Abstract

Women traumatized by sexual abuse as children or adults experience psychological disorders, such as post-traumatic stress, depression, anxiety, and social adjustment. The published research includes a broad array of studies on psychological interventions intended to ease their symptoms. This study systematically examined the specific effects of psychological interventions for women traumatized by sexual abuse and statistically evaluated interventions by calculating effect sizes in a meta-analysis. A literature search was conducted of electronic databases of journals, gray literature and Clinical Research Information Service. Medical Subject Heading terminology, text words, and logical operators were applied, and 2,029 articles published in English or Korean were retrieved. Inclusion criteria were full-text articles on randomized controlled trials in which: (1) the subjects were women 18 years or older who had been sexually assaulted or raped; (2) all types of exclusively psychological treatment were used; (3) comparisons were mediated or routinely managed without psychosomatic treatment; (4) interventions did not target patients with chronic mental illnesses or neurocognitive dysfunctions; and (5) the studies were not on animals, empirical research, cohorts, research protocols, or integrated literature reviews. Ten articles fully met the inclusion criteria. The main findings were: (1) interventions had long-term effects on post-traumatic stress reduction, (2) effects on depression were effective only 3 months post-intervention, and (3) there were no follow-up effects on anxiety reduction or social adjustment improvement. The types of therapeutic intervention, delivery mode, number and duration of sessions, and number of weeks varied.

Introduction

Sexual abuse is an increasingly serious issue throughout the world. The World Health Organization (Citation2014) estimated recent incidence rates as 44% in Africa, 29% in Europe, 62% in the United States, and 35% in the Western Pacific. A recent analysis of 65 studies indicated that the rate of sexual abuse of children in 22 countries was 19.7% among females and 7.9% among males (Pereda, Guilera, Forns, & Gómez-Benito, Citation2009). In the United States, a survey of 34,000 people aged 18 years or older found that 75.2% of the females and 24.8% of males reported sexual abuse (Pérez-Fuentes et al., Citation2013). In another study, about one-third of the people who experienced childhood sexual abuse experienced it more than once, and they were two to three times more likely to experience it than those with no experience (Arata, Citation2002). Thus, sexual abuse is a serious global issue and women are particularly vulnerable.

Many sexually traumatized women have experienced various physical, mental and social problems. They have been found more likely than those without the experience to exhibit physical pain and more likely to seek hospital treatment (Finestone et al., Citation2000). Fergusson, Boden, and Horwood (Citation2008) found that they were about 2.4 times more likely than women without sexual trauma to have mental health problems, and their psychosocial health problems were mostly caused by post-traumatic stress, depression, anxiety, drugs/alcohol abuse, social disorders and social fears (Chouliara, Karatzias, & Gullone, Citation2014; Felitti et al., Citation1998; Fergusson et al., Citation2008; Pérez-Fuentes et al., Citation2013). Therefore, interventions for sexually traumatized women should consider psychological factors.

Various interventions have been developed to help women traumatized by sexual abuse. They typically include the cognitive behavioral therapy developed by Resick and Schnicke (Citation1992), which aims to change their distorted beliefs and stabilize them in the aftermath of a trauma, and long-term efforts to integrate false fear structures into new structures (Foa & Kozak, Citation1986). Because these methods have been effective for reducing post-traumatic stress symptoms, depression and anxiety (Littleton, Grills, Kline, Schoemann, & Dodd, Citation2016; Miller, Cranston, Davis, Newman, & Resnick, Citation2015; Zoellner, Feeny, Fitzgibbons, & Foa, Citation1999), it is important to assess the ways these interventions are applied and their long-term effects.

To establish a foundation for helping sexually traumatized women, a thorough understanding of our knowledge to date as published in the scientific literature is needed. However, the research tends to include males and females (Taylor & Harvey, Citation2010) or is limited to reporting on selective experimental studies (Kim, Noh, & Kim, Citation2016). In Korea, there is a tendency to distort the nature of responsibility for this violence by viewing it through the lens of social stigma rather than considering the public’s and victims’ views on sexual crimes (Cho, Song, & Lee, Citation2016). As a result, the interventions are inadequate, and systematic literature reviews should be conducted that focus on women and sexual trauma. In particular, sexually abused women are difficult to contact and their trauma is difficult to mediate through randomized controlled trials (RCTs).

This study aimed to discover the direction in which interventions for sexually traumatized women seems to be headed based on the published research. It examined the effect sizes of the psychological intervention studies regarding the psychological variance among study subjects by conducting a systematic review and meta-analysis. The results provide objective evidence to support policy for developing interventions aimed at long-term results and for early interventions targeting sexually traumatized women. It focused on studies that specifically applied psychological interventions, identified their basic approaches and designs and compared the effects of their psychological interventions.

