Abstract

Background:

Self-harm is defined as intentional self-injury without the wish to die. People who self-harm report feeling poorly treated by healthcare professionals, and nurses wish to know how best to respond to and care for them. Increased understanding of the meaning of self-harm can help nurses collaborate with young people who self-harm to achieve positive healthcare outcomes for them.

Aim:

This review aimed to synthesise qualitative research on young peoples’ experiences of living with self-harm.

Method:

A literature search in CINAHL, PubMed, and PsycINFO resulted in the inclusion of 10 qualitative articles that were subjected to metasynthesis.

Results:

The results show that young people’s experiences of living with self-harm are multifaceted and felt to be a necessary pain. They used self-harm to make life manageable, reporting it provided relief, security, and a way to control overwhelming feelings. They suffered from feeling addicted to self-harm and from shame, guilt, and self-punishment. They felt alienated, lonely, and judged by people around them, from whom they tried to hide their real feelings. Instead of words, they used their wounds and scars as a cry for help.

Conclusion:

Young people who harm themselves view self-harm as a necessary pain; they suffer, but rarely get the help they need. Further research is necessary to learn how to offer these people the help they need.

Background

Self-harm has been reported in the medical literature since the 19th century (Angelotta, Citation2015; Skårderud, Citation2008), and can be defined as intentional self-inflicted injury towards one’s body without suicidal intent. This align with the widely used non-suicidal self-injury (NSSI) definition defining NSSI as self-inflicted destruction of body tissue without suicidal intent and for purposes not socially sanctioned (International Society for the Study of Self-injury, Citation2018). According to the International Society for the Study of Self Injury (ISSS, Citation2016), 6% to 8% of adolescents and young adults report more self-harming behaviour than the general population. These numbers, however, may be low because people who deliberately hurt themselves often avoid seeking medical help because of their shame and guilt (Hicks & Hinck, Citation2008; Long et al., Citation2013). Life-time prevalence of self-harm among adolescents around the world is reported to range from 16% to 18% (Landstedt & Gilander, Citation2011; Muehlenkamp et al., Citation2012). Among Danish adolescents, the prevalence is about 21% (Møhl & Skandsen, Citation2012). In a study by Klonsky (Citation2011), self-harm was reported to be 18.9% among people up to 30 years of age.

Self-harming behaviours often debut between the ages of 12 and 14 and are more common in adolescents and young adults than among older people (Klonsky, Citation2011; Nock & Prinstein, Citation2004). Some researchers report that self-harm is more common among women than men (Arkins et al., Citation2013; Straiton et al., Citation2013), but other studies indicate it is equally common in both sexes (Klonsky, Citation2011; Lloyd-Richardson et al., Citation2007; Nock & Prinstein, Citation2004). Victor et al. (Citation2018) report that men and women share similar non-suicidal self-injury (NSSI) characteristics and treatment outcomes, although men reported lower severity of most NSSI correlates (e.g., suicidality, psychopathology). Bjärehed (Citation2012) argued that most research on NSSI had focussed on girls and cautioned that conclusions from such research might be mistakenly generalised to explain boys’ self-harm.

Although self-harming is not a separate diagnosis in the DSM-5 (American Psychiatric Association [APA], Citation2013), but rather a behaviour/symptom, it can be related to mental ill-health and increased risk of death. Commonly, self-harm is associated with mental disorders such as depression, anxiety, drug addiction, eating disorders, post-traumatic stress disorder, autism, bipolar syndrome, psychosis, and borderline personality disorder (Hawton et al., Citation2012; Victor et al., Citation2018). In health care, self-harm is identified through conversations with the person who self-harm or by observations. Nurses in general report that having knowledge about the functioning of self-harm and by that being prepared when meeting people who self-harm is important in nursing and helps when interacting with them. More knowledge is needed to improve understanding of the function of self-harm for the individual in order to develop a range of skills to offer the best possible care and aid in prevention and harm-reduction (Lindgren et al., Citation2018; McGough et al., Citation2021; Morrissey et al., Citation2018; Rissanen et al., Citation2012; Shaw & Sandy, Citation2016). Understanding the meaning of self-harm can help nurses collaborate with people who self-harm to achieve positive healthcare outcomes (Doyle et al., Citation2017). However, people who self-harm often describe negative experiences of healthcare, and several studies report that people who self-harm describe feeling powerless in care and misunderstood by healthcare professionals (Eriksson & Åkerman, Citation2012; Lindgren et al., Citation2018; Looi et al., Citation2015).

Aim

This study aimed to synthesise qualitative research on young peoples’ experiences of living with self-harm.

