Abstract

Mental ill-health has been termed the pandemic of the 21st century, and a large share of those exposed do not receive treatment. Many people with depression, anxiety and other mental health problems consult complementary or alternative medicine (CAM), and CAM is used in conventional psychiatric care, in Sweden and in other countries. However, the extent to which CAM is used in psychiatric care, and for what purposes, are largely unknown. This study is based on a survey distributed to all heads of regional, municipal, private and governmental health care units treating persons with psychiatric symptoms across Sweden in 2019. CAM was reportedly used by 62% of the 489 responding health care units, for symptoms including anxiety, sleep disturbances and depression. Main motivations for CAM use were symptom relief, meeting patients’ requests and reduced demand for pharmaceutical medication. Very few respondents reported side effects. The most common reason for interrupting CAM use at a unit was a lack of trained professionals. This study confirms the need for further research about CAM, and for CAM education and training among healthcare professionals.

Introduction

While mental illness has been estimated to cause one third of the disability of adults worldwide (Whiteford et al., Citation2013), fewer than half of those affected receive treatment (WHO, Citation2017). Many people with depression, anxiety and other mental health problems consult complementary or alternative medicine (CAM), and CAM is used in conventional psychiatric care, in Sweden (Lindell & Ek, Citation2010) and in other countries (Horrigan et al., Citation2012). For the purpose of clarifying whether or how CAM can be of benefit for patients in Swedish psychiatric care, and enabling properly informed and regulated integration of CAM in Swedish healthcare (SOU 2019:15, Citation2019), it is important to know the degree to which CAM is used in psychiatric care today. It is further of relevance what types of CAM are utilized, and for what symptoms. Therefore, this study, which is based on a survey distributed to heads of institutions responsible for psychiatric healthcare throughout Sweden in 2019, measures the use of CAM in Swedish psychiatric care.

Complementary and alternative medicine (CAM)

According to the US National Institutes of Health (NIH), CAM consists of “a group of diverse medical and health care systems, practices, and products that are not presently considered to be part of conventional medicine” (NCCAM., Citation2006). While the use of these concepts differs somewhat between contexts and actors, complementary medicine typically refers to therapy used in combination with conventional medicine, also by health care personnel, while alternative medicine is a term for practices used instead of it. Integrative medicine refers to the actual or potential integration of complementary methods in conventional healthcare (Jensen et al., Citation2007; SOU 2019:15, Citation2019). Eklöf and Kullberg (Citation2004) distinguish between four types of CAM practice. The first is comprised of CAM treatments outside of conventional healthcare, paid by the patient. The second consists of patients seeking licensed practitioners such as chiropractors through referral from conventional care, while the third encompasses licensed healthcare personal practicing forms of CAM within conventional care. The fourth group consists of close cooperation, under the ‘same roof’, between healthcare personnel and CAM therapists. CAM encompasses a wide variety of different practices, which the NIH (Jensen et al., Citation2007; NCCAM., Citation2006) divide into alternative medical systems (e.g., Chinese medicine and Ayurvedic medicine), mind-body interventions (e.g., meditation and mental training), biologically based therapies (e.g., herbs and nutritional supplements), manipulation therapies (e.g., chiropractic and massage), and energy therapies (e.g., healing).

The many different types of CAM, and the varied settings in which it is practiced, contribute to making CAM a difficult phenomenon to delineate and measure. Still, existing research suggests that a large and possibly growing number of people around the world use CAM (Clarke et al., Citation2015; D’Onise et al., Citation2013; Eardley et al., Citation2012; Frass et al., Citation2012; Harris et al., Citation2012; Hunt et al., Citation2010), which is arguably subject to “exponential growth” around the world (Adams, Citation2007, p 75). Also in Sweden, research suggests that CAM forms a considerable part of the health care offered to and used by the population. According to a study from 2001 (Eklöf & Tegern, Citation2001), 49% of the population of Stockholm had used CAM, while another study from 2017 (Wemrell et al., Citation2017) reported that 71% of the respondents had used some form of CAM in the past year. Commonly used methods, alongside chiropractic care and naprapathy which should arguably not be seen as CAM but as part conventional care (SOU 2019:15, Citation2019), are massage, acupuncture, various nutritional supplements and natural remedies and self-help practices such as yoga (SOU 2019:15, Citation2019). CAM use has been found to be more common among women and persons with high education, in Sweden (Hornborg, Citation2012; SOU 2019:15, Citation2019; Wemrell et al., Citation2017) and internationally (Hansen & Kristoffersen, Citation2016; Hoenders et al., Citation2011; Rhee et al., Citation2017; Solomon & Adams, Citation2015; Taylor, Citation2010). However, reliable research into the prevalence of CAM use in Sweden is sparse (SOU 2019:15, Citation2019).

Internationally, recent decades have seen an increase in the number of patients seeking integrative care, medical schools teaching integrative strategies, and clinical centers offering integrative medicine (Horrigan et al., Citation2012). This trend is supported by the WHO (Citation2013). Still, prevalence research on CAM within Swedish healthcare is even more limited than that of overall CAM use (Jensen et al., Citation2007; SOU 2019:15, Citation2019). According to available knowledge, CAM use varies considerably between the different counties of Sweden (SOU 2019:15, Citation2019). In one survey study (Wemrell et al., Citation2016), 8% of the respondents (10% of the women and 6% of the men) reported having received a complementary treatment by healthcare personnel or through referral in the last year, most commonly acupuncture (22%), massage (21%) or mindfulness (15%). Furthermore, 69% of all the respondents (76% of the women and 63% of the men) wanted collaboration between conventional medicine and CAM to increase (Wemrell et al., Citation2017). In a study of CAM use among nurses in Sweden (Jong et al., Citation2015), 11% reported having practiced CAM, while 43% stated that they wished to practice a CAM method in the future. A mapping of CAM use in Swedish psychiatric care (Lindell & Ek, Citation2010) found that CAM methods were applied in a third of the responding municipal institutions for adults, and in almost half of the responding regional institutions. Frequently used methods included acupuncture and tactile massage, offered to treat symptoms such as anxiety and insomnia and to decrease the use of pharmaceutical medication. Survey studies have furthermore shown that medical practitioners, primarily nurses, perceived their level of knowledge about CAM to be low (Bjersa et al., Citation2011; Citation2012; Jong et al., Citation2015; Lindberg et al., Citation2013), while many emphasized that such knowledge is important, not least to inform patients who make inquiries about CAM (Bjersa et al., Citation2012; Jong et al., Citation2015). Jong et al. (Citation2015) conclude that there is a need for education about CAM at Swedish nursing schools. However, Swedish tertiary education at large offers a very limited number of courses on CAM (SOU 2019:15, Citation2019).

On a legislative note, licensed healthcare professionals can, according to the 2010 Patient Safety Act (Högsta Förvaltningsdomstolen, Citation2011; SFS 2010:659, Citation2010) provide safe CAM treatments on the demand of informed patients, as long as conventional treatment is not withheld (Jong et al., Citation2015).

While it is evident that CAM is demanded and used by many people in Sweden, within and outside of conventional healthcare, an obstacle for furthered integrative care is the question of the degree to which specific CAM methods are scientifically validated (e.g., SOU 2019:15, Citation2019). While the amount of research on CAM has increased, the results are largely inconclusive (Institute of Medicine (U.S.), Citation2005; SOU 2019:15, Citation2019). Several efforts toward gathering information and research about different CAM methods, not least for use in the context of mental health problems, have been made (Cochrane, Citation2019; Ernst, Citation2006; Hoenders et al., Citation2011; Lake & Spiegel, Citation2006; Mischoulon & Rosenbaum, Citation2008).

