Abstract

People with psychotic disorders experience to a great extent avoidable physical illnesses and early mortality. The aim of the study was to investigate the potential effects for this group of participating in a lifestyle intervention. A multi-component nurse-led lifestyle intervention using quasi-experimental design was performed. Changes in biomedical and clinical measurements, self-reported health, symptoms of illness and health behavior were investigated. Multilevel modeling was used to statistically test differences in changes over time. Statistically significant changes were found in physical activity, HbA1c and waist circumference. A lifestyle intervention for people with severe mental illness can be beneficial for increasing physical activity.

Introduction

There is now a greater awareness of and evidence that shows that people with psychotic disorders risk physical ill health and early mortality (Hjorthøj, Stürup, McGrath, & Nordentoft, Citation2017). Psychotic disorder, which is defined as a mental illness such as schizophrenia and other long-term psychotic conditions, is significantly associated with high a prevalence of obesity (Vancampfort, et al., Citation2015a), cardiovascular disease (CVD) (Correll et al., Citation2017), Type 2 diabetes (Stubbs, Vancampfort, De Hert, & Mitchell, Citation2015) and metabolic syndrome (Vancampfort, et al., Citation2015a). It is well known that these health problems are associated with modifiable lifestyle factors such as physical activity, diet, smoking and metabolic syndrome and have an effect on physical health (Vancampfort et al., Citation2017). Mental health nurses have a key role in improving physical health (Happell, Platania-Phung, & Scott, Citation2014) and in providing lifestyle interventions to reduce the high prevalence of preventable diseases (De Hert, et al., Citation2011a).

Background

CVDs and diabetes are the leading causes of death in the world (WHO, Citation2017). The increase in the prevalence of these diseases has generally been linked to four important risk factors: unhealthy diets, physical inactivity, tobacco use and the harmful use of alcohol. Metabolic risk factors contribute to four key metabolic changes that increase the risk for overweight and obesity, higher blood pressure and high blood levels of glucose and lipids (Piepoli et al., Citation2016; WHO, Citation2017).

Early mortality mainly due to heart disease and cancer has been highlighted among people with psychotic disorders in Sweden (Crump, Winkleby, Sundquist, & Sundquist, Citation2013). The contributing factors to poor health are emphasized as being complex and related to deficiencies in the health care system (Liu et al., Citation2017), such as a lack of integration in routine clinical services (Burton et al., Citation2015) and insufficient screening of metabolic syndrome (Mitchell, Delaffon, Vancampfort, Correll, & De Hert, Citation2012). Moreover, people with psychotic disorders are less frequently admitted to hospital for coronary heart disease and their survival rate after first hospital admissions for CVD is lower (Westman et al., Citation2018). A wide range of physical health problems among those with psychotic disorders, which might not always have been recognized by health care services, are frequently found (Eskelinen et al., Citation2017; Ewart, Bocking, Happell, Platania-Phung, & Stanton, Citation2016). Furthermore, antipsychotic medication has negative effects on physical health, such as metabolic syndrome (De Hert, et al., Citation2011b; Vancampfort, et al., Citation2015a).

People with psychotic disorders have been reported as facing similar barriers for behavioral change in terms of their lifestyle as those in the general population, such as lack of support but they also face barriers related to periods of mental illness (Yarborough, Stumbo, Yarborough, Young, & Green, Citation2016). Low mood levels, stress and lack of support have been described as obstacles for physical activity (Firth et al., Citation2016) and the negative experiences of the effects of medication, such as sedation have significantly affected all areas of life for the individuals (Morrison, Meehan, & Stomski, Citation2015). Financial restraints and social alienation can impact negatively on health (Ljungqvist et al., Citation2016) as well as loneliness (Trémeau, Antonius, Malaspina, Goff, & Javitt, Citation2016). However, it has been documented that people with psychotic disorders desire to receive support and health counseling from mental health services (Cocoman & Casey, Citation2018).

In health promotion, health is seen as being holistic, including physical, mental and social aspects that are all interlinked and interact with each other and need to be taken into account (Naidoo & Wills, Citation2016). Moreover, people with psychotic disorders have described the importance of being encountered as a whole human being and not just in terms of psychiatric symptoms when achieving and maintaining healthy living (Blomqvist, et al., Citation2018a). The Swedish National Guidelines state that it is the task of health care professionals to reinforce, and in particular, provide support for changing unhealthy lifestyle habits of adults in risk groups, such as people with schizophrenia (The National Board of Health and Welfare, Citation2018). Healthy lifestyle habits can prevent and delay the debut of CVD and type 2 diabetes (WHO, Citation2017) and it has thus been stated that greater attention should be paid to a physical health assessment and lifestyle-related factors promoting health also among people with psychotic disorders (Eskelinen et al., Citation2017; Stanley & Laugharne, Citation2014). For CVD prevention, individualized lifestyle interventions using a motivational interviewing (MI) approach including increased physical activity, smoking cessation and healthy dietary habits are recommended (Piepoli et al., Citation2016).

Studies focusing on the effects of lifestyle interventions for people with psychotic disorders have shown varied results. A systematic review revealed improved physical health after participation in lifestyle intervention (Happell, Davies, & Scott, Citation2012a), positive effects on weight loss and improvements in fasting glucose levels (Green et al., Citation2015) as well as in other risk factors for metabolic syndrome (Gabassa, Ezell, & Lewis-Fernández, Citation2010). A recently published meta-analysis has showed that lifestyle interventions have impacted the reduction and prevention of obesity and on decreasing cardio-metabolic risk factors except blood pressure and cholesterol levels (Bruins et al., Citation2014). Lifestyle interventions among people with psychotic disorders have, however, not always been able to demonstrate impact on the participants’ CVD risk (Speyer et al., Citation2016; Storch Jakobsen et al., Citation2017). A limited level of evidence has been found in a study on the effect of exercise interventions on cardiovascular fitness and weight among people with schizophrenia (Krogh, Speyer, Nã¸Rgaard, Moltke, & Nordentoft, Citation2014). Small advances, such as improved biomarkers, clinical measures and health-related quality of life, have been shown in a Swedish study (Wärdig, Foldemo, Hultsjö, Lindström, & Bachrach-Lindström, Citation2016).