Method

This metasynthesis of qualitative studies of self-harm among young people uses the approach outlined by Sandelowski and Barroso (Citation2007). In this study we defined ‘young people’ as adolescents and young adults aged 12 to 25 years of age and NSSI as ‘the deliberate destruction of one’s own bodily tissue in the absence of suicidal intent and for reasons not socially sanctioned’ (APA, Citation2013; ISSS, Citation2018).

Literature search

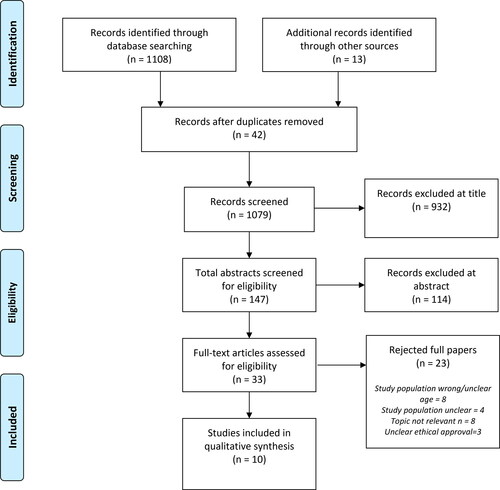

The following databases were searched: PubMed, PsycINFO, and CINAHL using CINAHL, MeSH headings and Thesaurus of Psychological Index term words. The search terms were used in combination and included ‘self-mutilation’, ‘self-harm’, ‘self-injurious behaviour’, ‘self-injury’, ‘self-destructive behaviour’, ‘self-inflicted injury’, ‘experience’, ‘experiences’, ‘attitude’, ‘adolescents’, ‘young adults’, ‘coping’ and ‘qualitative’, and the booelska operators (OR, AND) were used to narrow or expand the search. Furthermore, a manual secondary search in identified papers reference lists were added to the electronic search. The total search strategy identified 1,121 references. We removed 42 duplicates, and 1,079 unique records remained. Search limitations were peer-reviewed articles written in the English language and published between 2006 and 2019. The articles included in the final analysis were selected using the following inclusion criteria: adolescents and young people between 12 and 25 years, empirical studies meeting the NSSI definition, relevance to the aim of the literature study, qualitative methodology, good scientific quality, and ethically approved. Literature reviews, dissertations, grey literature, and articles reporting experiences of suicide or suicide attempts were excluded.

Inclusion and exclusion

The selection process was carried out stepwise in line with strategies by Polit and Beck (Citation2013). First, selecting articles with relevant titles, and second, reading the abstracts of these articles. Articles containing abstracts that suited the purpose of our literature study were selected for further reading. The third step was to read in full these articles and assess them for overall quality (Polit & Beck, Citation2013). A summary of the selection process is presented in .

We read and assessed 33 qualitative articles and excluded 23: eight because of wrong study population/unclear age, four because of unclear study population, eight because the topic was not relevant, and three because ethical approval was unclear. The remaining 10 articles were included in this review ().

Table 1. Overview of articles included in the literature review.

Data analysis

The analysis process involved extracting, aggregating, interpreting, and synthesising the findings in the included studies in line with the strategies described by Sandelowski and Barroso (Citation2007). First, we read these studies to obtain an overall picture of the experiences related to young peoples’ experiences of living with self-harm as described in the findings of the studies. We then extracted the text answering the aim of the study. The extracted texts were then aggregated, abstracted, interpreted and synthesised into sub-categories, categories, and major theme (Sandelowski & Barroso, Citation2003). The process was iterative, moving back and forth from one paper to the next and back again to confirm or disconfirm a finding. During the whole analysis process, the authors discussed the interpretations until consensus was obtained.

Ethical considerations

As this was a secondary synthesis of data, ethical approvals were not required. Our ethical responsibility included selecting articles that had received ethical approval and were compliant with good research ethics.

Findings

In the original papers, the total number of participants was 154 young people, 118 females, 6 males, and for 30 of those participants no sex were reported. Participants were between 12 and 23 years of age, and the studies were conducted in Finland, Malaysia, South Africa, United Kingdom, and USA. The analysis resulted in four categories and 11 sub-categories ().

Table 2. Overview of sub-categories, categories, and theme revealed in the analysis.

Overall, the results show that young people experience self-harm as multifaceted and as a necessary pain. They harm themselves to cope and make life more manageable. Self-harming behaviour is perceived by many as suffering and alienation as well as a way of communicating with other people.

Coping

Young people describe that self-harming behaviour has a function in their lives. The behaviour helps them to cope with overwhelming emotions and provides an opportunity to experience control. The self-harming behaviour also provides relief and security, at least for a while.