Another objection concerns the safety of CAM methods, and the existence of side effects and potential interactions with conventional pharmaceuticals (SOU 2019:15, Citation2019). While many CAM users expect the risk of side effects to be smaller than in conventional care (Ernst & Hung, Citation2011), and research to some degree supports this (Wainapel et al., Citation2015), side effects of CAM methods do exist. The perhaps greatest risk of CAM use is the possible delay of effective, conventional treatment (Freeman et al., Citation2010; SOU 2019:15, Citation2019).

While economic research on CAM is limited, studies indicate that use of CAM can be cost-effective or cost saving, in comparison with conventional care (Herman et al., Citation2012).

Mental ill-health and CAM

Mental ill-health, which causes enormous suffering for individuals and massive costs for society, has been termed the pandemic of the 21st century and the next major public health challenge (Lake & Turner, Citation2017). In 2010, an estimated 38.2% of the population of the EU member states (approximately 165 million people) met the criteria for a psychiatric disorder, while fewer than one-third received treatment for it (Wittchen et al., Citation2011). Globally, mental ill-health represents an area of large unmet healthcare needs (Lake & Turner, Citation2017; WHO, Citation2017). The evidence supporting pharmacological treatments of psychiatric disorders such as depression is debated (Cuijpers et al., Citation2011; Ioannidis, Citation2008; McCormack & Korownyk, Citation2018), and serious side effects exist (Henderson, Citation2008; NHS, Citation2018).

Many people with depression, anxiety and other mental health problems use CAM (Bystritsky et al., Citation2012; Freeman et al., Citation2010; Solomon & Adams, Citation2015; Wu et al., Citation2007), as shown in studies from the USA (Druss & Rosenheck, Citation2000; Grzywacz et al., Citation2006), Australia (Alderman & Kiepfer, Citation2003; Spinks & Hollingsworth, Citation2012) and Norway (Hansen & Kristoffersen, Citation2016). A study of CAM use for mental health problems among adults in 25 countries (de Jonge et al., Citation2018) found that in high income countries, 4.6% of respondents with a past 12-month mental disorder reported use of CAM. CAM use was more common among persons receiving conventional care (8.6-17.8%) and increased with mental disorder severity. The reported satisfaction with care was slightly higher for CAM (82.1%) than for conventional care (75.6%) (de Jonge et al., Citation2018). CAM is used both instead of (Hansen & Kristoffersen, Citation2016) and alongside (de Jonge et al., Citation2018; Hansen & Kristoffersen, Citation2016; Solomon & Adams, Citation2015) conventional care, for purposes of treating mental health concerns.

With regard to Australia, Spinks and Hollingsworth (Citation2012) conclude that CAM is obviously considered to be a legitimate and important component of health care for many, despite the limited availability of documented evidence for its efficacy and safety. Lake and Turner (Citation2017) argue that the widespread use of CAM by patients also receiving conventional treatment for mental health problems is driving a trend toward increasingly integrative mental health care in many high-income countries, and a review of clinical centers providing integrative medicine in the USA (Horrigan et al., Citation2012) notes that depression was among the five clinical conditions for which integrative services were perceived to be used most successfully. Still, Solomon and Adams (Citation2015) observe that CAM is the least researched form of treatment for mental health problems. In existing CAM research, however, gathered for example in the Cochrane Library’s section on Complementary Medicine (Cochrane, Citation2019), mental health is one of the most common areas of interest (SOU 2019:15, Citation2019). This is in alignment with Freeman et al. (Citation2010) conclusion that due to the widespread use of CAM therapies among persons with mental health problems, clinical, research, and educational initiatives focused on CAM in psychiatry are clearly warranted.

The effects of CAM on mental health

Acupuncture is included, since 1993 (SOSFS 1993:18, Citation1993), among methods offered by Swedish healthcare for certain ailments, and it is one of the CAM modalities used in Swedish psychiatric care (Lindell & Ek, Citation2010). While a large share of the research on the effects of acupuncture has yielded inconclusive results (Pilkington, Citation2010; Smith et al., Citation2018), acupuncture has been proven to be effective for anxiety (Arvidsdotter et al., Citation2014; Li et al., Citation2019), depression (Chan et al., Citation2015; Hou et al., Citation2015) and insomnia (Cao et al., Citation2009; Hou et al., Citation2015; Wainapel et al., Citation2015). For treatment of anxiety, ear acupuncture has been found to be as effective as pharmaceutical medication (Pilkington et al., Citation2007). A systematic review of acupuncture combined with antidepressant medication (Chan et al., Citation2015) showed that this combination was more effective than SSRI therapy alone, while acupuncture reduced the side effects of the medications.

Another CAM method used in Swedish healthcare (SOU 2019:15, Citation2019) is mindfulness, which has been found to improve symptoms of anxiety and depression (Goyal et al., Citation2014; Lorenc et al, Citation2018; SBU, Citation2014). Tactile massage, or tactile stimulation, also applied in Swedish healthcare (Lindell & Ek, Citation2010), has been reported to reduce anxiety and agitation among patients with dementia (Skovdahl et al., Citation2007; Suzuki et al., Citation2010). Massage has also been found effective for treating anxiety and depression among children with cancer (Hughes et al., Citation2008).

Alongside clinical trials seeking to document the effects of CAM methods, functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) has documented effects of acupuncture (Bai et al, Citation2010) and mindfulness (Kilpatrick et al., Citation2011) in the brain. Meanwhile, biological explanations for the effects of acupuncture point toward the autonomic nervous system and to regulation of blood pressure, cortisol and other stress-induced biomarkers, as well as to normalization of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis (Darbandi et al., Citation2016; Fang et al., Citation2009). Ear acupuncture has been explained with reference to stimulation of the vagus and trigeminal nerves (He et al., Citation2012; Mercante et al., Citation2018).

Furthermore, studies have documented the self-assessed effects of CAM practices, as noted by patients (Lindell & Ek, Citation2010) and providers (Horrigan et al., Citation2012; Lindell & Ek, Citation2010). As in the noted study by de Jonge et al. (Citation2018), survey respondents in Sweden (Wemrell et al., Citation2016) and internationally (Kessler et al., Citation2001) have indicated that they were at least as satisfied with CAM services as with conventional therapies. Motivating factors for consulting CAM practitioners, in general (Sirois, Citation2008) and for mental health problems (Solomon & Adams, Citation2015), include observed symptom relief. With regards to acupuncture, for example, positive effects noted by psychiatric patients include calmness and relaxation (Bergdahl et al., Citation2014; Hedlund & Landgren, Citation2017), while healthcare practitioners at psychiatric clinics have pointed to beneficial effects on anxiety, insomnia, depression and withdrawal symptoms, and a relative absence of side effects, particularly compared to those of pharmaceutical medication (Landgren et al., Citation2019). It should be noted, however, that not all patients are helped by CAM (Lindell & Ek, Citation2010).

Swedish psychiatric care

In Sweden, persons with psychiatric symptoms are cared for by regional, municipal, private or governmental health care organizations. The 21 regions provide in- and outpatient care, while the 290 municipalities are responsible for social services including care for elderly, persons with physical or intellectual impairments, psychiatric diseases or substance abuse problems. Private actors range from outpatient clinics run by a single psychotherapist, psychologist or psychiatrist, to larger multi-professional outpatient clinics, and privately-run treatment homes. Finally, persons who are sentenced to compulsory care for psychosocial or substance abuse problems, ordered by the Administrative Court (Förvaltningsrätten), are cared for by the governmental National Board of Institutional Care (Statens Institutionsstyrelse, SiS).

For the purpose of contributing to the limited knowledge about CAM use in Swedish psychiatric care (Lindell & Ek, Citation2010), in accordance with a report from the Swedish Ministry of Health and Social Affairs emphasizing the importance of further research on CAM (SOU 2019:15, Citation2019), this study aims to map the use of CAM methods in Swedish psychiatric care.