Methods

Study design

This meta-analysis of published RCTs aimed to assess the effects of psychological interventions for the mental health of sexually traumatized women.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

This study followed the systematic review steps proposed by Cochrane Collaboration (Higgins & Green, Citation2011). Key features were included or excluded in accord with PICO-SD (participants, intervention, comparisons, outcomes and study design) as follows: (1) participants were women 18 years or older who had been sexually assaulted or raped, (2) interventions included all types of psychological treatment, (3) comparisons were mediated or routinely managed without psychosomatic treatment, and (4) all study designs were RCTs. The three exclusion criteria for article selection were: (1) the intervention targeted patients with chronic mental illnesses or neurocognitive dysfunctions, females aged 18 years or younger or the subjects’ families; (2) pharmacotherapeutic intervention studies; and (3) animal experiments, empirical research, cohorts, research protocols, or integrated literature reviews or abstracts.

Data collection and sampling

The online literature search of 10 databases was conducted on November 5, 2018, covering an unrestricted publication period. PubMed, Exceptra Medica dataBASE (EMBASE), Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), PsycInfo and Cochrane Register Registered Control Trials (CENTRAL) were searched. For the Korean literature, Research Information Sharing Service System (RISS), National Digital Science Library (NDSL) and Korean Studies Information Service System (KISS) were used. The literature was manually searched using the Gray Literature Report and the Clinical Research Information Service (CRIS) for the American and Korean gray literature. Upon completion of the online search, the list of references was manually searched.

We used Medical Subject Heading (MeSH), EMTREE, CINAHL heading terminology, text words and logical operators. The Korean language retrieval was modified and simplified to conform to the PubMed search formula. A medical librarian who was an expert in meta-analyses confirmed the search formulae. Separate searches were conducted of each database using the search terms listed as queries in Appendix 1 (Supplementary data).

The retrieved articles were summarized using EndNote X8, a bibliographic management program. Duplicates were deleted from the dataset, and the titles and abstracts were evaluated to select only those articles that met the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Then, full-text content was confirmed and the final sample was determined. The steps used to select the articles were independently performed by two researchers, and, in cases of disagreement, the decision to retain or exclude an article was made according to the inclusion and exclusion criteria. The reasons for exclusion were recorded and the researchers agreed on all the decisions and their justifications.

Risk of bias

To confirm the external validity of the sample of articles, a methodological quality assessment was conducted using Cochrane’s risk of bias tool (Higgins & Green, Citation2011). The articles were ranked as ‘low’, ‘high’, or ‘unclear’ regarding selection bias, performance bias, detection bias, attrition bias and reporting bias. Two researchers independently assessed the research quality, and disagreements were discussed until agreement was reached.

Data analysis

The 10 articles ultimately extracted and analyzed are described in regarding lead author, year of publication, country, type of RCT, sample size, average age, variables and measurement.

Table 1. Sample characteristics (n = 10).

The effect sizes and the extent of heterogeneity of the intervention outcomes among the 10 articles in the sample were analyzed using Review Manager (RevMan) 5.3 and R statistical program. Effect sizes were confirmed by standardized mean differences (SMD) with 95% confidence intervals (CI). SMD standardizes the results as a single unit when the measurement tool is a continuous variable and different tools (Higgins & Green, Citation2011). Effect sizes of 0.3 or less were considered small, moderate was between 0.4 and 0.7, and large was 0.8 or larger (Cohen, Citation1988). The long-term psychological outcomes (post-traumatic stress, depression, anxiety and social adjustment disorders) were analyzed regarding 3-, 6- and 12-month follow-up periods.

The heterogeneity tests were performed on the Chi-squared null hypothesis of the intervention outcome variables. A p-value that was ≤.10 was used to indicate that heterogeneity was statistically significant (Higgins & Green, Citation2011), and I2 was interpreted as follows: 30–60% was moderate heterogeneity and more than 75% up to 100% was considerable heterogeneity (Higgins & Green, Citation2011). We used a random effects model that accounted for heterogeneity among the studies’ subjects and their intervention methods to reflect the extents of the studies’ volatility (Higgins & Green, Citation2011).

Publication bias was tested by funnel plot (Higgins & Green, Citation2011). The reliability of the test results was assessed by Failsafe-N (NFS) (Rosenthal, Citation1979). This step confirmed that the effect sizes of the studies reported by the articles were not significantly influenced by unpublished results. When the number of NFS to be added was large, the number of hidden papers was not large; therefore, the effect calculated by the meta-analysis was reliable, and the larger the NFS, the more reliable the calculated effect size.

