Abstract

Mental health nursing focuses on patients’ experiences, accessed through narratives developed in conversations with nursing staff. This study explored nursing staff’s experiences of using the nursing intervention Daily Conversations in psychiatric inpatient care. We used a qualitative questionnaire and received 103 responses. Qualitative content analysis of the data resulted in three themes describing both advantages and obstacles with Daily Conversations: Promotes participation, Contributes to confirming relations and Challenges previous structures. To illuminate the significance of confirming acts and make nursing staff more comfortable, the intervention could benefit from being more flexible and allowing in its structure. For the intervention to succeed, nursing staff need training in conversation, thorough preparation, shared reflections on values in mental health nursing, and structures to maintain its implementation and use.

Introduction

Mental health nursing focuses on patients’ experiences, which are accessed through narratives developed in conversations with nursing staff (Barker & Buchanan-Barker, Citation2005). These conversations in psychiatric inpatient care (PIC) help build relationships between patients and staff, support collaborative care (Barker & Buchanan-Barker, Citation2005), and are considered essential tools to reduce suffering and promote healing and recovery (Priebe et al., Citation2018; Rydenlund et al., Citation2019).

Communication deficiencies affect patients’ experiences of mental health nursing and reduce their trust in care. Despite their legal rights to good and safe care, the lack of treatment and communication experienced by patients with mental ill-health increases their risk for inadequate and unethical care (Molin et al., Citation2016a). As shown by Cutler et al. (Citation2020), nursing staff being responsive and caring could promote feelings of safety among patients in PIC. Therefore, there is a need for a specific focus on ensuring that nursing staff in PIC regularly offer patients daily conversations.

Conversations differ from psychiatric interviews as they aim for reciprocity, engagement, and the pursuit of equality (Barker & Buchanan-Barker, Citation2005) rather than patient assessment. Conversations are used to get closer to, understand and confirm patients in their suffering and personal needs. Further, to convey hope and support (Shattell et al., Citation2006). In PIC, conversations are effective nursing interventions that take patients’ personal experiences into account (Priebe et al., Citation2018). Various terms for these therapeutic conversations include supportive conversation and caring conversation. Supportive conversations are practiced to strengthen patients’ own resources, capabilities, and health. It focuses on solving problems, alleviating the challenges and demands of everyday life, and drawing upon the individual patient’s ability to handle a crisis. In psychiatric out-patient care, supportive conversations are often used with patients who do not meet the clinical criteria for other psychological treatments or when treatment has been completed and the patient still needs support (Bäck-Pettersson et al., Citation2014). Fredriksson (Citation2003) describes caring conversation as involving three forms of communication: relational, narrative, and ethical. Relational communication depends upon presence, touch, and listening; narrative communication creates a narrative of the patient’s suffering, and ethical communication shows compassion and mutual respect (Fredriksson, Citation2003).

Patients in PIC have described communication with nursing staff as unsatisfying and a source of frustration that negatively affects the care process (Looi et al., Citation2015). They need opportunities to talk about their suffering with someone who has time to listen and tries to understand them (Molin et al., Citation2016a; Wyder et al., Citation2015). Patients in PIC have also reported that conversations improve their relationships with nursing staff and increase their own influence over, and satisfaction with, their care (Molin et al., Citation2016a; Priebe et al., Citation2018). Bäck-Pettersson et al. (Citation2014) found that patients in PIC felt conversations with nurses helped them manage everyday stress and contributed to their recovery.

Gabrielsson et al. (Citation2016) reported that good nursing practice in PIC depended, among other things, on having enough time, being present, and connecting with patients. The ability to truly engage with patients enabled nursing staff to work in line with their moral beliefs.

Mental health nursing in the context of PIC has been described as complex, involving various and sometimes contradictory tasks and perspectives (Wyder et al., Citation2017). Researchers report that PIC nursing staff are often hindered by contextual factors from working to their ideals and competence (Molin et al., Citation2016b). For example, Graneheim et al. (Citation2014) reported that nurses strived to have conversations with patients but experienced contradictions between their ideals and the realities of PIC, which resulted in an unsatisfactory work situation and feelings of failure.

The nursing intervention daily conversations

In response to this, and to patients making requests for conversations via a patient forum with a user-involvement coordinator (UIC), employed by the clinic to increase user involvement in care, the nursing intervention Daily Conversation (DC) was developed. The purpose was to, in a structured way, ensure that patients’ needs for conversation were met and, to promote good nursing practice in PIC.