Methods

Study design

This is a descriptive study based on a web-based questionnaire distributed in 2019 to the heads of all in- and outpatient regional, municipal, private and governmental units treating persons with psychiatric symptoms in Sweden. The survey posed questions about which, if any, CAM methods were used, and for what purpose.

Participants and data collection

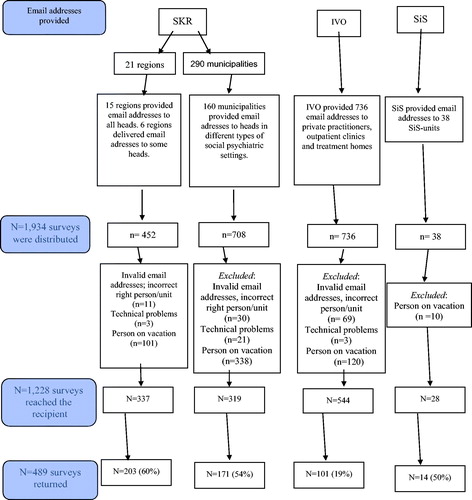

All 21 regions were contacted and asked for email addresses to the head of every psychiatric in- and outpatient unit, which resulted in 452 addresses (). Likewise, all 290 municipalities were asked for email addresses to the head of every municipal unit for social psychiatry, resulting in 708 addresses. The Health and Social Care Inspectorate (IVO), a governmental agency responsible for supervision of healthcare, provided email addresses to all 736 private units (including psychologists’ and psychotherapists’ clinics, multi-professional outpatient clinics and treatment homes) registered to provide psychiatric care, while the SiS provided email addresses to the heads of its 38 units. In total, 1,934 email addresses were collected. After the removal of nonfunctioning addresses, and addresses to persons who replied that they were not on duty or did not work in psychiatric care, 1,228 addresses remained on the send list ().

Figure 1. Flow chart showing how email addresses to the heads of departments were collected, and the frequency of response to the survey. IVO = The Health and Social Care Inspectorate. SKR = The Swedish Association of Local Authorities and Regions. SiS = The National Board of Institutional Care.

The questionnaire was constructed for the purpose of this study, and posed questions about whether, and if so which, CAM methods were used within the respective unit, the reason for using of having stopped using CAM, which groups of patients that were offered CAM, and for which symptoms. A range of types of CAM were listed, and the respondents were asked to indicate whether or not it was used at their unit (yes/no). The listed methods were massage/tactile stimulation, acupuncture including NADA (standardized ear acupuncture), yoga/Qigong/Tai Chi, mindfulness, light therapy, music/dance/art therapy/drama, horticultural therapy, animal assisted therapy, and basal body awareness. All these methods are listed as CAM in a public investigation from the Ministry of Health and Social Affairs (SOU 2019:15, Citation2019), while some listed methods were excluded due to our assumption that they would not commonly be offered in conventional health care (e.g., homeopathy). Most survey questions were of multiple-choice character, while some offered space for open text responses. It took approximately 6 minutes to complete the survey. The survey was built, distributed and managed with the aid of the application Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap) (Vanderbilt REDCap, version 8.1.7). Information about the professional background of the heads of the care units, who may be doctors, nurses, psychologists or other, was not gathered.

A link to the electronic survey, which could not be forwarded to another recipient, was sent by email to the 1,934 addresses in June 2019. Two reminders were sent the week after, and another in August 2019, to those who had not responded.

Data analysis

Descriptive statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS version 19 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY). The text responses were analyzed through manifest content analysis (Kondracki et al., Citation2002), through which the contents of the survey responses was sorted into categories. This analysis was first performed by the last author, and discussion about adjustment of categories were held between all authors until consensus was obtained.

Ethical considerations

No sensitive personal information was gathered, and the study population (heads of psychiatric care units) was not considered to be vulnerable. Therefore, solicitation of approval from the Ethical Review Authority was not deemed necessary.

Results

Of the 1,228 surveys who probably reached a relevant person, 489 were completed (). The response rate was thus 40%.

Description of the units

Among the 203 regional units who responded, 74 were in-patient clinics, 137 were outpatient clinics, and 12 were daycare units. Some units provided more than one of these types of care. The 171 responding municipal units described a wide variety of activities. 99 units were described as residential, 75 as residential support, 49 as daytime activities and 15 as rehabilitation. Others referred to supported employment (n = 5) or compulsory substance abuse care (n = 8). In some cases, the responder wrote that no care was provided at the unit, revealing that the questionnaire had been sent to a non-relevant unit. Some answers showed that the email had not reached the head of a unit, but a person in a higher position at the organization. Among the 101 respondents in private psychiatry, 28 were private psychiatrists, 15 were residential care homes for children and young persons (HVB-homes), 11 were psychologists in private practice, 34 represented multi-professional outpatient clinics and 35 described their activity as “other”, including long- or short-term residential care for persons with psychiatric disease and/or addiction. Of the 14 responding SiS units, nine provided compulsory care for teenagers and five for adults. Compulsory care was also reported by some regional and municipal care units.

The most common diagnoses among patients at all participating units were affective disorders, psychosis, addiction, eating disorders and neuropsychiatric diagnoses. Other reported diagnoses were personality disorders, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), obsessive-compulsive disorders (OCD), intellectual developmental disorders and dementia. Eighteen informants commented that the unit treated persons with all kinds of psychiatric diseases, while one (municipal) informant stated that “many of our patients, especially elderly, have not been diagnosed and then we use CAM to treat their symptoms”.

Use of CAM

In total, 62% of the respondents reported use of some form of CAM at their psychiatric health care unit (). Regional care units reported the highest prevalence (67%), while municipal units reported the lowest rate (56%). The most commonly used methods were mindfulness, basal body awareness, massage/tactile stimulation and acupuncture. With regards to acupuncture, 83 units used NADA while 11 used body acupuncture. The question of what other forms of CAM, if any, were used yielded responses including meditation, breath training with bio-feedback, tapping, nutritional supplements and natural remedies, neurofeedback-training, anthroposophical methods, rooms for sensory stimulation, an electric rocking chair with music and affirmations.

Table 1. CAM use. For each type of CAM, there was missing data from 2–4 respondents.

Symptoms treated with CAM

The most commonly reported symptoms treated with CAM were anxiety, sleep disturbances and depression (). The most commonly mentioned symptom reported under “Other diagnoses” was stress (n = 8). Three persons stated that CAM, for example mindfulness, was offered to those patients who wanted it independently of diagnosis.

Table 2. Symptoms treated with CAM. Multiple choices were possible.

Reasons for CAM use

The most commonly listed reasons for the use of CAM were to alleviate symptoms, respond to patient requests and reduce the use of medication on demand (). Among other reasons, informants reported that the CAM method in use enhances therapeutic relationships, increases the self-esteem of patients and the effect of therapeutic talks, enables social contacts and increases body awareness. CAM was also described as person-centered and conducive to patient autonomy and collaborative partnership in care. Other noted reasons were that the staff trusted and liked to offer the treatment, and that patients were grateful for it.

CAM is unbeatable when it comes to sustainable rehabilitation and habilitation. It´s the best for all patients who want to optimize their health. Not only that CAM is the best for the patients but the treatments are also environmentally friendly.” (respondent from a regional psychiatric clinic)

One respondent noted that the region “demanded that we offer Basal Body Awareness despite the absence of evidence”. Mindfulness was seen by other respondents as a conventional component of cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) and dialectical behavior therapy (DBT) and therefore not as CAM.

Perceived evidence-base

The respondents were asked about how strong they perceived the evidence-base for the used form of CAM to be. The most common response was that they did not know ().