Results

Search results

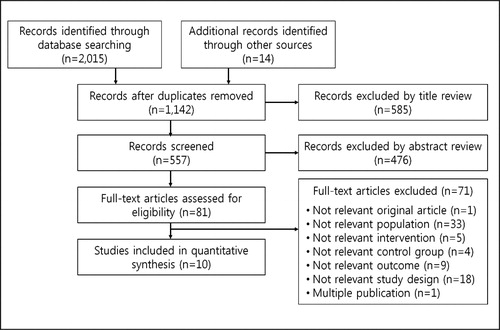

Using the sampling process described above and in Appendix 1 (Supplementary data), a sample of 1,929 articles was retrieved from PubMed (n = 488), EMBASE (n = 603), CINAHL (n = 187), PsycInfo (n = 512) and CENTRAL (n = 139). The 86 articles retrieved from the Korean databases were from RISS (n = 45), NDSL (n = 35) and KISS (n = 6). There were eight Gray Literature Report articles, five U. S. clinical trial registration databases, and one Korean clinical trial registration database. Of these 2,029 articles, 887 were duplicates and omitted, and, after review of the titles and abstracts, 1,061 were dropped because they were not centered on the core question. Of the remaining 81 articles, 71 were eliminated: 33 did not meet the inclusion criteria, 18 were not RCTs, nine provided insufficient results for meta-analysis, five were not psychological interventions, four did not have control groups, one was only an abstract, and one had duplicate studies. The sample selection process is illustrated in . Two researchers independently performed this entire process, and the final sample was determined after discussion and agreement on differences in opinion.

Sample characteristics

Design

Eight of the 10 studies employed face-to-face interventions (Chard, Citation2005; Foa, Rothbaum, Riggs, & Murdock, Citation1991; Jung & Steil, Citation2013; Krakow et al., Citation2001; Resick, Nishith, Weaver, Astin, & Feuer, Citation2002; Smith et al., Citation2012; Talbot et al., Citation2011; Zoellner et al., Citation1999). Two of them used telephone counseling for the control group (Chard, Citation2005; Resick et al., Citation2002). There was one online intervention trial (Littleton et al., Citation2016) and one video intervention (Miller et al., Citation2015). The gap between the baseline and follow-up assessments of the outcomes were 3 months (Foa et al., Citation1991; Jung & Steil, Citation2013; Littleton et al., Citation2016; Miller et al., Citation2015), 6 months (Krakow et al., Citation2001), 9 months (Resick et al., Citation2002; Smith et al., Citation2012; Talbot et al., Citation2011) and 12 months (Chard, Citation2005; Zoellner et al., Citation1999). In addition, outcomes were periodically assessed: 4 weeks (Jung & Steil, Citation2013), 2 months (Miller et al., Citation2015) and 10 weeks (Smith et al., Citation2012; Talbot et al., Citation2011).

Sample size

Sample sizes were relatively small and the mean sample size was 89. Only three studies had more than 100 cases: Krakow et al. (Citation2001): n = 168; Miller et al. (Citation2015): n = 164; and Resick et al. (Citation2002): n = 121.

Subjects

According to the inclusion criteria, all subjects were women older than 18 years. One study was on college students recruited by advertising on four campuses (Littleton et al., Citation2016). Two studies recruited subjects through newspaper advertisements (Foa et al., Citation1991; Zoellner et al., Citation1999). Two studies obtained subjects at a trauma center (Jung & Steil, Citation2013; Resick et al., Citation2002), and three studies obtained subjects at a community center (Chard, Citation2005; Krakow et al., Citation2001; Talbot et al., Citation2011). Just one study found its subjects at a hospital (Miller et al., Citation2015). Three studies comprised samples of women diagnosed with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) caused by childhood sexual abuse (Chard, Citation2005; Jung & Steil, Citation2013; Smith et al., Citation2012). Three studies’ subjects were diagnosed with PTSD caused by rape (Foa et al., Citation1991; Littleton et al., Citation2016; Resick et al., Citation2002), and two studies were conducted on sexual assault survivors (Krakow et al., Citation2001; Miller et al., Citation2015).

Interventions

The interventions are summarized in . The most frequent intervention was some type of cognitive therapy: cognitive behavioral therapy (Foa et al., Citation1991; Littleton et al., Citation2016; Zoellner et al., Citation1999), cognitive processing therapy (Chard, Citation2005; Resick et al., Citation2002) or cognitive restructuring and imagery modification (Jung & Steil, Citation2013). The Foa et al. (Citation1991), Resick et al. (Citation2002) and Zoellner et al. (Citation1999) interventions included prolonged exposure therapy. Foa et al. (Citation1991) and Zoellner et al. (Citation1999) included stress inoculation training. Miller et al. (Citation2015) incorporated a video intervention with psychoeducation, and Smith et al. (Citation2012) and Talbot et al. (Citation2011) combined coping strategies with interpersonal psychotherapy.