Control

Young people who self-harm may feel that they have low control over their life, but by harming themselves, they can maintain a certain amount of control over something. They can take control over the pain caused by their emotions by harming themselves and instead focussing on the physical pain and the actual injuries (Bheamadu et al., Citation2012; Hill & Dallos, Citation2012; Kokaliari & Berzoff, Citation2008; Lesniak, Citation2010; Moyer & Nelson, Citation2007; Rissanen et al., Citation2008; Tan et al., Citation2019; Tillman et al., Citation2018). Using self-harm in this way can also be a way to take control over internal factors such as thoughts, feelings and external factors related to the environment and the family (Bheamadu et al., Citation2012; Hill & Dallos, Citation2012; Tan et al., Citation2019). Some young people who hurt themselves feel high demands and expectation from their family and others to be independent, ‘perfect’, and self-sufficient (Kokaliari & Berzoff, Citation2008; Lesniak, Citation2010; Moyer & Nelson, Citation2007; Tan et al., Citation2019). They also feel pressured by society to be successful and believe that harming themselves makes it easier for them to control themselves in order to live up to these high expectations (Kokaliari & Berzoff, Citation2008).

Relief and security

The results show that young people sometimes harm themselves in order to feel better and they often experience immediate relief of their emotional pain. They feel secure in the knowledge that self-harm can make them feel better (Klineberg et al., Citation2013; Kokaliari & Berzoff, Citation2008; Lesniak, Citation2010; McAndrew & Warne, Citation2014; Moyer & Nelson, Citation2007; Tan et al., Citation2019; Tillman et al., Citation2018). After the self-harm episode, young people express that they can feel more alive (Bheamadu et al., Citation2012; Lesniak, Citation2010; Rissanen et al., Citation2008), relieved, and relaxed (Lesniak, Citation2010; Tan et al., Citation2019). In that way self-harming behaviour seems to make their lives easier, for example, it can help falling asleep at night (Lesniak, Citation2010; Moyer & Nelson, Citation2007; Tan et al., Citation2019), and getting through difficult periods in life (Hill & Dallos, Citation2012). Some young people feel that by hurting themselves, they can release negative thoughts, and ‘empty’ their heads. For some, self-harming behaviour becomes a way to temporarily escape from exhausting feelings (Moyer & Nelson, Citation2007; Tillman et al., Citation2018). Furthermore, that they have no choice but to harm themselves, and that it is necessary to do so in order to survive (Hill & Dallos, Citation2012; Lesniak, Citation2010; McAndrew & Warne, Citation2014; Moyer & Nelson, Citation2007; Rissanen et al., Citation2008).

Overwhelming feelings

Self-harming behaviour is described as a way of dealing with repressed emotions (Lesniak, Citation2010; Moyer & Nelson, Citation2007; Tan et al., Citation2019; Tillman et al., Citation2018) and a strategy to block out emotions that may feel overwhelming (Moyer & Nelson, Citation2007; Tan et al., Citation2019; Tillman et al., Citation2018) such as anger, frustration, and anxiety (Bheamadu et al., Citation2012; Lesniak, Citation2010; Moyer & Nelson, Citation2007; Tillman et al., Citation2018). Some young people describe self-harming when they are troubled by anxiety about problems, feelings of hopelessness (Lesniak, Citation2010), and negative thoughts (Hill & Dallos, Citation2012; Moyer & Nelson, Citation2007; Tan et al., Citation2019). Young people seem to use self-harming behaviour to help them get through and deal with difficult periods in their lives (Hill & Dallos, Citation2012; Moyer & Nelson, Citation2007).

Suffering

Young people who self-harm sometimes describe the behaviour as dysfunctional. It can be a self-punishment or an addiction for the persons to harm them self and often it is about shame and guilt.

Self-punishment

Self-harming behaviour is described by young people as a type of self-punishment where the person is frustrated, disgusted and angry with oneself and feels they deserves to be punished (Hill & Dallos, Citation2012; Lesniak, Citation2010; Rissanen et al., Citation2008; Tan et al., Citation2019; Tillman et al., Citation2018). Self-harming behaviour as self-punishment is often described in the same context as anger (Bheamadu et al., Citation2012; Hill & Dallos, Citation2012; Klineberg et al., Citation2013; Lesniak, Citation2010; Moyer & Nelson, Citation2007; Rissanen et al., Citation2008), where anger often is directed inward, as either self-punishment or a way to deal with anger and preventing spreading it to others. It can be about sacrificing one’s own well-being rather than harming someone else with one’s anger (Hill & Dallos, Citation2012; Moyer & Nelson, Citation2007). The term self-hatred is sometimes used when young people describe themselves and why they hurt themselves (Lesniak, Citation2010; Tan et al., Citation2019; Tillman et al., Citation2018).