Evaluation of effects

Few respondents reported having evaluated the effect of the used form/s of CAM (0–30% of the answers in each cohort). Those who did make evaluations mentioned scales used by patients to rate their symptoms, after each session or before and after a treatment period. Others mentioned evaluation through observing symptoms or asking the patients. One unit measured pulse rate and blood pressure before and after treatment.

Number of treatments

CAM was used both individually and in groups. The reported share of patients who received CAM ranged from none to all. Yearly numbers up to “about 450, 90% of the patients” were mentioned, and patients reportedly received 0–50 CAM-treatments/year. Some informants pointed out that CAM was offered on demand, as long as it was needed.

Perceived side effects

While all respondents answered the question about whether negative side effects from CAM had been seen, only six informants (1% of the respondents) reported having done so. Such reports included mention that an increased body awareness could cause confusion, which was described as mild and transient.

It can be about feelings being awakened, which in the moment and in the short run can be difficult to understand and handle but which in the long run and with the right support can be beneficial. It is good to complement CAM with conversation to catch feelings and provide help in the development. (respondent from private care)

Interrupted CAM treatment

One hundred fifty-three units (31%) had stopped using one or more CAM-methods. The most commonly reported reason for this, noted by 56 units, was a lack of trained professionals. Other stated reasons were lacking evidence-base (n = 26), economic reasons (n = 12), and lack of time (n = 12). Five of those reporting economic reasons for interrupting use of CAM had used animal assisted therapy. The most commonly reported therapy interrupted due to a lacking evidence-base (n = 9) was acupuncture. Forty-seven respondents reported “other reason” for interrupting use of CAM.

Final comments: Critiquing CAM, supporting CAM, discussing efficacy and questioning definitions

The final question, “Is there anything else you would like to add about CAM in psychiatric care?”, was answered by 99 informants. Positive or negative attitudes toward CAM were here expressed in the often lengthy answers. These responses were grouped in four categories: “critiquing CAM”, “supporting CAM”, “discussing the efficacy of CAM” and “questioning definitions of CAM”.

While critiquing CAM, some respondents declared that their units worked according to scientific evidence and national guidelines and therefore did not use CAM. One respondent from regional care noted that CAM use was frivolous in care for persons with psychosis, and another from municipal care discredited it on the basis of its links to New age or Eastern spirituality and religions. Others argued that CAM is incompatible with science.

We are considering stopping the use of NADA acupuncture, because the long-term treatment effect is doubtful for the diagnostic groups currently receiving the treatment. It seems like NADA is more about nursing, providing relief for the moment, than a curative treatment. (respondent from regional care)

Under the category denominated as supporting CAM, CAM was described as a necessary complement to conventional psychiatric care, as occupying a self-evident space within it, and as attracting patients. Informants observed that CAM alleviates symptoms including anxiety, sleep, withdrawal and pain. Acupuncture was noted to reduce depression, which was appreciated as depression is seen to hinder successful CBT. Acupuncture was also described as an interesting option as it enabled reduced use of sedatives and anxiolytics while also diminishing side effects from antidepressants. One respondent claimed that Basal Body Awareness was evidence-based in treatment of psychosis and thus recommended for use. Others argued that CAM methods provided cheap, non-pharmacological complementary forms of care without side-effects, improving patient-therapist alliances and leading to a valuable sense of community when consisting of group activities. CAM was described as a person-centred, and as equally important as medical treatment.

The more we use CAM, the larger demand we see. (a respondent from regional care)

[CAM] is the future, and objective science. It is the patients’ only real hope. (respondent from private care)

Several informants argued that because conventional care, including pharmaceutical medication and counseling or psychotherapy, was not sufficient to fill patients’ needs and did not suit all patients, it was valuable to be able to offer a wider range of care options in accordance with patients´ individual needs and requests. Noted groups of patients that were otherwise often difficult to help were persons with autism, anorexia, intellectual impairment or acquired brain damage, sometimes combined with neuro-psychiatric diagnoses. The possibility of offering CAM to these persons, and to other patients who had little physical contact with others, was seen as a valuable tool for reducing anxiety and frightening thoughts. Patients were perceived to recover faster, and to gain an increased ability for self-regulation, when CAM was added to conventional care.

Horse riding therapy was very good when the patient could not be reached by any other treatment. Unfortunately, we had to stop when one of the professionals retired. (respondent from regional care)

It’s beneficial to be able to offer a bodily treatment, or treatment using nature and animals. It is not so easy for everyone to grasp and express their emotions or needs sitting in a therapy chair. (respondent from municipal care)

Several informants pointed to the importance of helping patients increase the awareness of their bodies. CAM was here described as training persons to use all their senses, and creating a sense of control. It was noted to help patients understand bodily reactions and thereby be able to influence somatic sensations and well-being.

When the psychiatric patients initially come to us, they believe they are solely a BIG head, without body and extremities. We need CAM to obtain contact with the whole person, the whole system, to in the long run achieve a functioning and tolerable everyday life for the patient. (respondent from private care)

Some argued that CAM should be used more extensively in psychiatric care, while some were planning to implement CAM. A few informants whose units did not use CAM referred patients to other care givers, such as a physiotherapist, for the purpose of increased bodily awareness or mindfulness in patients, which was perceived to increase their feeling of security and motivation. CAM was also seen as a way to increase receptivity to and motivation for conventional care.

While discussing the efficacy of CAM, informants pointed out that CAM was not used as an exclusive treatment, but in combination with conventional, evidence-based care, often in a multi-disciplinary context. It was thus noted to be difficult to separate the effects of different parts of the treatments. Also, with regards to CAM methods in themselves, while respondents related their experiences of clinical effects and of patient appreciation, some were uncertain about whether the perceived effect was actually due to the CAM treatment in itself.

Several responses concerned the scientific evidence-base of CAM. Some respondents noted a lack of staff who could perform CAM as the management no longer supported training in CAM methods with weak evidence. Informants arguing that CAM was beneficial and appreciated by patients requested more research comparing CAM with medical treatment, as they noted often getting stuck in discussions on evidence.

There is resistance from senior managers to the use of NADA in psychiatry. It would be good to obtain evidence that it works, alongside us who already know that it does. (respondent from regional care)

Criticism was furthermore directed toward the evaluation of evidence in psychiatric research:

The research asks the wrong questions with an almost complete objectification of the patient and it is therefore of limited value for psychiatric treatment. (respondent in private care)

Questioning definitions of CAM, informants expressed uncertainties about what CAM is, or about how to delineate it. One informant argued that mindfulness should not be defined as CAM as it was used in an evidence-based program based on CBT. When massage was given to teenagers for relaxation, it was not seen as CAM nor as conventional treatment “but more as good nursing” (a respondent from governmental care). Informants described how relaxation in a group, horse riding, activities with dogs, outdoor activities in nature and use of calm music was used in psychiatric care due to being calming, relaxing or stimulating for the senses, but not, or not self-evidently, considered as CAM.

I would say that the day care or middle level care used in BUP [children’s and adolescents psychiatry] today is largely CAM. (respondent from regional care)

Discussion

As noted by Solomon and Adams (Citation2015), the use of CAM for mental health problems has important clinical and public health implications. In recent years, and with support from the WHO (Citation2013), significant efforts have been made in many countries to integrate CAM into conventional healthcare institutions (de Jonge et al., Citation2018). This study shows that to a degree, such integration has also occurred in Swedish psychiatric care.