Table 2. Characteristics of the interventions of the sampled studies.

The majority of the formats was individual-level therapy (n = six studies). The other formats were group (Krakow et al., Citation2001; Resick et al., Citation2002) and combined individual/group therapy (Chard, Citation2005). One study did not report its format (Miller et al., Citation2015).

Four trials lasted 9 weeks (Foa et al., Citation1991; Krakow et al., Citation2001; Resick et al., Citation2002; Zoellner et al., Citation1999) and two trials lasted 14–17 weeks (Chard, Citation2005; Littleton et al., Citation2016). Two trials were 36 weeks long (Smith et al., Citation2012; Talbot et al., Citation2011), but two articles did not report the duration of the study’s intervention (Jung & Steil, Citation2013; Miller et al., Citation2015). The coordinators were therapists (Chard, Citation2005; Foa et al., Citation1991; Jung & Steil, Citation2013; Krakow et al., Citation2001; Littleton et al., Citation2016; Resick et al., Citation2002), nurses (Miller et al., Citation2015), clinicians (Smith et al., Citation2012; Talbot et al., Citation2011) and a psychologist (Zoellner et al., Citation1999).

Instruments

The outcomes being addressed were post-traumatic stress, depression, anxiety, self-esteem, shame, trauma-related guilt, hindsight bias, lack of justification, wrongdoing, social adjustment, interpersonal violence, social functioning and sleep quality. Nine studies assessed post-traumatic stress, used an intervention to treat it and subsequently checked the extent of change. Krakow et al. (Citation2001) and Resick et al. (Citation2002) used the Clinician Administered PTSD Scale (CAPS). Five studies used only the Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Symptom Scale (PSS) (Krakow et al., Citation2001; Littleton et al., Citation2016; Miller et al., Citation2015; Resick et al., Citation2002; Zoellner et al., Citation1999) and two studies used a modified PSS (Chard, Citation2005; Talbot et al., Citation2011). One study used the Posttraumatic Diagnostic Scale (PDS) (Jung & Steil, Citation2013) and one study used post-traumatic stress severity (Foa et al., Citation1991).

The eight studies that assessed depression used the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI), Center for Epidemiological Studies-Depression (CES-D) or Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (HRSD) to do so (Chard, Citation2005; Foa et al., Citation1991; Jung & Steil, Citation2013; Littleton et al., Citation2016; Resick et al., Citation2002; Smith et al., Citation2012; Talbot et al., Citation2011; Zoellner et al., Citation1999). Anxiety was assessed by four studies (Foa et al., Citation1991; Littleton et al., Citation2016; Miller et al., Citation2015; Zoellner et al., Citation1999) through the Four Dimensional Anxiety Scale (FDAS) or State Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI). Jung and Steil (Citation2013) used the Rosenberg Self-esteem Scale (RSES) to assess self-esteem.

The Nightmare Frequency Questionnaire (NFQ) and Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index (PSQI) were the instruments Krakow et al. (Citation2001) used to assess nightmare frequency and sleep quality. The frequency of nightmares was measured by frequency at night time and the number of nights in which nightmares occurred during 1 hour, 1 week, and 1 month. Social functioning was defined as social adjustment, close relationships and work relationships. Talbot et al. (Citation2011), Smith et al. (Citation2012) and Zoellner et al. (Citation1999) used the Inventory of Socially Supportive Behaviors (ISSB), Social Adjustment Scale (SAS), Experiences in Close Relationships Scale (ECR) and Working Alliance Inventory (WAI). Littleton et al. (Citation2016) used the Stressful Life Events Screening Questionnaire (SLESQ) to measure interpersonal violence.

Two instruments were used to assess the extents of feelings of shame or guilt. The Differential Emotions Scale (DES) measured shame in one study (Talbot et al., Citation2011), and the intensity, vividness, uncontrollability and distress of feeling contaminated were measured (Jung & Steil, Citation2013). The Trauma-Related Guilt Inventory (TRGI) was used to measure trauma-related guilt, hindsight bias, lack of justification and sense of wrongdoing (Resick et al., Citation2002).

Meta-analytical results

The main outcomes of the psychological interventions of the studies reported in the 10 articles were post-traumatic stress, depression, anxiety and social adjustment. The effect sizes on the outcomes were organized according to the follow-ups after the intervention (3, 6 and 12 months), and the results, expressed as standardized mean differences (SMD), are as follows and as shown in .

Table 3. Effect sizes of main outcomes, heterogeneity, and at follow-up (df = degrees of freedom; SMD = standardized mean difference; CI = 95% confidence interval).