Addiction

The strong need to self-harm (Rissanen et al., Citation2008; Tan et al., Citation2019) is described as a desire or as an addiction (Moyer & Nelson, Citation2007; Tillman et al., Citation2018), both mentally (Bheamadu et al., Citation2012) and physically (Lesniak, Citation2010). The self-harming behaviour is described as escalating (Lesniak, Citation2010) and that the need to self-harm becomes so obvious that the person uses tools that are closest at hand (Rissanen et al., Citation2008; Tan et al., Citation2019). The results show that despite pressure from people around them to stop self-harm (Moyer & Nelson, Citation2007), and despite that the person who self-harms have a desire to stop, this is not easy (Klineberg et al., Citation2013) and there is doubt about whether it is possible (Lesniak, Citation2010). Young people describe the need to self-harm as strong, and what others think and feel about them does not constitute an obstacle to self-harm (McAndrew & Warne, Citation2014).

Shame and guilt

The metasynthesis reveal that self-harming behaviour is about shame and guilt. These feelings can be about shame over both the body and the behaviour (Lesniak, Citation2010; McAndrew & Warne, Citation2014; Tan et al., Citation2019) but also about guilt for emotionally hurting someone else with their behaviour (Moyer & Nelson, Citation2007; Tillman et al., Citation2018). It is common for the person who self-harm to experience a feeling of remorse that they have injured themselves (Klineberg et al., Citation2013; Moyer & Nelson, Citation2007; Tan et al., Citation2019).

Alienation

Young people who self-harm experience alienation connected to loneliness when being met by an incomprehensible and judgemental environment. Further, to them keeping the self-harming behaviour to themselves and doing everything they can to hide it.

Loneliness

Being young and living with self-harming behaviour includes feeling lonely and isolated, and a feeling of never fitting in (Bheamadu et al., Citation2012; Lesniak, Citation2010). At the same time, there is a desire to be loved and accepted, to have someone who listens. Instead of support from peers and family, self-harming behaviour works as the only friend, an ally who is always waiting, always there (Lesniak, Citation2010). These young people have difficulty with friendships and they feel that they have no one to turn nor talk to (Lesniak, Citation2010; Moyer & Nelson, Citation2007). They feel abandoned and cut off from their surroundings and experience that those around them do not see, hear or understand them (Hill & Dallos, Citation2012; Moyer & Nelson, Citation2007).

Judged

Young people who self-harm may have problems with low self-esteem, feeling fat and ugly (Lesniak, Citation2010) and it is common that they feel afraid of a negative response from people around them (Klineberg et al., Citation2013; Tillman et al., Citation2018). Many experience that others judge them (Lesniak, Citation2010; Tillman et al., Citation2018), see them as strange (Hill & Dallos, Citation2012; Klineberg et al., Citation2013), and that they have to endure cruel jokes and others making fun of them (McAndrew & Warne, Citation2014).

Hiding oneself

Self-harming behaviour among young people is something hidden and kept secret from the environment (Hill & Dallos, Citation2012; Klineberg et al., Citation2013; Kokaliari & Berzoff, Citation2008; Lesniak, Citation2010; McAndrew & Warne, Citation2014; Moyer & Nelson, Citation2007; Rissanen et al., Citation2008; Tan et al., Citation2019; Tillman et al., Citation2018). Those who self-harm often wears full-coverage clothing as a protection (Rissanen et al., Citation2008), and they do not change clothes in public or participate in activities that require change of clothes in school. If someone in the environment notices the wounds/scars, the person can use lies about the reason in order to hide their behaviour (Lesniak, Citation2010).

Communication

Young people describe self-harming behaviour as a way to speak without using words and as a cry for help. In that way, letting others see the wounds and scars can be a way for them to communicate.

Speaking without words

By making other people see the wounds and scars, some young people who self-harm try to communicate how they feel (Hill & Dallos, Citation2012; Klineberg et al., Citation2013; Lesniak, Citation2010). They make their inner pain visible by letting the wounds and scars represent how they feel on the inside (Lesniak, Citation2010). Harm to oneself can be a way of making one’s voice heard without using words, an alternative to verbally express emotions (Hill & Dallos, Citation2012; Lesniak, Citation2010). Young people sometimes describe that it is not easy to communicate or talk openly about emotions and receiving support within the family (Hill & Dallos, Citation2012; Kokaliari & Berzoff, Citation2008; Lesniak, Citation2010; Tillman et al., Citation2018). This is because reactions to self-harming behaviour from parents and relatives often are experienced negatively (Hill & Dallos, Citation2012; Klineberg et al., Citation2013; Moyer & Nelson, Citation2007; Rissanen et al., Citation2008; Tillman et al., Citation2018).