CAM was in the present study used at 62% of the responding units treating persons with psychiatric diagnosis and/or addiction. CAM was reportedly used to relieve patients’ symptoms at 41% of the units, indicating that conventional care was not perceived as sufficient. It was offered in response to patient requests, in line with descriptions of CAM as patient-centered treatment. Further, respondents stated that CAM was used to reduce the need for medication on demand, or to reduce side effects from antidepressant, sedative and hypnotic pharmaceuticals. While anxiety, depression, sleep problems and withdrawal were the most commonly noted diagnoses or symptoms for which CAM was used, it is interesting and pointing toward a holistic approach that 9% of the respondents referred to use of CAM in psychiatric settings to reduce pain. Only a small share (1%) of the respondents reported that they had noted any side effects, in line with earlier studies (Freeman et al., Citation2010; Wainapel et al., Citation2015). These side effects were reportedly mild and transient. The most common reasons for interrupting the use of CAM were a lack of trained professionals and a lacking evidence-base. It is noteworthy here that when asked about the perceived evidence-base of utilized CAM methods, the most common response was that they respondent did not know. This confirms the need for further research about CAM, and for education of healthcare professionals about the benefits and risks of CAM (SOU 2019:15, Citation2019).

The complexities of CAM concepts

As expressed in responses from informants, the dividing line between CAM and conventional healthcare is not entirely clear-cut. Any definition of CAM, which assumes the complex conventional or biomedical healthcare as the oppositional referent, is time and culture dependent (de Jonge et al., Citation2018; EklöF, Citation1999). For example, chiropractic care and naprapathy are sometimes not considered as CAM, but as part of conventional care due to their now professionalized status (Hansen & Kristoffersen, Citation2016; SOU 2019:15, Citation2019). With regards to acupuncture, it might be speculated as to whether it should be considered as conventional rather than complementary medicine if given in accordance with national guidelines, if practiced by a health care professional rather than by a traditional Chinese medicine practitioner, or if given on the basis of Western rather than Chinese diagnosis and philosophy? Gale (Citation2014) notes that practices and concepts grouped under the term of CAM gathers a range of practices, products and systems that bear very little resemblance to each other, while the difference between methods used by conventional and complementary or alternative therapists may not be very marked in practice. Thus, while distinctions between conventional medicine and CAM can be quite charged and politicized (Gale, Citation2014), they may be diffuse and change over time and between locations. This can affect measures of prevalence, as well as complicate matters of regulation and integration, as well as financial conditions for practitioners and patients.

In the face of such complexities, Druss and Rosenbeck (Citation2000) argue that dividing lines between CAM and conventional medicine should give way to distinctions between effective and ineffective therapies of any kind.

Obstacles to integration of CAM in healthcare

A major argument used against CAM methods, and against their integration into conventional healthcare and tertiary education, concerns the scientific evidence of their effectiveness (SOU 2019:15, Citation2019). While some argue that CAM can and should be evaluated according to the principles of evidence based medicine (EBM) (Hoenders et al., Citation2011), others argue that such demands are unjust due to the relative lack of financial resources invested in CAM (Sarris, Citation2012), and due to a lack of evidence underpinning many practices used in conventional care (Hoenders et al., Citation2011). It is further claimed that many forms of CAM are not suitably evaluated by means of randomized controlled trials (RCTs), i.e., the gold standard of EBM and of Western biomedical notions of truth (Gale, Citation2014). For example, in trials of many CAM practices, such as acupuncture, as well as of established treatments like psychotherapy and surgery, it can be difficult to blind the recipient as to whether s/he is receiving a treatment or a placebo, while it is also impossible to blind the practitioner. Sham acupuncture, used as placebo in acupuncture trials, has also proven to not be inert (Langevin et al., Citation2011). Furthermore, many types of CAM treatments are noted to differ from the standardized protocol practices necessary for RCTs, through being highly individualized in order to suit the specific patient (Wainapel et al., Citation2015; Wan, Citation2016). For these reasons, researchers have suggested that methods other than RCTs, such as pragmatic trials (Wan, Citation2016), measures of neurochemical or other biological effects (Langevin et al., Citation2011; Wainapel et al., Citation2015), or qualitative studies (SOU 2019:15, Citation2019), should be considered in evaluations of the effects of CAM as EBM do not rest solely on RCTs. In evidence-based health care in Sweden, so called proven experience, patient requests, input from caregivers, costs and side effects are factors that should be acknowledged in decisions about which care should be offered (SFS 2010:659, Citation2010; SOU 2019:15, Citation2019).

Some healthcare practitioners in the present study noted that while knowing that the evidence base of relevant CAM methods is under question, they continue to offer them as long as patients demand it and experience subjective improvements. That is in line with guidelines for psychiatric nurses, whose task is to increase patients’ subjective sense of psychiatric well-being (Gabrielsson et al., Citation2015). Although one respondent in the present study dismissed one type of CAM as the perceived effect could be “more about nursing, providing relief for the moment”, it may be argued that as long as a CAM method is perceived to be effective and safe, it can be chosen as a nursing intervention (Landgren et al., Citation2019). While a positive attitude toward CAM has been found among Swedish nurses (Jong et al., Citation2015), participiants in this study emphasize that for implementing or maintaining CAM as a nursing intervention, support from management and medical doctors is necessary (Lindell & Ek, Citation2010).

It is worth noting that while CAM is perhaps at some odds with EMB and the principles of RCTs (e.g., Wan, Citation2016), many refer to CAM practices as individualized (Lake & Turner, Citation2017), personalized (Horrigan et al., Citation2012; Wan, Citation2016), tailored to the singular patient (Wainapel et al., Citation2015) and person-centered (Foley & Steel, Citation2017), in line with current movements toward individualized, precision or personalized, and person-centered, medicine (Khoury et al., Citation2016). Although standardized treatments do exist within CAM, Wan (Citation2016) notes that best practices are typically considered to be adaptable and individualized. Accordingly, patients and health care professionals using CAM in Swedish psychiatric care speak of CAM methods as individualized (Lindell & Ek, Citation2010), and easy to adjust to the patients’ needs and requests (Landgren et al., Citation2019). The option of offering CAM as an adjunct to conventional care entails an emphasis on shared decision-making and autonomy (di Sarsina et al., Citation2012; Foley & Steel, Citation2017), while CAM typically provides space for collaboration, verbal and/or non-verbal communication, asking reflective questions, and conveying practitioner empathy. Thus, CAM may promote patient empowerment and person-centered care (di Sarsina et al., Citation2012; Foley & Steel, Citation2017) while being conducive to development of therapeutic relationships needed to support psychiatric patients (Dziopa & Ahern, Citation2009; Gabrielsson et al., Citation2015).

Alongside the discussion about and need for sufficient research on the efficacy of many CAM methods, integration of CAM in conventional healthcare is hampered by a lack of knowledge about CAM, an absence of consensus on research priorities and clinical guidelines, limited educational efforts and actions on the part of relevant government agencies involved in the shaping of health care policy (Jong et al., Citation2015; Lake & Turner, Citation2017).

Limitations

The survey did not include questions about all forms of CAM. For example, herbal and other natural remedies were omitted from the questionnaire, as were homeopathy, chiropractic care and naprapathy. The relatively low response rate, 40%, could be due to data collection during summer. We do not know if the emails containing the survey questionnaire reached all the relevant persons, or if all recipients were relevant, particularly with regards to municipal care units. It is possible that persons either very positively or very negatively disposed toward CAM were overrepresented among the respondents. Nevertheless, while it is not possible to extrapolate conclusions about the exact extent of CAM use in Swedish psychiatric care on the basis of the present study, it does show that a significant share of existing psychiatric care units uses CAM for a variety of purposes. Further research is needed about the effects, safety, benefits, risk and costs of CAM use in psychiatric care. Against the background of our results, investigation of the reasons behind decisions of whether or not to implement CAM at psychiatric healthcare units would also be of relevance.

