Abstract

The need to protect the physical health of people with mental illness is increasingly acknowledged. We conducted six focus groups with 14 patients and 12 mental health care professionals to explore their individual and mutual perspectives on health promotion in daily clinical practice. Three main themes: Health as a balancing act; Dilemmas for health promotion; and Ideals and responsibility for health promotion in clinical practice were identified using thematic analysis. We discuss how aligning mutual expectations and creating an authentic dialogue based on the identification of and respect for patients’ individual resources can support health promotion in clinical psychiatry.

Introduction

Excess mortality among patients with severe mental illness (i.e. patients with a primary diagnosis of any schizophrenia spectrum disorder, affective disorder, substance abuse or personality disorder) due to medical conditions (e.g. increased body weight, hypertension, dyslipidemia and insulin resistance) constitutes a serious public health problem (Nordentoft et al., Citation2013). Evidence suggests that people with mental illness are less likely to receive standard levels of care for most medical conditions, which means that the access to and quality of health care should be improved for this group (De Hert et al., Citation2011). Awareness of the reduced life expectancy of individuals with severe mental illness and of the suboptimal care psychiatric patients receive in terms of physical health has led to the development and examination of new interventions addressing physical health concerns and unhealthy lifestyle behaviours in people with mental illness (Scott & Happell, Citation2011). Specifically, a high-quality randomised clinical trial examined the effect of one year of tailored, manual-based individual lifestyle coaching with at least one personal weekly meeting between a coach and an adult with schizophrenia spectrum disorders and abdominal obesity. The study, however, was inconclusive, and the lifestyle coaching intervention did not reduce the ten-year risk of cardiovascular disease compared with usual treatment (Speyer et al., Citation2016).

Known challenges related to change and adoption of healthy lifestyle in people with severe mental illness include low self-efficacy and a feeling of an external locus of control and disempowerment (Every-Palmer et al., Citation2018). According to Bandura (Citation2004), positive verbal persuasion by significant others (i.e. credible sources) is a key component in the support of an individual’s self-efficacy (Bandura, Citation2004). Hence, it can be argued that mental health care professionals (HCPs) are well positioned to address physical health and encourage the achievement of health behaviour goals among patients. A qualitative study indicated that patients and mental health care staff agree that poor physical shape, physical problems and suboptimal lifestyle constitute a challenge for people with mental illness (Blanner Kristiansen et al., Citation2015). Moreover, previous studies suggested that people with severe mental illness are concerned about their health and wish to receive support and/or counselling to help them adopt a healthy lifestyle (Farholm & Sørensen, Citation2016; Firth et al., Citation2016).

Support from mental health nurses is considered desirable and important for patients; this was demonstrated in a study, where the patients expressed interest in educational group sessions for physical activity and healthy eating (Lundström et al., Citation2020; Verhaeghe et al., Citation2013). One study shows, however that HCPs have difficulties integrating physical health and health promotion (Ehrlich et al., Citation2014), while another study indicates that mental health nurses are ambivalent regarding their role in physical health issues (Wynaden et al., Citation2016). However, in a recent study mental health nurses emphasised the importance of having a health promotion focus including enabling people to increase control over, and to improve, their health including supporting the extent to which patients are able to change or cope with the environment (Lundström et al., Citation2020; WHO, Citation1984). Moreover, nurses indicated that shared responsibility for health and health promotion activities should be embedded in person-centered care as well as within the working unit, and in decisions at management level (Lundström et al., Citation2020; WHO, Citation1984). Recently, The Lancet Psychiatry Commission, (i.e. an international team of researchers, clinicians, and key stakeholders), published a Blueprint for protecting physical health in people with mental illness (Firth et al., Citation2019) warning against an isolated focus on individual behaviour change and recommend integration of facilitating adaptions in service structure, delivery and culture.

Against this background, developing new insights into when and how to address health and manage health promotion in a daily psychiatric clinical practice is imperative. As a result, the overall aim of the current study was to explore the perspectives of people with serious mental illness and mental HCPs in relation to health promotion in psychiatric clinical practice.

The specific objectives were to describe the:

attitudes and experiences of patients and health care professionals, respectively, in relation to promotion of health in the context of clinical psychiatric treatment.

concerns and ideals of patients and HCPs in terms of implementing health promotion dialogue in daily clinical practice.

Material and methods

Design

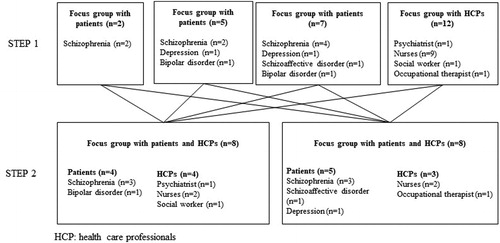

The study was designed as an exploratory qualitative focus group study and was carried out in two steps using researcher and source triangulation. The primary aim of step 1 was to explore attitudes and experiences in relation to physical health and health promotion in psychiatric clinical practice from the perspective of patients and HCPs. The aim of step 2 was to engage patients and HCPs in mutual discussions about concerns, needs and ideals related to health promotion in clinical practice. Findings are reported in accordance with consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research guidelines (Tong et al., Citation2007).