The aim of the study was thus to evaluate the effects of participation in a multi-component individualized nurse-led lifestyle intervention on health behavior, biomedical and clinical measurements, self-reported symptoms of illness and salutogenic health in comparison with a control group.

Methods

Study design and participants

A longitudinal quasi-experimental study was carried out to compare the changes in health behaviors, biomedical and clinical measurements, self-reported salutogenic health (SHIS) and symptoms of illness (HSCL-25) at two years follow-up between the intervention group and a control group. All clinical measurements were carried out when participants had a planned appointment with the contact nurse or other health-care professional whom they had a regular contact with in the psychiatric outpatient services. All included psychiatric outpatient services were specialized to provide care and treatment for people with psychotic disorders, such as schizophrenia and other long-term psychotic conditions. Participants in the control group received care as usual.

People with psychotic disorders, who met the inclusion criteria (1) had an ongoing treatment at one of the included psychiatric outpatient services and (2) were between 18 and 65 years of age, were recruited between February 2013 and November 2014. Further inclusion criteria for analysis were (1) participants who had received at least one face-to-face counseling related to individual lifestyle factors and (2) have received some follow-up after baseline. Two people, who were 66 years old and who desired to participate and otherwise met the inclusion criteria, were also included. The exclusion criteria were current admission for inpatient care. The participants came from four psychiatric outpatient services in two different county health services. The intervention group was recruited from three of these psychiatric outpatient services and the control group from the fourth one. Data collection began in March 2013 and was completed in January 2017 when all the two-year follow-up appointments had been carried out.

There was a total of 23% missing data. Independent t-test was performed to test if there was systematic missingness in any of the variables between the participants with full data and the participants missing one or two measurement waves. Data were considered as missing at random because there were no statistically significant differences in any of the variables between the two groups.

The intervention

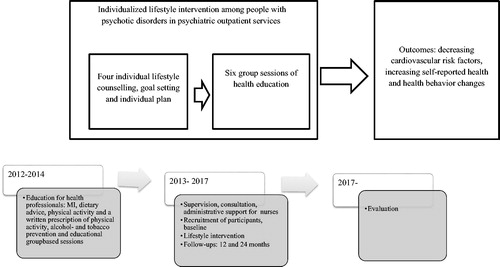

A complex nurse-led lifestyle intervention was designed with two interacting components and was tailored to suit the psychiatric outpatient services treating people with psychotic disorders. The intervention was aimed at promoting health and targeting particular lifestyle conditions, such as physical activity, healthy diet, smoking cessation and risk consumption of alcohol that the participants were free to choose between and focus on. The process of the lifestyle intervention is presented in .

The lifestyle intervention was delivered in partnership with psychiatric outpatient services and the municipal supported accommodations. All the health care professionals who were interested were invited to two-day educational seminars aimed at conveying knowledge and skills about health counseling and ensuring the fidelity of the intervention. The content of the education and training seminars was relevant for providing the intervention, one example of which was discourses focusing on MI, which is a person-centered counseling method to solve ambivalence and stimulate positive change by attracting and strengthening the person's own motivation to change (Miller & Rollnick, Citation2013). The education also included information about dietary advice, structured educational group sessions, tobacco and alcohol prevention, physical activity and a ‘Physical activity on prescription’. Furthermore, the mental health nurses delivering the intervention received a detailed manual describing the intervention and information material concerning, for example, lifestyle changes, physical activity and nursing documentation. Moreover, during the course of the intervention nurses were able to receive individual and group-based supervision and administrational support from the study nurse and from the research group. A website for the intervention was created for utilization by participants and health care professionals.

Components of the intervention

The lifestyle intervention included two components: face-to-face individual health counseling and educational group-based sessions.

Health counseling is defined as a dialog between a healthcare professional and a patient, with variations in terms of the individual’s age, health and risk levels (The National Board of Health and Welfare, Citation2018). The aim of the health counseling sessions were to increase the knowledge relating to lifestyle factors and health of the individuals in order to be able to promote health through a tailored support and to motivate behavioral changes. MI was used during the sessions that had a focus on lifestyle factors. Firstly, the participants were given the opportunity to take part in four face-to-face individual health counseling sessions related to lifestyle factors, with a contact nurse/study nurse. The participant was able to choose which lifestyle change he/she considered was most appropriate. The participants were offered coordinated individual plans, ‘Physical activity on prescription’, dietary advice, measuring of blood samples and clinical measures. The clinical measurements and the results from the blood samples were discussed with the participants as well as goal setting and future plans. When further support was needed from both the social services and the psychiatric services, the nurses were encouraged to establish a coordinated individual plan (The National Board of Health and Welfare, Citation2017). This was sometimes carried out together with staff from the municipalities and/or the next of kin. When necessary a physician and the primary health care services were contacted.

The four face-to-face health counseling sessions also included dietary advice and the participants could receive a written ´Physical activity on prescription` as a recommendation to increase physical activity. All authorized health care professionals in Sweden are empowered to write an individually tailored prescription based on the existing recommendations for physical activity currently used in all the county council health authorities in Sweden. The recommendation for physical activity is for a total of at least 150 minutes a week and intensity should at least be at the moderate level (Public Health Agency of Sweden, Citation2013). The dietary advice was based on the guidelines of the Swedish National Food Agency and included: (a) eating plenty of vegetables, fruit and berries, regular intake of fish, use of liquid vegetable oils and wholegrain, (b) choosing food with the Keyhole-label to reduce the intake of sugar and salt, increase whole grains and fiber, and to eat healthier or less fat, (c) using the plate model, which is an educational way of showing how the food can be distributed on the plate to increase the amount of vegetables and have a good balance in the meal and food circle when constructing the daily meal. The food circle consists of seven food groups and serves to help to choose food that provides a good variety of nutrients and energy (Swedish National Food Agency).