Conclusion

This study contributes with information about the current use of CAM in in- and outpatient psychiatric units in Sweden. Such knowledge is of importance for further discussion about and integration of safe and effective CAM practices in psychiatric care (Lindell & Ek, Citation2010), in order to meet the demand for mental health interventions in Sweden.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Adams, J. (2007). Restricting CAM consumption research: Denying insights for practice and policy. Complementary Therapies in Medicine, 15(2), 75–76. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ctim.2007.04.001

- Alderman, C. P., & Kiepfer, B. (2003). Complementary medicine use by psychiatry patients of an Australian hospital. Annals of Pharmacotherapy, 37(12), 1779–1784. https://doi.org/10.1345/aph.1C179

- Arvidsdotter, T., Marklund, B., & Taft, C. (2014). Six-month effects of integrative treatment, therapeutic acupuncture and conventional treatment in alleviating psychological distress in primary care patients–follow up from an open, pragmatic randomized controlled trial. BMC Complementary and Alternative Medicine, 14(1), 10. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6882-14-210

- Bai, L., Yan, H., Li, L., Qin, W., Chen, P., Liu, P., Gong, Q., Liu, Y., & Tian, J. &. (2010). Neural specificity of acupuncture stimulation at pericardium 6: Evidence from an fMRI study. Journal of Magnetic Resonance Imaging, 31(1), 71–77. https://doi.org/10.1002/jmri.22006

- Bergdahl, L., Berman, A. H., & Haglund, K. (2014). Patients’ experience of auricular acupuncture during protracted withdrawal. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing, 21(2), 163–169. https://doi.org/10.1111/jpm.12028

- Bjersa, K., Forsberg, A., & Fagevik Olsen, M. (2011). Perceptions of complementary therapies among Swedish registered professions in surgical care. Complementary Therapies in Clinical Practice, 17, 44–49. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ctcp.2010.05.004

- Bjerså, K., Victorin, E. S., & Olsén, M. F. (2012). Knowledge about complementary, alternative and integrative medicine (CAM) among registered health care providers in Swedish surgical care: A national survey among university hospitals. BMC Complementary and Alternative Medicine, 12, 42. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6882-12-42

- Bystritsky, A., Hovav, S., Sherbourne, C., Stein, M. B., Rose, R. D., Campbell-Sills, L., Golinelli, D., Sullivan, G., Craske, M. G., & Roy-Byrne, P. P. (2012). Use of complementary and alternative medicine in a large sample of anxiety patients. Psychosomatics, 53(3), 266–272. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psym.2011.11.009

- Cao, H., Pan, X., Li, H., & Liu, J. (2009). Acupuncture for treatment of insomnia: A systematic review of randomized controlled trials. The Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine, 15(11), 1171–1186. https://doi.org/10.1089/acm.2009.0041

- Chan, Y. Y., Lo, W. Y., Yang, S. N., Chen, Y. H., & Lin, J. G. (2015). The benefit of combined acupuncture and antidepressant medication for depression: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Affective Disorders, 176, 106–117. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2015.01.048

- Clarke, T. C., Black, L. I., Stussman, B. J., Barnes, P. M., & Nahin, R. L. (2015). Trends in the use of complementary health approaches among adults: United States, 2002–2012. National Health Statistics, 10(79), 1–16.

- Cochrane. (2019). Cochrane Complementary Medicine. http://cam.cochrane.org

- Cuijpers, P., Clignet, F., van Meijel, B., van Straten, A., Li, J., & Andersson, G. (2011). Psychological treatment of depression in inpatients: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology Review, 31(3), 353–360. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2011.01.002

- D’Onise, K., Haren, M. T., Misan, G., & McDermott, R. A. (2013). Who uses complementary and alternative therapies in regional South Australia? Evidence from the Whyalla Intergenerational Study of Health. Australian Health Review, 37(1), 104–111. https://doi.org/10.1071/AH11130

- Darbandi, S., Darbandi, M., Mokarram, P., Sadeghi, M. R., Owji, A. A., Khorram Khorshid, H. R., Zhao, B., & Heidari, M. (2016). The acupuncture-affected gene expressions and epigenetic modifications in oxidative stress–associated diseases. Medical Acupuncture, 28(1), 16–27. https://doi.org/10.1089/acu.2015.1134

- de Jonge, P., Wardenaar, K. J., Hoenders, H. R., Evans-Lacko, S., Kovess-Masfety, V., Aguilar-Gaxiola, S., Al-Hamzawi, A., Alonso, J., Andrade, L. H., Benjet, C., Bromet, E. J., Bruffaerts, R., Bunting, B., Caldas-de-Almeida, J. M., Dinolova, R. V., Florescu, S., de Girolamo, G., Gureje, O., Haro, J. M., … Thornicroft, G. (2018). Complementary and alternative medicine contacts by persons with mental disorders in 25 countries: Results from the world mental health surveys. Epidemiology and Psychiatric Sciences, 27(6), 552–567. https://doi.org/10.1017/S2045796017000774

- di Sarsina, R. P., Alivia, M., & Guadagni, P. (2012). Traditional, complementary and alternative medical systems and their contribution to personalisation, prediction and prevention in medicine-person-centred medicine. EPMA Journal, 3(1), 15. https://doi.org/10.1186/1878-5085-3-15

- Druss, B. G., & Rosenheck, R. A. (2000). Use of practitioner-based complementary therapies by persons reporting mental conditions in the United States. Archives of General Psychiatry, 57(7), 708–714. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpsyc.57.7.708

- Dziopa, F., & Ahern, K. (2009). What makes a quality therapeutic relationship in psychiatric/mental health nursing: A review of the research literature. Internet Journal of Advanced Nursing Practice, 10(1), 7.

- Eardley, S., Bishop, F. L., Prescott, P., Cardini, F., Brinkhaus, B., Santos-Rey, K., … Dragan, S. (2012). A systematic literature review of complementary and alternative medicine prevalence in EU. Complementary Medicine Research, 19(Suppl. 2), 18–28. https://doi.org/10.1159/000342708

- EklöF, M. (1999). Alternativ medicin. Forskning igår, idag, imorgon. Spri.

- Eklöf, M., & Kullberg, A. (2004). Komplementär medicin – forskning, utveckling, utbildning. Linköping Linköping University & Landstingsförbundet.

- Eklöf, M., & Tegern, G. (2001). Stockholmare och den komplementära medicinen. Stockholms läns landsting

- Ernst, E. (Ed.) (2006). The desktop guide to complementary and alternative medicine: An evidence based approach. Mosby, Hartcourt Publishers Ltd.

- Ernst, E., & Hung, S. (2011). Great expectations. What do patients using complementary and alternative medicine hope for? The Patient: Patient-Centered Outcomes Research, 4(2), 89–101.

- Fang, J., Jin, Z., Wang, Y., Li, K., Kong, J., Nixon, E. E., Zeng, Y., Ren, Y., Tong, H., Wang, Y., Wang, P., & Hui, K. K.-S. (2009). The salient characteristics of the central effects of acupuncture needling: Limbic-paralimbic-neocortical network modulation. Human Brain Mapping, 30(4), 1196–1206. https://doi.org/10.1002/hbm.20583

- Foley, H., & Steel, A. (2017). The nexus between patient-centered care and complementary medicine: Allies in the era of chronic disease?. The Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine, 23(3), 158–163. https://doi.org/10.1089/acm.2016.0386

- Frass, M., Strassl, R. P., Friehs, H., Müllner, M., Kundi, M., & Kaye, A. D. (2012). Use and acceptance of complementary and alternative medicine among the general population and medical personnel: A systematic review. Ochsner Journal, 12(1), 45–56.