Setting

The study was carried out from May to September 2018 at three psychiatric outpatient clinics situated in different locations but grouped under the same mental health centre in the Capital Region of Denmark. The three clinics offer outpatient treatment to patients over 18 years of age with severe mental illness (i.e. any schizophrenia spectrum disorder, affective disorder, or personality disorder). The treatment is provided by a cross-disciplinary team of experienced HCPs, i.e. psychiatrists, nurses, social workers and occupational therapists. Prior consent was given by the heads of department in the respective clinics for us to implement the study and to contact the HCPs and the patients. We conducted the focus groups for step 1 in June 2018 and completed the interviews for step 2 in September 2018. Step 1 was carried out in the respective clinics, and facilities were provided for the purpose. Focus groups in step 2 were conducted at the mental health centre to which the outpatient clinics are affiliated.

Sampling and recruitment

We strategically sampled patients and HCPs from the three involved outpatient clinics. For the purpose of recruiting the HCPs, an information meeting was held for the staff at all three clinics, where a designated person was put in charge of recruiting staff members for the study who together represented as broad a possible range of experience and mirrored the wide spectrum of different professions working at the psychiatric outpatient clinics, e.g. nurses, psychiatrists, social workers and occupational therapists. To recruit patients, an information letter was sent to the three clinics requesting them, irrespective of whether they would participate, to inform patients about the opportunity to take part in the study. The aim was for the patients in the study to mirror the diversity of the present patients with respect to sex, age and diagnosis, e.g. schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, depression and bipolar disorder.

At the time of the data collection, two members of the researcher team (HS and SL, both trained female nurses) were working at the mental health centre to which the three involved outpatient clinics are affiliated. HS had a postdoc position at the centre concerned and was thus familiar with some of the employees who took part in the study and also with one or two of the patients. SL was employed as a nurse in one of the clinics and had working relationships with patients and staff from that particular clinic. HS and JM (trained female psychologist) thus conducted the interviews where SL knew the participants; neither HS nor SL was actively involved in the treatment and therapy of any of the participating patients at the time of the study.

Data collection

Data were collected by means of focus groups interviews to generate an understanding of and to provide diverse views and opinions from multiple perspectives (Brown, Citation1999). Specifically, with regard to step 2, where patients and HCP joined the same focus group, we anticipated that the group dynamic might create discussions on the similarities and differences about health and health promotion from various perspectives.

The focus groups in step 1 were conducted by HS in June 2018 and included one interview with HCPs (n = 12) and three interviews with patients (n = 2, n = 5 and n = 7). The interview with HCPs and two of the interviews with patients were moderated by HS, while SL took the role of observer. In the third interview with patients, the format was the other way around. The interviews for both step 1 and step 2 were based on a semi-structured interview guide () that included questions on perceptions of health, quality of life (patients only), roles/responsibilities (HCP only), and on motivation and barriers, as inspired by previous studies in the field. The interviews in step 1 lasted 71 to 84 minutes, or an average of 78 minutes.

Table 1. Interview guides.

The focus groups in step 2 were conducted and moderated by HS and SL in September 2018 and included two interviews with patients (n = 8) and HCPs (n = 8). JM took on the role of observer. During the interviews the moderator invited the participants to discuss questions relating to the dialogue on health, including responsibility and success criteria. The length of both interviews in step 2 was 105 minutes.

Data analysis

The focus group interviews were audiotaped and transcribed verbatim. The data from steps 1 and 2 were analysed as one unit using a codebook thematic analysis approach (Braun & Clarke, Citation2006, Citation2020). Firstly, our goal was to familiarise ourselves with the data, which we did by individually reading and re-reading the transcribed data and writing down our initial thoughts and ideas. Next, we independently coded the data by highlighting meaning units (i.e. entire paragraphs and/or sentences or single words) expressing interesting aspects in relation to the study objectives and interview schedules that served as codebooks. Subsequently, we assembled and compared our individually coded meaning units and began the process of developing themes (i.e. decontextualization). This involved sorting the meaning units into candidate themes and recursively checking the validity of these in relation to the transcripts and our initial understanding of the overall story (i.e. recontextualization). During this process themes were constantly reworked and main themes were created as a result of extensive discussion and negotiation. This process also involved the aim of saturation by increasingly diminishing variation. In practice, this meant that the analysis was not terminated until no new codes or themes emerged, and until existing themes could not be developed further (Saunders et al., Citation2018). Ultimately, the essence of each theme was refined and defined, which involved reorganising and rewriting to achieve coherent links between main themes and subthemes.

Ethics

The managers in the respective clinics consented to implementation of the study and to contact with HCPs and patients. All participants (i.e. both patients and HCPs) provided informed written consent that was signed prior to participation and received a copy to keep before commencement of the interviews. All participants were informed of their rights in terms of anonymity and the option to withdraw from the study at any time. The patients were also told that participating in the study or declining to participate would have no consequences for any current or future treatment in the mental health services. According to Danish law, no ethical approval is required from the Danish National Committee on Health Research Ethics when applying a non-experimental design.