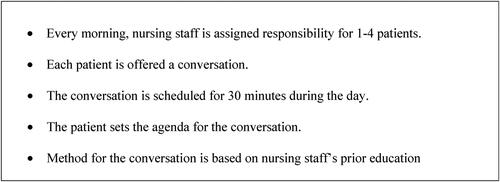

The structure of DC was introduced as a new routine on units from 2018 to 2020 by unit managers, nurses or UIC. As the method for conversations relied on nursing staff’s prior education, no additional training on conversation was given. Shared reflections on the meaning of DC were not included in the introduction either. DCs became part of the nursing staff’s daily planning and daily tasks. As shown in , the structure of DC requires all patients to be offered conversations every day for planned conversations to become more common on the units. Time for DCs is scheduled, and the patient sets the agenda for the conversation. How long the DC lasts depends on the patients’ needs, but the aim is to talk for about 30 minutes. The conversation tasks were distributed on morning reports and each nursing staff member was assigned to have DC with three or four patients.

In summary, conversations are central in mental health nursing. Patients asks for conversations and nursing staff strives to offer them. Both parties benefit from having conversations but contextual factors constitute hinders. DC has been introduced in psychiatric clinics in Sweden and actively offers patients a daily conversation with a nursing staff member. Clinical evaluations show positive outcomes for DC, but to our knowledge, no scientific studies have reported on the experiences of DC in PIC.

Aim

The aim of this study was to explore nursing staff’s experiences of DC in PIC.

Method

Design

The study used a qualitative descriptive design. PIC nursing staff provided written answers to a qualitative questionnaire, which underwent qualitative content analysis (Graneheim et al., Citation2017; Graneheim & Lundman, Citation2004; Lindgren et al., Citation2020). Qualitative content analysis was chosen as it enables description of variations of experiences. The study report was guided by the COREQ checklist (Tong et al., Citation2007).

Context

The study was conducted among nursing staff working at nine PIC units in two Swedish regions. The geographical distance between these regions is about 700 kilometres. Some units were still using DC, while others had ended the intervention. One unit was for psychiatric intensive care, one was general, and one was psychogeriatric. The other six units offered care for patients with attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder and autism, affective syndromes, psychosis, and anxiety syndromes. Patients were hospitalised voluntarily or involuntarily for acute or long-term mental ill-health. Each unit had about 15 beds and 30 nursing staff working on shifts. Nursing staff included enrolled nurses, registered nurses, and registered nurses with advanced education in psychiatric and mental health nursing.

Procedure

Of 13 units working with DC, nine agreed to join the study and nursing staff with experience using DC was included. Temporary and night-shift staff were excluded. Nursing staff were informed about the study via workplace meetings and UICs. Those who wanted to participate gave their written informed consent in connection with completing the qualitative questionnaire. In one region, two students distributed questionnaires at two units: 15 at one unit and 16 at the other. Three UICs distributed 30 questionnaires each to each of the other units. In total, 241 questionnaires were distributed and 103 responses were received.

Participants

Participants were 60 women, 42 men, and one who used non-binary personal pronouns. Five were registered nurses with advanced education in mental health nursing, 39 were registered nurses, and 59 were enrolled nurses. Their ages ranged from 20 to 68 (median 39) years, and their experience working in PIC, from 1 to 43 (median 6) years. Participants prior knowledge of conversations at bachelor level (n = 32) included motivational interviewing (MI), cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT), and phenomenological conversations; 22 reported no education on conversations, 20 did not remember, and 29 did not respond to the question. Participants prior knowledge on conversations via continuing education (n = 27) included MI, CBT, low affective communication, and mindfulness; 27 reported no continuing education on conversation, 18 did not remember, and 31 did not respond to the question.

Data collection

Because DC was implemented at units in different parts of the country, and to reach as many participants as possible, instead of interviews, a qualitative questionnaire was used for data collection. The questionnaire, created for the purpose of the study, collected demographic data and asked 15 open-ended questions about participants’ experiences of working with DC, similar to questions from an interview guide. For example, questions like: ‘Tell us about your work with DC with the patients;’ ‘How has using DC changed your work?’ ‘What changes have you experienced in patients’ engagement?’ and ‘Tell us about your experiences of implementing DC’, were included. Participants were asked to write their answers in free text with unlimited space.