Post-traumatic stress

The mean effect size of the nine studies with interventions for post-traumatic stress was moderate (SMD = −0.51, 95% CI: −0.71 to −0.30), and the change was statistically significant and positive (Z = 4.73, p < .001). At the 3-month follow-up, the mean effect size was moderate (SMD = −0.68, 95% CI: −1.03 to −0.33), positive, and statistically significant (Z = 3.78, p < .001). At the 12-month follow-up, the mean effect size was moderate (SMD = −0.41, 95% CI: −0.80 to -0.03), positive and statistically significant (Z = 2.09, p = .04).

Depression

Eight interventions followed up on depression outcomes. Depression was moderately influenced (SMD = −0.65, 95% CI: −0.89 to −0.42) with positive and statistically significant change (Z = 5.50, p < .001). At 3 months post-intervention, the mean effect size was small (SMD = −0.48, 95% CI: −0.83 to −0.13), but the change was positive and statistically significant (Z = 2.71, p = .007). At the 6-month follow-up, the mean effect size remained small (SMD = −0.29, 95% CI: −0.67 to 0.10) and the change was not statistically significant (Z = 1.45, p = .15).

Anxiety

The initial mean effect size on anxiety in four studies was small (SMD = −0.27, 95% CI: −0.58 to 0.03) and the change was positive and statistically significant (Z = 1.75, p = .08). At the 3-month follow-up, the mean effect size was small (SMD = −0.18, 95% CI: −0.72 to 0.36) and the change was not statistically significant (Z = 0.64, p = .52).

Social adjustment

Two studies assessed social adjustment. The mean effect size was small (SMD = −0.13, 95% CI: −0.48 to 0.21), positive and not statistically significant (Z = 0.76, p = 0.45). At the 3-month follow-up, the mean effect size also was small (SMD = −0.13, 95% CI: −0.48 to 0.21), positive and not statistically significant (Z = 0.76, p = .45). At 12 months post-intervention, the mean effect size was small (SMD = 0.01, 95% CI: −0.37 to 0.39) and not statistically significant (Z = 0.06, p = .95).

Heterogeneity

The post-traumatic stress outcomes (I2 = 90%, χ2 = 71.18, p < .001) and depression outcomes (I2 = 80%, χ2 = 30.49, p < .001) were considerably heterogeneous. Anxiety was substantially heterogeneous (I2 = 65%, χ2 = 8.59, p = .04). In addition, some of the variables used to assess results varied, such as subject characteristics (i.e., college, hospital or community center sample), duration of intervention (from 4.5 to 36 weekly therapy sessions) and duration of session (from 9 to 120 minutes on average).

The outcomes were measured in various ways. For example, the subjects were assessed regarding childhood sexual abuse (Chard, Citation2005; Jung & Steil, Citation2013; Smith et al., Citation2012; Talbot et al., Citation2011), rape (Foa et al., Citation1991; Littleton et al., Citation2016; Resick et al., Citation2002) or sexual assault (Krakow et al., Citation2001; Miller et al., Citation2015; Zoellner et al., Citation1999). The data collection methods varied: Post-traumatic stress symptom interviews (Krakow et al., Citation2001; Littleton et al., Citation2016; Smith et al., Citation2012; Talbot et al., Citation2011; Zoellner et al., Citation1999) and PTSD diagnoses (Chard, Citation2005; Foa et al., Citation1991; Jung & Steil, Citation2013; Resick et al., Citation2002), including depressive symptoms (Smith et al., Citation2012; Talbot et al., Citation2011) or including current medications (Krakow et al., Citation2001; Resick et al., Citation2002; Smith et al., Citation2012; Talbot et al., Citation2011).

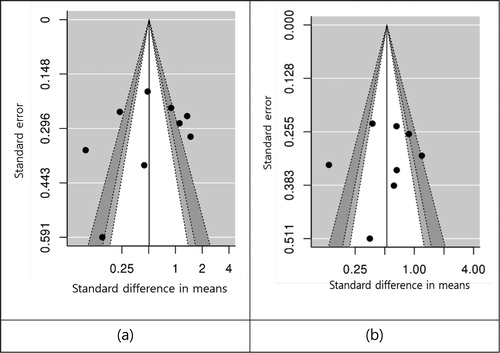

Publication bias

To identify publication bias, the extent of asymmetry was confirmed using a funnel plot, which was evenly distributed in the non-significant region and asymmetrical (). The statistical significance of the asymmetry was not tested using Egger’s regression test (Egger, Smith, Schneider, & Minder, Citation1997) because there were fewer than 10 articles in the meta-analysis. Overall, the NFS was calculated to determine the credibility of the results, and the NFS indicated that 124 studies would be needed to dismiss the present significance. If the number of missing studies were sufficiently large, the publication bias would not be large, so this study’s publication bias is relatively incorrect.