Secondly, over and above the health counseling sessions, this lifestyle intervention included six nurse-led educational group-based sessions where counseling about physical activity and healthy diet was also repeated. These were offered with a health promotion empowerment approach based on mutual alliance, openness and participation aimed at supporting individual health (Jormfeldt, Rask, Brunt, Bengtsson, & Svedberg, Citation2012). The sessions could also be provided individually if necessary. The content of the educational group-based sessions was a modified version of Eli Lilly Sweden’s (Citation2005a, Citation2005b) course material “A healthier life”. The group sessions included a dialog concerning health and a healthy lifestyle, including healthy food and daily dietary routines as well as a dialog about leading an active everyday life, physical activity, and support for and how to start behavior change.

The participants received a work-sheet of course material and written information about healthy dieting and physical activity. The cookbook, Healthy Nordic Food (Adamsson & Reumark, Citation2010), was offered to support participants cooking at home. All the participants were offered a pedometer as a tool for self-monitoring the measurement of the number of steps taken each day. One of the members in the research team prepared the study material for these educational group-based sessions and two or three nurses co-led and supervised these sessions together with one of the staff members from the municipal supported accommodation services. The participants and the nurses were encouraged to involve significant others, such as next of kin or a contact person from the municipal supported accommodation in the intervention, in order to encourage the participant to implement and support the desired lifestyle change in his/her daily home environment.

Tobacco cessation (Holm Ivarsson, Citation2015) and alcohol prevention were offered in terms of the Swedish guidelines (The National Board of Health and Welfare, Citation2017) and were recommended to be delivered by using the MI approach (Miller & Rollnick, Citation2013). shows the part of the intervention provided for the participants and frequency of utilization.

Table 1. The part of the intervention provided for the participants and frequency of utilization (n = 54).

Outcome assessment and data collection

Data were gathered using several assessment instruments and the measurements were conducted at baseline and follow-ups one and two years after. Objective measures of health risk factors were carried out when participants had a planned appointment with the contact nurse or other healthcare professional whom they had a regular contact with at the psychiatric outpatient services. The following measurements were taken: height, weight, Body Mass Index (BMI), sagittal abdominal diameter, waist circumference and blood pressure. All clinical measurements and laboratory values were collected from electronic patient records. Glycated hemoglobin A1c (HbA1c) values were collected and analyzed and calculated by laboratory staff according to routine methods at hospital laboratories in each county healthcare service.

All subjective measures and demographic information questionnaires were distributed and collected by the participant´s contact nurse/study nurse when the participants had their regular appointment at the psychiatric outpatient services. The questionnaires were completed by the participants, either at home without assistance or with assistance from a contact person from a housing support team or by the contact nurse at the psychiatric outpatient services if needed. The subjective measurements included questions from the National Public Health Survey (The Public Health Agency of Sweden, Citation2009) concerning health behavior such as physical activity and consumption of healthy food. Salutogenic health (SHIS) and symptoms of illness (HSCL-25) were self-reported.

National Public Health Survey

The National Public Health Survey (Citation2009) is a national self-reported questionnaire coordinated by the Public Health Agency of Sweden. The responses concerning the data about age, gender, medical comorbidities, such as diabetes (with answer yes/no) as well as data about physical activity and consumption of healthy food were collected in the self-rated questionnaire.

Health behavior changes were measured using questions about physical activity: How much exercise and how much have you exerted yourself physically in your leisure time the last 12 months? The answers were rated on a four-point Likert scale where 1 was sedentary leisure time and 4 was regular exercise and training. Another question related to physical activity was: How much time do you spend on moderately exertive activities that make you warm during a normal week? The answers to this question were rated on a five-point Likert scale where 5 indicated five hours a week or more and 1 indicated not at all.

The questions about behavior change concerning healthy food were: How often do you eat greens and root vegetables? and How often do you eat fruit and berries? The answers were rated on a seven-point Likert scale where 1 indicted three times a day or more often and 7 indicated a few times a month or never.

Hopkins Symptom Checklist-25

The Hopkins Symptom Checklist (HSCL-25) is a self-report and widely used instrument for assessing general psychological distress that measures symptoms for illnesses such as anxiety and depression. HSCL-25 is rated on a four-point Likert scale, focusing symptoms during the last week. This questionnaire has shown to have satisfactory validity and reliability (Derogatis, Lipman, Rickels, Uhlenhuth, & Covi, Citation1974). A total score is calculated by averaging the scores, where a higher total score indicates a higher level of emotional distress (ibid.). A total mean score of ≥1.75 indicates severe psychiatric symptoms (Veijola et al., Citation2003). Cronbach’s α, in this study, was 0.96 at T1, 0.94 at T2 and 0.91 at T3.

Salutogenic Health Indicator Scale

Salutogenic Health Indicator Scale (SHIS) is a validated general health assessment and was applied to measure subjective health indicators from a salutogenic and holistic perspective (Bringsén, Andersson, & Ejlertsson, Citation2009). The 12 items in the questionnaire focus on self-rated state of health and cover mental, social, and physical well-being, activities and functioning, and personal situations (Linton, Dieppe, & Medina-Lara, Citation2016). SHIS is rated on a six-point Likert scale with higher scores indicating better salutogenic health with a range from 12 to 72 points. Cronbach’s α, in this study, was 0.93 at T1, 0.95 at T2 and 0.93 at T3.

Data collection

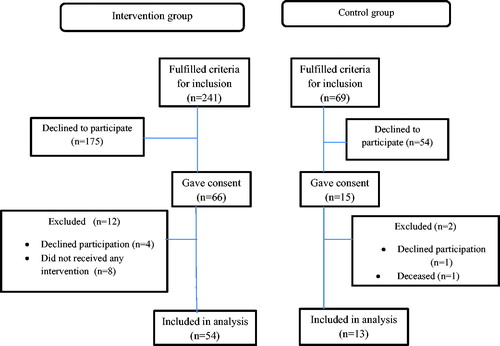

The mental health nurses at each included psychiatric outpatient service identified the potential participants who met the inclusion criteria for a larger lifestyle intervention research study. A study nurse gave both oral and written information to each participant. A total of 310 people met the criteria for inclusion, of which 229 declined to participate and 81 gave their consent. The final sample was reduced to a total of 54 participants in the intervention group and 13 participants in the comparison group. The flow of participants is presented in .