Analysis

After reading the participants’ responses, the authors, both mental health nurses experienced in conversational work in PIC, followed the procedures of qualitative content analysis (Graneheim et al., Citation2017; Graneheim & Lundman, Citation2004; Lindgren et al., Citation2020). The text was first condensed, then divided into meaning units that were labelled with codes. Codes with similar content were grouped together, and the coded groups were abstracted and interpreted into subthemes. Subthemes with similar content were brought together, abstracted, and interpreted into themes. For example, codes like asking the patient, respecting their wishes, and letting the patient choose and have control were abstracted and interpreted into the subtheme Being open to personal choices, which was abstracted and interpreted together with Using an inviting approach and Acknowledging a clear structure into the theme Promotes participation. Moving back to the text, the authors continued to reflect on the condensed responses, the sorting, the abstractions, and the interpretations in relation to the original data. To broaden the analytic space (Malterud, Citation2012) and increase trustworthiness, the authors discussed the process with a colleague, also a mental health nurse.

Ethical considerations

The heads of the clinical departments approved the study, and unit managers and UICs informed and invited staff members to participate. All participants gave written informed consent and all responded anonymously to the questionnaire. The study follows the Swedish law on ethical approval (2003:406) and was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (World Medical Association, Citation2013).

Results

The analysis resulted in three themes: Promotes participation, Contributes to confirming relations and Challenges previous structures ().

Table 1. Overview of results.

Promotes participation

Participants felt DC promoted both patient and nursing staff participation. They were open to patients’ personal choices while acknowledging a clear structure.

Being open to personal choices

The participants reported either being spontaneous, not scheduling the conversation in advance or, asking patients each morning if they wanted a DC to allow them to plan for the conversation. They introduced themselves, explained the aim of DC, and allowed patients to decide whether they wanted a DC. It was reported that about half the patients declined DC, which the participants attributed to patients’ thinking it felt artificial and becoming too uncomfortable to accept.

The participants wrote they chose a private place for the conversation and although they did use a structure, they started with an open question. They expressed it was important to be flexible, to start the conversation on any topic the patient chose, and to allow the patient control. They asked the patients how they wanted the conversation, and they listened. Further, they described asking questions to help patients who withdrew during DC or when the conversation lacked flow. They tried to make the conversations pleasant and felt that patients appreciated being invited into the conversation and helped by the questions.

Participants described allowing patients to decide on the time for the conversation or deciding together. They pointed out that patients were able to choose and set the agenda for the conversation, including its content and arrangement. When participants felt this range of choices challenged the patients, they helped by asking questions.

Participants wrote DCs usually lasted 10 to 15 minutes, although some said they lasted ‘0 minutes to infinity’. Subjects for the conversation varied and depended on the patients’ condition. Common subjects were patients’ interests, wishes, moods, dreams, worries, and hopes; their social lives, families, life experiences, and significant events; their care on the unit including suggestions about their needs from staff, strategies to get healthier, questions about their illness and diagnosis, medicines, care planning, furlough and discharge, and things they forgot to mention to the physician; and usual topics of conversation such as the weather, movies and books, the pandemic, economic issues, and conflicts. Participants described trying to contribute to the conversation by asking follow-up questions emphasising the positive and healthy, and they felt able to help patients by listening actively and following their lead. Participants experienced that this approach led to patients being more self-aware, engaged in their own care and involved in change than before the intervention.

‘Usually it starts a bit tentatively, but when they understand that I am actively listening and following, then they open up about life experiences’. (Q8)

‘DC gives valuable information and the patients get opportunities to shared decision making as well as increased insight in themselves and their health’, (Q16)

Acknowledging a clear structure

Participants wrote that the new way of more structured work with DC had a positive influence on their skills and approach. They described becoming more structured and appreciated knowing what their colleagues were doing and what they themselves would be doing during their shift. They felt that being able to set aside time for conversations allowed them to do a better job and improve the quality of their care.

‘The change is positive as I can concentrate on some patients and know that other staff members take care of the others. The work is distributed more evenly’, (Q17)

Participants described that DC worked as a reminder to spend personal time with all patients. It also helped them feel better about silent and ‘invisible’ patients, since following the structure of DC made all patients visible. No one was forgotten. Some expressed that DC felt like a ‘real measure’ and was an essential part of PIC. It helped them see the benefits of increased participation among patients and they became more aware of possible changes in patients’ health status. Some also stated that they listened more, were more comfortable with silence, and became more experienced in their work. Participants also stated that DC was an acknowledgement of care and they expressed pride in this.

Contributes to confirming relations

Participants experienced that DC contributed to confirming relations as they gained a profound understanding of their patients and established mutual trust and safety with them.

Gaining a profound understanding of the patient

Participants expressed that DC contributed to a better approach and contact with the patients. They experienced that they came to know each other better when they spent time together. They described coming closer to each other and being less restrained in a more relaxed form of conversation. Participants also reported that when patients had the opportunity to speak freely, it became easier to see them as individuals and the care became more conversation-oriented.