Results

Participants

In total, 26 participants (14 patients and 12 HCPs) accepted the invitation to participate in step 1, of whom 16 (9 patients and 7 HCPs) also agreed to participate in step 2. The five HCPs who did not take part in step 2 did not do so due to vacation (n = 2) or because they were on a training course (n = 3). For patients, the reason they gave was that they lacked the energy and felt unable to take part in yet another interview. shows how the study participants were spread across focus groups.

Our analysis resulted in the development of three overriding main themes: (1) Health as a balancing act, (2) dilemmas for health promotion, and (3) Ideals and responsibility for health promotion in clinical practice). Each theme included two sub-themes (see for an overview of analytical steps and findings). Collectively, the themes capture the meaning and experience of patients and mental HCPs in relation to health promotion in psychiatric clinical practice. Described below, the themes are supported by selected quotations that are particularly illustrative.

Table 2. Overview of the analytical steps and findings.

Health as a balancing act

This theme refers to the participants’ description of health as being partly about ideal and correct behaviour (i.e. a healthy lifestyle) and as an emotional state (i.e. feeling good about yourself), where optimal health is seen as the feeling of wellbeing and satisfaction that is linked to a balance between living healthily and experiencing health.

The patients’ description of health as something concrete encompasses a perception of health based on ideal behaviour involving regular physical exercise, a healthy diet with plenty of fruit and vegetables and without excesses, good sleep and good personal hygiene. According to the patients, this ideal behaviour, however, is in competition with unhealthy, but tempting, behaviour. This is characterised by patients as the experience of losing control and give in to bad habits such as physical inactivity, smoking and excessive consumption of junk food and alcohol. They also stress loneliness and isolation as a central issue that can make it even more tempting to succumb to bad habits. According to the patients, ideal health behaviour can only be maintained for a period of time or for a few days when their mental state enables them to make healthy choices:

My day can be great, but when I enter a grocery store I begin to feel stressed, and I buy only half of what I need. This means that when I wake up the following day, I don’t have anything to eat for breakfast or lunch. Then I just eat and drink what I have in my flat, which isn’t always the healthiest option, and that’s when the bad habits take over. (Patient 3)

Somewhere between health as an ideal behaviour and the surrendering to deeply ingrained bad habits, the patients talk about making conscious choices and the satisfaction of eating pizza, drinking cola, smoking and just lounging and watching TV for hours on end. Unlike the phenomenon of giving in to bad habits, this conscious and planned choice of unhealthy options, according to the patients, is linked to the experience of health as an agreeable state:

Each time I lose 2 kg, I have to go out and get a pizza or something and reward myself because I love unhealthy food. It tastes so good and it sends certain signals to my brain, makes me feel happy. (Patient 8)

The patients explain that it is precisely this balance between choosing the appealing (unhealthy) and ideal (healthy) that is important. They emphasise that health should not become too rigid and come to mean forbidding everything that makes you feel good.

Thus, for the patients, healthiness is about experiencing harmony and a balance between the physical and the mental. The patients emphasise that what triggers the feeling of healthiness is an individual matter. Apart from the enjoyment of eating a pizza, as mentioned above, it can also be found in solving a sudoku, going for a bike ride, being out in nature or socialising. The experience of healthiness encompasses joy, fun and relaxation, irrespective of specific behaviour. The patients describe that good health can only be achieved if you have a feeling of self-confidence, self-esteem and self-acceptance:

The healthier you are, the better your wellbeing. That’s why healthy people—they needn’t be thin—have a better life. (Patient 1)

HCPs also factor in the patients’ general life situation in their definition of health. HCPs express their wish and aim to work with the person as a whole and they try to look at health from a broader perspective than the traditional approach, which primarily involves screening for indications of health behaviour such as smoking, drinking, diet and physical exercise. Some of the HCPs point out that health is also about opportunities and living conditions, in that financial, cognitive, social and mental resources are extremely important for being able to make healthy choices. The HCPs argue that the patients’ access to health is encumbered compared with people without mental illness and that this is felt to be an obstacle to tackling health issues:

The patients face so many barriers. They take medication that increases their appetite, they are tired, they have symptoms from their mental illness that decrease their level of function and their cognitive capacity, and they lack a network. This means that they face certain obstacles that make it far more difficult than for others when it comes to losing weight. (HCP 8)

Dilemmas with health promotion

This theme concerns dilemmas relating to health promotion, including the relationship between, on the one hand, the motivation to lead a healthier life and, on the other, the experience of lacking resources. Moreover, this theme include the dilemma between the efficacy and the side effects of treatment with psychopharmaceuticals, which boils down to the choice between a healthy body and a healthy mind.