Risk of bias

Regarding risk of bias, the articles in the sample were limited to RCTs and there was a relatively low risk of bias. Random sequence generation was specified as random assignment in eight articles. Littleton et al. (Citation2016) used a computerized coin flip and Krakow et al. (Citation2001) used a postcard time and date to minimize the risk of bias. In the one study that used allocation concealment, the subjects did not know the group to which they would be assigned when they were recruited. Littleton et al. (Citation2016) used a web-based and Krakow et al. (Citation2001) used a computer-generated assignment, and both studies evaluated a low risk of bias without exposure to the subjects and researchers. The other eight studies did not disclose any information about the ways they handled risk of bias.

Talbot et al. (Citation2011) considered performance bias low risk by providing an intervention that distinguished among research assessors, investigators and therapists. Detection bias was found to not influence the outcomes, but the objective outcome variables were limited because post-traumatic stress, depression, anxiety and social adjustment were subjectively measured.

Attrition bias was considered low risk in nine of the 10 articles’ studies. The intention to treat was assessed in five studies (Chard, Citation2005; Jung & Steil, Citation2013; Krakow et al., Citation2001; Littleton et al., Citation2016; Resick et al., Citation2002), and generalized estimating equations were applied in two studies (Smith et al., Citation2012; Talbot et al., Citation2011) to statistically handle missing values. In addition, the Zoellner et al. (Citation1999) and Foa et al. (Citation1991) studies found no differences between the followed group and those who dropped out and concluded there was a low risk of attrition bias. Reporting bias was considered a result of the research design and all 10 studies were low risk.

Discussion

This study systematically examined the reports in published articles of randomized controlled trials on psychological interventions for women traumatized by sexual abuse. It analyzed the effect sizes of the outcome variables post-intervention and at 3-, 6-, and 12-month follow-ups in a meta-analysis. The interventions influenced post-traumatic stress up to 12 months post-intervention, and the effects on depression were statistically significant up to 3 months later. Anxiety and social adjustment were not significantly different at follow-up than immediately after the intervention.

Kim et al. (Citation2016) found that psychological reactions/responses to abuse or trauma, such as symptoms of post-traumatic stress, depression, anxiety, fear and distress, significantly improved in response to cognitive behavioral therapy, which we found was a common psychological intervention for victims of childhood sexual abuse and/or trauma. Previous results indicated that post-traumatic stress, trauma symptoms, interpersonal functioning and self-esteem were effectively treated immediately post-intervention and the positive effect persisted for at least 6 months (Taylor & Harvey, Citation2010). Sexual abuse and/or trauma require personalized interventions because the extent of post-traumatic stress varies. It also is necessary to repeat interventions to maintain their effects in the long term.

The sexual abuse and/or trauma interventions were administered at the individual level, in groups, or in a combination of the two, but the individual format was the most frequent approach. Stalker and Fry (Citation1999) found that individual and group therapy effectively reduced feelings of stress and guilt and improved the overall functioning of traumatized victims of sexual abuse. However, group interventions are limited because deep interventions are difficult in cases of sexual trauma, and victims have difficulty sharing. Therefore, because victims have unique experiences with varying extents of severity and of post-traumatic stress, individual-level interventions with duration controls have been relatively effective (Freedman & Enright, Citation1996). The individual approach is better for interpersonal psychotherapy regarding social and mental functioning (Talbot et al., Citation2011). In addition, a female therapist’s personal approach to treating women effectively relieved post-traumatic stress symptoms (Foa et al., Citation1991). Therefore, it is necessary to tailor the approaches to fit the reasons for the intervention.

The articles selected for this study’s sample measured the subjects’ emotional responses, interpersonal and social adjustment factors and sleep-related physiological factors. Negative scores mostly related to the subjects’ mental health and emotions. The most frequently observed outcomes were post-traumatic stress, depression and anxiety. Positive characteristics measured by the studies were self-esteem (to indicate a sense of self-worth), life satisfaction and a sense of success. Sleep quality and nightmare frequency were tested using physical instruments.

Cognitive imagery treatment was used in group therapy to improve physical symptoms after a 5-week intervention. Social factors were not consistently discussed, but some ideas were generally confirmed. We considered cognitive behavior therapy and interpersonal psychotherapy as ways to improve social functions, develop new relationships, learn how to effectively communicate and learn how to function as a social person. Therefore, we identified a need to comprehensively intervene in biopsychosocial ways for victims experiencing physical, mental and social problems after sexual abuse and/or trauma.