‘When the patient get the opportunity to speak freely it becomes easier to see them as individuals. It is not just about [an] instrument for screening anymore. That feels good’, (Q32)

Participants described focussing more on the patients’ stories and engaging more in person-centred care. They stated that the conversations contributed to an overall picture of the patients and their deeper understanding of the patients’ situations. Through DC, participants received more information from the patients and thereby a deeper understanding and clearer insight about the patient and the patients’ problems. DC also helped them gather more information about what was needed, not just at the moment, but also later on. The received information about the patient eased the conversation and helped participants improve care planning and offer more person-centred care.

‘Most of the time, it makes me more humble and understanding of the patient’s situation and how the patient is feeling’, (Q35)

‘You get to know the patients in another way when you give them more time’, (Q38)

Establishing mutual trust and safety

Participants described that their communication with patients improved since introducing DC and made it easier for them to come closer to the patients. It also became easier to create relations with patients built on trust and safety. Participants experienced that such relations made patients more willing to seek help, share their emotions with staff, and trust in their care. Further, that as they showed each other respect, patients became more responsive and interested in the work they did. According to the participants, patients were able to clarify their needs and problems to staff, which allowed nursing staff to give them better and more personal care. Some participants reported that since DC, patients’ use of extra medication had decreased. The conversation was considered essential to faster recovery among patients.

Participants credited DC with contributing to all patients being seen every day and having a chance to express and know themselves better. Care became more equal. Participants described that DC became an additional opportunity for patients to express anything on their mind and to be heard, and more passive patients had a forum in which to express themselves without the pressure of having to initiate contact. DC was also reported to give patients a respite from their care. Patients were reported to feel seen, heard and appreciated and to become calmer, happier, and more satisfied after the conversations. One participant reported that patients who did not get DC felt offended and disappointed, but most thought patients felt their engagement and were grateful for being seen and heard:

‘I am convinced that the patients feel more heard and that can influence their interest and engagement’ (Q23)

‘Patients feel seen and also, they feel that we as staff are engaged’, (Q36)

Challenges previous structures

Participants experienced that DC challenges previous structures in their own approach, in the work on the unit, and within the organisation. They felt uncomfortable, struggled with different outlooks and asked for committed management.

Feeling uncomfortable

Participants described themselves as comforting, supportive, funny, and able to accept patients’ emotions. They were used to work with spontaneous conversations with patients and reported they used to make their conversations ‘melt in naturally’, DC was experienced as more structured and therefore also more artificial. Asking patients to have conversations in this way felt ‘too planned’ and ‘stiff,’ and some participants described that they shared this experience with some patients.

‘Offering conversations in a formal way can make patients withdraw. It can be overwhelming for them when you announce that now we are going to have a conversation. Basically, it is easier to start up a conversation by just passing by’, (Q50)

Participants stated that DC had not influenced their previous approach, that they already had conversations with patients, and that DC competed with other tasks. DC demanded more work in planning and documenting the conversation. It was experienced that this took time from being with the patients and therefore added to participants stress.

‘We have always had conversations with all patients. Now we are going to call it Daily Conversations!’ (Q70)

Some participants wrote they lacked knowledge about supportive conversations, and for some, the benefit of taking time for DC was not always evident. Conducting the conversations required more planning than before, and participants found it difficult to create quality conversations with some patients with dementia, psychosis, or manic episodes. One participant described avoiding DC with patients they experienced as ‘demanding,’ saying those patients had already had a lot of talking. It was also reported to be difficult to interrupt the conversation, which according to the structure could last for only 30 minutes. Sometimes it felt uncomfortable having more challenging conversations with patients.

‘I lose energy after fifteen to twenty minutes if the patient does not take any initiative, does not speak Swedish, and does not understand me’, (Q50)

Struggling with differing outlooks

Participants reported that the decision to work with DC was taken either by management or by themselves at team meetings. Some units had peer supporters who suggested the idea. Engagement varied among colleagues, and lack of engagement on the part of some, slowed the implementation. Participants experienced they did not have time for DC and that it was difficult to conduct a structured conversation. They also reported that good collaboration was needed among all the professions and that everyone was important for the intervention to work.

‘We do not manage DC at all. There is too much to do, low staffing, and a lot of administration’, (Q13)

Crowded units, constant observations, and low staffing were described as hindering factors for DC. However, participants had differing opinions on how they managed to conduct DC or not. While some wrote it took time they did not have, others wrote they did have time. Some experienced DC as a burden while others welcomed it. Some reported that they forgot to have the conversations and others described planning their day around them. Participants recognised that some did not value DC, while others valued it highly.