The dilemma of wanting but not having the capacity to change health behaviour is a recurring theme in accounts by both the patients and the HCPs. Both groups explain and agree that the ambition and desire to live more healthily is much easier to talk about than to act on and put into practice. The patients say that they would like to lead a healthier life and that they want to, for example lose weight, start doing physical exercise and eat more healthily, but that they are impeded by various factors, such as anxiety about trying something new, not having the energy to cope with simple things or lacking the money to pursue a healthier lifestyle. One patient says, “You have to be wealthy to be healthy.” Another obstacle frequently mentioned by the patients is a perceived lack of support from family and HCPs, although this is described as secondary compared with their mental wellbeing. Some of the patients describe their mental state as being so bad at times that they fail to see any meaning in living more healthily, although this does not mean that they do not wish for change or hope to get help:

I know all about a healthy diet, I know all the facts. It’s just that I feel zero motivation. I might just as well stay at home and die a slow death. But I suppose talking about it and tossing the subject back and forth is always good. (Patient 1)

The experience of both patients and HCPs is that pharmacological treatment can enable people with mental health issues to live comfortably physically, mentally and socially, but that at the same time side effects of the treatment can cause considerable unhealthiness. The patients describe how their medication has led to enormous weight gains. One patient talks of gaining 50 kg in the 1½ years after being put on anti-psychotic drugs. Weight gain in connection with pharmacological treatment is seen by some of the patients as a choice between a healthy body and a healthy mind. One of the patients describes how she stopped her medical treatment because she had gained so much weight, which resulted in weight loss but also deterioration of her mental state:

When I was overweight and properly medicated, I felt good mentally, but there was like a little girl in my head crying because I was so fat. Then I lost weight and it was back the other way round, with my mind not working properly, but the little girl had stopped crying. (Patient 7)

The HCPs explain that they are only too aware of the problem of weight gain when the patients are put on pharmaceuticals and that the decision involves careful consideration of which medication poses the least risk of a heavy weight gain when pharmacological treatment is seen as necessary by the HCP. One HCP argues why she believes that the patient should be put on medication even when it is known that the treatment entails considerable health risks:

It’s true that there can be side effects like weight gain, but there is also the risk that if they are not given treatment, their condition will get even worse and they will become even more inactive and even more isolated, won’t get any exercise—which also leads to weight gain—and they’ll have an increasingly unhealthy diet. (HCP 9)

The issue is not simply about weight gain versus medication, but also about the fact that patients’ symptoms from their mental illness can hamper interventions and recommendations aimed at improving physical health:

I have a patient who is steered by delusions, like there’s someone dictating to him what he’s allowed to eat, so he is extremely restrictive, which means it’s hard to talk to him about it because he switches off completely and wants to talk about all sorts of other things. I think if I tried to pick at it too much, what would happen? How far could I go? (HCP 12)

The HCPs say that they are concerned about causing the patients additional problems by making too many demands in the direction of ideal health behaviour. HCPs describe the dilemma between lowering demands regarding healthy lifestyle and the possible negative consequences for health if enjoyment gets out of control. HCPs firmly believe that they have a responsibility to contribute to lowering the significant excess mortality among people with serious mental illness. Specifically, HCPs recount being aware that patients may experience significant barriers related to their illness making it especially challenging to cope with a major lifestyle change. As one HCP explains,

I believe that they (patients ed.) are both willing and able to change their habits, but I’m also very aware that their illness and negative symptoms make it more difficult at times, and that’s when I come into the picture and help them adjust their goals (HCP 5)

Ideals and responsibility for health promotion in clinical practice

This theme refers to the patients' and professionals' experience with and perspectives of ideals for cooperating and sharing the responsibility between them in relation to health promotion.

The patients would like the HCPs to try to a greater extent to have a motivational attitude and at the same time have a dialogue on equal terms and based on the patients’ experiences and present life situation. According to the patients, the HCPs should offer good expert advice tailored to the individual patient and backed up by knowledge rather than give general layperson’s advice. Altogether the patients do not want to be given answers or advice that do not fit their specific situation or individual personal experience and that come across as unreflected automatic responses.

The patients expect their dialogue with the HCP to be informal, but also want professional distance so that the HCP does not act as their friend. Thus, it is important for the patients that the HCP has an authentic and professional manner. Authenticity and professionalism have a bearing on how receptive the patients are to the good advice; at the same time the patients say that, most of all, they would like the HCPs to set in motion certain thought processes and either to confirm that the patient is on the right track or to suggest minor adjustments rather than issue specific instructions. This is communicated, for example in the dialogue between patients who talks about the value of being guided by the professionals and finding your own way—and with one manifesting psychotic symptoms (i.e. private logic), expressed in glimpses during the interview:

Patient: My contact person is my guide, and nicely tells me which way to go should I astray. And that’s the closest we get to talking about health. (Patient 13)

Reply from another patient: A guardian angel. […] I actually spent a decade studying how you can use a very energetic method to learn to balance energy, which can actually change your well-being very significantly within a very short time if something is hanging over your head. (Patient 14)

According to patients, respectful, genuine interest in their experiences, regardless of their nature, is fundamental to understanding and influencing their health. When asked about the significance of his psychotic traits in terms of health promotion, one patient stated,