Data analysis

Descriptive analysis was performed using IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows version 24. The data are presented as means, standard deviations (SDs), ranges, frequencies and percentages. Multigroup two-level longitudinal Multilevel Models (MLM), using the Maximum Likelihood estimator in Mplus (Muthén & Muthén, 1998–Citation2012), were estimated to investigate potential differences in growth trajectories between participants in the intervention and the control group. All analyses were conducted using random slope models where the variance is allowed to vary across participants. In the within-person growth model, trajectories for the three measures of scores on the different outcome variables were specified on level 1. The slope of the outcome variables were specified on between-person level (level 2). The Wald chi-square test of parameter equalities was used to examine differences in the slopes, on level 2, between the intervention group and the control group. In all analyses, all model parameters were calculated using full information maximum likelihood, which uses available information from participants at all time points and handles missing data within the analysis model, under the assumption that data are missing at random. The alpha level (α) was set to 0.05 in the Wald tests and the Wald chi-square statistic was used to compute Cohen’s d effect size of the difference (Rosenthal & Dimatteo, Citation2001). We tested two competing models, one unadjusted and one where age and gender were included as co-variates on between-person level (level 2). To compare the model fit for the different models we used the Schwarz Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC). Lower values on this criterion indicate a better model fit.

Ethical considerations

The study was approved by the Regional Ethical Review Board in Lund (Dnr 2012/267) and was conducted in accordance with ethical standards (WMA Declaration of Helsinki, Citation2013). At study entry, the participants received oral and written information about the voluntary nature of participation and that they could withdraw at any time. They were also assured that withdrawal from the study would not affect their contact with the health services or treatment.

Results

Characteristics of the participants at baseline

Participants were aged between 23 and 66 years and the mean age in both groups was 46 years. The sample was predominantly male, 65% (n = 35) in the intervention group and 54% (n = 7) in the control group. In the intervention group, 70% (n = 38) of participants were living alone compared with 46% (n = 6) in the control group. The participants in the intervention group had an average of 20 years of contact with the psychiatric healthcare services (range 2–42) and those in the control group had an of average 18 years (range 3–44). The baseline characteristics of the participants in the intervention and control groups are presented in .

Table 2. The baseline characteristics of the participants in the intervention and control groups.

Self-reported and clinical measurements at baseline and two years follow-ups

Baseline and follow-up data including health behavior, blood samples, clinical measures and self-reported SHIS and HSCL-25 are shown in .

Table 3. Baseline and follow-up data.

Intervention effects

For all variables the results showed that the unadjusted model had best fit to data. For model fit indices see . Based on these results we decided to present the results from the unadjusted model. The MLM analysis showed that physical activity had a statistically significant increase in the intervention group but no statistically significant change in the control group. There was a, moderate (Cohen’s d = 0.54), statistically significant difference between the two groups in physical activity change.

Table 4. Results from the unadjusted multigroup 2-level multilevel analyses of the differences in effects between the intervention and control groups.

Moreover, there was a statistically significant increase in HbA1c in the intervention group but a statistically significant decrease in the control group. The differences in change between groups were large (Cohen’s d = 0.96) and statistically significant. There was also a moderate and statistically significant difference in change for waist circumference between the intervention and control groups. More specifically, the intervention group had a small, and not statistically significant increase while the control group had a small, and not statistically significant, decrease. There were no significant changes or differences in change between the intervention and control groups for any of the other outcomes (Cohen's d ranged from 0.02 to 0.35 indicating trivial to small effects for the differences in change between groups).

The result of the intervention effects is presented in .

Discussion

Discussion of results

The present study evaluated the outcomes of a nurse-led lifestyle intervention focusing on a number of health behaviors: physical activity and consumption of healthy food, self-reported salutogenic health and symptoms of illness, health risks factors related to CVD and Type 2 diabetes. The hypothesis was that an individual nurse-led, multicomponent lifestyle intervention could improve health behavior and subjective perceived health and reduce health risk factors for CVD and Type 2 diabetes.

The results showed a significant increase in physical activity in the intervention group that is encouraging for this population considering that persons with psychotic disorders have shown to have more sedentary lifestyle (Vancampfort et al., Citation2017) and have a high risk for metabolic syndrome (Vancampfort, et al., Citation2015a). Similarly, this promising result of increased physical activity is important because this has been found to reduce depressive symptoms and other symptoms of schizophrenia as well as increase quality of life (Rosenbaum, Tiedemann, Sherrington, Curtis, & Ward, Citation2014).

Mental health nurses have described physical activity as an integral part of care and appertaining to holistic care but that many complex hindrances simultaneously exist, such as funding, symptoms of mental illness, working culture and stigma (Happell, et al., Citation2012b). Mental health nurses in Sweden have reported that physical activity among the target group is frequently used. However, despite the nurses’ experiences of the positive effects for their patients, uncertainty still exists about the benefits of and evidence for physical activity interventions as constituting complementary treatment (Carlbo, Persic Claesson, & Åström, Citation2018). Nurses’ needs for education and training for the provision of lifestyle interventions have also been reported (Hennessy & Cocoman, Citation2018).