‘The patients are always worth a try for a conversation as most of the patients have needs to be heard and seen’, (Q9)

Asking for committed management

Participants asked for proper preparation and detailed information before implementing DC. They wanted management to lead the work, but also suggested a working group committed to the assignment. Some described the routines for DC as quick to set up, but others wrote routines were non-existent. Firm leadership was needed to establish DC, remind staff about both its aim and routine, and to clarify that it added nothing new, but offered a model to ensure conversations for all patients. Participants also wanted management to provide feedback to help them stay motivated, dare to try new things, and form a stable group of nursing staff willing to work and develop together at work.

‘It is necessary [to have] management that is active and takes the lead. Especially in the beginning of the change’, (Q39)

Participants also wanted management to provide lectures, exercises, and training on the theory and practice of DC. They asked for topic suggestions and practical tips on how to manage challenges during conversations. They also expressed a wish for evidence-based information on the effects of the intervention. Some wanted statistics, and some wanted research on patients’ experiences of DC and its meaning for patients’ recovery.

‘It would be optimal if all staff members had an education in methods for conversations. It would reduce fear of having conversations and give patients professional treatment’, (Q12)

The participants wrote the decision to implement DC should be clearly announced and supported by management. They wished the organisation to perceive the intervention as important, be motivated to stand behind it, and aim with the intervention rather to optimise care than to collect statistics. They wanted management to state DC as a rule, not a choice, but also to recognise that DC might not always be possible. They felt it essential that management provide resources for DC’s implementation, continue to work on the routine, and have patience as nurses accepted and became comfortable with the intervention.

‘It is important to continue to tune up the routines. If not, there is a risk that DC flows into the sand after a while’, (Q58)

Discussion

Our results describe nursing staff’s experiences of the nursing intervention Daily Conversations in PIC in terms of three themes: Challenges previous structures, Promotes participation, and Contributes to confirming relations. The findings are similar to other studies on introducing nursing interventions in PIC. For example, Molin et al. (Citation2020) concluded that joint activities for patients and staff in PIC fostered relationships but also felt burdensome to staff due to struggles with time and disagreements among staff members. Further, Salberg et al. (Citation2018), who evaluated a nursing staff-led behavioural group intervention in PIC, reported that nursing staff experienced patients as more involved in their care and that they came closer to the patients and the atmosphere on the unit improved. Negative effects included staff members’ negative attitudes and challenges in both conversations and interactions during the sessions. Stress and limited time were mentioned and hindrances, and better planning was suggested as a solution.

Implementing nursing interventions in PIC is challenging. As shown in this study, DC challenged previous structures on the units. Staff reported feeling uncomfortable with DC and struggling with differing outlooks, and they asked for committed management. Previous research in PIC suggests that successful implementation of an intervention requires nursing staff with a positive attitude, contextual adaptions, an active and supportive unit manager, and integration of the intervention in care plans (Clignet et al., Citation2017). Also, previous research shows that a culture of trust, cohesion, flexibility, and a broad acceptance to run projects may decrease unwillingness to give up old habits and try new things (Johansson et al., Citation2014). As Johansson et al. (Citation2014) stated, incorporating new routines is a timely process. When implementing nursing interventions in PIC, it is essential to build a solid foundation and to find structures to maintain the change. Management needs to provide staff with education on supportive conversations, strive to unite staff in a joint outlook, and work for maintenance via constant reminders (Raphael et al., Citation2021). In the current situation, we argue that it would have been helpful for nursing staff if they had received further theoretical and practical training in supportive and caring conversations. Further, opportunity to reflect together on values of mental health nursing. As we understand our results, a deeper established understanding of the value of DC among nursing staff could have facilitated the implementation.

The current study shows that staff experienced DC to promote patient participation. According to Cahill (Citation1996) and Sahlsten et al. (Citation2008) patient participation relies on a relationship between patient and nurse, a surrender of power and control from the nurse, shared knowledge, and active engagement in joint activities. Nilsson et al. (Citation2019) found that patient participation involves learning, caring relationships, and reciprocity. These results are in line with results by Foye et al. (Citation2020). Their narrative synthesis of patients’ perspectives on activities in PIC show that activities contribute to social connectedness and psychological well-being. Patients increased participation in their own care can be related to what Barker and Buchanan-Barker (Citation2005) refer to as ‘reclaiming life’. Reclaiming one’s narrative can contribute to a sense of being able to navigate one’s life. Both the narrative and the relationship created in DC can contribute to recovery in people with mental ill-health. However, Nilsson et al. (Citation2019) also highlight the risk of taking patient participation for granted, something accepted, working in practice. Reflecting on our results in the light of this statement, we found contradictory descriptions. While nursing staff strove for patient participation and caring relationships, they also felt uncomfortable with the new routine and had trouble seeing the value of offering patients DC. We argue that if nursing staff see DC as just a new routine to be implemented, without training in its implementation and benefits, patient participation and recovery will be threatened.

