engström (Citation2014) who concluded that favorable attitudes among psychiatric nursing staff may be developed and transmitted in the workplace subculture.

Introducing and maintaining predictability of what was involved during BA was also perceived to reduce stress and created a sense of safety for clinicians. When the planned nature and amount of staff contact was clear to individuals, the perceived need to escalate in order to get needs met diminished. Similarly, when clinicians knew they had decision-making autonomy within the context of BA, they reported feeling released from the need to micro manage potential self-harm risks. This resulted in experiences of providing greater freedom for individuals during BA, with the added benefit of breaking down unhelpful hierarchies within service delivery, giving both clinicians and individuals a new chance to experience themselves and each other more effectively. A side effect of BA described by the participants was an increased independence of the ward staff due to the decreased involvement of physicians. This has never been addressed in general healthcare since extreme self-harm and risk for suicide has always been considered a matter for senior physicians.

The persons on BA in focus in this study had a history of highly restrictive safety precautions, compulsory regimes, and restraints. As expected, participants talked about numerous challenges and recognizable frustration and despair in providing psychiatric care to these individuals (Holth et al., Citation2018). However, using BA, frequent re-admissions were not seen as negative setbacks. Instead, participants described how former frustration had transformed into the joy of being able to offer individuals help while admitted to BA. This is in line with the manual for BA emphasizing a welcoming and enthusiastic approach towards the individual seeking BA for taking initiative to control their symptoms (Liljedahl, Helleman, Daukantaitė, et al., Citation2017). As a result, relationships between clinicians and individuals improved, with clinicians being able to glimpse the humanity of the individual rather than the relentlessness of their severe and acute needs. Participants experienced that BA allowed them to “meet the person behind the patient” and as such putting person-centered psychiatric nursing into practice (Barker, Citation2009; Welch, Citation2005). Outpatient care participants perceived this new way of working as a useful complement to ongoing Dialectical Behavior Therapy (DBT), similarly focusing on developing life skills within a structured environment (Chapman, Citation2006). Interestingly, the inclusion of outpatient care participants in this study revealed their experiences of using BA contracts as a valuable crisis-management tool in their job, not necessarily related to the actual use of BA, but rather to the sense of security created by knowing BA is accessible.

Providing BA for individuals with extreme self-harm in the present study was a predominantly positive experience, although also a burden to introduce a new method with a completely different approach from current psychiatric nursing standard. This indicates that moving from a clinical study setting to usual care while maintaining key aspects of BA such as predictability and clinical approach would require investments in capacity-building and planning (Schoenwald & Hoagwood, Citation2001). Importantly, stepwise testing and encouraging autonomy within the safety net of a BA contract was experienced as a movement towards prevention in line with needs of self-harming individuals and general principles of ideal care for this population (NICE, Citation2011; Swedish Council of Health Technology Assessment, Citation2015).

Discussion of the method

All individuals who potentially had experiences within the aim of the study were invited to participate. Those who volunteered to participate, likely the most enthusiastic, worked in different parts of the Skåne region, with different healthcare professionals within inpatient and outpatient care. Capturing experiences of BA from the viewpoints of both types of care increased the likelihood of a complete analysis centered around the individuals receiving BA. Covering a variation of viewpoints was essential to establish credibility (Graneheim, Lindgren & Lundman, Citation2017).

The analytical process was peer reviewed by two researchers independently, discussing interpretation of results until consensus was achieved, while reducing risk that subjective perspectives influenced the results (Graneheim, Lindgren & Lundman, Citation2017). Another strength is that the persons performing interviews (RL) and analysis (RL and KL) were not directly linked to the participating clinicians or employed at the clinic. Consequently, there was independence between the researchers collecting and analyzing data and the participants.

The study focus was repeatedly communicated from the first contact with potential participants, as well as throughout the interviews. To maintain study focus, questions were phrased towards caring for the most severely ill individuals. However, it should be noted that some experiences shared were more generally phrased, not necessarily related specifically to the study focus. Also, experiences of BA with the most severely ill individuals may not always have been easy to separate from experiences related to other individuals admitted to BA.

With respect to generalizability, the context of Swedish mental health care is a limitation, although the challenges with negative attitudes towards self-harming persons are recognized from other settings abroad (Holth et al., Citation2018; Huband & Tantam, Citation2000).