Cry for help

According to young people, self-harming behaviour can sometimes be used as a way to seek help and by showing the wounds and scars, other people can understand that it is a cry for help (Klineberg et al., Citation2013; Rissanen et al., Citation2008). Although the wounds and scars are shown consciously, young people experience that people around them neither react nor care (Moyer & Nelson, Citation2007; Rissanen et al., Citation2008). Young people who self-harm do not always receive the help they want from healthcare, that is someone who listen with an open mind (Moyer & Nelson, Citation2007; Rissanen et al., Citation2008). Seeking help is also not self-evident for young people who self-harm. They do not always know where to turn and it can be difficult to find the courage to seek help and to do so without involving the family (Klineberg et al., Citation2013; McAndrew & Warne, Citation2014; Tillman et al., Citation2018). However, they express a desire for someone to care about them (Klineberg et al., Citation2013; Lesniak, Citation2010; McAndrew & Warne, Citation2014; Tillman et al., Citation2018), a person with an open mind who wants to listen (Moyer & Nelson, Citation2007; Tillman et al., Citation2018). Young people who self-harm express that they would like to talk about their problems and feelings with other people who have the same experiences (Bheamadu et al., Citation2012; Klineberg et al., Citation2013).

Discussion

This study was a metasynthesis of the results from qualitative studies investigating young people’s experiences of living with self-harming behaviour. The results show that living with self-harming behaviour was a necessary pain and that it made life more manageable by getting relief and security, and by controlling overwhelming feelings. Young people suffered from feeling addicted to self-harm and from shame, guilt, and self-punishment. Furthermore, they experienced alienation, and loneliness, hiding oneself, and felt judged by people around them. They tried to communicate without words, using their wounds and scars instead as a cry for help.

Young people from the included studies used self-harm as a way to cope with unbearable emotions, take control, get immediate relief, and reduce their emotional suffering. They also express that they cut themselves to feel more alive (Bheamadu et al., Citation2012; Lesniak, Citation2010; Rissanen et al., Citation2008). Our results echo those in previous research mainly on adults (Klonsky, Citation2011; Lloyd-Richardson et al., Citation2007; Rayner & Warne, Citation2016; West et al., Citation2013) and in a metasynthesis by Stänicke et al. (Citation2018) on adolescents. In Eriksson’s (Citation2015) theory on the suffering person, suffering appears as a part of life and can have its origin in the fact that humans feel inadequate and do not live the life they desire. It is also argued that humans do not want to suffer and use a variety of different strategies to manage suffering (Eriksson, Citation2015).

The present results show that young people who self-harm experience many types of suffering, partly through self-punishment and self-hatred and partly through feelings of guilt and shame. They describe not wanting to hurt others by letting their own anger spill over on them. Therefore, they chose to expose themselves to more suffering rather than see someone else suffer. This in combination with a strong connection between self-criticism, shame, self-hatred and a will to hurt oneself may be one of the reasons why the person feels deserved to be punished. Stänicke et al. (Citation2018) reported similar results about adolescent’s ambivalence about sharing their experiences with others. On the one hand, they showed that adolescents were afraid of showing their feelings because they did not want to be judged. On the other hand, they wished to gain some understanding from others. According to Eriksson (Citation2015) suffering and guilt are connected, and humans feel guilt for many different things in life, and wants to atone for guilt by sacrificing something, that is by suffering. In the present results, this is seen in young people’s experiences of shame and guilt where they consider themselves to have betrayed both themselves and others, and because of that punish themselves to atone for what they have done. Deafening these feelings by harming oneself provides relief for the moment but leads to increased feelings of shame and guilt afterwards which in turn must be alleviated with the help of self-harm (Arkins et al., Citation2013). This vicious circle of shame, anger and self-harm which can also be reinforced by the treatment and approach from healthcare professionals (Rayner & Warne, Citation2016).

The results show that young people who self-harm try to communicate their suffering wordlessly, through their wounds and scars. This kind of communication among people who self- harm is also reported by other researchers (Klonsky, Citation2011; McAllister, Citation2003; West et al., Citation2013; Zetterqvist et al., Citation2013). According to Eriksson (Citation2015), suffering is unique and can be expressed in many different ways, and people often transform suffering into anxiety, pain, or a physical expression that others can see or understand. Our result show that people who self-harm may also feel even more hurt, ashamed, and unwilling to talk about their suffering when it is perceived as ‘unworthy’. This shame and reluctance to seek help likely causes young people who self-harm to continue to injure themselves and get caught in a vicious circle of suffering, shame, loneliness, and further self-harm. McAllister (Citation2003) argues that these negative consequences can not only harm the person physically, but also risk their life. As mentioned earlier, research (Arkins et al., Citation2013; Hicks & Hinck, Citation2008; ISSS, Citation2016) shows an increased risk of suicide in those with self-harming behaviour. However, the results of this literature study show that young people who self-harm do not self-harm with the intention of taking their own lives, instead they wish to live and the only way to do so is to handle their suffering with self-harm – a necessary pain.