The results in the present study showed, however, that the lifestyle intervention was not effective in improving clinical outcomes such as HbA1c and waist circumference. The effect sizes for all significant changes showed medium effect for physical activity (0.54) but effect size for HbA1c is regarded as large (0.96). In spite of the mean value of HbA1c being under the cutoff for diabetes, both at baseline and at follow-up, there was a significant change in HbA1c between groups. People with schizophrenia are at risk of Type 2 diabetes (Suvisaari et al., Citation2016) and the need for a clinical implementation of screening and providing healthy lifestyle interventions is important (Stubbs et al., Citation2015). The other self-reported health aspects, objective and subjective measured health parameters, did not show any changes after participating in the individualized nurse-led lifestyle intervention. Unexpectedly, the intervention did not either generate an effect on BMI despite BMI-levels being shown to be high in this target group (Blomqvist, et al., Citation2018b). One explanation may be that there were differences between the intervention group and the control group at baseline both in terms of objective and subjective measurements. This also leads to a question whether the time period of two years could be adjudged to be too short to show effects for the variables in the present study, as no effects in terms of reduced cardiovascular risk factors had been previously shown in this population with the same follow-up period in a study by Storch Jakobsen et al. (Citation2017). Furthermore, it remains unclear whether the individualized nurse-led lifestyle intervention attained a sufficient level of behavior change among participants to achieve successful health outcomes and whether the intervention period was sufficiently long to generate satisfactory levels of behavior changes among participants.

The nurse-led lifestyle intervention was delivered using a MI approach aiming to generate and increase motivational process, which is a key part of the MI approach processes for behavior change (Miller & Rollnick, Citation2013). MI spirit and motivation have been seen to be the core mechanisms in MI and its possible efficacy (Copeland, McNamara, Kelson, & Simpson, Citation2015) but simultaneously nurses in primary healthcare have described MI approach as demanding to adapt and that it requires making efforts to adopt new working habits (Brobeck, Berg, Odencrants, & Hildingh, Citation2011). Training, feedback and supervision are identified as necessary for ensuring fidelity in clinical practice (Östlund, Kristofferzon, Häggström, & Wadensten, Citation2015).

The self-determination theory states that people increase their internal motivation when their basic psychological needs are taken into account, i.e. in terms of increased autonomy, sense of competence and social relatedness (Deci & Ryan, Citation2008). Autonomous motivation, supporting personal goals and motivation, have in particular been shown to be significant among people with psychotic disorders for adopting and maintaining health behavior (Vancampfort, et al., Citation2015b) as well as being shown to correlate with participation and engagement in an exercise intervention (Firth et al., Citation2016). Moreover non-stigmatizing attitudes, supportive relationships with interpersonal continuity, positive emotional climate and social interaction have been identified as important components for being able to experience mental health care as helpful (Denhov & Topor, Citation2011).

Methodological considerations

A supportive leadership is important when trying to change the attitudes of health care professionals’ towards a more health promoting approach (Johansson, Weinehall, & Emmelin, Citation2010). Contextual factors such as organizational climate and implementation strategy are known to have an impact on intervention outcomes (Carlfjord, Andersson, Nilsen, Bendtsen, & Lindberg, Citation2010a). Internal contextual factors such as the attitudes of individuals and the intended value of the intervention as well as external factors may have considerable effects on implementation and intervention outcomes (Damschroder et al., Citation2009). Organizational changes carried out at the same time can thus make implementation of projects less successful (Carlfjord, Lindberg, Bendtsen, Nilsen, and Andersson, Citation2010b). Unfortunately, major organizational and work-related changes took place in the psychiatric outpatient services during the intervention, which may have had an impact on the nurses’ attitudes towards the implementation and a negative effect on intervention. The education was provided before the intervention was started but no tools were used to measure motivational preparedness for work behavior change to ensure the fidelity of the intervention. A heavy work load and staff turnover was observed from the beginning of the research project.

The study design had broad inclusion criteria, which may have had an impact on the results. The present study is part of a larger research project that included several questionnaires and which may have been experienced as time-consuming by participants and mental health nurses thus generating missing data. When interpreting the results the limitations of quasi-experimental design should be taken account such as the susceptible to bias like causal interference as well as the lack of random assignment and not fully equivalent groups might have affected the outcome of the study and the internal validity. Moreover the small sample reduces the generalizability of the results of the study.

Due to the broad nature of the inclusion criteria many services users were given an opportunity to participate in the lifestyle intervention. This nurse-led intervention had a multicomponent design and encouraged the participants to freely choose their primary focus in the intervention to achieve their goals as well as the frequency of their participation. The number of drop-outs in the follow-up of the research project was low, in spite of the longitudinal study design. Furthermore, the intervention has increased knowledge about health risks for the participants among health professionals working in these psychiatric outpatient services and municipal housing support teams and they have been trained to provide health-promoting interventions in everyday practice.

Conclusion and future research

The result is important and suggests that nurse-led lifestyle interventions can change health behavior and increase physical activity among people with psychotic disorders in psychiatric outpatient services. Furthermore, research into increased physical activity after participation in individualized, nurse-led lifestyle interventions and factors affecting waist circumference and HbA1c is needed.

Implications for nursing practice

The high prevalence of health risk among people with psychotic disorders generates the need for mental health nurses to provide a more health-promotive mental health care. Implementation of individually tailored lifestyle interventions to increase physical activity and integrate physical activity in individual coordinated care plans is important and can contribute to improved physical health for people with psychotic disorders.

Author contribution

The manuscript was drafted by the first author and critical revisions for significant intellectual content were made by all the authors in its completion.

Authorship declaration

All of the authors have contributed to this study in terms of its design, participated in the analysis and interpretation of the results, and are responsible for the content and writing of the paper. The first author was responsible for the data collection.

Authorship statement

All authors meet the criteria according to the latest guidelines of the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors and are in agreement with this manuscript.

Declaration of interest

The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of the paper.

Acknowledgments

The authors are most grateful to the participants for taking part in the study. We would also like to express our appreciation to Professor Gunnar Johansson for his contribution to the design phase of the research project.

Disclosure statement

The authors confirm that this article content has no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Adamsson, V., & Reumark, A. (2010). Hälsosam nordisk mat. (Healthy Nordic Food). Checkprint, Sweden.