- Freeman, M., Fava, M., Lake, J., Madhukar, H., Trivedi, M., Wisner, K., & Mischoulon, D. (2010). Complementary and alternative medicine in major depressive disorder: The American Psychiatric Association Task Force Report. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 71(06), 669–681. https://doi.org/10.4088/JCP.10cs05959blu

- Gabrielsson, S., Savenstedt, S., & Zingmark, K. (2015). Person-centred care: Clarifying the concept in the context of inpatient psychiatry. Scandinavian Journal of Caring Sciences, 29(3), 555–562. https://doi.org/10.1111/scs.12189

- Gale, N. (2014). The sociology of traditional, complementary and alternative medicine. Sociology Compass, 8(6), 805–822. doi. 10.1111/soc4.12182

- Goyal, M., Singh, S., Sibinga, E. M. S., Gould, N. F., Rowland-Seymour, A., Sharma, R., Berger, Z., Sleicher, D., Maron, D. D., Shihab, H. M., Ranasinghe, P. D., Linn, S., Saha, S., Bass, E. B., & Haythornthwaite, J. A. (2014). Meditation programs for psychological stress and well-being: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Internal Medicine, 174(3), 357–368. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.13018

- Grzywacz, J., Suerken, C. K., Quandt, S. A., Bell, R. A., Lang, W., & Arcury, T. A. (2006). Older adults’ use of complementary and alternative medicine for mental health: Findings from the 2002 National Health Interview Survey. The Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine, 12(5), 467–473. https://doi.org/10.1089/acm.2006.12.467

- Hansen, A. H., & Kristoffersen, A. E. (2016). The use of CAM providers and psychiatric outpatient services in people with anxiety/depression: A cross-sectional survey. BMC Complementary and Alternative Medicine, 16(1), 461. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12906-016-1446-9

- Harris, P., Cooper, K., Relton, C., & Thomas, K. (2012). Prevalence of complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) use by the general population: A systematic review and update. International Journal of Clinical Practice, 66(10), 924–939. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1742-1241.2012.02945.x

- He, W., Wang, X., Shi, H., Shang, H., Li, L., Jing, X., & Zhu, B. (2012). Auricular acupuncture and vagal regulation. Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine, 2012, 1–6. https://doi.org/10.1155/2012/78839

- Hedlund, S., & Landgren, K. (2017). Creating an opportunity to reflect: Ear acupuncture in anorexia nervosa – Inpatients’ experiences. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 38(7), 549–556. https://doi.org/10.1080/01612840.2017.1303858

- Henderson, D. C. (2008). Managing weight gain and metabolic issues in patients treated with atypical antipsychotics. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 69(2), e04. https://doi.org/10.4088/JCP.0208e04

- Herman, P. M., Poindexter, B. L., Witt, C. M., & Eisenberg, D. M. (2012). Are complementary therapies and integrative care cost-effective? A systematic review of economic evaluations. BMJ Open, 2(5), e001046. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2012-001046

- Hoenders, H. J R., Appelo, M. T., van den Brink, E. H., Hartogs, B. M. A., & de Jong, J. T. V. M. (2011). The Dutch complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) protocol: To ensure the safe and effective use of complementary and alternative medicine within Dutch mental health care. The Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine, 17(12), 1197–1201. https://doi.org/10.1089/acm.2010.0762

- Högsta Förvaltningsdomstolen. (2011). Mål nr 6634-10. http://www.hogstaforvaltningsdomstolen.se/Domstolar/regeringsratten/Avg%C3%B6randen/2011/September/6634-10.pdf

- Hornborg, A.-C. (2012). Coaching och lekmannaterapi. En modern väckelse?. Dialogos Förlag.

- Horrigan, B., Lewis, S., Abrams, D. I., & Pechura, C. (2012). Integrative medicine in America—How integrative medicine is being practiced in clinical centers across the United States. Global Advances in Health and Medicine, 1(3), 18–94. https://doi.org/10.7453/gahmj.2012.1.3.006

- Hou, P. W., Hsu, H. C., Lin, Y. W., Tang, N. Y., Cheng, C. Y., & Hsieh, C. L. (2015). The history, mechanism, and clinical application of auricular therapy in traditional Chinese medicine. Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine, 2015, 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1155/2015/495684

- Hughes, D., Ladas, E., Rooney, D., & Kelly, K. (2008). Massage therapy as a supportive care intervention for children with cancer. Oncology Nursing Forum, 35(3), 431–442. https://doi.org/10.1188/08.ONF.431-442

- Hunt, K. J., Coelho, H. F., Wider, B., Perry, R., Hung, S., Terry, R., & Ernst, E. (2010). Complementary and alternative medicine use in England: Results from a national survey. International Journal of Clinical Practice, 64(11), 1496–1502. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1742-1241.2010.02484.x

- Institute of Medicine (U.S.). (2005). Committee on the Use of Complementary and Alternative Medicine by the American Public: Complementary and alternative medicine in the United States. National Academies Press.

- Ioannidis, J. (2008). Effectiveness of antidepressants: An evidence myth constructed from a thousand randomized trials?. Philosophy, Ethics, and Humanities in Medicine, 3(1), 14. https://doi.org/10.1186/1747-5341-3-14

- Jensen, I., Lekander, M., Nord, C. E., Rane, A., & Ekenryd, C. (2007). Complementary and alternative medicine (CAM): A systematic review of intervention research in Sweden. Swedish Council for Working Life and Social Research (FAS).

- Jong, M., Lundqvist, V., & Jong, M. (2015). A cross-sectional study on Swedish licensed nurses’ use, practice, perception and knowledge about complementary and alternative medicine. Scandinavian Journal of Caring Sciences, 29(4), 642–650. https://doi.org/10.1111/scs.12192

- Kessler, R. C., Soukup, J., Davis, R. B., Foster, D. F., Wilkey, S. A., Van Rompay, M. I., & Eisenberg, D. M. (2001). The use of complementary and alternative therapies to treat anxiety and depression in the United States. American Journal of Psychiatry, 158(2), 289–294. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.158.2.289

- Khoury, M. J., Iademarco, M. F., & Riley, W. T. (2016). Precision public health for the era of precision medicine. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 50(3), 398–401. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2015.08.031

- Kilpatrick, L. A., Suyenobu, B. Y., Smith, S. R., Bueller, J. A., Goodman, T., Creswell, J. D., Tillisch, K., Mayer, E. A., & Naliboff, B. D. (2011). Impact of Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction training on intrinsic brain connectivity. NeuroImage, 56(1), 290–298. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroimage.2011.02.034

- Kondracki, N. L., Wellman, N. S., & Amundson, D. R. (2002). Content analysis: Review of methods and their applications in nutrition education. Journal of Nutrition Education and Behavior, 34(4), 224–230. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1499-4046(06)60097-3

- Lake, J., & Turner, M. S. (2017). Urgent need for improved mental health care and a more collaborative model of care. The Permanente Journal, 21, 17–024. https://doi.org/10.7812/TPP/17-024

- Lake, J. H., & Spiegel, D. (Eds.). (2006). Complementary and alternative treatments in mental health care. American Psychiatric Publishing.