The results show that many young people who self-harm suffer from feelings of exclusion. They feel judged by their surroundings and ashamed of their own loneliness. They hide their wounds but still feel the stigma and judgement of others, both in society and in healthcare (Mitten et al., Citation2016). They feel that healthcare professionals draw rapid conclusions (Hill & Dallos, Citation2012; Klineberg et al., Citation2013) and judge them because of their diagnosis, appearance, and behaviour (Lesniak, Citation2010; Tillman et al., Citation2018). This makes them feel diminished, questioned, and stigmatised, which can lead to them feeling even more excluded and isolated and in turn concealing their behaviour and not seeking help (Gulliver et al., Citation2010; Mitten et al., Citation2016). One strategy to avoid stigma can be to hide one’s wounds and scars (Johansson, Citation2010; Straiton et al., Citation2013). Barton-Breck and Heyman (Citation2012) describe self-harming behaviour as living a lie; always hiding one’s injuries leads to isolation and self-harm arises from an initial feeling of not fitting in, This, in turn, is reinforced by the fact that the behaviour itself makes the person feel different and become further isolated from others.

The results show that young people who self-harm want someone to truly see them. They long for people who will be present with them, listen to them, and wish them well. This desire is part of what Eriksson (Citation2015) calls the ‘drama of suffering’, in which the sufferer needs an opposite number who can confirm both the person and their suffering and make the person feel seen. Confirmation is about being present and not abandoning the person. The young people in the study results lack a partner in their drama who can confirm and be there with them. This is consistent with studies on adults with self-harming behaviour who feel distrusted, abandoned, and hopeless in an encounter which lacks confirmation (Lindgren et al., Citation2018).

Young people who self-harm try to communicate with those in their surroundings using their bodies and their suffering. They need someone to play their opposite in the drama of suffering, but find no one to take on the role. Perhaps, as Eriksson (Citation2015) suggests, some people are insensitive to the suffering of others and some dare not face it. Perhaps people communicate with different languages, and healthcare professionals need to learn the language of young people who self-harm. With this understanding, professionals may be able to create helpful encounters in which young people feel confirmed and seen and help them break the vicious cycle of self-harm.

Methodological discussion

The results of a qualitative metasynthesis is a co-creation between the researchers and the papers included. According to Krippendorff (Citation2013) a text never entails one single meaning. Therefore, we argue that the findings presented in this study are one possible synthesis built upon our interpretation of texts that we extracted and aggregated. We wanted to synthesise research on young people’s experiences of living with self-harming behaviour in its contemporary context. Therefore, we chose research published in the last 10 years. Although the number of sources reviewed was limited, the included studies cover a broad geographical range, which may increase the review’s transferability across countries.

Conclusion

Young people who harm themselves view self-harm as a necessary pain; they suffer and often do not get the help they need. The help young people who self- harm to feel confirmed it is essential to listen to them, validate their thought and emotions, and not pass judgement. Further, by greater awareness of the phenomena and by striving for changed attitudes towards these persons healthcare staff can help in developing and improving care for young people who self-harm and breaking their cycle of suffering and exclusion. Further research is needed to offer these young people the help and support they need and to increase understanding of self-harming behaviour in society, healthcare organisations, and schools to reduce the stigma that adds to the harm.

References

- American Psychiatric Association (APA). (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-5 (5th ed.). American Psychiatric Association.

- Angelotta, C. (2015). Defining and refining self-harm: A historical perspective on nonsuicidal self-injury. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 203(2), 75–80. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1097/NMD.0000000000000243

- Arkins, B., Tyrrell, M., Herlihy, E., Crowley, B., & Lynch, R. (2013). Assessing the reasons for deliberate self-harm in young people: Brigid Arkins and colleagues describe the risk factors common to individuals who attended an emergency department in Ireland. Mental Health Practice, 16(7), 28–32. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.7748/mhp2013.04.16.7.28.e804

- Barton-Breck, A., & Heyman, B. (2012). Accentuate the positive, eliminate the negative? The variable value dynamics of non-suicidal self-hurting. Health Risk & Society, 14(5), 445–464. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13698575.2012.697130

- *Bheamadu, C., Fritz, E., & Pillay, J. (2012). The experiences of self-injury amongst adolescents and young adults within a South African context. Journal of Psychology in Africa, 22(2), 263–268. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/14330237.2012.10820528

- Bjärehed, J. (2012). Characteristics of self-injury in young adolescents: Findings from cross-sectional and longitudinal studies in Swedish schools. Department of Psychology, Faculty of Social Sciences, Lund University.