- Blomqvist, M., Sandgren, A., Carlsson, I. -M., & Jormfeldt, H. (2018a). Enabling healthy living: Experiences of people with severe mental illness in psychiatric outpatient services. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing, 27(1), 236–246. doi:10.1111/inm.12313

- Blomqvist, M., Ivarsson, A., Carlsson, I.-M., Sandgren, A., & Jormfeldt, H. (2018b). Health risks among people with severe mental illness in psychiatric outpatient settings. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 39(7), 585–591. doi:10.1080/01612840.2017.1422200

- Bringsén, Å., Andersson, I., & Ejlertsson, G. (2009). Development and quality analysis of the Salutogenic Health Indicator Scale (SHIS). Scandinavian Journal of Public Health, 37(1), 13–19. doi:10.1177/1403494808098919

- Brobeck, E., Berg, H., Odencrants, S., & Hildingh, C. (2011). Primary healthcare nurses´ experiences with motivational interviewing in health promotion practice. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 20 (23–24), 3322–3330. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2702.2011.03874.x

- Bruins, J., Jo, T., Bruggeman, R., Slooff, C., Corpeleijn, E., & Pijnenborg, M. (2014). The effects of lifestyle interventions on (long-term) weight management, cardiometabolic risk and depressive symptoms in people with psychotic disorders: A meta-analysis. Plos One, 9(12), e112276. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0112276

- Burton, A., Osborn, D., Atkins, L., Michie, S., Gray, B., Stevenson, F., … Walters, K. (2015). Lowering cardiovascular disease risk for people with severe mental illnesses in primary care: A focus group study. PLoS One, 28, 1–16. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0136603

- Carlbo, A., Persic Claesson, H., & Åström, S. (2018). Nurses' experiences in using physical activity as complementary treatment in patients with schizophrenia. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 39(7), 600–607. doi:10.1080/01612840.2018.1429508

- Carlfjord, S., Andersson, A., Nilsen, P., Bendtsen, P., & Lindberg, M. (2010a). The importance of organizational climate and implementation strategy at the introduction of a new working tool in primary health care. Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice, 16, 1326–1332.

- Carlfjord, S., Lindberg, M., Bendtsen, P., Nilsen, P., & Andersson, A. (2010b). Key factors influencing adoption of an innovation in primary health care: A qualitative study based on implementation theory. BMC Family Practice, 11(1), 60. doi:10.1186/1471-2296-11-60

- Cocoman, A. M., & Casey, M. (2018). The physical health of individuals receiving antipsychotic medication: A qualitative inquiry on experiences and needs. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 39(3), 282–289. doi:10.1080/01612840.2017.1386744

- Copeland, L., McNamara, R., Kelson, M., & Simpson, S. (2015). Mechanisms of change within motivational interviewing in relation to health behaviors outcomes: A systematic review. Patient Education and Counseling, 98(4), 401–411. doi:10.1016/j.pec.2014.11.022

- Correll, C. U., Solmi, M., Veronese, N., Bortolato, B., Rosson, S., Santonastaso, P., … Stubbs, B. (2017). Prevalence, incidence and mortality from cardiovascular disease in patients with pooled and specific severe mental illness: A large-scale meta-analysis of 3,211,768 patients and 113,383,368 controls. World Psychiatry, 16(2), 163–180.

- Crump, C., Winkleby, M. A., Sundquist, K., & Sundquist, J. (2013). Comorbidities and mortality in persons with schizophrenia: A Swedish national cohort study. American Journal of Psychiatry, 170(3), 324–333. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.2012.12050599

- Damschroder, L. J., Aron, D. C., Rosalin, E. K., Kirsh, S. R., Alexander, J. A., & Lowery, J. C. (2009). Fostering implementation for health services research findings into practice: A consolidated framework for advancing implementation science. Implementation Science, 4(1), 50. doi:10.1186/1748-5908-4-50

- De Hert, M., Cohen, D., Bobes, J., Cetkovich-Bakmas, M., Leucht, S., Ndetei, D. M., … Correll, C. U. (2011a). Physical illness in patients with severe mental disorders. II. Barriers to care, monitoring and treatment guidelines, plus recommendations at the system and individual level. World Psychiatry, 10(2), 138–151. doi:10.1002/j.2051-5545.2011.tb00036.x

- De Hert, M., Correll, C. U., Bobes, J., Cetkovich-Bakmas, M., Cohen, D. A. N., Asai, I., … Leucht, S. (2011b). Physical illness in patients with severe mental disorders. I. Prevalence, impact of medications and disparities in health care. World Psychiatry, 10(1), 52–77. doi:10.1002/j.2051-5545.2011.tb00014.x

- Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R. M. (2008). Facilitating optimal motivation and psychological well-being across lifès domains. Canadian Psychology, 49(1), 14–23.

- Denhov, A., & Topor, A. (2011). The components of helping relationships with professionals in psychiatry: Users' perspective. The International Journal of Social Psychiatry, 58(4), 417–424. doi:10.1177/0020764011406811

- Derogatis, L., Lipman, R., Rickels, K., Uhlenhuth, E. H., & Covi, L. (1974). The Hopkins Symptom Checklist (HSCL): A self-report symptom inventory. Behavioral Science, 19, (1), 1–15. doi:10.1002/bs.3830190102

- Eli Lilly Sweden (2005a). Ett sundare liv: Kunskap om livsstil. Ett aktivt liv: Patienthäfte. (A healthier life: Knowledge of lifestyle. An active life: Patient booklet. Solna: Eli Lilly Sweden.

- Eli Lilly Sweden (2005b). Ett sundare liv: Kunskap om livsstil. Hälsa och välbefinnande: Patienthäfte. (A healthier life: Knowledge of lifestyle. Health and well-being: Patient booklet). Solna: Eli Lilly Sweden.