Our results also suggest that working with DC contributes to confirming relations between patients and staff. According to Cissna and Seeburg (Citation1981, p. 259), confirmation conveys ‘To me, you exist! We are relating! To me you are significant! Your way of experiencing your world is valid!’ Skatvedt (Citation2017) argues that people in vulnerable situations treasure ‘everydayness’ and human interactions with nursing staff and found that co-silence, inclusion, and authencity are interactional ways of showing others that we are ‘being human together’. Topor et al. (Citation2018) argue that taking initiative, inviting, and being available for a shared moment contribute to experiences of being confirmed. The significance of such actions is also shown in current empirical studies. McAllister et al. (Citation2019) showed that active listening, empathy, and understanding patients’ experiences are key components in building relationships and in recovery-oriented mental health nursing. Horgan et al. (2021) reported that patients in PIC desire qualities in nursing staff such as dignity, compassion, and demonstrated interest. Cutler et al. (Citation2021) showed that patients in PIC, who feel confirmed in their interactions with nursing staff, experience safety. With all these facts in mind, we argue that offering and performing DC could be experienced as confirming by patients in PIC. However, although our results indicate that DC contributes to confirming relationships, we also see the risk that such acts of confirmation might be taken for granted or seen as insignificant in PIC. For PIC to be a place that promotes personal recovery through confirming relationships, the power of everyday situations and acts of confirmation need to be acknowledged and addressed.

Methodological discussion

The study used a qualitative questionnaire with open-ended questions. The questionnaire was tailored to the purpose of the study. A limitation of this method of data collection was that we did not have the opportunity to ask follow-up questions to deepen the content of the data. In our considerations, however, we saw advantages to using this method. First, participants could convey their narratives without being influenced by us. Second, as there was no need for physical participation, more participants had the opportunity to share their experiences (Polit & Beck, Citation2004). A total of 103 participants responded for a response rate of 43%, which could be considered low, but in qualitative research, data is determined by its quality rather than its quantity (Graneheim et al., Citation2017). We judged the data to have enough quality to be analysed. After analysing and when reading our results, we noticed that some themes might be considered as overlapping. However, due to the intertwined nature of human experiences, it is not always possible to create exclusive themes when data deal with experiences (Graneheim & Lundman, Citation2004). The variation among participants was satisfactory, but we wish to draw readers’ attention to the fact that most participants were enrolled and registered nurses without advanced education in mental health nursing. These circumstances might have affected the results as one can assume that enrolled and registered nurses without advanced education in mental health nursing are less trained to perform conversations than those who have this competence. With the Swedish context in mind, one can also assume that the formal competence in our set of participants reflects the prevailing level of formal competence in Swedish PIC.

Conclusion and relevance for clinical practice

This study contributes to knowledge on nursing staff’s experiences of DC and implementation of nursing interventions in PIC. DC, as form of supportive and caring conversation, may facilitate patient participation and confirming relations in PIC. However, to illuminate the significance of confirming acts and make nursing staff more comfortable, DC could benefit from being more flexible and allowing in its structure. By adapting the invitation and the course of the conversation to the unique patient’s situation and mood, DC could appear as more genuine than artificial.

For implementation of DC to succeed, thorough preparations and structures for maintenance are needed. There is a need to balance structure and understanding. Implementing DC requires knowledge and training in supportive and caring conversations among staff and joint reflections on values in mental health nursing. Further research is needed before conclusions can be drawn on the effects of the intervention.

Author contributions and authorship statement

Study design: JM, UHG; Analysis and manuscript preparation: JM, UHG. Both authors agreed upon the final manuscript.

Acknowledgements

We thank Rimma Smirodskaya, Maha Salih, Anna Skoglund, Åsa Steinsaphir, and Josefine Hallenborg for their valuable contributions during data collection.

Conflict of interest

The authors report no conflict of interest.

Funding

The author(s) reported there is no funding associated with the work featured in this article.

References

- Bäck-Pettersson, S., Sandersson, S., & Hermansson, E. (2014). Patients’ experiences of supportive conversation as long- term treatment in a Swedish psychiatric outpatient care context: A phenomenological study. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 35(2), 127–133. https://doi.org/10.3109/01612840.2013.860646.

- Barker, P., & Buchanan-Barker, P. (2005). The Tidal Model: A guide for mental health professionals. Routledge.