- Doyle, L., Sheridan, A., & Treacy, M. P. (2017). Motivations for adolescent self-harm and the implications for mental health nurses. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing, 24(2–3), 134–142. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/jpm.12360

- Eriksson, K. (2015). Den lidande människan [The suffering human]. (2nd ed.). Liber.

- Eriksson, T., & Åkerman, S. (2012). Patienters upplevelser av vården för självskadebeteende. Rapport från Nationella självskadeprojektet [Patients’ experiences of care for self-harming behaviour. Report from the National Self-harm Project]. https://nationellasjalvskadeprojektet.se/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/3Erikssonoch%C3%85kermanPatientersupplevelser-1.pdf

- Gulliver, A., Griffiths, K. M., & Christensen, H. (2010). Perceived barriers and facilitators to mental health help-seeking in young people: A systematic review. BMC Psychiatry, 10(1) 113. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-244X-10-113

- Hawton, K., Saunders, K. E. A., & O’Connor, R. C. (2012). Self-harm and suicide in adolescents. Lancet (London, England), 379(9834), 2373–2382. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60322-5

- Hicks, K. M., & Hinck, S. M. (2008). Concept analysis of self-mutilation. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 64(4), 408–413. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2648.2008.04822.x

- *Hill, K., & Dallos, R. (2012). Young people’s stories of self-harm: A narrative study. Clinical Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 17(3), 459–475. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1359104511423364

- International Society for the Study of Self-Injury (ISS). (2018, May). What is self-injury? https://itriples.org/about-self-injury/what-is-self-injury.

- International Society for the Study of Self Injury (ISS). (2016). Fast facts. ISSS. https://itriples.org/category/about-self-injury/

- Johansson, A. (2010). Självskada. En etnologisk studie av mening och identitet i berättelser om skärande. [Self-harm. An ethnological study of meaning and identity in narratives about cutting] [Doctoral dissertation]. Umeå University.

- *Klineberg, E., Kelly, M. J., Stansfeld, S. A., & Bhui, K. S. (2013). How do adolescents talk about self-harm: A qualitative study of disclosure in an ethnically diverse urban population in England. BMC Public Health, 13(1), 572. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-13-572

- Klonsky, E. D. (2011). Non-suicidal self-injury in United States adults: Prevalence, sociodemographics, topography and functions. Psychological Medicine, 41(9), 1981–1986. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291710002497

- *Kokaliari, E., & Berzoff, J. (2008). Non-suicidal self-injury among nonclinical college women: Lessons from Foucault. Affilia, 23(3), 259–269. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/0886109908319120

- Krippendorff, K. (2013). Content analysis: An introduction to its methodology (3rd ed.). SAGE.

- Landstedt, E., & Gillander, G. (2011). Deliberate self-harm and associated factors in 17-year-old Swedish students. Scandinavian Journal of Public Health, 39(1), 17–25. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1403494810382941

- *Lesniak, R. G. (2010). The lived experience of adolescent females who self-injure by cutting. Advanced Emergency Nursing Journal, 32(2), 137–147. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1097/TME.0b013e3181da3f2f

- Lindgren, B.-M., Svedin, C.-G., & Werkö, S. (2018). A systematic literature review of experiences of professional care and support among people who self-harm. Archives of Suicide Research: Official Journal of the International Academy for Suicide Research, 22(2), 173–120. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13811118.2017.1319309

- Lloyd-Richardson, E. E., Perrine, N., Dierker, L., & Kelley, M. L. (2007). Characteristics and functions of non-suicidal self-injury in a community sample of adolescents. Psychological Medicine, 37(8), 1183–1192. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1017/S003329170700027X

- Long, M., Manktelow, R., & Tracey, A. (2013). We are all in this together: Working towards a holistic understanding of self-harm. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing, 20(2), 105–113. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2850.2012.01893.x

- Looi, G.-M., Engström, Å., & Sävenstedt, S. (2015). A self-destructive care: Self-reports of people who experienced coercive measures and their suggestions for alternatives. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 36(2), 96–103. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3109/01612840.2014.951134

- McAllister, M. (2003). Multiple meanings of self harm: A critical review. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing, 12(3), 177–185. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1440-0979.2003.00287.x

- *McAndrew, S., & Warne, T. (2014). Hearing the voices of young people who self-harm: Implications for service providers. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing, 23(6), 570–579. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/inm.12093

- McGough, S., Wynaden, D., Ngune, I., Janerka, C., Hasking, P., & Rees, C. (2021). Mental health nurses’ perspectives of people who self-harm. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing, 30(1), 62–71. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/inm.12814