To achieve credibility and overall trustworthiness the voices of the participants were aimed to be heard throughout analysis. Careful interpretation of interview data was supported by examples of representative citations. Themes and sub-themes were crafted to comprise the latent meaning, using participants’ spoken words and phrases where appropriate. A figure was used to illustrate how themes were related as a result of interpretation. The translation of all quotes from Swedish to English was reviewed by a person fluent in both Swedish and English. To ensure comprehensive reporting the study followed the QOREQ checklist (Tong, Sainsbury & Craig, Citation2007).

Conclusions

BA was perceived to change psychiatric care providers’ roles in a beneficial direction and facilitate person-centered care. Providers reported great enthusiasm among themselves and from their project leader, which was perceived as good in the short term but not reliable for long-term implementation. Profound structural changes were reportedly needed to secure implementation and dissemination of BA as a new method of service delivery.

The effect of predictability and the welcoming BA approach that all BA ward staff receive training upon (Liljedahl, Helleman, Daukantaitė, et al., Citation2017) was perceived to benefit staff and individuals admitted to BA alike. This suggests that BA is a promising concept for further research on effects on quality of life and healthcare resource use among self-harming and suicidal persons with the most extensive psychiatric inpatient care.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank all the participating staff for their contribution and Reid Lantto for reviewing translation of quotes from Swedish to English.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

References

- American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). Washington, DC: Author.

- Barker, P. (2009). The tidal model: Developing a person-centered approach to psychiatric and mental health nursing. Perspectives in Psychiatric Care, 37(3), 79–87. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-6163.2001.tb00631.x

- Chapman, A. L. (2006). Dialectical behavior therapy: Current indications and unique elements. Psychiatry, 3(9), 62–68.

- Dahlgren, L., Emmelin, M., & Winkvist, A. (2007). Qualitative methodology for international public health. Umeå: Epidemiology and Public Health Sciences, Umeå University. ISBN 978-91-7264-326-0

- Graneheim, U. H., & Lundman, B. (2004). Qualitative content analysis in nursing research: Concepts, procedures and measures to achieve trustworthiness. Nurse Education Today, 24(2), 105–112. doi: 10.1016/j.nedt.2003.10.001

- Graneheim, U., Lindgren, B., & Lundman, B. (2017). Methodological challenges in qualitative content analysis: A discussion paper. Nurse Education Today, 56, 29–34. doi: 10.1016/j.nedt.2017.06.002

- Helleman, M., Goossens, P. J., Kaasenbrood, A., & van Achterberg, T. (2014a). Evidence base and components of brief admission as an intervention for patients with borderline personality disorder: A review of the literature. Perspectives in Psychiatric Care, 50(1), 65–75. doi: 10.1111/ppc.12023

- Helleman, M., Goossens, P. J. J., Kaasenbrood, A., & van Achterberg, T. (2014b). Experiences of patients with Borderline Personality Disorder with the brief admission intervention: A phenomenological study. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing, 23(5), 442–450. doi: 10.1111/inm.12074

- Helleman, M., Lundh, L. G., Liljedahl, S. I., Daukantaité, D., & Westling, S. (2018). Individuals' experiences with brief admission during the implementation of the brief admission Skåne RCT, a qualitative study. Nordic Journal of Psychiatry, 72(5), 380–386. doi: 10.1080/08039488.2018.1467966

- Holth, F., Walby, F., Røstbakken, T., Lunde, I., Ringen, P. A., Ramleth, R. K., … Kvarstein, E. H. (2018). Extreme challenges: Psychiatric inpatients with severe self-harming behavior in Norway: A national screening investigation. Nordic Journal of Psychiatry, 23, 1–29. doi: 10.1080/08039488.2018.1511751

- Huband, N., & Tantam, D. (2000). Attitudes to self-injury within a group of mental health staff. British Journal of Medical Psychology, 73(4), 495–504. doi: 10.1348/000711200160688

- ICT Services and System Development and Division of Epidemiology and Global Health. (2013). OpenCode 4.03. Umeå: University of Umeå.