- Cahill, J. (1996). Patient participation: A concept analysis. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 24(3), 561–571. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2648.1996.22517.x.

- Cissna, K. N. L., & Seeburg, E. (1981). Patterns of interactional confirmation and disconfirmation. In C. Wilder-Mott & J. H. Weakland (Eds.), Rigor & imagination: Essays from the legacy of Gregory Bateson (pp. 253–282). Praeger.

- Clignet, F., van Meijel, B., van Straten, A., & Cuijpers, P. (2017). A qualitative evaluation of an inpatient nursing intervention for depressed elderly: The systematic activation method. Perspectives in Psychiatric Care, 53(4), 280–288. https://doi.org/10.1111/ppc.12177.

- Cutler, N. A., Sim, J., Halcomb, E., Moxham, L., & Stephens, M. (2020). Nurses’ influence on consumers’ experience of safety in acute mental health units: A qualitative study. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 29(21–22), 4379–4386. https://doi.org/10.1111/jocn.15480.

- Cutler, N. A., Sim, J., Halcomb, E., Stephens, M., & Moxham, L. (2021). Understanding how personhood impacts consumers’ feelings of safety in acute mental health units: A qualitative study. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing, 30(2), 479–486. https://doi.org/10.1111/inm.12809.

- Foye, U., Li, Y., Birken, M., Parle, K., & Simpson, A. (2020). Activities on acute mental health inpatient wards: A narrative synthesis of the service users’ perspective. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing, 27(4), 482–493. https://doi.org/10.1111/jpm.12595.

- Fredriksson, L. (2003). Det vårdande samtalet [Doctoral thesis]. Åbo Akademis förlag. https://www.doria.fi/handle/10024/43659

- Gabrielsson, S., Sävenstedt, S., & Olsson, M. (2016). Taking personal responsibility: Nurses’ and assistant nurses’ experiences of good nursing practice in psychiatric inpatient care. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing, 25(5), 434–443. https://doi.org/10.1111/inm.12230.

- Graneheim, U. H., & Lundman, B. (2004). Qualitative content analysis in nursing research: Concepts, procedures and measures to achieve trustworthiness. Nurse Education Today, 24(2), 105–112. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2003.10.001.

- Graneheim, U. H., Lindgren, B. M., & Lundman, B. (2017). Methodological challenges in qualitative content analysis: A discussion paper. Nurse Education Today, 56, 29–34. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nedt.2017.06.002.

- Graneheim, U. H., Slotte, A., Säfsten, H. M., & Lindgren, B. M. (2014). Contradictions between ideals and reality: Swedish registered nurses’ experiences of dialogues with inpatients in psychiatric care. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 35(5), 395–402. https://doi.org/10.3109/01612840.2013.876133.

- Horgan, A., O Donovan, M., Manning, F., Doody, R., Savage, E., Dorrity, C., O'Sullivan, H., Goodwin, J., Greaney, S., Biering, P., Bjornsson, E., Bocking, J., Russell, S., Griffin, M., MacGabhann, L., van der Vaart, K. J., Allon, J., Granerud, A., Hals, E., … Happell, B. (2021). ‘Meet me where I am’: Mental health service users’ perspectives on the desirable qualities of a mental health nurse. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing, 30(1), 136–147. https://doi.org/10.1111/inm.12768.

- Johansson, C., Åstrom, S., Kauffeldt, A., Helldin, L., & Carlstrom, E. (2014). Culture as a predictor of resistance to change: A study of competing values in a psychiatric nursing context. Health Policy (Amsterdam, Netherlands), 114(2–3), 156–162. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.healthpol.2013.07.014.

- Lindgren, B. M., Lundman, B., & Graneheim, U. H. (2020). Abstraction and interpretation during the qualitative content analysis process. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 108, 103632. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnursstu.2020.103632.

- Looi, G. M. E., Engström, Å., & Sävenstedt, S. (2015). A self-destructive care: Self-reports of people who experienced coercive measures and their suggestions for alternatives. Issues in Mental Health Nursing, 36(2), 96–103. https://doi.org/10.3109/01612840.2014.951134.

- Malterud, K. (2012). Systematic text condensation: A strategy for qualitative analysis. Scandinavian Journal of Public Health, 40(8), 795–805. https://doi.org/10.1177/1403494812465030.

- McAllister, S., Robert, G., Tsianakas, V., & McCrae, N. (2019). Conceptualizing nurse-patient therapeutic engagement on acute mental health wards: An integrative review. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 93, 106–118. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2019.02.013.