- Mitten, N., Preyde, M., Lewis, S., Vanderkooy, J., & Heintzman, J. (2016). The perceptions of adolescents who self-harm on stigma and care following inpatient psychiatric treatment. Social Work in Mental Health, 14(1), 1–21. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/15332985.2015.1080783

- Møhl, B., & Skandsen, A. (2012). The prevalence and distribution of self-harm among Danish high school students. Personality and Mental Health, 6(2), 147–155. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1002/pmh.191

- Morrissey, J., Doyle, L., & Higgins, A. (2018). Self-harm: From risk management to relational and recovery-oriented care. The Journal of Mental Health Training, Education and Practice, 13(1), 34–43. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1108/JMHTEP-03-2017-0017

- *Moyer, M., & Nelson, K. W. (2007). Investigating and understanding self-mutilation: Student voice. Professional School Counseling, 11(1), 42–48. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/2156759X0701100106

- Muehlenkamp, J. J., Claes, L., Havertape, L., & Plener, P. L. (2012). International prevalence of adolescent non-suicidal self-injury and deliberate self-harm. Child and Adolescent Psychiatry and Mental Health, 6, 10 https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1186/1753-2000-6-10

- Nock, M. K., & Prinstein, M. J. (2004). A functional approach to the assessment of self-mutilative behavior. J Consult Clin Psychol, 72(5), 885–890. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-006X.72.5.885

- Polit, D. F., & Beck, C. T. (2013). Essentials of nursing research: Appraising evidence for nursing practice (8th ed.). Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins.

- Rayner, G., & Warne, T. (2016). Interpersonal processes and self-injury: A qualitative study using Bricolage. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing, 23(1), 54–65. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/jpm.12277

- *Rissanen, M., Kylmä, J., & Laukkanen, E. (2008). Descriptions of self-mutilation among Finnish adolescents: A qualitative descriptive inquiry. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 29(2), 145–163. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/01612840701792597

- Rissanen, M. L., Kylmä, J., & Laukkanen, E. (2012). Helping self-mutilating adolescents: Descriptions of Finnish nurses. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 33(4), 251–262. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.3109/01612840.2011.653035

- Sandelowski, M., & Barroso, J. (2003). Classifying the findings in qualitative studies. Qualitative Health Research, 13(7), 905–923. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732303253488

- Sandelowski, M., & Barroso, J. (2007). Handbook for synthesizing qualitative research. Springer.

- Shaw, D. G., & Sandy, P. T. (2016). Mental health nurses’ attitudes toward self-harm: Curricular implications. Health SA Gesondheid, 21(C), 406–414. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hsag.2016.08.001

- Skårderud, F. (2008). Hellig anoreksi sult og selvskade som religiøse praksiser. Caterina av Siena (1347-80) [Sacred anorexia: Hunger and self-harm as religious practices. Catherine of Siena (1347-80)]. Tidsskrift for Norsk Psykologforening, 45(4), 408–420.

- Stanicke, L. I., Haavind, H., & Gullestad, S. E. (2018). How do young people understand their own self-harm? A metasynthesis of adolescents’ subjective experience of self-harm. Adolescent Research Review, 3(2), 173–191. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s40894-018-0080-9

- Straiton, M., Roen, K., Dieserud, G., & Hjelmeland, H. (2013). Pushing the boundaries: Understanding self-harm in a non-clinical population. Archives of Psychiatric Nursing, 27(2), 78–83. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apnu.2012.10.008

- *Tan, S. C., Tam, C. L., & Bonn, G. (2019). Feeling better or worse? The lived experience of non-suicidal self-injury among Malaysian university students. Asia Pacific Journal of Counselling and Psychotherapy, 10(1), 3–20. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/21507686.2018.1541912

- *Tillman, K. S., Prazak, M., & Obert, M. L. (2018). Understanding the experiences of middle school girls who have received help for non-suicidal self-injury. Clinical Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 23(4), 514–527. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1177/1359104517743784

- Victor, S. E., Muehlenkamp, J. J., Hayes, N. A., Lengel, G. J., Styer, D. M., & Washburn, J. J. (2018). Characterizing gender differences in nonsuicidal self-injury: Evidence from a large clinical sample of adolescents and adults. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 82, 53–60. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.comppsych.2018.01.009

- West, E., Newton, V. L., & Barton-Breck, A. (2013). Time frames and self-hurting: That was then, this is now. Health, Risk & Society, 15(6–7), 580–595. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1080/13698575.2013.846302

- Zetterqvist, M., Lundh, L. G., Dahlström, Ö., & Svedin, C. (2013). Prevalence and function of non-suicidal self-injury (NSSI) in a community sample of adolescents, using suggested DSM-5 criteria for a potential NSSI disorder. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 41(5), 759–773. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-013-9712-5