You have to respect what you experience is what you experience and that there is a reason for it. And it may well be that you have grasped another aspect of reality that is not quite as relevant, but what you experience is still real. […] And if you get rid of the cause, then the psychosis disappears; that’s what’ interesting. If, on the other hand, you try all sorts of other methods, then it ends up making you sick, but it manifests itself in its own physical body. (Patient 14)

The HCPs call for ways in which they can naturally incorporate health into the dialogue so that it does not feel like a vehicle for, e.g. monitoring weight, smoking habits, physical exercise and alcohol consumption. The HCP explain that they need to proceed strategically by taking baby steps to lessen the damage caused by an unhealthy lifestyle. For the HCPs, the point of health-promoting dialogues is to motivate the patients to minimise risky conduct, such as tobacco or sugar consumption, rather than to insist on and inform them about the harmful effects of an unhealthy lifestyle. HCPs express their concern that condemning tobacco and sugar consumption, for example, can be too overwhelming for the patients, possibly ruining the therapeutic relationship. However, they also point out that they are obliged to monitor the patients’ health during consultations by asking them about weight, smoking, alcohol and physical exercise, which they feel represents a clear (albeit inappropriate) risk-based perspective. The HCPs explain it thus:

At one point I too got the impression that I was supposed to hold these KRAM consultations [consultations specifically about diet, tobacco, alcohol and substance abuse] more for the sake of the system than anything else; you felt as though you were having a go at the patient. And then I started approaching it as a way of limiting the damage, like getting them to go down from 30 to 20 cigarettes a day and accepting that as fine. On the other hand, we shouldn’t be too undemanding because it’s true that they die earlier than the rest of us. But if we carry on with a rigid, programmatic approach, there is a risk of shutting down all communication lines. (HCP 12)

HCPs recount that they would like to be able to approach the issue not just from the angle of identifying problems and deficits, but more from the angle of using the patients’ resources as a starting point. However, they are often in doubt as to when this approach is successful, as it can be hard to measure or find out what is actually effective in the case of a successful outcome:

I am quite often surprised about what my patients are capable of when they come back. I don’t necessarily think it’s something that happened during the consultation. But they come back two weeks later and talk about “since then,” and I’m astonished. It’s hard to analyse what actually works. (HCP 10)

Patients and staff alike refer to both individual and shared responsibility for maintaining and furthering the patients’ physical health. Patients and HCPs agree that the dialogue on health should depend on the situation. The patients explain that it would help if the HCPs came across as less cautious than they are, according to the patients, at present. In this respect the HCPs stress that their cautious approach is due to the fact that they wish first of all to build up a trusting relationship with the patient, and when they have done that, the most important thing is to keep that trust. In this regard, the patients recount that what they would like is clear messages and to have responsibility for their health. For example, as one of the participants explained, he alone was responsible for when he could cope with dealing with the issue of his state of health, and his health was ultimately a question of his own choice. The patients express the need to set goals for the future, preferably together with the HCPs, as long as the decision lies with them:

I feel calm when I make decisions by myself. Harmony can lead you to choose to live healthily. (Patient 12)

The HCPs say that their ambition is to make the issue of physical health a natural part of the dialogue-based conversation. The HCPs also feel that it is a responsibility and an obligation, reasoning that they are trained to both cure and prevent negative consequences of mental illness, if possible. However, they acknowledge that successfully promoting behaviour change is a long-term process that requires patience and multiple attempts.

Discussion

In this study we aimed to offer new insights into the perspectives of people with serious mental illness and mental health care professionals on health and health promotion in the context of clinical psychiatry. We found that patients and HCPs share concerns and ideals for implementation of health promotion in daily clinical practice, including taking into account the individual patient’s situation and resources. Notably, the patients said that they wanted and expected a dialogue on equal terms with the HCPs. Similar perspectives and findings are described in other studies, e.g. in a study among long-term psychiatric patients with weight gain where participants valued and addressed the importance of being met as an expert on their own experiences, being asked about preferences and goals, and partnering with HCPs to develop new solutions, remove unidentified barriers and improve motivation (Every-Palmer et al., Citation2018). However, both groups in our study felt that establishing a balanced and equal dialogue in clinics is a challenge. The patients expect the HCPs to enter into a dialogue with an authentic attitude and take as their starting point (and pivotal point) the patient’s own health-related wishes and goals. Furthermore, the patients in this study also express the wish to be and remain responsible for their own health and for the HCPs to focus on previous successful experiences. The latter is described in previous studies, such as Lundstrom et al., who describe lived experiences of lifestyle changes in persons with severe mental illness, where the participants said that they want the professionals to pay attention to the individual’s reasons for making changes and to get them to use the experiences of previous attempts, and that the support should focus on strengthening the person’s self-efficacy and self-confidence (Lundstrom et al., Citation2017).