- Molin, J., Graneheim, U. H., Ringnér, A., & Lindgren, B. M. (2016b). From ideals to resignation–interprofessional teams perspectives on everyday life processes in psychiatric inpatient care. Journal of Psychiatric and Mental Health Nursing, 23(9-10), 595–604. https://doi.org/10.1111/jpm.12349.

- Molin, J., Graneheim, U., & Lindgren, B. M. (2016a). Quality of interactions influences everyday life in psychiatric inpatient care—Patients’ perspectives. International Journal of Qualitative Studies on Health and Well-Being, 11(1), 29897. https://doi.org/10.3402/qhw.v11.29897.

- Molin, J., Hällgren Graneheim, U., Ringnér, A., & Lindgren, B. M. (2020). Time Together as an arena for mental health nursing–staff experiences of introducing and participating in a nursing intervention in psychiatric inpatient care. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing, 29(6), 1192–1201. https://doi.org/10.1111/inm.12759.

- Nilsson, M., From, I., & Lindwall, L. (2019). The significance of patient participation in nursing care–a concept analysis. Scandinavian Journal of Caring Sciences, 33(1), 244–251. https://doi.org/10.1111/scs.12609.

- Polit, D. F., & Beck, C. T. (2004). Nursing research: Principles and methods. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.

- Priebe, Å., Wiklund Gustin, L., & Fredriksson, L. (2018). A sanctuary of safety: A study of how patients with dual diagnosis experience caring conversations. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing, 27(2), 856–865. https://doi.org/10.1111/inm.12374.

- Raphael, J., Price, O., Hartley, S., Haddock, G., Bucci, S., & Berry, K. (2021). Overcoming barriers to implementing ward-based psychosocial interventions in acute inpatient mental health settings: A meta-synthesis. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 115, 103870. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2021.103870.

- Rydenlund, K., Lindström, U. Å., & Rehnsfeldt, A. (2019). Hermeneutic caring conversations in forensic psychiatric caring. Nursing Ethics, 26(2), 515–525. https://doi.org/10.1177/0969733017705003.

- Sahlsten, M. J., Larsson, I. E., Sjöström, B., & Plos, K. A. (2008). An analysis of the concept of patient participation. Nursing Forum, 43(1), 2–11. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-6198.2008.00090.x.

- Salberg, J., Folke, F., Ekselius, L., & Öster, C. (2018). Nursing staff‐led behavioural group intervention in psychiatric in‐patient care: Patient and staff experiences. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing, 27(5), 1401–1410. https://doi.org/10.1111/inm.12439.

- Shattell, M. M., McAllister, S., Hogan, B., & Thomas, S. P. (2006). She took the time to make sure she understood‘: Mental health patients’ experiences of being understood. Archives of Psychiatric Nursing, 20(5), 234–241. https://doi.org/10.1016/fj.apnu.2006.02.002

- Skatvedt, A. (2017). The importance of ‘empty gestures’ in recovery: Being human together. Symbolic Interaction, 40(3), 396–413. https://doi.org/10.1002/symb.291

- Swedish Law. (2003:460). Lag (2003:460) om etikprövning av forskning som avser människor. https://www.riksdagen.se/sv/dokument-lagar/dokument/svensk-forfattningssamling/lag-2003460-om-etikprovning-av-forskning-som_sfs-2003-460

- Tong, A., Sainsbury, P., & Craig, J. (2007). Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): A 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. International Journal for Quality in Health Care: Journal of the International Society for Quality in Health Care, 19(6), 349–357. https://doi.org/10.1093/intqhc/mzm042.

- Topor, A., Bøe, T. D., & Larsen, I. B. (2018). Small things, micro-affirmations and helpful professionals everyday recovery-orientated practices according to persons with mental health problems. Community Mental Health Journal, 54(8), 1212–1220. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10597-018-0245-9.

- World Medical Association. (2013). Declaration of Helsinki: Ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. https://www.wma.net/policies-post/wma-declaration-of-helsinki-ethical-principles-for-medical-research-involving-human-subjects/

- Wyder, M., Bland, R., Blythe, A., Matarasso, B., & Crompton, D. (2015). Therapeutic relationships and involuntary treatment orders: Service users’ interactions with health‐care professionals on the ward. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing, 24(2), 181–189. https://doi.org/10.1111/inm.12121.

- Wyder, M., Ehrlich, C., Crompton, D., McArthur, L., Delaforce, C., Dziopa, F., Ramon, S., & Powell, E. (2017). Nurses experiences of delivering care in acute inpatient mental health settings: A narrative synthesis of the literature. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing, 26(6), 527–540. https://doi.org/10.1111/inm.12315.