We concluded that most of the quality assessments regarding the RCTs of the studies in the 10 articles had a low risk of bias. However, we found the allocation concealment of subjects and researchers unclear in eight studies, and the blinding of study subjects and personnel was unclear in nine of the 10 studies. The nature of the psychological interventions might have made it difficult to achieve a blind treatment for the researchers and subjects (Olthuis et al., Citation2016). Even in cases of psychological interventions, RCTs need to apply a variety of methods for randomization and blinding, and it is important to disclose the information in results and reports.

There was significant heterogeneity among the psychological interventions. Cognitive therapy was the most common intervention; however, it varied among cognitive behavioral therapy, cognitive restructuring and imagery modification, cognitive processing therapy and cognitive imagery treatment. In addition, there were various intervention administrators, which were therapists, nurses, clinicians and psychologists, and the mode of delivery was individual-level (six studies), group (one study) or combined individual and group sessions (two studies).

The articles were compared regarding online, video or face-to-face intervention format, duration of intervention (in minutes), number of sessions and the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Therefore, this study’s results were interpreted with caution because of the variety of selection and analytical approaches among the studies. It also was necessary to select one article, compare its study’s effects and perform meaningful subgroup analyses after the intervention. Publication bias was confirmed as asymmetrical, but the NFS was 124 studies. Because meta-analytical statistics were not appropriate and there were excluded studies, repeat meta-analyses are needed.

This study’s limitations are as follows. First, the sample size was small for conducting a statistical meta-analysis and the differences in the effects of the interventions between groups and individuals were not tested. Second, the cognitive behavioral therapy effect sizes were not compared to those of other interventions. However, this study’s results are useful because they confirmed the effects of psychological interventions within 1 year of intervention. Future studies should verify discriminative effects by specifying the various intervention methods used to help victims of sexual abuse and/or trauma.

Conclusion

This study conducted a systematic meta-analysis of articles reporting on RCT intervention studies that used psychological interventions for adult women victims of sexual abuse and/or trauma. It statistically analyzed the effect sizes of the outcome variables. The results found that the interventions were effective for post-traumatic stress and depression, but not for anxiety and social adjustment, in follow-up assessments. Therefore, this study provides objective evidence to support the development of interventions for female sexual abuse and/or trauma victims regarding psychological outcomes.

Supplemental Material

Download PDF (44.2 KB)Disclosure statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest.

References

- Arata, C. M. (2002). Child sexual abuse and sexual revictimization. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 9(2), 135–164. doi:10.1093/clipsy.9.2.135

- Chard, K. M. (2005). An evaluation of cognitive processing therapy for the treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder related to childhood sexual abuse. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 73(5), 965–971. doi:10.1037/0022-006X.73.5.965

- Cho, Y. S., Song, J., & Lee, J. Y. (2016). Introduction to online based trauma-focused cognitive behavioral therapy education program for helping sexually abused people. Anxiety and Mood, 12(2), 79–85.

- Chouliara, Z., Karatzias, T., & Gullone, A. (2014). Recovering from childhood sexual abuse: A theoretical framework for practice and research. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing, 21(1), 69–78. doi:10.1111/jpm.12048

- Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- Egger, M., Smith, G. D., Schneider, M., & Minder, C. (1997). Bias in meta-analysis detected by a simple, graphical test. BMJ, 315(7109), 629–634. doi:10.1136/bmj.315.7109.629

- Felitti, V. J., Anda, R. F., Nordenberg, D., Williamson, D. F., Spitz, A. M., Edwards, V., … Marks, J. S. (1998). Relationship of childhood abuse and household dysfunction to many of the leading causes of death in adults: The Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACE) Study. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 14(4), 245–258. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2019.04.001

- Fergusson, D. M., Boden, J. M., & Horwood, L. J. (2008). Exposure to childhood sexual and physical abuse and adjustment in early adulthood. Child Abuse & Neglect, 32(6), 607–619. doi:10.1016/j.chiabu.2006.12.018

- Finestone, H. M., Stenn, P., Davies, F., Stalker, C., Fry, R., & Koumanis, J. (2000). Chronic pain and health care utilization in women with a history of childhood sexual abuse. Child Abuse & Neglect, 24(4), 547–556. doi:10.1016/s0145-2134(00)00112-5

- Foa, E. B., & Kozak, M. J. (1986). Emotional processing of fear: Exposure to corrective information. Psychological Bulletin, 99(1), 20. doi:10.1037//0033-2909.99.1.20

- Foa, E. B., Rothbaum, B. O., Riggs, D. S., & Murdock, T. B. (1991). Treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder in rape victims: A comparison between cognitive-behavioral procedures and counseling. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 59(5), 715–723. doi:10.1037//0022-006X.59.5.715

- Freedman, S. R., & Enright, R. D. (1996). Forgiveness as an intervention goal with incest survivors. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 64(5), 983–992. doi:10.1037//0022-006x.64.5.983

- Higgins, J. P. T., & Green, S. (Eds.). (2011). Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions version 5.1.0. West Sussex, England: The Cochrane Collaboration.