- Eskelinen, S., Sailas, E., Joutsenniemi, K., Holi, M., Koskela, T. H., & Suvisaari, J. (2017). Multiple physical healthcare needs among outpatients with schizophrenia: Findings from a health examination study. Nordic Journal of Psychiatry, 71(6), 448–454. doi:10.1080/08039488.2017.1319497

- Ewart, S. B., Bocking, J., Happell, B., Platania-Phung, C., & Stanton, R. (2016). Mental health consumer experiences and strategies when seeking physical health care: A focus group study. Global Qualitative Nursing Research, 3, 1–10. doi:10.1177/2333393616631679

- Firth, J., Rosenbaum, S., Stubbs, B., Gorczynski, P., Yung, A. R., & Vancampfort, D. (2016). Motivating factors and barriers towards exercise in severe mental illness: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychological Medicine, 46(14), 2869–2881. doi:10.1017/S0033291716001732

- Gabassa, L. J., Ezell, J. M., & Lewis-Fernández, R. (2010). Lifestyle intervention for adults with serious mental illness: A systematic literature review. Psychiatric Services, 61(8), 774–782. doi:10.1176/appi.ps.61.8.774

- Green, C. A., Yarborough, B. J. H., Leo, M. C., Yarborough, M. T., Stumbo, S. P., Janoff, S. L., … Stevens, V. J. (2015). The STRIDE weight loss and lifestyle intervention for individuals taking antipsychotic medications: A randomized trial. American Journal of Psychiatry, 172(1), 71–81. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.2014.14020173

- Happell, B., Davies, C., & Scott, D. (2012a). Health behavior interventions to improve physical health in individuals diagnosed with a mental illness: A systematic review. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing, 21(3), 236–247. doi:10.1111/j.1447-0349.2012.00816.x

- Happell, B., Scott, D., Platania-Phung, C., & Nankivell, J. (2012b). Nurses` views on physical activity for people with serious mental illness. Mental Health and Physical Activity, 5(1), 4–12. doi:10.1016/j.mhpa.2012.02.005

- Happell, B., Platania-Phung, C., & Scott, D. (2014). Proposed nurse‐led initiatives in improving physical health of people with serious mental illness: A survey of nurses in mental health. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 23(7–8), 1018–1029. doi:10.1111/jocn.12371

- Hennessy, S., & Cocoman, A. M. (2018). What is the impact of targeted health education for mental health nurses in the provision of physical health care? An integrated literature review. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 39(8), 700–706. doi:10.1080/01612840.2018.1429509

- Hjorthøj, C., Stürup, A. E., McGrath, J. J., & Nordentoft, M. (2017). Years of potential life lost and life expectancy in schizophrenia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Psychiatry, 4(4), 295–301. doi:10.1016/S2215-0366(17)30078-0

- Holm Ivarsson, B. (2015). Consulting and tobacco weaning in psychiatry, care and care psychologists against tobak in cooperation with tower to tobak suspension cuts on tobacks dentistry against tobacco. 3rd Revised publication. TMG Tabergs ab: Taberg. Retrieved from https://www.psykologermottobak.org/psykiatri_bereondevard_socialtjanst

- Johansson, H., Weinehall, K., & Emmelin, M. (2010). ” If we only got a chance”. Barriers to and possibilities for a more health-promoting health service. Journal of Multidisciplinary Healthcare, 3, 1–9.

- Jormfeldt, H., Rask, M., Brunt, D., Bengtsson, A., & Svedberg, P., (2012). Experiences of a person-centred health education group intervention – A qualitative study among people with a persistent mental illness. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 33(4), 209–216. doi:10.3109/01612840.2011.653041

- Krogh, J., Speyer, H., Nã¸Rgaard, H. C. B., Moltke, A., & Nordentoft, M. (2014). Can exercise increase fitness and reduce weight in patients with schizophrenia and depression? Frontiers in Psychiatry, 5, 1–6. doi:10.3389/fpsyt.2014.00089

- Linton, M. -J., Dieppe, P., & Medina-Lara, A. (2016). Review of 99 self-report measures for well-being in adults: Exploring dimensions of well-being and developments over time. BMJ Open, 6, (7), e010641. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2015-010641

- Liu, N. H., Daumit, G. L., Dua, T., Aquila, R., Charlson, F., Cuijpers, P., … Saxena, S. (2017). Exess mortality in persons with severe mental disorders: A multilevel intervention framework and priorities for clinical practice, policy and research agendas. World Psychiatry, 16(1), 30–40. doi:10.1002/wps.20384

- Ljungqvist, I., Topor, A., Forssell, H., Svensson, I., & Davidson, L. (2016). Money and mental illness: A study of the relationship between poverty and serious psychological problems. Community Mental Health Journal, 52(7), 842–850. doi:10.1007/s10597-015-9950-9

- Miller, W. F., & Rollnick, S. (2013). Motivational interviewing. Helping people change (3rd ed.). New York, NY: Guildord Press New York, NY.

- Mitchell, A. J., Delaffon, V., Vancampfort, D., Correll, C. U., & De Hert, M. (2012). Guideline concordant monitoring of metabolic risk in people treated with antipsychotic medication: Systematic review and meta-analysis of screening practices. Psychological Medicine, 42(1), 125–147. doi:10.1017/S003329171100105X

- Morrison, P., Meehan, T., & Stomski, N. J. (2015). Living with antipsychotic medication side-effects: The experience of Australian mental health consumers. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing, 24(3), 253–261. doi:10.1111/inm.12110

- Muthén, L. K., & Muthén, B. O. (1998–2012). Mplus user’s guide: Statistical analysis with latent variables (7th ed.). Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén.

- Naidoo, J., & Wills, J. (2016). Foundation for health promotion (4th ed., pp. 4–5). Amsterdam: Elsevier Health Sciences.