Importantly, the HCPs in this study experience the difficulty of finding a balance between encouraging ideal/optimal health behaviour while at the same time showing respect and understanding for the patient’s experience of enjoyment of food and/or sedentary activity, which is regarded as unhealthy from a biomedical perspective. Here, the HCPs find themselves caught in a dilemma between, on the one hand, the biomedical-based responsibility for preventing excess mortality, and on the other, respecting and supporting the patients’ own wishes, dreams and hopes.

This balance is central to a clinical model for general practice described by Hollnagel and Malterud (Citation1995), who assert that it is possible and recommendable to balance resources and risks and parallel agendas in the encounter between doctor and patient. This is achieved by continually focussing on objective matters, risks and disease factors while integrating and using the patients’ subjective matters with their illness experiences and specific resources in the dialogue (Hollnagel & Malterud, Citation1995). While a corresponding clinical model for psychiatric practice, to our knowledge, has not been developed, the salutogenic idea behind Hollnagel and Malterud’s model is in alignment with the findings of both the current and previous studies pointing to the wish of people with severe mental illness that HCPs should focus on patients’ hopes, goals and dreams. Collectively, this supports the notion that health promotion applies an anti-stigma approach and suggests that people with severe mental illness should have a choice and that the choice should be respected (Ehrlich et al., Citation2015). This is furthermore supported by findings from a previous study, where users of mental health services stated that nurses would benefit from being aware of their understanding of physical health and should give this awareness greater weight than biomedical measures regarding physical health, adding that health is always interconnected with wellbeing and mental health (Happell et al., Citation2016). Of importance, this suggest that the principles behind the concept of health proposed by the World Health Organisation emphasising social and personal resources in the context of people’s everyday life should be acknowledged in efforts to promote health in clinical psychiatric practice (WHO, Citation1984).

As such, it may be argued that efforts to promote and/or implement health promotion in psychiatric clinical practice must adopt a salutogenic approach, which has been proposed as a framework for viewing people as experts on themselves and their unique situations and experiences, including their pain, suffering and concerns. Moreover, applying a salutogenic approach requires and allows identification and promotion of individual resources. This notion is supported by the findings of previous qualitative research suggest that everyday structure is important for patients with severe mental illness in order to enable healthy living in addition to being regarded as a whole person by self and others (Blomqvist et al., Citation2018). Consequently, mental HCP function more as a dialogue partner who balances between listening empathetically to participants’ difficulties and taking into account their strengths and resources (Langeland & Vinje, Citation2017). Further research into the development and evaluation of health promotion dialogue tools and activities inspired by a salutogenic approach appear warranted. In this regard, recent development and implementation of a mental health promotion initiative in Denmark applying a salutogenic oriented conceptual framework focussing on strengthening and promoting resources and protective factors, emphasised the importance of building capacity (including providing staff training) and campaign activities to promote awareness and knowledge (Hinrichsen et al., Citation2020). While the study was not related to promotion of health behaviour change per se, the study holds great promise and inspiration for advancing and promoting a resource oriented practice in the context of mental health care including fostering intersectoral and interprofessional collaborations and patient-professional co-creation (Hinrichsen et al., Citation2020).

Overcoming the dilemma between prioritisation of the biomedical perspective and the patients’ own dreams and hopes in the dialogue between the professional and the patient does seem, however, to be contingent on simultaneously focussing on generally giving more attention to the importance of protecting the patients’ physical health in clinical practice. For example, other studies show that the ability of the health care system to integrate physical health into mental health services faces many barriers, e.g. workplace culture, difficulties with implementing new guidelines and uncertainties about what responsibilities HCPs have (Ehrlich et al., Citation2014; Wynaden et al., Citation2016). A study on the actions of health care professionals and their responsibilities in terms of managing physical health issues among people with severe mental illness emphasised barriers such as workplace culture and concluded that HCPs must be aware of latent discriminatory attitudes towards people with mental illness and reflect on these attitudes to manage physical health issues despite previous, unsuccessful attempts (Lerbaek et al., Citation2019). Firth et al. (Citation2019) came to a similar conclusion in their recently published blueprint for protecting physical health in people with mental illness, which also proposed training physiotherapists and exercise physiologists in psychopathology who have the opportunity to promote health in clinical practice can be supplemented with options involving customised training and community-based health promotion (Firth et al., Citation2019; Rosenbaum et al., Citation2018). An important task of future research is to smooth transitions between sectors and their cross-disciplinary collaboration.

Some methodological strengths and weaknesses need to be taken into consideration in the evaluation of the validity of the results of the current study. The credibility of the research process and its findings was supported by use of experienced interviewers, one highly experienced researcher (JM), an experienced nurse researcher (HS) and an experienced mental health nurse (SL). The combined experience and expertise among the involved researchers supported the creation of an environment that allowed participants to share their experiences and opinions.

One limitation of the study is that not all the participants in step 1 took part in step 2. The patients and HCPs who participated in both parts were all interested in physical health, possibly colouring the discussions, which might have been different if the participants had been patients and staff who were not as committed to health. One strongpoint was that we succeeded in getting patients to participate who expressly had psychotic thoughts and symptoms. They contributed significant data to the analysis, indicating that it is both possible and suitable to involve patients with manifest psychotic symptoms in conversations on health, including patients with a mindset permeated by a private logic.