- Karman, P., Kool, N., Poslawsky, I. E., & van Meijel, B. (2015). Nurses' attitudes towards self-harm: A literature review. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing, 22(1), 65–75. Epub 2014 Dec 9. doi: 10.1111/jpm.12171

- Kristiansen, L., Hellzén, O., & Asplund, K. (2010). Left alone – Swedish nurses’ and mental health workers’ experiences of being care providers in a social psychiatric dwelling context in the post-health-care-restructuring era. A focus-group interview study. Scandinavian Journal of Caring Sciences, 24(3), 427–435. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-6712.2009.00732.x

- Lieb, K., Zanarini, M. C., Schmahl, C., Linehan, M. M., & Bohus, M. (2004). Borderline personality disorder. Lancet, 364(9432), 453–461. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)16770-6

- Liljedahl, S. I., Helleman, M., Daukantaitė, D., & Westling, S. (2017). Brief admission: Manual for training and implementation developed from the Brief Admission Skåne Randomized Controlled Trial (BASRCT). Lund, Sweden: Media-Tryck, Lund University.

- Liljedahl, S. I., Helleman, M., Daukantaité, D., Westrin, Å., & Westling, S. (2017). A standardized crisis management model for self-harming and suicidal individuals with three or more diagnostic criteria of borderline personality disorder: The Brief Admission Skåne Randomized Controlled Trial Protocol (BASRCT). BMC Psychiatry, 17(1), 220.doi: 10.1186/s12888-017-1371-6

- Molin, J., Graneheim, U. H., & Lindgren, B.-M. (2016). Quality of interactions influences everyday life in psychiatric inpatient care-patients’ perspectives. International Journal of Qualitative Studies on Health and Well-Being, 11, 1–11. doi: 10.3402/qhw.v11.29897

- Moljord, I. E. O., Lara-Cabrera, M. L., Salvesen, Ø., Rise, M. B., Bjørgen, D., Antonsen, D. Ø., … Eriksen, L. (2017). Twelve months effect of self-referral to inpatient treatment on patient activation, recovery, symptoms and functioning: A randomized controlled study. Patient Education and Counseling, 100(6), 1144–1152. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2017.01.008

- Mårtensson, G., Jacobsson, J. W., & Engström, M. (2014). Mental health nursing staff's attitudes towards mental illness: An analysis of related factors. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing, 21(9), 782–788.

- NICE. (2011). Self-harm in over 8s: Long-term management. Clinical Guidance [CG133]: Longer-term treatment and management of self-harm. November 2011. Retrieved from https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/CG133/chapter/1-Guidance#longer-term-treatment-and-management-of

- O'Connor, S., & Glover, L. (2017). Hospital staff experiences of their relationships with adults who self-harm: A meta-synthesis. Psychology and Psychotherapy: Theory, Research and Practice, 90(3), 480–501. Epub 2016 Dec 30. doi: 10.1111/papt.12113

- Saunders, K. E. A., Hawton, K., Fortune, S., & Farrell, S. (2012). Attitudes and knowledge of clinical staff regarding people who self-harm: A systematic review. Journal of Affective Disorders, 139(3), 205–216. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2011.08.024

- Schoenwald, S. K., & Hoagwood, K. (2001). Effectiveness, transportability, and dissemination of interventions: What matters when? Psychiatric Services (Washington, D.C.), 52(9), 1190–1197. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.52.9.1190

- Sigrunarson, V., Moljord, I. E., Steinsbekk, A., Eriksen, L., & Morken, G. (2017). A randomized controlled trial comparing self-referral to inpatient treatment and treatment as usual in patients with severe mental disorders. Nordic Journal of Psychiatry, 71(2), 120–125. doi: 10.1080/08039488.2016.1240231

- Strand, M., Gustafsson, S. A., Bulik, C. M., von, H., & Juhlin, Y. (2015). Patient-controlled hospital admission: A novel concept in the treatment of severe eating disorders. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 48(7), 842–844. doi: 10.1002/eat.22445

- Swedish Council of Health Technology Assessment (2015). Self-harm: Patients' experiences and perceptions of professional care and support. Summary and conclusions. SBU Alert Report No. 2015-04.

- Thomsen, C. T., Benros, M. E., Maltesen, T., Hastrup, L. H., Andersen, P. K., Giacco, D., & Nordentoft, M. (2018). Patient-controlled hospital admission for patients with severe mental disorders: A nationwide prospective multicentre study. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 137(4), 355–363. doi: 10.1111/acps.12868

- Tong, A., Sainsbury, P., & Craig, J. (2007). Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): A 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. International Journal for Quality in Health Care, 19(6), 349–357. doi: 10.1093/intqhc/mzm042

- Welch, M. (2005). Pivotal moments in the therapeutic relationship. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing, 14(3), 161–165. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-0979.2005.00376.x