- Landgren, K., Sjöström Strand, A., Ekelin, M., & Ahlström, G. (2019). Ear acupuncture in psychiatric care from the health care professionals’ perspective: A phenomenographic analysis. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 40(2), 166–175. https://doi.org/10.1080/01612840.2018.1534908

- Langevin, H. M., Wayne, P. M., MacPherson, H., Schnyer, R., Milley, R. M., Napadow, V., Lao, L., Park, J., Harris, R. E., Cohen, M., Sherman, K. J., Haramati, A., & Hammerschlag, R. (2011). Paradoxes in acupuncture research: Strategies for moving forward. Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine, 2011, 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1155/2011/180805

- Li, M., Xing, X., Yao, L., Li, X., He, W., Wang, M., Li, H., Wang, X., Xun, Y., Yan, P., Lu, Z., Zhou, B., Yang, X., & Yang, K. (2019). Acupuncture for treatment of anxiety, an overview of systematic reviews. Complementary Therapies in Medicine, 43, 247–252. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ctim.2019.02.013

- Lindberg, A., Ebbeskog, B., Karlen, P., & Oxelmark, L. (2013). Inflammatory bowel disease professionals’ attitudes to and experiences of complementary and alternative medicine. BMC Complementary and Alternative Medicine, 13(1), 349. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6882-13-349

- Lindell, L., & Ek, A. (2010). Komplementära metoder i psykiatriska verksamheter: Och brukares upplevelser och erfarenheter (FOU 2010:5). Malmö University.

- Lorenc, A., Feder, G., MacPherson, H., Little, P., Mercer, S. W., & Sharp, D. &. (2018). Scoping review of systematic reviews of complementary medicine for musculoskeletal and mental health conditions. BMJ Open, 8(10), e020222. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2017-020222

- McCormack, J., & Korownyk, C. (2018). Effectiveness of antidepressants. BMJ, 360, k1073. doi. 10.1136/bmj.k1073

- Mercante, B., Ginatempo, F., Manca, A., Melis, F., Enrico, P., & Deriu, F. (2018). Anatomo-physiologic basis for auricular stimulation. Medical Acupuncture, 30(3), 141–150. https://doi.org/10.1089/acu.2017.1254

- Mischoulon, D., & Rosenbaum, J. F. (Eds.). (2008). Natural medications for psychiatric disorders. Wolters Kluwer.

- NCCAM. (2006). What is complementary and alternative medicine (CAM)?.

- NHS (2018). Side effects - Antidepressants. https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/antidepressants/side-effects/

- Pilkington, K. (2010). Anxiety, depression and acupuncture: A review of the clinical research. Autonomic Neuroscience, 157(1-2), 91–95. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.autneu.2010.04.002

- Pilkington, K., Kirkwood, G., Rampes, H., Cummings, M., & Richardson, J. (2007). Acupuncture for anxiety and anxiety disorders – a systematic literature review. Acupuncture in Medicine, 25(1-2), 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1136/aim.25.1-2.1

- Rhee, T. G., Evans, R. L., McAlpine, D. D., & Johnson, P. J. (2017). Racial/ethnic differences in the use of complementary and alternative medicine in US adults with moderate mental distress: Results from the 2012 National Health Interview Survey. Journal of Primary Care & Community Health, 8(2), 43–54. https://doi.org/10.1177/2150131916671229

- Sarris, J. (2012). Current challenges in appraising complementary medicine evidence. Medical Journal of Australia, 196(5), 310–311. https://doi.org/10.5694/mja11.10751

- SBU (2014). Meditationsprogram mot stress vid ohälsa. https://www.sbu.se/2014_11

- SFS 2010:659. (2010). Svensk FörfattningsSamling Patientsäkerhetslagen. Socialdepartementet.

- Sirois, F. M. (2008). Motivations for consulting complementary and alternative medicine practitioners: A comparison of consumers from 1997–8 and 2005. BMC Complementary and Alternative Medicine, 8(1), 1. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6882-8-16

- Skovdahl, K., Sorlie, V., & Kihlgren, M. (2007). Tactile stimulation associated with nursing care to individuals with dementia showing aggressive or restless tendencies: An intervention study in dementia care. International Journal of Older People Nursing, 2(3), 162–170. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1748-3743.2007.00056.x

- Smith, C. A., Armour, M., Lee, M. S., Wang, L. Q., & Hay, P. J. (2018). Acupuncture for depression. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, 3. Art no: CD004046. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD004046.pub4

- Solomon, D., & Adams, J. (2015). The use of complementary and alternative medicine in adults with depressive disorders. A critical integrative review. Journal of Affective Disorders, 179, 101–113. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2015.03.031

- SOSFS 1993:18. (1993). Akupunktur. Socialstyrelsen.

- SOU 2019:15. (2019). Komplementär och alternativ medicin och vård – säkerhet, kunskap, dialog. Delbetänkande av KAM-utredningen. Stockholm: Socialdepartementet. https://www.regeringen.se/rattsliga-dokument/statens-offentliga-utredningar/2019/03/sou-201915/

- Spinks, J., & Hollingsworth, B. (2012). Policy implications of complementary and alternative medicine use in Australia: Data from the National Health Survey. The Journal of Alternative and Complementary Medicine, 18(4), 371–378. https://doi.org/10.1089/acm.2010.0817

- Suzuki, M., Tatsumi, A., Otsuka, T., Kikuchi, K., Mizuta, A., Makino, K., Kimoto, A., Fujiwara, K., Abe, T., Nakagomi, T., Hayashi, T., & Saruhara, T. (2010). Physical and psychological effects of 6-week tactile massage on elderly patients with severe dementia. American Journal of Alzheimer's Disease & Other Dementias, 25(8), 680–686. https://doi.org/10.1177/1533317510386215

- Taylor, S. (2010). Gendering in the holistic milieu: a critical realist analysis of homeopathic work. Gender, Work & Organization, 17(4), 454–474.

- Wainapel, S. F., Rand, S., Fishman, L. M., & Halstead-Kenny, J. (2015). Integrating complementary/alternative medicine into primary care: Evaluating the evidence and appropriate implementation. International Journal of General Medicine, 8, 361–372.

- Wan, L. (2016). Complementary and alternative medical treatments: Can they really be evaluated by randomized controlled trials. Acupuncture in Medicine, 34(5), 410–411. https://doi.org/10.1136/acupmed-2016-011136

- Wemrell, M., Merlo, J., Mulinari, S., & Hornborg, A.-C. (2017). Two-thirds of survey respondents in Sweden used complementary or alternative medicine (CAM) in 2015. Complementary Medicine Research, 24(5), 302–309. https://doi.org/10.1159/000464442

- Wemrell, M., Mulinari, S., Merlo, J., & Hornborg, A.-C. (2016). Användning av alternativ och komplementär medicin (AKM) i Skåne: Pilotstudie. Retrieved from

- Whiteford, H. A., Degenhardt, L., Rehm, J., Baxter, A. J., Ferrari, A. J., Erskine, H. E., Charlson, F. J., Norman, R. E., Flaxman, A. D., Johns, N., Burstein, R., Murray, C. J., & Vos, T. (2013). Global burden of disease attributable to mental and substance use disorders: Findings from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2010. The Lancet, 382(9904), 1575–1586. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61611-6

- WHO. (2013). WHO Traditional Medicine Strategy. 2014-2023. World Health Organization.

- WHO (2017). Depression: Fact sheet. www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs369/en/

- Wittchen, H. U., Jacobi, F., Rehm, J., Gustavsson, A., Svensson, M., Jönsson, B., Olesen, J., Allgulander, C., Alonso, J., Faravelli, C., Fratiglioni, L., Jennum, P., Lieb, R., Maercker, A., van Os, J., Preisig, M., Salvador-Carulla, L., Simon, R., & Steinhausen, H.-C. (2011). The size and burden of mental disorders and other disorders of the brain in Europe 2010. European Neuropsychopharmacology, 21(9), 655–679. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.euroneuro.2011.07.018

- Wu, P., Fuller, C., Liu, X., Lee, H.-C., Fan, B., Hoven, C. W., Mandell, D., Wade, C., & Kronenberg, F. (2007). Use of complementary and alternative medicine among women with depression: Results of a national survey. Psychiatric Services, 58(3), 349–356. https://doi.org/10.1176/ps.2007.58.3.349