- National Food Agency, Sweden. Retrieved from https://www.livsmedelsverket.se/

- Östlund, A.-S., Kristofferzon, M.-L., Häggström, E., & Wadensten, B. (2015). Primary care nurses` performance in motivational interviewing: A qualitative descriptive study. BMC Family Practice, 16(1), 89. doi:10.1186/s12875-015-0304-z

- Piepoli, M. F., Hoes, A. W., Agewall, S., Albus, C., Brotons, C., Catapano, A. L., … Verschuren, W. M. M. (2016). European guidelines on cardiovascular disease prevention in clinical practice. European Heart Journal, 37(29), 2315–2381. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehw106

- Public Health Agency of Sweden (Folkhalsomyndigheten). (2009) Nationella folkhälsoenkäten (National public health survey, 2009) – Hälsa på lika villkor (Health on equal terms). Retrieved from https://www.folkhalsomyndighetense/the-public-health-agency-of-sweden/

- Public Health Agency of Sweden (Folkhalsomyndigheten). (2013) Physical activity. Retrieved from https://www.folkhalsomyndigheten.se/livsvillkor-levnadsvanor/fysisk-aktivitet-och-matvanor/fysisk-aktivitet/

- Rosenbaum, S., Tiedemann, A., Sherrington, C., Curtis, J., & Ward, P. B. (2014). Physical activity interventions for people with mental illness: A systematic review and meta-analysis. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 75(09), 964–974. doi:10.4088/JCP.13r08765

- Rosenthal, R., & DiMatteo, M. R. (2001). Meta-analysis: Recent developments in quantitative methods for literature reviews. Annual Review of Psychology, 52(1), 59–82. doi:10.1146/annurev.psych.52.1.59

- Speyer, H., Christian Brix Nørgaard, H., Birk, M., Karlsen, M., Storch Jakobsen, A., Pedersen, K., … Nordentoft, M. (2016). The CHANGE trial: No superiority of lifestyle coaching plus care coordination plus treatment as usual compared to treatment as usual alone in reducing risk of cardiovascular disease in adults with schizophrenia spectrum disorders and abdominal obesity. World Psychiatry, 15(2), 155–165. doi:10.1002/wps.20318

- Stanley, S., & Laugharne, J. (2014). The impact of lifestyle factors on the physical health of people with a mental illness: A brief review. International Journal of Behavioral Medicine, 21(2), 275–281. doi:10.1007/s12529-013-9298-x

- Storch Jakobsen, A., Speyer, H., Brix Nørgaard, H. K., Karlsen, M., Birk, M., Hjorthøj, C., … Nordentoft, M. (2017). Effect of lifestyle coaching verus care coordination versus treatment as usual in people with severe mental illness and overweight: Two-years follow-up of the randomized CHANGE trial. Plos One, 12(10), 1–13. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0185881

- Stubbs, B., Vancampfort, D., De Hert, M., & Mitchell, A. J. (2015). The prevalence and predictors of type two diabetes mellitus in people with schizophrenia: A systematic review and comparative meta‐analysis. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 132(2), 144–157. doi:10.1111/acps.12439

- Suvisaari, J., Keinänen, J., Eskelinen, S., & Mantere, O. (2016). Diabetes and schizophrenia. Current Diabetes Reports, 16(2), 16. DOI 10.1007/s11892-015-0704-4

- The National Board of Health and Welfare (2017). About patients` contact with health and care services and coordinated individual care plans. A national guide. (Om fast vårdkontakt och samordnad individuell plan. Nationell vägledning.) Retrieved from http://www.socialstyrelsen.se/publikationer2017/2017-10-25

- The National Board of Health and Welfare. (2018). National guidelines for prevention and treatment of unhealthy lifestyle habits. Support for managers. (Nationella riktlinjer för prevention och behandling vid ohälsosamma levnadsvanor. Stöd för styrning och ledning). Retrieved from https://www.socialstyrelsen.se/publikationer2018/2018-6-24

- Trémeau, F., Antonius, D., Malaspina, D., Goff, D. C., & Javitt, D. C. (2016). Loneliness in schizophrenia and its possible correlates. An exploratory study. Psychiatry Research, 246, 211–217. doi:10.1016/j.psychres.2016.09.043

- Vancampfort, D., Firth, J., Schuch, F. B., Rosenbaum, S., Mugisha, J., Hallgren, M., … Stubbs, B. (2017). Sedentary behavior and physical activity levels in people with schizophrenia, bipolar disorder and major depressive disorder: A global systematic review and meta‐analysis. World Psychiatry, 16(3), 308–315. doi:10.1002/wps.20458

- Vancampfort, D., Stubbs, B., Mitchell, A. J., De Hert, H., Wampers, M., Ward, P. B., … Correll, C. U. (2015a). Risk of metabolic syndrome and its components in people with schizophrenia and related psychotic disorders, bipolar disorder and major depressive disorder: A systematic review and meta-analysis. World Psychiatry, 14(3), 339–347. doi:10.1002/wps.20252

- Vancampfort, D., Stubbs, B., Kumar Venigalla, S., & Probst, M. (2015b). Adopting and maintaining physical activity behaviours in people with severe mental illness: The importance of autonomous motivation. Preventive Medicine, 81, 216–220. doi:10.1016/j.ypmed.2015.09.006

- Veijola, J., Jokelainen, J., Läksy, K., Kantojärvi, L., Kokkonen, P., Järvelin, M., & Joukamaa, M. (2003). The Hopkins symptom checklist-25 in screening DSM-III-R axis-I disorders. Nordic Journal of Psychiatry, 57(2), 119–123. doi:10.1080/08039480310000941

- Wärdig, R., Foldemo, A., Hultsjö, S., Lindström, T., & Bachrach-Lindström, M. (2016). An intervention with physical activity and lifestyle counseling improves health-related quality of life and shows small improvements in metabolic risks in persons with psychosis. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 37(1), 43–52.

- Westman, J., Eriksson, S. V., Gissler, M., Hällgren, J., Prieto, M. L., Bobo, W. V., … Ösby, U. (2018). Increased cardiovascular mortalty in people with schizophrenia: A 24-year national register study. Epidemiology and Psychiatric Sciences, 27, 519–527. doi:10.1017/S2045796017000166

- WHO (2017). Noncommunicable diseases. Retrieved from http://www.who.int/en/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/noncommunicable-diseases

- WMA Declaration of Helsinki (2013). Ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. Retrieved from https://www.wma.net/policies-post/wma-declaration-of-helsinki-ethical-principles-formedical-research-involving-human-subjects/

- Yarborough, B. J. H., Stumbo, S. P., Yarborough, M. T., Young, T. J., & Green, C. A. (2016). Improving lifestyle interventions for people with serious mental illnesses: Qualitative results from the STRIDE study. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal, 39(1), 33–41. doi:10.1037/prj0000151