The findings from this study involving both people with mental illness and HCPs indicate that inviting and facilitating opportunities for co-creation of new tools and frameworks for the dialogue on health and health promotion possibly has potential.

This study indicates that talking about and dealing with health promotion is seen as relevant and meaningful by both patients and HCPs, albeit associated with significant dilemmas and trade-offs, not to mention a certain complexity, including differing perceptions of responsibility and approach. Aligning mutual expectations and creating an expert, authentic dialogue based on individual resources between patient and professional seems to be essential for health promotion in clinical practice. The findings of this study also indicate that health promotion cannot or should not be reduced to a matter of refraining from an unhealthy lifestyle and/or changing one’s way of life; on the contrary, health promotion must integrate and stimulate emotions that include conscious indulging, satisfaction, reassurance and calm, irrespective of concrete behaviour.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all of the participants in our study as well as the departmental managers who made this study possible and aided in recruitment. We would also like to thank Stine Schnor-Olsen for helping with the transcriptions.

Disclosure statement

This study was conducted without external funding. The authors report no conflict of interest.

Availability of data and materials

Due to privacy protection issues and according to Danish legislation, the datasets supporting the conclusions of this article are available only to the researchers involved in the project.

References

- Bandura, A. (2004). Health promotion by social cognitive means. Health Education & Behavior, 31(2), 143–164. https://doi.org/10.1177/1090198104263660

- Blanner Kristiansen, C., Juel, A., Vinther Hansen, M., Hansen, A. M., Kilian, R., & Hjorth, P. (2015). Promoting physical health in severe mental illness: Patient and staff perspective. Acta Psychiatrica Scandinavica, 132(6), 470–478. https://doi.org/10.1111/acps.12520

- Blomqvist, M., Sandgren, A., Carlsson, I. M., & Jormfeldt, H. (2018). Enabling healthy living: Experiences of people with severe mental illness in psychiatric outpatient services. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing, 27(1), 236–246. https://doi.org/10.1111/inm.12313

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2020). One size fits all? What counts as quality practice in (reflexive) thematic analysis? Qualitative Research in Psychology, 1–25. https://doi.org/10.1080/14780887.2020.1769238

- Brown, J. B. (1999). The use of focus groups in clinial research. In B. Crabtree & W. Miller (Eds.), Doing qualitative research (2nd ed., pp. 109–124). Sage Publications Inc.

- DE Hert, M., Correll, C. U., Bobes, J., Cetkovich-Bakmas, M., Cohen, D., Asai, I., Detraux, J., Gautam, S., Möller, H. J., Ndetei, D. M., Newcomer, J. W., Uwakwe, R., & Leucht, S. (2011). Physical illness in patients with severe mental disorders. I. Prevalence, impact of medications and disparities in health care. World Psychiatry, 10(1), 52–77. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.2051-5545.2011.tb00014.x

- Ehrlich, C., Kendall, E., Frey, N., Denton, M., & Kisely, S. (2015). Consensus building to improve the physical health of people with severe mental illness: A qualitative outcome mapping study. BMC Health Services Research, 15, 83. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-015-0744-0

- Ehrlich, C., Kendall, E., Frey, N., Kisely, S., Crowe, E., & Crompton, D. (2014). Improving the physical health of people with severe mental illness: Boundaries of care provision. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing, 23(3), 243–251. https://doi.org/10.1111/inm.12050

- Every-Palmer, S., Huthwaite, M. A., Elmslie, J. L., Grant, E., & Romans, S. E. (2018). Long-term psychiatric inpatients' perspectives on weight gain, body satisfaction, diet and physical activity: A mixed methods study. BMC Psychiatry, 18(1), 300. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-018-1878-5

- Farholm, A., & Sørensen, M. (2016). Motivation for physical activity and exercise in severe mental illness: A systematic review of intervention studies. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing, 25(3), 194–205. https://doi.org/10.1111/inm.12214

- Firth, J., Rosenbaum, S., Stubbs, B., Gorczynski, P., Yung, A. R., & Vancampfort, D. (2016). Motivating factors and barriers towards exercise in severe mental illness: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychological Medicine, 46(14), 2869–2881. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291716001732

- Firth, J., Siddiqi, N., Koyanagi, A., Siskind, D., Rosenbaum, S., Galletly, C., Allan, S., Caneo, C., Carney, R., Carvalho, A. F., Chatterton, M. L., Correll, C. U., Curtis, J., Gaughran, F., Heald, A., Hoare, E., Jackson, S. E., Kisely, S., Lovell, K., Maj, M., McGorry, P. D., Mihalopoulos, C, Myles, H., O’Donoghue, B., … Stubbs, B. (2019). The Lancet Psychiatry Commission: A blueprint for protecting physical health in people with mental illness. Lancet Psychiatry, 6(8), 675–712. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2215-0366(19)30132-4

- Happell, B., Ewart, S. B., Platania-Phung, C., Bocking, J., Scholz, B., & Stanton, R. (2016). What physical health means to me: Perspectives of people with mental illness. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 37(12), 934–941. https://doi.org/10.1080/01612840.2016.1226999

- Hinrichsen, C., Koushede, V. J., Madsen, K. R., Nielsen, L., Ahlmark, N. G., Santini, Z. I., & Meilstrup, C. (2020). Implementing mental health promotion initiatives-process evaluation of the ABCs of mental health in Denmark. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(16), 5819. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17165819

- Hollnagel, H., & Malterud, K. (1995). Shifting attention from objective risk factors to patients’ self-assessed health resources: A clinical model for general practice. Family Practice, 12(4), 423–429.