- Jung, K., & Steil, R. (2013). A randomized controlled trial on cognitive restructuring and imagery modification to reduce the feeling of being contaminated in adult survivors of childhood sexual abuse suffering from posttraumatic stress disorder. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics, 82(4), 213–220. doi:10.1159/000348450

- Kim, S., Noh, D., & Kim, H. (2016). A summary of selective experimental research on psychosocial interventions for sexually abused children. Journal of Child Sexual Abuse, 25(5), 597–617. doi:10.1080/10538712.2016.1181692

- Krakow, B., Hollifield, M., Johnston, L., Koss, M., Schrader, R., Warner, T. D., … Prince, H. (2001). Imagery rehearsal therapy for chronic nightmares in sexual assault survivors with posttraumatic stress disorder: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of the American Medical), 286(5), 537–545. doi:10.1001/jama.286.5.537

- Littleton, H., Grills, A. E., Kline, K. D., Schoemann, A. M., & Dodd, J. C. (2016). The From Survivor to Thriver program: RCT of an online therapist-facilitated program for rape-related PTSD. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 43, 41–51. doi:10.1016/j.janxdis.2016.07.010

- Miller, K. E., Cranston, C. C., Davis, J. L., Newman, E., & Resnick, H. (2015). Psychological outcomes after a sexual assault video intervention: A randomized trial. Journal of Forensic Nursing, 11(3), 129–136. doi:10.1097/JFN.0000000000000080

- Olthuis, J. V., Wozney, L., Asmundson, G. J., Cramm, H., Lingley-Pottie, P., & McGrath, P. J. (2016). Distance-delivered interventions for PTSD: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 44, 9–26. doi:10.1016/j.janxdis.2016.09.010

- Pereda, N., Guilera, G., Forns, M., & Gómez-Benito, J. (2009). The prevalence of child sexual abuse in community and student samples: A meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology Review, 29(4), 328–338. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2009.02.007

- Pérez-Fuentes, G., Olfson, M., Villegas, L., Morcillo, C., Wang, S., & Blanco, C. (2013). Prevalence and correlates of child sexual abuse: A national study. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 54(1), 16–27. doi:10.1016/j.comppsych.2012.05.010

- Resick, P. A., Nishith, P., Weaver, T. L., Astin, M. C., & Feuer, C. A. (2002). A comparison of cognitive-processing therapy with prolonged exposure and a waiting condition for the treatment of chronic posttraumatic stress disorder in female rape victims. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 70(4), 867–879. doi:10.1037//0022-006X.70.4.867

- Resick, P. A., & Schnicke, M. K. (1992). Cognitive processing therapy for sexual assault victims. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 60(5), 748–756. doi:10.1037//0022-006X.60.5.748

- Rosenthal, R. (1979). The file drawer problem and tolerance for null results. Psychological Bulletin, 86(3), 638–641. doi:10.1037/0033-2909.86.3.638

- Smith, P. N., Gamble, S. A., Cort, N. A., Ward, E. A., He, H., & Talbot, N. L. (2012). Attachment and alliance in the treatment of depressed, sexually abused women. Depression and Anxiety, 29(2), 123–130. doi:10.1002/da.20913

- Stalker, C. A., & Fry, R. (1999). A comparison of short-term group and individual therapy for sexually abused women. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry [Revue Canadienne de Psychiatrie], 44(2), 168–174. doi:10.1177/070674379904400208

- Talbot, N. L., Chaudron, L. H., Ward, E. A., Duberstein, P. R., Conwell, Y., O'Hara, M. W., … Stuart, S. (2011). A randomized effectiveness trial of interpersonal psychotherapy for depressed women with sexual abuse histories. Psychiatric Services, 62(4), 374–380. doi:10.1176/appi.ps.62.4.374

- Taylor, J. E., & Harvey, S. T. (2010). A meta-analysis of the effects of psychotherapy with adults sexually abused in childhood. Clinical Psychology Review, 30(6), 749–767. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2010.05.008

- World Health Organization (2014). Global status report on violence prevention 2014. Retrieved from https://www.who.int/violence_injury_prevention/violence/status_report/2014/report/report/en/.

- Zoellner, L. A., Feeny, N. C., Fitzgibbons, L. A., & Foa, E. B. (1999). Response of African American and Caucasian women to cognitive behavioral therapy for PTSD. Behavior Therapy, 30 (4), 581–595. doi:10.1016/S0005-7894(99)80026-4