- Langeland, E., & Vinje, H. F. (2017). The application of salutogenesis in mental healthcare settings. In M. B. Mittelmark, S. Sagy, M. Eriksson, G. F. Bauer, J. M. Pelikan, B. Lindström, & G. A. Espnes (Eds.), The handbook of salutogenesis (pp. 299–305). Springer.

- Lerbaek, B., Jorgensen, R., Aagaard, J., Nordgaard, J., & Buus, N. (2019). Mental health care professionals' accounts of actions and responsibilities related to managing physical health among people with severe mental illness. Archives of Psychiatric Nursing, 33(2), 174–181. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apnu.2018.11.006

- Lundstrom, S., Ahlstrom, B. H., Jormfeldt, H., Eriksson, H., & Skarsater, I. (2017). The meaning of the lived experience of lifestyle changes for people with severe mental illness. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 38(9), 717–725. https://doi.org/10.1080/01612840.2017.1330909

- Lundström, S., Jormfeldt, H., Hedman Ahlström, B., & Skärsäter, I. (2020). Mental health nurses' experience of physical health care and health promotion initiatives for people with severe mental illness. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing, 29(2), 244–253. https://doi.org/10.1111/inm.12669

- Nordentoft, M., Wahlbeck, K., Hallgren, J., Westman, J., Osby, U., Alinaghizadeh, H., Gissler, M., Laursen, T. M. (2013). Excess mortality, causes of death and life expectancy in 270,770 patients with recent onset of mental disorders in Denmark, Finland and Sweden. PLOS One, 8(1), e55176. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0055176

- Rosenbaum, S., Hobson-Powell, A., Davison, K., Stanton, R., Craft, L. L., Duncan, M., Elliot, C., Ward, P. B. (2018). The role of sport, exercise, and physical activity in closing the life expectancy gap for people with mental illness: An international consensus statement by Exercise and Sports Science Australia, American College of Sports Medicine, British Association of Sport and Exercise Science, and Sport and Exercise Science New Zealand. Translational Journal of the American College of Sports Medicine, 3(10), 72–73. https://doi.org/10.1249/tjx.0000000000000061

- Saunders, B., Sim, J., Kingstone, T., Baker, S., Waterfield, J., Bartlam, B., Burroughs, H., & Jinks, C. (2018). Saturation in qualitative research: Exploring its conceptualization and operationalization. Quality & Quantity, 52(4), 1893–1907. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11135-017-0574-8

- Scott, D., & Happell, B. (2011). The high prevalence of poor physical health and unhealthy lifestyle behaviours in individuals with severe mental illness. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 32(9), 589–597. https://doi.org/10.3109/01612840.2011.569846

- Speyer, H., Christian Brix Norgaard, H., Birk, M., Karlsen, M., Storch Jakobsen, A., Pedersen, K., Hjorthøj, C., Pisinger, C., Gluud, C., Mors, O., Krogh, J., Nordentoft, M. (2016). The CHANGE trial: No superiority of lifestyle coaching plus care coordination plus treatment as usual compared to treatment as usual alone in reducing risk of cardiovascular disease in adults with schizophrenia spectrum disorders and abdominal obesity. World Psychiatry, 15(2), 155–165. https://doi.org/10.1002/wps.20318

- Tong, A., Sainsbury, P., & Craig, J. (2007). Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): A 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. International Journal for Quality in Health Care, 19(6), 349–357. https://doi.org/10.1093/intqhc/mzm042

- Verhaeghe, N., De Maeseneer, J., Maes, L., Van Heeringen, C., & Annemans, L. (2013). Health promotion in mental health care: Perceptions from patients and mental health nurses. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 22(11-12), 1569–1578. https://doi.org/10.1111/jocn.12076

- WHO. (1984). Health promotion: A discussion document on the concept and principles: Summary report of the Working Group on Concept and Principles of Health Promotion, Copenhagen, 9-13 July 1984. Copenhagen: WHO Regional Office for Europe.

- Wynaden, D., Heslop, B., Heslop, K., Barr, L., Lim, E., Chee, G. L., Porter, J., Murdock, J. (2016). The chasm of care: Where does the mental health nursing responsibility lie for the physical health care of people with severe mental illness? International Journal of Mental Health Nursing, 25(6), 516–525. https://doi.org/10.1111/inm.12242